1. Introduction

Neuralink’s ’Telepathy’ is a new intrusive Brain-Computer Interaction (BCI) device that places 1024 electrodes in the motor cortex. Unlike non-intrusive EEG technologies, intrusive methods are able to fully penetrate the brain for deep coverage. This, combined with Telepathy’s high electrode count compared to the standard 32 or 64 electrodes for non-intrusive EEG, provides a quality of data unrivalled by non-intrusive means. Furthermore, a vast quantity of data can be gathered by the device due to being embedded in a user, unlike EEG devices that would typically be worn for no longer than a day, or to MRI machines that people would be in for only a couple of hours. The company has also developed a robot to implant their device, making it more scalable and accessible as it reduces the need for human expertise during the surgery. It is for these reasons that we believe Neuralink’s technology could be the beginning of large-scale and high-quality data capital collection for BCI applications.

That being said, this technology is still in its infancy. At the time of writing, only 2 patients have had Telepathy implanted with varying success. Some of the 64 threads came loose with the first patient, although the user was still able to control a cursor with their thoughts. Questions still remain as to the safety of this technology, as well as its long-term durability. There is also the cost of the device to consider, as well as the fears people have about having a chip implanted in their brain, which are further barriers to the wide-spread adoption of this device. For this reason, we focus on non-intrusive EEG datasets in this paper, which contribute to the majority of existing data capital for BCI applications due to their price and ease-of-use compared to other brain-imaging techniques. It is also unclear if Neuralink, due to their nature as a private company, will release the data capital they collect to the broader academic community.

The rapid development of Deep Learning (DL) embraces the prevalence of Internet technology. The increasing internet access and availability accumulate large-scale and diverse data which stimulates the demand for efficient computing and data storage. The past two decades have shown a significant trend from theoretical studies toward versatile applications. New commercial needs encounter technical challenges that in turn motivate the establishment of new theoretical foundations, such as multi-modal [

1], multi-task [

2], interpretable [

3], causality [

4] and AI-Generated Contents (AIGC) [

5,

6]. Putting DL technology in the context of the Industrial Landscape helps to understand the closed loop of theory-application-need and identify future trends, limitations and challenges.

On the path toward Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), models and data are the two fundamental pillars of AI development. The origins of AI models lie in logic formalisation [

7]. Alan Turing, building on this foundation, introduced the Turing machine and the conceptualisation of AI from a deductive perspective. Deductive or rule-based symbolic systems [

8] are characterised by their pursuit of rigour and precision but often sacrifice flexibility and generalisation capabilities. In contrast, inductive methods have evolved to follow a data-driven approach, deriving rules and models from patterns in observed data. Current deep learning (DL) models are primarily grounded in the inductive paradigm, processing empirical perception signals such as vision, natural language, and audio [

9]. However, while these models excel at pattern recognition and representation, they are inherently limited to interpreting conscious levels of data, as conceptualised in cognitive theory [

10]. According to this theory, an agent’s cognition spans four levels: unconsciousness, consciousness, awareness, and meta-awareness. Traditional DL models predominantly operate at the level of behavioural data, reflecting perception and consciousness. Their goal is to align human attention signals (labels) with input data, such as semantic attributes. Despite their progress, supervised learning paradigms, which have dominated AI research for the past two decades, suffer from several limitations. These include issues such as subjective biases [

11], vulnerability to adversarial attacks and data poisoning [

12], the burden of data annotation, and significant ethical concerns [

13]. These challenges highlight the constraints of existing methods and the need for more robust approaches to achieve AGI. The emergence of self-supervised learning and advances in parallel computing have prompted industrial efforts to pursue a top-down technological approach. This involves leveraging large-scale multi-modal interactive data to train powerful DL models that aim to achieve meta-awareness — a higher cognitive representation incorporating knowledge graphs and causal inference [

14]. By addressing the divergence in individual awareness and improving moral generalisation, these models offer a pathway to mitigate bias and ensure more inclusive and fair outcomes. However, this approach relies on the assumption that data collection systems can comprehensively capture diverse users, thereby addressing the challenges of neurodiversity [

15].

Emerging BCI technologies have brought new opportunities and challenges which push the AI and deep learning community to the next level. One aim of this technology is to explain fundamental brain mechanisms beyond perception and consciousness. For example, Rapid Serial Visual Presentation (RSVP) displays users with sequential images at high speed (e.g. 10 images per second). In face recognition tasks, users are given a well-known target face to find, e.g. Einstein, before being displayed a high-speed sequence of faces. A promising result is that the P300 signal, triggered when a person recognises a face, can be detected from the BCI signal when human participants are not aware that the face has been displayed. This shows that signals measured by BCI devices can indeed detect and analyse unconscious level information and suggests that BCI technology could lead AI to a new era by exploring the internal behaviour of brain activities beyond existing cognitive and conscious levels.

In this context, Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems represent a critical breakthrough. Unlike traditional methods that primarily rely on behavioural and conscious data, BCI systems have the potential to tap into unconscious levels of cognition, providing a fundamentally new layer of supervision for AI. By integrating neural signals directly from the brain, BCI can reduce the inherent subjectivity of supervised learning and provide richer, more diverse data inputs. This capability not only mitigates bias and enhances fairness but also paves the way for a more comprehensive and accurate alignment of AI systems with human cognition, thereby playing an indispensable role in the pursuit of AGI. However, the key barrier between BCI and contemporary deep learning research is data foundation. The data-hungry nature of deep models requires vast quantities of training data that can only be acquired through large-scale deployment. The polarised situation is that intrusive or fMRI-based data collection can provide high-resolution and reliable results, but are limited by cost and usability. However, the low-cost, lightweight, and commercialised devices, e.g. EEG, ECG, and EMG, are still limited in performance. In this paper, we investigate this problem through the lens of the Industrial Landscape [

16], which provides a new perspective on data capital. This allows us to understand the progress and to predict the trend of deep neural network development in BCI domains. The contribution of this paper is threefold:

First, we use the industrial landscape conceptualisation framework to conduct a systematic literature review. We summarise both established and emerging DBCI data capitals which help understand the progress of each identified core technical milestone of DBCI.

Second, the motivation of this article aims to put the development of BCI models into the context of the industrial landscape framework. We identify key barriers preventing the development of large DBCI models in terms of devices, data, and applications.

Third, we point those unaddressed technical challenges towards cutting-edge zero-shot learning techniques. Our findings establish a technical road-map through inter-sample, inter-person, inter-device, inter-domain and inter-task transfer paradigms, multi-modal visual-semantic neural signal models, and data synthesis and signal processing for higher SNR and scalable DBCI device adaption.

The organisation of this paper is as follows. In

Section 2, we systematically introduce the research background, the conceptualisation of the industrial landscape, and the current state of DBCI research. In

Section 3, we outline our survey methodology and the data we’re going to collect.

Section 4 discusses the survey results of existing BCI datasets and suggests how the emerging zero-shot neural decoding technique can overcome the barriers identified in the survey. We finalise our discussion and summarise the main findings in the last section.

2. Research Background

In this section, we introduce the research background of DBCI to put our review into the context of the Industrial Landscape (IL) [

16]. The IL provides a framework to analyse the industrial trend of both existing digital technologies and AI. Our contribution focuses on making a mapping for DBCI development under the IL framework so as to understand and predict the progress in parallel with other AI and digital technologies.

The first return of our research on google scholar gives over 28,000 results based on the keywords of brain-computer/machine interface, EEG and review/survey. From the results, we select 677 papers ranging from 1986 to 2023 as our entry points. Through a narrative review approach, we extract key milestone papers to provide an overview of current BCI research as follows.

Early work of BCI can be traced up to 1924 [

17] when the first-ever electroencephalogram signal was recorded by Hans Berger. A Bio-Neuro [

18] feedback began in the late 1950s. Biofeedback refers to all physiological signals, e.g. blood pressure, heart rate etc. whereas Neuro feedback refers to brain signals only. The first seminal work that provided both a theoretical and technical review of BCI was given in 1973 [

19]. Initial research focuses on Controlling Assistive Devices. Operant (Instrumental) conditioning refers to autonomous functions, e.g. blood pressure and heart rate which can be manipulated by operant conditions. In 1960 [

20,

21], Neil Miller demonstrated the first trial to disrupt the motor system of rats. The experiment extended to blood pressure, urine production, and gut control in [

22]. Human learning, in contrast, takes the cognitive dimension into account. Controlling devices with BCI, end-users need to focus their attention throughout the tasks, which is cognitively demanding.

One of the primary applications of BCI lies in the neuro-disorder domain. In particular, Locked-In Syndrome (LIS), which typically follows a stroke in the basilar artery of the brainstem, is characterised by the retention of vertical eye movements (e.g., looking up and down) [

23,

24]. LIS can also result from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), which leads to the loss of movement or complete motor paralysis. Both LIS and ALS are key target populations for restoring lost functionality through BCI. Compared to traditional voluntary assistive technologies, BCI offers four main advantages. First, Slow Cortical Potentials (SCP) provide the basis for long-term training, allowing individuals to communicate messages in the absence of peripheral muscular movement. Second, involuntary eye movements associated with LIS present a significant challenge for other assistive technologies, which BCI can bypass. Third, depression caused by LIS often makes it difficult for caregivers to interpret eye movements or spelling codes, which limits communication. Fourth, BCI eliminates the need for questionnaire-based assessments, providing a more direct and efficient interface. A more challenging scenario involves Complete Locked-In Syndrome (CLIS) [

25], in which the loss of behavioural output [

26] leads to "thought paralysis." This state, often resembling a vegetative state, poses limitations to operant learning approaches. Despite these challenges, contemporary BCI applications have embraced advancements brought by the AIGC era. For instance, Brain Painting replaces the traditional P300 matrix with icons representing painting tools, which are controlled by a cursor. This technology has enabled ALS patients to create art independently, without requiring researcher supervision [

27,

28]. Following painting sessions, satisfaction, joy, and frustration are evaluated by the BCI team, and favourable results have consistently been observed.

Neurophysiology has established key paradigms for BCI signal acquisition, such as Slow Cortical Potentials (SCP) and P300, which are widely applied in conditions like epilepsy and ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). Techniques like voluntary control of Alpha Activity, Sensorimotor Rhythms (SMR), and

-rhythm have been utilised in psychological therapy, behavioural studies, and medicine since the 1950s. Event-Related Potentials (ERP), SMR, SCP, and P300 (a positive potential occurring 300 ms after a stimulus) are frequently implemented with stimuli approaches like the oddball paradigm. For example, a 6x6 letter matrix [

29] enables letter selection, while N400 (a negative potential 400 ms after stimulus) is used for face recognition tasks. Operant learning is commonly employed to increase SMR activity (8–15 Hz), which reflects Event-Related Desynchronisation (ERD). ERD was introduced for cursor control in 1991 and later expanded to motor imagery, though it requires users to learn to regulate their brain responses. The S1-S2 paradigm (S1: warning stimulus, S2: imperative stimulus requiring a motor response) is also used, where SCP measures slow EEG shifts, such as Contingent Negative Variation (CNV). For instance, a negative shift 800 ms before finger movement can be observed. SCP shifts are also associated with large negative DC shifts during epileptic seizures, and voluntary SCP modulation may help prevent them. These methods were first implemented for locked-in patients in 1999 [

30] and remain foundational for smooth BCI control.

There are several traditional barriers preventing BCI to be widely applied. The first is the Signal-Noise Rate (SNR). SNR reflect the strength of the signal of interest in relation to artefacts like breathing and muscular movement [

31]. These noist artifacts remain a fundamental challenge today. Second, BCI training is required for users, decreasing accessibility [

32]. In 2010, Usability and User-Centred Design (UCD) [

33] set the ISO 9241-210 as the usability standard. This norm requires BCI-controlled applications to be evaluated by user experience in terms of 1)

effectiveness which considers the accuracy and completeness users can achieve; 2)

satisfaction which measures comfort and acceptability while using the device; and 3)

usability measurement. Information Transfer Rate (ITR) is also a key parameter to measure BCI accessibility. From the early work of 2 mins per letter [

30], P300-based BCI progressed to 10 letters per min in [

34]. However, it is still not suitable for independent home use. Device design is also an important factor. The trend in BCI technology development is moving towards lightweight, cost-effective solutions, ranging from compact RRG amplifiers integrated into caps [

35], to artefact rejection techniques for smartphone applications during walking [

36], and behind-the-ear designs [

37]. The literature review highlights the essential need for advancements in Machine Learning, Communication, and Interaction technologies [

38]. The key objectives are to:

Reduce the training cost for both users and models

Robust filters for improved SNR

Transferable and generalised BCI without prior calibration

This presents a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma. On one hand, machine learning, particularly deep learning, requires large-scale data to achieve reliable transferability and generalisation. On the other hand, transferability and generalisation are essential features that must be established before a BCI device can be widely adopted. For instance, no long-term studies involving locked-in patients have been conducted using machine learning. Historically, neuro-feedback studies required significant time investments, such as 288 hours per user [

39], or in 1977, 2.5 years of SMR data collected over 200 sessions. These efforts represent a foundational investment in data capital, which we consider critical for driving progress in models, devices, paradigms, and accessibility. We will further explore how data capital underpins these aspects in the context of the Industrial Landscape framework.

2.1. Industrial Landscape

Industrial Landscape (IL) generally refers to the physical and visual characteristics of areas where industrial activities take place, such as factories, mills, refineries, and other industrial facilities. It can also refer to the broader socio-economic and cultural impacts of industrialisation on the surrounding environment and communities, including changes to land use, infrastructure, and the built environment. Industrial landscapes can vary widely in appearance and character depending on the type of industry, the location, and the historical context, and may include features such as smokestacks, silos, pipelines, and rail yards.

The fast growth of internet companies and new technologies has resulted in a stark contrast to the traditional IL conceptualisation. The traditional labour theory of Karl Marx conceptualises economic development with key components of labour, value, property and production relationship. David Harvey [

40] provides a modern interpretation with a significant influence on academic and political debates around the world. The work on urbanisation and the political economy of cities has been particularly influential and has been a vocal critic of the neoliberal policies that have shaped urban development in many parts of the world. The work has often addressed the intersections between political economy, social inequality, and environmental degradation. In this paper, we introduce the recent work which develops an industrial landscape conceptual framework in the context of AI and data capital [

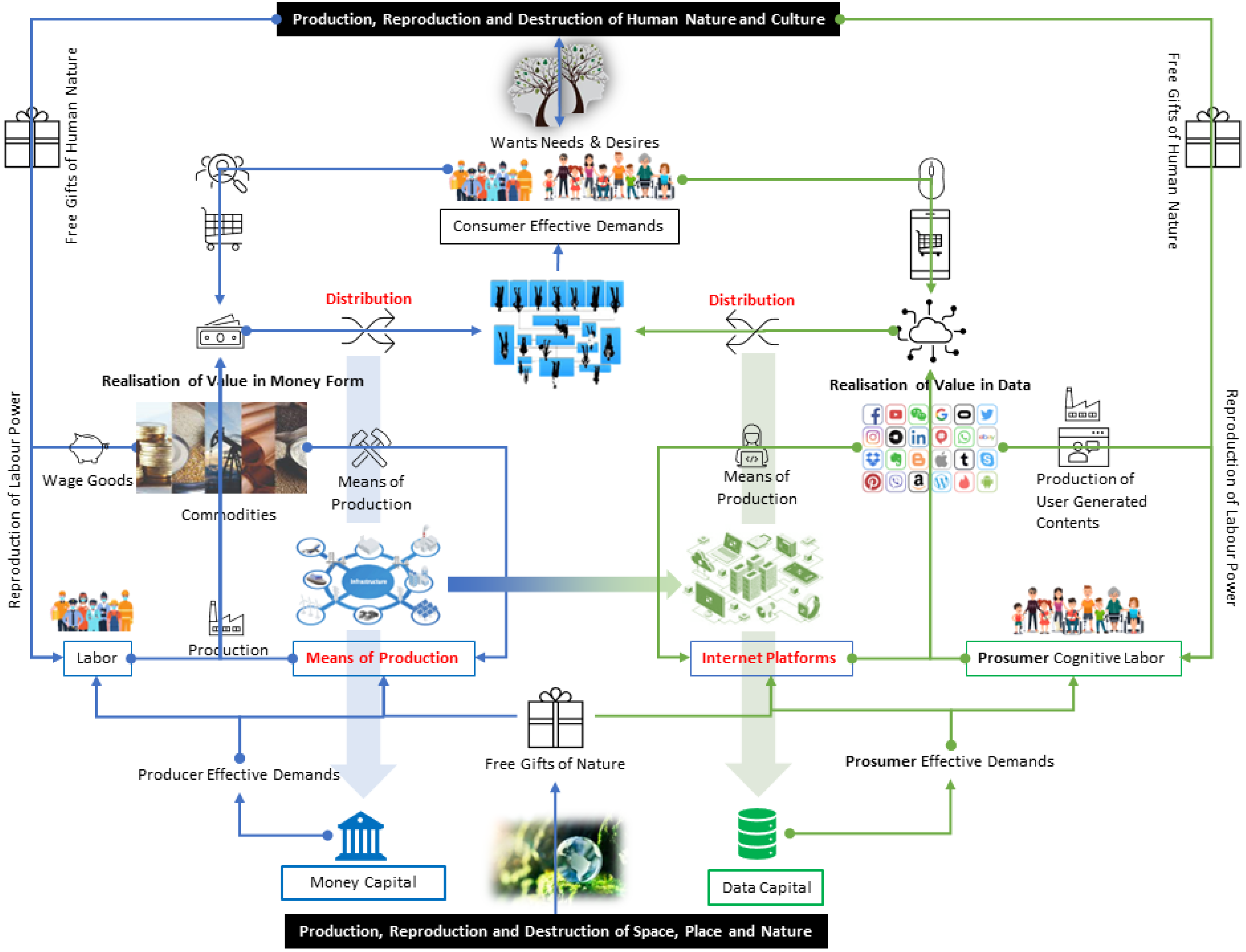

16]. We develop a consistent illustration of the IL framework in the work of David Harvey and that in the new contexts of data capital as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The driving power in traditional IL conceptualisation is money capital, which meets producer-effective demands. The effect combines with free gifts of nature to facilitate labour and the means of production. Produced commodities stimulate the realisation of value in monetary form after deducting wage goods and the cost of the means of production. The production, reproduction and destruction of human nature and culture shape the free gift of human nature and fundamental wants, needs, and desires. The resulting consumer effective demands are matched to the realisation of value in money form through marketing activities and create distribution to the producer, consumer, and back-to-money capital. In this IL framework, the key gateways to control the flow of money capital are the means of production and distribution.

In the new contexts of data capital [

16], in particular the recent AIGC and large model era, internet platforms have become the fundamental infrastructure. The new IL framework is particularly useful in understanding the technical development of contemporary AI, such as computer vision and natural language processing. The data capital IL framework discusses the differences and commonalities between the traditional bourgeoisie and the new bourgeoisie, referred to as neo-bourgeoisie. The traditional bourgeoisie owns the means of production and has high fixed costs, while the neo-bourgeoisie owns the means of connection and has low fixed costs. For example, digital products, such as online videos and games are not limited by their physical forms and can serve the scalable need of customers. The factors involved in production for the traditional bourgeoisie are land, labour, and capital, while for the neo-bourgeoisie, they are data and information. For example, many online services and products are free to use as the owner of a digital gateway can gather valuable data and information. Data can be used to supply further development for business analysis and AI training while information is essential in controlling information distribution and matching market needs. Both data capital and money capital have monopoly power and high economic rents. The framework also discusses the differences and commonalities between the proletariat and the neo-proletariat. The former is paid for labour hours, while the latter receives free services in exchange for personal data and cognitive working load.

Our work focuses on analysing the progress and perspective of DBCI technologies in the context of the data capital IL framework. Different to previous surveys that are technique-driven, this paper provides a hybrid paradigm. Firstly, we derive the survey structure using scoping review approach using the IL framework. Based on the derived structure, we then match the development of DBCI models and data using the systematic literature review approach. Meta-analysis is also provided to compare key parameters, such as DBCI applications, data statistics, and BCI devices.

3. Methodology

3.1. Conceptualisation of DBCI Industrial Landscape

So far, there are more than 600 BCI survey papers published from 1986 to 2024. However, none of the surveys has put the technical development of BCI in the context of the industrial landscape which is crucial to understand how the factors of data, devices, commercialisation, etc. are shaping research. Therefore, we introduce the recent data capital IL framework [

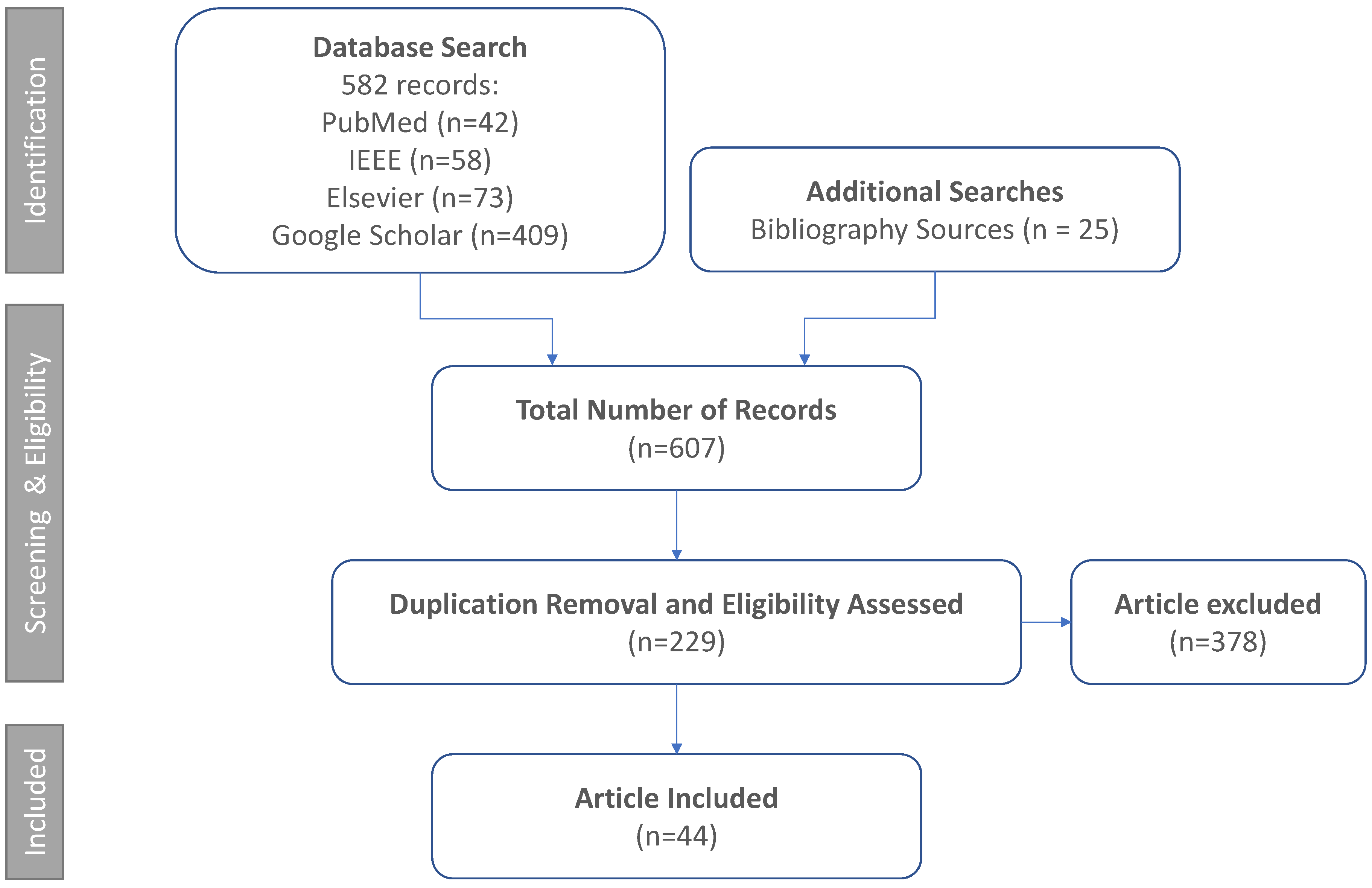

16] as an initial scoping review to narrow down and identify the following key topics. Our review methodology is summarised in

Figure 2. As a result, there are a total of 53 datasets included in this paper which contribute to the following four key topics.

DBCI applications consider the impact of big data and artificial intelligence (AI) on the economic, social, and political systems of the world. AI has increased the ability to produce more for economic growth and development while also making human labour obsolete. This creates a trajectory where capitalism remains the ultimate system, controlling the lives of labour through big data. However, the growth of AI also promotes technological innovation and investment, leading to economic growth. The profit-driven technological singularity of AI creates social challenges and potentially fatal economic impacts under a neoliberal economic system. AI also creates a digital divide and potentially expands existing societal rifts and class conflicts. It is essential to develop policies to protect labour, privacy, trade, and liability and reduce the consequences of AI’s impact on employment, inequality, and competition. The DBCI may create opportunities for individuals to monetise their personal data and potentially transfer control and ownership to actual data producers in a passive way, i.e. the mind activity and focused time consumption. Application is, therefore, a key parameter in evaluating the maturity and progress of the DBCI industrial landscape.

The Utility of DBCI The economic landscape has undergone major changes in the past few decades with the emergence of new Internet technologies and the creation of value through business model innovation using data and information. The factors of production have been redefined with data and information being recognised as new variables that have been made possible by technological breakthroughs in information and communications technology. The cost of computing power, data storage, and Internet bandwidth has decreased significantly, enabling the creation of increasingly rich digital information. This has given rise to new phenomena such as Big Data analytics and Internet platform companies. The democratisation of information and knowledge has also increased the bargaining power of workers and consumers whilst impacting Marxist philosophy in two areas related to value creation. The commodification of cognitive labour is the foundation of the new capitalist system in which modes of control over production, consumption, distribution, and exchanges are very different from earlier forms of capitalism in history. This new economy of capitalist transformation is referred to as ’cognitive capitalism.’ A fundamental parameter of cognitive capital is access to a large-scale population. In the context of DBCI research, this is closely tied to utility, which is defined by the cost of devices and the flexibility of usage paradigms.

Value of Cognitive Workload The traditional idea that the value of products and services is measured in labour hours has been challenged by the process of datafication, which involves dematerialization, liquefaction, and density. Digitisation has made it possible for companies like Netflix to offer on-demand services and gather data on user behaviour. Digital products are also non-rivalrous and non-excludable, which means that they can be used by many individuals at the same time without reducing their availability to others. The availability of free digital services and products also challenges the use of labour hours to value a product or service, as many are provided through advertising or other business models. The concept of the “Prosumer” further undermines the traditional value creation process, as much of the online content is produced by the consumer for free. While existing AIGC technologies have provided the premises for creation, the Cognitive Workload in DBCI provides one step further. The research of cognitive workload can potentially encourage a healthy and fair ecosystem for DBCI and other large models for real-world applications.

Data and Model Ownership The scoping review discusses how the traditional Marxist dichotomy between bourgeoisie owners of the means of production and proletariat workers has been upended by the emergence of platform-based internet companies. These companies, such as Amazon, Google, and Facebook, do not own the means of production but rather the means of connection to the internet, and they leverage large amounts of customer data to create value. The article also discusses the democratization of information and the shift in power from traditional owners to individuals and entrepreneurs, as well as the emergence of the sharing economy and the de-linking of assets from value. In the AIGC era, the AI ecosystem is moving from the traditional data capital to the current model capital paradigm, such as ChatGPT. Largescale deep models, regardless open-source or not, are no longer accessible to common users for model fine-tuning. Deep model API or MLaaS have become the dominant practice. In the DBCI research, deep learning models are among the early stages in this model capital wave. Our review will discuss the influence of existing data and AI model capitals to the DBCI domain.

3.2. Process of DBCI Data Capital Liquidation

The process of data asset liquidation is intrinsically linked to the broader landscape of DBCI applications, encompassing their utility, the value of cognitive workload, and data and model ownership. By systematically evaluating and managing data assets, we can maximise their potential in driving forward DBCI applications, which rely heavily on high-quality and extensive datasets to develop and refine models that enable innovative solutions in healthcare, neurorehabilitation, and beyond. Understanding the utility of DBCI involves assessing the cost-effectiveness and accessibility of devices and paradigms, ensuring that the technology can be widely adopted and utilised. Moreover, the value of cognitive workload emphasises the importance of accurately measuring and leveraging cognitive data to enhance user experience and productivity, making it crucial to manage and assess data quality effectively. This comprehensive approach to data asset liquidation not only supports the advancement of DBCI technologies but also addresses the multifaceted challenges and opportunities within the industry.

We summarise our broken-down assessment factors in

Table 1. Specifically, for BCI devices, frequency (Hz) indicates how often signals are sampled per second. Higher frequencies capture finer temporal resolution, which is crucial for tracking rapid brain activities. EEG channels represent the number of electrodes used in data collection. A higher number of channels offers better spatial resolution, capturing data from more regions of the brain. For DBCI Applications, high-frequency and multi-channel devices enable applications requiring precise brain activity mapping, such as neurorehabilitation and emotion recognition. For BCI utility, devices with higher frequency and channel count are more versatile but can be costlier and less portable. Optimising these metrics balances performance and usability in real-world settings. For the value of cognitive workload, accurate frequency and spatial resolution improve the fidelity of cognitive workload measurements, enabling deeper insights into attention, fatigue, and performance. For data and model ownership, high-resolution devices are often proprietary, with access to raw data or model training pipelines controlled by manufacturers. This raises questions about open standards and accessibility.

The second metric we consider is the data. For DBCI applications, longer trial lengths and diverse participant pools make the datasets applicable to a wider range of use cases, such as personalised neurofeedback or cross-cultural studies. For BCI utility, more trials and participants increase the dataset’s statistical power but also its complexity and storage requirements. This impacts its usability for researchers and practitioners. For the value of cognitive workload, repeated trials and diverse user data improve the accuracy and generalisability of cognitive workload models, ensuring they work effectively across different scenarios. And, for data and model ownership, datasets with longer trials and diverse users often require substantial investment. Ownership can dictate access, limiting opportunities for public or collaborative research. Specifically, we use length (s) for the duration of each recorded trial, which impacts the total data volume and its utility in capturing prolonged cognitive states. Trials reflect the number of repetitions per user, affecting dataset reliability and robustness. Users indicate the number of participants in a dataset, determining its diversity and generalisability across populations.

Finally, we consider applications in terms of stimuli, task, and response as metrics. The type of stimuli (e.g. visual, auditory) presented to participants defines the context of the dataset and its relevance to specific applications. Task describes what participants were asked to do (e.g., motor imagery, attention tasks), directly linking the dataset to specific DBCI use cases. Response refers to the recorded data types (e.g., EEG signals, behavioural responses), which determine the modalities available for model training and application. For DBCI applications, stimuli, tasks, and responses define the real-world scenarios where the dataset can be applied. For example, datasets with motor imagery tasks are crucial for prosthetics, while emotional stimuli datasets are vital for affective computing. For utility, datasets with diverse stimuli and task types are more flexible but require sophisticated annotation and preprocessing, impacting ease of use. The value of cognitive workload is often associated with the stimuli and task types that influence cognitive demands, making these metrics critical for accurately modelling workload and designing adaptive systems. Data and model ownership can be reflected by datasets with complex stimuli and multi-modal responses which are often proprietary due to the cost and effort involved in collection, limiting broader accessibility and collaboration.

4. Survey Results

Our survey results are summarised in

Table 2. The table summarises a comprehensive survey of BCI datasets, focusing on metrics across devices, data, and applications. These metrics provide a valuable foundation for understanding the current landscape of BCI data capital and its alignment with key technical and industrial challenges. Below are the general descriptions of the dataset characteristics based on the metrics presented.

For devices, the datasets span a wide range of sampling frequencies, from low frequencies such as 128 Hz in the NeuroMarketing dataset to very high frequencies like 2048 Hz in the Statistical Parametric Mapping dataset. High-frequency datasets, such as ThingsEEG-Text (1000 Hz), are ideal for capturing rapid neural dynamics, essential for decoding precise temporal brain activity. Lower frequencies are generally sufficient for static tasks or simple signal processing, such as motor imagery. The number of EEG channels varies significantly, ranging from 1 channel (e.g., Synchronised Brainwave) to 256 channels (e.g., HeadIT dataset). Multi-channel setups are crucial for high spatial resolution, supporting applications like emotion recognition (SEED dataset) or complex neural decoding (GOD-Wiki).

In the data category, trial durations vary widely, with some datasets focusing on short, event-related trials (e.g., DIR-Wiki (2 seconds)) and others providing longer continuous recordings (e.g., Sustained Attention (5400 seconds)). Shorter trials are suitable for tasks like P300 spellers, whereas longer recordings are necessary for sustained attention or neurofeedback studies. Trials and Users: The number of trials and participants reflects the dataset’s diversity and robustness. For instance: DIR-Wiki includes 2400 participants, making it highly suitable for inter-person generalisability. ThingsEEG-Text provides 8216 trials per user, supporting inter-sample learning for robust model training. Smaller datasets, like BCI Competition IV dataset 1 (7 participants), are ideal for exploring targeted applications or algorithms.

For applications, the datasets incorporate a variety of stimuli types, such as visual cues, audio cues, and videos, to simulate diverse cognitive and sensory tasks. For example: HCI Tagging utilises both images and videos for emotion recognition. GOD-Wiki integrates images and text, making it a prime example for visual-semantic decoding applications. Most datasets focus on motor imagery, a staple task in BCI research. However, emerging tasks like neural decoding (e.g., GOD-Wiki) and emotion recognition (e.g., SEED, DEAP) indicate growing interest in expanding the scope of BCI applications. Multi-modal datasets that include EEG and additional modalities (e.g., EEG, fMRI, Image, and Text in GOD-Wiki) are increasingly prevalent. These datasets support advanced tasks like zero-shot neural decoding and multi-modal integration, critical for expanding BCI applications. Summary of Dataset Contributions Support for BCI Applications:

Overall, motor imagery remains the most common task, providing a benchmark for BCI algorithm development. Novel tasks like neural decoding and emotion recognition reflect the evolution of BCI datasets toward more complex and versatile applications. Datasets with high temporal (e.g., ThingsEEG-Text) and spatial resolution (e.g., HeadIT) are critical for improving utility in advanced modelling techniques. Large participant pools (e.g., DIR-Wiki) ensure generalisability across diverse populations. Multi-modal datasets like SEED and HCI Tagging are invaluable for studying cognitive workload in realistic scenarios, enabling adaptive DBCI systems. Datasets with diverse trial designs and stimuli improve the fidelity of cognitive workload modelling. Open datasets like BCI Competitions and BraVL promote accessibility and collaborative research. Proprietary datasets with restricted access, particularly those involving high-cost modalities like fMRI, highlight the ongoing need for equitable data-sharing practices.

The diversity and richness of datasets summarised in the table provide a strong foundation for advancing DBCI research. The wide range of device specifications, data configurations, and application contexts ensures that these datasets are well-suited to address the challenges of generalisability, scalability, and adaptability in BCI systems. Next, we provide in-depth analysis with enhanced insights for each category

4.1. Device

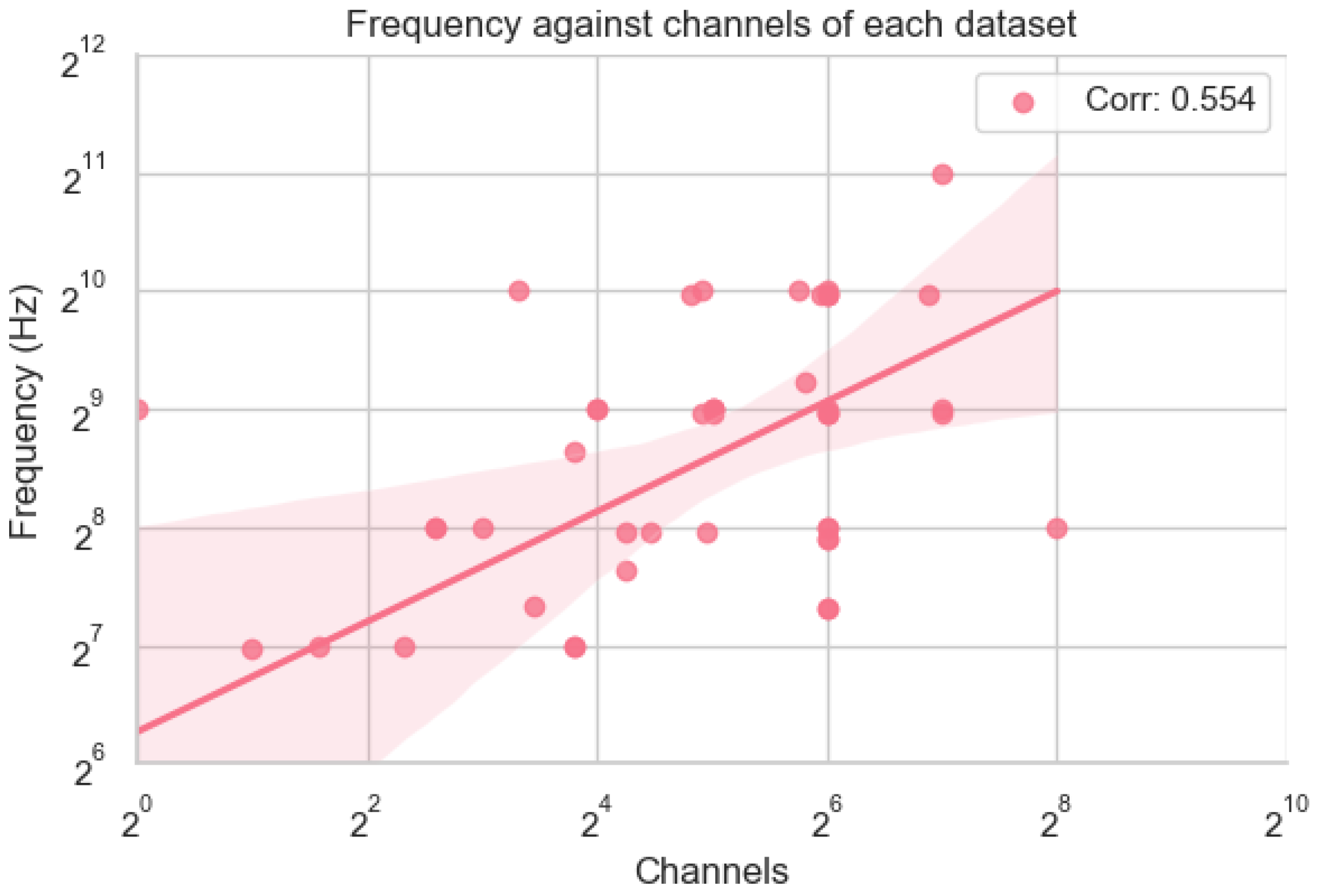

The scatter plot in

Figure 3, illustrating the relationship between frequency (Hz) and the number of EEG channels, was generated using the dataset information provided in the table. Both frequency and channel data were transformed into a log-2 scale to allow for a more interpretable comparison across datasets with varying magnitudes. The dataset "Confusion During MOOC," which had an unusually low frequency of 2 Hz, was excluded to avoid distortion of the plot. The x-axis represents the log-2 of the number of channels, while the y-axis represents the log-2 of the frequency. Each point on the scatter plot corresponds to a dataset, allowing us to visualise the distribution and clustering of datasets based on their device configurations. This approach highlights key patterns and outliers in the data, such as datasets with exceptionally high temporal or spatial resolution, facilitating deeper analysis of trends in DBCI devices.

Analysing the scatter plot reveals several notable trends and insights into the current state of device metrics in DBCI datasets. The majority of datasets cluster around 32–64 channels and 128–512 Hz frequencies, reflecting the most common experimental setups in EEG research. This range balances temporal and spatial resolution, making it suitable for general-purpose applications such as motor imagery, emotion recognition, and cognitive workload studies. A few datasets stand out as outliers. For example, HeadIT features an exceptionally high number of channels (256), which enhances spatial resolution and is particularly valuable for advanced applications like high-resolution neural decoding or emotion recognition. On the other hand, datasets like Enterface06 (1024 Hz) and Statistical Parametric Mapping (2048 Hz) offer exceptionally high temporal resolution, enabling precise tracking of rapid neural dynamics. These high-frequency datasets are critical for applications such as speech imagery, real-time neurofeedback, or fine motor control.

Interestingly, there is a moderately positive correlation of 0.554 between the frequency and number of channels. This may be a result of technology improving over time with more modern devices having a greater bandwidth, resulting in both a higher frequency and a large number of channels. Alternatively, this may not be due to fundamental bandwidth limitations and instead due to financial limitations where devices with high bandwidth may be too expensive. This highlights a limitation of our study and we leave it to future work to investigate the price BCI devices.

From an industrial landscape perspective, the clustering of datasets around 32–64 channels and 128–512 Hz frequencies reflects the standardisation of EEG devices. This standardisation ensures compatibility and widespread usability across research and clinical settings, contributing to the utility of these devices. However, datasets that rely on higher-channel and higher-frequency devices often involve proprietary equipment, raising challenges related to data and model ownership. Furthermore, datasets with extreme configurations, such as high-channel or high-frequency setups, cater to niche applications but may face scalability and cost-effectiveness challenges in real-world DBCI deployment. Overall, the diversity in device configurations highlights the ongoing need to balance spatial and temporal resolution to meet the varying demands of DBCI applications. While standard configurations dominate due to their general usability, high-resolution setups offer unique opportunities for advanced research, albeit with limitations in accessibility and scalability.

4.2. Data

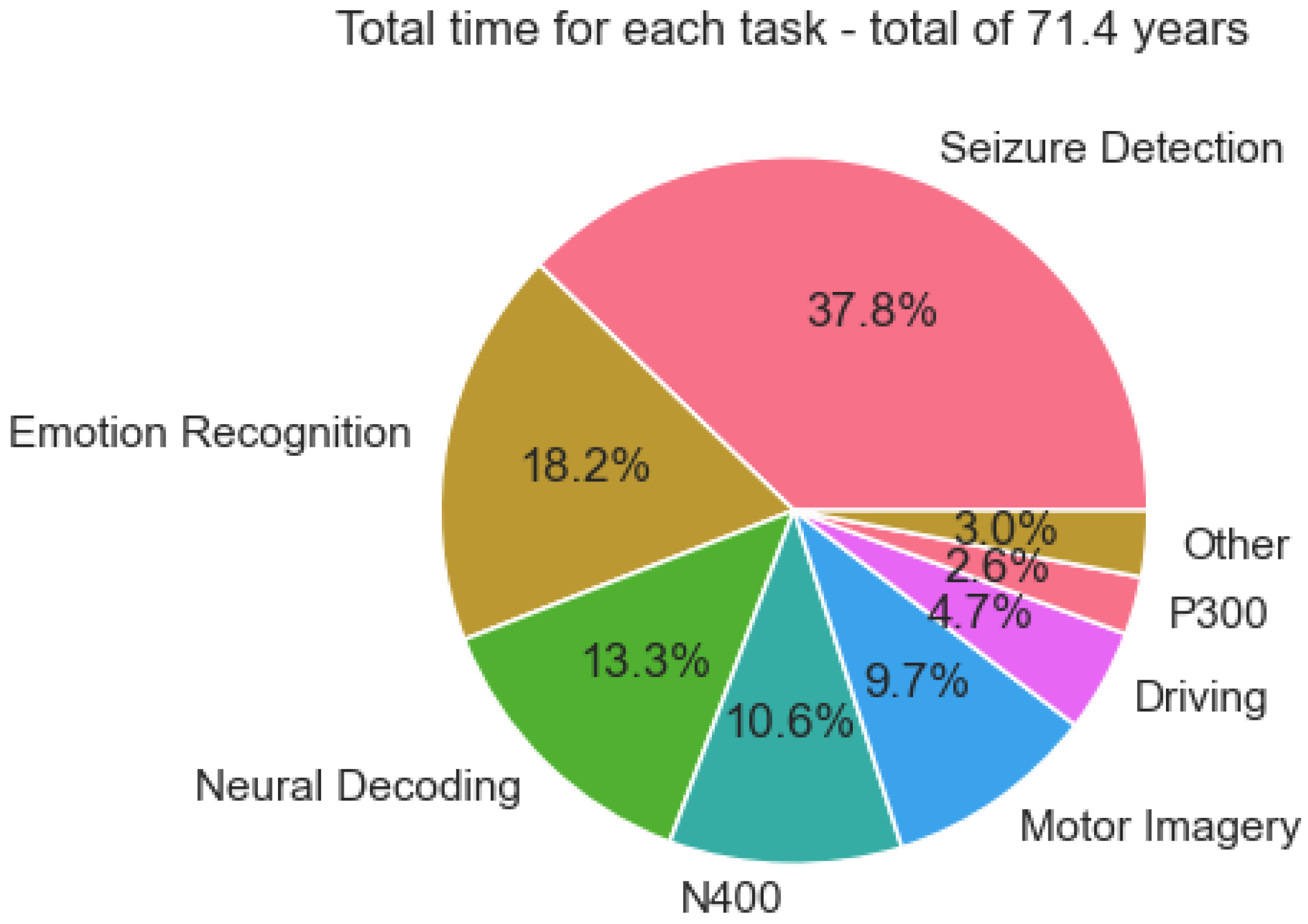

The pie chart was created to represent the proportion of accumulated data for each task, such as seizure detection, emotion recognition, and neural decoding, based on the provided formula:

This formula calculates the total recording time for each dataset in years by multiplying the number of EEG channels, the length of each trial, the number of trials per subject, and the number of subjects. The datasets were then grouped by task, and the total recording time for each task was summed. Tasks with less than 1.5 years of data were combined into the "Other" category to simplify the visualisation. The total accumulated data across all tasks was 71.4 years, and the pie chart shows the fraction of this total for each task. We summarise our findings according to the industrial landscape framework:

Applications The pie chart analysis highlights the dominance of seizure detection, accounting for 37.8% of the total data. This reflects the clinical priority of seizure detection in healthcare, where its applications in epilepsy diagnosis and monitoring are highly established. It’s worth noting that the data for seizure detection comes from a single large data set, the

TUH EEG Corpus[

74]. The impressive size of this dataset shows that a large volume of data can be gathered when a device is widely deployed. Furthermore, this is a very diverse dataset with data coming from over 10,000 patients, meaning that a model trained on this data will be robust due to the high inter-subject variability. These factors combined make the dataset well-suited for real-world deployment, showing that seizure detection is a mature task in the DBCI application landscape. On the other hand, tasks like emotion recognition (18.2%) and neural decoding (13.3%) represent expanding frontiers in BCI research. These emerging applications cater to the rising demand for adaptive systems in mental health, emotion-aware technologies, and cognitive analysis, showcasing their growing relevance in the industrial framework. However, tasks like driving (4.7%) and P300 paradigms (2.6%) remain underrepresented despite their direct applicability to safety-critical applications and assistive devices, indicating the need for further investment to enhance their practical deployment.

Utility The dataset distribution underscores the significant utility of core tasks like motor imagery (9.7%) and N400 (10.6%) in the DBCI landscape. Motor imagery serves as a cornerstone for neurorehabilitation and prosthetic control, while N400 supports applications in linguistic processing and cognitive workload analysis. Their substantial data representation highlights their importance for developing reliable and scalable BCI systems. In contrast, the other category (3%) and specialised tasks like driving-related paradigms reflect limited utility due to insufficient data accumulation. Expanding data collection efforts for these underrepresented areas could significantly enhance their scalability and integration into diverse real-world applications, fostering a more balanced utility across the DBCI domain.

Value of Cognitive Workload The significant proportion of datasets dedicated to emotion recognition and neural decoding reflects a growing emphasis on modelling cognitive workload within the DBCI landscape. These tasks enable the development of systems that adapt to users’ cognitive and emotional states, supporting advanced applications such as emotion-aware interfaces, cognitive workload management, and mental health monitoring. However, the limited data availability for tasks in the other category suggests missed opportunities for expanding cognitive workload research into less-explored domains. A more diversified dataset ecosystem could provide deeper insights into user cognition and behaviour, enhancing the adaptability and personalisation of DBCI systems.

Data and Model Ownership The dominance of seizure detection datasets highlights a relatively mature ecosystem for data collection, sharing, and model development in this domain. This maturity offers opportunities to refine data-sharing frameworks, ensuring equitable access and fostering collaborative research. However, the limited representation of lesser-explored tasks, grouped under the other category, presents challenges related to data ownership and accessibility. Addressing these challenges requires the establishment of robust frameworks for data sharing and ownership, particularly for underrepresented tasks. This would support a more equitable and innovative landscape for developing open-access datasets and models across the DBCI spectrum.

4.3. Application

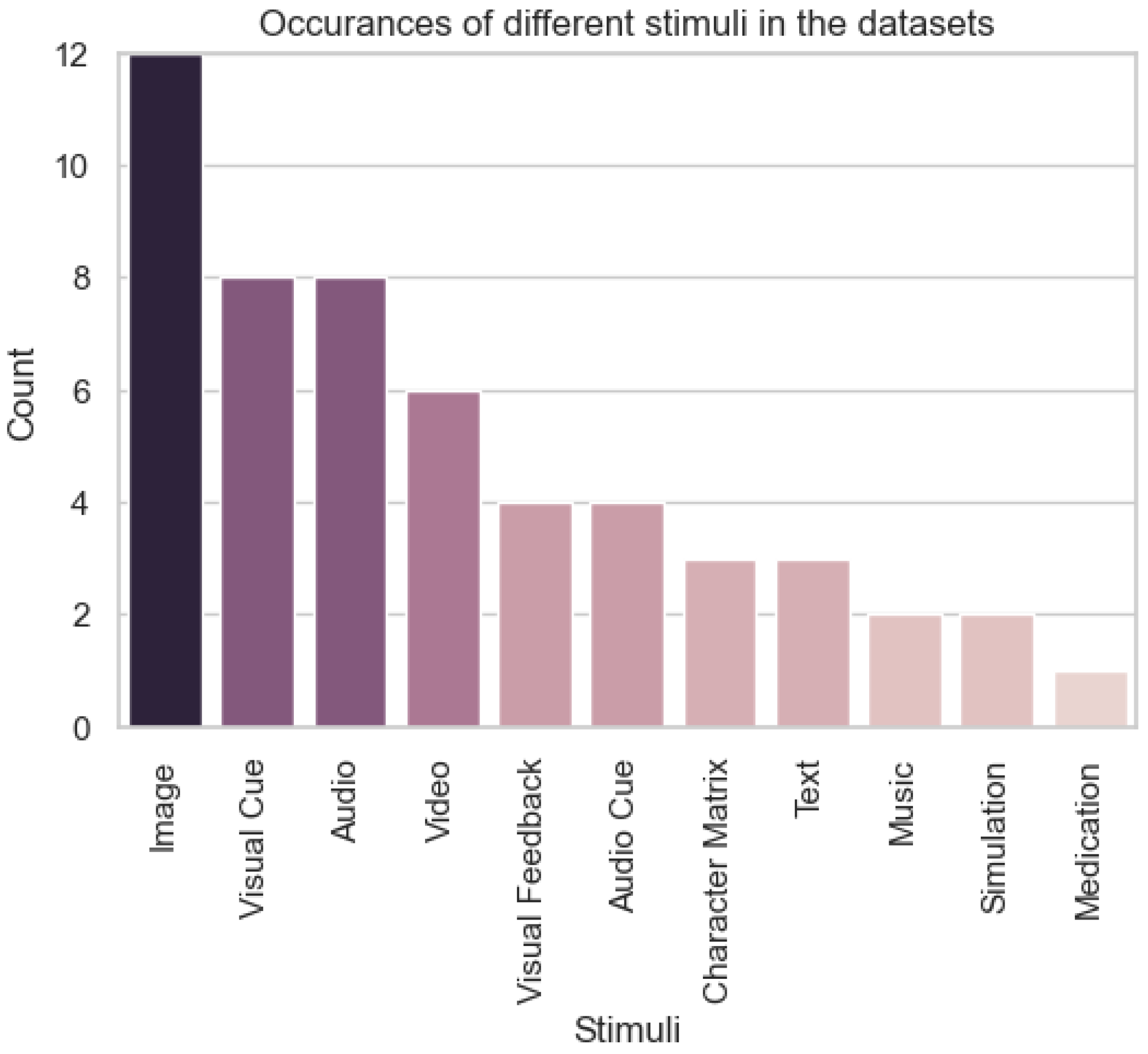

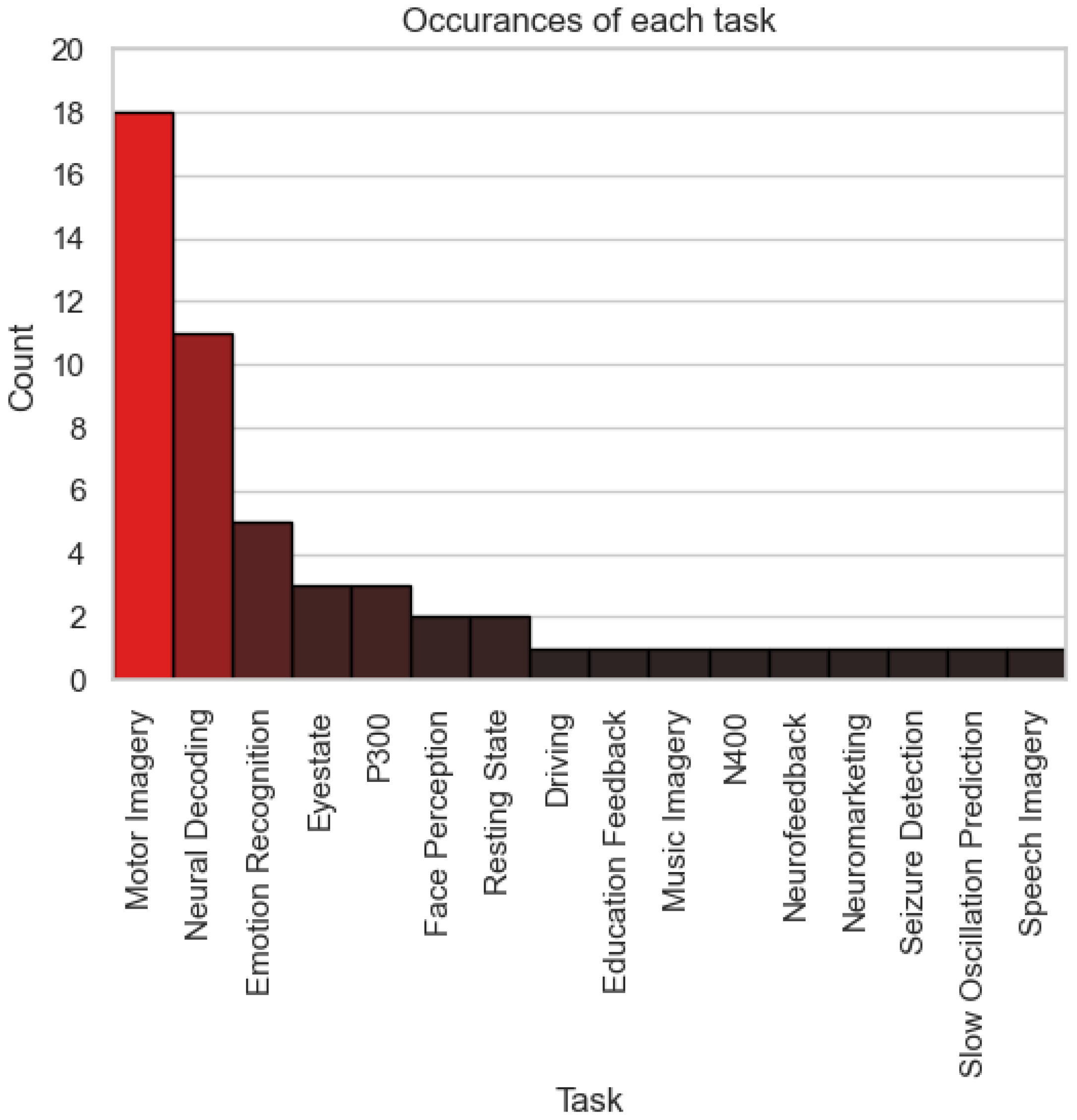

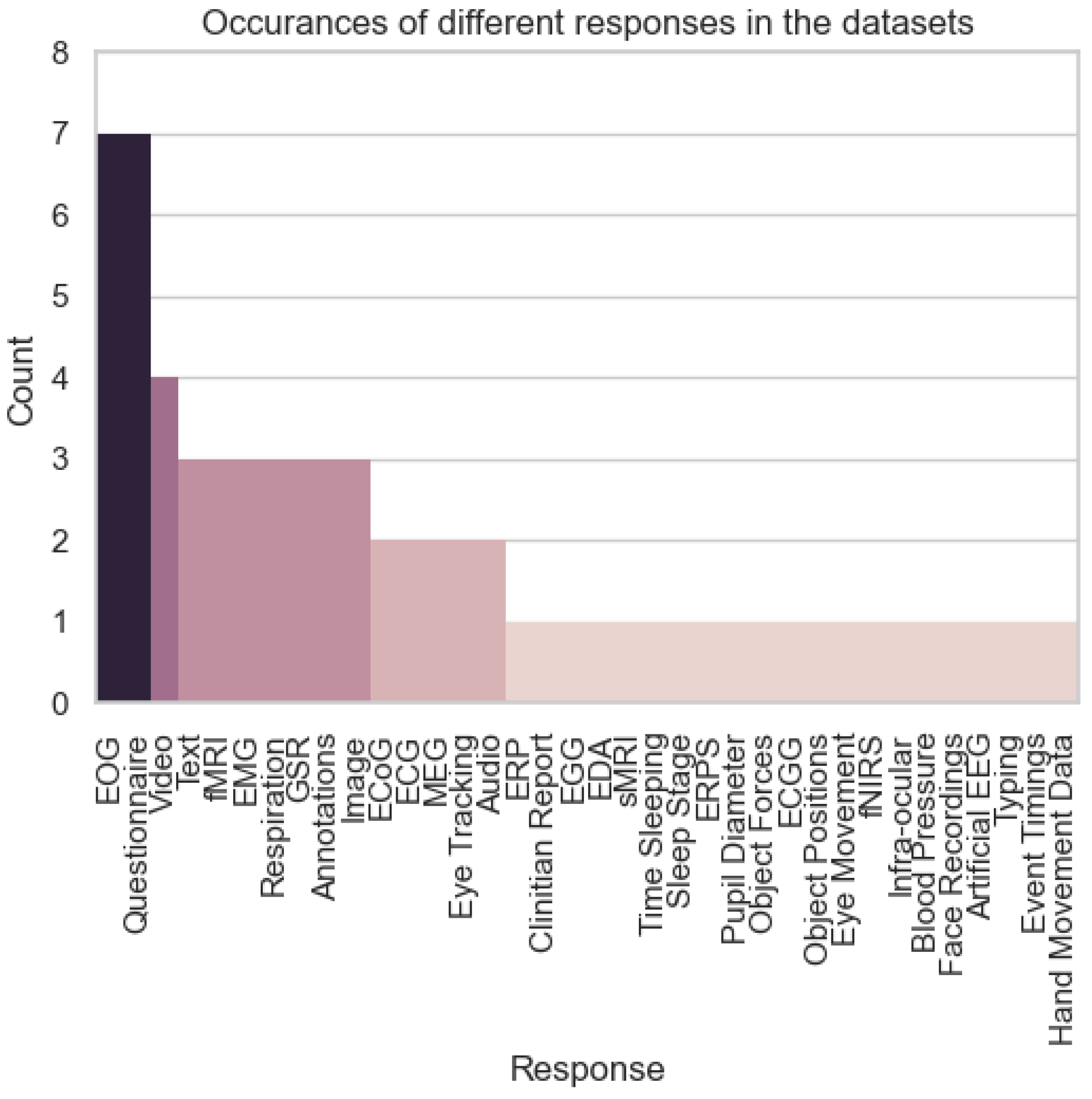

To analyse the distribution of stimuli, tasks, and responses across datasets, three bar charts were created. For stimuli, a bar chart was generated to show the number of times each type of stimulus (e.g., visual cues, audio cues, video) was featured in a dataset. For tasks, another bar chart represented the frequency of each task (e.g., motor imagery, emotion recognition, seizure detection) in the datasets. For responses, the chart depicted the number of datasets that recorded various responses (e.g., EMG, EOG, fMRI). EEG, being the dominant response type, was excluded from the responses chart to avoid overshadowing other data modalities. In total, the analysis considered 47 datasets that recorded EEG, allowing a detailed exploration of how stimuli, tasks, and responses are distributed in the DBCI landscape.

Figure 5 shows that the distribution of stimuli reveals a strong focus on visual stimuli, which dominate the datasets. Visual cues feature heavily in tasks like motor imagery, whilst images appear more in tasks that require more complicated stimuli, like neural decoding and emotion recognition. However, the inclusion of audio cues and video stimuli in several datasets reflects the expanding diversity of applications, such as emotion recognition and cognitive workload assessment, which demand multi-modal data to mimic real-world environments. The growing use of diverse stimuli suggests a shift toward broader applicability of DBCI systems, including multimedia interactions and adaptive user interfaces.

The analysis of tasks in

Figure 6 underscores the dominance of foundational paradigms, like motor imagery and seizure detection, which are critical for clinical and rehabilitative applications. However, the emergence of tasks like emotion recognition and neural decoding signals the diversification of DBCI utility into consumer-oriented applications, such as mental health monitoring and cognitive enhancement tools. These trends indicate that DBCI research is moving beyond traditional clinical use cases toward more general-purpose systems that align with evolving user needs and technological capabilities.

The response data in

Figure 7 highlights the inclusion of multi-modal recordings, such as EOG, EMG, and fMRI, alongside EEG. The use of these additional modalities supports the modelling of complex cognitive and emotional states, which are critical for understanding cognitive workload in diverse scenarios. For example, datasets incorporating fMRI and EOG responses provide high-resolution insights into brain activity and eye movements, respectively, enriching the development of adaptive and context-aware DBCI systems. This multi-modal approach aligns with the growing emphasis on cognitive workload evaluation, ensuring that systems can dynamically respond to users’ mental states.

Finally, the growing inclusion of alternative responses such as EMG and fMRI indicates a diversification of data modalities, which has implications for data and model ownership. Proprietary restrictions associated with high-cost modalities like fMRI may limit accessibility and collaboration. On the other hand, the widespread use of EEG reflects a more open ecosystem, promoting data sharing and model development. Addressing ownership challenges for multi-modal datasets is crucial for fostering equitable innovation in the DBCI domain.

4.4. Zero-Shot Neural Decoding Techniques

The above analysis of DBCI data capital has shown a critical juncture. While traditional deep learning or machine learning approaches may still struggle with the limited devices, data, and applications, emerging techniques such as Zero-Shot Neural Decoding (ZSND) and the availability of high-quality, multimodal datasets from other domains are enabling solutions to longstanding challenges. In this section, we synthesise the contributions of ZSND techniques and dataset metrics to address our claim of establishing a technical roadmap for overcoming barriers in DBCI applications, utility, cognitive workload, and data and model ownership.

ZSND techniques [

78] enable DBCI systems to generalise across unseen samples, individuals, devices, domains, and tasks without extensive retraining. These capabilities are made possible by cutting-edge frameworks such as BraVL, which integrates brain activity with visual and linguistic information through trimodal learning approaches. The use of multimodal data ensures that models can transfer knowledge effectively, mitigating the following challenges:

Inter-Sample and Inter-Person Transfer ZSND datasets, such as DIR-Wiki with 2400 participants and ThingsEEG-Text with 8216 trials per participant (10 participants), provide the diversity necessary for robust inter-person generalisation. These datasets allow models to adapt to neural variability across individuals, a critical requirement for DBCI applications like personalised neurorehabilitation. Inter-sample transfer is enhanced by the trial-level richness of datasets, as seen in ThingsEEG-Text, which captures high temporal resolution (1000 Hz) data across multiple conditions.

Inter-Device and Inter-Domain Transfer By incorporating multiple modalities such as EEG, fMRI, image, and text, ZSND datasets bridge the gap between invasive and non-invasive techniques, facilitating inter-device adaptability. For example, BraVL supports the alignment of brain signals recorded via EEG or fMRI with visual and semantic stimuli, ensuring models remain functional across diverse hardware environments. Inter-domain transfer is critical for applying DBCI systems in new contexts, such as transitioning from laboratory settings to real-world applications. The multimodal design of GOD-Wiki and DIR-Wiki exemplifies how datasets can support cross-domain learning.

Inter-Task Transfer Neural decoding tasks in datasets like GOD-Wiki and ThingsEEG-Text demonstrate the capability of ZSND techniques to generalise across tasks. Models trained on image decoding tasks can seamlessly adapt to semantic decoding tasks due to shared latent representations. This inter-task flexibility is crucial for multi-purpose DBCI systems, enabling applications ranging from motor imagery control to emotion recognition.

Unility Enhancement Frameworks like BraVL leverage multimodal data integration to create robust visual-semantic neural signal models. These models align brain activity with both visual and linguistic information, expanding the scope of DBCI applications to include cognitive workload assessment, attention monitoring, and adaptive feedback systems. The inclusion of high-resolution data (e.g., 64-channel EEG in all datasets and 1000 Hz sampling in ThingsEEG-Text) enables advancements in signal processing techniques to improve signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Enhanced SNR is essential for the scalable adaptation of DBCI devices in real-world environments.

Beyond the ZSND techniques, the high-quality data published also established a foundation for DBCI Progression. Our proposed metrics highlight the contributions of the datasets to the industrial landscape conceptualisation framework:

Devices: High-frequency datasets such as ThingsEEG-Text ensure precise temporal resolution for decoding dynamic neural activity. The consistent use of 64-channel setups across datasets provides the spatial granularity necessary for diverse applications.

Data: Datasets like DIR-Wiki, with its 2400 participants, address the need for diversity in neural data, improving inter-person generalisability.

Applications: Multimodal stimuli in GOD-Wiki and DIR-Wiki datasets, including image and text, expand the applicability of DBCI systems to multi-modal tasks. Neural decoding tasks recorded in these datasets align directly with the practical needs of applications such as neurorehabilitation, cognitive monitoring, and emotion recognition.

Overall, our work establishes a roadmap for DBCI research by identifying key barriers and demonstrating how ZSND techniques and dataset metrics address them. ZSND datasets and techniques enable generalisation across diverse stimuli and tasks, expanding the applicability of DBCI systems. The inclusion of diverse participants and trials increases dataset reliability and usability, supporting scalable and robust model training. Multimodal data and advanced signal processing improve the fidelity of workload modelling, ensuring adaptive and context-aware systems. While proprietary aspects of devices and datasets remain a challenge, open frameworks like BraVL and publicly available datasets mitigate access barriers, fostering collaboration and innovation.

While ZSND techniques and datasets provide significant advancements, further work is needed to fully realise the potential of DBCI systems. Future efforts could focus on: 1) Expanding Modalities: Incorporating additional data modalities such as MEG or wearable EEG devices to enhance data diversity and usability; 2) Self-Supervised Learning: Leveraging unsupervised techniques to reduce dependency on large-scale annotated data, improving efficiency and scalability. 3) Standardisation: Establishing universal standards for dataset annotation and evaluation to enable seamless integration and benchmarking across research groups. By leveraging ZSND techniques and metrics, this roadmap provides a clear pathway for overcoming barriers and advancing the industrial framework of DBCI systems.