1. Introduction

Women’s participation in leadership positions remains uneven across industries and countries, despite notable gains in educational attainment and workforce presence. Research has increasingly focused on psychological and organizational factors that influence leadership emergence and performance—particularly the role of self-efficacy, leader-member exchange (LMX), and organizational behavior.

Self-efficacy, defined as the belief in one’s capability to succeed in specific tasks, is a crucial trait for effective leadership. Leaders with high self-efficacy are more resilient, take initiative, and foster innovation. The LMX theory complements this by emphasizing the quality of interpersonal relationships between leaders and subordinates as a determinant of performance, motivation, and engagement. Together, these constructs shape organizational behavior by influencing how leaders and employees interact, adapt, and perform within complex systems.

This study investigates the relationship between female leadership representation and theoretical constructs such as self-efficacy and LMX. Using longitudinal data from Eurostat and the World Bank (2019–2023) across four Eastern European countries—Romania, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria—we assess how macro-level indicators reflect the presence or erosion of self-efficacy in female leadership. We also explore structural constraints, such as part-time employment and childcare responsibilities, that may affect women’s organizational advancement and behavior.

2. Literature review

The relationship between a leader's self-efficacy, innovative work behavior, goal striving/ commitment/generation, and trait resilience results in agile management with multifaceted, with each element influencing and reinforcing the others.

2.1. Leadership and Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments. In leadership contexts, it influences how challenges are approached, how teams are motivated, and how performance is sustained under pressure. Leaders with high self-efficacy tend to set challenging goals, persist in the face of setbacks, and demonstrate confidence in decision-making (Bandura, 1997; Asghar et al., 2022). Strong self-efficacy leads to improved work effectiveness, especially in high-quality Leadership Models (LMX). Innovative behavior, especially in complex situations, is boosted by high self-efficacy, which is mediated by LMX. Research suggests self-efficacy mediates the relationship between employee-dependent characteristics and leadership variables (Nilawati, 2021; Sohn, 2020).

In female leadership, self-efficacy plays a dual role: it fosters personal resilience against structural gender barriers and promotes inclusive and motivational leadership practices. Self-efficacy also correlates positively with innovative work behavior and leadership emergence, especially when supported by strong organizational structures and feedback mechanisms (Sohn, 2020; Bracht et al., 2021).

2.2. Leader-Member Exchange (LMX)

LMX theory posits that leaders develop differentiated relationships with their followers, which can affect job satisfaction, innovation, and organizational citizenship behavior. High-quality LMX is built on mutual respect, trust, and professional support and can enhance employee creativity and engagement (Walumbwa et al., 2011; McLarty et al., 2021).

Within gender-diverse teams, female leaders often cultivate high-quality LMX through transformational and empathetic styles, which have been shown to foster stronger team dynamics and improve organizational performance. This dynamic can serve as a buffer against structural biases in traditionally male-dominated environments (Liu et al., 2021).

2.3. Organizational Behavior and Innovation Culture

Organizational behavior reflects how individuals interact within an organization, encompassing motivation, voice behavior, and performance. Workplace performance requires innovative behavior, requiring high self-efficacy, which encourages patience and hard work. Proactive mentality helps secure psychological resources and influence the environment, inspiring creativity and individual inventiveness. Leader humility helps navigate social situations better, fostering positive interactions and group regulation. Creativity can be both original and fruitful, and various leadership philosophies can foster innovation. However, the positive impact of creativity may be limited by organizational size, realized absorptive capacity, and riskiness orientation. Social cues of leaders can influence followers' creativity drive (Asghar, 2022). A supportive organizational culture that values diversity, fairness, and innovation is essential for maximizing leadership potential, particularly for women.

The literature suggests that a company's innovation strategy is largely determined by its organizational culture, with hierarchical cultures linked to copying and adhocracy societies encouraging creativity. Managers should focus on the culture of their firm when pursuing innovation/imitation tactics, fostering distinct norms and values within their organizations. Adopting an innovation strategy should foster adhocracy values, commitment to innovation, and a dynamic entrepreneurial environment (Naranjo-Valencia, 2011, Scaliza, 2022).

Literature explores the connection between 360-degree feedback appraisals, creativity, and organizational fairness. A poll of 200 participants from different nations showed a positive correlation between innovation, creativity, and the use of 360-degree feedback ratings. Employees' sense of fairness was also found to be positively correlated with the use of such feedback (Souki, 2024).

Transformational leaders support creative processes by giving people the tools and encouragement they need to think creatively and solve problems. They can successfully support creative ideas and efforts, fostering innovation, by having faith in their own and their team's talents (Hansen, 2019).

Innovation and agile cultures—characterized by decentralized decision-making and openness to change—are more likely to benefit from women’s leadership traits such as collaboration and emotional intelligence (Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2011; Hansen, 2019). Furthermore, organizational justice and feedback systems such as 360-degree reviews have been linked to higher perceived fairness and creativity among employees (Souki, 2024).

Agile management, originating in the software development industry, is a flexible, team-oriented approach that promotes adaptability, rapid iterations, and collaboration (Bucea-Manea-Țoniş, 2021). High self-efficacy leaders are more likely to apply agile concepts due to their faith in handling complexities and uncertainties (Cojocaru, 2022).Agile leaders should develop comprehensive assessment systems, empower employees, and improve performance reviews to create an environment that encourages creativity and equitable treatment (Sürücü, 2022, Kim, 2022; Sawitri, 2021, Souki, 2024, Icekson, 2024, Mustafa, 2023). Emotional intelligence, compassion, decision-making, and motivation are crucial components of effective leadership. Integrating neuroscience into leadership training can lead to more resilient and productive teams (Song, 2020; Gu, 2020, Edison, 2019; Le, 2019, Li, 2020, Hansen, 2019).

In this study, self-efficacy is operationalized at a macro-structural level using the percentage of women in top managerial roles and ministerial positions. This is based on the assumption that greater female representation reflects both societal confidence in female leadership and women’s internalized belief in their own leadership capacity, consistent with Bandura’s theory that self-efficacy is shaped by mastery experiences and social modeling.

While direct LMX measures (e.g., survey data on team trust or support) are unavailable, we use the employment gap related to number of children and part-time employment rates as structural proxies. These reflect systemic barriers to forming high-quality leader-member relationships, such as inflexible work conditions and care-related career interruptions.

Organizational behavior is inferred from trends in women’s overall management presence and cross-country variance in managerial representation. These outcomes reflect organizational openness to diversity, internal mobility, and fairness in promotion practices.

3. Methodology

This study employs longitudinal quantitative data from Eurostat and World Bank datasets with a literature-based conceptual analysis. The primary aim is to assess cross-national trends and potential disparities in women’s representation in leadership positions across four Eastern European countries—Romania, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria—between 2019 and 2023. (EU1 -EU6, 2024).

We use two indicators as proxies for societal-level self-efficacy among women: (1) share of women in senior/middle management, and (2) share of women in ministerial positions. Declines in these indicators over time may suggest a decrease in perceived or structural self-efficacy.

Variability in part-time work by gender and employment drops for women with children are interpreted as constraints on forming equitable, trust-based leader-member relationships, central to the LMX model.

Percentage of women in management and the gap between educational attainment and leadership representation are used to assess organizational behavior inclusivity and meritocracy.

Thus, this study applies a proxy-based approach to operationalize self-efficacy, LMX, and organizational behavior at the national level, given the use of institutional datasets. Self-efficacy is proxied by leadership representation indicators. LMX is indirectly assessed through structural employment constraints such as part-time work and motherhood-related employment gaps. Organizational behavior is captured by the alignment (or mismatch) between women’s educational attainment and actual leadership roles. While these are indirect, they reflect the structural conditions that enable or inhibit the psychological and relational constructs discussed in the theoretical framework.

The data were structured in panel format, with country-year-indicator units of analysis. Observations were drawn from official Eurostat and World Bank sources, harmonized to ensure consistency in measurement definitions across countries and time. Where exact values for a specific year were unavailable, a forward-fill method was used to maintain time continuity without imputing new values. Indicators were selected based on availability across all countries and their theoretical alignment with the constructs of self-efficacy, LMX, and organizational behavior. Regression analysis was conducted using OLS, with dummy variables for country and indicator effects and a centered year variable to assess time trends.

In the study carried out, hypotheses H1, H2 and H3 can be related to the three ideas stated above in the following way:

Hypothesis H1: Despite increases in women’s tertiary education attainment, the representation of women in senior and executive leadership positions has not proportionally increased between 2019 and 2023 in Romania, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria.

Link to aspect 1- Leaders with self-efficacy have a positive impact on organizational behavior. If the female leadership indices (self-leadership women) have decreased in the last 4-5 years, this may indicate a reduction in the self-confidence (self-efficacy) of female leaders, which could have a negative impact on the behavior organization.

Link with aspect 2 - LMX has a positive impact on organizational behavior. If the indices of female leadership (self-leadership women) decreased, this may indicate a reduction in the quality of the relationship between the leader and his team members (LMX), which could have a negative impact on organizational behavior.

Link to aspect 3 - Organizational behavior has a positive impact on organizational performance. If the female leadership indices (self-leadership women) decreased, this may indicate a reduction in organizational performance, which could be caused by negative organizational behavior.

Hypothesis H2: There are no statistically significant differences across the four countries in the share of women in leadership roles, suggesting that regional socio-cultural factors may influence gender parity uniformly.

Link to aspect 1 - Leaders with self-efficacy have a positive impact on organizational behavior. If there are no significant differences between countries regarding women as managers, this may indicate that leaders with self-efficacy are equally present in all countries, which could have a positive impact on organizational behavior.

Link to aspect 2 - LMX has a positive impact on organizational behavior. If there are no significant differences between countries regarding women as managers, this may indicate that the quality of the relationship between the leader and his team members (LMX) is equal in all countries, which could have a positive impact on organizational behavior.

Link to aspect 3 - Organizational behavior has a positive impact on organizational performance. If there are no significant differences between countries regarding women as managers, this may indicate that the performance of organizations is equal in all countries, which could be caused by positive organizational behavior.

Hypothesis H3: The gender employment gap widens with the number of children, indicating persistent structural constraints affecting women’s organizational mobility and leadership emergence.

Statistical analysis included: One-way ANOVA with Welch’s correction was implemented to test cross-national differences in leadership representation. Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests were chosen to assess normality and homogeneity of variances. Missing data and potential outliers were identified and addressed using listwise deletion and sensitivity checks.

4. Results

4.1. Presentation of Data Sources

a.

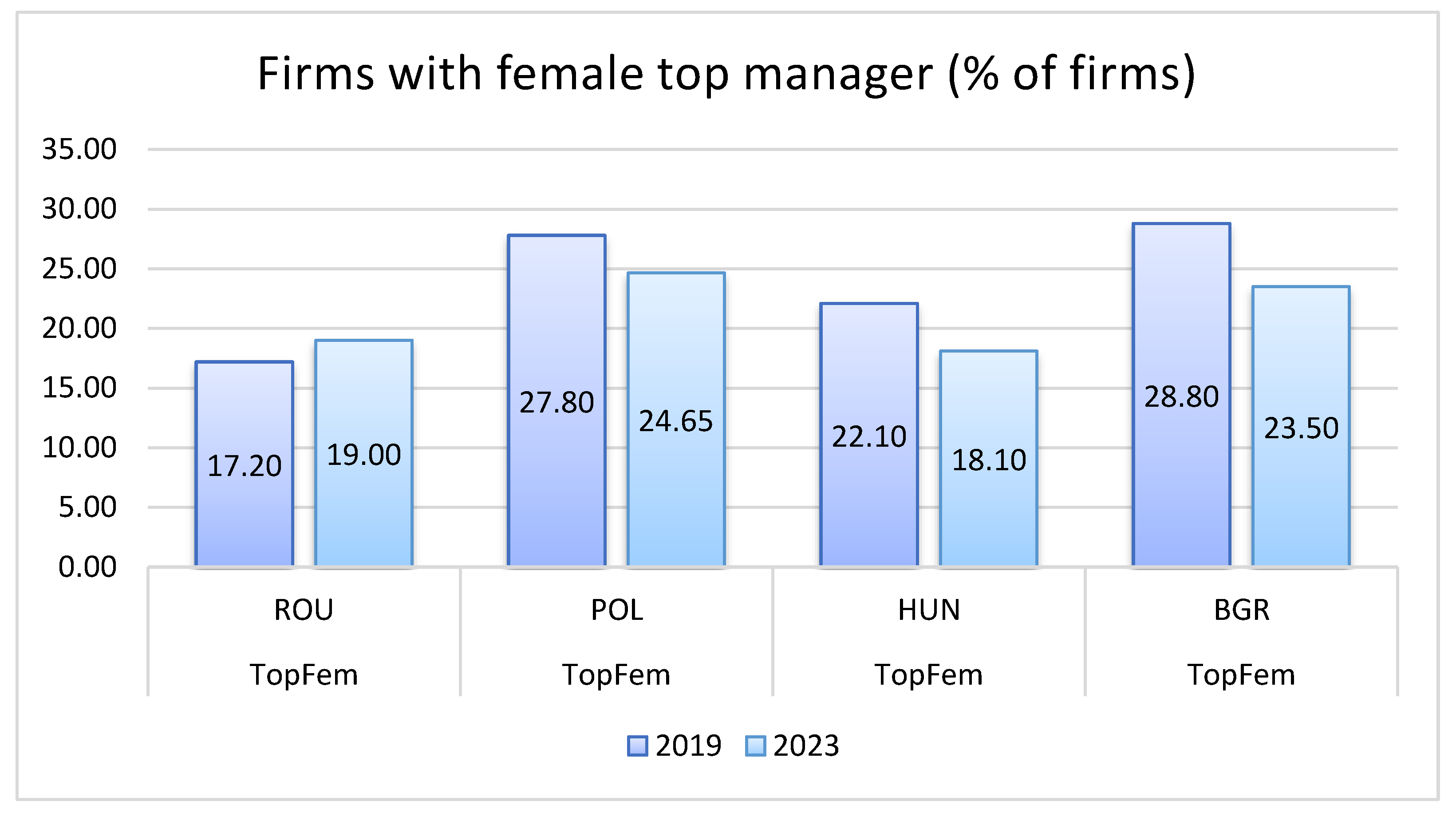

Firms with Female Top Managers Figure 1 supports Hypothesis H1 by illustrating trends in women's leadership roles in the private sector. The data show a decline in the percentage of firms led by women from 2019 to 2023 in most countries, except Romania. This decline, particularly in Hungary and Bulgaria, may reflect structural limits on self-efficacy and suggest a broader pattern of underrepresentation at the top management level.

If we look at the population by level of education, gender, and age (%), according to EUROSTAT data, a higher proportion of women than men have a high level of education. Thus, in tertiary education, the share of women with tertiary education was higher than the corresponding share of men, i.e. 36.2% of women in the EU graduated from this level, compared to 31.0% of men, in 2021 (EU1, 2024). The same higher proportions of women than men with a high level of education are maintained in the case of the 4 countries analyzed. Poland ranks first, with the highest percentages of women with a high level of education (44.6%) compared to men (31.3%) in 2023, followed by Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania (EU2, 2024).

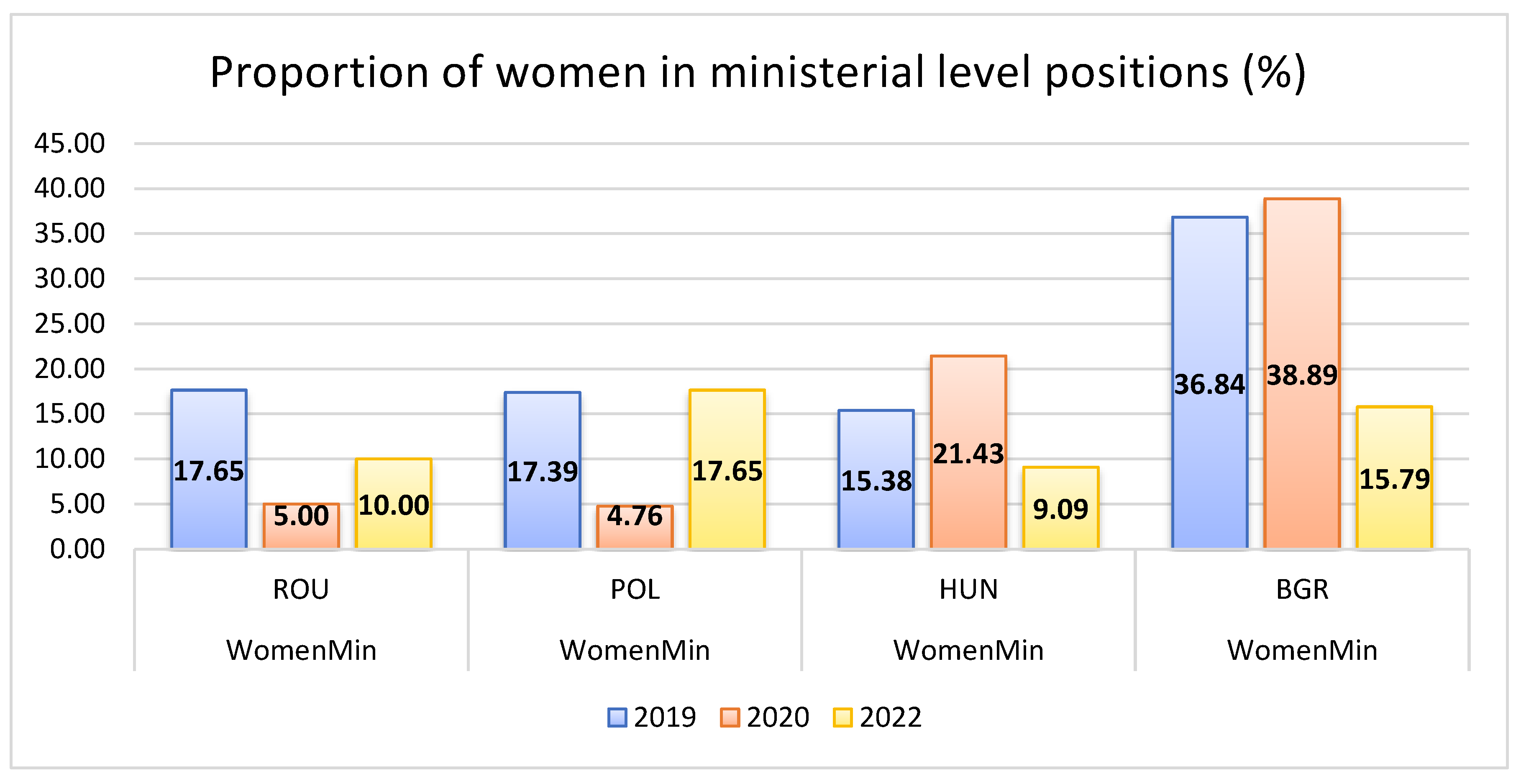

b. Women in Ministerial Roles: One may observe that this proportion decreased in all countries in the last 4-5 years. The highest gap was encountered in Bulgaria, where this index decreased from 38.89 to 15.78, more than a half. We may observe a small increase in Poland from 17.39 in 2019 to 17.65 in 2022, after a very high fluctuation in 2020. Hungary had a positive fluctuation reaching 21.43%. Overall, the percentage of women in ministerial positions is very low, less than 20. Men seem to inspire more confidence and women might be discriminated against or uninterested in this function. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2 reinforces Hypothesis H1 that executive roles—like ministerial positions—are the most resistant to gender parity. The significant drop in Bulgaria from 38.89% to 15.78% exemplifies the structural volatility and stagnation in female political leadership.

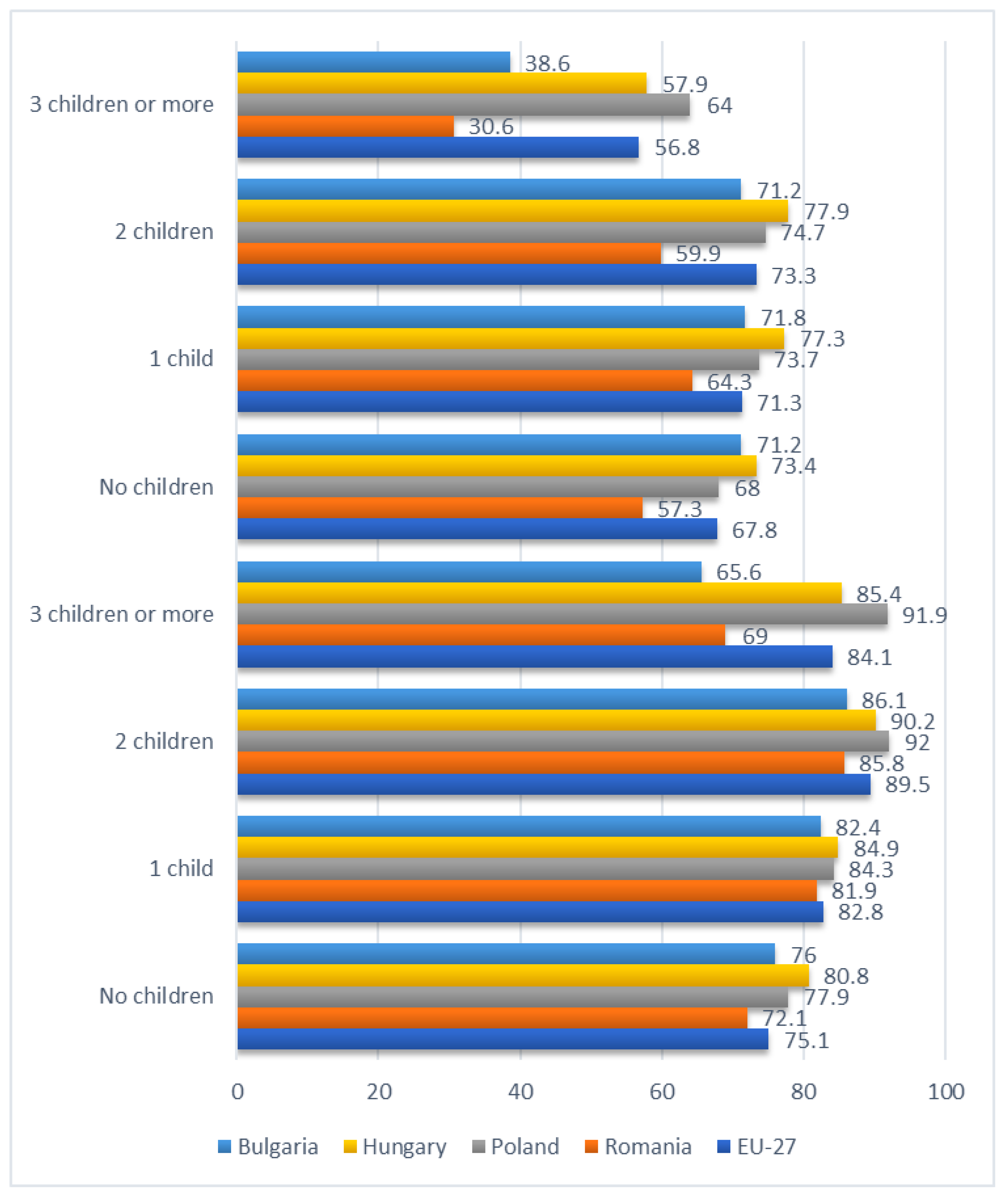

c. Gender Employment Gap by Number of Children: The more children, the greater the employment gap between women and men (employment patterns) 2023 - On average, in the EU, the employment rate of people aged 18-64 was higher for men (78.7%) than for women (68.7%) in 2023. However, the difference between the employment rate of men and women increases with the number of children. Indeed, the employment rate for childless men was 75.1%, while for childless women it was 67.8%, resulting in a difference of 7.3 pp. For people with one child, the difference between the employment rate of men (82.8%) and women (71.3%) amounts to 11.5 pp. For people with two children, the gender employment gap increased to 16.2 pp. (89.5% for men vs. 73.3% for women), while for people with three or more children, the difference reached 27.3 pp., with a male employment rate of 84.1 % and a female employment rate of only 56.8%. This trend is observed in the vast majority of Member States. For Romania, the employment gap between the sexes remains at a level of 18.6 pp, and in the number of children, the largest difference is 38.4 pp for people with three or more children. Poland and Hungary are above the EU average in terms of employment rate on all elements analyzed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 directly addresses Hypothesis H3. It visualizes the employment gap widening with the number of children, especially in Romania. This supports the interpretation that motherhood-related constraints affect women’s organizational mobility and hinder their progression into leadership roles—thus also indirectly impacting LMX dynamics.

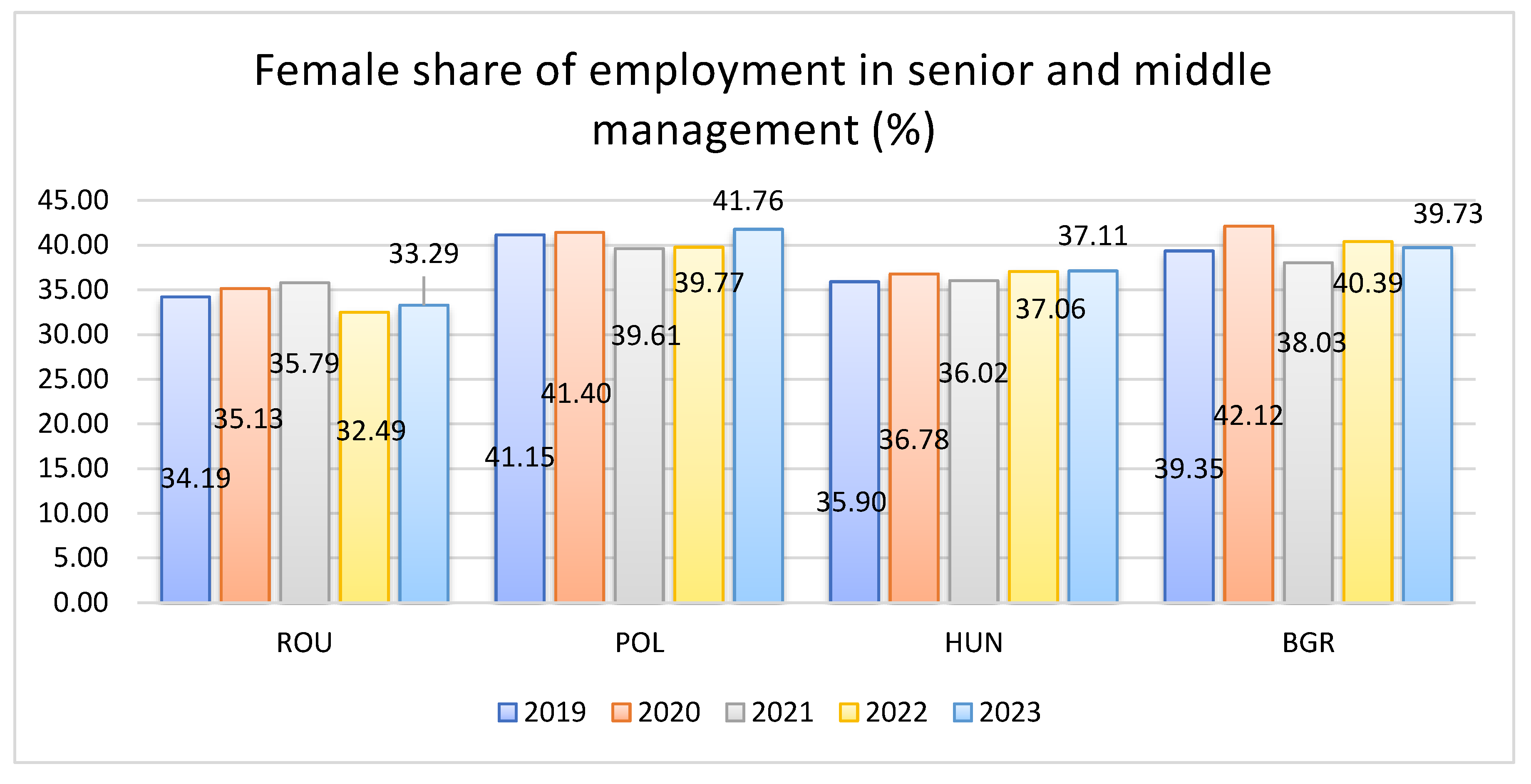

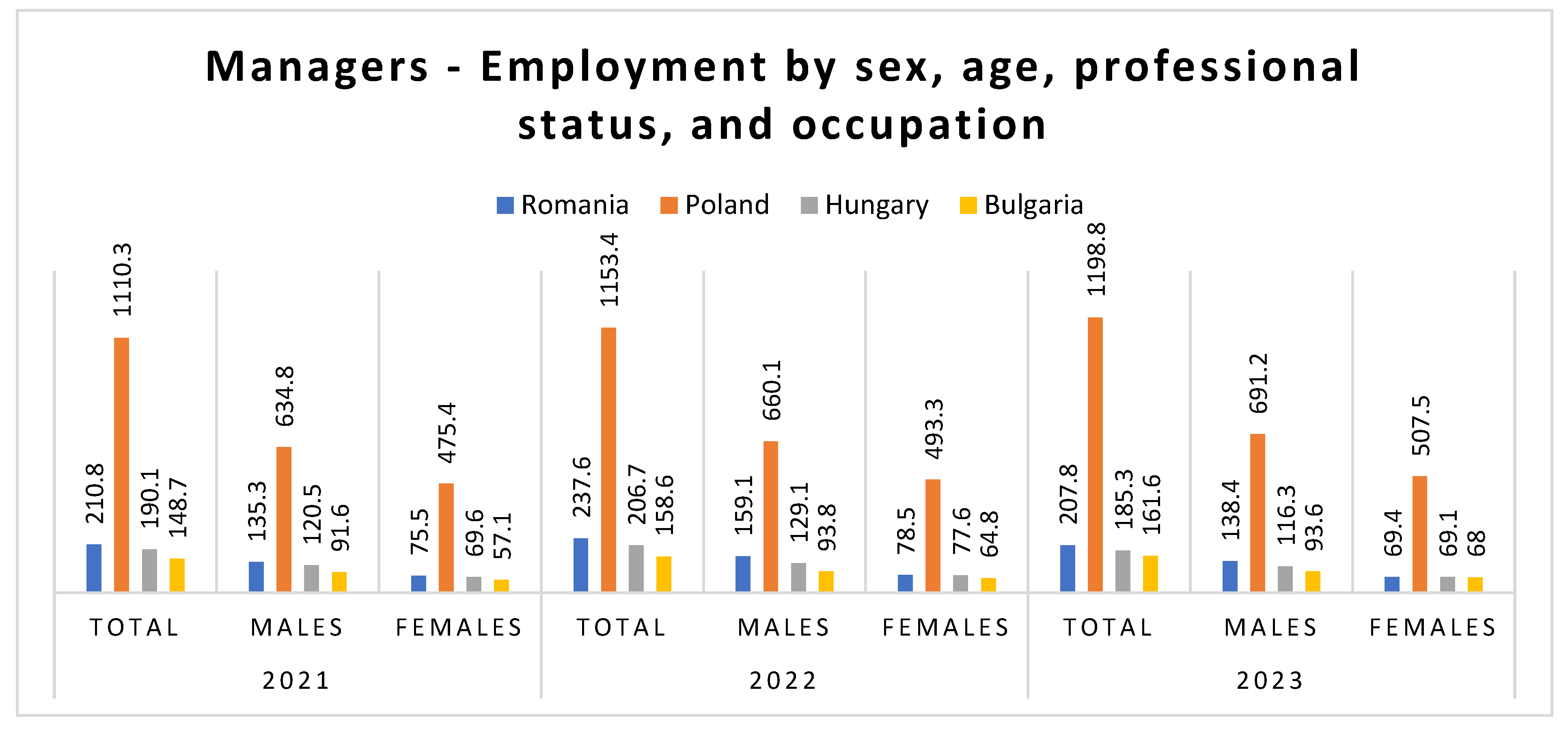

d. Women in Senior and Middle Management: The percentage of women working in middle and senior management overall. Since these primarily consist of managers of small businesses, it equates to major group 1 in both ISCO-08 and ISCO-88 minus category 14 in ISCO-08 (managers of hotel, retail, and other services) and minus category 13 in ISCO-88 (general managers).

The percentage of women employed in senior and middle management is rather high, almost 40% in Poland and Bulgaria in the period 2019-2023. They are preferred due to their higher emotional intelligence and ability to meet objectives. In third place is Hungary, with a smaller percentage, almost 37% and Romania is the last with a small percentage, almost 34%. Men still lead in the middle and senior management overall (Fig.4).

e.

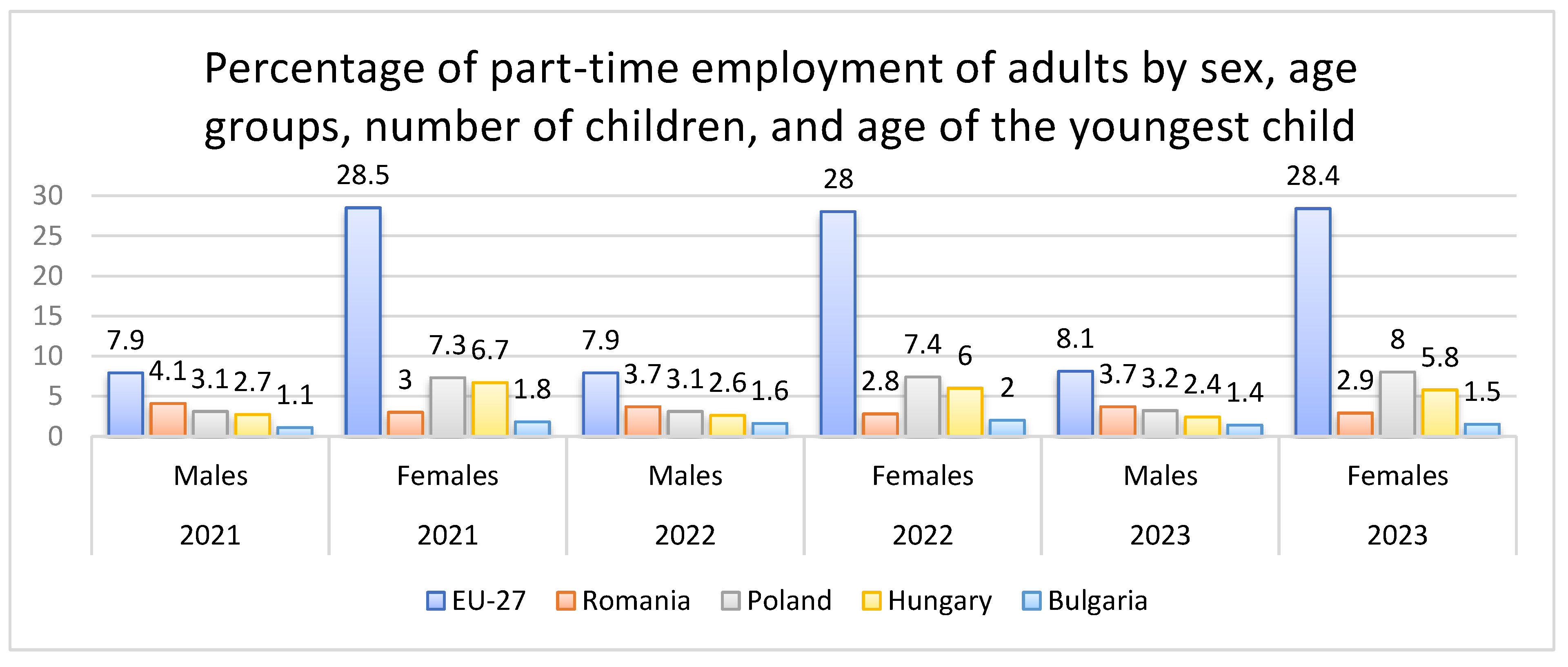

Part-Time Employment by Gender: Figure 5 emphasize that LMX-related aspects of Hypotheses H1 and H3, Fig. 5 shows structural employment constraints that limit women's access to leadership. In particular, the disproportionately higher rates of part-time work among women in Poland reflect underlying labor market segregation.

More than a quarter of employed women work part-time - An important aspect of work-life balance is part-time work. However, it is not equally distributed between women and men: in the EU, in 2023, 28.4% of employed women worked part-time, compared to 8.1% of men. This results in an important difference of 20.3 pp. Compared to the EU average, the countries analyzed have among the lowest percentages of part-time employees. The lowest proportion of women and men working part-time is observed in Bulgaria (1.5 % for women and 1.4 % for men). In Poland, there is a larger difference in percentage points between women (8.0%) and men (3.2%), namely 4.8 pp (Fig.5).

Other causes can be associated with important moments in life for women/men such as: starting primary education, first job, leaving the parental home, birth of the first child, first marriage, life expectancy. Both the EU average and the situation of the countries analyzed indicate that women leave the parental home and marry earlier than men (EU5, 2024). Analyses of these important life milestones show, for example, that on average in the EU in 2021, women left their parental home almost two years earlier than men (at the age of 25.6 years for women and 27.5 years for men). Women also married earlier in all Member States, with an age difference at first marriage of 3 years and more in Romania, and Bulgaria. In terms of children, in 2020, women in the EU were almost 30 years old when they gave birth to their first child, ranging in age from around 26 years old in Bulgaria to 28.4 years old in Hungary. In 2021, women lived longer than men in 2021. The EU average was 82.9 years for women and 77.2 years for men, a difference of 5.6 years. Among the countries analyzed, the lowest life expectancy for both women and men are in Bulgaria, and the highest in Poland.

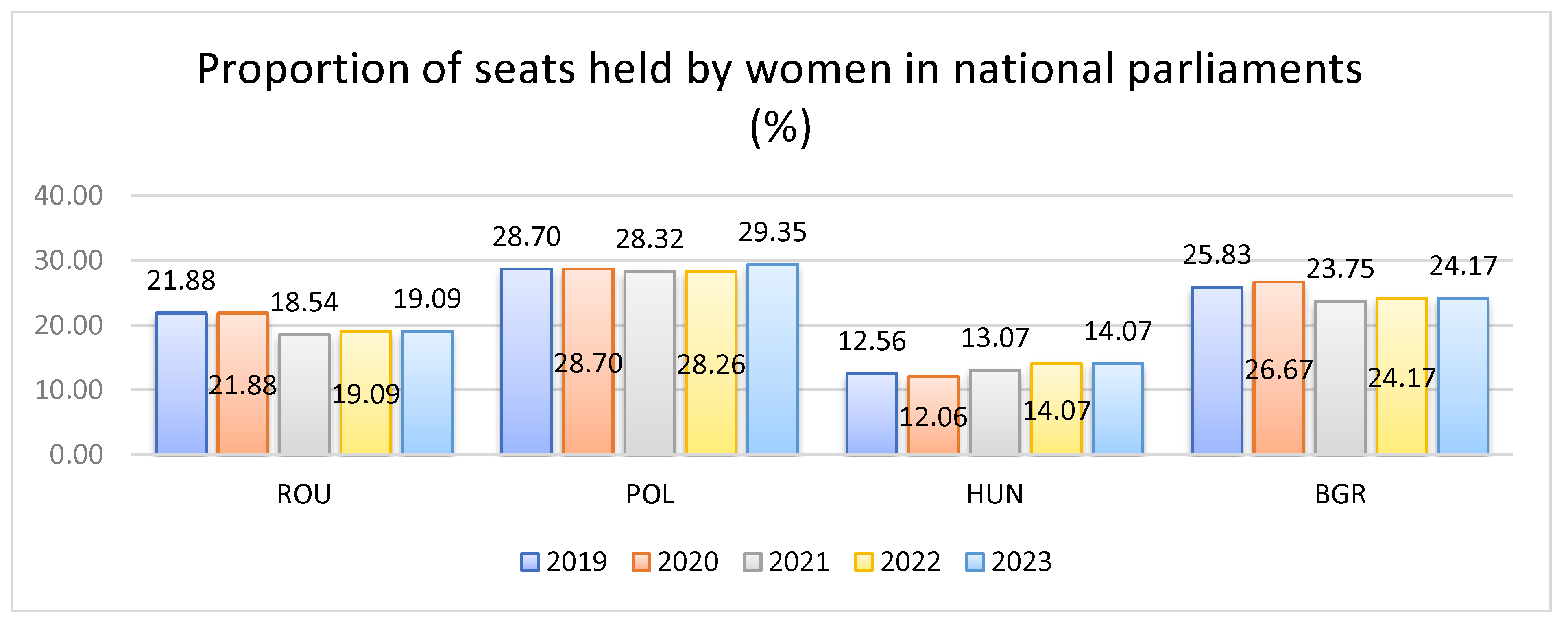

f. Women in National Parliaments: This indicator’s relatively stronger performance (particularly in Poland) provides a contrasting case that highlights the sectoral differences in gender openness.

The percentage of women in parliaments was rather constant in the period 2019 to 2023. Polonia leads this ranking with almost 30%. It is followed by Bulgaria with almost 24%, Romania with almost 20%, and Hungary with almost 13% (Fig. 6). Overall, the percentage of women in parliaments is still very low in comparison with men.

g. Overall Managerial Representation: About a third of managers in the EU are women. It can be seen that women accounted for just over a third (35%) of managers in the EU in 2021, 2022, and 34.8% in 2023. The share of women in this position did not exceed 50% in any of the EU Member States. And among the 4 countries analyzed, the highest proportions were observed in Poland (42.8%) in 2021 and 42.3% in 2023, respectively. On the other hand, among the 4 countries, the lowest percentages were recorded in Romania, where women managers represent only 33.3% of the total managers in 2023, 37.2% in Hungary, and Bulgaria with 42% (Fig. 7).

In conclusion, there are structural differences between women's and men's lives in Europe, influencing women's working lives and their access to managerial positions in EU firms and in the four countries analyzed.

4.2. OLS Regression

In the second step of our research, we designed a model that tests how country, indicator type, and time (2019–2023) affect the value of gender equality indicators. The model took the base reference: Bulgaria for country and Ministerial Positions for indicator.

The OLS regression model explains a substantial portion of the variance in gender leadership indicators across the four countries and five years studied. The model’s R² of 0.59 indicates that 59% of the variation in leadership scores can be attributed to the selected predictors—country, indicator type, and time trend (

Table 1).

The Country Effects having as reference Bulgaria: Hungary shows a significant negative coefficient (–6.53,

p < 0.001), meaning that on average, Hungary scores 6.53 percentage points lower than Bulgaria across leadership indicators. Romania also shows a significant decrease (–6.07,

p = 0.002), indicating similarly reduced gender leadership outcomes. Poland, in contrast, does not differ significantly from Bulgaria (–0.68,

p = 0.72), suggesting comparable performance. Hungary and Romania face persistent structural or cultural barriers that hinder women's advancement into leadership roles, despite high education levels (

Table 2).

The Indicator Effects having as reference the Ministerial Positions: Parliament Seats exhibit the highest relative scores (+14.84,

p < 0.001), significantly outperforming ministerial roles. Top Managers show a modest but significant positive effect (+3.83,

p = 0.045), suggesting incremental progress in the private sector. Senior Management is not statistically different from ministerial roles (+0.66,

p = 0.72), indicating stagnation. The sharp contrast between parliament representation and ministerial roles suggests varying levels of gender openness depending on political versus executive domains (

Table 2).

The Time Trend (Year_Centered) coefficient is –0.78 (

p = 0.10), suggesting a small annual decline in overall gender leadership scores. Although not statistically significant, the negative direction aligns with observed stagnation or regression in some indicators. Structural progress is uneven or slowing, despite policy-level commitments to gender equity (e.g., SDGs) (

Table 2).

Confidence Intervals and Effect Size: The 95% confidence interval for Hungary (–10.28 to –2.79) confirms a robust effect. Romania has a similar drop (-9.81 to-2.32). For Parliament Seats the effect is also very high (11.10 to 18.59). For Top Managers, the interval (0.09 to 7.58) indicates uncertainty, but still excludes zero—supporting a real, if moderate, effect. For Poland, Senior management and Year the t-Statistic value is less than accepted threshold and the confidence interval contains zero, meaning that the effect is not significant.

Each figure aligns with key hypotheses and regression outputs.

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 4 and

Figure 6 support H1 by showing sectoral and country-level gaps in leadership roles.

Figure 3 and

Figure 5 support H3 by revealing the structural barriers tied to motherhood and part-time employment.

Figure 7 offers nuance to H2, reinforcing the need for deeper statistical analysis to confirm superficial visual trends.

Figure 1 aligns with the regression finding that Hungary and Romania underperform compared to Bulgaria in female leadership representation.

Figure 2 shows the structural volatility and stagnation in female political leadership, correlate with the negative coefficient observed for Hungary and Romania in the regression analysis.

Figure 3 supports the interpretation that motherhood-related constraints affect women’s organizational mobility and hinder their progression into leadership roles—thus also indirectly impacting LMX dynamics.

Figure 4 supports the regression variable “Senior Management” and Hypothesis H1. The stagnation and low representation of women in Romania and Hungary align with the insignificant regression coefficient for this indicator and the negative country effects.

Figure 5 supports LMX-related aspects of Hypotheses H1 and H3

Figure 6 reinforces the regression result showing “Parliament Seats” as the highest-performing indicator compared to “Ministerial Positions.”

Figure 7 gives additional context to Hypothesis H2. While Poland and Bulgaria report higher overall proportions of female managers, the regression results show these differences are not always statistically significant—especially in comparison with Bulgaria.

5. Discussions

The findings of this study provide a nuanced understanding of the structural and institutional factors influencing women's leadership outcomes in Eastern Europe. The regression results show that despite some improvements in education and representation, significant disparities persist in the advancement of women into top leadership roles.

5.1. Self-Efficacy and Structural Representation

The significant negative coefficients for Hungary and Romania suggest that these countries lag behind Bulgaria in terms of female leadership representation. Given the high educational attainment of women in these countries, the low leadership representation may reflect systemic barriers to self-efficacy at a societal level. This supports Bandura's argument that structural conditions influence the development and expression of self-efficacy. In our analysis, macro-level indicators—such as women in senior management and ministerial positions—act as proxies for this psychological construct.

5.2. LMX and Organizational Constraints

While LMX could not be measured directly, structural constraints like part-time employment and the employment gap related to parenthood serve as indicative of barriers to quality leader-member relationships. Countries with wider employment gaps for mothers may face reduced opportunities for building inclusive, trust-based relationships in teams, a hallmark of high-quality LMX. This is especially critical in cultures where leadership roles demand continuous availability, penalizing women with caregiving responsibilities.

5.3. Organizational Behavior and Indicator Differences

The results also highlight variation among different types of leadership indicators. The highest gender equality was found in parliamentary representation (+14.84 percentage points compared to ministerial roles), suggesting more openness in legislative roles versus executive decision-making. Top managerial roles showed modest improvement, while senior management roles exhibited no significant difference. This suggests that although some progress exists, it is not evenly distributed across sectors, hinting at inconsistent organizational behavior and inclusivity practices.

5.4. Time Trend and Stagnation Concerns

The slight negative time trend (–0.78 points/year) is not statistically significant but reinforces the concern that gains in gender equality are plateauing. This could be due to saturation effects in specific roles or persistent structural resistance to broader transformation.

5.5. Summary and Implications

Overall, the analysis suggests that women's leadership presence in Eastern Europe is shaped more by structural and cultural factors than by individual capabilities. Despite high levels of education among women, leadership roles remain disproportionately occupied by men. This disconnect highlights the need for interventions that go beyond education—such as institutional reforms, gender-sensitive work policies, and leadership development programs.

To promote female leadership more effectively, organizations and governments must address structural constraints, invest in mentoring and development, and foster organizational cultures that support equity and self-efficacy. Addressing these gaps can help translate educational achievements into actual leadership outcomes.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence of the structural challenges limiting women’s advancement into leadership roles in four Eastern European countries. Despite substantial progress in tertiary education attainment, the data reveal persistent gaps in the representation of women in top managerial, ministerial, and parliamentary positions. These findings suggest that education alone is insufficient to overcome entrenched barriers tied to gendered organizational norms and socio-cultural expectations.

By operationalizing self-efficacy, leader-member exchange (LMX), and organizational behavior using national-level indicators, this study bridges psychological theory with structural realities. The regression analysis highlights that countries such as Hungary and Romania significantly underperform compared to Bulgaria, and that roles in executive government (e.g., ministerial positions) are particularly resistant to gender parity. Moreover, the slight but consistent negative time trend underscores concerns about stagnation despite EU-level policy efforts.

The evidence suggests that fostering women’s leadership requires more than improving qualifications—it necessitates institutional reforms that target workplace equity, care-related employment penalties, and cultural norms about leadership. Countries must implement structural support systems such as parental leave equity, flexible work, and mentorship pipelines to enable high-quality LMX and bolster women’s self-efficacy.

Limitations While this study offers valuable cross-national insights, it is limited by its reliance on proxy variables to represent psychological and relational constructs. Indicators such as leadership representation and employment gaps can suggest patterns linked to self-efficacy and LMX but do not capture individual-level beliefs, motivations, or interpersonal dynamics. Therefore, the inferences drawn are suggestive rather than definitive. Additionally, the macro-level data do not account for within-country variation, organizational context, or intersectional influences such as ethnicity, class, or sector. Future research should integrate qualitative methods or survey-based psychological assessments to validate the theoretical assumptions and provide a richer understanding of the barriers to women’s leadership.

Future research should deepen this analysis using qualitative data or surveys to capture individual-level experiences behind the macro trends, and explore how organizational culture can either suppress or amplify women’s leadership trajectories. These efforts are essential to moving beyond symbolic gains and toward sustained, inclusive leadership development in Eastern Europe and beyond.

References

- Asghar, F., Mahmood, S., Iqbal Khan, K., Gohar Qureshi, M., & Fakhri, M. (2022). Eminence of Leader Humility for Follower Creativity During COVID-19: The Role of Self-Efficacy and Proactive Personality. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 790517. [CrossRef]

- Bracht, EM; Keng-Highberger, FT; (...); Huang, YM (2021) Take a "Selfie": Examining How Leaders Emerge From Leader Self-Awareness, Self-Leadership, and Self-Efficacy, Frontiers in Psychology, 12.

- Bucea-Manea-Țoniş, Rocsana, Viktor Prokop, Dragan Ilic, Elena Gurgu, Radu Bucea-Manea-Țoniş, Cezar Braicu, and Alina Moanță. (2021). The Relationship between Eco-Innovation and Smart Working as Support for Sustainable Management" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1437. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Woo-Sung, Seung-Wan Kang, and Suk Bong Choi. 2021. "Innovative Behavior in the Workplace: An Empirical Study of Moderated Mediation Model of Self-Efficacy, Perceived Organizational Support, and Leader-Member Exchange" Behavioral Sciences 11, no. 12: 182. [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, Adin-Marian, Marilena Cojocaru, Anca Jianu, Rocsana Bucea-Manea-Țoniş, Dan Gheorghe Păun, and Paula Ivan. (2022) The Impact of Agile Management and Technology in Teaching and Practicing Physical Education and Sports" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1237. [CrossRef]

- Edison, R.E.; Juhro, S.M.; Aulia, A.F. Transformational Leadership, and Neurofeedback: The Medical Perspective of Neuroleadership. Internat. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2019, 8, 46–62.

- EU1, 2024, EUROSTAT data available online https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/womenmen/bloc-2a.html?lang=en, accessed September 15th 2024.

- EU2, 2024, Population by educational attainment level, sex and age (%)/Tertiary education (levels 5-8), available online https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/EDAT_LFS_9903__custom_1290134/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=1e41534c-23a1-48a7-a6b3-cd69444d3001, accessed September 15th 2024.

- EU3, 2024, the Employment rate of adults by sex, age groups, educational attainment level, number of children, and age of the youngest child (%), available online https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFST_HHEREDCH__custom_3724312/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=49c7a2c7-2a9a-41ab-817b-d4c27c46b5ed, accessed September 15th, 2024.

- EU4, 2024, Percentage of part-time employment of adults by sex, age groups, number of children and age of youngest child, available online https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFST_HHPTECHI__custom_3724335/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=787ada5b-3caa-4b86-8b88-452a9dbc1261, accessed September 15th 2024.

- EU5, 2024, Lifeline of women and men in RO_PL_HU_BG, available online https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/womenmen/bloc-1a.html?lang=en, accessed September 15th, 2024.

- EU6, 2024, Managers - Employment by sex, age, professional status and occupation (1 000), available online https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/LFSA_EGAIS__custom_5271507/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=9a0280db-fa89-4452-9aaf-0ca61f44817d, accessed September 15th 2024.

- Gu, Q., Hempel, P. S., and Yu, M. (2020). Tough love and creativity: how authoritarian leadership tempered by benevolence or morality influences employee creativity. Br. J. Manag. 31, 305–324. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.A.; Thingvad, P.S. Managing employee innovative behavior through transformational and transactional leadership styles. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 918–944.

- Icekson, T; Kaye-Tzadok, A and Ben-David, Y (2024) Leaders in Times of Transition: Virtual Self-Efficacy, Participant Behaviors, and Leader Perceptions of Adaptive Interpersonal Group Processes, Group Dynamics-Theory Research and Practice 28 (1), pp.1-16.

- Kim, SL; Lee, D and Yun, S (2022) Leader boundary-spanning behavior and creative behavior: the role of need for status and creative self-efficacy, Leadership & Organization Development Journal 43 (6), pp.835-846.

- Le, P.B.; Lei, H. Determinants of innovation capability: The roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing, and perceived organizational support. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 527–547.

- Li, W.; Bhutto, T.A.; Xuhui, W.; Maitlo, Q.; Zafar, A.U.; Bhutto, N. Unlocking Employees’ Green Creativity: The Effects of Green Transformational Leadership, Green Intrinsic, and Extrinsic Motivation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 1–10.

- Liu, J; Wang, J; (...); Wang, YF (2021) Linking leader-member exchange to employee voice behavior: The mediating role of self-efficacy, Social Behavior, and Personality, 49 (12).

- McLarty, B.D.; Muldoon, J.; Quade, M.; King, R.A. Your boss is the problem and solution: How supervisor-induced hindrance stressors and LMX influence employee job neglect and subsequent performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 308–317.

- Mustafa, G; Mubarak, N; (...); Riaz, A (2023) Impact of Leader-Member Exchange on Innovative Work Behavior of Information Technology Project Employees; Role of Employee Engagement and Self-Efficacy, Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 35 (4), pp.581-599.

- Naranjo-Valencia, J. C., Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2011). Innovation or imitation? The role of organizational culture. Management Decision, 49(1), 55–72. [CrossRef]

- Nilawati Fiernaningsih, P.H.M. Antecedents of variables that affect innovative behavior in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. PalArch's J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 1492–1498.

- Sareen, A and Pandey, S (2022), Organizational Innovation in Knowledge Intensive Business Services: The role of Networks, Culture, and Resources for Innovation, FIIB Business Review 11 (1), pp.107-118.

- Sawitri, HSR; Suyono, J; (...); Sunaryo, S (2021) Linking Leaders' Political Skill and Ethical Leadership to Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Roles of Self-Efficacy, Respect, and Leader-Member Exchange, International Journal of Business, 26 (4), pp.70-89.

- Scaliza, JAA; Jugend, D; (...); Andrade, DF (2022) Relationships among organizational culture, open innovation, innovative ecosystems, and performance of firms: Evidence from an emerging economy context, JOURNAL OF BUSINESS RESEARCH 14, pp.264-279. [CrossRef]

- Sher, P.J.-H.; Zhuang, W.-L.; Wang, M.-C.; Peng, C.-J.; Lee, C.-H. Moderating effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between leader-member exchange and expatriate voice in multinational banks. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2019, 41, 898–913.

- Sohn, Y.W.; Kang, Y.J. Two-sided Effect of Empowering Leadership on Follower’s Job Stress: The Mediation Effect of Self-efficacy and Felt Accountability and Moderated Mediation by Perceived Organizational Support. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 33, 373–407.

- Song, Z., Gu, Q., and Cooke, F. L. (2020). The effects of high-involvement work systems and shared leadership on team creativity: a multilevel investigation. Hum. Resour. Manag. 59, 201–213. [CrossRef]

- Souki, K; Aad, SS and Karkoulian, S (2024) The impact of 360-degree feedback on innovative behavior within the organization: the mediating role of organizational justice, International Journal of Organizational Analysis.

- Sürücü, L., Maslakçi, A. and Sesen, H. (2022), Transformational leadership, job performance, self-efficacy, and leader support: testing a moderated mediation model, Baltic Journal of Management, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 467-483. [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, FO; Mayer, DM; (...); Christensen, AL (2011), PUBLICATION WITH EXPRESSION OF CONCERN Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader-member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification (Publication with Expression of Concern), Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 115 (2), pp.204-213. 204–213.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).