Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

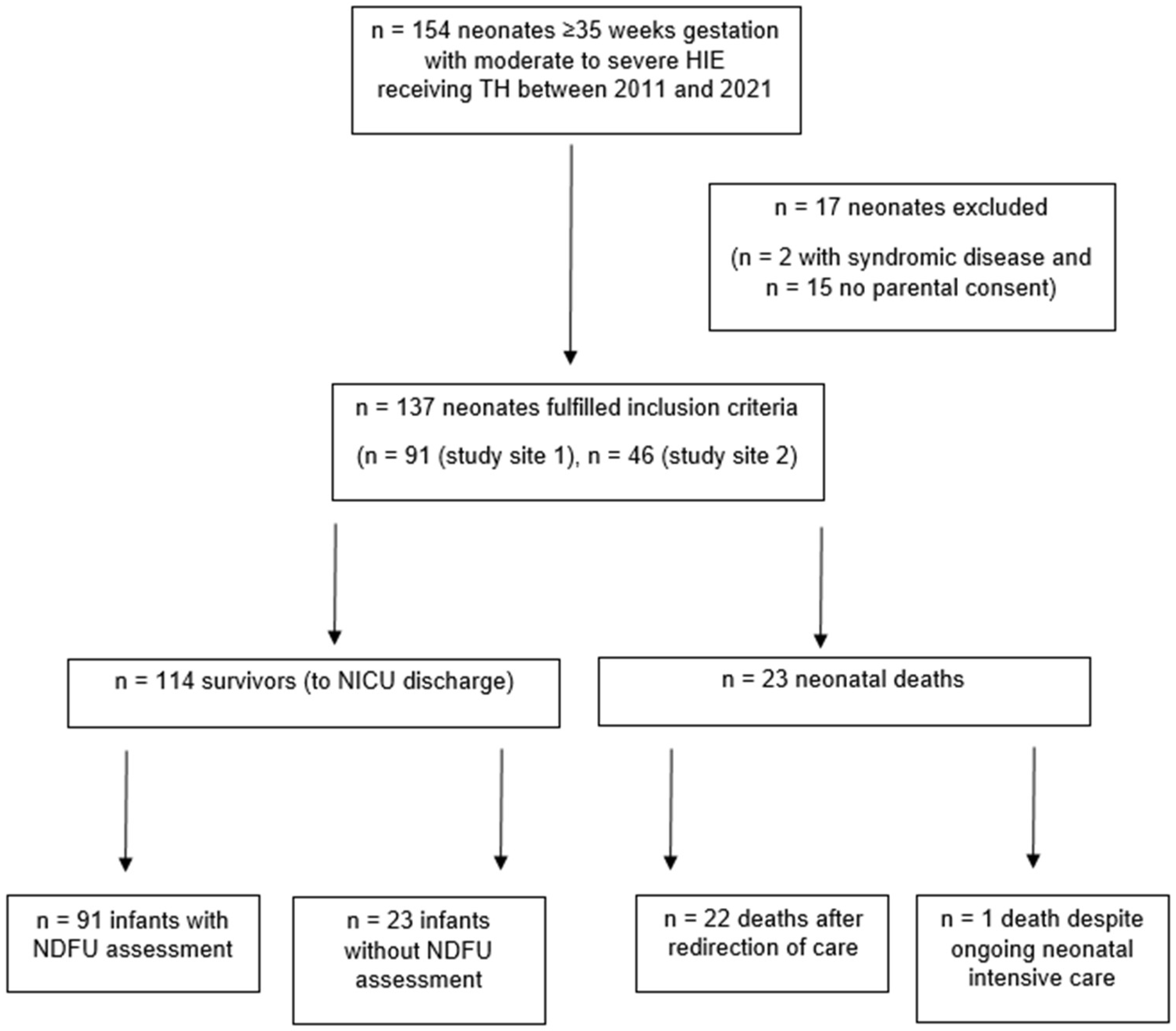

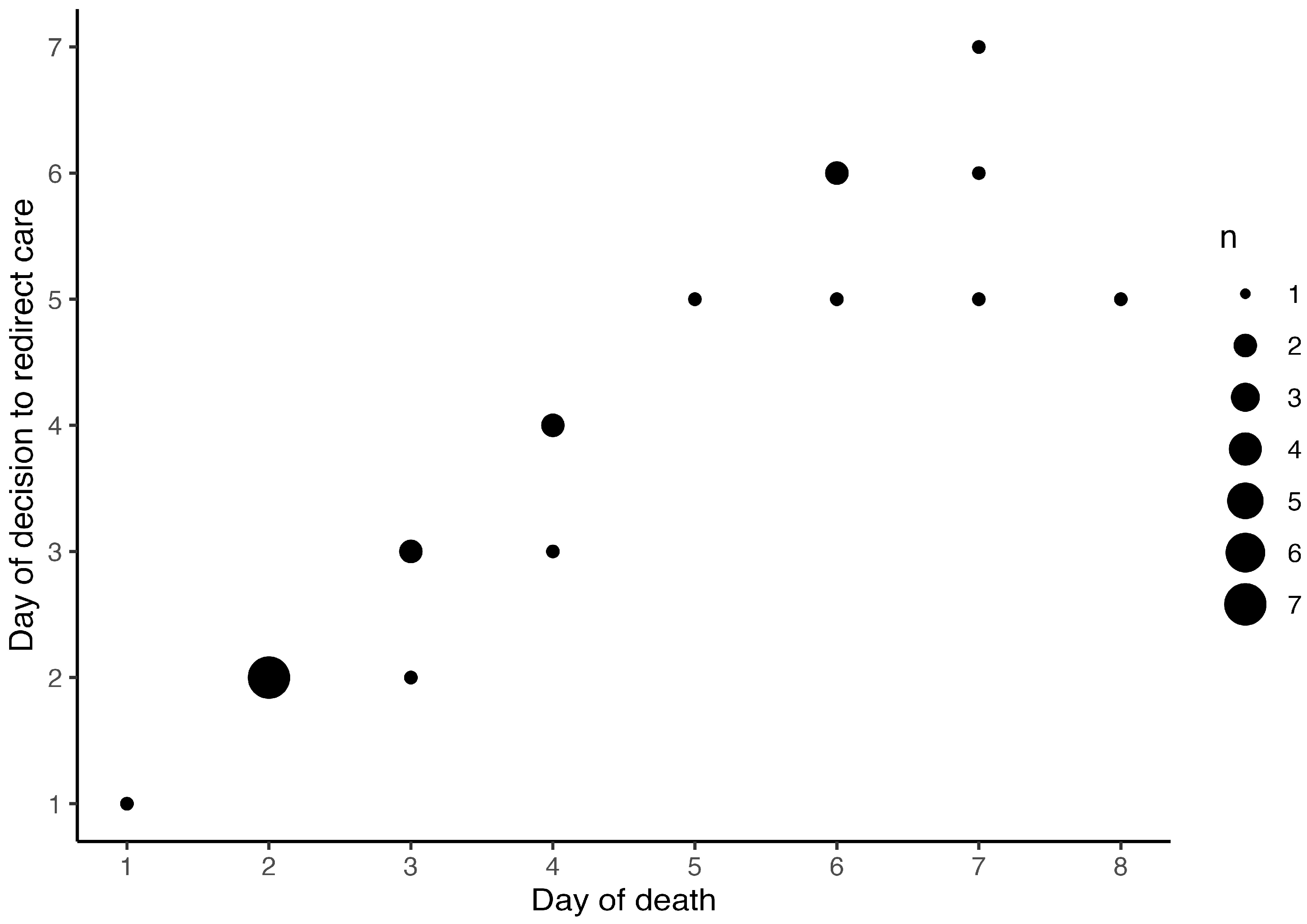

Background/Objectives: Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) in (near)term neonates accounts for neonatal mortality and unfavorable neurodevelopmental outcome in survivors, despite therapeutic hypothermia (TH) for neuroprotection. The circumstances of death in neonates with HIE and involvement of neonatal palliative care (NPC) specialists warrant further evaluation. Methods: Retrospective multicenter cohort study including neonates ≥ 35 weeks gestational age with moderate to severe HIE receiving TH, registered in the Swiss National Asphyxia and Cooling Register between 2011 and 2021. Neurodevelopmental follow-up at 18-24 months in survivors was assessed. The groups of survivors and deaths were compared regarding perinatal demographic and HIE data. Prognostic factors leading to redirection of care (ROC) were depicted. Results: 137 neonates were included, 23 (16.8%) deaths and 114 (83.2%) survivors. All but one death (95.7%) occurred after ROC with death on median 3.5 (2-6) days of life. Severe encephalopathy indicated by Sarnat score 3 on admission and seizures were more frequent, and blood lactate values were higher on postnatal days 1 to 4 in neonates who died. Lactate in worst blood gas analysis (unit aOR 1.25, 95% CI 1.02-1.54, p=0.0352) was the only variable independently associated with ROC. NPC specialists were involved in one case. Of 114 survivors, 88 (77.2%) had neurodevelopmental assessments, and 21 (23.9%) of those had unfavorable outcome (moderate to severe disability). Conclusions: Death in neonates with moderate to severe HIE receiving TH almost exclusively occurred after ROC. Parents thus had to take critical decisions and accompany their neonate at end-of-life within the first week of life. To ensure continuity of care for the family, also beyond the death of the neonate, involvement of NPC specialists is encouraged in ROC.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Severe clinical neurological abnormalities, reflected in persistent Sarnat score 2 and 3 [11],

- Death or

- Severe disability, defined as a CCS, LCS or MCS (BSID-III) or one Griffiths developmental quotient more than 2 SD below the mean score (i.e. < 70), or a GMFCS grade of level 3 to 5, or hearing impairment (inability to follow commands despite amplification) or blindness or

- Moderate disability, defined as a CCS, LCS or MCS (BSID-III) or one Griffiths developmental quotient of 1 to 2 SD below the mean score (i.e. 70 to 84) in addition to one or more of the following: GMFCS grade of level 2, hearing impairment (hearing deficit with the ability to follow commands after amplification) or persistent seizure disorder.

- Mild disability, defined as a CCS, LCS or MCS (BSID-III) or one Griffiths developmental quotient of 70-84 alone, or CCS or LCS ≥ 85 and GMFCS level 1 or 2, seizure disorder without anti-epileptic medication or hearing deficit with ability to follow commands with amplification or

- No disability: Absence of previously listed disabilities.

3. Results

3.1. Participants and descriptive data

3.2. Outcome data and main results

| Table 3. b. Depiction of prognostic factors in cases of death. | |||||||||||||

| Case | Death | EEG | Seizure | cMRI | cUS | Sarnat score | ROC | Death (DOL) | |||||

| despite maximal support | after ROC | on admission | DOL 1 | DOL 2 | DOL 3 | Decision (DOL) | Execution (DOL) | ||||||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| 10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 14 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 15 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 17 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 18 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 20 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

| 21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 22 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| 23 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

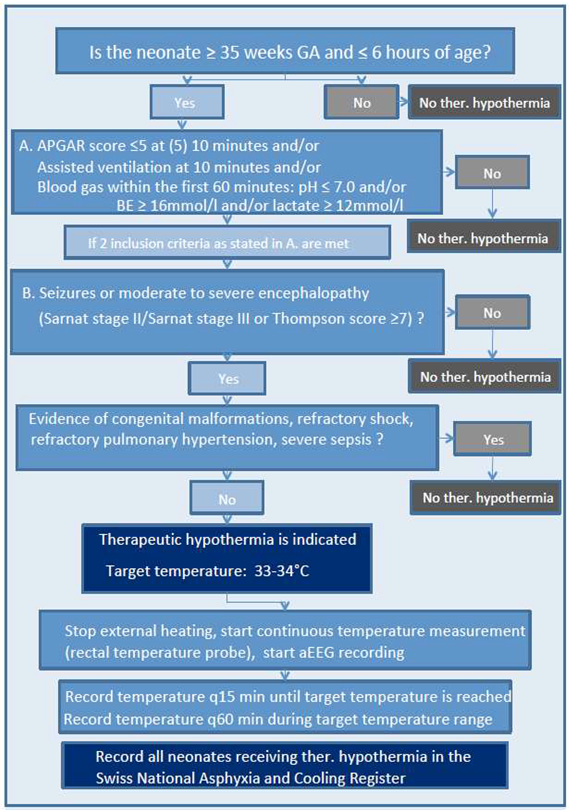

Appendix A. Swiss National Asphyxia and Cooling Flowchart

References

- Jacobs, S.E.; Berg, M.; Hunt, R.; Tarnow-Mordi, W.O.; Inder, T.E.; Davis, P.G. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD003311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Tyson, J.E.; McDonald, S.A.; Donovan, E.F.; Fanaroff, A.A.; Poole, W.K.; Wright, L.L.; Higgins, R.D.; et al. Whole-Body Hypothermia for Neonates with Hypoxic–Ischemic Encephalopathy. New Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankaran, S.; Pappas, A.; McDonald, S.A.; Vohr, B.R.; Hintz, S.R.; Yolton, K.; Gustafson, K.E.; Leach, T.M.; Green, C.; Bara, R.; et al. Childhood Outcomes after Hypothermia for Neonatal Encephalopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2085–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, D.V.; Strohm, B.; Edwards, A.D.; Dyet, L.; Halliday, H.L.; Juszczak, E.; Kapellou, O.; Levene, M.; Marlow, N.; Porter, E.; et al. Moderate Hypothermia to Treat Perinatal Asphyxial Encephalopathy. New Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzopardi, D.; Strohm, B.; Marlow, N.; Brocklehurst, P.; Deierl, A.; Eddama, O.; Goodwin, J.; Halliday, H.L.; Juszczak, E.; Kapellou, O.; et al. Effects of Hypothermia for Perinatal Asphyxia on Childhood Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Pappas, A.; McDonald, S.A.; Das, A.; Tyson, J.E.; Poindexter, B.B.; Schibler, K.; Bell, E.F.; Heyne, R.J.; et al. Effect of Depth and Duration of Cooling on Deaths in the NICU Among Neonates With Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. JAMA 2014, 312, 2629–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, G.; Mathur, A.; Zaniletti, I.; DiGeronimo, R.; Lee, K.-S.; Rao, R.; Dizon, M.; Hamrick, S.; Rudine, A.; Cook, N.; et al. Withdrawal of Life-Support in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. 2019, 91, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, F.T.; Kenis, A.; Parravicini, E. Perinatal palliative care: focus on comfort. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1258285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombrecht, L.; Chambaere, K.; Beernaert, K.; Roets, E.; Keyser, M.D.V.D.; De Smet, G.; Roelens, K.; Cools, F. Components of Perinatal Palliative Care: An Integrative Review. Children 2023, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pion, A.B.; Baenziger, J.; Fauchère, J.-C.; Gubler, D.; Hendriks, M.J. National Divergences in Perinatal Palliative Care Guidelines and Training in Tertiary NICUs. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 673545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnat, H.B.; Sarnat, M.S. Neonatal Encephalopathy Following Fetal Distress. Arch. Neurol. 1976, 33, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotschi, B.; Grass, B.; Ramos, G.; Beck, I.; Held, U.; Hagmann, C.; Meyer, P.; Zeilinger, G.; Schulzke, S.; Wellmann, S.; et al. The impact of a register on the management of neonatal cooling in Switzerland. Early Hum. Dev. 2015, 91, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, B.; Brotschi, B.; Hagmann, C.; Birkenmaier, A.; Schwendener, K.; Adams, M.; Kleber, M.; Register, S.N.A.A.C. Centre-specific differences in short-term outcomes in neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2021, 151, w20489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.; Puterman, A.; Linley, L.; Hann, F.; van der Elst, C.; Molteno, C.; Malan, A. The value of a scoring system for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Paediatr. 1997, 86, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, B.; Sabzehei, M.; Sabahi, M. Predictive factors of death in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy receiving selective head cooling. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 64, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deveci̇, M.F.; Turgut, H.; Alagöz, M.; Kaya, H.; Gökçe, I.K.; Özdemi̇r, R. Mortality Related Factors on Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathic Patients Treated with Therapeutic Hypothermia: A 11-year Single Center Experience. Turk. J. Med Sci. 2022, 52, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labat, J.; Brocard, C.; Belaroussi, Y.; Bar, C.; Gotchac, J.; Chateil, J.; Brissaud, O. Hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy: Retrospective descriptive study of features associated with poor outcome. Arch. De Pediatr. 2022, 30, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- \Glass, H.C.; Numis, A.L.; Comstock, B.A.; Gonzalez, F.F.; Mietzsch, U.; Bonifacio, S.L.; Massey, S.; Thomas, C.; Natarajan, N.; Mayock, D.E.; et al. Association of EEG Background and Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Neonates With Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy Receiving Hypothermia. Neurology 2023, 101, E2223–E2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeke, L.C.; Groenendaal, F.; Mudigonda, K.; Blennow, M.; Lequin, M.H.; Meiners, L.C.; van Haastert, I.C.; Benders, M.J.; Hallberg, B.; de Vries, L.S. A Novel Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score Predicts Neurodevelopmental Outcome After Perinatal Asphyxia and Therapeutic Hypothermia. J. Pediatr. 2018, 192, 33–40.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machie, M.; de Vries, L.S.; Inder, T. Advances in Neuroimaging Biomarkers and Scoring. Clin. Perinatol. 2024, 51, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayley, N. Manual for the Bayley scales of infant and toddler development, 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment,2006.

- Griffith, R. The abilities of young children. High Wycombe, UK: The TestAgency Ltd, 1984.

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerger, W.; Mozun, R.; Frey, B.; Liamlahi, R.; Grass, B.; Brotschi, B. Blood Lactate Levels during Therapeutic Hypothermia and Neurodevelopmental Outcome or Death at 18–24 Months of Age in Neonates with Moderate and Severe Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Neonatology 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larg, R.H.; Graf, S.; Kundu, S.; Hunziker, U.; Molinari, L. Predicting Developmental Outcome At School Age From Infant Tests of Normal, At-Risk and Retarded Infants. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1990, 32, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecht, M.; Wilkinson, D.J.C. The outcome of treatment limitation discussions in newborns with brain injury. Arch. Dis. Child. - Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014, 100, F155–F160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parravicini, E. Neonatal palliative care. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2017, 29, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Guide to Children’s Palliative Care. 4th edition. Bristol: Together for Short Lives (TfSL). Last accessed th, 2024: https://www.togetherforshortlives.org. 27 November.

- Bergstraesser, E.; Hain, R.D.; Pereira, J.L. The development of an instrument that can identify children with palliative care needs: the Paediatric Palliative Screening Scale (PaPaS Scale): a qualitative study approach. BMC Palliat. Care 2013, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergstraesser, E.; Paul, M.; Rufibach, K.; Hain, R.D.; Held, L. The Paediatric Palliative Screening Scale: Further validity testing. Palliat. Med. 2013, 28, 530–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Association of Perinatal Medicine. Recognising uncertainty: an integrated framework for palliative care in perinatal medicine. A BAPM Framework for Practice, July 2024. Last accessed November 16th, 2024: https://www.bapm.org/resources/palliative-care-in-perinatal-medicine-framework.

- Zimmermann, K.; on behalf of the PELICAN Consortium; Cignacco, E.; Engberg, S.; Ramelet, A.-S.; von der Weid, N.; Eskola, K.; Bergstraesser, E.; Ansari, M.; Aebi, C.; et al. Patterns of paediatric end-of-life care: a chart review across different care settings in Switzerland. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 67. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, J.; Hain, R. Redirecting Care: Compassionate Management of the Sick or Preterm Neonate at the End of Life. Children 2022, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, K.; Kalish, B.T.; Tam, E.W.; El Shahed, A.; Chau, V.; Wilson, D.; Tung, S.; Kazazian, V.; Miran, A.A.; Hahn, C.; et al. Prognostic Indicators of Reorientation of Care in Perinatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy Spectrum. J. Pediatr. 2024, 276, 114273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, P.; Chakkarapani, E. Fifteen-minute consultation: Therapeutic hypothermia for infants with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy-translating jargon, prognosis and uncertainty for parents. Arch. Dis. Child. - Educ. Pr. Ed. 2020, 105, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, B.M.; Erlach, M.; Rathke, V.; Cippa, G.; Hagmann, C.; Brotschi, B. Parents' Experiences on Therapeutic Hypothermia for Neonates With Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE): A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Qual. Manag. Heal. Care 2023, 33, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, L.K.; Gibson-Smith, D.; Jarvis, S.; Norman, P.; Parslow, R.C. Estimating the current and future prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Palliat. Med. 2020, 35, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Death (n=23) | Survivor (n=114) | |

| n(%) or median (IQR) | n(%) or median (IQR) | p value | |

| Sex, male | 14 (60.9) | 58 (50.9) | 0.5179 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 40.0 (39.0, 40.6) | 39.8 (38.4, 40.7) | 0.5038 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3450 (3050, 3658) | 3380 (3000, 3724) | 0.5542 |

| Outborn | 23 (100.0) | 105 (92.1) | 0.3561 |

| Small for gestation (< 10. percentile) | 2 (8.7) | 14 (12.3) | 1.0000 |

| Multiple gestation | 1 (4.3) | 4 (3.5) | 1.0000 |

| Maternal age (years) | 34 (31, 38) | 33 (30, 35) | 0.2930 |

| Primiparae | 15 (71.4) | 68 (62.4) | 0.5879 |

| SES Score | 4 (2, 10) | 4 (3, 6) | 0.8834 |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Vaginal delivery (all) | 12 (52.2) | 61 (53.5) | 1.0000 |

| spontaneous, cephalic | 7 (30.4) | 36 (31.6) | |

| spontaneous, breech | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | |

| instrumental | 5 (21.7) | 23 (20.2) | |

| Caesarean delivery (all) | 11 (47.8) | 53 (46.5) | 1.0000 |

| elective CS | 1 (4.3) | 5 (4.4) | |

| emergency CS | 8 (34.8) | 41 (36.0) | |

| secondary CS | 2 (8.7) | 7 (6.1) |

| Characteristics | Death (n=23) | Survivor (n=114) | |

| (according to Swiss National Cooling Protocol) | n(%) or Median (IQR) | n(%) or Median (IQR) | p value |

| Apgar score | |||

| at 1 minute | 0 (0, 1) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.0003 |

| at 5 minutes | 1 (1, 4) | 4 (2, 5) | 0.0032 |

| at 10 minutes | 2 (1, 4) | 5 (3, 6) | 0.0056 |

| Resuscitation in the delivery room* | 18 (78.3) | 65 (57.0) | 0.0650 |

| Umbilical artery pH | 6.87 (6.79, 7.04) | 6.99 (6.88, 7.10) | 0.0934 |

| Blood gas analysis, worst# | |||

| pH | 6.78 (6.61, 6.80) | 6.86 (6.79, 6.95) | <0.0001 |

| Base deficit (mmol/L) | 24.4 (19.1, 28.5) | 19.0 (14.8, 22.0) | 0.0029 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 17.7 (15.0, 19.0) | 14.1 (11.5, 16.0) | 0.0003 |

| Table 3. a. Comparison of prognostic factors between deaths and survivors. | |||

| Neurologic variables | Death (n=23) | Survivor (n=114) | |

| n(%) or median (IQR) | n(%) or median (IQR) | pvalue | |

| Sarnat Score | |||

| on admission (prior to TH) | 0.0177 | ||

| stage 1 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.5) | |

| stage 2 | 9 (39.1) | 73 (65.8) | |

| stage 3 | 14 (60.9) | 33 (29.7) | |

| day 1 | <0.0001 | ||

| stage 1 | 1 (5.0) | 29 (26.9) | |

| stage 2 | 6 (30.0) | 62 (57.4) | |

| stage 3 | 13 (65.0) | 17 (15.7) | |

| day 2* | <0.0001 | ||

| stage 1 | 1 (4.8) | 33 (31.7) | |

| stage 2 | 4 (19.0) | 61 (58.7) | |

| stage 3 | 9 (42.9) | 10 (9.6) | |

| day 3* | <0.0001 | ||

| stage 1 | 1 (7.1) | 38 (38.8) | |

| stage 2 | 2 (14.3) | 53 (54.1) | |

| stage 3 | 7 (50.0) | 7 (7.1) | |

| day 4* | 0.0034 | ||

| stage 1 | 1 (9.1) | 45 (50.0) | |

| stage 2 | 4 (36.4) | 39 (43.3) | |

| stage 3 | 4 (36.4) | 6 (6.7) | |

| Seizure | |||

| day 1 | 11 (47.8) | 19 (16.7) | 0.0022 |

| day 2* | 7 (33.3) | 14 (12.3) | 0.0227 |

| day 3* | 6 (42.9) | 7 (6.1) | 0.0006 |

| day 4* | 3 (27.3) | 7 (6.1) | 0.0436 |

| total | 14 (60.9) | 28 (24.6) | 0.0014 |

| MRI done at discharge | 7 (30.4) | 111 (97.4) | <0.0001 |

| Highest lactate (mmol/L) | |||

| day 1 | 11.0 (10.5, 15.2) | 6.8 (4.3, 12.0) | 0.0233 |

| day 2* | 7.3 (5.5, 7.8) | 3.4 (2.2, 4.7) | 0.0063 |

| day 3* | 4.3 (3.7, 4.6) | 2.0 (1.5, 3.4) | 0.0245 |

| day 4* | 3.0 (2.6, 4.4) | 1.5 (1.2, 2.1) | 0.0297 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).