Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

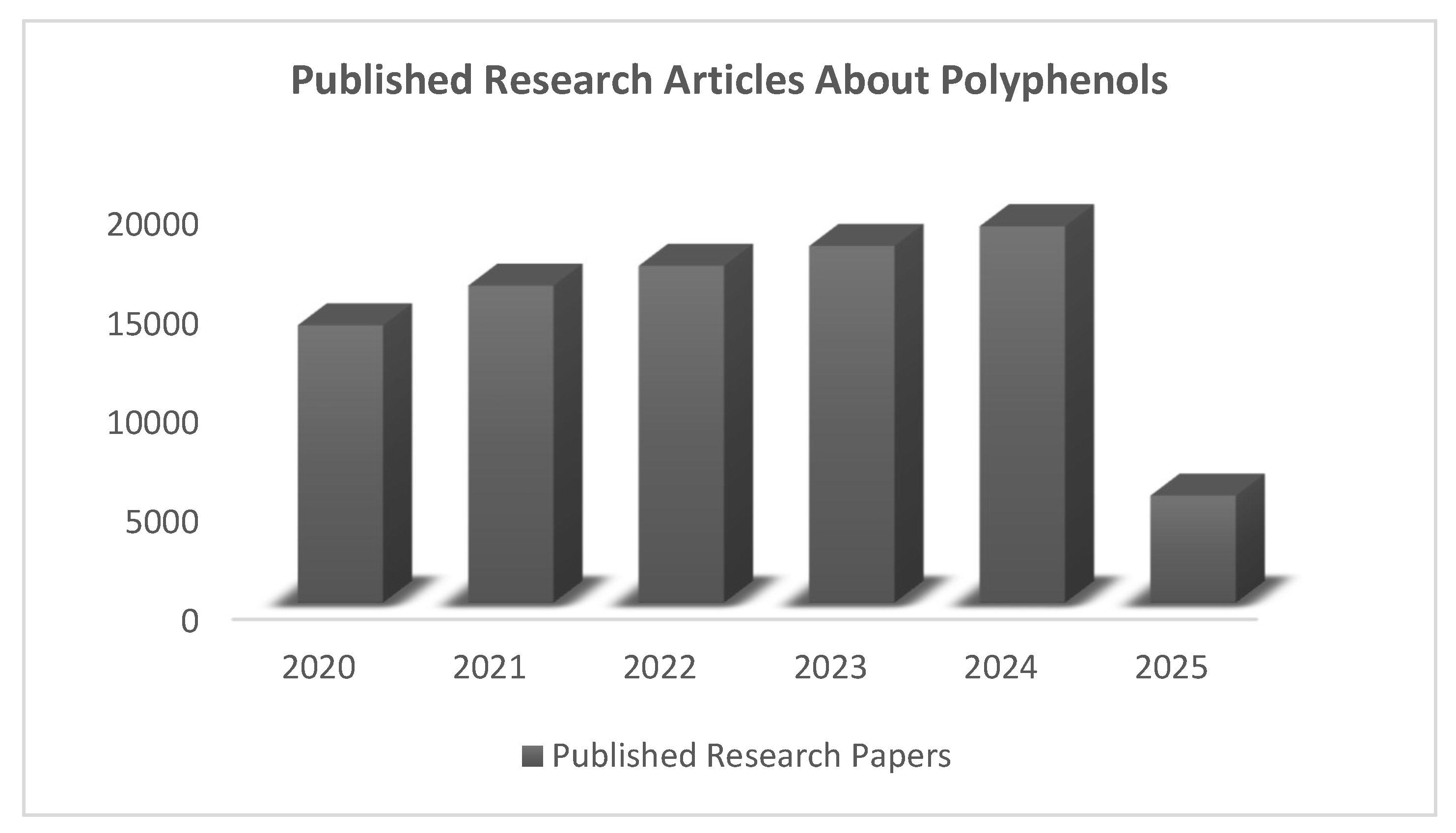

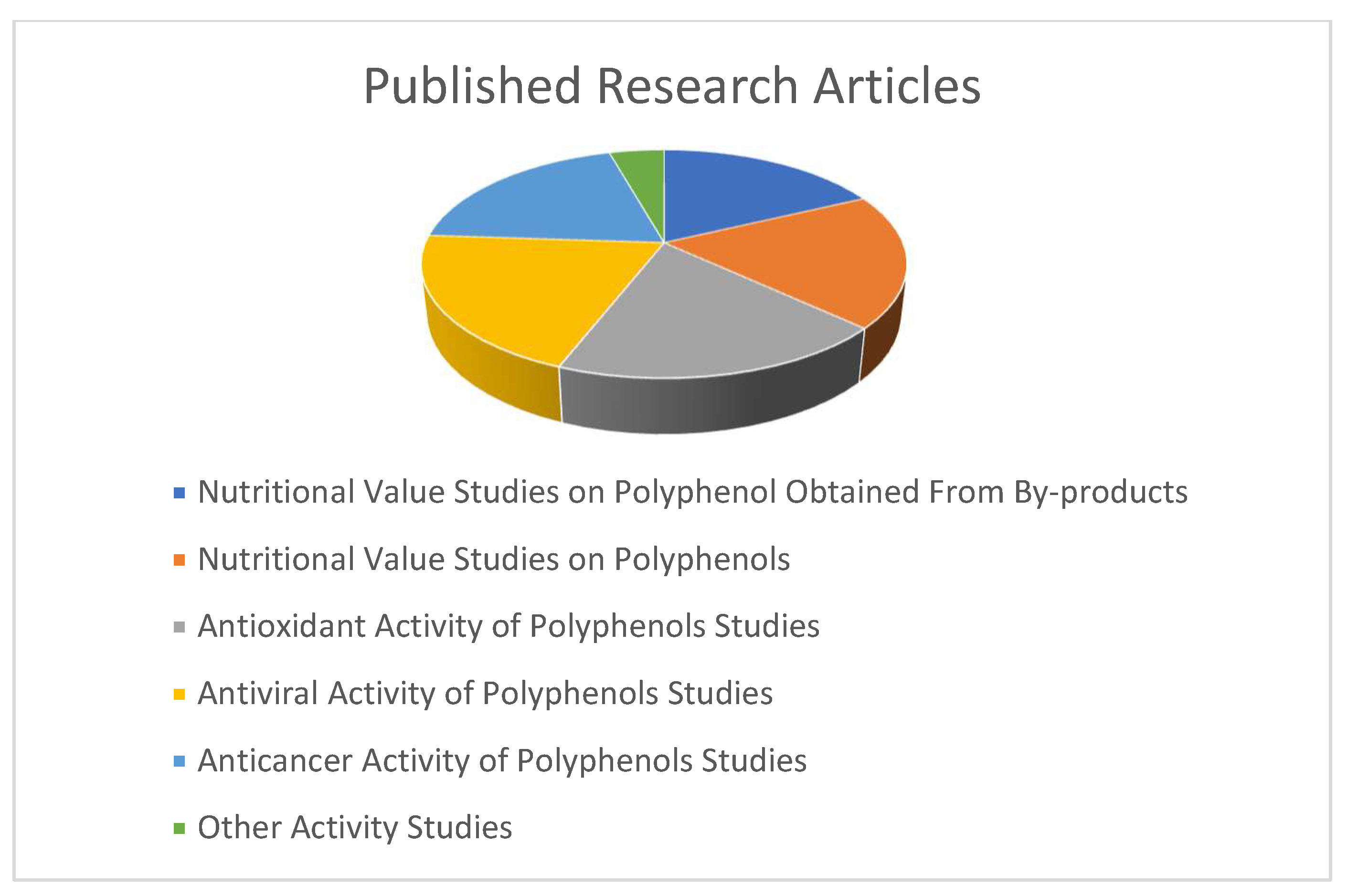

1. Introduction

2. Polyphenols in Foods

3. Several Influencing Factors to Polyphenol Contents of Foods

4. Application of Polyphenols in the Food Industry

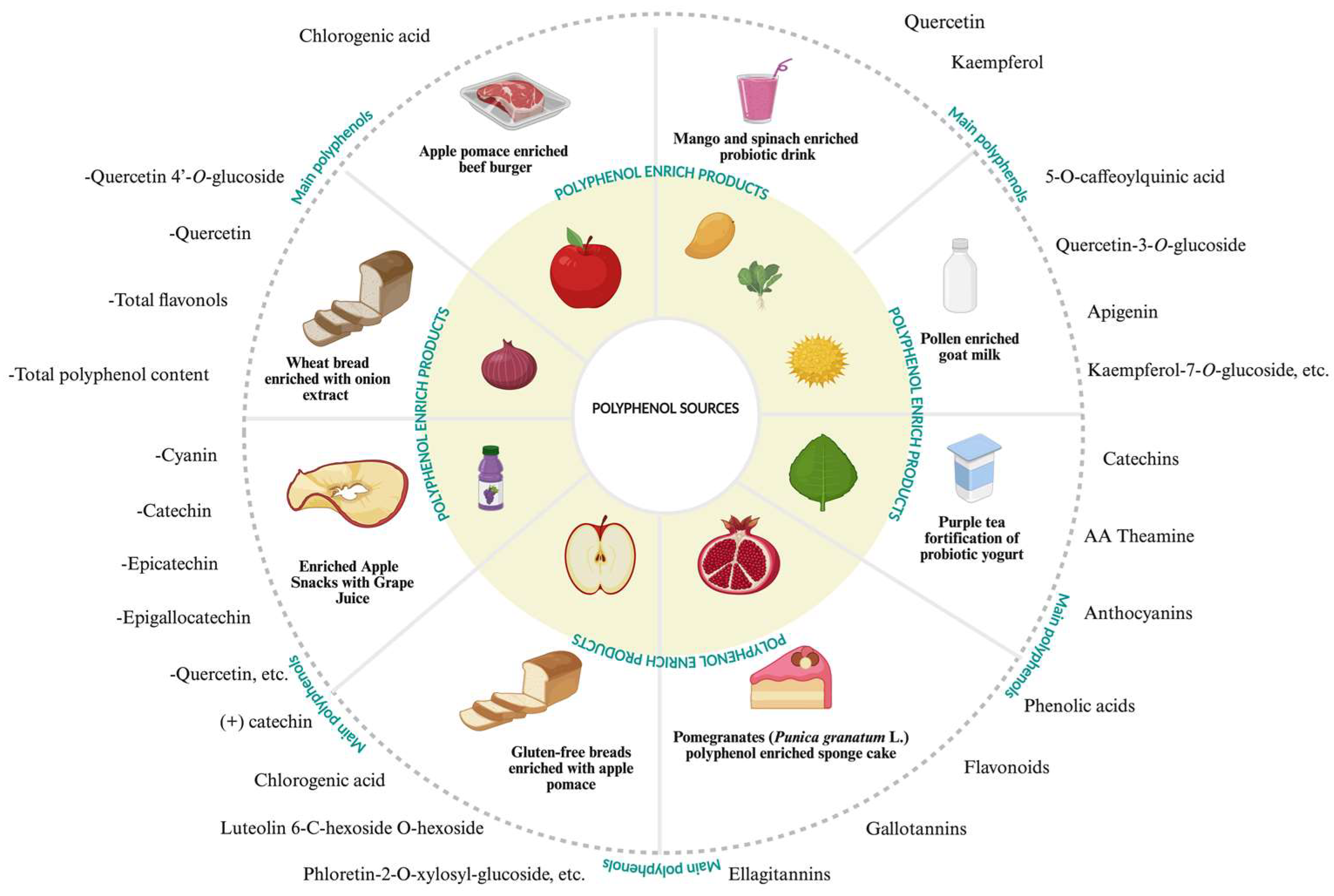

4.1. Functional Foods and Polyphenol-Enriched Products

5. Waste Product Including High Polyphenol Valorization in Food Industry

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, J.; Hao, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Metabolic and Microbial Modulation of Phenolic Compounds from Raspberry Leaf Extract under in Vitro Digestion and Fermentation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 5168–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żary-Sikorska, E.; Fotschki, B.; Jurgoński, A.; Kosmala, M.; Milala, J.; Kołodziejczyk, K.; Majewski, M.; Ognik, K.; Juśkiewicz, J. Protective Effects of a Strawberry Ellagitannin-Rich Extract against Pro-Oxidative and Pro-Inflammatory Dysfunctions Induced by a High-Fat Diet in a Rat Model. Molecules 2020, 25, 5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; You, M.; Toney, A.M.; Kim, J.; Giraud, D.; Xian, Y.; Ye, F.; Gu, L.; Ramer-Tait, A.E.; Chung, S. Red Raspberry Polyphenols Attenuate High-Fat Diet–Driven Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome and Its Paracrine Suppression of Adipogenesis via Histone Modifications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez-Guajardo, C.; Ferreira, S.R.S.; Mazzutti, S.; Guerra-Valle, M.E.; Sáez-Trautmann, G.; Moreno, J. Influence of In Vitro Digestion on Antioxidant Activity of Enriched Apple Snacks with Grape Juice. Foods 2020, 9, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Sandhu, A.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B. Characterization of Wild Blueberry Polyphenols Bioavailability and Kinetic Profile in Plasma over 24-h Period in Human Subjects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, G.; Noviello, M.; Calabrese, F.; Gambacorta, G.; Giannelli, G.; De Angelis, M. Effects of Grape Pomace Polyphenols and In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion on Antimicrobial Activity: Recovery of Bioactive Compounds. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaldo, L.; Lombardi, S.; Gaspari, A.; Rubino, M.; Izzo, L.; Narváez, A.; Ritieni, A.; Grosso, M. In Vitro Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenolic Compounds from Spent Coffee Grounds-Enriched Cookies. Foods 2021, 10, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, K.; Mosammad, S.S.; Heri, K. Antimicrobial Activities of Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Pomace Polyphenols as a Source of Naturally Occurring Bioactive Components. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 2157–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Yang, X.; Bai, F.; Li, D.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Guo, Y. Young Apple Polyphenols as Natural α-Glucosidase Inhibitors: In Vitro and in Silico Studies. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 96, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, K.S.M.; Hefzalrahman, T.; Morsi, M.K.S.; Morsy, N.F.S.; Abd El-Salam, E.A. Optimization of Ultrasound- and Enzymatic-Assisted Extractions of Polyphenols from Dried Red Onion Peels and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activities. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 54, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Średnicka-Tober, D.; Ponder, A.; Hallmann, E.; Głowacka, A.; Rozpara, E. The Profile and Content of Polyphenols and Carotenoids in Local and Commercial Sweet Cherry Fruits (Prunus Avium L.) and Their Antioxidant Activity In Vitro. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torghabe, S.Y.; Alavi, P.; Rostami, S.; Davies, N.M.; Kesharwani, P.; Karav, S.; Sahebkar, A. Modulation of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System by Curcumin: Therapeutic Implications in Cancer. Pathol. - Res. Pract. 2025, 265, 155741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili Safaryan, M.; Ahmadi Gavlighi, H.; Udenigwe, C.C.; Tabarsa, M.; Barzegar, M. Associated Changes in the Structural and Antioxidant Activity of Myofibrillar Proteins via Interaction of Polyphenolic Compounds and Protein Extracted from Lentil (Lens Culinaris). J. Food Biochem. 2023, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, R.; Doge, R.; Takae, M.; Aoki, A.; Kawasaki, T.; Saito, A. Potential of Raspberry Flower Petals as a Rich Source of Bioactive Flavan-3-Ol Derivatives Revealed by Polyphenolic Profiling. Nutraceuticals 2023, 3, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Jin, L.; Yang, R.; Liang, Y.; Nile, S.H.; Kai, G. Comparative Studies on Selection of High Polyphenolic Containing Chinese Raspberry for Evaluation of Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Potentials. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Neto, J.P.R.; De Luna Freire, M.O.; De Albuquerque Lemos, D.E.; Ribeiro Alves, R.M.F.; De Farias Cardoso, E.F.; De Moura Balarini, C.; Duman, H.; Karav, S.; De Souza, E.L.; De Brito Alves, J.L. Targeting Gut Microbiota with Probiotics and Phenolic Compounds in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2024, 13, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, W.; Zagórska, J.; Michalak-Tomczyk, M.; Karav, S.; Wawruszak, A. Plant Phenolics in the Prevention and Therapy of Acne: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Abe, S.K.; Saito, E.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S.; Ito, H.; Lin, Y.; Tamakoshi, A.; Sado, J.; Kitamura, Y.; et al. Green Tea Consumption and Mortality in Japanese Men and Women: A Pooled Analysis of Eight Population-Based Cohort Studies in Japan. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.S.; Butt, M.S.; Sultan, M.T.; Mushtaq, Z.; Ahmad, S.; Dewanjee, S.; De Feo, V.; Zia-Ul-Haq, M. Preventive Role of Green Tea Catechins from Obesity and Related Disorders Especially Hypercholesterolemia and Hyperglycemia. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Cui, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Li, X. Apple Polyphenols Extracts Ameliorate High Carbohydrate Diet-Induced Body Weight Gain by Regulating the Gut Microbiota and Appetite. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotschki, B.; Sójka, M.; Kosmala, M.; Juśkiewicz, J. Prebiotics Together with Raspberry Polyphenolic Extract Mitigate the Development of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases in Zucker Rats. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wu, C. Protective Effect of Apple Polyphenols on Chronic Ethanol Exposure-Induced Neural Injury in Rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 326, 109113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birru, R.L.; Bein, K.; Bondarchuk, N.; Wells, H.; Lin, Q.; Di, Y.P.; Leikauf, G.D. Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Apple Polyphenol Phloretin on Respiratory Pathogens Associated With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 652944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Martínez, L.; Mut-Salud, N.; Ruiz-García, J.A.; Falcón-Piñeiro, A.; Maijó-Ferré, M.; Baños, A.; De La Torre-Ramírez, J.M.; Guillamón, E.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M. Phytochemicals Determination, and Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Activities of Blackberry Fruits. Foods 2023, 12, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Han, L.; Li, X.; Xue, Z.; Zhou, F. Antioxidant and Antitumor Effects and Immunomodulatory Activities of Crude and Purified Polyphenol Extract from Blueberries. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2016, 10, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lang, Y.; Li, E.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, B. Blueberry Polyphenols Extract as a Potential Prebiotic with Anti-Obesity Effects on C57BL/6 J Mice by Modulating the Gut Microbiota. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 64, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath-Canning, M.; Unruh, S.; Vyas, P.; Daneshtalab, N.; Igamberdiev, A.U.; Weber, J.T. Fruits and Leaves from Wild Blueberry Plants Contain Diverse Polyphenols and Decrease Neuroinflammatory Responses in Microglia. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 68, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Fan, R.; Shao, J.; Mulcahy Toney, A.; Chung, S.; Ramer-Tait, A.E. Polyphenolic Fractions Isolated from Red Raspberry Whole Fruit, Pulp, and Seed Differentially Alter the Gut Microbiota of Mice with Diet-Induced Obesity. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 76, 104288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; He, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Chen, R.; Kang, J. Phenolic Acid Profiling, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities, and miRNA Regulation in the Polyphenols of 16 Blueberry Samples from China. Molecules 2017, 22, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, P.; Pulina, S.; Del Caro, A.; Fadda, C.; Urgeghe, P.P.; De Bruno, A.; Difonzo, G.; Caponio, F.; Romeo, R.; Piga, A. Gluten-Free Breadsticks Fortified with Phenolic-Rich Extracts from Olive Leaves and Olive Mill Wastewater. Foods 2021, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, H.; Meng, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, W.; Li, W.; Lü, H. Effect of Blackberry Anthocyanins and Its Combination with Tea Polyphenols on the Oxidative Stability of Lard and Olive Oil. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1286209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasdemir, Y.; Findik, B.T.; Yildiz, H.; Birisci, E. Blueberry-Added Black Tea: Effects of Infusion Temperature, Drying Method, Fruit Concentration on the Iron-Polyphenol Complex Formation, Polyphenols Profile, Antioxidant Activity, and Sensory Properties. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostić, A.Ž.; Milinčić, D.D.; Stanisavljević, N.S.; Gašić, U.M.; Lević, S.; Kojić, M.O.; Lj. Tešić, Ž.; Nedović, V.; Barać, M.B.; Pešić, M.B. Polyphenol Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Properties of in Vitro Digested Spray-Dried Thermally-Treated Skimmed Goat Milk Enriched with Pollen. Food Chem. 2021, 351, 129310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozleyen, A.; Cinar, Z.O.; Karav, S.; Bayraktar, A.; Arslan, A.; Kayili, H.M.; Salih, B.; Tumer, T.B. Biofortified Whey/Deglycosylated Whey and Chickpea Protein Matrices: Functional Enrichment by Black Mulberry Polyphenols. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollini, L.; Blasi, F.; Ianni, F.; Grispoldi, L.; Moretti, S.; Di Veroli, A.; Cossignani, L.; Cenci-Goga, B.T. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction and Characterization of Polyphenols from Apple Pomace, Functional Ingredients for Beef Burger Fortification. Molecules 2022, 27, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaratunga, R.; Kantono, K.; Kam, R.; Gannabathula, S.; Hamid, N. Microencapsulated Asiatic Pennywort ( Centella Asiatica) Fortified Chocolate Oat Milk Beverage: Formulation, Polyphenols Content, and Consumer Acceptability. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 5395–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seke, F.; Adiamo, O.Q.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Sivakumar, D. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity, Bioaccessibility, and Thermal Stability of Encapsulated Strawberry Fruit (Fragaria × Ananassa) Polyphenols. Foods 2023, 12, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belščak-Cvitanović, A.; Lević, S.; Kalušević, A.; Špoljarić, I.; Đorđević, V.; Komes, D.; Mršić, G.; Nedović, V. Efficiency Assessment of Natural Biopolymers as Encapsulants of Green Tea (Camellia Sinensis L.) Bioactive Compounds by Spray Drying. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015, 8, 2444–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zokti, J.; Sham Baharin, B.; Mohammed, A.; Abas, F. Green Tea Leaves Extract: Microencapsulation, Physicochemical and Storage Stability Study. Molecules 2016, 21, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedola, A.; Palermo, C.; Centonze, D.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Characterization and Bio-Accessibility Evaluation of Olive Leaf Extract-Enriched “Taralli. ” Foods 2020, 9, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaja, A.; Czubaszek, A.; Wyspiańska, D.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Kucharska, A.Z. Quality of Wheat Bread Enriched with Onion Extract and Polyphenols Content and Antioxidant Activity Changes during Bread Storage. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannou, O.; Koca, I. Greener Extraction of Anthocyanins and Antioxidant Activity from Blackberry (Rubus Spp) Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. LWT 2022, 158, 113184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koraqi, H.; Petkoska, A.T.; Khalid, W.; Sehrish, A.; Ambreen, S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Optimization of the Extraction Conditions of Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds from Strawberry Fruits (Fragaria x Ananassa Duch.) Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Anal. Methods 2023, 16, 1030–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y. An Integrated Extraction–Purification Process for Raspberry Leaf Polyphenols and Their In Vitro Activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cladis, D.P.; Debelo, H.; Lachcik, P.J.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Weaver, C.M. Increasing Doses of Blueberry Polyphenols Alter Colonic Metabolism and Calcium Absorption in Ovariectomized Rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 2000031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarıtaş, S.; Portocarrero, A.C.M.; Miranda López, J.M.; Lombardo, M.; Koch, W.; Raposo, A.; El-Seedi, H.R.; De Brito Alves, J.L.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Karav, S.; et al. The Impact of Fermentation on the Antioxidant Activity of Food Products. Molecules 2024, 29, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotschki, B.; Cholewińska, E.; Ognik, K.; Sójka, M.; Milala, J.; Fotschki, J.; Wiczkowski, W.; Juśkiewicz, J. Dose-Related Regulatory Effect of Raspberry Polyphenolic Extract on Cecal Microbiota Activity, Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation in Rats Fed a Diet Rich in Saturated Fats. Nutrients 2023, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Akshit, F.; Matiwalage, I.; Sasidharan, S.; Alvarez, C.M.; Wescombe, P.; Mohan, M.S. Preferential Binding of Polyphenols in Blackcurrant Extracts with Milk Proteins and the Effects on the Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenols. Foods 2024, 13, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Aadil, R.M.; Amoussa, A.M.O.; Bashari, M.; Abid, M.; Hashim, M.M. Application of Chitosan-based Apple Peel Polyphenols Edible Coating on the Preservation of Strawberry ( Fragaria Ananassa Cv Hongyan) Fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıtaş, S.; Duman, H.; Karav, S. Nutritional and Functional Aspects of Fermented Algae. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 5270–5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıtaş, S.; Duman, H.; Pekdemir, B.; Rocha, J.M.; Oz, F.; Karav, S. Functional Chocolate: Exploring Advances in Production and Health Benefits. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 5303–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, R.; Shahdadian, F.; Bagherniya, M.; Karav, S.; Sahebkar, A. Nutritional Factors and Physical Frailty: Highlighting the Role of Functional Nutrients in the Prevention and Treatment. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotirić Akšić, M.; Nešović, M.; Ćirić, I.; Tešić, Ž.; Pezo, L.; Tosti, T.; Gašić, U.; Dojčinović, B.; Lončar, B.; Meland, M. Polyphenolics and Chemical Profiles of Domestic Norwegian Apple (Malus × Domestica Borkh.) Cultivars. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 941487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Grover, K.; Dhillon, T.S.; Kaur, A.; Javed, M. Evaluation of Polyphenols Enriched Dairy Products Developed by Incorporating Black Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) Concentrate. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E.; Sarıtaş, S.; Duman, H.; Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. Polyphenols: Secondary Metabolites with a Biological Impression. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigni, N.B.; Aranibar, C.; Lucini Mas, A.; Aguirre, A.; Borneo, R.; Wunderlin, D.; Baroni, M.V. Chemical Profile and Bioaccessibility of Polyphenols from Wheat Pasta Supplemented with Partially-Deoiled Chia Flour. LWT 2020, 124, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, M.C.; Vignola, M.B.; Paesani, C.; León, A.E. Berry Fruits-enriched Pasta: Effect of Processing and in Vitro Digestion on Phenolics and Its Antioxidant Activity, Bioaccessibility and Potential Bioavailability. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 2104–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazi, M.; Houghton, M.J.; Nicolotti, L.; Murray, M.; Cardoso, B.R.; Williamson, G. Inhibition of Human Starch Digesting Enzymes and Intestinal Glucose Transport by Walnut Polyphenols. Food Res. Int. 2024, 189, 114572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzima, K.; Putsakum, G.; Rai, D.K. Antioxidant Guided Fractionation of Blackberry Polyphenols Show Synergistic Role of Catechins and Ellagitannins. Molecules 2023, 28, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.-T.; Huang, J.; Wong, H.-C.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Metabolic Fate of Black Raspberry Polyphenols in Association with Gut Microbiota of Different Origins in Vitro. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif Zadeh, N.; Zeppa, G. Recovery and Concentration of Polyphenols from Roasted Hazelnut Skin Extract Using Macroporous Resins. Foods 2022, 11, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Jaramillo, C.; Gomez-Delgado, E.; López-Córdoba, A. Improvement of the Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Welsh Onion (Allium Fistulosum) Leaves Using Response Surface Methodology. Foods 2022, 11, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Kong, F. Enzyme Inhibitory Activities of Phenolic Compounds in Pecan and the Effect on Starch Digestion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, N.; Hussain, A.I.; Kamal, G.M.; Manzoor, S.; Fatima, T.; Alswailmi, F.K.; Ahmad, A.; Alsuwayt, B.; Abdullah Alnasser, S.M. Antioxidant, Anti-Obesity, and Hypolipidemic Effects of Polyphenol Rich Star Anise (Illicium Verum) Tea in High-Fat-Sugar Diet-Induced Obesity Rat Model. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, C.; Xue, Z.; Kou, X. Investigation on the Biological Activity of Anthocyanins and Polyphenols in Blueberry. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Hernández, D.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.D.C.; Escobedo-Reyes, A.; Mojica, L. Black Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Polyphenolic Extract Exerts Antioxidant and Antiaging Potential. Molecules 2021, 26, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, R.; Francis, N.; Blanchard, ChristopherL.; Santhakumar, AbishekB. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Chickpea Hull Phenolic Extracts. Food Biosci. 2021, 40, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Gracia, B.; Laya Reig, D.; Rubio-Cabetas, M.J.; Sanz García, M.Á. Study of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Spanish Almonds. Foods 2021, 10, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechchate, H.; Es-safi, I.; Conte, R.; Hano, C.; Amaghnouje, A.; Jawhari, F.Z.; Radouane, N.; Bencheikh, N.; Grafov, A.; Bousta, D. In Vivo and In Vitro Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Flax (Linum Usitatissimum L.) Seed Polyphenols. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aty, A.M.; Elsayed, A.M.; Salah, H.A.; Bassuiny, R.I.; Mohamed, S.A. Egyptian Chia Seeds (Salvia Hispanica L.) during Germination: Upgrading of Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant, Antibacterial Properties and Relevant Enzymes Activities. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Becerril, M.; Gijón, D.; Angulo, M.; Vázquez-Martínez, J.; López, M.G.; Junco, E.; Armenta, J.; Guerra, K.; Angulo, C. Composition, Antioxidant Capacity, Intestinal, and Immunobiological Effects of Oregano (Lippia Palmeri Watts) in Goats: Preliminary in Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Thi, N.Q.N.; Thi, C.Q.N.; Truc, T.T.; Nghi, P.T.B. Studies on Chemical, Polyphenol Content, Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Sweet Basil Leaves (Ocimum Basilicum L.). IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1092, 012083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.; Elmosallamy, A.; Abdel-Hamid, N.; Srour, L. Identification of Polyphenolic Compounds and Hepatoprotective Activity of Artichoke (Cynara Scolymus L.) Edible Part Extracts in Rats. Egypt. J. Chem. 2020, 63, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H.A.C.O.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P.; Jayatilake, S. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity and Polyphenolic Content of Commonly Consumed Egg Plant Varieties and Spinach Varieties in Sri Lanka. Asian J. Res. Biochem. 2020, 7, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Refai, A.A.; Sharaf, A.M.; Azzaz, N.A.E.; El-Dengawy, M.M. Antioxidants and Antibacterial Activities of Bioactive Compounds of Clove (Syzygium Aromaticum) and Thyme (Tymus Vulgaris) Extracts. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2020, 11, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-Q.; Cheng, L.-Z.; Zhang, T.; Yaron, S.; Jiang, H.-X.; Sui, Z.-Q.; Corke, H. Phenolic Profiles, Antioxidant, and Antiproliferative Activities of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa). Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 152, 112561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhanfezova, T.; Barba-Espín, G.; Müller, R.; Joernsgaard, B.; Hegelund, J.N.; Madsen, B.; Larsen, D.H.; Martínez Vega, M.; Toldam-Andersen, T.B. Anthocyanin Profile, Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolic Content of a Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa Duch) Genetic Resource Collection. Food Biosci. 2020, 36, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitouni, H.; Hssaini, L.; Ouaabou, R.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Hernández, F.; Ercisli, S.; Ennahli, S.; Messaoudi, Z.; Hanine, H. Exploring Antioxidant Activity, Organic Acid, and Phenolic Composition in Strawberry Tree Fruits (Arbutus Unedo L.) Growing in Morocco. Plants 2020, 9, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polewski, M.A.; Esquivel-Alvarado, D.; Wedde, N.S.; Kruger, C.G.; Reed, J.D. Isolation and Characterization of Blueberry Polyphenolic Components and Their Effects on Gut Barrier Dysfunction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 2940–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun, N.; Sarıtaş, S.; Jaouhari, Y.; Bordiga, M.; Karav, S. The Impact of Freeze Drying on Bioactivity and Physical Properties of Food Products. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity of Citrus Fiber/Blackberry Juice Complexes. Molecules 2021, 26, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhanfezova, T.; Barba-Espín, G.; Müller, R.; Joernsgaard, B.; Hegelund, J.N.; Madsen, B.; Larsen, D.H.; Martínez Vega, M.; Toldam-Andersen, T.B. Anthocyanin Profile, Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolic Content of a Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa Duch) Genetic Resource Collection. Food Biosci. 2020, 36, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechchate, H.; Es-safi, I.; Conte, R.; Hano, C.; Amaghnouje, A.; Jawhari, F.Z.; Radouane, N.; Bencheikh, N.; Grafov, A.; Bousta, D. In Vivo and In Vitro Antidiabetic and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Flax (Linum Usitatissimum L.) Seed Polyphenols. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Kaushik, D.; Shubham, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Oz, E.; Brennan, C.; Zeng, M.; Proestos, C.; Çadırcı, K.; et al. Ferulic Acid: Extraction, Estimation, Bioactivity and Applications for Human Health and Food. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, jsfa.13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobori, R.; Yakami, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Saito, A. Changes in the Polyphenol Content of Red Raspberry Fruits during Ripening. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego, I.; Brito, B.; Viera, W.; Cabrera, A.; Llerena, W.; Kannangara, T.; Vilcacundo, R.; Angós, I.; Carrillo, W. Influence of the Maturity Stage on the Phytochemical Composition and the Antioxidant Activity of Four Andean Blackberry Cultivars (Rubus Glaucus Benth) from Ecuador. Plants 2020, 9, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, R.; Hashimoto, S.; Koshimizu, H.; Kawasaki, T.; Saito, A. Changes in Polyphenol Content in Raspberry by Cultivation Environment. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 333, 07013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, C.; Bruaut, M.; Chalot, G.; Cottet, V. Impact of Maturity Stage at Harvest on the Main Physicochemical Characteristics, the Levels of Vitamin C, Polyphenols and Volatiles and the Sensory Quality of Gariguette Strawberry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Cadi, H.; El Cadi, A.; Kounnoun, A.; Oulad El Majdoub, Y.; Palma Lovillo, M.; Brigui, J.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L.; Cacciola, F. Wild Strawberry (Arbutus Unedo): Phytochemical Screening and Antioxidant Properties of Fruits Collected in Northern Morocco. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 6299–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, F.; Mardones, C.; Fischer, S.; García-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A.; López, M.D. Seasonal Changes in White Strawberry: Effect on Aroma, Phenolic Compounds and Its Biological Activity. J. Berry Res. 2021, 11, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Gracia, B.; Laya Reig, D.; Rubio-Cabetas, M.J.; Sanz García, M.Á. Study of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Spanish Almonds. Foods 2021, 10, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, C.; Codină, G.G.; Héjja, M.; András, C.D.; Chetrariu, A.; Dabija, A. Study of Antioxidant Activity of Garden Blackberries (Rubus Fruticosus L.) Extracts Obtained with Different Extraction Solvents. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuna, R.A.; Mensah, M.-A.S.; Koomson, G.; Akabanda, F.; Dorvlo, S.Y.; Amagloh, F.K. Physico-Functional and Nutritional Characteristics of Germinated Pigeon Pea (Cajanus Cajan) Flour as a Functional Food Ingredient. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Betanzo, J.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; McDonald, J.; Schroeter, K.; Corredig, M.; Paliyath, G. Stability and Biological Activity of Wild Blueberry (Vaccinium Angustifolium) Polyphenols during Simulated in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsetto, P.A.; Montorfano, G.; Zava, S.; Colombo, I.; Ingadottir, B.; Jonsdottir, R.; Sveinsdottir, K.; Rizzo, A.M. Characterization of Antioxidant Potential of Seaweed Extracts for Enrichment of Convenience Food. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, N.; Zhang, X.; Meng, X. Effect of in Vitro -simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion on the Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Blueberry Polyphenols and Their Cellular Antioxidant Activity towards HepG2 Cells. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumovski, N.; Blades, B.; Roach, P. Food Inhibits the Oral Bioavailability of the Major Green Tea Antioxidant Epigallocatechin Gallate in Humans. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejbuk, M.; Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. Dietary Polyphenols, Food Processing and Gut Microbiome: Recent Findings on Bioavailability, Bioactivity, and Gut Microbiome Interplay. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Velázquez, O.A.; Mulero, M.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, E.O.; Mondor, M.; Arcand, Y.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion Impact on Stability, Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenols from Wild and Commercial Blackberries ( Rubus Spp.). Food Funct. 2021, 12, 7358–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, D. Effects of Nano-Chitosan and Chitosan Coating on the Postharvest Quality, Polyphenol Oxidase Activity and Malondialdehyde Content of Strawberry (Fragaria x Ananassa Duch.). J. Hortic. Postharvest Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaderides, K.; Mourtzinos, I.; Goula, A.M. Stability of Pomegranate Peel Polyphenols Encapsulated in Orange Juice Industry By-Product and Their Incorporation in Cookies. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-Orbea, G.L.; García-Villalba, R.; Bernal, M.J.; Hernández, A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M. Stability of Phenolic Compounds in Apple and Strawberry: Effect of Different Processing Techniques in Industrial Set Up. Food Chem. 2023, 401, 134099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-T.; Li, W.-X.; He, R.-R.; Li, Y.-F.; Tsoi, B.; Zhai, Y.-J.; Kurihara, H. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of a Polyphenols-Rich Extract from Tea ( Camellia Sinensis ) Flowers in Acute and Chronic Mice Models. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antuono, I.; Carola, A.; Sena, L.M.; Linsalata, V.; Cardinali, A.; Logrieco, A.F.; Colucci, M.G.; Apone, F. Artichoke Polyphenols Produce Skin Anti-Age Effects by Improving Endothelial Cell Integrity and Functionality. Molecules 2018, 23, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yathzamiry, V.-G.D.; Cecilia, E.-G.S.; Antonio, M.-C.J.; Daniel, N.-F.S.; Carolina, F.-G.A.; Alberto, A.-V.J.; Raúl, R.-H. Isolation of Polyphenols from Soursop (Annona Muricata L.) Leaves Using Green Chemistry Techniques and Their Anticancer Effect. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2021, 64, e21200163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, E.; Torri, L.; Piochi, M.; Cabrino, G.; Meli, M.A.; De Bellis, R. Nutritional, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties of Functional Beef Burgers Formulated with Chia Seeds and Goji Puree, before and after in Vitro Digestion. Meat Sci. 2020, 161, 108021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savas, B.S.; Akan, E. Oat Bran Fortified Raspberry Probiotic Dairy Drinks: Physicochemical, Textural, Microbiologic Properties, in Vitro Bioaccessibility of Antioxidants and Polyphenols. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayulu, N.; Assa, Y.A.; Kepel, B.J.; Nurkolis, F.; Rompies, R.; Kawengian, S.; Natanael, H. Probiotic Drink from Fermented Mango ( Mangifera Indica ) with Addition of Spinach Flour ( Amaranthus ) High in Polyphenols and Food Fibre. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, E67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucheru, P.; Chege, P.; Muchiri, M. The Potential Health Benefits of a Novel Synbiotic Yogurt Fortified with Purple-Leaf Tea in Modulation of Gut Microbiota. Bioact. Compd. Health Dis. 2024, 7, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Langerijt, T.M.; O’Callaghan, Y.C.; Tzima, K.; Lucey, A.; O’Brien, N.M.; O’Mahony, J.A.; Rai, D.K.; Crowley, S.V. The Influence of Milk with Different Compositions on the Bioavailability of Blackberry Polyphenols in Model Sports Nutrition Beverages. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2023, 76, 828–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Nosić, M.; Pichler, A.; Ivić, I.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Apple Fibers as Carriers of Blackberry Juice Polyphenols: Development of Natural Functional Food Additives. Molecules 2022, 27, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Grover, K.; Dhillon, T.S.; Kaur, A.; Javed, M. Evaluation of Polyphenols Enriched Dairy Products Developed by Incorporating Black Carrot (Daucus Carota L.) Concentrate. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumul, D.; Ziobro, R.; Korus, J.; Kruczek, M. Apple Pomace as a Source of Bioactive Polyphenol Compounds in Gluten-Free Breads. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Cecchi, L.; Innocenti, M.; Bellumori, M.; Mulinacci, N. Food By-Products Valorisation: Grape Pomace and Olive Pomace (Pâté) as Sources of Phenolic Compounds and Fiber for Enrichment of Tagliatelle Pasta. Food Chem. 2021, 355, 129642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirab, B.; Ahmadi Gavlighi, H.; Amini Sarteshnizi, R.; Azizi, M.H.; C. Udenigwe, C. Production of Low Glycemic Potential Sponge Cake by Pomegranate Peel Extract (PPE) as Natural Enriched Polyphenol Extract: Textural, Color and Consumer Acceptability. LWT 2020, 134, 109973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E.; Ozdal, T.; Gok, I. Investigation of Textural, Functional, and Sensory Properties of Muffins Prepared by Adding Grape Seeds to Various Flours. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildner-Szkudlarz, S.; Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R.; Szwengiel, A.; Pacyński, M. Use of Grape By-product as a Source of Dietary Fibre and Phenolic Compounds in Sourdough Mixed Rye Bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.; Tiwari, R.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, S.M.; Kumar, V.; Rautela, I.; Kohli, D.; Rawat, B.S.; Kaushik, R. Utilization of Food Waste for the Development of Composite Bread. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.; Bustamante, A.; Echeverría, F.; Encina, C.; Palma, M.; Sanhueza, L.; Sambra, V.; Pando, M.E.; Jiménez, P. A Feasible Approach to Developing Fiber-Enriched Bread Using Pomegranate Peel Powder: Assessing Its Nutritional Composition and Glycemic Index. Foods 2023, 12, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthachat, W.; Thangsiri, S.; Khemthong, C.; On-Nom, N.; Chupeerach, C.; Sahasakul, Y.; Temviriyanukul, P.; Suttisansanee, U. Green Extraction of Hodgsonia Heteroclita Oilseed Cake Powder to Obtain Optimal Antioxidants and Health Benefits. Foods 2023, 12, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasevičienė, Ž.; Čechovičienė, I.; Paulauskienė, A.; Gumbytė, M.; Blinstrubienė, A.; Burbulis, N. The Effect of Berry Pomace on Quality Changes of Beef Patties during Refrigerated Storage. Foods 2022, 11, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Juhaimi, F.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; Özcan, M.M.; Albakry, Z. Effect of Enriching with Fermented Green Olive Pulp on Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activities, Phenolic Compounds, Fatty Acids and Sensory Properties of Wheat Bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 3860–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Ionica, M.E.; Trandafir, I. Bread Enriched in Lycopene and Other Bioactive Compounds by Addition of Dry Tomato Waste. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 8260–8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, D.; Picone, P.; Lozano Sanchez, J.; Borras-Linares, I.; Guiducci, A.; Muscolino, E.; Giacomazza, D.; Sanfilippo, T.; Guggino, R.; Bulone, D.; et al. Recovery from Food Waste—Biscuit Doughs Enriched with Pomegranate Peel Powder as a Model of Fortified Aliment. Biology 2022, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food | Polyphenols | Extraction methods | Studied effect or property of food polyphenols | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Walnut |

-Ellagic acid -strictinin -3-Methoxy-5,7,3′,4′-tetrahydroxy-flavon -gallic acid -ellagic acid pentoside, etc,. |

-Folin–Ciocalteu method for total phenolic content -Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography high-resolution Fourier transform mass spectrometry to identify polyphenols -100 % hexane (1:10 w/v) as extractant |

Exhibit inhibition of human intestinal glucose transport, human α-glucosidase activities, and human salivary and pancreatic α-amylases | [58] |

|

Blackberry |

-Anthocyanins -Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, -cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside -Ellagitannins -Catechins etc. |

-Flash chromatography and mass spectrometry - 70% acetone as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [59] |

| Black raspberry |

-Cyanidin-3, 5-O-diglucoside -Pedunculagin/casuariin -Caffeoyl-hexoside -Sanguiin H-6, etc. |

-Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry/ mass spectrometry -The divergent percentage of Methanol, acetone, and ethanol with 30% water |

Exhibit health-promoting effect on gut microbiota | [60] |

| Red Onion Peels |

-Benzoic acid -Rosmarinic acid -Quercetin -Rutin -Pyrogallol -Quercetin -Quercetin derivatives -ρ-Coumaric acid |

-High-performance liquid chromatography analysis -Ultrasound- and enzymatic-assisted extractions with 80% ethanol |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [10] |

|

Lentil (Lens culinaris) |

-Total phenolic compounds | -Folin–Ciocalteu for total phenolic content -Acetone: water (80 : 20 v/v) as an extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [13] |

|

Raspberry Flower Petals |

-(+)-catechin -(−)-epicatechin -Procyanidin B4 -Procyanidin C3 -Sanguiin H-6 -Lambertianin C -(−)-epicatechin-3,5-di-O-gallate -Kaempferol-7-O-glucoside -Naringenin-7-O-glucoside, etc,. |

-High-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to identify polyphenols -The Folin–Ciocalteu method for total polyphenol content -Methanol as an extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity, lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity, and inhibitory activity against cervical cancer (HeLa S3) cells |

[14] |

|

Chinese raspberry |

-Gallic acid -Epicatechin -Ellagic acid -Rutin -Quercetin 3-O-glucoside -Avicularin -Kaempferol-7-O-glucuronide -Quercetin-7-O-glucuronide, etc,. |

-High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -A method that used acidic methanol (1% [v/v] HCl) for total anthocyanin content -The Al (NO3)3–NaOH assay for total flavonoid content -Folin-Ciocalteu’s total polyphenol content colorimetric method for -70% (V/V) ethanol solution as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity and cytotoxic effect |

[15] |

| Roasted hazelnut skin | -Gallic acid -Protocatechuic acid -Catechin -Epicatechin -Quercetin |

-Spectrophotometry for total polyphenolic content -High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -Pure ethanol as an extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [61] |

|

Welsh Onion (Allium fistulosum) leaves |

-Total phenolic content -Total anthocyanin content -Especially Cyanidin and quercetin-3-glucoside |

-Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization positive mode-orbitrap mass spectrometry analysis -70% v/v ethanol as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [62] |

|

Pecan |

-Total phenolic content | -Folin-Ciocaulteu’s method for total phenolic content -Acetone/deionized water/acetic acid (70:29.5:0.5, v/v/v) at a ratio of 6:10 (w/v) as extractant |

Exhibit α-Amylase inhibitory, and α-Glucosidase inhibitory effects in starch digestion |

[63] |

| Star anise (Illicium verum) | -Gallic acid -4-Hydroxybenzoic acid -Catechin -Chlorogenic acid -Caffeic acid -Syringic acid -Vanillic acid -p-Coumaric acid -Salicylic acid -Rutin, etc. |

-High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -Distilled water as an extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant, anti-Obesity, and hypolipidemic effects |

[64] |

| Domestic Norwegian Apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) | -Chlorogenic acid -3-O-caffeoylquinic acid -Phlorizin -Quercetin 3-O-glucoside -Quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside -5-O-caffeoylquinic acid -phloretin |

-Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system-linear trap quadrupole to identify polyphenols -Acidified methanol/water solution (70/30 with 0.1% hydrochloric acid to pH 2) as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [53] |

| Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) | -Delphinidin-3-glucoside -Quercetin 3-O-galactoside -Pelargonidin-3-O-galactoside -Malvidin-3-O-glucose -Phenylpropanoid com-pound chlorogenic acid isomers -Flavonoid substance epicatechin gallate -Kaempferol-3-rhamnoside |

-High-performance liquid chromatography analysis and mass spectrometry -Acidified methanol (0.3% HCl [v/v]) as the main extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity, antitumor activity, and immune function of anthocyanins | [65] |

|

Black Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) |

-Malvidin-3-glucoside -Cyanidin-3-glucoside -Delphinidin-3-glucoside -petunidin-3-O-β glucoside -Catechin -Delphinidin 3-Glucoside -Myricetin -Sinapic acid, etc. |

-Folin–Ciocalteu’s method for polyphenols -pH differential method (AOAC Official Method 2005.02) for total anthocyanins -Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry analysis to identify phenolic compounds -Ethanol-water (50:50 v/v) as an extractant in supercritical fluid extraction |

Exhibit antioxidant activity and anti-aging potential |

[66] |

|

Chickpea hull |

- Gallic acid - Rutin, etc. |

-Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -Acetone, water, and acetic acid (70:29.5:0.5, v/v/v) as extractant |

Exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. | [67] |

|

Spanish Almonds |

-(+)-Catechin -(−)-Epicatechin -Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside -Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside -Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside -Sum Flavan-3-ols -Sum Flavanols |

-Spectrophotometric techniques with the modified Folin-Ciocalteu method for total polyphenol determination -Zhishen, Meng Cheng, and Jianming method that was modified by Jahanbani-Esfahlan and Jamei for total flavonoid determination -Ribéreau-Gayon and Stonestreet for total proanthocyanidin determination -Hydrochloric acid, water, and methanol (3.7:46.3:50, v/v/v) solution as extractant |

Exhibit the antioxidant activity | [68] |

|

Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) Seed |

-Oleocanthal -Oleuropein -Hesperetin -Ursolic acid -Amentoflavone -Quercetin-3-O-glucoside -Quercetin-3-O-glucuronic acid -Kaempferol-3-O-glucose -Quercetin-3-O-hexose-deoxyhexose, etc,. |

-Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry analysis to identify polyphenols -70% methanol as extractant |

Exhibit antidiabetic effect, anti-inflammatory effect, α-Amylase inhibitory activity, and α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity. |

[69] |

| Egyptian chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds | -Gallic acid -Protocatechuic acid -p-hydroxybenzoic acid -Chlorogenic acid -Catechin -Quercetin -Apigenin -Kaempferol |

-Distilled water, NaNO2, 10% AlCl3, and 1.0 M NaOH in a method used for total flavonoid content -Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolic content -High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -80% methanol as extractant |

Exhibit antimicrobial effect and antioxidant activity | [70] |

| Oregano (Lippia palmeri Watts) | -Total polyphenol content -Total flavonoid content |

-The Folin-Ciocalteu method for total polyphenol content -The method based on aluminum chloride for total flavonoid content -Ethanol (100%) as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity, intestinal and immunobiological effects | [71] |

| Sweet basil leaves (Ocimum basilicum L.) | -Tannins -Flavonoids |

-Phytochemical analysis to detect secondary metabolites -The Folin-Ciocalteu method for total polyphenol content -The method based on aluminum chloride for total flavonoid content -Ethanol 70% as an extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [72] |

|

Raspberry leaf |

-Quercetin -Kaempferol -Procyanidin B1 -Catechin -Epicatechin -Gallic acid -Chlorogenic acid -p-Coumaric acid -Protocatechuic acid -Caffeic acid, etc. |

-High-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometer to identify polyphenols -60% ethanol as extractant with ultrasonic power |

Exhibit anti-pathogen activity and intestinal health | [1] |

|

Artichoke |

-Luteolin -Luteolin-O-glycoside -Luteolin-7-O-rutinoside -Apigenin, etc. |

-High-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry -High-Performance Liquid Chromatography, methanol as extractant |

Exhibit hepatoprotective activity |

[73] |

|

Egg Plant Varieties and Spinach Varieties |

-Total phenolic content -Total flavonoid content |

-Methanolic extraction by using methanol/water (80%, v/v) as an extractant | Exhibit antioxidant activity | [74] |

| Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and Thyme (Thymus vulgaris) | -Total phenolic content -Total flavonoid compounds |

-Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolic compounds -Aluminum chloride colorimetric method for total flavonoid compounds -95% ethyl alcohol as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant and antibacterial activities. | [75] |

| Turmeric (Curcuma longa) | -Gallic acid -Epicatechin -Protocatechuic acid -Catechin -Chlorogenic acid -Ferulic acid -Coumarin -Rutin, etc. |

-The Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolic content -High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols - Ethanol (80%) as an extractant in ultrasound-assisted and conventional solvent extraction |

Exhibit antioxidant and antiproliferative activities | [76] |

| Strawberry | -Pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside and Pelargonidin-derivative -Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside and cyanidin-derivative -Gallic acid |

-pH differential method for total monomeric anthocyanin content -High-performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection for anthocyanins -Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolic content -70% ethanol as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activity | [77] |

| Young apple | -Procyanidin B1 -(-)-Epigallocatechin -(+)-Catechin -Procyanidin B2 -Chlorogenic acid -4-p-coumaroylquinic acid -(-)-Epicatechin -Caffeic acid -Quercetin, etc. |

-High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -The Folin-Ciocalteu method for total polyphenol content -70% ethyl alcohol solution as extractant |

Exhibit α-glucosidase inhibitory effect | [9] |

| Strawberry Tree Fruits (Arbutus unedo L.) | -Rutin -Cyanidin-3-glucoside -Quercetin-3-Xylosidase -Cyanidin-30.5-diglucoside -Quercetin-3-galactoside, etc,. |

-High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -The method based on aluminum chloride for total flavonoid content -Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenol content -pH differential method for total anthocyanins -Acetone/water (70:30, v/v) as extractant |

Exhibit antioxidant activities |

[78] |

| Highbush blueberries | -Total polyphenol fraction -Anthocyanin-enriched fraction -Proanthocyanidin-enriched fraction | -High-performance liquid chromatography -70% (v/v) acetone as main extractant After acetone extraction - Methanol for the total polyphenol fraction - 50% (v/v) ethanol for anthocyanin-enriched fraction -80% (v/v) acetone for proanthocyanidin-enriched fraction |

Exhibit antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. | [79] |

| Red Raspberry | -Quercetin -Myricetin -Ellagic acid -(+)-Catechin -(−)-Epicatechin -Cyanidin 3-O-β-d-glucoside -Cyanidin 3-O-β-d-glucoside equivalent |

-High-performance liquid chromatography to identify polyphenols -Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolic content -Acidified methanol (0.5% acetic acid) as an extractant |

Exhibit the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation | [3] |

| Product types | Polyphenols | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purple tea fortification of probiotic yogurt | -Polyphenols -Catechins -AA Theamine -Anthocyanins |

-The tea polyphenols did not affect the probiotics in storage -Increased the beneficial bacteria -Decreased the pathogens in gut microbiota |

[109] |

| Microencapsulated Asiatic Pennywort (Centella asiatica) fortified chocolate oat milk beverage | -Asiatic acid -Asiaticoside -Benzoic acid -Caffeic acid -Catechin -Chlorogenic acid -Gallic acid -Kaempferol -Luteolin -Madecassic -p-Coumaric acid -Quercetin -Rutin |

-Preserved the polyphenolic ingredients of the food | [36] |

| Polyphenol enriched milk | -Rutin -Cyanidin-3-rutinoside -Procyanidin B1 -Delphinidin-3-rutinoside -Gallic acid, etc. |

-Increased the bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity of food ingredients | [48] |

| Sports nutrition milk enriched with blackberry | -Phenolics -Flavonoids -Anthocyanins |

-Enhanced the bioaccessibility of the polyphenols of the blackberry and the protection of anthocyanins in digestion | [110] |

| Blackberry juice with apple fibers | -Anthocyanins -Flavanols -Phenolic acids -Dihydrochalcones |

-Showed high antioxidant activity and inhibition of α-amylase enzymes | [111] |

| Apple pomace enriched beef burger | -Chlorogenic acid -Quercetin-3-O-glucoside -Phloridzin |

-Demonstrated the high total phenol content, antioxidant activity, and antioxidant compounds, including quercetin derivatives, chlorogenic acid, and phloridzin in the enriched beef burger | [35] |

| Oat bran fortified raspberry probiotic dairy drinks | -Phenolic acids -Flavonoids -Phytic acid, etc. |

-Did not cause any negative effect on the polyphenolic ingredients of functional food in storage | [107] |

| Fermented mango (Mangifera indica) and spinach flour (Amaranthus) enriched probiotic drink | -Quercetin -Kaempferol |

-Improved lipid profiles -Stabilized blood sugar fluctuations so that they can be anti-diabetics |

[108] |

| Polyphenols enriched ice cream, yogurt, and buttermilk with black carrot (Daucus carota L.) concentrate | -Total phenols -Total flavonoids -Anthocyanins |

-Enhanced the mineral content (Mg and Fe), polyphenols, and antioxidant activity of dairy products | [112] |

| Gluten-free breads enriched with apple pomace | -Luteolin 6-C-hexoside O-hexoside -Chlorogenic acid -(+) catechin -Phloretin-2-O-xylosyl-glucoside, etc. |

-Improved the nutritional value of the bread in terms of especially polyphenols -Demonstrated high antioxidant activity and polyphenolic ingredients |

[113] |

| Spent Coffee Grounds-Enriched Cookies | -Melanoidins -Chlorogenic acid -5-caffeoylquinic acid -Phenolic acids, etc. |

-Improved the polyphenolic ingredients of the food -Enhanced the bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity of the cookies |

[7] |

| Pollen-enriched goat milk | -5-O-caffeoylquinic acid -Quercetin-3-O-glucoside -Apigenin -Kaempferol-7-O-glucoside, etc. |

-Enhanced the antioxidant activity and bioaccessibility in digestion | [33] |

| Olive leaves and olive mill wastewater-enriched gluten-free breadsticks | -Total polyphenol content | -Demonstrated antioxidant activity and high polyphenol bioaccessibility in the breadsticks | [30] |

| Grape pomace and olive pomace enriched tagliatelle pasta | -Quercetin -Kaempferol -Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside -Petunidin-3-O-glucoside, etc. |

-Improved the nutritional value of the food | [114] |

|

Functional beef burgers formulated with chia seeds and goji pure

e |

-Carotenoids -Chlorogenic acid -Caffeic acids -Quercetin -Kaempferol |

-Enhanced bioaccessibility of polyphenols | [106] |

| Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) polyphenol-enriched sponge cake | -Phenolic acids -Flavonoids -Gallotannins -Ellagitannins |

-Enhanced the nutritional value and total phenolic ingredient -Inhibition of α-Glucosidase and α-amylase -Showed high digestibility ability |

[115] |

| Rye snacks enriched with seaweed extract | -Total phenolic content | -Enriched antioxidant activity, oxidative stability ability, and preventive effect from diseases -Promoted the enhancement of the nutritional value and preservation of convenience food |

[95] |

| Enriched Apple Snacks with Grape Juice |

-Cyanin -Catechin -Epicatechin -Epigallocatechin -Quercetin, etc. |

-Improved the polyphenolic ingredients of the product -Demonstrated high antioxidant capacity and bioaccessibility of the polyphenols in the digestion of the snacks |

[4] |

| Olive leaf extract-enriched taralli | -Total Phenols -Total Flavonoids -Oleuropein, etc. |

-Increased the bioaccessibility of the nutritional contents and antioxidant activity of the food | [40] |

| Partially deoiled chia flour-enriched wheat pasta | -Quinic acid -Caffeic acid -Ferulic acid -Methylquercetin, etc. |

-Improved nutritional value -Enhanced bioaccessibility in digestion |

[56] |

| Wheat bread enriched with onion extract | -Quercetin 4’-O-glucoside -Quercetin -Total flavonols -Total polyphenol content |

-Demonstrated the high antioxidant activity and polyphenolic ingredients in storage | [41] |

| Berry fruits-enriched pasta | -Total polyphenol content -Anthocyanins |

-Enhanced the nutritional value, bioaccessibility, antioxidant activity, and bioavailability of the pasta | [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).