1. Introduction

The global ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic have been extensive, impacting a substantial portion of the world's population. Tragically, nearly 12 million lives have been lost due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [

1]. These viruses share similarities with the ones accountable for the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). However, they exhibit heightened contagiousness and aggression. [

2],[

3].

Indeed, complications of Coronavirus disease encompass severe interstitial pneumonia, hypoxemia, and respiratory distress syndrome. These complications often necessitate hospitalization, admission to intensive care units, and sadly, may result in fatalities [

4].

From the onset of the pandemic to date, numerous studies evaluated the potential outcomes of Coronavirus infection in pregnant women. In Italy, the SARS-CoV-2 rate was 6.04 per 1,000 births among pregnant women.in the year 2020. [

1] Among them, 72.1% experienced mild COVID-19 without pneumonia or the requirement for ventilatory support. The occurrence of severe disease was notably linked to women's pre-existing comorbidities, obesity, and citizenship from High Migration Pressure Countries [

5]. Some observations and limited evidence from few small-sized studies have hypothized that specific dietary regimen, specific nutrients, vitamins or supplements could potentially interfere with the outcomes of the Covid19 disease during pregnancy, eventually contributing to the prevention of complications related to gestational Coronavirus.

In this review, we aim to scrutinize the existing evidence in this area, and assessing whether nutritional outcomes may play such a role.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in electronic databases, namely PubMed, Medline, and Embase, focusing on the relationship between COVID-19 and the role of diet and micronutrients in pregnancy. To achieve this, we employed a combination of specific keywords (MeSH or Emtree), including "pregnancy OR pregnant women," "COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2," "nutritional," "vitamin," "mineral," and "diet." Our inclusion criteria were limited to publications in the English language. Additionally, we manually scrutinized the references of selected publications for additional relevant articles, which were subsequently included in our review. Our primary emphasis was placed on meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and large prospective or retrospective cohort studies. It is important to note that our article, being categorized as an expert review, did not involve the execution of a systematic review of the literature.

3. Results

3.1. COVID-19 and Pregnancy

Pregnancy markedly heightens the susceptibility of expectant mothers to infectious diseases, including COVID-19 infection. This increased vulnerability can be ascribed to physiological changes during pregnancy, such as the suppression of the maternal immune system to shield the foetus from potential immune reactions until delivery. Additionally, anatomical adaptations, including the elevation of the diaphragm in response to the expanding uterus, mucosal oedema in the respiratory tract, and increased oxygen requirements, contribute to this heightened susceptibility Inizio modulo[

6]. Contrary to initial conflicting data, current literature encompasses several systematic reviews and meta-analyses that consistently highlight an increased risk of Coronavirus infection among pregnant women. This specific vulnerability may contribute to an elevated risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes [

7],[

8],[

9].

In the third trimester of gestation, infection has been found to be linked to effects of a more substantial magnitude [

10]. Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 triggers distinctive inflammatory responses at the maternal-foetal interface and elicits humoral and cellular immune responses in the maternal blood. Additionally, it induces mild cytokine production in the neonatal circulation [

11].

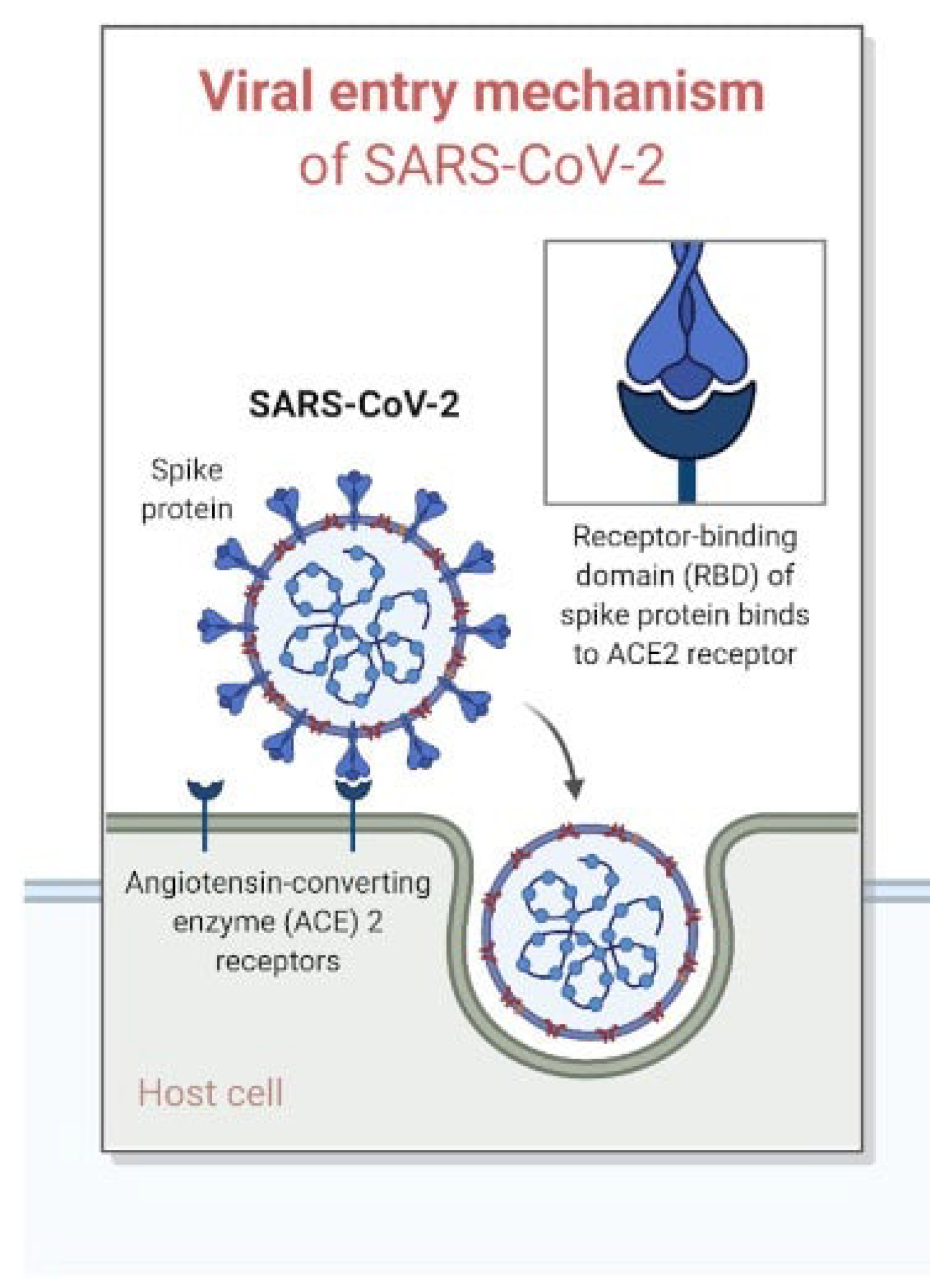

Numerous studies underscored the pivotal role of the ACE2 receptor, not solely in the initiation of Coronavirus infection but also in the pathogenesis of placental hypoxemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. This underscores a potential link between Coronavirus and maternal/foetal nutrition [

12].

3.2. Role of ACE2 Receptor in the Pathogenesis of Placental Hypoxemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

SARS-CoV-2 utilizes the ACE2 receptor as a functional entry point to infect human cells. This receptor is a carboxypeptidase within the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone (RAS) system, responsible for breaking down Angiotensin II into Angiotensin 1-7. (

Figure 1)

This enzymatic process can adversely affect the optimal perfusion of various tissues and organs. [

13]. Noteworthy, the ACE2 receptor is abundantly present in the tissues of the respiratory, cardiovascular, urinary, and digestive systems, playing a crucial role in maintaining continuous oxygenation essential for normal cellular functions. When the virus enters the human body through the ACE2 receptor, it leads to the depletion of this receptor in tissues where it is typically present in large quantities. This depletion results in a state of chronic hypoperfusion and hypoxia. At the placental level, these conditions translate into the occurrence of thromboangiopathic placental lesions, placental infarcts, and an increase in intervillous and subvillous fibrin [

14],[

15].

The process of placentation is intricately linked to the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAS), and COVID-19 has been demonstrated to influence this crucial process. Women infected with SARS-CoV-2 often display hypoperfusion and chronic hypoxia, leading to a higher incidence of foetal growth restrictions and preeclampsia [

13],[

16]. This is even more meaningful when considering that pregnant women, when infected with the Coronavirus, face an increased risk of acute respiratory failure. This exacerbates the already compromised perfusion and oxygenation, particularly at the placental level. Some of the adverse obstetric outcomes linked to this scenario of chronic hypoperfusion include the threat of abortion, premature birth, intrauterine growth restriction, oligoamnios, and even neonatal death [

17].

Indeed, this is one of the reasons why it is crucial to conduct a placental histological examination at the time of delivery in pregnant women infected with Coronavirus. This analysis actually helps to determine the long-term effects and to establish an appropriate follow-up program for these infants. Numerous case reports detailing severe placental changes have been published since the beginning of the pandemic to date. For instance, Moltner et al. [

18] documented a case involving a young pregnant woman hospitalized at 29 weeks + 5 days with Coronavirus disease, thrombocytopenia, and respiratory failure. Labor was induced at 34 weeks, leading to the delivery of a child with severe foetal growth restriction. Placental analysis revealed multiple indications of infarction and decreased perfusion, offering evidence of foetal growth arrest linked to placental vascular pathology secondary to Coronavirus. In the same year, Sukhikh et al. [

19] detailed the case of a woman afflicted with Coronavirus, admitted at 21 weeks g.a. with a foetus featuring severe growth restriction (at the 1st percentile), pathological Doppler readings in the umbilical artery, hydropericardium, and leukomalacia. At 26 weeks g.a., the woman delivered a baby who had an unfortunate postnatal course with exitus on his first day of life.

Even though the data is still limited, these findings reaffirm the association between the ACE2 receptor's role and the potential establishment of hypoperfusion at the placental level in the case of Coronavirus infection during pregnancy. These data point out the importance of vigilance during deliveries in these pregnancies and the necessity for requesting histological analysis of the placenta.

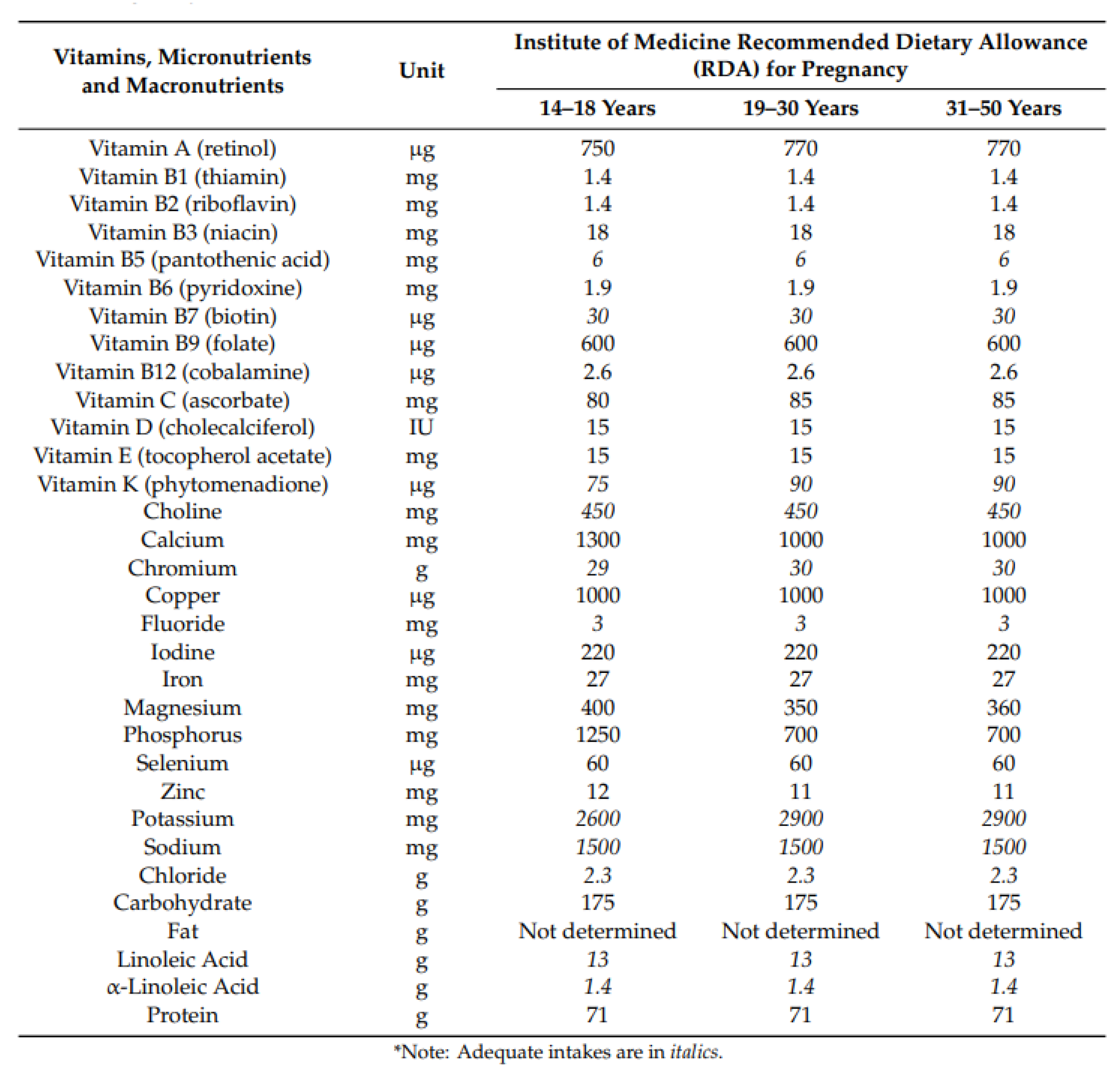

3.3. Recommended Dietary Allowances in Pregnancy

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine provide recommended dietary allowances (RDA) for micronutrients and vitamins during pregnancy [

20] (

Figure 2), which may slightly differ from recommendations by the WHO.

3.3.1. Role of Diet

The literature delves into the scope of dietary habits and nutritional strategies during pregnancy and their potential influence on the risk and severity of Coronavirus infection in expectant women. A well-balanced diet appears to enhance the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection [

21]. Simultaneously, the embrace of a healthy lifestyle, encompassing physical exercise alongside dietary considerations, may mitigate the risk factors associated with thrombotic complications of COVID-19 [

22]. Indeed, obesity is correlated with the hypercoagulopathy noted in severe cases of COVID-19. Pregnant women with COVID-19 may often exhibit elevated levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen. The influence of a high Body Mass Index (BMI) on the development of gestational diabetes (GDM) has been extensively studied [

23], revealing a significant impact on the immune system and an associated rise in circulating inflammatory cytokines during pregnancy [

24]. Pregnant women diagnosed with gestational diabetes (GDM), particularly those with a body mass index (BMI) exceeding 25 kg/m2, face an elevated risk of experiencing severe COVID-19 and may be more susceptible to admission to an intensive care unit [

25]. Obesity, diabetes mellitus, and elevated serum levels of IL-6 serve as predictive factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes in the context of COVID-19 infection. Additionally, heightened levels of IL-6 are observed in newborns born to infected mothers [

26]. In alignment with the previously mentioned information, findings from the INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study reveal that overweight women face a 20% increased risk of infection, and this risk escalates to 50% higher when the pregnancy is complicated by Gestational Diabetes [

27].

The role of carbohydrates in this infection has been extensively elucidated by Zhao et al. [

28]. They analyzed how the Coronavirus utilizes its highly glycosylated Spike protein to conceal ACE2 receptors from the cell, facilitating its entry into human cells. These findings underscore the potential impact of different dietary glycides intakes and of hyperglycemic peaks in elevating the risk of Coronavirus infection.

The Mediterranean diet has been recommended as a health-promoting dietary approach during the COVID-19 era [

29]. Abundant in vegetables, legumes, nuts, cereals, and fish, the Mediterranean diet has proven effective in preventing cardiovascular diseases, encompassing metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Moreover, it demonstrates the capability to lower HbA1c levels and body mass index [

30],[

31]. The Mediterranean diet can be regarded as a natural supplement incorporating fiber, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), and polyphenols. The gut microbiota emerges as a central target and participant in the interactions involving omega-3 PUFA, polyphenols, probiotics, and prebiotics within this dietary framework [

32] (

Figure 3).

3.4. Role of Vitamins

3.4.1. Vitamin D

In the literature, numerous studies have explored the role of vitamin D in pregnancies affected by COVID-19. Described as a secosteroid, vitamin D exhibits antifibrotic, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory actions [

33], and possesses antiviral properties. This is manifested through the activation of antimicrobial substances and its impact on the apoptosis and autophagy of infected cells [

34].

Moreover, an increasing body of evidence supports the immune-boosting and anti-inflammatory properties of vitamin D. Recent meta-analyses have demonstrated a positive correlation between vitamin D supplementation and the course of COVID-19 during pregnancy [

35]. For instance, reduced levels of vitamin D in pregnancies complicated by COVID-19 infection seem to be linked with preterm delivery and birth [

36]. Additionally, suboptimal values (<12 ng/mL) seem to be prevalent in pregnant women with mild COVID-19 infection compared to pregnancies not complicated by the virus [

37]. It is likely that an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first trimester of pregnancy and low vitamin D levels plays a significant role in the development of gestational hypertension [

38],[

39],[

40]. Considering the correlation between serum vitamin D levels and COVID-19 symptoms, it is advisable to contemplate measuring these levels during the second trimester of pregnancy and to recommend appropriate supplementation when necessary [

27]. The ideal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) level was established to be above 30 ng/ml [

41].

3.4.2. Vitamin A, B, C and E

The administration of vitamin A, B8 (myo-inositol), C, and E at optimum recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) during pregnancy holds promise and it is indicative of potential improvement in maternal and neonatal complications during COVID-19 infection, attributed to the reinforced immune system against viral infections and COVID-19 pneumonia [

42]. Concerning supplementation, in contrast to vitamin A, uncertainties about teratogenic effects at the beginning of the first trimester of pregnancy limit the recommendation only to certain populations, specifically those experiencing night blindness [

43].

Vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid, is a water-soluble vitamin with potent antioxidant activity and the capacity to combat infections. It plays a role in modulating the migration of neutrophils to the infection site and regulating phagocyte cells and NK cells [

44]. Within the healthy pregnant population, there is no compelling evidence that vitamin C supplementation, whether alone or in combination with other supplements, leads to significant additional benefits or harms [

45].

Vitamin E stands out as one of the most potent antioxidants in the human body, capable of inhibiting ferroptosis. A recent study indicates that lower vitamin E levels are correlated with elevated rates of adverse perinatal outcomes in pregnant women affected by COVID-19 [

46].

3.5. Role of Choline

Choline is an essential nutrient acquired through endogenous synthesis, although the primary intake is derived from the diet, both as a free molecule and in the form of phospholipids. Notably, phosphatidylcholines, which are found in organ meats, egg yolks, grains, vegetables, fruits, and dairy products, contribute significantly to dietary choline intake [

47]. Choline supplementation during pregnancy is essential for enhancing foetal brain development and reducing maternal risks of fatty liver and muscle damage [

48]. Both the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommend a daily choline intake ranging from 480 mg to 550 mg during both pregnancy and breastfeeding. Despite recommendations from various public health agencies and medical societies, choline intake often falls short, particularly in early gestation when crucial brain development occurs. Introducing a public health initiative promoting choline supplements could be beneficial for women planning or already pregnant, especially if exposed or infected with SARS-CoV-2 [

49],[

50]. Elevated choline levels, whether obtained through diet or supplements, may potentially safeguard foetal development and contribute to early infant behavioural development, even in cases where the mother contracts a viral infection in early gestation when the brain is forming. Several dietary surveys worldwide have revealed that relying solely on diet is insufficient to meet the recommended daily choline intake [

51],[

52]. Moreover, by incorporating choline through supplements, alongside dietary sources, the impact of polymorphisms in the PEMT gene (phosphatidylethanolamine transferase gene), which would otherwise reduce serum choline levels, can be mitigated [

53].

3.6. Role of Iron

An estimated 41.8% of pregnant women worldwide are affected by anemia, with at least half of this burden attributed to iron deficiency [

54]. Iron deficiency anemia is linked to an elevated risk of complications such as blood transfusion, preterm birth, cesarean delivery, and neonatal critical care unit hospitalization during delivery [

55]. The severity of COVID-19 appears to be higher in pregnancies diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia and is associated with low birth weight in newborns [

56]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend screening asymptomatic pregnant women for iron deficiency anemia using serum haemoglobin and ferritin levels. Additionally, they advocate universal iron supplementation with 30–60 mg/day of elemental iron during pregnancy. In cases associated with anemia, they suggest increasing the elemental iron intake to 60–120 mg/day [

57].

3.7. Role of Mineral

3.7.1. Zinc

The immune system requires adequate and proper nourishment for efficient operation. Zinc (Zn) is a crucial micronutrient essential for cell proliferation, differentiation, RNA and DNA synthesis, as well as cell structure and membrane stability. Compelling evidence establishes a link between zinc deficiency and various infectious disorders, given its role in regulating proinflammatory cytokines and managing oxidative stress [

58]. The recommended daily zinc supplementation for pregnant women is approximately 100 mg [

59].

3.7.2. Magnesium

Magnesium, as the fourth most abundant mineral in the human body, plays a vital role as a micronutrient involved in various functions, including immunity. The recommended daily magnesium intake for pregnant women falls within the range of 350–400 mg [

60]. While the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends daily calcium supplementation (1.5–2.9 g oral elemental calcium) in populations with low dietary calcium intake [

61], studies indicate that pregnant women supplementing their diet with calcium, zinc, and magnesium, or magnesium alone, did not experience a different clinical course of the disease during SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, they did exhibit significantly higher titers of anti-RBD SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after the infection had been eradicated. Therefore, supplementing the nutritional intake of pregnant women with magnesium-based supplements may be useful in achieving higher levels of anti-RBD SARS-CoV-2 antibodies [

62].

3.7.3. Calcium

Calcium has been demonstrated to play a role in the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells [

63]. Hypocalcemia has been associated with poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients [

64]. Consistent with findings in the literature, lower serum calcium levels and higher rates of hypocalcemia were observed in pregnant women with moderate/severe disease. Additionally, hypocalcemia showed a positive correlation with the severity of the disease [

65].

3.7.4. Selenium

Selenium holds a crucial position among essential trace elements for maintaining the human body's homeostasis. Its most vital function lies in contributing to the immune response against oxidative stress due to its antioxidant properties [

66]. Literature indicates that some studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between serum selenium levels and recovery and survival rates in patients with COVID-19 [

67],[

68], [

69]. The maternal selenium level is recognized as a significant parameter for pregnancy, maternal health, and infant health. A notable decrease in maternal selenium levels during pregnancy suggests an increased need for selenium due to foetal growth [

70]. The recommended intake of selenium for healthy adults falls in the range of 60–70 µg per day [

71]. While selenium substitution is strongly recommended for chronic or acute deficiency, supplementation for healthy subjects with sufficiently high baseline levels does not appear to be warranted [

72].

3.8. Role of Omega Omega-3 polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Adequate intake of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs), particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), could serve as an effective intervention to mitigate virus-related inflammation that poses a threat to pregnancy outcomes. N-3 PUFAs function as potent immunomodulators owing to their anti-inflammatory properties, potentially diminishing neonatal neurological disorders associated with viral infections during pregnancy [

73].

3.9. Role of Probiotic and Prebiotic

Numerous studies have demonstrated the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect and replicate in enterocytes of the human small intestine. Additionally, RNA virus detection has been observed in fecal samples, and alterations in the gut microbiota structure have been identified in SARS-CoV-2 positive patients [

74], [

75]. The nutritional status and diet play a significant role in the COVID-19 disease process, primarily due to the bidirectional interaction between gut microbiota and the lungs, referred to as the gut–lung axis. This interaction involves a mutual influence or bidirectional effect between gut microbiota and lungs [

76]. The immunomodulatory effect of probiotics and prebiotics on the development and maturation of innate and adaptive immunity occurs through the secretion of cytokines such as interleukin 10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). These cytokines control the development of regulatory T (Treg) cells and the response of helper T cells (Th1/Th2), ultimately influencing the release of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferons, and chemokines by immune cells. Treg cells are a crucial subpopulation of T cells responsible for suppressing inflammatory responses and maintaining immune system homeostasis [

77]. Patients with COVID-19 exhibit dysbiosis, indicating changes in the diversity and population of beneficial bacteria, which are associated with the severity of the disease [

78]. SARS-CoV-2 infections during pregnancy, particularly in the early stages, are linked to lasting changes in the microbiome of pregnant women, impacting the initial microbial seeding for their infants [

79]. Dysbiosis is transmitted from mother to child through the entero-mammary pathway and vertical transmission [

80]. Indeed, the maternal gastrointestinal tract serves as a source of bacteria for the milk microbiota, and the maternal gut microbiota is vertically transferred to the infant via human milk [

81].

4. Discussion

The immune system is pivotal in defending the body against infections. Pregnancy, being a unique immunological state, involves the maternal immune system safeguarding both maternal health and the growing foetus from invading foreign pathogens. This period is crucial for foetal growth, and inadequate intake of micronutrients can result in impaired foetal development, predisposing neonates to chronic conditions later in life, negatively impacting maternal health, and contributing to adverse neonatal outcomes. [

82]. COVID-19 impacts individuals of all ages and genders, with the severity of symptoms notably increasing in those with comorbidities such as obesity, malnutrition, and overall inadequate nutritional status leading to inflammation [

83]. A healthy diet, particularly an early Mediterranean diet program, proves beneficial for both mothers and offspring, reducing composite adverse maternal-foetal outcomes and it can be considered a valuable dietary option during pregnancy [

84].

Adopting an adequate lifestyle based on proper nutrition plans and feeding interventions, whenever feasible, becomes crucial in minimizing the risk of virus-related gestational diseases and associated complications in later life [

85]. Dietary modifications appear to be the most accessible and reliable means of maintaining glycaemic control and improving immune function, thereby decreasing the risk of COVID-19 and its consequences, especially in women with gestational diabetes [

86].

Maintaining a healthy diet, coupled with the consumption of probiotics and prebiotics, emerges as a significant nutritional strategy for preventing or serving as an adjuvant treatment for COVID-19 [

87]. This holds true even for individuals with inadequate nutritional status and an unbalanced gut microbiota [

88]. Future perspectives suggest that modulating the intestinal microbiota through probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics stands as a promising adjuvant approach to enhance the health of patients with COVID-19 [

89].

Both deficiencies in micronutrients and inadequate intake can compromise immune function, potentially increasing the risk of pregnancy complications associated with COVID-19. Micronutrients such as Vitamin A, C, D, E, and selected minerals including iron (Fe), selenium (Se), and zinc (Zn) are essential for immune competency and play a significant role in preventing adverse pregnancy outcomes [

44]. These micronutrients are beneficial in mitigating severe symptoms of COVID-19 and aiding in the prevention of infection [

90]. Notably, several studies have explored the role of vitamin D. While its routine supplementation is generally not recommended for pregnant women to improve maternal and perinatal outcomes [

61], the scenario changes in the context of pregnancies complicated by Covid-19, where vitamin D supplementation appears to be supported by numerous studies [

41].

The clinical effectiveness of vitamin C administration in managing COVID-19 remains controversial and inconclusive. Larger studies and trials are necessary to further investigate dosage [

91] and the role of supplementation (whether through supplements or diet) in pregnancy, especially concerning adverse outcomes.

Concerning the role of iron, dietary interventions, including increased iron intake, additional nutrient consumption, or general counselling, have proven effective in preventing or treating anemia in pregnant women [

92]. In Italy, iron supplementation is not routinely recommended for all women, but patients with haemoglobin levels below the normal for gestational age values should be monitored and investigated [

93]. It remains to be understood through targeted studies whether these considerations also apply to pregnancies complicated by COVID-19, given that the severity of the infection appears to be greater in pregnancies diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia.

Among the minerals examined in this treatise, magnesium appears to be the most promising. Its role in increasing antibody titers after COVID-19 infection during pregnancy warrants further investigation. In the adult population, micronutrient deficiency during hospital admission, including magnesium, seems to be associated with a high risk of admission to intensive care, intubation, and even death [

94]. Another mineral to consider is calcium. Mortality and complications from COVID-19 are higher in people with low calcium levels. Serum calcium serves as a prognostic factor in determining disease severity. Given that COVID-19 mortality and complications are elevated in individuals, including pregnant women, with lower calcium levels, it is recommended to assess serum calcium levels in initial evaluations [

95]. The role of supplementation in pregnancy complicated by COVID-19, whether through diet or supplementation, is currently under investigation.

The potential role of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs) during pregnancy to counteract the aggressive inflammatory response associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection is worth exploring [

96]. Additionally, we have highlighted in this review that choline can be a valuable aid in the management of viral infections contracted during pregnancy, particularly due to its significant role linked to the brain formation of the foetus [

97]. Whether this is also in COVID-19 infection remains however not elucidated. The constraints of this review stem from the authors' effort to provide the readers with a comprehensive perspective on the examined area. Unfortunately, this approach prevented the execution of a systematic review. Furthermore, a limitation of the study is its exclusive investigation of two databases. Nevertheless, we intentionally selected the two largest databases and adhered to rigorous methodological standards. It is crucial to interpret the outcomes of this review as a foundational standpoint, prompting further research rather than definitive conclusions on the analyzed topic.

5. Conclusions

Five years into the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, obstetricians and neonatologists still harbor concerns regarding the optimal management of pregnancies affected by Coronavirus infection. The findings of this review highlight the positive effects of a healthy diet, especially when combined with a healthy lifestyle. This approach can contribute to favourable outcomes even in pregnancies complicated by COVID-19 infection. The specific role of the Mediterranean diet and of specific nutrients requires further investigation, given some promising results elucidated in this review.

It is advisable and crucial that continuous research in the obstetric field can lead to implement evidence-based preventive measures against SARS-CoV-2 virus, including those related to nutrition, especially for patients who, are at a higher risk - as emphasized in this expert review.

Author Contributions

A. Messina: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. A. Mariani: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. PM: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing-review & editing, Supervision. L.L,BM: Validation, Writing-review & editing, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research received no external funding. MDPI vouchers (A.L.) were used for the open access publication of the article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Since this is a Review, no new data was generated or manipulated.

Acknowledgments

Biella Biomedical Library – 3Bi Foundation for research support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c. Accessed August 2024.

- Favre G, Pomar L, Musso D, Baud D. 2019-nCoV epidemic: what about pregnancies? Lancet 2020, 395, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections. Viruses 2020, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati S, Corsi E, Maraschini A, Salvatore MA, ItOSS COVID-19 Working Group, ItOSS COVID-19 WORKING GROUP. The first SARS-CoV-2 wave among pregnant women in Italy: results from a prospective population-based study. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2021, 57, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokken EM, Taylor GG, Huebner EM, Vanderhoeven J, Hendrickson S, Coler B, et al. Higher severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection rate in pregnant patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021, 225, 75.e1–75.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaigham M, Andersson O. Maternal and perinatal outcomes with COVID-19: A systematic review of 108 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020, 99, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio D, Sen C, Saccone G, Galindo A, Grünebaum A, Yoshimatsu J, et al. Risk factors associated with adverse fetal outcomes in pregnancies affected by Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a secondary analysis of the WAPM study on COVID-19. J Perinat Med 2020, 48, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, Kalafat E, van der Meulen J, Gurol-Urganci I, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Heal 2021, 9, e759–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlow AG, Castro VM, Shook LL, Kaimal AJ, Perlis RH. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 1 Year in Infants of Mothers Who Tested Positive for SARS-CoV-2 During Pregnancy. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2215787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Flores V, Romero R, Xu Y, Theis KR, Arenas-Hernandez M, Miller D, et al. Maternal-fetal immune responses in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang D, Wang L, Zhang C, Li Z, Wu H. Potential effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy on fetuses and newborns are worthy of attention. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2020, 46, 1951–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen S, Huang B, Luo DJ, Li X, Yang F, Zhao Y, et al. Pregnancy with new coronavirus infection: clinical characteristics and placental pathological analysis of three cases. Chinese J Pathol 2020, 49, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng WF, Wong SF, Lam A, Mak YF, Yao H, Lee KC, et al. The placentas of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a pathophysiological evaluation. Pathology 2006, 38, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinska-Kaczynska K, Malicka E, Szymusik I, Dera N, Pruc M, Feduniw S, et al. The sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio in Pregnant Patients Affected by COVID-19. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio D, Khalil A, Saccone G, Rizzo G, Buca D, Liberati M, et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020, 2, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moltner S, de Vrijer B, Banner H. Placental infarction and intrauterine growth restriction following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2021, 304, 1621–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhikh G, Petrova U, Prikhodko A, Starodubtseva N, Chingin K, Chen H, et al. Vertical Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Second Trimester Associated with Severe Neonatal Pathology. Viruses 2021, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and M. Dietary Reference Intakes tables and application. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Nutrition/SummaryDRIs/DRI-Tables.aspx.

- Chaari A, Bendriss G, Zakaria D, McVeigh C. Importance of Dietary Changes During the Coronavirus Pandemic: How to Upgrade Your Immune Response. Front Public Heal, 2020; 8. [CrossRef]

- Tsoupras A, Lordan R, Zabetakis I. Thrombosis and COVID-19: The Potential Role of Nutrition. Front Nutr 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Giannakou K, Evangelou E, Yiallouros P, Christophi CA, Middleton N, Papatheodorou E, et al. Risk factors for gestational diabetes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0215372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian LM, Porter K. Longitudinal changes in serum proinflammatory markers across pregnancy and postpartum: Effects of maternal body mass index. Cytokine 2014, 70, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskenazi B, Rauch S, Iurlaro E, Gunier RB, Rego A, Gravett MG, et al. Diabetes mellitus, maternal adiposity, and insulin-dependent gestational diabetes are associated with COVID-19 in pregnancy: the INTERCOVID study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022, 227, 74.e1–74.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Zheng J, Yang P, Wang X, Wei C, Zhang S, et al. The immunologic status of newborns born to SARS-CoV-2–infected mothers in Wuhan, China. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020, 146, 101–109.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, Thiruvengadam R, Rauch S, Kholin A, et al. Maternal and Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality Among Pregnant Women With and Without COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Pediatr 2021, 175, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao P, Praissman JL, Grant OC, Cai Y, Xiao T, Rosenbalm KE, et al. Virus-Receptor Interactions of Glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Human ACE2 Receptor. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 586–601.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Longo M, Caruso P, Esposito K. Mediterranean Diet and COVID-19: Hypothesizing Potential Benefits in People With Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Franquesa M, Pujol-Busquets G, García-Fernández E, Rico L, Shamirian-Pulido L, Aguilar-Martínez A, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiodiabesity: A Systematic Review through Evidence-Based Answers to Key Clinical Questions. Nutrients 2019, 11, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala O, English P, Pinkney J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of different dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 2013, 97, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso I, Romanelli L, Palmery M. Interactions between prebiotics, probiotics, polyunsaturated fatty acids and polyphenols: diet or supplementation for metabolic syndrome prevention? Int J Food Sci Nutr 2014, 65, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercola J, Grant WB, Wagner CL. Evidence Regarding Vitamin D and Risk of COVID-19 and Its Severity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarpak L, Filipiak KJ, Gasecka A, Gawel W, Koziel D, Jaguszewski MJ, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to treat SARS-CoV-2 positive patients. Evidence from meta-analysis. Cardiol J 2022, 29, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca A, Cosma S, Palermiti A, Costanzo M, Antonucci M, De Vivo ED, et al. Pregnancy and COVID-19: The Possible Contribution of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinaci S, Ocal DF, Yucel Yetiskin DF, Uyan Hendem D, Buyuk GN, Goncu Ayhan S, et al. Impact of vitamin D on the course of COVID-19 during pregnancy: A case control study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2021, 213, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahma G, Craina M, Dumitru C, Neamtu R, Popa ZL, Gluhovschi A, et al. A Prospective Analysis of Vitamin D Levels in Pregnant Women Diagnosed with Gestational Hypertension after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J Pers Med 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian R-H, Qi P-A, Yuan T, Yan P-J, Qiu W-W, Wei Y, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of vitamin D deficiency in different pregnancy on preterm birth. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e26303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaleel A, Al-Gailani L, Demir M, Aygün H. Vitamin D may prevent COVID-19 induced pregnancy complication. Med Hypotheses 2022, 158, 2021–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarpak L, Feduniw S, Pruc M, Ciebiera M, Cander B, Rahnama-Hezavah M, et al. The Vitamin D Serum Levels in Pregnant Women Affected by COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Parisa G, Soliman M-S, Afsaneh V. Micronutrients Supplementation in Pregnant Women during COVID-19 Pandemy: Pros and Cons. Trends Pharm Sci 2021, 7, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Bastos Maia S, Rolland Souza A, Costa Caminha M, Lins da Silva S, Callou Cruz R, Carvalho dos Santos C, et al. Vitamin A and Pregnancy: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawsherwan N, Khan S, Zeb F, Shoain M, Nabi G, Ul HI et al. Selected Micronutrients: An Option to Boost Immunity against COVID-19 and Prevent Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Pregnant Women: A Narrative Review. Iran J Public Health 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rumbold A, Ota E, Nagata C, Shahrook S, Crowther CA. Vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Erol SA, Tanacan A, Anuk AT, Tokalioglu EO, Biriken D, Keskin HL, et al. Evaluation of maternal serum afamin and vitamin E levels in pregnant women with COVID-19 and its association with composite adverse perinatal outcomes. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 2350–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim E, Park E. Choline intake and its dietary reference values in Korea and other countries: a review. Nutr Res Pract 2022, 16, S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, SH. Choline: Critical Role During Fetal Development and Dietary Requirements in Adults. Annu Rev Nutr 2006, 26, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman MC, Freedman R, Law AJ, Clark AM, Hunter SK. Maternal nutrients and effects of gestational COVID-19 infection on fetal brain development. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germano C, Messina A, Tavella E, Vitale R, Avellis V, Barboni M, et al. Fetal Brain Damage during Maternal COVID-19: Emerging Hypothesis, Mechanism, and Possible Mitigation through Maternal-Targeted Nutritional Supplementation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu D-M, Wahlqvist ML, Chang H-Y, Yeh N-H, Lee M-S. Choline and betaine food sources and intakes in Taiwanese. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2012, 21, 547–557. [Google Scholar]

- Brunst KJ, Wright RO, DiGioia K, Enlow MB, Fernandez H, Wright RJ, et al. Racial/ethnic and sociodemographic factors associated with micronutrient intakes and inadequacies among pregnant women in an urban US population. Public Health Nutr 2014, 17, 1960–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer LM, da Costa KA, Galanko J, Sha W, Stephenson B, Vick J, et al. Choline intake and genetic polymorphisms influence choline metabolite concentrations in human breast milk and plasma. Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 92, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Daily Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation in Pregnant Women. Vol. 7. 153-160. 2012.

- VanderMeulen H, Strauss R, Lin Y, McLeod A, Barrett J, Sholzberg M, et al. The contribution of iron deficiency to the risk of peripartum transfusion: a retrospective case control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uta M, Neamtu R, Bernad E, Mocanu AG, Gluhovschi A, Popescu A, et al. The Influence of Nutritional Supplementation for Iron Deficiency Anemia on Pregnancies Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nutrients 2022, 14, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffel NU, Von Siebenthal HK, Moretti D, Zimmermann MB. Oral iron supplementation in iron-deficient women: How much and how often? Mol Aspects Med 2020, 75, 100865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels I, Maywald M, Rink L. Zinc as a Gatekeeper of Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee BW, King JC. Effect of Zinc Supplementation on Pregnancy and Infant Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012, 26, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanni D, Gerosa C, Nurchi VM, Manchia M, Saba L, Coghe F, et al. The Role of Magnesium in Pregnancy and in Fetal Programming of Adult Diseases. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 3647–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Geneva S. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience 2016.

- Citu IM, Citu C, Margan M-M, Craina M, Neamtu R, Gorun OM, et al. Calcium, Magnesium, and Zinc Supplementation during Pregnancy: The Additive Value of Micronutrients on Maternal Immune Response after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri M, Bahrami A, Habibi P, Nouri F. A Review on the Serum Electrolytes and Trace Elements Role in the Pathophysiology of COVID-19. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 2475–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha JW, Wibowo A, Pranata R. Hypocalcemia is associated with severe COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev 2021, 15, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanacan A, Erol SA, Anuk AT, Yetiskin FDY, Tokalioglu EO, Sahin S, et al. The Association of Serum Electrolytes with Disease Severity and Obstetric Complications in Pregnant Women with COVID-19: a Prospective Cohort Study from a Tertiary Reference Center. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2022, 82, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiełczykowska M, Kocot J, Paździor M, Musik I. Selenium - a fascinating antioxidant of protective properties. Adv Clin Exp Med 2018, 27, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasani M, Djalalinia S, Khazdooz M, Asayesh H, Zarei M, Gorabi AM, et al. Effect of selenium supplementation on antioxidant markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hormones 2019, 18, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghaddam A, Heller R, Sun Q, Seelig J, Cherkezov A, Seibert L, et al. Selenium Deficiency Is Associated with Mortality Risk from COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Taylor EW, Bennett K, Saad R, Rayman MP. Association between regional selenium status and reported outcome of COVID-19 cases in China. Am J Clin Nutr 2020, 111, 1297–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol SA, Polat N, Akdas S, Aribal Ayral P, Anuk AT, Ozden Tokalioglu E, et al. Maternal selenium status plays a crucial role on clinical outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19 infection. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 5438–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipp AP, Strohm D, Brigelius-Flohé R, Schomburg L, Bechthold A, Leschik-Bonnet E, et al. Revised reference values for selenium intake. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2015, 32, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomburg, L. Selenium Deficiency Due to Diet, Pregnancy, Severe Illness, or COVID-19—A Preventable Trigger for Autoimmune Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong SF, Chow KM, Leung TN, Ng WF, Ng TK, Shek CC, et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004, 191, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh YK, Zuo T, Lui GC-Y, Zhang F, Liu Q, Li AY, et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021, 70, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar D, Mohanty A. Gut microbiota and Covid-19- possible link and implications. Virus Res 2020, 285, 198018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista KS, de Albuquerque JG, Vasconcelos MHA de, Bezerra MLR, da Silva Barbalho MB, Pinheiro RO, et al. Probiotics and prebiotics: potential prevention and therapeutic target for nutritional management of COVID-19? Nutr Res Rev 2023, 36, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters VBM, van de Steeg E, van Bilsen J, Meijerink M. Mechanisms and immunomodulatory properties of pre- and probiotics. Benef Microbes 2019, 10, 225–236. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang L, Gu S, Gong Y, Li B, Lu H, Li Q, et al. Clinical Significance of the Correlation between Changes in the Major Intestinal Bacteria Species and COVID-19 Severity. Engineering 2020, 6, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Castelán CJ, Vélez-Ixta JM, Corona-Cervantes K, Piña-Escobedo A, Cruz-Narváez Y, Hinojosa-Velasco A, et al. The Entero-Mammary Pathway and Perinatal Transmission of Gut Microbiota and SARS-CoV-2. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 10306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftwich HK, Vargas-Robles D, Rojas-Correa M, Yap YR, Bhattarai S, Ward D V. , et al. The microbiota of pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 and their infants. Microbiome 2023, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, JM. The origin of human milk bacteria: is there a bacterial entero-mammary pathway during late pregnancy and lactation? Adv Nutr 2014, 5, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernand AD, Schulze KJ, Stewart CP, West KP, Christian P. Micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy worldwide: health effects and prevention. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016, 12, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, He Z, Yu G, Peng D, Feng Y, Ling J, et al. The modified NUTRIC score can be used for nutritional risk assessment as well as prognosis prediction in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedullo AL, Schiattarella A, Morlando M, Raguzzini A, Toti E, De Franciscis P, et al. Mediterranean Diet for the Prevention of Gestational Diabetes in the Covid-19 Era: Implications of Il-6 In Diabesity. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mate A, Reyes-Goya C, Santana-Garrido Á, Sobrevia L, Vázquez CM. Impact of maternal nutrition in viral infections during pregnancy. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis 2021, 1867, 166231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Zegarra R, Dall’Asta A, Revelli A, Ghi T. COVID-19 and Gestational Diabetes: The Role of Nutrition and Pharmacological Intervention in Preventing Adverse Outcomes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton GE, Gibson GR, Hunter KA. Mechanisms linking the human gut microbiome to prophylactic and treatment strategies for COVID-19. Br J Nutr 2021, 126, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernocchi P, Del Chierico F, Putignani L. Gut Microbiota Metabolism and Interaction with Food Components. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier-Santos D, Padilha M, Fabiano GA, Vinderola G, Gomes Cruz A, Sivieri K, et al. Evidences and perspectives of the use of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics as adjuvants for prevention and treatment of COVID-19: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2022, 120, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesci A, Pergolizzi S, Fumia A, Miller A, Cernigliaro C, Zaccone M, et al. Immune System and Psychological State of Pregnant Women during COVID-19 Pandemic: Are Micronutrients Able to Support Pregnancy? Nutrients 2022, 14, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani GP, Macchi M, Guz-Mark A. Vitamin C in the Treatment of COVID-19. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Skolmowska D, Głąbska D, Kołota A, Guzek D. Effectiveness of Dietary Interventions in Prevention and Treatment of Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salute ministero della Salute. Gravidanza fisiologica 2010.Accessed August 2024. ttps://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1436_allegato.pdf.

- Pechlivanidou E, Vlachakis D, Tsarouhas K, Panidis D, Tsitsimpikou C, Darviri C, et al. The prognostic role of micronutrient status and supplements in COVID-19 outcomes: A systematic review. Food Chem Toxicol 2022, 162, 112901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh E, Alemzadeh E, Ziaee M, Abedi A, Salehiniya H. The effect of low serum calcium level on the severity and mortality of Covid patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Immunity, Inflamm Dis 2021, 9, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman R, Hunter SK, Law AJ, Wagner BD, D’Alessandro A, Christians U, et al. Higher Gestational Choline Levels in Maternal Infection Are Protective for Infant Brain Development. J Pediatr 2019, 208, 198–206.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).