1. Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibition with monoclonal antibodies represents a cornerstone of treatment for RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The emergence of anti-EGFR therapies has significantly improved survival outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer patients, with high response rates in RAS wild-type cases [

1,

3]. The efficacy of anti-EGFR therapy is strongly dependent on the absence of RAS pathway alterations, making RAS testing mandatory before treatment initiation [

1,

4].

Current standard testing methods in many healthcare systems, including Japan, are limited to detecting common mutations. This limitation stems from both technological constraints and healthcare policy decisions, potentially leading to suboptimal treatment selection. The molecular landscape of colorectal cancer is complex, with RAS mutations representing the most frequent alterations, occurring in approximately 40% of cases [

5,

6]. Understanding the full spectrum of these mutations, including rare variants, has become increasingly important for optimal treatment selection.

The MEBGEN RASKET-B kit, commonly used in Japan, detects specific mutations in KRAS/NRAS exons 2, 3, and 4, while the OncoBEAM RAS CRC kit covers a similar spectrum of mutations. These methods have proven reliable for detecting common RAS variants but may miss rare alterations that could affect treatment efficacy.

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) has emerged as a powerful tool capable of identifying these rare variants. However, insurance coverage for CGP is typically limited to later-line settings in some circumstances [

7]. This restriction creates a potential gap in optimal treatment selection, particularly in the first-line setting where treatment decisions have the most significant impact on patient outcomes [

8]. The ability to detect rare RAS variants through CGP could prevent the administration of potentially ineffective treatments and guide more appropriate therapeutic choices.

Recent studies have suggested that rare RAS variants may have similar biological effects to common mutations in terms of constitutive pathway activation and resistance to anti-EGFR therapy [

9]. However, the real-world prevalence and clinical impact of these rare variants remain poorly characterized, particularly in Asian populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database and Patient Selection

The C-CAT database (ver. 20240419) represents Japan's largest cancer genomics repository [

10], containing comprehensive molecular profiling data from 71,779 cases across multiple cancer types. Within this database, colorectal cancer cases number 11,992, providing a robust dataset for analysis. The database incorporates results from five distinct genomic profiling platforms: the NCC Oncopanel System, FoundationOne CDx, FoundationOne Liquid CDx, Guardant360 CDx, and GeneMine

TM TOP Cancer Panel, each employed during specific time periods from June 2019 to April 2024.

These platforms offer varying capabilities in terms of gene coverage, specimen requirements, and additional molecular features analysis. The NCC Oncopanel System examines 114 genes and includes microsatellite instability testing in its newer versions, while FoundationOne CDx provides comprehensive coverage of 324 genes with integrated Microsatellite Instability (MSI) and Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) assessment. FoundationOne Liquid CDx offers blood-based testing with identical gene coverage to its tissue-based counterpart, particularly valuable for patients unable to undergo tissue biopsy. Guardant360 CDx, though more focused with 73 genes, specializes in rapid blood-based analysis, while the GeneMineTM TOP Cancer Panel offers the most extensive coverage with 723 genes.

2.2. Definition of Pathogenic RAS Variants

Our approach to RAS variant classification followed a comprehensive methodology integrating multiple layers of evidence. Variants were initially identified as those not detectable by current standard testing methods (RASKET-B or OncoBEAM) and subsequently evaluated for pathogenicity through the OncoKB database (

https://www.oncokb.org/). Following the instructions of the genetics expert, we classified variants as pathogenic when designated as Likely Oncogenic or higher in OncoKB, and additionally included

KRAS T20M based on previously published functional studies [

9]. In cases where multiple alterations were detected, we prioritized frameshift mutations over point mutations, and mutations over amplifications. To maintain analytical clarity, cases harboring concurrent common RAS mutations were excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Clinical Data Collection and Outcome Assessment

As previously described [

11], we conducted a retrospective cohort study collecting comprehensive clinical, pathological, and genomic data. In brief, we gathered demographic information, pathological characteristics including histological type and tumor content, and detailed clinical sample information. Treatment histories, responses, and lifestyle factors were documented alongside family history of malignancy. Genomic testing results underwent standardized review by Expert Panels comprising medical oncologists, pathologists, clinical geneticists, bioinformaticians, and treating physicians, in accordance with Japanese insurance requirements.

Genomic analysis included evaluation of gene calls, tumor mutational burden, microsatellite instability status, and specific genetic alterations. Variant pathogenicity was assessed using established databases (ClinVar, OncoKB, jMorp), with variants classified as 'Likely Oncogenic' or higher in OncoKB, or meeting C-CAT evidence level F or higher being considered pathogenic. Treatment responses were documented by physicians at each institution with reference to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), with outcomes categorized as complete response, partial response, stable disease, progressive disease, or not evaluated.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Exploratory statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2021 and Statcel 5 (OMS Publishing Inc., Saitama, Japan). This exploratory analysis focused on identifying potential associations between genetic alterations and treatment responses. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests. Response rate was defined as complete response and partial response, while disease control rate included complete response, partial response and stable disease. All statistical tests were two-sided, with findings considered exploratory in nature given the limited sample size of this rare tumor cohort. Missing data were excluded from the analysis without imputation, considering the retrospective nature of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population Characteristics

Among the 71,779 cases registered in the C-CAT database (

Table 1), colorectal cancer represented 11,992 cases (16.7%). In this cohort, 4,122 patients received anti-EGFR antibody treatment, with 54 patients (1.3%) identified as harboring rare RAS variants (

Table 2). These rare variants were detected using MEBGEN RASKET™-B Kit and OncoBEAM™ RAS CRC Kit, with the specific genes tested listed in

Table 3, as described in the Methods section. The median age of patients with rare RAS variants was 62 years (range: 32-79 years), with the majority falling into the 60-69 years age group (n=20), followed by 50-59 years (n=16), and 70-79 years (n=14). The gender distribution was equal (27 males and 27 females).

Genomic profiling was predominantly conducted using FoundationOne CDx (n=44), followed by NCC Oncopanel System (n=6), FoundationOne Liquid CDx (n=3), and Guardant360 CDx (n=1). Testing specimens were obtained from primary sites (n=37), metastatic sites (n=13), and blood samples (n=4) (

Table 4).

Regarding Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), most patients demonstrated favorable performance status, with 30 patients (55.6%) classified as PS 0, 22 patients (40.7%) as PS 1, and 2 patients (3.7%) as PS 2. The majority of patients (n=49, 90.7%) received anti-EGFR therapy in combination with cytotoxic agents. Among these patients, panitumumab (n=40) was more commonly used than cetuximab (n=14).

The distribution of metastatic sites showed a pattern typical of advanced colorectal cancer, with liver metastases being most frequent (n=36, 66.7%), followed by lung metastases (n=30, 55.6%), peritoneal dissemination (n=15, 27.8%), bone metastases (n=5, 9.3%), and other sites (n=20, 37.0%). Regarding lifestyle factors, 24 patients had a smoking history and 8 patients reported a history of excessive alcohol consumption. Family history of cancer was present in 38 patients.

3.2. Overview of Genomic Testing Results

We analyzed genetic alterations identified through cancer genome profiling tests in 54 colorectal cancer cases. The TMB ranged from 0 to 246 mutations/Mb, with a mean TMB of 4 mutations/Mb.

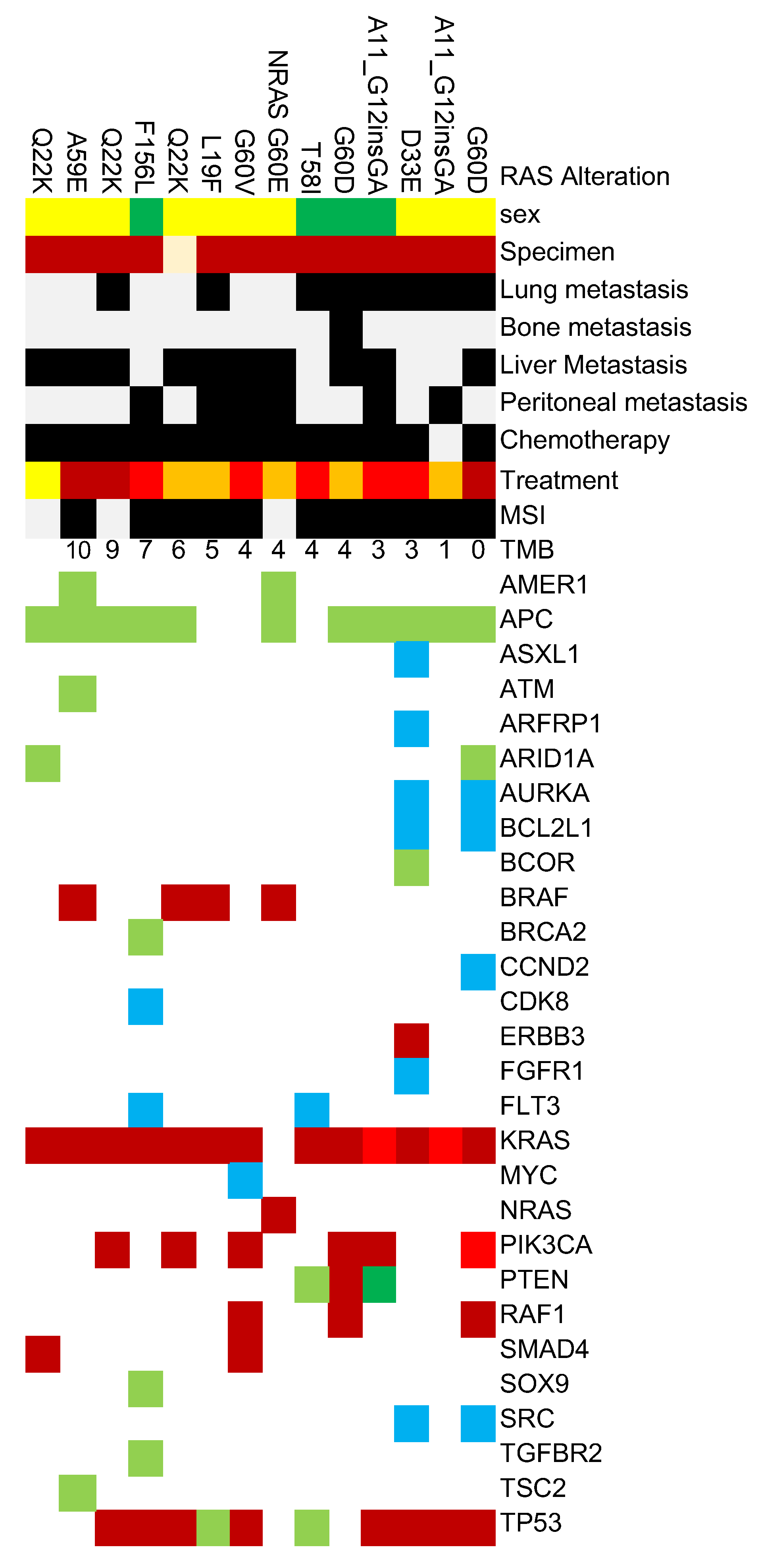

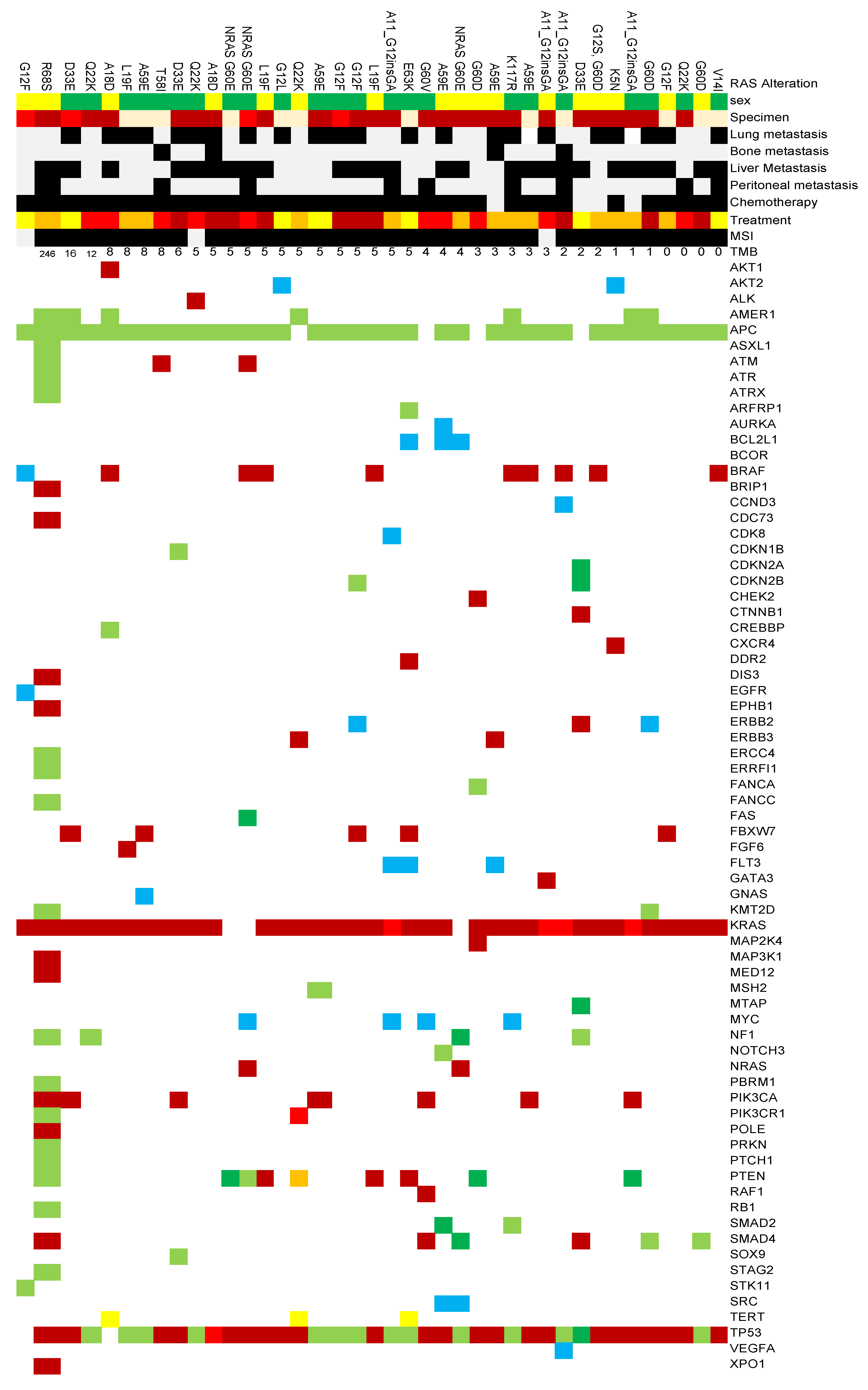

The most frequently observed alterations were in

TP53 and

APC genes, detected in 49 (90.7%) and 47 (87.0%) cases respectively, indicating their fundamental role in colorectal carcinogenesis. These were followed by non-V600E

BRAF mutations in 14 cases (25.9%),

PIK3CA alterations in 13 cases (24.1%), and

PTEN alterations in 12 cases (22.2%) (

Figure 1.).

Several other oncogenic alterations were detected at lower frequencies, including alterations in ERBB2 and MYC genes. These alterations may have implications for targeted therapy selection and prognosis.

Regarding microsatellite stability status, 48 cases (88.9%) were microsatellite stable (MSS), while 6 cases (11.1%) had unknown status.

Among rare RAS variants undetectable by routine clinical testing kits, KRAS Q22K was relatively frequently registered with 7 cases, followed by KRAS A59E and KRAS A11_G12insGA with 6 cases each, KRAS G60D with 5 cases, and KRAS G33E with 4 cases.

3.3. Treatment Outcomes Analysis

The analysis of treatment outcomes revealed striking differences between patients with rare RAS variants and other subgroups. The objective response rate in patients with rare RAS variants was showed a tendency to be lower at 28.3% compared to 44.6% in RAS wild-type patients and 38.1% in patients with common RAS mutations, with varying levels of statistical evidence (p=0.003 and p=0.090, respectively,

Table 5). This pattern was further reflected in the disease control rates, which showed marked disparities between rare RAS variant cases (60.9%), RAS wild-type cases (80.0%), and common mutation cases (74.8%).

4. Discussion

Our analysis of the C-CAT database provides several crucial insights into the clinical significance of rare RAS variants in colorectal cancer treatment. The identification of rare RAS variants in 1.3% of patients receiving anti-EGFR therapy represents a significant finding, as these patients’ received treatments that might have been avoided with comprehensive pre-treatment molecular testing. The substantially lower response rates observed in these patients (28.3% versus 44.6% in RAS wild-type cases) underscores the clinical relevance of identifying these variants before treatment initiation.

The molecular heterogeneity of colorectal cancer has been increasingly recognized, but the impact of rare genomic alterations on treatment outcomes has remained poorly characterized. Our findings build upon previous work by Loree et al. [

9], who identified the functional significance of rare RAS variants in preclinical models. The present study provides real-world validation of these laboratory findings, demonstrating that rare RAS variants indeed predict poor response to anti-EGFR therapy in clinical practice.

The disparity in response rates between patients with rare variants and those with RAS wild-type status raises important questions about current testing strategies. While the RASKET-B and OncoBEAM platforms have served as valuable tools for identifying common RAS mutations, our data suggest that their limited scope may result in missed opportunities for optimal treatment selection. The economic implications of this finding are substantial, considering the high cost of anti-EGFR antibodies [

12] and the potential for unnecessary toxicity exposure in patients unlikely to benefit from treatment.

T The timing of CGP testing emerges as a critical consideration from our analysis. Current healthcare policies in many circumstances, including Japan, restrict CGP coverage to later-line settings [

7]. This approach may be counterproductive, as our data suggest that earlier comprehensive testing might help optimize treatment selection and guide more appropriate therapeutic choices from the outset. The cost-effectiveness of implementing CGP before first-line therapy warrants careful evaluation, considering both the direct costs of testing and the potential savings from avoiding less optimal treatments.

Our findings also have implications for clinical trial design and biomarker development. The significant impact of rare RAS variants on treatment outcomes suggests that future trials of EGFR-targeted therapies should consider comprehensive molecular profiling in their eligibility criteria. Additionally, the development of more comprehensive companion diagnostic tests that can detect these rare variants may be necessary to optimize patient selection for anti-EGFR therapy.

Several limitations of our study warrant discussion. First, our analysis was based on amino acid changes without confirmation of specific nucleotide alterations, which could potentially mask some molecular complexity. Second, our inclusion of gastrointestinal tract cancers broadly, incorporating appendiceal and small intestinal cancers, may introduce some heterogeneity into the analysis. However, this approach reflects real-world practice patterns where these cancers are often treated similarly to colorectal cancer [

13]. Third, the timing of specimen collection was not considered in our analysis, and some liquid biopsy results may reflect acquired resistance mutations rather than primary variants. Finally, we did not analyze the impact of chemotherapy backbone or treatment line on outcomes, which could potentially influence response rates.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest evidence for the clinical relevance of rare RAS variants in colorectal cancer. The lower response rates observed in patients with these variants indicate that current standard testing methods may benefit from additional consideration for optimal patient selection for anti-EGFR therapy. The implementation of CGP before first-line therapy might contribute to treatment outcomes through more comprehensive patient selection and appropriate treatment allocation.

The implications of our findings extend beyond individual patient care to healthcare policy and resource allocation. The current paradigm of reserving CGP for later-line treatment may need reconsideration in light of these results. While the upfront costs of implementing CGP in the first-line setting would be substantial, the potential benefits of optimized treatment selection could offset these costs through improved outcomes and avoided ineffective therapies. A comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis would need to consider not only the direct costs of testing and treatment but also the indirect costs associated with managing adverse events and disease progression in patients receiving suboptimal therapy.

The evolution of molecular testing in colorectal cancer reflects a broader trend toward precision oncology, but our findings highlight persistent gaps in current approaches. The identification of rare RAS variants through CGP represents an opportunity to further refine patient selection for anti-EGFR therapy, potentially improving the therapeutic index of these agents. This refinement becomes particularly important as the treatment landscape for colorectal cancer continues to evolve, with new targeted therapies and immunotherapy approaches emerging [

14,

15].

From a biological perspective, our results support the hypothesis that rare RAS variants can have functional consequences similar to common mutations in terms of pathway activation and treatment resistance. This finding aligns with structural biology studies demonstrating that various RAS alterations can lead to similar conformational changes and downstream signaling effects [

9]. The lower response rates observed in our study might provide clinical validation of these mechanistic insights.

Future research directions suggested by our findings include the need for prospective validation of comprehensive molecular testing strategies, investigation of potential differences in the biology of rare versus common RAS variants, and evaluation of alternative treatment approaches for patients harboring these variants. Additionally, the development of more comprehensive, cost-effective testing platforms that can detect both common and rare variants could help bridge the current gap between standard testing and CGP.

5. Conclusions

This analysis of the C-CAT database demonstrates that rare RAS variants, detectable only through comprehensive genomic profiling, are associated with significantly poorer outcomes in patients receiving anti-EGFR therapy for colorectal cancer. The current practice of limiting CGP to later-line settings may result in suboptimal treatment selection for patients harboring these variants. Our findings support the implementation of more comprehensive molecular testing before first-line therapy to improve patient selection and treatment outcomes. While several limitations must be acknowledged, the clinical implications of our results warrant serious consideration of changes to current testing and treatment algorithms. Further research is needed to validate these findings prospectively and to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of earlier CGP implementation in the treatment paradigm for colorectal cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and Y.S.; methodology, S.S.; software, S.S. and Y.S.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S.; resources, S.S. and T.Y.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S, K.S., Y.Y., K.T., R.K., T.F. and T.Y..; visualization, S.S.; supervision, S.S.; project ad-ministration, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Yamagata University Center of Excellence (YU-COE (M)).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted following the "Ethical Guidelines for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects" with approvals from the Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (approval number: 2023-105, August 7, 2023) and the C-CAT Database Utilization Review Board (approval number: CDU2023-032N).

Informed Consent Statement

All study participants provided informed consent. Both written and oral consent were obtained from patients at genome designated hospitals.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated during this study is not publicly accessible due to confidentiality agreements as part of the ethics approval process.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere appreciation to all the patients. We thank Yuko Kagami for her careful and prompt administrative assistance, and Taku Murakami for his expert guidance and advice on genomic analysis. For this English manuscript preparation, we utilized AI-powered language enhancement tools to improve clarity and readability (DeepL, Grammarly, Google Translation, and Claude).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amado, R.G.; Wolf, M.; Peeters, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Siena, S.; Freeman, D.J.; Juan, T.; Sikorski, R.; Suggs, S.; Radinsky, R.; et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartzberg, L.S.; Rivera, F.; Karthaus, M.; Fasola, G.; Canon, J.L.; Hecht, J.R.; Yu, H.; Oliner, K.S.; Go, W.Y. PEAK: a randomized, multicenter phase II study of panitumumab plus modified fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) or bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014, 32, 2240–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, J.; Muro, K.; Shitara, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Shiozawa, M.; Ohori, H.; Takashima, A.; Yokota, M.; Makiyama, A.; Akazawa, N.; et al. Panitumumab vs Bevacizumab Added to Standard First-line Chemotherapy and Overall Survival Among Patients With RAS Wild-type, Left-Sided Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2023, 329, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, G.; Shen, L.; Hu, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, B.; Qian, X. FOLFOX plus anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody (mAb) is an effective first-line treatment for patients with RAS-wild left-sided metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e0097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osumi, H.; Shinozaki, E.; Suenaga, M.; Matsusaka, S.; Konishi, T.; Akiyoshi, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Nagayama, S.; Fukunaga, Y.; Ueno, M.; et al. RAS mutation is a prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer patients with metastasectomy. Int J Cancer 2016, 139, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylsma, L.C.; Gillezeau, C.; Garawin, T.A.; Kelsh, M.A.; Fryzek, J.P.; Sangaré, L.; Lowe, K.A. Prevalence of RAS and BRAF mutations in metastatic colorectal cancer patients by tumor sidedness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med 2020, 9, 1044–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebi, H.; Bando, H. Precision Oncology and the Universal Health Coverage System in Japan. JCO Precis Oncol 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubara, J.; Mukai, K.; Kondo, T.; Yoshioka, M.; Kage, H.; Oda, K.; Kudo, R.; Ikeda, S.; Ebi, H.; Muro, K.; et al. First-Line Genomic Profiling in Previously Untreated Advanced Solid Tumors for Identification of Targeted Therapy Opportunities. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2323336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loree, J.M.; Wang, Y.; Syed, M.A.; Sorokin, A.V.; Coker, O.; Xiu, J.; Weinberg, B.A.; Vanderwalde, A.M.; Tesfaye, A.; Raymond, V.M.; et al. Clinical and Functional Characterization of Atypical KRAS/NRAS Mutations in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 4587–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, T.; Kato, M.; Kohsaka, S.; Sudo, T.; Tamai, I.; Shiraishi, Y.; Okuma, Y.; Ogasawara, D.; Suzuki, T.; Yoshida, T.; et al. C-CAT: The National Datacenter for Cancer Genomic Medicine in Japan. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 2509–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Saito, Y. Genomic Analysis of Advanced Phyllodes Tumors Using Next-Generation Sequencing and Their Chemotherapy Response: A Retrospective Study Using the C-CAT Database. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.C.; Leal, F.; Sasse, A.D. Cost-effectiveness of cetuximab and panitumumab for chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Back, T.; Nijskens, I.; Schafrat, P.; Chalabi, M.; Kazemier, G.; Vermeulen, L.; Sommeijer, D. Evaluation of Systemic Treatments of Small Intestinal Adenocarcinomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e230631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.; Chee, C.E.; Wong, W.; Lam, R.C.T.; Tan, I.B.H.; Ma, B.B.Y. Current advances in targeted therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer - Clinical translation and future directions. Cancer Treat Rev 2024, 125, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bando, H.; Ohtsu, A.; Yoshino, T. Therapeutic landscape and future direction of metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 20, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).