Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

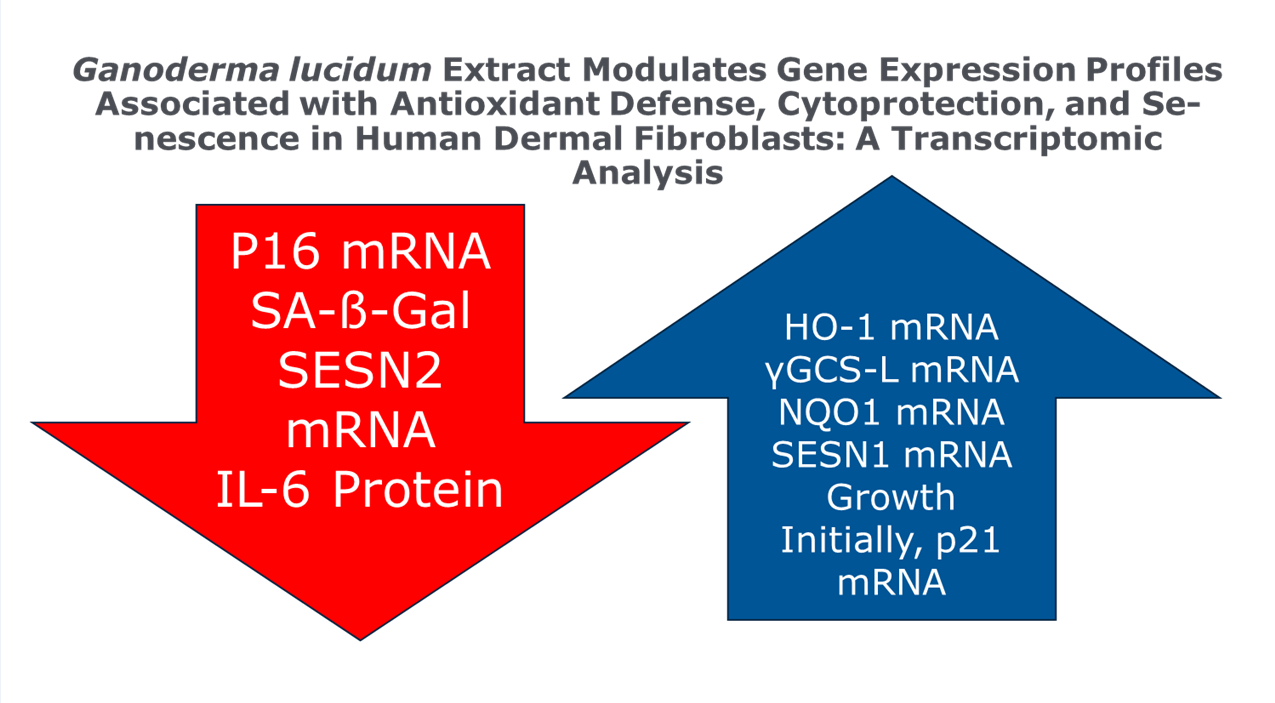

Cellular senescence plays a crucial role in skin aging, with senescent dermal fibroblasts contributing to reduced skin elasticity and increased inflammation. This study investigated the potential of Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) extract to modulate the senescent phenotype of human dermal fibroblasts. Etoposide-induced senescent fibroblasts were treated with Reishi extracts from two commercial sources for 14 days. Gene expression analysis was performed using qPCR to assess markers of senescence, antioxidant defense, and extracellular matrix remodeling. Results showed that Reishi extracts significantly upregulated antioxidant and cytoprotective genes, including HO-1, γGCS-L, and NQO1, compared to untreated controls. Importantly, Reishi treatment suppressed the expression of p16, a key marker of cellular senescence, while transiently upregulating p21. The extracts also demonstrated potential senolytic properties, reducing the percentage of senescent cells as measured by SA-β-Gal staining. However, Reishi treatment did not mitigate the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP1) induced by senescence. These findings suggest that Ganoderma lucidum extract may help alleviate some aspects of cellular senescence in dermal fibroblasts, primarily through enhanced antioxidant defense and cytoprotection, potentially offering a novel approach to combat skin aging.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Definition of Reagents

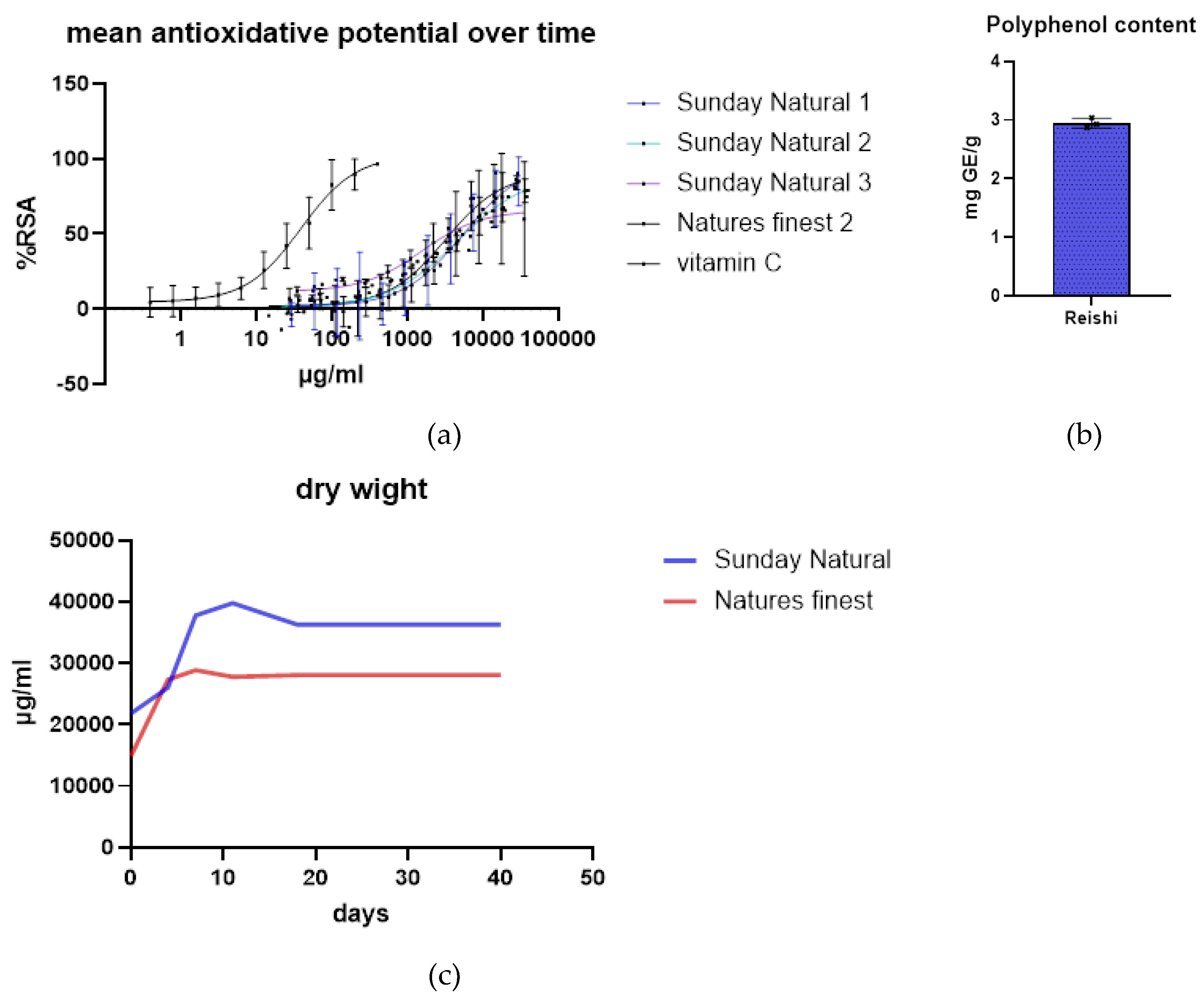

2.1.1. Mushroom Extracts

2.1.2. Cells

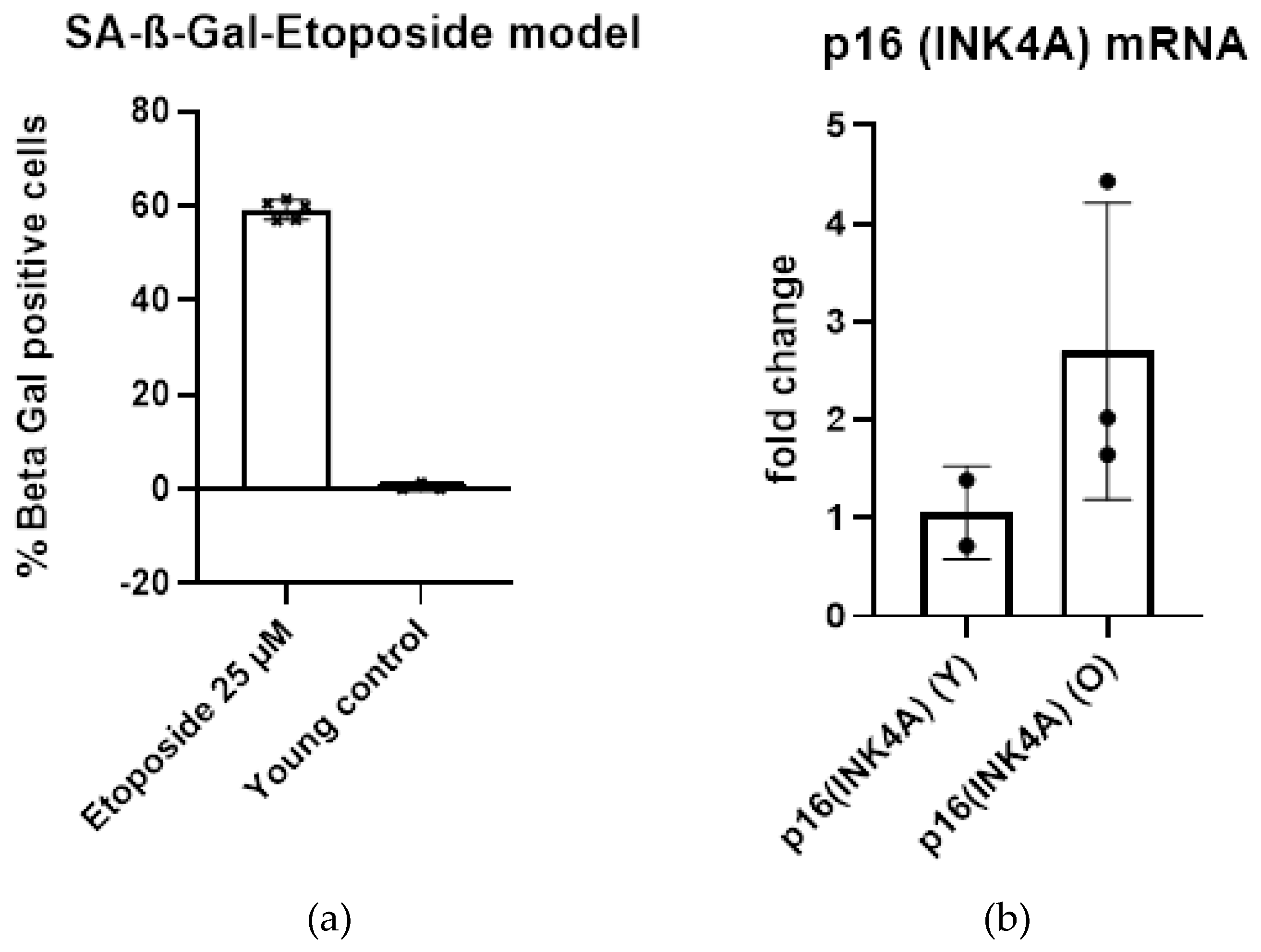

2.1.3. Definition of Senescent State

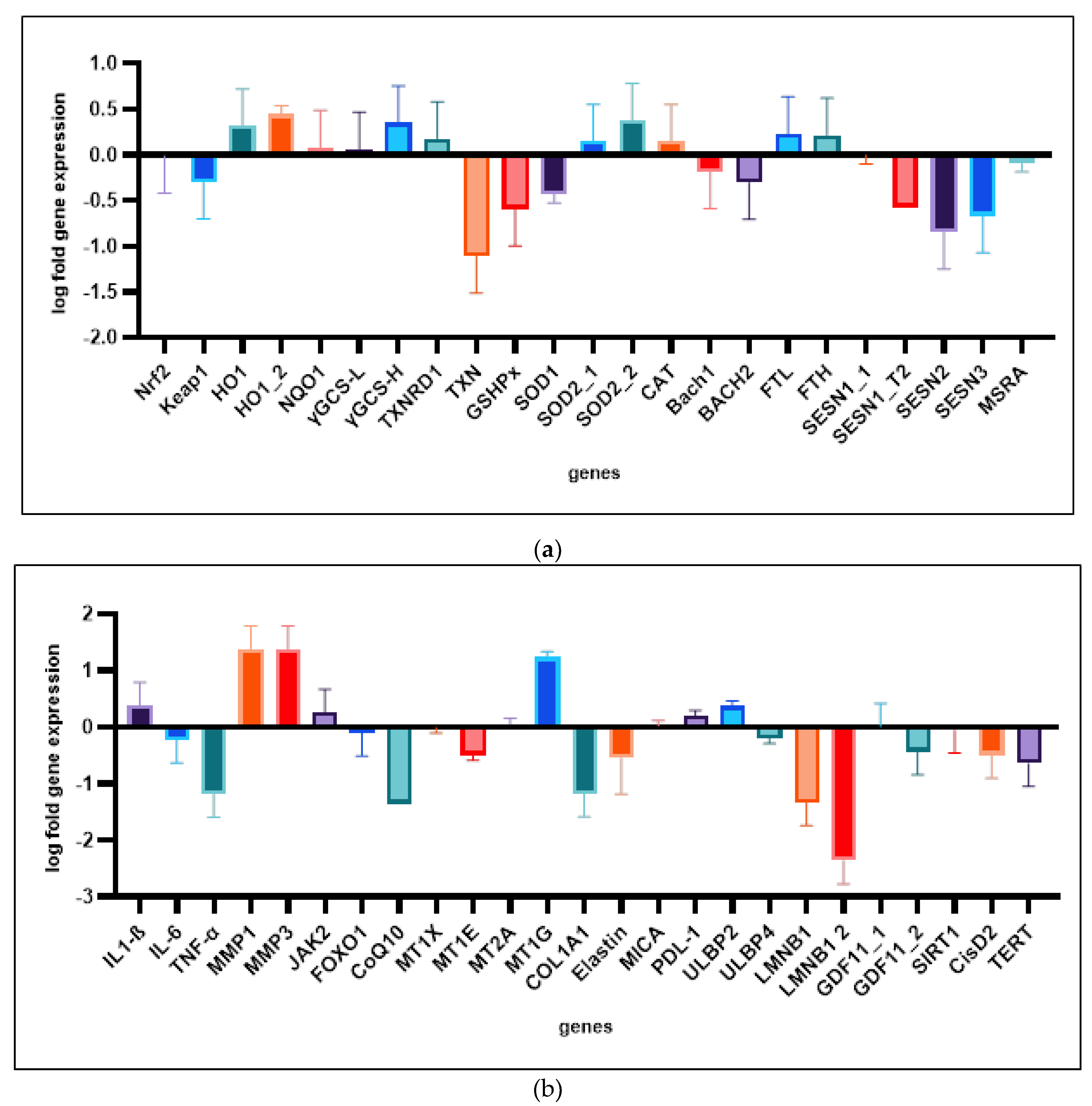

2.1.4. Expression of Relevant Genes in Etoposide Senescent Cells

2.1.5. Growth Curves

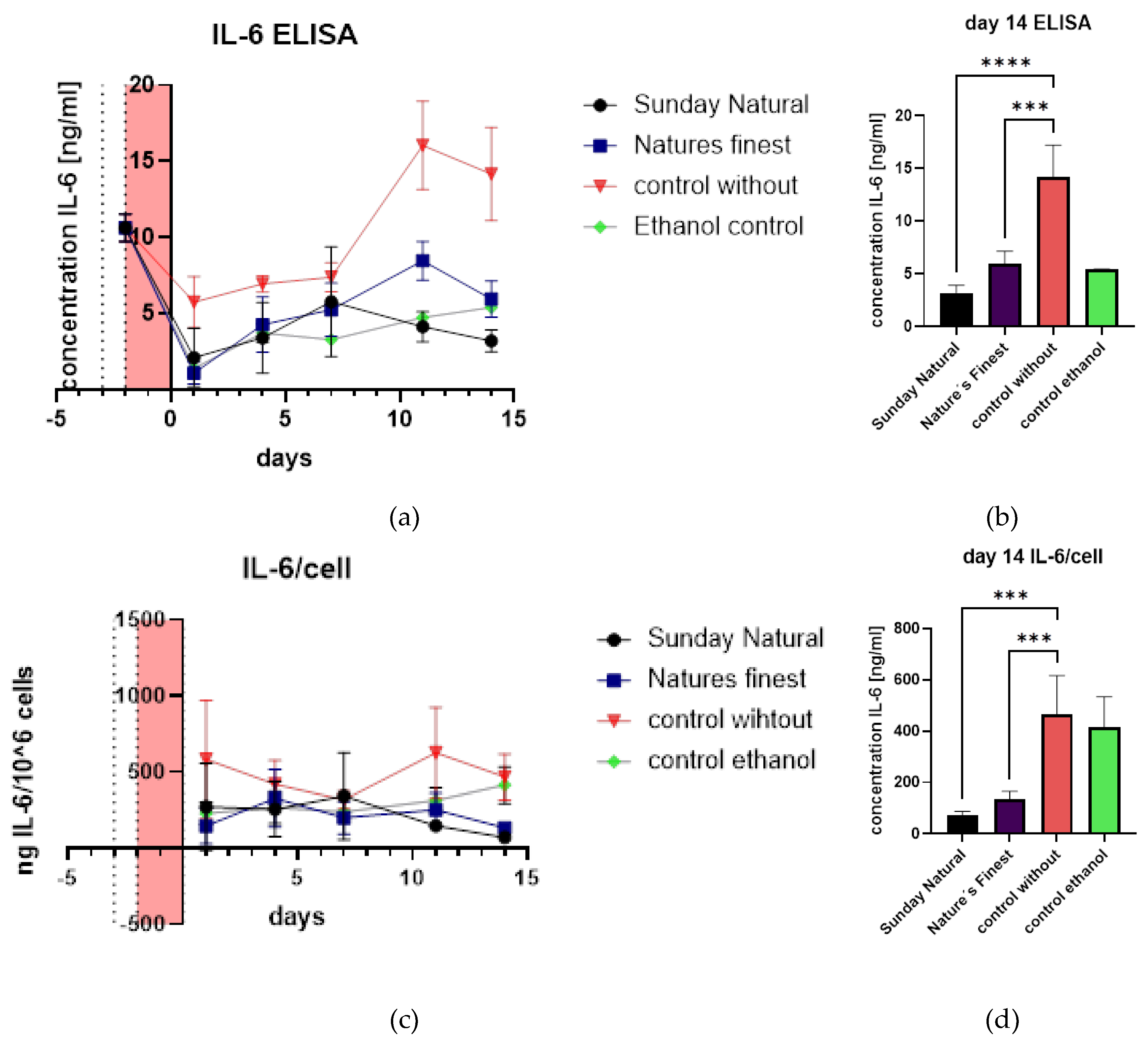

2.2. Ganoderma Lucidum and the SASP Senomorphic Properties

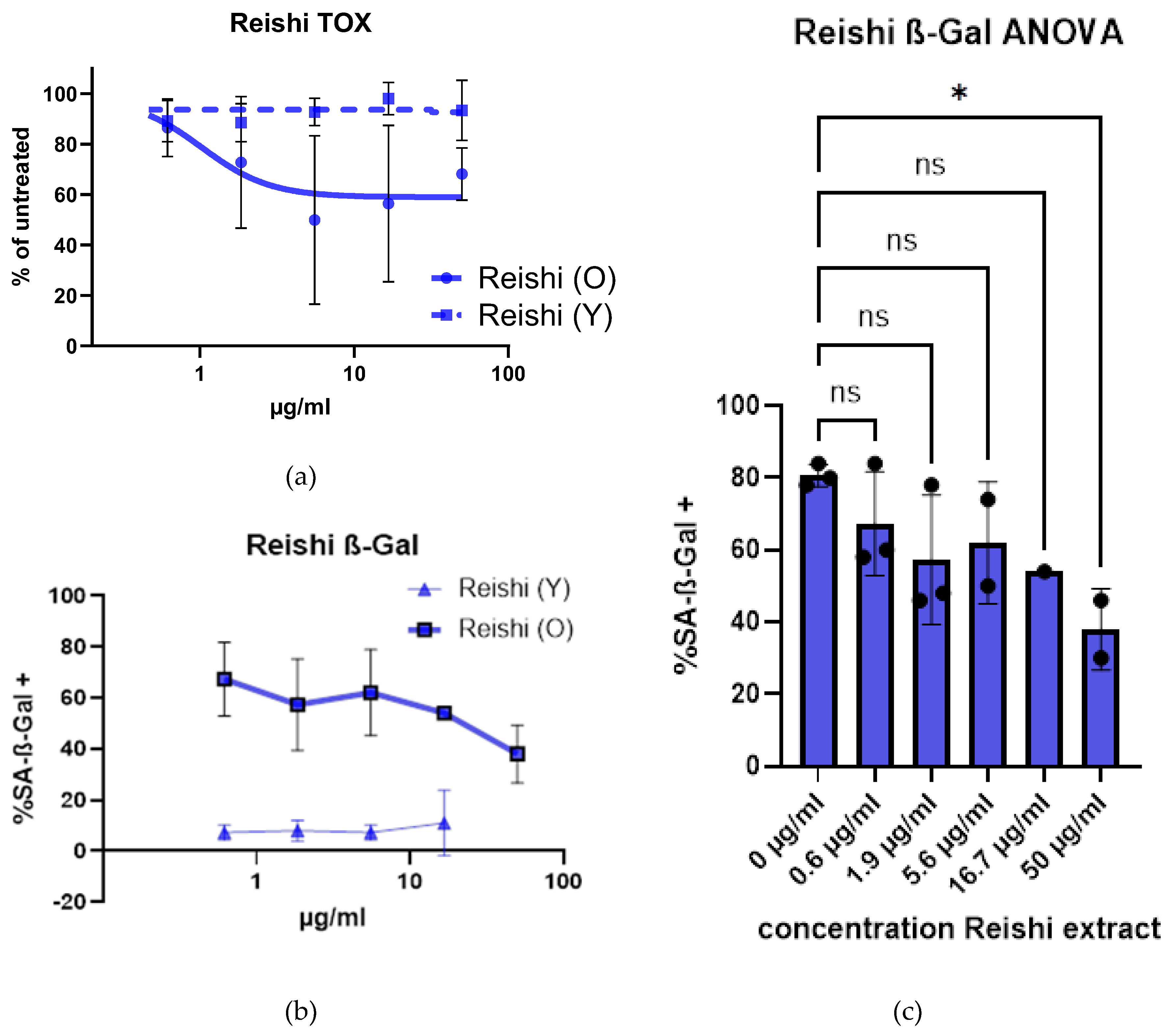

2.3. Senolyotic Properties of Reishi

2.4. Analysis of Gene Expression

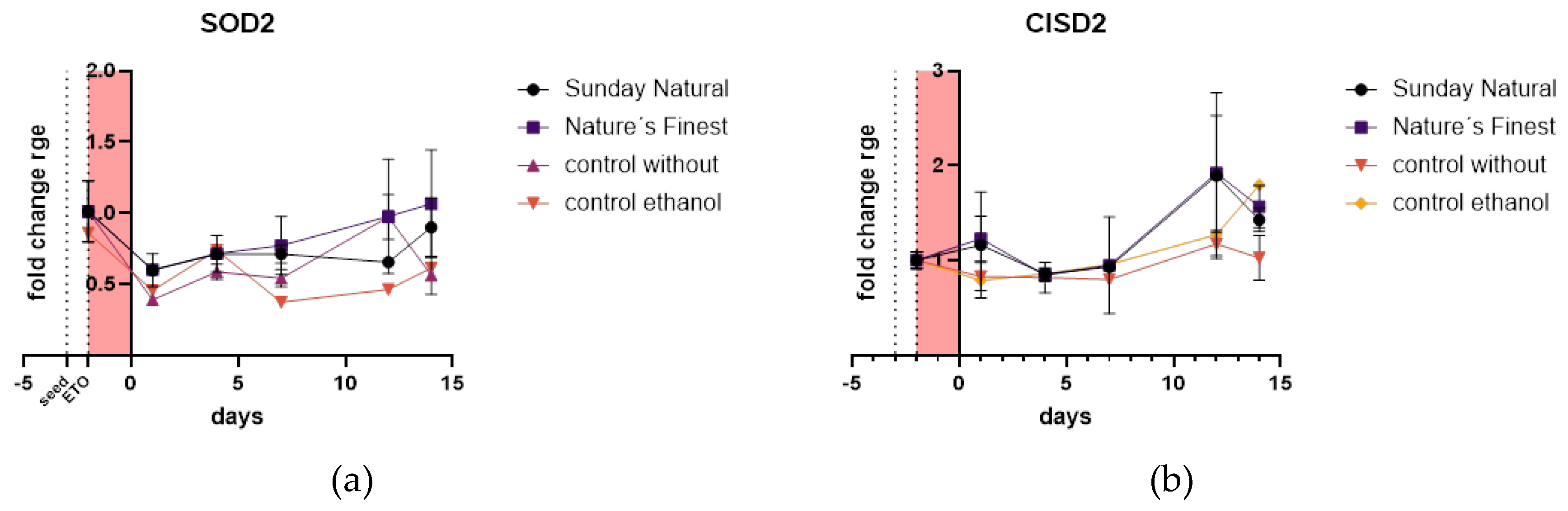

2.4.1. Superoxide Dismutase 2, Mitochondrial (SOD2) and CDGSH iron-Sulfur Domain-Containing Protein 2 (CISD2) Are Not Affected Neither by Etoposide Treatment Nor by Treatment with Reishi Extracts

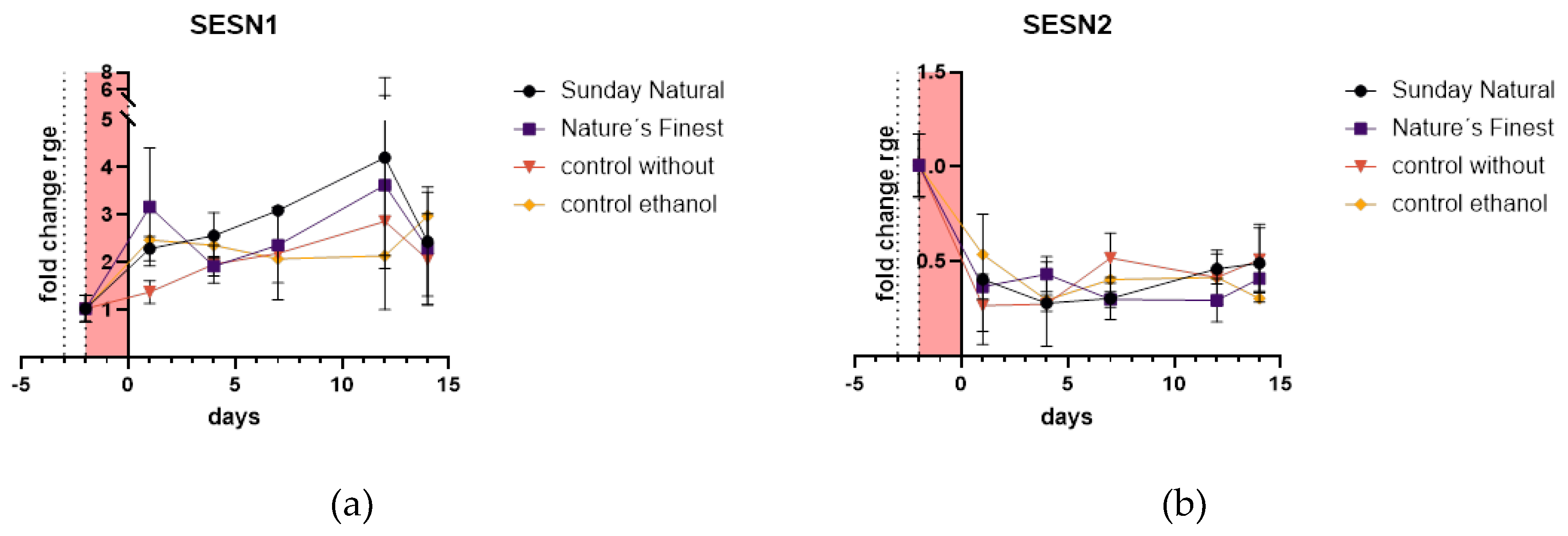

2.4.2. Sestrins 1 and 2 are Regulated in Different Directions

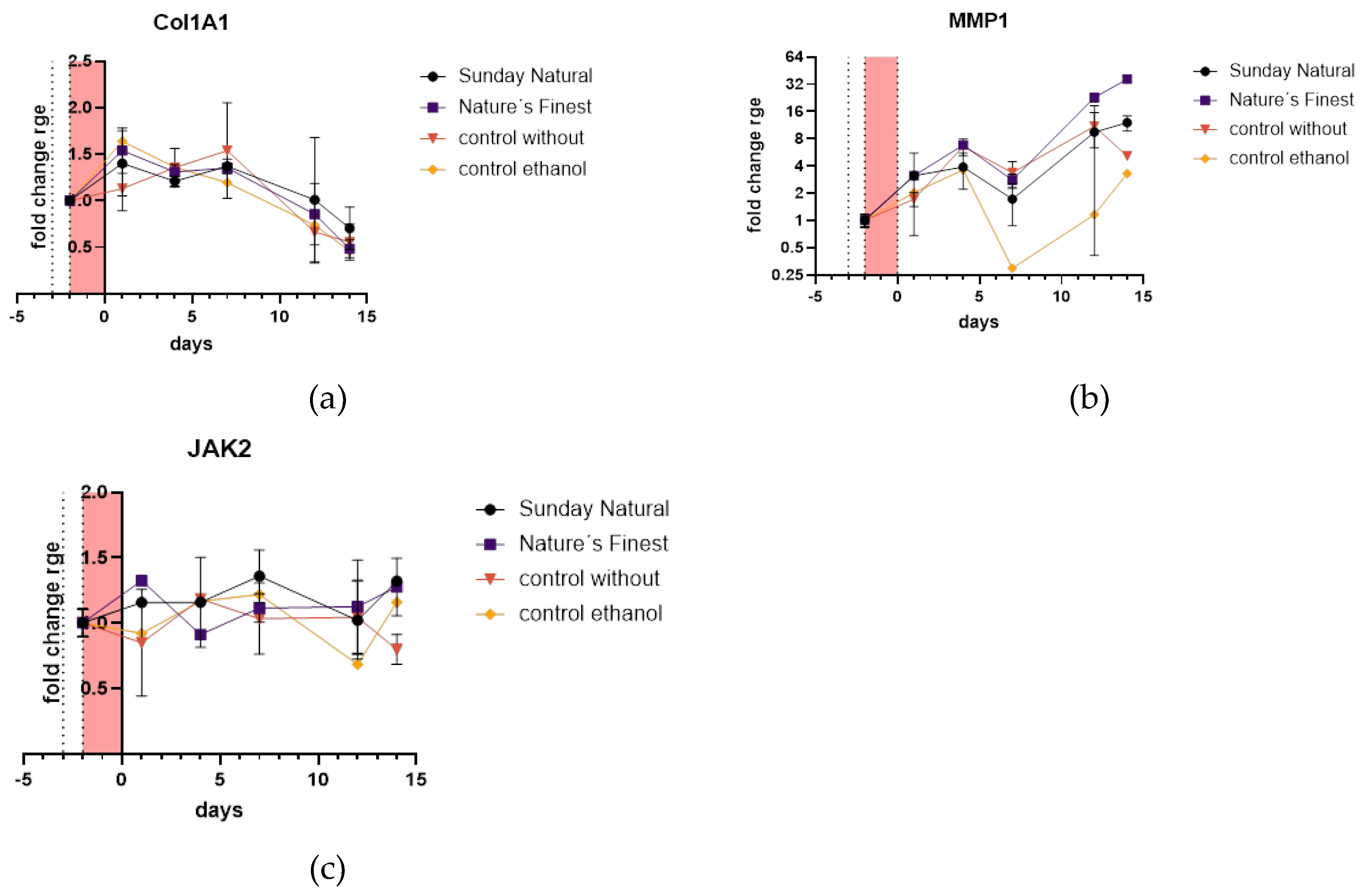

2.4.3. Extracellular Matrix Related Genes Are Not Differentially Expressed Between Control and Reishi Treated Groups

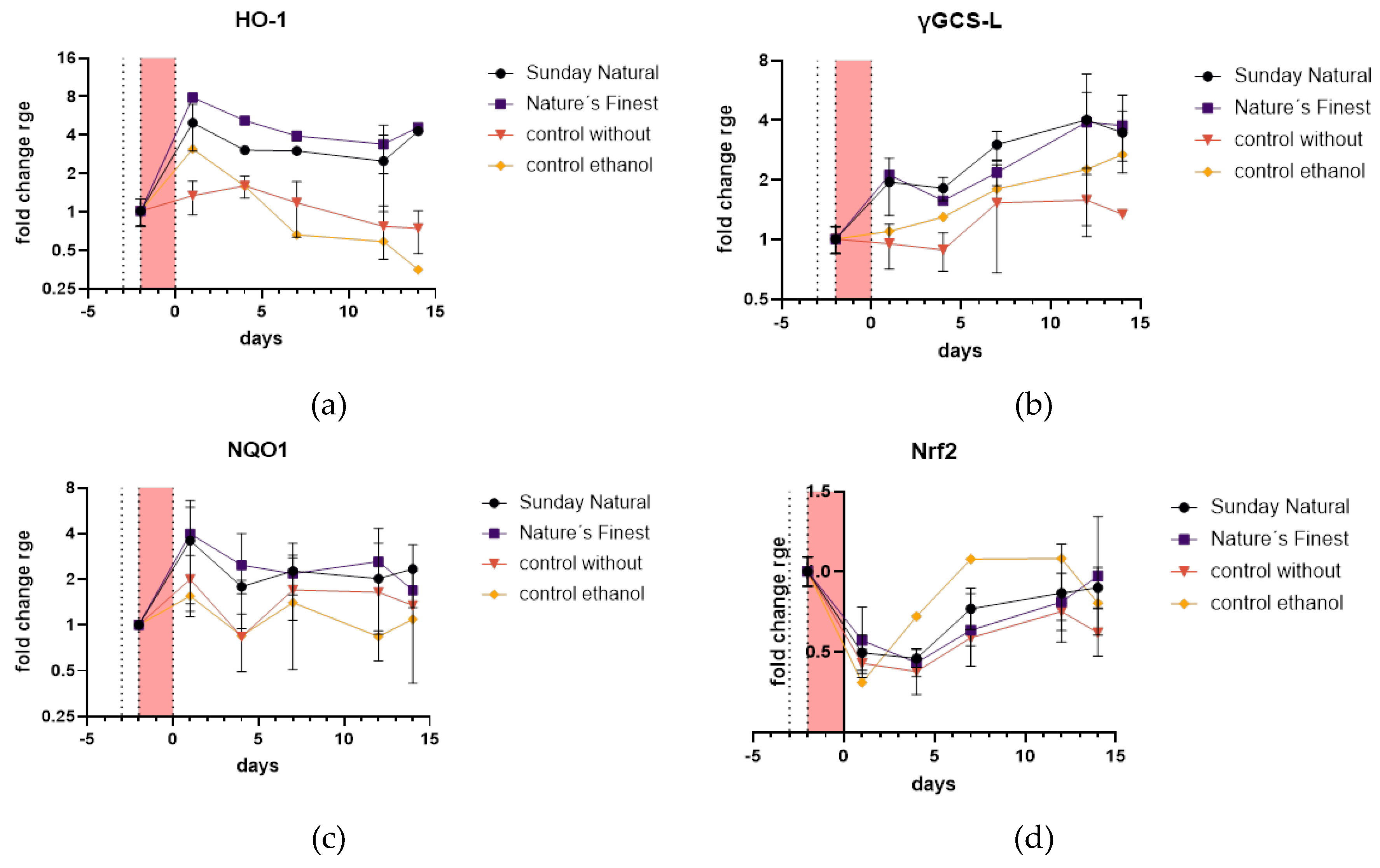

2.4.4. Antioxidant Defense and Cytoprotection of HDF is Upregulated

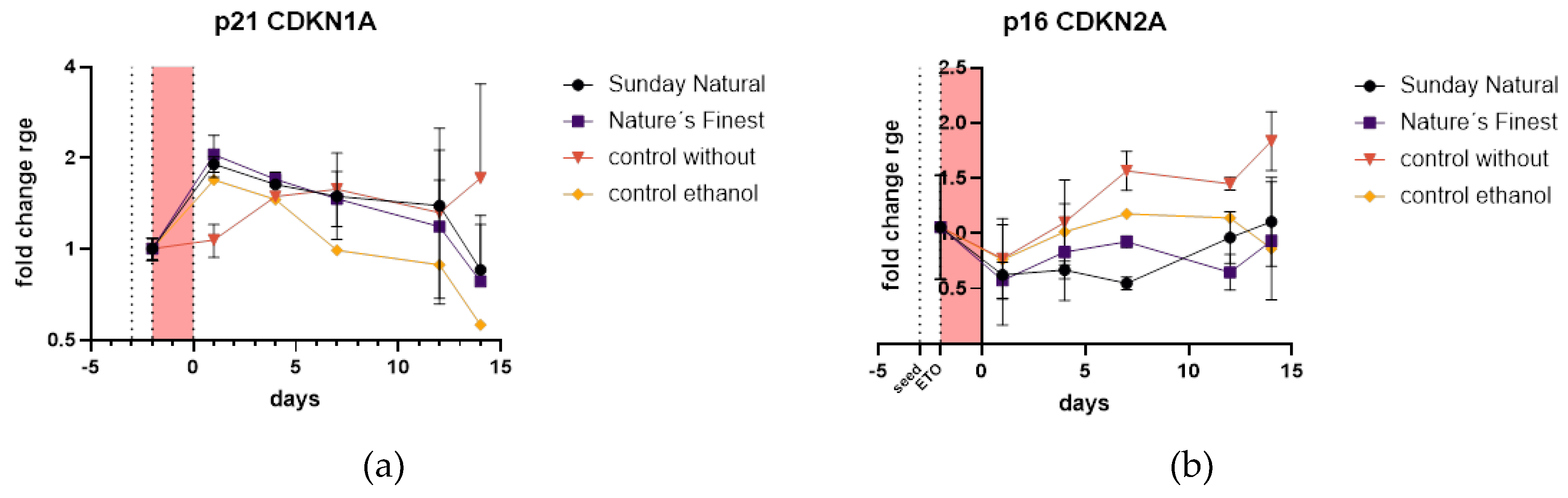

2.4.5. Reishi is Downregulating p16 Expression and Initiates Early Upregulation of p21

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Definition of Reagents

4.1.1. Preparation of Extract and Standard Substances

4.1.2. Dry Matter Determination

4.1.3. DPPH-Assay

4.2. Cell Culture

4.2.1. Medium Preparation

4.2.2. Cells

(2))

(2))4.2.3. Thawing of Cells

4.2.4. Passaging/Harvesting of Cells

4.2.5. Freezing of Cells

4.2.6. Cell Counting

4.2.7. PrestoBlue™-Assay

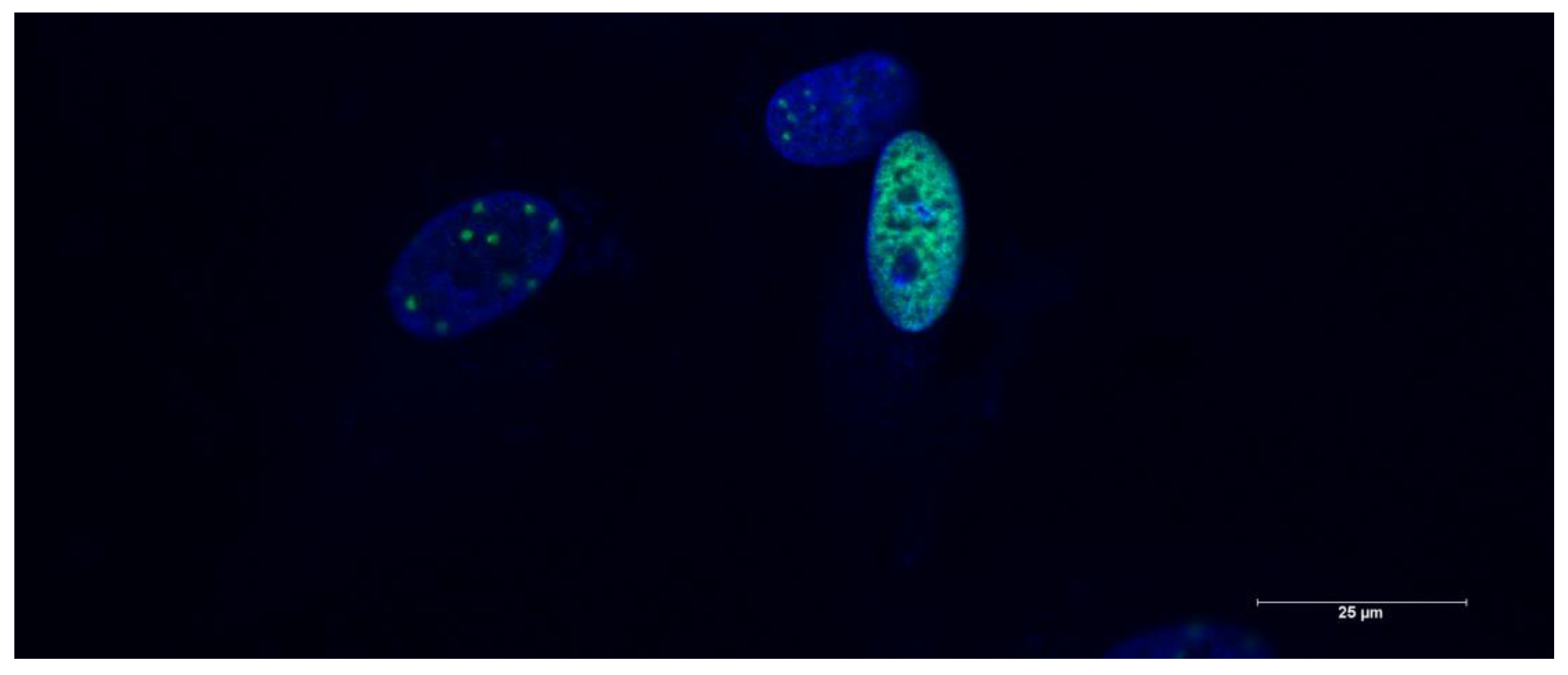

4.2.8. Phospho-Histone H2A.X assay

4.2.9. Senescence Model

4.2.10. Main Experiment

4.2.11. IL-6 ELISA

4.3. qPCR-Analysis

4.3.1. RNA-Extraction

4.3.2. Measurement of RNA and DNA

4.3.3. cDNA-Synthesis

4.3.4. Core Procedure

4.3.4.1. Primer Preparation

4.3.4.2. qPCR Execution and Evaluation

4.3.5. Screening of Genes

4.3.5.1. Comparison of Gene Expression Between Young and Old Cells

4.3.5.2. Further Evaluation through Standard Curves

4.3.6. Main Experiment

4.4. Statistics

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayflick, L. The Limited in Vitro Lifetime of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 1965, 37, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The Serial Cultivation of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp Cell Res 1961, 25, 585–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, M.C.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J. Senescent Cells and Their Secretory Phenotype as Targets for Cancer Therapy. In Cancer and Aging: From Bench to Clinics; 2013 ISBN 9783318023077.

- Zorina, A.; Zorin, V.; Isaev, A.; Kudlay, D.; Vasileva, M.; Kopnin, P. Dermal Fibroblasts as the Main Target for Skin Anti-Age Correction Using a Combination of Regenerative Medicine Methods. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.; Er Lee, X.; Yi Ng, P.; Lee, Y.; Dreesen, O. The Role of Cellular Senescence in Skin Aging and Age-Related Skin Pathologies. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Herranz, N.; Gil, J. Mechanisms and Functions of Cellular Senescence. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2018, 128, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Micco, R.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Baker, D.; dAdda di Fagagna, F. Cellular Senescence in Ageing: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. [CrossRef]

- Waters, D.W.; Schuliga, M.; Pathinayake, P.S.; Wei, L.; Tan, H.-Y.; Blokland, K.E.C.; Jaffar, J.; Westall, G.P.; Burgess, J.K.; Prêle, C.M.; et al. A Senescence Bystander Effect in Human Lung Fibroblasts. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N. V; Velichko, A.K.; Razin, S. V; Kantidze, O.L. Small Molecule Compounds That Induce Cellular Senescence. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühnel, H.; Pasztorek, M.; Kuten-Pella, O.; Kramer, K.; Bauer, C.; Lacza, Z.; Nehrer, S. Effects of Blood-Derived Products on Cellular Senescence and Inflammatory Response: A Study on Skin Rejuvenation. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 1865–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imb, M.; Véghelyi, Z.; Maurer, M.; Kühnel, H. Exploring Senolytic and Senomorphic Properties of Medicinal Plants for Anti-Aging Therapies. J. Mol. Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeh, A.; Dronina, M.; Domankevich, V.; Shams, I.; Manov, I. Downregulation of the Inflammatory Network in Senescent Fibroblasts and Aging Tissues of the Long-Lived and Cancer-Resistant Subterranean Wild Rodent, Spalax. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georget, M.; Defois, A.; Guiho, R.; Bon, N.; Allain, S.; Boyer, C.; Halgand, B.; Waast, D.; Grimandi, G.; Fouasson-Chailloux, A.; et al. Development of a DNA Damage-Induced Senescence Model in Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. Aging 2023, 15, 8576–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Man, M.; Hu, L. Aging in the Dermis: Fibroblast Senescence and Its Significance. Aging Cell 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Hickson, L.J.; Eirin, A.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lerman, L.O.; Kogod, A. Cellular Senescence: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022, 18, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousis, L.; Kanavaros, P.; Barbouti, A. Oxidative Stress-Induced Cellular Senescence: Is Labile Iron the Connecting Link? Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandita H; Manohar M; Gowda DV Recent Review on Oxidative Stress, Cellular Senescence and Age-Associated Diseases. International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 11, 1331–1342. [CrossRef]

- Cuong, V.T.; Chen, W.; Shi, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, N.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Yang, P.; Fei, J. The Anti-Oxidation and Anti-Aging Effects of Ganoderma Lucidum in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Exp Gerontol 2019, 117, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Xu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Xiao, J. Ganoderic Acid D Prevents Oxidative Stress-induced Senescence by Targeting 14-3-3ε to Activate CaM / CaMKII / NRF2 Signaling Pathway in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Aging Cell 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Y.-J.; Xiao, J.-H. Ganoderic Acid D Protects Human Amniotic Mesenchymal Stem Cells against Oxidative Stress-Induced Senescence through the PERK/NRF2 Signaling Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.A.; Zhang, M.; Yin, F.; Maines, M.D. Heme Oxygenase-1, Oxidation, Inflammation, and Atherosclerosis. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Zheng, M.; Kim, S.-K.; Cho, J.J.; Shin, C.H.; Joe, Y.; Chung, H.T. CO/HO-1 Induces NQO-1 Expression via Nrf2 Activation. Immune Netw 2011, 11, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoaty, A.A.A.; Chen, J.; Zhang, K.; Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Xu, J. Senolytic Effect of Triterpenoid Complex from Ganoderma Lucidum on Adriamycin-Induced Senescent Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Model in Vitro and in Vivo. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanqing, S.; Yishi, W.; Yang, Z.; Nanhu, Q. The Emerging Role of Sestrin2 in Cell Metabolism, and Cardiovascular and Age-Related Diseases. Aging Dis 2020, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Han, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Sestrin2 as a Gatekeeper of Cellular Homeostasis: Physiological Effects for the Regulation of Hypoxia-related Diseases. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 5341–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Mercado, V.J.; Fridley, B.L.; Saligan, L.N. Sestrin Family of Genes and Their Role in Cancer-Related Fatigue. Supportive Care in Cancer 2018, 26, 2071–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Hammerberg, C.; Li, Y.; He, T.; Quan, T.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Expression of Catalytically Active Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 in Dermal Fibroblasts Induces Collagen Fragmentation and Functional Alterations That Resemble Aged Human Skin. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, T.; Kapila, Y.L.; Kapila, S. MMP-1 (Collagenase-1) and MMP-13 (Collagenase-3) Differentially Regulate Markers of Osteoblastic Differentiation in Osteogenic Cells. Matrix Biology 2008, 27, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milara, J.; Hernandez, G.; Ballester, B.; Morell, A.; Roger, I.; Montero, P.; Escrivá, J.; Lloris, J.M.; Molina-Molina, M.; Morcillo, E.; et al. The JAK2 Pathway Is Activated in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Respir Res 2018, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvennoinen, O.; Hubbard, S.R. Molecular Insights into Regulation of JAK2 in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Blood 2015, 125, 3388–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T. Senolytic Drugs: From Discovery to Translation. J Intern Med 2020, 288, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Tan, K.M.; Wong, P.F.; Murugan, D.D.; Hu, Z.; Lin, Y. Exploring the Perspectives of Pharmaceutical Experts and Healthcare Practitioners on Senolytic Drugs for Vascular Aging-Related Disorder: A Qualitative Study. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Segura, A.; Rubingh, R.; Demaria, M. Identification of Stable Senescence-associated Reference Genes. Aging Cell 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marionnet, C.; Pierrard, C.; Lejeune, F.; Sok, J.; Thomas, M.; Bernerd, F. Different Oxidative Stress Response in Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts of Reconstructed Skin Exposed to Non Extreme Daily-Ultraviolet Radiation. PLoS One 2010, 5, e12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, J.; Bhatt, P. Flavonoids Derived from Abelmoschus Esculentus AttenuatesUV-B Induced Cell Damage in Human Dermal Fibroblasts ThroughNrf2-ARE Pathway. Pharmacogn Mag 2016, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcheggiani, F.; Kordes, S.; Cirilli, I.; Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Vogelsang, A.; Möller, N.; Blatt, T.; Weise, J.M.; Damiani, E.; et al. Anti-Ageing Effects of Ubiquinone and Ubiquinol in a Senescence Model of Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med 2021, 165, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporarello, N.; Meridew, J.A.; Jones, D.L.; Tan, Q.; Haak, A.J.; Choi, K.M.; Manlove, L.J.; Prakash, Y.S.; Tschumperlin, D.J.; Ligresti, G. PGC1α Repression in IPF Fibroblasts Drives a Pathologic Metabolic, Secretory and Fibrogenic State. Thorax 2019, 74, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, S.R.; Sivaprakasam, T.O.; Mishra, A.; Kumar, L.M.S.; Prakash, N.S.; Prabhu, S.; Ramakrishnan, S. Protective Effects of Triphala on Dermal Fibroblasts and Human Keratinocytes. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0145921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, E.-M.; Lee, G.; Lim, C.-H.; Kwon, K.B.; Kim, J.-M.; Song, H.-K.; Yang, H.J.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.-R. Protective Effects of Evodiae Fructus Extract against Ultraviolet-Induced MMP-1 and MMP-3 Expression in Human Dermal Fibroblasts. J Herb Med 2022, 35, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Chiang, T.-H.; Chen, W.-J.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lin, M.-S. CISD2 Serves a Novel Role as a Suppressor of Nitric Oxide Signalling and Curcumin Increases CISD2 Expression in Spinal Cord Injuries. Injury 2015, 46, 2341–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.-L.; Lee, S.-I.; Park, H.-W.; Lee, S.K.; Kim, T.-H.; Kang, J.; Park, S.-R. SIRT1 Suppresses in Vitro Decidualization of Human Endometrial Stromal Cells through the Downregulation of Forkhead Box O1 Expression. Reprod Biol 2022, 22, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Yin, W.; Tang, F.; He, M. Pan-Cancer Analysis of TERT and Validation in Osteosarcoma Cell Lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023, 639, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, J.; Mazza, T.; Sobolewski, C.; Foti, M.; Vinciguerra, M. GDF11 Rapidly Increases Lipid Accumulation in Liver Cancer Cells through ALK5-Dependent Signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2021, 1866, 158920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Pang, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Human Dermal Fibroblast Effectively Ameliorate Skin Photoaging via MiRNA-22-5p-GDF11 Axis. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 452, 139553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, A.; Laberge, R.-M.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J. Lamin B1 Loss Is a Senescence-Associated Biomarker. Mol Biol Cell 2012, 23, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, A.; Laberge, R.-M.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J. Lamin B1 Loss Is a Senescence-Associated Biomarker. Mol Biol Cell 2012, 23, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, E.L.; Araki, M.; Hironaka, Y.; Mori, S.; Tan, T.Z.; Morishita, S.; Edahiro, Y.; Ohsaka, A.; Komatsu, N. Identification of AIM2 as a Downstream Target of JAK2V617F. Exp Hematol Oncol 2015, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, A.; Krizhanovsky, V. Immunosurveillance of Senescent Cells: The Bright Side of the Senescence Program. Biogerontology 2013, 14, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisbrich, M.; Chevalier, N.; Sehnert, B.; Rizzi, M.; Venhoff, N.; Thiel, J.; Voll, R.E. CMTM6-Deficient Monocytes in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis Fail to Present the Immune Checkpoint PD-L1. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, B. GDF11 Ameliorates Severe Acute Pancreatitis through Modulating Macrophage M1 and M2 Polarization by Targeting the TGFβR1/SMAD-2 Pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2022, 108, 108777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavreva, D.A.; Varticovski, L.; Levkova, L.; George, A.A.; Davis, L.; Pegoraro, G.; Blazer, V.; Iwanowicz, L.; Hager, G.L. Novel Cell-Based Assay for Detection of Thyroid Receptor Beta-Interacting Environmental Contaminants. Toxicology 2016, 368–369, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Priming | Reverse Transcription | Inactivation | Hold | |

| Temperature [°C] | 25 | 46 | 95 | 4 |

| Duration [min] | 5 | 20 | 1 | 10 |

| Polymerase activation | Denaturation | Annealing | |

| Temperature [°C] | 95 | 95 | 60 |

| Duration [sec] | 30 | 5 | 30 |

| Cycles | 1 | 40 | |

| Gene name | Forward sequence (5´-3´) | Backwards sequence (5´-3´) | Ref. |

| TUBA1A1 | CTTCGTCTCCGCCATCAG | CGTGTTCCAGGCAGTAGAGC | [33] |

| VAMP7 | CAAACATGCTTGGTGTGGAG | AAATTAAAGGCTCGGGAACG | [33] |

| TMEM199 | CACCAGCATCTGAGAGAAAGG | CCGTGGAGGCTTCACAAC | [33] |

| L3MBTL2 | CCAAGACCAAGAGGTTCTGC | TTTGGTCGGTGGTTTTCC | [33] |

| NRF2 | CGGTATGCAACAGGACATTG | GTTGGGGTCTTCTGTGGAGA | [34] |

| KEAP1 | CACAGCAATGAACACCATCC | TGTGACCATCATAGCCTCCA | [34] |

| BACH1 | TGTGCTTAGAGAAGGATGCTGCTC | TCTTCGTTTCTTCAGGTTCCATTGC | [34] |

| HO-1 1 | GAGACGGCTTCAAGCTG | GTGTGTAGGGGATGACC | [34] |

| HO-1 2 | GAGGAGTTGCAGGAGCTGCT | GAGTGTAAGGACCCATCGGA | [35] |

| FTL | TCTCGGCCATCTCCTGCTTCTG | CGCCTTCCAGAGCCACATCATC | [34] |

| FTH | GCCGCCGCCTCTCCTTAGTC | CAGTTTCTCAGCATGTTCCCTCTCC | [34] |

| NQO1 | CGGCTTTGAAGAAGAAAGG | CTCGGCAGGATACTGAA | [34] |

| γ GCS-L | TCACCTCCTATTGAAGATGG | GGTTACTATTTGGTTTTACCTGT | [34] |

| γ GCS-H | GCAGAGGAGTACACCC | CCACTTCCATGTTTTCAAGG | [34] |

| TXNRD1 | CCTATGTCGCTTTGGAG | CCCTACGGTTTCTAAGCC | [34] |

| TXN | CTGCTTTTCAGGAAGCCTTG | ACCCACCTTTTGTCCCTTCT | [34] |

| GSHPx | GGCTACTCTCTCGTTTCCTTTC | GTTCTTGGCGTTCTCCTACAG | [34] |

| SOD1 | AGTGCAGGGCATCATCAATTTCGAGCAG | GATGCAATGGTCTCCTGAGAGTGAGATC | [34] |

| SOD2 1 | GTCACCGAGGAGAAGTACCAGGAG | CACCAACAGATGCAGCCGTCAG | [34] |

| CAT | CATTCGATCTCACCAAGGTTTGGCC | AGCACGGTAGGGACAGTTCACAGG | [34] |

| SESN1-T1 | GGCAAACCATTTTGAGGAAA | TGGTCCCTGTCCTAGTGGTC | [34] |

| SESN1-T2 | GCTGGGCTGCAAGCAGTG | CCAAGTTCCTCGTCCTGGT | [34] |

| SESN2 | GCACCTACACCCCCTAGTGA | GTCTTCCACAAAGCACAGCA | [34] |

| SESN3 | AGTGCTGCGGAAGGATAAAA | CCATGCGCAACATGTAAAAC | [34] |

| Col1A1 1 | AGACATCCCACCAATCACCTG | GGCAGTTCTTGGTCTCGTCAC | [36] |

| Col1A1 2 | AAGGGACACAGAGGTTTCAGTGG | CAGCACCAGTAGCACCATCATTTC | [37] |

| ELN | GCCCCTGGATAAAAGACTCC | GTCCTCCTGCTCCTGCTGT | [38] |

| MMP1 | AGTGACTGGGAAACCAGATGCTGA | CTCTTGGCAAATCTGGCCTGTAA | [39] |

| MMP3 | CTGGACTCCGACACTCTGGA | CAGGAAAGGTTCTGAAGTGACC | [39] |

| CISD2 | TCCCAGTCCCTGAAAGCATT | ACGAACTGCAAGGTAGCCAAGA | [40] |

| SIRT1 | AGCCTTGTCAGATAAGGAAGGA | ACAGCTTCACAGTCAACTTTGT | [41] |

| TERT | CACCTGCCGTCTTCACTTCC | GTGAACAATGGCGAATCTGG | [42] |

| GDF11 1 | CCACCACCGAGACCGTCATT | GAGGGCTGCCATCTGTCTGT | [43] |

| GDF11 2 | GCAAACTGCGGCTCAAGG | GCTAATGACGGTCTCGGTGG | [44] |

| FOXO1 | TCATGTCAACCTATGGCAG | CATGGTGCTTACCGTGTG | [41] |

| LMNB1 1 | AAGCAGCTGGAGTGGTTGTT | TTGGATGCTCTTGGGGTT | [45] |

| LMNB1 2 | GGGAAGTTTATTCGCTTGAAGA | ATCTCCCAGCCTCCCATT | [46] |

| JAK2 | TCTGGGGAGTATGTTGCAGAA | AGACATGGTTGGGTGGATACC | [47] |

| MICA | TAAAATCCGGCGTAGTCCTG | GCATGTCACGGTAATGTTGC | [48] |

| PD-L1 | TGGCATTTGCTGAACGCATTT | TGCAGCCAGGTCTAATTGTTTT | [49] |

| ULBP1 | CCTGGAGCCTTCTCATCATC | AGGCCTTGAACTTCACACCA | [48] |

| ULBP2 | CGCTACCAAGATCCTTCTGTG | GGGATGACGGTGATGTCATA | [48] |

| ULBP4 | GACCTCAGGATGCTCCTTTG | GTGCACCGTTCTGCTTCAC | [48] |

| MT1X | GCTCCTGTGCCTGTGCCG | AGCAAACGGGTCGGGTTGTAC | [34] |

| MT1E | GCCCGACCTCCGTCTATAA | AACAAGCAGTCAGGCAGTTG | [34] |

| MT2A | CGCCGCCGGTGACTCCTG | ACGGTCACGGTCAGGGTTGTAC | [34] |

| MT1G | TCCTGTGCCGCTGGTGTCTC | ACGGGTCACTCTATTTGTACTTGGG | [34] |

| IL-1β | GGACAGGATATGGAGCAACAAGTGG | TCATCTTTCAACACGCAGGACAGG | [50] |

| IL-6 | GACAGCCACTCACCTCTTCAGAAC | GCCTCTTTGCTGCTTTCACACATG | [50] |

| TNF-α | AAGGACACCATGAGCACTGAAAGC | AGGAAGGAGAAGAGGCTGAGGAAC | [50] |

| hCOQ10A | TTTCAAGGATGCTGGCTCTT | GGCCTCAGCTTGTCAAATTC | [51] |

| MSRA | TGGTTTTGCAGGAGGCTATAC | GTAGATGGCCGAGCGGTACT | [34] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).