Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Microorganisms

2.3. Cultivation Conditions

2.3.1. Inoculum

2.3.2. Cultivation Conditions - Fresh Biomas of Microorganisms

2.3.3. Immobilization Procedure- Growth of the R. arrhizus and B. brongniartii in the Presence of Polyurethane Foams with Different Porosity

2.3.4. Immobilization of B. bassiana Biomass in Agar-Agar

2.3.5. Immobilization of B. bassiana Biomass in Calcium Alginate

2.3.6. Pre-Incubation of Fresh Biomass of R. arrhizus

2.4. Procedures of Biotransformation

2.5. Semi-Preparative Biotransformation Procedures

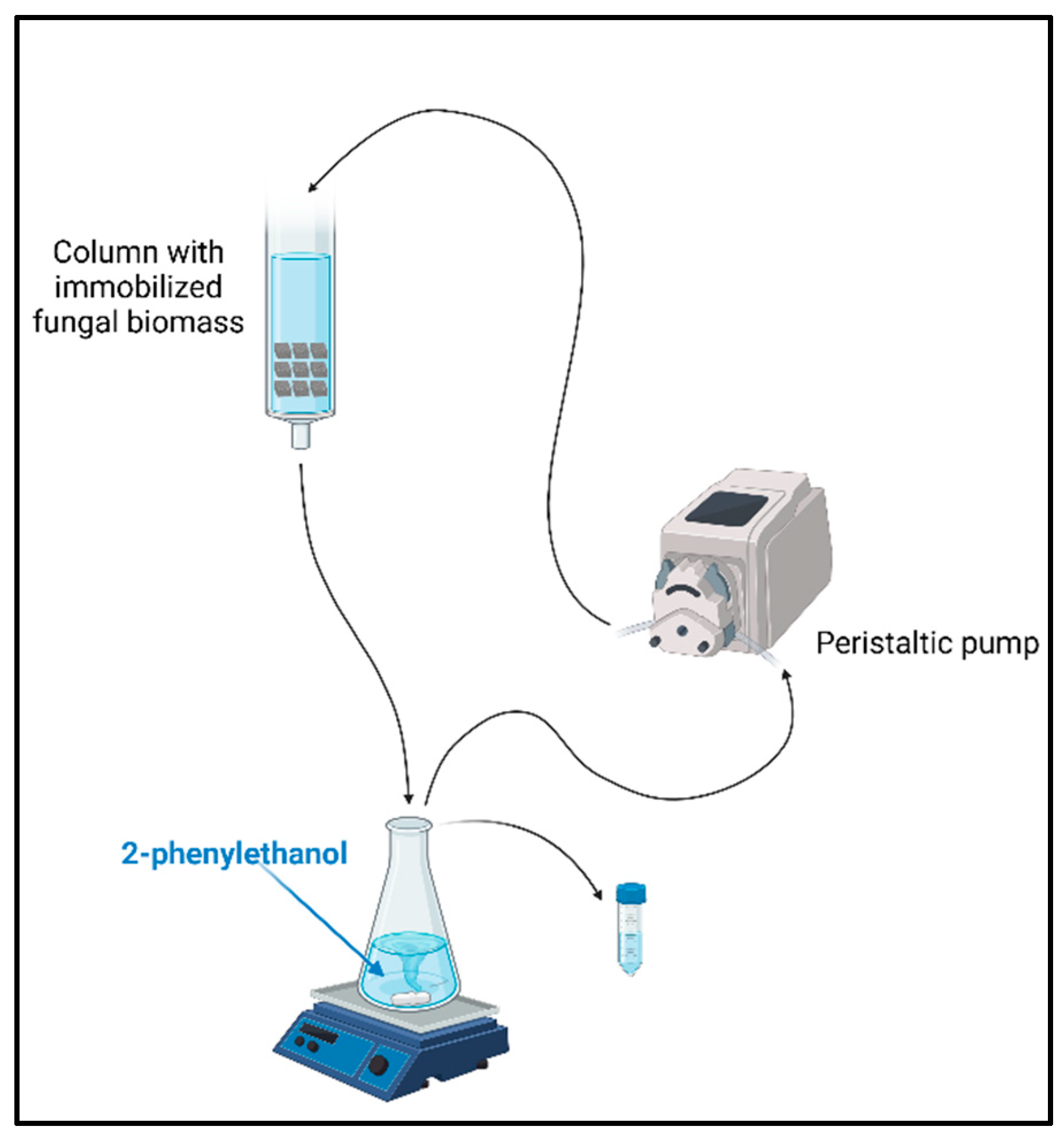

2.5.1. Simplified Flow Bioreactor for R. arrhizus

2.5.2. Batch Bioreactor for B. bassiana

2.6. Analytical Methods

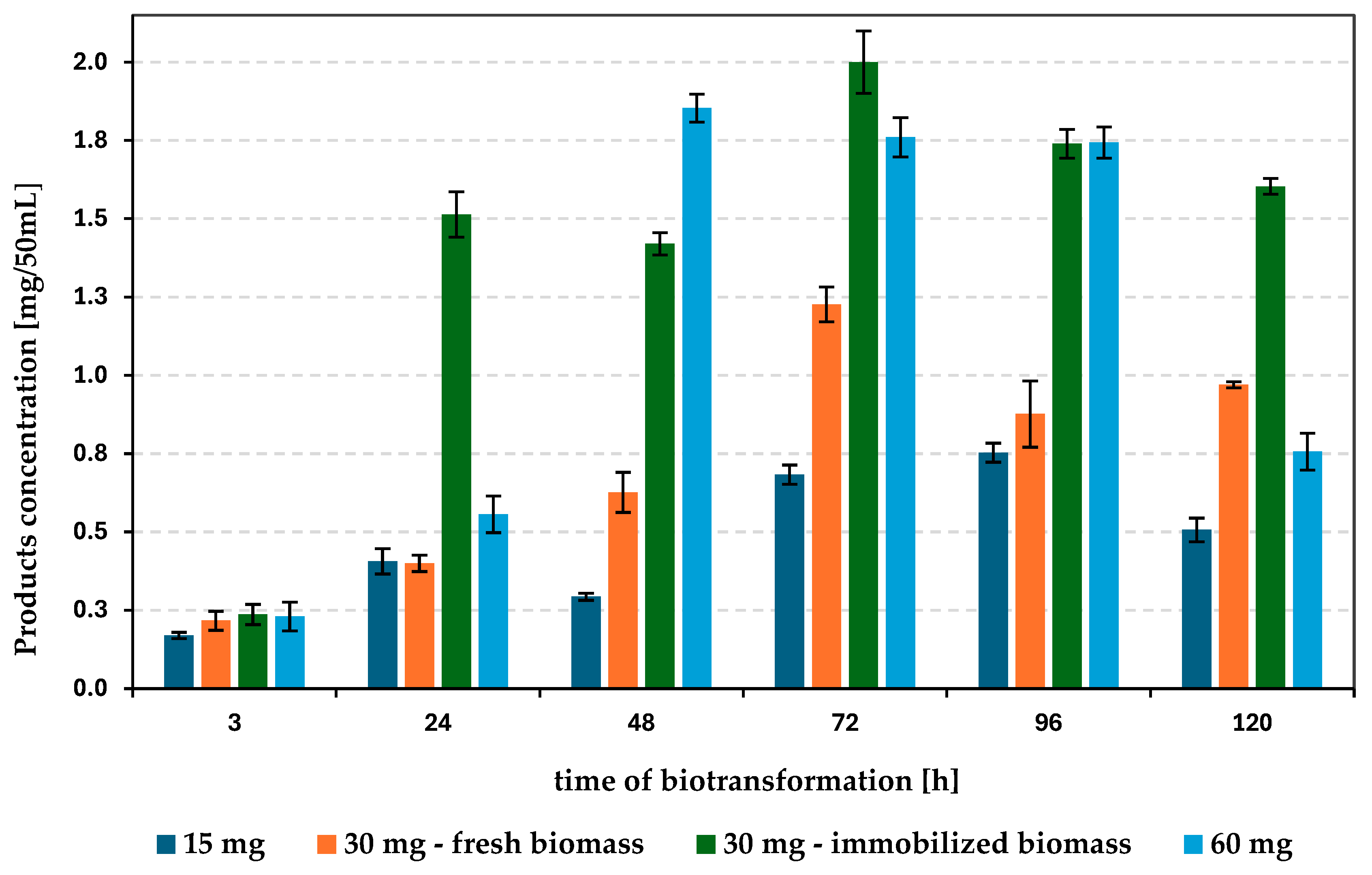

3. Results and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choudhary, M.; Gupta, S.; Dhar, M.K.; Kaul, S. Endophytic Fungi-Mediated Biocatalysis and Biotransformations Paving the Way Toward Green Chemistry. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrewe, M.; Julsing, M.K.; Bühler, B.; Schmid, A. Whole-Cell Biocatalysis for Selective and Productive C–O Functional Group Introduction and Modification. Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madavi, T.B.; Chauhan, S.; Keshri, A.; Alavilli, H.; Choi, K.Y.; Pamidimarri, S.D.V.N. Whole-Cell Biocatalysis: Advancements toward the Biosynthesis of Fuels. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining.

- Schwarz, F.M.; Müller, V. Whole-Cell Biocatalysis for Hydrogen Storage and Syngas Conversion to Formate Using a Thermophilic Acetogen. Biotechnol Biofuels 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczyńska, A.; Jadczyk, J.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M. Altering the Stereoselectivity of Whole-Cell Biotransformations via the Physicochemical Parameters Impacting the Processes. Catalysts 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, G.J.; Holland, H.L. The Biocatalytic Reactions of Beauveria Spp. J Mol Catal B Enzym 2000, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska, E.; Urbaniak, M.; Hoc, N.; Grzeszczuk, J.; Dymarska, M.; Stępień, Ł.; Pląskowska, E.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E.; Janeczko, T. Cascade Biotransformation of Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) by Beauveria Species. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszcza, E.; Dmochowska-Gładysz, J.; Bartmańska, A. Transformations of Steroids by Beauveria Bassiana. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung - Section C Journal of Biosciences 2005, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska, E.; Matera, A.; Sycz, J.; Kancelista, A.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E.; Janeczko, T. New 6,19-Oxidoandrostan Derivatives Obtained by Biotransformation in Environmental Filamentous Fungi Cultures. Microb Cell Fact 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świzdor, A.; Kołek, T.; Panek, A.; Białońska, A. Microbial Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation of Steroidal Ketones Using Beauveria Bassiana: Presence of an 11α-Hydroxyl Group Essential to Generation of D-Homo Lactones. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2011, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordon, S.; Popłoński, J.; Tronina, T.; Huszcza, E. Regioselective O-Glycosylation of Flavonoids by Fungi Beauveria Bassiana, Absidia Coerulea and Absidia Glauca. Bioorg Chem 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perz, M.; Krawczyk-Łebek, A.; Dymarska, M.; Janeczko, T.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E. Biotransformation of Flavonoids with -NO2, -CH3 Groups and -Br, -Cl Atoms by Entomopathogenic Filamentous Fungi. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łużny, M.; Tronina, T.; Kozłowska, E.; Dymarska, M.; Popłoński, J.; Łyczko, J.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E.; Janeczko, T. Biotransformation of Methoxyflavones by Selected Entomopathogenic Filamentous Fungi. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, N.A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Studies on Rhizopus Arrhizus Mediated Enantioselective Reduction of Arylalkanones. Tetrahedron 2001, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, N.A.; Patil, P.N.; Udupa, S.R.; Banerji, A. Biotransformations with Rhizopus Arrhizus: Preparation of the Enantiomers of 1-Phenylethanol and 1-(Fo-, m- and p-Methoxyphenyl)Ethanols. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 1995, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salokhe, P.R.; Salunkhe, R.S. Rhizopus Arrhizus Mediated SAR Studies in Chemoselective Biotransformation of Haloketones at Ambient Temperature. Biocatal Biotransformation 2022, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.N.; Lu, Y.J.; Chu, C.J.; Wu, Y.N.; Huang, H.L.; Fan, B.Y.; Chen, G.T. Biotransformation of Betulonic Acid by the Fungus Rhizopus Arrhizus CGMCC 3.868 and Antineuroinflammatory Activity of the Biotransformation Products. J Nat Prod 2021, 84, 2664–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, H.L. Biotransformations of Δ4-3-Ketosteroids by the Fungus Rhizopus Arrhizus. Acc Chem Res 1984, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, J.; Margaça, F.M.A.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Verde, S.C.; Barros, L. Applications of Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Olive Industry Wastes: A Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.S.; Ruscoe, R.E.; Turner, N.J. The Beauty of Biocatalysis: Sustainable Synthesis of Ingredients in Cosmetics. Nat Prod Rep 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.J.; Doyle, E.M.; O’Connor, K.E. Tyrosol to Hydroxytyrosol Biotransformation by Immobilised Cell Extracts of Pseudomonas Putida F6. Enzyme Microb Technol 2006, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anissi, J.; Sendide, K.; Ouardaoui, A.; Benlemlih, M.; El Hassouni, M. Production of Hydroxytyrosol from Hydroxylation of Tyrosol by Rhodococcus Pyridinivorans 3HYL DSM109178. Biocatal Biotransformation 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech-Baran, M.; Sykłowska-Baranek, K.; Pietrosiuk, A. Biotechnological Approaches to Enhance Salidroside, Rosin and Its Derivatives Production in Selected Rhodiola Spp. in Vitro Cultures. in Vitro Cultures. Phytochemistry Reviews 2015, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T. Effects of Salidroside Pretreatment on Expression of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and Permeability of Blood Brain Barrier in Rat Model of Focal Cerebralischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Hu, J.; Chen, L. Pharmacological Activities, Mechanisms of Action, and Safety of Salidroside in the Central Nervous System. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.J.; Aguilar, A.; Sánchez, F.G.; Díaz, A.N. Enantiomeric Fraction of Styrene Glycol as a Biomarker of Occupational Risk Exposure to Styrene. Chemosphere 2017, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, R. Improvement of (R)-Carbonyl Reductase-Mediated Biosynthesis of (R)-1-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol by a Novel Dual-Cosubstrate-Coupled System for NADH Recycling. Process Biochemistry 2012, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Xu, Y.; Mu, X.Q. Highly Enantioselective Conversion of Racemic 1-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol by Stereoinversion Involving a Novel Cofactor-Dependent Oxidoreduction System of Candida Parapsilosis CCTCC M203011. Org Process Res Dev 2004, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.K.; Fernandes, R.A.; Kumar, P. An Asymmetric Dihydroxylation Route to Enantiomerically Pure Norfluoxetine and Fluoxetine. Tetrahedron Lett 2002, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.M.; Zhang, J.D.; Fan, X.J.; Zheng, G.W.; Chang, H.H.; Wei, W.L. Highly Efficient Bioreduction of 2-Hydroxyacetophenone to (S)- and (R)-1-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol by Two Substrate Tolerance Carbonyl Reductases with Cofactor Regeneration. J Biotechnol 2017, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lee, J.; Chen, W.; Wood, T.K. Enantioconvergent Production of (R)-1-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol from Styrene Oxide by Combining the Solanum Tuberosum and an Evolved Agrobacterium Radiobacter AD1 Epoxide Hydrolases. Biotechnol Bioeng 2006, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Su, H.H.; Ou, X.Y.; Ni, Z.F.; Zong, M.H.; Lou, W.Y. Immobilization of Cofactor Self-Sufficient Recombinant Escherichia Coli for Enantioselective Biosynthesis of (R)-1-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Chen, Q.S.; Li, F.Z.; Ou, X.Y.; Zong, M.H.; Lou, W.Y. Using Deep Eutectic Solvents to Improve the Biocatalytic Reduction of 2-Hydroxyacetophenone to (R)-1-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol by Kurthia Gibsonii SC0312. Molecular Catalysis 2020, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Jia, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, D.; Ma, Y. Highly Enantioselective Double Reduction of Phenylglyoxal to (R)-1-Phenyl-1,2-Ethanediol by One NADPH-Dependent Yeast Carbonyl Reductase with a Broad Substrate Profile. Tetrahedron 2013, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żymańczyk-Duda, E.; Szmigiel-Merena, B.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Klimek-Ochab, M. Natural Antioxidants–Properties and Possible Applications. Journal of Applied Biotechnology & Bioengineering 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigiel-Merena, B.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Klimek-Ochab, M.; Majewska, P.; Zymanćzyk-Duda, E. Half-Preparative Scale Synthesis of (S)-1-Phenylethane-1,2-Diol as a Result of 2-Phenylethanol Hydroxylation with Aspergillus Niger (IAFB 2301) Assistance. Symmetry (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąb, A.; Szmigiel-Merena, B.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Żymańczyk-Duda, E. Biotransformation of 1- and 2-Phenylethanol to Products of High Value via Redox Reactions. Biotechnologia 2016, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubiak-Kozłowska, K.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Klimek-Ochab, M.; Olszewski, T.K.; Serafin-Lewańczuk, M.; Żymańczyk-Duda, E. (S)-Thienyl and (R)-Pirydyl Phosphonate Derivatives Synthesized by Stereoselective Resolution of Their Racemic Mixtures With Rhodotorula Mucilaginosa (DSM 70403) - Scaling Approaches. Front Chem 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin-Lewańczuk, M.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Lubiak-Kozłowska, K.; Majewska, P.; Klimek-Ochab, M.; Olszewski, T.K.; Żymańczyk-Duda, E. Phosphonates Enantiomers Receiving with Fungal Enzymatic Systems. Microb Cell Fact 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapponi, M.J.; Méndez, M.B.; Trelles, J.A.; Rivero, C.W. Cell Immobilization Strategies for Biotransformations. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 2022, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingaro, K.A.; Nicolaou, S.A.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Dissecting the Assays to Assess Microbial Tolerance to Toxic Chemicals in Bioprocessing. Trends Biotechnol 2013, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, S.A.; Gaida, S.M.; Papoutsakis, E.T. A Comparative View of Metabolite and Substrate Stress and Tolerance in Microbial Bioprocessing: From Biofuels and Chemicals, to Biocatalysis and Bioremediation. Metab Eng 2010, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofrichter, M.; Ullrich, R. Oxidations Catalyzed by Fungal Peroxygenases. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VELASCO B., R.; GIL G., J. H.; GARCÍA P., C.M.; DURANGO R., D.L. PRODUCTION OF 2-PHENYLETHANOL IN THE BIOTRANSFORMATION OF CINNAMYL ALCOHOL BY THE PLANT PATHOGENIC FUNGUS <I>Colletotrichum Acutatum</I>. Vitae 2010, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, M.; Ullrich, R.; Scheibner, K.; Hofrichter, M. Stereoselective Benzylic Hydroxylation of Alkylbenzenes and Epoxidation of Styrene Derivatives Catalyzed by the Peroxygenase of Agrocybe Aegerita. Green Chemistry 2012, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.M.; Howlett, B.J. Secondary Metabolism: Regulation and Role in Fungal Biology. Curr Opin Microbiol 2008, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Keller, N. Regulation of Secondary Metabolism in Filamentous Fungi. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2005, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.; Schmidt-Heydt, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Parra, R.; Geisen, R.; Magan, N. Impacts of Environmental Stress on Growth, Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Gene Clusters and Metabolite Production of Xerotolerant/Xerophilic Fungi. Curr Genet 2015, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyra, K.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Klimek-Ochab, M.; Zymańczyk-Duda, E. Biocatalyzed Kinetic Resolution of Racemic Mixtures of Chiral α-Aminophosphonic Acids. J Mol Catal B Enzym 2013, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, N.G.; Brown, N.A.; Colabardini, A.C.; Reis, T.; Savoldi, M.; Dinamarco, T.M.; Goldman, M.H.S.; Goldman, G.H. The Aspergillus Nidulans ATM Kinase Regulates Mitochondrial Function, Glucose Uptake and the Carbon Starvation Response. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, K. 2011.

- Chmiel, A. 1998.

- Bonin, S. Mikroorganizmy Immobilizowane. Agro Przemysł 2008, 8, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, J.I.; Miyamoto, K.; Ohta, H. Purification and Characterization of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase with a Broad Substrate Specificity Originated from 2-Phenylethanol-Assimilating Brevibacterium Sp. KU1309. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, K.; Hirano, J.I.; Ohta, H. Efficient Oxidation of Alcohols by a 2-Phenylethanol-Degrading Brevibacterium Sp. Biotechnol Lett 2004, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arun, K.B.; Madhavan, A.; Tarafdar, A.; Sirohi, R.; Anoopkumar, A.N.; Kuriakose, L.L.; Awasthi, M.K.; Binod, P.; Varjani, S.; Sindhu, R. Filamentous Fungi for Pharmaceutical Compounds Degradation in the Environment: A Sustainable Approach. Environ Technol Innov 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

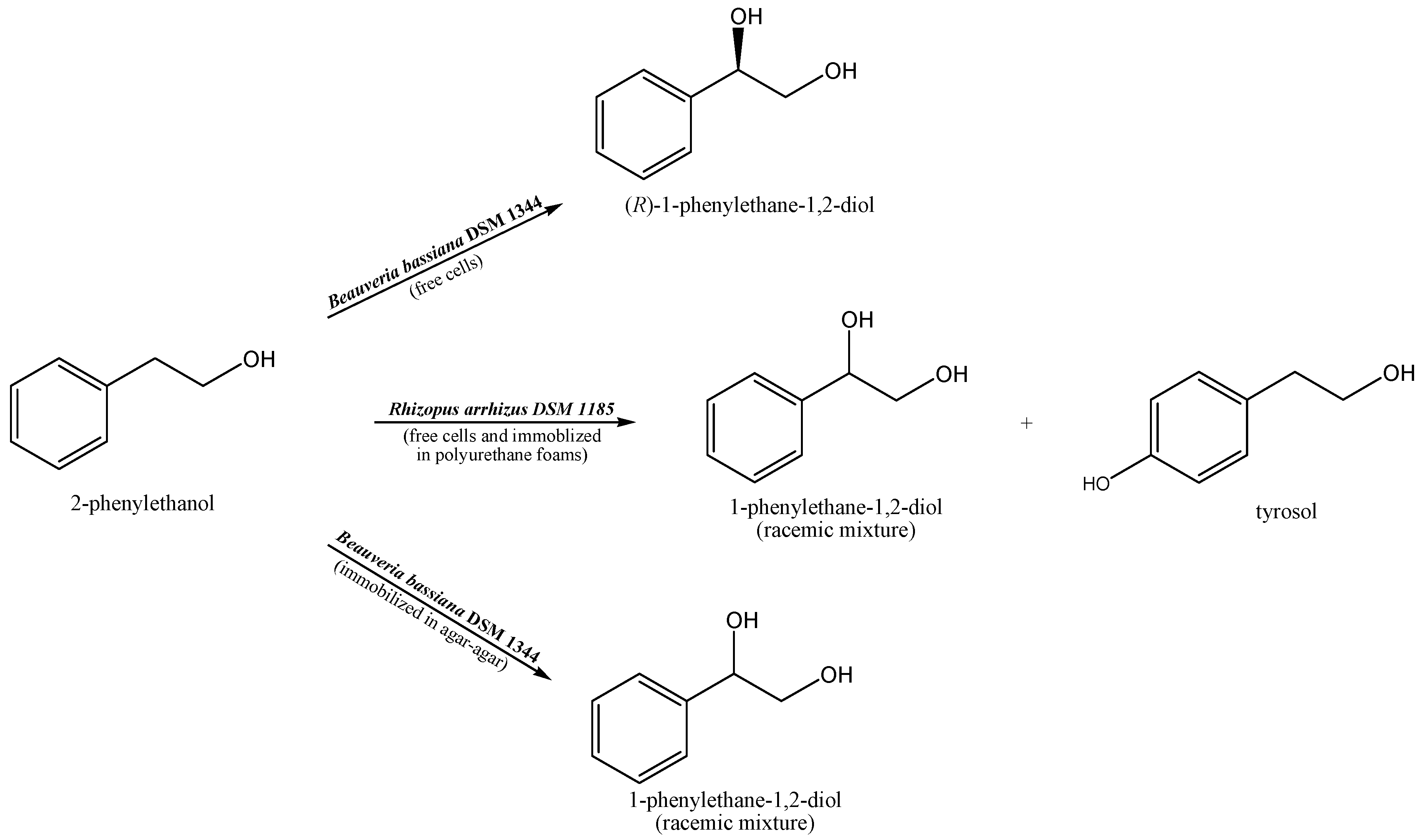

| Product |

(R)-1-phenylethane-1,2-diol | (R,S)-1-Phenylethane-1,2-diol | Tyrosol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocatalyst | ||||

|

B. bassiana DSM 1344 |

fresh biomass in flasks | immobilized biomass (agar-agar) |

||

| fresh biomass in bioreactor | ||||

|

R. arrhizus DSM 1185 |

fresh biomass | fresh biomass | ||

| immobilized biomass (polyurethan foams) |

immobilized biomass (polyurethan foams) |

|||

|

B. brongniartii DSM 6651 |

2-phenylethanol degradation - no desired product formation | |||

| (R)-1-phenylethane-1,2-diol (e.e. 99.9%) [mg / 600 mL] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Strain | Biotransformation Time [Days] | Product [mg] |

| B. bassiana (fresh cells) | 1 | 12.9 (±0.095) |

| 2 | 17.6 (±0.110) | |

| 3 | 28.8 (±0.078) | |

| 4 | 10.0 (±0.130) | |

| 5 | 5.1(±0.075) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).