Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

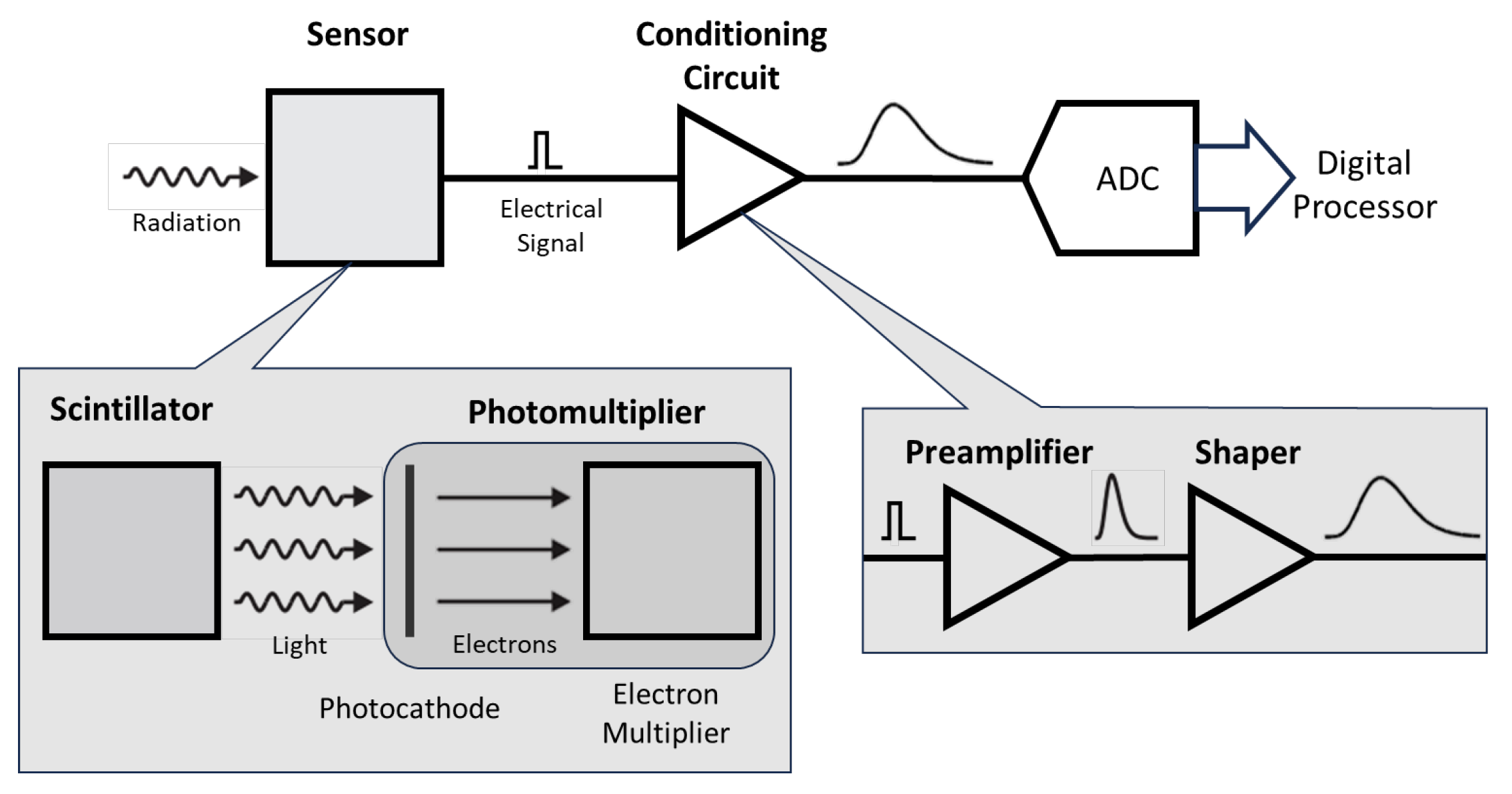

2.1. Detector Simulation

2.1.1. Data Events Generation

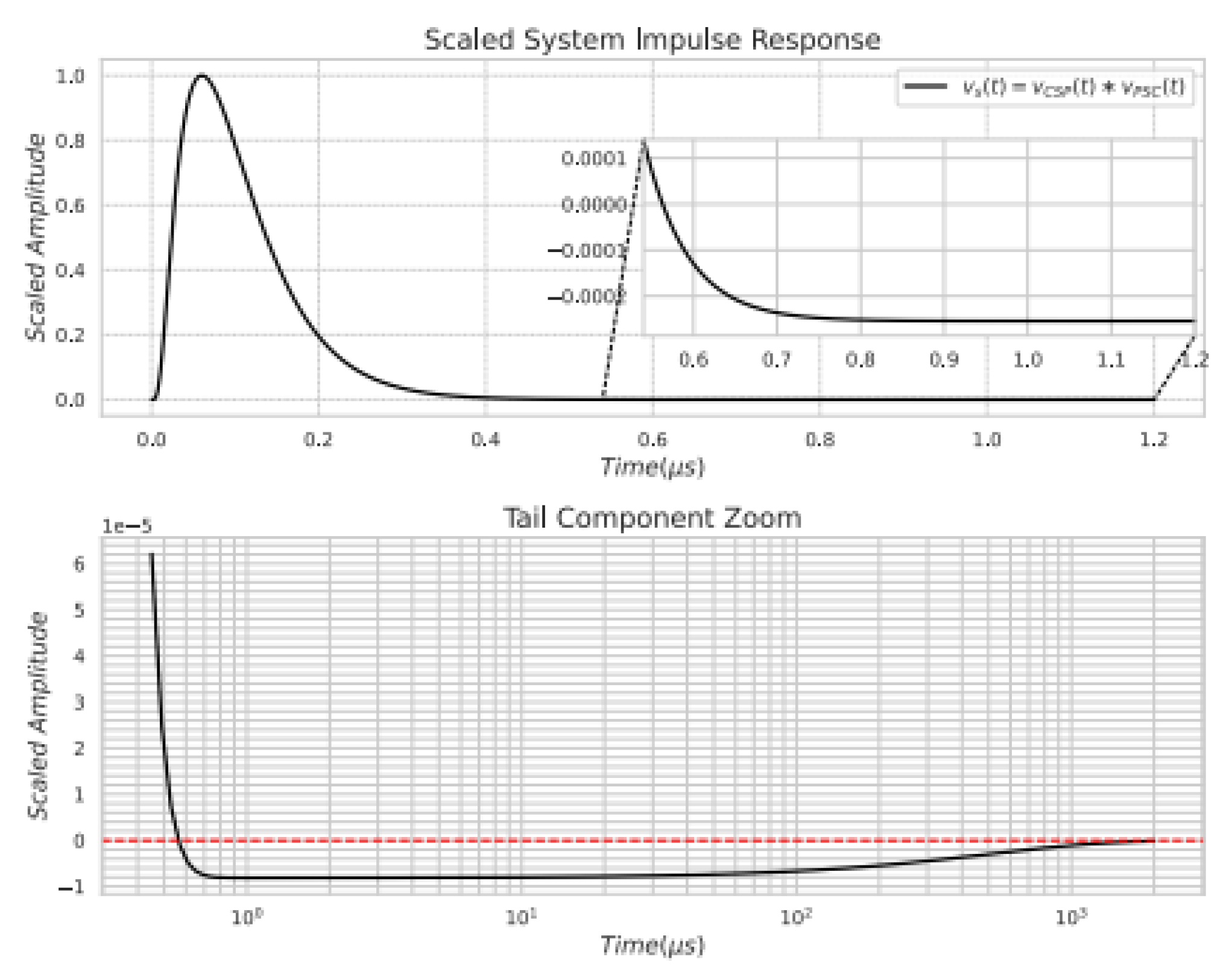

2.1.2. Convolutional Model

a. Input Electrical Pulse

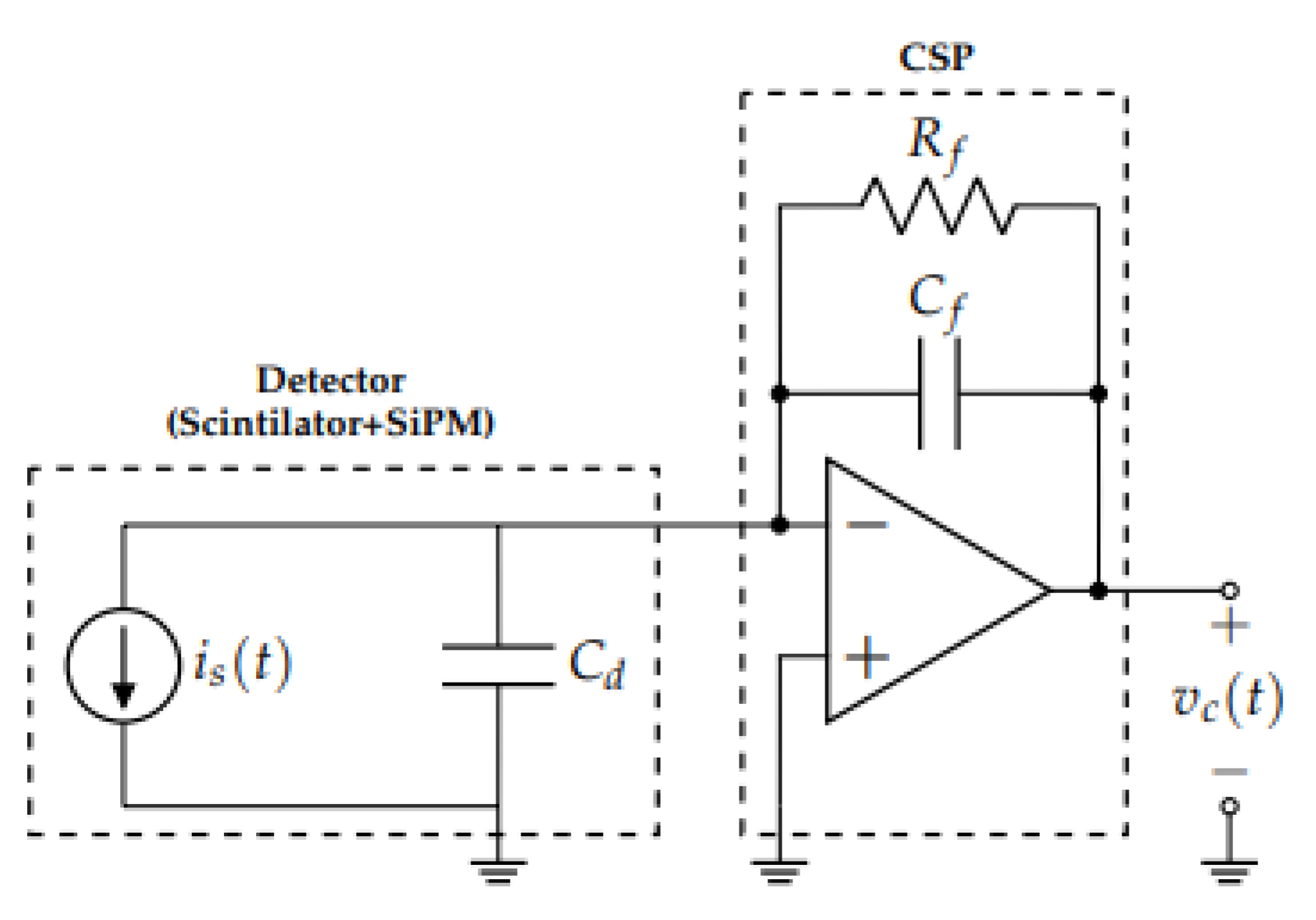

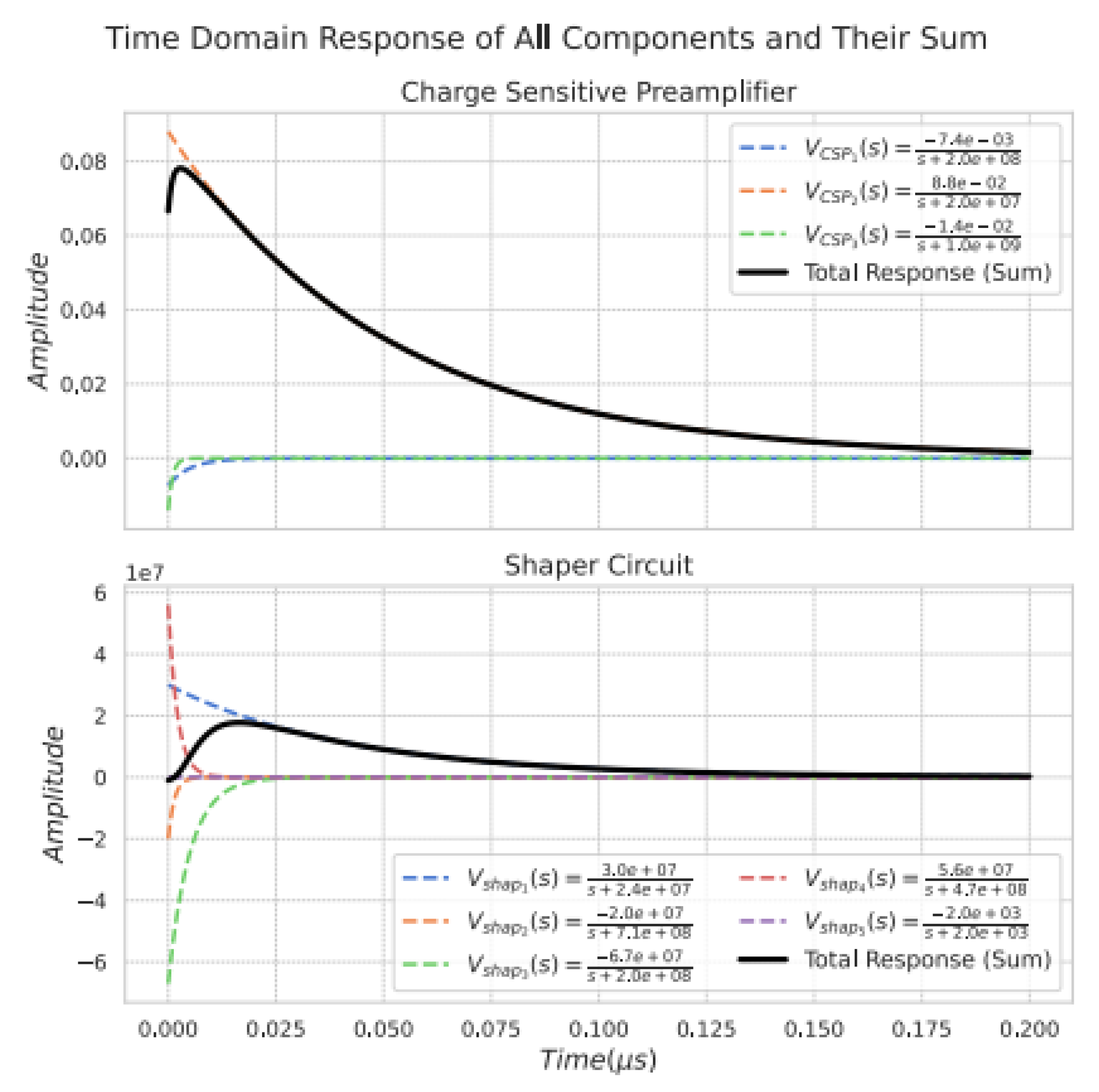

b. Charge Sensitive Preamplifier

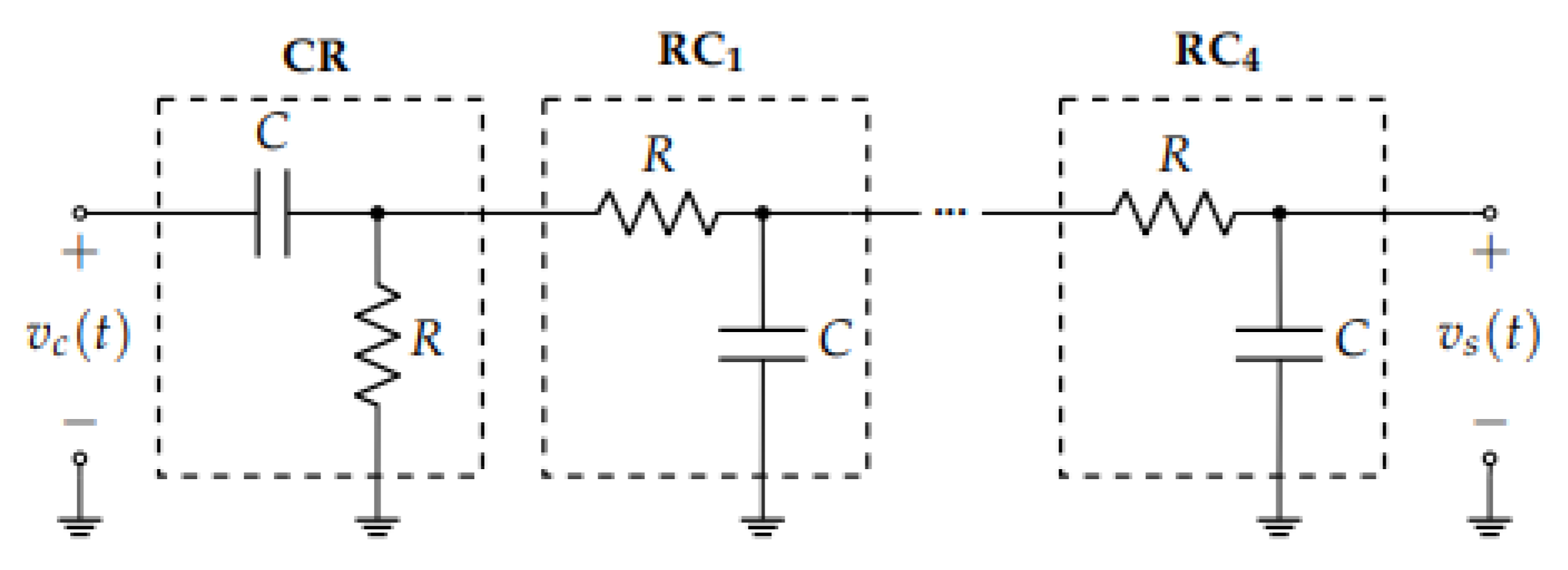

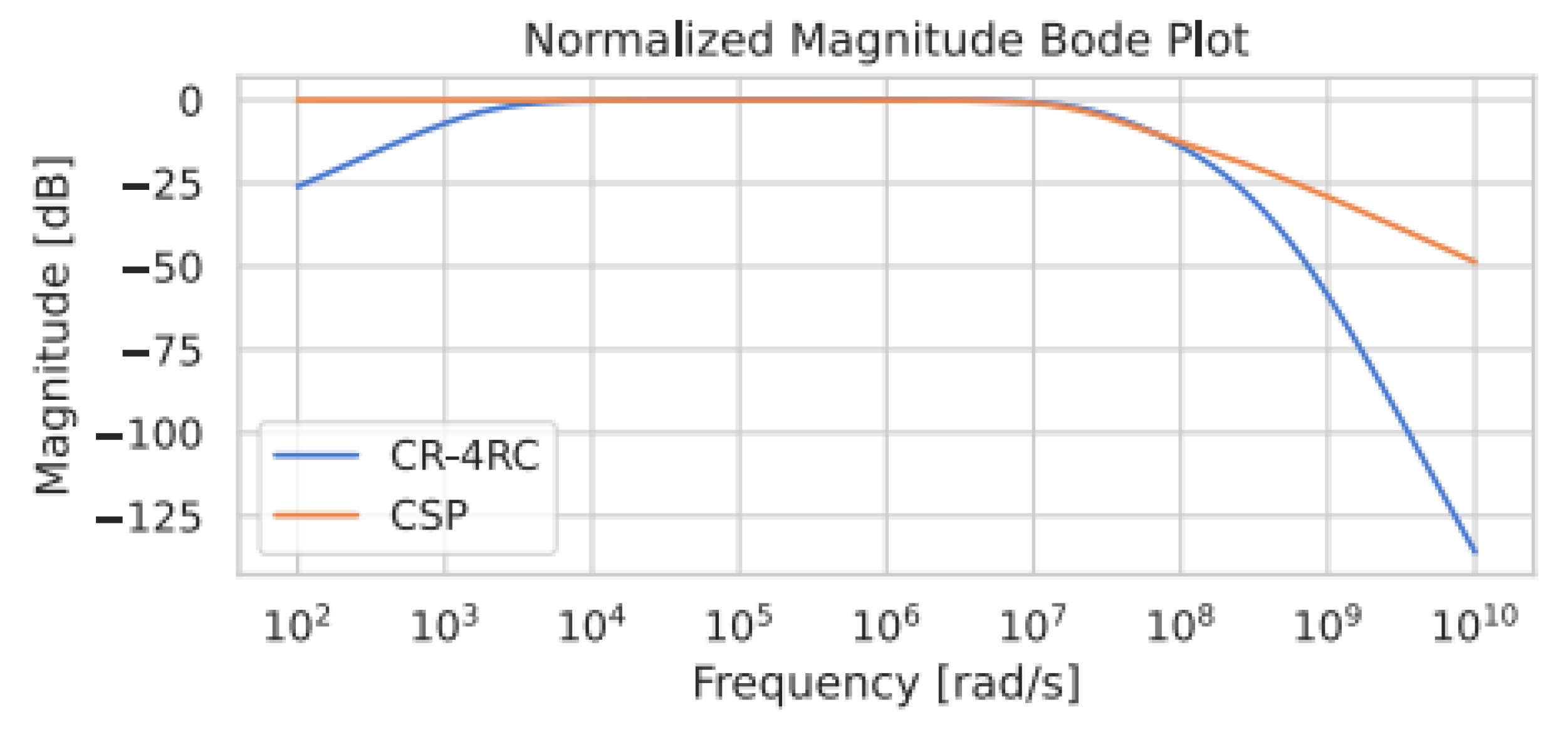

c. Pulse Shaper Circuit

2.1.2.4. d. Noise Modeling

2.2. Digital Processing

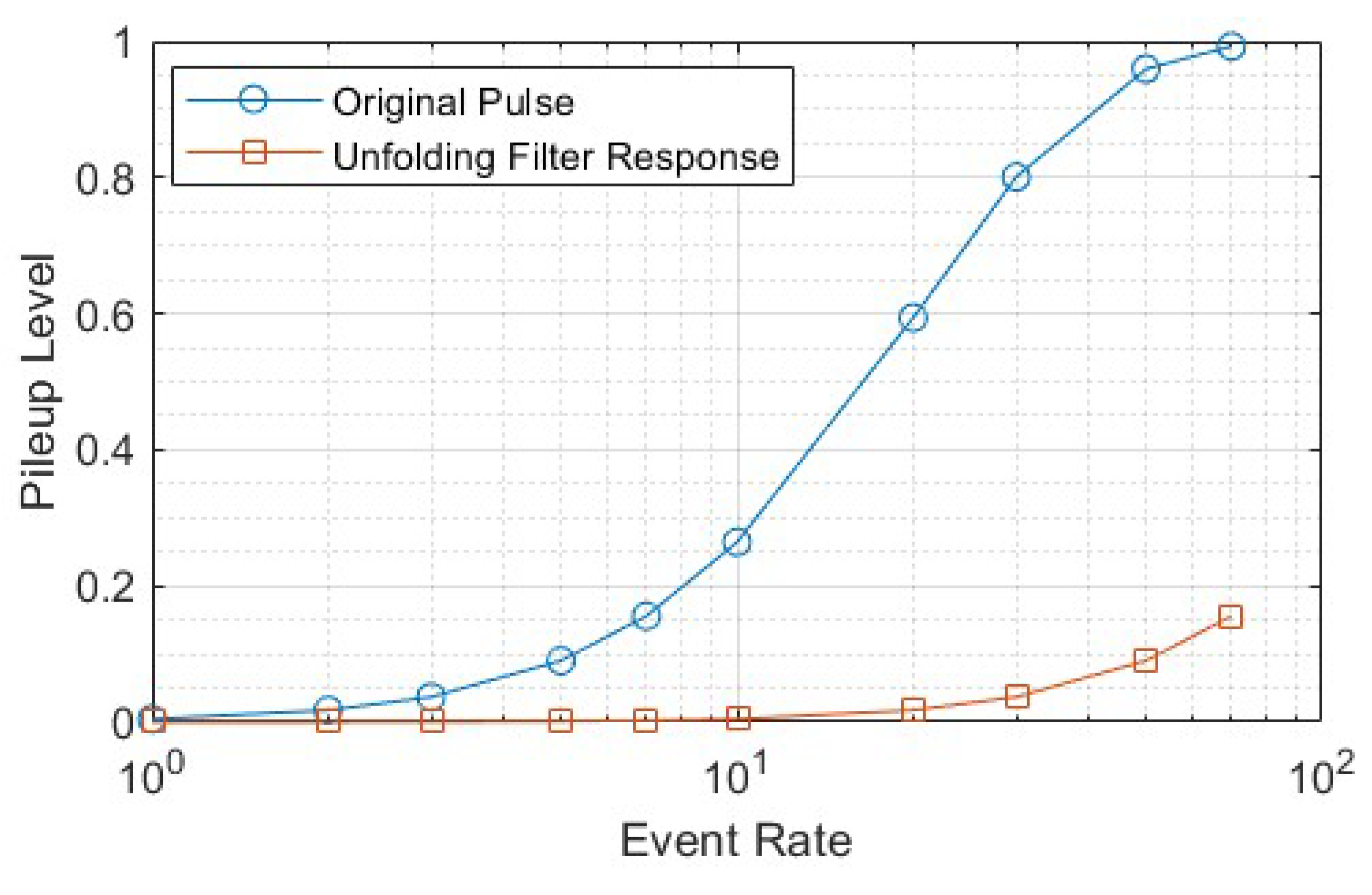

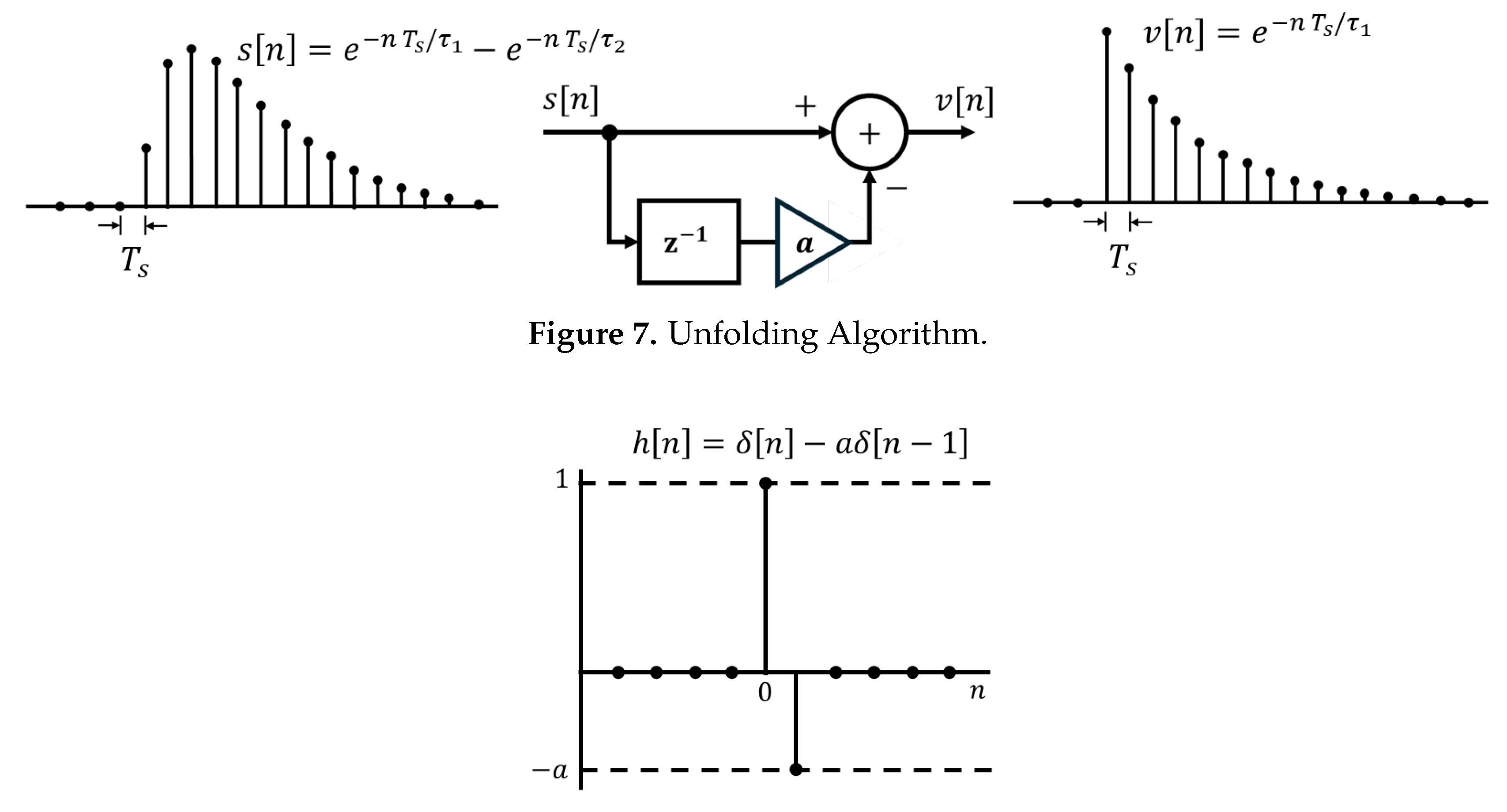

2.2.1. Unfolding Algorithm

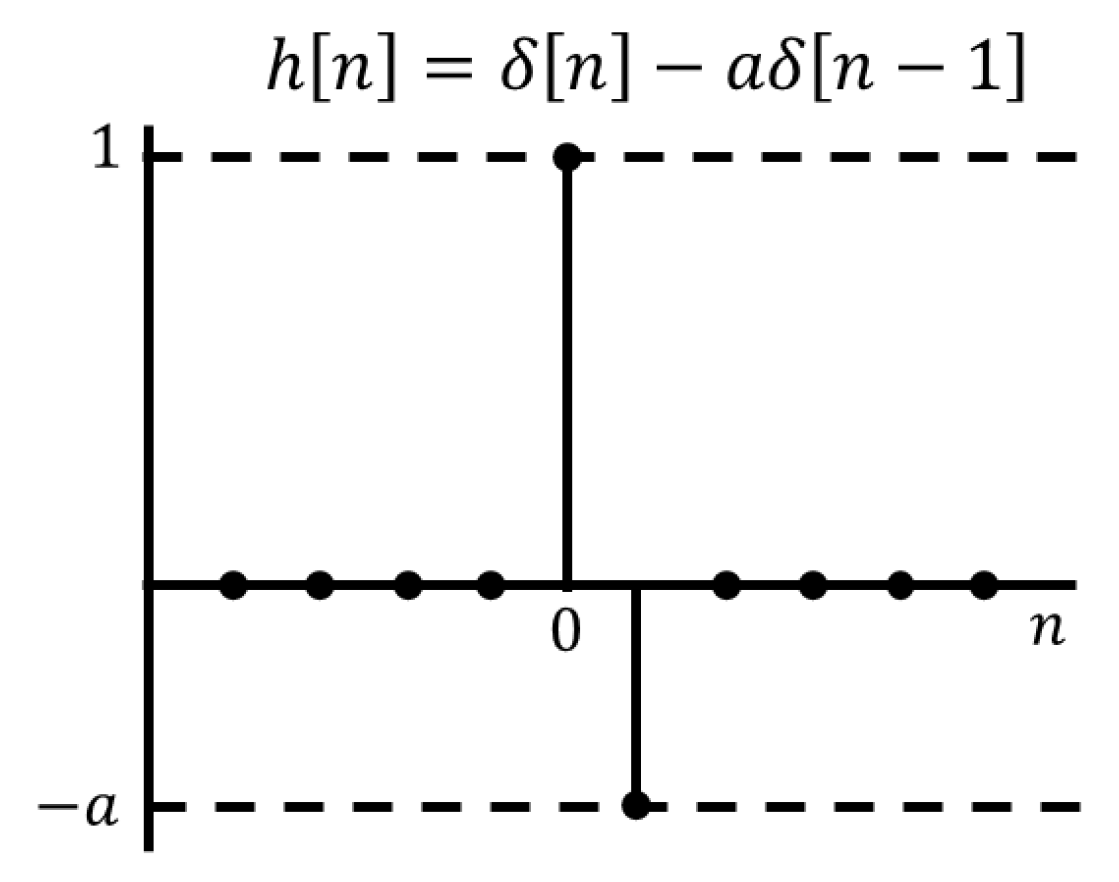

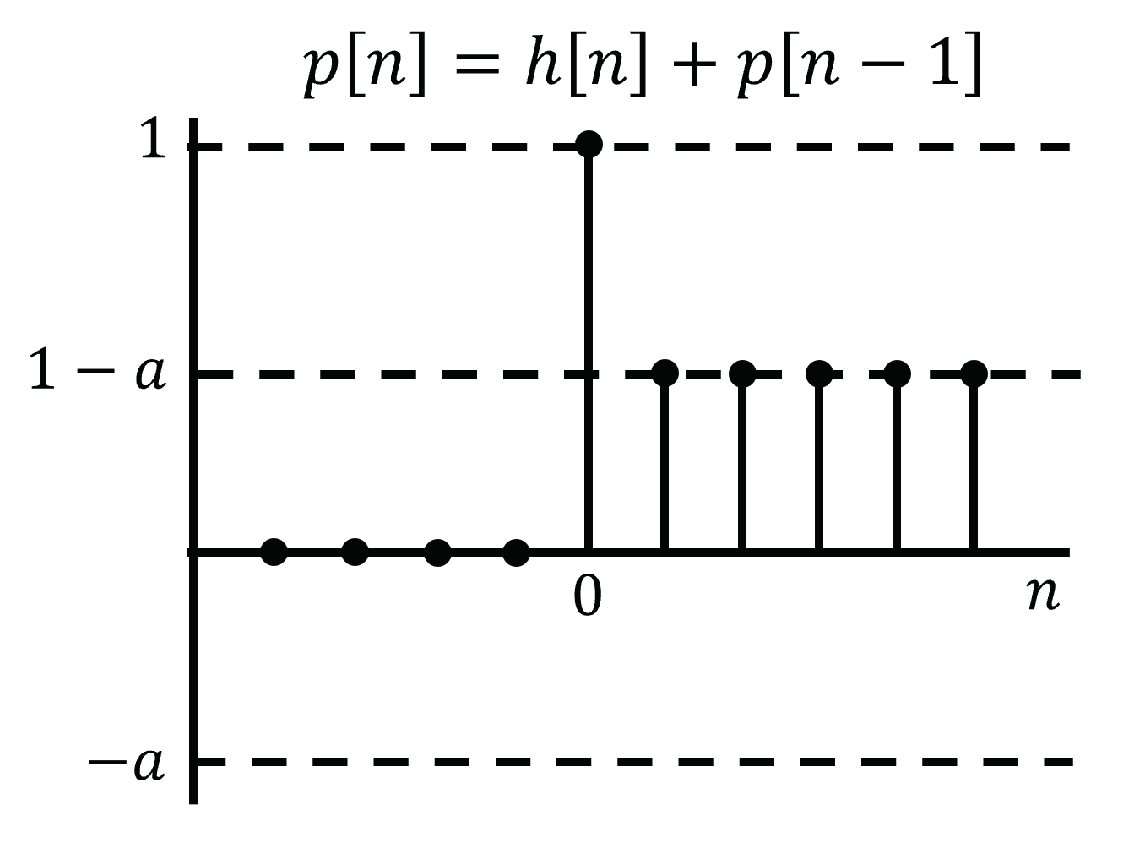

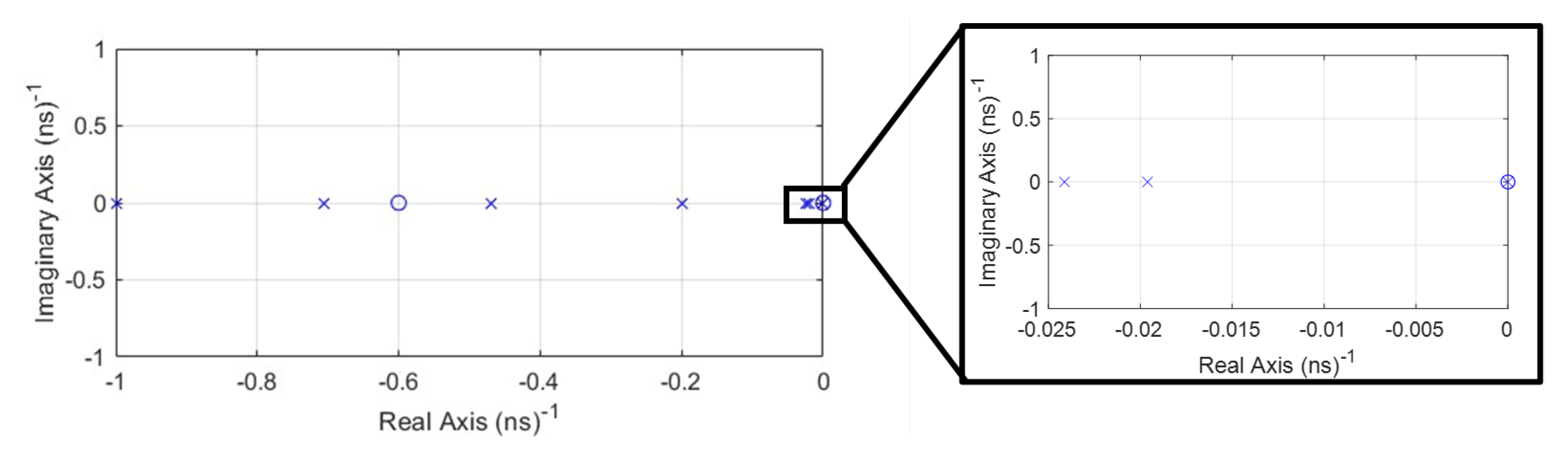

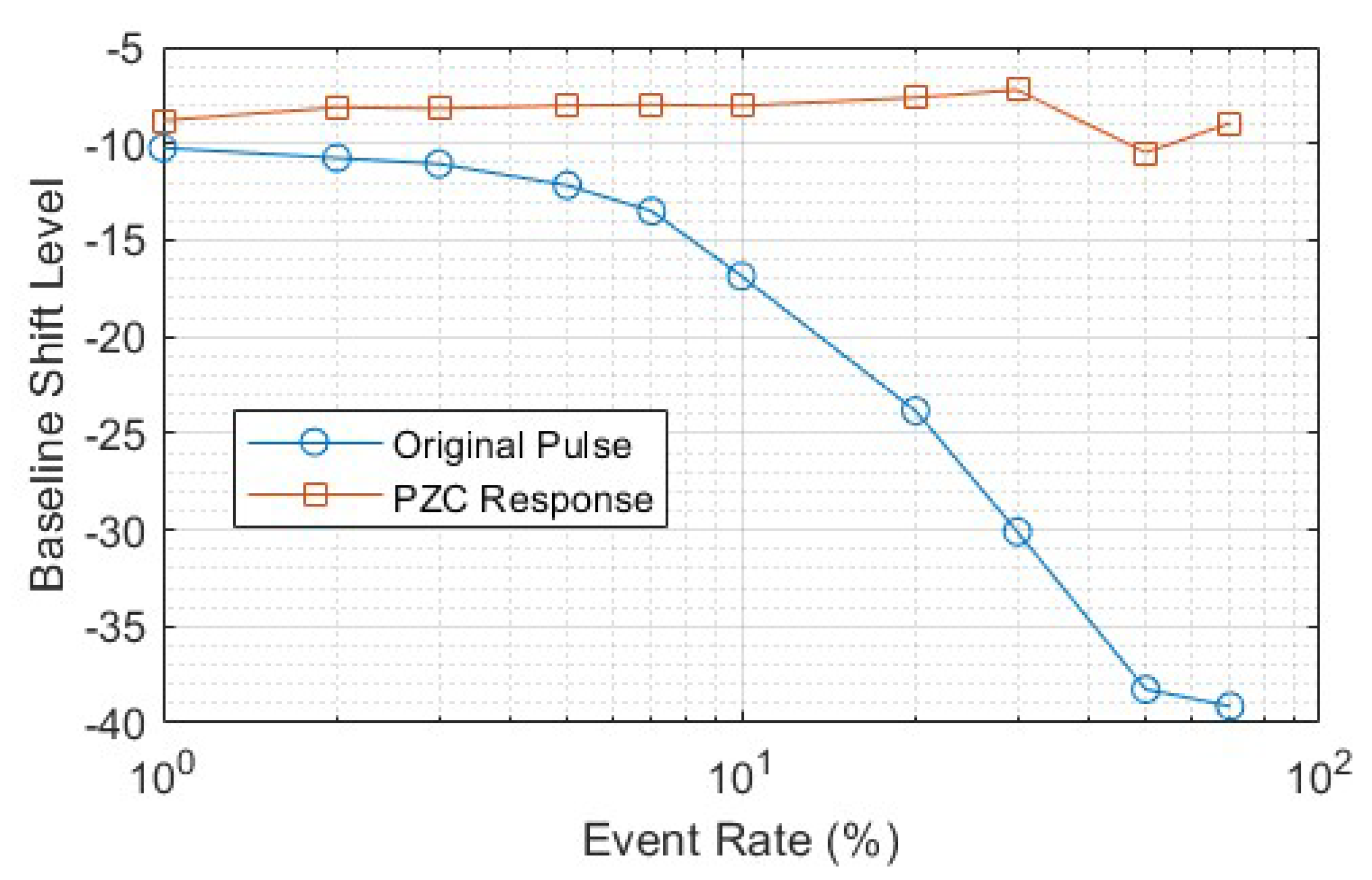

2.2.2. Pole Zero Cancellation

2.3. Hardware Implementation

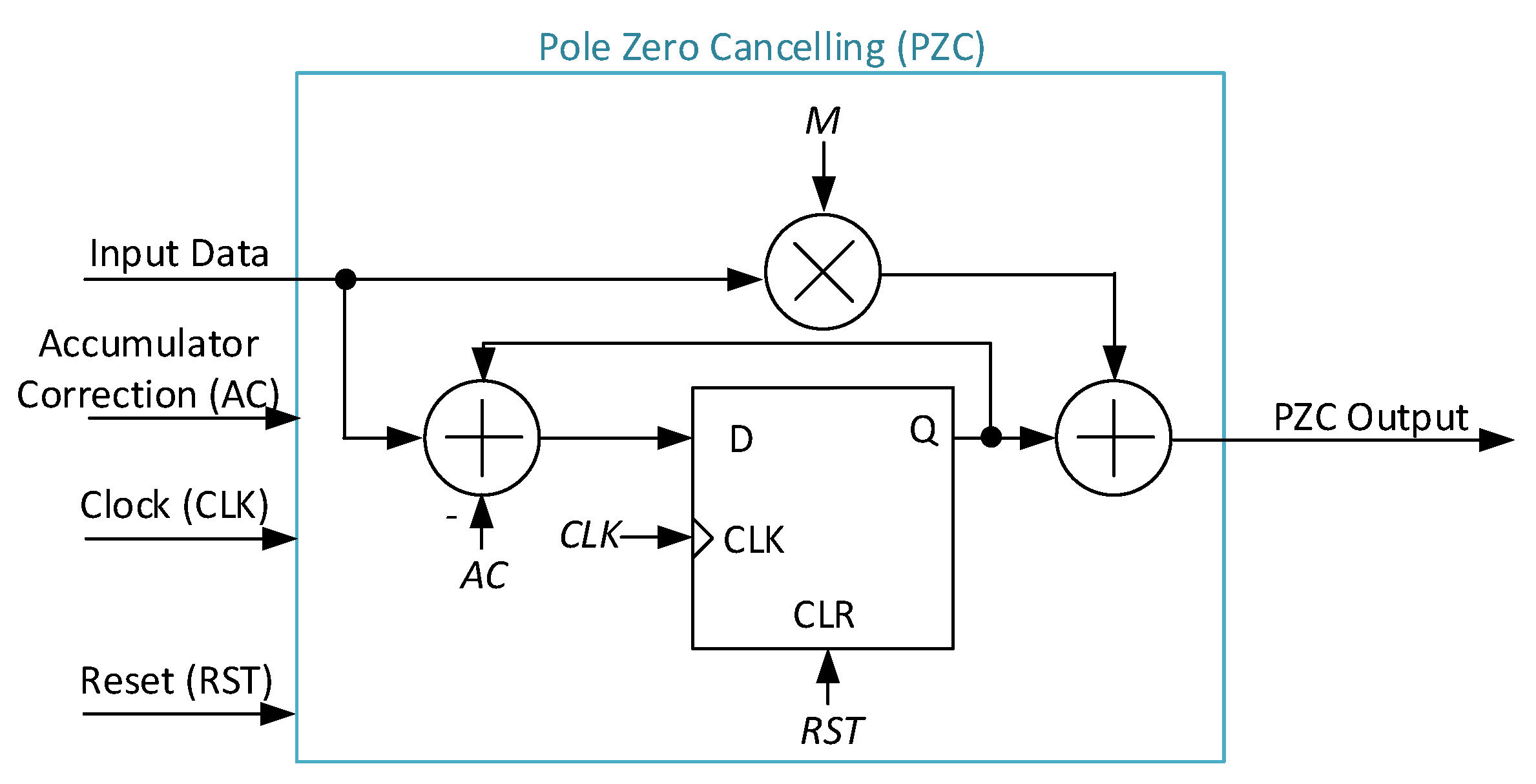

2.3.1. PZC Implementation

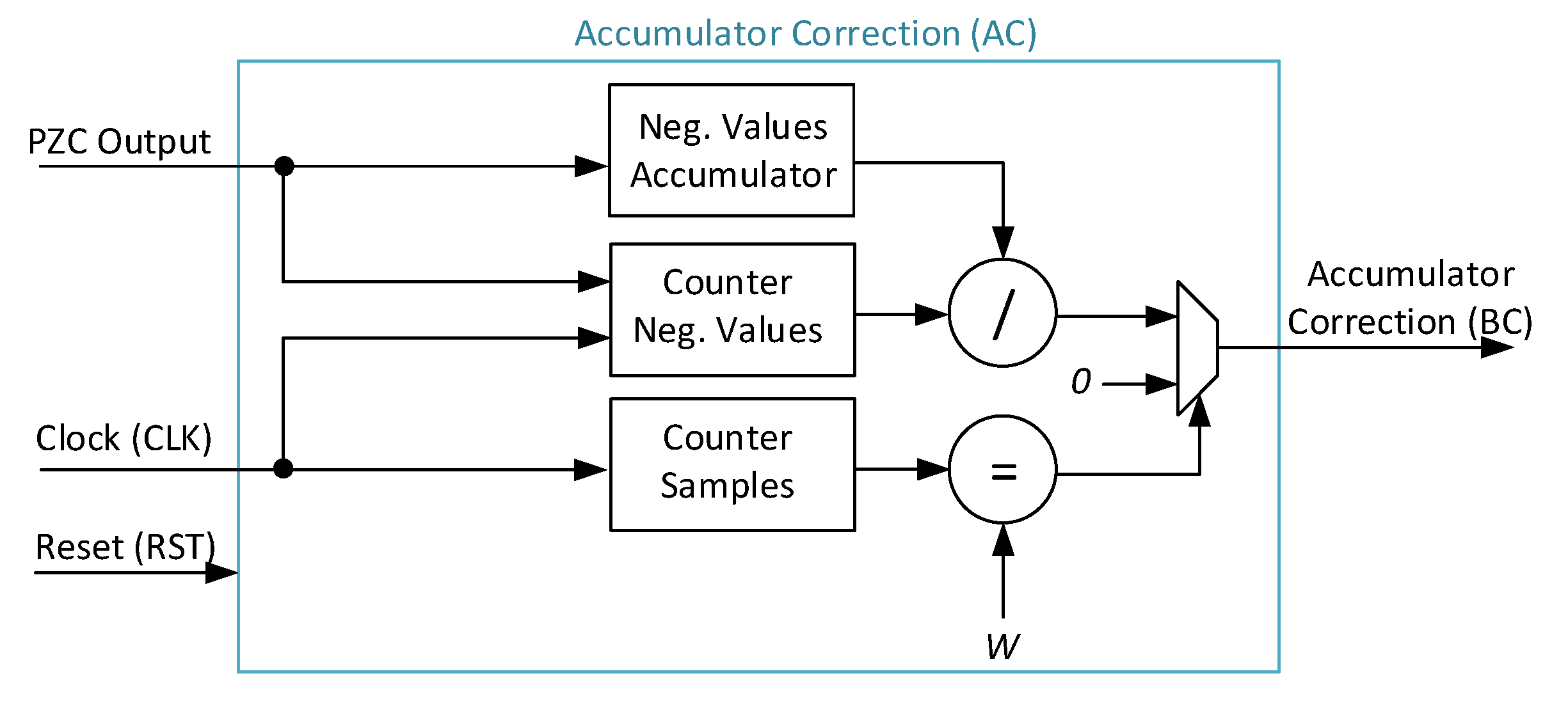

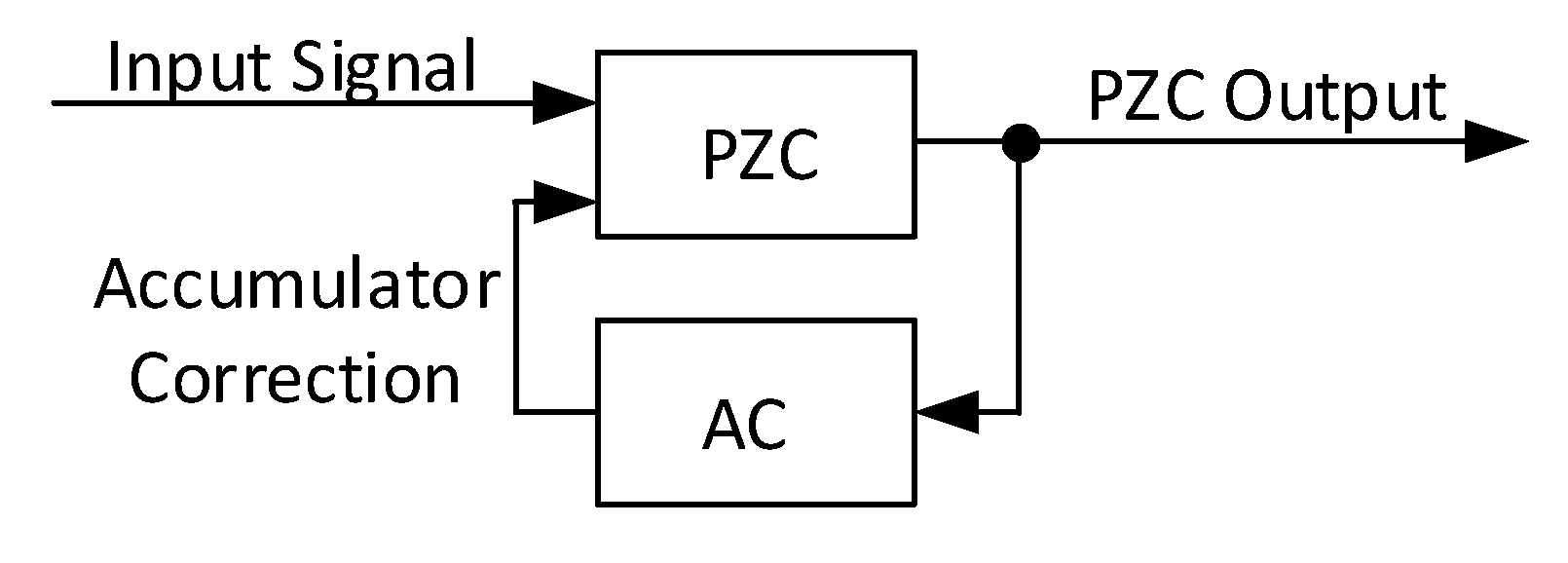

2.3.2. Accumulator Correction (AC)

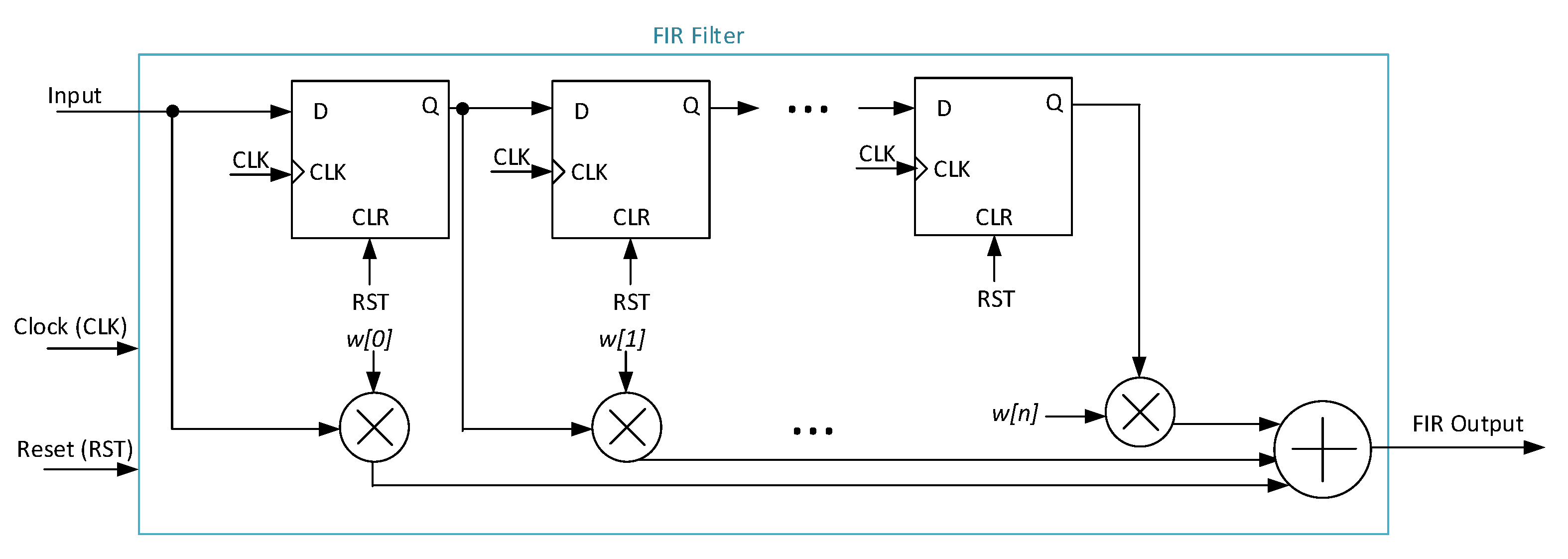

2.3.3. Unfolding Filter

3. Results

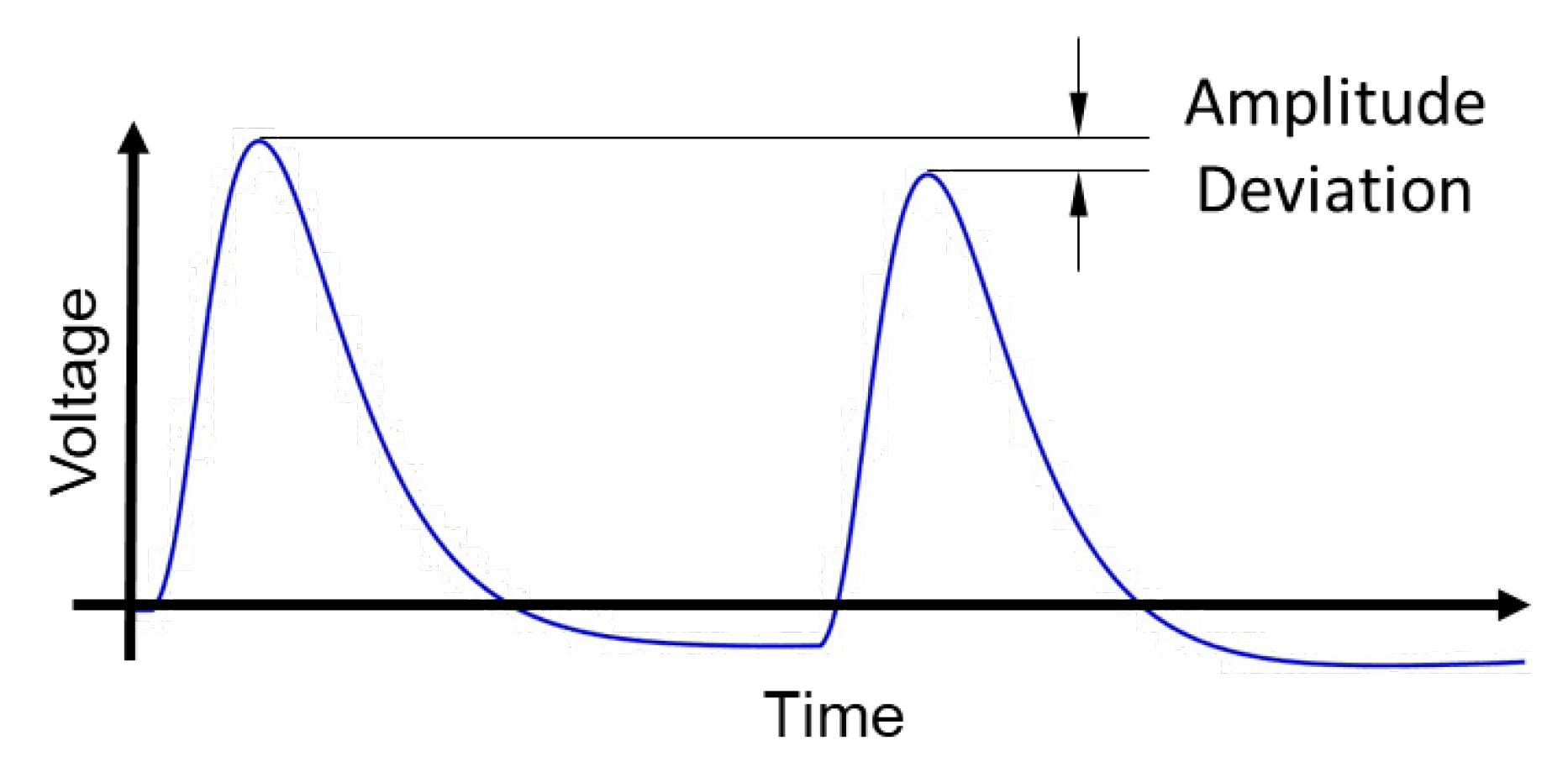

3.1. Readout Waveform

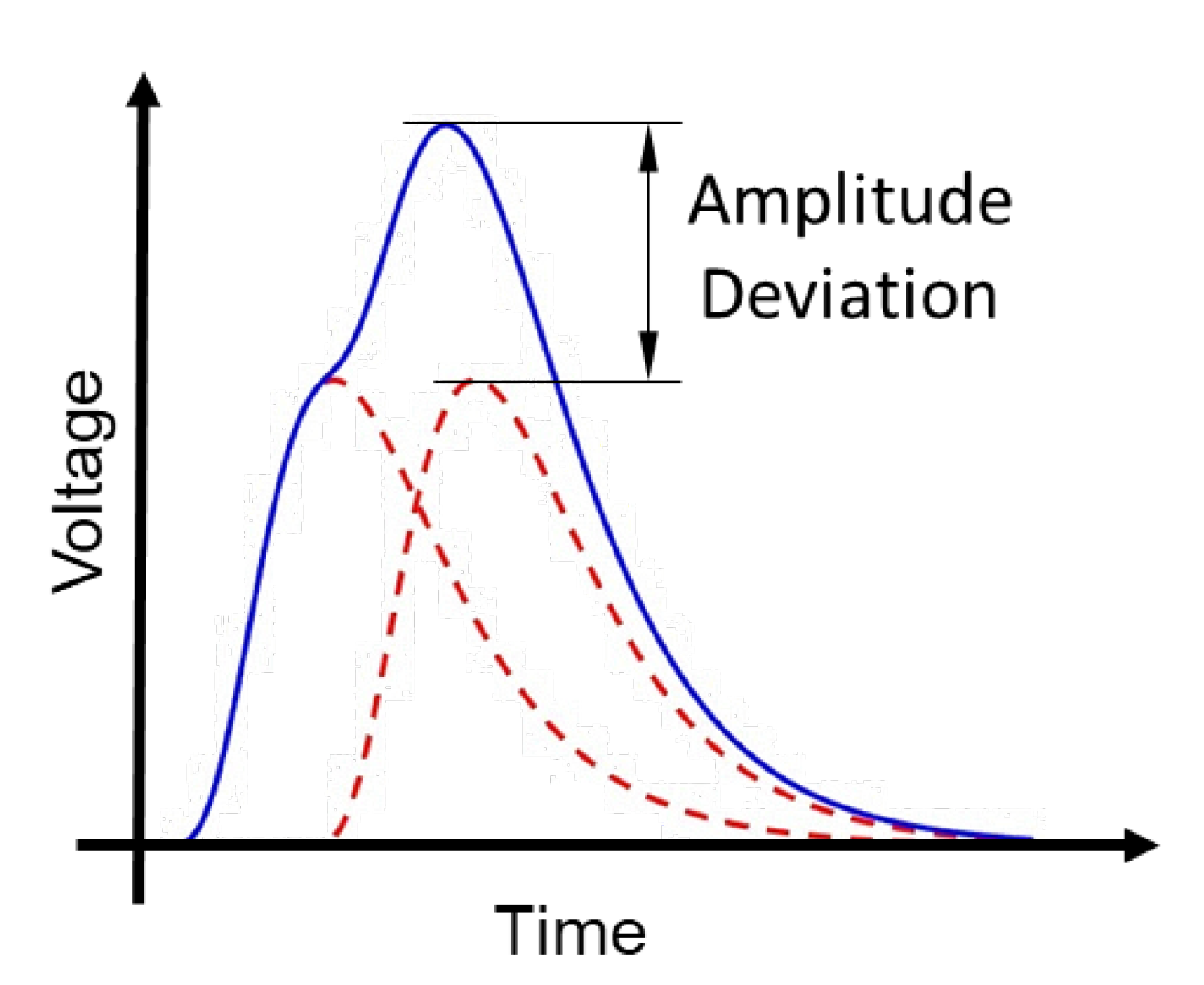

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

3.3. Algorithm Verification in Hardware Implementation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spieler, H. Pulse processing and analysis. IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Short Course; IEEE: San Francisco, 2002; pp. 52–90.

- Conti, M.; Bendriem, B. The new opportunities for high time resolution clinical TOF PET. Clinical and Translational Imaging 2019, 7, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Yi, M.; Lee, J.S. Silicon photomultiplier signal readout and multiplexing techniques for positron emission tomography: a review. Biomedical engineering letters 2022, 12, 263–283. [CrossRef]

- Spieler, H. Semiconductor detector systems; Vol. 12, Oxford university press, 2005.

- Aimaier, N.; Sidek, R.M.; Hamidon, M.N.; Sulaiman, N. Transistor sizing methodology for low noise charge sensitive amplifier with input transistor working in moderate inversion. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Semiconductor Electronics (ICSE2014), 2014, pp. 189–192. [CrossRef]

- Noulis, T.; Fikos, G.; Sarrabayrouse, G.; Siskos, S. Noise analysis of radiation detector charge sensitive amplifier architectures 2008.

- Gallin-Martel, L.; Pouxe, J.; Rossetto, O.; Yamouni, A. A 16 channel analog integrated circuit for PMT pulses processing. IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium; IEEE: San Diego, 2001; pp. 742–745.

- Knoll, G.F. Radiation detection and measurement; John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Beckhoff, B.; Kanngießer, B.; Langhoff, N.; Wedell, R.; Wolff, H. Handbook of practical X-ray fluorescence analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, 2007; pp. 251–255, 260–261.

- Nakhostin, M. Recursive algorithms for real-time digital CR-RCn pulse shaping. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2011, 58, 2378–2381. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.; Flaska, M.; Pozzi, S. Comparison of analog and digital pulse-shape-discrimination systems. Nuc. Instrum. Methods in Phys. Res. A 2016, 826, 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Di Fulvio, A.; Shin, T.; Hamel, M.; Pozzi, S. Digital pulse processing for NaI (Tl) detectors. Nuc. Instrum. Methods in Phys. Res. A 2016, 806, 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, V.T. Deconvolution of pulses from a detector-amplifier configuration. Nuc. Instrum. Methods in Phys. Res. A 1994, 351, 592–594. [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, V.T. Unfolding-synthesis technique for digital pulse processing. Part 1: Unfolding. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2016, 805, 63–71. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.Q.; Yang, J.; Yu, M.F.; Zhang, K.Q.; Ge, Q.; Ge, L.Q. Digital pulse deconvolution method for current tails of NaI (Tl) detectors. Chin. Phys. C 2017, 41, 016102. [CrossRef]

- Födisch, P.; Wohsmann, J.; Lange, B.; Schönherr, J.; Enghardt, W.; Kaever, P. Digital high-pass filter deconvolution by means of an infinite impulse response filter. Nuc. Instrum. Methods in Phys. Res. A 2016, 830, 484–496. [CrossRef]

- Stezelberger, T.; Zimmermann, S. One and Two Poles Compensation of Charge Sensitive Amplifiers with Resistive Feedback to Improve the Energy Resolution in GRETA. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, V.T. Exponential signal synthesis in digital pulse processing. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2012, 670, 18–24. [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca Pinto, J.V.; Marin, J.L.; Freund, W.; Milan, G.G.; de Araújo, M.V.; Gonçalves, G. lorenzetti-hep/lorenzetti: 2.0.0, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Collaboration*, I. Evidence for high-energy extraterrestrial neutrinos at the IceCube detector. Science 2013, 342, 1242856. [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.; Wenaus, T. The ATLAS computing challenge for HL-LHC. Technical report, CERN, 2016.

- Moon, C.S. A level-1 pixel based track trigger for the CMS HL-LHC upgrade. Technical report, CERN, 2016.

- Benedikt, M.; Blondel, A.; Janot, P.; Mangano, M.; Zimmermann, F. Future circular colliders succeeding the LHC. Nature Physics 2020, 16, 402–407. [CrossRef]

- Klochkov, V.; Collaboration, C.; others. The compressed baryonic matter experiment at fair. Nuclear Physics A 2021, 1005, 121945. [CrossRef]

- Smy, M.B. Hyper-Kamiokande. Physical Sciences Forum. MDPI, 2023, Vol. 8, p. 41. [CrossRef]

- Wigmans, R. Calorimetry: Energy measurement in particle physics; Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Bierlich, C.; Chakraborty, S.; Desai, N.; Gellersen, L.; Helenius, I.; Ilten, P.; Lönnblad, L.; Mrenna, S.; Prestel, S.; Preuss, C.T.; Sjöstrand, T.; Skands, P.; Utheim, M.; Verheyen, R. A comprehensive guide to the physics and usage of PYTHIA 8.3. SciPost Phys. Codebases 2022, p. 8. [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; Behner, F.; Bellagamba, L.; Boudreau, J.; Broglia, L.; Brunengo, A.; Burkhardt, H.; Chauvie, S.; Chuma, J.; Chytracek, R.; Cooperman, G.; Cosmo, G.; Degtyarenko, P.; Dell’Acqua, A.; Depaola, G.; Dietrich, D.; Enami, R.; Feliciello, A.; Ferguson, C.; Fesefeldt, H.; Folger, G.; Foppiano, F.; Forti, A.; Garelli, S.; Giani, S.; Giannitrapani, R.; Gibin, D.; Gómez Cadenas, J.; González, I.; Gracia Abril, G.; Greeniaus, G.; Greiner, W.; Grichine, V.; Grossheim, A.; Guatelli, S.; Gumplinger, P.; Hamatsu, R.; Hashimoto, K.; Hasui, H.; Heikkinen, A.; Howard, A.; Ivanchenko, V.; Johnson, A.; Jones, F.; Kallenbach, J.; Kanaya, N.; Kawabata, M.; Kawabata, Y.; Kawaguti, M.; Kelner, S.; Kent, P.; Kimura, A.; Kodama, T.; Kokoulin, R.; Kossov, M.; Kurashige, H.; Lamanna, E.; Lampén, T.; Lara, V.; Lefebure, V.; Lei, F.; Liendl, M.; Lockman, W.; Longo, F.; Magni, S.; Maire, M.; Medernach, E.; Minamimoto, K.; Mora de Freitas, P.; Morita, Y.; Murakami, K.; Nagamatu, M.; Nartallo, R.; Nieminen, P.; Nishimura, T.; Ohtsubo, K.; Okamura, M.; O’Neale, S.; Oohata, Y.; Paech, K.; Perl, J.; Pfeiffer, A.; Pia, M.; Ranjard, F.; Rybin, A.; Sadilov, S.; Di Salvo, E.; Santin, G.; Sasaki, T.; Savvas, N.; Sawada, Y.; Scherer, S.; Sei, S.; Sirotenko, V.; Smith, D.; Starkov, N.; Stoecker, H.; Sulkimo, J.; Takahata, M.; Tanaka, S.; Tcherniaev, E.; Safai Tehrani, E.; Tropeano, M.; Truscott, P.; Uno, H.; Urban, L.; Urban, P.; Verderi, M.; Walkden, A.; Wander, W.; Weber, H.; Wellisch, J.; Wenaus, T.; Williams, D.; Wright, D.; Yamada, T.; Yoshida, H.; Zschiesche, D. Geant4—a simulation toolkit. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2003, 506, 250–303. [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce Dubois, P.; Asai, M.; Barrand, G.; Capra, R.; Chauvie, S.; Chytracek, R.; Cirrone, G.; Cooperman, G.; Cosmo, G.; Cuttone, G.; Daquino, G.; Donszelmann, M.; Dressel, M.; Folger, G.; Foppiano, F.; Generowicz, J.; Grichine, V.; Guatelli, S.; Gumplinger, P.; Heikkinen, A.; Hrivnacova, I.; Howard, A.; Incerti, S.; Ivanchenko, V.; Johnson, T.; Jones, F.; Koi, T.; Kokoulin, R.; Kossov, M.; Kurashige, H.; Lara, V.; Larsson, S.; Lei, F.; Link, O.; Longo, F.; Maire, M.; Mantero, A.; Mascialino, B.; McLaren, I.; Mendez Lorenzo, P.; Minamimoto, K.; Murakami, K.; Nieminen, P.; Pandola, L.; Parlati, S.; Peralta, L.; Perl, J.; Pfeiffer, A.; Pia, M.; Ribon, A.; Rodrigues, P.; Russo, G.; Sadilov, S.; Santin, G.; Sasaki, T.; Smith, D.; Starkov, N.; Tanaka, S.; Tcherniaev, E.; Tome, B.; Trindade, A.; Truscott, P.; Urban, L.; Verderi, M.; Walkden, A.; Wellisch, J.; Williams, D.; Wright, D.; Yoshida, H. Geant4 developments and applications. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2006, 53, 270–278. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.; Begalli, M.; Freund, W.; Gonçalves, G.; Khandoga, M.; Laforge, B.; Leopold, A.; Marin, J.; Peralva, B.M.; Pinto, J.; Santos, M.; Seixas, J.; Simas Filho, E.; Souza, E. Lorenzetti Showers - A general-purpose framework for supporting signal reconstruction and triggering with calorimeters. Computer Physics Communications 2023, 286, 108671. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.; Begalli, M.; Freund, W.; Gonçalves, G.; Khandoga, M.; Laforge, B.; Leopold, A.; Marin, J.; Peralva, B.M.; Pinto, J.; Santos, M.; Seixas, J.; Simas Filho, E.; Souza, E. Lorenzetti Showers - A general-purpose framework for supporting signal reconstruction and triggering with calorimeters. Computer Physics Communications 2023, 286, 108671. [CrossRef]

- Wright, A. The photomultiplier handbook; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2017; p. 553.

- Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Gao, R.; Liu, B.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, Y.; Ruan, J.; Ouyang, X.; Xu, Q. Nanosecond and highly sensitive scintillator based on all-inorganic perovskite single crystals. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 14, 1489–1495. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, R.Y. Fast and Radiation Hard Inorganic Scintillators for Future HEP Experiments. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2022, Vol. 2374, p. 012110. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Gómez, S.; Fernández-Tenllado, J.M.; Ballabriga, R.; Campbell, M.; Gascón, D. Multimodal simulation of large area silicon photomultipliers for time resolution optimization. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2021, 1001, 165247. [CrossRef]

- Garutti, E.; Klanner, R.; Rolph, J.; Schwandt, J. Simulation of the response of SiPMs; Part I: Without saturation effects. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2021, 1019, 165853. [CrossRef]

- Bolic, M.; Drndarevic, V.; Gueaieb, W. Pileup correction algorithms for very-high-count-rate gamma-ray spectrometry with NaI (Tl) detectors. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2009, 59, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- Polushkin, V. Nuclear Electronics: Superconducting Detectors and Processing Techniques; John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Ching-Roa, V.D.; Olson, E.M.; Ibrahim, S.F.; Torres, R.; Giacomelli, M.G. Ultrahigh-speed point scanning two-photon microscopy using high dynamic range silicon photomultipliers. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 5248. [CrossRef]

- Gatti, E.; Geraci, A.; Ripamonti, G. Optimum time-limited filters for input signals of arbitrary shape. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 1997, 395, 226–230. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J. Fast split bregman based deconvolution algorithm for airborne radar imaging. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1747. [CrossRef]

- Grybos, P.; Maj, P.; Ramello, L.; Swientek, K. Measurements of matching and high count rate performance of multichannel ASIC for digital X-ray imaging systems. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2007, 54, 1207–1215. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, W.; Tang, Z.; Yan, J.; Lv, M.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, X. Interference correction for laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy using a deconvolution algorithm. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 2020, 35, 762–766. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.C.; Syrzycki, M. Current source transistor optimization methodology for noise optimized charge sensitive amplifier with fast shaper. 2011 24th Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE). IEEE, 2011, pp. 000735–000738.

- Zhang, H.Q.; Qian, Y.c.; Chen, H.; Shi, H.t. Design and characterization of third-order Sallen–Key digital filter in nuclear signal processing. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2022, 186, 110277. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lai, W.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, J. Design of Experimental Circuit Board of Spectrometer Amplifier in Nuclear Electronics. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2023, Vol. 2440, p. 012008. [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, V.T.; Knoll, G.F.; Huber, A.C.; Pantazis, J.A. Digital techniques for real-time pulse shaping in radiation measurements. Nuc. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1994, 353, 261–264. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wan, W.; Zhou, J.; Hong, X.; Liu, F.; Yu, J. Counting-loss correction method based on dual-exponential impulse shaping. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 2020, 27, 1609–1613. [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Baese, U.; Meyer-Baese, U. Digital signal processing with field programmable gate arrays; Vol. 65, Springer, 2007.

- Du, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H. Convolutional sparse learning for blind deconvolution and application on impulsive feature detection. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2018, 67, 338–349. [CrossRef]

- Khilkevitch, E.; Shevelev, A.; Chugunov, I.; Iliasova, M.; Doinikov, D.; Gin, D.; Naidenov, V.; Polunovsky, I. Advanced algorithms for signal processing scintillation gamma ray detectors at high counting rates. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2020, 977, 164309. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).