1. Introduction

Globally, after mosquitoes, ticks are the second most common agents that transmit human vector-borne diseases, of which the most common tick-borne disease (TBD) is Lyme disease (LD) ((CDC), n.d.; Dong et al., 2022). Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bb s.l.), the causative agent of LD, is the most frequently reported tickborne illness (TBI) globally. Dong et al. indicated varying levels of seroprevalence for Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb) in different regions, for example, 20.7% in Central Europe, 15.9% in Eastern Asia, 13.5% in Western Europe, 10.4% in Eastern Europe, 5.3% in Oceania, 3.0% in Southern Asia, and 2.0% in the Caribbean (Dong et al., 2022). However, these numbers mainly come from areas where LD is common and may not reflect the global situation (Dong et al., 2022). Data from non-endemic regions, like Africa, are often missing, making it hard to estimate a global rate (Dong et al., 2022). For 2022, the state and local health departments in the United States reported 62,551 LD cases to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Kugeler et al., 2024)These numbers may be a gross underestimate, as suggested by other studies. For example, for LD alone, the actual number is between 3- and 12-fold higher than reported (Kugeler et al., 2021; Schwartz et al., 2021). The existence of endemic Lyme disease (LD) in Australia has not been proven, and there is uncertainty concerning the cause of “Lyme-like” disease (LLD) in Australia. This has been the subject of debate for over 30 years. Spirochaetes of the Bb complex, which includes those that cause LD, have been identified in Australian patients and ticks (Wills and Barry, 1991; Barry et al., 1994; Hudson et al., 1994, 1998; Catherine, 1995), but conclusive evidence has not been provided according to other studies (Russell et al., 1994; Chalada et al., 2016; Collignon et al., 2016; Gofton et al., 2022). Nevertheless, Australian patients, some of whom have not travelled overseas (Barry et al., 1994; Hudson et al., 1998), have been identified with LLD and have symptoms consistent with LD (Stewart et al., 1982; Lawrence et al., 1986; McCrossin, 1986; N, 1987; Maud and Berk, 2013; Brown, 2018; Shah et al., 2019).

The incidence of LLD is likely underestimated in Australia due to a lack of public health surveillance programs for TBD, including LLD. Despite many reports of patients suffering severe illness following a tick bite, many such case reports are dismissed (Australia, 2016; Brown, 2018). In 2018, the Australian Government proposed the diagnostic label ‘Debilitating Symptom Complexes Attributed to Ticks’ (DSCATT) for a chronic syndrome of unclear etiology associated with tick bites (Haisman-Welsh and Marshall, 2020). However, to date, the number of cases of TBDs remains unclear. The evidence that describes the relationship between tick bites and DSCATT in Australia is limited to only one publication with a sample size of 29 patients (Schnall et al., 2022). Anecdotal reports from general practitioners, local governments, and concerned community members indicate that TBI is a significant public health issue (Australia, 2016).

Three human TBDs are universally recognized as endemic in Australia: Q fever (Coxiella burnetii) and spotted fevers caused by Rickettsia australis and Rickettsia honei (Graves and Stenos, 2017). Additionally, there is concern about unidentified TBIs in Australia (i.e., not caused by Rickettsia and Coxiella), such that a broader range of testing is required for other microbial causes of TBI (Graves and Stenos, 2017).

For LD, the diagnosis of LLD may still be a clinical diagnosis. A history of tick exposure (or travel to an endemic area) and secondary or tertiary manifestations may suggest LD. However, the differential diagnosis includes aseptic meningitis, Bell’s palsy, peripheral neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, acute and chronic arthritis (Sanchez, 2015), and, in Australia, arbovirus infections such as epidemic polyarthritis (Ross River), and well-known TBD such as tick typhus (spotted fever) (Sexton et al., 1990; Graves et al., 1991; PINN and SOWDEN, 1998; Harley et al., 2001; Fergie et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2017). Queensland tick typhus (QTT), the classic Australian spotted fever caused by Rickettsia australis, is a common illness in the Northern Beaches Council area following a tick bite, causing fever, rash, and characteristic skin lesions (often vesicular or even pustular), usually with an eschar at the bite site. QTT is occasionally fatal, but early recognition and implementation of appropriate antibiotic treatment usually leads to rapid resolution of illness. A confirmed diagnosis of QTT is based on immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) and specific R. australis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. A confirmed diagnosis of LD is made by either PCR or culture of the causative spirochaete from patient samples, mainly skin biopsies. Culture, however, is impractical for routine diagnosis, PCR is not widely available, and few patients undergo skin biopsy. Accordingly, the diagnosis must be confirmed by measuring the antibody response to the spirochaete, usually by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). These tests were originally notorious for their lack of both sensitivity and specificity, so western blot (WB) tests were recommended for confirmatory testing, providing a higher degree of specificity. A two-step ELISA approach has been shown to perform as well as the ELISA/IFA and WB approach (Branda et al., 2017). The most recent development in the laboratory diagnosis of early LD has been the use of PCR, which detects the presence of Bb s.l. in samples such as skin biopsies, synovial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood, with skin biopsy and synovial fluid being the usual samples that are submitted for PCR. An Australian study investigated the variation between Australian laboratories performing serology for LD and reported that conflicting results existed between testing laboratories and that such discrepancies caused patients to question the validity of the results (Best et al., 2019). The authors aimed to find an agreement between assays commonly used for Bb s.l. serology tests. They concluded that there was discordance in results between laboratories that was more likely due to operational and performance variations in assay testing algorithms. In the known seronegative population, the specificities of immunoassays ranged from 97.7%-99.7%. In Australia, with its low prevalence of seropositivity, this would equate to a positive predictive value (PPV) of less than 4% (Best et al., 2019).

This study's main objective was to evaluate the performance and reliability of TICKPLEX® at Tezted Ltd. in Finland and the Royal North Shore Hospital in Australia, focusing on the concordance of results between these laboratories. The focus was on the results from pre-characterized reference samples from Australian patients with and without LLD, compared with reference serum samples from SeraCare Life Sciences Inc. and the Plasma Services Group.

2. Materials and Methods

Within this study, two independent laboratories, Tezted Ltd. (FIN) and Royal North Shore Hospital, New South Wales Pathology [North Sydney, Australia (AUS)], used the multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay TICKPLEX® (Garg et al., 2021) to evaluate the performance of the test in Australia for the first time under Research Use Only (RUO) conditions using the ODI. TICKPLEX® has been validated by the manufacturer to determine TBD-specific antibody responses (IgG and IgM) in human sera or plasma with or without glycerol.

TICKPLEX® PLUS (hereon referred to as TICKPLEX® or Index test or Index Assay) is a CE-IVD registered product (European In-Vitro Diagnostic Devices Directive (98/79/EC) and legacy compliant 2017/746 IVDR) manufactured under ISO 13485:2016 accredited facility in Tezted Ltd, Jyväskylä, Finland. For this evaluation, we used the TICKPLEX® PLUS FOR RESEARCH USE ONLY Instructions (Version 17). This Index Assay was chosen because it can simultaneously test for IgM and IgG antibodies to multiple microbes (Garg et al., 2021). If one were to replicate all the testing of what TICKPLEX® can do, 30 tests would be needed instead of one. The Index Assay is an indirect ELISA that measures the immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) responses in human serum samples against Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species in spirochete and persistent forms, coinfections, and opportunistic microbes associated with a tick bite. Specifically, the index test includes antigens from Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia garinii in spirochete and persistent forms, Babesia microti, Bartonella henselae, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Rickettsia akari, Coxsackievirus, Epstein–Barr virus, Human Parvovirus B19, Mycoplasma fermentans, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

2.1. Material Used

Fifty-three serum samples were analyzed using the Index Assay to assess exposure to tick-borne disease-related pathogens. Of these samples, 33 were Lyme reference sera obtained from SeraCare Life Sciences Inc. (USA) subsidiary in France and the Plasma Services Group (USA), while 20 were randomly selected well-characterized reference sera samples from Australia (

Table 1). To ensure unbiased analysis, the previous diagnoses of all patients were blinded for operators in both laboratories, and operators followed the instructions for use (IFU) for the Index Assay. Results from both laboratories were shared once the tests were completed.

To establish an inter-laboratory agreement, 28 out of the 53 serum samples had enough volume to be shared between Tezted Ltd in Finland, and the Royal North Shore Hospital (New South Wales Health Pathology) in Sydney, Australia (

Table 1). Among these shared samples, 22 of the 28, had been tested for Lyme like disease previously. The results were not known to the researchers, allowing for an unbiased assessment of agreement between the combined IgM and IgG Index Assay results in both sites. Out of the 53 reference samples, the remaining 25 were analyzed solely at Tezted Ltd.

It Is important to note that the serum samples shared by the Australian lab were not diluted in 30% glycerol. In contrast, the samples shared by Tezted Ltd. were diluted to preserve sample shelf-life quality. The IFU was adjusted accordingly by the manufacturer to account for glycerol dilution. The samples in 30% glycerol were further diluted at a 1:133 ratio in sample buffer, while undiluted sera samples were diluted at 1:200 (

Table S1).

The raw optical density index (ODI) values from the serum samples at 450 nm were normalized to determine the antibody response with cutoff ODI values for each antigen. Specifically, all pathogen negative, borderline, and positive responses were defined based on optical density values of lower than 0.90, within the range of 0.91 to 0.99, and exceeding 1.00, respectively. This normalization process ensured consistent interpretation of the test results across all samples, enabling comparison of immune responses to different tick-borne pathogens.

2.2. Internal and External Controls

The Index Assay includes internal positive (POS), negative (NEG), and coefficient of determination (R2) plate controls for both IgM and IgG. These controls are essential for verifying the accuracy of the test plate’s performance. The plate validity criteria for the IgM and IgG plate controls are as follows: a positive optical density (OD) reading should be above 1, while a negative OD reading should be below 0.5. Additionally, the R2 value should be greater than 0.75. An R-squared (R2), the coefficient of determination, was used to measure the interlaboratory variation between datasets presented by the two laboratories and how well a statistical model predicts a level of confidence in the results. In the case of paired data presented in this analysis, the R2 measures the proportion of variance shared by the two variables and ranges from 0 to 1. These criteria ensure the plate’s reliability and the validity of the test results.

The study incorporated external pre-characterized controls, consisting of reference serum samples obtained from the Australian laboratory, SeraCare Life Sciences Inc. (USA) subsidiary in France and the Plasma Services Group (USA). The Australian reference samples (N=20), were randomly selected characterized undiluted serum samples from Australia (N=17) which also included undiluted samples from the Plasma Services Group (PSG, N=3) (

Table 1). The Plasma Services Group (PSG) samples from the USA included symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals tested for LD. The PSG samples were provided with reference results from three different assays: the EUROIMMUN Lyme Western Blot for IgG and IgM, EUROIMMUN ELISA IgG and IgM, and Zeus Scientific ELISA IgG, IgM, and VLSE IgG/M. These assays target specific Lyme-related bands and antigens for accurate diagnosis. Similarly, serum samples from SeraCare Life Sciences Inc were provided with reference results from eight different assays: DiaSorin LIAISON® Borrelia burgdorferi Lyme IgM/IgG assay, Trinity Biotech Captia

™ Borrelia burgdorferi IgG/IgM ELISA, BioMerieux VIDAS

® Lyme IgM II assay, MarDx B. burgdorferi Disease EIA IgM Test System, BioMerieux VIDAS

® Lyme IgG II assay, MarDx B. burgdorferi Disease EIA IgG Test System, MarDx B. burgdorferi (IgM) MarBlot Strip Test System, and MarDx B. burgdorferi (IgG) MarBlot Strip Test System.

The AccuSet™ Lyme Performance Panel 0845-0169 from SeraCare Life Sciences Inc. was also utilized. This panel comprised 15 undiluted plasma samples from multiple individuals who tested positive for Lyme disease antibodies. Each sample represented a single collection event and provided a range of antibody reactivity for various Lyme IgM and IgG test methods. The panel included one nonreactive sample, a negative control, for all performed Lyme test methods. By including these external controls and panels of known samples, the study ensured a comprehensive evaluation of the index test’s performance and ability to accurately detect antibodies associated with Lyme disease.

2.3. Institutional Review Board Statement

Royal North Sydney Hospital (Australia) offered de-identified, anonymized, and leftover human sera reference samples for this study for evaluation, and Tezted Ltd. did not have access to any private information (i.e., name, profession, or ethnicity) from the specimens that could be linked back to the patients. As such, informed consent was not collected, as the present study was not considered human subject research as mandated by the Declaration of Helsinki embodied in Common Rule set forth by the Code of Federal Regulations, USA (Diest and Savulescu, 2002; Allen et al., 2010) and the medical research act (Finland, 488/1999 (2.2.2001/101; section 20, 30.11.2012/689), which allows the use of leftover and deidentified human serum samples without consent from the collection unit [Ministry 1 and 2]. In addition, characterized reference samples (n=32) were purchased from Plasma Global Services (USA) and SeraCare Life Sciences Inc (Headquartered in the USA with a subsidiary in France).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For quality control purposes, both laboratories, Finland and Australia, conducted interplate and interoperator precision analyses by assessing the percentage of the coefficient of variance (CV%) or precision [standard deviation (SD) divided by the mean and multiplying by 100 to give CV%] on the optical density values for all plate controls and all microbial antigens (Reed et al., 2002). The CV% was utilized to assess the performance and validity of the index test for its intended purpose. The CV% indicates the percentage of variation within a dataset, with a minor variation indicating greater precision and better index assay performance. A lower CV% suggests that the index assay is suitable for accurately testing human IgM and IgG antibodies against various antigens associated with TBDs. To evaluate the CV% for the microbial antigens in the index test, each operator repeatedly tested the negative serum control (TEZ1) provided in the kit in duplicate daily at Tezted Ltd. and the Royal North Shore Hospital. The CV% was calculated using the formula CV% = SD/mean. Generally, a CV% of less than 10 is considered very good, 10-20 is good, 20-30 is acceptable, and a CV% greater than 30 is unacceptable (Reed et al., 2002). In this study, the calculated CV% for the index test was less than or equal to 15%. Positive (PA), negative (NA), and overall (OA) agreements between the reference tests versus the index test were calculated as described by Watson and Petrie (Watson and Petrie, 2010). The reliability of each PA and NA was assessed by calculating Cohen’s kappa (k) with a 95% confidence interval (Watson and Petrie, 2010; McHugh, 2012).

A Cohen's k range of ≤ 0 indicates no agreement, 0.01–0.20 indicates no agreement to slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicates fair agreement, 0.41– 0.60 indicates moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 indicates substantial agreement and 0.81–1.00 indicates almost perfect agreement (McHugh, 2012). Cohen's kappa (k) values are presented with a 95% confidence interval. Proportionate positive and negative agreements along with Cohen's k were calculated using the EPITOOLS diagnostic test evaluation and comparison calculator, and the interrater reliability and proportional agreement analysis between various tests were carried out using only LD-positive and LD-negative patient groups [

https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/comparetwotests (accessed on 30.08.2022)]. Fisher's exact test assessed the significant differences in IgM or IgG immune responses between LD (positive and negative) and the Australian cohort. The two-tailed p values for Fisher's exact test were calculated using GraphPad, and Fisher's exact test results with p values < 0.05 were considered statistically associated or dependent (Kim, 2017).

3. Results

Initially, performance validity criteria according to the manufacturer’s quality control standard were assessed to ensure that the index assay was performed correctly and used as intended at both independent laboratories in Finland and Australia (

Table S2). All IgM and IgG internal plate controls (i.e., POS, NEG, and R

2) passed the plate validity criteria demanded by the manufacturer (

Table S2). In addition, we measured precision (CV%) to be less than 15% for the POS and R

2 internal controls, demonstrating low interplate variability at both independent laboratory sites (

Table S2). In addition, the CV% for IgM and IgG internal negative control datasets between the two labs were acceptable and consistent with a CV% of greater than 15% because the optical density values approach the lower limit of quantification. According to the CV% analysis in

Table S2, the two sites had consistent results when compared, suggesting that TICKPLEX

® can be used regularly.

Additionally, for quality control, interplate and interoperator precision analyses were conducted (

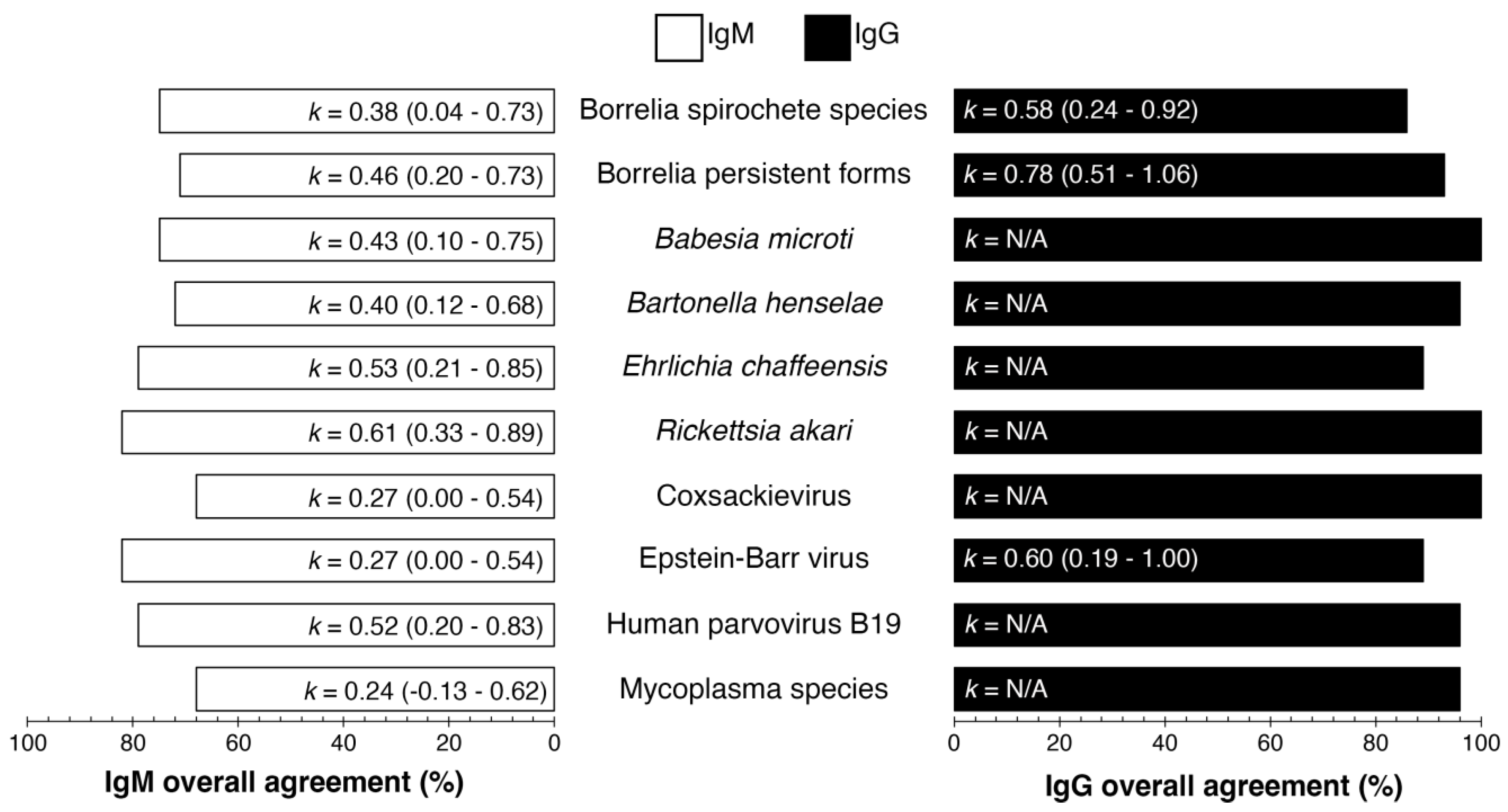

Figure 1). The overall agreement percentages ranged between 68%-82% and 86%-100% for IgM and IgG, respectively. The Cohen's kappa (k) values ranged from 0.24 (fair agreement) to 0.61 (substantial agreement) for IgM and 0.58 to 0.60 (moderate agreement overall). The k value is not applicable (N/A) for an antigen in the index test when all specimens in

Tables S3 and S4 produced only negative or positive responses in Finland and Australia.

The lowest IgM interlaboratory agreement from

Figure 1 indicated that Coxsackievirus had 68% interlaboratory agreement, k = 0.27 (95% CI 0.00 - 0.54), and

Mycoplasma fermentans and

Mycoplasma pneumoniae had 68% interlaboratory agreement, k = 0.24 (95% CI = -0.13-0.62). The highest IgG interlaboratory agreement from

Figure 1 shows that Epstein‒Barr virus had 89% interlaboratory agreement, k = 0.60 (95% CI 0.19 - 1.00), and Borrelia persistent forms had 93% interlaboratory agreement, k = 0.78 (95% CI = 0.51-1.06). The overall agreement (%) for IgG and IgM, as shown in

Figure 1, was calculated from the mean ODI (optical density index) from each laboratory (AUS and FIN) as per

Tables S3 and S4 and compared for interlaboratory agreement of each analyte per specimen.

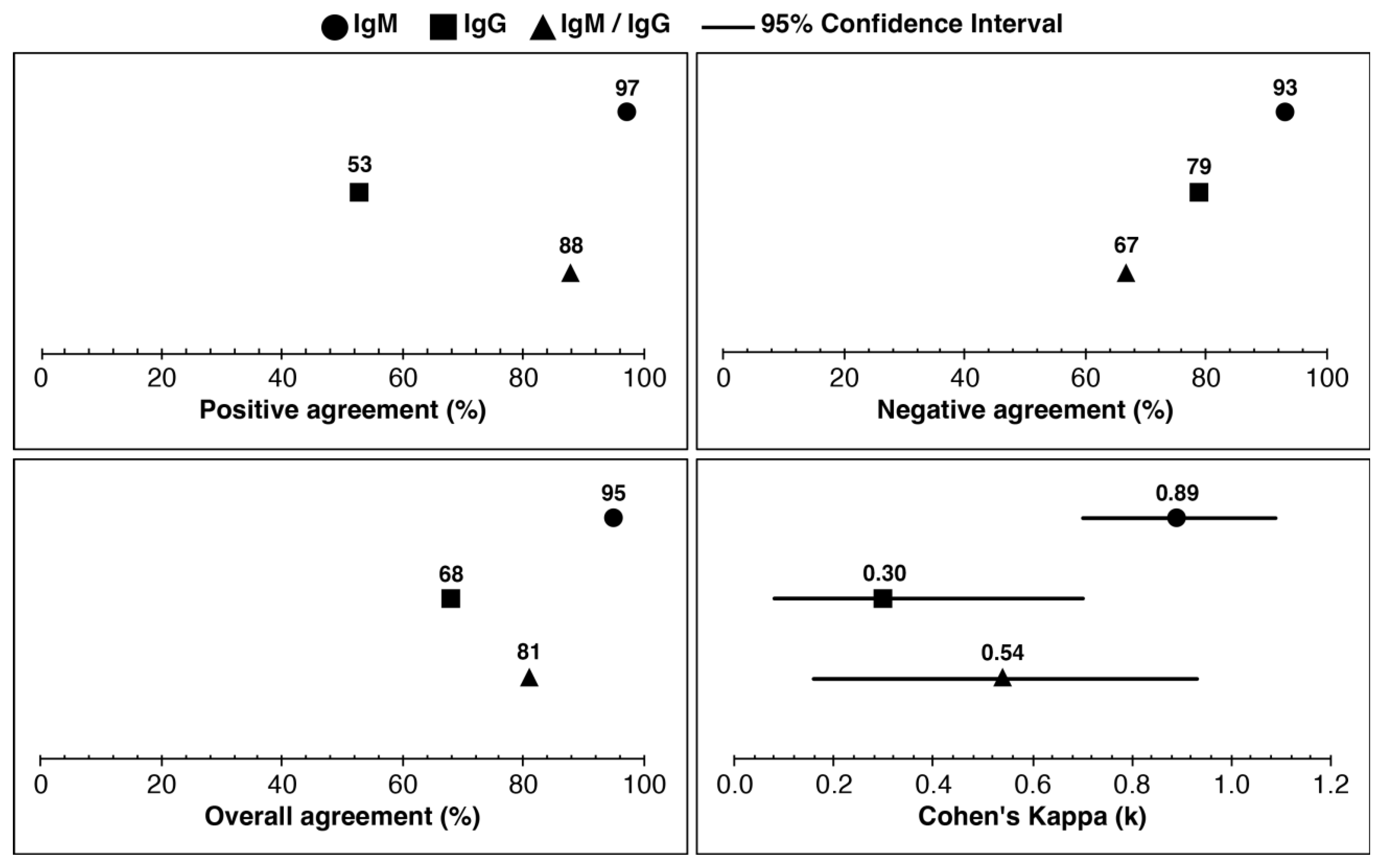

IgM, IgG, and IgM/IgG combined positive agreement were 97%, 53%, and 88%, respectively (

Figure 2). The negative agreement (%) for IgM, IgG, and IgM/IgG combined were 93%, 79%, and 67%, respectively. The overall agreement for IgM, IgG, and IgM/IgG combined was 95%, 68%, and 81%, respectively. Cohen’s kappa (

k) value was almost perfect agreement for IgM (

k=0.89), fair agreement for IgG (

k=0.30), and moderate agreement for IgM/IgG combined (

k=0.54). Laboratories tested the samples and referenced Lyme disease test results (

n=22). The clinical outcomes were determined using the CDC two-tier criteria ((CDC), 1995), as shown in

Table S5, for the reference diagnosis of each specimen. The agreement between the mean ODI of IgM and IgG was analyzed using data from both laboratories (FIN and AUS).

Table S3 displays the specimen wise analysis, while

Table S4 shows the mean ODI values for IgM and IgG. Specimen IDs AU6 and AU31 are the same specimens, but with one difference: AU6 was stored in 30% glycerol before testing, while AU31 was not stored in glycerol at -20°C. Despite this difference, both specimens had similar clinical outcomes, as demonstrated in

Tables S3 and S4. It is worth noting that AU31 was excluded from clinical assessments during the analysis between the index (TICKPLEX

®) and reference tests, as shown in

Figure 2.

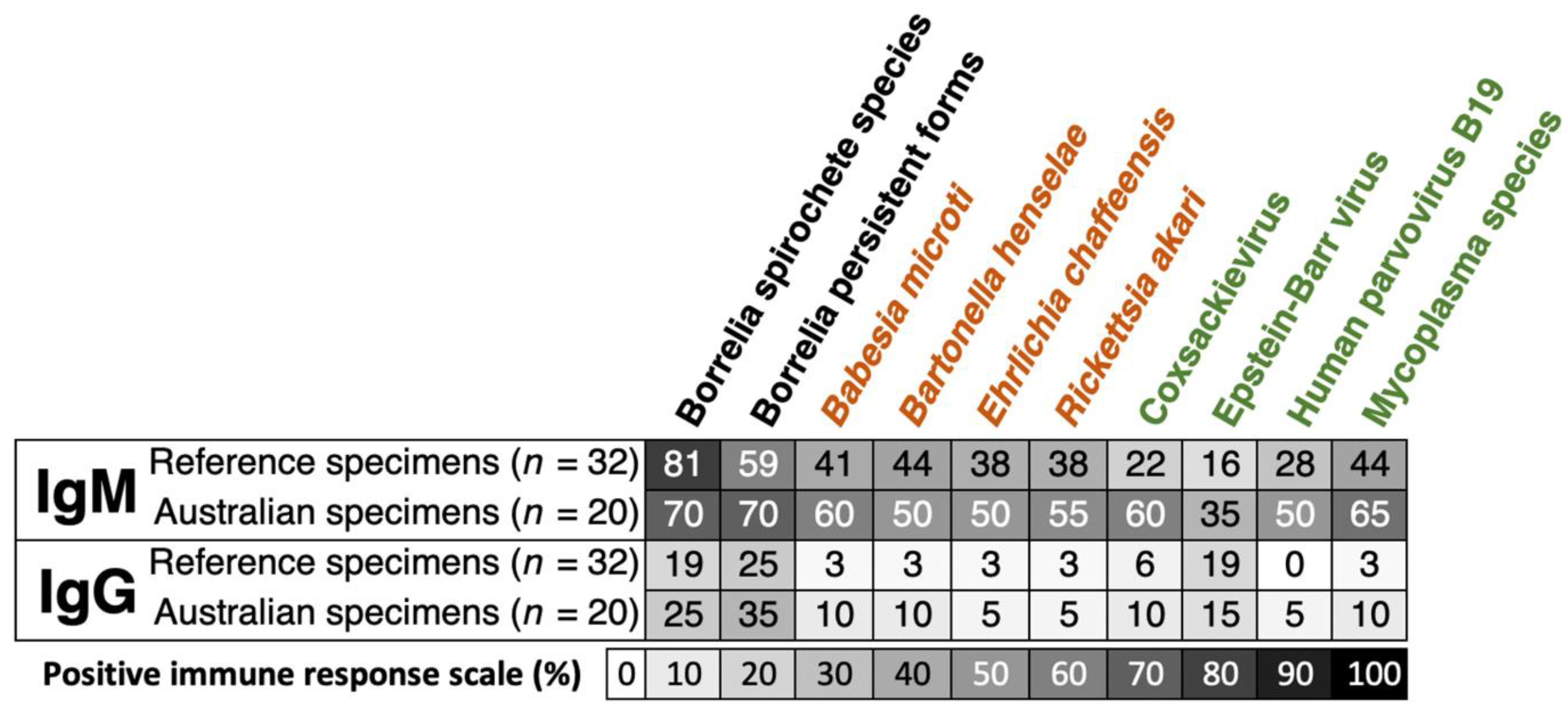

Unlike

Borrelia spirochete species, the IgM and IgG percentages of positive immune responses for the Borrelia persistent forms were higher in Australian reference samples compared to the other shared reference specimens (

Figure 3). Moreover, the proportion of IgM and IgG responses in the Australian group was frequently more elevated than that in the reference sera for tick-borne coinfections (text in orange) and related opportunistic microbes (text in green) (

Figure 3). In general, the IgM responses had a higher percentage of positivity, ranging from 35% to 70%. These responses were found to be higher in Australian samples (

n=20) compared to the reference specimens (

n=32). The proportion of immune responses against all antigens on the index assay was determined by the mean ODI of both laboratories (AUS and FIN) from

Table S6 for IgM and Table S7 for IgG.

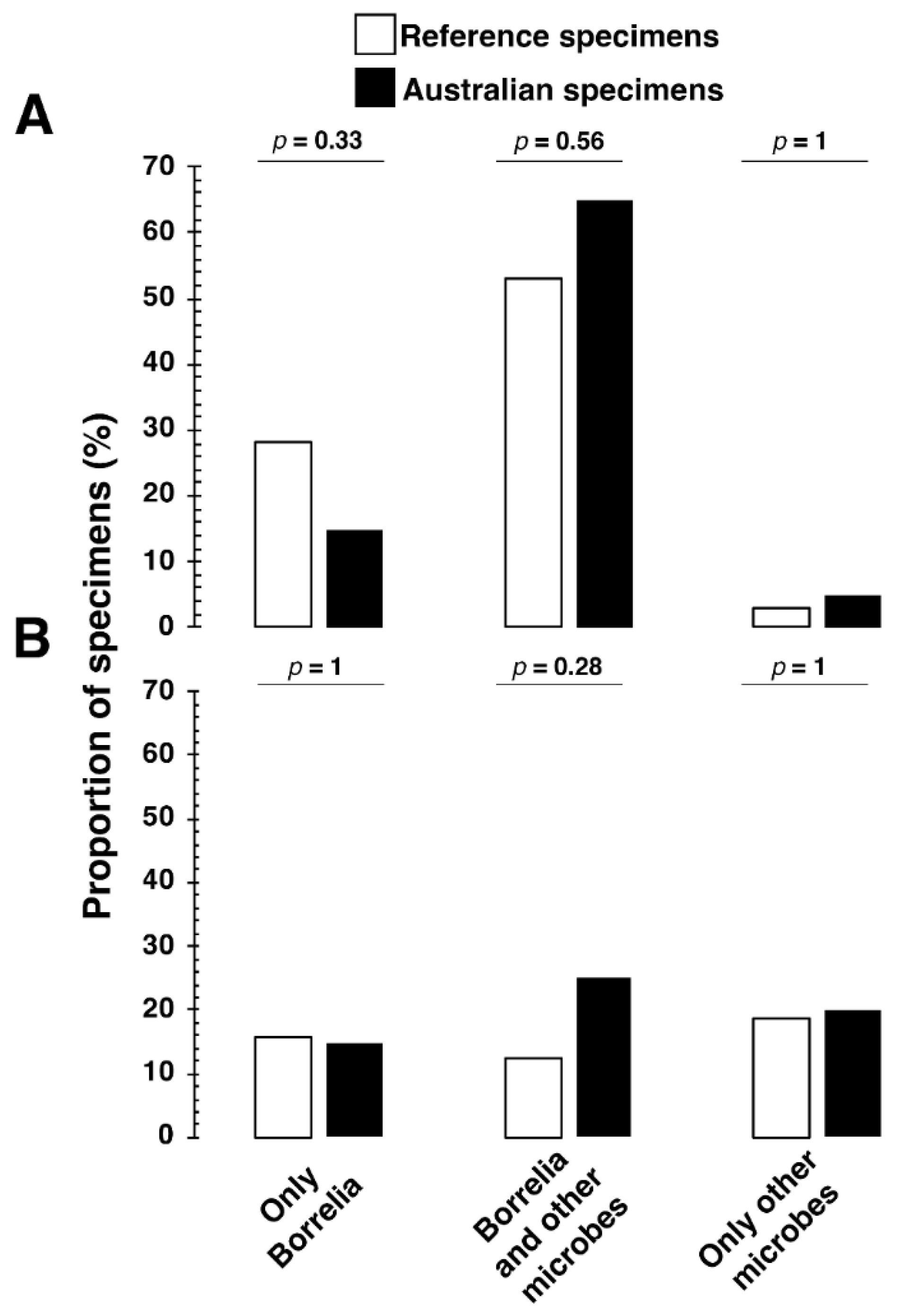

In addition, we evaluated the possibility that LLD is associated with coinfections with tickborne pathogens and other pathogens that may or may not be tickborne.

Figure 4 shows that the Lyme reference samples, and the Australian samples produced IgM and IgG antibodies to multiple microbes, some potentially associated with a tick bite. The association of antibodies to multiple microbes as well as Borrelia burgdorferi was common even among the Australian samples (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This investigation focused on the performance and reliability of a multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (TICKPLEX®) using the ODI, in detecting tick-borne diseases by comparing results obtained from two distinct institutions, Tezted Ltd. in Finland and the Royal North Shore Hospital in Australia. This was achieved by using defined blindly tested reference samples to minimize bias between two laboratories. We tested and evaluated patients' immune responses blindly and then compared these findings to established reference values available from the Australian laboratory, SeraCare Life Sciences Inc. and the Plasma Services Group.

The TICKPLEX index test was selected for its ability to measure both IgM and IgG antibodies that target Borrelia's pleomorphic forms (Meriläinen et al., 2015), including the round body or persistent forms, as well as a range of common opportunistic pathogens and co-infections simultaneously. The scientific community is reporting the significance of Borrelia's pleomorphic forms, like the findings by Golovchenko et al., who identified cyst-like structures of Borrelia in a patient's brain tissue with confirmed Lyme disease diagnosis and ongoing symptoms despite undergoing treatment (Golovchenko et al., 2023).

Moreover, the literature documents the prevalence and clinical implications of co-infections, such as those caused by Babesia spp. (Lempereur et al., 2015), Bartonella spp. (Angelakis et al., 2010), Ehrlichia spp. (Ismail et al., 2010), and Rickettsia spp (Wu et al., 2013; Koetsveld et al., 2016). Concurrently, there is an escalating awareness regarding the differential diagnostic process for patients with conditions that overlap symptomatically with tick-borne diseases, especially chronic fatigue syndrome (Bai and Richardson, 2023). In these cases, opportunistic pathogens, including Coxsackievirus (Chia, 2005; Freundt et al., 2005), Epstein-Barr virus (Pavletic and Marques, 2017; Koester et al., 2018; Ruiz-Pablos et al., 2021), Human Parvovirus B19 (Kerr et al., 2010; Berghoff, 2012), and Mycoplasma spp. (Nijs et al., 2002; Eskow et al., 2003; Nicolson et al., 2011; Liu and Janigian, 2013), are increasingly recognized for their potential to exacerbate other medical conditions, particularly in individuals with compromised immune systems, underscoring the multifaceted nature of TBD diagnosis and management.

The performance of the index assay showed substantial interlaboratory agreement (

Figure 1) for IgG, 86% to 100%, and moderate agreement for IgM, 68% to 82%, for samples tested in both Tezted Ltd. and Royal North Shore Hospital laboratories in Finland and Australia, respectively (

n=28). Overall, the interlaboratory agreement percentage between the Royal North Shore Hospital and Tezted Ltd. laboratories (

n=28) was relatively higher for IgG, 86% to 100%, than IgM, 68% to 82%. As demonstrated by Cohen’s kappa (

k), the inter-reliability for IgM ranges from fair to substantial agreement (

k=0.24 to 0.61) when compared to IgG ranging from moderate to substantial agreement (

k= 0.58 to 0.78). The IgM interlaboratory clinical agreement for

Borrelia spirochete species shows only a fair agreement (

k = 0.38). For an IgM result, as shown in

Table S2, the precision for both laboratories ranged from 0% to 3.65% for positive control values, demonstrating that the precision of techniques for both laboratories is not the cause of lower fair agreement.

Borrelia serological tests have a higher potential for false positive results when testing for LD (Seriburi et al., 2012). Therefore, the two-tier CDC criteria (CDC 2019) were used to calculate clinical agreement in both reference sera and Australian samples, as shown in

Table S5.

The combined IgM and IgG clinical agreement for Lyme disease between the Index Assay and reference test results was satisfactory (

Figure 2). The samples that were tested by both laboratories and reference Lyme disease test results (

n=22) were interpreted using the CDC two-tier criteria (Lantos et al., 2020) and showed a positive agreement value of 97% for IgM, 53% for IgG, and 88% agreement for IgM and IgG combined (

Figure 2).

The lower IgG clinical agreement in

Figure 2 is due to the pre-characterization of the sera using either EUROIMMUN or Zeus

Borrelia spp. IgG and IgM assays. Therefore, the comparison for the clinical agreement was calculated with IgM and IgG combined (Herremans et al., 2007; Tricou et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2014; Molins et al., 2017; Gomez et al., 2018). This, however, was not reflected in the negative agreement (%) for IgM, IgG, and IgM/IgG, as most reference sera,

n=22, were known as positive samples for

Borrelia spp. Some of the reference sera had been only characterized by EUROIMMUN ELISAs that contain antigens of

Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, Borrelia garinii, and Borrelia VlsE. Some sera were characterized with Zeus EIA assays with

B. burgdorferi only as an antigen. In contrast, some Australian samples were only characterized by DiaSorin Liaison XL

B. burgdorferi IgG and IgM assays or the Trinity Biotech EU Lyme Western blot. The different antigens used in each reference tests likely accounts for the lower IgG clinical agreement in

Figure 2 (Waddell et al., 2016; Kodym et al., 2018).

In our analysis presented in

Figure 3, we observed that the antibody responses for both IgM and IgG to co-infections and opportunistic pathogens were notably higher in Australian reference specimens compared to reference specimens from the USA. Expressly, while the IgG-positive response rates showed a similar range for both reference (0% to 19%) and Australian shared samples (5% to 15%), a marked difference was noted in IgM-positive response rates, with the reference samples showing 16% to 44% and Australian samples demonstrating 35% to 65%. Furthermore, as illustrated in

Figure 4, the co-infection rates with Borrelia for IgM and IgG were 53% and 13% in the reference group, contrasting with 65% and 25%, respectively, in the Australian reference samples. This discrepancy underscores a significant variation compared to co-infection rates reported between 0.7% and 41.6% in European and U.S. studies (Boyer et al., 2022). Moreover,

Ixodes tick species in Australia can transmit

Coxiella burnetii, Rickettsia australis, Rickettsia honei, and Rickettsia honei subspecies

marmioni. Australian Ixodid ticks could transmit

Babesia microti,

Anaplasma spp.

Bartonella spp.

Burkholderia spp.,

Francisella spp., and even viruses, as listed in an Australian TBD review (Dehhaghi et al., 2019).

We aim to highlight differences in the co-infection rates not to assert our findings in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 as conclusive but to emphasize the complexity of the tick-borne disease landscape in Australia, which appears to be more complex than previously recognized, thereby meriting deeper investigation. We acknowledge the inherent challenges of serological testing for Lyme and related TBDs, especially concerning cross-reactivity (Wojciechowska-Koszko et al., 2022; Grąźlewska and Holec-Gąsior, 2023), variable immune response, timing of serum sampling following exposure to tick-borne pathogens (Torina et al., 2020), and the inherent issues with tests for IgM antibodies (Kalish et al., 2001; Markowicz et al., 2021) introduce complexities in accurately interpreting seroprevalence and co-infection data. Thus, these nuances demand further research to ensure a robust understanding of the findings.

It is also important to note that 5 of 28 samples, as seen in

Table S3, tested positive for IgM in all markers on the Index Assay. Since the sera were from patients with a clinical diagnosis of LD, as confirmed by other studies and tests, this illustrates that

Borrelia spp. serology assays, like all serology assays, have the potential to yield false positive IgM results in patients who have active viral infections (Goossens et al., 1999) due to polyclonal activation of T and B lymphocytes (Wojciechowska-Koszko et al., 2022). Similarly, Borrelia IgM antibody persistence after treatment has also been demonstrated in various studies (Aguero-Rosenfeld et al., 1996; Kalish et al., 2001; Glatz et al., 2006; Seriburi et al., 2012; Elsner et al., 2015; Markowicz et al., 2021), and this limits its use in diagnosis.

The purpose of this study was to compare results obtained by two separate laboratories using the TICKPLEX

® (Index Assay), on the same serum samples, for detection of antibodies to known and potential agents infecting patients with TBI. High concordance was demonstrated between the two laboratories for IgG and IgM antibody responses in reference samples to multiple microbial antigens of tick-borne disease pathogens, as expected when compared to the referenced results. The clinical correlation, however, of Australian sera (n=20) for microbes implicated in tickborne coinfections and other opportunistic infections was challenging, as shown in

Table S8, due to a small sample size (n=20). Tests available in Australia for TBD were limited to antibody tests for

Rickettsia australis and

Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. Whilst there was likely concordance between those tests and their respective Index Assay tests -

Rickettsia akari (for

R. australis) and

Borrelia sp [

Borrelia afzelii,

Borrelia burgdorferi,

Borrelia garinii for both spirochete and persistent forms] (for B. burgdorferi s.l.), the antibodies sought were not from exactly the same species. This may compromise the ability to confirm the diagnosis of rickettsial spotted fever and Lyme disease in Australian patients, but this could also be investigated by using a larger number of samples. Similarly, the reference test results for Bartonella henselae were for total antibody results, while, in the Index Assay, IgG and IgM were tested separately.

There is a concern in Australia from patients suffering from symptoms of chronic debilitating illness which they temporally relate to tick bite but for which no definitive cause is found. This leaves patients confused, suffering, and despondent, and they are at risk of receiving incorrect or inappropriate diagnoses and treatments. The severity of illness varies among patients and can often overlap with other underlying multisystem disorders, such as chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). Limited diagnostic tests are available in Australia, which only exacerbates the situation. Using an index test such as TICKPLEX® as a diagnostic tool, in combination with clinical data, may lead to earlier and more accurate diagnoses for patients in Australia. Antibody responses to multiple microbial antigens from causative agents of TBDs were found. High concordance between laboratories was demonstrated on this small set of samples. These results provide the basis for further evaluation of TICKPLEX® on a larger number of samples from Australian patients with suspected tick-borne infections (TBIs).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G., and L.G.; methodology, JK.G., F.V., and L.G.; formal data analysis, K.G., F.V., F.S.., and L.G.; investigation, K.G., F.V., F.S., and L.G.; resources, F.V., and L.G.; data curation, K.G., F.V., F.S., and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G., and L.G.; writing—review and editing, K.G., F.V., F.S., and L.G.; visualization, K.G., and L.G.; supervision, L.G.; project administration, L.G.; funding acquisition, L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Tezted Ltd, Sanoviv Medical Institute.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the Vector Borne Disease program at Royal North Shore Hospital for their assistance.

Conflict of Interest

Following some journals’ policies, the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: K.G. and L.G. are shareholders and founders in Tezted Ltd. Tezted Ltd. provided Royal North Shore Hospital (RNSH) free kits to conduct this investigation as part of a collaborative effort. Furthermore, F.V. and F.S. are employed by the Sanoviv Medical Institute and do not have commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Sanoviv Medical Institute and Tezted Ltd. had no role in experimental design, reporting results, or the decision to publish. RNSH staff involvement was merely to evaluate the suitability, validity, and performance of the TICKPLEX® assay RUO, per regulatory and institutional policies and procedures.

References

- Aguero-Rosenfeld, M. E., Nowakowski, J., Bittker, S., Cooper, D., Nadelman, R. B., and Wormser, G. P. (1996). Evolution of the serologic response to Borrelia burgdorferi in treated patients with culture-confirmed erythema migrans. J Clin Microbiol 34, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. J., Powers, M. L., Gronowski, K. S., and Gronowski, A. M. (2010). Human Tissue Ownership and Use in Research: What Laboratorians and Researchers Should Know. Clin Chem 56, 1675–1682. [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, E., Billeter, S. A., Breitschwerdt, E. B., Chomel, B. B., and Raoult, D. (2010). Potential for Tick-borne Bartonelloses. Emerging Infectious Diseases 16, 385–391. [CrossRef]

- Australia, L. D. A. of (2016). A patient perspective - Supplementary Submission to the Senate Inquiry on the Growing Evidence of an emerging tick-borne disease that causes a Lyme-like illness for many Australian patients. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Lymelikeillness45/Submissions (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Bai, N. A., and Richardson, C. S. (2023). Posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review and comparison of pathogenesis. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 9, 183–190. [CrossRef]

- Barry, R. D., Hudson, B. J., Shafren, D. R., and Wills, M. C. (1994). Lyme Borreliosis. 75–82. [CrossRef]

- Berghoff, W. (2012). Chronic Lyme Disease and Co-infections: Differential Diagnosis. The Open Neurology Journal 6, 158–78. [CrossRef]

- Best, S. J., Tschaepe, M. I., and Wilson, K. M. (2019). Investigation of the performance of serological assays used for Lyme disease testing in Australia. Plos One 14, e0214402. [CrossRef]

- Boyer, P. H., Lenormand, C., Jaulhac, B., and Talagrand-Reboul, E. (2022). Human Co-Infections between Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. and Other Ixodes-Borne Microorganisms: A Systematic Review. Pathogens 11, 282. [CrossRef]

- Branda, J. A., Body, B. A., Boyle, J., Branson, B. M., Dattwyler, R. J., Fikrig, E., et al. (2017). Advances in Serodiagnostic Testing for Lyme Disease Are at Hand. Clin Infect Dis 66, 1133–1139. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. D. (2018). A description of ‘Australian Lyme disease’ epidemiology and impact: an analysis of submissions to an Australian senate inquiry. Intern Med J 48, 422–426. [CrossRef]

- Catherine, W. M. (1995). Lyme Borreliosis, the Australian perspective. University of Newcastle.

- (CDC), C. for D. C. and P. (n.d.). Tickborne Disease Surveillance Data Summary Print. August 11, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/data-summary/index.html (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- (CDC), C. for and (1995). Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 44, 590–1.

- Chalada, M. J., Stenos, J., and Bradbury, R. S. (2016). Is there a Lyme-like disease in Australia? Summary of the findings to date. One Heal 2, 42–54. [CrossRef]

- Chia, J. K. S. (2005). The role of enterovirus in chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Clin. Pathol. 58, 1126. [CrossRef]

- Collignon, P. J., Lum, G. D., and Robson, J. M. (2016). Does Lyme disease exist in Australia? Med J Australia 205, 413–417. [CrossRef]

- Dehhaghi, M., Panahi, H. K. S., Holmes, E. C., Hudson, B. J., Schloeffel, R., and Guillemin, G. J. (2019). Human Tick-Borne Diseases in Australia. Front Cell Infect Mi 9, 3. [CrossRef]

- Diest, P. J. van, and Savulescu, J. (2002). For and against: No consent should be needed for using leftover body material for scientific purposes * For * Against. Bmj 325, 648–651. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Zhou, G., Cao, W., Xu, X., Zhang, Y., Ji, Z., et al. (2022). Global seroprevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in human populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj Global Heal 7, e007744. [CrossRef]

- Elsner, R. A., Hastey, C. J., and Baumgarth, N. (2015). CD4+ T cells promote antibody production but not sustained affinity maturation during Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Infection and immunity 83, 48–56. [CrossRef]

- Eskow, E., Adelson, M. E., Rao, R.-V. S., and Mordechai, E. (2003). Evidence for Disseminated Mycoplasma fermentans in New Jersey Residents with Antecedent Tick Attachment and Subsequent Musculoskeletal Symptoms. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 9, 77. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X., Yang, X., Xiu, B., Qie, S., Dai, Z., Chen, K., et al. (2014). IgG, IgM and IgA antibodies against the novel polyprotein in active tuberculosis. BMC Infectious Diseases 14, 336. [CrossRef]

- Fergie, B., Basha, J., McRae, M., and McCrossin, I. (2017). Queensland tick typhus in rural New South Wales. Australas J Dermatol 58, 224–227. [CrossRef]

- Freundt, E. C., Beatty, D. C., Stegall-Faulk, T., and Wright, S. M. (2005). Possible Tick-Borne Human Enterovirus Resulting in Aseptic Meningitis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 43, 3471–3473. [CrossRef]

- Garg, K., Jokiranta, T. S., Filén, S., and Gilbert, L. (2021). Assessing the Need for Multiplex and Multifunctional Tick-Borne Disease Test in Routine Clinical Laboratory Samples from Lyme Disease and Febrile Patients with a History of a Tick Bite. Tropical Medicine Infect Dis 6, 38. [CrossRef]

- Glatz, M., Golestani, M., Kerl, H., and Müllegger, R. R. (2006). Clinical relevance of different IgG and IgM serum antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi after antibiotic therapy for erythema migrans: long-term follow-up study of 113 patients. Archives of dermatology 142, 862–8. [CrossRef]

- Gofton, A. W., Blasdell, K. R., Taylor, C., Banks, P. B., Michie, M., Roy-Dufresne, E., et al. (2022). Metatranscriptomic profiling reveals diverse tick-borne bacteria, protozoans and viruses in ticks and wildlife from Australia. Transbound Emerg Dis 69, e2389–e2407. [CrossRef]

- Golovchenko, M., Opelka, J., Vancova, M., Sehadova, H., Kralikova, V., Dobias, M., et al. (2023). Concurrent Infection of the Human Brain with Multiple Borrelia Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 16906. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C. A., Budvytyte, L. N., Press, C., Zhou, L., McLeod, R., Maldonado, Y., et al. (2018). Evaluation of Three Point-of-Care Tests for Detection of Toxoplasma Immunoglobulin IgG and IgM in the United States: Proof of Concept and Challenges. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 5, ofy215. [CrossRef]

- Goossens, H. A. T., Bogaard, A. E. van den, and Nohlmans, M. K. E. (1999). Evaluation of Fifteen Commercially Available Serological Tests for Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis. European J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 18, 551–560. [CrossRef]

- Graves, S. R., Dwyer, B., McColl, D., and McDade, J. (1991). Flinders Island spotted fever: a newly recognised endemic focus of tick typhus in Bass Strait: Part 2. Serological investigations. Med J Australia 154, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Graves, S. R., and Stenos, J. (2017). Tick-borne infectious diseases in Australia. Med J Australia 206, 320–324. [CrossRef]

- Grąźlewska, W., and Holec-Gąsior, L. (2023). Antibody Cross-Reactivity in Serodiagnosis of Lyme Disease. Antibodies 12, 63. [CrossRef]

- Haisman-Welsh, R., and Marshall, C. (2020). Debilitating Symptom Complexes Attributed to Ticks (DSCATT) Clinical Pathway. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/07/debilitating-symptom-complexes-attributed-to-ticks-dscatt-clinical-pathway.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Harley, D., Sleigh, A., and Ritchie, S. (2001). Ross River Virus Transmission, Infection, and Disease: a Cross-Disciplinary Review. Clin Microbiol Rev 14, 909–932. [CrossRef]

- Herremans, M., Vermeulen, M. J., Kassteele, V. J. de, Bakker, J., Schellekens, J. F. P., and Koopmans, M. P. G. (2007). The use of Bartonella henselae-specific age dependent IgG and IgM in diagnostic models to discriminate diseased from non-diseased in Cat Scratch Disease serology. Journal of Microbiological Methods 71, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B. J., Barry, R. D., Shafren, D. R., Wills, M. C., Caves, S., and Lennox, V. A. (1994). Does Lyme Borreliosis Exist in Australia? Journal of Spirochetal and Tick-borne diseases 1.

- Hudson, B. J., Stewart, M., Lennox, V. A., Fukunaga, M., Yabuki, M., Macorison, H., et al. (1998). Culture-positive Lyme borreliosis. Med J Australia 168, 500–502. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N., Bloch, K. C., and McBride, J. W. (2010). Human Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 30, 261–292. [CrossRef]

- Kalish, R. A., McHugh, G., Granquist, J., Shea, B., Ruthazer, R., and Steere, A. C. (2001). Persistence of immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10-20 years after active Lyme disease. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 33, 780–5. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J. R., Gough, J., Richards, S. C. M., Main, J., Enlander, D., McCreary, M., et al. (2010). Antibody to parvovirus B19 nonstructural protein is associated with chronic arthralgia in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. J. Gen. Virol. 91, 893–897. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. (2017). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor Dent Endod 42, 152. [CrossRef]

- Kodym, P., Kurzová, Z., Berenová, D., Pícha, D., Smíšková, D., Moravcová, L., et al. (2018). Serological Diagnostics of Lyme Borreliosis: Comparison of Universal and Borrelia Species-Specific Tests Based on Whole-Cell and Recombinant Antigens. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 56, e00601-18. [CrossRef]

- Koester, T. M., Meece, J. K., Fritsche, T. R., and Frost, H. M. (2018). Infectious Mononucleosis and Lyme Disease as Confounding Diagnoses: A Report of 2 Cases. Clin Medicine Res 16, 66–68. [CrossRef]

- Koetsveld, J., Tijsse-Klasen, E., Herremans, T., Hovius, J. W., and Sprong, H. (2016). Serological and molecular evidence for spotted fever group Rickettsia and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato co-infections in The Netherlands. Ticks and tick-borne diseases 7, 371–7. [CrossRef]

- Kugeler, K. J., Earley, A., Mead, P. S., and Hinckley, A. F. (2024). Surveillance for Lyme Disease After Implementation of a Revised Case Definition — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 73, 118–123. [CrossRef]

- Kugeler, K. J., Schwartz, A. M., Delorey, M. J., Mead, P. S., and Hinckley, A. F. (2021). Estimating the Frequency of Lyme Disease Diagnoses, United States, 2010–2018 - Volume 27, Number 2—February 2021 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. Emerg Infect Dis 27, 616–619. [CrossRef]

- Lantos, P. M., Rumbaugh, J., Bockenstedt, L. K., Falck-Ytter, Y. T., Aguero-Rosenfeld, M. E., Auwaerter, P. G., et al. (2020). Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis 72, e1–e48. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R. H., Bradbury, R., and Cullen, J. S. (1986). Lyme disease on the NSW central coast. Med J Australia 145, 364–364. [CrossRef]

- Lempereur, L., Shiels, B., Heyman, P., Moreau, E., Saegerman, C., Losson, B., et al. (2015). A retrospective serological survey on human babesiosis in Belgium. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 21, 96.e1-96.e7. [CrossRef]

- Liu, E. M., and Janigian, R. H. (2013). Mycoplasma pneumoniae: The Other Masquerader. JAMA Ophthalmology 131, 251–253. [CrossRef]

- Markowicz, M., Reiter, M., Gamper, J., Stanek, G., and Stockinger, H. (2021). Persistent Anti-Borrelia IgM Antibodies without Lyme Borreliosis in the Clinical and Immunological Context. Microbiol Spectr 9, e01020-21. [CrossRef]

- Maud, C., and Berk, M. (2013). Neuropsychiatric presentation of Lyme disease in Australia. Australian New Zealand J Psychiatry 47, 397–398. [CrossRef]

- McCrossin, I. (1986). Lyme disease on the NSW south coast. Med J Australia 144, 724–725. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Medica 22, 276–282. [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, L., Herranen, A., Schwarzbach, A., and Gilbert, L. (2015). Morphological and biochemical features of Borrelia burgdorferi pleomorphic forms. Microbiology 161, 516–527. [CrossRef]

- Molins, C. R., Delorey, M. J., Replogle, A., Sexton, C., and Schriefer, M. E. (2017). Evaluation of bioMérieux’s Dissociated Vidas Lyme IgM II and IgG II as a First-Tier Diagnostic Assay for Lyme Disease. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 55, 1698–1706. [CrossRef]

- N, S. (1987). Lyme borreliosis - a case report for Queensland. Communicable Disease Intelligence.

- Nicolson, G. L., Nicolson, N. L., and Haier, J. (2011). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients Subsequently Diagnosed with Lyme Disease Borrelia burgdorferi: Evidence for Mycoplasma Species Coinfections. J Chronic Fatigue Syndrome 14, 5–17. [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J., Nicolson, G. L., Becker, P. D., Coomans, D., and Meirleir, K. D. (2002). High prevalence of Mycoplasma infections among European chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Examination of four Mycoplasma species in blood of chronic fatigue syndrome patients. FEMS Immunol. Méd. Microbiol. 34, 209–214. [CrossRef]

- Pavletic, A. J., and Marques, A. R. (2017). Early Disseminated Lyme Disease Causing False-Positive Serology for Primary Epstein-Barr Virus Infection: Report of 2 Cases. Clin Infect Dis 65, 336–337. [CrossRef]

- PINN, T. G., and SOWDEN, D. (1998). Queensland tick typhus. Aust Nz J Med 28, 824–826. [CrossRef]

- Reed, G. F., Lynn, F., and Meade, B. D. (2002). Use of coefficient of variation in assessing variability of quantitative assays. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology 9, 1235–9. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pablos, M., Paiva, B., Montero-Mateo, R., Garcia, N., and Zabaleta, A. (2021). Epstein-Barr Virus and the Origin of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 12, 656797. [CrossRef]

- Russell, R. C., Doggett, S. L., Munro, R., Ellis, J., Avery, D., Hunt, C., et al. (1994). Lyme disease: a search for a causative agent in ticks in south–eastern Australia. Epidemiol Infect 112, 375–384. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J. L. (2015). Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Lab Med 35, 765–778. [CrossRef]

- Schnall, J., Oliver, G., Braat, S., Macdonell, R., Gibney, K. B., and Kanaan, R. A. (2022). Characterising DSCATT: A case series of Australian patients with debilitating symptom complexes attributed to ticks. Australian New Zealand J Psychiatry 56, 974–984. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A. M., Kugeler, K. J., Nelson, C. A., Marx, G. E., and Hinckley, A. F. (2021). Use of Commercial Claims Data for Evaluating Trends in Lyme Disease Diagnosis, United States - Volume 27, Number 2—February 2021 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. Emerg Infect Dis 27, 499–507. [CrossRef]

- Seriburi, V., Ndukwe, N., Chang, Z., Cox, M. E., and Wormser, G. P. (2012). High frequency of false positive IgM immunoblots for Borrelia burgdorferi in Clinical Practice. Clin Microbiol Infec 18, 1236–1240. [CrossRef]

- Sexton, D. J., King, G., and Dwyer, B. (1990). Fatal Queensland Tick Typhus. J Infect Dis 162, 779–780. [CrossRef]

- Shah, J. S., Liu, S., Cruz, I. D., Poruri, A., Maynard, R., Shkilna, M., et al. (2019). Line Immunoblot Assay for Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever and Findings in Patient Sera from Australia, Ukraine and the USA. Healthc 7, 121. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A., Armstrong, M., Graves, S., and Hajkowicz, K. (2017). Rickettsia australis and Queensland Tick Typhus: A Rickettsial Spotted Fever Group Infection in Australia. Am J Tropical Medicine Hyg 97, 24–29. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A., Fracp, J. Glass., Patel, A., Watt, G., Cripps, A., and Clancy, R. (1982). Lyme arthritis in the Hunter Valley. Med J Australia 1, 139–139. [CrossRef]

- Torina, A., Villari, S., Blanda, V., Vullo, S., Manna, M. P. L., Azgomi, M. S., et al. (2020). Innate Immune Response to Tick-Borne Pathogens: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Induced in the Hosts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5437. [CrossRef]

- Tricou, V., Vu, H. T., Quynh, N. V., Nguyen, C. V., Tran, H. T., Farrar, J., et al. (2010). Comparison of two dengue NS1 rapid tests for sensitivity, specificity and relationship to viraemia and antibody responses. BMC Infectious Diseases 10, 142. [CrossRef]

- Waddell, L. A., Greig, J., Mascarenhas, M., Harding, S., Lindsay, R., and Ogden, N. (2016). The Accuracy of Diagnostic Tests for Lyme Disease in Humans, A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of North American Research. PLOS ONE 11, e0168613. [CrossRef]

- Watson, P. F., and Petrie, A. (2010). Method agreement analysis: A review of correct methodology. Theriogenology 73, 1167–1179. [CrossRef]

- Wills, M. C., and Barry, R. D. (1991). Detecting the cause of Lyme disease in Australia. Med J Australia 155, 275–275. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska-Koszko, I., Kwiatkowski, P., Sienkiewicz, M., Kowalczyk, M., Kowalczyk, E., and Dołęgowska, B. (2022). Cross-Reactive Results in Serological Tests for Borreliosis in Patients with Active Viral Infections. Pathogens 11, 203. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-B., Na, R.-H., Wei, S.-S., Zhu, J.-S., and Peng, H.-J. (2013). Distribution of tick-borne diseases in China. Parasites & Vectors 6, 1–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).