Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MITE Discovery, Annotation and Organization

2.2. Genome-Specific MITEs Identification

2.3. Potential Uses of Genome-Specific MITES for Fingerprinting and Molecular Markers Developement

3. Results

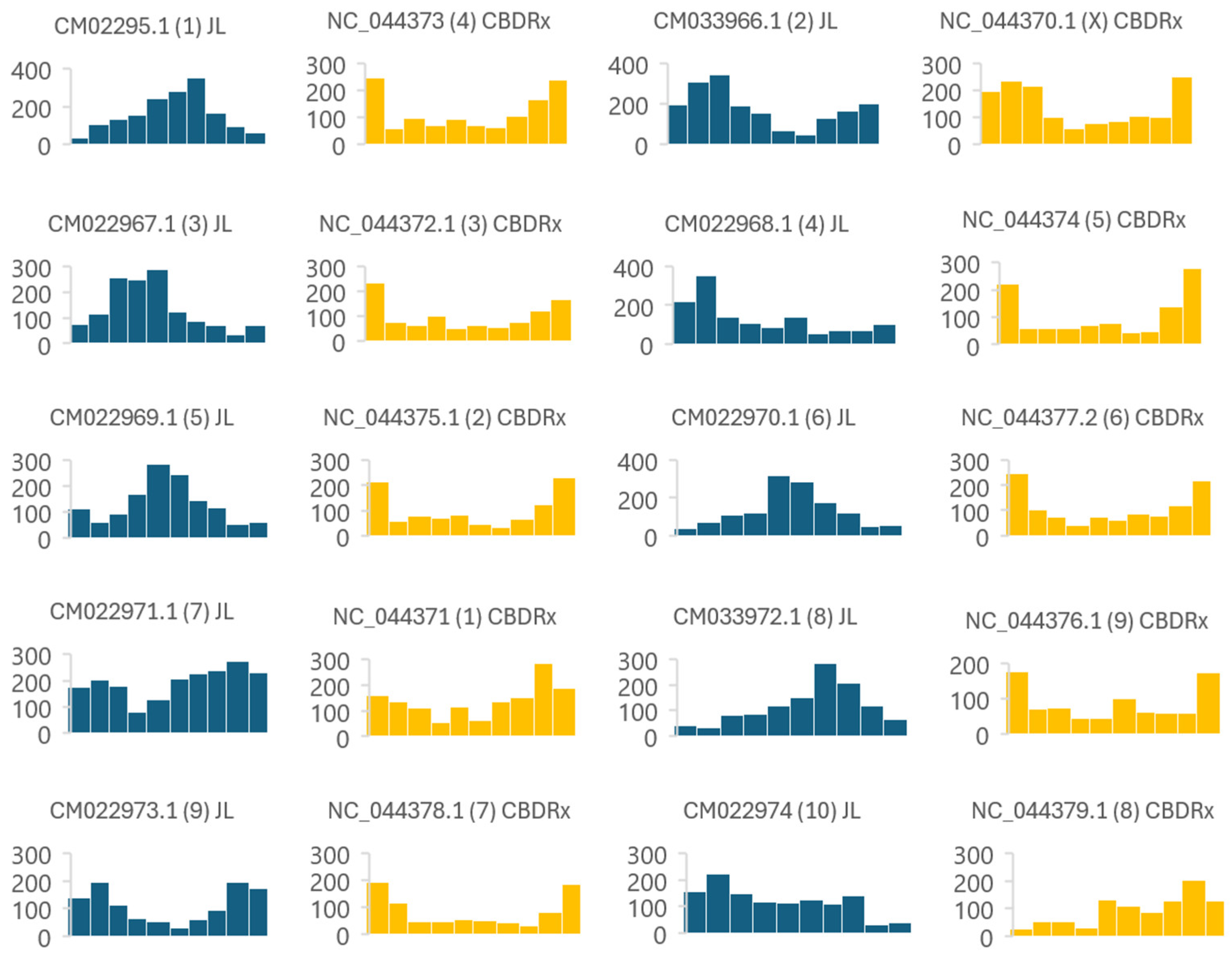

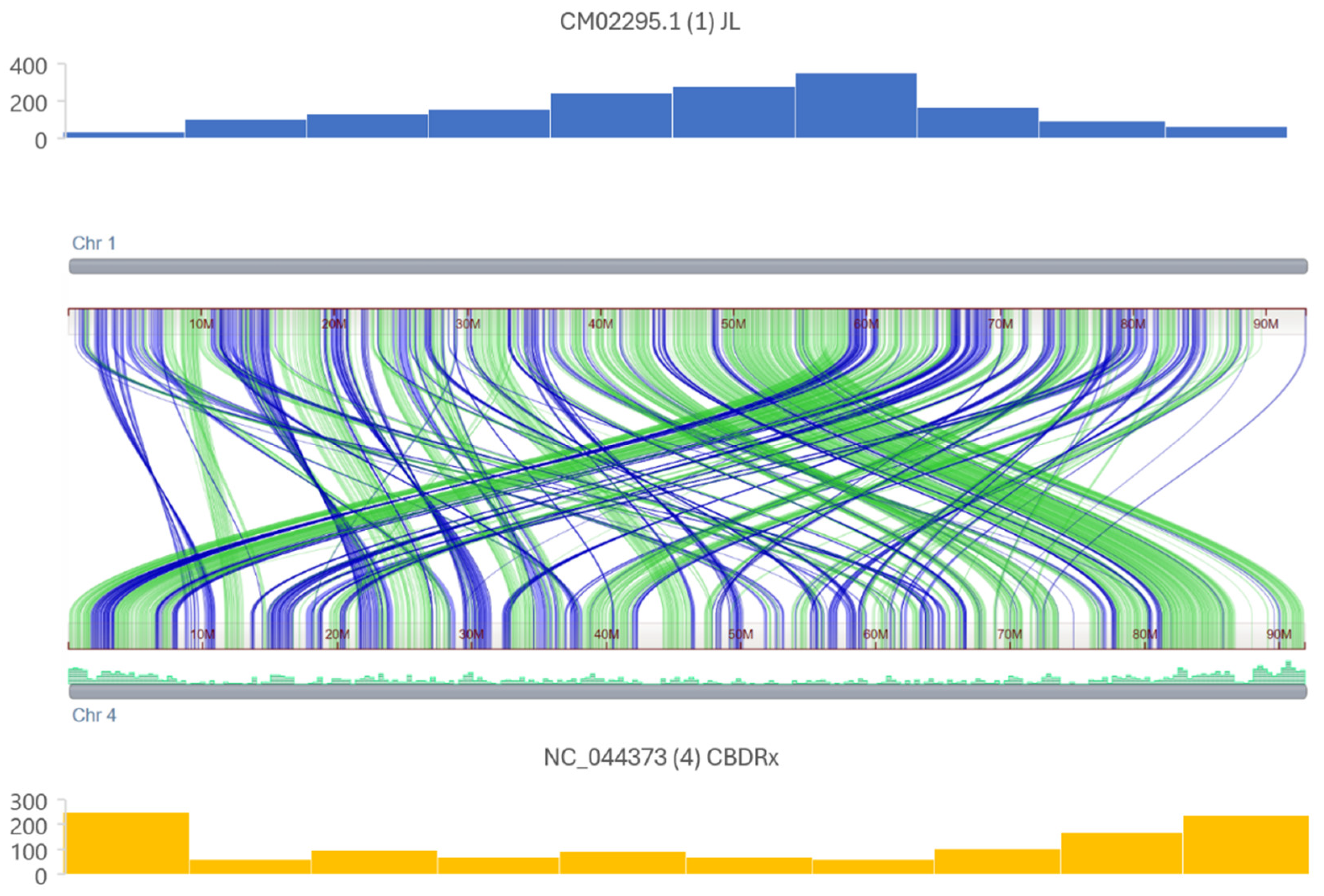

3.1. MITE Discovery, Annotation, and Organization

3.2. Genome-Specific MITEs Identification

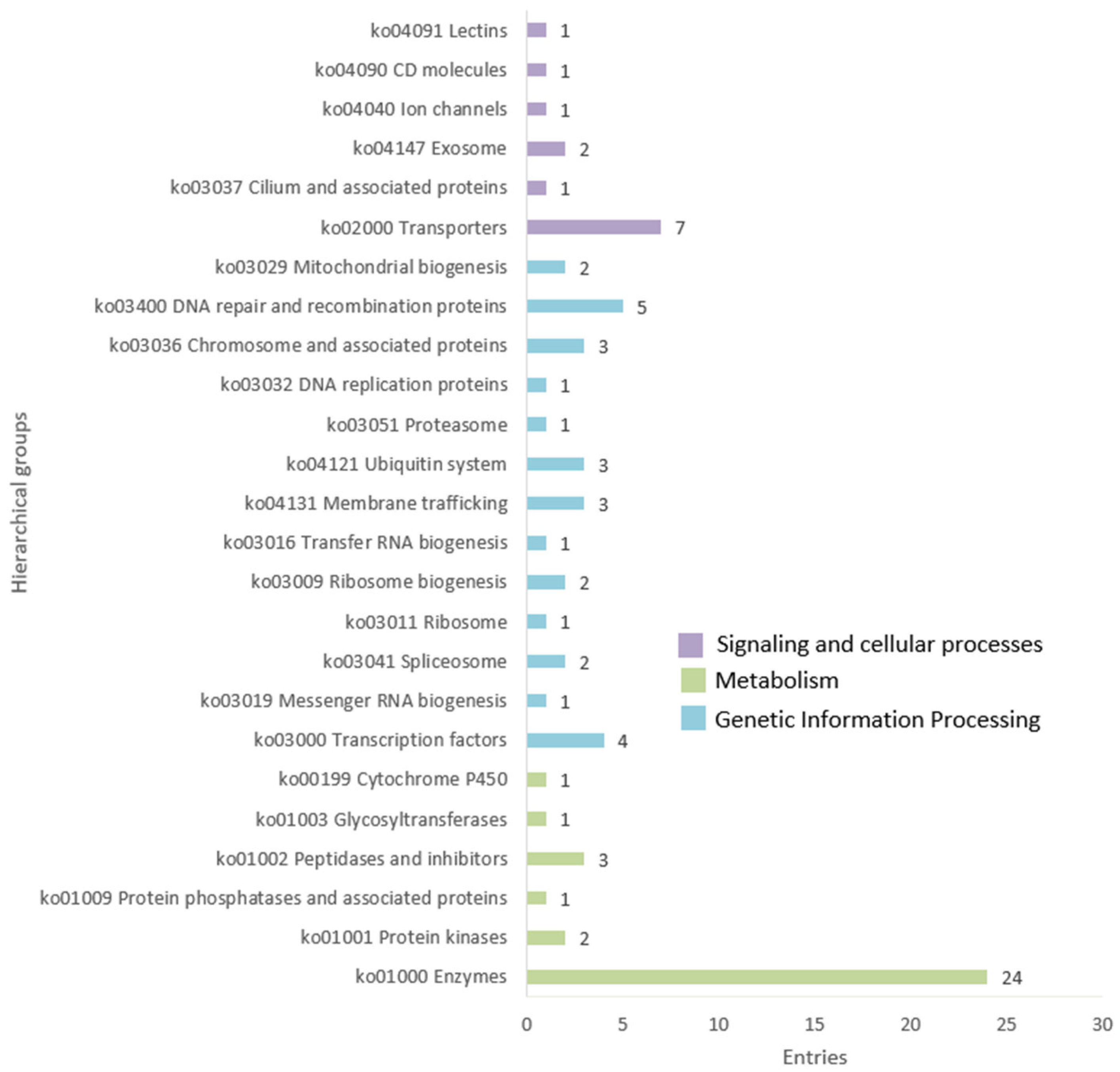

3.3. Finding Genome-Specific MITEs

3.4. Potential Uses of Genome-Specific MITES for Fingerprinting and Molecular Markers Development

4. Discussion

4.1. MITEs Density Within Cannabis Sativa Genomes

4.2. Potential of SNPs of Genome-Specific MITEs in Fingerprinting and Breeding

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Bakel, H.; Stout, J.M.; Cote, A.G.; Tallon, C.M.; Sharpe, A.G.; Hughes, T.R.; Page, J.E. The Draft Genome and Transcriptome of Cannabis Sativa. Genome Biol 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSohly, M.A.; Gul, W. Constituents of Cannabis Sativa. In Handbook of Cannabis; Pertwee, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2014; pp. 3–22.

- Clarke, R.C.; Merlin, M.D. Cannabis Domestication, Breeding History, Present-Day Genetic Diversity, and Future Prospects. CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2016, 35, 293–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangwala, S.H.; Rudnev, D. V; Ananiev, V. V; Oh, D.-H.; Asztalos, A.; Benica, B.; Borodin, E.A.; Bouk, N.; Evgeniev, V.I.; Kodali, V.K.; et al. The NCBI Comparative Genome Viewer (CGV) Is an Interactive Visualization Tool for the Analysis of Whole-Genome Eukaryotic Alignments. PLoS Biol 2024, 22, e3002405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, S.; Bai, X.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.J.; Huang, L.; Tang, W.; Haughn, G.; You, S.; et al. CannabisGDB: A Comprehensive Genomic Database for Cannabis Sativa L. Plant Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, L.; Purugganan, M. Molecular Genetic Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feschotte, C.; Jiang, N.; Wessler, S.R. Plant Transposable Elements: Where Genetics Meets Genomics. Nat Rev Genet 2002, 3, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, T.E.; Wessler, S.R. Tourist: A Large Family of Small Inverted Repeat Elements Frequently Associated with Maize Genes. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicker, T.; Sabot, F.; Hua-Van, A.; Bennetzen, J.L.; Capy, P.; Chalhoub, B.; Flavell, A.; Leroy, P.; Morgante, M.; Panaud, O.; et al. A Unified Classification System for Eukaryotic Transposable Elements. Nat Rev Genet 2007, 8, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wessler, S.R. MITE-Hunter: A Program for Discovering Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements from Genomic Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, T.E.; Wessler, S.R. Mobile Inverted-Repeat Elements of the Tourist Familyare Associated with the Genes of Many Cereal Grasses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1994, 91, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Su, W.; Kuang, H. Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements (MITEs) Have Been Accumulated through Amplification Bursts and Play Important Roles in Gene Expression and Species Diversity in Oryza Sativa. Mol Biol Evol 2012, 29, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjak, A.; Boué, S.; Forneck, A.; Casacuberta, J.M. Recent Amplification and Impact of MITEs on the Genome of Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.). Genome Biol Evol 2009, 1, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescente, J.M.; Zavallo, D.; Helguera, M.; Vanzetti, L.S. MITE Tracker: An Accurate Approach to Identify Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements in Large Genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yuan, K.; Yuan, M.; Meng, X.; Chen, M.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Qi, Y. Regulation of Rice Tillering by RNA-Directed DNA Methylation at Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements. Mol Plant 2020, 13, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, K.; Zhang, F.; Tsukiyama, T.; Saito, H.; Hancock, C.N.; Richardson, A.O.; Okumoto, Y.; Tanisaka, T.; Wessler, S.R. Unexpected Consequences of a Sudden and Massive Transposon Amplification on Rice Gene Expression. Nature 2009, 461, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Wan, M.; Guo, C.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Tian, Y.; Ge, X.; King, G.J.; Liu, K.; et al. Transposon Insertions within Alleles of BnaFLC.A10 and BnaFLC.A2 Are Associated with Seasonal Crop Type in Rapeseed. J Exp Bot 2020, 71, 4729–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.; Yun, Y.B.; Jeong, S.Y.; Cho, Y.; Kim, S. Characterization of Miniature Inverted Repeat Transposable Elements Inserted in the CitRWP Gene Controlling Nucellar Embryony and Development of Molecular Markers for Reliable Genotyping of CitRWP in Citrus Species. Sci Hortic 2023, 315, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, K.; Cho, E.; Yang, G.; Campbell, M.A.; Yano, K.; Okumoto, Y.; Tanisaka, T.; Wessler, S.R. Dramatic Amplification of a Rice Transposable Element during Recent Domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 17620–17625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh; Nandini, B. Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements (MITEs), Derived Insertional Polymorphism as a Tool of Marker Systems for Molecular Plant Breeding. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 3155–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Zitzewitz, J.; Szűcs, P.; Dubcovsky, J.; Yan, L.; Francia, E.; Pecchioni, N.; Casas, A.; Chen, T.H.H.; Hayes, P.M.; Skinner, J.S. Molecular and Structural Characterization of Barley Vernalization Genes. Plant Mol Biol 2005, 59, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaschetto, L.M. Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements (MITEs) and Their Effects on the Regulation of Major Genes in Cereal Grass Genomes. Molecular Breeding 2016, 36, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Hou, J.; Qin, M.; Dai, Z.; Jin, X.; Zhao, S.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lei, Z. Diversity and Association Analysis of Important Agricultural Trait Based on Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Element Specific Marker in Brassica Napus L. Oil Crop Science 2021, 6, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poretti, M.; Praz, C.R.; Meile, L.; Kälin, C.; Schaefer, L.K.; Schläfli, M.; Widrig, V.; Sanchez-Vallet, A.; Wicker, T.; Bourras, S. Domestication of High-Copy Transposons Underlays the Wheat Small RNA Response to an Obligate Pathogen. Mol Biol Evol 2020, 37, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanera, R.; Vendrell-Mir, P.; Bardil, A.; Carpentier, M.; Panaud, O.; Casacuberta, J.M. Amplification Dynamics of Miniature Inverted-repeat Transposable Elements and Their Impact on Rice Trait Variability. The Plant Journal 2021, 107, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Ji, G.; Liang, C. DetectMITE: A Novel Approach to Detect Miniature Inverted Repeat Transposable Elements in Genomes. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. MITE Digger, an Efficient and Accurate Algorithm for Genome Wide Discovery of Miniature Inverted Repeat Transposable Elements. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Shang, X. MiteFinder: A Fast Approach to Identify Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements on a Genome-Wide Scale. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); IEEE, November 2017; pp. 164–168.

- Satovic, E.; Cvitanic, E.T.; Plohl, M. Tools and Databases for Solving Problems in Detection and Identification of Repetitive DNA Sequences. Period Biol 2020, 121–122, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, B.; Xie, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Pei, L.; Yu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y. A High-Quality Reference Genome of Wild Cannabis Sativa. Hortic Res 2020, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassa, C.J.; Weiblen, G.D.; Wenger, J.P.; Dabney, C.; Poplawski, S.G.; Timothy Motley, S.; Michael, T.P.; Schwartz, C.J. A New Cannabis Genome Assembly Associates Elevated Cannabidiol (CBD) with Hemp Introgressed into Marijuana. New Phytol 2021, 230, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python; 2010.

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J Mol Biol 2016, 428, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y. KEGG Mapper for Inferring Cellular Functions from Protein Sequences. Protein Science 2020, 29, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, C.; Kuang, H. P-MITE: A Database for Plant Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Su, W.; Kuang, H. Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements (MITEs) Have Been Accumulated through Amplification Bursts and Play Important Roles in Gene Expression and Species Diversity in Oryza Sativa. Mol Biol Evol 2012, 29, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onetto, C.A.; Ward, C.M.; Borneman, A.R. The Genome Assembly of Vitis Vinifera Cv. Shiraz. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Su, W.; Liao, Y.; Chougule, K.; Agda, J.R.A.; Hellinga, A.J.; Lugo, C.S.B.; Elliott, T.A.; Ware, D.; Peterson, T.; et al. Benchmarking Transposable Element Annotation Methods for Creation of a Streamlined, Comprehensive Pipeline. Genome Biol 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keidar-Friedman, D.; Bariah, I.; Kashkush, K. Genome-Wide Analyses of Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements Reveals New Insights into the Evolution of the Triticum-Aegilops Group. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohilla, M.; Mazumder, A.; Saha, D.; Pal, T.; Begam, S.; Mondal, T.K. Genome-Wide Identification and Development of Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements and Intron Length Polymorphic Markers in Tea Plant (Camellia Sinensis). Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutanaev, A.M.; Osbourn, A.E. Multigenome Analysis Implicates Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements (MITEs) in Metabolic Diversification in Eudicots. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E6650–E6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braich, S.; Baillie, R.C.; Spangenberg, G.C.; Cogan, N.O.I. A New and Improved Genome Sequence of Cannabis Sativa. GigaByte 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadagali, S.; Stelmach-Wityk, K.; Macko-Podgórni, A.; Cholin, S.; Grzebelus, D. Polymorphic Insertions of DcSto Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements Reveal Genetic Diversity Structure within the Cultivated Carrot. J Appl Genet 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.-Y.; O’Donoughue, L.S.; Bureau, T.E. Inter-MITE Polymorphisms (IMP): A High Throughput Transposon-Based Genome Mapping and Fingerprinting Approach. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2001, 102, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, A.; Zhao, Q.; Ross-Ibarra, J.; Doebley, J. Identification of a Functional Transposon Insertion in the Maize Domestication Gene Tb1. Nat Genet 2011, 43, 1160–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. Plant MITEs: Useful Tools for Plant Genetics and Genomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2003, 1, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanBuren, R.; Man Wai, C.; Wang, X.; Pardo, J.; Yocca, A.E.; Wang, H.; Chaluvadi, S.R.; Han, G.; Bryant, D.; Edger, P.P.; et al. Exceptional Subgenome Stability and Functional Divergence in the Allotetraploid Ethiopian Cereal Teff. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devos, K.M.; Qi, P.; Bahri, B.A.; Gimode, D.M.; Jenike, K.; Manthi, S.J.; Lule, D.; Lux, T.; Martinez-Bello, L.; Pendergast, T.H.; et al. Genome Analyses Reveal Population Structure and a Purple Stigma Color Gene Candidate in Finger Millet. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, W.C.; Swain, M.L.; Ma, D.; An, H.; Bird, K.A.; Curdie, D.D.; Wang, S.; Ham, H.D.; Luzuriaga-Neira, A.; Kirkwood, J.S.; et al. The Final Piece of the Triangle of U: Evolution of the Tetraploid Brassica Carinata Genome. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4143–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Ma, X.; Yssel, A.E.J.; Chaluvadi, S.R.; Johnson, M.S.; Gangashetty, P.; Hamidou, F.; Sanogo, M.D.; Zwaenepoel, A.; et al. Genome Sequence and Genetic Diversity Analysis of an Under-Domesticated Orphan Crop, White Fonio (Digitaria Exilis). Gigascience 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavallo, D.; Crescente, J.M.; Gantuz, M.; Leone, M.; Vanzetti, L.S.; Masuelli, R.W.; Asurmendi, S. Genomic Re-Assessment of the Transposable Element Landscape of the Potato Genome. Plant Cell Rep 2020, 39, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klai, K.; Zidi, M.; Chénais, B.; Denis, F.; Caruso, A.; Casse, N.; Mezghani Khemakhem, M. Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements (MITEs) in the Two Lepidopteran Genomes of Helicoverpa Armigera and Helicoverpa Zea. Insects 2022, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klai, K.; Chénais, B.; Zidi, M.; Djebbi, S.; Caruso, A.; Denis, F.; Confais, J.; Badawi, M.; Casse, N.; Mezghani Khemakhem, M. Screening of Helicoverpa Armigera Mobilome Revealed Transposable Element Insertions in Insecticide Resistance Genes. Insects 2020, 11, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelossi, J.; Forni, G.; Iannello, M.; Savojardo, C.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R.; Mantovani, B.; Luchetti, A.; Rota-Stabelli, O. Wood Feeding and Social Living: Draft Genome of the Subterranean Termite Reticulitermes Lucifugus (Blattodea; Termitoidae). Insect Mol Biol 2023, 32, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depotter, J.R.L.; Ökmen, B.; Ebert, M.K.; Beckers, J.; Kruse, J.; Thines, M.; Doehlemann, G. High Nucleotide Substitution Rates Associated with Retrotransposon Proliferation Drive Dynamic Secretome Evolution in Smut Pathogens. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouché, S.; Badet, T.; Oggenfuss, U.; Plissonneau, C.; Francisco, C.S.; Croll, D. Stress-Driven Transposable Element De-Repression Dynamics and Virulence Evolution in a Fungal Pathogen. Mol Biol Evol 2020, 37, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CBDRx | JL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr. Accession | Mb | MITEs | MITEs/Mb | Chr. Accesion | Mb | MITEs | MITEs/Mb | |

| NC_044371.1 | 101,21 | 1394 | 13 | CM022971.1 | 80,62 | 1934 | 23 | |

| NC_044375.1 | 96,35 | 998 | 10 | CM022969.1 | 83,00 | 1327 | 15 | |

| NC_044372.1 | 94,67 | 997 | 10 | CM022967.1 | 89,82 | 1370 | 15 | |

| NC_044373.1 | 91,91 | 1201 | 13 | CM022965.1 | 93,00 | 1612 | 17 | |

| NC_044374.1 | 88,18 | 1050 | 11 | CM022968.1 | 83,22 | 1320 | 15 | |

| NC_044377.1 | 79,34 | 1099 | 13 | CM022970.1 | 82,47 | 1334 | 16 | |

| NC_044378.1 | 71,24 | 844 | 11 | CM022973.1 | 69,09 | 1104 | 15 | |

| NC_044379.1 | 64,62 | 929 | 14 | CM022974.1 | 54,53 | 1192 | 21 | |

| NC_044376.1 | 61,56 | 861 | 13 | CM022972.1 | 70,97 | 1177 | 16 | |

| NC_044370.1 | 104,99 | 1423 | 13 | CM022966.1 | 91,28 | 1791 | 19 | |

| Totals | 854,49 | 10903 | 12,1 | 807,90 | 14444 | 17,2 1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).