1. Introduction

The role of mental health and substance use disorders in advanced heart failure (Adv HF) patients undergoing surgical therapies such as durable mechanical circulatory support or cardiac transplantation is not well studied. Considering the physio-chemical interactions between excessive neurohormonal stimulation in the brain and depression it is imperative that HF itself can influence psychological effects in these patients [

1,

2]. Comorbidities such as depression has been found to exist in 21.5% of patients with HF. Depression in HF varies depending on whether surveys or interviews were used. Psychosocial factors related to depression predict functional status at 1 year in patients with reduced ejection fraction. The interaction between HF and depression is not really well understood. Many pathways may link heart failure and depression and these interactions can form a vicious cycle especially via activation of the neurohormonal pathways in the brain. In addition, when HF patients undergo surgical treatments with a different set of psychological stresses the negative effect may become accentuated [

2].

Additionally, psychological stress before, during, and after such life changing treatments such as implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) or cardiac transplantation (CT) have a large impact on the mental health of the patients and their care takers. Though mental health disorders can significantly worsen the health of HF patients, mental health issues still remain less perceived in this patient population. Increasing mental health disorders have been noted in the heart failure and solid organ transplant patient populations [

3,

4]. Multiple studies have shown that depression is prevalent among solid-organ transplant recipients. It has been identified in the current literature as an independent risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality post-transplant [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Depression and anxiety can compromise medication compliance therefore leading to poor outcomes in these populations [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. A study on lung transplant patients either on the wait list or post-transplant showed that psychological stress impacts medication compliance [

12].

There is a crucial need for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to managing heart failure patients throughout their surgical journey, from the pre-operative phase through post-operative recovery, ensuring not only physical rehabilitation but also addressing their cognitive and psychological well-being, which should continue beyond the immediate post-surgery period.

Both cardiac transplantation or VAD implantation are life changing treatments which require considerable adjustment. While physical aspects like diet, exercise, and medication adherence are crucial after a cardiac transplant or VAD implantation, it’s equally important to monitor and address potential mental health issues and pre-existing psychiatric disorders which can arise both pre- and peri-operatively and may require ongoing support throughout a patient’s life. This review seeks to address the gaps in knowledge in mental health and substance abuse disorders in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

An overview of the literature from 1965 till to date was carried out using Pubmed and Google scholar.

3. Results

3.1. Mental Health Disorders (MHD) in VAD Patients

3.1.1. Importance of MHD as a Comorbidity

The persistent shortage of donor organs with the advent of increasing mechanical circulatory support use in the treatment of advanced heart failure either as a bridge to transplant or as destination therapy for life the incidence and prevalence of mental health comorbidities need particular attention as it will impact compliance and quality of life.

Patients supported on VADs as destination therapy (DT), are highly susceptible to experiencing multiple psychological issues concomitantly, with the most prevalent being depression, anxiety disorders, adjustment and eating disorders, PTSD, agoraphobia, insomnia, substance dependence, short-term psychotic episodes, cognitive impairments, and mood disorders with or without organic causes.

The journey of a VAD patient can be segmented into phases that address different needs in different settings. It essentially involves four stages: candidate evaluation and initial assessment in the outpatient setting, pre-operative and post-operative care as an inpatient, immediate post-implant short-term follow-up care as an outpatient, and routine follow-up outpatient care. The last phase may also include palliative care. Phasic changes occur in the prevalence of depression and anxiety reaching maximum intensity immediately pre-implantation, decreasing fairly rapidly after successful implantation, and increasing in intensity depending on coping skills.

In a single-center analysis of VAD patients from the TriNetx database, significantly worse survival was noted in those with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Depression, Adjustment, Eating, and Alcohol-Use disorders as well as those who were diagnosed with Self-Harm [

27].

3.1.2. Strategies to Address MHD in VAD Patients

VAD patients evaluated for both as a bridge to transplant as well as DT should undergo extensive psychological screening and evaluation for pre-existing psychiatric diseases as this can cause an impediment to treatment and outcomes in the post-implantation phase due to serious compliance issues. Both caretakers and patients should be assessed for coping skills and compliance. One of the most important aspects of screening is to assess the patient’s true motivation to undergo treatment. Care should be taken to assess if the patient’s decision is driven by other psycho- social pressure. Patient should be assessed for negative emotions including fear but also on personal future ambitions and plans. Positive emotions drive better coping skills.

Intense education should be provided to the patient and family in the evaluation to make them aware of all positive and negative aspects of living with the device before the candidate is deemed eligible and the informed consent is signed. Additionally, medication compliance and the life-changing demands on the patient and family should be addressed.

Education should also be tailored for the different devices used and the different strategies such as bridge to transplant versus DT. Interestingly, different devices and lengths of support elicit different psychological stressors demanding different coping skills. Such education should highlight the risks versus benefits of using these treatment modalities. Patients with a prior history of mental health diseases should be specifically counseled by mental health professionals regarding specific complications, and restrictions resulting from the life-changing as well as life-saving treatments which will vary depending on the type of device and period of support. It is imperative to gauge the expectations of the patient, caregivers and family to effectively streamline post implant therapies. For patients who are implanted with a DT device, end-of-life issues need to be addressed early on. Palliative care should involve pre-, peri, post-implant, and post-discharge follow-ups as required [

17,

18].

In the perioperative phase, a different set of strategies may be needed to address a different set of challenges. Immediately post-VAD implant patients have a sudden set of challenges secondary to a change of lifestyle. The patients undergoing a bridge-to-transplant often feel better on VAD support and may be able to negate the feelings of inconvenience of a VAD in the hope of short-term support with heart transplant on the horizon in the future. However, those implanted as DT find different challenges The DT patients are usually at a later age in life and have to face the reality of living on a life-saving device for the rest of their lives. Hence these patients will need more attention from mental health professionals to help with coping skills. The younger and less sick advanced heart failure patients who get implanted as a bridge to recovery have a different set of challenges and live with a positive outlook hoping to shed the artificial heart and move on with life while having an innate fear of how their native heart would work after discontinuation of the artificial cardiac support. Hence it is imperative to cover patients whether they are implanted for the long or short term and have critical issues addressed by mental health providers at all times

A sudden realization of altered body morphism due to the presence of the device can exist in all patients. This is usually felt by the presence of the device within the body, anxiety about the new quality of life, lifestyle restrictions, scarring, infection, unexpected complications, device dependency, and anxiety about pump malfunction [

16]. The current day continuous flow pumps lack the heart rhythm which makes some patients very scared and distressed. Additional mental status changes and delirium for long periods may be a future psychological risk [

19] the maximum risk of developing psychological issues appears to be 1 month status post-surgery [

14]

The psychosocial challenges can affect outcomes in many ways and strict reinforcements of medication compliance become very important. Adherence to strict behavioral regimens anticoagulation monitoring and abstinence from substance abuse as well as nicotine and alcohol remain imperative. Hence interventions have to be implemented to prevent these especially in the context of a prior history of mental health illnesses.

Treatment of mental health disorders should be initiated in the preoperative period in addition to augmenting motivation improving cognitive function, and promoting healthy lifestyles. energy. Other behavioral issues include the perception of a lack of control and autonomy post-implantation [

20].

Neuropsychological interventions should be employed in the event of complications involving neurological deficits. This helps emotional coping with a focus on improving higher cognitive functions such as executive function. Combining psychotherapy may help. Interventions that focus on exercise can help improve emotional balance [

21]

Gender differences may be noted in emotional coping between men and women. In the patients emergently implanted attention has to be paid to supporting the combined mental trauma of the cardiac event in addition to the need for a device [

22].

3.2. Substance Use Disorders (SUD) in VAD Patients

3.2.1. Importance of SUD as a Comorbidity

Opioid use disorder has evolved into a global epidemic affecting at least five million Americans and has claimed over half a million lives in the United States due to overdose and significant morbidity secondary to addiction. An increase in post-operative prescriptions of opioids in the last two to three decades seems to coincide with these troubling trends. Opioid overuse and over prescription in the post-operative period possibly contribute significantly to this problem in surgical patients.

Limited data exists regarding prescription guidelines and outcomes associated with opioid use for post-surgical pain management in the VAD population. A single-center study showed an increased association between gastrointestinal bleeding/sepsis and opioid use in VAD patients [

23]. More studies are needed to assess opioid utilization in the LVAD population and consequent morbidity and mortality to control opioid use at index hospitalization [

24,

25]. In the current literature, opioid use does not seem to affect the survival of VAD patients. In a single-center study, multivariate analysis showed that different variables such as patient opioid experience, use of opioid medication at discharge, or the number of opioid refills did not correlate with worsening survival in VAD patients [

26]. In a retrospective analysis of the TriNetx database, the hazard ratio was 0.74 on survival analysis suggesting a protective effect possibly due to better pain control and consequent improved quality of life [

27]. Additionally, increased opioid use was observed in younger, non-diabetic patients with better renal function with less likelihood of sternotomy, shorter time on cardiothoracic bypass, and less likelihood of respiratory failure. These protective factors may partly explain the complex relationships between opioid use and survival. Other contributing factors may explain the observed relationships and would benefit from large multicenter studies. Current findings need further investigation.

In patients with ventricular assist devices, active tobacco use has been associated with complications such as pump thrombosis, hemolysis, drive-line infection, and increased readmissions. Patients with a history of smoking have increased VAD-related complications. In a retrospective study using the TriNetX database a minimally significant survival benefit was noted with nicotine and opioid dependence [

27]. Smoking has been shown to increase the risk of stroke in patients supported on LVAD [

28].

3.2.2. Strategies to Address SUDs in VAD Patients

Discharge pain management should be tailored to patient needs with non-opioids for regular use in combination with opioids only for more intense pain management, especially for opioid-exposed patients. Pain management specialists should be involved in post-discharge pain control strategies. Non-opioids should always be the first choice. Such strategies may help reduce the epidemic rise of opioid dependency. Pain medicine should always be consulted in the outpatient setting to manage these patients in the long term [

26]. In a single-center study, the ERAS protocol showed a 5-fold lower opioid use versus a standard approach. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols have been suggested to reduce opioid use [

29].

Effective tobacco cessation methods are important for optimizing outcomes following VAD implantation. Tobacco use is currently not an absolute contraindication for destination therapy (DT) patients. More investigations are needed to implement successful tobacco cessation programs for patients supported on VADs [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Smoking cessation strategies are rarely tailored to individual patient needs. This is an integral component of successful abstinence which is currently lacking. Personalized coping strategies, supportive management, and reducing social triggers. Future studies should assess the effects of individualized neurocognitive therapy on cessation outcomes in this population. Compared to pharmacological therapies behavioral and stress reduction therapies can be more effective.

Pharmacologic and nicotine replacement therapies were much more commonly utilized than the alternative therapies. However, only about half of the centers utilizing these options felt they were effective. Interestingly, cognitive therapy and stress reduction therapy, which were the least common treatments at respondent centers, both were effective.

Having an incentive can play an important role in smoking cessation. Bridge-to-transplant patients were keener on quitting smoking than DT patients. Current guidelines do not mandate smoking cessation in DT VAD patients [

11]. DT patients who continue smoking have worse but still, the final decision to quit tobacco use or continue is ultimately left to the patient. About 30% of VAD centers support the concept that smoking should be a contraindication to DT implantation [

31,

33].

3.1. MHD in Patients on the Waitlist and Post-Transplantation

3.3.1. Importance of MHD as a Comorbidity

Cardiac transplant waitlist candidates are cared for as per the guidelines for their medical needs but there are no defined pathways to care for mental health assessment. Hence, psychological and psychosocial factors may go unaddressed. This is an important aspect to address as they impact post-transplant outcomes due to behavioral and medical non-compliance [

34,

35]. A TriNetx database retrospective study revealed that cardiac transplant waitlist patients showed an increase in the incidence of anxiety, depression, panic attacks, adjustment disorder, alcohol use disorder, and eating disorders. However, only adjustment disorder and depression were increased in post-transplant patients [

27]. These results indicate that the patients on the waitlist undergo a period of uncertainty and stress. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment can be achieved only if they have access to mental health care. Mental health care on the transplant waitlist may improve candidacy and survival. These findings in the existing literature may demonstrate inequality between those with better social support and increased access to care. More studies are required in this area.

It is not surprising that cardiac transplantation increases the risk of depression, possibly secondary to challenges in coping with lifestyle changes and complications. It has been shown that anxiety and depression are lower in patients undergoing cardiac transplantation versus those undergoing other cardiac surgeries [

36].

3.3.2. Strategies to Address MHD Patients in the Waitlist and Post-Transplantation

Psychosocial assessments should include socioeconomic factors and mental health. Using community-based mental health counselors should be useful in providing waitlisted heart transplant candidates with follow-up mental health assessments in determining their ongoing suitability for transplantation.

Mental health professionals and social workers must be available for this population to ensure continued successful outcomes. Current literature on transplant social worker-to-patient and transplant nurse coordinator-to-patient ratios needs to be considered for appropriate staffing.

Additionally, there is no definitive literature on mental health care needs for patients awaiting transplants. More studies are needed in this area to understand the barriers in the waitlist population. It is therefore important to scale up the teams at transplant programs to further assess mental health needs and connect with the evolving needs of the listed candidates [

37].

3.4. SUD in Patients on the Waitlist and Post-Transplantation

3.4.1. Importance of SUD as a Comorbidity

In a single-center study of waitlist patients nicotine dependence appears to be a major substance use disorder. Although many patients recovered from nicotine addiction, approximately 12% of patients did not discontinue smoking at the time of evaluation. Prior studies show substance abuse in the preoperative phase is a significant risk factor for post-transplantation outcomes. A history of alcohol abuse was found in 9.6% of patients. History of caffeine intoxication, as defined by DSM-IV criteria, was found to be 2.4% in this population. This is an important risk factor because of documented cardiotoxicity due to caffeine abuse [

38]. In a retrospective analysis of patients in the TriNetx database opioid use had significantly increased in the transplant population as compared to heart failure patients who did not undergo transplant surgery [

27]. This observation suggests that opioid use for controlling surgical pain may predispose patients to opioid dependence post-transplant. The waitlist period can extend from days to weeks to years. In some prior studies psychiatric illness either primary or secondary to substance use may negatively affect transplant outcomes through poor medical and behavioral non-compliance, self-harm, and consequent suboptimal social support and coping skills[

39].

3.4.2. Strategies to Address SUDs in Patients on the Waitlist and Post-Transplantation

The transplantation wait list should be assessed for substance use disorders stringently. The identification of current and prior substance use disorders is critical in the preoperative evaluation of candidates for heart transplantation. Patients who continue to smoke and use substances demonstrate explicit noncompliance with lifestyle modification. Using specialists in substance-related disorders may decrease the risk of unsuccessful outcomes related to patients’ unhealthy behaviors. A prior diagnosis of SUDs should alert providers to extensively assess the stability of remission. After transplantation, when functional status improves could prompt a relapse in this population. An evaluation of both prior and current SUDs before determining the candidacy for transplant should be followed by multidisciplinary lifestyle modification programs and elaborate strategies to prevent relapse[

38]. Newer studies are required at this time.

4. Discussion

4.1. Identification of Knowledge Gaps

This review helps to understand areas that need investigation to mitigate knowledge gaps. Prospective studies are lacking in this area to identify MHDs and SUDs in advanced heart failure patients undergoing surgical approaches such as mechanical circulatory support or cardiac transplantation. A consensus document is lacking for guidance on the evaluation and treatment of MHDs and SUDs in the VAD and transplant population. Currently, there are no risk prediction models to identify patients at high risk for relapse of MHDs and SUDs post-transplantation or after VAD implant. Knowledge of risk factors that may predispose advanced heart failure patients to MHD or SUDs is lacking at present. This is important to know for better risk stratification of patients being evaluated for VAD or Cardiac transplant.

4.2. Future Directions

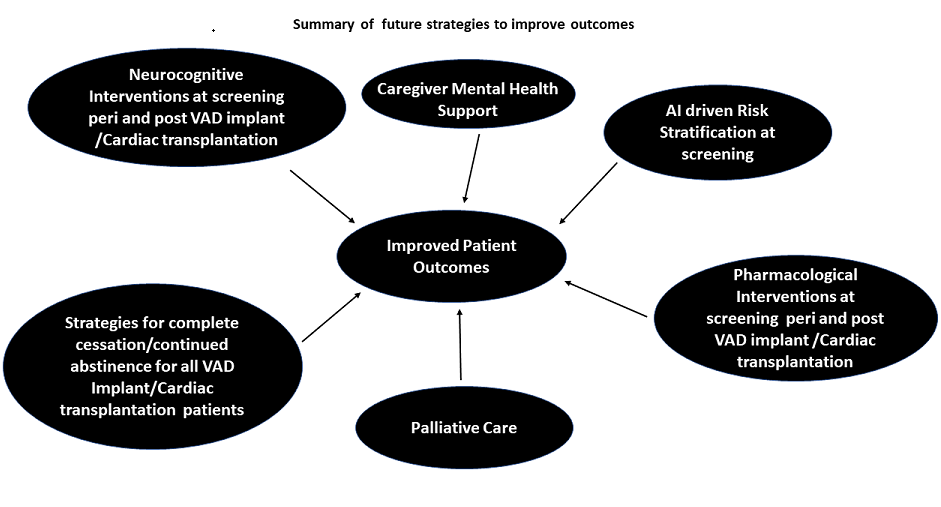

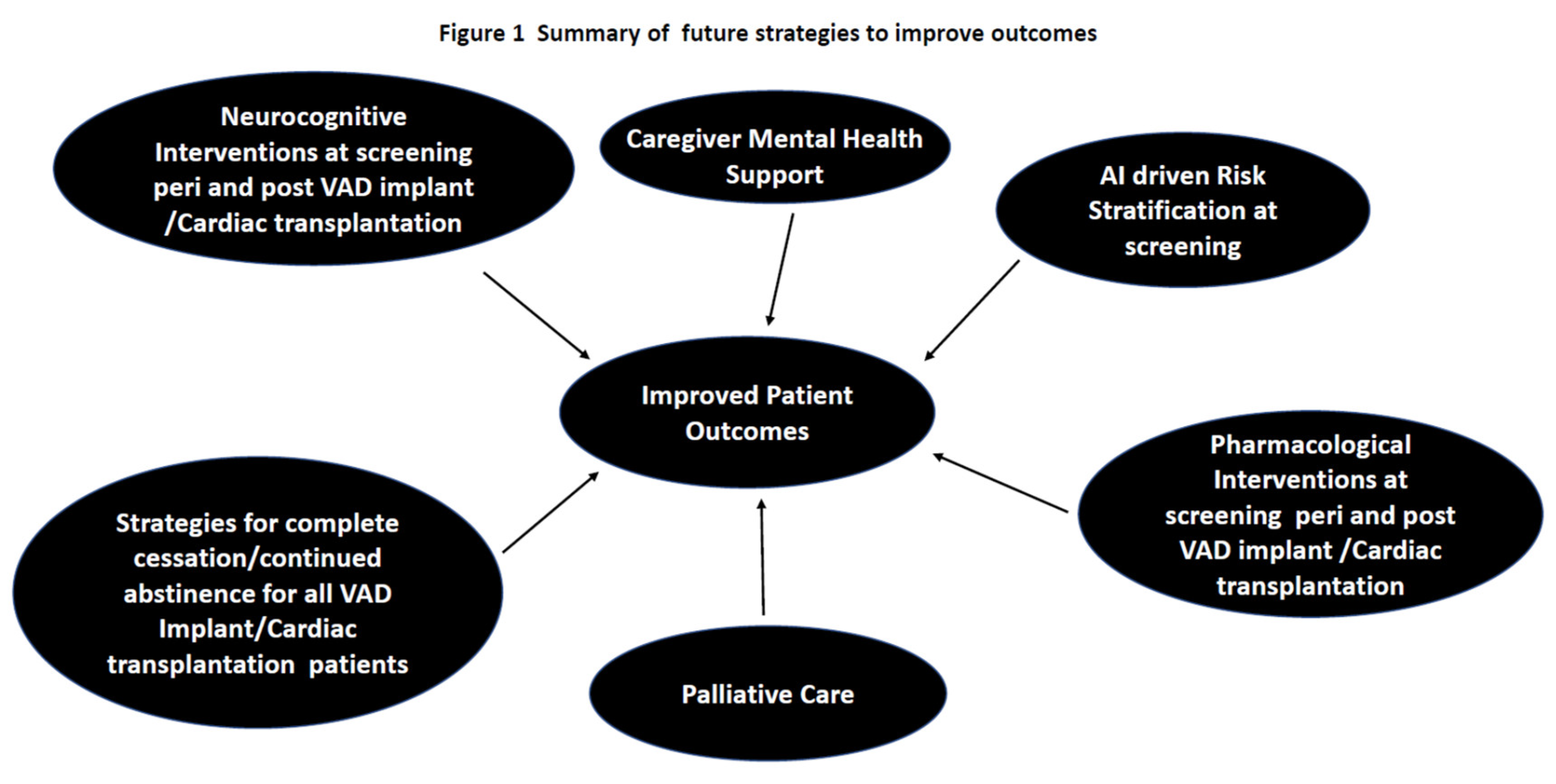

There is a need to expand educational programs for psychosocial support of patients undergoing VAD implant as well as those waiting on the cardiac transplant list and those who are post-transplantation. The support programs should be extended to cover the patient, caregiver, and family members involved in the care of the patient. Extensive psychological screening and evaluation for pre-existing psychiatric diseases should be done in all advanced heart failure patients undergoing evaluation for VAD as a bridge to transplant, DT, and those being evaluated for cardiac transplantation. Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven technologies should be used to develop objective questionnaires to augment the psycho-social assessment of patients undergoing VAD implantation or cardiac transplantation.

AI-driven methods to identify risk factors can be used to utilize machine learning algorithms to analyze large datasets, to assess patterns that predispose to risk. Such an approach can help determine risk to manage complications proactively. The patient data in the screening, perioperative and long-term settings should be merged from different centers to form a large database and machine learning should be used to identify new risk factors. The risk factors should then be pooled to generate a predictive model. Predictive analytics will assess future risk. Some of the important assessments include detection of anomalous behavior, pattern recognition, modeling for prediction, and real-time monitoring across other data sources including financial records, data from operations management, and transactional information.

With advances in technological advances there is increased utilization of surgical therapies. Chronic immunosuppression is critical for transplant patients but can also induce psychological complication especially in the setting of steroid therapy. AI-driven and machine learning risk prediction models have improved in their ability to predict post-operative complications but remain limited in clinical settings due to missing data and class imbalances. AI models derived from a Bayesian Network as well as those derived from neural networks, use hemodynamic and clinical and image acquisition data to derive novel risk factors. Though AI driven technologies can have ethical, logistic, and legal challenges as well as algorithm bias it may enhance the likelihood of discovering novel risk factors which pave the way for better risk prediction models with higher discriminatory power.

Effective neurocognitive and behavioral therapies should be developed for continued cessation of substance use. Guidelines to mandate complete abstinence from tobacco use in DT VAD patients should be instituted as tobacco use initiates complications and compromises the quality of life. AI-driven technologies should be used to derive risk factors for MHDs and SUDs in advanced heart failure patients undergoing evaluation for VAD implant or transplantation. Risk prediction models with robust discriminatory power should be used to identify patients who have a predisposition to MHD /SUD relapses post-transplantation.

Figure 1 summarizes the possible future directions to be pursued to improve patient outcomes in this population.

5. Conclusions

The literature on the impact of psychosocial stresses on advanced heart failure patients undergoing cardiac transplantation or VAD implantation is suboptimal at present. At present there is a paucity of granular guidelines to address psychosocial evaluation in this population. The current literature does not help to distinguish any differences mechanical support would have on the psychology of these patients as compared to cardiac transplantation. Knowledge gaps exist in risk assessment and risk stratification of patients with a prior history of MHD/SUD who are predisposed to relapses. The existing system of psychosocial assessment may not be robust due to a lack of adequate staffing by mental health professionals and social workers. Prospective studies are currently lacking in identifying the impact of psychosocial stresses on the quality of life of these patients. Longitudinal studies are needed in the future to identify and address complications that arise due to psychosocial stress factors in the VAD and cardiac transplant populations because of medication and behavioral non-compliance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N. D.D., B.M.; Writing, editing, N.N, C.G., D.D. and B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was not funded.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as this is a review only.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable as this is a review only.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented here are analyzed from the public databases.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts.

References

- Celano CM, Villegas AC, Albanese AM, Gaggin HK, Huffman JC. Depression and Anxiety in Heart Failure: A Review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2018 ;26(4):175-184. [CrossRef]

- Nair N, Farmer C, Gongora E, Dehmer GJ. Commonality between depression and heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2012 ;109(5):768-72. [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.P., Nguyen K.M., Tran H.T., Hoang S.V. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Study in Vietnam. Cureus. 2023;15:e51098. [CrossRef]

- Corbett, C., Armstrong M.J., Parker R., Webb K., Neuberger J.M. Mental health disorders and solid-organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013;96:593–600. [CrossRef]

- Alyaydin, E., Sindermann J.R., Köppe J., Gerss J., Dröge P., Ruhnke T., Günster C., Reinecke H., Feld J. Depression and Anxiety in Heart Transplant Recipients: Prevalence and Impact on Post-Transplant Outcomes. J. Pers. Med. 2023;13:844. [CrossRef]

- Dew, M.A., Rosenberger E.M., Myaskovsky L., DiMartini A.F., DeVito Dabbs A.J., Posluszny D.M., Steel J., Switzer G.E., Shellmer D.A., Greenhouse J.B. Depression and Anxiety as Risk Factors for Morbidity and Mortality After Organ Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transplantation. 2015;100:988–1003. [CrossRef]

- Delibasic, M., Mohamedali B., Dobrilovic N., Raman J. Pre-transplant depression as a predictor of adherence and morbidities after orthotopic heart transplantation. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017;12:62. [CrossRef]

- Tigges-Limmer, K., Brocks Y., Winkler Y., Stock Gissendanner S., Morshuis M., Gummert J.F. Mental health interventions during ventricular assist device therapy: A scoping review. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018;27:958–964. [CrossRef]

- Weerahandi, H., Goldstein N., Gelfman L.P., Jorde U., Kirkpatrick J.N., Meyerson E., Marble J., Naka Y., Pinney S., Slaughter M.S., et al. The Relationship Between Psychological Symptoms and Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;54:870–876.e1. [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, J.T., Lyons K.S., Mudd J.O., Gelow J.M., Chien C.V., Hiatt S.O., Grady K.L., Lee C.S. Quality of Life, Depression, and Anxiety in Ventricular Assist Device Therapy: Longitudinal Outcomes for Patients and Family Caregivers. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017;32:455–463. [CrossRef]

- Mehra, M.R., Canter C.E., Hannan M.M., Semigran M.J., Uber P.A., Baran D.A., Danziger-Isakov L., Kirklin J.K., Kirk R., Kushwaha S.S., et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: A 10-year update. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:1–23. [CrossRef]

- Wessels-Bakker MJ, van de Graaf EA, Kwakkel-van Erp JM, Heijerman HG, Cahn W, Schappin R. The relation between psychological distress and medication adherence in lung transplant candidates and recipients: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2022 ;31:716-725. Epub 2021 Jul 2. Erratum in: J Clin Nurs. 2022 Oct;31(19-20):2981. 10.1111/jocn.16481. [CrossRef]

- Abshire M, Prichard R, Cajita M, DiGiacomo M, Dennison Himmelfarb C. Adaptation and coping in patients living with an LVAD: A metasynthesis. Heart Lung. 2016;45:397-405. [CrossRef]

- Brouwers C, Denollet J, de Jonge N, Caliskan K, Kealy J, Pedersen SS. Patient-reported outcomes in left ventricular assist device therapy: a systematic review and recommendations for clinical research and practice. Circ Heart Fail. 2011 ;4:714-23. [CrossRef]

- Weerahandi H, Goldstein N, Gelfman LP, Jorde U, Kirkpatrick JN, Meyerson E, Marble J, Naka Y, Pinney S, Slaughter MS, Bagiella E, Ascheim DD. The Relationship Between Psychological Symptoms and Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017 ;54:870-876.e1. [CrossRef]

- Petrucci RJ, Benish LA, Carrow BL, Prato L, Hankins SR, Eisen HJ, Entwistle JW. Ethical considerations for ventricular assist device support: a 10-point model. ASAIO J. 2011 ;57:268-73. [CrossRef]

- Petty M, Bauman L. Psychosocial issues in ventricular assist device implantation and management. J Thorac Dis. 2015 ;7:2181-7. [CrossRef]

- Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, Birks E, Lietz K, Moore SA, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 ;32:157-87. [CrossRef]

- Ladwig KH, Lederbogen F, Albus C, Angermann C, Borggrefe M, Fischer D, et al. Position paper on the importance of psychosocial factors in cardiology: Update 2013. Ger Med Sci. 2014 ;12:Doc09. [CrossRef]

- Hallas C, Banner NR, Wray J. A qualitative study of the psychological experience of patients during and after mechanical cardiac support. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009 ;24:31-9. [CrossRef]

- Kugler C, Malehsa D, Tegtbur U, Guetzlaff E, Meyer AL, Bara C, et al. Health-related quality of life and exercise tolerance in recipients of heart transplants and left ventricular assist devices: a prospective, comparative study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:204-10. [CrossRef]

- Tigges-Limmer, K., et al. “Psychosocial aspects in the diagnostics and treatment of LVAD patients: Living on device as borderline experiences according to Jaspers.” Zeitschrift Für Herz-, Thorax-Und Gefäßchirurgie 32 (2018): 141-149.

- Combs PS, Imamura T, Siddiqi U, Mirzai S, Spiller R, Stonebraker C, Opioid use and morbidities during left ventricular assist device support. Int Heart J. 2020 ;61(3):547–552. 30 May. [CrossRef]

- Manchikanti L, Helm 2nd S, Fellows B, Janata JW, Pampati V, Grider JS, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES9–E38.

- Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65 (50-51):1445–1452. [CrossRef]

- Schettle S, Shahin Y, Dunlay S, Daly R, Glasgow A, Habermann E, et al. Opioid usage after left ventricular assist device implantation: A single center retrospective analysis. Heart Lung. 2023 May-Jun;59:82-87. [CrossRef]

- Grzyb C, Du D, Mahesh B, Nair N. Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders in Transplant Waitlist, VAD, and Heart Transplant Patients: A TriNetX Database Analysis. J Clin Med. 2024 ;13(11):3151. [CrossRef]

- Sherazi S, Goldenberg I, McNitt S, Kutyifa V, Gosev I, Wood K, et al.. Smoking and the Risk of Stroke in Patients with a Left Ventricular Assist device. ASAIO J. 2021;67(11):1217-1221. [CrossRef]

- Lindenmuth DM, Chase K, Cheyne C, Wyrobek J, Bjelic M, Ayers B et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery in patients implanted with left ventricular assist device. J Card Fail. 2021;27(11):1195–1202. [CrossRef]

- Patel V, Nassif M, Raymer D, et al. Smoking is associated with pump thrombosis after left ventricular assist device implantation. S: J Card Fail 2015; 21, 2015.

- Combs P, Imamura T, Siddiqi U, et al. Effect of tobacco smoking on outcomes after left ventricular assist device implantation. Artif Organs 2020; 44: 693–699.

- Youmans QR, Anderson A, Ghafourian K, et al. The association of smoking history and outcomes following left ventricular assist device implantation. J Card Fail 2018; 24: S122–S123.

- Bhattacharya A, Vilardaga R, Kientz JA, et al. Lessons from practice: designing tools to facilitate individualized support for quitting smoking. 3: ACM Trans Comput Hum Interact 2017, 2017.

- Dew, M. A., DiMartini, A. F., Dobbels, F., Grady, K. L., Jowsey-Gregoire, S. G., Kaan, A et al. (2018). The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW recommendations for the psychosocial evaluation of adult cardiothoracic transplant candidates and candidates for long-term mechanical circulatory support. Psychosomatics, 59(5), 415-440.

- Bui, Q. M., Allen, L. A., LeMond, L., Brambatti, M., & Adler, E. Psychosocial evaluation of candidates for heart transplant and ventricular assist devices: beyond the current consensus. Circulation: Heart Failure, 2019 12(7), e006058.

- Heilmann C, Kaps J, Hartmann A, Zeh W, Anjarwalla AL, Beyersdorf F, Siepe M, Joos A. Mental health status of patients with mechanical aortic valves, with ventricular assist devices and after heart transplantation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016 ;23(2):321-5. [CrossRef]

- Kleet AC, Regan M, Siceloff BA, Alvarez C, Farr M. Psychosocial readiness assessment for heart transplant candidates. Heart Lung. 2024 ;67:19-25. [CrossRef]

- Sirri L, Potena L, Masetti M, Tossani E, Grigioni F, Magelli C, Branzi A, Grandi S. Prevalence of substance-related disorders in heart transplantation candidates. Transplant Proc. 2007 ;39(6):1970-2. [CrossRef]

- Kop, WJ. Role of psychological factors in the clinical course of heart transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010 ;29(3):257-60. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).