Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Banana Starch

2.3. Proximate Composition of Isolated Starch

2.4. Amylose Content

2.5. Analysis of Functional Properties

2.6. Morphology and Particle Size Distribution Analysis of Starch Granules

2.7. X-Ray Difffraction Analysis

2.8. Pasting Properties

2.9. Thermal Properties

2.10. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrum

2.11. Gel Texture Properties of Starch

2.12. In Vitro Digestion Analysis

2.13. Enzymatic Kinetics

2.14. Postprandial Glycemic Response of Starch

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Composition

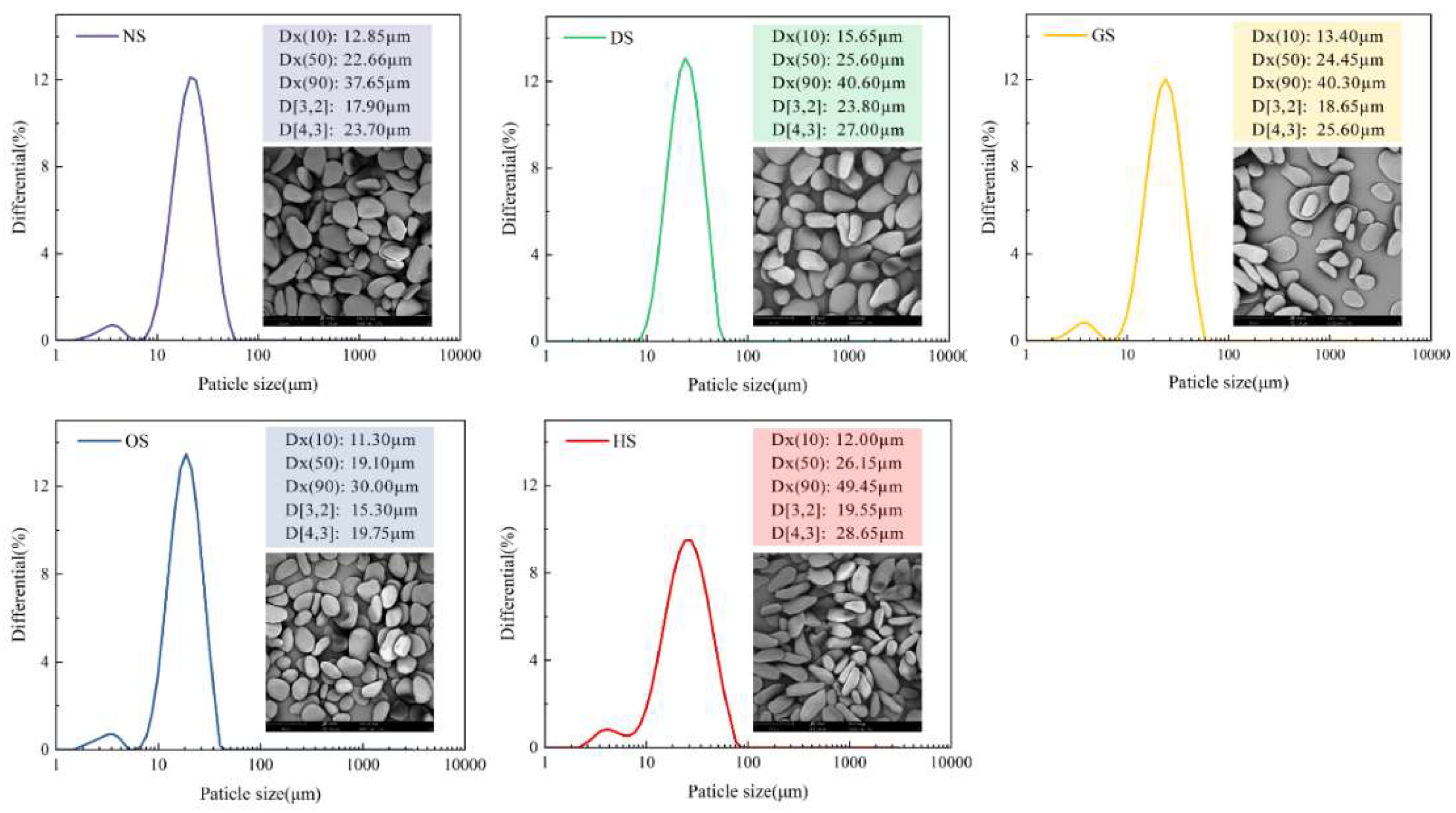

3.2. Morphology and Particle Size Distribution Analysis of Starch Granules

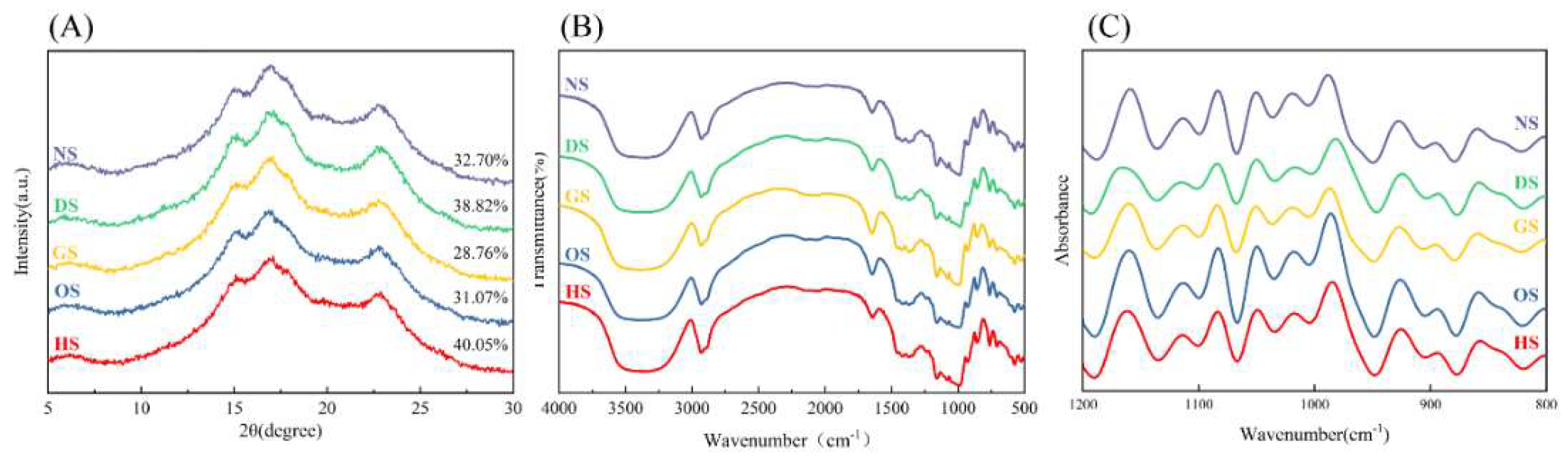

3.3. Crystalline Structure

3.4. Short-Range Ordered Structure

| Sample | Short-Ordered Parameters | |

| DO(R1047/1022) | DD(R955/1022) | |

| NS | 2.55±0.20b | 3.37±0.49b |

| DS | 3.37±0.04a | 4.67±0.03a |

| GS | 2.46±0.13b | 3.27±0.13b |

| OS | 2.49±0.24b | 2.65±0.42b |

| HS | 2.69±0.10b | 4.36±0.06a |

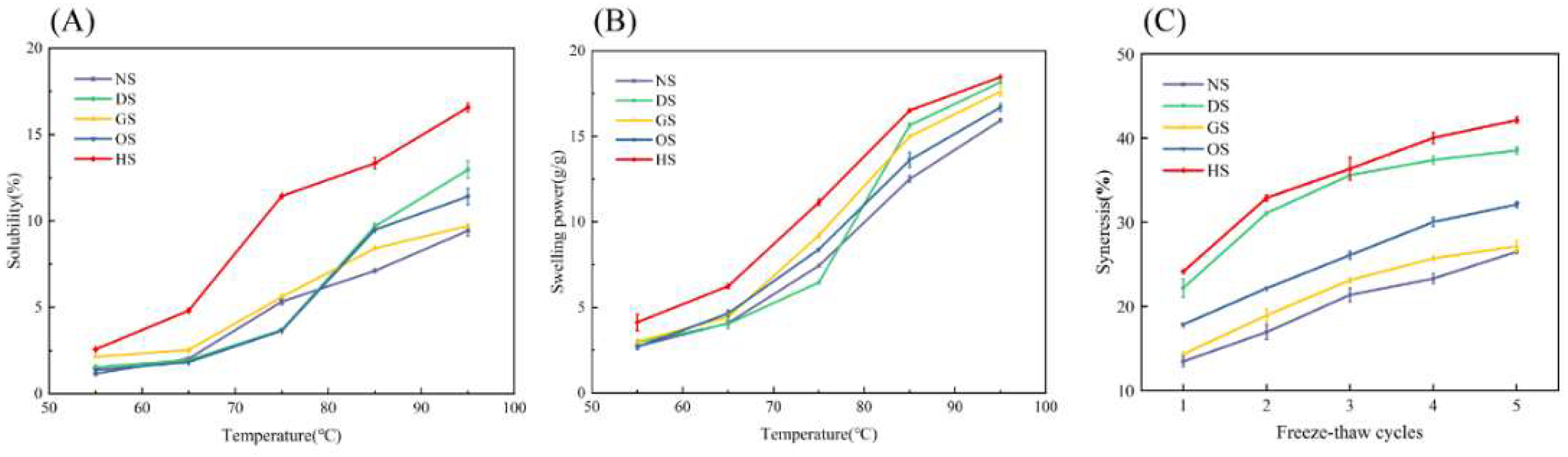

3.5. Solubility, Swelling Power and Freeze-Thaw Stability

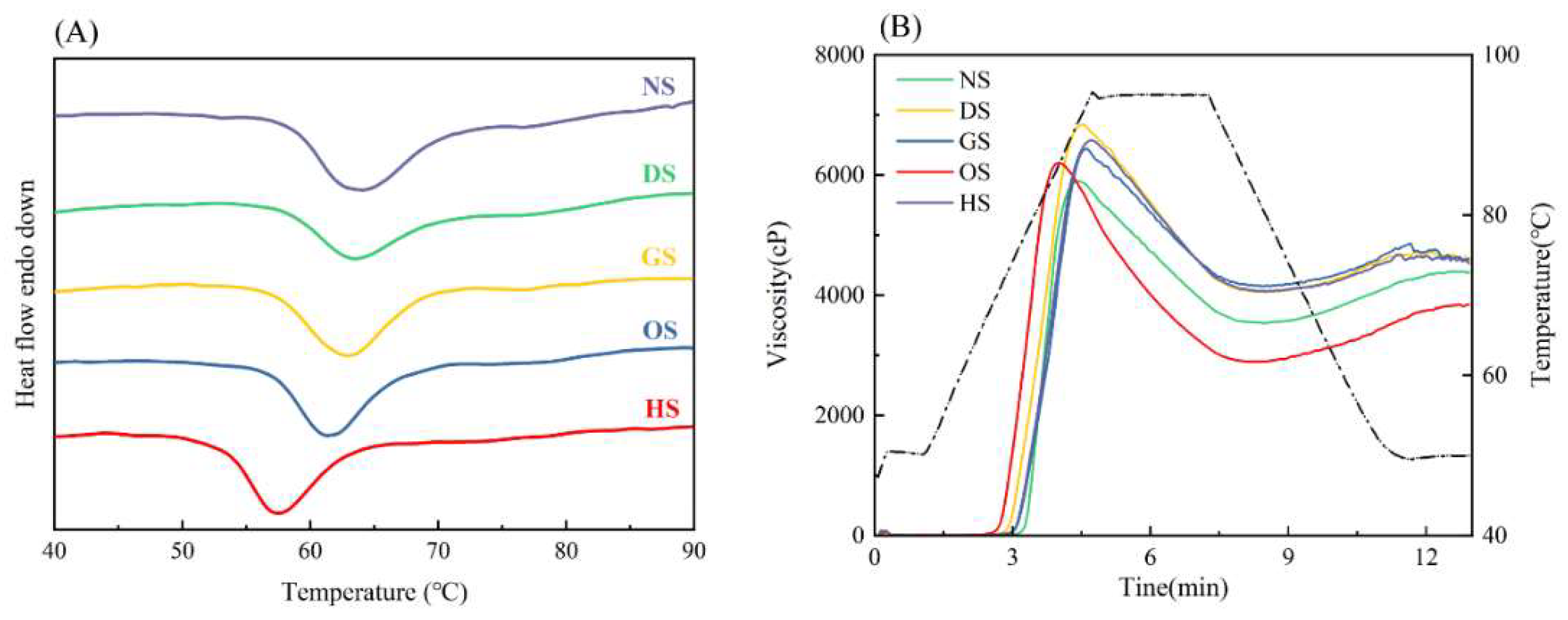

3.6. Thermal Properties

3.7. Pasting Properties

3.8. Textural Properties

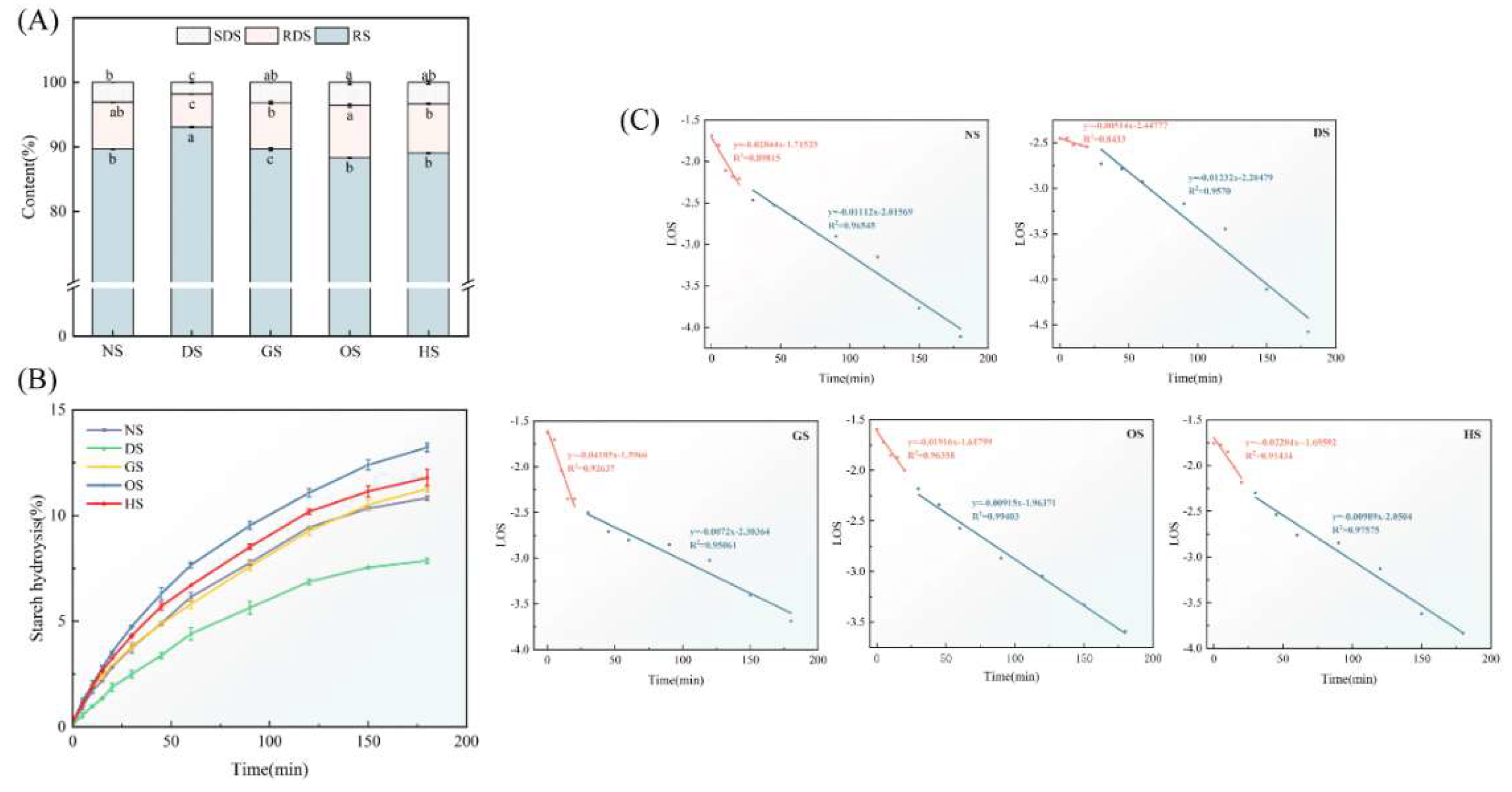

3.9. In Vitro Digestibility

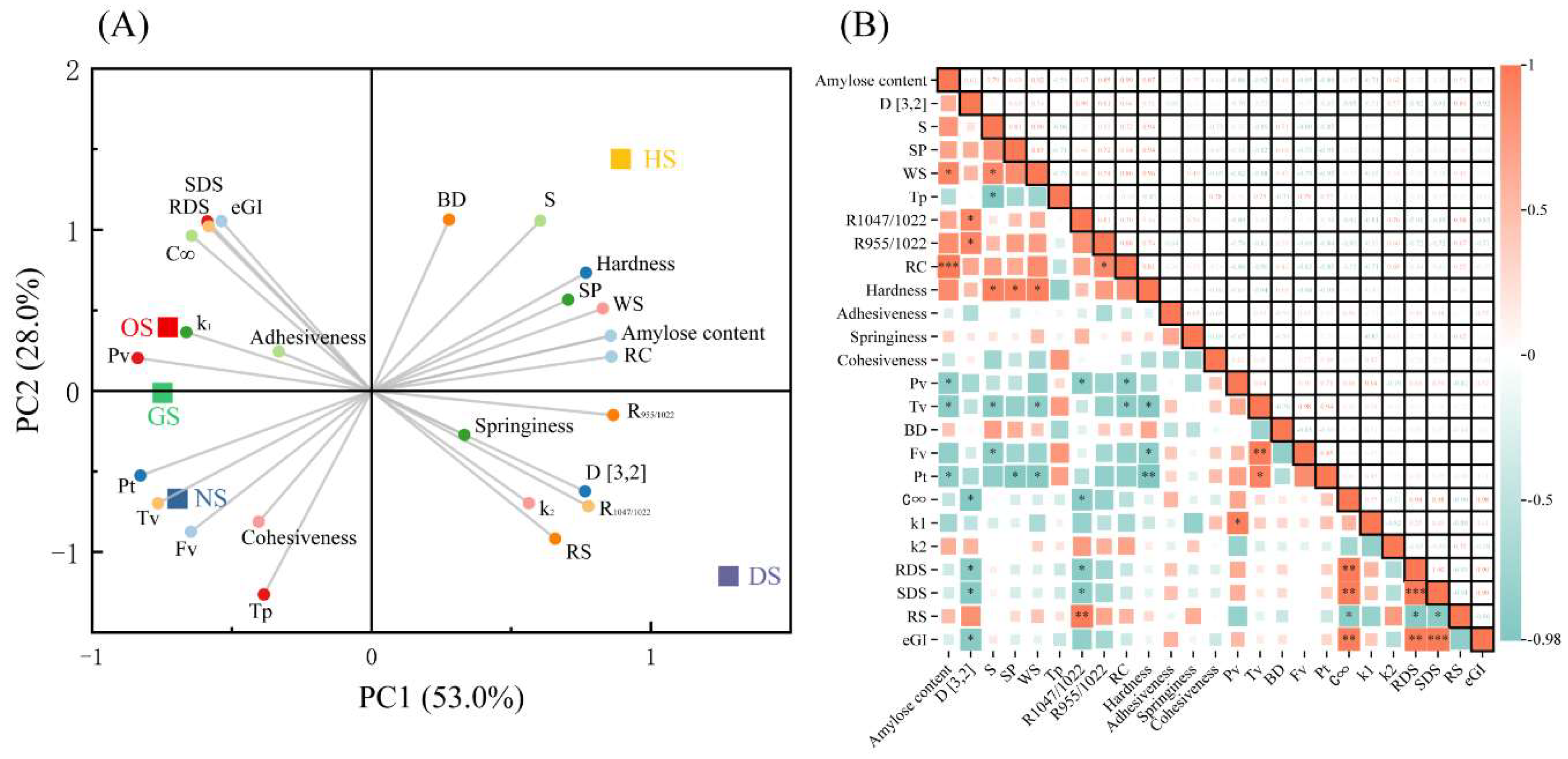

3.7. Principal Component and Correlation Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Bi, Y.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Digestibility and Changes to Structural Characteristics of Green Banana Starch during in Vitro Digestion. Food Hydrocolloids 2015, 49, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chang, L.; Jiang, F.; Zhao, N.; Zheng, P.; Simbo, J.; Yu, X.; Du, S. Structural, Physicochemical and Rheological Properties of Starches Isolated from Banana Varieties (Musa Spp. ). Food Chemistry: X 2022, 16, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Barros Mesquita, C.; Leonel, M.; Franco, C.M.L.; Leonel, S.; Garcia, E.L.; Dos Santos, T.P.R. Characterization of Banana Starches Obtained from Cultivars Grown in Brazil. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 89, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, A.M. Plasticization and Self Assembly in the Starch Granule. Cereal Chem 2001, 78, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Chen, J.; Jin, X.; Chen, J.; Ding, Y.; Shi, M.; Guo, X.; Yan, Y. Effect of Inulin on Thermal Properties, Pasting, Rheology, and In Vitro Digestion of Potato Starch. Starch Stärke 2023, 75, 2200217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Pan, R.; Obadi, M.; Li, H.; Shao, F.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Xu, B. In Vitro Starch Digestibility of Buckwheat Cultivars in Comparison to Wheat: The Key Role of Starch Molecular Structure. Food Chemistry 2022, 368, 130806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Prediction of the Postprandial Blood Sugar Response Estimated by Enzymatic Kinetics of In Vitro Digestive and Fine Molecular Structure of Artocarpus Heterophyllus Lam Seed Starch and Several Staple Crop Starches. Starch - Stärke 2019, 71, 1800351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Jiang, B.; Cui, S.W.; Zhang, T.; Jin, Z. Slowly Digestible Starch–A Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2015, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xie, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, K.; Huang, C. A Study of Starch Resources with High-Amylose Content from Five Chinese Mutant Banana Species. Frontiers in Nutrition.

- Kajubi, A.; Baingana, R.; Matovu, M.; Katwaza, R.; Kubiriba, J.; Namanya, P. Variation and Abundance of Resistant Starch in Selected Banana Cultivars in Uganda. Foods 2024, 13, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, M.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Qi, B.; Li, Y. The Effect of Salt Ion on the Freeze-Thaw Stability and Digestibility of the Lipophilic Protein-Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose Emulsion. LWT 2021, 151, 112202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokocha, L.M.; Senan, C.; Williams, P.A. Structural, Physicochemical and Rheological Characterization of Tacca Involucrata Starch. Carbohydrate Polymers 2011, 86, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Lewille, B.; Haesaert, G.; Eeckhout, M. Characterization and Comparative Study on Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Buckwheat Starch from 12 Varieties. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 137, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawoye, B.; Fagbohun, O.F.; Popoola, O.O.; Gbadamosi, S.O.; Akanbi, C.T. Understanding How Different Modification Processes Affect the Physiochemical, Functional, Thermal, Morphological Structures and Digestibility of Cardaba Banana Starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 201, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, F.; He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhu, K.; Li, S.; Wu, G.; Tan, L. Jackfruit Starch: Composition, Structure, Functional Properties, Modifications and Applications. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 107, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Zhao, N.; Jiang, F.; Ji, X.; Feng, B.; Liang, J.; Yu, X.; Du, S. Structure, Physicochemical, Functional and in Vitro Digestibility Properties of Non-Waxy and Waxy Proso Millet Starches. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 224, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Physicochemical Properties and Digestibility of Endosperm Starches in Four Indica Rice Mutants. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Ying, Y.; Qian, L.; Bao, J. Physicochemical Characteristics of Tea Seed Starches from Twenty-Five Cultivars. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 275, 133570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Gao, W.; Kang, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, P.; Yan, S.; Yu, B.; Guo, L.; Cui, B.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Structural Changes in Corn Starch Granules Treated at Different Temperatures. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 118, 106760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Solis, V.; Sanchez-Ambriz, S.L.; Hamaker, B.R.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Fine Structural Characteristics Related to Digestion Properties of Acid-treated Fruit Starches. Starch Stärke 2011, 63, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Z.; Jane, J. Characterization and Modeling of the A- and B-Granule Starches of Wheat, Triticale, and Barley. Carbohydrate Polymers 2007, 67, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Guo, K.; Zhang, B.; Wei, C. Comparison of Physicochemical Properties of Very Small Granule Starches from Endosperms of Dicotyledon Plants. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 154, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudheesh, C.; Varsha, L.; Sunooj, K.V.; Pillai, S. Influence of Crystalline Properties on Starch Functionalization from the Perspective of Various Physical Modifications: A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 280, 136059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Han, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, D.; Jiang, C.; Li, Q.; Hu, Y.; Xiang, X. The High Molecular Weight and Large Particle Size and High Crystallinity of Starch Increase Gelatinization Temperature and Retrogradation in Glutinous Rice. Carbohydrate Polymers 2025, 348, 122756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Guo, K.; Xu, X.; Lin, L.; Bian, X.; Wei, C. Physicochemical Properties of Starches from Sweet Potato Root Tubers Grown in Natural High and Low Temperature Soils. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 22, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, T.; Xu, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, Z.; Yi, C. The Physicochemical Properties and Structure of Mung Bean Starch Fermented by Lactobacillus Plantarum. Foods 2024, 13, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Kan, J.; Zhang, M.; Qi, X.; Li, L.; Zhao, S.; Qian, C. Study on Quality and Starch Characteristics of Powdery and Crispy Lotus Roots. Foods 2024, 13, 3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, H. The Effects of High-Pressure Treatment on the Structure, Physicochemical Properties and Digestive Property of Starch - A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 244, 125376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junejo, S.A. Starch Structure and Nutritional Functionality – Past Revelations and Future Prospects. Carbohydrate Polymers 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, S.; Nishitsuji, Y.; Hayakawa, K.; Shi, Y.-C. Pasting Properties of A- and B-Type Wheat Starch Granules and Annealed Starches in Relation to Swelling and Solubility. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 261, 129738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Cui, C.; Gao, L.; Qin, Y.; Ji, N.; Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Shi, R.; Sun, Q. A Review of Starch Swelling Behavior: Its Mechanism, Determination Methods, Influencing Factors, and Influence on Food Quality. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 321, 121260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Kong, S.; Li, X.; Peng, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, J. Insight into Characteristics in Rice Starch under Heat- Moisture Treatment: Focus on the Structure of Amylose/Amylopectin. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 24, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamadevan, V.; Bertoft, E. Observations on the Impact of Amylopectin and Amylose Structure on the Swelling of Starch Granules. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 103, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bai, B.; Pan, Y.; Li, X.-M.; Cheng, J.-S.; Chen, H.-Q. Effects of Pectin with Different Molecular Weight on Gelatinization Behavior, Textural Properties, Retrogradation and in Vitro Digestibility of Corn Starch. Food Chemistry 2018, 264, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Yang, R.; Liu, C.; Luo, S.; Chen, J.; Hu, X.; Wu, J. Improvement in Freeze-Thaw Stability of Rice Starch Gel by Inulin and Its Mechanism. Food Chemistry 2018, 268, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R.; Hughes, T.; Chung, H.J.; Liu, Q. Composition, Molecular Structure, Properties, and Modification of Pulse Starches: A Review. Food Research International 2010, 43, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, B.A.; Workneh, T.S.; Oke, M.O. Effect of Hydrothermal Modifications on the Functional, Pasting and Morphological Properties of South African Cooking Banana and Plantain. CyTA - Journal of Food 2016, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Demiate, I.M.; Figueroa, A.M.; Zortéa Guidolin, M.E.B.; Rodrigues Dos Santos, T.P.; Yangcheng, H.; Chang, F.; Jane, J. Physicochemical Characterization of Starches from Dry Beans Cultivated in Brazil. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 61, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falade, K.O.; Okafor, C.A. Physicochemical Properties of Five Cocoyam (Colocasia Esculenta and Xanthosoma Sagittifolium) Starches. Food Hydrocolloids 2013, 30, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Adeloye, A.A.; Olaomo, O.O.; Kayitesi, E. Effect of Fermentation Time on Physicochemical Properties of Starch Extracted from Cassava Root. Food Bioscience 2020, 33, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.-H.; Tang, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M.; Jia, X.; Cheng, Y. Insights into the Textural Properties and Starch Digestibility on Rice Noodles as Affected by the Addition of Maize Starch and Rice Starch. LWT 2023, 173, 114265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhu, K.; Wu, G.; Tan, L. Functional Properties and Utilization of Artocarpus Heterophyllus Lam Seed Starch from New Species in China. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 107, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Song, X.; Chen, J.; Ji, X.; Yan, Y. Effect of Oat Beta-Glucan on Physicochemical Properties and Digestibility of Fava Bean Starch. Foods 2024, 13, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuris, A.; Hardacre, A.K.; Goh, K.K.T.; Matia-Merino, L. The Role of Calcium in Wheat Starch-Mesona Chinensis Polysaccharide Gels: Rheological Properties, in Vitro Digestibility and Enzyme Inhibitory Activities. LWT 2019, 99, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Venkatachalam, M.; Hamaker, B.R. Structural Basis for the Slow Digestion Property of Native Cereal Starches. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 3259–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Xing, B.; Liang, Y.; Zou, L.; Li, M.; Fan, X.; Ren, G.; Zhang, L.; Qin, P. Effects of Extrusion on Structural Properties, Physicochemical Properties and in Vitro Starch Digestibility of Tartary Buckwheat Flour. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 135, 108197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumoy, H.; Raes, K. In Vitro Starch Hydrolysis and Estimated Glycemic Index of Tef Porridge and Injera. Food Chemistry 2017, 229, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoft, E.; Annor, G.A.; Shen, X.; Rumpagaporn, P.; Seetharaman, K.; Hamaker, B.R. Small Differences in Amylopectin Fine Structure May Explain Large Functional Differences of Starch. Carbohydrate Polymers 2016, 140, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourilekshmi, S.S.; Jyothi, A.N.; Sreekumar, J. Physicochemical and Structural Properties of Starch from Cassava Roots Differing in Growing Duration and Ploidy Level. Starch Stärke 2020, 72, 1900237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Moisture/% | Protein/(%, db) | Fat/(%, db) | Ash/(%, db) | Total starch/(%, db) | Amylose content/(%, db) |

| NS | 2.85±0.01a | 0.30±0.03a | 0.15±0.01c | 0.13±0.00a | 95.11±0.18bc | 30.42±0.77c |

| DS | 2.20±0.00d | 0.18±0.00b | 0.16±0.00c | 0.07±0.01b | 98.59±0.92a | 49.94±0.15b |

| GS | 2.38±0.02c | 0.16±0.04b | 0.25±0.06b | 0.08±0.02b | 94.16±0.96c | 21.97±0.31d |

| OS | 2.25±0.02d | 0.21±0.04ab | 0.16±0.01c | 0.12±0.00a | 96.30±0.14b | 30.67±0.09c |

| HS | 2.47±0.00b | 0.21±0.10ab | 0.42±0.03a | 0.08±0.02b | 95.41±0.50bc | 55.46±0.60a |

| Properties | Sample | ||||

| NS | DS | GS | OS | HS | |

| To(℃) | 60.22±1.02a | 58.26±0.57b | 57.41±0.10bc | 57.11±0.16c | 53.31±0.33d |

| Tp(℃) | 65.53±0.52a | 63.37±0.12b | 63.03±0.20b | 61.34±0.13c | 57.33±0.11d |

| Tc(℃) | 76.32±0.13a | 69.85±0.42b | 68.50±0.08c | 66.85±0.09d | 62.82±0.19e |

| To~Tc(℃) | 16.10±0.98a | 11.59±0.91b | 11.09±0.09b | 9.73±0.09c | 9.51±0.17c |

| ΔH/(J·g–1) | -12.40±0.14d | -5.95±0.07a | -7.83±0.08c | -7.59±0.16b | -7.48±0.15b |

| Peak viscosity(cP) | 6567.50±17.68b | 5895.00±97.58d | 6803.50±50.20a | 6447.50±135.06b | 6203.50±43.13c |

| Trough viscosity(cP) | 4066.50±0.71b | 3540.00±15.56c | 4067.00±15.56b | 4148.50±21.92a | 2893.00±33.94d |

| Breakdown(cP) | 2538.00±35.36bc | 2355.00±86.27cd | 2719.50±89.80b | 2295.00±140.01d | 3310.00±111.72a |

| Final viscosity(cP) | 4521.00±11.31b | 4380.00±26.87c | 4577.00±1.41a | 4607.00±29.70a | 3848.00±26.87d |

| Setback viscosity(cP) | 463.50±0.71c | 840.00±32.53b | 510.00±14.14c | 459.00±31.11c | 955.00±43.84a |

| Peak time(min) | 4.73±0.01a | 4.17±0.03c | 4.50±0.04b | 4.60±0.04ab | 4.00±0.16c |

| Setback viscosity(℃) | 74.30±0.07b | 76.70±0.85a | 73.10±0.57b | 74.15±0.85b | 69.40±0.71c |

| Hardness | 148.36±1.72d | 245.02±6.48b | 192.60±9.47c | 188.32±8.36c | 298.89±13.30a |

| Adhesiveness (g.s–1) | -467.45±35.56b | -429.07±42.13b | -438.22±42.43b | -165.67±22.51a | -458.20±26.34b |

| Springiness | 0.84±0.00c | 0.98±0.02ab | 0.84±0.04c | 0.98±0.02a | 0.88±0.07bc |

| Cohesiveness (g) | 0.47±0.01a | 0.43±0.01ab | 0.46±0.02a | 0.40±0.03b | 0.41±0.02b |

| Gumminess (g) | 70.01±0.31a | 106.94±0.59b | 87.48±0.32c | 75.80±0.23d | 121.73±0.22a |

| Cohesiveness | 59.04±0.20c | 105.80±1.65a | 73.50±3.38b | 74.64±0.31b | 107.93±0.64a |

| Resilience (g) | 0.07±0.00a | 0.08±0.00a | 0.06±0.01a | 0.06±0.01a | 0.07±0.03a |

| Sample | C∞(%) | k1×10-2(min-1) | k2×10-2(min-1) | RDS (%) | SDS (%( | RS (%) | eGI |

| NS | 12.25±0.07b | 2.84±0.55b | 1.11±0.09b | 3.06±0.00b | 7.31±0.04ab | 89.63±0.04b | 58.81±0.04c |

| DS | 9.44±0.30c | 0.51±0.13e | 1.23±0.12a | 1.81±0.31c | 5.13±0.05c | 93.05±0.08a | 53.44±0.39d |

| GS | 12.86±0.19b | 4.19±0.68a | 0.72±0.07e | 3.14±0.00ab | 7.22±0.22b | 89.64±0.22c | 58.77±0.28c |

| OS | 14.34±0.20a | 1.92±0.22d | 0.92±0.04d | 3.58±0.34a | 8.12±0.27a | 88.30±0.07b | 62.92±0.45a |

| HS | 12.83±0.56b | 2.20±0.39c | 0.99±0.07c | 3.32±0.27ab | 7.63±0.14b | 89.05±0.14b | 60.62±0.35b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).