Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biomarkers and Longevity

3. Definitions and Realizations of Table 4

4. Method of Management of Patients

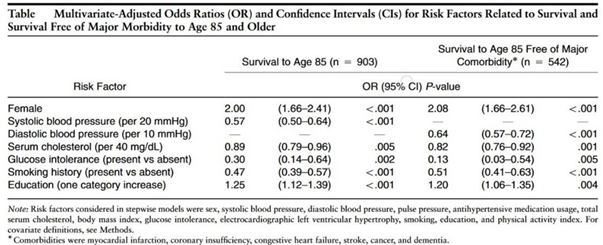

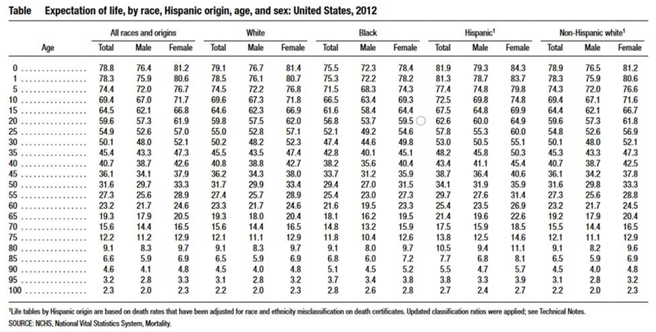

- 50 old year Hispanic male with diabetes, hypertension, smoking, and elevated total cholesterol

- 31.9 expected years, chronological age 50 expected age at death 81.9 with no risks

- 31.9(.3)(.57)(.47)(.89) = 2.28 years of expected life due to risk factors biologic age is 81.9 – 2.28 = 79.6 years

- Hs-Crp = 4

- Co-morbidity renal insufficiency, sleep apnea, renal insufficiency

- Six minute walk – 300 feet

- Elevated albumin to creatinine and creatinine 2.3

- Exercise, Hmg CoA reductase inhibitors, spironolactone, Sodium–Glucose transporter 2 Inhibitor, ARB and Clopidogrel (primary prevention due to high risk)

- Steady improvements of biomarkers will improve life expectancy.

5. Caveat

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dawber, T.R.; Meadors, G.F.; Moore, F. E Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951, 41, 279–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

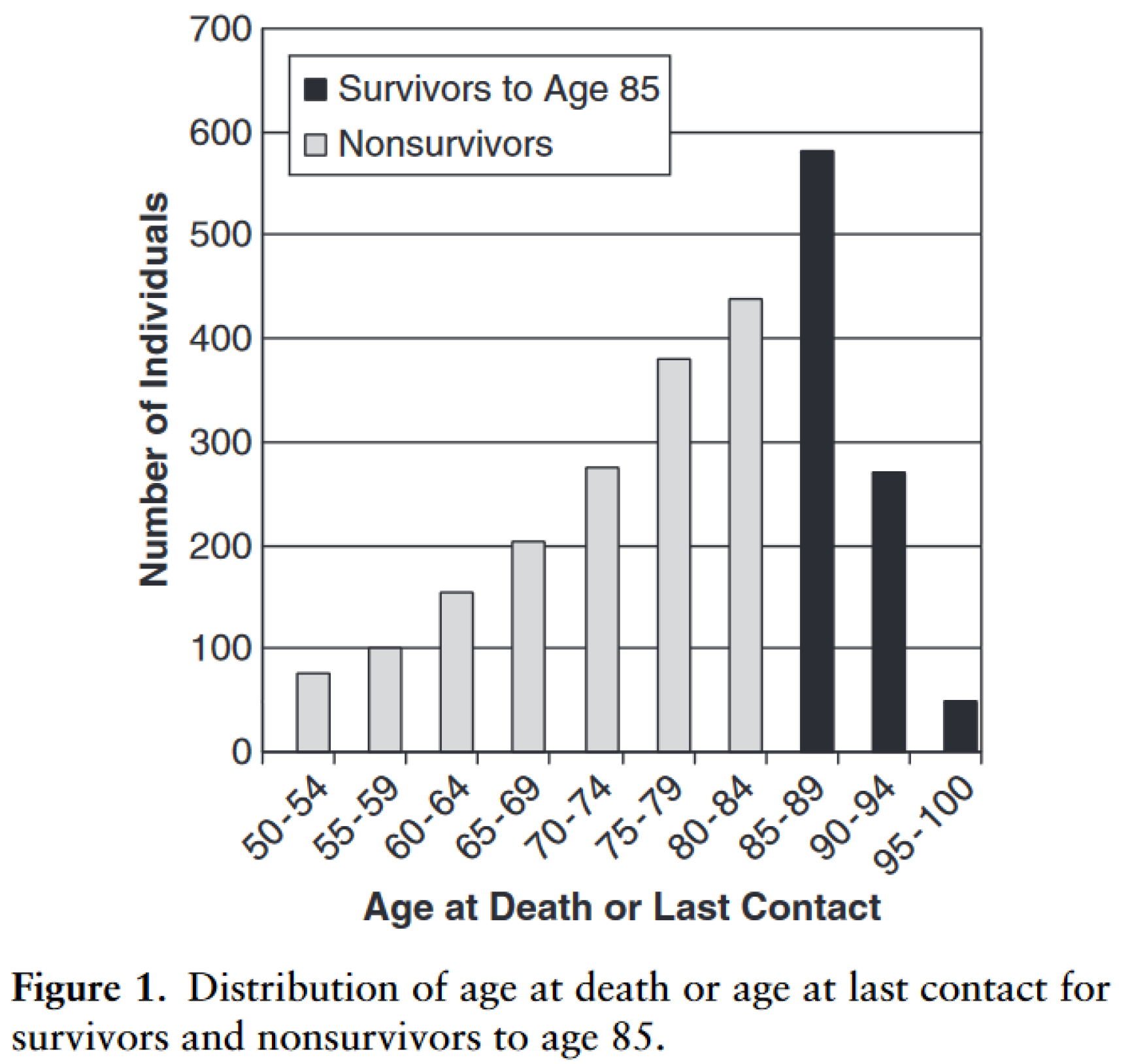

- Terry, D.F.; Pencina, M.J.; Vasan, R.S.; Murabito, J.M.; Wolf, P.A.; Hayes, M.K.; Levy, D.; D'Agostino, R.B.; Benjamin, E.J. Cardiovascular risk factors predictive for survival and morbidity-free survival in the oldest-old Framingham Heart Study participants. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005, 53, 1944–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, E.; Heron, M.; Xu, J. United States Life Tables, 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016, 65, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Härkänen T, Kuulasmaa K, Sares-Jäske L, et al Estimating expected life-years and risk factor associations with mortality in Finland: cohort study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033741. [CrossRef]

- Murata, S.; Ebeling, M.; Meyer, A.C.; et al. Blood biomarker profiles and exceptional longevity: comparison of centenarians and non-centenarians in a 35-year follow-up of the Swedish AMORIS cohort. GeroScience 2024, 46, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenborn, N.L.; Blackford, A.L.; Joshu, C.E.; Boyd, C.M.; Varadhan, R. Life expectancy estimates based on comorbidities and frailty to inform preventive care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022, 70, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N. Frailty as cardiovascular risk factor (and vice versa). Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases: Research into an Elderly Population. 2020:51-4.

- Yazdanyar, A.; Aziz, M.M.; Enright, P.L.; Edmundowicz, D.; Boudreau, R.; Sutton-Tyrell, K.; Kuller, L.; Newman, A.B. Association Between 6-Minute Walk Test and All-Cause Mortality, Coronary Heart Disease-Specific Mortality, and Incident Coronary Heart Disease. J Aging Health. 2014, 26, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tang, Y.; Liang, P.; Chen, J.; Fu, S.; Liu, B.; Feng, M.; Lin, B.; Lee, B.; Xu, A.; Lan, H.Y. The baseline levels and risk factors for high-sensitive C-reactive protein in Chinese healthy population. Immunity & Ageing. 2018, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zant, G.; Liang, Y. The role of stem cells in aging. Experimental hematology. 2003, 31, 659–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadini, G.P.; Mehta, A.; Dhindsa, D.S.; Bonora, B.M.; Sreejit, G.; Nagareddy, P.; Quyyumi, A.A. Circulating stem cells and cardiovascular outcomes: from basic science to the clinic. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 4271–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel, R.S.; Li, Q.; Ghasemzadeh, N.; Eapen, D.J.; Moss, L.D.; Janjua, A.U.; Manocha, P.; Al Kassem, H.; Veledar, E.; Samady, H.; Taylor, W.R. Circulating CD34+ progenitor cells and risk of mortality in a population with coronary artery disease. Circulation research. 2015, 116, 289–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasa, M.; Fichtlscherer, S.; Aicher, A.; Adler, K.; Urbich, C.; Martin, H. , et al. Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2001, 89, E1–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heiss, C.; Keymel, S.; Niesler, U.; Ziemann, J.; Kelm, M.; Kalka, C. Impaired progenitor cell activity in age-related endothelial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 45, 1441–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, N.; Kosiol, S.; Schiegl, T.; Ahlers, P.; Walenta, K.; Link, A. , et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005, 353, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cerhan, J.R.; Moore, S.C.; Jacobs, E.J.; Kitahara, C.M.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Adami, H.O.; Ebbert, J.O.; English, D.R.; Gapstur, S.M.; Giles, G.G.; Horn-Ross, P.L. A pooled analysis of waist circumference and mortality in 650,000 adults. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2014, 89, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. Stevens J, Katz EG, Huxley RR. Associations between gender, age and waist circumference. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2010, 64, 6–15.

- Raggi, P.; Gongora, M.; Gopal, A.; et al. Coronary Artery Calcium to Predict All-Cause Mortality in Elderly Men and Women. JACC. 2008, 52, 17–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, L.; Kalesan, B. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res 2009, 18, 148–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Ghilotti, F.; Grotta, A.; Bellavia, A.; Lagerros, Y.T.; Bellocco, R. Sleep duration, mortality and the influence of age. European journal of epidemiology. 2017, 32, 881–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequi-Dominguez, I.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Alvarez-Bueno, C.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Nunez de Arenas-Arroyo, S.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V. Accuracy of pulse wave velocity predicting cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020, 9, 2080. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, M.Y.; Kang, J.; Choi, H.I.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, B.J.; Sung, K.C.; Park, K.M. Association Between ECG Abnormalities and Mortality in a Low-Risk Population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e033306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahemuti, N.; Zou, J.; Liu, C.; Xiao, Z.; Liang, F.; Yang, X. Urinary Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio in Normal Range, Cardiovascular Health, and All-Cause Mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2348333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Inoue, K.; Streja, E.; Tsujimoto, T.; Kobayashi, H. Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio within normal range and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality among U. S. adults enrolled in the NHANES during 1999-2015. Ann Epidemiol. 2021, 55, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rehman, J.; Li, J.; Parvathaneni, L.; Karlsson, G.; Panchal, V.R.; Temm, C.J. , et al. Exercise acutely increases circulating endothelial progenitor cells and monocyte-/macrophage-derived angiogenic cells. J AmColl Cardiol. 2004, 43, 2314–8. [Google Scholar]

- Laufs, U.; Werner, N.; Link, A.; Endres, M.; Wassmann, S.; Jürgens, K. , et al. Physical training increases endothelial progenitor cells, inhibits neointima formation and enhances angiogensis. Circulation. 2004, 109, 220–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler, S.; Aicher, A.; Vasa, M.; Mildner-Rihm, C.; Adler, K.; Tiemann, M. , et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) increase endothelial progenitor cells via the PI 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Clin Invest. 2001, 108, 391–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Heizati, M.; Wang, L.; Nurula, M.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Abudoyreyimu, R.; Wu, Z.; Li, N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of spironolactone on blood pressure, glucose, lipids, renal function, fibrosis and inflammation in patients with hypertension and diabetes. Blood Pressure. 2021, 30, 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marumo, T.; Uchimura, H.; Hayashi, M.; Hishikawa, K.; Fujita, T. Aldosterone Impairs Bone Marrow–Derived Progenitor Cell Formation. Hypertension. 2006, 48, 490–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajsadeghi, S.; Chitsazan, M.; Chitsazan, M.; Salehi, N.; Amin, A.; Maleki, M.; Babaali, N.; Abdi, S.; Mohsenian, M. Changes of high sensitivity c-reactive protein during clopidogrel therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Research in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2016, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.H.; Krekel, N.; Kreuzer, J.; Fichtlscherer, S.; Schirmer, A.; Paar, W.D.; Hamm, C.W. Influence of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor ramipril on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) in patients with documented atherosclerosis. Clinical Research in Cardiology. 2005, 94, 336–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarok, M.I.; Rochmanti, M.; Yusuf, M.; Thaha, M. The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of ACE-I/ARBs Drug on hs-CRP and HDL-Cholesterol in CKD Patient. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology. 2021, 15, 3743–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cassano, V.; Armentaro, G.; Magurno, M.; Aiello, V.; Borrello, F.; Miceli, S.; Maio, R.; Perticone, M.; Marra, A.M.; Cittadini, A.; Hribal, M.L. Short-term effect of sacubitril/valsartan on endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness in patients with chronic heart failure. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2022, 13, 1069828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Zhong, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Xiao, X. The effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on biomarkers of inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 1045235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, S. Anti-inflammatory effects of empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Durante, W.; Behnammanesh, G.; Peyton, K.J. Effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors on vascular cell function and arterial remodeling. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021, 22, 8786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

| Repair | Number of Progenitor cells | Type of Progenitor Cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation and Immune Function | Hs-CRP interleukin-6 tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) | CBC - red cell diameter width lymphocyte to neutrophil ratio | ||

| Hematologic and Clotting Factors | Clonal hematopoiesis polycythemia | clotting factors D-dimer | ||

| Metabolic Nutritional | HgbA1c glucose | albumin albuminuria | Lipids Lipoprotein a |

CBC- minimum corpuscular volume, red cell count |

| Organ Maintenance | Creatinine Cystatin C | Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio | liver enzymes | BNP |

| Anthropomorphic | Body Mass Index | waist circumference | ||

| Environmental Factors | Educational Status | Social Economic | Nutritional intake | Minutes of daily exercise |

| Endothelial function | Coronary Artery Calcium | Pulse Wave Velocities | endothelial progenitor cells | |

| Sleep | Quantity | Rapid Eye Movement sleep | ||

| Number of Co-Morbidities | CAD, PVD, CVD CRI, COPD, Liver disease # |

Sleep apnea | ||

| Frailty | Six-Minute Walk | Hand Grip Strength | ||

| Electromagnetic | ECG |

| Biomarker | Change with Age | Mortality Prediction | ODDs Ratio Of All Cause Mortality | Correlation With Risk Factors | Integrated over Years Lived | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Co-Morbidities | Increases | yes | .89 – men 1.0 - women |

yes | yes | [6] |

| Frailty | Not Age Dependent | yes | .84 – men .88 - women |

yes | [6,7] | |

| Six-Minute Walk distance | Decreases | yes | >414 to <290 1.0 to .37 |

[8] | ||

| Hs-CRP>2.0 | Increases | yes | .7 | yes | [9] | |

| Circulating Stem Cells | Decreases | yes | .61 | yes | [10,11,12,13,14,15] | |

| Waist Circumference | Increases | yes | .60 –men .64 - women |

yes | [16,17] | |

| Coronary Artery Calcium 400 | Increases | yes | .9 | no | yes | [18] |

| Short Sleep <7 Long Sleep |

Increases < 65 years | Yes U shaped | .9 | [19,20] | ||

| Pulse Wave Velocity | Increases | Yes | .16 | Yes | Yes | [21] |

| ECG Findings RAE LAE LVH |

No |

Yes Yes Yes |

.67 .63 .53 |

yes | yes | [22] |

| Medication Intervention | Lowers Hs-CRP | Increases Stem cells | Anti-fibrotic | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | Yes | Yes | [25,26] | |

| HMG CoA Reductase Inhibitors | Yes | Yes | [27] | |

| Aldosterone inhibitor | Yes | Yes | Yes | [28,29] |

| Clopidogrel | Yes | Yes | [30] | |

| ACEI ARB ARNI | yes | Yes | [31,32,33] | |

| Sodium–Glucose Co-transporter 2 Inhibitor | yes | Yes | [34,35,36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).