Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

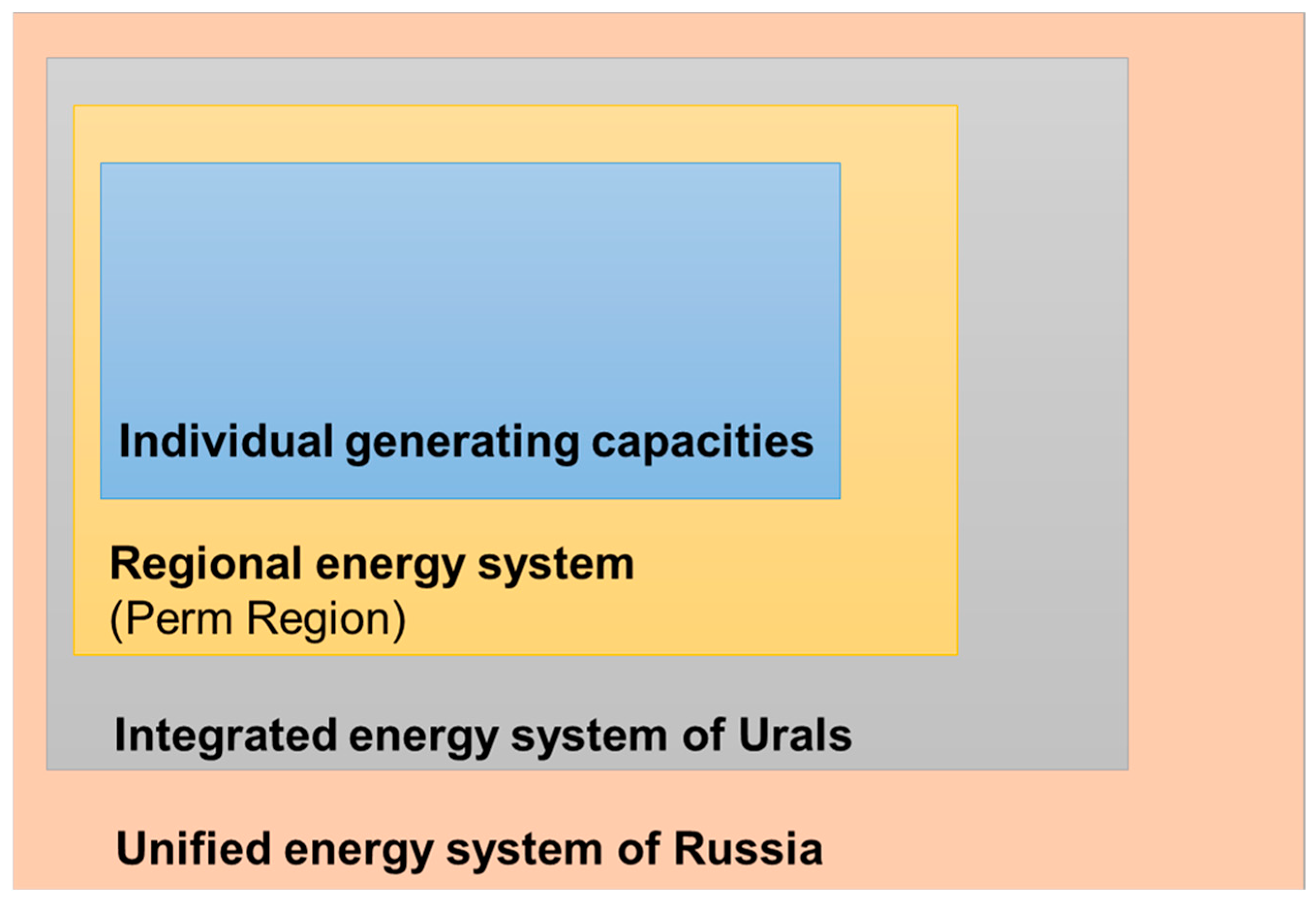

3.1. Structure and Features of the Energy System of the Russian Federation

3.2. Structure and Features of the Energy System of the UES of the Urals

3.3. Structure and Features of the Energy System of the Perm Region

3.3. Generating Capacities Owned by Companies

3.4. «Green» Certificates

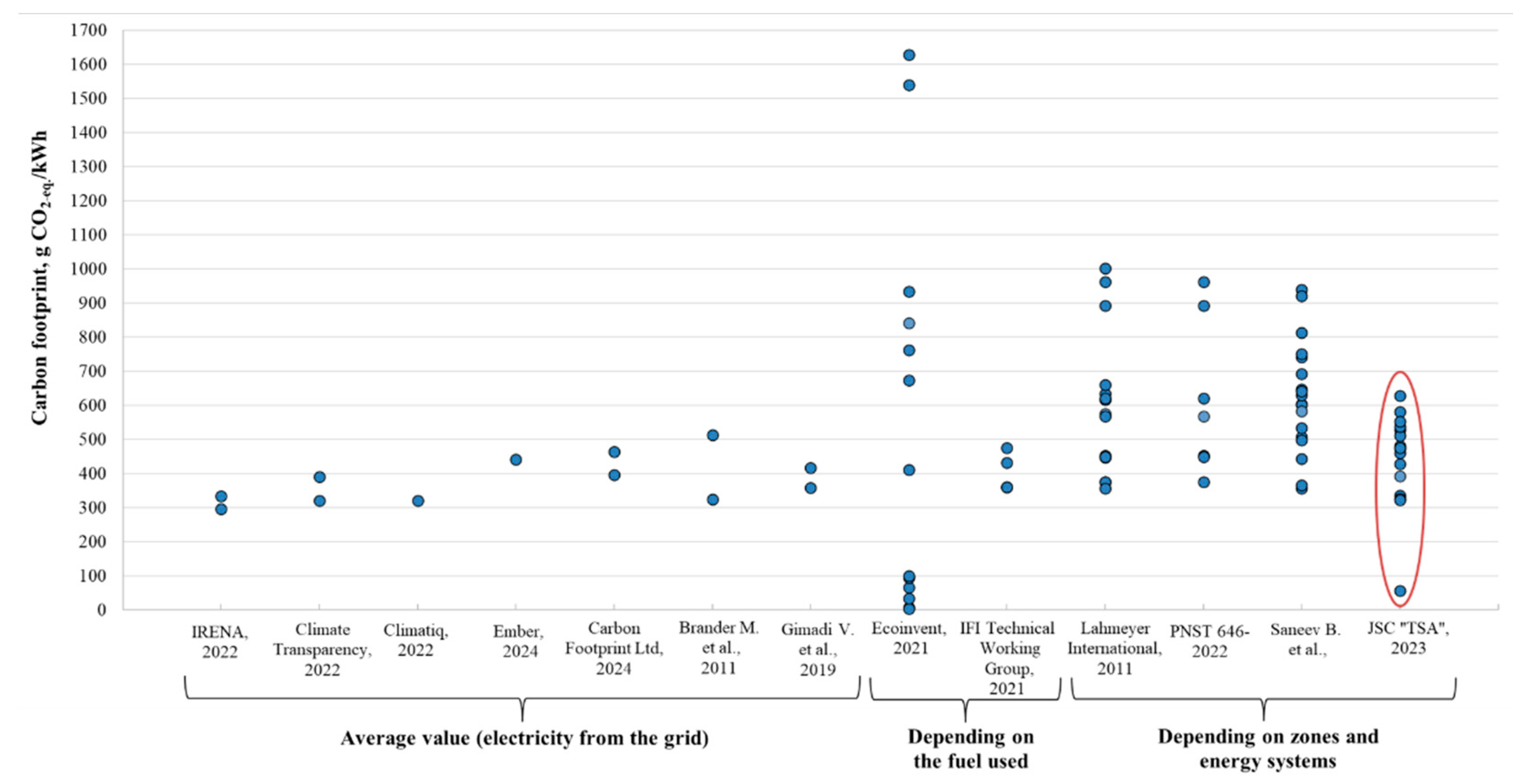

3.5. Existing Approaches to Assessing Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Electricity Production

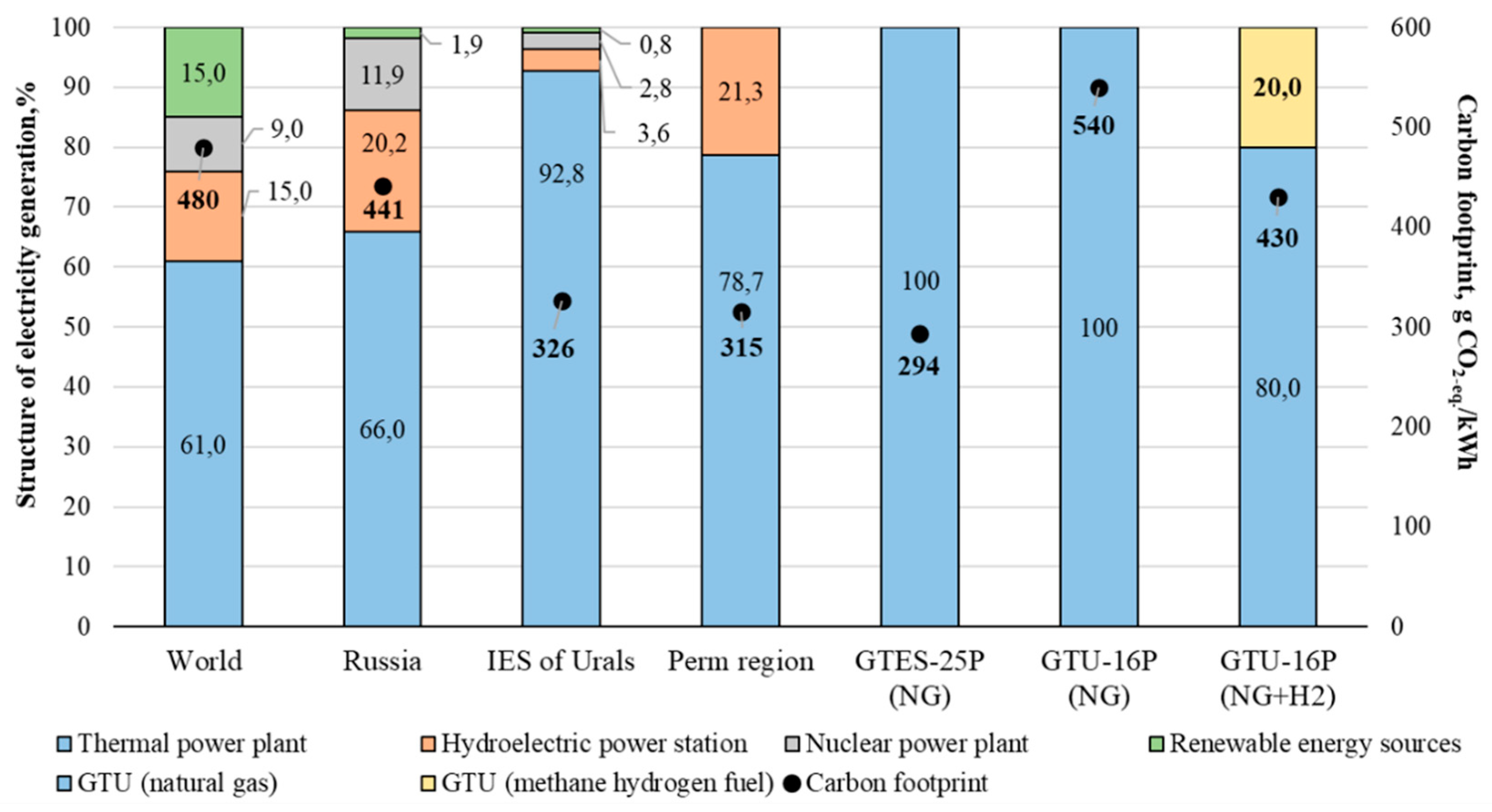

3.6. Carbon Footprint of Electricity Genereted in Russia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Order of the Government of the Russian Federation of October 29, 2021 No. 3052-r "On approval of the Strategy for the socio-economic development of the Russian Federation with low greenhouse gas emissions until 2050.". Available online: http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001202111010022 (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 04.11.2020 No. 666 "On the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions". Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/45990 (accessed on 04 October 2024).

- Tsvetkov, P.; Andreichyk, A.; Kosarev, O. The impact of economic development of primary and secondary industries on national CO2 emissions: The case of Russian regions. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 351, 119881. [Google Scholar]

- The Carbon Brief Profile: Russia. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-russia (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Russian Federation. National Communication (NC). NC 8. Biennial Reports (BR). BR 5. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/624780 (accessed on 02 September 2024).

- Schreider, A.; Eckert, P.; Bonneschky, A. Development of the Russian Electricity Carbon Emission Factors for the Period 2010-2020. Russia Power 2011, Moscow, 28th - 30th March 2011, 13 p. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319626357_Development_of_the_Russian_Electricity_Carbon_Emission_Factors_for_the_Period_2010-2020 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Saneev, B.; Ivanova, I.; Izhbuldin, A.; Maysyuk, E. Assessment of the spatial distribution of greenhouse gas emissions from energy facilities in Russia. Energy Policy 2022, 11, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Senchuk, D.; Korotchenko, V. Calculation of indirect energy greenhouse gas emissions: international standards, practice of calculating emission factors, current state in Russia. News in Electric Power Engineering 2023, 3(125), 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brander, M.; Sood, A.; Wylie, Ch.; Haughton, A.; Lovell, J. Technical Paper «Electricity-specific emission factors for grid electricity». Ecometrica 2011. Available online: https://ecometrica.com/assets/Electricity-specific-emission-factors-for-grid-electricity.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Global Electricity Review 2024. Ember; 2024; 191 p. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/05/Report-Global-Electricity-Review-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- RUSSIAN FEDERATION. CLIMATE TRANSPARENCY REPORT: COMPARING G20 CLIMATE ACTION; 2022; 20 p. Available online: https://www.climate-transparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CT2022-Russia-web.pdf (accessed on 02 September 2024).

- Greenhouse gas emission factors of the Russian energy system. JSC “TSA”. Available online: https://www.atsenergo.ru/results/co2all (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- Emissions Factors 2023. Annual GHG emission factors for World countries from electricity and heat generation. IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/emissions-factors-2023 (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- International Electricity Factors. Carbon Footprint. Available online: https://www.carbonfootprint.com/international_electricity_factors.html (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- Development of the electricity carbon emission factors for Russia. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Report; 2010; 102 p. Available online: https://www.ebrd.com/downloads/sector/eecc/Baseline_Study_Russia_Final_Russian.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Energy Profile. Russian Federation. IRENA. Report; 2024; 4 p. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Statistics/Statistical_Profiles/Eurasia/Russian-Federation_Eurasia_RE_SP.pdf (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- Abulibdeh, A.; Jawarneh, R.N.; Al-Awadhi, T.; Abdullah, M.M.; Abulibdeh, R.; Kenawy, A.M. Assessment of carbon footprint in Qatar’s electricity sector: A comparative analysis across various building typologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 189, 114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Zh.; Zhao, Yu.; Zhou, Sh.; Zhang, Yi. Prediction of energy-related carbon emission intensity in China, America, India, Russia, and Japan using a novel self-adaptive grey generalized Verhulst model. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 423, 138656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiehbadroudinezhad, M.; Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Rosen, M.A.; Gupta, V.K.; Peng, W.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M. The role of energy security and resilience in the sustainability of green microgrids: Paving the way to sustainable and clean production. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 60, 103485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Liang, S.; Qu, Sh.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Jia, X.; Jia, Y.; Niu, D.; Yuan, J.; Hou, Y.; Wang, H.; Chiu, A.S.F.; Huj, X. Greenhouse gas emission factors of purchased electricity from interconnected grids. Applied Energy 2016, 184, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc-Ata, N.; Proskuryakova, L. N. Empirical analysis of the Russian power industry’s transition to sustainability. Utilities Policy 2023, 82, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melekh, D. Development of a model for calculation greenhouse gas emissions in the category "Manufacturing industries and construction" in the "Energy" sector. Bulletin of Polotsk State University. Series F 2020, 16, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Norway. IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/norway/electricity (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Electricity in Norway in 2023/2024. Low-Carbon Power. Available online: https://lowcarbonpower.org/region/Norway (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Current emissions in Norway. Nowtricity. Available online: https://www.nowtricity.com/country/norway/#:~:text=In%202023%20the%20average%20emissions,countries%20in%20renewable%20energy%20production (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- China. Ember. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/countries-and-regions/china/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Jiaa, M.; Zhangb, Z.; Zhangc, L.; Zhaod, L.; Lud, X.; Lie, L.; Ruang, J.; Wuh, Y.; Heg, Z.; Liud, M.; Jiangi, L.; Gaod, Y.; Wuj, P.; Zhub, Sh.; Niuk, M.; Zhenga, H.; Caib, B.; Tangg, L.; Shul, Y.; Wangb, J. Optimization of electricity generation and assessment of provincial grid emission factors from 2020 to 2060 in China. Applied Energy 2024, 373, 123838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon intensity of the power sector in China from 2000 to 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1300419/power-generation-emission-intensity-china/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Arevalo, P.; Cano, A.; Jurado, F. Mitigation of carbon footprint with 100% renewable energy system by 2050: The case of Galapagos islands. Energy 2022, 245, 123247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 11 Countries leading the charge on renewable energy. Available online: https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/11-countries-leading-the-charge-on-renewable-energy/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Robinson, S.; Sullivan, G. Proposed guidelines for U.S. Scope 2 GHG reduction claims with renewable energy certificates. The Electricity Journal 2022, 35, 107160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wemhoff, A.P. Predicting embodied carbon emissions from purchased electricity for United States counties. Applied Energy 2021, 292, 116898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueken, R.; Klima, K.; Griffin, W.M.; Apt, J. The climate and health effects of a USA switch from coal to gas electricity generation. Energy 2016, 109, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millstein, D.; O’Shaughnessy, E.; Wiser, R. Climate and air quality benefits of wind and solar generation in the United States from 2019 to 2022. Cell Reports Sustainability 2024, 1(6), 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THE EMISSIONS & GENERATION RESOURCE INTEGRATED DATABASE. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-01/egrid2022_technical_guide.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Sosna, M.; Maslennikova, M.; Kryuchkov, M.; Pustovalov, M. «Green» and/or «Blue» Hydrogen. Neftegazokhimiia. Petrochemicals 2020, 34, 21–23. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/zelenyy-i-ili-goluboy-vodorod/viewer (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Hwang, H.; Kweon, T.; Kang, H.; Hwang, Y. Resource and Greenhouse Gas Reduction Effects through Recycling of Platinum Containing Waste. Sustainability 2024, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajulwar, V. V.; Shyrokykh, T.; Stirling, R.; Jarnerud, T.; Korobeinikov, Y.; Bose, S.; Bhattacharya, B.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Sridhar, S. Steel, Aluminum, and FRP-Composites: The Race to Zero Carbon Emissions. Energies 2023, 16(19), 6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman Nilsson, A.; Macias Aragonés, M.; Arroyo Torralvo, F.; Dunon, V.; Angel, H.; Komnitsas, K.; Willquist, K. A Review of the Carbon Footprint of Cu and Zn Production from Primary and Secondary Sources. Minerals 2017, 7(9), 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Song, J.; Liu, Ch.; Yang, W. Evolving water, energy and carbon footprints in China's food supply chain. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 423, 138716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluminium Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Available online: https://international-aluminium.org/statistics/greenhouse-gas-emissions-aluminium-sector/ (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Sustainability. RUSAL. Available online: https://rusal.ru/en/sustainability/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Sotos, M. GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance. An amendment to the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard; 2024; 120 p. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/Scope%202%20Guidance.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- The system operator and technologically isolated power systems have taken an important step towards centralizing operational dispatch control. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/news/press-release/press-release-view/news/22171/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation of 13.08.2018 N 937 "On approval of the Rules for the technological functioning of electric power systems and on amendments to certain acts of the Government of the Russian Federation. Available online: http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001201808160007 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Russian Power System Operator. Available online: http://www.so-ups.ru (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Report on the implementation of the General Scheme for the placement of electric power facilities until 2035; Russian Power System Operator; 2024; 23 p. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/fileadmin/files/company/future_plan/genshema/genshena_reports/genshema_2023_report_.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Hydropower in Russia. Available online: https://www.hydropower.ru/hydropower/analitics.php (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Generation facilities in isolated and hard-to-reach areas in Russia. Analytical Center under the Government of the Russian Federation; 2020; 78 p. Available online: https://ac.gov.ru/uploads/2-Publications/analitika/%D0%B3%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%B8_%D0%B2_%D0%98%D0%A2%D0%A2.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Khondoshko, Y.; Vorobyov, A. Technologically isolated energy systems of Russia. Bulletin of Amur State University. Series: Natural and Economic Sciences 2023, 101, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, A. Nuclear energy development is a prerequisite for the global climate agenda. Energy Policy 2021, 9(163), p. 148. Available online: https://energypolicy.ru/razvitie-atomnoj-energetiki-neobhodimoe-uslovie-globalnoj-klimaticheskoj-povestki/business/2021/14/08/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Scheme and program for the development of the Electric Power Systems of Russia for 2024–2029. Substantiating materials. Consolidated report on the Unified Energy System of Russia. Russian Power System Operator; 2024; 224 p. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/fileadmin/files/company/future_plan/public_discussion/2024/final/sipr_ups_2024-29_fin.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Report on the implementation of the General Scheme for the placement of electric power facilities until 2035; Russian Power System Operator; 2024; 23 p. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/fileadmin/files/company/future_plan/genshema/genshena_reports/genshema_2023_report_.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Operating Area. Russian Power System Operator. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/odu-ural/odu-ural-zone/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Beloyarsk NPP. Russian Power System Operator. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/odu-ural/odu-ural-zone/krupneishie-obekty-ehlektrogeneracii-oehs-urala/belojarskaja-aehs/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Electricity consumption in the IES of the Urals for the first 9 months of 2022 increased by 1.8% compared to the same period in 2021. Russian Power System Operator. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/odu-ural/news/odu-ural-news-view/news/19792/ (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Resolution of the Government of Perm region dated 04.12.2023 No. 953-p "On approval of the regional program "Energy saving and increasing energy efficiency of Perm region for 2023 - 2027". Available online: https://permkrai.ru/upload/iblock/483/8o2kzhdt5hrhdevw07xfe1u2yxl8nk2q/953_p.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Supporting materials. Scheme and Program for the Development of Russian Electric Power Systems for 2023–2028. Perm Region. Russian Power System Operator. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/fileadmin/files/company/future_plan/public_discussion/support_materials/38_Permskii_krai.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Electrical Balance. Federal State Statistics Service. Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/search?q=%D1%8D%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BA%D1%82%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%81 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- OJSC Uralkali begins construction of power plants. Available online: https://www.uralkali.com/ru/press_center/press_releases/item216/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Sulimov, D. D.; Kapralov, D. A. The largest thermal power plant based on Russian GTES-25PA was commissioned in Perm. Turbine and Disel 2015, Nov.-Dec., 4-7. Available online: http://www.turbine-diesel.ru/sites/default/files/n6-2015/Aviadvigatel.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Lukoil launched a power plant in Perm Region for beneficial utilization of associated petroleum gas. Available online: https://lukoil.ru/PressCenter/Pressreleases/Pressrelease/lukoil-zapustil-v-permskom-krae-elektrostantsiiu (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- A power plant for the useful utilization of associated petroleum gas has been launched in Perm Krai. Available online: https://www.permkrai.ru/news/v-permskom-krae-zapushchena-elektrostantsiya-dlya-poleznoy-utilizatsii-poputnogo-neftyanogo-gaza/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Solikamsk papermakers completed construction of new thermal power plant for 4 billion rubles. Available online: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4041398 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- “Aviadvigatel” Launches New Power Plant at “Sibur”. Available online: https://www.kr-media.ru/news/dvigatelestroenie/aviadvigatel-zapustil-novuyu-elektrostantsiyu-na-sibure/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Green Electricity Certificates. Carbon Zero. Available online: https://carbonzero.ru/sertifikaty-zelenoj-elektroenergii/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Carbon Tax. Russian Power System Operator. Available online: https://www.so-ups.ru/fileadmin/files/company/markets/dr/carbon_dr/carbon_dr_021221.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Federal Law of 04.08.2023 N 489-FZ "On Amendments to the Federal Law "On Electric Power Industry" and Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation". Available online: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/49679 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- The first agreements on the sale of green certificates for the Azov and Kola wind farms under the national certification system have been signed. Available online: https://www.ruscable.ru/news/2024/03/18/Podpisany_pervye_dogovory_o_prodazhe_zelenyx_serti/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/russian/vol2.html (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- IPCC updates methodology for greenhouse gas inventories. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/vol2.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- NATIONAL INVENTORY REPORT of anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases not controlled by the Montreal Protocol for 1990 - 2020. Part I; 468 p. Available online: http://downloads.igce.ru/kadastr/RUS_NIR-2022_v1_rev.pdf (accessed on 01 November 2024).

- Order No. 371 of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Russia dated 27.05.2022 "On approval of methods for quantitative determination of greenhouse gas emissions and greenhouse gas absorption". Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/350962750 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- ISO 14064-1:2018; Greenhouse gases. Part 1: Specification with guidance at the organization level for quantification and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and removals. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Order, No. 330 of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Russia dated 29.06.2017 “On approval of methodological guidelines for quantification of indirect energy emissions of greenhouse gases”. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/456079014 (accessed on 09 November 2024).

- GOST R ISO 14064-1-2021; Greenhouse gases. Part 1. Specification with guidance at the organization level for quantification and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and removals. Russian Institute of Standardization: Moscow, Russian Federation, 2021.

- Grid Emission Factors. Available online: https://hpb-s.com/news/energeticheskie-koefficzienty/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Methodological Approach for the Common Default Grid Emission Factor Dataset. Available online: https://unfccc.int/climate-action/sectoral-engagement/ifis-harmonization-of-standards-for-ghg-accounting/ifi-twg-list-of-methodologies (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- PNST 646-2022 Preliminary national standard of the Russian Federation. "Green" standards. "Green" products and "green" technologies. Methodology for assessing the reduction of carbon footprint (approved and put into effect by Order of Rosstandart dated 26.04.2022 N 35-pnst. Available online: https://gostassistent.ru/doc/0508f291-bfa8-46d3-86c3-cf7403ef7091 (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- The concept of calculation and publication of greenhouse gas emission factors for the energy system of the Russian Federation. Association "NP Market Council" and JSC "TSA"; 2022; 41 p. Available online: https://www.np-sr.ru/sites/default/files/koncepciya_kev.pdf (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- Ecoinvent Database, version 3.8; Ecoinvent: Zurich, Switzerland, 2021.

- Council of the Federation Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, (2020, Jan. 23). Implementation of recommendations of parliamentary hearings (Ministry of Energy of Russia, letter dated 23.01.2020 No. MU-644/09). Available online: http://council.gov.ru/media/files/r5ZuW1lJGbzvzueXVYaBUAMbu8FCVQlK.pdf (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- Statistical Review of World Energy. Energy Institute. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review (accessed on 02 October 2024).

- Harmonized IFI Default Grid Factors 2021 v3.1. Available online: https://unfccc.int/climate-action/sectoral-engagement/ifis-harmonization-of-standards-for-ghg-accounting/ifi-twg-list-of-methodologies (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- BROWN TO GREEN. The G20 transition to a low-carbon economy. Climate Transparency; 2017; 36 p. Available online: https://www.climate-transparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Brown-to-Green-Report-2017_web.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Emission Factor. Electricity supplied from grid. Available online: https://www.climatiq.io/data/emission-factor/e47f88bd-e04f-4304-bd96-58746cc9e7b9 (accessed on 05 November 2024).

- Gimadi, V.; Kudrin, A.; Kutuzova, A.; Zvyagintsev, A.; Amiraghyan, A.; Kolobov, O.; Kolojanov, S.; Pominova, I.; Martynyuk, A.; Podlesnaya, A. Carbon intensity of electricity in the world and in Russia. Energy Bulletin 2019, 28 p. Available online: https://ac.gov.ru/archive/files/publication/a/22245.pdf (accessed on 06 October 2024).

- Hirschberg, S.; Wiemer, S.; Burgherr P. Seismic Risk. Energy from the Earth. Deep Geothermal as a Resource for the Future? vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich; 2015; 54 p.

- Dones, R.; Bauer, C.; Bolliger, R.; Burger, B.; Faist Emmenegger, M.; Frischknecht, R.; Heck, T.; Jungbluth, N.; Röder, A. “Life Cycle Inventories of Energy Systems: Results for Current Systems in Switzerland and other UCTE Countries,” Ecoinvent report No. 5, Paul Scherrer Institut Villigen, Swiss Centre for Life Cycle Inventories, Dübendorf, Switzerland, 2007.

- Dormann, C.F.; McPherson, J.M.; Araújo, M.B.; Bivand, R.; Bolliger, J.; Carl, G.; et al. Methods to Account for Spatial Autocorrelation in the Analysis of Species Distributional Data: A Review. Ecography 2007, 30, 609–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungbluth, N.; Büsser, S.; Frischknecht, R.; Flury, K.; Stucki, M. Feasibility of Environmental Product Information Based on Life Cycle Thinking and Recommendations for Switzerland. Journal of Cleaner Production 2012, 28, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R.; Althaus, H.-J.; Bauer, C.; Doka, G.; Heck, T.; Jungbluth, N.; Kellenberger, D.; Nemecek, T. The Environmental Relevance of Capital Goods in Life Cycle Assessments of Products and Services. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2007, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mozzhegorova, Y.; Ilinykh, G.; Korotaev, V. Life Cycle Assessment of a Gas Turbine Installation. Energies 2024, 17, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Energy system | Share of actual installed capacity of the generating facility, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear power plant | Hydroelectric power plants and pumped storage power plants | Thermal power plant | Renewable energy sources | |

| UES of Russia | 11.9 | 20.2 | 66.0 | 1.9 |

| IES of North-West | 24.4 | 11.8* | 62.9 | 0.8 |

| IES of the Center | 27.3 | 3.6 | 69.1 | – |

| IES of the Middle Volga | 14.5 | 25.2 | 59.3 | 0.9 |

| IES of South | 14.7 | 23.3 | 49.9 | 12.1 |

| IES of the Urals | 2,8 | 3.6* | 92.7 | 0.9 |

| IES of Siberia | – | 48.5* | 50.8 | 0.8 |

| IES of the East | 41.2 | 58.8* | – | – |

| TITES | 2.0 | 48.7* | 49.2 | 0.04 |

| Object name | Commissioning year | Power | Equipment | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PJSC «Uralkali», BKPRU-4 | 2005 | 12.9 MW (1 GTU) |

4 GTU (Siemens SGT-400), waste-heat boilers (JSC Belenergomash) | [60] |

| LLC «LUKOIL-Permnefteorgsintez», GTPP | 2012 | 200 MW, 40 t/h (steam) |

8 power units GTES-25PA (JSC «UEC-Aviadvigatel»), waste-heat boilers MZ (JSC «ZiO-Podolsk») | [61] |

| PJSC LUKOIL, GTPP «Chashkino» | 2020 | 16 MW | GTU-16 (JSC «UEC-Aviadvigatel»), 4 synchronous turbogenerators of 4 MW each (OOO «Elektrotyazhmash-Privod») | [62,63] |

| JSC «Solikamskbumprom» | 2019 | 55 MW | 3 gas-piston units (Wartsila, Finland) | [64] |

| JSC «SIBUR-Khimprom» | 2014 | 6 MW (1 GTPP), 420 ths tons/year (steam) |

3 GTES «Ural-6000» (JSC "UEC-Aviadvigatel"), 3 waste-heat boilers (JSC «Belenergomash») | [65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).