Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

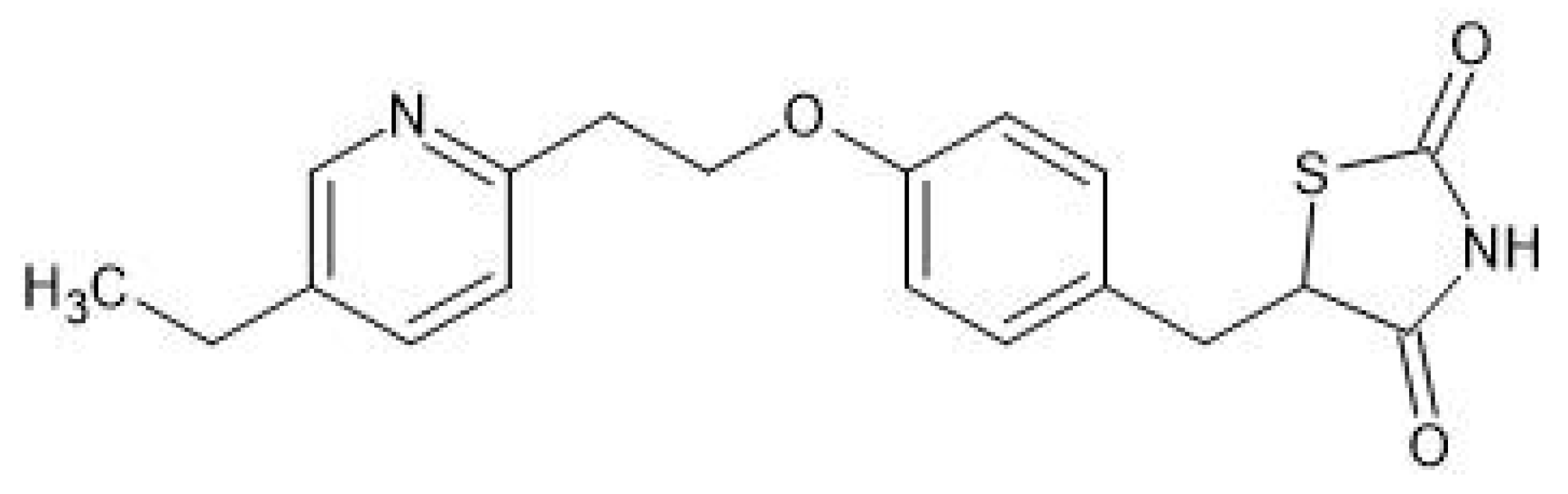

2. Overview of Pioglitazone

3. Therapeutic Use of Pioglitazone

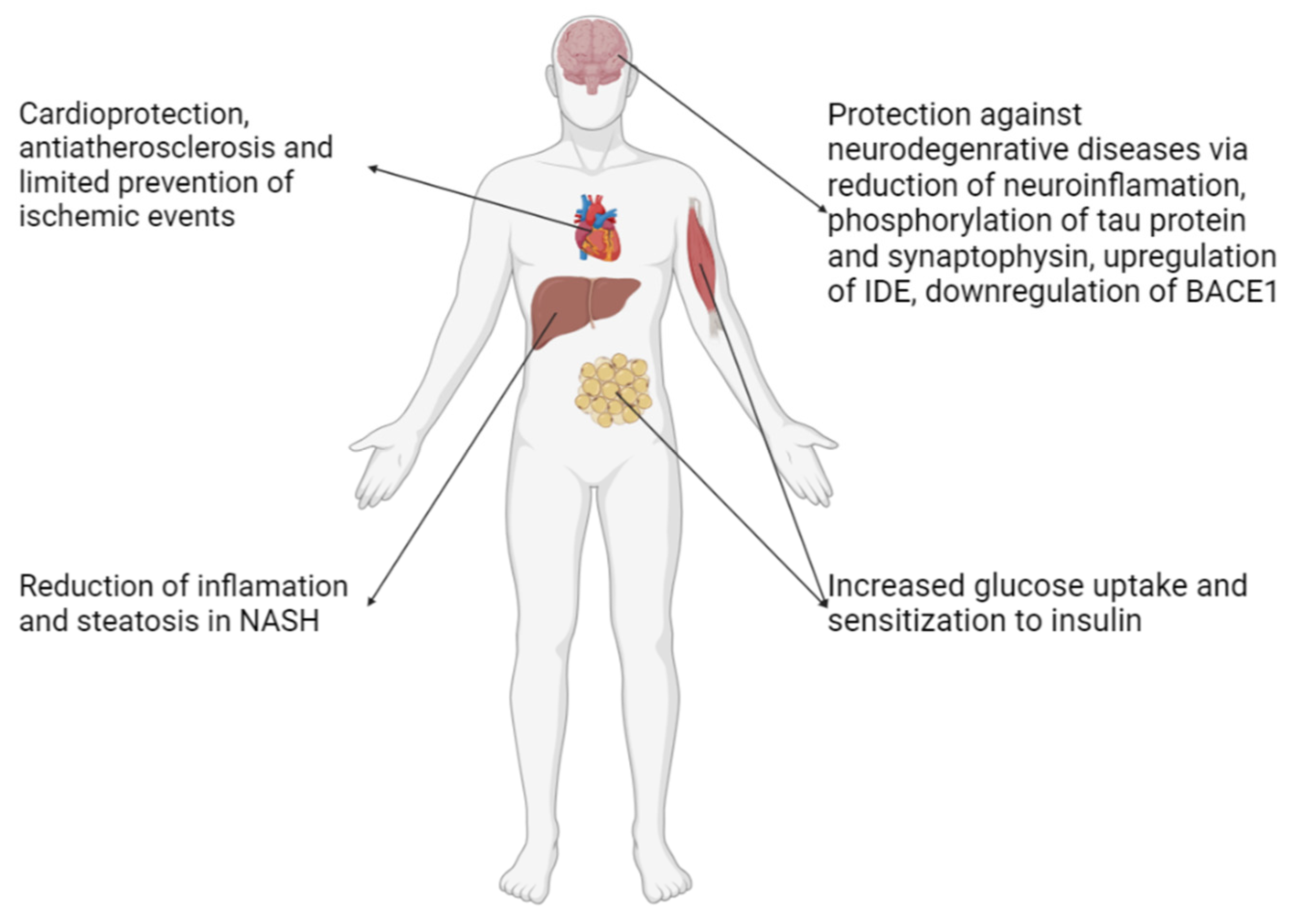

3.1. Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 (T2DM)

3.2. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)

3.3. Cardiovascular Protection

3.4. Neurodegenerative Diseases (NDs)

3.5. Anticancer Properties

3.5.1. Overview

3.5.2. Molecular Pharmacology

3.6. Therapeutic Effect on Different Types of Cancer

3.6.1. Breast Cancer

3.6.2. Lung Cancer

- The use with EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors such as geftinib for NSCLC as it was found that PPARγ mediated upregulation of Phosphate and Tensin homolog (PTEN) downregulated the PI3K/Akt pathway that is correlated to resistance to said TKIs [72].

- Combination of pioglitazone with clarithromycin and a relatively small dose of chemotherapeutic agent was compared against nivolumab in the ModuLung trial by Heudobler et al. (2021) [73]. This trial was terminated early due to the approval of checkpoint inhibitors as first line treatment, with the conclusion that nivolumab was superior to this combination therapy however with difference of the overall survival rate and quality of life between the two regimens being similar, the latter seems to be a viable alternative to be assessed in future trials and be considered in cases that there are few other options [73].

3.6.3. Renal Cancer

3.6.4. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

3.6.5. Colorectal Cancer

3.6.6. Thyroid Cancer

3.6.7. Glioma

3.6.8. Hematological Malignancies

3.6.9. Pancreatic Cancer

3.7. Immunotherapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rangwala, S. M.; Lazar, M. A. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ in Diabetes and Metabolism. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2004, 25, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olefsky, J. M. Treatment of Insulin Resistance with Peroxisome Proliferator–Activated Receptor γ Agonists. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2000, 106, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegelman, B. M. PPAR-Gamma: Adipogenic Regulator and Thiazolidinedione Receptor. Diabetes 1998, 47, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szychowski, K. A.; Leja, M. L.; Kaminskyy, D. V.; Kryshchyshyn, A. P.; Binduga, U. E.; Pinyazhko, O. R.; Lesyk, R. B.; Tobiasz, J.; Gmiński, J. Anticancer Properties of 4-Thiazolidinone Derivatives Depend on Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ). European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 141, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towfighi, A.; Ovbiagele, B. Partial Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Agonist Angiotensin Receptor Blockers. Cerebrovascular Diseases 2008, 26, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M. A.; Mattison, D. R.; Azoulay, L.; Krewski, D. Thiazolidinedione Drugs in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Past, Present and Future. Critical reviews in toxicology 2018, 48, 52–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Byrne, C. D.; Scorletti, E.; Mantzoros, C. S.; Targher, G. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Hyperglycaemic Drugs in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with or without Diabetes: An Updated Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes & Metabolism 2020, 46, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, N.; Genda, K. Pioglitazone (Actos, Glustin). Drug Discovery in Japan 2019, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devchand, P. R.; Liu, T.; Altman, R. B.; FitzGerald, G. A.; Schadt, E. E. The Pioglitazone Trek via Human PPAR Gamma: From Discovery to a Medicine at the FDA and Beyond. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Peñalver, J. J.; Martín-Timón, I.; Sevillano-Collantes, C.; Cañizo-Gómez, F. J. del. Update on the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. World Journal of Diabetes 2016, 7, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. (2024). Actos: EPAR - Product Information. Retrieved from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/actos-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Schernthaner, G.; Currie, C. J.; Schernthaner, G.H. . Do We Still Need Pioglitazone for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes? A Risk-Benefit Critique in 2013. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanis, S. P.; Parker, T. T.; Colca, J. R.; Fisher, R. M.; Kletzein, R. F. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Metabolites of the Antidiabetic, Antihyperglycemic Agent Pioglitazone. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 1996, 39, 5053–5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Majed, A.; Bakheit, A. H. H.; Abdel Aziz, H. A.; Alharbi, H.; Al-Jenoobi, F. I. Pioglitazone. Profiles of Drug Substances, Excipients and Related Methodology 2016, 379–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahla Soltanpour; Fatemeh Zohrabi; Zahra Bastami. Thermodynamic Solubility of Pioglitazone HCl in Polyethylene Glycols 200, 400 or 600+Water Mixtures at 303.2 and 308.2K—Data Report and Modeling. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2014, 379, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloshe, S. P.; Chougule, D. D.; Shah, R. R.; Ghodke, D. S.; Pawar, N. D.; Ghaste, R. P. Effect of Method of Preparation on Pioglitazone HCl-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutics 2010, 4, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, S.; Arshad, S.; Kamal, Y.; Imran, S.; Mulazim Hussain Asim; Mahmood, A. ; Inam, S.; Hafiz Muhammad Irfan; Riaz, H. Pioglitazone-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: In-Vitro and In-Vivo Evaluation for Improved Bioavailability. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 79, 104041–104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Matzger, A. J. A Newly Discovered Racemic Compound of Pioglitazone Hydrochloride Is More Stable than the Commercial Conglomerate. Crystal Growth & Design 2017, 17, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckland, D.; Danhof, M. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Pioglitazone. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes 2000, 108, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. I.; Yazdi, Z. S.; Beitelshees, A. L. Pharmacological Treatment of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebovitz, H. E. Thiazolidinediones: The Forgotten Diabetes Medications. Current Diabetes Reports 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Islam, Md. A.; Mohamed, M.; Ahmad, I.; Kamal, M. A.; Donnelly, R.; Idris, I.; Gan, S. H. Efficacy and Safety of Pioglitazone Monotherapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Scientific Reports 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Bu, H.; Takahashi, H. Pioglitazone on Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 15 RCTs. Medicine 2022, 101, e31508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Du, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, Y.; Ma, C.; Chen, H.; Li, M.; Tian, J.; Xue, C.; Long, G.; Xu, M.-D.; Jiang, Y. Response to Pioglitazone in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients with vs. without Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Pepa, G.; Russo, M.; Vitale, M.; Carli, F.; Vetrani, C.; Masulli, M.; Riccardi, G.; Vaccaro, O.; Gastaldelli, A.; Rivellese, A. A.; Bozzetto, L. Pioglitazone Even at Low Dosage Improves NAFLD in Type 2 Diabetes: Clinical and Pathophysiological Insights from a Subgroup of the TOSCA.IT Randomised Trial. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2021, 178, 108984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, I.; Yasir, M.; Sarfraz, S. ; Gandhala Shlaghya; Narayana, S.; Mushtaq, U.; Basim Shaman Ameen; Nie, C.; Nechi, D.; Sai Sri Penumetcha. Vitamin E and Pioglitazone: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Their Efficacy in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, A. J.; Chalasani, N.; Kowdley, K. V.; McCullough, A.; Diehl, A. M.; Bass, N. M.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B. A.; Lavine, J. E.; Tonascia, J.; Unalp, A.; Van Natta, M.; Clark, J.; Brunt, E. M.; Kleiner, D. E.; Hoofnagle, J. H.; Robuck, P. R. Pioglitazone, Vitamin E, or Placebo for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 362, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R. A.; Inzucchi, S.; Abdul-Ghani, M.; Nissen, S. E. Pioglitazone: The Forgotten, Cost-Effective Cardioprotective Drug for Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research 2019, 16, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernan, W. N.; Viscoli, C. M.; Furie, K. L.; Young, L. H.; Inzucchi, S. E.; Gorman, M.; Guarino, P. D.; Lovejoy, A. M.; Peduzzi, P. N.; Conwit, R.; Brass, L. M.; Schwartz, G. G.; Adams, H. P.; Berger, L.; Carolei, A.; Clark, W.; Coull, B.; Ford, G. A.; Kleindorfer, D.; O’Leary, J. R. Pioglitazone after Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Saver, J. L.; Liao, H.-W.; Lin, C.-H.; Ovbiagele, B. Pioglitazone for Secondary Stroke Prevention. Stroke 2017, 48, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.-Y.; Ma, Z.G.; Xu, S.C.; Zhang, N.; Tang, Q.Z. Pioglitazone Protected against Cardiac Hypertrophy via Inhibiting AKT/GSK3βand MAPK Signaling Pathways. PPAR Research 2016, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilginoglu, A. Cardiovascular Protective Effect of Pioglitazone on Oxidative Stress in Rats with Metabolic Syndrome. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 2019, 82, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ji, X.; Wang, X.; Shen, L.; Wang, Y. Pioglitazone for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes in Patients with or at High Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhowail, A.; Alsikhan, R.; Alsaud, M.; Aldubayan, M.; Rabbani, S. I. Protective Effects of Pioglitazone on Cognitive Impairment and the Underlying Mechanisms: A Review of Literature. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2022, 16, 2919–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, Q.; Qian, Y.; Li, X.; Li, M. Pioglitazone Reduces β Amyloid Levels via Inhibition of PPARγ Phosphorylation in a Neuronal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanian, M.Y.; Terefe, E.M.; Taheri, N.; Kujawska, M.; Tork, Y.J.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Shoukat, S.; Jade, M.; Heidari, M.; Alesaeidi, S. Neuroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Pioglitazone on Parkinson’s Disease: A Comprehensive Narrative Review of Clinical and Experimental Findings. CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets 2023, 22, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, B. The Oral Antidiabetic Pioglitazone Protects from Neurodegeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-like Symptoms in Superoxide Dismutase-G93A Transgenic Mice. Journal of Neuroscience 2005, 25, 7805–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.; Li, S.; Gao, F.; Xue, G. The Role of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Understanding and Future Therapeutic Targets. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M. T.; Fink, A.; Doblhammer, G. Effect of Pioglitazone Medication on the Incidence of Dementia. Annals of Neurology 2015, 78, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Shi, W.; Fu, S.; Wang, T.; Zhai, S.; Song, Y.; Han, J. Pioglitazone and Bladder Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancer Medicine 2018, 7, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A. Pioglitazone Suspension and Its Aftermath: A Wake up Call for the Indian Drug Regulatory Authorities. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics 2013, 4, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A. Z.; Althagafi, I. I.; Shamshad, H. Role of PPAR Receptor in Different Diseases and Their Ligands: Physiological Importance and Clinical Implications. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2019, 166, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefnia, S.; Momenzadeh, S.; Forootan, F.S.; Ghaedi, K.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. The Influence of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ (PPARγ) Ligands on Cancer Cell Tumorigenicity. Gene 2018, 649, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lei, F.; Lin, Y.; Han, Y.; Yang, L.; Tan, H. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors as Therapeutic Target for Cancer. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2023, 28, 17931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, T.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, K.; Xie, F.; Liao, Z.; Wei, P. PPAR-γ Modulators as Current and Potential Cancer Treatments. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, 737776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, X. X.; Lin, S. Y.; Lian, S. X.; Qiu, Y. R.; Li, Z. H.; Chen, Z. H.; Lu, W. Q.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, G. H. Inhibition of the Breast Cancer by PPARγ Agonist Pioglitazone through JAK2/STAT3 Pathway. Neoplasma 2020, 67, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, L.; Sarkar, M.; Deb, A.; Giri, B. Pioglitazone, an Anti-Diabetic Drug Requires Sustained MAPK Activation for Its Anti-Tumor Activity in MCF7 Breast Cancer Cells, Independent of PPAR-γ Pathway. Pharmacological Reports 2016, 68, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.H.; Han, S.H.; Park, J.I. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ and PGC-1α in Cancer: Dual Actions as Tumor Promoter and Suppressor. PPAR Research 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, W.; You, M.; Xu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Jin, J. Pioglitazone Inhibits EGFR/MDM2 Signaling-Mediated PPARγ Degradation. European Journal of Pharmacology 2016, 791, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, V.; Nicolosi, M. L.; Giuliano, S.; Bellomo, M.; Belfiore, A.; Malaguarnera, R. PPAR-γ Agonists as Antineoplastic Agents in Cancers with Dysregulated IGF Axis. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.H.; Han, S.H.; Park, J.I. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ and PGC-1α in Cancer: Dual Actions as Tumor Promoter and Suppressor. PPAR Research 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masanobu Tsubaki; Takeda, T. ; Tomonari, Y.; Kawashima, K.; Itoh, T.; Imano, M.; Satou, K.; Nishida, S. Pioglitazone Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth through STAT3 Inhibition and Enhanced AIF Expression via a PPARγ-Independent Pathway. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2017, 233, 3638–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrod, H. A.; Sun, S.-Y. PPARγ and Apoptosis in Cancer. PPAR Research 2008, 2008, 704165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J. H.; Lee, T.J.; Sung, E.G.; Song, I.H.; Kim, J.Y. Pioglitazone Mediates Apoptosis in Caki Cells via Downregulating C-FLIP(L) Expression and Reducing Bcl-2 Protein Stability. Oncology Letters 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.I.; Kwak, J.Y. The Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in Colorectal Cancer. PPAR Research 2012, 2012, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballav, S.; Biswas, B.; Sahu, V. K.; Ranjan, A.; Basu, S. PPAR-γ Partial Agonists in Disease-Fate Decision with Special Reference to Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yu, L.; Qu, X.; Huang, T. The Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors in the Tumor Microenvironment, Tumor Cell Metabolism, and Anticancer Therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14, 1184794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicitore, A.; Caraglia, M.; Gaudenzi, G.; Manfredi, G.; Amato, B.; Mari, D.; Persani, L.; Arra, C.; Vitale, G. Type I Interferon-Mediated Pathway Interacts with Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor-γ (PPAR-γ): At the Cross-Road of Pancreatic Cancer Cell Proliferation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2014, 1845, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Weiser-Evans, M.C.M.; Nemenoff, R. Anti- and Protumorigenic Effects of PPARγin Lung Cancer Progression: A Double-Edged Sword. PPAR Research 2012, 2012, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Quiles, M.; Broekema, M. F.; Kalkhoven, E. PPARgamma in Metabolism, Immunity, and Cancer: Unified and Diverse Mechanisms of Action. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2021, 12, 624112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Qian, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Hussain, S.; Jin, J.; Shi, J.; Hou, Y. PPARγ Agonist Pioglitazone Enhances Colorectal Cancer Immunotherapy by Inducing PD-L1 Autophagic Degradation. European Journal of Pharmacology 2023, 950, 175749–175749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Young Yoo; Yang, S. -H.; Jung Eun Lee; Deog Gon Cho; Hoon Kyo Kim; Sung Hwan Kim; Il Sup Kim; Jae Taek Hong; Jae Hoon Sung; Byung Chul Son; Sang Won Lee. E-Cadherin as a Predictive Marker of Brain Metastasis in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer, and Its Regulation by Pioglitazone in a Preclinical Model. Journal of Neuro-Oncology 2012, 109, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella, V.; Ferdinando Carlo Sasso; Raimondo Di Liello; Della, M. ; Barra, G.; Viscardi, G.; Esposito, G.; Sparano, F.; Troiani, T.; Martinelli, E.; Orditura, M.; Ferdinando De Vita; Ciardiello, F.; Morgillo, F. Activity and Molecular Targets of Pioglitazone via Blockade of Proliferation, Invasiveness and Bioenergetics in Human NSCLC. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.H. Pioglitazone and Breast Cancer Risk in Female Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. BMC Cancer 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormandy, J.; Bhattacharya, M.; van Troostenburg de Bruyn, A.-R. Safety and Tolerability of Pioglitazone in High-Risk Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Drug Safety 2009, 32, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakouti, P.; Mohammadi, M.; Boshagh, M. A.; Amini, A.; Rezaee, M. A.; Rahmani, M. R. Combined Effects of Pioglitazone and Doxorubicin on Migration and Invasion of MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaginis, C.; Politi, E.; Alexandrou, P.; Sfiniadakis, J.; Kouraklis, G.; Theocharis, S. Expression of Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor-Gamma (PPAR-γ) in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma: Correlation with Clinicopathological Parameters, Proliferation and Apoptosis Related Molecules and Patients’ Survival. Pathology & Oncology Research 2012, 18, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, S. P.; Reddy, A. T.; Banno, A.; Reddy, R. C. PPAR Agonists for the Prevention and Treatment of Lung Cancer. PPAR Research 2017, 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R. L.; Blatchford, P. J.; Merrick, D. T.; Bunn, P. A.; Bagwell, B.; Dwyer-Nield, L. D.; Jackson, M. K.; Geraci, M. W.; Miller, Y. E. A Randomized Phase II Trial of Pioglitazone for Lung Cancer Chemoprevention in High-Risk Current and Former Smokers. Cancer Prevention Research 2019, 12, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabloom, D. E.; Galbraith, A. R.; Haynes, A. M.; Antonides, J. D.; Wuertz, B. R.; Miller, W. A.; Miller, K. A.; Steele, V. E.; Mark Steven Miller; Clapper, M. L.; M. Gerard O'Sullivan; Ondrey, F. G. Fixed-Dose Combinations of Pioglitazone and Metformin for Lung Cancer Prevention. Cancer Prevention Research 2017, 10, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabloom, D. E.; Galbraith, A. R.; Haynes, A. M.; Antonides, J. D.; Wuertz, B. R.; Miller, W. A.; Miller, K. A.; Steele, V. E.; Suen, C. S.; M. Gerard O'Sullivan; Ondrey, F. G. Safety and Preclinical Efficacy of Aerosol Pioglitazone on Lung Adenoma Prevention in A/J Mice. Cancer Prevention Research 2017, 10, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth K.W., To; William K.K., Wu; Herbert, H.F. Loong. PPARgamma Agonists Sensitize PTEN-Deficient Resistant Lung Cancer Cells to EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors by Inducing Autophagy. European journal of pharmacology 2018, 823, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heudobler, D.; Schulz, C.; Fischer, J. R.; Staib, P.; Wehler, T.; Südhoff, T.; Schichtl, T.; Wilke, J.; Hahn, J.; Florian Lüke; Vogelhuber, M. ; Klobuch, S.; Pukrop, T.; Herr, W.; Held, S.; Beckers, K.; Bouche, G.; Reichle, A. A Randomized Phase II Trial Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of Pioglitazone, Clarithromycin and Metronomic Low-Dose Chemotherapy with Single-Agent Nivolumab Therapy in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated in Second or Further Line (ModuLung). Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 599598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, A.V.V.V.R.; Kumari, G. K.; Krishnamurthy, P. T. Preliminary Evaluation of Anticancer Efficacy of Pioglitazone Combined with Celecoxib for the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Investigational New Drugs 2022, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S. W. Anticancer Actions of PPARγ Ligands: Current State and Future Perspectives in Human Lung Cancer. World Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-H. Pioglitazone Does Not Affect the Risk of Kidney Cancer in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolism 2014, 63, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piątkowska-Chmiel, I.; Gawrońska-Grzywacz, M.; Natorska-Chomicka, D.; Herbet, M.; Sysa, M.; Iwan, M.; Korga, A.; Dudka, J. Pioglitazone as a Modulator of the Chemoresistance of Renal Cell Adenocarcinoma to Methotrexate. Oncology Reports 2020, 43, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.F.; El Shazly, S.M. Pioglitazone Protects against Cisplatin Induced Nephrotoxicity in Rats and Potentiates Its Anticancer Activity against Human Renal Adenocarcinoma Cell Lines. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 51, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, S.Z.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Ma, Y.L.; Zhang, P.; Qin, H.L. Decreased Risk of Liver Cancer with Thiazolidinediones Therapy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Results from a Meta-Analysis. Hepatology 2013, 58, 835–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ghoshal, S.; Sojoodi, M.; Arora, G.; Masia, R.; Erstad, D. J.; Lanuti, M.; Hoshida, Y.; Baumert, T.; Tanabe, K.K.; Fuchs, B.C. Pioglitazone Reduces Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development in Two Rodent Models of Cirrhosis. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2019, 23, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, L.H.; Huang, B.; Wang, R.Y.; Yuan, S.X.; Tao, Q.F.; Xu, Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Lin, C.; Zhou, W.P. Pioglitazone, a PPARγ Agonist, Inhibits Growth and Invasion of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Blockade of the Rage Signaling. Molecular Carcinogenesis 2014, 54, 1584–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, M.; Wang, M.; Xu, W.; Duan, X.; Han, X.; Ren, J. Pioglitazone, a Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Agonist, Induces Cell Death and Inhibits the Proliferation of Hypoxic HepG2 Cells by Promoting Excessive Production of Reactive Oxygen Species. Oncology Letters 2024, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.T.; Liu, Y.; Jin, P.P.; Sun, X.C. Thiazolidinediones and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology 2018, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Valente, S.; Chaimbault, P.; Schohn, H. Evaluation of Δ2-Pioglitazone, an Analogue of Pioglitazone, on Colon Cancer Cell Survival: Evidence of Drug Treatment Association with Autophagy and Activation of the Nrf2/Keap1 Pathway. International Journal of Oncology 2014, 45, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano, S.; Kubota, T.; Nishibori, H.; Hasegawa, H.; Ishii, Y.; Nitori, N.; Ochiai, H.; Okabayashi, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Kitajima, M. Pioglitazone, a Ligand for Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ Acts as an Inhibitor of Colon Cancer Liver Metastasis. Anticancer Research 2008, 28, 3593–3599. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Qian, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Hussain, S.; Jin, J.; Shi, J.; Hou, Y. PPARγ Agonist Pioglitazone Enhances Colorectal Cancer Immunotherapy by Inducing PD-L1 Autophagic Degradation. European Journal of Pharmacology 2023, 950, 175749–175749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahima Danesh Pouya; Salehi, R. ; Yousef Rasmi; Fatemeh Kheradmand; Anahita Fathi-Azarbayjani. Combination Chemotherapy against Colorectal Cancer Cells: Co-Delivery of Capecitabine and Pioglitazone Hydrochloride by Polycaprolactone-Polyethylene Glycol Carriers. Life Sciences 2023, 332, 122083–122083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushchayeva, Y.; Kushchayev, S.; Jensen, K.; Brown, R. J. Impaired Glucose Metabolism, Anti-Diabetes Medications, and Risk of Thyroid Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Grachtchouk, V.; Qin, T.; Lumeng, C. N.; Sartor, M. A.; Koenig, R. J. Genomic Binding of PAX8-PPARG Fusion Protein Regulates Cancer-Related Pathways and Alters the Immune Landscape of Thyroid Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; O’Donnell, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sartor, M. A.; Koenig, R. J. Adipogenic Differentiation of Thyroid Cancer Cells through the Pax8-PPARγ Fusion Protein Is Regulated by Thyroid Transcription Factor 1 (TTF-1). Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 19274–19286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; Coperchini, F.; Croce, L.; Magri, F. ; Marsida Teliti; Rotondi, M. Drug Repositioning in Thyroid Cancer Treatment: The Intriguing Case of Anti-Diabetic Drugs. Frontiers in pharmacology 2023, 14, 1303844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, T. J.; Haugen, B. R.; Sherman, S. I.; Shah, M. H.; Caoili, E. M.; Koenig, R. J. Pioglitazone Therapy of PAX8-PPARγ Fusion Protein Thyroid Carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2018, 103, 1277–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir Kutbay, N.; Biray Avci, C.; Sarer Yurekli, B.; Caliskan Kurt, C.; Shademan, B.; Gunduz, C.; Erdogan, M. Effects of Metformin and Pioglitazone Combination on Apoptosis and AMPK/MTOR Signaling Pathway in Human Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer Cells. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology 2020, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basilotta, R.; Lanza, M.; Casili, G.; Chisari, G.; Munao, S.; Colarossi, L.; Cucinotta, L.; Campolo, M.; Esposito, E.; Paterniti, I. Potential Therapeutic Effects of PPAR Ligands in Glioblastoma. Cells 2022, 11, 621–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grommes, C.; Karlo, J. C.; Caprariello, A.; Blankenship, D.; DeChant, A.; Landreth, G. E. The PPARγ Agonist Pioglitazone Crosses the Blood–Brain Barrier and Reduces Tumor Growth in a Human Xenograft Model. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 2013, 71, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtor, T.; Spagnolo, A.; Glick, R. P.; Feinstein, D. L. PPAR- Thiazolidinedione Agonists and Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Brain Tumors. PPAR Research 2008, 2008, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, J.; Amiridis, S.; Stylli, S. S.; Morokoff, A. P.; O’Brien, T. J.; Kaye, A. H. A Novel Treatment Strategy for Glioblastoma Multiforme and Glioma Associated Seizures: Increasing Glutamate Uptake with PPARγ Agonists. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2015, 22, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Shi, W.; Shao, B.; Shi, J.; Shen, A.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Lan, Q. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Agonist Pioglitazone Inhibits β-Catenin-Mediated Glioma Cell Growth and Invasion. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2011, 349, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, S.; Coras, R.; Tränkle, C.; Zlotos, D. P.; Ingmar Blümcke; Lars Tatenhorst; Heneka, M. T.; Hahnen, E. PPAR Gamma Activators: Off-Target against Glioma Cell Migration and Brain Invasion. PPAR Research 2008, 2008, 513943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, J.; Amiridis, S.; Stylli, S. S.; Bjorksten, A. R.; Kountouri, N.; Zheng, T.; Paradiso, L.; Luwor, R. B.; Morokoff, A. P.; O’Brien, T. J.; Kaye, A. H. The Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Gamma Agonist Pioglitazone Increases Functional Expression of the Glutamate Transporter Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter 2 (EAAT2) in Human Glioblastoma Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 21301–21314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilibrasi, C.; Butta, V.; Riva, G.; Bentivegna, A. Pioglitazone Effect on Glioma Stem Cell Lines: Really a Promising Drug Therapy for Glioblastoma? PPAR Research 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Pérez, J. H.; Kirches, E.; Mawrin, C.; Firsching, R.; Schneider, T. Cytotoxic Effect of Different Statins and Thiazolidinediones on Malignant Glioma Cells. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 2010, 67, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Pérez, J.H.; Preininger, R.; Kirches, E.; Reinhold, A.; Butzmann, J.; Prilloff, S.; Mawrin, C.; Schneider, T. Simultaneous Administration of Statins and Pioglitazone Limits Tumor Growth in a Rat Model of Malignant Glioma. Anticancer Research 2016, 36, 6357–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, C.K.; Alphonse-Sullivan, N.K.; Isom, S.; Metheny-Barlow, L.J.; Cummings, T.L.; Page, B.R.; Brown, D.; Blackstock, A. W.; Peiffer, A.M.; Strowd, R.E.; Rapp, S.R.; Lesser, G.J.; Shaw, E.G.; Chan, M.D. Safety of Pioglitazone during and after Radiation Therapy in Patients with Brain Tumors: A Phase I Clinical Trial. 2019, 145, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, S.; Salari, S.; Kaveh, V.; Ghaffari, S. H.; Bashash, D. Alteration of PPAR-GAMMA (PPARG; PPARγ) and PTEN Gene Expression in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients and the Promising Anticancer Effects of PPARγ Stimulation Using Pioglitazone on AML Cells. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 2021, 9, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiki, M.; Hatta, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Itoh, T.; Enomoto, Y.; Takeuchi, J.; Sawada, U.; Aizawa, S.; Horie, T. Pioglitazone Inhibits the Growth of Human Leukemia Cell Lines and Primary Leukemia Cells While Sparing Normal Hematopoietic Stem Cells. International Journal of Oncology 2006, 29, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Póvoa, V. M. O.; Delafiori, J.; Dias-Audibert, F. L.; de Oliveira, A. N.; Lopes, A. B. P.; de Paula, E. V.; Pagnano, K. B. B.; Catharino, R. R. Metabolic Shift of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients under Imatinib–Pioglitazone Regimen and Discontinuation. Medical Oncology 2021, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, D. S.; Lee, M. W.; Lee, J. W.; Sung, K. W.; Koo, H. H.; Yoo, K. H. Anti-Leukemic Effects of PPARγ Ligands. Cancer Letters 2018, 418, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, S.; Tetsuzo Tauchi; Tanaka, Y. ; Kazuma Ohyashiki. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors: Targets for the Treatment of Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Leukemia Cells. Blood 2017, 130, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, S.; Yousefi, A.-M.; Delshad, M.; Davood Bashash. Synergistic Effects of PI3K Inhibition and Pioglitazone against Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Cells. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine 2022, 11, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, Y.; Yousefi, A.-M.; Davood Bashash. Inhibition of PI3K Signaling Intensified the Antileukemic Effects of Pioglitazone: New Insight into the Application of PPARγ Stimulators in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion 2023, 39, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiany, M.; Tabarraee, M.; Salari, S.; Haghighi, S.; Rezvani, H.; Ghasemi, S. N.; Karimi-Sari, H. Adding Oral Pioglitazone to Standard Induction Chemotherapy of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia 2019, 19, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, S.; Safaroghli-azar, A.; Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi, A.; Salari, S.; Gharehbaghian, A.; hamidpour, M.; Bashash, D. Activation of PPARγ Intensified the Effects of Arsenic Trioxide in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia through the Suppression of PI3K/Akt Pathway: Proposing a Novel Anticancer Effect for Pioglitazone. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2020, 122, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glodkowska-Mrowka, E.; Manda-Handzlik, A.; Stelmaszczyk-Emmel, A.; Seferynska, I.; Stoklosa, T.; Przybylski, J.; Mrowka, P. PPARγ Ligands Increase Antileukemic Activity of Second- and Third-Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Blood Cancer Journal 2016, 6, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazi, M. S.; Mohammadi, S.; Yazdani, Y.; Sedighi, S.; Memarian, A.; Mehrdad Aghaei. Effects of Valproic Acid and Pioglitazone on Cell Cycle Progression and Proliferation of T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Jurkat Cells. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 2016, 19, 779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Philippe Rousselot; Prost, S. ; Guilhot, J.; Roy, L.; Etienne, G.; Legros, L.; Charbonnier, A.; Valérie Coiteux; Pascale Cony-Makhoul; Huguet, F.; Cayssials, E.; Jean-Michel Cayuela; Relouzat, F.; Delord, M.; Bruzzoni-Giovanelli, H.; Morisset, L.; Mahon, F.; Philippe Leboulch. Pioglitazone Together with Imatinib in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Proof of Concept Study. Cancer 2016, 123, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatriz, A.; Miranda, E. C.; Oliveira, M.; Bruna Rocha Vergílio; Pavan, C. ; Marcia Torresan Delamain; Gislaine Borba Duarte; Carmino Antonio Souza; De, E. V.; Pagnano, K. B. Pioglitazone Did Not Affect PPAR-Γ, STAT5, HIF2α and CITED2 Gene Expression in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients with Deep Molecular Response. Blood 2019, 134, 1637–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, C.; Rosato, V.; Buniato, D.; Zambon, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Corrao, G. Cancer Risk for Patients Using Thiazolidinediones for Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. The Oncologist 2013, 18, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Wu, P.; Gong, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, R.; Chen, H.; Sun, J. Association of Pioglitazone with Increased Risk of Prostate Cancer and Pancreatic Cancer: A Functional Network Study. Diabetes Therapy 2018, 9, 2229–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicitore, A.; Caraglia, M.; Gaudenzi, G.; Manfredi, G.; Amato, B.; Mari, D.; Persani, L.; Arra, C.; Vitale, G. Type I Interferon-Mediated Pathway Interacts with Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor-γ (PPAR-γ): At the Cross-Road of Pancreatic Cancer Cell Proliferation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2014, 1845, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, I.; Yamazaki, K.; Oyama, K.; Hayashi, H.; Tajima, H.; Kitagawa, H.; Sachio Fushida; Fujimura, T. ; Ohta, T. Pioglitazone Inhibits the Proliferation and Metastasis of Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Oncology Letters 2014, 8, 2709–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, H. PPARγ Potentiates Anticancer Effects of Gemcitabine on Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. International Journal of Oncology 2011, 40, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sisi, A. E.; Sokar, S. S.; Salem, T. A.; Abu, S. E. PPARγ-Dependent Anti-Tumor and Immunomodulatory Actions of Pioglitazone. Journal of Immunotoxicology 2014, 12, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saman Bahrambeigi; Morteza Molaparast; Sohrabi, F. ; Lachin Seifi; Faraji, A.; Fani, S.; Vahid Shafiei-Irannejad. Targeting PPAR Ligands as Possible Approaches for Metabolic Reprogramming of T Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunology Letters 2020, 220, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, H.; Zu, X. Association of Metformin Intake with Bladder Cancer Risk and Oncologic Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Medicine 2018, 97, 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Q.; Sun, J.X.; Xu, J.Z.; Qian, X.Y.; Hong, S.Y.; Xu, M.Y.; An, Y.; Xia, Q.D.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.G. Metformin Use on Incidence and Oncologic Outcomes of Bladder Cancer Patients with T2DM: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 865988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattum, van; Max, B. ; Oddens, J. R.; Theo; Wilmink, J. W.; Molenaar, R. J. The Effect of Metformin on Bladder Cancer Incidence and Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Bladder Cancer 2022, 8, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.H. Metformin May Reduce Bladder Cancer Risk in Taiwanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Acta Diabetologica 2014, 51, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process | Mechanism | Cancer Type |

| Proliferation & Growth | Increased expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 2 [43]. | Neuroblastoma |

| Increased activity of p-Akt and p-GSK-3β [43]. | ||

| Redifferentiation of tumor associated adipocytes [43]. | ||

| Inhibited cell growth via mTOR and STAT5 pathway tampering by retinoid X receptor agonists [44]. | Glioma | |

| Inhibited expression of estrogen receptor and aromatase via PGE2 and BRCA1 pathways [45]. | Breast cancer | |

| Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 pathway [46]. | ||

| Increased expression of p21 and MAPK activity [47]. | ||

| Inhibited CSC proliferation due to decreased STAT5 and HIF-2α levels [48]. | Chronic myeloid leukemia | |

| Downregulated MAPK, RAS, MYC gene expression and phosphorylation of MAPK pathway proteins [49]. | Non-small cell lung cancer | |

| Apoptosis | Downregulation of BCL2 and SCD1 [43]. | Leukemia |

| Reduced expression of MEK1 and ERK phosphorylation [50]. | ||

| Downregulation of STAT3 with ERK1/2, NF-κβ and p38MAPK molecules unaffected [51,52]. | ||

| Reduced expression of Survivin [51,52]. | ||

| Increased expression of TRAIL death ligand and apoptosis inducing factor [51,53]. | ||

| Downregulation of BCLXL/BCL2 in a PPARγ and caspase-independent manner [51]. | Prostate cancer, squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Induction of apoptosis in a caspase-dependent manner assisted by downregulation of c-FLIP, leading to BCL2 downregulation and instability [54]. | Caki cells | |

| Downregulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [55]. | Colorectal cancer | |

| Upregulation of cyclinB1, CDC2, p21 and alteration of BAX/BCL2 ratio [55]. | ||

| Angiogenesis [43,44,45,56,57,58] |

Reduced expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), COX-2. | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Inhibition of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) and urokinase plasminogen activator. | ||

| Apoptosis of endothelial cells. | ||

| Combined downregulation of COX-2 and VEGF when coupled with clofibric acid [44]. | Ovarian cancer | |

| Reduction of bFGF and VEGF initiated angiogenesis [59]. | Chick chorioallantoic membrane model | |

| Drug Sensitization | Reduced expression of metallothionein and endorphin connected to S273 phosphorylation [60]. | Pancreatic cancer |

| Enhanced type I Interferon activity due to inhibition of the STAT-3 pathway [58]. | ||

| Increased arsenic trioxide induced tumor toxicity through inhibition of the PI3K/AKT pathway [44]. | Leukemia | |

| Doxorubicin sensitization via modulation of P-glycoprotein [56]. | Osteosarcoma | |

| Reduced resistance to cisplatin [45]. | ||

| Cell Cycle Modification |

Increased cisplatin and oxiplatin efficacy. | Thyroid, lung, prostate, breast, kidney, esophageal and urothelial cancer |

| Inhibited EGFR/MDM2 mediated chemoresistance and PPARγ degradation [49]. | ||

| Downregulation of cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4). | ||

| Upregulation of CDK inhibitors including p19, p21, p27 and rho-related GTP binding protein. | ||

| Activation of Rb protein [50,60]. | ||

| Downregulation of cyclins D, cyclin E, CDK2, CDK4, proliferating nuclear antigen and retinoblastoma protein [58]. | Breast and colorectal cancer | |

| Differentiation | Induced adipogenesis [57]. | Melanoma |

| Immunomodulation | Increased β3 and α5 integrin expression [57]. | Colorectal cancer |

| Reduced PD-L1 levels due to autophagy [61]. | Lung, colorectal cancer | |

| Bioenergetics | Reduced pyruvate oxidation and glutathione levels. | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| ROS-induced stress mediated by HIF-1 and NF-κβ signaling. | ||

| Metastasis & Invasiveness | Downregulation of smad family member 3 (SMAD3), PDK1 and MCT-1. | Breast cancer |

| Upregulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). | ||

| Downregulation of NF-κβ, eIF2α, MMP9 and fibronectin [62]. | Lung cancer | |

| Upregulation of CXCR4, CXCR7, E-cadherin [46]. | ||

| Downregulation of TGF-β. | Glioma | |

| Reduced expression and invasiveness of β-cantenin [45]. | Breast cancer | |

| Downregulation of TGFβR1 and SMAD3 associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) [63]. | Non-small cell lung cancer | |

| Autophagy | Upregulation of HIF-1 and BNIP3 [50]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).