Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Physical Activity Metrics

1.2. Behavioral Symptoms of PD and Dementia

1.3. Human Activity and Behavioral Recognition in People with PD or Dementia

1.4. Research Questions

- What are the current methods, sensing technologies, and AI techniques being used for activity and behavioral symptom recognition in older people with PD or dementia?

- Are statistical analyses and study protocols within the studies heterogeneous and/or reproducible?

- What gaps and possibilities exist in bringing research related to the use of sensing technologies for management and monitoring of human activity and behavioral symptoms into real-world settings and clinical practice for older adults with PD or dementia?

2. METHODS

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Risk of Bias (Quality) Assessment

2.4. Data Synthesis

- Type of journal (technical vs. medical), authors, country, year, number & demographics of participants, study setting (real world vs. laboratory)

- Relevancy to HAR used for digital phenotyping and/or classification of behavioral symptoms

- Sensors, devices, AI, datasets, gold standard outcome measures, biomarkers, validation

- Reproducibility (i.e.: transparency and clarity of algorithms and technical details, inclusion of important demographic details such as age and diagnosis)

- Inclusion of ethical considerations, data protection

- Future recommendations from studies

- Studies conducted for an advanced stage of disease or end-of-life

- Consent procedure (informed vs. presumed)

3. RESULTS

3.1. Included Systematic Review Characteristics

3.2. Sensing Technology, Devices, and Current Use in Research

3.3. Traditional Outcome Measures

3.4. Study Protocols and Methods

3.5. AI and Algorithms

3.6. Datasets

3.7. Quality & Bias Assessment

3.8. Recommendations from Included Systematic Reviews

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Underrepresentation and Ethical Considerations

4.2. Future Directions

5. LIMITATIONS & STRENGTHS

6. CONCLUSIONS

7. DECLARATIONS

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

ABBREVIATIONS

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BPSD | Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia |

| GPS | Global Positioning Systems |

| HAR | Human activity recognition |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| JBI | Johanna Briggs Institute |

| MCI | mild cognitive impairment |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

APPENDIX 1. Search strategies.

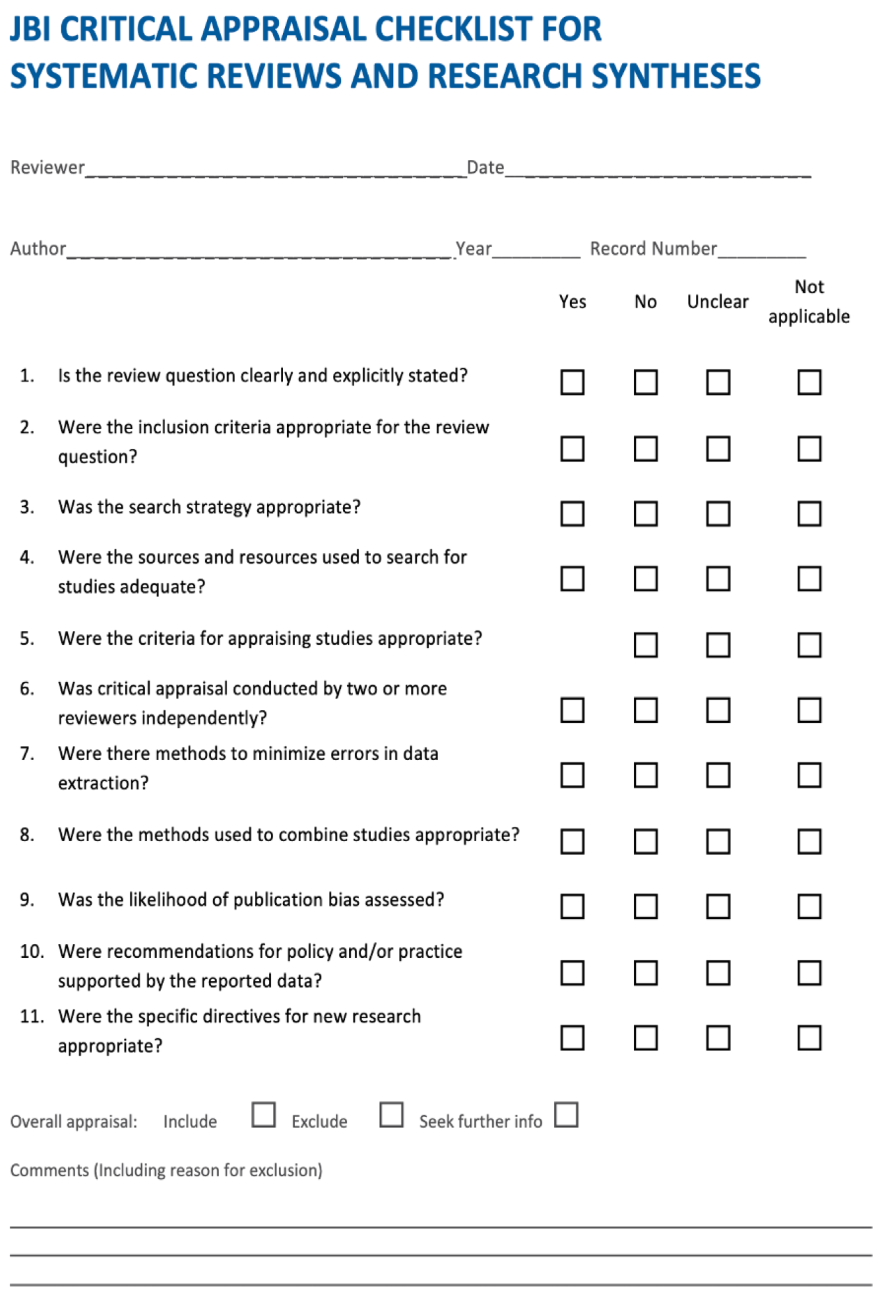

Appendix 2. Johanna Briggs Institute (JBI) bias and quality assessment.

Appendix 3.JBI quality assessment for systematic reviews.

| Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Total | Overall appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt Muphy et al. 2018 | y | y | y | y | y | y | u | y | y | y | y | 10 | include |

| Ardelean et al. 2023 | y | y | y | y | y | u | u | y | y | y | y | 9 | include |

| Ardle et al. 2023 | y | y | y | y | y | y | u | y | y | y | y | 10 | include |

| Breasail et al. 2021 | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | 11 | include |

| Khan et al. 2018 | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | 11 | include |

| Morgan et al. 2020 | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | 11 | include |

| Mughal et al. 2022 | y | y | y | y | y | u | u | y | u | y | y | 8 | include |

| Sica et al. 2021 | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | 11 | include |

| Anderson et al. 2020 | y | u | y | u | y | u | u | u | y | y | y | 6 | exclude |

| Esquer-Rochin et al. 2023 | y | y | y | y | y | u | u | y | u | y | y | 8 | include |

Appendix 4.Datasets and applicability to HAR for persons with PD or dementia.

| Dataset | Description | Applicable to HAR for persons with PD or dementia |

|---|---|---|

| ADNI | MRI images of patients with Alzheimer's disease | No |

| OASIS | MRI images (ages 18-96 years) | No |

| CASAS | Low-level sensor data of older adults ADLs; consists of Kyoto, Aruba and Multi-resident datasets featuring 20 participants (undefined). Demographics of datasets are: an older woman, her children and grandchildren; 2 participants | Yes |

| PUCK | Sensory data from environmental sensors and wearables about activities of daily living in older adults | Unclear |

| PAMAP2 | Acceleration, orientation, angular rates related to ADLs | Unclear |

| ARAS and ADL | ADLs collected from binary sensors | Unclear |

| PD Telemonitoring | Voice samples of people with PD | No |

| AZTIAHO | Voice samples of people with Alzheimer's disease | No |

| Tsanas et al.'s data set | Data related to dexterity and speech | Unclear |

| Parkinsons data set | Voice samples of people with PD | No |

| mPower Project | Vowel recordings of participants | No |

| Daphnet | Freezing of gait in persons with PD | Yes |

| Freiburg Groceries | Images of groceries | No |

| Labled faces in the wild | Facial images of people | No |

| UK DALE and Sztyler | Recordings of domestic appliance-level electricity/whole-house demand | No |

Appendix 5.Future Work Recommendations from Systematic Review

APPENDIX 6-7. See attached excel file

| Included systematic reviews | Future work recommendations |

|---|---|

| Johansson et al. 2018, Ardle et al. 2023, Khan et al. 2018, Ardelean et al. 2023 |

Furthering investigation of clinometric properties of the measurements derived from wearables to improve standardization of data protocols |

| Johansson et al. 2018, Mughal et al. 2020, Breasail et al. 2023 |

Development of patient-specific algorithms for precision medicine focused digital solutions |

| Ardelean et al. 2023 | Gender comparisons |

| Ardle et al. 2023, Breasail et al. 2023, Ardelean et al. 2023 |

More longitudinal research to see changes over time |

| Ardle et al. 2023, Johansson et al. 2018 | Stronger association between measures derived from HAR and clinically meaningful outcomes. |

| Ardle et al. 2023 | Improvement of devices used to collect data |

| Ardle et al. 2023, Johansson et al. 2018, Breasail et al. 2023, Khan et al. 2018 |

Effectiveness and ecological validity of wearables |

| Ardle et al. 2023, Sica et al. 2021, Ardelean et al. 2023, Breasail et al. 2023 | Development of sensing technology which is best adapted to the patient (size, cost, flexibility of software and features for users and researchers, etc.) |

| Khan et al. 2018 | Addressing ethical issues |

| Khan et al. 2018; Breasail et al. 2023 | Development of best practices for storing and accessing big data; proper data mining techniques followed by advanced machine-learning methods |

| Morgan et al. 2020, Mughal et al. 2020 | Measurement of free-living ADLs at home is relatively unexplored |

| Mughal et al. 2020 | More studies specific to behavioral symptoms of PD |

| Sica et al. 2021, Breasail et al. 2023 | Ad hoc hardware and software capable of providing real-time feedback to clinicians and patients. |

| Sica et al. 2021 | The involvement of formal and informal caregivers trained in the data collection |

| Sica et al. 2021, Mughal et al. 2020, Ardle et al. 2023 |

Sample size and choice should be justified and reported |

| Esquer-Rochin et al. 2023 | More data collection and exploring other machine learning algorithms and models |

| Esquer-Rochin et al. 2023 | Experiments in real-world settings, further validation efforts, increased sample sizes for ad hoc data |

| Esquer-Rochin et al. 2023 | Assistive IoT systems for patients suffering from late-stage dementia and adapted to progression of the disease, including end of life. |

References

- World Health Organization: WHO. (2020, February 5). Ageing. https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1.

- World Health Organization: WHO & World Health Organization: WHO. (2023, March 15). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- Emre, M. Dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2003 Apr 1;2(4):229-37.

- Stavropoulos TG, Papastergiou A, Mpaltadoros L, Nikolopoulos S, Kompatsiaris I. IoT wearable sensors and devices in elderly care: A literature review. Sensors (Basel). 2020;20(10):2826.

- St Fleur RG, St George SM, Leite R, Kobayashi M, Agosto Y, Jake-Schoffman DE. Use of Fitbit devices in physical activity intervention studies across the life course: narrative review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2021 May 28;9(5):e23411.

- Feehan LM, Geldman J, Sayre EC, Park C, Ezzat AM, Yoo JY, Hamilton CB, Li LC. Accuracy of Fitbit devices: systematic review and narrative syntheses of quantitative data. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2018 Aug 9;6(8):e10527.

- Fukushima N, Kikuchi H, Sato H, Sasai H, Kiyohara K, Sawada SS, Machida M, Amagasa S, Inoue S. Dose-response relationship of physical activity with all-cause mortality among older adults: an umbrella review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2024 Mar 1;25(3):417-30.

- Leite Silva ABR, Goncalves de Oliveira RW, Diogenes GP, de Castro Aguiar MF, Sallem CC, Lima MPP, et al. Premotor, nonmotor and motor symptoms of Parkinson's Disease: A new clinical state of the art. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;84:101834.

- Viseux FJF, Delval A, Simoneau M, Defebvre L. Pain and Parkinson's disease: Current mechanism and management updates. Eur J Pain. 2023;27(5):553-67.

- Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol. 2012;3:73.

- Au-Yeung WM, Miller L, Beattie Z, May R, Cray HV, Kabelac Z, et al. Monitoring Behaviors of Patients With Late-Stage Dementia Using Passive Environmental Sensing Approaches: A Case Series. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;30(1):1-11.

- Avila FR, McLeod CJ, Huayllani MT, Boczar D, Giardi D, Bruce CJ, et al. Wearable electronic devices for chronic pain intensity assessment: A systematic review. Pain Pract. 2021;21(8):955-65.

- Cho E, Kim S, Heo S-J, Shin J, Hwang S, Kwon E, et al. Machine learning-based predictive models for the occurrence of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: model development and validation. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1).

- Khan SS, Spasojevic S, Nogas J, Ye B, Mihailidis A, Iaboni A, et al., editors. Agitation detection in people living with dementia using multimodal sensors. 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2019: IEEE.

- Kumar P, Chauhan S, Awasthi LK. Human activity recognition (har) using deep learning: Review, methodologies, progress and future research directions. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering. 2024 Jan;31(1):179-219.

- Huhn S, Axt M, Gunga H-C, Maggioni MA, Munga S, Obor D, et al. The impact of wearable technologies in health research: scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10(1):e34384.

- Zhang H, Song C, Rathore AS, Huang MC, Zhang Y, Xu W. mHealth Technologies Towards Parkinson's Disease Detection and Monitoring in Daily Life: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 2021;14:71-81.

- Straczkiewicz M, James P, Onnela J-P. A systematic review of smartphone-based human activity recognition methods for health research. npj digit. 2021;4(1):148.

- Gupta N, Gupta SK, Pathak RK, Jain V, Rashidi P, Suri JS. Human activity recognition in artificial intelligence framework: a narrative review. Artif Intell Rev. 2022;55(6):4755-808.

- Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews | Cochrane Training. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-v (Accessed: 06 May 2024).

- Demrozi F, Pravadelli G, Bihorac A, Rashidi P. Human activity recognition using inertial, physiological and environmental sensors: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access. 2020;8:210816-36.

- Islam MM, Nooruddin S, Karray F, Muhammad G. Human activity recognition using tools of convolutional neural networks: A state of the art review, data sets, challenges, and future prospects. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2022;149:106060.

- Lussier M, Lavoie M, Giroux S, Consel C, Guay M, Macoir J, et al. Early detection of mild cognitive impairment with in-home monitoring sensor technologies using functional measures: a systematic review. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics. 2018;23(2):838-47.

- Rani GJ, Hashmi MF, Gupta A. Surface electromyography and artificial intelligence for human activity recognition-A systematic review on methods, emerging trends applications, challenges, and future implementation. IEEE Access. 2023.

- Saleem G, Bajwa UI, Raza RH. Toward human activity recognition: a survey. Neural 26. Computing and Applications. 2023;35(5):4145-82.

- Cumpston MS, McKenzie JE, Welch VA, Brennan SE. Strengthening systematic reviews in public health: guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Journal of Public Health. 2022;44(4):e588-e92.

- Choi GJ, Kang H. Introduction to Umbrella Reviews as a Useful Evidence-Based Practice. J Lipid Atheroscler. 2023;12(1):3-11.

- Harrison H, Griffin SJ, Kuhn I, Usher-Smith JA. Software tools to support title and abstract screening for systematic reviews in healthcare: an evaluation. BMC medical research methodology. 2020;20:1-12.

- Valizadeh A, Moassefi M, Nakhostin-Ansari A, Hosseini Asl SH, Saghab Torbati M, Aghajani R, et al. Abstract screening using the automated tool Rayyan: results of effectiveness in three diagnostic test accuracy systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2022;22(1):160.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372.

- Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. bmj. 2020;368.

- Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132-40.

- Faulkner, G., Fagan, M. J., & Lee, J. (2021). Umbrella reviews (systematic review of reviews). International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(1), 73–90. [CrossRef]

- Morgan C, Rolinski M, McNaney R, Jones B, Rochester L, Maetzler W, et al. Systematic Review Looking at the Use of Technology to Measure Free-Living Symptom and Activity Outcomes in Parkinson's Disease in the Home or a Home-like Environment. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(2):429-54.

- Esquer-Rochin M, Rodríguez L-F, Gutierrez-Garcia JO. The Internet of Things in dementia: A systematic review. Internet of Things. 2023;22.

- Ardelean A, Redolat R. Supporting Behavioral and Psychological Challenges in Alzheimer Using Technology: A Systematic Review. Activities, Adaptation & Aging. 2023:1-32.

- Mc Ardle R, Jabbar KA, Del Din S, Thomas AJ, Robinson L, Kerse N, et al. Using Digital Technology to Quantify Habitual Physical Activity in Community Dwellers With Cognitive Impairment: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e44352.

- Breasail MO, Biswas B, Smith MD, Mazhar MKA, Tenison E, Cullen A, et al. Wearable GPS and Accelerometer Technologies for Monitoring Mobility and Physical Activity in Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Systematic Review. Sensors (Basel). 2021;21(24).

- Johansson D, Malmgren K, Alt Murphy M. Wearable sensors for clinical applications in epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and stroke: a mixed-methods systematic review. J Neurol. 2018;265(8):1740-52.

- Khan SS, Ye B, Taati B, Mihailidis A. Detecting agitation and aggression in people with dementia using sensors-A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(6):824-32.

- Mughal H, Javed AR, Rizwan M, Almadhor AS, Kryvinska N. Parkinson’s Disease Management via Wearable Sensors: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access. 2022;10:35219-37.

- Sica M, Tedesco S, Crowe C, Kenny L, Moore K, Timmons S, et al. Continuous home monitoring of Parkinson's disease using inertial sensors: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246528.

- Cesana BM, Poptsi E, Tsolaki M, Bergh S, Ciccone A, Cognat E, et al. A Confirmatory and an Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) in a European Case Series of Patients with Dementia: Results from the RECage Study. Brain Sci. 2023;13(7).

- Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roque IFM, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, Giannakou A, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(3):CD010783.

- Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson's D. The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2003;18(7):738-50.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-9.

- Cummings, J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Development and Applications. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2020;33(2):73-84.

- Bankole A, Anderson M, Smith-Jackson T, Knight A, Oh K, Brantley J, et al. Validation of noninvasive body sensor network technology in the detection of agitation in dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5):346-54.

- Madrid-Navarro CJ, Puertas Cuesta FJ, Escamilla-Sevilla F, Campos M, Ruiz Abellan F, Rol MA, et al. Validation of a Device for the Ambulatory Monitoring of Sleep Patterns: A Pilot Study on Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol. 2019;10:356.

- Moyle W, Jones C, Murfield J, Thalib L, Beattie E, Shum D, et al. Effect of a robotic seal on the motor activity and sleep patterns of older people with dementia, as measured by wearable technology: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Maturitas. 2018;110:10-7.

- Cai G, Huang Y, Luo S, Lin Z, Dai H, Ye Q. Continuous quantitative monitoring of physical activity in Parkinson's disease patients by using wearable devices: a case-control study. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(9):1657-63.

- Bernad-Elazari H, Herman T, Mirelman A, Gazit E, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Objective characterization of daily living transitions in patients with Parkinson's disease using a single body-fixed sensor. J Neurol. 2016;263(8):1544-51.

- Bromundt V, Wirz-Justice A, Boutellier M, Winter S, Haberstroh M, Terman M, et al. Effects of a dawn-dusk simulation on circadian rest-activity cycles, sleep, mood and well-being in dementia patients. Exp Gerontol. 2019;124:110641.

- Fleiner T, Haussermann P, Mellone S, Zijlstra W. Sensor-based assessment of mobility-related behavior in dementia: feasibility and relevance in a hospital context. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(10):1687-94.

- Madrid-Navarro CJ, Escamilla-Sevilla F, Minguez-Castellanos A, Campos M, Ruiz-Abellan F, Madrid JA, et al. Multidimensional Circadian Monitoring by Wearable Biosensors in Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol. 2018;9:157.

- Mantri S, Wood S, Duda JE, Morley JF. Comparing self-reported and objective monitoring of physical activity in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;67:56-9.

- Mirelman A, Hillel I, Rochester L, Del Din S, Bloem BR, Avanzino L, et al. Tossing and turning in bed: nocturnal movements in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2020;35(6):959-68.

- Uchino K, Shiraishi M, Tanaka K, Akamatsu M, Hasegawa Y. Impact of inability to turn in bed assessed by a wearable three-axis accelerometer on patients with Parkinson's disease. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187616.

- Valembois L, Oasi C, Pariel S, Jarzebowski W, Lafuente-Lafuente C, Belmin J. Wrist actigraphy: a simple way to record motor activity in elderly patients with dementia and apathy or aberrant motor behavior. The Journal of nutrition, health and aging. 2015;19(7):759-64.

- van Uem JMT, Cerff B, Kampmeyer M, Prinzen J, Zuidema M, Hobert MA, et al. The association between objectively measured physical activity, depression, cognition, and health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018;48:74-81.

- David R, Mulin E, Friedman L, Le Duff F, Cygankiewicz E, Deschaux O, et al. Decreased daytime motor activity associated with apathy in Alzheimer disease: an actigraphic study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):806-14.

- Etcher L, Whall A, Kumar R, Devanand D, Yeragani V. Nonlinear indices of circadian changes in individuals with dementia and aggression. Psychiatry Res. 2012;199(1):77-8.

- Figueiro MG, Plitnick BA, Lok A, Jones GE, Higgins P, Hornick TR, et al. Tailored lighting intervention improves measures of sleep, depression, and agitation in persons with Alzheimer's disease and related dementia living in long-term care facilities. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1527-37.

- Higami Y, Yamakawa M, Shigenobu K, Kamide K, Makimoto K. High frequency of getting out of bed in patients with Alzheimer's disease monitored by non-wearable actigraphy. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(2):130-4.

- Maglione JE, Liu L, Neikrug AB, Poon T, Natarajan L, Calderon J, et al. Actigraphy for the assessment of sleep measures in Parkinson's disease. Sleep. 2013;36(8):1209-17.

- Nagels G, Engelborghs S, Vloeberghs E, Van Dam D, Pickut BA, De Deyn PP. Actigraphic measurement of agitated behaviour in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(4):388-93.

- Sringean J, Anan C, Thanawattano C, Bhidayasiri R. Time for a strategy in night-time dopaminergic therapy? An objective sensor-based analysis of nocturnal hypokinesia and sleeping positions in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci. 2017;373:244-8.

- Sringean J, Taechalertpaisarn P, Thanawattano C, Bhidayasiri R. How well do Parkinson's disease patients turn in bed? Quantitative analysis of nocturnal hypokinesia using multisite wearable inertial sensors. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;23:10-6.

- Xue F, Wang FY, Mao CJ, Guo SP, Chen J, Li J, et al. Analysis of nocturnal hypokinesia and sleep quality in Parkinson's disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;54:96-101.

- Nakae H, Tsushima H. Analysis of 24-h physical activities of patients with parkinson's disease at home. Journal of physical therapy science. 2011;23(3):509-13.

- Alvarez F, Popa M, Solachidis V, Hernandez-Penaloza G, Belmonte-Hernandez A, Asteriadis S, et al. Behavior analysis through multimodal sensing for care of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s patients. Ieee Multimedia. 2018;25(1):14-25.

- Enshaeifar S, Zoha A, Markides A, Skillman S, Acton ST, Elsaleh T, et al. Health management and pattern analysis of daily living activities of people with dementia using in-home sensors and machine learning techniques. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0195605.

- Minamisawa A, Okada S, Inoue K, Noguchi M. Dementia Scale Score Classification Based on Daily Activities Using Multiple Sensors. IEEE Access. 2022;10:38931-43.

- Rostill H, Nilforooshan R, Morgan A, Barnaghi P, Ream E, Chrysanthaki T. Technology integrated health management for dementia. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2018;23(10):502-8.

- Shahid ZK, Saguna S, Ahlund C. Recognizing Long-term Sleep Behaviour Change using Clustering for Elderly in Smart Homes. 2022 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2)2022. p. 1-7.

- Husebo BS, Heintz HL, Berge LI, Owoyemi P, Rahman AT, Vahia IV. Sensing Technology to Monitor Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms and to Assess Treatment Response in People With Dementia. A Systematic Review (vol 10, 1699, 2020). Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1.

- Ford C, Xie CX, Low A, Rajakariar K, Koshy AN, Sajeev JK, et al. Comparison of 2 smart watch algorithms for detection of atrial fibrillation and the benefit of clinician interpretation: SMART WARS study. Clinical Electrophysiology. 2022;8(6):782-91.

- Perez MV, Mahaffey KW, Hedlin H, Rumsfeld JS, Garcia A, Ferris T, et al. Large-scale assessment of a smartwatch to identify atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(20):1909-17.

- Dementia in Europe yearbook 2019. Available at: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/alzheimer_europe_dementia_in_europe_yearbook_2019.pdf (Accessed: 06 May 2024).

- Rubeis, G. The disruptive power of Artificial Intelligence. Ethical aspects of gerontechnology in elderly care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;91:104186.

- Alfalahi H, Dias SB, Khandoker AH, Chaudhuri KR, Hadjileontiadis LJ. A scoping review of neurodegenerative manifestations in explainable digital phenotyping. npj Parkinson's Disease. 2023;9.

- Morgan C, Tonkin EL, Masullo A, Jovan F, Sikdar A, Khaire P, et al. A multimodal dataset of real world mobility activities in Parkinson's disease. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):918.

- De-La-Hoz-Franco E, Ariza-Colpas P, Quero JM, Espinilla M. Sensor-Based Datasets for Human Activity Recognition - A Systematic Review of Literature. IEEE Access. 2018;6:59192-210.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(4):W-65-W-9.

| Population/persons | Older adults with dementia or PD |

| Intervention | Human activity and behavior recognition using sensing technology, including wearables and behavioral symptoms and/or functional activities of daily living. |

| Comparison | Current gold standard outcome measures used within current literature (i.e. Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), Personal Activities of Daily Living (PADL), Polysomnography (PSG), Electrocardiography (EKG), etc.) |

| Outcome | Identification of biomarkers, movement and activity classification models, behavior identification and classification models, measurement methods for activities of daily living, knowledge of basic algorithms and AI used, and information on public datasets specific to human activity recognition (HAR) in older adults with dementia or PD. |

| INCLUSION CRITERIA | EXCLUSION CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| Systematic Reviews from medical and technical journals | Not a systematic review |

| Including people with PD or dementia, 65 years or older | People without PD or dementia and younger than 65. |

| Sensing technology used for HAR (including behavioral symptoms); sensors, wearables, radar-technology, GPS, multi-modal sensing systems. | Not specific to management or observation of activities or behaviors, gait specific, motor functions for PD specific, fall specific, apps, diagnosis of disease (early detection), non-sensor related technology. |

| Literature from the last 5 years (2018-2024) | Published before 2018 |

| English language | Not written in English |

| Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics | Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers |

**Included Comparative Measures |

Results and conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardelean and R. Redolat (2023)[36], Spain | To determine how technology can help to improve the support for behavioral and psychological challenges of dementia. Mean age 60-95 years # of participants: 9-455 # of included studies: 18 Behavioral symptoms: Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in persons with Alzheimer’s disease |

wearable triaxial accelerometer, daysimeter (rest-activity, sleep), GPS, non-wearable actigraphy device (under mattress - sleep), wrist actimetry, mobile phone, robots 3 days, 3-4 weeks, 3 months, 1-5 years (most common 3 months) |

Not included | Psychological symptoms: depression, anxiety, apathy. Behavioral symptoms: sleep disturbances, agitation, wandering. |

MMSE, NPI, NPI-NH, CDR, IQCODE, VAS, ADL, CADS, CMAI, QUALID, FAB, DEMQOL, EQ-5D-5L, QUIS, S-MMSE, MSPSS, HDRS, FCSRT, FAST, TMT-A/B, STROOP Test, DSST, AI, NOSGER, QOL-AD, TBA, CGA, CDT, ET, STAI, HADS, NQOL, MDS, RUDAS, AS, CAM, GDS, RAID, CSDD, ACE-R, TELPI, AIFAI, WHOQOL-OLD, BARS, APADEM-NH, PSQI, AES,MDS-ADL, DAD, CERAD-NB, WMS-III, CFT, DSMT, DSST, video |

|

| Breasail et al. (2021)*[38], United Kingdom | Description of outcome measures and identification of studies that show a relationship between neurodegenerative disease and digital biomarkers. Mean age 28.3-85.5 *participants <63 years were included as healthy controls # of participants: 5-455 # of included studies: 28 Activity and behavioral symptoms: Physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep disturbance, rest-activity patterns, motor symptoms of PD |

GPS, sensors, accelerometers 24 hrs-3 monthsmost common 7 days |

Not included | Step count, time spent in physical activity, number of bouts, MET, awake/sleep time, time spent sedentary, trip frequency, duration outside home, walking duration, aggregation of velocity data into 60s epochs, activity levels, algorithm classification of upright posture, sitting, standing, walking, walking speed cut-offs for PD, gait - motor PD, activity intensity and levels, sleep activity. |

ALSFRS-R, MoCA, PDQ, PASE, LSA |

|

|

Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics |

Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers | Included Comparative Measures | Results and conclusions |

| Esquer-Rochin (2023)*[35], Mexico | To investigate the state of the art of the IoT in dementia. Mean age not provided. # of participants: 10-42 # of included studies: 104 Activity and behavioral symptoms: ADLs, agitation, wandering |

RF devices, Beacons GPS, Inertial devices. Smartphones glasses and watches, binary proximity sensors, ambient temperature, smart meter, video, neuroimaging devices. Length of observations not included. |

Random forest, decision trees, support vector machines, k-nearest neighbors, and (deep) neural networks. | Activities of daily living, speech/voice, location/GPS, vital signs, brain/neurological related variables, position within a room, wandering or agitation related activities. | Not included |

|

|

Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics |

Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers | Included Comparative Measures | Results and conclusions |

| Johannson et al. (2018)[39], Sweden | Synthesis of knowledge from quantitative and qualitative clinical research using wearable sensors in epilepsy, PD (PD), and stroke. Mean age 34-71 years *1 sleep specific (non-motor) study included: mean age 67 +-9 years # of participants: 5-527 # of included studies: 56 Activity and behavioral symptoms: Physical activity metrics, walking, sleep disturbances, seizures |

accelerometry, gyroscope, wearables 1-9 days lab setting8h -7 days free-living |

Commercial algorithm (Parkinson's KinetiGraph), time-frequency mapping-Fast Fourier transformations, support vector machines, iterative forward selection algorithm, linear discriminant analysis, discriminant analysis to determine the threshold of mean duration of immobility, combined axis rotations, power spectrum area and peak power, root mean square, mean velocity, frequency, jerk. |

Step counts, energy expenditure during walking, tremor, dyskinesia, postural sway, spatiotemporal gait, medication evoked adverse symptoms, tonic-clonic seizures, non-epileptic seizures, motor seizures, sleep disturbance, upper extremity activity, walking. | Video, gait analysis, functional activities analysis, UPDRS III, CDRS, mAIMS, MBRS, GAITRite, PIGD, PDQ-39, MiniBEST, SF-36, commercial system (SAM, PAL, TriTrac RT3), commercial system (sensing stylus, Actical, ActivPAL, Vitaport and Kinesia), NIHSS, NEADL, FMA, ARAT, WMFT, stroke ULAM, MAL, MAL-26, AAUT, BBS, FIM, mRS, 6MWT |

|

|

Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics |

Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers | Included Comparative Measures | Results and conclusions |

| Khan et al. (2018)[40], Canada | Identification of studies that use different types of sensors to detect agitation and aggression in persons with dementia. Mean age 74.3-85.5 years *7/13 studies included no age information # of participants: 6-110 # of included studies: 14 Behavioral symptoms: Agitation and aggression |

accelerometry, gyroscope, wearables, camera, ambient sensing modalities Timeframe not detailed for all studies; 3 hrs, 48 hrs, 5-7 days |

Rotation forest, Hidden Markov Models, Support vector machines, Bayesian Network, Time frequency analysis | agitation and aggression | CMAI, MMSE, DSM-III-R, ABS, NPI, SOAPD |

|

|

Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics |

Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers | Included Comparative Measures | Results and conclusions |

| McArdle et al. (2023)[37], United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia |

To understand habitual physical activity participation in people with cognitive impairment identifying: metrics used to assess activity, describe differences between people with dementia and healthy controls, and make future recommendations for measuring and reporting activity impairments. Mean age 22-84 years *majority 63-84 years # of participants: 7-323 # of included studies: 33 Activity: Physical activity metrics |

wearables, ambient home-based sensors, accelerometer (most commonly wrist worn or low back) Most common was a 7-day protocol varying from 2 days-3 months (capturing weekdays and weekends) |

Not included | Steps per day, outdoor time, activity counts, low-vigorous activity (METS), total movement intensity (mean vector magnitude of dynamic acceleration per day for total behavior, expressed relative to gravitational acceleration, time spent walking, time of day activity (day, night, etc.), relative amplitude (higher amplitude indicates stronger rhythm; rest-activity), hour to hour and day to day variability, root mean square difference, interindividual variability, intra-daily stability and variability, COV of daily activity. |

MoCA |

|

|

Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics |

Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers | Included Comparative Measures | Results and conclusions |

| Morgan et al. (2020)[34], United Kingdom | Provide an overview of what technology is being used to test outcomes in PD in free-living participant's activity in a home environment. Mean age not provided. # of participants: N/I # of included studies: 65 Activity and behavioral symptoms: Physical activity and sleep disturbances |

Various sensing technologies 2 weeks or less (majority)10 studies- up to 1 yr3 studies- multiple measurements over time |

Not included | Tremor, gait, typing, medication on/off, sleep, physical activity, bradykinesia, dyskinesia, skin temperature, light exposure, posture, falls, activities of daily living (majority gait and motor related symptoms) | UPDRS, PDQ-8, PDSS, FIM, PSQI, NADCS |

|

|

Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics |

Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers | Included Comparative Measures | Results and conclusions |

| Mughal et al. (2022)*[41], Pakistan, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia | To present different techniques for early detection and management of PD motor and behavioral symptoms using wearable sensors. Mean age not provided. # of participants: 4-2063 # of included studies: 60 Behavioral symptoms: Sleep dysfunction, depression, impulse control, motor symptoms of PD |

Inertial sensors (IMU): triaxial accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. Micro-electro-mechanical system (MEMS), necklace, and barometer. Cameras: Zenith and Kinect. Capacitive pressure sensor. Surface EMG. IMUs; Mechanomyography. Flex and light sensors. Ambulatory Circadian Monitoring (ACM), polysomnography. Smart toilet. EEG sensors. Timeframe information not included. |

Not included | Motor symptoms: tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and freezing of gait. Behavioral and other symptoms: gastrointestinal problems, sleep disfunction, impulse control disorder, depression, physical activity metrics. |

UPDRS, HY, TUG, polysomnography, EEG |

|

|

Authors/Year Country |

Aim and Demographics |

Sensing Technology and Observation Time |

Algorithms and AI | Digital Biomarkers | Included Comparative Measures | Results and conclusions |

| Sica et al. (2021)[42], Ireland | To investigate continuous PD monitoring using inertial sensors, where the focus is papers with at least one free-living data capture unsupervised (either directly or via video- tapes). Mean age not provided. # of participants: 1-172 # of included studies: 24 Activity: ADL (transitional), physical activity, and motor symptoms of PD |

accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometers. Hours-14 days |

Artificial Neural Networks, Fuzzy logic algorithms, linear regression, and Support Vec- tor Machine, Diverse Density, Expectation Maximization version of Diverse Density, Discriminative variant of the axis-parallel hyper- rectangle, Multiple instances learning k-Nearest Neighbor and Multiple Instance Support Vector Machine. |

Gait impairments, step-counts, intensity and volume of activities, kinematics, bradykinesia, tremor, dyskinesia, and on/off state episodes. | UPDRS, PASE, symptom diaries |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).