1. Introduction

1.1. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common form of head and neck cancers [

1]. Currently, it is more prevalent in developing countries where daily carcinogenic habits such as chewing tobacco and betel nut are common. It is the most common type of cancer diagnosis in Southeastern Asia, Southern and Eastern Africa, with India also reporting lip and oral cavity cancer as the most common type of cancer mortality in males nationally [

2]. Meanwhile, in the US, approximately 58,450 new cases were expected in 2024, with 12,230 expected deaths [

3]. The use of known carcinogens such as alcohol and chewing tobacco along with Human Papillomavirus infections are the major risk factors involved in developing oral cancer [

4]. In addition to avoiding these risk factors, early detection is key to favorable outcomes; overall five-year survival in the US is 69%, but this figure drops to 39% for those patients with distant metastases [

3].

Currently there is no routine screening program for OSCC, but early detection can be achieved during oral exams by a dentist or a physician, or even self-examination by the patient. Importantly, leukoplakia within the oral cavity can be an early sign of dysplasia or even cancer. Leukoplakia is a clinical term which describes the thin, white plaques within the oral cavity. Upon histopathological examination it was shown that approximately 40% are either dysplastic or premalignant at time of biopsy, and 3% to 15% have the potential to become malignant [

5]. Therefore, as a gold standard for diagnosis, it is recommended that abnormal oral plaques be biopsied and histopathologically evaluated for OSCC. Leukoplakia can be accompanied by underlying epithelial hyperplasia, which is an increased number of normal cells or by dysplasia. Dysplasia is defined as the presence of atypical cells in the epithelia which is not yet malignant. However, dysplastic cells have the potential to become cancerous upon accumulation of additional mutations. These dysplastic cells are termed premalignant because they can potentially progress to invasive carcinomas [

6].

1.2. The Need for Better Diagnostics and Staging

The prognosis for a patient with OSCC diagnosis depends primarily on the TNM (Tumor, Node, and Metastasis) staging system by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). The system is based on the excision of lesions and examining size of the primary tumor (T), whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes (N), and discerning if there is metastasis (M) to distant tissues. Although these parameters can help in the diagnosis and prognostication of OSCC, Woolgar and Triantafyllou suggest that pitfalls in histopathological diagnosing exist due to reliance on morphology features alone and the inherent limitations of staging and misinterpretations. These pitfalls can impact patients’ prognosis [

7]. Additionally, even though an HPV infection is a risk factor for OSCC, currently there is no approved test to screen for HPV in the throat like there is for cervical cancer of HPV infection origin. Molecular biomarkers could serve as a diagnostic and prognostic tool to determine the extent of oral cancer progression and could be beneficial in mitigating poor outcomes for future patients.

Limited studies of biomarkers for OSCC have been performed. Yoshimura et al. found that Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme E2S (UBE2S) was upregulated in nine OSCC cell lines, in addition to other cancer types [

8]. Conversely, Jiang et al. found that expression of tapasin was reduced in OSCC [

9]. We previously showed that in line with other squamous tumors, OSCC shows reduced expression of cornulin [

10,

11]. However, further work in this area is needed, and we aimed to identify new biomarkers to improve OSCC diagnosis and prognosis.

1.3. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition as a Hallmark of Cancer Progression

One potential source of biomarkers is the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway. EMT is vital to tissue remodeling and morphogenesis during normal development [

12]. However, EMT is often reactivated in cancers, allowing malignant cells to migrate and invade surrounding tissues [

13]. Several signals can activate an EMT program, but among the best characterized is TGFβ [

14,

15]. There have been few studies of EMT in OSCC, but Ali et al. showed that well-differentiated OSCC expressed high levels of the epithelial marker E-Cadherin, while poorly differentiated tumors had reduced E-Cadherin and increased N-Cadherin expression. This “cadherin switch” is commonly seen in EMT and reflects the change from anchored epithelium to motile, mesenchymal-like cells [

16]. We sought to confirm this finding in cell line models of OSCC and to expand to other markers of EMT.

In recent years, EMT has been implicated not only in metastasis, but also in changes in stem cell phenotype and drug response across many cancers [

17]. Notably, Steinbichler and colleagues analyzed the effect of treatment with fibroblast conditioned medium of TGFβ on OSCC cells, and found an increase in mesenchymal marker expression and resistance to chemotherapy and radiation [

18,

19]. Ingruber et al. also found a correlation between EMT markers and platinum resistance in a model of OSCC, although they found an inverse relationship between EMT and expression of the stem cell factor Klf4 [

20,

21]. How these findings will translate to the full spectrum of OSCC progression and to other therapeutics remains to be determined.

1.4. Stratifin and GSTP as Additional Potential Biomarkers for OSCC

Stratifin (SFN) was first described in 1967, as part of the larger 14-3-3 family of proteins which are abundantly present in the mammalian brain [

22]. There are seven isoforms present in humans (β-beta, ε-epsilon, γ-gamma, η-eta, σ-sigma, τ-tau, and ζ-zeta) but 14-3-3σ (SFN) is the only one that possesses tumor-suppressing activity [

23,

24]. There is increasing evidence that SFN has a role in suppressing cancer cell growth and metastasis [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. SFN has been implicated in regulating a range of proteins involved in oncogenesis [

27]. The downregulation and reduced expression of SFN has been implicated in esophageal and lung carcinomas along with other squamous cell carcinomas [

28,

29,

30]. The expression of SFN in keratinocytes appears to be epigenetically regulated, and the SFN gene is hyper-methylated in tumors, leading to SFN downregulation and further tumorigenesis [

30,

31]. Some have argued that the role of SFN may be a double-edged sword in that increased expression causes resistance to radiation and anticancer agents in cancer cells [

32]. The increased expression of SFN may also predict poor prognosis in several cancers, including nasopharyngeal, esophageal, oral, and breast carcinoma [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. This study aims to assess SFN as a potential biomarker through the progressive steps of OSCC.

Glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP), known for its function as an antioxidant, has been shown to be increased in preneoplastic and dysplastic lesions of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [

34,

35]. A study conducted by Yang et al. revealed an interaction between GSTP1 increase and EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Additionally, GSTP1-associated EMT contributes to resistance to paclitaxel, a drug closely related to docetaxel [

36]. Given the links with EMT and progression in related tumor types, we hypothesized that GSTP could be another marker of advanced, drug resistant OSCC.

1.5. Modeling OSCC Progression from Normal Tissue to Metastatic Disease

In order to capture the full picture of OSCC progression and biomarker expression, it is necessary to begin with early precancerous lesions. In a study by Waldron and Shafer, it was found that 42.9% of oral leukoplakias on the floor of the mouth showed some degree of epithelial dysplasia or unsuspected invasive squamous cell carcinoma [

37]. Clinically, it is important to be able to differentiate these steps, as close to 36% of leukoplakias progressed into carcinoma [

38]. Furthermore, treatment will be radically different for local disease versus in patients with distant metastasis, so it is of clinical importance to identify tumors that have or may soon spread to other sites.

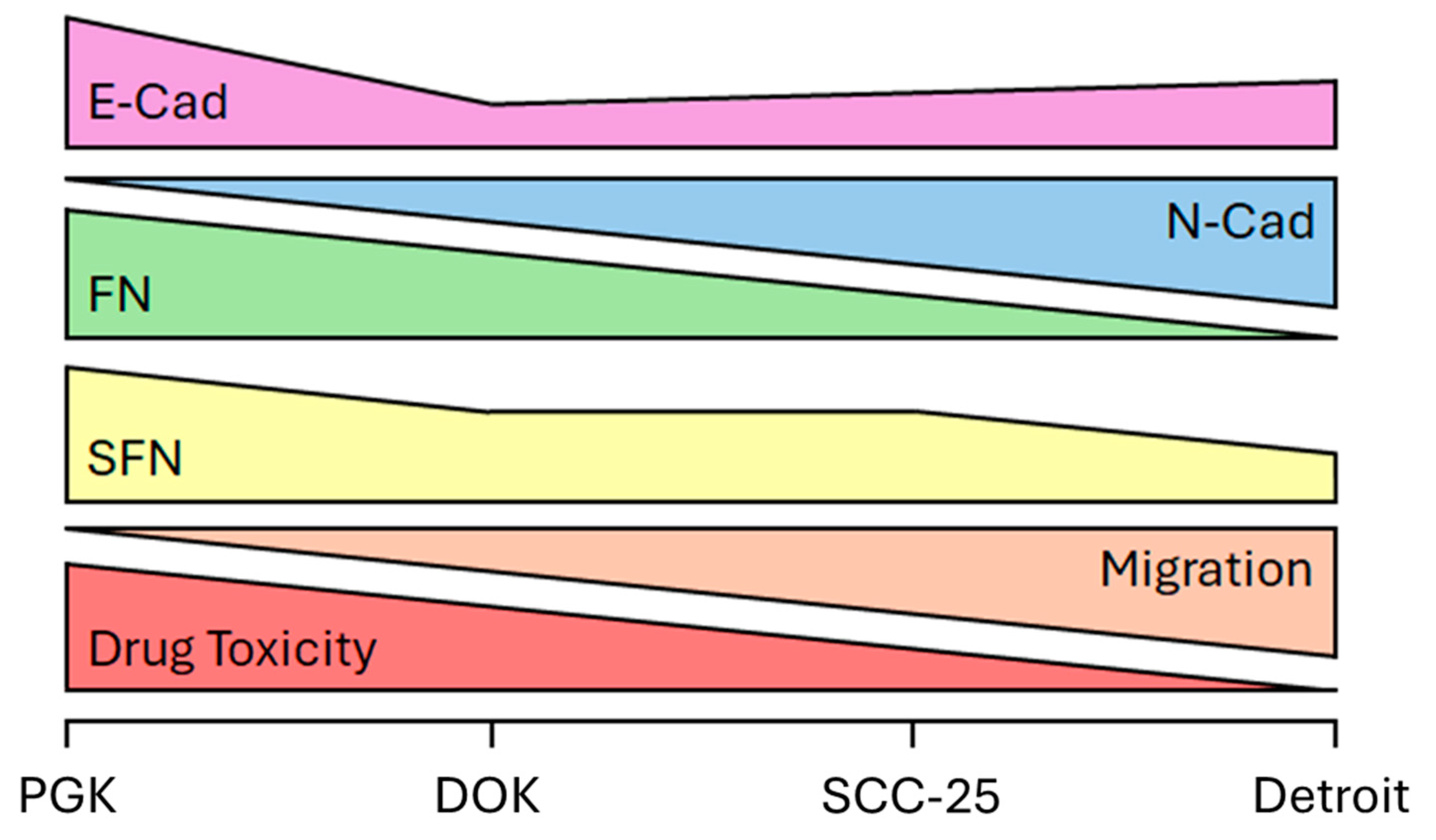

To address all of these concerns, we elected to use a panel of cell lines representing the full spectrum of phenotypes from normal to aggressive OSCC (

Figure 1). Primary gingival keratinocytes (PGK) cells were taken from a 60 year old female patient, and are normal controls. Dysplastic oral keratinocyte (DOK) cells represent mild to moderate dysplasia and were derived from the dorsal tongue of a 57 year old male patient who had been a heavy smoker. SCC-25 is an established OSCC cell line representative of locally invasive carcinoma that was also derived from the tongue of a male patient. Finally, Detroit 562 (Detroit) cells were derived from the pleural effusion of a female patient with metastatic pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, and represent the most aggressive stage of OSCC. These four lines were used in our study to test putative biomarkers of progression, EMT, and therapeutic response at each stage. To our knowledge, ours is the first model to incorporate the full range of OSCC progression all the way from normal tissue to distant metastasis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Four cell lines were used in the study. Primary gingival keratinocytes (PGK) were obtained from ATCC. These cells were maintained in Dermal Cell Basal Medium supplemented with the Keratinocyte Growth Kit, both from ATCC. Dysplastic Oral Keratinocytes (DOK) were obtained from ECACC. DOK cells were maintained in DMEM (ATCC) with 10% FBS and 5μg/mL hydrocortisone (STEMCELL Technologies, Cambridge, MA, USA). SCC-25 oral squamous carcinoma cells were obtained from ATCC and maintained in DMEM:F12 (ATCC) supplemented with 10% FBS and 400 ng/mL hydrocortisone. Detroit 562 cells were obtained from ATCC. These cells were grown in EMEM (ATCC) supplemented with 10% FBS. All cell lines were grown in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. 1% penicillin-streptomycin was added to growth media to prevent bacterial contamination.

2.2. Western Blotting

Cells were harvested and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Following centrifugation of the lysate, protein concentration in the supernatant was determined by BCA Assay (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Equal masses of protein were run on gradient PAGE gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and then transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were rinsed in tris-buffered or phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% Tween-20 (TBST or PBST, respectively) and then blocked in 5% milk in TBST/PBST. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody. The following day, blots were rinsed in TBST/PBST, incubated in secondary antibody for 1-2h, and rinsed again. Blots were then incubated with enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Bio-Rad) and imaged on a ChemiDoc imager (Bio-Rad). ImageJ and Bio-Rad ImageLab software were used to quantify blot images. Primary antibodies used were: SFN (14-3-3 sigma MA5-11663, Invitrogen, 1:1,000), GAPDH (60004-1-IG, ThermoFisher, 1:10,000), GSTP1 (3F2, #3369S, Cell Signaling, 1:2000), TPM1 (#28577-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA, 1:4000), Stratifin (14-3-3 sigma, MA5-11663, Thermo Fisher, 1:1000), E-Cadherin (24E10) (#3195T, Cell Signaling, 1:1000), N-Cadherin (13A9) (NBP1-48309SS, Novus, Centennial, CO, USA, 1:1000), Fibronectin (EP5) (sc-8422, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA, 1:250), and β-Actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:500). HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen and Santa Cruz.

2.3. Scratch Wound Healing Assays

To investigate the migratory ability of the OSCC cell lines at different stages of progression, a wound healing assay was performed. The cells were plated in 24-well plates and allowed to incubate until they reached confluency. A P200 pipette tip was used to create a scratch down the center of each well, simulating a wound. Subsequently, the media was removed, and the wells were gently washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to eliminate any floating cells. Fresh medium was then added to the wells. The 24-well plate was placed into the Celloger Mini Plus live cell imager (Curiosis, Korea), where it was imaged every hour over a 48-hour period. Time-lapse movies and still images were created to visually depict the process of wound closure.

2.4. Drug Response Assays

To assess the response of OSCC cell lines to cisplatin and docetaxel, the Celloger Mini Plus live cell imager was used. Cells were plated at a density of 3,000-6,000 cells per well in a Nunc Edge 96-well plate (ThermoFisher) and allowed to adhere overnight. The following day, varying concentrations of the chemotherapy drugs were added to the respective wells, while PBS was added to all empty wells and to the moat areas of the plate to prevent evaporation. The 96-well plate was then placed in the Celloger Mini Plus live cell imager, and the cells were imaged every four hours over a 72-hour period. The instrument measured the percent confluence of the cells, providing a real-time assessment of cell proliferation over time. Additionally, to quantify cell death throughout the experiment, Sytox dead cell stain reagent (ThermoFisher) was included in the wells (1:667 dilution). This stain fluoresced green when cells died, allowing for the analysis of the green signal area to determine the extent of cell death.

2.5. Statistics and Replication

Pairwise comparisons were analyzed using Student’s t-tests. Comparisons between multiple conditions were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. p < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, versions 9 and 10. All experiments were repeated three times, except where otherwise noted. All graphs show mean ± SEM.

3. Results

3.1. EMT Markers Correlate Well with OSCC Progression in Cell Lines

We hypothesized that SCC-25 and Detroit 562 cells, which have an invasive and metastatic phenotype, would exhibit a more mesenchymal-like gene expression profile. To test this hypothesis, we assayed the expression of three EMT markers by western blot. Surprisingly, the expression of fibronectin (FN) was high in PGK and DOK cells and decreased significantly in SCC-25 and Detroit 562 (

Figure 2A,B). This is in contrast to previous reports that classify FN as a mesenchymal marker in head and neck and other cancers [

39,

40,

41]. As expected, PGK had the highest expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin (E-Cad), with all cancerous cells exhibiting significantly lower E-Cad levels. There was a small upward trend in E-cad expression from DOK to Detroit, however (

Figure 2A,C). In contrast, the mesenchymal marker N-Cadherin (N-Cad) was almost absent in PGK, and its expression increased steadily with OSCC progression (

Figure 2A,D). The inverse relationship of E-Cad and N-Cad is typical of the “cadherin switch,” one hallmark of EMT [

16]. Taken together, our western data suggest that SFN, FN, and cadherin levels together represent a promising panel of diagnostic biomarkers for OSCC staging.

3.2. All Cell Lines Close a Scratch Wound, But Detroit 562 Shows Distinct Projections

We next wanted to determine if increased mesenchymal character meant that our cell lines would display differences in migratory ability. As a simple test, we conducted scratch wound assays with time lapse imaging. We hypothesized that DOK cells would be slow to close a scratch, while SCC-25 and Detroit would be faster to heal. Interestingly, all three cell lines tested were able to close a wound in 24-30 hours (

Figure 3). Looking more closely, we observed that Detroit cells extended long projections at the leading edge of the migrating cell front that were not observed in the other lines (

Figure 3, inset). DOK and SCC-25 cells appeared to be proliferating to a greater extent than Detroit, which may explain why DOK was often able to close the gap the fastest (Supplementary Videos S1-S3). Future studies will examine the ability of each line to invade through an extracellular matrix, which will better distinguish the contributions of proliferation and migration to the apparent motion of the cell population.

3.3. Expression of Stratifin and GSTP Throughout Progression Steps of OSCC

In analyzing the expression of Stratifin (SFN), there was an overall downward trend of decreasing SFN expression as the cancer progressed (

Figure 4A). Pairwise comparisons were made between cell lines representing consecutive steps from normal to dysplasia, dysplasia to locally invasive, and locally invasive to metastatic oral cancer. There was an average relative abundance (SFN/GAPDH) of 0.5 in the normal oral mucosa (PGK), while premalignant oral keratinocytes (DOK) had an average of 0.1. There was a statistically significant difference in SFN expression between these two subsequent steps of OSCC. The locally invasive squamous cell carcinoma cells (SCC25) had an average relative abundance of 0.09. There was no significant difference between these two subsequent steps of OSCC, progressing from dysplasia to locally invasive carcinoma. The metastatic oral carcinoma (Detroit) had an average relative abundance of 0.04, and there was a statistically significant difference between SCC-25 and Detroit (

Figure 4B). Thus, stratifin expression appears to inversely correlate with progression from normal to early-stage to metastatic OSCC. In order to evaluate the utility of GSTP as a biomarker, we performed western blots for this protein in all four cell lines. No significant differences were observed in GSTP expression among the cell lines, although an increasing trend was evident from PGK to Detroit (

Figure 4C,D). These findings highlight SFN as a leading candidate biomarker to add to our EMT panel. Additional studies in patient samples are needed to confirm this, as well as the inverse correlation between SFN and GSTP with progression.

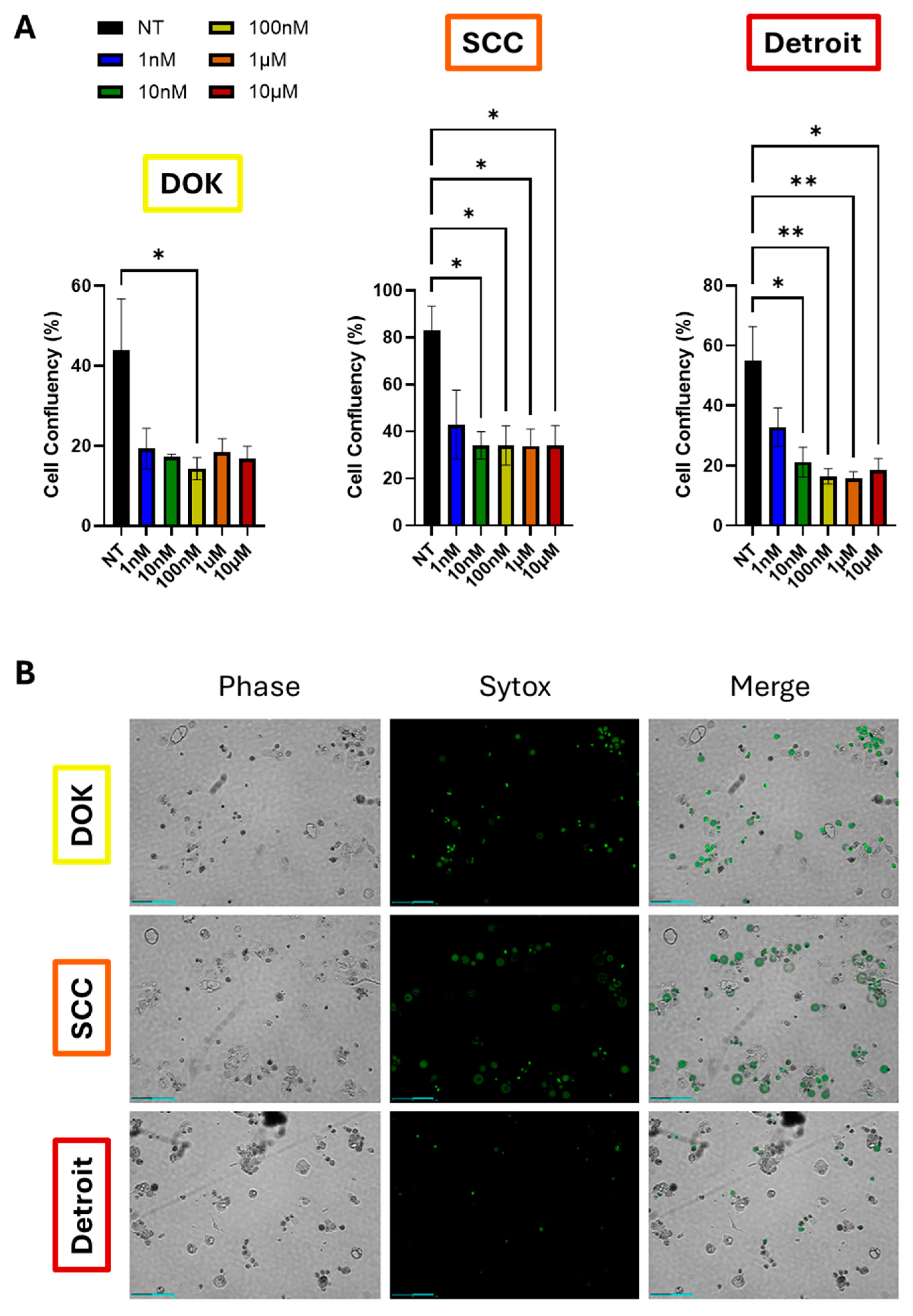

3.4. Detroit Cells Exhibit Distinct Response to Docetaxel Versus Other Lines

Given the correlation between EMT and drug resistance in the literature, as well as the much lower survival rate of metastatic OSCC, we hypothesized that Detroit 562 cells would be resistant to chemotherapy. To test this hypothesis, we treated DOK, SCC-25, and Detroit cells with a ten-fold dose dilution series of docetaxel (range, 1nM-10µM). Drug response was evaluated using automated time lapse imaging via the Celloger Mini Plus imagines system. DOK and SCC-25 cells both showed the same reduction in cell growth and proliferation at all doses tested, as measured by cell confluency (

Figure 5A,

Supplementary Figure S1). Detroit cells also responded to all doses tested, but there was a trend toward dose-dependent reduction in cell growth, with increased growth at 1nM versus higher doses. However, when adjusting for multiple comparisons, this trend did not achieve statistical significance, although the degree of significance between non-treated cells and higher doses did increase (

Figure 5A, right panel). For each experiment, Sytox dead cell stain was added along with docetaxel. Live cells exclude the stain, while dead cells will show green fluorescence. Both DOK and SCC-25 cells showed extensive green signal, particularly at the 10µM dose. However, Detroit 562 cells showed far fewer green cells upon 10µM docetaxel treatment, suggesting that docetaxel can prevent proliferation, but is not outright lethal to Detroit cells to the degree seen in the other lines (

Figure 5B, Supplementary Videos S4–S6). Taken together, these data suggest that Detroit cells are more likely to be therapy resistant, although

in vivo studies will be necessary to evaluate the true extent of this effect.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the relationship between biomarker expression, EMT, drug response, and disease progression in OSCC. We compared four steps of OSCC progression, from normal oral mucosa, to premalignant dysplastic, to locally invasive, to metastatic keratinocytes, using in-vitro cell models (

Figure 1). Throughout this study, we utilized four cell lines as representations of the successive steps of OSCC progression. While other studies have begun to look at biomarkers in OSCC, no studies have covered the full spectrum from normal keratinocytes through metastatic disease. The main significance of our study, therefore, is the full picture painted of changes in molecular signature throughout the course of OSCC.

We sought to tie EMT and therapeutic response to the progression of OSCC. We expected that markers of mesenchymal phenotype would correlate with OSCC progression in our cell line models. Indeed, we confirmed prior reports of a “cadherin switch” [

16] from E-Cad to N-Cad expression in the four cell lines tested (

Figure 5). Interestingly, FN expression markedly decreased with OSCC progression. Fibronectin is widely considered to be a marker of mesenchymal cells, so observation of the opposite trend in these cell lines was unexpected [

39,

40,

41]. It may be that oral mucosa keratinocytes differ from other tissues in which cancer EMT takes place. In any event, it will be of great interest to see if this trend is recapitulated in OSCC patient samples. In wound healing assays, we observed projections in Detroit 562 cells that were absent in the other two cell lines, suggesting these cells more readily migrated. However, all three lines tested were able to close a scratch wound (

Figure 6). Future studies will use transwell assays with and without artificial matrix, in order to distinguish the relative contributions of proliferation and migration to the results we show here and to evaluate each line’s ability to invade through ECM.

Stratifin, or 14-3-3σ, has been found to be expressed in epithelial keratinocytes and has shown to possess tumor suppressing activity [

23,

24]. Findings from our study showed that there was an overall decrease in SFN expression as OSCC progressed from normal oral mucosa to premalignant lesions, to locally invasive to metastatic phenotype (

Figure 2). Clinically, the change from normal to premalignant cell type may serve as a diagnostic marker of the potential of developing cancer [

42]. Regarded as a tumor suppressor, SFN expression has been shown to be downregulated in several carcinomas, including lung, breast and esophageal cancer [

29,

30,

43]. Notably, decreased SFN expression was also found to be correlated with lymph node metastasis. This emphasizes the utility of SFN as a prognostic factor since poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients is associated with lymph node metastases [

44]. Consistent with these findings, we show SFN to be downregulated when comparing normal oral mucosa to oral cancer, suggesting that it might serve as both a diagnostic and prognostic factor for oral carcinoma patients. While the trend seen in GSTP expression in our lines did not achieve statistical significance, it would be of interest to analyze GSTP expression in a larger panel of patient tumor samples. It may also be that GSTP has a place in a panel of markers. By itself, it is not sufficient to discriminate between OSCC stages, but in a panel of markers may have predictive power.

Given the poor prognosis of advanced stage disease, we hypothesized that EMT and progression would both correlate with reduced therapeutic responses. Therefore, we analyzed survival of DOK, SCC-25, and Detroit cells following treatment with docetaxel (Figure 7). While cell confluence was similar across all cell lines, especially at high doses, Detroit cells appeared more resistant to cell death, as indicated by reduced Sytox staining (Figure 7D). Therefore, we conclude that progression does lead to reduced response to docetaxel, which tracks with reduced survival rates in patients with advanced OSCC. Tumors that have spread far beyond the primary site and that can remain dormant during therapy would naturally be more difficult to eliminate.

A key advantage of the cell line models we chose was their homogeneity, however, because of this, the lines may not reflect the complexity of the tumor microenvironment from tissue biopsies. To validate the findings of this study, immunohistochemical analysis of proteins of interest in a large cohort of OSCC patients is planned to establish the diagnostic and prognostic utility of these potential biomarkers in a clinical setting.

5. Conclusions

A schematic of our findings is shown in

Figure 6. We show that SFN expression decreases from normal to precancerous lesions and from early to advanced stage OSCC. SFN expression is correlated with E-Cad and FN expression, and inversely proportional to N-Cad expression, in four cell lines representing the course of OSCC progression. Detroit 562 cells exhibited less cell death versus other lines in response to docetaxel treatment. Therefore, SFN, FN, and E-Cad/N-Cad expression represent a potential panel of biomarkers to accurately stage OSCC tumors and provide information about progression and likely therapeutic responses throughout treatment. GSTP may yet prove to be a valuable addition, but further studies are needed. Validation of this biomarker panel in patient samples will be required before these findings can be brought to bear on future cases.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Full Time Course of Celloger Drug Assay; Video S1: Migration of DOK Cells; Video S2: Migration of SCC-25 Cells; Video S3: Migration of Detroit 562 Cells; Video S4: Growth and Death of DOK Cells; Video S5: Growth and Death of SCC-25 Cells; Video S4: Growth and Death of Detroit 562 Cells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and C.M.R.; Methodology, H.A. and C.M.R.; Validation, M.Z.H., S.R., H.A. and C.M.R.; Formal Analysis, M.Z.H., S.R., and C.M.R.; Investigation, M.Z.H., S.R., and C.M.R.; Resources, H.A. and C.M.R.; Data Curation, M.Z.H., S.R., H.A. and C.M.R.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.Z.H., S.R., and C.M.R.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.Z.H., S.R., H.A. and C.M.R.; Visualization, M.Z.H. and S.R.; Supervision, H.A. and C.M.R.; Project Administration, H.A. and C.M.R.; Funding Acquisition, H.A. and C.M.R.

Funding

This work was supported by the Midwestern University Biomedical Sciences Program with funds allotted to H.A. and C.M.R. for the projects of S.R. and M.Z.H., respectively. Additional support came from Midwestern University startup funds to C.M.R.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article or the supplementary information available accompanying the article online.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr. Zaid A. Rammaha, Mr. Gustavo Untiveros, and Mr. Jihad Aburas for their assistance with this project. We also wish to thank Ellen Kohlmeir and the Midwestern University Core Facility, Downers Grove, IL. BCA assays were performed using the PerkinElmer EnSpire Plate Reader, and cells were counted using the Denovix CellDrop automated cell counter located in the Core.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roser, S.; Nelson, S.; SR, C.; Magliocca, K. Head and Neck Cancer. In The ADA Practical Guide to Patients with Medical Conditions; Wiley, 2015; pp. 273–298.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2024. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boscolo-Rizzo, P.; Furlan, C.; Lupato, V.; Polesel, J.; Fratta, E. Novel Insights into Epigenetic Drivers of Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Role of HPV and Lifestyle Factors. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Woo, S.B. Leukoplakia—A Diagnostic and Management Algorithm. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, B.W.; Day, T.A. Oral Cancer and Precancerous Lesions. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2002, 52, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolgar, J.A.; Triantafyllou, A. Pitfalls and Procedures in the Histopathological Diagnosis of Oral and Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and a Review of the Role of Pathology in Prognosis. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, S.; Kasamatsu, A.; Nakashima, D.; Iyoda, M.; Kasama, H.; Saito, T.; Takahara, T.; Endo-Sakamoto, Y.; Shiiba, M.; Tanzawa, H.; et al. UBE2S Associated with OSCC Proliferation by Promotion of P21 Degradation via the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 485, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Pan, H.; Ye, D.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, Z. Downregulation of Tapasin Expression in Primary Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Association with Clinical Outcome. Tumor Biol. 2010, 31, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdjoudj, M.; Arnouk, H. Characterization of Cornulin as a Molecular Biomarker for the Progression of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cureus 2022, 14, e32210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankavaram, V.; Shah, D.; Alashqar, A.; Sweeney, J.; Arnouk, H. Cornulin as a Key Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker in Cancers of the Squamous Epithelium. Genes 2024, 15, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Thiery, J.P. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions: Insights from Development. Development 2012, 139, 3471–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Mani, S.A.; Donaher, J.L.; Ramaswamy, S.; Itzykson, R.A.; Come, C.; Savagner, P.; Gitelman, I.; Richardson, A.; Weinberg, R.A. Twist, a Master Regulator of Morphogenesis, Plays an Essential Role in Tumor Metastasis. Cell 2004, 117, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivonen, S.K.; Kahari, V.M. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Signaling in Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Int J Cancer 2007, 121, 2119–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.M.; Rojas-Alexandre, M.; Hanna, R.E.; Lin, Z.P.; Ratner, E.S. Transforming Growth Factor Beta and Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition Alter Homologous Recombination Repair Gene Expression and Sensitize BRCA Wild-Type Ovarian Cancer Cells to Olaparib. Cancers 2023, 15, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.N.; Ghoneim, S.M.; Ahmed, E.R.; Salam, L.O.E.-F.A.; Saleh, S.M.A. Cadherin Switching in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Clinicopathological Study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2023, 13, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjat, D.; Kashif, M.; Roberts, C.M. Shake It Up Baby Now: The Changing Focus on TWIST1 and Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer and Other Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbichler, T.B.; Metzler, V.; Pritz, C.; Riechelmann, H.; Dudas, J. Tumor-Associated Fibroblast-Conditioned Medium Induces CDDP Resistance in HNSCC Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 7, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbichler, T.B.; Alshaimaa, A.; Maria, M.V.; Daniel, D.; Herbert, R.; Jozsef, D.; Ira-Ida, S. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Crosstalk Induces Radioresistance in HNSCC Cells. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 3641–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingruber, J.; Dudás, J.; Savic, D.; Schweigl, G.; Steinbichler, T.B.; Greier, M. do C.; Santer, M.; Carollo, S.; Trajanoski, Z.; Riechelmann, H. EMT-Related Transcription Factors and Protein Stabilization Mechanisms Involvement in Cadherin Switch of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Exp. Cell Res. 2022, 414, 113084. [CrossRef]

- Ingruber, J.; Dudas, J.; Sprung, S.; Lungu, B.; Mungenast, F. Interplay between Partial EMT and Cisplatin Resistance as the Drivers for Recurrence in HNSCC. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.; Perez, V. Specific Proteins of the Nervous System. In Physiological and biochemical aspects of nervous integration; Carlson, F., Ed.; Prentice-Hall, 1967; pp. 343–359.

- Fu, H.; Subramanian, R.R.; Masters, S.C. 14-3-3 Proteins: Structure, Function, and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000, 40, 617–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, A.; Baxter, H.; Dubois, T.; Clokie, S.; Mackie, S.; Mitchell, K.; Peden, A.; Zemlickova, E. Specificity of 14-3-3 Isoform Dimer Interactions and Phosphorylation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, L.; Chou, P.-C.; Velazquez-Torres, G.; Samudio, I.; Parreno, K.; Huang, Y.; Tseng, C.; Vu, T.; Gully, C.; Su, C.-H.; et al. The Cell Cycle Regulator 14-3-3σ Opposes and Reverses Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardino, A.K.; Smerdon, S.J.; Yaffe, M.B. Structural Determinants of 14-3-3 Binding Specificities and Regulation of Subcellular Localization of 14-3-3-Ligand Complexes: A Comparison of the X-Ray Crystal Structures of All Human 14-3-3 Isoforms. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2006, 16, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Gillies, R.J. Why Do Cancers Have High Aerobic Glycolysis? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.Y.-Y.; To, K.-F.; Leung, S.-F.; Yip, W.W.-L.; Mak, M.K.-F.; Chung, G.T.-Y.; Lo, K.-W. 14-3-3σ Expression as a Prognostic Marker in Undifferentiated Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 24, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.-J.; Wang, M.; Liu, R.-M.; Wei, H.; Chao, W.-X.; Zhang, T.; Lou, Q.; Li, X.-M.; Ma, J.; Zhu, H.; et al. Downregulation of 14-3-3σ Correlates with Multistage Carcinogenesis and Poor Prognosis of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.T.; Evron, E.; Umbricht, C.B.; Pandita, T.K.; Chan, T.A.; Hermeking, H.; Marks, J.R.; Lambers, A.R.; Futreal, P.A.; Stampfer, M.R.; et al. High Frequency of Hypermethylation at the 14-3-3 σ Locus Leads to Gene Silencing in Breast Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 6049–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawal, U.K.; Tsukinoki, K.; Sasahira, T.; Sato, F.; Mori, Y.; Muto, N.; Sugiyama, M.; Kuniyasu, H. Methylation and Intratumoural Heterogeneity of 14-3-3 Sigma in Oral Cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2007, 18, 817–824. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Liu, J.-Y.; Zhang, J.-T. 14-3-3sigma, the Double-Edged Sword of Human Cancers. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2009, 1, 326–340. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Cui, L.; Zeng, Y.; Song, W.; Gaur, U.; Yang, M. 14-3-3 Proteins Are on the Crossroads of Cancer, Aging, and Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, V.; Snow, G.B.; Vries, N. de; Cattan, A.R.; Hall, A.G.; Waal, I. van der; Braakhuis, B.J. Second Primary Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Predicted by the Glutathione S-Transferase Expression in Healthy Tissue in the Direct Vicinity of the First Tumor. Lab. Investig. a J. Tech. methods Pathol. 1995, 73, 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Bentz, B.G.; Haines, G.K.; Radosevich, J.A. Glutathione S-Transferase π in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Laryngoscope 2000, 110, 1642–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Cui, R.; Liu, Y. MicroRNA-212-3p Inhibits Paclitaxel Resistance through Regulating Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, Migration and Invasion by Targeting ZEB2 in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, C.A.; Shafer, W.G. Leukoplakia Revisited. A Clinicopathologic Study 3256 Oral Leukoplakias. Cancer 1975, 36, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jr, S.S.; Gorsky, M.; Ms, F.L. , Dds, Oral Leukoplakia and Malignant Transformation. A Follow-up Study of 257 Patients. Cancer 1984, 53, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulzico, D.; Pires, B.R.B.; Faria, P.A.S.D.; Neto, L.V.; Abdelhay, E. Twist1 Correlates With Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Markers Fibronectin and Vimentin in Adrenocortical Tumors. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, J.; Chang, T.; Wang, J.; Liang, S.; Kao, P.; Chen, L.; Yen, C.; Chen, Y.; Chang, W.; Chen, B. RNA-binding Protein-regulated Fibronectin Is Essential for EGFR-activated Metastasis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, I.; Barachini, S.; Carnicelli, V.; Galimberti, S.; Modeo, L.; Boni, R.; Sollini, M.; Erba, P.A. ED-B Fibronectin Expression Is a Marker of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Translational Oncology. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 4914–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffers, H.; Madsen, P.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Honore, B.; Andersen, A.H.; Walbum, E.; Vandekerckhove, J.; Celis, J.E. Molecular Cloning and Expression of the Transformation Sensitive Epithelial Marker Stratifin A Member of a Protein Family That Has Been Involved in the Protein Kinase C Signalling Pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 231, 982–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, H.; Tatematsu, Y.; Yatabe, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Konishi, H.; Harano, T.; Tezel, E.; Takada, M.; Takahashi, T. Frequent and Histological Type-Specific Inactivation of 14-3-3σ in Human Lung Cancers. Oncogene 2002, 21, 2418–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.-Z.; Pan, G.; Wang, J.-S.; Wen, J.-F.; Wang, K.-S.; Luo, G.-Q.; Shan, X. Reduced Stratifin Expression Can Serve As an Independent Prognostic Factor for Poor Survival in Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 2552–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).