1. Introduction

Background

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterised by a wide variety in both clinical and immunological manifestations.[

1]

Compared to the general population, patients with SLE are more likely to develop infectious events[

2]. In fact, at least 50% of individuals encounter a serious infection, as they account for 11-23% of hospitalisations. To date, bacterial infections are the predominant causative factor in SLE patients (51.9%), with viruses accounting for 11.9% and lastly fungi for 2.3%[

3].

SLE predominantly affects women, particularly during their reproductive years, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 9:1 [

4]. However, notable differences exist between male and female SLE patients. Males tend to present with more severe forms of the disease and are generally diagnosed at an older age, often up to six years later than females[

5]. Clinically, male patients are more prone to severe manifestations, including significant skin lesions, serositis, thrombotic events, and neurological complications. Renal involvement is more common in males, with an increased susceptibility to lupus nephritis, frequently progressing to end-stage renal disease [

6,

7]

Sex Hormone-Induced Variations in Immune Response

Differences in SLE across sexes are influenced by genetic, hormonal, and immune response variations. The function of oestrogen and its receptors in the pathogenesis is substantial, since they enhance immunological responses that worsen the disease, whereas androgens tend to improve it.[

6]

Sex-specific differences in Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression and TLR-driven interferon-alpha (IFN-α) production have been identified in the sexes. TLRs, which are pattern-recognition receptors essential for innate immunity, can contribute to autoimmune diseases when their responses are dysregulated. In SLE, intracellular TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 in plasmacytoid dendritic cells recognize nucleic acids, triggering type I interferon production, a key mediator in SLE pathogenesis characterized by elevated IFN-α levels and increased expression of interferon-inducible genes.

TLR7 and TLR8, encoded by adjacent genes on the X chromosome, can escape X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) in women, leading to increased TLR expression and enhanced IFN-α production by B cells in response to stimulation. This sex-specific IFN-α production pathway appears independent of estrogen signaling for TLR7, although TLR8 expression requires estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) binding to an estrogen-responsive element near the TLR8 gene locus. Estradiol-bound ERα may further enhance TLR8 expression by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1). Additionally, TLR4-mediated cytokine responses, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, fluctuate with the menstrual cycle, suggesting sex hormone influence, although the exact mechanisms remain unclear.[

8,

9,

10]

Other factors concur to the sex-based differences observed in SLE patients.

The molecular mechanisms of miRNA expression exhibit notable differences between males and females, particularly influencing autoimmune conditions like SLE. miRNAs, small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally, show sex-specific expression patterns in various tissues, including the brain, immune cells, and gonads. These differences are partly due to the genetic contribution of X-linked miRNAs, with about 113 miRNAs located on the X chromosome, compared to only two on the Y chromosome. Such genetic disparity contributes to sex differences in immune function and susceptibility to autoimmune diseases.[

6,

11]

Oestrogen plays a significant role in modulating miRNA expression, influencing immune responses differently in males and females. In females, oestrogen affects miRNA biogenesis and function through oestrogen receptors, altering the expression of miRNAs involved in immune regulation. For instance, oestrogen upregulates miR-223 and miR-18a while downregulating miR-146a in splenocytes, which modulates inflammatory responses and type I interferon signalling pathways that are crucial in SLE. These oestrogen-mediated changes in miRNA expression contribute to the heightened immune reactivity observed in females, enhancing susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. Additionally, oestrogen can directly interact with miRNA biogenesis machinery, altering the processing of pri-miRNAs and impacting their maturation into functional miRNAs.[

8]

Sexual dimorphism in miRNA expression is also linked to the differential regulation of immune genes, where miRNAs such as miR-182, miR-31, and miR-155 show distinct expression patterns in female lupus-prone mice compared to males. These miRNAs contribute to the dysregulation of T and B cells, enhancing the autoimmune response in females. [

12,

13]

Together, these molecular mechanisms highlight the intricate interplay between sex hormones, genetic factors, and miRNA regulation in shaping the sex-specific immune responses observed in SLE and other autoimmune conditions.

What this Work Adds

This study used real-life data to explore the sex differences in infection risk among SLE patients, distinguishing itself by using a comprehensive approach that accounts for confounding factors like disease duration and treatment. Unlike previous studies that merely focused on disease severity and activity, our research specifically highlights the distinct infection risk profile in males, offering a nuanced understanding of how sex influences infection susceptibility in SLE beyond the established clinical manifestations.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

Outpatients with a verified diagnosis of SLE according to the 2019

American College of Rheumatology/ European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria [

13] were included in this retrospective monocentric study.

Infectious episodes were identified from medical records between 2017 and 2023 and categorized by severity.

Exclusion of patients with insufficient or partial medical documentation was implemented to guarantee the integrity of the data. Furthermore, we implemented other exclusion criteria, such as current neoplasia, diagnosis of primary or secondary immunodeficiency, and substance addiction.

Records of current and previous therapies, comorbidities and immunosuppressants were also gathered to determine.

Objectives

The primary aim is to assess the role of sex in the risk of infection in patients affected by Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and to assess for possible patterns or correlations between clinical factors.

Data Collection

Sex, age, age at diagnosis, smoking habits, ongoing and previous treatments, infectious events were collected from medical records. Moreover, data on their serological profiles were also verified as to determine possible correlations (anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies - anti-dsDNA, evaluated on fluorescent enzyme immunoassays - FEIAs - by ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA and IFA on Crithidia luciliae -Euroimmun S.r.L. for positive findings in order to confirm the result), anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies (divided, where available, into 52 kDa and 60 kDa, evaluated on fluorescent enzyme immunoassays - FEIAs by ThermoFisher), anti-La/SS-B and anti-Smith (anti- Sm, FEIAs byThermoFisher) antibodies.

Lastly, complement levels, namely C3 and C4, were recorded throughout the medical records.

Statistical Analysis

An analysis of the collected data was conducted using STATA SE 18.0 (1985-2023 StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, United States of America).

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data distribution to ensure appropriate model assumptions. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the assessment of risk factors. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to adjust for potential confounders. Model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and interactions between variables were tested. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the findings.

Ethical Approval

After receiving comprehensive information, all of the participants provided their consent. All the procedures were conducted in compliance with the relevant regulations, in line with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and in compliance with the limitations established by the legislative body. The local Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico Territoriale interaziendale AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, study #0116953) granted formal approval for this research.

3. Results

A total of 119 patients were included in the analysis (107 F, 12 M, F:M 8.92:1); demographics are shown in

Table 1.

Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in age between sexes (t = -0.715, p = 0.487), whereas disease duration was significantly shorter in males compared to females (t = 3.35, p = 0.003).

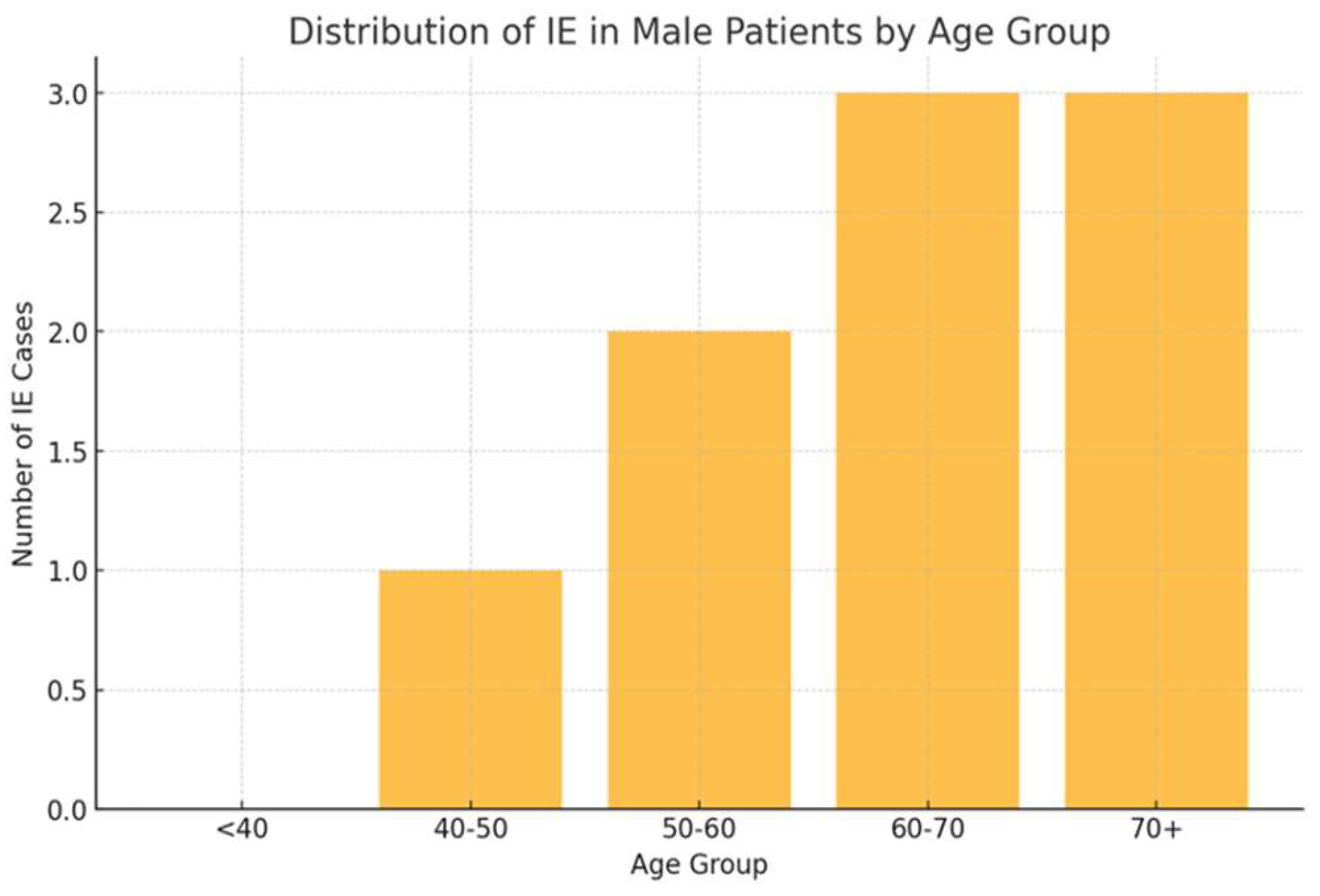

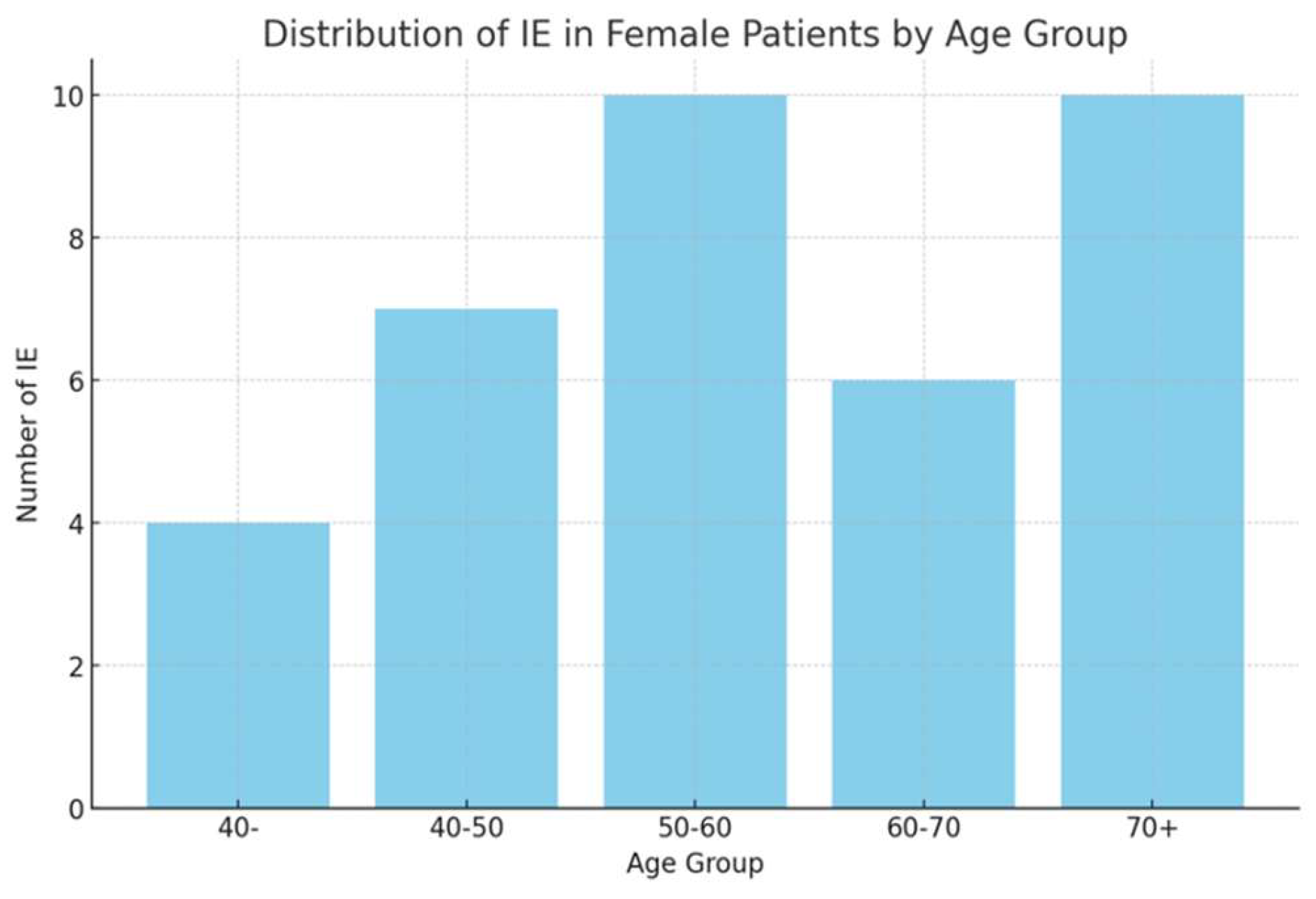

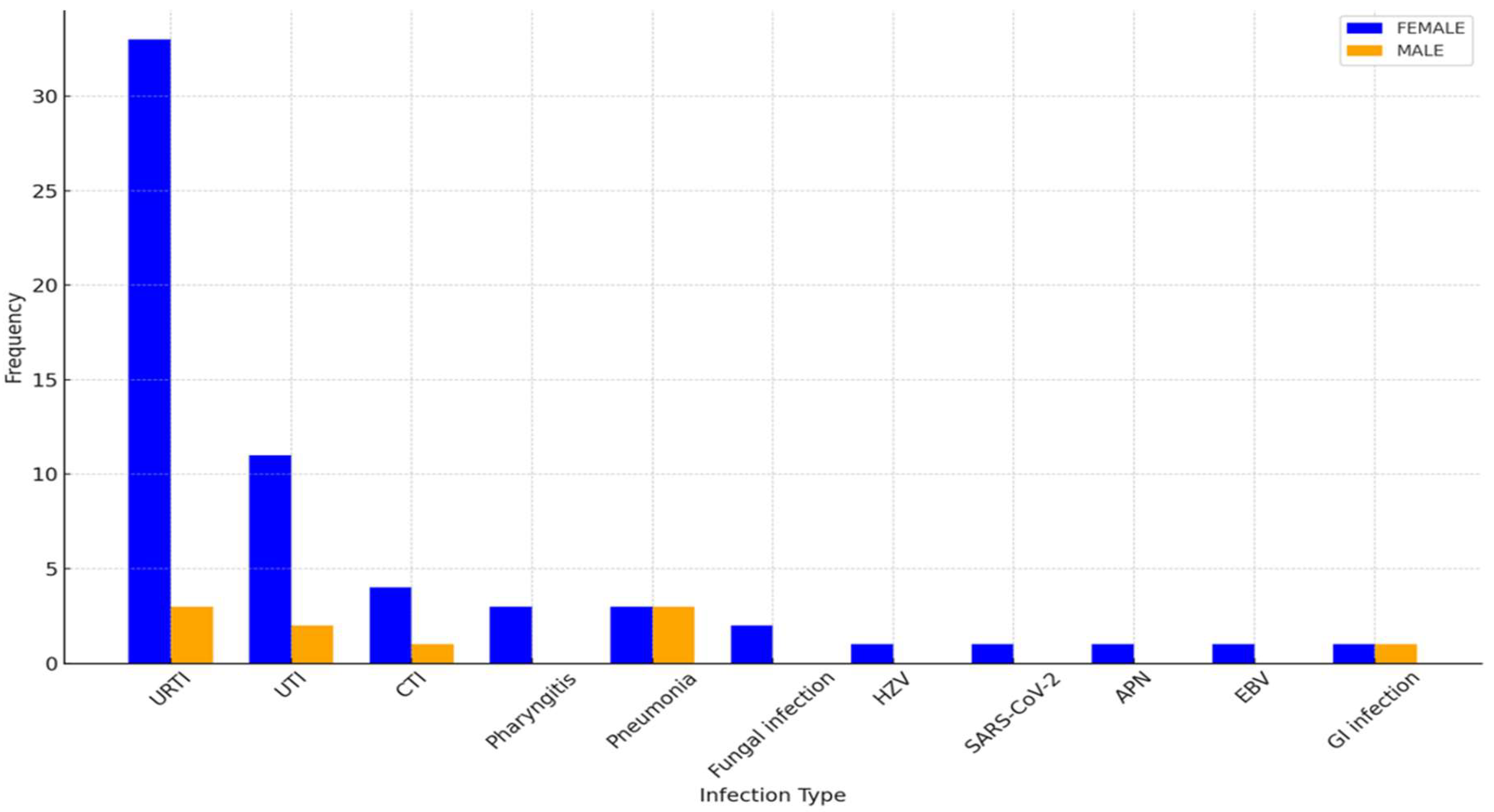

Infectious episodes were categorized based on type and severity, with URTIs being the most prevalent in both sexes. As shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, female patients exhibited higher incidences of URTIs (35.1%), followed by UTIs (21.6%), and lower respiratory tract infections (CTI) (10.8%). Among male patients, URTIs were also the most common (33.3%), followed by pneumonia (22.2%) and UTIs (22.2%).

4. Discussion

A logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between disease duration, sex, and smoking status with the risk of infections in patients with SLE.

Regarding sex, the logistic model indicated a statistically significant association between male sex and the risk of infections (β = 0.9426, Logit(p) = -0.6061 + 0.9426 × sex, p-value= 0.05).

A similar result was obtained via the odds ratio whilst comparing the infection risk between female and male patients, as it showed an almost sixfold probability in the latter (OR 5.675, 95% CI: 1.4479; 22.2477, p = 0.0127).

On the other hand, disease duration (dd) failed to be statistically significant (β = 0.0250, Logit(p) = -1.1319 + 0.0250 ×dd, p-value= 0.102).

Smoking status was also included in the regression model; its p-value for smoking was 0.078, suggesting a trend towards significance but not reaching statistical significance (β = 0.4529, Logit(p) = -0.8200 + 0.4529 × smoking).

The overall regression equation incorporating all variables is shown in

Table 2 (Logit(p) = -0.6563 + 0.0283 × dd + 0.9426 × sex + 0.4529 × smoking).

The logistic model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (stat = 0.1893, GdL = 5, p = 0.9992), confirming the model’s adequacy.

Moreover, a correlation analysis was performed to assess relationships between clinical and immunological markers with infection frequency. Notably, a statistically significant correlation was found between the presence of SS-A antibodies and infection rate (r = 0.291, p = 0.003), suggesting that specific immunological profiles may predispose patients to a higher risk of infection.

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the influence of sex on the risk of infections among patients with SLE. Our findings suggest that male patients are at a significantly higher risk of infections compared to females. This is particularly relevant considering that males, although fewer in number, often present with a more severe disease course; these data are in line with the observations made by the LUMINA (LUpus in MInorities, NAture versus nurture) [

14] study, a multiethnic U.S. registry including Hispanic, African American, and Caucasian patients. This study compared disease activity between males and females with SLE using specific measures of activity and accumulated damage to understand the impact of sex on the manifestations and outcomes of the disease.

Notably, the distribution of infections differed between the sexes: while upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) were the most common in both groups, males exhibited a higher prevalence of severe infections such as pneumonia, contrasting with females who more frequently experienced urinary tract infections (UTIs). These findings are consistent with the observations made by Schwartzman-Morris and Colleagues[

15], although their paper did not focus on the type and distribution of infections but rather on the clinical differences between sexes in lupus patients

Based on the data from this study, the roles of age, smoking, and disease duration in influencing infection risk in SLE patients appear nuanced and less straightforward. Unlike previous studies[

5], age did not significantly differ between male and female patients, suggesting that the increased infection risk in males cannot merely be attributed to age-related factors. This highlights that other sex-specific factors, such as immunological and hormonal differences, might play a more critical role in the matter.

Smoking, while showing a trend toward significance, was not statistically significant in this cohort. However, smoking is generally known to compromise immune function and may still act as a compounding risk factor, especially in the presence of other vulnerabilities seen in SLE. Its role should not be entirely dismissed, as it might contribute to a cumulative effect on infection susceptibility, as seen in other reports on SLE patients.

Disease duration was shorter in males compared to females, which indicates that the higher infection risk observed in males might not be due to longer exposure to the disease.

This finding might suggest an intrinsic vulnerability to infections among males, possibly linked to differences in immune response and specific immunological profiles, such as the presence of SS-A antibodies, which were associated with higher infection rates in our analysis.

However, unlike the LUMINA study, which identified ethnicity, lack of health insurance, and psychological factors as key contributors to disease activity, our focus was to explicitly address the impact of sex on infection risk, making our study a novel contribution to understanding how sex influences infection susceptibility in SLE.

Similarly, the work by Nusbaum et al.[

6]. highlighted that males with SLE often experience more severe disease manifestations, including renal involvement and cardiovascular complications, which can indirectly heighten infection risk. However, these studies did not delve into infection risk specifically, whereas our research provides direct evidence of a sex-based disparity in this domain.

Our findings suggest that clinical management of SLE should incorporate a more tailored approach, with heightened vigilance for infections in male patients. This could lead to better prevention strategies and therapeutic interventions specifically aimed at mitigating infection risks in this vulnerable subgroup. Further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms of these sex-based differences, particularly focusing on immune response variations and their clinical implications.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the study relies on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which may introduce information bias, particularly in documenting infectious events and their severity. The limited number of male patients, which reflects the epidemiology of the disease, may affect the generalizability of the findings and reduce the statistical power to detect more subtle associations between risk factors and infection rates.

Additionally, all patients included in this study were Caucasian, limiting the ability to generalize these findings to other ethnic groups, who may experience different infection risks due to genetic, socioeconomic, or environmental factors. While we adjusted for some potential confounders, such as disease duration and smoking status, other unmeasured variables, including medication adherence and socioeconomic factors, may have influenced the results. The study also did not evaluate the impact of hormonal differences or detailed immunological profiles, which could further elucidate the observed sex differences in infection risk.

Finally, the study’s focus on a single centre further restricts its external validity, as patient management and healthcare access can vary significantly across different settings. Prospective studies with larger, more ethnically diverse populations are needed to confirm these findings and explore the underlying mechanisms driving the observed sex-based disparities in infection risk among SLE patients.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

SLE (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus), OR (Odds Ratio), CI (Confidence Interval), SS-A (Anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies), TLR (Toll-like Receptor), IFN-α (Interferon-alpha), ERα (Estrogen Receptor Alpha), STAT1 (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1), XCI (X-chromosome inactivation), CTI (Connective Tissue Infection), HZV (Herpes Zoster Virus), SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2), APN (Acute Pyelonephritis), EBV (Epstein-Barr Virus), GI (Gastrointestinal), FEIA (Fluorescent Enzyme Immunoassays), IFA (Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay), ACR/EULAR (American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology), TNF-α (Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha), IL-1β (Interleukin-1 beta), IL-6 (Interleukin-6), IL-8 (Interleukin-8), miRNA (microRNA), anti-dsDNA (anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies), C3 and C4 (Complement 3 and Complement 4 proteins), URTI (Upper Respiratory Tract Infection), UTI (Urinary Tract Infection).

References

- Jha, S. B. et al. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Cardiovascular Disease. Cureus 14, e22027. [CrossRef]

- Pego-Reigosa, J. M. et al. The risk of infections in adult patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 60, 60–72 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rúa-Figueroa, I. et al. Bacteremia in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Patients from a Spanish Registry: Risk Factors, Clinical and Microbiological Characteristics, and Outcomes. J Rheumatol 47, 234–240 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Barber, M. R. W. et al. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol 17, 515–532 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Trentin, F. et al. Gender differences in SLE: report from a cohort of 417 Caucasian patients. Lupus Sci Med 10, e000880 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Nusbaum, J. S. et al. Sex Differences in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Epidemiology, Clinical Considerations, and Disease Pathogenesis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 95, 384–394 (2020).

- Ramírez Sepúlveda, J. I. et al. Sex differences in clinical presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Biol Sex Differ 10, 60 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Christou, E. A. A., Banos, A., Kosmara, D., Bertsias, G. & Boumpas, D. Sexual dimorphism in SLE: above and beyond sex hormones. Lupus 28, 3–10 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. TLR9 polymorphisms and systemic lupus erythematosus risk: an update meta-analysis study. Rheumatol Int (2016). [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, A. B. TLR7 Signaling in Lupus B Cells: New Insights into Synergizing Factors and Downstream Signals. Curr Rheumatol Rep (2021). [CrossRef]

- Khan, D., Dai, R. & Ansar Ahmed, S. Sex differences and estrogen regulation of miRNAs in lupus, a prototypical autoimmune disease. Cellular Immunology 294, 70–79 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Full article: Sexual dimorphism of miRNA expression: a new perspective in understanding the sex bias of autoimmune diseases. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/TCRM.S33517. [CrossRef]

- Aringer, M. et al. 2019 EULAR/ACR Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 71, 1400–1412 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic cohort (LUMINA): XXVIII. Factors predictive of thrombotic events | Rheumatology | Oxford Academic. https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/44/10/1303/1788385.

- Schwartzman-Morris, J. & Putterman, C. Gender Differences in the Pathogenesis and Outcome of Lupus and of Lupus Nephritis. Clin Dev Immunol 2012, 604892 (2012). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).