1. Introduction

Age is a major risk factor for the pathogenesis of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), which is the most common form of glaucoma [

1,

2]. POAG is caused by a restriction in the movement of aqueous humor (AH) fluid through the layers of the trabecular meshwork (TM) into Schlemm’s canal (SC) [

3,

4]. The restricted outflow of AH causes an elevation in intraocular pressure (IOP), which over time irreversibly damages the optic nerve and causes blindness. Age-related changes in the composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the biomechanical compliance of the TM are thought to contribute to the reduction of AH flow and elevated IOP [

5,

6,

7]. Yet, the mechanisms that trigger these changes remain unclear.

Changes in the ECM are sensed by various mechanosensory receptors on the TM cell surface, including a family of receptors called integrins. Integrins are transmembrane heterodimeric proteins consisting of an α and β subunit. At least 12 different integrins have been identified by either RNA or protein analysis in the TM/SC outflow pathway. In the TM/SC, integrins are found along the trabecular beams, in the juxtacanalicular region (JCT), and in cells along the inner wall of SC [

8,

9,

10]. Most of the integrins appear to be ubiquitously expressed throughout all the cells in the TM/SC. However, some integrins show restricted expression patterns. Most notably, α6β1 and α9β1 integrins are found predominantly on cells lining the inner wall of SC [

11,

12,

13]. Whether the expression patterns of integrins in the TM/SC change as we age is unclear. One early study using tissues obtained from donors 2 to 65 yrs old suggested that the pattern of integrin expression did not change [

14]. However, another study indicated that the expression of the α5 integrin subunit may be downregulated in the TM/SC of older human eyes [

15], which is consistent with that observed in other adult tissues [

16]. Neither of these studies determined the activity of integrins.

A unique feature of integrins is that their activity is tightly regulated and rapidly fluctuates between an active and inactive state within sub-seconds on the cell surface [

17,

18,

19]. Thus, not every integrin is active on the cell surface at the same time. This enables integrins to rapidly change their activity in response to changes in their microenvironment. The activity of an integrin is dependent on its conformation. Numerous studies have shown that an unoccupied integrin on the cell surface is in a low affinity, bent conformation with the cytoplasmic tails of the α and β subunits bound together by a salt bridge [

20]. In contrast, the active integrin assumes an upright conformation and the α and β cytoplasmic tails become separated, allowing binding of cytoplasmic proteins and high affinity interactions with ECM proteins [

21].

The activity of integrins is controlled by specific cytoplasmic and membrane proteins and mechanical forces (stretch and shear stress) [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], making them likely to be activated when shear stress is elevated by high IOP [

4]. Once activated, integrins trigger actin structures that control the contractile properties of cells and regulate the activity of signaling pathways associated with endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT), fibrosis, TGFβ signaling, and senescence [

27].

Several studies have shown that activation of the αvβ3integrin contributes to the fibrogenic phenotype of the TM/SC [

28]. Activation of αvβ3 integrin drives the formation of cross-linked actin networks (CLANs) [

29,

30,

31], the deposition of both EDA+ isoforms of fibronectin into the ECM [

32], and expression of TGFβ2 [

33], which are associated with POAG and glucocorticoid-induced glaucoma [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. αvβ3integrin also regulates the distribution of a cytoplasmic protein Hic-5, which induces fibrogenic activity in TM cells [

39]. Finally, activation of αvβ3 integrin has been shown to affect IOP and outflow facility in organ cultured anterior segments of porcine eyes and C57BL/6J mice [

10]. Together, these studies provide strong evidence that activating αvβ3integrin leads to profibrotic-like changes in the TM associated with an elevated IOP.

However, the molecular events that trigger activation of αvβ3integrin and induction of these fibrogenic pathways that ultimately lead to POAG are yet to be elucidated. In this study, we investigated the age-dependent expression of integrins and correlated these changes with integrin activity, cellular contractile properties, and assembly of fibronectin fibrils in human TM cells isolated from young and old normal donor eyes. This study shows that TM cells isolated from old donor eyes have lower levels of α5β1 integrin expression compared to TM cells isolated from younger donor eyes. This decrease in the expression of α5β1 integrin is accompanied by an increase in the activity of αvβ3 integrin. Older TM cells are also significantly more contractile, express higher levels of αSMA mRNA, assemble αSMA+ stress fibers, and form more focal adhesions containing activated αvβ3 integrin. Cultures of older TM cells also assemble more EDA+ and EDB+ isoforms of fibronectin into the ECM. These phenotypes are consistent with old TM cells initiating EndoMT and inducing fibrogenic pathways that may ultimately lead to development of fibrotic-like glaucomatous TM.

4. Discussion

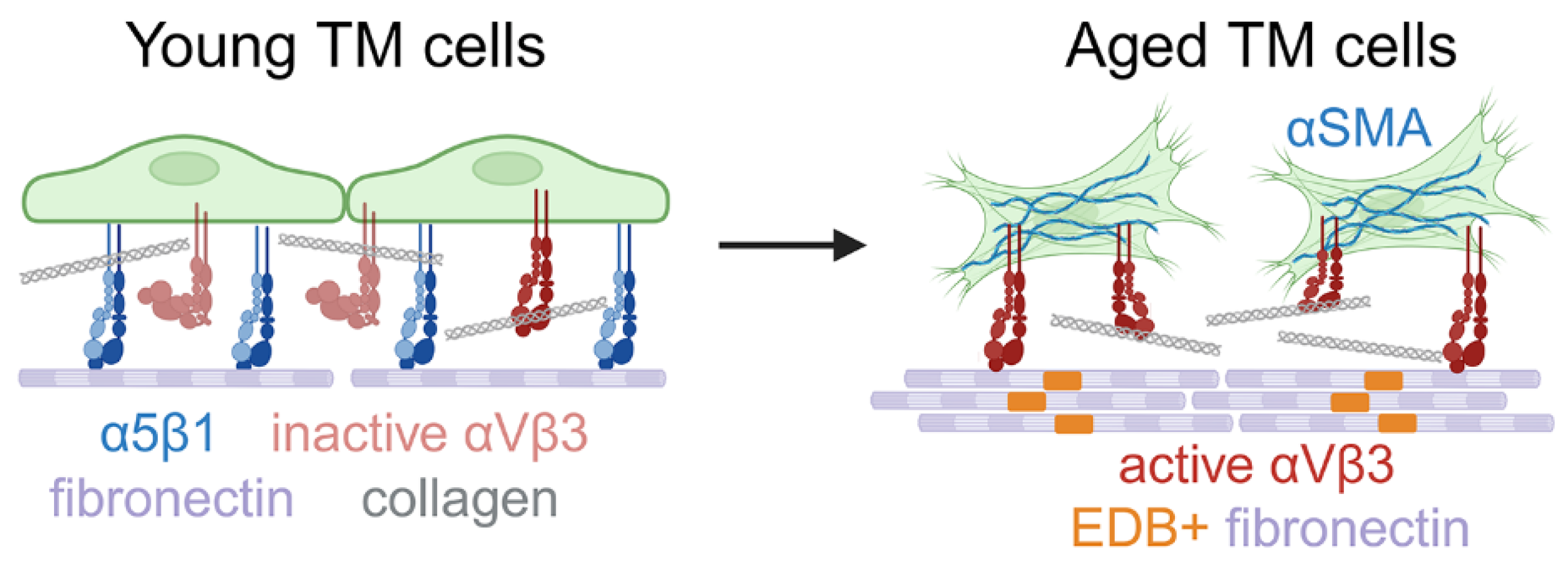

In this study, we showed that the expression profile of α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins in human TM cells and tissues changes with aging and this affects the contractile properties of TM cells. We also found that a decrease in the expression of α5 integrin subunit in old individuals appears to trigger an increase in the activity of αvβ3 integrin. This gain-of-function in αvβ3 integrin activity is associated with a statistically significant increase in the assembly of αSMA+ stress fibers, an increase in αSMA mRNA levels, the appearance of activated αvβ3 integrins in focal adhesions, and increased levels of the EDB+ isoform of fibronectin. This suggests that an age-related switch in integrin signaling alters the contractile properties of old TM cells and may be an early step in triggering the fibrogenic pathways associated with EndoMT in the aged TM/SC (

Figure 8).

Interestingly, activation of αvβ3 integrin is believed to be a prerequisite for the formation of αSMA-containing stress fibers during the differentiation of myofibroblasts [

52], which leads to the development of epithelial mesenchyme transition (EMT) and EndoMT [

54,

55]. Given that EndoMT is believed to contribute to the increased rigidity of the TM/SC tissue and alter the pressure-dependent contractile properties of the TM/SC pathway to control IOP [

4], this suggests that a switch in activity from α5β1 to αvβ3 integrin likely contributes to the pathogenesis of the contractile-fibrotic phenotype that is characteristic of POAG.

In addition to causing an increase in αvβ3 integrin activity and contractility, an age-related decrease in α5-integrin could interfere with a TM cell’s ability to detect IOP-induced biomechanical changes to the ECM. Our previous study showed that α5β1 integrins are localized at the tips of filopodia in TM cells [

56], while αvβ3 integrins are located at discrete areas along the filopodial shaft as well as the tip. Filopodia are highly dynamic, mechanosensing cellular structures that extend from the cell surface and form transient adhesions with the ECM as a way to probe a cells microenvironment. The localization of α5β1 integrin at these tips suggest that α5β1 integrin is needed to form these transient adhesions and promote filopodia elongation in TM cells. Hence, a loss of α5β1 integrin in the aged TM would reduce the capacity for cells to detect IOP-induced changes to the microenvironment.

What causes the decrease in α5 integrin expression in the TM is still unknown. In human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, as well as human and rabbit corneal epithelial cells, expression of the α5 integrin subunit and its promoter activity is downregulated as the cells become quiescent [

57] due to an apparent alteration in the ratio of transcription factors that activate or repress α5 integrin expression [

58,

59]. This relationship between age-related diseases and expression of transcriptions factors is well established [

60,

61] and could represent an early step in the development of POAG.

Our studies further suggest that there is a certain level of inactive αvβ3 integrin existing on the TM cell surface and that a decrease in expression of α5β1 integrin may be contributing to the activation of those αvβ3 integrins. By flow cytometry and immunofluorescence microscopy, we could not detect any differences in the levels of total αvβ3 integrin expression on the cell surface or in focal adhesions between young and old TM cell strains. Yet, in older TM cells expressing lower levels less α5β1 integrin, there was a noticeable increase in the level of active αvβ3 integrins in focal adhesions (

Figure 6G) and on the cell surface of older cells (Fig. S4). The cause for this increase is unknown. A unique function of integrins is that their expression and activity is tunable within subseconds in a spatiotemporal manner [

62,

63,

64]. This occurs in response to biomechanical changes in their microenvironment and the expression of other integrins [

17,

65,

66,

67]. Hence, a change in α5 integrin expression could be triggering the increase in αvβ3 integrin activity.

A switch in integrin signaling caused by a change in the expression of another integrin is not unexpected and could trigger the increase in αvβ3 integrin activity in old TM cells [

68]. Studies in K562 erythroleukemia cells showed that expression of αvβ3 integrin inhibited α5β1 integrin activity [

69]. Studies in a β1-null GD25 mouse embryonic fibroblast line showed that the αvβ3 integrin took over the role of β1 integrins in mediating focal adhesion formation and re-expression of the β1 subunit reversed the effect [

70]. More recently, this phenomenon has been observed to occur in cancer tissues [

71] and to be associated with EMT in cancer cells, a transition similar to EndoMT [

72]. Together, these studies show that crosstalk between integrin subunits regulates their expression and/or activity.

In the TM, a gain in αvβ3 integrin activity could contribute to the pathogenesis of the fibrotic phenotype characteristic of EndoMT associated with aging TM/SC tissues and POAG (2, 7, 48). An increase in αvβ3 integrin activity has been shown to drive expression of TGFβ2 in TM cells [

33], promote the formation of CLANs [

29,

30], and enhance fibronectin fibrillogenesis [

32], which are upregulated in POAG. αvβ3 integrin is also a receptor for connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in TM cells [

73], which is involved in up-regulating expression of ECM proteins in fibrosis [

74]. αvβ3 integrin is also associated with senescence in human diploid fibroblasts [

75] which is reported to occur in glaucomatous TM [

76]. Thus, an increase in αvβ3integrin activity may enhance the susceptibility of people to develop glaucoma.

Although previous studies have noticed age-related changes in α5β1 integrin expression in quiescent cultures of RPE cells [

57], and HT1080 human fibrosarcoma fibroblasts [

77], to date only one other study has reported an age-related change in integrin expression in the TM [

15]. Interestingly, α5β1 integrins also appeared to be absent in the RPE

in vivo in tissue from older individuals (>50 yrs old), suggesting an age-related downregulation in the retina [

78]. Further studies are needed to investigate whether additional ocular tissues show a similar age-related decrease in α5β1 integrin expression.

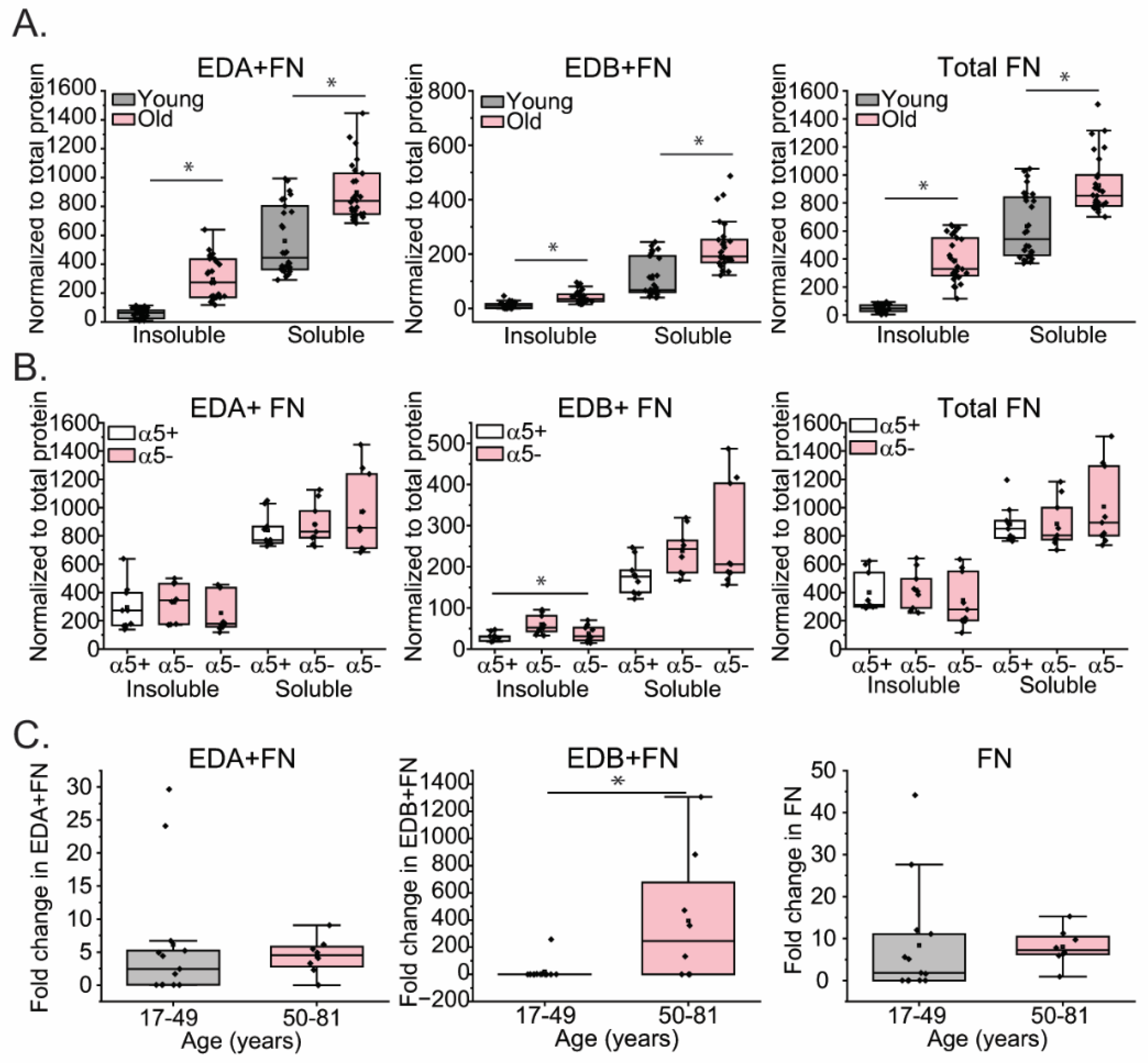

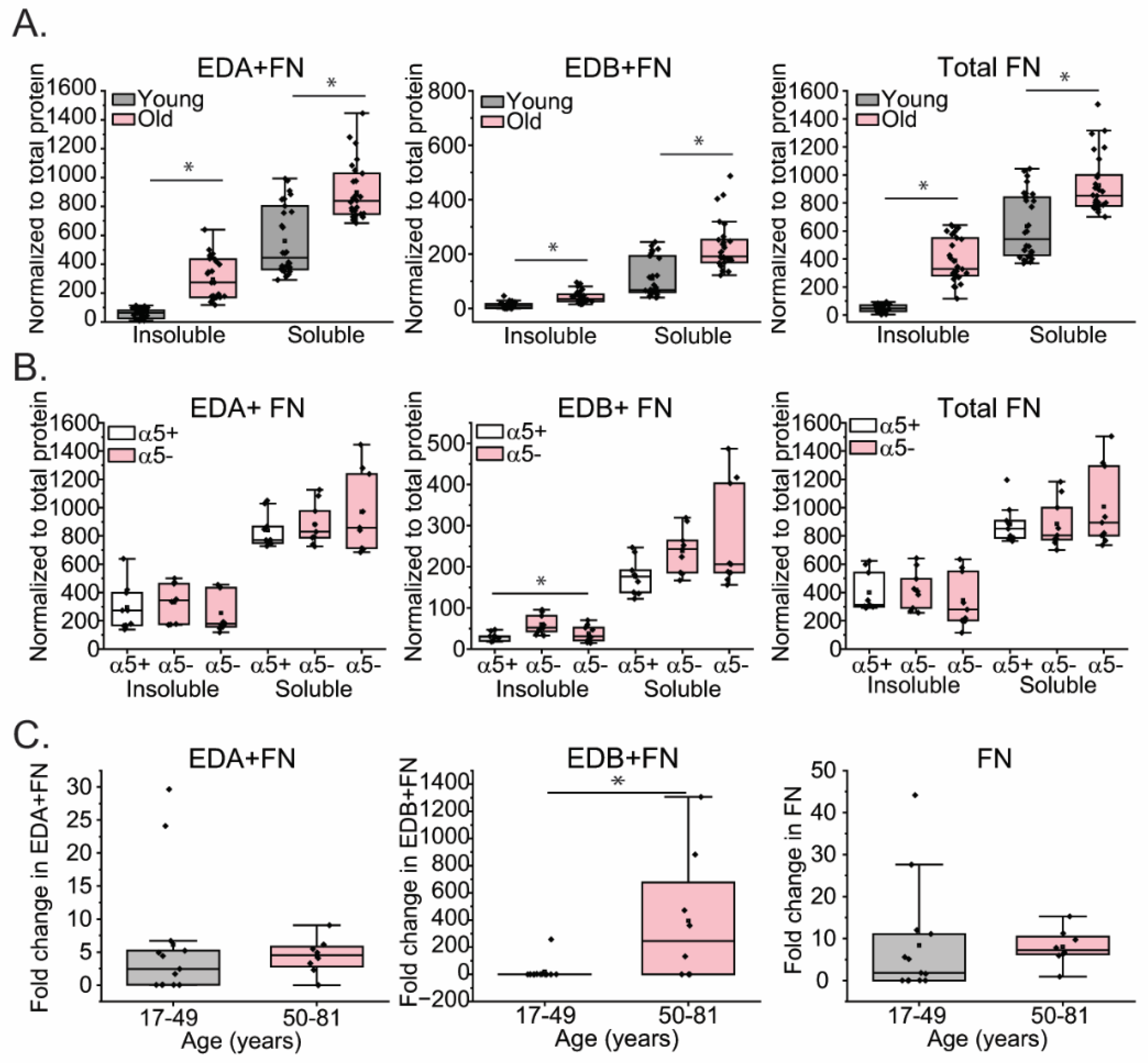

These studies also observed an increase in the formation of an insoluble fibronectin matrix in old TM cell strains. However, this did not appear to be due to a loss of the α5 integrin subunit since the old α5-positive N75 cell strain also showed these changes. Interestingly, we also saw increased expression of the EDB+ isoform of fibronectin in the matrix as well as EDA+fibronectin. The expression of EDB+ fibronectin is intriguing since it has been observed to occur in stiffer ECMs as a result of enhanced alternative splicing of fibronectin [

79]. This suggests that the ECM made by old TM cells may be stiffer. In addition, since EDB+ fibronectin appears to be upregulated in TM cell cultures overexpressing a constitutively active αvβ3 integrin [

32], and EDB+ fibronectin binds and activates the αvβ3 integrin [

80], this suggests that activation of αvβ3 integrin and expression of EDB+ fibronectin may be connected. Whether activation of αvβ3 integrin is responsible for EDB+ fibronectin expression, or vice versa, remains to be determined.

In summary, these studies suggest that an age-related dysregulation of α5β1 and αvβ3 integrin signaling may represent a key early event in inducing the transition into an αSMA-producing, myofibroblast-like, contractile TM cell. Interestingly, this switch did not occur in all the old cell strains we examined. Future studies examining integrin profiles in glaucomatous tissues, and factors controlling the downregulation of α5β1 integrin expression in the TM, should enhance our understanding of why some older individuals are more susceptible to developing this phenotype and its role in POAG.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.E.K. and D.M.P.; funding acquisition, K.E.K. and D.M.P., formal analysis, K.L.J., J.A.F., M.S.F. and N. S. S., methodology, K.L.J., J.A.F., M.S.F., Y.Y.S., K.E.K. and D.M.P. ; validation, K.L.J., J.A.F. and M.S.F.; investigation, K.L.J., J.A.F. M.S.F. and Y.Y.S.; resources, K.E.K. and D.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.J., J.A.F., M.S.F., K.E.K. and D.M.P.; writing—review and editing, K.L.J., J.A.F., M.S.F., K.E.K. and D.M.P.; visualization, K.L.J., J.A.F., M.S.F. and K.E.K.; supervision, K.E.K. and D.M.P.; project administration, K.E.K. and D.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

An age-related loss of α5 integrin subunit is seen in 2 out of 3 old TM cell strains. Flow cytometry for α5, β3, and β1 integrin subunits was done on two young cell strains (N17, N27) and three old cell strains (N74, N75 and N77). Blue peaks are cells labeled with control IgG, while pink peaks are cells labeled with either P1D6 mAb (α5 integrin; top panels), LM609 mAb (β3 integrin subunit; middle panels), or 12G10 (β1 integrin; bottom panels). In contrast to young TM cells, α5 integrin labeling is not above background in two of the old TM cells (N74 and N77), indicating that α5 integrin levels on the cell surface are lower. The third old cell strain (N75) had similar levels of α5 integrin as the two young cell strains (N17 and N27). Both young and old TM cells express similar levels of the β3 and β1 integrin subunits (middle and bottom panels, respectively).

Figure 1.

An age-related loss of α5 integrin subunit is seen in 2 out of 3 old TM cell strains. Flow cytometry for α5, β3, and β1 integrin subunits was done on two young cell strains (N17, N27) and three old cell strains (N74, N75 and N77). Blue peaks are cells labeled with control IgG, while pink peaks are cells labeled with either P1D6 mAb (α5 integrin; top panels), LM609 mAb (β3 integrin subunit; middle panels), or 12G10 (β1 integrin; bottom panels). In contrast to young TM cells, α5 integrin labeling is not above background in two of the old TM cells (N74 and N77), indicating that α5 integrin levels on the cell surface are lower. The third old cell strain (N75) had similar levels of α5 integrin as the two young cell strains (N17 and N27). Both young and old TM cells express similar levels of the β3 and β1 integrin subunits (middle and bottom panels, respectively).

Figure 2.

RT-qPCR analysis of α5, β1, and β3 integrin mRNA levels. (A) mRNA levels for α5 integrin subunit are statistically higher in TM cells from young donor eyes (gray) compared to levels found in TM cells from old donor eyes (pink). (B, C) In contrast, levels of β3 and β1 integrin subunits mRNA are decreased in TM cells from young donor eyes compared to cells from old donor eyes. Changes are statistically significant (*p<0.05). N=13 biological replicates for young TM cells, N=8 for old cells.

Figure 2.

RT-qPCR analysis of α5, β1, and β3 integrin mRNA levels. (A) mRNA levels for α5 integrin subunit are statistically higher in TM cells from young donor eyes (gray) compared to levels found in TM cells from old donor eyes (pink). (B, C) In contrast, levels of β3 and β1 integrin subunits mRNA are decreased in TM cells from young donor eyes compared to cells from old donor eyes. Changes are statistically significant (*p<0.05). N=13 biological replicates for young TM cells, N=8 for old cells.

Figure 3.

Immunolabeling for α5 integrin in anterior segments from young and old eyes. (A) Location of the TM in the angle of the anterior segment. (B) Schematic of the TM showing that it consists of several layers of fenestrated beams covered by a monolayer of TM cells. This is followed by a region called the juxtacanalicular (JCT) region which is composed of individual cells embedded in an ECM. This is the region where most of the outflow resistance lies due to fibrotic changes that occur during POAG. Aqueous humor (AH, arrows) flows into the TM from the anterior chamber (AC) and exits through the inner wall (IW) of Schlemm’s canal (SC) to the distal vessels (DV). (C) An H&E-stained section showing the typical morphology of the TM in a section of the anterior segment from a 36-yr-old donor eye. Scale bar = 50 µm. (D-I) Sections of anterior segments from 21 yr old (D-F) and 74 yr old (G-I) donor eyes. Sections were labeled with mAb 10F6 against α5 integrin (D, F, G, I), or a control antibody against β-galactosidase (E, H). Asterisks in panels D and G show regions that are at higher magnification in panels F and I, respectively. α5 integrin labeling is ubiquitous within the TM beam cells and JCT in the 21-yr-old tissue, but is greatly reduced or scattered within the beam cells and JCT from the 74-yr-old tissue. Both young and old tissue samples show α5 integrin labeling along the SC indicating that the loss of α5 integrin is specific to TM cells. In both young and old tissue samples, the α5 integrin labeling is clearly above the background labeling. Arrows = TM beam cell labeling; arrowheads = SC endothelium labeling. AC = anterior chamber; JCT = juxtacanalicular tissue. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 3.

Immunolabeling for α5 integrin in anterior segments from young and old eyes. (A) Location of the TM in the angle of the anterior segment. (B) Schematic of the TM showing that it consists of several layers of fenestrated beams covered by a monolayer of TM cells. This is followed by a region called the juxtacanalicular (JCT) region which is composed of individual cells embedded in an ECM. This is the region where most of the outflow resistance lies due to fibrotic changes that occur during POAG. Aqueous humor (AH, arrows) flows into the TM from the anterior chamber (AC) and exits through the inner wall (IW) of Schlemm’s canal (SC) to the distal vessels (DV). (C) An H&E-stained section showing the typical morphology of the TM in a section of the anterior segment from a 36-yr-old donor eye. Scale bar = 50 µm. (D-I) Sections of anterior segments from 21 yr old (D-F) and 74 yr old (G-I) donor eyes. Sections were labeled with mAb 10F6 against α5 integrin (D, F, G, I), or a control antibody against β-galactosidase (E, H). Asterisks in panels D and G show regions that are at higher magnification in panels F and I, respectively. α5 integrin labeling is ubiquitous within the TM beam cells and JCT in the 21-yr-old tissue, but is greatly reduced or scattered within the beam cells and JCT from the 74-yr-old tissue. Both young and old tissue samples show α5 integrin labeling along the SC indicating that the loss of α5 integrin is specific to TM cells. In both young and old tissue samples, the α5 integrin labeling is clearly above the background labeling. Arrows = TM beam cell labeling; arrowheads = SC endothelium labeling. AC = anterior chamber; JCT = juxtacanalicular tissue. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 4.

Old TM cells are more contractile than young TM cells and express higher levels of αSMA. (A, B) Young and old TM cells were plated onto collagen gels (1.25 mg/ml) for 24 hrs. The gels were then rimmed to release them from each plate. Old cells were statistically more contractile than younger donor cells within minutes of releasing the gels. N=2 biological replicates/age grp. All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated 3 times. (C, D) By 4 h, old α5-negative TM cells are more contractile than old α5-positive TM cells. Collagen contractility assays were done as described above. All experiments were done in duplicate or triplicate. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Bars= S.E.M, (E, F) Immunofluorescent microscopy images showing that αSMA+ stress fibers were not formed in N27-2 cells from a young donor (panel E) in contrast to the N77 cells from an old donor eye (panel F). Cells were plated onto collagen-coated coverslips for 24 h and labeled with anti-αSMA antibody, as described in material and methods. White arrows indicate the αSMA+ stress fibers. Scale bar = 50 µm. (G) RT-qPCR of αSMA mRNA levels in young (gray) and old (pink) TM cells show that mRNA levels for αSMA are upregulated in old cells compared to younger cells suggesting that old cells are more contractile. *p<0.05.

Figure 4.

Old TM cells are more contractile than young TM cells and express higher levels of αSMA. (A, B) Young and old TM cells were plated onto collagen gels (1.25 mg/ml) for 24 hrs. The gels were then rimmed to release them from each plate. Old cells were statistically more contractile than younger donor cells within minutes of releasing the gels. N=2 biological replicates/age grp. All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated 3 times. (C, D) By 4 h, old α5-negative TM cells are more contractile than old α5-positive TM cells. Collagen contractility assays were done as described above. All experiments were done in duplicate or triplicate. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Bars= S.E.M, (E, F) Immunofluorescent microscopy images showing that αSMA+ stress fibers were not formed in N27-2 cells from a young donor (panel E) in contrast to the N77 cells from an old donor eye (panel F). Cells were plated onto collagen-coated coverslips for 24 h and labeled with anti-αSMA antibody, as described in material and methods. White arrows indicate the αSMA+ stress fibers. Scale bar = 50 µm. (G) RT-qPCR of αSMA mRNA levels in young (gray) and old (pink) TM cells show that mRNA levels for αSMA are upregulated in old cells compared to younger cells suggesting that old cells are more contractile. *p<0.05.

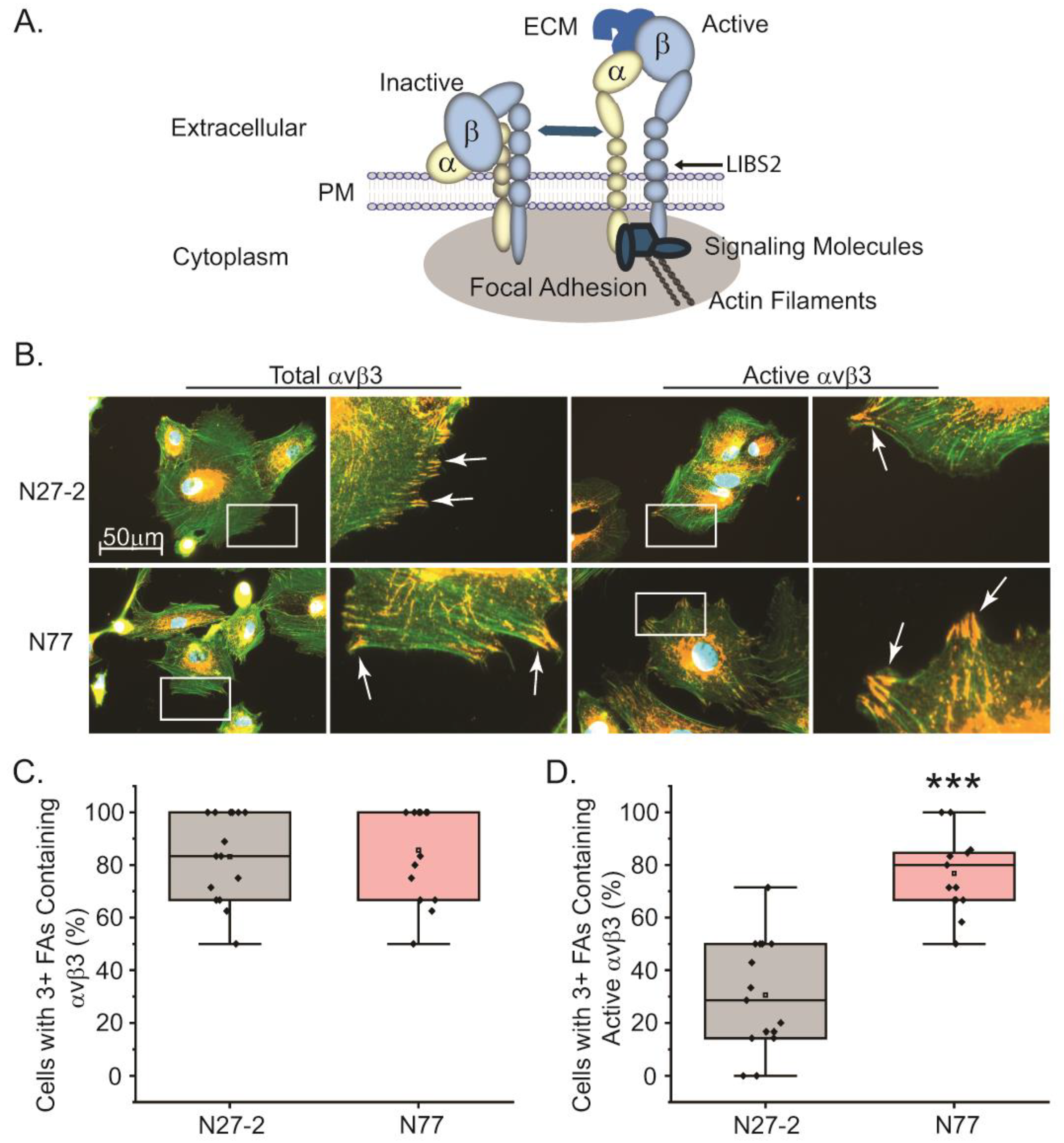

Figure 5.

Old TM cells have more focal adhesions with active αvβ3 integrin. (A) Schematic showing that integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane proteins consisting of an α and β subunits that interact with the ECM. They can exist in both an active and inactive state within the sites of contact with the ECM called focal adhesions. The active integrin has an upright conformation, can bind to ECM proteins and interact with cytoplasmic signaling molecules that trigger the assembly of actin stress filaments. (B) Young N27-2 and old N77 TM cells were labeled for total αvβ3 integrin levels (mAb [BV3]) and active αvβ3 integrin (mAb LIBS2). Both TM cell strains showed numerous focal adhesions (white arrows) containing αvβ3 integrin and some focal adhesions that were positive for active αvβ3 integrin. (C) Quantitation of number of young (gray) or old (pink) cells containing three or more focal adhesions did not show a statistical difference in the number of cells that contained αvβ3 integrin in focal adhesions. Number of N27-2 and N77 cells counted were 101 and 87, respectively. (D) In contrast, quantitation of the number of cells containing three or more focal adhesions that contained active αvβ3 integrin were statistically higher in old cells (pink) compared to young cells (gray). Number of N27-2 and N77 cells counted were 91 and 103, respectively. ***p<0.001.

Figure 5.

Old TM cells have more focal adhesions with active αvβ3 integrin. (A) Schematic showing that integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane proteins consisting of an α and β subunits that interact with the ECM. They can exist in both an active and inactive state within the sites of contact with the ECM called focal adhesions. The active integrin has an upright conformation, can bind to ECM proteins and interact with cytoplasmic signaling molecules that trigger the assembly of actin stress filaments. (B) Young N27-2 and old N77 TM cells were labeled for total αvβ3 integrin levels (mAb [BV3]) and active αvβ3 integrin (mAb LIBS2). Both TM cell strains showed numerous focal adhesions (white arrows) containing αvβ3 integrin and some focal adhesions that were positive for active αvβ3 integrin. (C) Quantitation of number of young (gray) or old (pink) cells containing three or more focal adhesions did not show a statistical difference in the number of cells that contained αvβ3 integrin in focal adhesions. Number of N27-2 and N77 cells counted were 101 and 87, respectively. (D) In contrast, quantitation of the number of cells containing three or more focal adhesions that contained active αvβ3 integrin were statistically higher in old cells (pink) compared to young cells (gray). Number of N27-2 and N77 cells counted were 91 and 103, respectively. ***p<0.001.

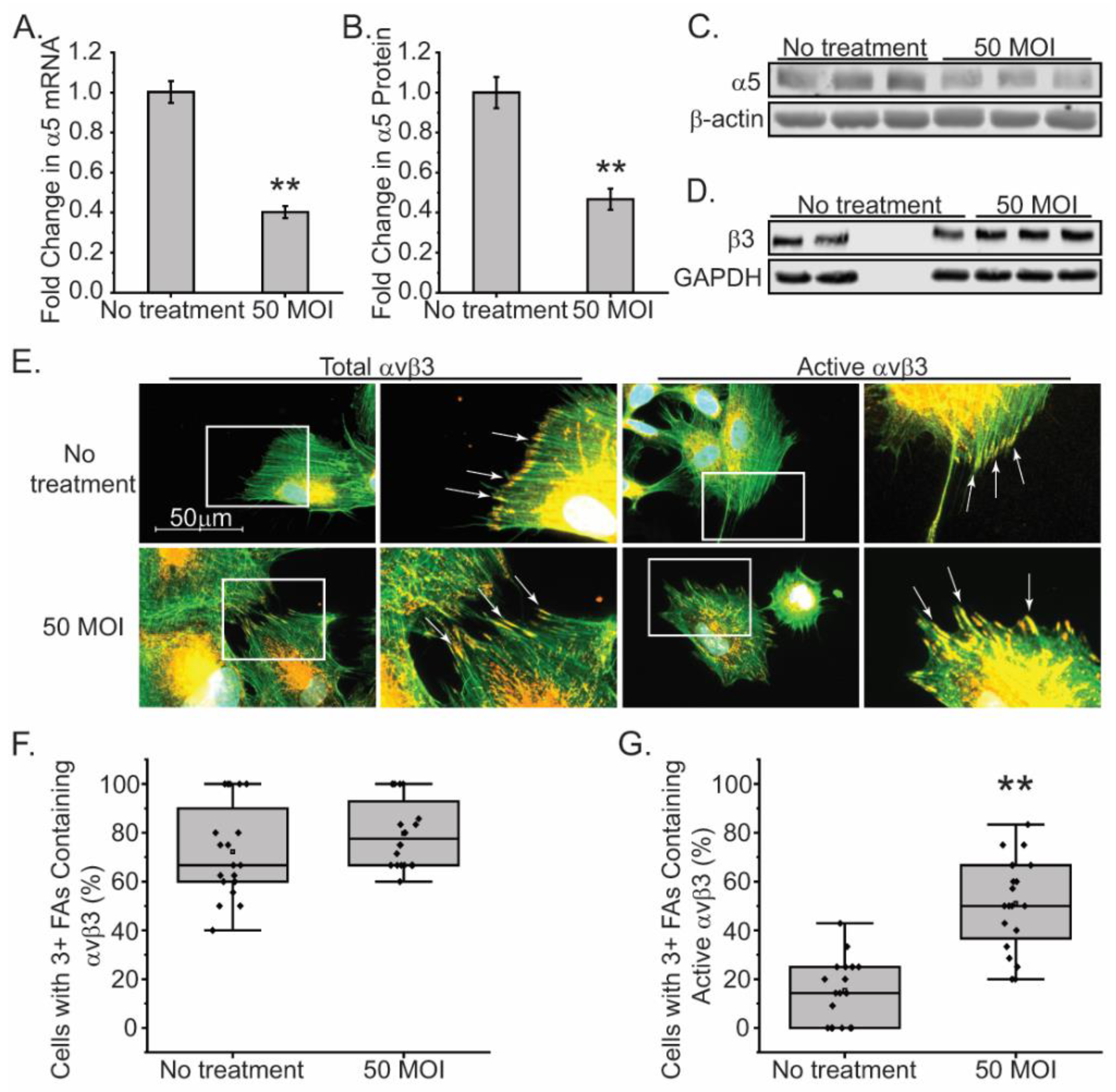

Figure 6.

Knockdown of α5 integrin subunit in young TM cells triggers an increase in β3 integrin activity. (A) N25 TM cells were transduced with a lenti-α5 shRNA viral vector (MOI 50). By RT-qPCR, there was a 60% reduction in α5 integrin mRNA compared to untransduced cells (B- C) Western blot analysis showed a 50% decrease in the α5 integrin subunit in transduced cells compared to untransduced cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Western blot analysis showed that levels of the β3 integrin subunit were unchanged when α5 integrin was knocked down. (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy of transduced and untransduced N25 cells labeled for total levels of αvβ3 integrin (mAb [BV3]), or activated αvβ3 integrin (mAb LIBS2), in focal adhesions (arrows). Cells were stained with Alexa 488 phalloidin to detect actin filaments. Scale bar = 50 µm. (F) Untransduced and transduced N25 cells with 3 or more focal adhesions show similar levels of focal adhesions containing αvβ3 integrin. The number of cells counted per treatment group ranged between 99-114 cells. (G) The number of transduced N25 TM cells with 3 or more focal adhesions containing activated αvβ3 was statistically higher compared to control cells. The number of cells counted per treatment group ranged between 99-111. **p<0.01.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of α5 integrin subunit in young TM cells triggers an increase in β3 integrin activity. (A) N25 TM cells were transduced with a lenti-α5 shRNA viral vector (MOI 50). By RT-qPCR, there was a 60% reduction in α5 integrin mRNA compared to untransduced cells (B- C) Western blot analysis showed a 50% decrease in the α5 integrin subunit in transduced cells compared to untransduced cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (D) Western blot analysis showed that levels of the β3 integrin subunit were unchanged when α5 integrin was knocked down. (E) Immunofluorescence microscopy of transduced and untransduced N25 cells labeled for total levels of αvβ3 integrin (mAb [BV3]), or activated αvβ3 integrin (mAb LIBS2), in focal adhesions (arrows). Cells were stained with Alexa 488 phalloidin to detect actin filaments. Scale bar = 50 µm. (F) Untransduced and transduced N25 cells with 3 or more focal adhesions show similar levels of focal adhesions containing αvβ3 integrin. The number of cells counted per treatment group ranged between 99-114 cells. (G) The number of transduced N25 TM cells with 3 or more focal adhesions containing activated αvβ3 was statistically higher compared to control cells. The number of cells counted per treatment group ranged between 99-111. **p<0.01.

Figure 7.

Assembly of fibronectin fibrils and expression of EDB+ isoform of fibronectin (FN) is higher in old TM cells. Expression of fibronectin and its EDA+ and EDB+ isoforms were measured in 3 young cell lines (N17, N27-2, N25) and 3 old cell lines (N74, N75, and N77) using an OCW as described in material and methods. (A) EDA+, EDB+ and total FN was significantly higher in both soluble and insoluble fractions of cell layers from old cells compared to young cells. (B) Levels of EDA+ and total FN in both soluble and insoluble fractions were similar in all three old cell lines. EDB+FN, however, was found to be significantly higher in the insoluble matrix in one α5-negative cell line (N77) compared to the α5+positive N75 old cell line. *p<0.05. N=3 biological replicates/age grp. All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated in 4 independent experiments. (C) Quantitative PCR of EDA+, EDB+ and FN mRNA levels in old (pink) and young (gray) cells show that mRNA levels for EDB+FN were significantly increased in old cell lines. *p<0.05.

Figure 7.

Assembly of fibronectin fibrils and expression of EDB+ isoform of fibronectin (FN) is higher in old TM cells. Expression of fibronectin and its EDA+ and EDB+ isoforms were measured in 3 young cell lines (N17, N27-2, N25) and 3 old cell lines (N74, N75, and N77) using an OCW as described in material and methods. (A) EDA+, EDB+ and total FN was significantly higher in both soluble and insoluble fractions of cell layers from old cells compared to young cells. (B) Levels of EDA+ and total FN in both soluble and insoluble fractions were similar in all three old cell lines. EDB+FN, however, was found to be significantly higher in the insoluble matrix in one α5-negative cell line (N77) compared to the α5+positive N75 old cell line. *p<0.05. N=3 biological replicates/age grp. All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated in 4 independent experiments. (C) Quantitative PCR of EDA+, EDB+ and FN mRNA levels in old (pink) and young (gray) cells show that mRNA levels for EDB+FN were significantly increased in old cell lines. *p<0.05.

Figure 8.

Model of integrin switching in aging TM. Young TM cells initially express both α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins on their cell surface and lack actin filaments containing αSMA. αvβ3 integrins on these young cells appear to be a mixture of both active (upright conformation) and inactive (bent conformation) integrins. As the TM cells age, there is a loss of α5β1 integrins, increased activation of αvβ3 integrin on the cell surface, and an enhancement in the contractile activities of the cells. This increased contractile activity appears to be driven by the activated αvβ3 integrin that causes initiation of mechanotransduction and an increase in αSMA+ stress fibers.

Figure 8.

Model of integrin switching in aging TM. Young TM cells initially express both α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins on their cell surface and lack actin filaments containing αSMA. αvβ3 integrins on these young cells appear to be a mixture of both active (upright conformation) and inactive (bent conformation) integrins. As the TM cells age, there is a loss of α5β1 integrins, increased activation of αvβ3 integrin on the cell surface, and an enhancement in the contractile activities of the cells. This increased contractile activity appears to be driven by the activated αvβ3 integrin that causes initiation of mechanotransduction and an increase in αSMA+ stress fibers.

Table 1.

Cells Strains used. * Presence of α5 integrin subunit determined by FACS.

Table 1.

Cells Strains used. * Presence of α5 integrin subunit determined by FACS.

| |

Donor Age |

Nomenclature Used in Paper |

Sex |

α5 integrin * |

| N25TM-8 |

25 |

N25 |

M |

positive |

| N27TM-6 |

27 |

N27 |

F |

positive |

| N27TM-8 |

27 |

N27-2 |

F |

positive |

| 2021-1493 |

74 |

N74 |

F |

negative |

| 2021-1328 |

75 |

N75 |

M |

positive |

| 2022-0140 |

77 |

N77 |

F |

negative |