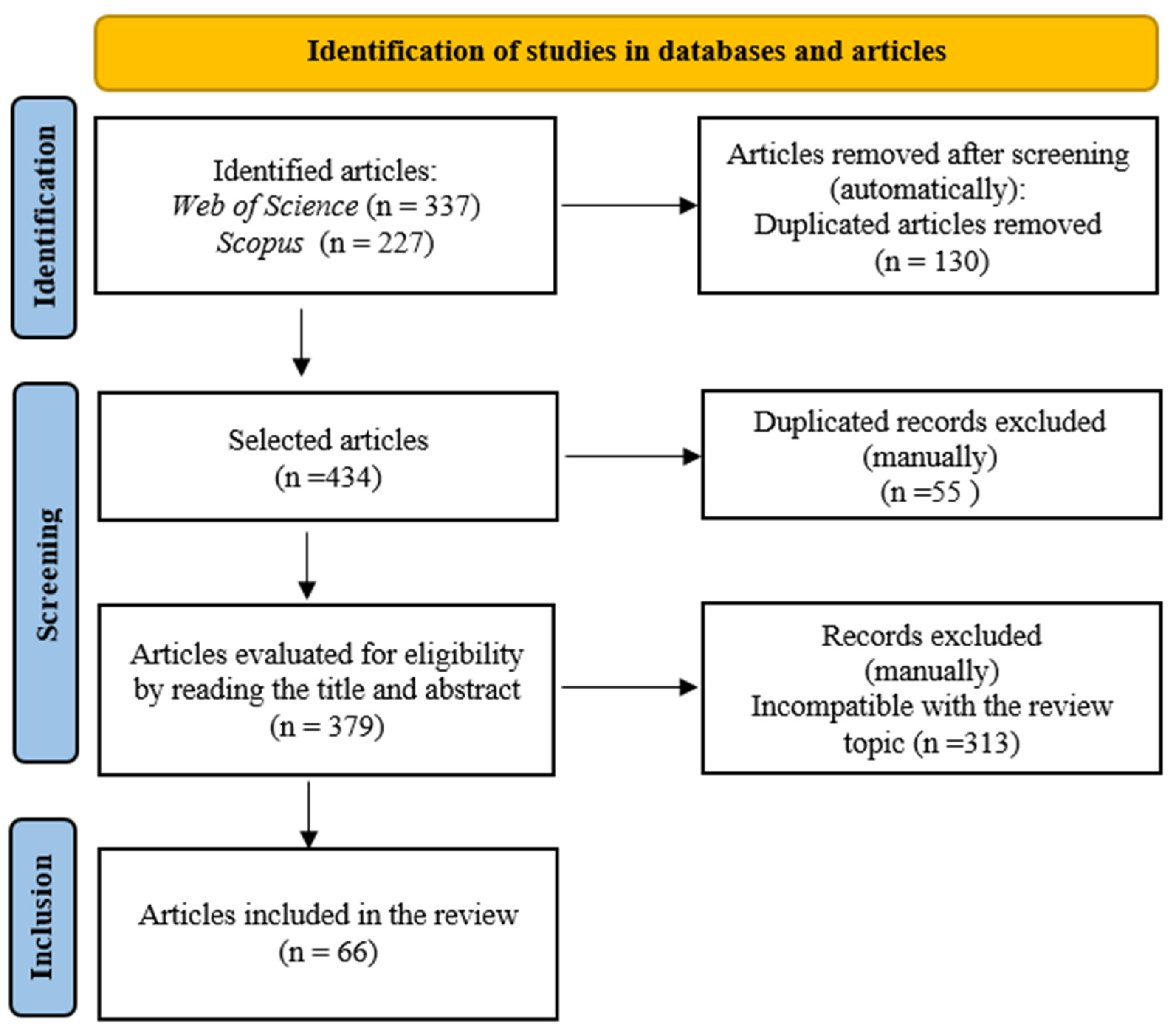

3.1. Characteristics of the Articles

The 10 most cited articles [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] stood out among the 66 selected articles, predominating in the homegarden agroforestry (HAF) or household garden topic. These articles address the composition, diversity, and richness of plants, the medicinal use of plant resources, and agrobiodiversity. The 66 selected articles were published between 1996 and 2023, across 42 journals, with an annual publication growth rate of 1.5% and a mean citation count of 19.5 per article. The articles were authored by 230 researchers, with an average of 3.8 co-authors per article; only three articles had a single author, and 38.0% featured international co-authorship. A total of 254 unique keywords were identified in the articles, with 215 words classified as the most frequent in titles and abstracts (

words plus).

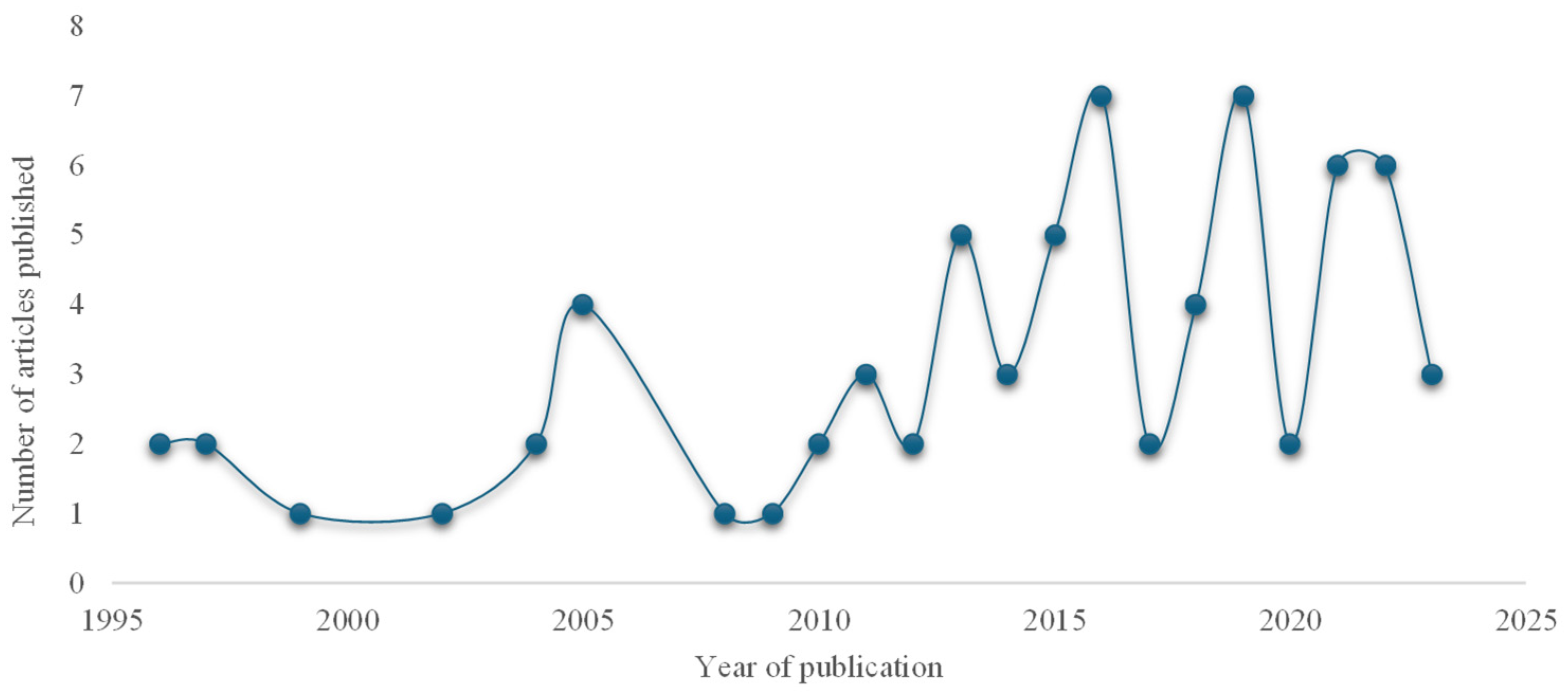

The number of published articles exhibited annual fluctuations (

Figure 2). Production peaks were identified in 2016, 2019, 2021, and 2022, with six or seven articles published per year, and a significantly low production between 2008 and 2012. This suggests the occurrence of catalyzing events that either stimulate or discourage research, including the emergence of new areas, climatic events, global discussions, financing availability, and social or policy issues influencing research. Therefore, the scientific production surveyed in this review does not seem to follow a growth or decline pattern, suggesting that other factors are influencing the number of published studies.

The 19 research institutions with the highest number of articles associated with them (ranging from 3 to 14 articles) include Brazil with six, Canada and Germany with three, the United States and Ecuador with two, and Colombia, Spain, and the Netherlands with one article each. The institutions with the highest number of published studies are Wageningen University and Research (14 articles) and the National Institute for Amazon Research (12 articles).

In addition, the Federal Rural University of the Amazon in Brazil and the University of Saskatchewan in Canada published nine articles each; McGill University, also in Canada, published six articles; and the University of Florida, in the United States, published five articles. McGill University was the institution with the oldest published study (since 1996), but had no new publications after 2008. The universities of Koblenz and Landau in Bonn and Hamburg (Germany), the Maranhão and São Paulo State Universities (Brazil), and the National University of Colombia (Colombia) published four articles each. The other institutions recorded three published articles each, namely: Mamirauá Sustainable Development Institute and Federal University of Western Pará (Brazil), National Institute for Agricultural Investigations and Central University of Ecuador (Ecuador), University of Miami (United States), Autonomous University of Barcelona (Spain), and the University of British Columbia (Canada).

The most productive institutions in Brazil were the National Institute for Amazon Research, the Federal Rural University of the Amazon, Maranhão State University, Mamirauá Sustainable Development Institute, and the Federal University of Western Pará, all located in the Brazilian Amazon, as well as the University of São Paulo, in São Paulo.

The general analysis of published studies and their origins indicates a prominence of institutions headquartered outside the Amazon, a reduced participation of institutions from countries within this biome, including Brazil, Ecuador, and Colombia, and absence of institutions from other Latin American countries. The prominence of foreign institutions in research on the Amazon biome is primarily attributed to factors related to research internationalization, broad contribution networks, available financing, and research promotion.

3.2. Frequent Terms in the Published Studies

Regarding the trend topics, 215 expressions or words were identified as the most frequent in titles and abstracts of articles published from 2004 to 2020. This indicates that there were insufficient mentions in articles published outside this period to reach the minimum frequency of five mentions required for inclusion in this group. The most frequently mentioned trend topics in the more recent studies (from 2013 onwards) include conservation (15 occurrences), biodiversity, diversity, management, and forest (12.5 occurrences). This indicates a growing trend in studies emphasizing management and environmental indicators of AFS. Other prominent terms include systems, agroforestry, and agroforestry systems, which together have the highest frequency (above 15). Similarly, homegardens and home gardens, together account for 12 occurrences. In contrast, agriculture, with fewer occurrences (five mentions), is spread over a longer period (2004 to 2018), indicating constancy.

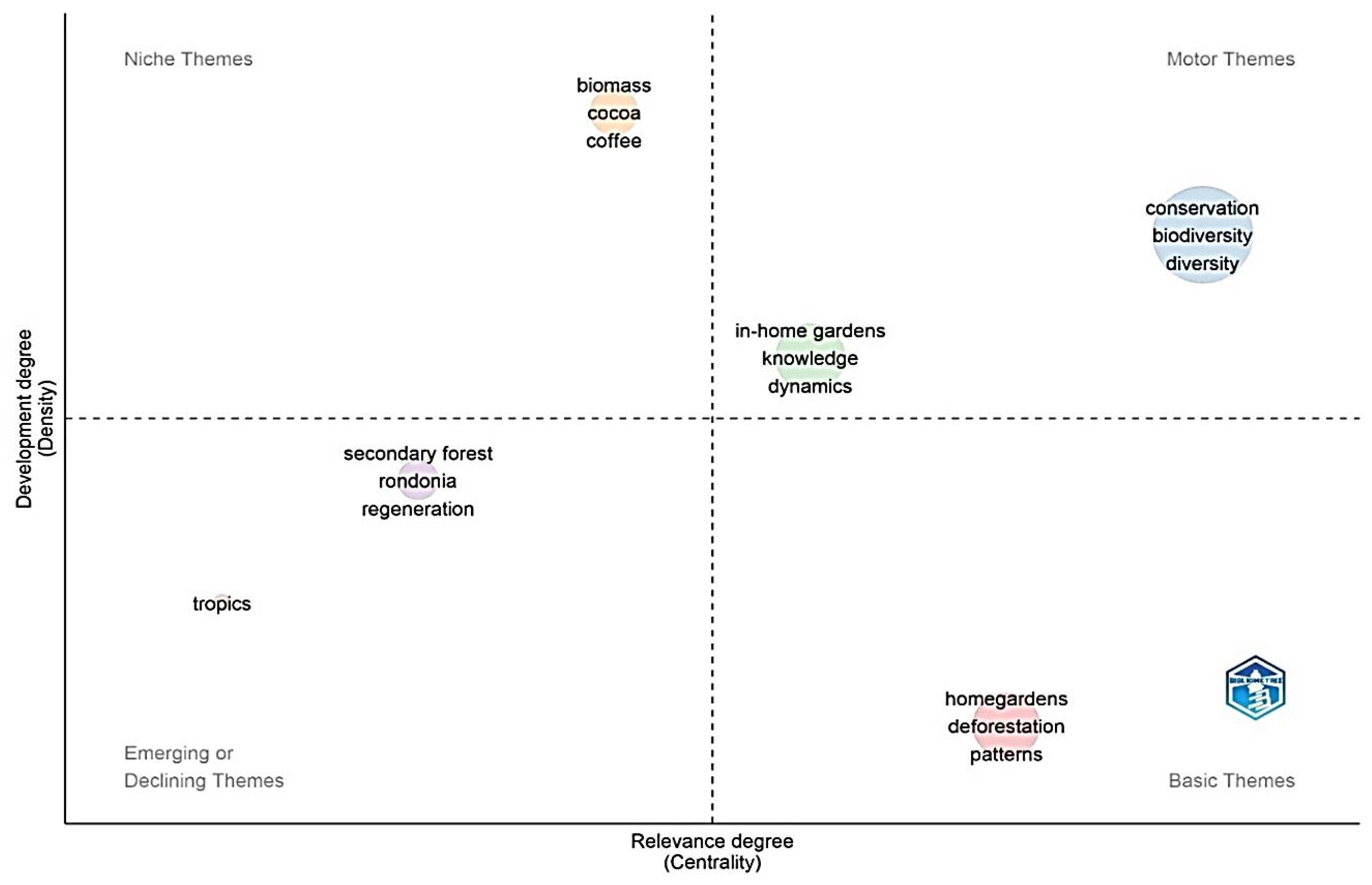

A thematic map was created based on the standout keywords in the articles (

words plus). The map included the most consistent terms from the articles, forming six clusters with the 16 most frequent words (

Figure 3), distributed across two axes: density and centrality. These axes illustrate the importance of highlighted topics within the scope studied. The two clusters inserted in

Motor Themes showed high density and centrality, suggesting that the articles with these topics align most closely with the focus of the scope review. The largest group, containing the terms

conservation,

biodiversity, and

diversity, was in this quadrant. This cluster highlights the connection between AFS and discussions on cultivation, landscape, and richness.

The second cluster, also located in the same quadrant, included the terms in-home gardens, knowledge, and dynamics, representing other keywords linked to shade plant diversity, composition, and agrobiodiversity. These terms demonstrated higher centrality in the review, highlighting areas that require further research and suggesting a possible information gap

.

Homegardens, another term referring to HAF, is in the lower-right quadrant under Basic Themes, forming a cluster with deforestation and patterns. This cluster indicates that these terms have low density but high centrality, suggesting that they are essential to the study area but may be not fully investigated or are broad concepts.

The terms

biomass,

cocoa, and

coffee formed a cluster located in the upper-left quadrant under

Niche Themes, representing topics with high density but low centrality. This indicates that, while well-researched, these terms are not central to the research focus, as they are specialized topics within the review scope. Studies in this quadrant focus on composition or diversity of AFS but are more focused on explaining other parameters, such as assessing the ecological relationship between floristic composition and soil properties within a cacao AFS with a short fallow period [

23].

Emerging or Declining Themes, located in the lower-left quadrant, included the terms

secondary forest,

Rondônia, and

regeneration, forming a cluster, and

tropics, forming another (

Figure 3). These groups exhibit low density and centrality in the research, suggesting that they may be emerging terms and thus infrequently used, or they could be becoming less prominent in research.

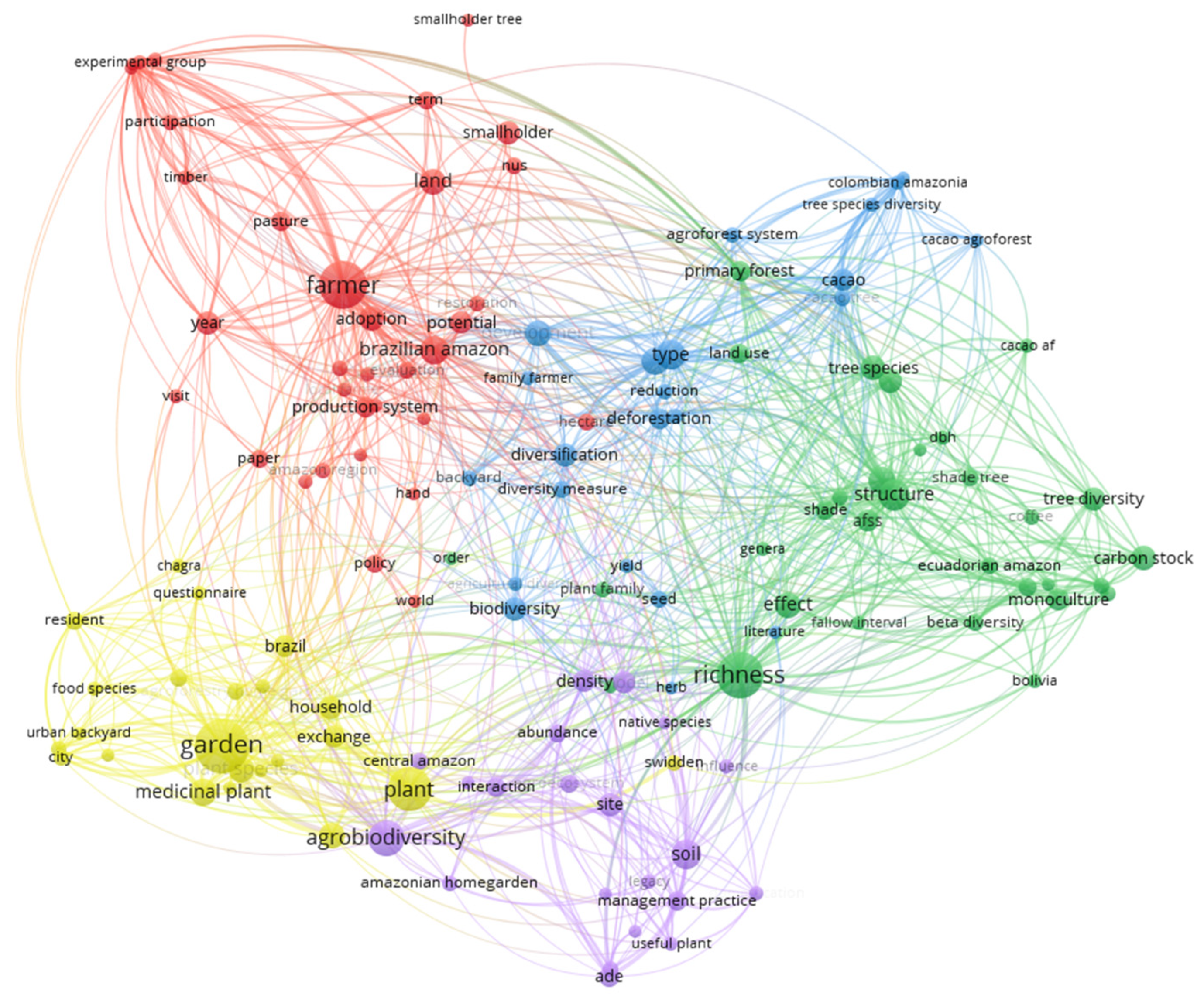

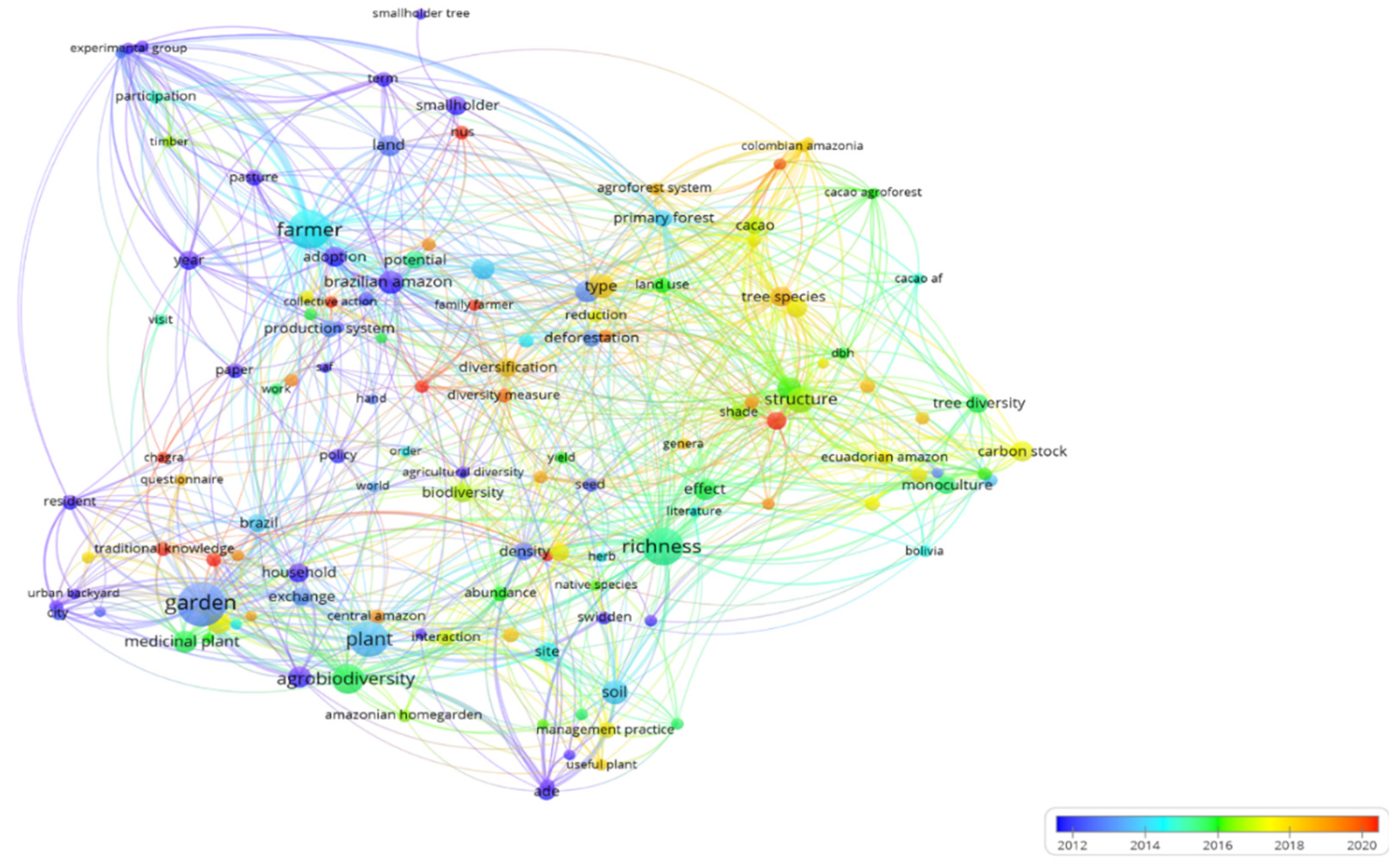

The distribution of terms in the articles’ co-occurrence network is illustrated in a cartographic map (

Figure 4), depicting the interrelation between words, indicated by circles, and lines indicating the frequency with which two terms appear together in the articles. The search identified a total of 2.452 words and 132 expressions of high importance in the 66 selected articles.

This selection identified five

clusters (groups of different colors), formed by the terms with the highest frequency (

Figure 4). The prominent terms were:

farmer,

Brazilian Amazon, and

production (red cluster);

crop,

type,

development, and

cocoa (blue cluster);

structure,

richness, and

tree species (green cluster);

agrodiversity, diversity, and

soil (purple cluster); and

plant,

garden, and

medicinal plant (yellow cluster).

The red cluster contained the highest number of terms (34 items), indicating research focused on socioeconomic aspects of the Brazilian Amazon, specifically on production and management, with emphasis on land use dynamics and the agricultural practices of smallholders. This group shows a strong association between

farmer and

experimental group, as indicated by the large thickness of the line connecting them. Examples of articles included in this cluster are a study evaluating the trend of polyculture crops with perennial plants in the Amazon [

22]; a study evaluating diversity measures in different types of soil cover, including AFS [

24]; and a study identifying factors related to access to financing, management, education, and decision-making in the adoption of commercial AFS by smallholder farmers in the state of Pará [

25].

The blue cluster contained the second-highest number of terms (31 items), which included

agroforest system,

cacao and

tree species, indicating a focus on technical approaches to AFS that incorporate cacao crops, primarily because it also included the terms

shade,

structure, and

effect. Examples of articles in this cluster are two studies from Brazil [

26,

27]: one on shade tree composition in cacao AFS, and the other on effects of household asset endowments on agricultural diversity in small-scale farms; and a study conducted in Peru [

28] investigating the arboreal composition, diversity, and structure in cacao agroforests.

The green cluster contained 23 terms representing central topics related to richness and structure, indicating that the studies are broadly connected to several topics, including homegardens, soils, and agrobiodiversity. This group highlights research on cacao crops related to shade trees, structure, and carbon stocks. Examples of articles in this cluster are a study on the effect of vegetation richness and structure on carbon storage in AFS in the Bolivian Amazon [

29], and a study on the effect of arboreal coverage on cacao yield in Ecuador [

30].

The yellow cluster contained 23 items indicating a concentration of research on HAF, primarily focused on urban evaluations. However, like the purple cluster, it also presented a strong connection with agrobiodiversity and medicinal plants. This group highlights a study on plant diversity in fields and homegardens in Peru, which demonstrated that the distance from urban centers is not linked to species richness in homegardens [

31]; a study on agrobiodiversity and medicinal plants in urban HAF in Mato Grosso [

32]; and a study in the state of Acre, Brazil [

33], which demonstrated the relationship between social factors and the richness of medicinal species in urban HAF.

This yellow cluster also included a study conducted in the Amazon estuary (state of Amapá), which indicated an increase in agrobiodiversity in HAF, with predominance of fruit trees and medicinal species [

34]. It also included a study evaluating plant management and selection in homegardens and swiddens in Bolivia [

35] that found that the managed trees tend to be more appreciated as sources of food and materials. In addition, the term

food species appeared in only one article, which reported a survey of plant food species grown in HAF in urban areas in the state of Acre [

36].

The term

chagra is also present in the yellow cluster, highlighting a study that addressed the knowledge, perception, and commerce in an indigenous community in Colombia [

37], and a study that compared plant diversity used between

chagras and homegardens in Peru [

38]. Other authors use this term, described as

crakra, in studies in Ecuador [

30,

39,

40].

The purple cluster contained the lowest number of terms (21), indicating research centered on agrobiodiversity. The terms

garden,

exchange, and

ADE (referring to

Amazon dark earths) indicated the prominence of studies on the diversity of cultivated plants, including medicinal plants, and management in HAF, as well as research focused on

Amazon dark earths, also known as Terra Preta or Indian black earth. Several studies demonstrate the function of these lands (fertile anthropogenic soils) in the conservation of native and exotic agrobiodiversity, and how their characteristics influence the structure, diversity, and composition in homegardens in the Amazon biome, along the Madeira and Urubu Rivers, in the state of Amazonas, Brazil [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

The purple cluster also contained the terms

site,

interaction,

management practice, and

soil, indicating specific studies on the influence of locations on agrobiodiversity, as well as management practices and plant use, reflecting the human dimension of environments. This cluster includes studies among the most cited, including those of Oliver T. Coomes on agrobiodiversity in household garden [

14,

15,

20], and a study highlighting the high diversity in homegardens with minimal focus on the market [

46].

The distribution of terms and the thickness of the lines that connect them (

Figure 4) indicated trends and research gaps. Fine lines represented a less frequent or weaker correlation between concepts in the articles. For example, the connection between

adoption and

establishment, which was distant and connected by a fine line, indicates an area within the AFS topic that requires further investigation. Similarly,

management practice is not connected with

adoption or

establishment, suggesting areas that could be better addressed, as management practices influence adoption and are linked to the labor of family farmers, who predominantly adopt AFS. Therefore, an article highlights the recognition of local agroforestry practices and the understanding of the changes in farmers’ subsistence means that the adoption of AFS can demand [

47]. Studies addressing these links are lacking, representing an important gap in the evaluation of AFS implementation.

The term

diversification was connected to

biodiversity,

deforestation,

restoration,

model, and

native species (

Figure 4). However, studies addressing the diversification of different AFS and its impact on production were limited. In addition, studies on the effect of increasing plant species or abundance of individuals on the management, labor activities, and farmers’ perception of these changes are scarce. The main objectives of studies discussing the production aspects of AFS were cacao yield, decreases in production costs, shading and coffee production, promotion of non-wood products, and logistics for marketing AFS products [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

Based on the results and gaps identified in published articles, approaches to fruit and food production in AFS can be recommended as potential subjects for new research, as two related terms were identified:

food species and

useful plant, which are not connected (

Figure 4). In general, studies addressing plant use and composition show results of surveys on HAF [

36,

45,

46,

53,

54].

Similarly, terms such as

seed,

development,

production system, and

diversification showed no co-occurrence with terms related to food production in AFS, highlighting an information gap that can be explored in new research. For example, studies conducted in Tomé-Açu, Pará, Brazil, featuring the terms

development and

co-production in their title primarily focus on integrating collective knowledge and strategies for disseminating and consolidating the Tomé-Açu Agroforestry System (SAFTA) [

55,

56]. Moreover, investigations correlating AFS development with food production diversification could aid in the evaluation of successful experiments in AFS.

The terms from

Figure 4 were distributed by year of publication (

Figure 5). Terms more recently used (2019 to 2020) formed the red and orange clusters, including

tree species diversity,

type,

family farmer,

restoration,

underutilized tree species,

traditional knowledge,

chagra,

diversity measure,

biodiversity conservation,

fallow interval, and

collective action, and synonym for AFS or HAF, such as

backyard. The recent use of these terms reflects the growing inclusion of small-scale research, indicating an increasing trend of studies in this scope.

The central words from 2017 to 2018 were

structure,

richness, and

cacao. This period highlights the concentration of studies on cacao, carbon, and biodiversity, focusing on practices of smallholder farmers, primarily in Colombia and Ecuador. Examples of articles from this period include a study evaluating a cacao AFS with innovative approaches, estimating canopy shading and understory light availability [

57], and a study on rural homegardens in the Eastern Amazon [

58], which demonstrated that the farmers’ origin influenced the diversity of plant species.

Older terms (2012 to 2015) were primarily distributed into two clusters, including

garden,

Brazilian Amazon,

plant and

farmer, household,

village,

adoption,

pasture,

year,

secondary forest succession,

density,

development,

swidden,

production system,

site, and

resident. These clusters concentrated terms related to AFS, production analysis, and experiments. Examples of articles from this period include two studies conducted in the Tapajós River region [

59,

60], focusing on the use of AFS as an economic alternative to cut-and-burn practices in small-scale agriculture, and the ethnobotanical use and knowledge of forest plant diversity in various vegetation areas, including HAF.

Other studies from this period include a report on the useful flora of modern HAF, which is partially a legacy of pre-Columbian occupations in the Central Amazon [

44], and a study on improved fallow in Peru, that described how farmers manage areas and trees as a soil management strategy [

61]. In addition, studies evaluated the adoption of AFS in Rondônia and the Rondônia Agroforestry Pilot Project, which found a trend of farmers maintaining agroforestry plots to allow secondary forest succession [

62,

63].

Studies published in 2016 primarily focused on diversity, richness, agrobiodiversity, abundance, and land use. Several terms related to cacao crops are appeared in the studies from this year, including

cacao agroforest,

cacao AF,

cacao,

cocoa,

cacao tree,

shade, and

tree diversity. Examples of articles from this year include studies on cacao AFS [

64], evaluating its potential to generate environmental benefits, and a study addressing the effects of shade tree diversity on seed production and the incidence of pathogens in cacao crops [

49].

Four articles with older studies (1996 to 1999) relevant to the research scope were identified [

16,

17,

22,

65]. These studies exhibited certain peculiarities not observed in subsequent research. For example, a study evaluating AFS in Peru [

65] did not use the term

chagra (

chakra or chacra) with the same emphasis found in more current studies, despite being conducted in an environment with fallow management characteristics typical of this type of system. This article refers to polyculture areas such as

forest gardens or

agroforestry fields, terms that were also not identified in the other selected articles.

A pioneering study [

16] focused on understanding agroforestry fallow cycles, emphasizing the dimension of the available area and its effect on diversity and marketing. In addition, a survey conducted across several states of the Brazilian Amazon [

22] focused on understanding crop patterns, agroforestry dynamics, and developmental constraints in polyculture fields. Moreover, the oldest published article on the HAF topic evaluated plants in the Peruvian Amazon focusing on the influence of tourism and the distance from urban markets [

17].

3.3. Main Authors and Studies

in terms of accumulated production, the scientific journal Agroforestry Systems had the highest number of published articles (17), and demonstrated consistent growth over the analyzed period, indicating a specialization in this research area. The journal Economic Botany published a total of five articles, though no new studies related to the scope have been published after 2011. The journals Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, Science Forest, Development and Environment, and Plos One published three articles each; however, but their publication frequency varied starting from 2013 onwards. The journals Sustainability, Acta Amazon, Acta Botanica Brasilica, and Agricultural Economics published one or two studies connected to the research scope.

The authors with the highest number of published articles included Charles R. Clement, with six articles, followed by Oliver T. Coomes and André B. Junqueira, each with four articles. Jorge H. Cota-Sánchez, Izildinha S. Miranda, and Thiago A. Vieira each published three articles, and Javier Amigo, Natalie C. Ban, John O. Browder, and Verônica Caballero-Serrano each published two. These results indicate that Charles R. Clement is a central figure in this field, while authors with fewer published studies may be emerging or less active in the AFS field.

The 15 articles with the highest number of citations were published by various journals, except four articles, which appeared in

Economic Botany and

Agroforestry Systems. The citation analysis identified the three most cited articles [

13,

14,

15], which contributed to the understanding of species domestication dynamics and agrobiodiversity in household gardens or HAF. Moreover, most studies (nine) were conducted between 1996 and 2009, while only six were published more recent (2014 to 2019). This suggest that the theoretical and methodological foundations established in these studies remain relevant to current research and continue being cited.

The interdisciplinary spectrum demonstrated by several journals through the most cited articles highlights the multifaceted nature of AFS, where dialogues between diverse knowledge areas is essential for advancing research. These studies include research on household gardens or HAF that encompassing agrobiodiversity, floristic diversity, composition, and ecosystem services [

14,

15,

17,

20,

66]; traditional knowledge and its influence on the diversity of medicinal plants in household gardens [

19,

67], characteristics and dynamics of domestication of species [

13], agroforestry adoption and practices [

16], and diversity of plants grown in fields and homegardens and its relation with geographical isolation [

31].

Studies focused on evaluating AFS of small-scale farms included an assessment of crop patterns and agroforestry dynamics in Brazil [

22], and an analysis of production efficiency and marketing [

51], primarily of forest products, in four countries in the Amazon biome (Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador). Studies emphasizing market aspects included a investigation of product destinations and the diversity of homegardens in the Amazonas [

46], and an analysis of the AFS of Tomé-Açu (Pará) to demonstrate the actions required for AFS to serve as an economic alternative to livestock [

68].

This list of articles also include studies addressing species diversity and carbon stocks [

18], as well as factors affecting the adoption of cacao AFS as a strategy for reforesting [

64]. The theme with higher visibility, based on the number of citations, is HAF or household garden.

3.6. Area Size, Methodology, and Sample Effort

Only 28 articles (42.4%) out of the 66 selected provided information on the size of the area (rural property or AFS area). Only one of the 11 articles focused on HAF research provided information on the total mean size of the property [

32], whereas the others reported the area occupied by homegardens, which ranged from 0.023 to 1.2 hectares (ha). One exception was identified, where homegardens occupied 2 ha, as the study considered the agroforestry surrounding the houses as an extension of the homegarden, resulting in large dimensions [

45]. The areas of cacao AFS ranged from 1 to 4 ha in Peru, Brazil, and Colombia [

26,

49,

57]. The size of areas with crop-forest, crop-livestock, improved fallow, and

chagras AFS ranged from 0.25 to 20 ha, as reported in 14 articles. The sizes of properties with commercial AFS were described in seven articles (10.6%) and ranged from 1.5 to 100 ha.

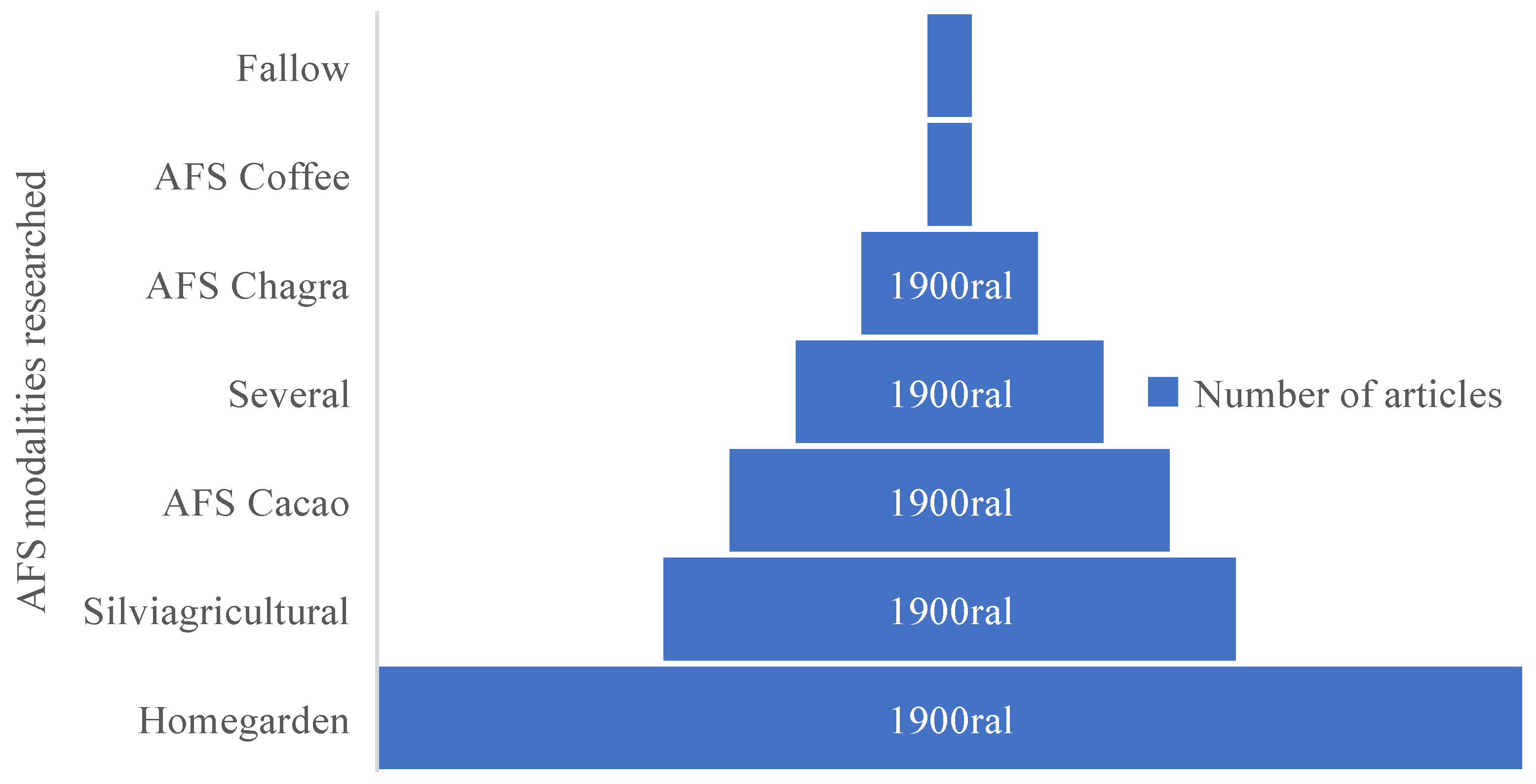

Regarding the methodologies employed in the selected articles, interviews were the predominant single tool for data collection in 34 articles (51.5%), inventory practices, involving the implementation of plots, were used in 17 articles (25.74%). Only two articles (3.0%) relied on secondary data, such as satellite images and production statistics. Additionally, combined approaches, such as interviews with questionnaires and inventory, were employed in nine articles (13.6%). The remaining four studies were conducted utilizing a combination of methods, including interviews, plot inventories, participant observations, soil sampling, and transect collection.

the collection effort showed no consistency in the sampled units, likely due to factors such as logistics, accessibility, size of areas, social characteristics, and nature of case studies in the published research. Sample sizes (plots, properties, or interviews) ranged from 10 to 50 for cacao and coffee AFS and from 12 to 70 for other crop-forest systems. HAF exhibited the most diverse sampling, with sample sizes ranging from six to 334 research units. Other studies examining various types of AFS within the same article utilized six to 181 collection points. One study on improved fallow utilized 32 interviews, while another on chagras AFS used six to 61 sampling units.

3.7. Choice of Species in AFS

The choice of species for cultivation or maintenance in AFS is influenced by numerous factors. Individual circumstances and personal preferences determine the crops to be grown and the effort they warrant [

65]. Available

labor was a significant factor in the adoption of AFS, since groups with mixed or non-logger systems have higher regular labor requirements [

63]. However, evidences suggest that crop intensification and a focus on a single plant species tend to homogenize floristic composition [

65]. Studies on cacao crops suggest that system composition is influenced by fallow intervals, as observed in Ecuador [

23], and by shade tree diversity and management strategies, as observed in Brazil [

26].

Crops guided by donors have predominantly involve the planting of seedlings from nurseries, whereas crops managed by smallholder farmers relay on transplanting seedlings and protecting specimens of natural regeneration [

51]. Additionally, farmers use ecological information to introduce a wide diversity of tree species [

61]. However, the inclusion of native fruit tree species with commercial potential in AFS is constrained by technical, social, environmental, and economic factors, particularly the lack of information and operational challenges related to harvest [

69].

In this context, a study conducted in São Félix do Xingu, Pará, Brazil, found that cacao crops are influenced by labor, market value, reforestation, and soil suitability, although not specifically during the AFS implantation stage [

64]. Furthermore, a study reported that the primarily potential products of shade trees for cacao crops are fruits, wood, charcoal, and medicinal products [

26]. In Peru, the maintenance of original tree vegetation that was practiced in the cacao AFS is strongly affected by its production value or service functions [

28], with preference for timber species or fruit trees to be grown with cacao [

70].

Plant species in HAF are selected for food security, household consumption, personal satisfaction, and well-being associated with shading, and minimally for product sales [

71] to complement family income. Plants cultivated in these environments have important food value, whereas spontaneously occurring plants are primarily valued for their medicinal properties [

35].

Regarding the number of plant species identified in the research, 44 articles (66.6%) provided quantitative data, often including the number of botanical families composing the studied production systems. Twenty-two of these articles were focused on HAF, 16 on other AFS, and three addressed two or more categories of production systems.

Information on the floristic composition of homegardens varied in the number of species and botanical families. However, some studies restricted the inventory scope based on the purpose of collections, such as medicinal, food, condiment, or specific plant groups. Similarly, not all studies reported the number of botanical families. The number of species in homegardens ranged from 41 to 484, with a mean of 147.2 ± 102.6 species. Homegardens with the highest species richness (more than 200 species) were found in three Brazilian states: Amazonas (ADE), Mato Grosso (urban areas), and Pará (urban and rural areas). The number of botanical families in homegardens was 28 to 97. The frequency distribution showed that most articles (59.1%) reported homegardens with 41 to 129 species, whereas 22.7% reported 130 to 218 species. Homegardens with more than 218 species were recorded in 18.1% of the articles (four studies).

Studies on commercial AFS (cacao, coffee, crop-forest, and

chagra) reported 16 to 127 plant species (mean 53.7 ± 31.9) and 12 to 40 botanical families, indicating lower species richness compared to HAF. However, some studies focused exclusively on specific plant groups, such as species planted for projects, arboreal and fruit tree species, or palms, wood trees, and banana trees [

28,

40,

52,

57].

Species richness in studies on commercial AFS varied widely, with 38.9% of articles reporting 16 to 38 species, 44.4% reporting 39 to 82 species, and 16.7% reporting more than 83 species. The highest species richness was recorded in studies on cacao AFS in Colombia and Bolivia [

18,

57], which reported 127 and 105 species, respectively.

3.8. Diversity and Richness in AFS

Studies on diversity and richness in

AFS within the Amazon biome primarily focused on comparing these systems with other environments, such as primary forest, secondary forest, and fallow areas. For example, one study evaluated arboreal species in cacao AFS, secondary forests, and primary forests [

28] and found that although

AFS cannot fully replicate the higher diversity indices of forests primary, they have crucial functions in conserving agricultural landscapes, where forests are intensely fragmented.

Diversity tends to increase linearly with the sizes of properties and AFS [

16,

38]. In agroforestry crops, few species show a high number of individuals [

26]; however, properties smaller than 10 ha exhibit greater diversification [

40]. The reviewed articles indicated that AFS integrated with natural regeneration can balance agricultural production with species richness and diversity [

72]. However, managing natural regeneration may be more effective for promoting species diversity than tree cropping [

51]. Historically, management practices have transformed the abundance of useful plant species and altered floristic composition [

13]. Additionally, agricultural diversity primarily reflects household asset endowments [

27].

In Peru, cacao AFS with mid-age crops (16-29 years) exhibited lower diversity compared to young AFS [

70]. However, species richness increased significantly as the crops aged [

49]. Moreover, the diversity across various soil cover types, including AFS, revealed limitations in measures used to differentiate soil cover types in all strata [

24].

HAF exhibit the highest plant diversity among the crop models of farmers [

14]. Despite extensive knowledge of useful forest species diversity, most plants utilized originate from modified areas such as homegardens, fallow lands, and secondary forests [

60]. Household garden maintainers diversify these spaces by cultivating crops previously grown in annual fields as a strategy to partially offset agrobiodiversity loss [

34].

HAF with greater plants diversity offer enhanced ecosystem services [

66], while plants species in gardens reflect traces of human history [

42]. This is evidenced by the high diversity of species found in homegardens established in TPA, highlighting the legacy of previous human occupations [

45]. The successive occupation by different cultural groups over of time may have contributed to the higher diversity of useful species observed today [

44].

The studies indicated that HAF structure, diversity, and agricultural species richness are influenced by several factors, including the origin of farmers and the management of these environments [

58]; soil fertility, natural and anthropogenic variations in soil properties, and homegarden size [

41,

43]; family income, homegarden size, and topography [

36,

73]; farmers’ centrality within exchange networks and proximity to their residence [

67]; distance from urban centers, level of external information exchange, and household garden size [

20,

31]; and the propensity to interact and receive plant donations [

15].

3.9. Functions of Agroforestry Systems

The

AFS identified in this review highlight HAF as a multifunctional central system with a wide range of species, serving as areas for testing and conserving plant specimens. However, few studies have addressed the age of homegardens, one study in Peru and one in Ecuador, which reported means of 7.6 and 13 years, respectively [

14,

15,

19].

These environments are recognized as centers for cultivating useful plants, points for the flow of materials for subsequent crops, and areas for experimenting with new species [

14,

34,

41]. They also serve as sites for establishing seedling nurseries [

61], receiving plants grown in fields [

20], and functioning as open laboratories for plant selection [

42]. These locations acquire new uses through continuous experimentation, facilitated by increased contact [

35]. In commercial AFS, farmers also foster continuous experimentation, creating dynamic systems [

16,

22], with management practices that alter the forest composition [

13].

The exchanges of plant species in HAF reveals a social network strengthened by the sharing of traditional knowledge [

33], making HAF to be considered the most dynamic of all ecosystems [

44]. Families with higher diversity in their household garden tend to exchange more plant materials compared to those with limited diversity [

20]. More biodiverse systems enable farmers to participate in cycles of donation and expansion within social networks [

15], while kinship ties and gender influence the exchange patterns of medicinal plants [

67]. Following this implementation logic, some improved fallow areas near houses can become permanent household gardens over time, dominated by fruit trees [

61]. Homegardens in TPA have more fertile soils and are often used for exotic crop species, as farmers take advantage of this high fertility to grow nutrient-demanding species [

41,

43].

In the different

AFS, fruit tree species are emphasized as central due to their frequency and abundance [

14,

17,

34,

40,

53,

58,

59,

67]. Beyond the cultivation and maintenance of fruit trees, studies report at least one additional category of use, including vegetables, medicinal plants, or non-fruit food plants [

15,

31,

36]. Several studies also discuss the destination of food plants in AFS without specifying distinct plant groups [

33,

37,

54,

66].

HAF is reported to predominantly contain arboreal individuals that are food plants and herbaceous plants with therapeutic value [

35,

43]. Other AFS are characterized by the predominance of native trees that produce forest products other than logs [

51]. Several studies on HAF report dominance of exotic crop species [

22,

36,

46,

58], whereas research on the Madeira River identified a predominance of native species [

41].

The cultivation of medicinal plants in HAF not only reinforces their therapeutic purposes, but also reflects their cultural heritage [

74]. These locations are identified as sources of food, essential for the subsistence in rural zones, whereas in urban areas, they are primarily valued for ornamental and shading purposes [

66]. In general, the functional convergence of HAF is emphasized, as despite differences in number of species, the relative number per category of use is comparable [

15].

3.11. Motivation and Adoption of Agroforestry Systems

The adoption of AFS is associated with various reasons and motivations, primarily related potential capital accumulation, with the land ownership being a crucial factor for the implementation of perennial agricultural systems [

59]. In addition, the recognition of agroforestry practices [

47] and the widespread use of traditional knowledge [

60] are crucial to this process. Owners of large landholdings, with a higher number of farm residents, demonstrated a greater propensity to adopt innovative agroforestry systems [

63].

Agricultural diversity reflects the allocation and distribution of resources and family assets, which is a key element for conservation production but can also be a limitation for the adoption of AFS [

27]. The limitations of rural extension services and the use of information on AFS are also identified as obstacles to adoption [

62]. A study conducted in Bragança, Pará, Brazil, identified access to financing, AFS management (including objectives, cultural practices, and land preparation), education level, and decision-making (influenced by farmers’ gender), are the main determinants for adopting this production system [

25].

The agroforestry status was shown to be dynamic in the evaluated articles concerning the adoption of intercropping systems. The articles indicated that AFS implementations are not expanding in Bolivia [

18], and wood plantations have been less successful in various countries within the Amazon biome [

51]. However, farmers in Rondônia and Pará expressed the intention to expand the size of agroforestry sites [

52,

75]. The adoption of an innovative model of agricultural systems by farmers in Tomé-Açu created new opportunities, resulting in greater flexibility in the choice of their arrangements, the development of new techniques, and expanded marketing options, which inspired local smallholder farmers to adopt AFS [

55,

56].

These motivations and opportunities for adopting agroforestry also include the environmental and ecosystem services provided by arboreous environments, which is connected to water quality and food security [

30,

72,

75]; consumption of fruits, medicinal resources, improvements in other crops, and product sales [

69]; higher satisfaction related to itinerant pasture and agriculture [

50]; shade for perennial crops, better working conditions, soil protection and improvement [

51]; shade and thermal comfort [

63,

76]; and production diversification [

18].

A study on farmers under the Program for Socio-Environmental Development of Rural Family Production (Proambiente) also confirmed that AFS production resulted in higher food availability, increased acquisition of goods, promotion of environmental services, and the inclusion of farmers in the consumer market due to the diversity of products in agroforestry arrangements [

76]. Thus, a trend of spontaneous diffusion of agroforestry is expected in areas with demonstration plots of agroforestry practices [

52].

Studies on environmental aspects of AFS reported that including wood production was a catalyzer for forest restoration [

52]. These systems enable the conservation and rehabilitation of land use in areas where tropical forests have been degraded and fragmented [

28,

63]. In addition, their potential for biodiversity conservation in agroforest programs is significant [

35], and this conservation, enabled by the shade of trees, may be a target of policies encouraging their maintenance [

26]. AFS can enrich the soil, improving its fertility by reproducing mechanisms of forest conservation [

13], and can be used to restore protected reserves and mitigating environmental liabilities [

64]. Studies also reported that increases in AFS areas are an attempt to restore the functions and benefits lost to environmental degradation [

75].

An analysis of the potential of AFS in Tomé-Açu indicated that they represent a complex social-technological system encompassing a distinct philosophy of Amazonian land use and agriculture, as well as innovative agricultural techniques, processing, and value-added chains, pointing towards a path for a sustainable rural development in the Amazon [

56]. Thus, public financing could be justified by numerous positive externalities of AFS for families and communities [

59], or incentivized through remuneration for avoided deforestation [

30]. Future efforts for food security and poverty reduction need to focus more on species-rich AFS [

50].

3.12. Incentives and Promotion of Agroforestry Systems

Studies addressing the impact of financing or other incentives on the implementation and development of AFS in the Amazon were scarce among the articles selected for this review. The financing source showed a strong correlation with the AFS composition in Bragança, Pará, where the selected species were adopted by farmers due to interest in the crop, despite delays in delivery and development of the project [

25]. The recommendation is that financing projects should complement those focused on the use of products from fallow areas, open fields, and household gardens [

60] to avoid overloading the people involved and altering the main production mode.

Research conducted by the Agroforestry Tree Domestication Program, after 20 years of implementation, indicated that the objectives were not achieved and, according to farmers, the program was financially unviable [

77]. Another evaluation emphasized that: a) there was no difference between the sizes of plantations guided by donors and those implemented by farmers; b) donors promote tree plantations with limited success, neglecting management limitations and underestimating the potential of local independent tree plantations and; c) smallholder farmers seldom continued the regular maintenance of plantations guided by donors after the project ended [

51]. In this context, in a study in Peru on agroforestry use grants, where farmers maintain forest remnants and establish or maintain AFS, found that most farmers indicated a need for economic incentives, particularly for tree plantations [

47].

A study showed that the official technical assistance agency was active only during the initial years of establishment of AFS, leading to implementation failure [

25]. In addition, most agroforestry arrangements were established based on farmers’ initiatives rather than external agents [

22]. A study conducted in Rondônia showed that the average area allocated to AFS decreased after the agency leading the project closed [

62]. This project, conducted by an association financed by an international organization from 1996 to 2009, successfully promoted the adoption of AFS while the organization was active, although it did not result in significant improvements in the farmers’ financial yield.

Several studies addressed weakness or threats to adoption and continuity of AFS [

18,

22,

38,

51,

57,

59,

69], identifying limitations such as: a) insufficient agro-industries ; b) limited access to quality seeds and seedlings; c) operational challenges in harvesting wood within intercropping systems; d) lack of information on specific agricultural practices; e) insufficient labor and equipment for pruning; f) high initial implementation costs; g) unfamiliarity with the cultivation of certain species; h) difficulties in maintaining diversity and conservation; and i) challenges in integrating with market and influencing biocultural relations that sustain in situ conservation.

However, some promising results were reported, including a study in Rondônia, which found that most farmers retained at least one or more wood-producing species in their agroforestry plots after 10 years [

52]. Additionally, most farmers expressed interested in expanding planted areas with valuable timber species or enrich fallow areas [

47]. The prominent function of farmers in Tomé-Açu led to the adoption of AFS by petrol companies, which initially did not consider the group for financing

Elaeis guineensis Jacq. crops [

55,

56].

Therefore, despite scientific advances, the expansion of AFS faces challenges related to technical knowledge, financial incentives, and the need for programs involving education, research, and rural extension institutions to enhance understanding and promote adoption of these systems. In addition, information gaps limiting the expansion of AFS extend beyond the diversity of available perennial species to include issues related to management and lack of economic data, such as production costs and profitability, which could assist in shifting the paradigm of traditional monoculture.