Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Interest in advanced echocardiographic imaging methods is growing. The left atrial strain (LAS) is among the recently developed echocardiographic parameters. LAS represents an index of tissue deformation of the left atrium (LA). This parameter is an expression of the LA function. Several arrhythmias depend on the impaired LA function. LAS can be assessed with a resting echocardiogram. The evaluation of LAS during stress echocardiography represents another model for assessing LA function. The development of altered LAS during physical or pharmacological stress is a predictor of early LA disease. Our review aims to evaluate the relationship between the alterations of the LAS and the development of atrial fibrillation (AF), and the diagnostic and prognostic role of the stress echocardiogram in clinical practice.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

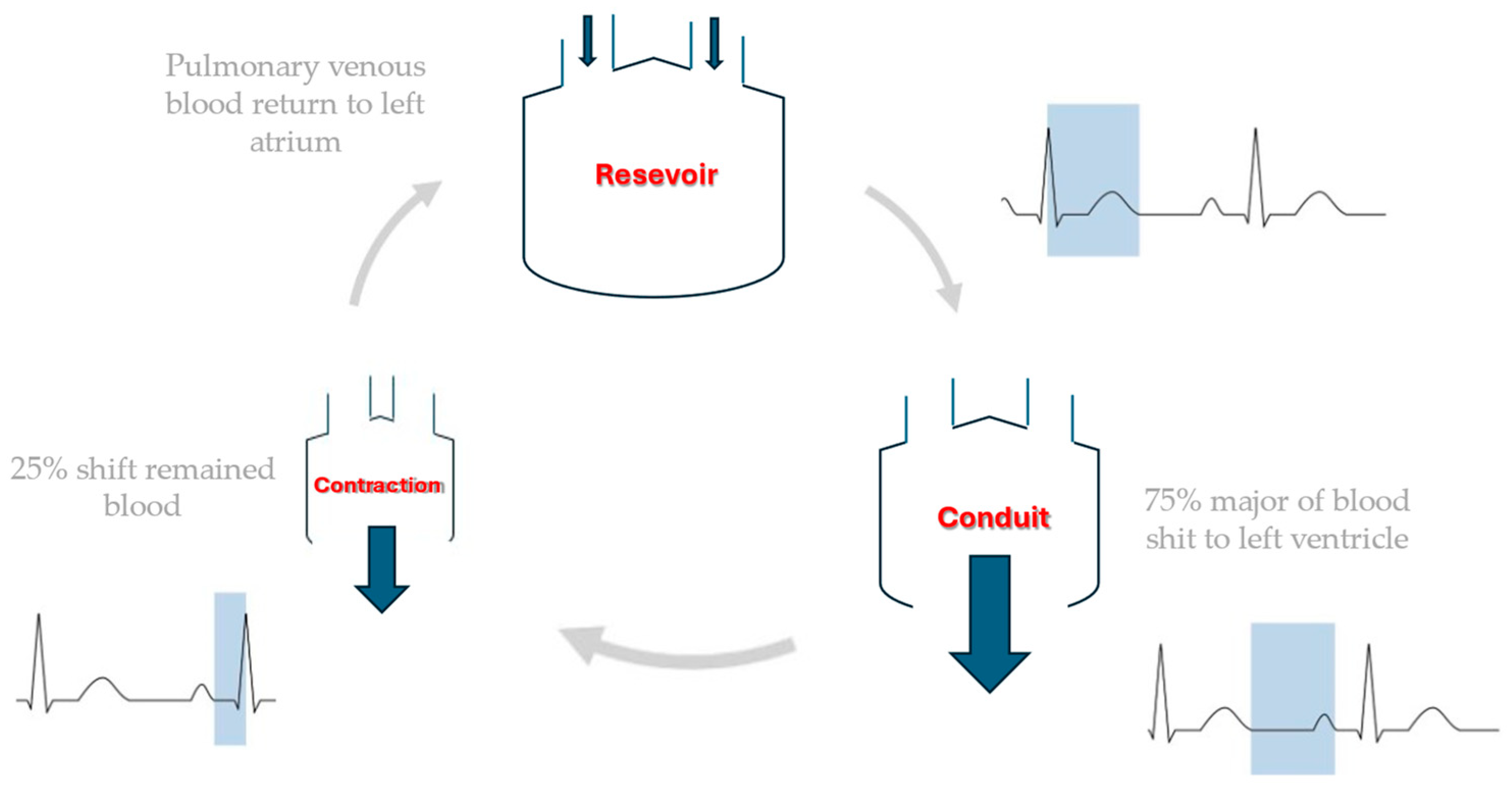

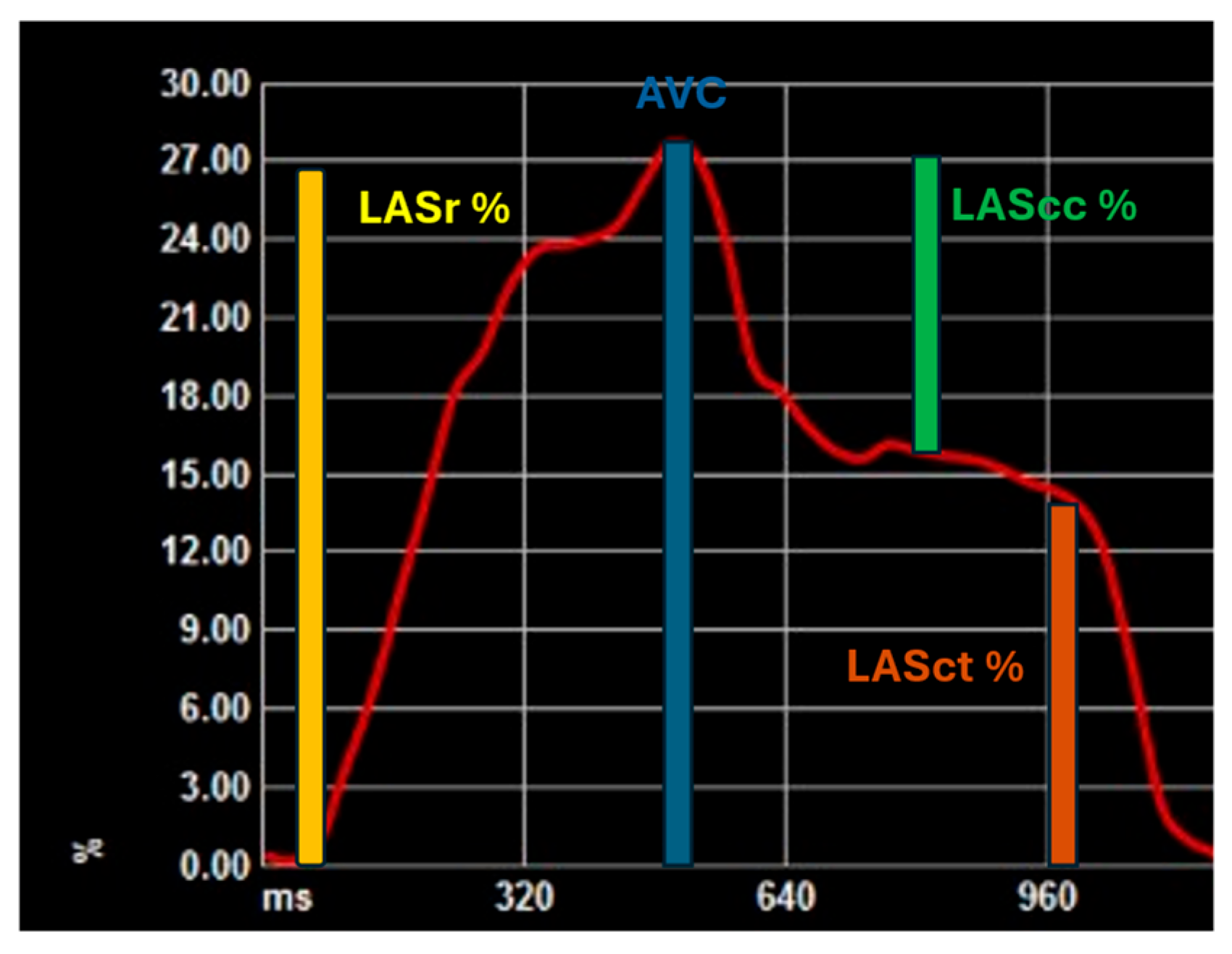

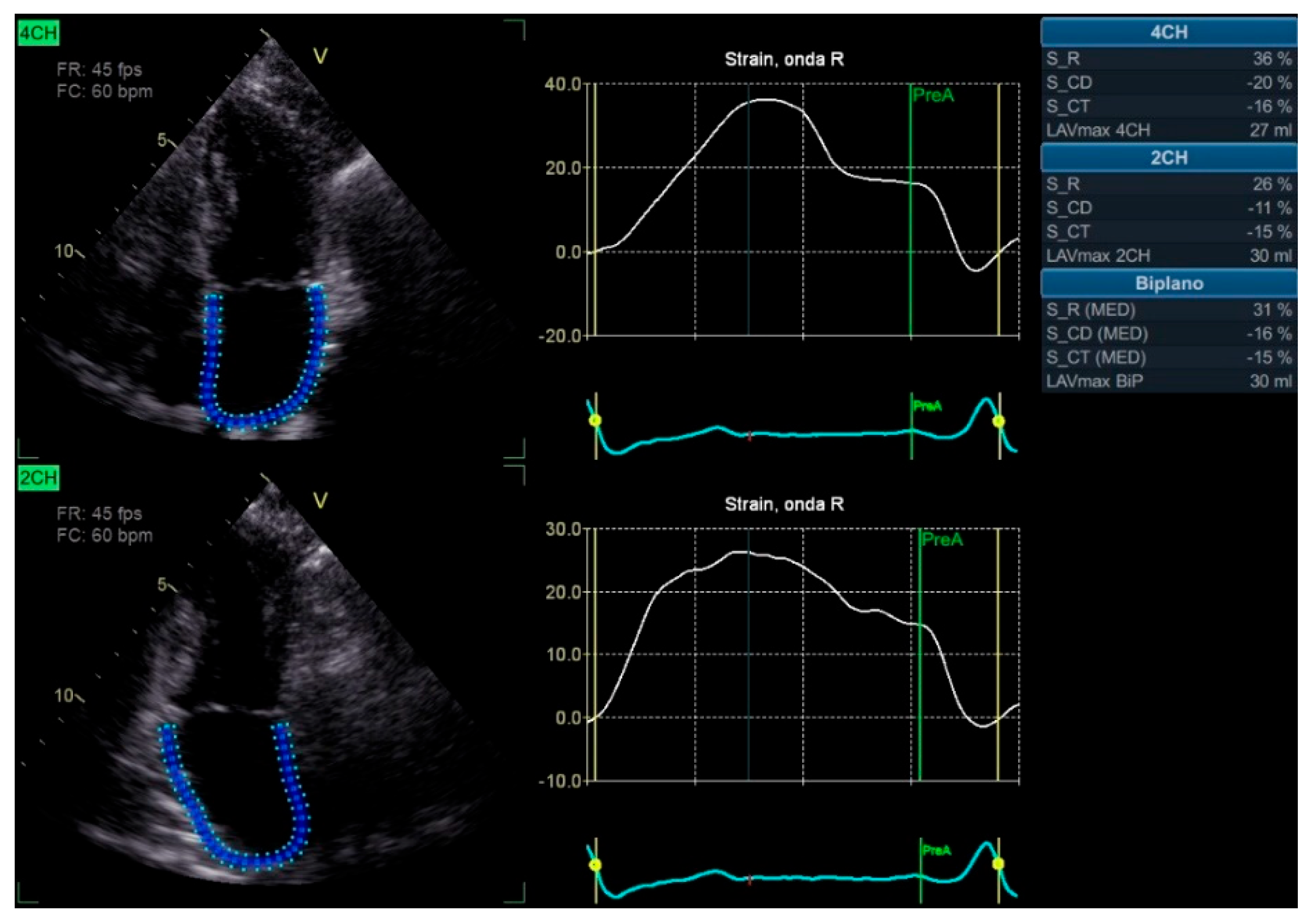

2. Speckle Tracking and Left Atrial Strain

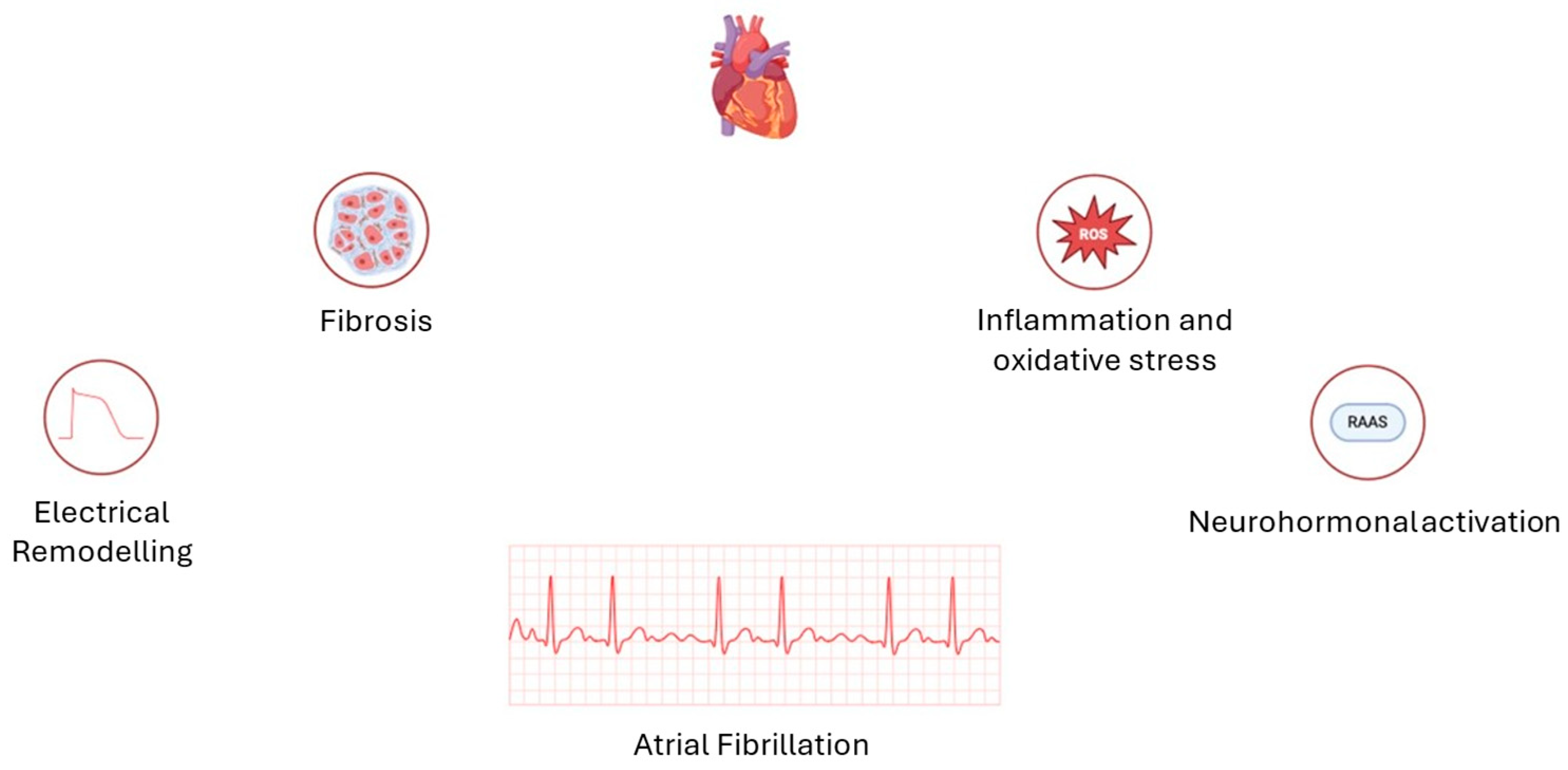

3. Atrial Fibrillation: Not Just a Question of Enlargement

4. Role of Physical Exercise in Atrial Dysfunction

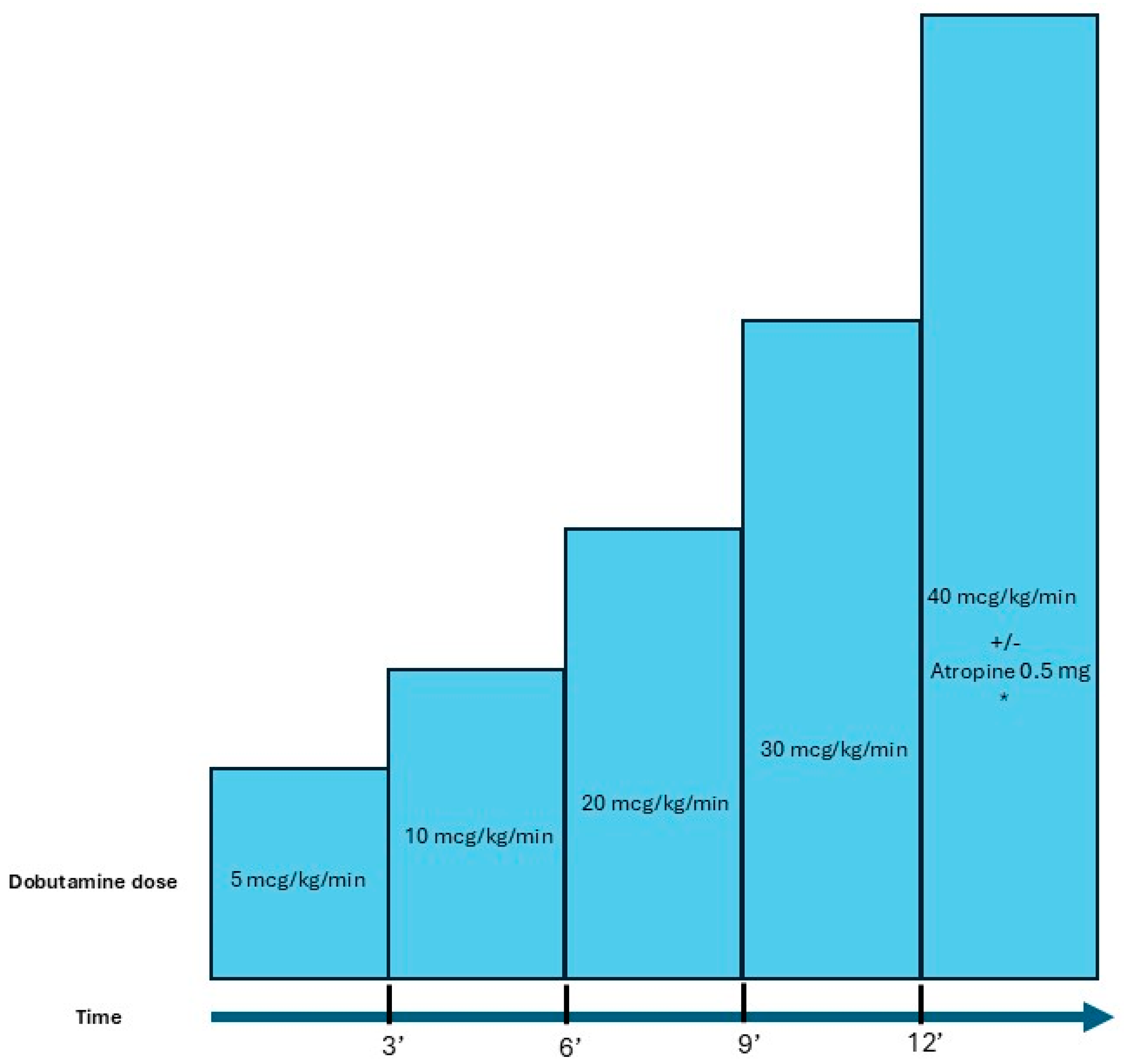

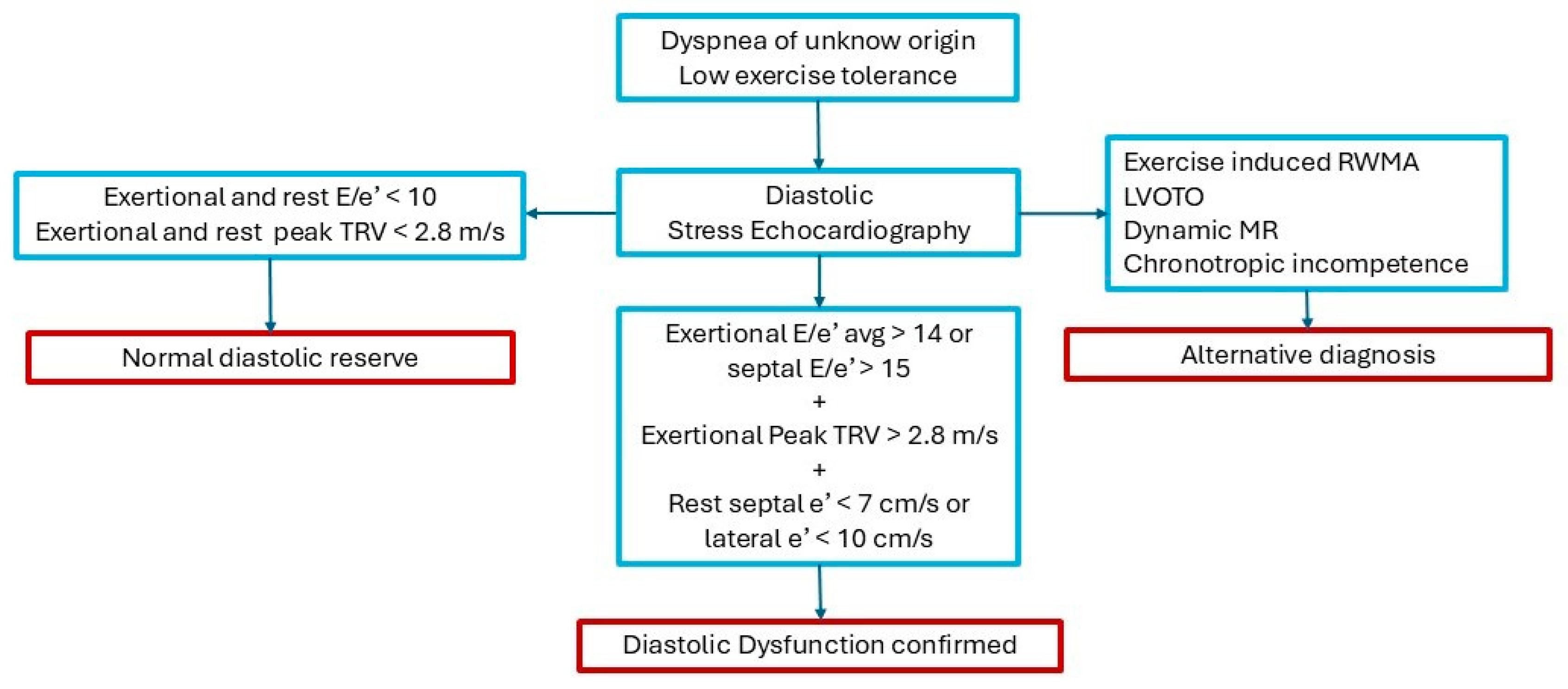

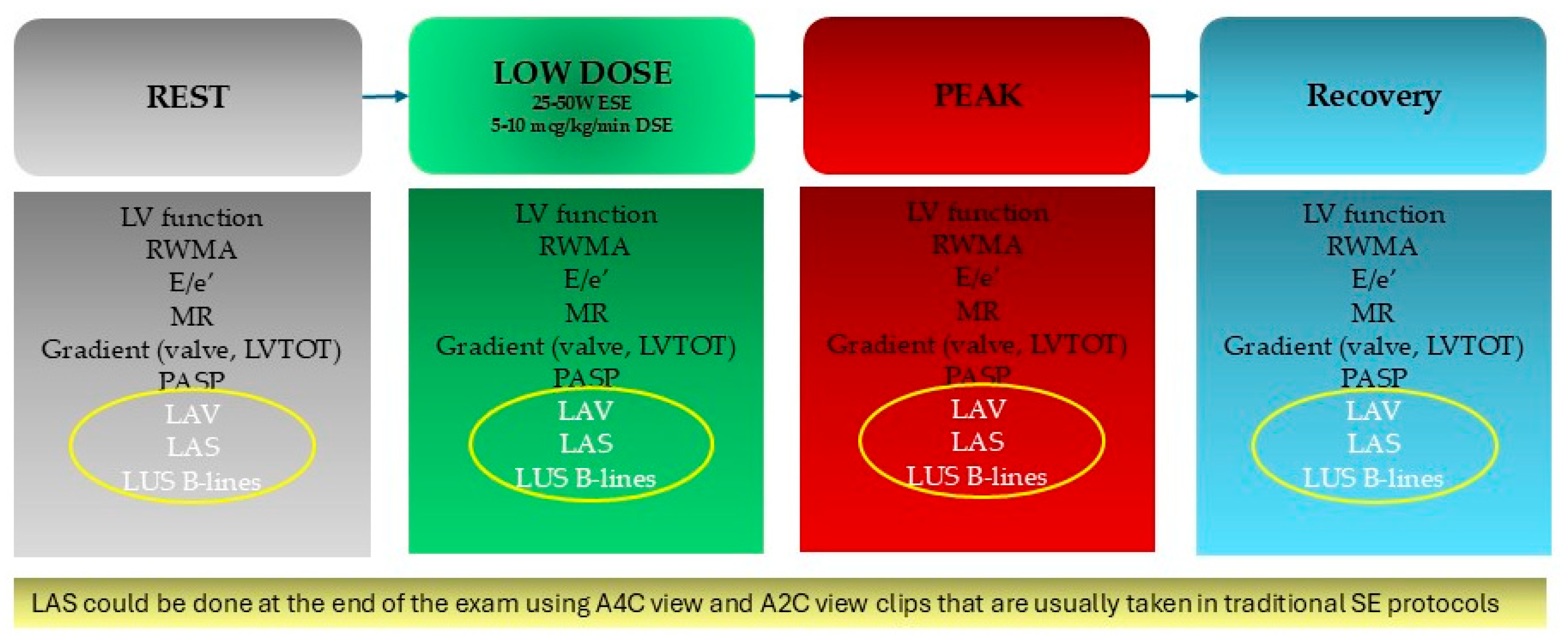

5. Role of Pharmacological and Exercise Stress Echocardiography in the Left Atrial Strain

6. What Do Guidelines on AF Say? Actual Evidence and Future Perspectives

- Arterial Hypertension: Miljković et al. in a cross-sectional study that considered 180 patients with systemic arterial hypertension, it was shown that LAS represents a predictive factor of diastolic HF in patients with systemic arterial hypertension (p < 0.0001) [61].

- HF: Barki et al. in a prospective study of 85 consecutive patients with reduced, moderately reduced, and HFpEF, demonstrated that in acute HF of any LV ejection fraction, LA dynamics are highly predictive of rehospitalization compared to nt-pro-brain natriuretic peptide (P = 0.01) [62].

- DM: Thiele et al. in a prospective, placebo-controlled exploratory study, evaluated how the use of empagliflozin 10 mg daily associated with an improvement in glycated haemoglobin was associated with a significant improvement in LA after 3 months of treatment, as assessed by an increase in LASr and LASct values (from 26.4±8.0% to 29.0±7.4%; P = 0.011 and from 10.9±5.7% to 12.5±6.0%; P = 0.008) compared to placebo [63].

- Obesity: Aga et al. showed that in a prospective study, that enrolled 77 obesity patients compared with 46 non-obese controls, there was a significantly decreasing LA function compared with non-obese individuals (LASr 32.2% ± 8.8% vs. 39.6% ± 10.8%, p < 0.001; LAScd 20.1% ± 7.5% vs. 24.9% ± 8.3%, p = 0.001; LASct 12.1% ± 3.6% vs. 14.5% ± 5.5%, p = 0.005). One year after bariatric surgery, LASr improved (32.1% ± 8.9% vs. 34.2% ± 8.7%, p = 0.048). In the multivariable linear regression analysis, body mass index (BMI) was associated with LASr, LAScd, and LASct (β = - 0.34, CI - 0.54 to - 0.13; β = - 0.22, CI - 0.38 to - 0.06; β = - 0.10, CI - 0.20 to - 0.004) [64].

- Sleep apnoea: there aren’t studies about the relationships between LAS and sleep apnoea

- Alcohol intake: Alam AB et al. in a randomized trial, have enrolled 503 participants. They showed that higher alcohol consumption (per 1 drink/day increases) was associated with lower LASct (−0.44% [95% CI, −0.75 to −0.14]) [65].

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K. V; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation Developed in Collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauriello, A.; Ascrizzi, A.; Roma, A.S.; Molinari, R.; Caturano, A.; Imbalzano, E.; D’Andrea, A.; Russo, V. Effects of Heart Failure Therapies on Atrial Fibrillation: Biological and Clinical Perspectives. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donal, E.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Galderisi, M.; Goette, A.; Shah, D.; Marwan, M.; Lederlin, M.; Mondillo, S.; Edvardsen, T.; Sitges, M.; et al. EACVI/EHRA Expert Consensus Document on the Role of Multi-Modality Imaging for the Evaluation of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016, 17, 355–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenelli, M.; Cantone, A.; Dal Passo, B.; Di Ienno, L.; Fiorio, A.; Pavasini, R.; Passarini, G.; Bertini, M.; Campo, G. Atrial Longitudinal Strain Predicts New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 16, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, F.J.; Møgelvang, R.; Jensen, G.B.; Jensen, J.S.; Biering-Sørensen, T. Relationship Between Left Atrial Functional Measures and Incident Atrial Fibrillation in the General Population. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakak, A.S.; Biering-Sørensen, S.R.; Møgelvang, R.; Modin, D.; Jensen, G.B.; Schnohr, P.; Iversen, A.Z.; Svendsen, J.H.; Jespersen, T.; Gislason, G.; et al. Usefulness of Left Atrial Strain for Predicting Incident Atrial Fibrillation and Ischaemic Stroke in the General Population. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022, 23, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, T.; Kang, P.; Hagendorff, A.; Tayal, B. The Clinical Applications of Left Atrial Strain: A Comprehensive Review. Medicina (B Aires) 2024, 60, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, M.; Pastore, M.C.; Mandoli, G.E. Left Atrial Strain: A Key Element for the Evaluation of Patients with HFpEF. Int J Cardiol 2021, 323, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandoli, G.E.; Sisti, N.; Mondillo, S.; Cameli, M. Left Atrial Strain in Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction: Have We Finally Found the Missing Piece of the Puzzle? Heart Fail Rev 2020, 25, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.J.; Arora, R.; Jalife, J. Atrial Myopathy. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2019, 4, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagatina, A.; Rivadeneira Ruiz, M.; Ciampi, Q.; Wierzbowska-Drabik, K.; Kasprzak, J.; Kalinina, E.; Begidova, I.; Peteiro, J.; Arbucci, R.; Marconi, S.; et al. Rest and Stress Left Atrial Dysfunction in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prota, C.; Cortigiani, L.; Campagnano, E.; Wierzbowska-Drabik, K.; Kasprzak, J.; Colonna, P.; Merli, E.; Manganelli, F.; Gaibazzi, N.; D’Andrea, A.; et al. Left Atrium Stress Echocardiography: Correlation between Left Atrial Volume, Function, and B-Lines at Rest and during Stress. Exploration of Cardiology 2024, 2, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, P.; Pellikka, P.A.; Budts, W.; Chaudhry, F.A.; Donal, E.; Dulgheru, R.; Edvardsen, T.; Garbi, M.; Ha, J.W.; Kane, G.C.; et al. The Clinical Use of Stress Echocardiography in Non-Ischaemic Heart Disease: Recommendations from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2017, 30, 101–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, B.A.; Beladan, C.C.; Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A. How to Assess Left Ventricular Filling Pressures by Echocardiography in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022, 23, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschöpe, C.; de Boer, R.A.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to Diagnose Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: The HFA–PEFF Diagnostic Algorithm: A Consensus Recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abawi, D.; Rinaldi, T.; Faragli, A.; Pieske, B.; Morris, D.A.; Kelle, S.; Tschöpe, C.; Zito, C.; Alogna, A. The Non-Invasive Assessment of Myocardial Work by Pressure-Strain Analysis: Clinical Applications. Heart Fail Rev 2022, 27, 1261–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, L.; Levett, K.; Boyd, A.; Leung, D.Y.C.; Schiller, N.B.; Ross, D.L. Compensatory Changes in Atrial Volumes with Normal Aging: Is Atrial Enlargement Inevitable? J Am Coll Cardiol 2002, 40, 1630–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Marwick, T.H.; Popescu, B.A.; Donal, E.; Badano, L.P. Left Atrial Structure and Function, and Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 73, 1961–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, N.; Bismee, N.N.; Abbas, M.T.; Scalia, I.G.; Pereyra, M.; Ali, N.B.; Esfahani, S.A.; Awad, K.; Farina, J.M.; Ayoub, C.; et al. Left Atrial Strain: State of the Art and Clinical Implications. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2024, Vol. 14, Page 1093 2024, 14, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.J.; Teixeira, R.; Gonçalves, L.; Gersh, B.J. Left Atrial Mechanics: Echocardiographic Assessment and Clinical Implications. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2014, 27, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathan, F.; D’Elia, N.; Nolan, M.T.; Marwick, T.H.; Negishi, K. Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017, 30, 59–70.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.X.; Yang, W.; Yin, W.S.; Peng, K.X.; Pan, Y.L.; Chen, W.W.; Du, B.B.; He, Y.Q.; Yang, P. Clinical Utility of Left Atrial Strain in Predicting Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence after Catheter Ablation: An up-to-Date Review. World J Clin Cases 2022, 10, 8063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wałek, P.; Roskal-Wałek, J.; Dłubis, P.; Wożakowska-Kapłon, B. Echocardiographic Evaluation of Atrial Remodelling for the Prognosis of Maintaining Sinus Rhythm after Electrical Cardioversion in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, Q.; Ma, S. Left Atrial Fibrosis in Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanisms, Clinical Evaluation and Management. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Tang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y. Evaluation of Left Atrial and Ventricular Remodeling in Atrial Fibrillation Subtype by Using Speckle Tracking Echocardiography. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1208577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.C.H.; Ferkh, A.; Boyd, A.; Thomas, L. Left Atrial Function: Evaluation by Strain Analysis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carluccio, E.; Cameli, M.; Rossi, A.; Dini, F.L.; Biagioli, P.; Mengoni, A.; Jacoangeli, F.; Mandoli, G.E.; Pastore, M.C.; Maffeis, C.; et al. Left Atrial Strain in the Assessment of Diastolic Function in Heart Failure: A Machine Learning Approach. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 16, E014605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, P.; Jorge, C.A.C.; Zerlotto, D.S.; Moraes, F.C.A. De; Donadon, I.B.; Souza, M.E.C.; Aziri, B.; Serpa, F. PROGNOSTIC VALUE OF LEFT ATRIAL STRAIN FOR THE INCIDENCE OF ATRIAL FIBRILLATION: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS OF MULTIVARIABLE ADJUSTED ANALYSES. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 83, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, L.; Ur Rehman Iqbal, S.; Wittmer, S.; Thalmann, G.; Madaffari, A.; Kozhuharov, N.; Galuszka, O.; Küffer, T.; Gräni, C.; Brugger, N.; et al. Impact of Atrial Fibrillation Phenotype and Left Atrial Volume on Outcome after Pulmonary Vein Isolation. Europace 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, R.M.; Demirkol, S.; Buakhamsri, A.; Greenberg, N.; Popović, Z.B.; Thomas, J.D.; Klein, A.L. Left Atrial Strain Measured by Two-Dimensional Speckle Tracking Represents a New Tool to Evaluate Left Atrial Function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010, 23, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; He, L.; Gao, L.; Lin, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, Y. Assessment of Left Atrial Structure and Function by Echocardiography in Atrial Fibrillation. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauriello, A.; Correra, A.; Molinari, R.; Del Vecchio, G.E.; Tessitore, V.; D’Andrea, A.; Russo, V. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Atrial Fibrillation: The Need for a Strong Pharmacological Approach. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattel, S.; Burstein, B.; Dobrev, D. Atrial Remodeling and Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanisms and Implications. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2008, 1, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzeshka, M.S.; Shantsila, A.; Shantsila, E.; Lip, G.Y.H. Atrial Fibrillation and Hypertension. Hypertension 2017, 70, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneke, K.; Molina, C.E. Molecular Basis of Atrial Fibrillation Initiation and Maintenance. Hearts 2021, 2, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Peng, L.; Ghista, D.N.; Wong, K.K.L. Left Atrial Remodeling Mechanisms Associated with Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovasc Eng Technol 2021, 12, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, R.; Faddis, M.N.; Cuculich, P.S.; Rudy, Y. Mechanisms of Persistent Atrial Fibrillation and Recurrences within 12 Months Post-Ablation: Non-Invasive Mapping with Electrocardiographic Imaging. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 1052195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corban, M.T.; Toya, T.; Ahmad, A.; Lerman, L.O.; Lee, H.C.; Lerman, A. Atrial Fibrillation and Endothelial Dysfunction: A Potential Link? Mayo Clin Proc 2021, 96, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goette, A.; Kalman, J.M.; Aguinaga, L.; Akar, J.; Cabrera, J.A.; Chen, S.A.; Chugh, S.S.; Corradi, D.; D’Avila, A.; Dobrev, D.; et al. EHRA/HRS/APHRS/SOLAECE Expert Consensus on Atrial Cardiomyopathies: Definition, Characterization, and Clinical Implication. EP Europace 2016, 18, 1455–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Băghină, R.M.; Crișan, S.; Luca, S.; Pătru, O.; Lazăr, M.A.; Văcărescu, C.; Negru, A.G.; Luca, C.T.; Gaiță, D. Association between Inflammation and New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Acute Coronary Syndromes. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, Vol. 13, Page 5088 2024, 13, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, A.; Formisano, T.; Riegler, L.; Scarafile, R.; America, R.; Martone, F.; di Maio, M.; Russo, M.G.; Bossone, E.; Galderisi, M.; et al. Acute and Chronic Response to Exercise in Athletes: The “Supernormal Heart.” In; 2017; pp. 21–41.

- Pelliccia, A.; Maron, B.J.; Di Paolo, F.M.; Biffi, A.; Quattrini, F.M.; Pisicchio, C.; Roselli, A.; Caselli, S.; Culasso, F. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Left Atrial Remodeling in Competitive Athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005, 46, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, A.; Riegler, L.; Cocchia, R.; Scarafile, R.; Salerno, G.; Gravino, R.; Golia, E.; Vriz, O.; Citro, R.; Limongelli, G.; et al. Left Atrial Volume Index in Highly Trained Athletes. Am Heart J 2010, 159, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, A.; De Corato, G.; Scarafile, R.; Romano, S.; Reigler, L.; Mita, C.; Allocca, F.; Limongelli, G.; Gigantino, G.; Liccardo, B.; et al. Left Atrial Myocardial Function in Either Physiological or Pathological Left Ventricular Hypertrophy: A Two-Dimensional Speckle Strain Study. Br J Sports Med 2008, 42, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, A.; Mele, D.; Palermi, S.; Rizzo, M.; Campana, M.; Di Giannuario, G.; Gimelli, A.; Khoury, G.; Moreo, A.; a nome dell’Area Cardioimaging dell’Associazione Nazionale Medici Cardiologi Ospedalieri (ANMCO). [Grey Zones in Cardiovascular Adaptations to Physical Exercise: How to Navigate in the Echocardiographic Evaluation of the Athlete’s Heart]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2020, 21, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellikka, P.A.; Arruda-Olson, A.; Chaudhry, F.A.; Chen, M.H.; Marshall, J.E.; Porter, T.R.; Sawada, S.G. Guidelines for Performance, Interpretation, and Application of Stress Echocardiography in Ischemic Heart Disease: From the American Society of Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2020, 33, 1–41.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicari, R.; Cortigiani, L. The Clinical Use of Stress Echocardiography in Ischemic Heart Disease. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2017, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, A.; Marrazzo, G.; Del Vecchio, G.E.; Ascrizzi, A.; Roma, A.S.; Correra, A.; Sabatella, F.; Gioia, R.; Desiderio, A.; Russo, V.; et al. Echocardiography in Cardiac Arrest: Incremental Diagnostic and Prognostic Role during Resuscitation Care. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kane, G.C.; Luong, C.L.; Oh, J.K. Echocardiographic Diastolic Stress Testing: What Does It Add? Curr Cardiol Rep 2019, 21, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Tschöpe, C.; de Boer, R.A.; Fraser, A.G.; Anker, S.D.; Donal, E.; Edelmann, F.; Fu, M.; Guazzi, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. How to Diagnose Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: The HFA–PEFF Diagnostic Algorithm: A Consensus Recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 3297–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchier, L.; Bisson, A.; Bodin, A. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Atrial Fibrillation: Recent Advances and Open Questions. BMC Med 2023, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.-W.; Andersen, O.S.; Smiseth, O.A. Diastolic Stress Test. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020, 13, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzas-Mosquera, A.; Peteiro, J.; Broullon, F.J.; Alvarez-Garcia, N.; Mosquera, V.X.; Rodriguez-Vilela, A.; Casas, S.; Castro-Beiras, A. Prognostic Value of Exercise Echocardiography in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. European Journal of Echocardiography 2010, 11, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, T.; Amano, M.; Moriuchi, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Nishimura, H.; Tamai, Y.; Mizumoto, A.; Koda, A.; Demura, Y.; Jo, Y.; et al. Usefulness of Exercise Stress Echocardiography for Predicting Cardiovascular Events and Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.-F.; Huang, P.-S.; Chen, Z.-W.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lan, C.-W.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lin, L.-Y.; Wu, C.-K. Post-Exercise Left Atrial Conduit Strain Predicted Hemodynamic Change in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Eur Radiol 2023, 34, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, C.; Yin, L. Assessment the Predictive Value of Left Atrial Strain (LAS) on Exercise Tolerance in HCM Patients with E/e’ between 8 and 14 by Two-Dimensional Speckle Tracking and Treadmill Stress Echocardiography. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2023, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhaus, S.J.; Schulz, A.; Lange, T.; Schmidt-Schweda, L.S.; Hellenkamp, K.; Evertz, R.; Kowallick, J.T.; Kutty, S.; Hasenfuß, G.; Schuster, A. Prognostic and Diagnostic Implications of Impaired Rest and Exercise-Stress Left Atrial Compliance in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Insights from the HFpEF Stress Trial. Int J Cardiol 2024, 404, 131949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Kagami, K.; Shina, T.; Sorimachi, H.; Yuasa, N.; Saito, Y.; Naito, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kato, T.; Wada, N.; et al. Diagnostic Value of Reduced Left Atrial Compliance during Ergometry Exercise in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2023, 25, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picano, E.; Ciampi, Q.; Arbucci, R.; Cortigiani, L.; Zagatina, A.; Celutkiene, J.; Bartolacelli, Y.; Kane, G.C.; Lowenstein, J.; Pellikka, P. Stress Echo 2030: The New ABCDE Protocol Defining the Future of Cardiac Imaging. European Heart Journal Supplements 2023, 25, C63–C67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K. V; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation Developed in Collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljković, T.; Ilić, A.; Milovančev, A.; Bjelobrk, M.; Stefanović, M.; Stojšić-Milosavljević, A.; Tadić, S.; Golubović, M.; Popov, T.; Petrović, M. Left Atrial Strain as a Predictor of Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction in Patients with Arterial Hypertension. Medicina (B Aires) 2022, 58, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barki, M.; Losito, M.; Caracciolo, M.M.; Sugimoto, T.; Rovida, M.; Viva, T.; Arosio, R.; Alfonzetti, E.; Bandera, F.; Moroni, A.; et al. Left Atrial Strain in Acute Heart Failure: Clinical and Prognostic Insights. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2024, 25, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, K.; Rau, M.; Grebe, J.; Korbinian Hartmann, N.-U.; Altiok, E.; Böhm, M.; Keszei, A.P.; Marx, N.; Lehrke, M. Empagliflozin Improves Left Atrial Strain in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Data From a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aga, Y.S.; Kroon, D.; Snelder, S.M.; Biter, L.U.; de Groot-de Laat, L.E.; Zijlstra, F.; Brugts, J.J.; van Dalen, B.M. Decreased Left Atrial Function in Obesity Patients without Known Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2022, 39, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A.B.; Toledo-Atucha, E.; Romaguera, D.; Alonso-Gómez, A.M.; Martínez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Tojal-Sierra, L.; Mora, M.N.; Mas-Llado, C.; Li, L.; Gonzalez-Casanova, I.; et al. Associations of Alcohol Consumption With Left Atrial Morphology and Function in a Population at High Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannino, A.; Delgado, V. Left Atrial Reservoir Strain and Machine Learning: Augmenting Clinical Care in Heart Failure Patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Design | Population | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zagatina et al. [11] | Multicenter prospective observational study | 3042 pts undergone SE for CCS (group 1: no AF; group 2: paroxysmal AF; group 3: permanent AF) |

LAS during SE performed in 16% of cases; Peak-LASr group 3 < LASr group 2 < LASr group 3 (Group 1 = 26.9 ± 10.1, Group 2 = 23.8 ± 11.0 Group 3 = 10.7 ± 8.1%, p < 0.001) |

| Prota et al. [12] | Single centre prospective observational study | 252 pts undergoing pharmacological SE for CCS | LAS during SE performed in 95.5% of cases; Inverse linear correlation between peak-LASr and LAVi (r = –0.289, p < 0.001); Inverse linear correlation between LUS B-lines peak- LASr (r = –0.234, p < 0.001); Inverse correlation between peak-LASr and NYHA class (r=-0.263, p < 0.001 respectively) |

| Yoshii et al. [54] | A single center retrospective study | 74 HCM pts with EF > 50% undergoing ESE | Peak-LASr associated with new-onset AF (HR 1.08, 95 % CI 1.01–1.18, p = 0.027); Peak-LASr ≤15.5 % predicted with a sensitivity of 55.6 % and specificity of 91.8 % (AUC 0.71) new-onset AF; Lower peak-LASr correlated to low exercise tolerance (< 75W) (31.2±15.3 vs 24.7±13.6 %, p=0.033). |

| Cheng et al. [55] | Single centre prospective observational study | 100 pts with dyspnea (74 HFpEF and 26 NCD) |

Inverse correlation between peak-LAScd and PCWP (r = − 0.659; p < 0.001) and ΔPCWP (r = − 0.707, p < 0.001); Peak-LAScd < 14.25% detect HFpEF with 64% sensitivity and 68% specificity (AUC 0.69) |

| Su et al. [56] | A single center retrospective study | 70 HCM pts + 30 control (HCM1 group E/e' > 14; HCM2 group E/e' 8-14) |

HCM group had significantly lower peak LASr, LAScd and LASct and lower LAS reserve during stress compared to controls (p < 0.05); HCM2 had a better peak-LASr (p =0.001), peak-LAScd (p= 0.008) and ΔLASct% (p=0.028) compared to the HCM1 group. The HCM2 group had higher exercise tolerance (METS) than the HCM1 group and METS was positively correlated with LAS parameters |

| Backhaus et al. [57] | Single centre prospective observational study | 75 pts with exertion dyspnea and rest E/e’ >8 undergoing ESE | LASr / E/e’ ratio during stress decreased in HFpEF patients diagnosed invasively (1.4 vs 2.6, p = 0.004) compared to individuals with NCD. LASr / E/e’ ratio during stress decreased in HFpEF patients diagnosed non-invasively (1.3 vs 2.2, p = 0.022) |

| Harada et al. [58] | A single center retrospective study | 487 pts undergone ESE (225 HFpEF pts + 262 controls with NCD) | LAS during SE performed in 89% of cases. Exercise LAS and LASr / E/e’ ratio lower in HFpEF compared to NCD; Exercise LASr / E/e’ ratio and peak-LASr had the strongest diagnostic ability to differentiate HFpEF from NCD (AUC 0.87, 0.83–0.90, p<0.0001 and AUC 0.82, 0.67–0.91, p<0.0001, respectively) ; Exercise LASr / E/e’ ratio < 2.2%, 81% sensitivity and 85% specificity for HFpEF diagnosis. |

| Author | Sample Size | LAS Parameters During SE and Abnormal Values |

| Zagatina et al. [11] | 3042 pts | Peak-LASr < 24% |

| Prota et al. [12] | 252 pts | Peak-LASr ≤ 24% |

| Yoshii et al. [54] | 74 pts | Peak-LASr ≤15.5 % |

| Cheng et al. [55] | 100 pts | Peak-LAScd <14.25% |

| Harada et al. [58] | 487 pts | Peak-LASr < 31 % (protocol 1) or < 33.4% (protocol 2) Exercise LASr / E/e’ ratio < 2.2% (protocol 1) or < 2% (protocol 2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).