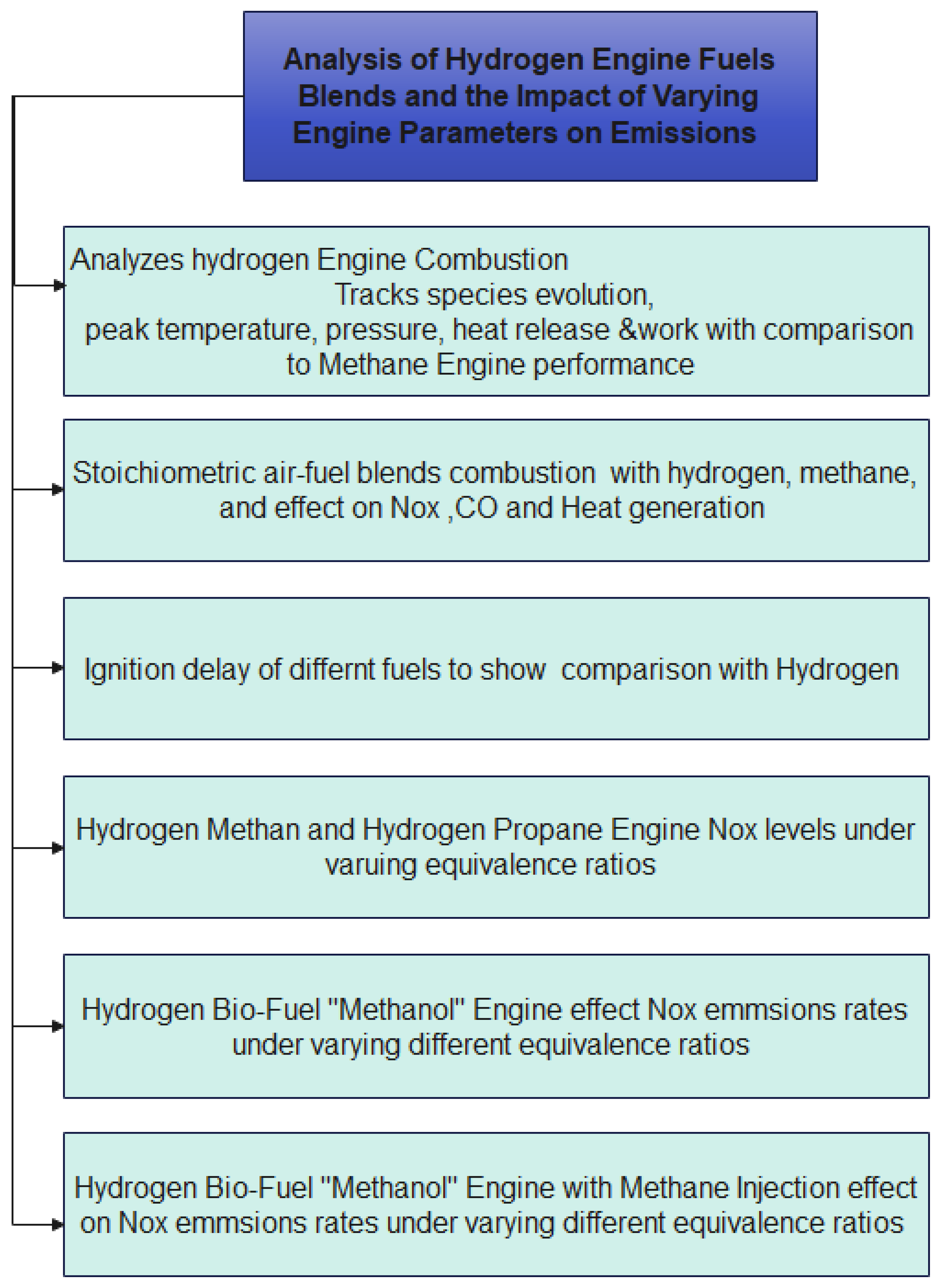

1. Introduction

Because of its unique combustion characteristics, hydrogen is a fuel with great potential for use in future energy systems (desert, 2001). It is also environmentally friendly. It is essential to comprehend these characteristics to enhance internal combustion engines and combustion management strategies. Hydrogen is suitable for advanced combustion strategies such as Homogeneous Charge Compression Ignition (HCCI) and Reactive Controlled Compression Ignition (RCCI), which aim to enhance engine performance and decrease harmful emissions (Efstathios, 2023). However, hydrogen-fueled engines face pre-combustion processes, knocking, and back-firing challenges. To address these issues, scientists design combustion chambers that improve air-fuel mixing, use swirling technologies to enhance fuel distribution and develop materials with solid resistance to hydrogen embrittlement. Developing hydrogen infrastructure and supply chains is crucial for the broader application of hydrogen-fueled engines.

2. Model and Methods

The central part of the model is a Python script that analyzes hydrogen combustion using the Cantera library, utilizing the "gri30" chemical mechanism. The model also calculates the same simulation for a methane fuel engine and compares the results. The combustion cycle consists of isentropic compression, volume combustion, and expansion stages, closely monitoring thermodynamic parameters and species evolution. The model determines combustion characteristics, including peak temperature, pressure, and heat release, and calculates work output and exhaust temperature. Its flexibility allows for extensive research in varying operating windows.

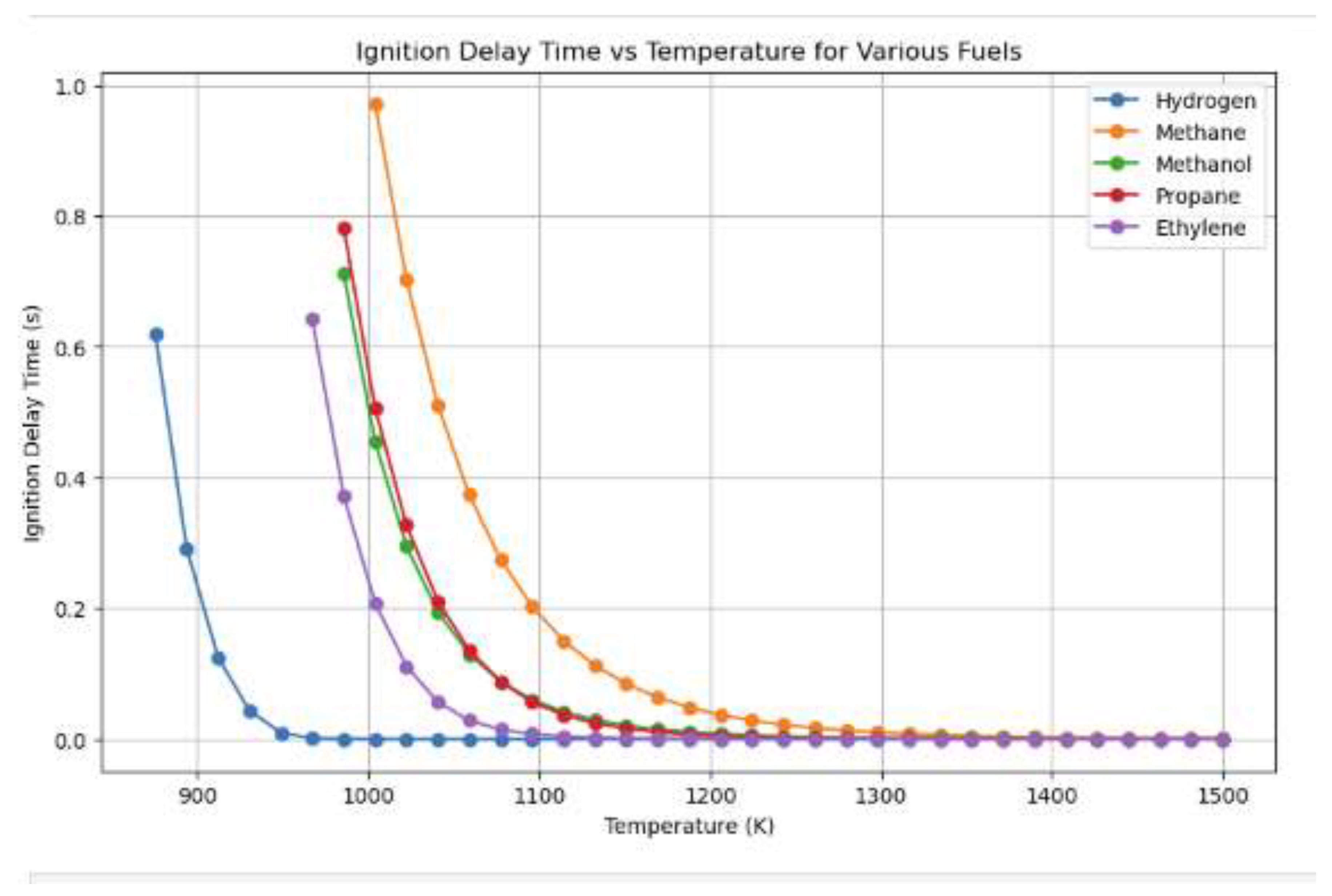

The first part of the model is a simulation tool that analyzes the Ignition Delay for various fuels, including hydrogen, methane, methanol, propane, and ethylene. The goal is to model hydrocarbon combustion and NOx formation under constant volume conditions, with the reactor starting with stoichiometric air-fuel blends at several initial temperatures and a pressure of 1 atm. The model records the time when a sudden temperature rise is observed, allowing for numerical accuracy and computational efficiency (Dimitriou, 2023).

The model's second section tracks the ignition delay throughout the combustion of various fuels. This is crucial for attaining combustion stability and is the primary aspect in numerical modeling, which gives each fuel the appropriate amount of time to carry out actual combustion and produce tangible results.

The Third part of the model investigates the burning characteristics of hydrogen-methane (H2-CH4) fuel blends. It assesses thermal and pollution metrics such as CO, heat release, and NO concentrations by changing the hydrogen percentage in the fuel mix at stoichiometric combustion conditions in a manner that resembles the process in Reactive Controlled Compression Ignition (RCCI). This study aims to investigate the trade-offs between NO and CO concentrations and heat release to draw a picture concerning the feasibility of hydrogen and methane in different percentages of methane in energy applications to reach the best clean mixture (Kiverin, 023).

The model's fourth section examines the impact of substituting hydrogen for various hydrocarbon fuels, altering the equivalency ratio, and monitoring the impact on NOx emissions. Propane and methane are the fuels that are examined. The model forecasts the highest NO concentration that will happen during the combustion stage and clearly connects the usage of hydrogen, methane, or propane with the removal of NOx during the combustion phases..

The model's fifth section examines how the equivalency ratio and hydrogen blend with a biofuel of methanol affect the amount of NOx emissions produced.

The final section presented the idea of adding methane to the hydrogen methanol blend in determined percentages to track the NOx emissions level by changing the equivalency ratio.

Figure 1.

An overview of the hydrogen engine models examined in this study.

Figure 1.

An overview of the hydrogen engine models examined in this study.

Equations of The Model (Q.T. Dam, 2024)

Final pressure after isentropic compression:

Temperature after isentropic expansion:

Ignition Delay Recording:

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of NOx Emissions in Hydrogen and Methane Combustion: The Impact of Equivalence Ratio and Fuel Characteristics

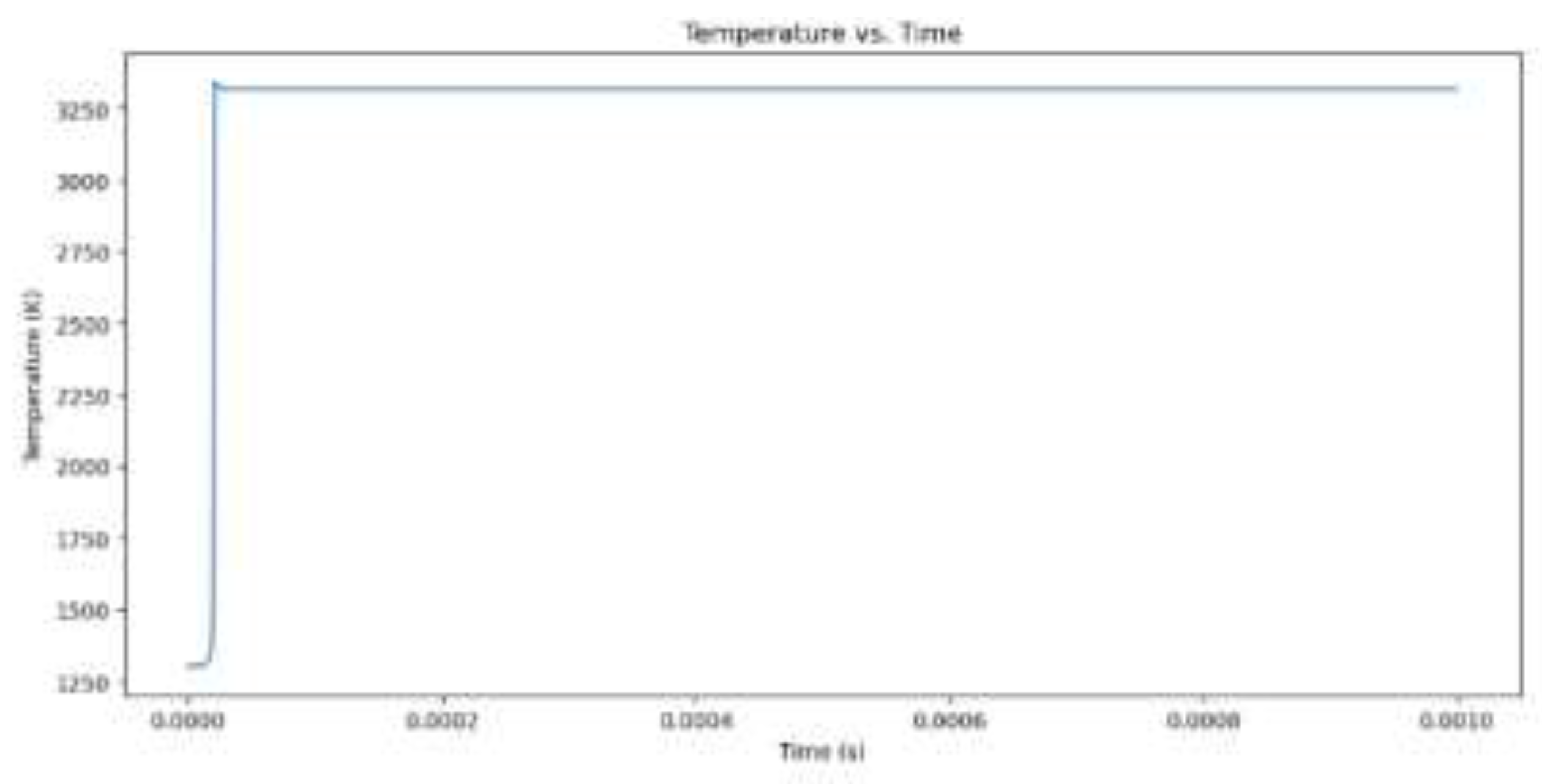

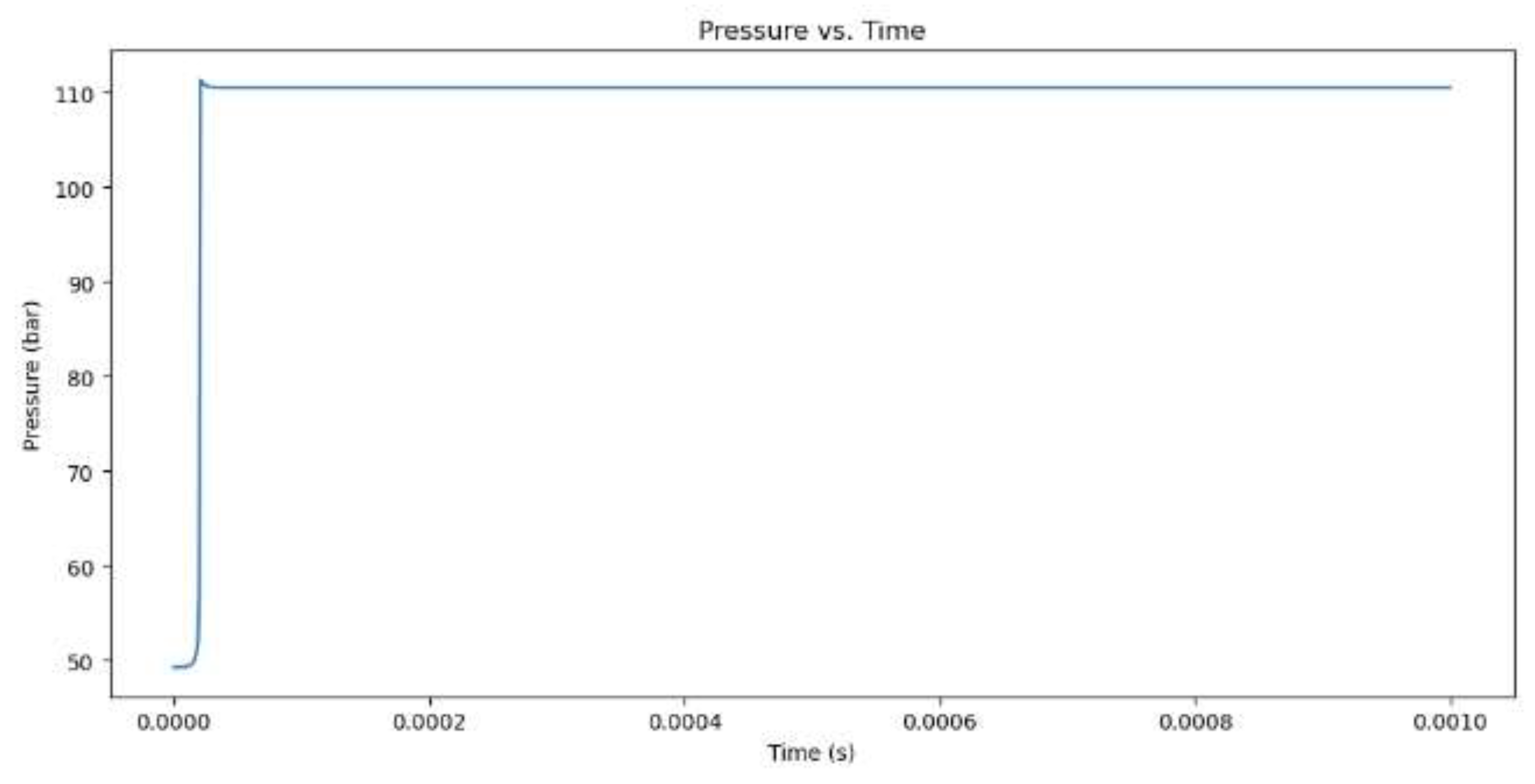

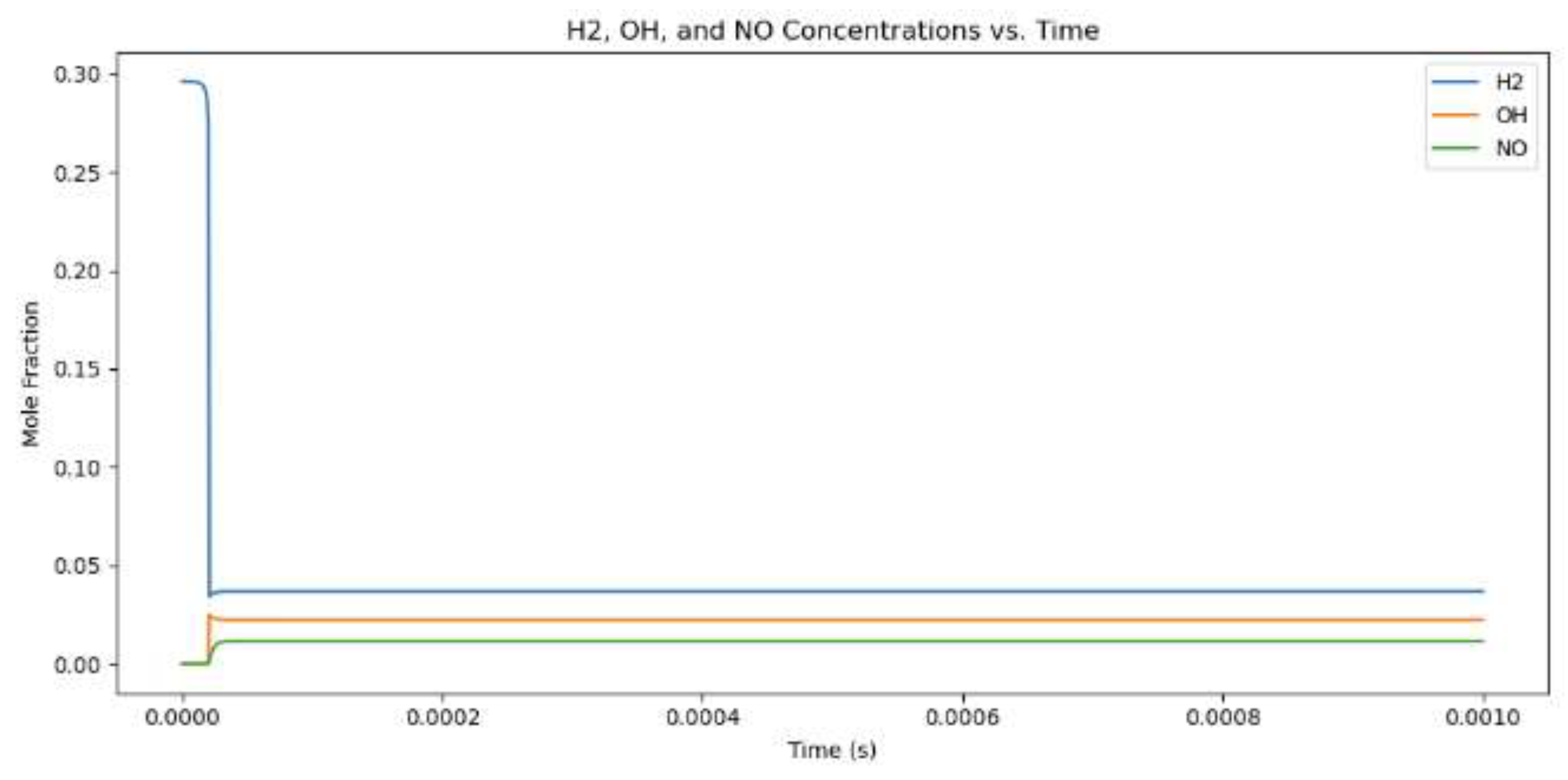

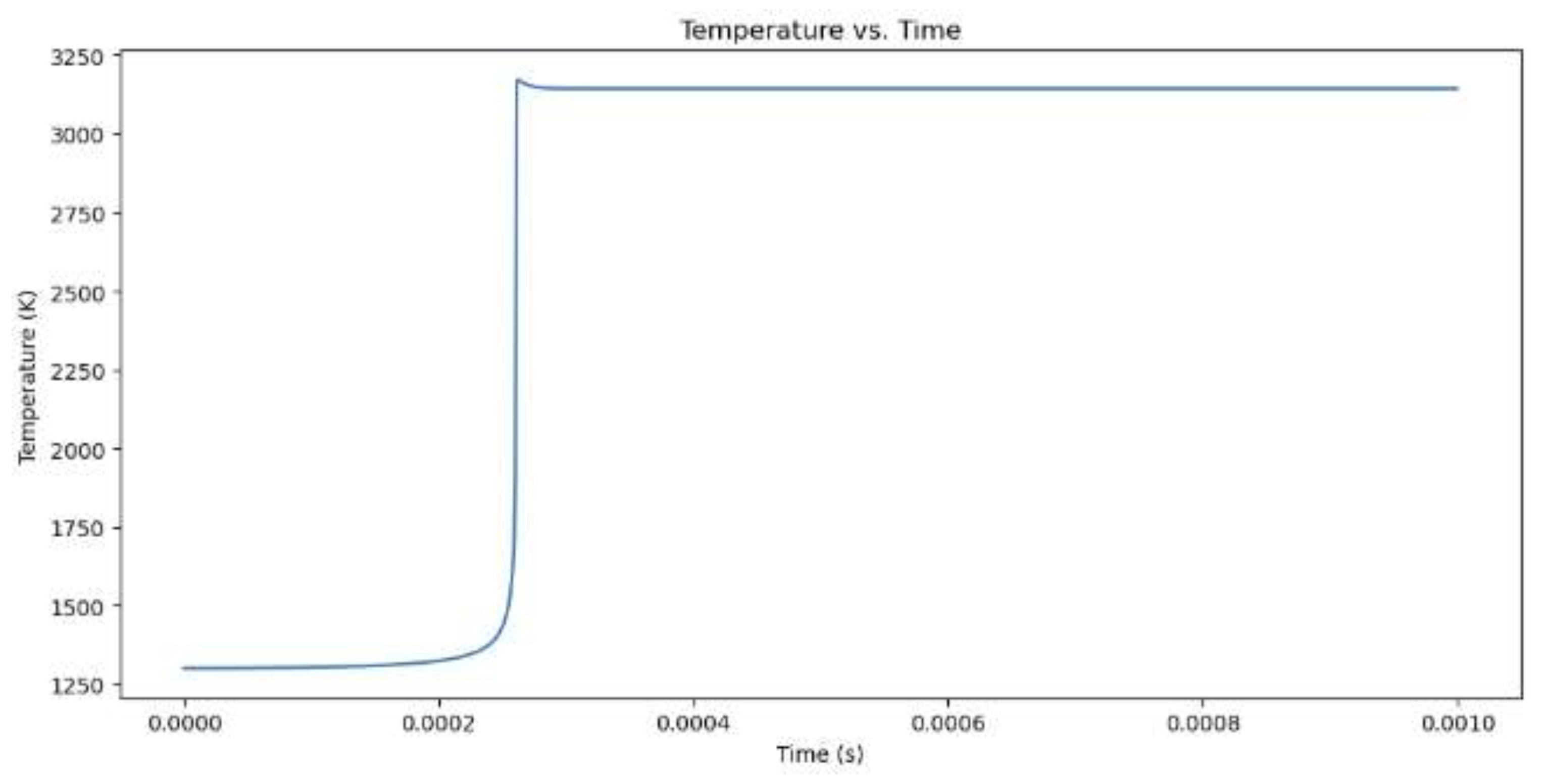

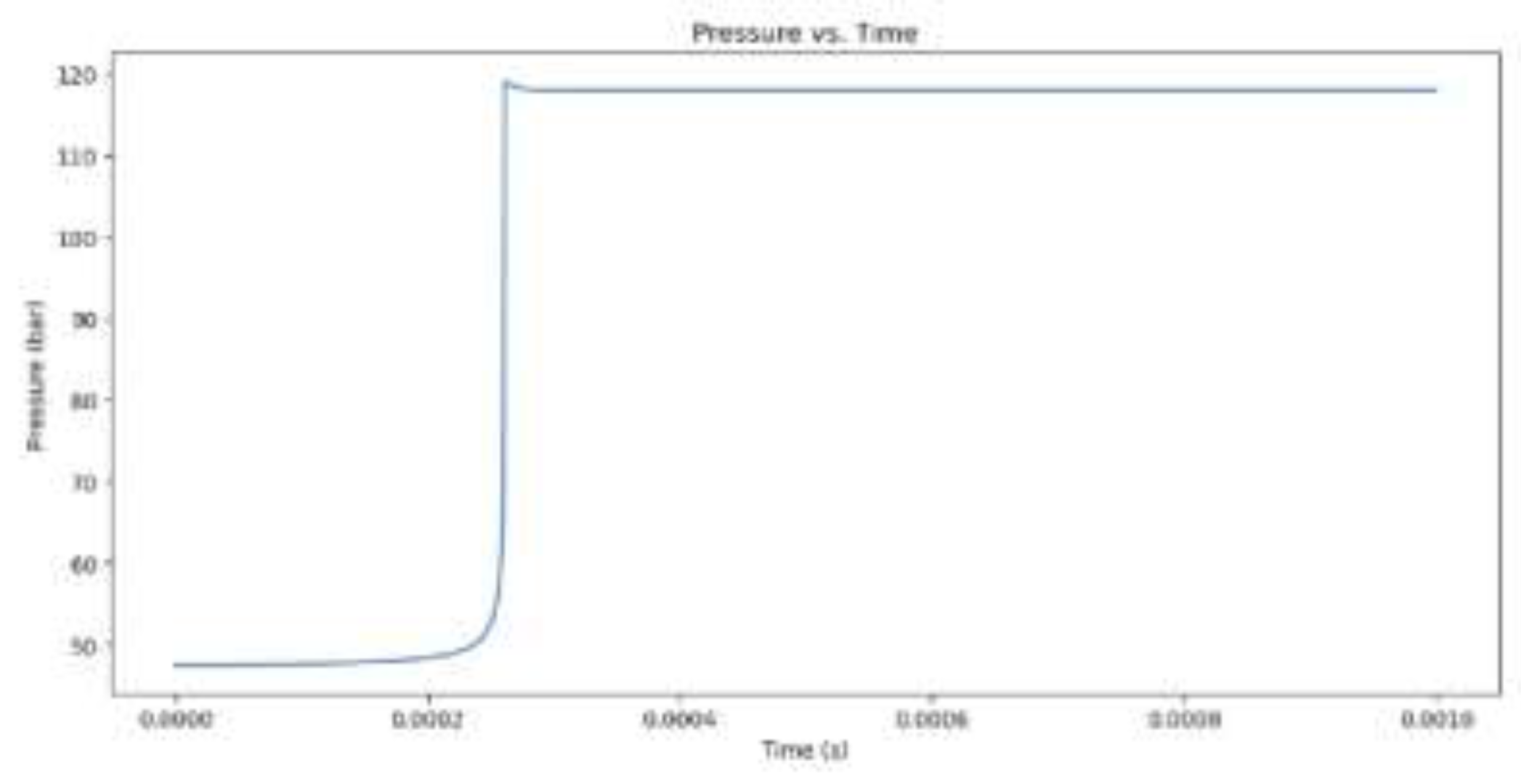

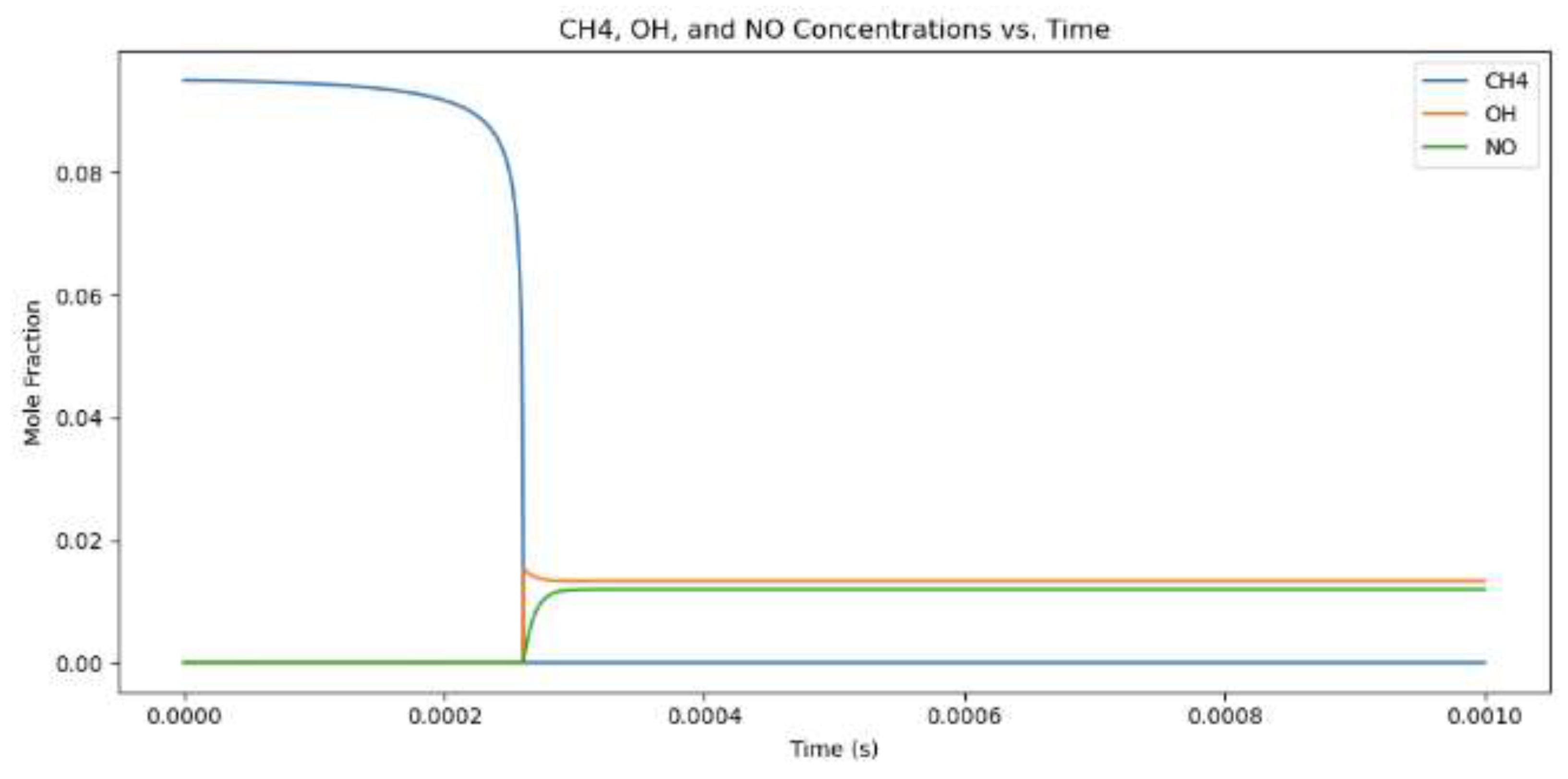

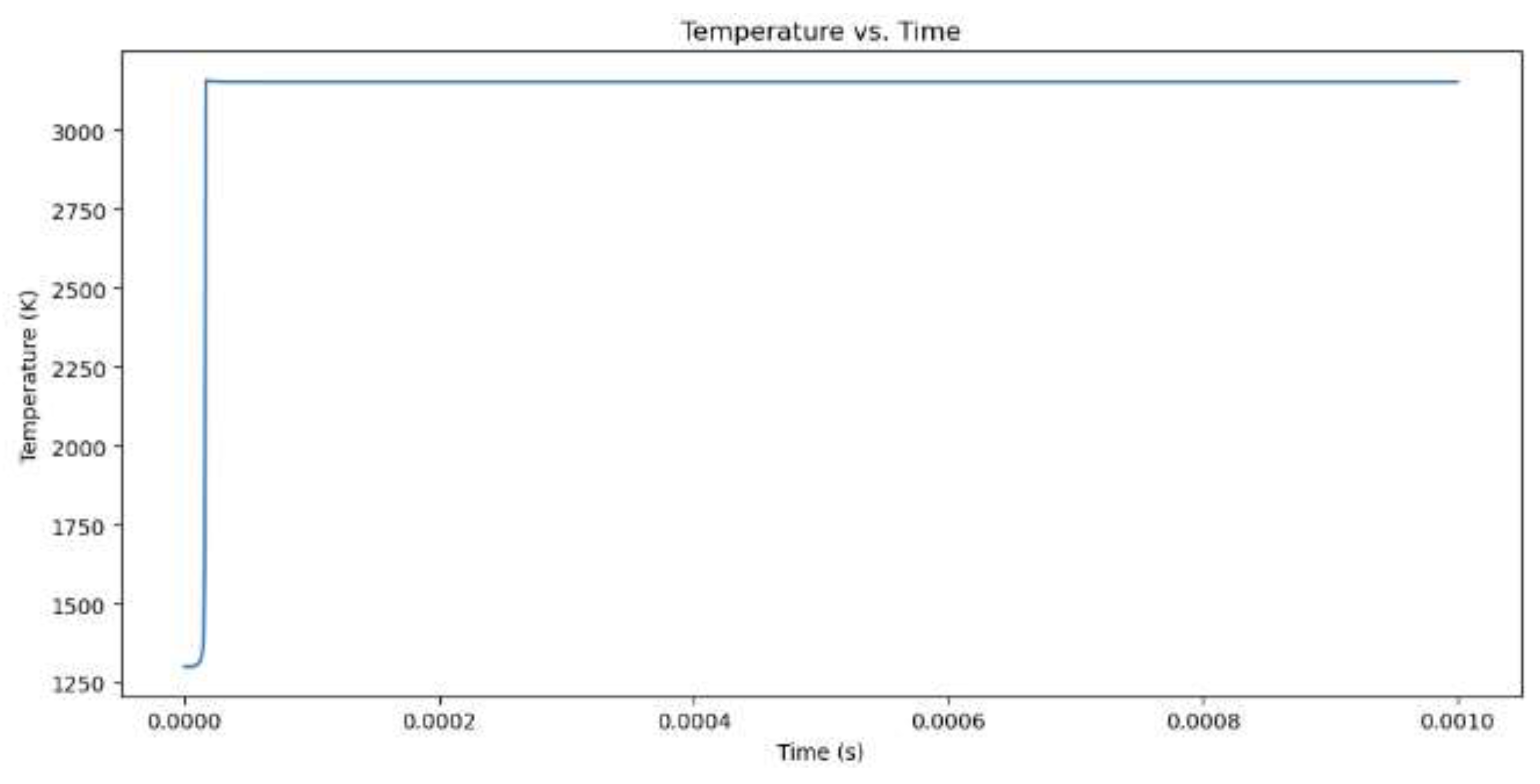

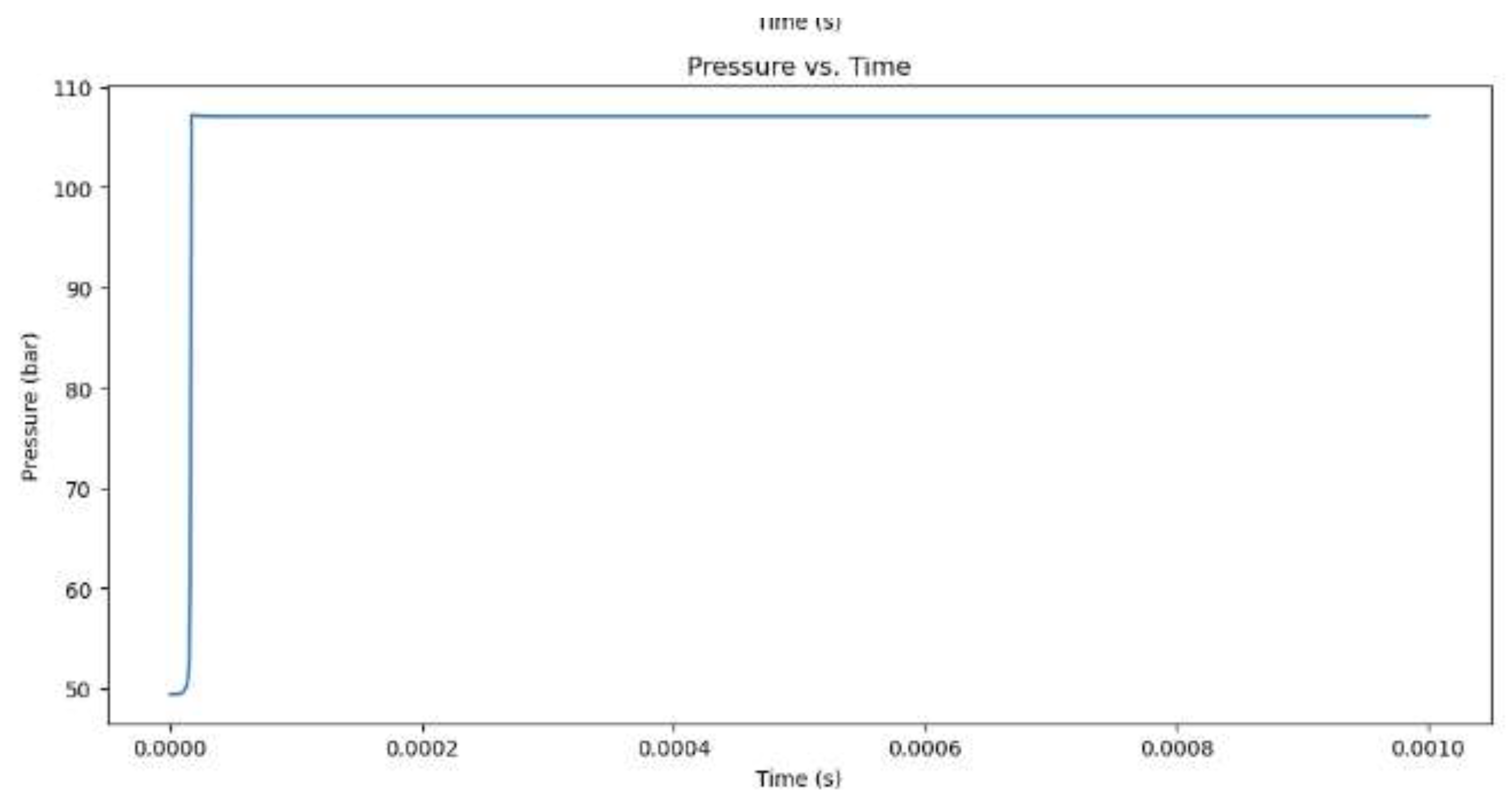

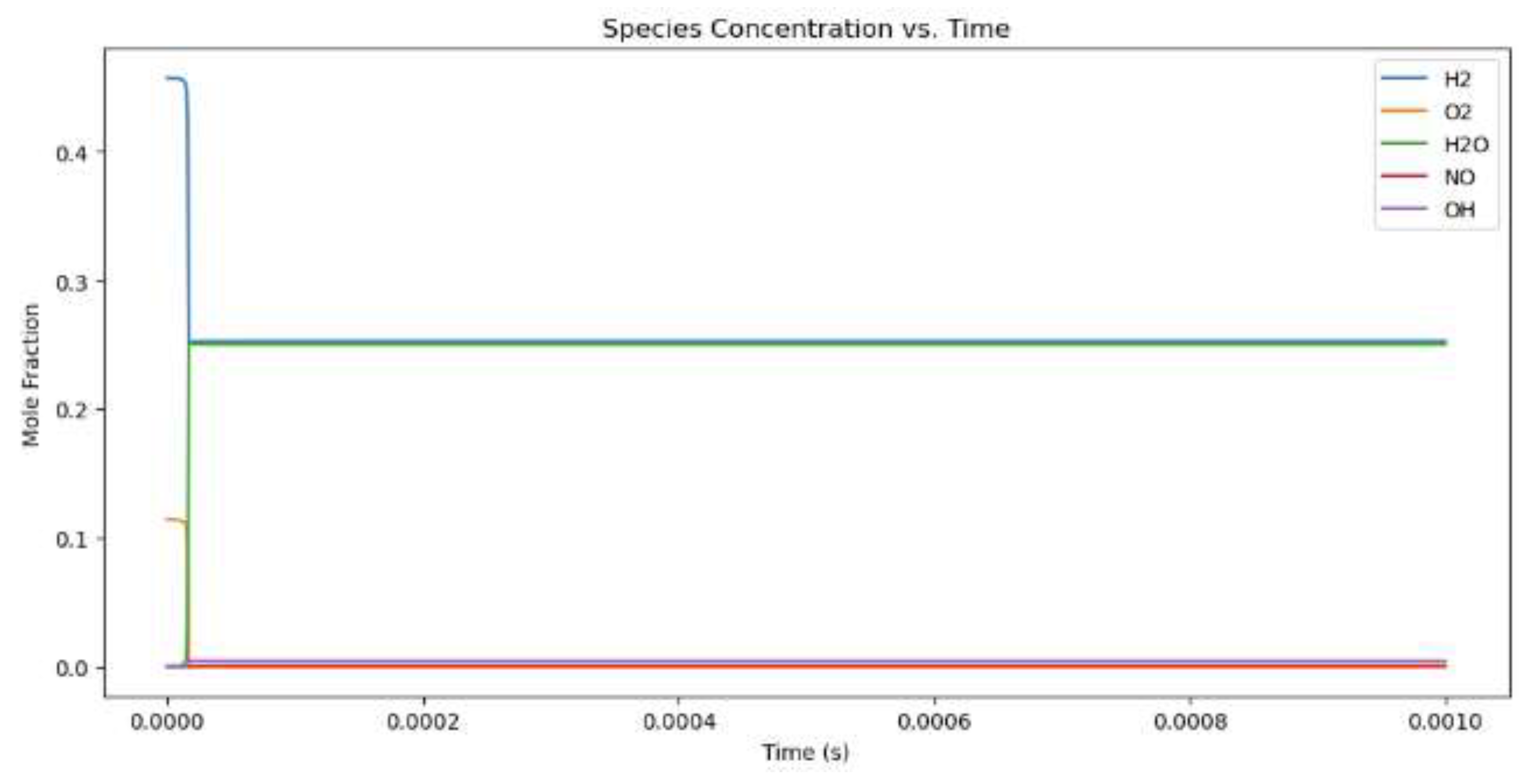

The model begins by outlining its initial values, which include the equivalence ratio, temperature, pressure, and the type of fuel, which is either CH4 or H2. Combustion of methane (CH4) with an equivalence ratio of 1 produces greater NOx emissions than hydrogen (H2) with the same equivalence ratio. Methane combustion has a theoretically calculated temperature of 3171.49 K at a maximum temperature and combustion pressure of 118.93 bar, while hydrogen combustion occurs at 3341.46 K at a slightly lower combustion pressure. This higher temperature is due to higher flame speed and energy produced by hydrogen. Methane combustion produces more NOx emissions than hydrogen, which is 11,479 ppm. This is due to the longer burn time of methane combustion and the presence of nitrogen in the fuel-air mixture. Hydrogen combustion occurs more quickly, but its short time limits NOx emissions.When comparing hydrogen combustion with an equivalence ratio of 1, the influence of a vibrant mixture (more fuel and less oxygen) on combustion and NOx formation is observed. At an equivalence ratio of 2, the maximum temperature reduces to 3156.66 K, and the combustion pressure decreases to 107.51 bar. The NOx concentration decreases significantly from 11,479 ppm at equivalence 1 to only 684 ppm at equivalence 2.

In conclusion, higher equivalence ratios are preferable for hydrogen combustion, as fewer NOx emissions are formed. Suppress NOx emissions.

Figure 2.

Temperature increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 2.

Temperature increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 3.

Pressure increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 3.

Pressure increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 4.

Mole fractions for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 4.

Mole fractions for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 5.

Temperature increase for Methane combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 5.

Temperature increase for Methane combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 6.

Pressure increase for Methane combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 6.

Pressure increase for Methane combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 7.

Mole Fraction for Methane combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 7.

Mole Fraction for Methane combustion when the equivalency value is 1.

Figure 8.

Temperature increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 2.

Figure 8.

Temperature increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 2.

Figure 9.

Pressure increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 2.

Figure 9.

Pressure increase for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 2.

Figure 10.

Mole Fractions for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 2.

Figure 10.

Mole Fractions for hydrogen combustion when the equivalency value is 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of Combustion Parameters for Hydrogen and Methane at Various Equivalence Ratios.

Table 1.

Comparison of Combustion Parameters for Hydrogen and Methane at Various Equivalence Ratios.

| Parameter |

H₂ Equivalence 1 |

H₂ Equivalence 0.8 |

H₂ Equivalence 0.5 |

H₂ Equivalence 2 |

CH₄ Equivalence 1 |

| Maximum Temperature (K) |

3,341 |

3,188 |

2,739 |

3,037 |

3,080 |

| Combustion Pressure (bar) |

111 |

107 |

95 |

121 |

136 |

| Combustion Energy (MJ/kg) |

2.75 |

2.45 |

1.82 |

2.98 |

2.2 |

| Compression Temperature (K) |

880 |

879 |

877 |

886 |

820 |

| Compression Pressure (bar) |

49 |

49 |

49 |

49 |

47 |

| Expansion Work (MJ/kg) |

2.23 |

2.03 |

1.63 |

2.58 |

1.85 |

| Net Work (MJ/kg) |

1.58 |

1.42 |

1.06 |

1.77 |

1.35 |

| Cycle Efficiency (%) |

49 |

49 |

47 |

54 |

55 |

| Exhaust Temperature (K) |

1,346 |

1,277 |

1,078 |

1,177 |

1,173 |

| NO Concentration (ppm) |

11,480 |

18,384 |

18,726 |

389 |

9,953 |

The equivalency ratio significantly influences NO concentration and temperature in hydrogen combustion. As the equivalency ratio for hydrogen declines from 1 to 0.5 (indicating a leaner mixture), the concentration of NO rises from 11,480 ppm to 18,726 ppm, attributed to increased oxygen availability and elevated combustion temperatures facilitating NO production. In contrast, a rich mixture (H₂ equivalency 2) significantly decreases NO concentration to 389 ppm, as insufficient oxygen inhibits NO synthesis. In contrast, methane combustion at an equivalency ratio of 1 yields a moderate NO concentration of 9,953 ppm, which is lower than that of lean hydrogen mixes but greater than that of rich hydrogen mixtures. The peak temperature in hydrogen combustion exhibits a comparable pattern. At an equivalent ratio of 1, the temperature reaches its numerical theoretical peak at 3,341 K. Still, leaner mixtures with an equivalence ratio of 0.5 provide lower temperatures of 2,739 K. Rich mixtures (equivalence 2) marginally reduce the peak temperature to 3,037 K because of incomplete combustion. The combustion of methane, reaching a peak temperature of 3,080 K, is marginally lower than that of stoichiometric hydrogen but exceeds that of rich hydrogen mixtures. Hydrogen typically attains elevated temperatures owing to its superior energy content and rapid burning rates, which is challenging when determining the engine material to support hydrogen operations. In comparing pressure rise, hydrogen combustion at an equivalency ratio of 1 yields a combustion pressure of 111 bar, which diminishes with leaner mixtures, resulting in 95 bar at an equivalence ratio of 0.5. Rich hydrogen combustion at 121 bar surpasses stoichiometric values owing to elevated fuel energy content. The burning of methane attains a markedly higher pressure (136 bar) compared to hydrogen due to its slower combustion rate and denser energy release. Ignition delay is critical in these comparisons. Hydrogen exhibits a significantly shorter igniting delay than methane owing to its reduced activation energy and accelerated flame propagation—the fast ignition of hydrogen combustion results in elevated peak temperatures and pressures. Methane, characterized by an extended ignition delay, demonstrates a more gradual combustion process, leading to reduced temperatures and pressures. Concerning network output, hydrogen at an equivalence ratio of 1 produces 1.58 MJ/kg, which diminishes with leaner mixtures, yielding 1.06 MJ/kg at an equivalence ratio of 0.5. Rich hydrogen combustion (1.77 MJ/kg) surpasses stoichiometric hydrogen due to enhanced fuel energy accessibility. Methane, at an equivalency ratio of 1, generates a network of 1.35 MJ/kg, which is inferior to hydrogen across all equivalence ratios due to its reduced specific energy. Transitioning from methane to hydrogen in engine operation entails substantial alterations. The elevated combustion energy and flame velocity of hydrogen necessitate altered injection systems to regulate ignition timing and prevent pre-ignition (Efstathios, 2023). The elevated peak temperatures and pressures require materials that endure significant thermal and mechanical strains. Moreover, hydrogen's tendency to produce reduced NOx emissions at rich equivalency ratios presents environmental advantages but at the cost of fuel economy; nonetheless, its lean mixtures may necessitate sophisticated approaches to minimize NOx generation. Hydrogen offers a cleaner and more efficient substitute for methane, yet it requires significant engine design and operation modifications to accommodate its distinct combustion properties.

3.2. Ignition Delay for Different Fuels Compared to Hydrogen

Figure 11.

Different fuels' ignition delays.

Figure 11.

Different fuels' ignition delays.

The graph shows the ignition delay time of various fuels, including hydrogen, methane, methanol, propane, and ethylene, based on temperature. Hydrogen has the shortest delay, indicating its higher reactivity and lower activation energy, resulting in faster flame propagation and improved combustion efficiency. Methane has longer delayed, especially at lower temperatures, indicating slower reaction rates and higher energy thresholds. Propane and ethylene show intermediate behaviors, with their delays decreasing more steeply with rising temperatures. Methanol, closer to propane and ethylene, still lags hydrogen in terms of reactivity. This suggests hydrogen's suitability for high-efficiency combustion systems.

3.3. The Hydrogen-Methane Combination Impacts Heat Release and Emissions

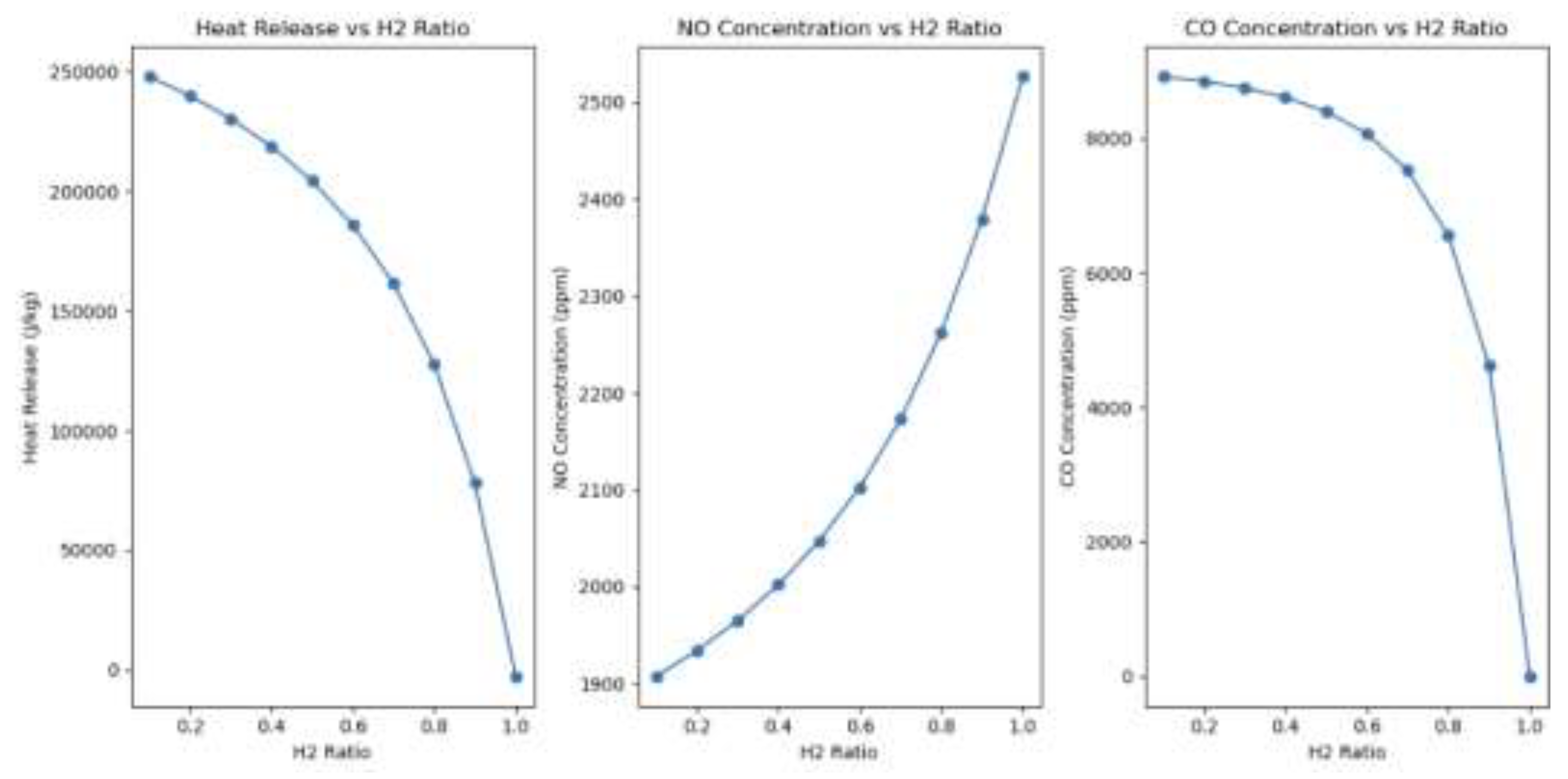

Figure 12.

Emissions and heat release Impact of the percentage of hydrogen in the H2/Ch4 fuel blend.

Figure 12.

Emissions and heat release Impact of the percentage of hydrogen in the H2/Ch4 fuel blend.

Heat Release: Methane (CH₄) exhibits a significantly higher volumetric energy density (36 MJ/m³) compared to hydrogen (H₂), which has only 10.8 MJ/m³. This indicates that, for an equivalent volume of fuel, the burning of Methane will produce roughly 3.3 times more energy. Hydrogen possesses a mass-based energy density of 120 MJ/kg, almost 2.4 times greater than that of methane, which is 50 MJ/kg. Volumetric systems, under stoichiometric conditions, combust less heat due to the low density of hydrogen despite its large mass energy. As the hydrogen ratio increases, it diminishes overall volumetric energy contribution, which explains the observed reduction in heat release in the reported simulations.

Nitrogen Oxide emissions: Hydrogen combustion produces a higher temperature than methane when comparing hydrogen and methane. Specifically, burning hydrogen at a 1:1 equivalent ratio achieves a temperature of 3,341 Kelvin, but the combustion of an equal amount of methane reaches a maximum of only 3,080 Kelvin. The elevated temperature produces significant quantities of nitrogen dioxide molecules during hydrogen combustion, exceeding those of methane combustion at stoichiometric ratios

Carbon dioxide emissions: The combustion of hydrogen produces no additional carbon-based emissions, reducing carbon monoxide concentrations. However, the combustion of methane produces emissions due to carbon oxidation at stoichiometric ratios. If a hydrogen ratio of one is maintained, carbon monoxide is absent, suggesting that the increase in carbon-based emissions may cease if hydrogen combustion systems are implemented.

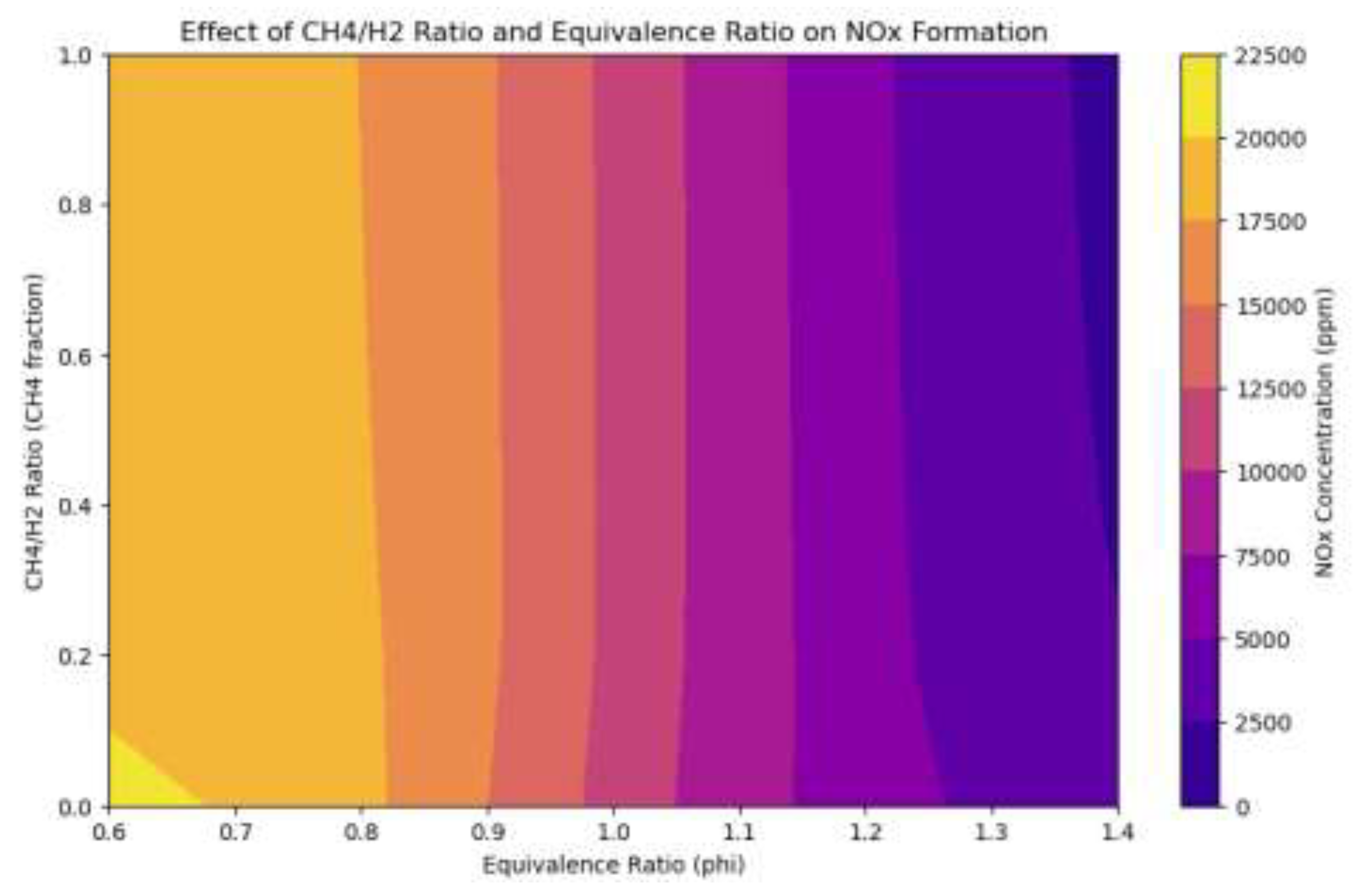

3.4. NOx Performance of Methane-Hydrogen Dual Fuel Engines

Figure 13.

Heat Map of Dual Fuel Engine Equivalence and Methan to Hydrogen Ratio Emissions Effect.

Figure 13.

Heat Map of Dual Fuel Engine Equivalence and Methan to Hydrogen Ratio Emissions Effect.

The heatmap comprehensively depicts the correlation between the CH₄/H₂ ratio and equivalency ratio (ϕ) regarding NOx production in a dual-fuel combustion system. NOx concentrations peak at approximately 22,500 ppm under CH₄-dominant ratios (CH₄/H₂ ≈ 1.0) and stoichiometric circumstances (ϕ ≈ 1.0). This is due to the combustion properties of methane, which generate elevated peak flame temperatures under these conditions, promoting NOx generation. As the H₂ ratio increases (resulting in a lower CH₄/H₂ ratio), NOx concentrations markedly diminish, especially in fuel-rich mixes (ϕ > 1.2). This reduction transpires as affluent mixes restrict oxygen availability, inhibiting the high-temperature reactions essential for thermal NOx generation, notwithstanding increased flame temperatures. Conversely, lean mixes (ϕ < 0.9) demonstrate diminished NOx concentrations at all CH₄/H₂ ratios owing to lower flame temperatures. Excess air in lean mixes serves as a thermal ballast, absorbing heat during combustion and diluting the reaction zone, hence lowering peak temperatures. Moreover, reduced fuel availability diminishes the total heat release, while slower reaction rates further constrain the energy output per unit of time, leading to substantial suppression of the Zeldovich mechanism. The heatmap identifies a significant NOx hotspot for stoichiometric methane-rich blends, underscoring the necessity of meticulously balancing the equivalency ratio and fuel content to optimize emissions. Increasing the hydrogen ratio can significantly diminish NOx emissions, particularly in fuel-rich settings with low oxygen. This illustrates hydrogen's capability to function as a more environmentally friendly substitute for methane in dual-fuel engine applications, yielding reduced emissions while preserving performance. The analysis highlights the necessity of regulating equivalency ratios and fuel mixtures to get optimal combustion properties and adhere to environmental standards.

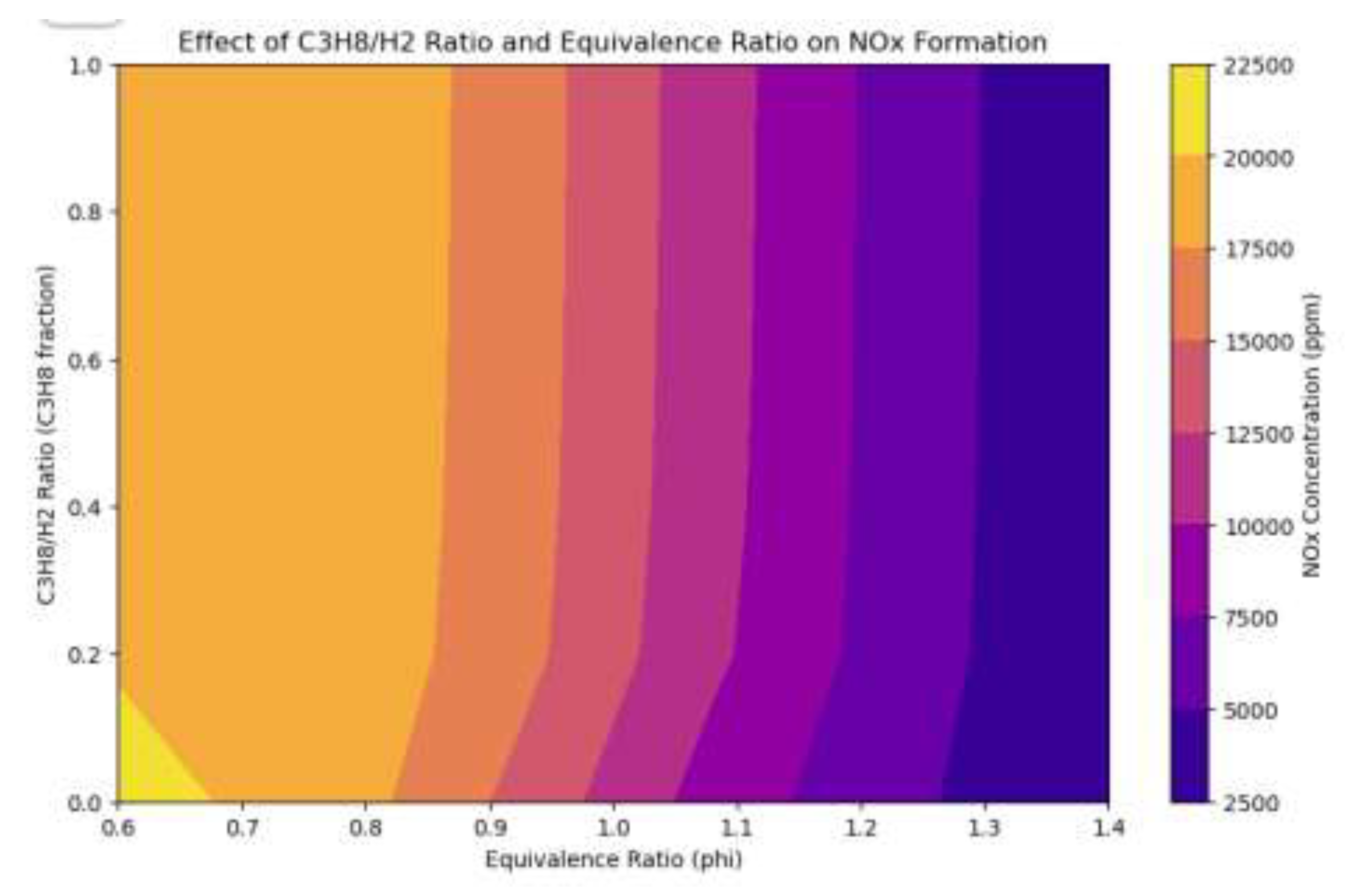

3.5. NOx Performance of Propane-Hydrogen Dual Fuel Engines

Figure 14.

Heat Map of Dual Fuel Engine Equivalence and Propane to Hydrogen Ratio Emissions Effect.

Figure 14.

Heat Map of Dual Fuel Engine Equivalence and Propane to Hydrogen Ratio Emissions Effect.

The heatmap shows the effect of propane-to-hydrogen ratio and equivalence ratio on NOx formation in dual-fuel combustion. The highest NOx concentrations are found in propane-dominant mixtures under stoichiometric conditions, driven by higher flame temperatures. As the hydrogen ratio increases, NOx concentrations decrease, especially in fuel-rich mixtures. Lean mixtures have lower NOx levels due to reduced flame temperatures. Hydrogen-rich blends achieve the lowest NOx emissions across all equivalence ratios, demonstrating hydrogen's ability to reduce NOx formation in high-temperature combustion. This highlights a NOx hotspot at stoichiometric propane-rich conditions, emphasizing the importance of hydrogen enrichment and non-stoichiometric equivalence ratios in propane-hydrogen dual-fuel systems.

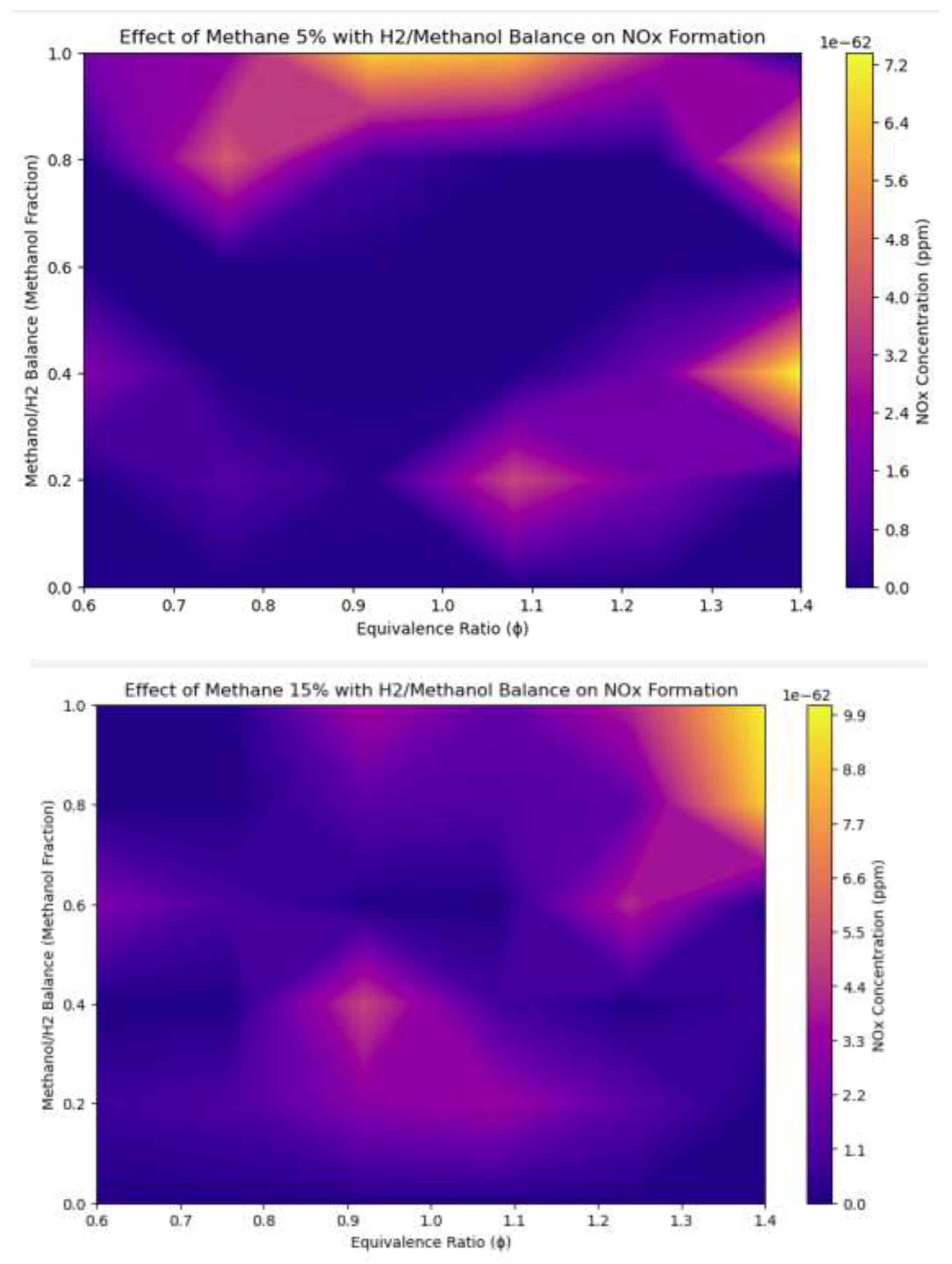

3.6. Methane, Hydrogen, and Methanol Blend vs Fuel Percentages and Equivalence Ratio

Figure 15.

Combustion characteristics of three fuel blends: methane, hydrogen, and methanol vs equivalency ratio and fuel percentages .

Figure 15.

Combustion characteristics of three fuel blends: methane, hydrogen, and methanol vs equivalency ratio and fuel percentages .

The augmentation of the methane fraction from 5% to 15% results in a significant elevation of NOx concentrations throughout the fuel-to-air ratio and methanol fraction ranges. This signifies that methane combustion markedly increases NOx production owing to its elevated flame temperature relative to methanol. Increased temperatures amplify the thermal NOx process, resulting in heightened NOx production, particularly under conditions near the ideal fuel-to-air ratio. The Influence of the Fuel-to-Air Ratio: For both methane fractions, NOx concentrations reach their maximum at the optimal fuel-to-air ratio, where the equilibrium between fuel and oxygen generates the highest combustion temperatures. Under lean conditions (insufficient fuel), NOx formation diminishes due to lower temperatures, but in rich conditions (enough fuel), the lack of oxygen constrains NOx production despite elevated temperatures. The balance of methanol and hydrogen indicates that increased methanol percentages result in a reduction in NOx emissions, especially under lean conditions. The reduced flame temperature of methanol, in contrast to methane and hydrogen, inhibits the thermal NOx process. Conversely, augmenting the hydrogen proportion (by diminishing methanol) results in elevated NOx emissions owing to hydrogen's remarkably high flame temperature, which accelerates thermal NOx generation more vigorously than methane. The results underscore the specific contributions of methane, methanol, and hydrogen to NOx emissions. Methane increases NOx emissions owing to its elevated flame temperature, whereas methanol reduces NOx generation through its cooling impact inside the mixture. The elevated flame temperature of hydrogen exacerbates NOx production as its proportion rises. The results underscore the necessity of adjusting fuel composition and combustion parameters to reduce NOx emissions, providing critical insights for the development of cleaner and more efficient fuel blends in advanced energy systems.

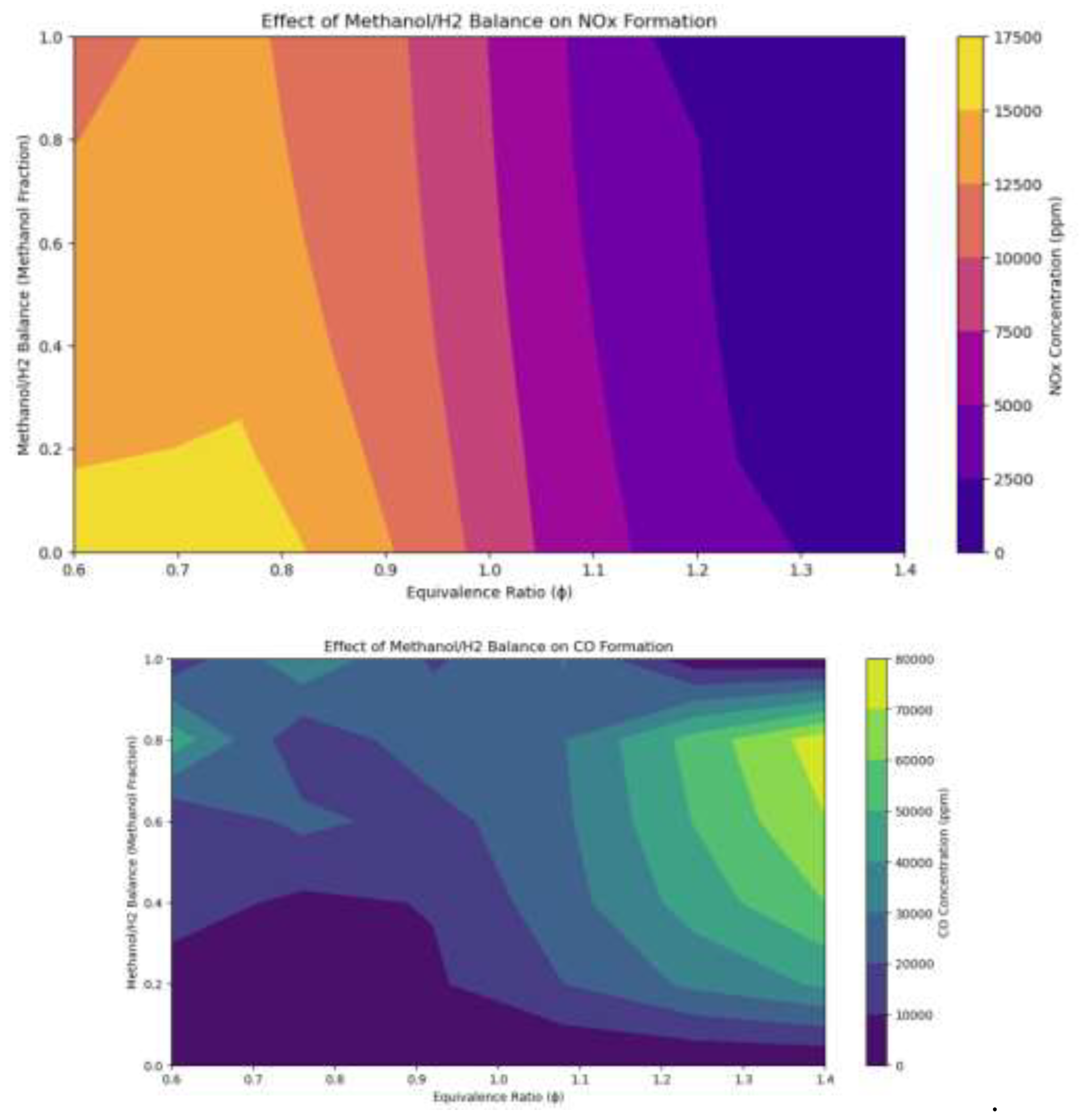

3.7. Emission levels of Hydrogen And Methanol Mixes.

Figure 16.

The impact of the equivalency ratio interactions between methanol and hydrogen mixtures on emissions levels.

Figure 16.

The impact of the equivalency ratio interactions between methanol and hydrogen mixtures on emissions levels.

The study examines the impact of methanol/hydrogen fuel content and combustion equivalence ratio on the generation of NOx and CO. It highlights the interaction between oxygen availability (from methanol and air) and temperature effects, which dictate emission trajectories. NOx production is maximized in areas where the equivalency ratio approaches stoichiometric levels, and the methanol percentage exceeds 0.6. This is due to methanol's molecular structure containing oxygen, which improves combustion efficiency and increases flame temperature. Reduced NOx emissions are observed in lean conditions (φ < 0.8), where surplus air reduces combustion temperature, inhibiting thermal NOx generation. Abundant conditions (φ > 1.2) show that restricted air supply and surplus fuel diminish flame temperature, inhibiting NOx generation due to inadequate nitrogen oxidation. As the methanol fraction diminishes and the hydrogen fraction escalates, NOx emissions decline due to hydrogen combustion typically generating lower flame temperatures than methanol-dominant combustion.CO formation is maximized at rich combustion conditions (φ > 1.2) and elevated methanol fractions (>0.6). In these conditions, they restricted oxygen supply from air, resulting in incomplete combustion, leaving a substantial amount of carbon as CO. The elevated carbon content of methanol intensifies this impact relative to hydrogen-rich fuels. The study also highlights the influence of temperature on NOx production, with elevated temperatures facilitated by near-stoichiometric conditions and substantial methanol concentrations enhancing NOx production. Oxygen availability affects CO production, with inadequate oxygen leading to incomplete combustion and elevated CO emissions. Increased methanol fraction often results in elevated NOx emissions and heightened CO emissions under rich conditions. The study provides valuable insights into emission control tactics for blended methanol-hydrogen fuels.

4. Validation and Literature Review

(Jingyun Sun, 2023 )The study on hydrogen-methanol blends with varying methane percentages (5% and 20%) aligns with Sun et al.'s 2023 study on pollutant formation mechanisms in hydrogen/ammonia/methanol ternary carbon-neutral fuel blend combustion. Both studies highlight the dual role of hydrogen and methanol in influencing NOx emissions and combustion dynamics. Higher hydrogen fractions lead to elevated NOx emissions due to increased flame temperatures, while methanol effectively mitigates NOx emissions through lower combustion temperature and heat-absorbing characteristics. Both studies also highlight that NOx emissions peak near stoichiometric or slightly rich equivalence ratios due to maximum flame temperatures. Methanol's contribution to reducing NOx emissions in ternary and binary blends underscores its critical role in enabling low-emission combustion strategies. The inclusion of methane in the study further refines the understanding of multi-fuel blends, demonstrating the complementary effects of hydrogen's high reactivity and methanol's emission-reducing properties.

(Dimitriou, 2018) A study on a multi-cylinder compression ignition engine tested under different hydrogen-diesel energy share ratios found that it can reduce harmful emissions and BTE by up to 90% at low load conditions. However, the maximum H2 energy share ratio drops to 85% at medium loads, leading to pre-ignition and unbalanced operation. At medium loads, NOx emissions increase by up to four times compared to conventional engines due to high in-cylinder temperatures. Exhaust gas recirculation reduces NOx emissions by up to 75%, but high EGR rates can deteriorate soot oxidation. Improved fuel atomization shifts the combustion phase closer to the TDC, reducing NOx emissions and soot formation. Alternative technologies like water injection and low-temperature combustion techniques are necessary to reduce NOx, soot, and carbon emissions simultaneously. The study reveals high flame temperatures and ample oxygen availability primarily drive high NOx emissions in part-load operations. This is consistent with trends observed in hydrogen and propane blends under stoichiometric conditions. However, transitioning to rich hydrogen mixtures (ϕ > 1.2) effectively reduces NOx emissions by limiting oxygen availability, offering a potential solution to mitigate NOx emissions in part-load operations. This highlights the importance of stoichiometric or near-lean equivalence ratios in optimizing efficiency.

(Li, 2023) The study confirms the strong correlation between flame temperature and NOx emissions, highlighting the role of high temperatures in thermal NOx formation. It also demonstrates that adjusting hydrogen equivalence ratios effectively controls NOx emissions, emphasizing the importance of equivalence ratio management.

(Q.T. Dam, 2024)This paper presents a dynamic model for an internal combustion engine powered by hydrogen, focusing on engine efficiency, torque, and emissions reduction. The model shows high efficiency in hydrogen combustion, but high combustion temperatures necessitate effective cooling systems. Simulations show torque output improvements and optimized fuel consumption, but the fuel's low density necessitates careful fuel injection control.

(Verhelst, 2023) (Wallnerb, 2009) The findings of this study regarding hydrogen-methane mixes corroborate and enhance our results by illustrating the trade-offs among NOx emissions, energy density, and engine efficiency. Our findings demonstrate that hydrogen-rich blends produce more significant NOx emissions owing to increased flame temperatures, aligning with this study's observation that higher methane concentrations diminish NOx emissions by tempering flame temperatures. The reduction in engine performance with elevated methane percentage corresponds with our observations that hydrogen's better mass-based energy density improves thermal efficiency, especially at low equivalency ratios. The vehicle-level measurements in the study indicate a 3% enhancement in brake thermal efficiency with hydrogen relative to gasoline, corroborating our results of increased net work and efficiency for hydrogen, especially under stoichiometric conditions. These comparisons highlight that although the amalgamation of methane with hydrogen enhances energy storage density and diminishes NOx emissions, it undermines efficiency, underscoring the necessity for meticulous tuning of blend ratios to reconcile emissions, efficiency, and storage capacity in real systems.

(S. Molina, 2023) This study supports our investigation into the feasibility of hydrogen as a fuel and how it interacts with dilution techniques for NOx reduction. Our results show comparable trade-offs when blending hydrogen with methanol and methane, highlighting the significance of regulating dilution rates to balance thermal efficiency and combustion stability. Our results are consistent with the documented shrinking of stable combustion ranges at increasing dilution (λ > 2), when fuel blending is necessary to stabilize the high flame temperature of hydrogen. The possibility for improving injection tactics is also highlighted in both studies. Our research shows how methanol and hydrogen blends improve efficiency in lean situations, which is consistent with this study's emphasis on direct injection for performance gains.

(S. K. V, 2014) Both experiments demonstrate that, as a result of improved combustion properties, adding hydrogen to fuel mixes increases brake thermal efficiency and lowers CO and HC emissions. Both also note that, particularly at larger hydrogen fractions, the high flame temperature of hydrogen causes a rise in NOx emissions. Additionally, both studies highlight how performance can be maintained and emission trade-offs minimized by blending hydrogen in controlled proportions, such as up to 20%.

(M. Huang, 2024.)The study investigates the impact of injector design and timing on hydrogen combustion in internal combustion engines. It reveals that larger injectors increase fuel delivery but increase pre-ignition risk. Early injection improves stability, while late injection reduces NOx emissions but increases knock risk. Optimized injector configurations improve engine efficiency and reduce NOx emissions.

(R.A. Bakar, May 2022)The study examines the efficacy of a direct injection diesel engine utilizing hydrogen in a dual-fuel configuration. Essential findings encompass the assessment of hydrogen flow rates, engine efficiency, NOx emissions, and combustion stability. Both studies forecast a 15-20% enhancement in efficiency, attributable to hydrogen's superior flame velocity and reduced ignition energy. Both emphasize the difficulty of regulating NOx emissions, with the experimental study revealing no substantial decrease in NOx despite augmented hydrogen flow, but CO, CO2, and particulate emissions were markedly diminished. Combustion stability is typical, especially in lean conditions, where pre-ignition and knock occur. Both underscore the potential of hydrogen to enhance engine performance yet illustrate the challenges in controlling emissions without adversely affecting other engine parameters.

(A. Keromnes, 2013) Our research examines the comparative examination of NOx emissions and combustion properties of hydrogen and methane across different equivalency ratios and operational situations. Hydrogen combustion exhibits markedly reduced NOx emissions in rich mixes (e.g., equivalence ratio 2.0) owing to restricted oxygen availability, whereas stoichiometric methane combustion produces elevated NOx levels due to prolonged burn duration and increased combustion pressures. Hydrogen's elevated flame temperature (e.g., 3341 K) and swift combustion rates lead to reduced ignition delays, accelerated combustion, and diminished NOx emissions under specific conditions relative to methane. Nonetheless, methane's superior volumetric energy density results in elevated peak combustion pressures, highlighting its unique combustion dynamics. The cited study corroborates our results by illustrating hydrogen's decreased NOx emissions in fuel-rich syngas mixtures, attributable to the inhibition of oxygen-dependent NOx pathways and its swift chemical kinetics. Both investigations confirm hydrogen's enhanced reactivity and combustion efficiency, especially at rich equivalency ratios, while emphasizing the influence of temperature and pressure on emissions. The cited study supports our finding that leaner mixes elevate NOx concentrations due to enhanced oxygen availability and elevated combustion temperatures. Both investigations confirm hydrogen's promise as a cleaner combustion fuel, highlighting its environmental advantages and unique properties relative to methane.

5. Conclusions

This work employed Cantera, an open-source computational tool, to examine ideal fuel mixes for improved energy efficiency and diminished emissions by simulating chemical kinetics, thermodynamics, and transport processes. The code enabled comprehensive study of dual and multi-fuel combustion, including comparison of ignition delay, equivalence ratio impacts, and pollutant emissions across different fuel combinations. The equivalency ratio greatly affects NOx emissions and combustion properties of hydrogen (H₂) and methane (CH₄). For H₂, lean mixtures (equivalence ratio = 0.5) enhanced NO concentrations owing to surplus oxygen and greater combustion temperatures, while rich mixtures (equivalence ratio = 2.0) diminished NOx to 389 ppm due to oxygen constraints. Conversely, methane burning under stoichiometric conditions (ϕ = 1.0) yielded a moderate concentration of NO, which was lower than that produced by lean H₂ combustion but higher than that from rich mixes. Methane demonstrated a reduced reaction rate and lower peak combustion temperatures relative to H₂, which, at an equivalence ratio of 1.0, attained 3,341 K, whereas methane peaked at 3,080 K. These facts correspond with hydrogen's superior reactivity and energy density relative to methane.

The equivalency ratio and fuel blend composition substantially influence NOx emissions in CH₄/H₂ dual-fuel combinations. NOx reached its zenith under methane-dominant conditions (CH₄/H₂ = 1.0) at stoichiometric equivalency. Nevertheless, as the H₂ ratio augmented in rich mixes (ϕ > 1.2), NOx concentrations diminished owing to oxygen limitations constraining thermal NOx production, despite greater flame temperatures. Lean mixes (ϕ < 0.9) led to diminished NOx concentrations across all CH₄/H₂ ratios, since extra air absorbed combustion heat, hence lowering flame temperatures.

In multi-fuel blends comprising CH₄, methanol, and hydrogen, methane generally represented 40-50% of the mixture. The incorporation of methanol enhanced energy density, whilst hydrogen diminished carbon emissions, so improving environmental performance. The burning of CH₄/methanol/H₂ mixtures at different equivalency ratios had substantial impacts on pollutant generation. Lean mixtures (ϕ < 0.9) exhibited diminished NOx emissions, whereas rich mixtures (ϕ > 1.2) restricted oxygen availability, hence further inhibiting NO production. CO emissions peaked under stoichiometric conditions but diminished as hydrogen ratios grew, attributable to hydrogen's carbon-free combustion properties. These findings highlight the significance of optimizing the equivalency ratio and fuel blending to attain a balance between energy efficiency and pollution reduction.

This study illustrates that hydrogen-rich mixtures have significant environmental benefits, particularly when combined with methane or propane. Engine improvements and thermal management are essential to address the increased combustion temperatures and pressures linked to hydrogen. Utilizing techniques such as Cantera, researchers may determine ideal equivalency ratios and blend compositions for sustainable, high-performance combustion systems.

In conclusion, our findings are corroborated by other investigations. Research conducted by Jingyun Sun (2023) highlights hydrogen's contribution to increased NOx emissions resulting from elevated flame temperatures, while methanol demonstrates efficacy in their reduction, a phenomenon reflected in our findings. Dimitriou (2018) and Li (2023) affirm the significant influence of equivalency ratios on NOx emissions, emphasizing hydrogen's capacity to diminish NOx in rich settings. Research conducted by Verhelst (2023)and Wallnerb (2009) corroborates the trade-offs identified between NOx emissions, energy density, and efficiency in hydrogen-methane mixtures, whereas S. Molina (2023) endorses the significance of dilution methods in achieving a balance between efficiency and combustion stability. The efficiency improvements and emission problems identified by S.K.V. (2014)and R.A. Bakar (2022) further validate our conclusions about NOx reduction measures. Ultimately, A. Keromnes (2013) corroborates our findings on hydrogen's increased reactivity and diminished NOx emissions in rich mixtures, although methane’s superior volumetric energy density underscores specific trade-offs. These studies collectively underscore the importance of hydrogen-methanol-methane mixes in attaining cleaner and more efficient combustion.

References

- A. Keromnes, W. K.-J. (2013). An experimental and detailed chemical kinetics model for hydrogen-methane mixture oxidation at elevated pressures. Combustion and Flame,, vol. 160, no. 6, pp. 995-1011.

- A. Teymoori, A. K. ( 2020). Validation of a Predictive Model of a Premixed Laminar Flame Speed for Hydrogen/Methane-Air Combustion for Internal Combustion Engines. Energy Reports, vol. 6, pp. 1200–1211.

- David G. Goodwin, H. K. (2023. ). Cantera: An object-oriented software toolkit for chemical kinetics, thermodynamics, and transport processes.Version 3.0.0. https://www.cantera.org,.

- desert, C. o. (2001). Hydrogen engine.

- Dhar, P. S. (2018). Compression ratio influence on combustion and emissions characteristic of hydrogen-diesel dual-fuel CI engine: numerical study. Fuel, vol. 222, pp. 852–858. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou. (2023). Hydrogen Compression Ignition Engines. Green Energy and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, P. K. (2018). Combustion and emission characteristics of a hydrogen-diesel dual-fuel engine. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy,, 43*(2018), 13605-13617. [CrossRef]

- Efstathios, A. T. (2023). Hydrogen for Future Thermal Engines. Springer.

- H. S. Homan, R. K. (1979 ). Hydrogen-fueled diesel engine without timed ignition. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 4, pp. 315–325. [CrossRef]

- Jingyun Sun, Q. L. (2023 ). Reactive Molecular Dynamics Study of Pollutant Formation Mechanism in Hydrogen/Ammonia/Methanol Ternary Carbon-Neutral Fuel Blend Combustion. MDPI Molecules Journal, 28(24), 8140. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Lee, Y. R. (2013). Feasibility of compression ignition for hydrogen-fueled engine with neat hydrogen-air pre-mixture by using high compression. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy,, vol. 38, pp. 255–264. [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, T. S. (2014). Experimental investigation of the combustion characteristics, emissions and performance of hydrogen port fuel injection in a diesel engine,. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 39, pp. 18480–18489. [CrossRef]

- Kiverin, Y. a. (023). Numerical Modeling of Hydrogen Combustion: Approaches and Benchmarks. Fire, vol. 6, no. 2, 2, pp. 239. [CrossRef]

- L. Gao, J. L. ( 2023). Hybrid emission and combustion modeling of hydrogen-fueled engines. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy,, vol. 48, no. 15, pp. 1245-1260. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. W. (2023). Numerical Investigation on NOx Emission of a Hydrogen-Fuelled Dual-Cylinder Free-Piston Engine.. Applied Sciences,, 13(3), 1410. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Rosati and P. G. Aleiferis. (2009). Hydrogen SI and HCCI combustion in a direct-injection optical engine. SAE International Journal of Engines, vol. 2, pp. 1710–1736. [CrossRef]

- M. Huang, Q. L. ( 2024.). Experimental investigations of the hydrogen injectors on the combustion characteristics and performance of a hydrogen internal combustion engine. Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 1940.

- M. Ikegami, K. M. (1975). A study on hydrogen-fuelled diesel combustion (1st report). Preprints of the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers,, vol. 750, pp. 239–242.

- M. Ikegami, K. M. (1980.). A study on hydrogen-fuelled diesel combustion. Bulletin of the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers,,vol. 23.

- M. T. Chaichan and D. S. M. Al-Zubaidi. (2015). A practical study of using hydrogen in dual-fuel compression ignition engine. International Publication Advanced Science Journal (IPASJ, vol. 2, pp. 1–10.

- Nagarajan, N. S. (2009). Experimental investigation on a DI dual fuel engine with hydrogen injection. International Journal of Energy Research,, vol. 33, pp. 295–308. [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, N. N. (2014). Modeling and simulation of hydrogen combustion in engines. International Journal of Hydrogen Energ, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 1122–1136. [CrossRef]

- P. Dimitriou, T. T. (2018). Combustion and emission characteristics of a hydrogen-diesel dual-fuel engine. ” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy,, vol. 43, pp. 13605–13617. [CrossRef]

- Q.T. Dam, F. H. (2024). Modeling and simulation of an internal combustion engine using hydrogen: A MATLAB implementation approach. Engineering Perspective,, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 108-118. [CrossRef]

- Qing-he Luo, J.-B. H.-g.-s.-z. (2019). Effect of equivalence ratios on the power, combustion stability and NOx controlling strategy for the turbocharged hydrogen engine at low engine speeds. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Vol 44 no 44 17095-17102. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Bakar, W. K. (May 2022). Experimental analysis on the performance, combustion/emission characteristics of a DI diesel engine using hydrogen in dual fuel mode. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy,.

- S. K. V, R. S. (2014). Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Hydrogen Addition on Combustion Performance and Emissions Characteristics of a Spark Ignition High-Speed Gasoline Engine. In Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. Innov. Autom. Mechatronics Eng. (ICIAME), pp. 1-8.

- S. Molina, R. N.-S.-G. (2023). Experimental activities on a hydrogen-fueled spark-ignition engine for light-duty applications,. Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 12055, pp. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Stoke, W. H. (1930.). Hydrogen-cum-oil gas as an auxiliary fuel for airship compression ignition engines. British Royal Aircraft Establishment,, Report No. E 3219.

- Subramanian, V. C. (2014). “Hydrogen energy share improvement along with NOx (oxides of nitrogen) emission reduction in a hydrogen dual-fuel compression ignition engine using water injection. Energy Conversion and Management,, vol. 83, pp. 249–259. [CrossRef]

- T. Tsujimura and Y. Suzuki. (2017). The utilization of hydrogen in hydrogen/diesel dual-fuel engine. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy,, vol. 42, pp. 24470–24486. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimura, M. D. (2019). “A fully renewable and efficient backup power system with a hydrogen-biodiesel-fueled IC engine. Energy Procedia,, vol. 157, pp. 1305–1319. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimura, Y. S. (2015). “The combustion improvements of hydrogen/diesel dual fuel engine. SAE Technical Paper. [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, Y. W. (2023). Comparative analysis and optimization of hydrogen combustion mechanism for laminar burning velocity calculation in combustion engine modelling,. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 112-125. [CrossRef]

- Wallnerb, S. V. (2009). Hydrogen-Fueled Internal Combustion Engines. Researchgate.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).