Submitted:

30 November 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

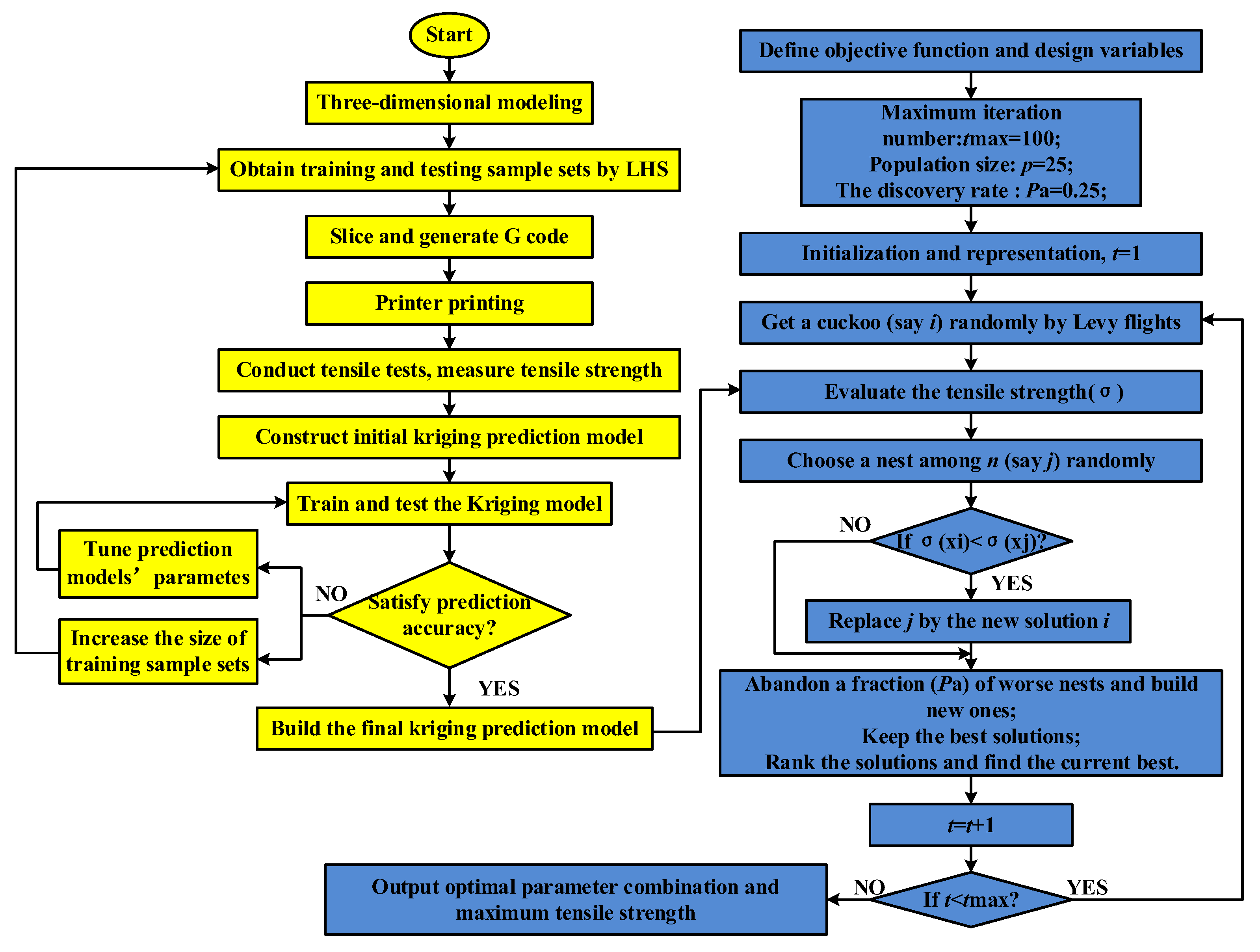

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem formulation

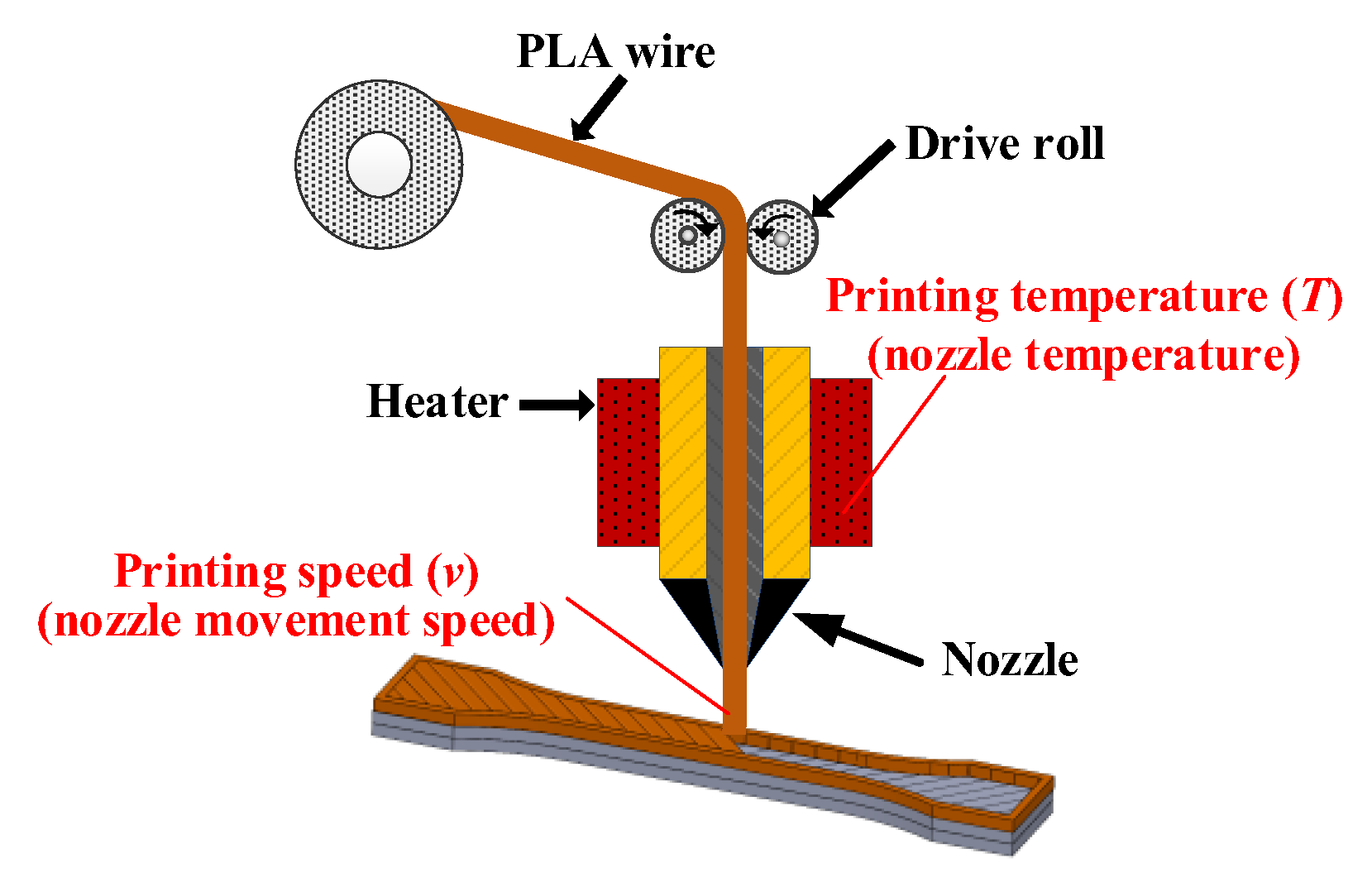

2.1. FDM principle and process parameters

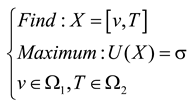

2.2. Optimization model

3. Kriging and CS

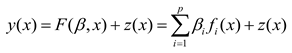

3.1. Kriging

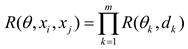

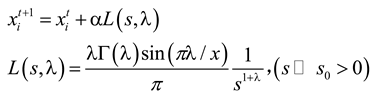

3.2. CS

- (1)

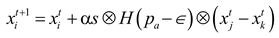

- Local random walks can be written as:

- (2)

- Global random walk flight using levy:

4. Proposed method

5. Case study

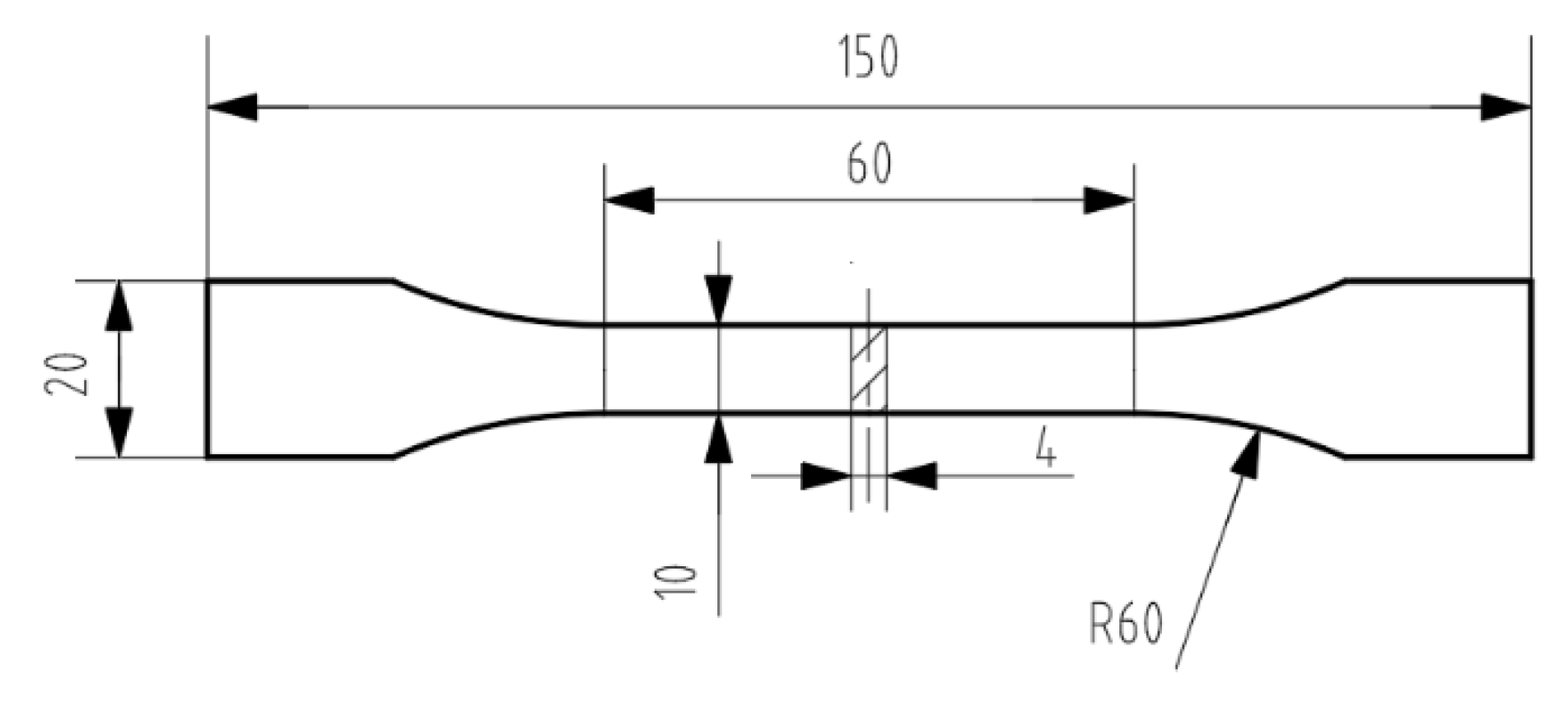

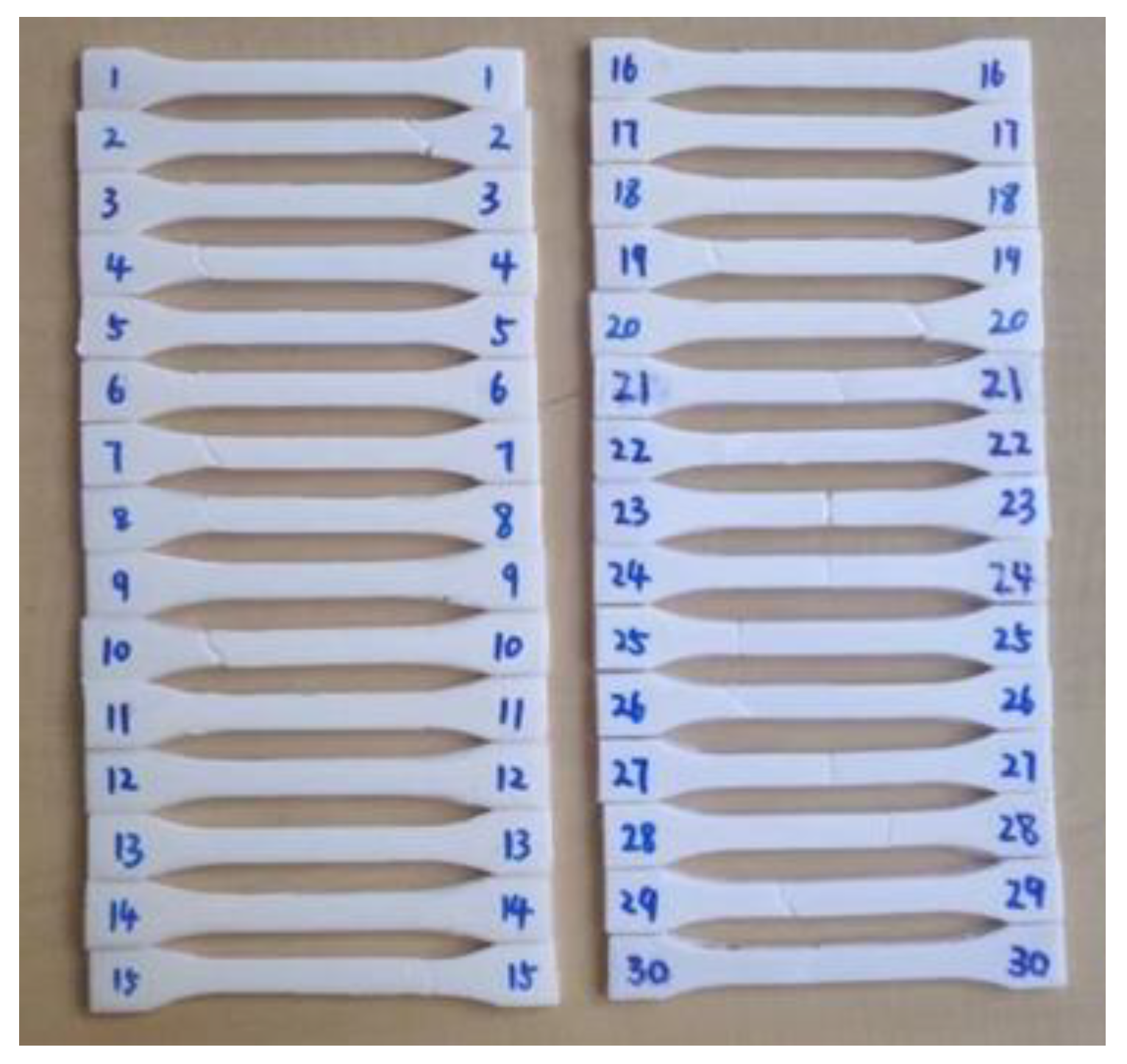

5.1. Experimental process

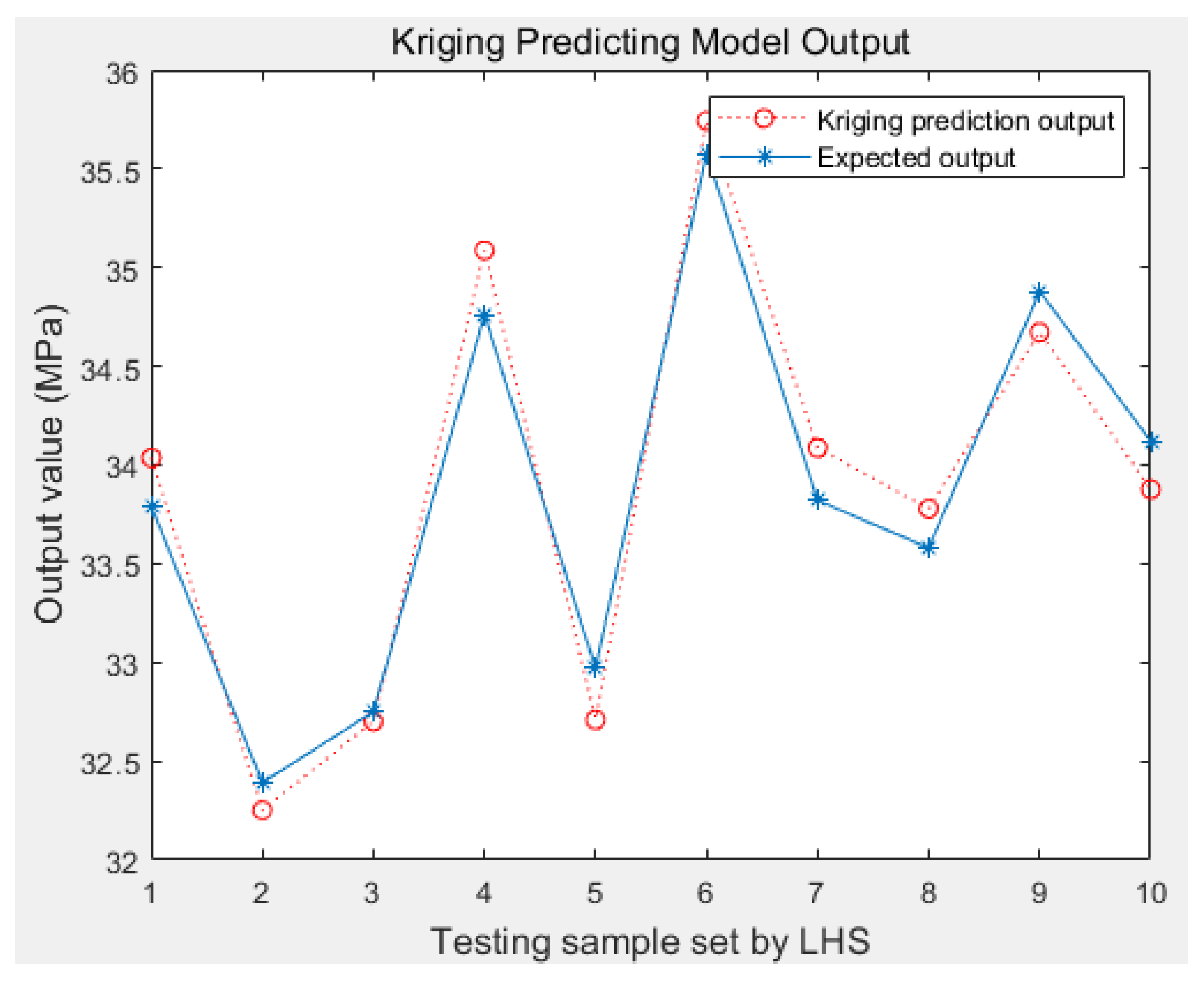

5.2. Result analysis

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Appendix

| No. | X | σ(X) (Mpa) | |

| v(mm/s) | T(°C) | ||

| 1 | 34 | 196 | 31.97 |

| 2 | 54 | 223 | 31.83 |

| 3 | 48 | 205 | 33.79 |

| 4 | 40 | 211 | 34.91 |

| 5 | 56 | 199 | 34.55 |

| 6 | 28 | 216 | 34.25 |

| 7 | 52 | 204 | 35.29 |

| 8 | 49 | 218 | 34.88 |

| 9 | 35 | 220 | 34.43 |

| 10 | 42 | 222 | 35.76 |

| 11 | 25 | 209 | 34.68 |

| 12 | 22 | 194 | 34.22 |

| 13 | 40 | 200 | 34.82 |

| 14 | 53 | 226 | 34.62 |

| 15 | 60 | 195 | 32.15 |

| 16 | 28 | 225 | 37.22 |

| 17 | 44 | 213 | 33.95 |

| 18 | 37 | 228 | 34.65 |

| 19 | 21 | 191 | 34.18 |

| 20 | 32 | 208 | 34.39 |

| 21 | 35 | 219 | 33.58 |

| 22 | 30 | 207 | 33.56 |

| 23 | 44 | 228 | 35.77 |

| 24 | 55 | 197 | 30.71 |

| 25 | 25 | 225 | 36.55 |

| 26 | 39 | 192 | 31.69 |

| 27 | 47 | 211 | 35.63 |

| 28 | 49 | 202 | 33.8 |

| 29 | 58 | 216 | 32.44 |

| 30 | 23 | 205 | 29.97 |

| No. | X | σ(X) (Mpa) | |

| v(mm/s) | T(°C) | ||

| 1 | 27 | 215 | 33.79 |

| 2 | 31 | 206 | 32.39 |

| 3 | 38 | 193 | 32.75 |

| 4 | 51 | 227 | 34.76 |

| 5 | 57 | 198 | 32.97 |

| 6 | 29 | 224 | 35.58 |

| 7 | 36 | 217 | 33.82 |

| 8 | 45 | 214 | 33.58 |

| 9 | 52 | 203 | 34.88 |

| 10 | 58 | 201 | 34.12 |

References

- Huang, S.H., et al., Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: a literature review. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2013. 67(5-8): p. 1191-1203. [CrossRef]

- Conner, B.P., et al., Making sense of 3-D printing: Creating a map of additive manufacturing products and services. Additive Manufacturing, 2014. 1-4: p. 64-76. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha Medibew, T., A Comprehensive Review on the Optimization of the Fused Deposition Modeling Process Parameter for Better Tensile Strength of PLA-Printed Parts. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2022. 2022: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Dey, A. and N. Yodo, A Systematic Survey of FDM Process Parameter Optimization and Their Influence on Part Characteristics. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 2019. 3(3): p. 64. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Reyna, S.L., et al., Mechanical properties optimization for PLA, ABS and Nylon + CF manufactured by 3D FDM printing. Materials Today Communications, 2022. 33: p. 104774. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H., et al., Effects of rCF attributes and FDM-3D printing parameters on the mechanical properties of rCFRP. Composites. Part B, Engineering, 2024. 270: p. 111122. [CrossRef]

- Portoacă, A.I., et al., Optimization of 3D Printing Parameters for Enhanced Surface Quality and Wear Resistance. Polymers, 2023. 15(16): p. 3419. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.J.R., F.A. de Almeida and G.F. Gomes, A multiobjective optimization parameters applied to additive manufacturing: DOE-based approach to 3D printing. Structures, 2023. 55: p. 1710-1731. [CrossRef]

- Alzyod, H., L. Borbas and P. Ficzere, Rapid prediction and optimization of the impact of printing parameters on the residual stress of FDM-ABS parts using L27 orthogonal array design and FEA. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2023. 93: p. 583-588. [CrossRef]

- Effects of fused deposition modeling process parameters on tensile, dynamic mechanical properties of 3D printed polylactic acid materials. Polymer Testing, 2020. 86.

- Khosravani, M.R., et al., Optimization of fracture toughness in 3D-printed parts: Experiments and numerical simulations. Composite Structures, 2024. 329: p. 117766. [CrossRef]

- Algarni, M., Tensile strength and strain behavior study and modeling of PLA printed parts with optimized AM parameters. Procedia Structural Integrity, 2023. 51: p. 185-191. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B., et al., Study of processing parameters in fused deposition modeling based on mechanical properties of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene filament. Polymer Engineering & Science, 2019. 59(1): p. 120-128. [CrossRef]

- Mani, M., et al., Optimization of FDM 3-D printer process parameters for surface roughness and mechanical properties using PLA material. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2022. 66: p. 1926-1931.

- Sahoo, S., et al., Experimental investigation and optimization of the FDM process using PLA. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2023. 74: p. 843-847. [CrossRef]

- Kafshgar, A.R., et al., Optimization of Properties for 3D Printed PLA Material Using Taguchi, ANOVA and Multi-Objective Methodologies. Procedia Structural Integrity, 2021. 34: p. 71-77. [CrossRef]

- Long, Y., et al., Multi-objective optimization for improving printing efficiency and mechanical properties of 3D-printed continuous plant fibre composites. Composites communications, 2022. 35: p. 101283. [CrossRef]

- Fountas, N.A., et al., Modeling and optimization of flexural properties of FDM-processed PET-G specimens using RSM and GWO algorithm. Engineering failure analysis, 2022. 138: p. 106340. [CrossRef]

- Patil, P., et al., Multi-objective optimization of process parameters of Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) for printing Polylactic Acid (PLA) polymer components. Materials today : proceedings, 2021. 45: p. 4880-4885. [CrossRef]

- Dusanapudi, S., et al., Optimization and experimental analysis of mechanical properties and porosity on FDM based 3D printed ABS sample. Materials today : proceedings, 2023.

- Singh, J., et al., Development of artificial intelligence-based neural network prediction model for responses of additive manufactured polylactic acid parts. Polymer composites, 2022. 43(8): p. 5623-5639. [CrossRef]

- Poonia, V., et al., Optimization of Specific Energy, Scrap, and Surface Roughness in 3D Printing Using Integrated ANN-GA Approach. Procedia CIRP, 2023. 116: p. 324-329. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., et al., Optimization of polylactic acid 3D printing parameters based on support vector regression and cuckoo search. Polymer engineering and science, 2023. 63(10): p. 3243-3253. [CrossRef]

| FDM parameters | Values | |

| PLA parameters | Filament diameter(mm) | 1.75 |

| Density(kg/m3) | 1250 | |

| FDM process parameters | Nozzle diameter(mm) | 0.4 |

| Filling rate(%) | 100 | |

| Layer thickness(mm) | 0.2 | |

| Raster angle(°) | [4,135] | |

| Substrate temperature(°C) | 30 |

| Optimal parameters | Minimum σ by CS | The corresponding σ by experiment | Relative error |

| (31 mm/s, 225℃) | 37.47MPa | 38.27 MPa | 2.09% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).