1. Introduction

A comprehensive space research program encompasses activities in the sectors of Earth observation, satellites, connectivity, and space exploration. In all these sectors, but especially in satellites and space exploration, challenging structures are involved where materials serve as technology drivers. Space structures need to operate under severe dynamic thermomechanical loads, endure an intense chemical environment, and simultaneously possess advanced electromagnetic properties. Space materials technology is mainly driven by developments in the aviation sector. Consequently, in the last decade, there has been a transition from monolithic materials to composite materials in space applications.

Despite the high scientific interest and the increasing number of reported works, only two review papers have been published in the literature on the use of composite materials in space applications [

1,

2]. Both reviews refer only to spacecraft. The review by May et al. [

1] includes only non-polymer composite materials while the review by Ince et al. [

2] focuses on emerging composite materials. Moreover, there is no published review on the computational models used for the design and analysis of composite space structures. In the present paper, the state-of-the-art and future prospects of composite applications and computational models are critically reviewed. In addition to the structural aspects, the sustainability of space structures is also addressed.

2. Boundary and Loading Conditions of Space Structures

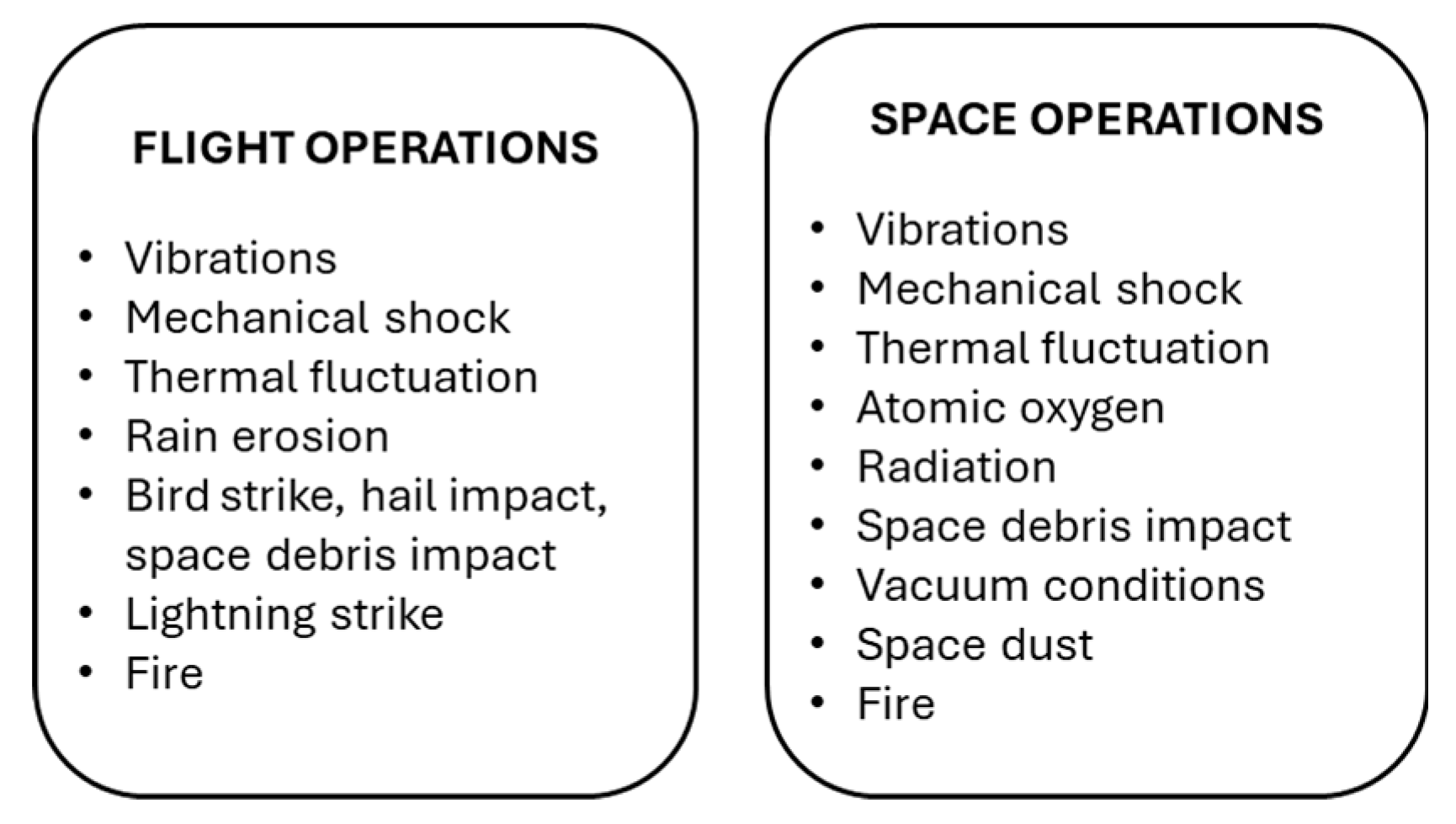

The mission of spacecraft and satellites can be divided into three main phases: ground operations, flight operations and space operations, while the mission of satellites includes only the first two phases. At each mission phase, different loads and environmental conditions apply for space structures. Ground operations is the least demanding phase for structures and materials. Flight operations include launch and flight in Earth atmosphere. Space operations for spacecraft include flight in outer space, landing in another planet and exploration works. The boundary conditions for the flight and space operation phases are shown in

Figure 1.

3. Types of Space Composites

Table 1 presents the different types of composites across the different space applications and loading conditions.

4. Mechanical Response

Mechanical loads of space structures are divided into static loads caused by gravity and dynamic loads (fatigue, high strain rate, vibration, impact, etc.). Most of the published works have focused on dynamic loads.

4.1. Vibration and Damping

Only a few papers have studied vibration and damping of composite space structures. Marchetti et al. [

1] have studied experimentally the damping characteristics of CFRPs, GFRPs and Kevlar/Epoxy composites on the basis of beams and plates, while. O’Neil and Hollaway [

3] have studied experimentally the vibrational characteristics of space composite structures in conjunction with analytical and numerical models. Their combined work has enabled the assessment of local and global modal behavior of skeletal systems.

4.2. Mechanical Properties/Behavior

Studies on the mechanical performance and properties of space composites focus on either characterizing conventional composites under space conditions or developing advanced hybrid composites with improved attributes.

One of the earliest studies on space composites, conducted by [

28], analyzed the mechanical and physical properties of hybrid unidirectional graphite-glass thermoplastics (HMS/E-glass/P1700) used in geodetic beams. Similarly, the thermomechanical behavior of Kevlar/Epoxy composites was experimentally assessed in [

22]. Hyde [

44] highlighted the potential of ceramic matrix composites for space applications due to their exceptional thermomechanical properties, findings that were later supported by research in [

37,

56]. Experimental evaluation of a composite shell structure’s load-bearing capacity under varying loads was performed in [

7]. Meanwhile, [

6] examined the thermomechanical properties of polyaryl-ether-ketone reinforced with functionalized carbon microfibers before and after electron beam irradiation. Innovations addressing specific challenges in space composites have also been documented. For instance, [

38] introduced a novel thermosetting-thermoplastic polyimide composite aerogel to tackle the poor energy absorption and irreversible deformation issues of aerogel materials used in spacecraft fuselages. The impact of rubber particles on the mechanical properties of polymer composites was experimentally investigated in [

36], while [

47] developed a plasma-enhanced cross-linked poly(p-xylylene) diamond-like carbon superlattice material for enhanced mechanical integration with soft polymeric and composite materials. Surface treatment and processing of thermoplastic composites, specifically carbon fibers/polyphenylene sulfide (CF/PPS), for aerospace applications were explored in [

4]. On a broader scale, Giusto et al. [

9] proposed three applications for composite grid structures in payloads and launch vehicles, detailing the preliminary design approach and material selection process. Efforts to reinforce composites using nanoparticles were reported in [

30,

32], with [

30] achieving a 500-625% enhancement in the thermal and electrical conductivities of CFRPs through the addition of carbon nanotubes, enabling effective electroplating of the material.

Finally, the friction and wear properties of composites were studied experimentally in [

25,

27]. Research in [

25] tested carbon/polyimide and aramid/polyimide composites under simulated space irradiation and a start–stop friction process, whereas [

27] evaluated a self-lubricating composite designed for ball bearing lubrication.

4.3. Hypervelocity Impact

Hypervelocity impacts caused by space debris or micro-meteoroids present a high risk for space structures. However, the published work is limited. There have been reported two works on the design of novel shields and bumpers, one work on the impact toughness of CFRPs and one work on novel testing methods. In [

39], a novel shield configuration with a front bumper made from a TiB

2-based composite was designed and tested. In [

8], the efficiency of directly curable carbon, Zylon and Twaron composites as front bumpers for inflatable space structures was evaluated experimentally. In [

40], the effect of density, type of weaving, width of fibers and the number of layers of fiberglass and basalt fabric on the impact toughness has been studied. Also, CNTs were introduced into a polymeric matrix to enhance the impact toughness. In [

41], a hypervelocity impact shielding system for a space stealth including electromagnetic wave absorption capability and an impact shielding system was developed and validated from design phase to the fabrication phase. An alternative approach has been proposed in [

5] where the authors have presented a characterization of the behavior of a CFRP under dynamic loading in the frame of its application as a thin shield for satellite protection.

5. Thermal Response

In a very early work [

56], research on the minimization of the effects of curing cycles, kind of materials, layup typology, and mold configuration on the residual thermal stresses and distortions of composite antenna reflectors in space platforms was conducted. The developed methods were able to predict the residual distortions as functions of manufacturing parameters. In [

57], a high temperature thermal protection system made from ceramic matrix composites with active cooling achieved by flowing a gas into the sandwich’s core was investigated. The heat exchange of the protection system under Earth re-entry conditions, was evaluated by means of 3D thermal-fluid dynamics analysis. In order to improve the thermomechanical heat storage performance of silica gel/CaCl

2 composites and to evaluate their multi-cycle stability, a new synthesis protocol based on successive impregnation/drying steps by using a matrix with a broad pore size distribution was proposed in [

58]. In [

6], the thermal properties (melting and degradation temperature) of PAEK reinforced with functionalized carbon micro fibres was studied before and after electron beam irradiation, and an improvement was found. In [

59], the high-temperature space charge dynamics of epoxy composites containing micro and nano-AlN fillers under a high electric field were investigated. It was found that the filler addition significantly improves the thermal conductivity of the epoxy resin. In [

18], testing and modeling on spaceflight-quality of a high turndown ratio morphing radiator prototype in a relevant thermal environment are reported. In [

21], a highly conductive CFRP electronic housing was manufactured. Aiming to reduce total energy costs on manufacturing, an out-of-the autoclave manufacturing process was followed. Pitch-based carbon fibers were used to increase the thermal conductivity of the composite material. The results indicate potential gains of around 23% in mass reduction when compared to conventional aluminum electronic boxes.

6. Electrical, Electromagnetic and Radiation-Shielding

6.1. Electrical Conductivity

Similar to the mechanical properties, the reported works on the electrical properties of space composites can be categorized into those that have characterized conventional composite materials under space conditions and those that propose new hybrid composites with enhanced properties.

A representative work on hybrid composites is the work of [

31] in which the authors have studied the electrical properties of CNT epoxy composites containing low CNT loadings (less than 1%). The measurements were conducted in-situ while the specimens were exposed to diverse simulated space conditions. The experimental results showed a reduction of resistivity by 40% due to the simultaneous exposure to high temperatures and low pressures, while the application of simulated sunlight with the concomitant surge in temperature showed a maximum decrease of 58%.

6.2. Radiation and Shielding

In [

33], an experimental and analytical study on the radiation-protective characteristics of multilayer polyimide/lead composites subjected to X-ray radiation has been performed. In [

17], energetic ion beam experiments with space radiation elements,

1H,

4He,

16O,

28Si and

56Fe were conducted to investigate the radiation shielding properties of composite materials. These materials are expected to be used for parts and fixtures of space vehicles. In [

34], a shield that absorbs microwave irradiation was developed for incorporation into an ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE)/hydrogen-rich benzoxazine composite for cosmic radiation shielding and to prevent electronic malfunction. In [

35], the resistance to electron irradiation of polyimide composite with nano-sized lead filler was studied. In [

46], fully-dense ZrB

2 and HfB

2 composites were elaborated by Spark Plasma Sintering with 20 vol% TaSi

2 to replace SiC aiming to improve their oxidation resistance. In [

29], the potential of manufacturing high concentration Graphene Nano-Platelet (GNP) films using liquid thermoplastic Elium® resin was explored. The manufactured composites exhibited excellent EMI shielding effectiveness and impact energy absorption, strength, and stiffness increase in the order of 105%, 48%, and 45% respectively, compared to pristine GFRPs. In [

24], the mitigating space radiation using magnesium(-lithium) and boron carbide composites was studied. It was found that that the lower atomic mass of these materials increased nuclear fragmentation upon cosmic radiation interactions, leading to a softening of the secondary (neutron) radiation spectra.

7. Environmental Degradation and Aging

In a pioneering work, Startsev and Nikishin [

10], have experimentally studied aging of hybrid polymer composites by exposing them on real outer space conditions for 1501 days through the employment on a spacecraft. They measured the strain and strength parameters as well as the mass, density, and thickness changes in the composite materials and found that the principal, dominant process occurring due to the continuous presence in outer space was post-curing of the resin materials, which in turn affected the mechanical characteristics of the composite materials. The same year, Paillous and Pailler [

11], have simulated the long-term exposure of composite laminates in space by subjecting them to electron radiation combined with thermal cycling, or to oxygen atom fluxes. The results show that the synergistic action of electrons and thermal cycling degrades the matrix by chain scission, crosslinking and microcrack damage, altering the composite's properties. In [

15], high dose implantation at energies in the l0-100 keV range using ions of metal or semiconductor materials was used to modify the surface of polymeric materials to produce changes that can yield in improvements in space environmental durability. The results show that computer modelling of the ion implantation process combined with reasonable fluence estimates give a good basis for the choice of implantation conditions. The implantation of silicon and aluminum (singly, binary, or in combination with boron) or yttrium produces a stable, protective oxide-based layer following exposure to HAO. The improvement in chemical resistance of these materials ensures performance without deterioration in long duration space missions. In a recent work, He et al. [

12], studied the effects of atomic oxygen on three commercial composite materials, based on two space-qualified epoxy resins (tetraglycidyl-4,40-diaminodiphenylmethane (TGDDM) cured with a blend of 4,40-methylenebis(2,6-diethylaniline) and 4,40-methylenebis(2-isopropyl-6-methylaniline); and a blend of TGDDM, bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (DGEBA), and epoxidised novolak resin initiated by N’-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-N,N-dimethylurea). Samples were exposed to a total fluence of (3.82 1020atom/cm2), equating to a period of 43 days in low Earth orbit. The flexural rigidity and modulus of all laminates displayed a reduction of 5e10% after the first exposure (equivalent to 20 days in orbit).

8. Advanced Composites

8.1. Shape Memory Composites

In [

55], theoretical calculations and experimental studies were carried out to predict the maximum value of reversible deformation of a composite material based on a polymer matrix reinforced with titanium nickelide fibers. In [

52], an experimental study of a shape memory polymer composite to be used in space antenna reflectors. The studies showed that the composite material has the required shape memory effect and is promising for the production of frames only with thermal insulation. In [

53], shape memory polymer actuators based on carbon resistive heating fibers and epoxy matrix were developed for space applications. Their mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties, as well as their deployment kinetics at both ambient and vacuum conditions, were studied. In [

54], for the first time, shape memory polymer composites (SMPCs) have been exposed in low earth orbit environment by the MISSE-FF platform: two carbon-fiber reinforced laminates with an SMP interlayer were retrieved after 1 year of exposure, and tested on Earth. Results show that flight samples behaved differently, because of their different orientation on MISSE-FF. The applied deformed shape was partially recovered on the sample with zenith orientation during its exposure, but both flight samples did not show any additional shape recovery on-Earth. The other sample, with wake orientation, froze the non-equilibrium shape permanently.

8.2. Self-Healing Composites

A review paper has been published on self-healing composites for space applications [

60]. However, most of the works that have been reviewed do not relate to space applications. On the other hand, only a few papers have been published in this category. The most representative is the work of [

61]. This study explored the application of self-healing composites on impacted space structures. The developed material consisted of microcapsules containing blends of 5-ethylidene-2-norbornene (5E2N) and dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) monomers, combined with ruthenium Grubbs' catalyst. These materials were integrated into an epoxy resin matrix, further enhanced with single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) through a vacuum centrifuging technique. The resulting nanocomposites were infused into woven carbon-fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs). The CFRP specimens were subjected to hypervelocity impact conditions, mimicking the harsh environments encountered in space, using a hypervelocity launcher. The study assessed the self-healing capabilities under these conditions, with particular emphasis on the contribution of SWNTs. The nanotubes played a pivotal role in enhancing the mechanical properties and facilitating the healing process, as discussed with respect to the experimental parameters. This research represents a significant step toward the development of materials capable of autonomously repairing damage in space environments, ensuring the structural integrity and longevity of space components.

8.3. Smart/Sensorized Composites

In [

50], a smart CFRP structure with embedded piezoelectric lead zirconate titanate transducers was used to detect multiple areas of artificial delamination and real impact damage using nonlinear ultrasound. Experimental results revealed that the proposed configuration of embedded piezoelectric lead zirconate titanate transducers can be utilised for on-board ultrasonic inspection of spacecraft composite parts. In [

51], percolation based sensors were introduced into Graphite-PDMS (poly di-methyl siloxane) composites for measuring micro-strains and temperature. Changes in both temperature and strain can be sensed by measuring the change in resistance across the electrodes of the sensing element.

In [

58], a new synthesis protocol was proposed to improve the performance of composite materials based on a silica gel loaded with CaCl2, which are used for seasonal thermochemical heat storage.

9. Composites in Deployable Structures

Deployable structures are assemblies which do not aim motion but to attain different configurations. They deploy from a folded state to a desired configuration. These structures are widely used in space applications due to storage limitations of launch vehicles. Therefore, they have been applied in structural designs and concepts for various aerospace missions, including space support booms, space deployable antennas, solar panels, as well as flexible solar sails. In the last few years, research activities on composite deployable space structures have been intensified.

In [

48], a multifunctional composite hinge with integrated piezoelectric actuation capabilities for deployable space is developed. Finite element simulations and experimental testing are utilized to design and validate the multifunctional high strain composite hinge. In [

62], nonlinear dynamic modeling methods for a flower-like clustered deployable space telescope (DST) with laminated composite material experiencing large deployment and attitude adjustment motions is proposed are presented. Moreover, experiments for evaluating the dynamic behavior of surrounding mirrors with simultaneous deployment in different deployment strategies were conducted. Numerical results are in good agreement with those obtained from experiments to validate the correctness of the present nonlinear modeling formulation. In [

13], the geometrically nonlinear behavior of deployable composite booms undergoing large displacements and rotations is investigated. The mathematical model makes use of higher-order 1D structural theories based on the Carrera unified formulation, which allows the description of moderate nonlinearities to deep post-buckling mechanics of ultra-thin shells in a hierarchical and scalable manner. Particular attention is focused on the study of equilibrium paths of the booms subjected to coiling bending. Dedicated experimental tests reveal the validity of the proposed finite element approach, whereas the investigation of different lamination sequences offers a valuable perspective for possible future designs. In [

63], a practical FE-based design procedure of a new configuration of anisogrid composite lattice spoke of an umbrella-type deployable reflector of space antenna is presented. In a series of works, [

64,

65], Liu and Bai have studied the folding behaviour of a deployable composite cabin for space habitats using analytical methods [

64] and numerical and experimental methods [

65]. In [

14], a data-driven computational framework combining machine learning and multi-objective optimization is developed for the design of space deployable bistable composite structures with C-cross section. A C-cross section thin-walled deployable composite structure has bi-stability compared with other deployable structures, which has attracted many attentions thanks to its application prospects in roll-out solar array. In order to get the optimal geometric parameters of subtended angle, thickness, initial radius and longitudinal length, combination methods of finite element method, multi-objective optimization technique and experiment method for bistable composite structures with C-cross section are proposed in this article. In [

66], the folding behaviour of the tubular deployable composite boom was investigated by analytical modeling. Based on the Archimedes’ helix, the geometrical model of the DCB was established. By combining equilibrium equation and energy principle, an analytical model to predict the folding moment versus rotational displacement of the DCB was presented. The failure indices in the equal-sense and opposite sense folding processes were calculated utilizing Tsai-Hill and maximum stress criteria. Analytical results agreed well with experimental and numerical results. At last, the influence of geometric parameters (i.e., radius, central angle and thickness of cross-section) on the folding behaviour of the DCB was further studied using the analytical model.

10. Computational Models

Computational models have seen limited application in composite space structures compared to their widespread use in composite aerostructures. This disparity stems partly from the differences in constituent materials and, more significantly, from the unique loading and boundary conditions of space environments. Space structures are subject to complex phenomena, such as rain erosion, micrometeoroid and space dust impacts, and atomic oxygen exposure, which are not yet fully described analytically or numerically. Existing computational efforts predominantly focus on the dynamic behavior of deployable structures [

13,

48,

62,

63,

64,

66]. For example, a data-driven methodology leveraging Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks was proposed in [

67] to detect multiple damage locations in solar arrays. These damage locations were generated using finite element models of the arrays. The deep learning framework's performance was assessed using two sensor types: accelerometers and piezoelectric patches. In both cases, the framework effectively identified damaged elements with limited time-series data. Additionally, [

68] presented a numerical investigation into the thermomechanical performance and failure mechanisms of honeycomb core composite sandwich structures with bonded fittings under extreme temperature ranges. These studies highlight ongoing progress in adapting computational techniques to address the unique challenges of space-structure applications.

11. Conclusions

From the literature review of published journal papers on the space applications of composite materials, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Expanding Applications: Composites are increasingly used in space structures, yet their application remains limited. There is a pressing need for new materials capable of withstanding combined loading conditions characteristic of the space environment.

Limited Publications: The number of publications on this topic is relatively small compared to the wealth of information available online. This limitation is partly due to much of the research being conducted within national or cooperative space programs, which often restrict public dissemination.

Material Challenges: The harsh space environment demands advanced mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. Research is ongoing into novel matrix and fiber materials, hybrid composites, lattice reinforcements, and nanoparticle enhancements. Although significant improvements in properties have been achieved, current composites remain brittle and weak under cryogenic conditions and are prone to degradation at high temperatures. These challenges are particularly pronounced for large-volume applications.

Role of Computational Models and AI: Computational models have primarily been applied to deployable structures. Combined with artificial intelligence, they hold great potential for advancing the simulation-driven design of next-generation composite materials.

Rapid Developments: Deployable structures, structural health monitoring (SHM) concepts, and smart composites are advancing rapidly, offering promising avenues for the future of composite space applications.

This review underscores the importance of continued material innovation and computational advancements to meet the stringent demands of space environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.I.; methodology, K.I.; formal analysis, K.I.; investigation, K.I.; writing—original draft preparation, K.I.; writing—review and editing, K.I.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

References

- Marchetti, M.; Morganti, F.; Mucciante, L.; Bruno, C. Damping of Composite Plate for Space Structures: Prediction and Measurement Methods. Acta Astronautica 1987, 15, 157–164. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A. New Aspects Relating to the Behaviour of Composites in Space. Composites Engineering 1992, 2, 137–147. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M.; Hollaway, L. Vibrational Characteristics of Composite Structures for Space. Composites Engineering 1992, 2, 177–195. [CrossRef]

- De O.C. Cintra, M.P.; Santos, A.L.; Silva, P.; Ueda, M.; Janke, A.; Jehnichen, D.; Simon, F.; Botelho, E.C. Characterization of SixOyNz Coating on CF/PPS Composites for Space Applications. Surface and Coatings Technology 2018, 335, 159–165. [CrossRef]

- Jaulin, V.; Chevalier, J.-M.; Arrigoni, M.; Lescoute, E. Characterization of a Carbon Fiber Composite Material for Space Applications under High Strains and Stresses: Modeling and Validation by Experiments. Journal of Applied Physics 2020, 128, 195901. [CrossRef]

- Peter, P.; Remanan, M.; Bhowmik, S.; Jayanarayanan, K. Polyaryl Ether Ketone Based Composites for Space Applications: Influence of Electron Beam Radiation on Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 24, 490–499. [CrossRef]

- Kravchuk, L.V.; Buiskikh, K.P.; Derevyanko, I.I.; Potapov, O.M. Load-Bearing Capacity of Elements of Composite Shell Structures in Rocket and Space Engineering Made of Composite Materials. Strength Mater 2022, 54, 613–621. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, C.; Sathish Kumar, S.K.; Kim, C.-G. Hypervelocity Impact on Flexible Curable Composites and Pure Fabric Layer Bumpers for Inflatable Space Structures. Composite Structures 2017, 176, 1061–1072. [CrossRef]

- Giusto, G.; Totaro, G.; Spena, P.; De Nicola, F.; Di Caprio, F.; Zallo, A.; Grilli, A.; Mancini, V.; Kiryenko, S.; Das, S.; et al. Composite Grid Structure Technology for Space Applications. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 34, 332–340. [CrossRef]

- Startsev, O.V.; Nikishin, E.F. Aging of Polymer Composite Materials Exposed to the Conditions in Outer Space. Mech Compos Mater 1994, 29, 338–346. [CrossRef]

- Paillous, A.; Pailler, C. Degradation of Multiply Polymer-Matrix Composites Induced by Space Environment. Composites 1994, 25, 287–295. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Suliga, A.; Brinkmeyer, A.; Schenk, M.; Hamerton, I. Atomic Oxygen Degradation Mechanisms of Epoxy Composites for Space Applications. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2019, 166, 108–120. [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.; Augello, R.; Carrera, E. Numerical Simulation of Deployable Ultra-Thin Composite Shell Structures for Space Applications and Comparison with Experiments. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures 2023, 30, 1591–1603. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Ma, J.; Xiong, L.; Ren, S.; Sun, M.; Wu, H.; Jiang, S. Space Deployable Bistable Composite Structures with C-Cross Section Based on Machine Learning and Multi-Objective Optimization. Composite Structures 2022, 297, 115983. [CrossRef]

- Iskanderova, Z.A.; Kleiman, J.; Morison, W.D.; Tennyson, R.C. Erosion Resistance and Durability Improvement of Polymers and Composites in Space Environment by Ion Implantation. Materials Chemistry and Physics 1998, 54, 91–97. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, M.; Grogan, D.M.; Goggins, J.; Appel, S.; Doyle, K.; Leen, S.B.; Ó Brádaigh, C.M. Permeability of Carbon Fibre PEEK Composites for Cryogenic Storage Tanks of Future Space Launchers. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2017, 101, 173–184. [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Kitamura, H.; Koike, M.; Kusano, H.; Kusumoto, T.; Uchihori, Y.; Endo, T.; Hagiwara, Y.; Kiyono, N.; Kodama, H.; et al. Applicability of Composite Materials for Space Radiation Shielding of Spacecraft. Life Sciences in Space Research 2021, 31, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Walgren, P.; Nevin, S.; Hartl, D. Design, Experimental Demonstration, and Validation of a Composite Morphing Space Radiator. Journal of Composite Materials 2023, 57, 347–362. [CrossRef]

- Pastore, R.; Delfini, A.; Albano, M.; Vricella, A.; Marchetti, M.; Santoni, F.; Piergentili, F. Outgassing Effect in Polymeric Composites Exposed to Space Environment Thermal-Vacuum Conditions. Acta Astronautica 2020, 170, 466–471. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-H.; Kim, C.-G. Low Earth Orbit Space Environment Simulation and Its Effects on Graphite/Epoxy Composites. Composite Structures 2006, 72, 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Gomes, R.; Pina, L.; Pereira, C.; Reichmann, O.; Teti, D.; Correia, N.; Rocha, N. Highly Conductive Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composite Electronic Box: Out-Of-Autoclave Manufacturing for Space Applications. Fibers 2018, 6, 92. [CrossRef]

- Crema, L.B.; Barboni, R.; Castellani, A. Thermoelastic Behaviour of Space Structures in Composite Materials. Acta Astronautica 1986, 13, 547–552. [CrossRef]

- Deruyttere, A.; Froyen, L.; De Bondt, S. Melting and Solidification of Metallic Composites in Space. Advances in Space Research 1986, 6, 101–110. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Park, C.; Baciak, J.E.; Manuel, M.V. Mitigating Space Radiation Using Magnesium(-Lithium) and Boron Carbide Composites. Acta Astronautica 2024, 216, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zheng, F.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Liang, Y. Friction and Wear Behaviors of Carbon and Aramid Fibers Reinforced Polyimide Composites in Simulated Space Environment. Tribology International 2015, 92, 246–254. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, K.; Shi, X.; Li, H.; Ma, C.; Hu, C.; Wang, L.; Cheng, C. Effects of Space Extreme Temperature Cycling on Carbon/Carbon-(Zr-Si-B-C-O) Composites Performances. Corrosion Science 2019, 147, 212–222. [CrossRef]

- Colas, G.; Saulot, A.; Michel, Y.; Filleter, T.; Merstallinger, A. Experimental Analysis of Friction and Wear of Self-Lubricating Composites Used for Dry Lubrication of Ball Bearing for Space Applications. Lubricants 2021, 9, 38. [CrossRef]

- Garibotti, J.F.; Cwiertny, A.J.; Johnson, R. Development of Advanced Composite Materials and Geodetic Structures for Future Space Systems. Acta Astronautica 1982, 9, 473–480. [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Khalid, M.Y.; Andrew, J.J.; Ali, M.A.; Zheng, L.; Umer, R. Co-Cured GNP Films with Liquid Thermoplastic/Glass Fiber Composites for Superior EMI Shielding and Impact Properties for Space Applications. Composites Communications 2023, 44, 101767. [CrossRef]

- Vartak, D.; Ghotekar, Y.; Munjal, B.S.; Bhatt, P.; Satyanarayana, B.; Lal, A.K. Characterization of Tailored Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Based Composite for Geo-Space Payload Components. Journal of Elec Materi 2021, 50, 4442–4449. [CrossRef]

- Earp, B.; Hubbard, J.; Tracy, A.; Sakoda, D.; Luhrs, C. Electrical Behavior of CNT Epoxy Composites under In-Situ Simulated Space Environments. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 219, 108874. [CrossRef]

- Seibers, Z.; Orr, M.; Collier, G.S.; Henriquez, A.; Gabel, M.; Shofner, M.L.; La Saponara, V.; Reynolds, J. Chemically Functionalized Reduced Graphene Oxide as Additives in Polyethylene Composites for Space Applications. Polymer Engineering & Sci 2020, 60, 86–94. [CrossRef]

- Cherkashina, N.I.; Pavlenko, V.I.; Noskov, A.V.; Novosadov, N.I.; Samoilova, E.S. Using Multilayer Polymer PI/Pb Composites for Protection against X-Ray Bremsstrahlung in Outer Space. Acta Astronautica 2020, 170, 499–508. [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.-H.; Jang, W.-H.; Noh, J.-E.; Choi, W.-H.; Kim, C.-G. A Space Stealth and Cosmic Radiation Shielding Composite: Polydopamine-Coating and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Grafting onto an Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene/Hydrogen-Rich Benzoxazine Composite. Composites Science and Technology 2022, 230, 109711. [CrossRef]

- Cherkashina, N.I.; Pavlenko, V.I.; Noskov, A.V.; Romanyuk, D.S.; Sidelnikov, R.V.; Kashibadze, N.V. Effect of Electron Irradiation on Polyimide Composites Based on Track Membranes for Space Systems. Advances in Space Research 2022, 70, 3249–3256. [CrossRef]

- Jeremy Jeba Samuel, J.; Ramadoss, R.; Gunasekaran, K.N.; Logesh, K.; Gnanaraj, S.J.P.; Munaf, A.A. Studies on Mechanical Properties and Characterization of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Hybrid Composite for Aero Space Application. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 47, 4438–4443. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Chen, Z. Mechanical Behavior of C/SiC Composites under Simulated Space Environments. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2012, 534, 408–412. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Tian, K.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Q.; Zheng, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Cheng, S.; Fan, Z.; Fan, X.; et al. A Combination of “Inner - Outer Skeleton” Strategy to Improve the Mechanical Properties and Heat Resistance of Polyimide Composite Aerogels as Composite Sandwich Structures for Space Vehicles. Composites Science and Technology 2024, 252, 110620. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yin, C.; Huang, J.; Wen, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, J.; Liu, S. Hypervelocity Impact of TiB2-Based Composites as Front Bumpers for Space Shield Applications. Materials & Design 2016, 97, 473–482. [CrossRef]

- Kobzev, V.A.; Chechenin, N.G.; Bukunov, K.A.; Vorobyeva, E.A.; Makunin, A.V. Structural and Functional Properties of Composites with Carbon Nanotubes for Space Applications. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 26096–26103. [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.-W.; Sathish Kumar, S.K.; Ankem, V.A.; Kim, C.-G. Multi-Functional Aramid/Epoxy Composite for Stealth Space Hypervelocity Impact Shielding System. Composite Structures 2018, 193, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Shemelya, C.; De La Rosa, A.; Torrado, A.R.; Yu, K.; Domanowski, J.; Bonacuse, P.J.; Martin, R.E.; Juhasz, M.; Hurwitz, F.; Wicker, R.B.; et al. Anisotropy of Thermal Conductivity in 3D Printed Polymer Matrix Composites for Space Based Cube Satellites. Additive Manufacturing 2017, 16, 186–196. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.; Rinaldi, M.; Pigliaru, L.; Cecchini, F.; Nanni, F. Investigating the Use of 3D Printed Soft Magnetic PEEK -based Composite for Space Compliant Electrical Motors. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2022, 139, 52150. [CrossRef]

- Hyde, A.R. Ceramic Matrix Composites: High-Performance Materials for Space Application. Materials & Design 1993, 14, 97–102. [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekar, S.; Ganesan, A.T.; Rani, T.L.; Vinjamuri, V.K.; Nageswara Rao, M.; Shankar, E.; Dharamvir; Kumar, P.S.; Misganaw Golie, W. A Comprehensive Study of Ceramic Matrix Composites for Space Applications. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2022, 2022, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; Balat-Pichelin, M.; Rapaud, O.; Bêche, E. Oxidation Resistance and Emissivity of Diboride-Based Composites Containing Tantalum Disilicide in Air Plasma up to 2600 K for Space Applications. Ceramics International 2022, 48, 27878–27890. [CrossRef]

- Delkowski, M.; Smith, C.T.G.; Anguita, J.V.; Silva, S.R.P. Increasing the Robustness and Crack Resistivity of High-Performance Carbon Fiber Composites for Space Applications. iScience 2021, 24, 102692. [CrossRef]

- Echter, M.A.; Gillmer, S.R.; Silver, M.J.; Reid, B.M.; Martinez, R.E. A Multifunctional High Strain Composite (HSC) Hinge for Deployable in-Space Optomechanics. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 105010. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Younes, M.H.; Zaib, A.; Farooq, U.; Khan, A.; Zahid, M.D.; Hussan, U. Investigation of Space Charge Behavior in Self-Healing Epoxy Resin Composites. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2021, 32, 19646–19654. [CrossRef]

- Andreades, C.; Malfense Fierro, G.P.; Meo, M.; Ciampa, F. Nonlinear Ultrasonic Inspection of Smart Carbon Fibre Reinforced Plastic Composites with Embedded Piezoelectric Lead Zirconate Titanate Transducers for Space Applications. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2019, 30, 2995–3007. [CrossRef]

- Oppili Prasad, L.; Sreelal Pillai, S.; Sambandan, S. Micro-Strain and Temperature Sensors for Space Applications with Graphite-PDMS Composite. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Flexible and Printable Sensors and Systems (FLEPS); IEEE: Glasgow, United Kingdom, July 2019; pp. 1–3.

- Moskvichev, E.V.; Larichkin, A.Yu. Study of the Functional and Mechanical Properties of a Shape Memory Polymer Composite for a Space Antenna Reflector. Inorg Mater 2021, 57, 1491–1496. [CrossRef]

- Margoy, D.; Gouzman, I.; Grossman, E.; Bolker, A.; Eliaz, N.; Verker, R. Epoxy-Based Shape Memory Composite for Space Applications. Acta Astronautica 2021, 178, 908–919. [CrossRef]

- Santo, L.; Quadrini, F.; Bellisario, D.; Iorio, L.; Proietti, A.; De Groh, K.K. Effect of the LEO Space Environment on the Functional Performances of Shape Memory Polymer Composites. Composites Communications 2024, 48, 101913. [CrossRef]

- Kollerov, M.Yu.; Lukina, E.A.; Gusev, D.E.; Vinogradov, R.E. Functional Metal-Polymer Composite Materials with Reversible Shape Memory Effect for Aeronautical and Space Structures. Russ. Aeronaut. 2020, 63, 730–738. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.; Morganti, F.; Tizzi, S. Evaluation of the Built-in Stresses and Residual Distortions on Cured Composites for Space Antenna Reflectors Applications. Composite Structures 1987, 7, 267–283. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Barbato, M.; Esser, B.; Petkov, I.; Kuhn, M.; Gianella, S.; Barcena, J.; Jimenez, C.; Francesconi, D.; Liedtke, V.; et al. Sandwich Structured Ceramic Matrix Composites with Periodic Cellular Ceramic Cores: An Active Cooled Thermal Protection for Space Vehicles. Composite Structures 2016, 154, 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Courbon, E.; D’Ans, P.; Permyakova, A.; Skrylnyk, O.; Steunou, N.; Degrez, M.; Frère, M. Further Improvement of the Synthesis of Silica Gel and CaCl2 Composites: Enhancement of Energy Storage Density and Stability over Cycles for Solar Heat Storage Coupled with Space Heating Applications. Solar Energy 2017, 157, 532–541. [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Zhu, G.; Tanaka, Y.; Miyake, H.; Sato, K.; Chen, X.; Paramane, A. Space Charge Performance of Epoxy Composites with Improved Thermal Property at High Temperature under High Electric Field. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2022, 139, 51877. [CrossRef]

- Pernigoni, L.; Lafont, U.; Grande, A.M. Self-Healing Materials for Space Applications: Overview of Present Development and Major Limitations. CEAS Space J 2021, 13, 341–352. [CrossRef]

- Aïssa, B.; Tagziria, K.; Haddad, E.; Jamroz, W.; Loiseau, J.; Higgins, A.; Asgar-Khan, M.; Hoa, S.V.; Merle, P.G.; Therriault, D.; et al. The Self-Healing Capability of Carbon Fibre Composite Structures Subjected to Hypervelocity Impacts Simulating Orbital Space Debris. ISRN Nanomaterials 2012, 2012, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Yu, X.; Liang, D.; Liu, X.; Yang, X. Numerical and Experimental Investigation on Dynamics of Deployable Space Telescope Experiencing Deployment and Attitude Adjustment Motions Coupled with Laminated Composite Shell. Mechanics Based Design of Structures and Machines 2022, 50, 268–287. [CrossRef]

- Morozov, E.V.; Lopatin, A.V.; Khakhlenkova, A.A. Finite-Element Modelling, Analysis and Design of Anisogrid Composite Lattice Spoke of an Umbrella-Type Deployable Reflector of Space Antenna. Composite Structures 2022, 286, 115323. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-W.; Bai, J.-B. Folding Behaviour of a Deployable Composite Cabin for Space Habitats - Part 1: Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Composite Structures 2022, 302, 116244. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-W.; Bai, J.-B. Folding Behaviour of a Deployable Composite Cabin for Space Habitats – Part 2: Analytical Investigation. Composite Structures 2022, 297, 115929. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-W.; Bai, J.-B.; Fantuzzi, N. Analytical Models for Predicting Folding Behaviour of Thin-Walled Tubular Deployable Composite Boom for Space Applications. Acta Astronautica 2023, 208, 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Angeletti, F.; Gasbarri, P.; Panella, M.; Rosato, A. Multi-Damage Detection in Composite Space Structures via Deep Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 7515. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, K.R.; Stoumbos, T.; Inoyama, D.; Chattopadhyay, A. Computational Analysis of Failure Mechanisms in Composite Sandwich Space Structures Subject to Cyclic Thermal Loading. Composite Structures 2021, 256, 113086. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).