Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

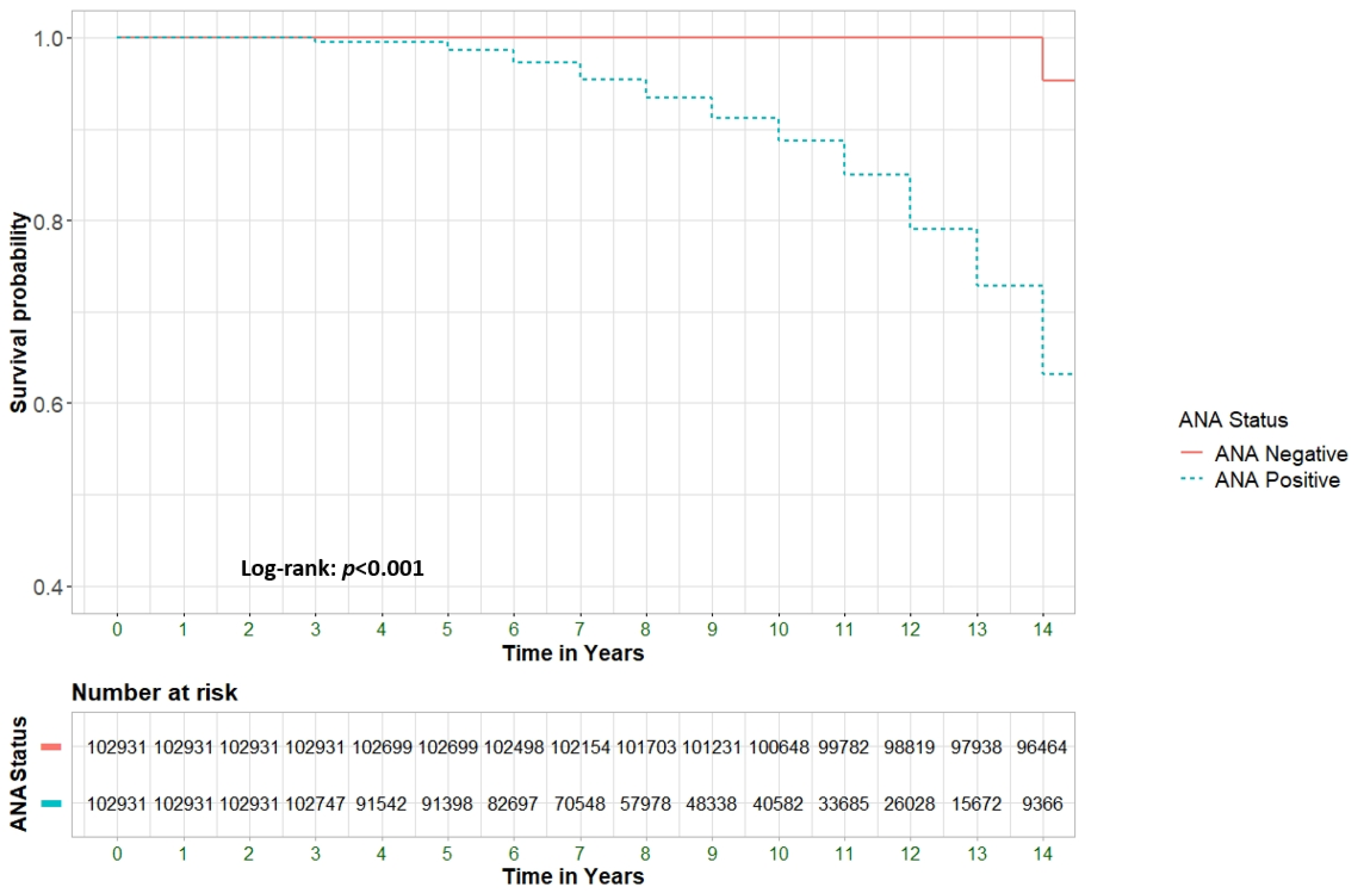

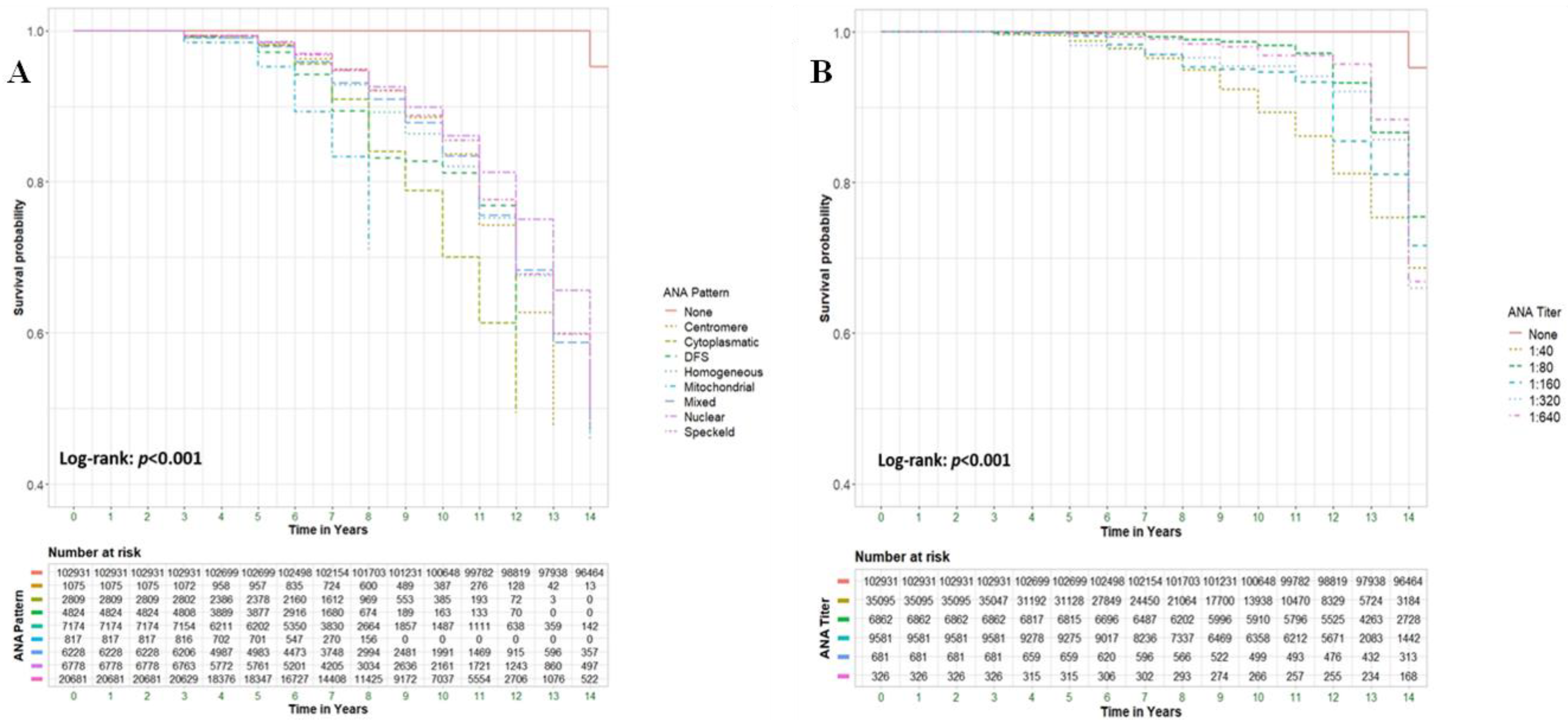

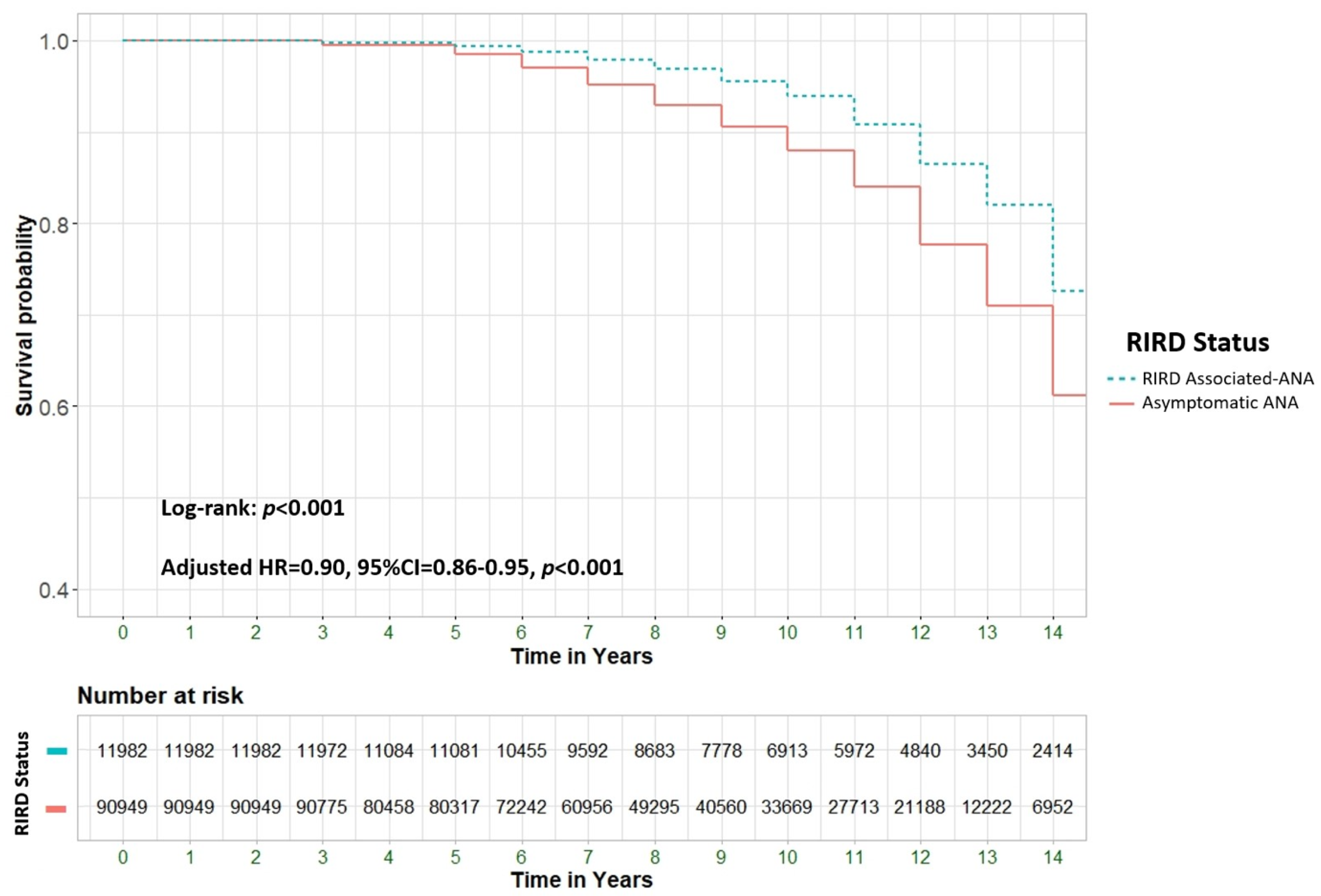

Background & Objectives: To explore the potential association between positive ANA serology and all-cause mortality in a large cohort of patients, including those with and without rheumatological conditions and other immune-related diseases. Material and Methods: A retrospective cohort study analyzed all-cause mortality among 205,862 patients from Clalit Health Services (CHS), Israel's largest health maintenance organization (HMO). We compared patients aged 18 and older with positive ANA serology (n=102,931) to an equal number of ANA-negative controls (n=102,931). Multivariable Cox regression models were used to assess hazard ratios (HR) for mortality, adjusting for demographic and clinical factors. Results: ANA positivity was strongly associated with increased mortality (adjusted HR [aHR] 4.62; 95% CI 4.5-4.7, p<0.001). Significant predictors of mortality included male gender (39.2% vs. 24.4%, p<0.001), older age at testing (72.4 ± 13.0 vs. 50.1 ± 17.3 years, p<0.001), and Jewish ethnicity (89.6% vs. 83.2%, p<0.001). Certain ANA patterns, such as mitochondrial and dense fine speckled (DFS), were highly predictive of mortality, with aHRs of 36.14 (95% CI 29.78-43.85) and 29.77 (95% CI 26.58-33.34), respectively. ANA-positive patients with comorbid rheumatological immune-related disorders (RIRDs) demonstrated a higher survival rate compared to those without such a condition (aHR 0.9, 95% CI 0.86–0.95, p < 0.001). This finding remained significant after adjusting for several parameters, including age. Conclusion: ANA positivity is associated with increased all-cause mortality, particularly in individuals without rheumatologic disorders, after adjusting for confounders such as age. This may indicate occult malignancies, cardiovascular pathology, or chronic inflammatory states, necessitating more vigilant surveillance.

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

Study Design and Population

Data Collection

Outcomes and Definitions

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Considerations

Results

Study Population

| Variable | All Patients(n=205,862) | ANA Positive(N=102,931) | ANA Negative(N=102,931) | P-value | |

| Patient Sex | Male | 54406(26.4) | 27203(26.4) | 27203(26.4) | 1.00 |

| Female | 151456(73.6) | 75728(73.6) | 75728(73.6) | ||

| Age at ANA test, years | 50.3±18.6 | 53.2±18.5 | 47.4±18.3 | <0.001 | |

| Ethnicity | Jewish | 176850(86.0) | 86448(84.1) | 90402(88.0) | <0.001 |

| Arab | 28701(14.0) | 16334(15.9) | 12367(12.0) | ||

| Smoking | 72363(35.2) | 36305(35.3) | 36058(35.0) | 0.254 | |

| Comorbidities | Diabetes Mellitus | 49689(24.1) | 24858(24.2) | 24831(24.1) | 0.889 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 121077(58.8) | 60028(58.3) | 61049(59.3) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 80934(39.3) | 41138(40.0) | 39796(38.7) | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | 66757(32.4) | 33540(32.6) | 33217(32.3) | 0.128 | |

| rheumatological immune-related disorders (RIRD) | Any | 16429(8.0) | 11982(11.6) | 4447(4.3) | <0.001 |

| SLE | 5063(2.5) | 4445(4.3) | 618(0.6) | <0.001 | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1888(0.9) | 839(0.4) | 1049(0.9) | <0.001 | |

| Systemic Sclerosis (diffused) | 1191(0.6) | 1113(1.1) | 78(0.1) | <0.001 | |

| Sjogren | 2500(1.2) | 2015(2.0) | 485(0.5) | <0.001 | |

| Myositis | 144(0.1) | 122(0.1) | 22(0.0) | <0.001 | |

| Reactive arthritis | 22(0.0) | 6(0.0) | 16(0.0) | 0.033 | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6193(3.0) | 3994(3.9) | 2199(2.1) | <0.001 | |

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | 919(0.4) | 132(0.1) | 787(0.9) | <0.001 | |

| Malignancy | Any | 35030(17.0) | 17864(17.4) | 17166(16.7) | <0.001 |

| Solid | 29613(14.4) | 14995(14.6) | 14618(14.2) | 0.018 | |

| Hematologic | 5417(2.6) | 2869(2.8) | 2548(2.5) | <0.001 | |

| Breast | 7360(3.6) | 3602(3.5) | 3758(3.7) | 0.064 | |

| CRC | 3468(1.7) | 1768(1.7) | 1700(1.7) | 0.244 | |

| Prostate | 1995(1.0) | 967(0.9) | 1028(1.0) | 0.17 | |

| Lung | 1863(0.9) | 991(1.0) | 872(0.8) | 0.006 | |

| Bladder | 1515(0.7) | 781(0.8) | 734(0.7) | 0.226 | |

| Ovary | 611(0.3) | 329(0.3) | 282(0.3) | 0.057 | |

| Uterus | 1063(0.5) | 509(0.5) | 554(0.5) | 0.166 | |

| Pancreas | 651(0.3) | 313(0.3) | 338(0.3) | 0.326 | |

| CNS | 459(0.2) | 216(0.2) | 243(0.2) | 0.207 | |

| Stomach | 596(0.3) | 306(0.3) | 290(0.3) | 0.512 | |

| Melanoma | 1853(0.9) | 904(0.9) | 949(0.9) | 0.294 | |

| HL | 546(0.3) | 310(0.3) | 236(0.2) | 0.002 | |

| NHL | 2270(1.1) | 1251(1.2) | 1019(1.0) | <0.001 | |

| AL | 462(0.2) | 228(0.2) | 234(0.2) | 0.78 | |

| CL | 556(0.3) | 286(0.3) | 270(0.3) | 0.497 | |

| Kidney | 908(0.4) | 457(0.4) | 451(0.4) | 0.842 | |

| Larynx | 336(0.2) | 174(0.2) | 162(0.2) | 0.512 | |

| Cervix | 1112(0.5) | 590(0.6) | 522(0.5) | 0.041 | |

| Pharynx | 424(0.2) | 232(0.2) | 192(0.2) | 0.052 | |

| Esophagus | 70(0.0) | 34(0.0) | 36(0.0) | 0.811 | |

| Liver / Bile | 512(0.2) | 281(0.3) | 231(0.2) | 0.027 | |

| Thyroid | 1620(0.8) | 820(0.8) | 800(0.8) | 0.618 | |

| Bone | 110(0.1) | 59(0.1) | 51(0.0) | 0.445 | |

| Sarcoma | 490(0.2) | 249(0.2) | 241(0.2) | 0.717 | |

| Genital | 264(0.1) | 143(0.1) | 121(0.1) | 0.175 | |

| MM | 706(0.3) | 348(0.3) | 358(0.3) | 0.706 | |

| PV | 479(0.2) | 231(0.2) | 248(0.2) | 0.437 | |

| MDS | 287(0.1) | 154(0.1) | 133(0.1) | 0.215 | |

| MPS | 111(0.1) | 61(0.1) | 50(0.0) | 0.296 | |

| Other Site | 1071(0.5) | 536(0.5) | 535(0.5) | 0.976 | |

| Unknown Site | 1262(0.6) | 734(0.7) | 528(0.5) | <0.001 | |

Risk for All-Cause Mortality

- ANA characteristics

- The role of concurrent RIRD

| Variable | All Patients | Died | Alive | P-value | |

| (n=102,931) | (N=14,083) | (N=88,848) | |||

| Patient Sex | Male | 27203(26.4) | 5514(39.2) | 21689(24.4) | <0.001 |

| Female | 75728(73.6) | 8569(60.8) | 67159(75.6) | ||

| Age at ANA Test, years | 53.2±18.5 | 72.4±13.0 | 50.1±17.3 | <0.001 | |

| Ethnicity | Jewish | 86448(84.1) | 12609(89.6) | 73839(83.2) | <0.001 |

| Arab | 16334(15.9) | 1466(10.4) | 14868(16.8) | ||

| Smoking | 36305(35.6) | 5920(42.0) | 30385(34.2) | <0.001 | |

| Comorbidities | Diabetes Mellitus | 24858(24.2) | 6450(45.8) | 18408(20.7) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 60028(58.3) | 11490(81.6) | 48538(54.6) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 41138(40.0) | 11167(79.3) | 29971(33.7) | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | 33540(32.6) | 5458(38.8) | 28082(31.6) | <0.001 | |

| Rheumatological immune-related disorders (RIRD). | Any | 11982(11.6) | 1684(12.0) | 10298(11.6) | 0.207 |

| SLE | 4814(4.6) | 769(5.5) | 4045(4.5) | <0.001 | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 839(0.8) | 37(0.3) | 802(0.9) | <0.001 | |

| Systemic sclerosis (diffuse) | 1305(1.3) | 370(2.6) | 935(1.1) | <0.001 | |

| Sjogren | 2015(2.0) | 273(1.9) | 1742(2.0) | 0.86 | |

| Myositis | 122(0.1) | 34(0.2) | 88(0.1) | <0.001 | |

| Reactive arthritis | 6(0.0) | 1(0.0) | 5(0.0) | 0.832 | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3994(3.9) | 585(4.2) | 3409(3.8) | 0.07 | |

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | 132(0.1) | 54(0.1) | 115(0.1) | 0.424 | |

| Malignancy | Any | 17864(17.4) | 6630(47.1) | 11234(12.6) | <0.001 |

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selmi, C.; Ceribelli, A.; Generali, E.; Scirè, C.A.; Alborghetti, F.; Colloredo, G.; Porrati, L.; Achenza, M.I.S.; De Santis, M.; Cavaciocchi, F.; et al. Serum Antinuclear and Extractable Nuclear Antigen Antibody Prevalence and Associated Morbidity and Mortality in the General Population over 15 Years. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 162–166. [CrossRef]

- Stochmal, A.; Czuwara, J.; Trojanowska, M.; Rudnicka, L. Antinuclear Antibodies in Systemic Sclerosis: An Update. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 40–51. [CrossRef]

- Bonroy, C.; Vercammen, M.; Fierz, W.; Andrade, L.E.C.; Hoovels, L.V.; Infantino, M.; Fritzler, M.J.; Bogdanos, D.; Kozmar, A.; Nespola, B.; et al. Detection of Antinuclear Antibodies: Recommendations from EFLM, EASI and ICAP. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2023, 61, 1167–1198. [CrossRef]

- Dinse, G.E.; Parks, C.G.; Weinberg, C.R.; Meier, H.C.S.; Co, C.A.; Chan, E.K.L.; Miller, F.W. Antinuclear Antibodies and Mortality in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999-2004). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185977. [CrossRef]

- Dinse, G.E.; Parks, C.G.; Weinberg, C.R.; Co, C.A.; Wilkerson, J.; Zeldin, D.C.; Chan, E.K.L.; Miller, F.W. Increasing Prevalence of Antinuclear Antibodies in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol. Hoboken NJ 2020, 72, 1026–1035. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-P.; Wang, C.-G.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Guo, D.-L.; Jing, X.-Z.; Yuan, C.-G.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.-M.; Han, M.-S.; et al. The Prevalence of Antinuclear Antibodies in the General Population of China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2014, 76, 116–119. [CrossRef]

- Grainger, D.J.; Bethell, H.W.L. High Titres of Serum Antinuclear Antibodies, Mostly Directed against Nucleolar Antigens, Are Associated with the Presence of Coronary Atherosclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 110–114. [CrossRef]

- Gauderon, A.; Roux-Lombard, P.; Spoerl, D. Antinuclear Antibodies With a Homogeneous and Speckled Immunofluorescence Pattern Are Associated With Lack of Cancer While Those With a Nucleolar Pattern With the Presence of Cancer. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 165. [CrossRef]

- Frost, E.; Hofmann, J.N.; Huang, W.-Y.; Parks, C.G.; Frazer-Abel, A.A.; Deane, K.D.; Berndt, S.I. Antinuclear Antibodies Are Associated with an Increased Risk of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 5231. [CrossRef]

- Im, J.H.; Chung, M.-H.; Park, Y.K.; Kwon, H.Y.; Baek, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, J.-S. Antinuclear Antibodies in Infectious Diseases. Infect. Dis. 2020, 52, 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chang, C. Diagnosis and Classification of Drug-Induced Autoimmunity (DIA). J. Autoimmun. 2014, 48–49, 66–72. [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Ochs, R.L.; Kiyosawa, K.; Furuta, S.; Nakamura, R.M.; Tan, E.M. Nucleolar Antigens and Autoantibodies in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Other Malignancies. Am. J. Pathol. 1992, 140, 859–870.

- Heegaard, N.H.H.; West-Nørager, M.; Tanassi, J.T.; Houen, G.; Nedergaard, L.; Høgdall, C.; Høgdall, E. Circulating Antinuclear Antibodies in Patients with Pelvic Masses Are Associated with Malignancy and Decreased Survival. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e30997. [CrossRef]

- Gendelman, O.; Shapira, R.; Tiosano, S.; Kuntzman, Y.; Tsur, A.M.; Hakimian, A.; Comaneshter, D.; Cohen, A.D.; Buskila, D.; Amital, H. Utilisation of Healthcare Services and Drug Consumption in Fibromyalgia: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Clalit Health Service Database. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14729. [CrossRef]

- ICD - ICD-9-CM - International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Sur, L.M.; Floca, E.; Sur, D.G.; Colceriu, M.C.; Samasca, G.; Sur, G. Antinuclear Antibodies: Marker of Diagnosis and Evolution in Autoimmune Diseases. Lab. Med. 2018, 49, e62–e73. [CrossRef]

- Hurme, M.; Korkki, S.; Lehtimäki, T.; Karhunen, P.J.; Jylhä, M.; Hervonen, A.; Pertovaara, M. Autoimmunity and Longevity: Presence of Antinuclear Antibodies Is Not Associated with the Rate of Inflammation or Mortality in Nonagenarians. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2007, 128, 407–408. [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.L.; Lanna, C.C.D.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Telles, R.W. Recognition and Control of Hypertension, Diabetes, and Dyslipidemia in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 2693–2698. [CrossRef]

- Yazdany, J.; Tonner, C.; Trupin, L.; Panopalis, P.; Gillis, J.Z.; Hersh, A.O.; Julian, L.J.; Katz, P.P.; Criswell, L.A.; Yelin, E.H. Provision of Preventive Health Care in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Data from a Large Observational Cohort Study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12, R84. [CrossRef]

- Bruera, S.; Lei, X.; Zogala, R.; Pundole, X.; Zhao, H.; Giordano, S.H.; Hwang, J.P.; Rauh-Hain, J.A.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E. Cervical Cancer Screening in Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 1796–1803. [CrossRef]

- Cano-Jiménez, E.; Vázquez Rodríguez, T.; Martín-Robles, I.; Castillo Villegas, D.; Juan García, J.; Bollo de Miguel, E.; Robles-Pérez, A.; Ferrer Galván, M.; Mouronte Roibas, C.; Herrera Lara, S.; et al. Diagnostic Delay of Associated Interstitial Lung Disease Increases Mortality in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9184. [CrossRef]

- Kernder, A.; Richter, J.G.; Fischer-Betz, R.; Winkler-Rohlfing, B.; Brinks, R.; Aringer, M.; Schneider, M.; Chehab, G. Delayed Diagnosis Adversely Affects Outcome in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Cross Sectional Analysis of the LuLa Cohort. Lupus 2021, 30, 431–438. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, R.; Quintana, R.; Zavala-Flores, E.; Serrano, R.; Roberts, K.; Catoggio, L.J.; García, M.A.; Berbotto, G.A.; Saurit, V.; Bonfa, E.; et al. Time to Diagnosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Associated Factors and Its Impact on Damage Accrual and Mortality. Data from a Multi-Ethnic, Multinational Latin American Lupus Cohort. Lupus 2024, 33, 340–346. [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.R.; Baek, H.L.; Yoon, H.H.; Ryu, H.J.; Choi, H.-J.; Baek, H.J.; Ko, K.-P. Delayed Diagnosis Is Linked to Worse Outcomes and Unfavourable Treatment Responses in Patients with Axial Spondyloarthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 34, 1397–1405. [CrossRef]

- Danve, A.; Deodhar, A. Axial Spondyloarthritis in the USA: Diagnostic Challenges and Missed Opportunities. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 625–634. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.E.C.; Damoiseaux, J.; Vergani, D.; Fritzler, M.J. Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA) as a Criterion for Classification and Diagnosis of Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2022, 5, 100145. [CrossRef]

- Schönau, J.; Wester, A.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Hagström, H. Risk of Cancer and Subsequent Mortality in Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Population-Based Cohort Study of 3052 Patients. Gastro Hep Adv. 2023, 2, 879–888. [CrossRef]

- Dellavance, A.; Viana, V.S.T.; Leon, E.P.; Bonfa, E.S.D.O.; Andrade, L.E.C.; Leser, P.G. The Clinical Spectrum of Antinuclear Antibodies Associated with the Nuclear Dense Fine Speckled Immunofluorescence Pattern. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 32, 2144–2149.

- Mariz, H.A.; Sato, E.I.; Barbosa, S.H.; Rodrigues, S.H.; Dellavance, A.; Andrade, L.E.C. Pattern on the Antinuclear Antibody-HEp-2 Test Is a Critical Parameter for Discriminating Antinuclear Antibody-Positive Healthy Individuals and Patients with Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 191–200. [CrossRef]

- Ochs, R.L.; Mahler, M.; Basu, A.; Rios-Colon, L.; Sanchez, T.W.; Andrade, L.E.; Fritzler, M.J.; Casiano, C.A. The Significance of Autoantibodies to DFS70/LEDGFp75 in Health and Disease: Integrating Basic Science with Clinical Understanding. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 16, 273–293. [CrossRef]

- Nisihara, R.; Machoski, M.C.C.; Neppel, A.; Maestri, C.A.; Messias-Reason, I.; Skare, T.L. Anti-Nuclear Antibodies in Patients with Breast Cancer. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 193, 178–182. [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Rojas, H.; Banerjee, H.; Cabrera, I.B.; Perez, K.Y.; León, M.D.; Casiano, C.A. Expression of the Stress Response Oncoprotein LEDGF/P75 in Human Cancer: A Study of 21 Tumor Types. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e30132. [CrossRef]

- Vlagea, A.; Falagan, S.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, G.; Moreno-Rubio, J.; Merino, M.; Zambrana, F.; Casado, E.; Sereno, M. Antinuclear Antibodies and Cancer: A Literature Review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 127, 42–49. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Adjusted HR b | 95% CI | Pv | |

| Positive ANA Antibody | 4.79 | 4.66-4.92 | <0.001 | |

| ANA Pattern | No ANA Antibody | Reference | ||

| Centromere | 17.54 | 15.00-20.51 | <0.001 | |

| Cytoplasmatic | 20.97 | 18.77-23.43 | <0.001 | |

| DFS | 29.77 | 26.58-33.34 | <0.001 | |

| Homogenous | 12.95 | 12.03-13.94 | <0.001 | |

| Mitochondrial | 36.14 | 29.78-43.85 | <0.001 | |

| Mixed | 9.71 | 9.08-10.37 | <0.001 | |

| Nuclear | 8.06 | 7.54-8.61 | <0.001 | |

| Speckled | 12.54 | 11.95-13.15 | <0.001 | |

| ANA Titer | No ANA Antibody | |||

| 1:40 | 4.7 | 4.53-4.88 | <0.001 | |

| 1:80 | 2.54 | 2.40-2.69 | <0.001 | |

| 1:160 | 4.17 | 3.94-4.41 | <0.001 | |

| 1:320 | 3.72 | 3.19-4.33 | <0.001 | |

| 1:640 | 3.64 | 2.93-4.52 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).