1. Introduction

Fusion techniques are used to address degenerative conditions of the spine. In this setting, transforaminal interbody fusion is frequently performed, with proven effectiveness and reproducibility [

1]. Although well-developed techniques for Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusions (TLIFs) are used, technologies evolved to support advances in this surgical approach. Intraoperative CT navigation modality (IoCT) has increasingly been used to assist the insertion of pedicle screws in many types of approaches [

2,

3]. Computer assisted systems have been used since early 1995 [

4]. Several studies have compared the accuracy associated with IoCT use to freehand techniques and fluoroscopic guidance (FG) favoring the use of IoCT navigation for better material positioning [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Some studies show that the navigated modalities may achieve as much as 89% to 100% accuracy, while free-hand and FG varied from 28% to 94% [

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, the definition of accuracy remains unclear.

A systematic review comparing outcomes for FG, IoCT navigation and Robotic surgery, reported no statistical significance in surgical time, blood loss and length of stay. Statistical difference in complication rate was shown, however, authors reported low quality evidence in the studies included.[

4]. Complication rates has been analyzed in some studies, but they only used short times as much as 30 days complication rates [

6,

16,

17].

The IoCT navigation has been proven efficient in multiple level surgeries, however, we still lack a comprehensive evaluation specific to one of the most common instrumented cases: a single level TLIF (SL-TLIF) [

18,

19]

The aim of this study was to compare the operative outcomes on SL-TLIF between the loCT navigation and fluoroscopy. We hypothesized that, compared with the fluoroscopic guidance, increased accuracy achieved with navigation doesn’t influence the surgical time, time to discharge, revision rates and blood loss on SL-TLIF.

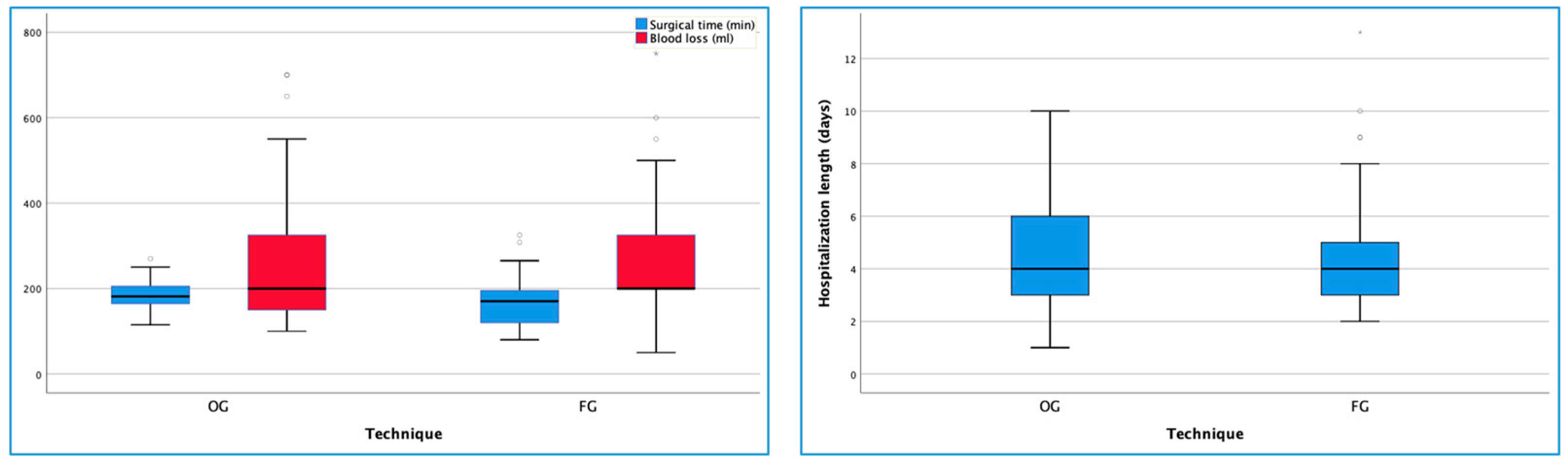

Figure 1.

Surgical time, blood loss and hospitalization length according to technique.

Figure 1.

Surgical time, blood loss and hospitalization length according to technique.

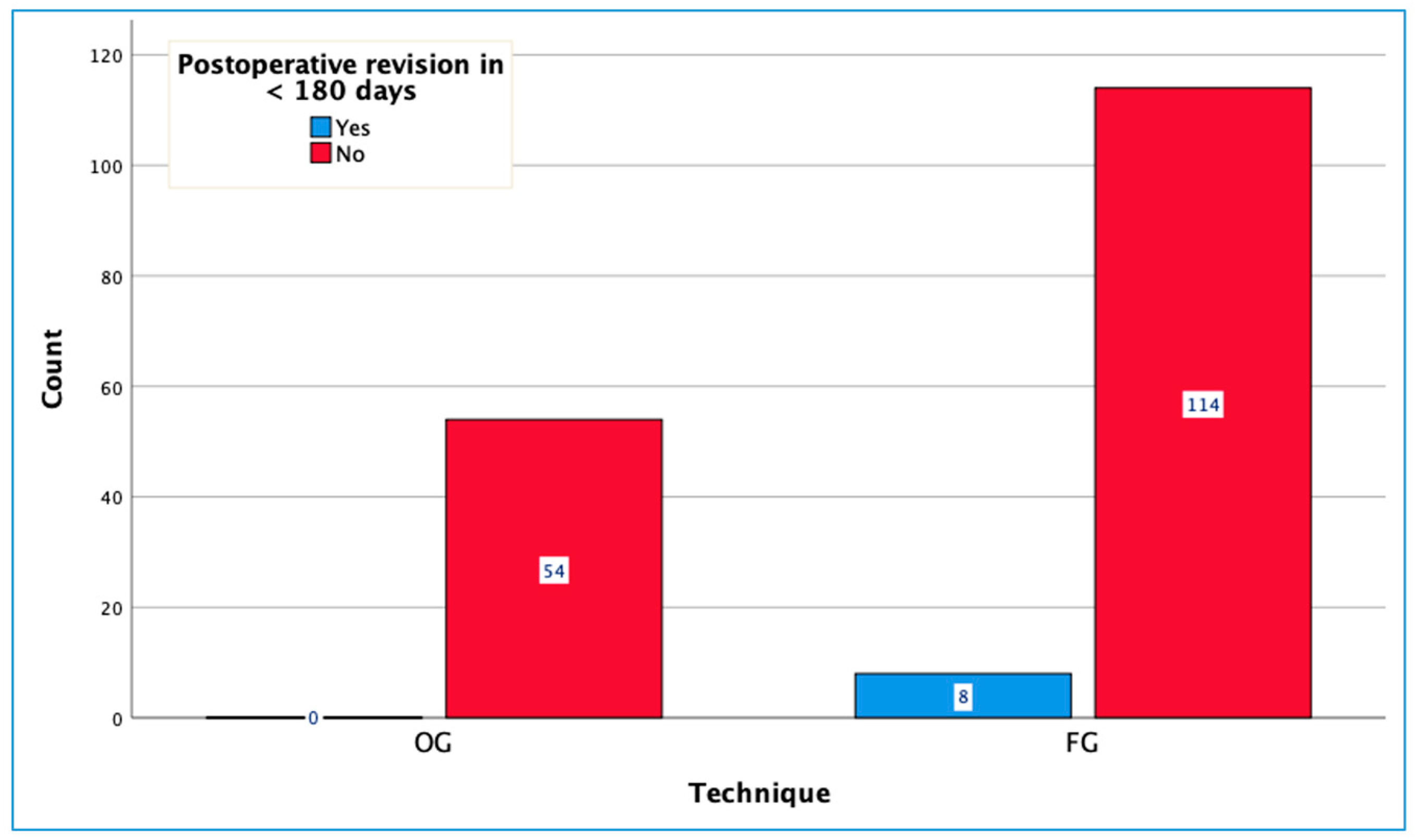

Figure 2.

Postoperative revision before 180 days according to technique.

Figure 2.

Postoperative revision before 180 days according to technique.

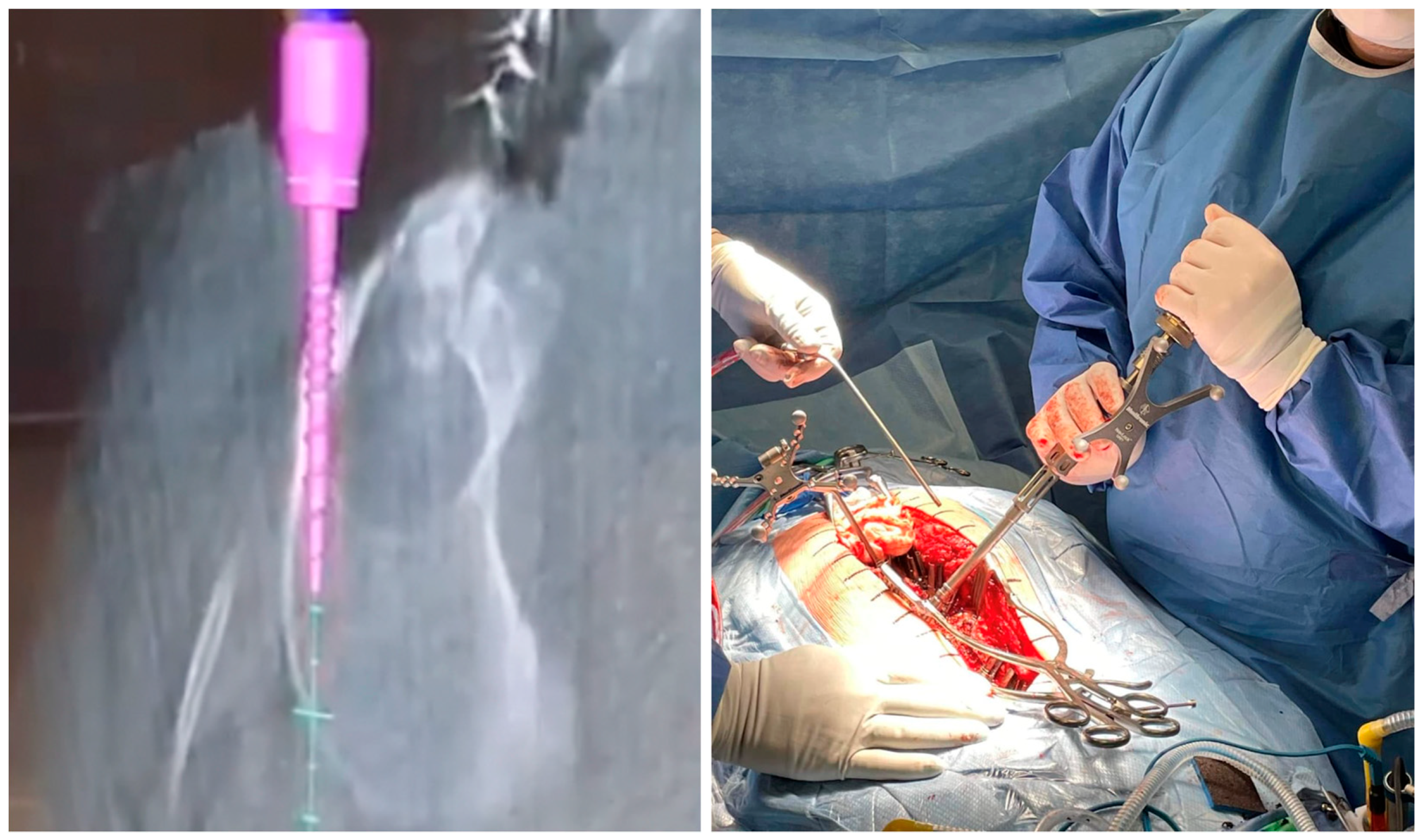

Figure 3.

Intra-operative images of a thoracic screw placement in a scoliosis surgery.

Figure 3.

Intra-operative images of a thoracic screw placement in a scoliosis surgery.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort, single center study on SL-TLIFs performed in our center between 2016 – 2020. Single levels of L2-3, L3-4, L4-5 and L5-S1 were included in this study with IoCT navigation (O-arm ©) or fluoroscopic guidance used for screw placement The primary outcome was the reoperation rate. Secondary outcomes were estimated blood loss (EBL), time to discharge and surgical time. Demographic and other data (level operated, approach, ASA) were also collected. The choice in between the fluoroscopic guidance or IoCT navigation was made by the surgeon. We acquired the O-arm © in June of 2017.

2.2. Surgical Technique

We are a quaternary referral center in Canada. Six surgeons, all fellowship trained in complex spine surgery, performed the surgeries. The type of approach (Midline vs Wiltse) was left to the discretion of the treating surgeons and was not standardized.

Moreover, the usage of surgical adjunct, including the usage of intraoperative navigation and fluoroscopy was also left to the discretion of the treating surgeon.

In the fluoro group, the screw placement was made under different guidance techniques (only lateral views, lateral plus AP views and freehand screw insertion with AP and lateral fluoroscopic control). In the fluoro group, the cage insertion was always made under fluoro guidance.

In the Nav group, the reference frame was fixed on the upper-level spinous process or the iliac crest. All the screws were inserted under IoCT navigation. For the cage insertion some surgeons used the same IoCT scan as a guide and others preferred to insert the cage under a lateral fluoro view.

All patients had fluoroscopic image control before the end of the procedure, and xray (AP and lateral) was performed before discharge.

2.3. Patient Selection

The inclusion criteria were: [

1] patients that presented with low back pain with or without radiculopathy, intermittent claudication, and/or neurological symptoms, and all of them didn’t improved after conservative treatment; [

2] clinical and/or radiographic diagnostic for lumbar disc herniation, spinal stenosis, degenerative spondylolisthesis and/or instability, and other degenerative changes; [

3] patients were at 18 – 90 years old; Exclusion criteria were trauma, infection, neoplasia, more than single level surgery (i.e. TLIF one level with decompression in two levels), deformity, anterior approaches, high degree spondylolisthesis. Minimally invasive (MIS) approaches were also excluded due to the possible variability in terms of surgical time, bleeding, and length of stay.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were retrospectively collected from our local database. One author was responsible for data collection from medical records. He wasn’t directly involved in the statistical analysis. Included pre-operative data were – age, sex, comorbidities according to the pre-operative anesthetic interview, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and diagnostic. Perioperative and postoperative data included: hospitalization, time to discharge, level operated, approach (midline or Wiltse), use of navigation or fluoroscopic guidance, blood loss, surgical time, and revisions.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with IBM, SPSS, V26.0.0.1 or DATAtab: Online Statistics Calculator. DATAtab e.U. Graz, Austria. URL

https://datatab.net. Descriptive statistics were obtained using central tendency and distribution measures corresponding to each variable type. Differences in proportions were calculated using Chi

2 and Fisher’s test when required. Differences in means were calculated using Student’s T test when applicable. Statistical significance was considered with p-values below 0.05.

3. Results

From six hundred and three patients operated for posterior lumbar instrumented fusions in our hospital between 2016 and 2020, 176 patients met the inclusion criteria. A total of 54 (30.68%) were in the Nav group, and 122 (69,32%) in the Fluoro group. No significant difference was found in demographic data in between both groups, with similar gender, ASA, and BMI in both groups. The mean age, BMI and ASA was 59,9 years, 29,94 and 2,18, respectively as seen in

Table 1.

The most frequent level operated was L4-L5 in 108 (61,36%) patients, second L5-S1 with 53 patients (30,11%).

Table 2 shows the main diagnostics operated and additional data.

Regarding the patient’s preoperative conditions, thirty of them (17,05%) had previous surgery at the same level. The surgical time was 194,43 ± 51,94 in the group previously operated and 165,22 ± 44,55 on the group without previous surgery, reaching statistical significance (p = 0,002), although without statistical significance for EBL and length of stay.

The mean surgical time was 170,2 ± 47,04 min, a statistically significant difference was found in the groups Fluoro 163,24 ± 49,59 min and Nav 185,93 ± 36,46 min (p = 0.003). The EBL (ml) global mean and standard deviation of 275,3 ± 180,01 ml. No statistically significant difference for Fluoro 277,28 ± 192,41 and Nav 270,83 ± 149,82 (p = 0.827) regarding EBL (

Table 3).

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics.

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics.

| |

Nav |

Fluoro |

P value

/ total |

| Mean |

SD |

N (%) |

Mean |

SD |

N (%) |

| Overall |

|

|

54 (30) |

|

|

122 (70) |

176 |

| Age |

58 |

12 |

|

61 |

12 |

|

0.147 |

| Gender |

Women |

|

|

28 (15) |

|

|

75 (43) |

0.232 |

| Men |

|

|

26 (15) |

|

|

47 (27) |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

30 |

6 |

|

30 |

6 |

|

0.965 |

| Weight |

Normal |

|

|

9 |

|

|

25 |

0.759 |

| Overweight |

|

|

19 |

|

|

33 |

| Moderate obesity |

|

|

15 |

|

|

32 |

| Severe obesity |

|

|

9 |

|

|

24 |

| Morbid obesity |

|

|

2 |

|

|

8 |

| ASA |

1 |

|

|

6 (4) |

|

|

8 (5) |

0.464 |

| 2 |

|

|

33 (20) |

|

|

71 (44) |

|

| 3 |

|

|

11 (7) |

|

|

32 (20) |

|

| Previous surgery at the same level. |

Yes |

|

|

12 (7) |

|

|

18 (10) |

0.224 |

| No |

|

|

42 (24) |

|

|

104 (59) |

|

| Nav: O-arm guided; Fluoro: Fluoroscopy guided |

Table 2.

Patients’ perioperative data.

Table 2.

Patients’ perioperative data.

| |

|

Nav |

Fluoro |

Total |

| |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Levels |

L2 - L3 |

1 |

0,57% |

1 |

0,57% |

2 |

1,14% |

| |

L3 - L4 |

5 |

2,84% |

8 |

4,55% |

13 |

7,39% |

| |

L4 - L5 |

26 |

14,77% |

82 |

46,59% |

108 |

61,36% |

| |

L5 - S1 |

22 |

12,5% |

31 |

17,61% |

53 |

30,11% |

| Approach |

MIDLINE |

38 |

21,59% |

105 |

59,66% |

143 |

81,25% |

| |

WILTSE |

16 |

9,09% |

17 |

9,66% |

33 |

18,75% |

| Dx |

Lysthesis |

34 |

19,32% |

88 |

50% |

122 |

69,32% |

| |

Stenosis |

12 |

6,82% |

18 |

10,23% |

30 |

17,05% |

| |

DH recidive |

5 |

2,84% |

7 |

3,98% |

12 |

6,82% |

| |

Foraminal DH |

2 |

1,14% |

4 |

2,27% |

6 |

3,41% |

| |

Other |

1 |

0,57% |

5 |

2,84% |

6 |

3,41% |

| Type of listhesis |

No listhesys |

19 |

10,8% |

33 |

18,75% |

52 |

29,55% |

Table 3.

Outcomes according to technique.

Table 3.

Outcomes according to technique.

| |

Technique |

p value |

| Nav |

Fluoro |

Total |

| Mean |

SD |

Count |

Mean |

SD |

Count |

Mean |

SD |

Count |

| Surgical time (min) |

186 |

36 |

|

163 |

50 |

|

170 |

47 |

|

0.001 |

| Blood loss (ml) |

271 |

150 |

|

277 |

192 |

|

275 |

180 |

|

0.810 |

| Hospitalization length (days) |

4 |

2 |

|

5 |

2 |

|

5 |

2 |

|

0.302 |

| Postoperative revision in < 180 days |

Yes |

|

|

0 |

|

|

8 |

|

|

8 |

0.050 |

| No |

|

|

54 |

|

|

114 |

|

|

168 |

| Nav: Navigated (O-arm guided); Fluoro: Fluoroscopy guided |

The global mean hospitalization time was 4.55 days for the entire cohort, with Fluoro 4,66 ± 2,48, and Nav 4,31 ± 1,77, without a significant difference (p = 0.363).

Regarding the reoperation rate six months after surgery, we collected data for any reoperation. We found a statistically significant difference with eight patients (6.6%) reoperated in the Fluoro group and no reoperation in the Nav group (p 0.050).

Specific causes for the revisions were: five related to screw mispositioning. One screw at L5 (in a L5-S1 TLIF) was replaced in the same hospitalization. Two adjacent segment disease, two pseudoarthrosis. For the other three cases, two were due to surgical site infection and one because of a hematoma formation.

In this cohort, two different approaches were performed: midline (MA) and Wiltse (WA). The Wiltse approach was increasingly used after the availability of navigation p = 0.014). We noted that the midline group had lower operating time, mean 166.43 ±49.41 than the Wiltse group, mean 186.52±30.52, (p = 0,027), see

Table 4. When comparing the operating time between the groups nav or fluoro, by approach (MA and WA), when navigated, the operating time was 189,11 for midline group, and 178,38 for the Wiltse group, whereas in Fluoro, the operating time was 158,23 for midline group, and 194,18 for the Wiltse group showing that

there was an interaction between the two variables for the surgical time (p = 0,033). No statistically significant difference was found in EBL (

p = 0,832) and time to discharge (p =

0,640).

Table 4.

Outcomes according to approach.

Table 4.

Outcomes according to approach.

| |

Approach |

p value |

| Midline |

Wiltse |

Total |

| Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

| Surgical time (min) |

166 |

49 |

|

187 |

31 |

|

170 |

47 |

|

0.020 |

| Blood loss (ml) |

283 |

193 |

|

243 |

101 |

|

275 |

180 |

|

0.101 |

| Hospitalization length (days) |

5 |

2 |

|

4 |

1 |

|

5 |

2 |

|

0.019 |

| Postoperative revision in < 180 days |

Yes |

|

|

7 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

8 |

0.643 |

| No |

|

|

136 |

|

|

32 |

|

|

168 |

Table 5.

Outcomes according to weight categories.

Table 5.

Outcomes according to weight categories.

| |

Weight (Categories) |

| |

Normal |

Overweight |

Moderate Obesity |

Severe obesity |

Morbid obesity |

Total |

| Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

| Surgical time (min) |

176 |

42 |

|

158 |

43 |

|

170 |

49 |

|

173 |

51 |

|

205 |

47 |

|

170 |

47 |

|

| Blood loss (ml) |

214 |

106 |

|

233 |

106 |

|

294 |

230 |

|

287 |

154 |

|

580 |

197 |

|

275 |

180 |

|

| Hospitalization (days) |

4 |

2 |

|

4 |

2 |

|

5 |

2 |

|

5 |

3 |

|

6 |

2 |

|

5 |

2 |

|

| Postoperative revision in < 180 days |

Yes |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

4 |

|

|

0 |

|

|

8 |

| No |

|

|

33 |

|

|

51 |

|

|

45 |

|

|

29 |

|

|

10 |

|

|

168 |

We found a moderate positive correlation of BMI and blood loss (r = 0.35, p < 0.001). There was no correlation with the surgical time (r = 0.11, p = 0.142), and length of stay (r = 0.14, p = 0.063). Morbid obesity group had a tendency for a higher EBL in both, nav and fluoro groups.

4. Discussion

From our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate revisions in 180 days after surgery as an outcome from SL-TLIFs performed with and without IoCT navigation. In our study, we found a statistically significant difference with eight patients (6.6%) reoperated in the Fluoro group and no reoperation in the Nav group (p 0.050). Regarding each revision, as discussed previously, five were directly related to screw mispositioning.

One patient had a screw replaced in the same hospitalization, the patient had no symptom but in the postoperative x-ray there was some concern, and the decision was made to bring the patient back to the OR, the patient was discharged home without any new symptom. Two adjacent segment disease with radiculopathy symptoms in none of them the screw was itself a concern, but there was remarkable degeneration in a short period after the surgery, two pseudoarthrosis manifested as pull outs with back pain symptoms. For the other three cases, two were due to surgical site infection and one because of a hematoma formation identified while the patient was still at the recovery room, the patient was brought back to the operating room; no major bleeding was found during the revision.

Some studies reported no difference on revision rate but analyzed only short or only the admission to the hospital period [

6,

16,

17]. Others [

19,

29], evaluating several levels surgeries, are in favor of navigation having an impact on reoperations. We also found a statistically significant difference in the groups Fluoro 163,24 ± 49,59 min and Nav 185,93 ± 36,46 min (p 0.003) regarding surgical time, this is in line with the literature.

Our study was designed to evaluate all revisions together, although we can’t draw conclusions on causative mechanisms for each complication; c-arm manipulation could increase infections in the fluoro group, for example. Our results are in line with the literature, as we found eight revisions (6,55% in 122 Fluoro patients) for all causes.

Indeed, our results shows that although there seems to be a larger operating time when using a navigated system in short fusion cases, the revision rate is higher when IoCT is not used, even in SL-TLIFs.

It’s well known that navigation technology increases the accuracy of pedicle screw placement [

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

20,

21], a recent [

19] systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated 14 studies, 12 RCTs (n=892 patients, 4,046 screws), found higher odds for screw accuracy and lower risk for facet joint violation for navigation group. However, only few studies have evaluated their clinical outcomes [

22,

23]. We haven’t found any study that evaluate the use of these techniques in single level lumbar surgeries with medium term outcome [

24].

A systematic review of outcomes with free hand (FH), Fluoro, Nav and Robotic Guided (RG) surgery [

4], didn’t analyze single level surgeries. They included 32 studies (24,008 patients), of which 22 (23,202 patients), 8 (680 patients), and 2 (126 patients) compared Nav/FH, RG/FH, and Nav/RG, respectively. In their subgroup analysis they included randomized and non-randomized studies, the length of surgery favored FG/FH in the randomized group, the length of stay favored Nav in both groups, the blood loss favored Nav in randomized group and the complication rate significantly favored Nav in non-randomized group but was not significant in randomized group.

There’s a conflicting literature regarding perioperative outcomes with and without the navigation use in spine surgery, our mean surgical time was 170,2 ± 47,04 min, Fluoro 163,24 ± 49,59 min and Nav 185,93 ± 36,46 min p=0.003, this highlights a 23 minute increase in surgical time, per case navigated. Without statistically significant difference for EBL and LoS. Xiao R. et.al. [

28] when evaluating cervical, thoracic, and lumbar screws, found no difference in surgical time or overall incidence of surgical site infection. They did find a significant difference in incidence in overall readmissions after 90 days (Nav 4,9% Vs. Fluoro/FH 7,4%) and reoperation for hardware failure on 90 days (Fluoro/FH 10,9%, NG 5,2%), they also found more than 50% reduction of the reoperation risk with navigation when compared to Fluoro/FH together, similar results were also found when comparing surgeries in less and more than 5 levels.

The Wiltse approach experienced an increase in its use after the availability of navigation. This factor might be confounded with individual practice not related to navigation availability. However, we didn’t find statistical differences in outcomes related to the approaches.

We are the first study to evaluate revisions in 180 days after surgery as an outcome from SL-TLIFs performed with and without IoCT navigation, all the surgeons are experienced in performing complex spine surgeries, and the variability in their practice allows us to consider our results as somehow reproducible in the real world. Our data bank allows us to appreciate all the data regarding complications and perioperative data are consistently evaluated in our center.

There are some limitations for our study. This is a single center study, with a retrospective design and no radiologic data regarding alignment, cage placement and screw position were evaluated for this study, although they were available in the patients filles. We couldn’t evaluate patient reported outcomes (PROs). It's important to note that we acquired our CAN system in 2017, with a potential learning curve for the surgeons and OR personnel when using the IoCT might have influenced our results.

Finally, we found that even in a relatively small center, navigation for SL-TLIF seems to be beneficial.

5. Conclusions

The use of IoCT navigation is certainly increasing worldwide as an established technology in high-income countries and progressively also in low-income ones.

This study found that despite a small but significant increase in surgical time, the use of navigation technique significatively reduced the rate of reoperations in SL-TLIFs, without adding infections, bleeding, or increasing the length of stay. It therefore seems to be a useful tool even in surgeries of smaller magnitude than what has previously been reported.

Conflicts of interest

No individual conflicts of interest. The ortho and neurosurgery department at Université de Sherbrooke receive research and teaching grants from Medtronic and Depuy-Synthes Spine.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This project was approved by the local research ethic board (#2023-4801).

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Abbreviations

| IoCT |

Intraoperative navigation by 3D tomography (IoCT) |

| SL-TLIF |

Single level - Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody fusion |

| Nav |

IoCT Navigation |

| Fluoro |

Fluoroscopic |

| FG |

Fluoroscopic guided |

| NG |

Navigation guided |

| EBL |

Estimated blood loss |

| MIS |

Minimally invasive surgery |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| LoS |

Length of stay |

| PROs |

Patient reported outcomes |

References

- Rosenberg WS, Mummaneni V. Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion: Technique, Complications, and Early Results.

- Xiao, R.; Miller, J.A.; Sabharwal, N.C.; Lubelski, D.; Alentado, V.J.; Healy, A.T.; Mroz, T.E.; Benzel, E.C. Clinical outcomes following spinal fusion using an intraoperative computed tomographic 3D imaging system. J. Neurosurgery: Spine 2017, 26, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, B.V.; Hsiue, P.P.; Upfill-Brown, A.M.; Chen, C.J.; Villalpando, C.; Lord, E.L.; Shamie, A.N.; Stavrakis, A.I.; Park, D.Y. Utilization trends and outcomes of computer-assisted navigation in spine fusion in the United States. Spine J. 2021, 21, 1246–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siccoli, A.; Klukowska, A.M.; Schröder, M.L.; Staartjes, V.E. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Perioperative Parameters in Robot-Guided, Navigated, and Freehand Thoracolumbar Pedicle Screw Instrumentation. World Neurosurg. 2019, 127, 576–587.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, R.; McDevitt, J.L.; Abecassis, Z.A.; Smith, Z.A.; Koski, T.R.; Fessler, R.G.; Dahdaleh, N.S. An Outcome and Cost Analysis Comparing Single-Level Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Using Intraoperative Fluoroscopy versus Computed Tomography–Guided Navigation. World Neurosurg. 2016, 94, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovonratwet, P.; Nelson, S.J.; Ondeck, N.T.; Geddes, B.J.; Grauer, J.N. Comparison of 30-Day Complications Between Navigated and Conventional Single-level Instrumented Posterior Lumbar Fusion. Spine 2018, 43, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohba, T.; Ebata, S.; Fujita, K.; Sato, H.; Haro, H. Percutaneous pedicle screw placements: accuracy and rates of cranial facet joint violation using conventional fluoroscopy compared with intraoperative three-dimensional computed tomography computer navigation. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 1775–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Chen, H.; Zhang, K.; Lu, J.; Mao, H.; Yang, H. Comparison between free-hand and O-arm-based navigated posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly cohorts with three-level lumbar degenerative disease. Int. Orthop. 2018, 43, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin MH, Hur JW, Ryu KS, Park CK. Prospective Comparison Study Between the Fluoroscopy-guided and Navigation Coupled With O-arm-guided Pedicle Screw Placement in the Thoracic and Lumbosacral Spines [Internet]. 2013. Disponível em: www.jspinaldisorders.com.

- Wu, M.-H.; Dubey, N.K.; Li, Y.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y.; Cheng, C.-C.; Shi, C.-S.; Huang, T.-J. Comparison of minimally invasive spine surgery using intraoperative computed tomography integrated navigation, fluoroscopy, and conventional open surgery for lumbar spondylolisthesis: a prospective registry-based cohort study. Spine J. 2017, 17, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqurashi, A.; A Alomar, S.; Bakhaidar, M.; Alfiky, M.; Baeesa, S.S. Accuracy of Pedicle Screw Placement Using Intraoperative CT-Guided Navigation and Conventional Fluoroscopy for Lumbar Spondylosis. Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, N.; Kamphuis, M.; Czabanka, M.; Hamm, B.; König, S.; Woitzik, J.; Synowitz, M.; Vajkoczy, P. Accuracy and workflow of navigated spinal instrumentation with the mobile AIRO® CT scanner. Eur. Spine J. 2015, 25, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, N.; Filardo, G.; Distefano, D.; Candrian, C.; Reinert, M.; Scarone, P. Use of Intraoperative CT Improves Accuracy of Spinal Navigation During Screw Fixation in Cervico-thoracic Region. Spine 2020, 46, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarenpää, I.; Laine, T.; Hirvonen, J.; Hurme, S.; Kotilainen, E.; Rinne, J.; Korhonen, K.; Frantzén, J. Accuracy of 837 pedicle screw positions in degenerative lumbar spine with conventional open surgery evaluated by computed tomography. Acta Neurochir. 2017, 159, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Kelft, E.; Costa, F.; Van der Planken, D.; Schils, F. A Prospective Multicenter Registry on the Accuracy of Pedicle Screw Placement in the Thoracic, Lumbar, and Sacral Levels With the Use of the O-arm Imaging System and StealthStation Navigation. Spine 2012, 37, E1580–E1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuman, W.H.; Valliani, A.A.; Chapman, E.K.; Martini, M.L.; Neifert, S.N.; Baron, R.B.; Schupper, A.J.; Steinberger, J.M.; Caridi, J.M. Intraoperative Navigation in Spine Surgery: Effects on Complications and Reoperations. World Neurosurg. 2022, 160, e404–e411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabah, N.M.; Khan, H.A.; Shost, M.; Beckett, J.; Mroz, T.E.; Steinmetz, M.P. Predictors of Operative Duration and Complications in Single-Level Posterior Interbody Fusions for Degenerative Spondylolisthesis. World Neurosurg. 2021, 151, e317–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dea, N.; Fisher, C.G.; Batke, J.; Strelzow, J.; Mendelsohn, D.; Paquette, S.J.; Kwon, B.K.; Boyd, M.D.; Dvorak, M.F.; Street, J.T. Economic evaluation comparing intraoperative cone beam CT-based navigation and conventional fluoroscopy for the placement of spinal pedicle screws: a patient-level data cost-effectiveness analysis. Spine J. 2016, 16, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matur, A.V.; Palmisciano, P.; Duah, H.O.; Chilakapati, S.S.; Cheng, J.S.; Adogwa, O. Robotic and navigated pedicle screws are safer and more accurate than fluoroscopic freehand screws: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2022, 23, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, D.; Jakubovic, R.; Gupta, S.; Alotaibi, N.M.; Cadotte, D.; da Costa, L.B.; George, R.; Heyn, C.; Howard, P.; Kapadia, A.; et al. Spinal intraoperative three-dimensional navigation: correlation between clinical and absolute engineering accuracy. Spine J. 2016, 17, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, F. Pedicle Screw Insertion: Is O-Arm–Based Navigation Superior to the Conventional Freehand Technique? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020, 144, e87–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, R.; Miller, J.A.; Sabharwal, N.C.; Lubelski, D.; Alentado, V.J.; Healy, A.T.; Mroz, T.E.; Benzel, E.C. Clinical outcomes following spinal fusion using an intraoperative computed tomographic 3D imaging system. J. Neurosurgery: Spine 2017, 26, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.T.; Drazin, D.; Shweikeh, F.; Pashman, R.; Johnson, J.P. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of minimally invasive percutaneous pedicle screw placement with intraoperative CT (O-arm) image guidance navigation. Neurosurg. Focus 2014, 36, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Wu, K.; Wang, H. O-arm navigation versus C-arm guidance for pedicle screw placement in spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Lee, R. Image-guided pedicle screws using intraoperative cone-beam CT and navigation. A cost-effectiveness study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 72, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanborn, M.R.; Thawani, J.P.; Whitmore, R.G.; Shmulevich, M.; Hardy, B.; Benedetto, C.; Malhotra, N.R.; Marcotte, P.; Welch, W.C.; Dante, S.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of confirmatory techniques for the placement of lumbar pedicle screws. Neurosurg. Focus 2012, 33, E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dea, N.; Fisher, C.G.; Batke, J.; Strelzow, J.; Mendelsohn, D.; Paquette, S.J.; Kwon, B.K.; Boyd, M.D.; Dvorak, M.F.; Street, J.T. Economic evaluation comparing intraoperative cone beam CT-based navigation and conventional fluoroscopy for the placement of spinal pedicle screws: a patient-level data cost-effectiveness analysis. Spine J. 2016, 16, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Miller, J.A.; Sabharwal, N.C.; Lubelski, D.; Alentado, V.J.; Healy, A.T.; Mroz, T.E.; Benzel, E.C. Clinical outcomes following spinal fusion using an intraoperative computed tomographic 3D imaging system. J. Neurosurgery: Spine 2017, 26, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, W.H.; Valliani, A.A.; Chapman, E.K.; Martini, M.L.; Neifert, S.N.; Baron, R.B.; Schupper, A.J.; Steinberger, J.M.; Caridi, J.M. Intraoperative Navigation in Spine Surgery: Effects on Complications and Reoperations. World Neurosurg. 2022, 160, e404–e411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).