1. Introduction

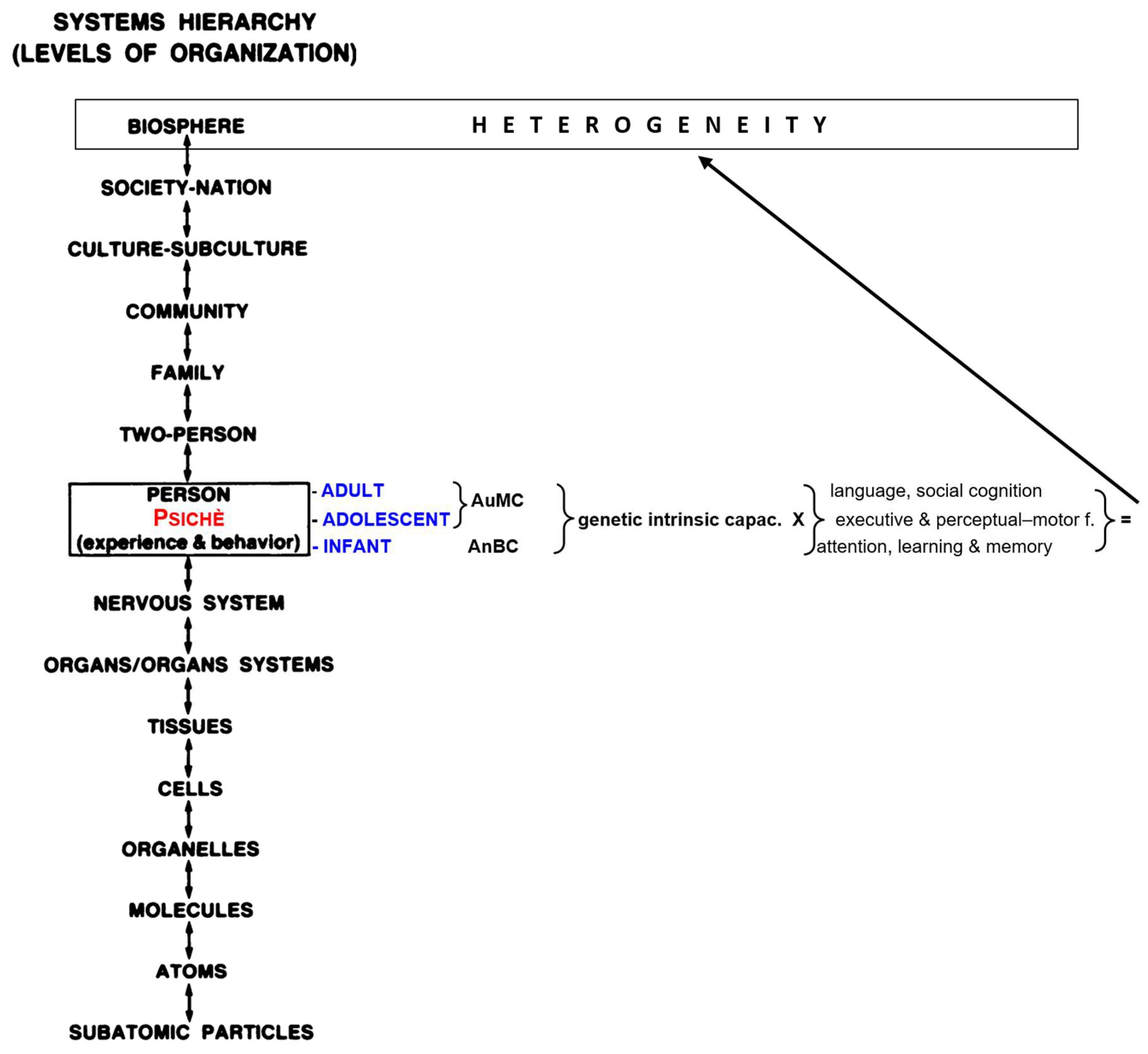

Retrogenesis is the process by which the degenerative and vascular mechanisms of dementias (Reisberg et al., 1998, 2002), now classified as Major Neurocognitive Disorders (NCDs) (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013), reverse the order of acquisition in the normal development (Reisberg et al., 1986; Reisberg, Franssen, et al., 1999; Reisberg, Kenowsky, et al., 1999; Rubial-Álvarez et al., 2013). Precise relationships were scientifically documented between the cognitive, linguistic, praxic, functional, behavioral and feeding changes in the course of the Major Neurocognitive Disorders (MaNCDs) and the inverse corresponding Piaget’s developmental sequences (Thornbury, 1992), especially in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Reisberg B et al., 2016). Similar inverse relationships between AD and human development can be described for physiologic measures of electroencephalographic activity, brain glucose metabolism, and developmental neurologic reflex changes (Franssen et al., 1997; Souren et al., 1997). The development of the persons is gradually from infancy and continuous along the heterogeneous pathways of individual biopsychosocial (BPS) development (biosphere) (Engel, 1980, 1982).

In particular in the hierarchical development of the biosphere from birth (Muller et al., 2014), the nervous system is the apex system that connects and manage as a whole unicum the psychological features and intellective activities that each person accomplishes in every moment of his life (Engel, 1996), also known as “MindBrain” (Pally et al., 2018).

As wrote Hering (Hering, 1870): ‘‘Memory connects innumerable single phenomena into a whole, and just as the body would be scattered like dust in countless atoms if the attraction of matter did not hold it together so consciousness – without the connecting power of memory – would fall apart in as many fragments as it contains moments”. As a consequence, the BPS retrogenesis may be a key to understand the global rewind of a person affected with MaNCD (PwMaNCD)

The BPS retrogenesis of the PwNCDs and its related functional stages (Spector & Orrell, 2010) were reversed into corresponding developmental age equivalents (DAEs) (Reisberg et al., 1986). As a fact, the developmental process of the MaNCDs replicates the ontogenetic sequence in which the neurologic structures (Reisberg et al., 1998), particularly the limbic system (Braak et al., 1996) evolved from infancy. The neuropathologic sequence of brain changes in AD (Braak et al., 2011) develops in the reverse order of the normal development of the cortical regions after birth (Alves et al., 2015; Ewers et al., 2011; Gogtay et al., 2004; Gogtay & Thompson, 2010; P. M. Thompson et al., 2003; Wegiel et al., 2021).

The retrogenesis-DAEs have been the cornerstone pattern to understand the heterogeneity (Cohen-Mansfield, 2000) of cognitive, behavioral and functional changes of the MaNCDs and, as a consequence, to develop the staging tools to map the related needs of general care in PwMaNCDs like Global Deterioration Scale (GDS), Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) and Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR). (Auer & Reisberg, 1997; Dooneief et al., 1996; Morris, 1993; Reisberg, 1988; Reisberg et al., 1982, 2011)

The staging of MaNCDs is the first of ten pivotal measures to improve the needed quality in the holistic management of the PwNCDs (Odenheimer et al., 2014).

Basically, the BPS retrogenesis must be amended by necessary caveats, common to all the PwMaNCDs, regarding the multidimensional assessment (Becker & Cohen, 1984; Rubenstein, 1983; Rubenstein et al., 1984) of physical, comorbid and societal differences and, in background, between PwMaNCDs and their developmental age “peers.” (Reisberg et al., 2002).

More specifically, the BPS retrogenesis takes in account the intrinsic psychic-intellectual capacity [creativity, intelligence quotes (IQ), self-learning/education, motivation toward life, environment, openness to experience] (Bautmans et al., 2022; Cesari et al., 2018) with which every person develops and mix from infancy the six domains of cognition, namely: complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual–motor function, and social cognition with relative sub-domains (Sachdev et al., 2014).

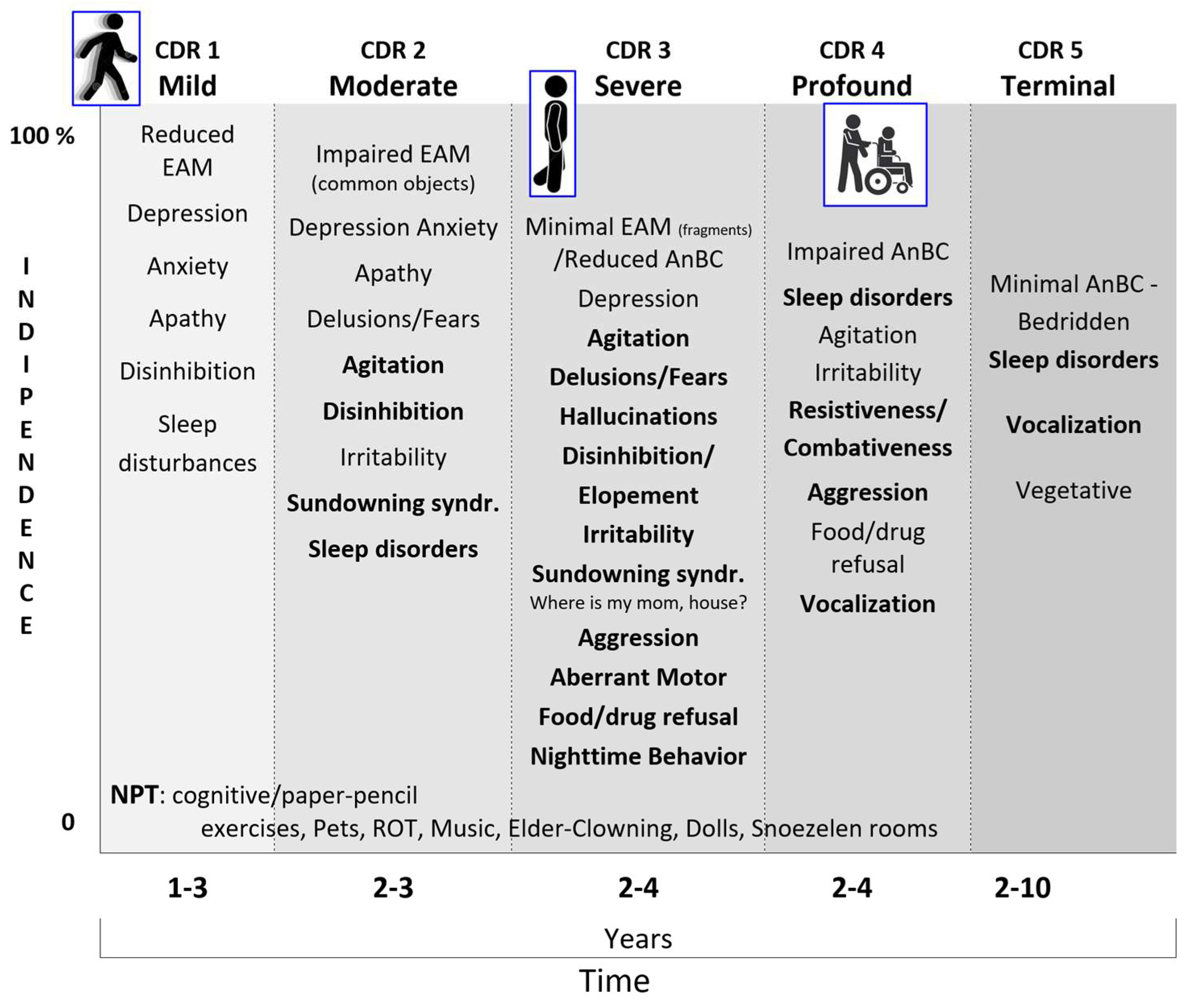

In particular, the domain of socio-emotional cognition explains how socially inappropriate behaviors, usually termed as “behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia” (BPSD) (Cummings, 1997; Watt et al., 2024) recently implemented with “agitation” (Sano et al., 2024), can manifest as a disruptive feature in 60-75 % of the PwMaNCDs (Lyketsos et al., 2002; Selbæk et al., 2014). The socially inappropriate behaviors and related symptoms are caused by the progressive loss of the acquired ability (autonoesis) to inhibit unwanted behaviour, recognize social cues, read facial expressions, express empathy, motivate oneself, alter behaviour in response to feedback, or develop insight (Reisberg et al., 1998; Sachdev et al., 2014).

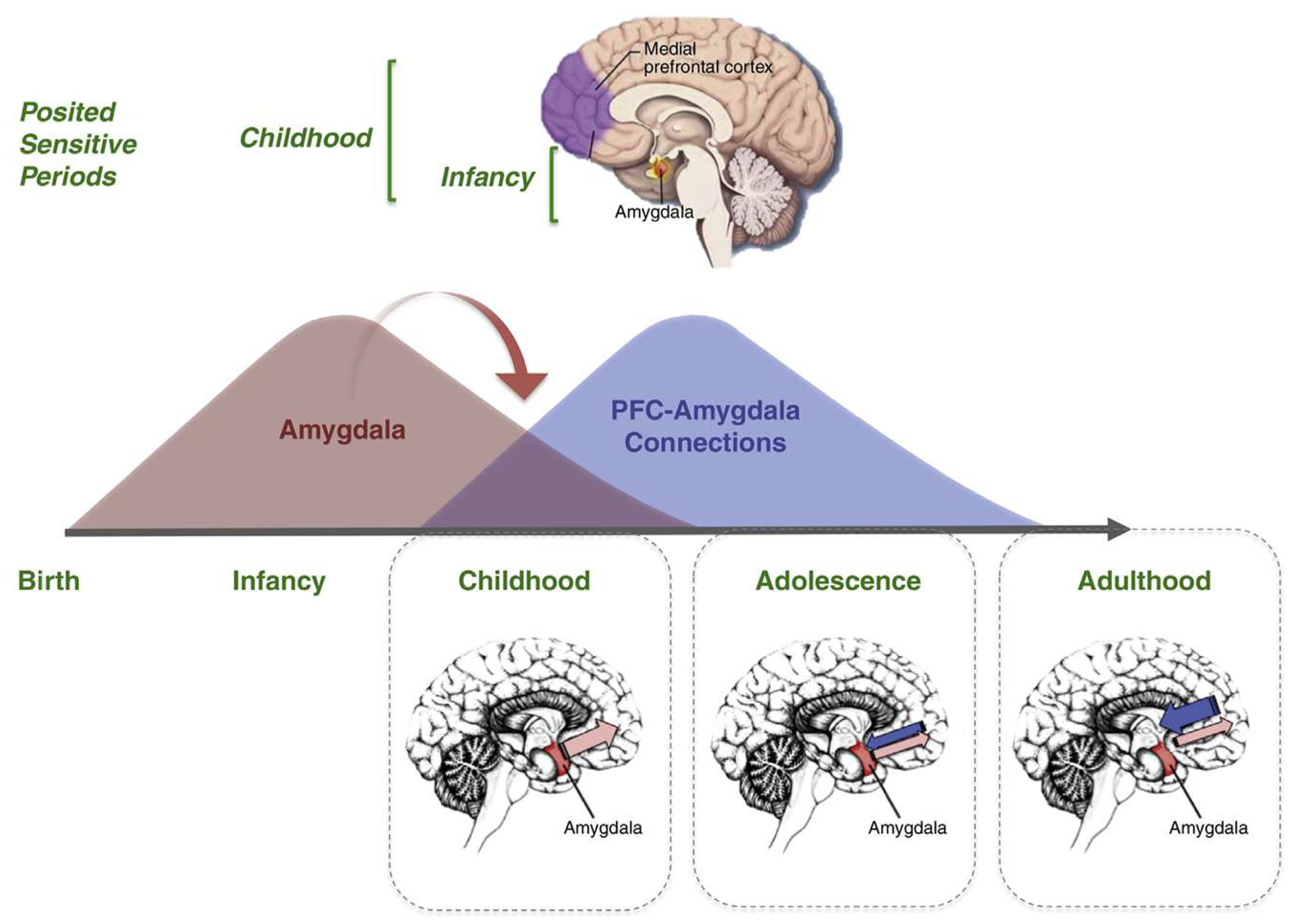

Therefore, in the retrogenesis pathway one relevant issue is the reversal from autonoesis, the autobiographical and behavioral awareness arousing at 3-5 years of age (Tustin & Hayne, 2010) Dafni-Merom & Arzy, 2020; Dickerson & Eichenbaum, 2010, to anoetic consciousness, best known as infantile amnesia (IA) (Alberini & Travaglia, 2017; Travaglia et al., 2016). The transition of socio-emotional cognition from infancy into adolescence and adulthood is characterized with the progressive amelioration of cognitive control and decision-making that are dependent from specific cognitive capacities co-evolving with complex network effects within and between different “resting-state networks” (RSNs), throughout postnatal development (Grayson & Fair, 2017). As a consequence, the progressive loosing of autonoesis in PwMaDNC is due to the related continuous impairment of the RSNs from the level of development that the six domains of cognition reached in the adult brain’s functional organization (Braun et al., 2015; Marek et al., 2015).

The BPS retrogenetic transition from autonoesis to IA adds one more caveats regarding the corresponding DAEs in the “moderately severe/profound” and “severe/terminal” stages of the MaNCDs: they may elapse until 20 years before death and are characterized with the most challenging issues for the caregivers and physicians as regard the care and management of the PwMaNCDs.

As a consequence, the acquaintance of the development of memory/knowledge after birth and in childhood adolescence is a relevant issue for physicians and caregivers to understand the retrogenesis of the PwMaNCDs biosphere to which parallelly adapt caring (Galvin, 2015).

At this purpose, the aims of this work are: 1) to detail briefly the development of memory/knowledge after birth and its physiological transition from IA to autonoesis; 2) to describe the BPS and functional characteristics of the retrogenesis from autonoesis to IA in the PwMaNCDs.

2. Methods

The literature review was performed by consulting the PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus databases, which were consulted from January until November 2024, with unlimited searches as regards years. The inclusion criteria were: literature reviews, meta-analyses, articles in English. A phrase search was performed with the individual terms separated by the AND operator.

The research was conducted using a wide range of retrogenesis related keywords for each domain.

The 43 keywords used were: infantile amnesia, episodic memory, ontogeny of memory, autonoesis, anoesis, consciousness, neurocircuitry of memory, amygdala, nucleus basalis of Meynert, hippocampus, emotion, cognition, biopsychosocial model, major neurocognitive disorders, mild neurocognitive disorders, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Frontotemporal dementia, neuropathological staging system for NFTs/NTs staging of AD, biological clock, circadian rhythm, non-pharmacological treatment, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal-gonadal axis, Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms of Dementia, agitation, advanced Activities of Daily Living, instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Activities of Daily Living, swallowing solids, balance and gait/walk, fear, fear of falling, sleep-wake rhythm, multidimensional comprehensive geriatric assessment, amyloid–tau–neurodegeneration, neurofibrillary tangles, brain cholinergic denervation, cognitive stimulation, Reality Orientation Therapy, elder-clowning, pet therapy, dolls therapy, staging tools for dementia.

The abstracts of each record were evaluated to determine their relevance as regards this research, giving a total of 234 eligible records.

Infantile Amnesia

In the ontogeny of memory, the IA refers to the absence of episodic-autobiographical memory (EAM) (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011) in the first 3-5 years of life and, after then, the first few EAMs begin to consolidate, marking the beginning of metamemory (Occhionero et al., 2023; Souchay et al., 2013) at approximately 4 to 7-8 years of age (Madsen & Kim, 2016). Freud is acknowledged the first scientist who defined IA as the “failure of memory for the first few years of life”, underlining the emotive and psychological impact that these experiences can have throughout the lifespan (Freud, 1914).

The IA is present in all the other mammalian brains with different extent (D. Denton, 2006; Hood & Price, 2011)

Aside to IA, the infant’s memory is characterized from other relevant phenomena like the infantile generalization (IG), the bias towards memory generalization during early development, the enhanced extinction and reversal learning, temporary suppression of fear memories (Madsen & Kim, 2016, Amrein et al., 2011; Bath et al., 2016, Deal et al., 2016).

The research argues if the IA is due to a failure of memory storage or memory retrieval (Ramsaran et al., 2019). Nevertheless, this approach considers the infant’s memory, characterized from absence of EAM, shaped like the adolescence-adulthood one where, instead, the growing functioning of EAM is the basis for the development of the “self” after and not together with IA (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011).

In fact, it is demonstrated that the hippocampus, the basic structure of the memory (Braak et al., 1996; Rolls, 2022) starts to develop and learn after birth (Ellis et al., 2021) (Bessières et al., 2020) but the inputs (D. A. Denton et al., 2009) and outputs (D. Denton et al., 1999) that brain must govern during the IA are totally different from the person’s ones, slowly emerging after IA until adulthood. In infancy the inputs are related to the specific needs “quoad vitam” of the first period of life and the outputs are connected to the progressive discovery, control and conquer of the body coupled to the ongoing hippocampal and brain maturation (Engel, 1996).

The acquisition and govern of the body are the first natural and essential step (Piaget, 1936) for switching from “mother and nest dependency” toward to the gaining of the ultimate and completely different goal that is the development of autobiography and control of “me/self” (Belsky et al., 2020; Edelman & Tononi, 2000), in a word the achievement of independence.

The development of “me/self” is related to the never-ending maturation of socio-behavioral cognition (“quoad valetudinem”) from childhood until longevity (Hume, 1739; Jiang et al., 2020) that drive the individual rapid development of other cognitive domains from childhood (Dykiert et al., 2016; Gow et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2011; Ouvrier et al., 2015; Rubial-Álvarez et al., 2007)

Therefore, the absence of EAM in infancy should not be a wonder and the question is: why the EAM cannot develop in infancy? The suggestion to answer to this question will be attempted inserting the development of the newborn as an ecological whole entity from an evolutionistic BPS and functional perspective (Cuevas & Sheya, 2019). In this light, the original BPS pathway should be implemented in the central “person” step adding the “psichè”, the immaterial-genetic engine of the person that steers the three developmental seasons of the life: infancy, adolescence and adulthood (young, middle and longevous) (

Figure 1). The reasons for this approach are the different psychological inputs and the related outcomes (experiences, functions, behaviors) that the six basic domains of cognition (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual–motor function, and social cognition) process in the different seasons of life (K. Nelson & Fivush, 2004) shaped from the different socio-cultural ethnicities (Fivush & Nelson, 2004) (

Figure 1). In fact, if we consider the life development from the point of view of the absence/presence of EAM, the “person” step of the BPS pathway can be rearranged in two genetic developmental stages to which the “nervous system” concurs in the same way (knowledge) but with different strategies and outcomes: infancy and adulthood. In infancy the knowledge is characterized with the progressive attainment of the anoetic consciousness of the body (anoetic body consciousness: AnBC) at the end of which starts the transition to adulthood, via adolescence transitional period, characterized with the progressive development and growing of the autonoetic consciousness of the own mind (autonoetic mind consciousness: AuMC, “cogito ergo sum” (Des Cartes, 1637). (

Figure 2).

As a consequence, the analysis of BPS pathway of the two genetic developmental stages is re-arranged in their ontogenetic roles, rather than limited to their physiological organ supports, as follows: first the socio-functional goals, second the psychological strategies (developmental psychology) and third the related biological domain (neurobiology and neurocircuitry).

3. The Development of Knowledge in Infancy

3.1. Genetic Socio-Functional Goals: To Conquer the Body

In the humans and the other warm-blooded species (mammals and birds) the infancy is the pivotal basic step needed to become adult. The genetic inherited aim of every newborn is to achieve and conquer the complete control of his own body in its ecological niche (Darwin, 1871, 1872) . The socio-functional aims of the human infant knowledge are the attainment of the basic functions pertaining the independence of the body (Activities of Daily Living – ADL) (Katz et al., 1963) (

Table 1). These functions are progressively gained along with the development of the body integrated with the organs and systems (brain, sense organs, muscles, bones, primal teeth, …(Cappellini et al., 2020).

3.2. Psychological Infantile Strategies: Background, Inputs/Outputs

Environmental social influences, especially prenatal and early postnatal life experiences with the mother, father, and other caregivers, prepare the developing neural and neuroendocrine systems (Sheng et al., 2021), which have been organized in the embryo and fetus (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010), for adaptive reaction to the demands and stresses of a young person’s life (Piolino et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2020). Brain organization is revised and updated through processes of meeting complexities of different systems or moment to moment meetings between the caregiver and the infant (Panksepp et al., 2019).

The children could not permanently judge what originates from personal experience before the age of 3 because in this stage the brain development is the product of a complex series of dynamic and adaptive processes operating within a highly constrained, genetically organized but constantly changing context leading to the advent of metamemory-metacognition (Godfrey et al., 2023; Souchay et al., 2013).

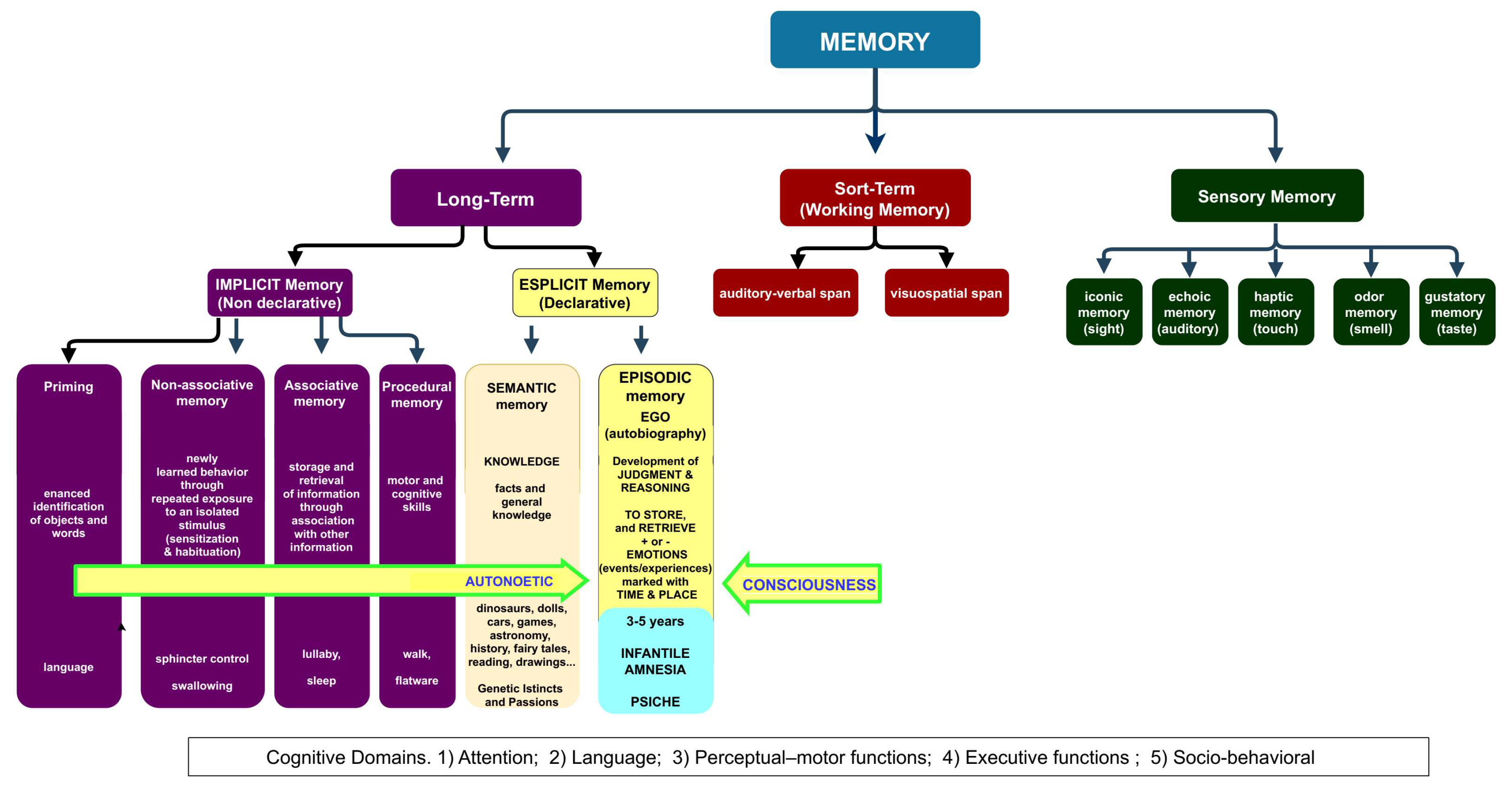

It can be argued that the development of language and semantic memory during the AnBC are interactive strategic tools that permit the birth of the new and different knowledges linked to time-space and, mainly, to a changing emotional individual contest leading to the rising of the permanent memories of AuMC/EAM.

The development of language permits to the infant to substitute the monomodal vocal alarm signals, like crying with which to catch the mother’s attention, with the multiform verbal interaction for discovering, understanding and fixing the surrounding world.

So, the AnBC stage is polarized to acquire and stock the long-term memories relative to the body control (

Table 1) that merge to the subsequent stage of AuMC.

The absence of permanent judgment in AnBC is strategical in the infant’s experiences for the acquisition of three functions of the body: hygiene, swallowing solids, balance and gait/walk. In fact, these experiences may be very unpleasant like the shocking abandon of the warm breastfeeding forcing the mouth with unpalatable things to be swallowed in a new way or the fearful acquisition of balance and the many painful falls that lead to the gait/walk control.

It is evident that the infant AnBC consider these frequent, unpleasant and painful episodes (Chaudhary et al., 2018) as temporary inconveniences that are rapidly forgotten because not stored as “threats/dangers” like it would happen in a frontal controlled adult. If the infant could have a developed AuMC these troubles would be classified as threats/dangers for life and he would never have learned to swallow solids or to gain balance and gait/walk.

The fear of falling (FOF), in the longevous frail but not demented adults, represents reverse evidence of this behavior. FOF is an important public health problem, causing excess disability among older people (Lach & Parsons, 2013) . FOF begins with poor confidence in mobility because of a fall or other physical problem affecting gait and balance. The advent of FOF is due to the good functioning of the longevous adult’s AuMC/EAM from which is retrieved the concept of threats/dangers consequent to a fall (always pain, sometimes fractures) that lead to a self-imposed restriction of activity and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle (Gambaro et al., 2022) .

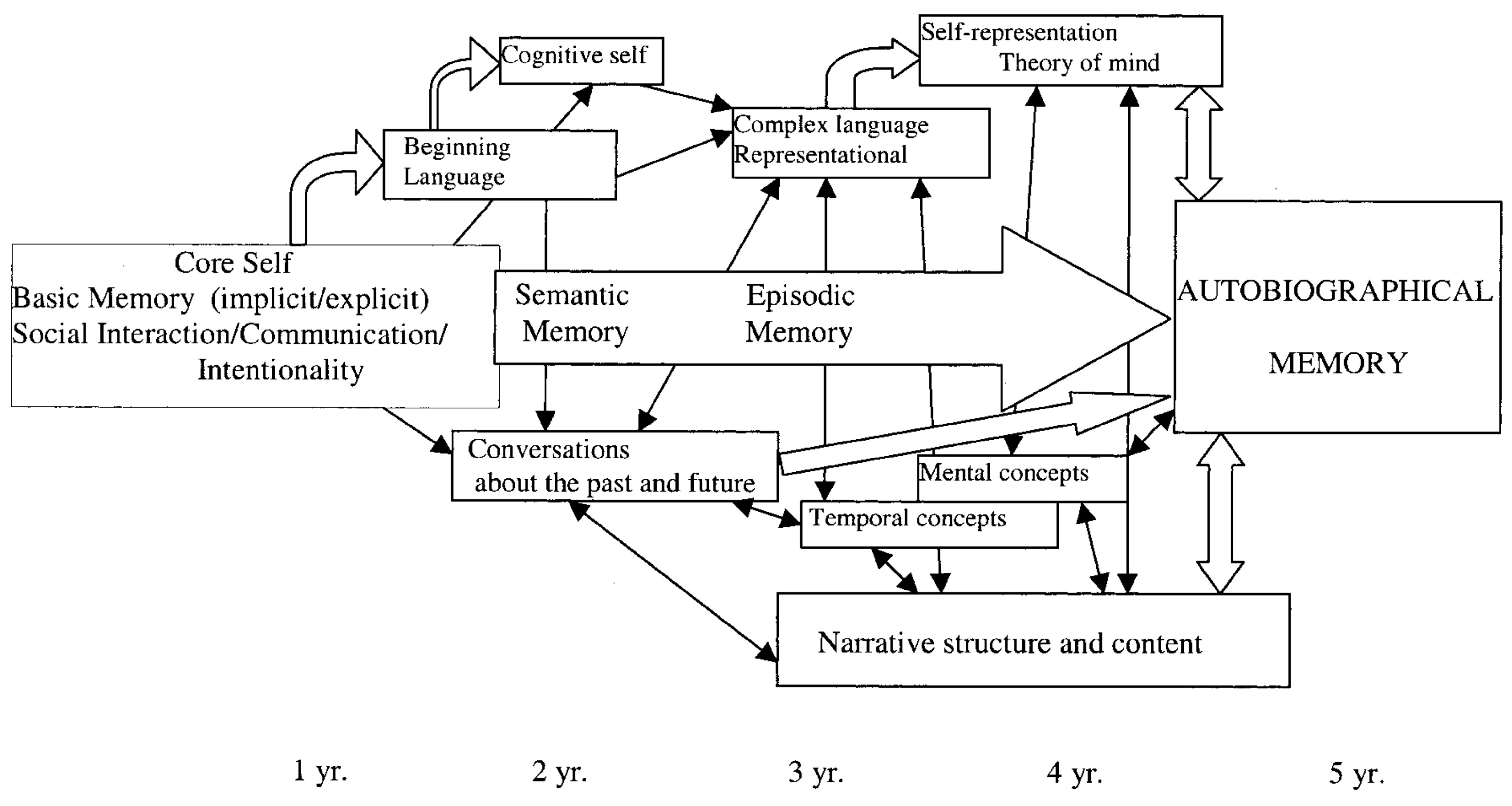

The development of EAM is greatly influenced by the maternal relationship: the way in which the mothers assemble their conversations when reminiscing with their children has a relevant impact on the inception of EAM and the way with which the children describe their past. The maternal reminiscing style is, however, moderately mediated by the nature of the mother–child affection that, when insecure, may negatively impact on the quality of the kids’ EAM (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011).

The research considers four hierarchal models of self-development (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011): firstly, a very basic ‘‘proto-self’’ grounded in the sensory and motor domains, secondly a pre-linguistic, affective ‘‘core self”, followed by a semantic “cognitive self” and then by an ‘‘autobiographical-narrative self” (EAM).

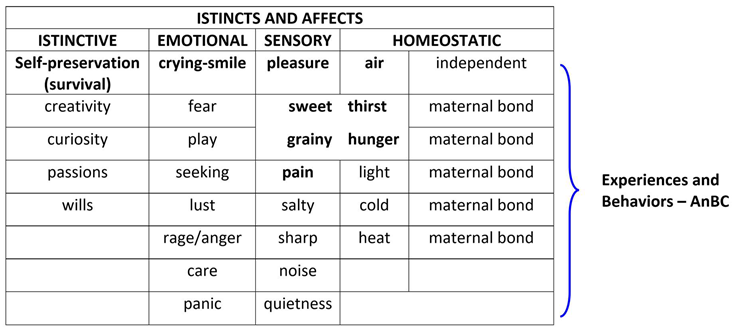

In infancy, this process is mediated from a primal system that comprehends four categories of inborn affects: “instinctive, emotional, homeostatic and sensory” (

Table 2) (Hutson, 2018; Panksepp et al., 2019)

.

In the light of the retrogenesis and DAE, the affects, particularly the emotional and sensory ones (

Table 3), appear variously related to the resurface of the toddler/child’s temperament and behaviors in the PwMaNCDs but with the difference that in toddler/child the affects are finalized to their homeostasis, (Gartstein & Rothbart, 2003; Liu et al., 2013) while become non-finalistic in PwMaNCDs (O’Leary et al., 2005). In fact, the progression of DNC to advanced stages like “moderately severe” and “severe” in GDS/FAST or “profound” and “terminal” in CDR (Dooneief et al., 1996) , brings the patients to lose the prefrontal driven personal and social meanings of the acquired ADL (see: infant genetic socio-functional aims) and consequently the PwMaNCDs’ behaviors may become problematic, oppositive and dangerous for the caregivers (Reisberg et al., 1998) due the weight and strength of their adult body. Moreover, the PwMaNCDs recover the infant sensory instinct like the sweet taste or emotional like uncontrolled fear (Tao et al., 2021) or playing (Low et al., 2013) .

The resurface of non-finalistic behaviors in PwMaNCDs are defined as “Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms of Dementia” (BPSD) (Cummings, 1997; Gottesman & Stern, 2019; Ray et al., 1992) and “Agitation” (Sano et al., 2024).

3.3. Neurobiology and Neurocircuitry

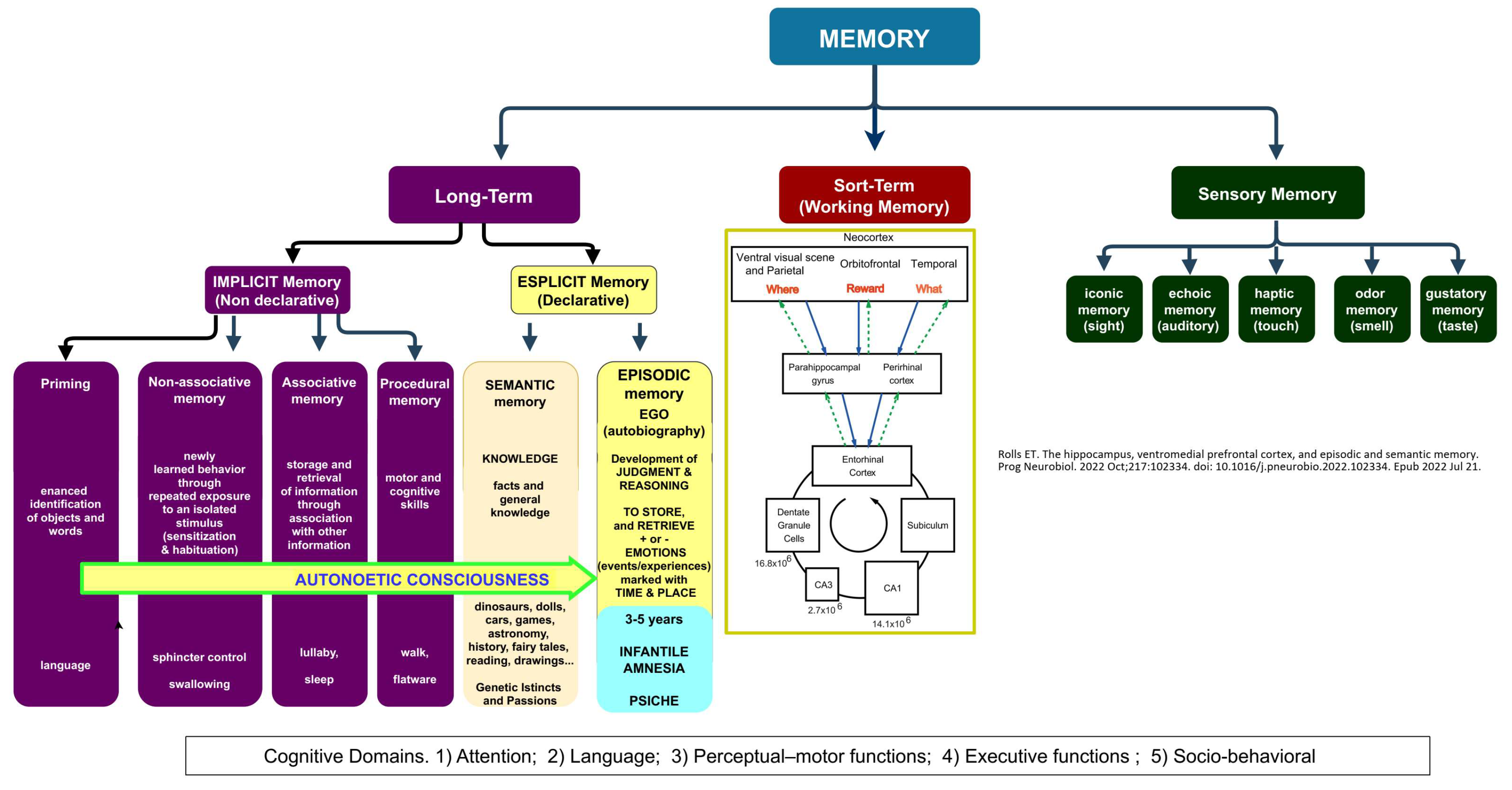

The human developmental studies emphasize that children first acquire the semantic memory system and only thereafter their EAM neurocognitive capacities emerge (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011b).

In fact, the development of the semantic memory in concert with the language (Gómez et al., 2014) and conceptual knowledge are essential to acquire the adult knowledge, the ability to “understand and explain” (

Figure 3).

This ability progressively substitutes the indistinct on-off “crying-smile” parental-bond and primal system of communication (Table n. 2) with higher levels of self and self-understanding, of understanding the feelings and intentions of others, of executive functions and working memory (Figure n. 2 and 3), acquiring the capacity for the mental time traveling and the maturation of the nervous system (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011a; Staniloiu & Markowitsch, 2019).

As regards the development of language, the on-off “crying-smile” primal system, vital for survival, may be resembled to the afterbirth breastfeeding stage before the acquisition of swallowing solids as regards the development of swallowing.

These core-affects are elaborated in ancient subcortical networks that exist in all mammalian brains (Robinson & Barron, 2017), integrated with hippocampal learning (Braak et al., 1996; Ellis et al., 2021). It is well-known that the progressive AnBC is characterized from the acquisition of many bodily long-term memories (swallowing, walking, sphincteric control, etc.) whose development occur under the voluntary systems already active after birth. In fact, we can reject a waste food and contrast an imbalance while walking both when infants or adults. So, it can be argued that both AnBC and AuBC, even if targeted to the different aims/skills of infancy and adulthood, develop long-term memories as a continuum (Vandekerckhove & Panksepp, 2011).

The research has cleared that the differences in long-term memory of AnBC versus AuBC is explained from the specific patterns of differential anterior and posterior functional connectivity of hippocampus with an increase in the functional specialization along the long axis of the hippocampus and a dynamic shift in hippocampal connectivity patterns that supports memory development (Tang et al., 2020)

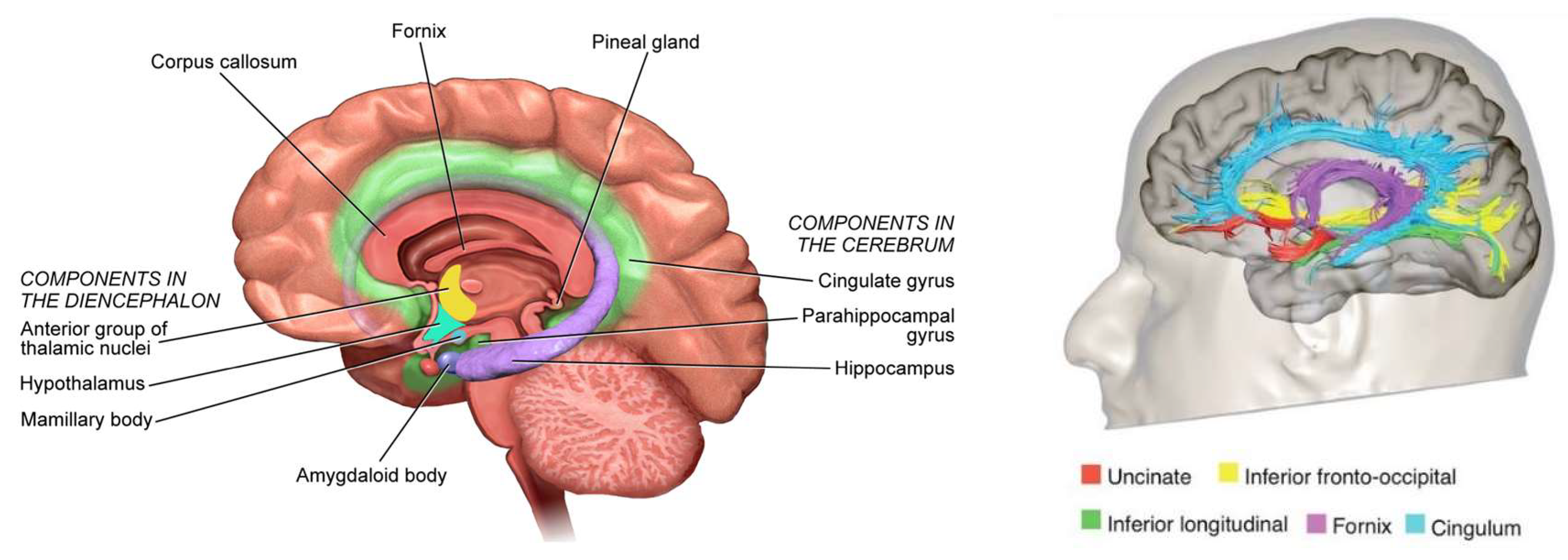

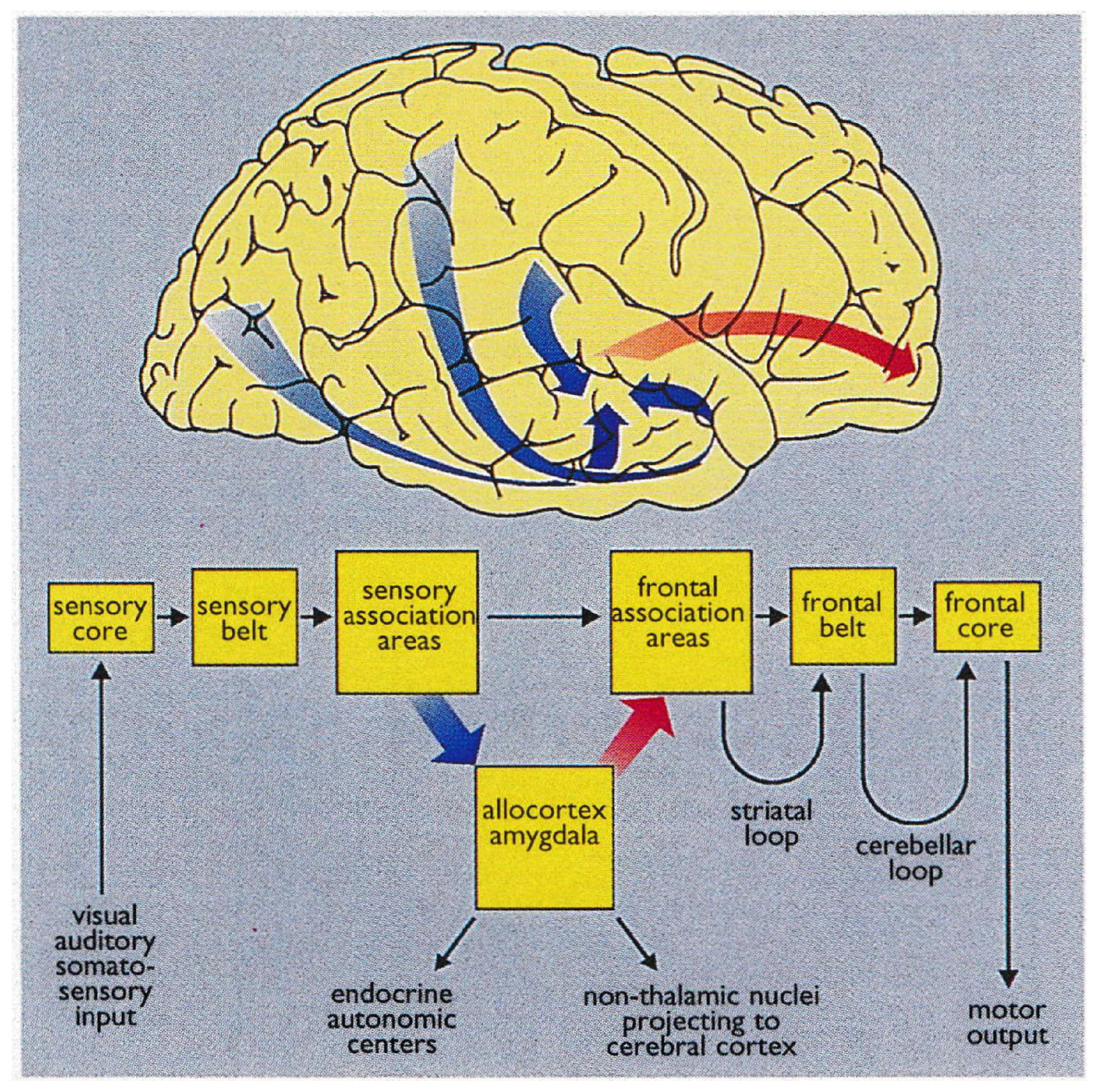

Braak detailed the functional anatomy of memory from infancy that is constituted from limbic system (

Figure 4) (Braak et al., 1996). The somatosensory, visual, and auditory input proceeds through neocortical core and belt fields to a variety of association areas, and from here the data are transported via long corticocortical pathways to the extended prefrontal association cortex.

Tracts generated from this highest organizational level of the brain guide the data via the premotor cortex (frontal belt) to the primary motor area (frontal core). The striatal and cerebellar loops provide the major routes for this data transfer (

Figure 5). The main components of the limbic system (the hippocampal formation, the entorhinal region, and the amygdala) maintain a strategic position between the sensory and the motor association areas. Part of the stream of data from the sensory association areas to the prefrontal cortex branches off and eventually converges on the entorhinal region and the amygdala (Hortensius et al., 2017; LeDoux, 2007; Tottenham & Gabard-Durnam, 2017) (

Figure 6).

These connections establish the afferent leg of the limbic loop. In addition, the limbic centers receive substantial input from nuclei processing viscerosensory information. The entorhinal region, the hippocampal formation, and the amygdala are densely interconnected. Important among these connections is the perforant path, which originates in the entorhinal cortex and projects to the hippocampal formation (fascia dentata, Ammon’s horn, and subiculum) (

Figure 5).

The subiculum projects to the amygdala, entorhinal region, mamillary nuclei, and anterior and midline thalamic nuclei. The hippocampal formation, the entorhinal region, and the amygdala generate the efferent leg of the limbic loop, which is directed toward the prefrontal cortex (

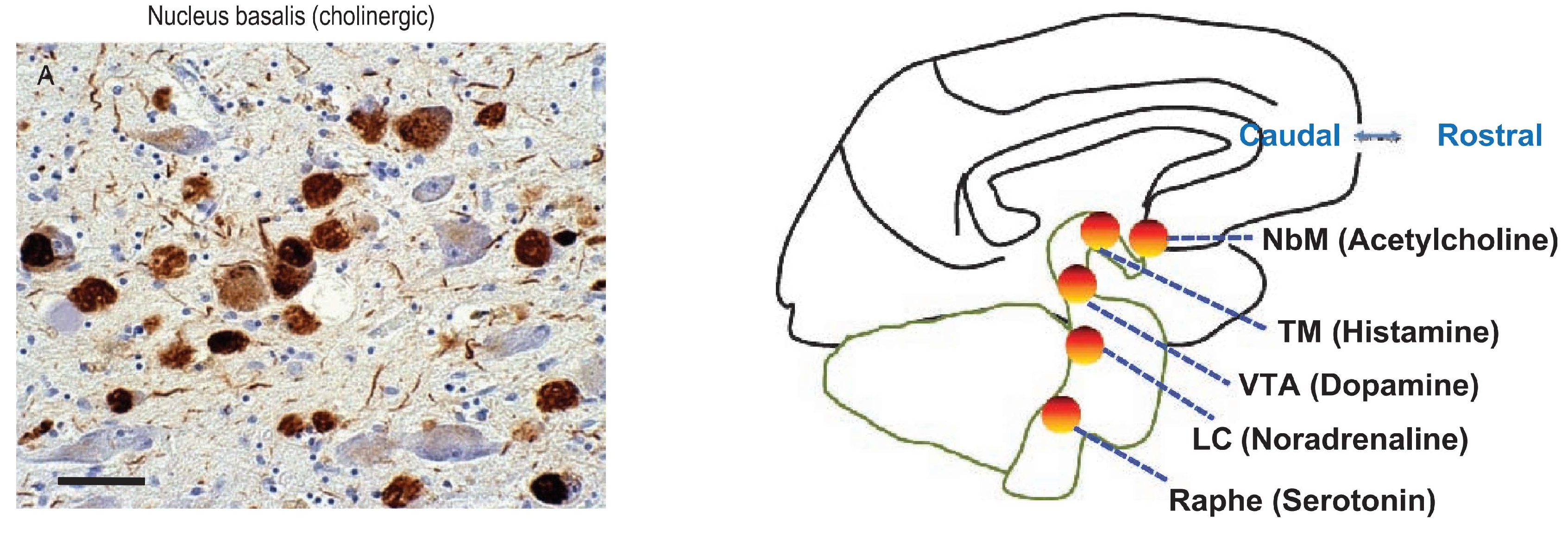

Figure 5) (Janak & Tye, 2015). Additional projections reach the key nuclei that control endocrine and autonomic functions: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-gonadal (HTPAG) axis. The HTPAG axis is a complex system of neuroendocrine pathways and feedback loops that function to maintain physiological homeostasis (Sheng et al., 2021). Furthermore, the amygdala exerts influence on all nonthalamic nuclei projecting in a nonspecific manner to the cerebral cortex (ie, the cholinergic magnocellular forebrain nuclei, the histaminergic tuberomamillary nucleus, the dopaminergic nuclei of the ventral tegmentum, the serotonergic anterior raphe nuclei, and the noradrenergic locus coeruleus) (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011a).

The limbic loop centers perform integration of exteroceptive sensory data of various sources with interoceptive stimuli from autonomic centers. Their efferent projections exert influence on both the prefrontal association cortex and the key centers controlling endocrine and autonomic functions (Braak et al., 1996).

The advent of time awareness, time orienting and proper handling of time epochs and temporal order (mental travel) are related especially to the after-birth development of prefrontal and parietal cortex. The absence of time encoding in the first years of infancy is the essential physiological and neurobehavioral reason that explains the related absence of EAM (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011b) and circadian rhythms (Carter et al., 2021).

Another essential reason that explains the absence of EAM in infancy is related to the absence of a developed gender-oriented sexuality. It is known that the HPTAG axis secrets gonadal hormones in the post-natal period but the concentrations are low and address only the development of the future sexual behavior (Alexander, 2014; Cacciatore et al., 2019; Kuiri-Hänninen et al., 2013; Lamminmäki et al., 2012) .

Therefore, the absence of EAM and sexuality permits to the infants, independently from gender, to look at the breast as a warmful and pleasant tool for eating and not as a sexually attractive zone as in adolescence/adulthood.

The long-term memories acquired during the development of the AnBC remain stocked in a deep fundamental nucleus, in a word like a building basement, over which as a continuum, after the 3-5 years of age, the intertwined blocks of the AuMC are progressively placed to build the “pyramid” of the long-life knowledge

4. The Development of Knowledge in Childhood-Adolescence-Adulthood

4.1. Genetic Socio-Functional Goals: To Conquer the Mind/World

The progressive development of knowledge in infants after 3-4 years of age pointed to autonomy shapes the transition from anoetic consciousness or IA/AnBC into the advent of autonoetic awareness or EAM/AuMC (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011b; Scarf et al., 2013).

The turning point is usually at the age of 3 years when the infant begins to walk upstairs with alternating feet, to join in

make-believe play with other children and to ask to adults

“what?”, “where?”, “who?”, “when?” and “why?” (Sheridan et al., 2022) merging the answers with

“reward” and storing them as

“mental time-travel” thus developing the EAN/AuMC (

Figure 7) (Rolls, 2022).

After the infant AnBC, the autonoetic childhood-adolescence is committed to acquire two parallel genetic targets that are independence and sexuality, both pivotal to reproduction, the foundational life’s goal.

As regards independence it develops during childhood and adolescence acquiring the knowledge of the intermediate socio-functional states of autonomy, largely overlapping with the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) of the longeval adults (

https://www.alz.org/careplanning/downloads/lawton-iadl.pdf) (Lawton & Brody, 1969).

As regards sexuality, the developmental tasks of childhood-adolescence comprise accepting one’s body, adopting a gendered social role, achieving emotional independence from parents, developing close relationships with peers of the same and opposite genders, preparing for an occupation, preparing for marriage and family life, establishing a personal value or ethical system, and adopting socially responsible behavior (

Figure 1). Thus, adolescent development largely focuses on issues related to sexuality (Cacciatore et al., 2019) .

In turn, the adolescent autonomy is the necessary stage to achieve the (legal) adult independence: the right to vote, the ability to work (complex activities: Advanced Activities of Daily Living (Carta et al., 2023; Sikkes et al., 2013)), the responsibility to get married and generate sons (De Vriendt et al., 2013; LaFreniere, 2024; Mlinac & Feng, 2016).

4.2. Psychological Strategies: Background, Inputs/Outputs

The infant state of AnBC progresses in brains states from which capacities for higher forms of consciousness gradually emerge with brain-mind encephalization leading to EAM/AuMC (Vandekerckhove et al., 2014). The EAM is “..a past- and future-oriented, context embedded neurocognitive memory system that receives and stores information about temporally dated episodes or events, and temporal-spatial relations among them from one’s past” (Tulving, 1984, 2024).

The consolidation and recall of these EAMs from one’s past are regulated by states of anoetic affective consciousness. Consequently, implicit self-relevance becomes intimately related to each individual’s biosphere that are the unique feelings, thoughts, goals, and behaviors.

The EAM differs from other forms of memory (

Figure 7) because requires an extended sense of self that engage in mental time-travel: it marks past events generating future scenarios and options (Dafni-Merom & Arzy, 2020) .

The self, AuMC and EAM are inputs strictly interlocked, both ontogenetically and phylogenetically, and overlap each other enhancing their mutual development. Their appearance and development take place in concert with other cognitive and emotive functions – the ability of perspective taking, executive functions, language, the feeling of empathy, the ability to reflect on oneself, solving abilities with divert thinking, etc. (Sutin & Robins, 2008) .

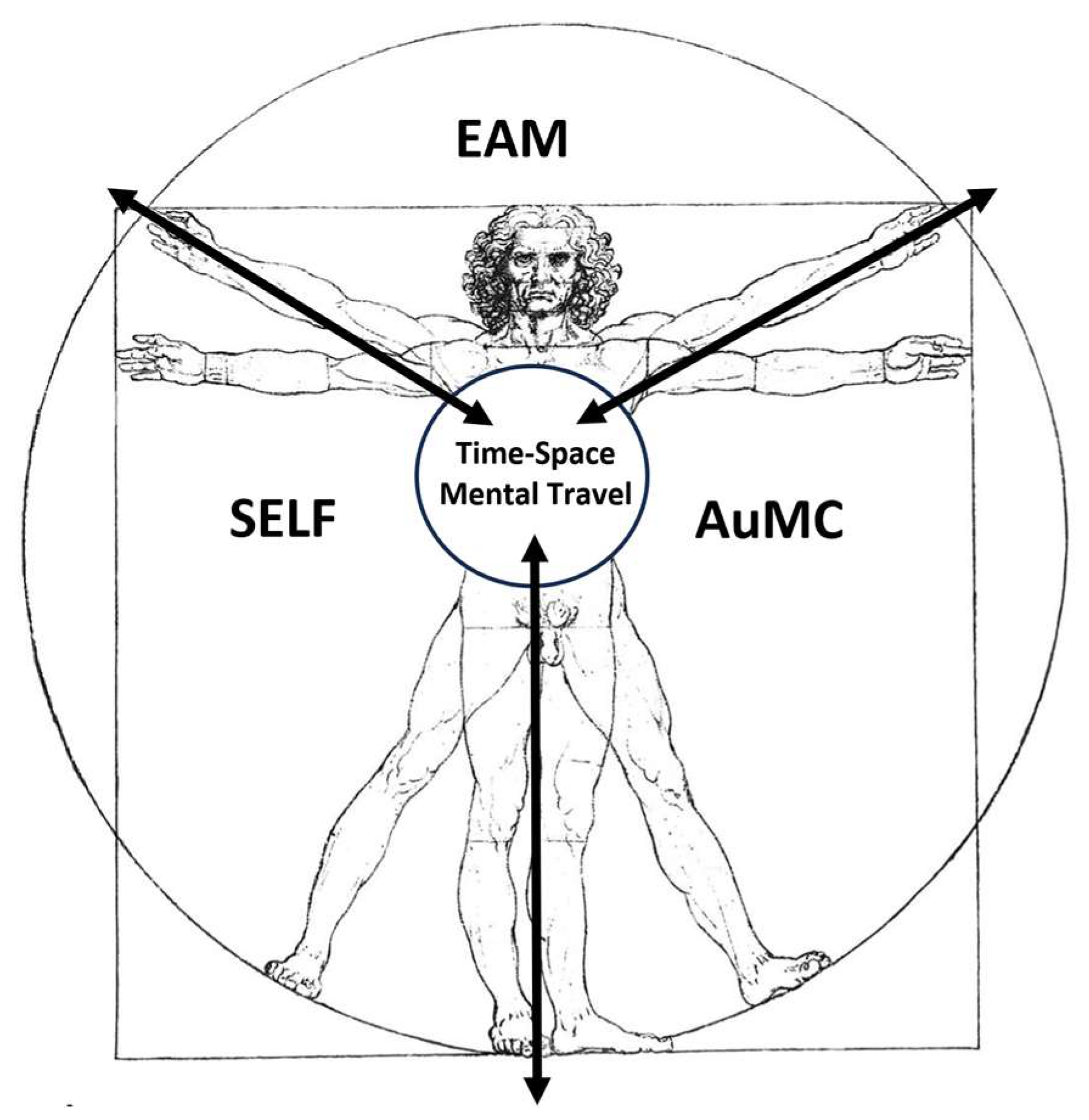

The relationship among self, AuMC and EAM can be represented in a Vitruvian man silhouette where the

‘‘multiplicity/multimodality of the self of the EAMs” (semantic representations of one’s personality traits, semantic knowledge of facts about one’s life, experience of continuity through time, sense of personal agency and ownership, ability to self-reflect and the physical self) (Klein & Gangi, 2010) represent inputs that lead to the

individual ecological, interpersonal, conceptual, remembered, and private self outputs (

Figure 8) (Neisser, 1988).

4.3. Neurobiology and Neurocircuitry

AnBC is a state of pre-reflective affective and sensorial perceptual consciousness essential for the waking state of the organism in the absence of an explicit self-referential awareness of associated cognitive contents. This state of affective and sensorial consciousness acts as a bridge that connects deeply unconscious information processing, primordial affective feelings and perceptual consciousness toward the possibility of knowing (noetic) levels of consciousness situated within the basal ganglia (amygdala (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011a), nucleus accumbens, bed nuclei of the stria terminalis) that mediate learning and memory and higher regions of the brain, such as the neocortex which allows for mental time-travel from the permutations of these memories (EAM/AuMC) (Vandekerckhove et al., 2014).

Later in development, when reflection is possible, those primal affects act as free-flowing streams underlying the more cognitively detailed aspects of our continuously ongoing cognitive-noetic and autonoetic information processing as thoughts, images, fantasies, expectations, and anticipations. In contrast to anoetic consciousness, autonoetic consciousness refers to the reflective capacity to mentally represent a continuing existence that is embedded in specific episodic contexts and associated with remembered experiences with affective quality – from “warmth and intimacy” to “dread and alienation.” (Vandekerckhove et al., 2014)

The functions of self, AuMC and EAM (

Figure 8) are mediated from portions of the prefrontal cortex, in particular its ventromedial and lateral right-hemispheric regions. The anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus, and the temporo-parietal junction area are engaged in addition to medial prefrontal regions (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011b).

Time awareness, time orienting and a proper handling of time epochs and temporal order are related especially to the prefrontal cortex, while the proper perception of time and time epochs seems to engage the parietal cortex as well as the diencephalic structures as mentioned before (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011b).

The ability to re-experience the past events and pre-experience personal future events might also be severely impaired after bilateral medial temporal lobe damage (Piolino et al., 2009).

The personal ownership of mentalizing, probably most developed in humans, is deeply mediated by hippocamps and frontal lobes evolution and microstructure. The neural correlates of EAM/AuMC are linked to various memory abilities, especially declarative memory, and AnBC is strongly connected to raw sensorial and perceptual abilities, to various subcortical affective processes, and intrinsic affective value structures. These processes take place into the limbic and paralimbic structures associated intrinsically with the more implicit free-flow of affective consciousness (Vandekerckhove et al., 2014) .

The emergence of EAM/AuMC in childhood is coupled with the progressive stabilization of the biological clock, adapted to light-dark cycle, that regulates the circadian rhythms for sleep-wake, hormone production, and importantly, memory (Rivkees, 2004) .

The neural system of the biological clock is the paired suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) in the anterior hypothalamus, located above the optic chiasm at the base of the third ventricle. The SNC has input and output pathways, i.e., with the HPTAG axis and exhibits endogenous rhythmicity with a period of oscillation close to 24 hours (Rivkees, 2003)

The SCN controls output timing to peripheral oscillators, i.e., the liver, heart and discrete regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, to coordinate the daily cycling of numerous essential physiological processes (Carter et al., 2021).

The stabilization of the biological clock, including the times for eating and the sphincteric control, allow the development of progressive organized daily activities (Carter et al., 2021).

One foundational element that influence EAM/AuMC as regards the progress of social cognition and related behaviors is the development of sexuality due to maturing of the HTPAG axis (Child Sexual Abuse Committee, 2009; Vignozzi et al., 2015)

Sexuality and developmental control behavior are based on a critic equilibrium among personal expectations and desires and partner’s fulfillment whose disappointment may cause sexual desire discrepancy and frustration. Sexual frustration describes a state of irritation, agitation, or stress resulting from sexual inactivity or dissatisfaction. Sexual frustration is a common, natural feeling, and it can affect anyone. Sexual frustration is a natural response that many people experience at one time or another but not rarely may cause a state of irritation, agitation, or stress or degenerate in aggressiveness and violence (Anderson & Cindy Struckman, 1998; Evans & Lankford, 2024; Fisher et al., 2012; Lankford, 2021; Lussier & Cale, 2016; Ryan, 2004)

4.3. The Biopsychosocial and Functional Characteristics of the Retrogenesis

The development of a person from birth and his encapsulated Central Nervous System (CNS) is a pathway to assess the PwMaDNC in his comprehensive BPS and functional retrogenetic cascade (

Figure 9). This approach points to examine the PwMaNCD with the methodology of multidimensional comprehensive geriatric assessment (Pirani A. et al., 1990; Rubenstein, 1983) to unify the assessment of the BPS and functional domains of the person as a whole and a continuum and not simply the illness and its manifestation. (Spector & Orrell, 2010)

The long-term memories of the infant-child AnBC, apparently closed forever in the “basement” under the “building” of the AuMC, progressively resurface during the development of MaNCD, from severe until terminal stages (

Figure 9). As the retrogenesis of AuMC, the resurfacing of AnBC occurs with the same modalities disclosing initially with the loss of the last functions acquired in AnBC, like the sphincteric control in severe stage, and proceeding until the frequent loss of swallowing in the after birth – vegetative terminal stage (

Figure 9).

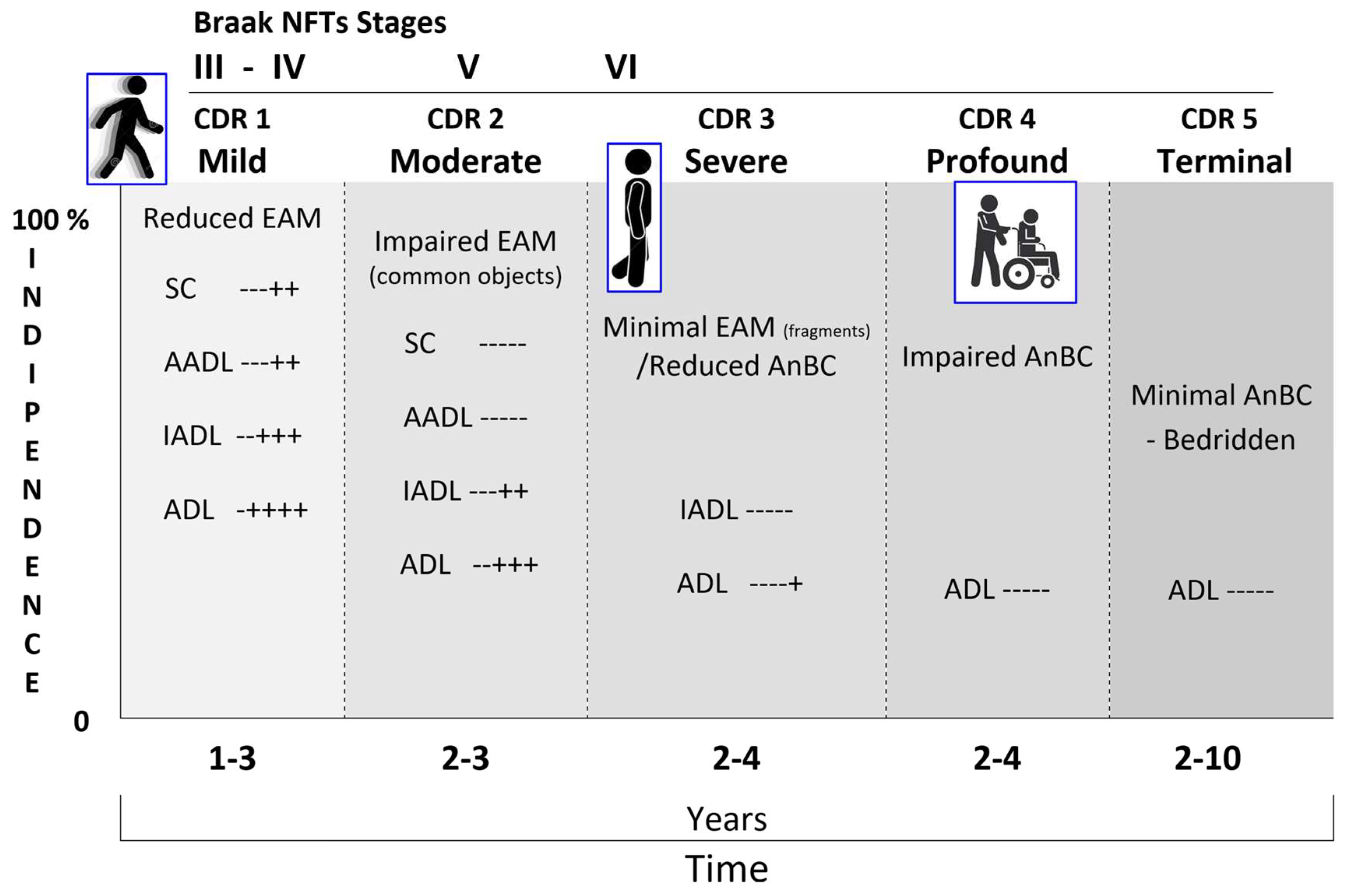

The Braaks’ s work was pioneering not only in detailing the anatomy and functioning of the limbic system related to emergence of EAM/AuMC but, parallelly, in creating the AD neuropathological staging system for NFTs/NTs, a six-stages tool based on the progressive accumulation of NFTs in the limbic system (

Figure 10) (Braak et al., 2011; Braak & Braak, 1991, 1996b; Braak & Del Tredici, 2011; Braak & Del Tredici-Braak, 2015; Jicha et al., 2006)

The neuropathological staging protocol for NFTs/NTs proposed by Braak (Braak et al., 2006) is a pivotal marker of BPS retrogenesis (Braak & Braak, 1996a; Braak & Del Tredici-Braak, 2015) whose appropriateness was recently confirmed with the cognitive (Folstein et al., 1975; Nasreddine et al., 2005), staging (Morris, 1993) and new neuroimaging biomarkers now available (

Figure 11) (Therriault et al., 2022).

In details, the neuropathological staging system for NFTs/NTs proposed by Braak in the development of Alzheimer disease is strictly correlated with the worsening of CDR (

Figure 12) (Gold et al., 2000; Grober et al., 2021; Qian et al., 2017)

4.4. The Biological Domain

The MaNCDs affect the limbic system and the other connected regions with different etiopathogenesis (amyloid–tau–neurodegeneration, cerebrovascular disease, Lewy bodies…) and modalities responsible of the different clinical forms like Alzheimer’s, Frontotemporal, Vascular diseases, Lewy bodies and mixed (O’Brien et al., 2017).

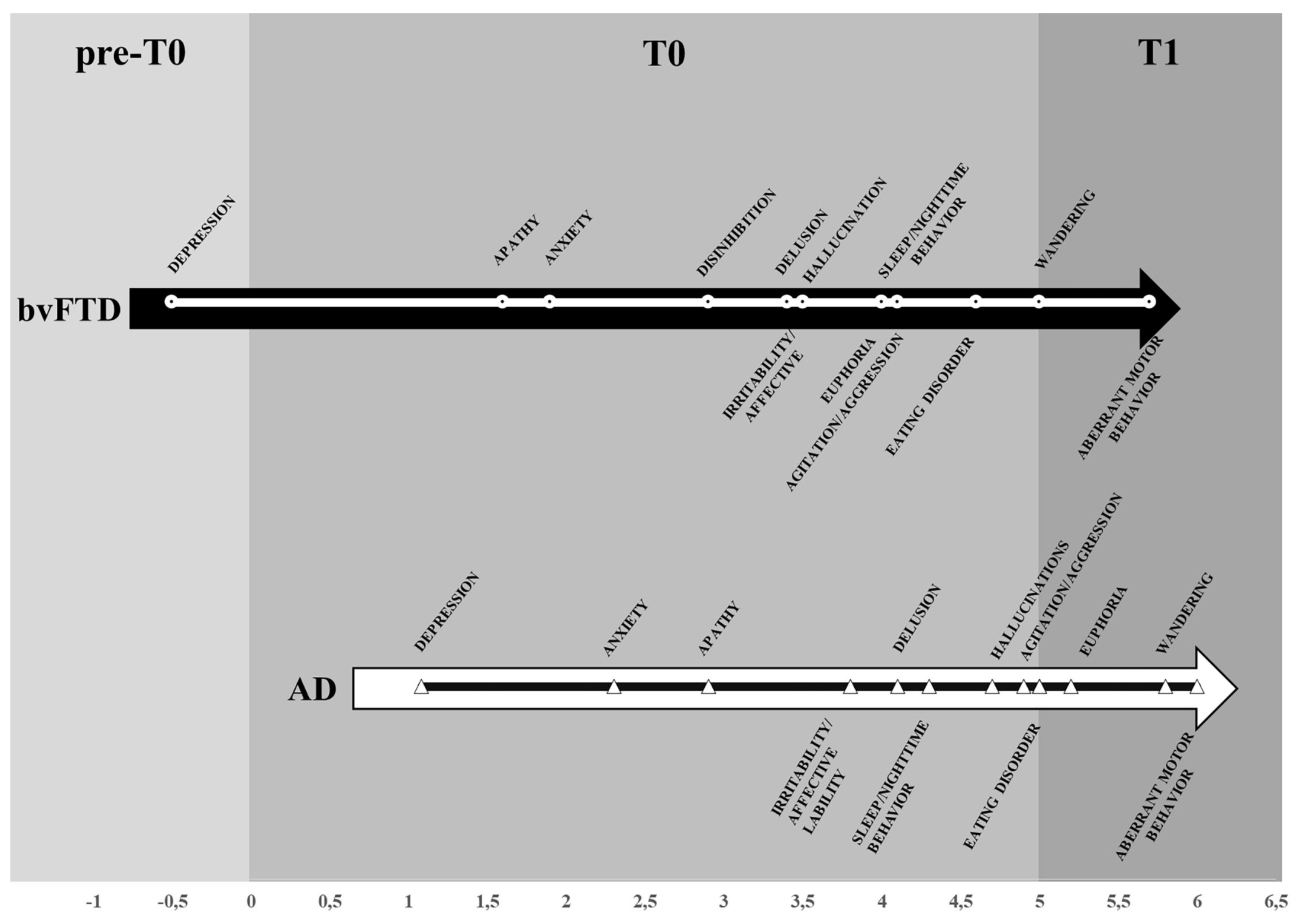

The retrogenetic cognitive, behavioral and functional cascade is common to all the MaNCDs but its clinical manifestations, mainly in the mild and moderate stages of CDR, my change due to different etiopathogenetic involvement the limbic system (Reisberg B et al., 2016). Damage to the parietal cortex as well as the diencephalic structures may disturb the sense of time considerably (including the ability to successively link events in time) (Schönheit et al., 2004) (

Table 4).

As a consequence, the PwMaNCD become unable to encode or store new EAMs successfully because the capacity for episodic future thinking (self-projection in the future) is an essential feature of EAM/AuMC. Severe impairment of EAM has been found in patients with damages at the amygdaloid complexes and related circuitry with forebrain regions (Shafiee et al., 2024).

A special anatomical consideration referent to neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in AD is the impact of NFTs on the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) (P. T. Nelson et al., 2009). ARAS neurons send strong inputs to the cerebral cortex that augment memory, arousal, attention, and motivation. These cells also are severely affected in AD. For example, considering the brain cholinergic denervation (Aghourian et al., 2017), the impact from NFTs on the ARAS cholinergic nucleus basalis of Meynert (NbM) may be profound. NFTs are numerous in the NbM starting early in the disease (

Figure 13), and NFTs density parallels cognitive decline severity as does cerebral cortical cholinergic tone. The ARAS neurons supply neurotransmitters that are absent in the intrinsic cortical neurons: the NbM is a major source of cholinergic neurotransmission in the cerebral cortex, which itself has no cholinergic cells. NFTs are also thought to affect adversely other ARAS neurotransmitters including histamine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin (corresponding to neurodegeneration and NFT-containing cells of the tuberomammillary nucleus, locus caeruleus, ventral tegmental area, and pontine raphe, respectively) (P. T. Nelson et al., 2009)

In the limbic system, the amygdala has a foundational role because it affectively charges cues, especially in aggressive, fearful, and sexual domains, so that explicit or implicit memory events of a specific anoetic significance can be successfully searched within the appropriate neural nets and thereby re-activated (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2011a; Pessoa, 2010; Šimić et al., 2021). Emotionally stressful life events impact the amygdala and the hippocampus – areas with a rich density of glucocorticoid receptors – so as to consolidate especially stressful memories. The Papez circuit and the basolateral limbic loop (mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus, subcallosal area, amygdala, and interconnecting fiber) are also involved. The Papez and the basolateral limbic circuit represent a group of “bottleneck structures” that are interconnected and of high relevance for the extraction of the affective, somatosensorial, and social significance of new incoming information (Markowitsch & Staniloiu, 2012). In contrast, when damage involves just the semantic memory system, especially of the hippocampus, patients may forget personal facts and beliefs – where and when they were born, details of their physical appearance, but their anoetic self remains relatively intact (Vandekerckhove et al., 2014).

4 – profound: speech usually unintelligible or irrelevant; unable to follow simple instructions or comprehend commands; only occasionally recognition their spouse or caregiver; use fingers more than utensils or required much assistance to eat; frequently incontinent; usually chair-bound; rarely out of their residence; limb movements were often purposeless

5 – terminal: no comprehension or recognition, need to be fed or had tube feedings, totally incontinent, bedridden.

As regards the non-pharmacologic treatment of the mild and moderate stages of MaNCDs, the cognitive stimulation is an valid resource (Baldelli et al., 1993; Paggetti et al., 2024).

Following the retrogenesis of memory, the cognitive stimulation will adapt to the impaired handling and writing abilities and to the difficulty to cope with of the PwMaNCD until they will be entirely loosed, usually in the severe stage.

4.5. The Socio-Psychological Domain

The progressive impairment of limbic system, particularly the disconnection from frontal lobes, amygdala, is responsible of the continuum of the progressive deterioration of social cognition due to compromise of critics and judgment and the emergence of infantile uncontrolled behaviors (Braak & Del Tredici-Braak, 2015).

Before examining the manifestations of retrogenesis on the individual niche formed by adult social cognition, some caveats require attention. The caveats regard the biologic difference among the retrieval of infantile uncontrolled behaviors of the PwMaNCD and the infant-child:

the PwMaNCD weights usually more than 50 Kg and has the strength of an adult;

the long-life developments and storage of millions of events, images, phantasies, thoughts and behaviors that fill the empty bookcases of the infant mind, building the adult’s EAM, progressively ruin out of the control from the AuMC, impacting, often disastrously, on the psychic sphere of the PwMaNCD, progressively deprived of critic/judgment and management;

the gender may condition the behaviour and manifestations of the PwMaNCD: for-example females are more prone to depression while males to sexual disinhibition (Pillai et al., 2022; Resnick et al., 2021).

The retrogenetic manifestations and symptoms of the psychological domain are usually assessed with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) (Cummings, 1997).

The retrogenetic behavioral disorders affect the PwMaNCD from the mild stage (CDR 1) and increase along the moderate stage (CDR 2) reaching a peak, as severity, daily frequency and intensity, in the severe stage (CDR 3) (

Figure 14) (Cheng et al., 2009; R. S. Nelson et al., 2023; C. Thompson et al., 2010). As demonstrated before, these disorders appear in the reversal order of the development of limbic system starting with the decoupling of the amygdala in CDR1 (i.e., depression) then of the NbM and prefrontal cortex (i.e., fears, delusions) in CDR 2 and finally of the SCN and HTPAG axis in CDR 3 (i.e., sundowning syndrome, wandering, aggression, disruption of the biological clock and circadian rhythm and so on) (Kabeshita et al., 2017; Laganà et al., 2022)

The hallucinations are one hallmark of the retrogenetic psychological symptoms, frequent in the severe stage, that may be reconducted to the child mind prone to believe in phantasies on which relies the fairy tales, comics, toys, movies, feasts (i.e., the Disney world, flying witches, Santa Klaus flying with the reindeers…). These images and fantasies are progressively controlled from the frontal development of critic and judgement that permits to the adult to create an organized mind control and, when waken, a voluntary management of images and fantasies separating them from reality. Example of the organized adult fantasies may be better understood with old examples like the pharaohs’ Egyptian religion, the masks of the Greek tragedies, Homeric, Dantesque and medieval poems and all the ancient and old beliefs that the progress has disavowed. The difference with infant-child fantasies is that in the PwMaNCD the voluntary fences of mind control of adult’ memories are disrupted and the fantasies, imagines and sounds float decoupled from the EAM/AuMC.

The CDR 3 may be considered the transitional stage from the last fragments of EAM/AuMC to the resurface of AnBC from the “basement” of infancy. A well detailed list of the retrogenetic symptoms in this stage is provided by the Nursing Home Behavior Problem Scale (Ray et al., 1992).

The definitive loss of EAM/AuMC and transition in AnBC (CDR 3 versus CDR 4) may be empirically recognized when the PwMaNCD loses definitely the mothers’ name (Pfeiffer, 1975), even if for some times will continue to search for “my mom” and “my house” not corresponding to the real memories but to the ontogenetic infant/pup survival fears to be left alone and to need a nest.

Moreover, parallelly to the permanent amnesia of mother’s name, the entrance in the AnBC phase (CDR 4) is usually coupled with progressive amnesia for walking that begins with impairment in balance and gait and related falls, often traumatic, until total loss of walking and permanent use of a wheelchair. The CDR 4 may be initially characterized by disinhibition, resistiveness, combativeness and aggression. Then there is a reduction and changing of behavioral disturbances that are more related to the violation of the AnBC for hygiene, dressing, management of incontinence, feeding. In CDR 4 the PwMaNCD do not recognize the semantic meaning of the meals that become “things” not more recognized as foods, moreover in absence or reduction of the stimuli of thirst and hunger and with the mouth forced by unsweet “things”. As a rule, the infant is mainly prone to sweet and creamy “things” and frequently reacts against unsweet and grainy “things” during the weaning. Similarly to infant, the PwMaNCDs may become uncooperative and/or refuse to feed feeling these actions as a forced introduction in mouth of unsweet and grainy “things” thus miming the conflictual period of the weaning like an oppositional defiant disorder but with the strength of an adult not of an infant/child (Rowe et al., 2010). During the course of CDR 4 the behavioral symptoms usually attenuate and reduce progressively to sleep disorders and sometimes permanent disrupting vocalization. The transition from CDR 4 to the bedridden CDR 5 stage is marked from the inability to maintain the control of the trunk when seated that is reached from the infant at 9 months after birth. In the CDR 5, the behavioral symptoms are sometimes sleep disorders and vocalization that usually tend to cease.

There are many aspects that support the retrogenesis of the limbic system as the cause of the socio-behavioral manifestations of the NCDs (

Figure 15) (Laganà et al., 2022):

the time of onset is different depending on the diverse etiologies of the NCDs but the types and trajectories of symptoms appears along an overlapping pattern;

-

the overlapping pattern of socio-behavioral manifestations may be embodied in a time neurobiological algorithm:

I preclinical - 3 years: symptoms related originally to the involvement of the prefrontal-basal forebrain-amygdala-HTPAG axis (Pecher et al., 2024) circuit and interesting before the mood (depression, apathy, anxiety, euphoria) and then, after some years, the temperament (irritability, disinhibition, agitation, aggression);

II 3 - 5 years: the worsening of the prefrontal-basal forebrain-amygdala-HTPAG axis circuit implies symptoms related to the progressive loss of control on the sensorial and semantic inputs (fears, delusion, hallucination) (Gottesman & Stern, 2019) while the detachment of the molecular clock and the neurovisceral inputs of hungry and thirsty implies the disruption of the circadian rhythm for sleeping and eating;

III > 5 years: the complete detachment of the prefrontal-basal forebrain-amygdala-HTPAG axis circuit from the lower hippocampal circuit implies the resurface from the “basement” of AnBC of the aberrant motor behavior-wandering of the child followed by the loss of gait and balance of the infant then by the chair-bounded period until to the bedridden-vegetative after birth stage;

the stressful and disabling socio-behavioral manifestations like agitation, sleep and eating disorders affect about 40-50% (Sano et al., 2024) but not all the PwMaNCDs as expected if they should be entirely provoked from the MaNCDs (Kwon & Lee, 2021). This aspect is likely due to the resurface of the infant’s original temperament of the PwMaNCD, frequently quite different from his adult acquired behaviour, as referred from the caregivers, both in male and females. It is a common experience that infant/child temperament expresses itself like a Gaussian curve whose extremes are: always calm and collaborative and always agitated and oppositive. So, it may be reasonable to presume that the PwMaNCDs with a “benign” calm and collaborative behavior or a “disruptive” behavior may recover their original infant-child one’s;

the non-pharmacologic therapies for the socio-behavioral manifestations of NCDs are applied following the decreasing level of cognitive functioning of the PwMaNCDs. In the mild and moderate stages it is possible to supply the stimulation of cognition, abilities and plays (reality orientation therapy, exercises, drawings, music therapy... (Baldelli et al., 1993; Bleibel et al., 2023; Mapelli et al., 2013) in the severe and profound stages mainly play (dolls/pet therapy, elder-clowning, (Kontos et al., 2016; Pezzati et al., 2014)..) and sensory memory stimuli (Snoezelen rooms (Berkheimer et al., 2017; Hulsegge & Verheul, 1987; Lotan & Shapiro, 2005; Staal et al., 2007; Testerink et al., 2023) . This pattern is the opposite to the infant-child development that start with the sensory memory stimuli and play before to acquire the abilities (

Figure 15).

4.6. The Socio-Functional Domain

The retrogenetic impairment of socio-functional domain is examined crossing the NCD neuropathological staging protocol for NFTs/NTs proposed by Braak (Braak & Braak, 1991) with the CDR. The NFTs stages III and IV correspond to the CDR 1 (

Figure 16). In these stages the lesions reach the hippocampal formation (NFT stage III) and neocortical areas of the basal temporal lobe that adjoin the transentorhinal region laterally. Thereafter, the process encroaches upon anterior cingulate, insular, and more distant neocortical destinations of the basal temporal lobe (NFT stage IV). Clinically, the PwMaNCD has difficulties solving simple arithmetical or abstract problems, short-term memory or recall deficits and shows changes affecting social cognition, community affairs, home and hobbies and needs prompting for personal care (Braak & Del Tredici-Braak, 2015; Therriault et al., 2022)

The NFTs Stages V and VI correspond to CDR 2 and 3

Figure 16). The tau pathology spreads superolaterally (NFT stage V) and finally reaches the primary neocortical motor and sensory fields devasting the neocortex (NFT stage VI) (Braak et al., 2006) .

Functionally, the final NFTs stages V and VI correspond to a fully developed AD where the PwMaNCDs become totally incontinent, cannot dress themselves unaided, or recognize persons once familiar to them (spouse, children). With the passage of time, they can no longer walk, sit up, or hold up their head unassisted. Increasing rigidity of the large joints leads to irreversible contractures of the extremities and immobility. Primitive reflexes, normally seen only in infants, also reappear in the terminal stage of the major NCD (Reisberg, Franssen, et al., 1999).

5. Discussion

This description of the infant anoesis (AnBC) and its transition in the adult autonoesis (EAM-AuMC) in the light of the individual biosphere, add a contribution from a multidimensional person-centered point of view to the Reisberg’s retrogenesis system of the progression of the MaNCDs.

The AnBC is strongly connected to raw sensorial and perceptual abilities, to various subcortical affective processes, and intrinsic affective value structures that take place into the limbic and paralimbic structures.

The emergence of EAM/AuMC in childhood is coupled with the progressive stabilization of the biological clock that regulates the circadian rhythms for sleep-wake, hormone production, and importantly, memory.

The EAM is “.. a past- and future-oriented, context embedded neurocognitive memory system that receives and stores information about temporally dated episodes or events, and temporal-spatial relations among them from one’s past” (Tulving, 1984, 2024).

The EAM differs from other forms of memory because requires an extended sense of self that engage in mental time-travel.

Time awareness and orienting are related especially to the prefrontal cortex, while the proper perception of time and time epochs seems to engage the parietal cortex as well as the diencephalic structures.

When considering the BPS and functional retrogenetic cascade, some considerations and details may be of interest for a multidimensional person-centered model.

The development of cognition and knowledge from birth to adulthood is due to the progressive two-stage maturation of the whole limbic system: firstly, the infant AnBC and then the adult EAM/AuMC where AnBC is embedded in EAM/AuMC as a continuum.

The genetic absence of EAM/AuMC in infancy is the key point that permits the acquisition of the anoetic but voluntary body control and consciousness to every newborn.

The growing functioning of EAM/AuMC in the child-adolescence period is the basis for the development of the “self” after the AnBC and not together.

In the retrogenesis, the impairment of the cognitive, psycho-behavioral and functional symptoms of the MaNCDs is progressive and interconnected because expression of the reversal progressive impairment of the individual adult biosphere.

The overlapping of the cohort of cognitive, psycho-behavioral and functional symptoms of the MaNCDs is substantial independently from the etiopathogenesis and due to a retrogenetic impairment of the limbic system.

The actual etiopathogenesis of the MaNCDs, correlated prevalently to the damage of hippocampus, is restrictive and inadequate to explain the galaxy of overlapping manifestations and symptoms of the MaNCDs.

Many neuropathologic studies have demonstrated the involvement of amygdala, basal forebrain nuclei and frontal cortex as responsible of the retrogenetic psychological and behavioral symptoms of MaNCDs (apathy, depression, anxiety), frequently anticipatory of the amnesic symptoms.

This remark outlines the necessity to treat always the depression to prevent MaNCDs (Livingston et al., 2024).

Moreover, the involvement of the suprachiasmatic nuclei (the molecular clock) and of the HTPAG axis is responsible for sleeping and eating frequently concomitant with the amnesic symptoms.

The long-term body memories acquired with the AnBC remain stocked for life in a “basement” fundamental nucleus over which progressively develops the continuum of the intertwined blocks of the EAM/AuMC. In the BPS retrogenesis the EAM/AuMC vanishes along the mild, moderate and severe stages of MaNCDs and remains only the “basement” AnBC that vanishes too losing progressively the ADL in a retrogenetic order of acquisition where the last one function to be deleted is chewing and swallowing.

The eating together with chewing disorders of the advanced stages of MaNCDs are solved with the infant creamy sweet foods until the swallowing memory is evocable from the AnBC of the PwMaNCD.

The multidimensional comprehensive geriatric assessment may represent a core that unifies the evaluation of the PwMaNCDs in their BPS and functional retrogenesis as a global continuum, not limited only to the illness.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Heikko Braak and Prof. Kelly Del Tredici for the permission to use parts of their pioneering scientific works in the field of cognition and the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Prof. Nim Tottenham for the permission to use parts of his outstanding works on the amygdala. Prof. Mirco Neri, scientiae et vitae magister. In memory of Prof. Gian Paolo Vecchi and Prof. Luciano Belloi, scientiae et vitae magistri.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interes

Abbreviations

| AD: |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| ADL: |

Activities of Daily Living: |

| AnBC: |

Anoetic Body Consciousness |

| ARAS: |

ascending reticular activating system |

| AuMC: |

Autonoetic Mind Consciousness |

| Braaks NFTs-ST: |

Braaks NFTs staging tool |

| BPSD: |

Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms of Dementia |

| BPS: |

Biopsychosocial (pathway) |

| bvFTD: |

behavioral variant of Frontotemporal dementia |

| CNS: |

Central Nervous System |

| CDR: |

Clinical Dementia Rating scale |

| DAEs: |

Developmental Age Equivalents |

| EAM: |

Episodic-Autobiographical Memory |

| EN: |

enteral nutrition |

| FAST: |

Functional Assessment Staging Tool |

| FTD: |

Frontotemporal dementia |

| GDS: |

Global Deterioration Scale |

| HPTAG axis: |

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal-gonadal axis |

| IA: |

Infantile Amnesia |

| IADL: |

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| NbM: |

nucleus basalis of Meynert |

| NCD: |

Neurocognitive Disorder |

| Major NCD: |

MaNCD |

| NFTs |

neurofibrillary tangles |

| NPI: |

Neuropsychiatric Inventory |

| PN: |

parenteral nutrition |

| PwMaNCD: |

Person affected with Major Neurocognitive Disorder |

| ROT: |

Reality Orientation Therapy |

| RSN: |

resting-state networks |

| SCN: |

Suprachiasmatic Nuclei |

References

- Aghourian, M.; Legault-Denis, C.; Soucy, J.P.; Rosa-Neto, P.; Gauthier, S.; Kostikov, A.; Gravel, P.; Bedard, M.A. Quantification of brain cholinergic denervation in Alzheimer’s disease using PET imaging with [18F]-FEOBV. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberini, C.M.; Travaglia, A. Infantile Amnesia: A Critical Period of Learning to Learn and Remember. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 5783–5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.M. (2014). Postnatal testosterone concentrations and male social development. In Frontiers in Endocrinology (Vol. 5, Issue FEB). Frontiers Research Foundation. [CrossRef]

- Alves, G.S.; Oertel Knöchel, V.; Knöchel, C.; Carvalho, A.F.; Pantel, J.; Engelhardt, E.; Laks, J. Integrating retrogenesis theory to Alzheimer’s disease pathology: insight from DTI-TBSS investigation of the white matter microstructural integrity. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 291658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-5 2013, 5th edn. Washington, DC.

- Amrein, I.; Isler, K.; Lipp, H. Comparing adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mammalian species and orders: influence of chronological age and life history stage. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.B.; Cindy Struckman, C. (Eds.) (1998). Sexually Aggressive Women: Current Perspectives and Controversies.

- Auer, S.; Reisberg, B. The GDS/FAST staging system. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1997, 9 (Suppl. S1), 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, M.V.; Pirani, A.; Motta, M.; Abati, E.; Mariani, E.; Manzi, V. Effects of reality orientation therapy on elderly patients in the community. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1993, 17, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bath, K.G.; Manzano-Nieves, G.; Goodwill, H. Early life stress accelerates behavioral and neural maturation of the hippocampus in male mice. Horm. Behav. 2016, 82, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautmans, I.; Knoop, V.; Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan, J.; Maier, A.B.; Beard, J.R.; Freiberger, E.; Belsky, D.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Mikton, C.; Cesari, M.; et al. (2022). WHO working definition of vitality capacity for healthy longevity monitoring. In The Lancet Healthy Longevity (Vol. 3, Issue 11, pp. e789–e796). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Becker, P.M.; Cohen, H.J. The Functional Approach to the Care of the Elderly. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1984, 32, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsky, J. , Caspi, A., Moffit, T.E.M., & Poulton, R. (2020). The Origins of You. Harvard University Press.

- Berkheimer, S.D.; Qian, C.; Malmstrom, T.K. Snoezelen Therapy as an Intervention to Reduce Agitation in Nursing Home Patients With Dementia: A Pilot Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 1089–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessières, B.; Travaglia, A.; Mowery, T.M.; Zhang, X.; Alberini, C.M. Early life experiences selectively mature learning and memory abilities. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleibel, M.; El Cheikh, A.; Sadier, N.S.; Abou-Abbas, L. The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Alafuzoff, I.; Arzberger, T.; Kretzschmar, H.; Del Tredici, K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006, 112, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991, 82, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Development of Alzheimer-related neurofibrillary changes in the neocortex inversely recapitulates cortical myelogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 1996, 92, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 1996, 94 (Suppl. S165), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. (1999). Neuropathological stages of Alzheimer’s disease. In Mony J. de Leon (Ed.), An Atlas of Alzheimer’s Disease (pp. 57–74). The Parthenon Publishing Group.

- Braak, H.; Braak, E.; Yilmazer, D.; Bohl, J. (1996). Functional anatomy of human hippocampal formation and related structures. In Journal of Child Neurology (Vol. 11, Issue 4, pp. 265–275). BC Decker Inc. [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici, K. The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 121, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Del Tredici-Braak, K. (2015). Alzheimer’s Disease, Neural Basis of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition (pp. 591–596). Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Thal, D.R.; Ghebremedhin, E.; Tredici, K. Del. (2011). Stages of the Pathologic Process in Alzheimer Disease: Age Categories From 1 to 100 Years, 2917; https://academic.oup.com/jnen/article-abstract/70/11/960/2917408. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, U.; Schäfer, A.; Walter, H.; Erk, S.; Romanczuk-Seiferth, N.; Haddad, L.; Schweiger, J.I.; Grimm, O.; Heinz, A.; Tost, H.; et al. Dynamic reconfiguration of frontal brain networks during executive cognition in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States Am. 2015, 112, 11678–11683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciatore, R.; Korteniemi-Poikela, E.; Kaltiala, R. The Steps of Sexuality—A Developmental, Emotion-Focused, Child-Centered Model of Sexual Development and Sexuality Education from Birth to Adulthood. Int. J. Sex. Health 2019, 31, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camina, E.; Güell, F. (2017). The neuroanatomical, neurophysiological and psychological basis of memory: Current models and their origins. In Frontiers in Pharmacology (Vol. 8, Issue JUN). Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, G.; Sylos-Labini, F.; Dewolf, A.H.; Solopova, I.A.; Morelli, D.; Lacquaniti, F.; Ivanenko, Y. Maturation of the Locomotor Circuitry in Children With Cerebral Palsy. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, E.; Riccardi, A.; Marinetto, S.; Mattivi, S.; Selini, E.; Pucci, V.; Mondini, S. Over ninety years old: Does high cognitive reserve still help brain efficiency? Psychol. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.; Justin, H.S.; Gulick, D.; Gamsby, J.J. The Molecular Clock and Neurodegenerative Disease: A Stressful Time. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesari, M.; De Carvalho, I.A.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Martin, F.C.; Reginster, J.Y.; Vellas, B.; Beard, J.R. (2018). Evidence for the domains supporting the construct of intrinsic capacity. In Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences (Vol. 73, Issue 12, pp. 1653–1660). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Figueroa, J.; Shaikh, S.; Mays, E.W.; Bayakly, R.; Javed, M.; Smith, M.L.; Moran, T.P.; Rupp, J.; Nieb, S. Pediatric falls ages 0–4: understanding demographics, mechanisms, and injury severities. Inj. Epidemiol. 2018, 5, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.-W.; Chen, T.-F.; Yip, P.-K.; Hua, M.-S.; Yang, C.-C.; Chiu, M.-J. Comparison of behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease among institution residents and memory clinic outpatients. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child Sexual Abuse Committee. (2009). Information for Parents and Caregivers Sexual Development and Behavior in Children. National Child Traumatic Stress Network. http://nctsn.org/nctsn_assets/pdfs/caring/sexualbehaviorproblems.pdf.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. (2000). Heterogeneity in Dementia: Challenges and Opportunities.

- Cuevas, K.; Sheya, A. Ontogenesis of learning and memory: Biopsychosocial and dynamical systems perspectives. Dev. Psychobiol. 2019, 61, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.L. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Neurology 1997, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dafni-Merom, A.; Arzy, S. The radiation of autonoetic consciousness in cognitive neuroscience: A functional neuroanatomy perspective. Neuropsychologia 2020, 143, 107477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafni-Merom, A.; Arzy, S. The radiation of autonoetic consciousness in cognitive neuroscience: A functional neuroanatomy perspective. Neuropsychologia 2020, 143, 107477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and selection in relation to sex. John Murray.

- Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. John Murray.

- De Vriendt, P.; Gorus, E.; Cornelis, E.; Bautmans, I.; Petrovic, M.; Mets, T. The advanced activities of daily living: A tool allowing the evaluation of subtle functional decline in mild cognitive impairment. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, A.L.; Erickson, K.J.; Shiers, S.I.; Burman, M.A. Limbic system development underlies the emergence of classical fear conditioning during the third and fourth weeks of life in the rat. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 130, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, D. The Primordial Emotions. The dawning of consciousness. Oxford University Press, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Denton, D.A.; McKinley, M.J.; Farrell, M.; Egan, G.F. The role of primordial emotions in the evolutionary origin of consciousness. Conscious. Cogn. 2009, 18, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, D.; Shade, R.; Zamarippa, F.; Egan, G.; Blair-West, J.; McKinley, M.; Lancaster, J.; Fox, P. Neuroimaging of genesis and satiation of thirst and an interoceptor-driven theory of origins of primary consciousness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999, 96, 5304–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, B.C.; Eichenbaum, H. (2010). The episodic memory system: Neurocircuitry and disorders. In Neuropsychopharmacology (Vol. 35, Issue 1, pp. 86–104). [CrossRef]

- Dooneief, G.; Marder, K.; Tang, M.X.; Stern, Y. The Clinical Dementia Rating scale: community-based validation of “profound’’ and ‘terminal’’ stages. ’” Neurology 1996, 46, 1746–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dykiert, D.; Der, G.; Starr, J.M.; Deary, I.J. Why is Mini-Mental state examination performance correlated with estimated premorbid cognitive ability? Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, G.M.; Tononi, G. (2000). A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination. Basic Books.

- Ellis, C.T.; Skalaban, L.J.; Yates, T.S.; Bejjanki, V.R.; Córdova, N.I.; Turk-Browne, N.B. Evidence of hippocampal learning in human infants. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 3358–3364.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am. J. Psychiatry 1980, 137, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, G.L. The Biopsychosocial Model and Medical Education. New Engl. J. Med. 1982, 306, 802–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. From biomedical to biopsychosocial: I. Being scientific in the human domain. Fam. Syst. Health 1996, 14, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.R.; Lankford, A. Femcel Discussions of Sex, Frustration, Power, and Revenge. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2024, 53, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewers, M.; Frisoni, G.B.; Teipel, S.J.; Grinberg, L.T.; Amaro, E.; Heinsen, H.; Thompson, P.M.; Hampel, H. Staging Alzheimer’s disease progression with multimodality neuroimaging. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 95, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, T.D.; Moore, Z.T.; Pittenger, M.J. Sex on the brain? An examination of frequency of sexual cognitions as a function of gender, erotophilia, and social desirability. J. Sex Res. 2012, 49, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fivush, R.; Nelson, K. (2004). Culture and Language in the Emergence of Autobiographical Memory.

- Folstein, M.F. , Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state.” J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, E.H.; Souren, L.E.; Torossian, C.L.; Reisberg, B. Utility of developmental reflexes in the differential diagnosis and prognosis of incontinence in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 1997, 10, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. (1914). Psychopathology of Everyday Life, The Macmillan Company.

- Galvin, J.E. The Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS): A rapid dementia staging tool. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2015, 1, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambaro, E.; Gramaglia, C.; Azzolina, D.; Campani, D.; Dal Molin, A.; Zeppegno, P. (2022). The complex associations between late life depression, fear of falling and risk of falls. A systematic review and meta-analysis. In Ageing Research Reviews (Vol. 73). Elsevier Ireland Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Gartstein, M.A.; Rothbart, M.K. (2003). Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. In Infant Behavior & Development (Vol. 26).

- Godfrey, M.; Casnar, C.; Stolz, E.; Ailion, A.; Moore, T.; Gioia, G. A review of procedural and declarative metamemory development across childhood. Child Neuropsychol. 2023, 29, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogtay, N.; Giedd, J.N.; Lusk, L.; Hayashi, K.M.; Greenstein, D.; Vaituzis, A.C.; Nugent, T.F.; Herman, D.H.; Clasen, L.S.; Toga, A.W.; et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8174–8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogtay, N.; Thompson, P.M. Mapping gray matter development: Implications for typical development and vulnerability to psychopathology. Brain Cogn. 2010, 72, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, G.; Bouras, C.; Kövari, E.; Canuto, A.; González Glaría, B.; Malky, A.; Hof, P.R.; Michel, J.-P.; Giannakopoulos, P. Clinical validity of Braak neuropathological staging in the oldest-old. Acta Neuropathol. 2000, 99, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, D.M.; Berent, I.; Benavides-Varela, S.; Bion RA, H.; Cattarossi, L.; Nespor, M.; Mehler, J. Language universals at birth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 5837–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, R.T.; Stern, Y. Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia and rate of decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Gow, A.J.; Johnson, W.; Pattie, A.; Whiteman, M.C.; Starr, J.; Deary, I.J. Mental Ability in Childhood and Cognitive Aging. Gerontology 2008, 54, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, D.S.; Fair, D.A. Development of large-scale functional networks from birth to adulthood: A guide to the neuroimaging literature. NeuroImage 2017, 160, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grober, E.; Qi, Q.; Kuo, L.; Hassenstab, J.; Perrin, R.J.; Lipton, R.B. Stages of Objective Memory Impairment Predict Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathology: Comparison with the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale–Sum of Boxes. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 80, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hering E (1870) Ueber das Gedächtnis als eine allgemeine Funktion der organisierten Materie Vortrag gehalten in der feierlichen Sitzung der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien am, X.X.X. Mai MDCCCLXX (Transl.: Memory as a general function of organized matter. Chicago: Open Court).

- Hood, T. ; Price J (2011) Infantile amnesia in human nonhuman animals In, M.L. Howe (Ed.), The Nature of Early Memory: An Adaptive Theory of the Genesis and Development of Memory (pp. 47–66). Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Hortensius, R.; Terburg, D.; Morgan, B.; Stein, D.J.; van Honk, J.; de Gelder, B. The basolateral amygdalae and frontotemporal network functions for threat perception. ENeuro 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulsegge, J.; Verheul, A. (1987). Snoezelen: Another World. ROMPA.

- Hume D (1739) A treatise of human nature: an attempt to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects, (.J. Noon, Ed.; Vols. 1, 2, 3). White-Hart.

- Hutson, M. Basic instincts. Science 2018, 360, 845–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janak, P.H.; Tye, K.M. (2015). From circuits to behaviour in the amygdala. In Nature (Vol. 517, Issue 7534, pp. 284–292). Nature Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Liu, T.; Crawford, J.D.; Kochan, N.A.; Brodaty, H.; Sachdev, P.S.; Wen, W. Stronger bilateral functional connectivity of the frontoparietal control network in near-centenarians and centenarians without dementia. NeuroImage 2020, 215, 116855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jicha, G.A.; Parisi, J.E.; Dickson, D.W.; Johnson, K.; Cha, R.; Ivnik, R.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Braak, H.; et al. Neuropathologic Outcome of Mild Cognitive Impairment Following Progression to Clinical Dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabeshita, Y.; Adachi, H.; Matsushita, M.; Kanemoto, H.; Sato, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshiyama, K.; Shimomura, T.; Yoshida, T.; Shimizu, H.; et al. Sleep disturbances are key symptoms of very early stage Alzheimer disease with behavioral and psychological symptoms: a Japan multi-center cross-sectional study (J-BIRD). Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Ford, A.B.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Jackson, B.A.; Jaffe, M.W. Studies of Illness in the Aged: The Index of ADL: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA 1963, 185, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.B.; Gangi, C.E. (2010). The multiplicity of self: Neuropsychological evidence and its implications for the self as a construct in psychological research. In Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (Vol. 1191, pp. 1–15). Blackwell Publishing Inc. [CrossRef]

- Kontos, P.; Miller, K.L.; Colobong, R.; Palma Lazgare, L.I.; Binns, M.; Low, L.F.; Surr, C.; Naglie, G. Elder-clowning in long-term dementia care: Results of a pilot study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]