1. Introduction

These materials possess at least one dimension that lies within the nanometer scale. [

1]. New nanostructured materials have surprising magnetic, optical, electrical, and mechanical properties, and these nanostructured materials are being utilized in electronics, bioengineering, information technology, and environmental applications. Nanomaterials are a crucial part of nanoscience and are vital in nanotechnology. They are essential because of their unique properties on a tiny scale, enabling new and valuable applications in various scientific areas [

2]. Magnetite, identified by the chemical formula Fe

3O

4, is categorized as a type of iron ore and exhibits a rock-like mineral appearance. As an iron oxide, it demonstrates ferrimagnetic characteristics, capable of acquiring permanent magnetism in a magnetic field. The magnetized form, recognized as lodestone, possesses a distinctive brownish-black or black coloration with inherent luster. Its chemical configuration is represented as Fe

2+Fe

23+O

42−, and its structural arrangement shows inverse spinel configuration [

3]. The application of magnetism and ferrites is spread across various fields, leading to vast research and discourse within the scientific community. The revolutionary properties of ferrites have gained significant attention from researchers and scientists. Many ferrites have been synthesized and analyzed using different methods, including hydrothermal synthesis, sol-gel techniques, sputtering, spin coating, and other appropriate approaches for nanoparticle preparation. Researchers have focused on investigating the magnetic, electrical, and optical properties through various methodological approaches, contributing to an enhanced property of these materials [

4].

The importance of the physical and chemical properties of multi-component inorganic nanostructured materials has inspired both technological and scientific interest. This interest urges the development of various devices, including those with magnetic, electric, catalytic, and spintronic functionalities [

5]. Hydrothermal synthesis is an extensively used method for producing nanomaterials through solution-based reactions across several temperatures. The process enables control over material morphology and size by adjusting temperature and pressure conditions according to vapor pressure. This method offers advantages such as synthesizing unstable nanomaterials at higher temperatures and minimizing material loss for those with high vapor pressures.

Furthermore, hydrothermal synthesis allows precise control over nanomaterial structures through liquid or multiphase chemical reactions. Recent research within this domain involves various nanomaterials, including nanoparticles, nanorods, nanotubes, hollow nanospheres, and graphene nanosheets. Novel synthesis techniques like microwave-assisted hydrothermal and template-free self-assembling catalytic synthesis have also emerged, alongside efforts to optimize synthesis conditions [

6,

7]. Ma et al. synthesized Co-doped Zn

1-xCo

xMn

2O nanocrystals that form hollow nanospheres by hydrothermal methods. Co-doping reduced crystalline size, narrowed the band gap, and enhanced photocatalytic activity, particularly in methyl orange degradation under visible light, suggesting potential for pollutant remediation [

8]. Monica et al. synthesized Zirconia-doped hematite nanoparticles, xZrO

2-(1−x) α-Fe

2O

3 (x=0.1 and 0.5), for gas sensing application [

9]. Majid et al. synthesized Zn-doped nickel ferrites via the hydrothermal method, revealing structural changes with XRD and FTIR, increased saturation magnetization with higher Zn concentrations via VSM, and alterations in dielectric properties with impedance analysis, indicating the significant impact of Zn doping on nickel ferrite’s characteristics [

10]. Hossain et al. synthesized Co-Zn ferrite via sol-gel, sintered at 900°C. XRD confirmed single-phase inverse spinel; SEM showed heterogeneous morphology, and VSM revealed decreasing coercivity (36.08Oe) with higher Zn content, and dielectric analysis indicated Maxwell-Wagner polarization at room temperature [

11]. Shifa et al. (2019) investigated Zr substitution effects on Co, Zn spinel properties via co-precipitation. They synthesized Co

0.5Zn

0.5Zr

xFe

2-xO

4 ferrites (x=0.00-1.00), characterized by FTIR, XRD, and SEM. XRD revealed particle sizes (12nm-48nm), VSM confirmed single-phase spinel ferrites with coercivity (144.44Oe) and remanence magnetization (13.72 emu/g) [

12].

In this paper, the structural, magnetic, and dielectric properties of Cobalt (Co) and Zirconium (Zr) co-doped Iron oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles, synthesized by hydrothermal method, are illustrated. The nanoparticles show good ferromagnetic properties, which makes them promising candidates for magnetic storage devices to increase the memory of devices.

2. Experimental Set-Up/Section

2.1. Materials

Hydrothermal synthesis was used to prepare cobalt-zirconium-iron oxide (CZIO) nanoparticles. The precursors CoCl2.6H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.99 % pure), FeCl2.4H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.99 % pure), ZrOCl2.8H2O (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.99 % pure), and distilled water were used without any further purification.

2.2. Preparation of Cobalt Zirconium Iron Oxide (CZIO) Nanoparticles

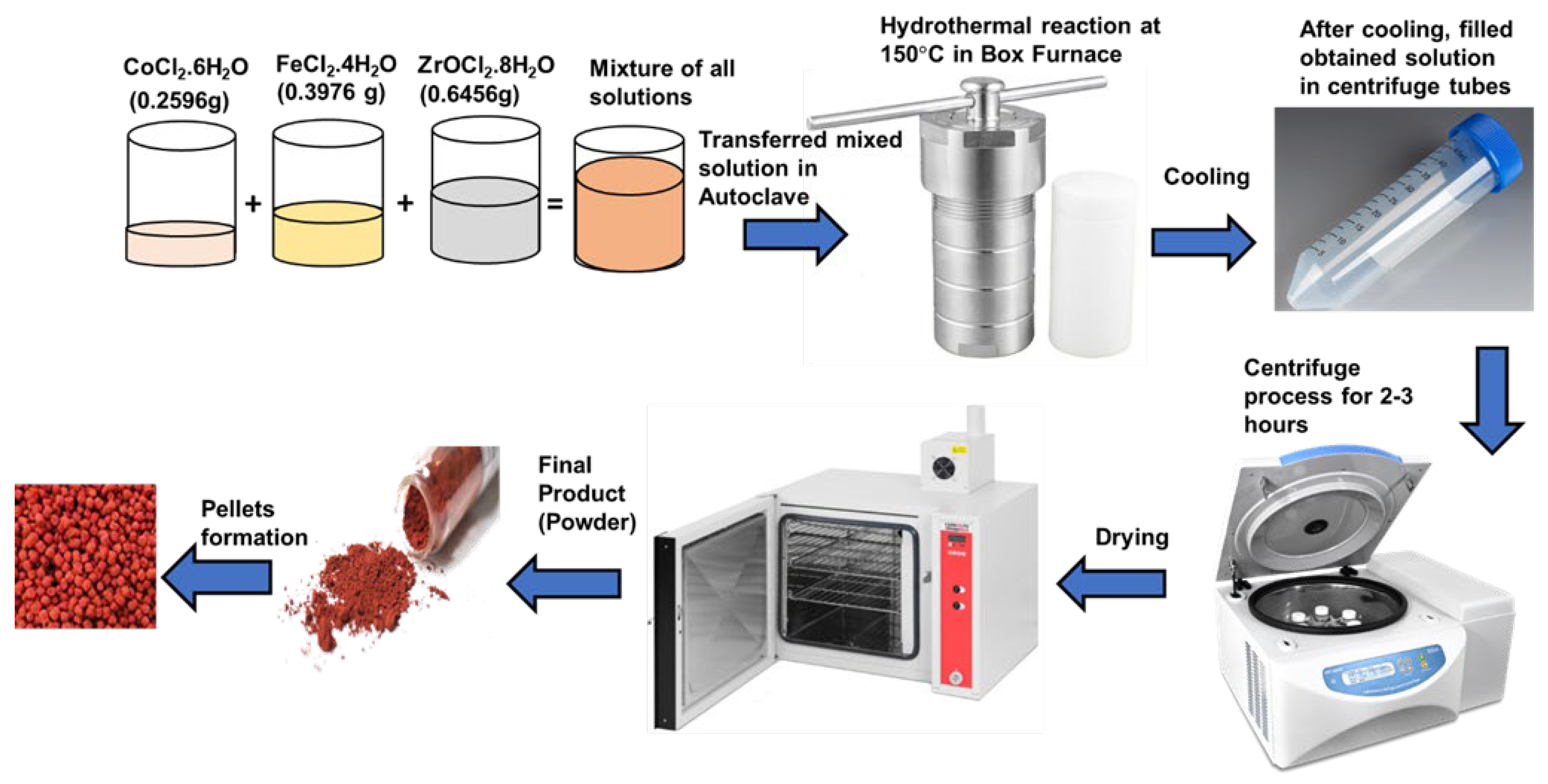

In the hydrothermal synthesis of co-doped CZIO nanoparticles, a precision balance was used to quantify different salts accurately. 0.645g of ZrOCl2.8H2O (pH 1), 0.2596g of CoCl2.6H2O (pH 6), and 0.3976g of FeCl2.4H2O (pH 2) salts, along with 20ml of distilled water, were measured and placed in separate 100ml beakers. The pH values of each solution were individually determined, reflecting the distinct pH levels associated with the different salts.

The salts were then thoroughly mixed in distilled water through a continuous stirring process facilitated by the inorganic nature of the salts. Combining the three solutions resulted in a final pH of 1. The prepared solution was tightly sealed into a Teflon-lined autoclave to generate high pressure and temperature. The autoclave was placed in a Box furnace at 150°C for varying durations, yielding five distinct samples with respective furnace times of 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours. Upon completion of the hydrothermal treatment, each sample was allowed to cool and subsequently placed in centrifuge tubes for 2-3 hours. The centrifugation separated the nanoparticles, causing them to settle at the bottom of the tube. The water was removed post-centrifugation, and the nanoparticle samples were retrieved using a spatula. The obtained samples were then dried in an oven, resulting in powdered form nanoparticles.

This powdered form constituted the final sample, from which pellets were made as needed for further characterization. The detailed procedure ensures accuracy and reproducibility in synthesizing and characterizing cobalt zirconium co-doped iron oxide nanoparticles. The schematic process is shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Characterization of Prepared Nanoparticles

In this study, Lake Shore Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM), and Precision impedance analyzer (Wayne Kerr 6500B series) were employed for the comprehensive characterization of magnetic, and dielectric properties of the synthesized material. The experimental results spurted from the analytical tools are discussed in the following paragraphs, contributing to a thorough understanding of CZIO nanoparticle properties.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. VSM Analysis

The magnetic properties were evaluated using a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM), a technique employed to derive the Magnetization-Hysteresis (M-H) loop, providing a comprehensive representation of the magnetic characteristics exhibited by the nanoparticles. Ferromagnetic materials exhibit high magnetic susceptibility when subjected to an external magnetic field due to the phenomenon of spin orientation induced by quantum mechanical effects and exchange interactions. Specifically, unpaired electrons from different atoms tend to align within localized regions along the magnetic field direction. When exposed to a magnetic field, this alignment results in certain materials attaining permanent magnetization characteristics [

13].

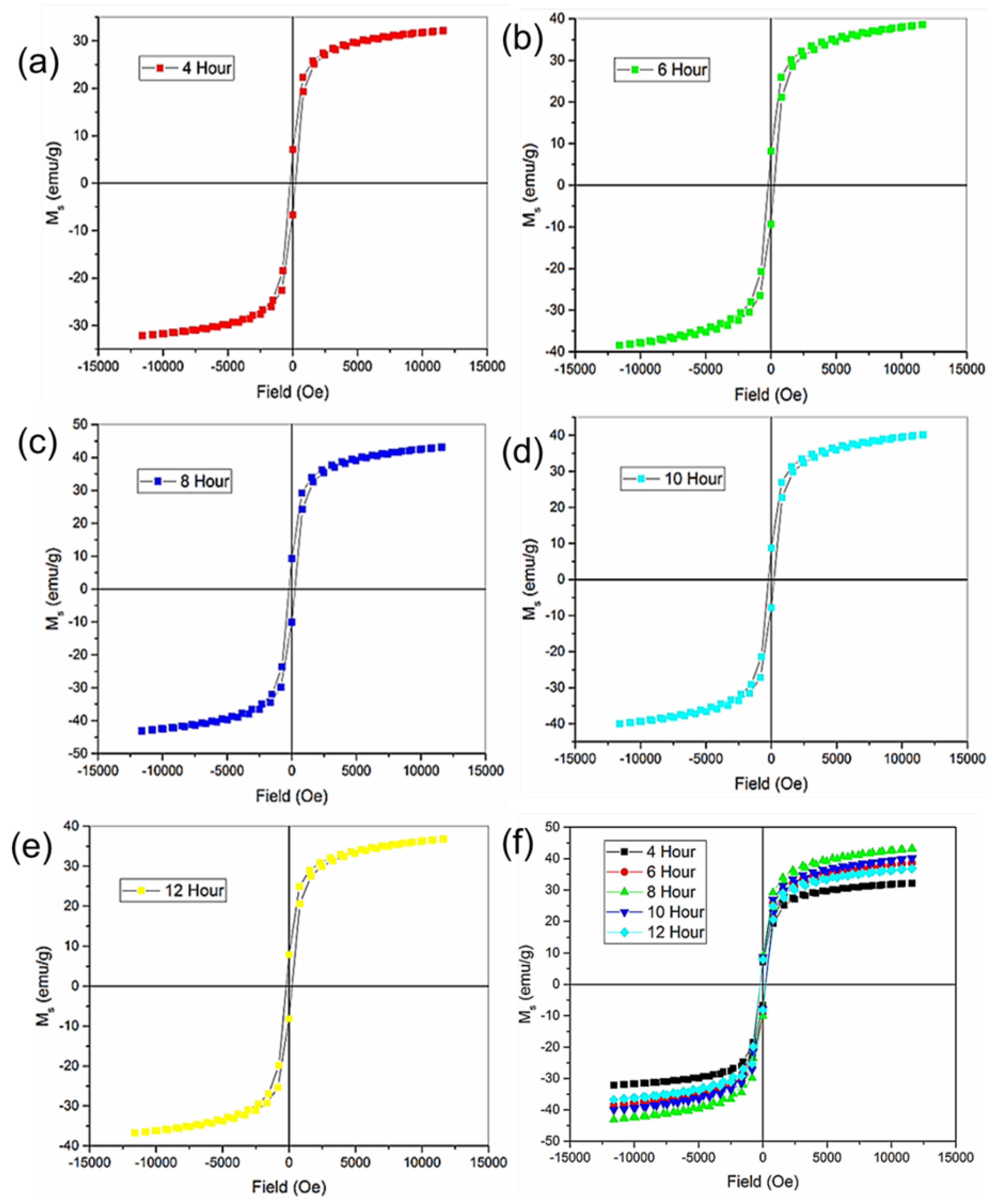

In the experimental context, CZIO, a ferromagnetic material, was the subject of investigation, as shown in

Figure 2. Magnetic fields were systematically applied and studied for five prepared nanoparticle samples varying in exposure furnace time of 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours. The collective analysis of these experiments produced a composite graph illustrating the average saturation value, ranging between -40 and 40 emu/g. This result signifies the material’s magnetic saturation response due to the applied magnetic field, offering insights into its magnetic properties under different experimental conditions. Cobalt and zirconium doping introduce additional magnetic moments in the iron oxide lattice, enhancing its magnetization. Cobalt ions (Co

2+) have unpaired electrons in their d orbitals, making the lattice inherently magnetic. Zirconium doping affects the magnetic properties of iron oxide by altering its lattice structure and electronic configuration by changes in spin ordering, magnetic moments, and magnetic coupling between atoms in the lattice. The nanoparticle’s size and shape also affect the magnetic behavior. Small-sized nanoparticles tend to exhibit superparamagnetic behavior. Larger nanoparticles can exhibit ferromagnetic behavior due to the alignment of magnetic moments within the particles. The interactions between neighboring nanoparticles also contribute to the observed ferromagnetic behavior. These interactions align the magnetic moments in the same direction, reinforcing the overall magnetization as reported in [

14].

3.2. Dielectric Constant Measurements

Dielectric materials, such as electrical insulators, become energized when exposed to an electric field. Unlike conductors, they undergo infinitesimal charge displacements, known as dielectric polarization, rather than allowing the charges to flow through. When the material consists of weakly bound molecules, these molecules reorient in alignment with the electric field, enhancing polarization. Dielectrics are essential in applications like capacitor energy storage, photocopier functionality, and charge storage in laser printers. Their characteristics involve energy dissipation and storage within the material, impacting fields such as solid-state physics, electronics, optics, and biophysics. The versatile contributions of dielectric materials span diverse scientific disciplines and technological advancements [

15]. The dielectric constant, ε ⃰, is expressed as follows:

where εꞌ, the real part of the dielectric constant, characterizes the stored energy within a material under the influence of an electric field. Conversely, εꞌꞌ, the imaginary part of the dielectric constant, reflects the dissipated energy within the material. The determination of the real part of the dielectric constant (ɛ′) is facilitated through a prescribed mathematical formulation.

where εₒ is the permittivity of free space (equal to 8.85 × 10

−12 F/m), t is the thickness of the pellet, A is the cross-sectional area of the pellet, and CP is the capacitance of the specimen expressed in Farad. The imaginary part of the dielectric constant (ɛ″) is calculated as:

where tanδ is the dielectric loss [

16].

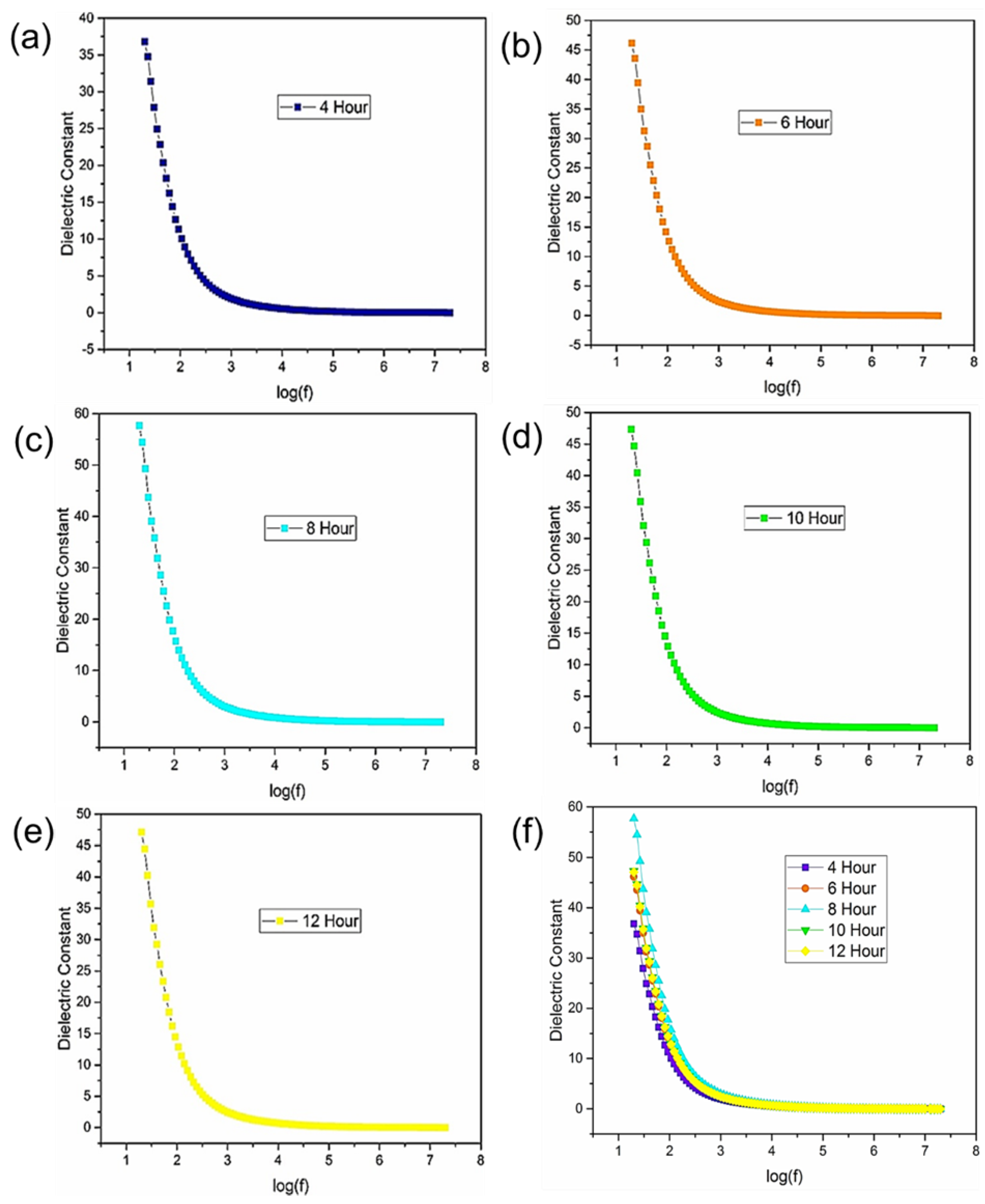

Figure 3 shows the observed fluctuations in the dielectric constant with the frequency at room temperature. The frequency was reported on a logarithmic scale. It was seen that the dielectric constant decreases with an increase in frequency, which is a usual dielectric behavior [

17]. The different characteristic curves can be explained through Koop’s theory based on the Maxwell-Wagner model [

18,

19]. This model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how interfaces between different phases or constituents within a material influence its dielectric properties. Initially, the dielectric constant establishes its highest peak at lower frequencies, such as log1.5 Hz. According to Koop’s theory, this phenomenon arises from the ability of dipoles within the material to readily align with the applied electric field. The ease of alignment allows for enhanced polarization, resulting in a higher dielectric constant.

However, as the frequency increases, the mobility of dipoles becomes increasingly restricted due to the time constraints imposed by the alternating electric field. This limitation stems from the dipoles’ inability to rapidly reverse their polarity in response to the rapidly changing electric field. As a result, between frequencies of log 2 to log 3 Hz, a significant decrease in the dielectric constant is observed. Furthermore, imperfections such as impurities and defects within the sample structure increase this phenomenon, leading to deviations from ideal dielectric behavior. These imperfections hinder the movement of dipoles, thereby contributing to the observed reduction in the dielectric constant.

Moreover, beyond log 4 Hz, the dielectric constant exhibits a constant behavior, indicating that the impact of dipole mobility restrictions becomes less noticeable, and the dielectric response becomes frequency independent. In short, Koop’s theory based on the Maxwell-Wagner model offers valuable insights into the atomic-scale mechanisms governing the observed fluctuations in the dielectric behavior of the material. The maximum value of the dielectric constant is approximately 58 at a logarithmic frequency of approximately 1.5 was obtained in the sample synthesized over 8 hours, emphasizing the influence of synthesis parameters on the dielectric properties of the material.

3.3. Tangent Loss Measurements

The tangent loss or loss factor, tan δ, measures the energy dissipation within the dielectric system. It describes how much electrical energy is utilized in different processes like electrical conduction, dielectric resonance, and relaxation of materials. This loss occurs because of a delay between the electric field and the movement of charged particles. So, the total dielectric loss is the sum of intrinsic and extrinsic losses. In a perfect crystal, intrinsic losses depend primarily on the crystal structure and are caused by interactions between phonons and the electric field. Gurevich and Tagantsev explain this behavior [

20]. Extrinsic losses are related to imperfections in the crystal, like boundaries between grains, small cracks, or other defects. These losses can be reduced with careful material processing. The amount of loss also depends on temperature and frequency. In a perfect material, intrinsic losses establish a theoretical limit for potential losses, whereas extrinsic losses are associated with imperfections or defects in the crystal structure [

21].

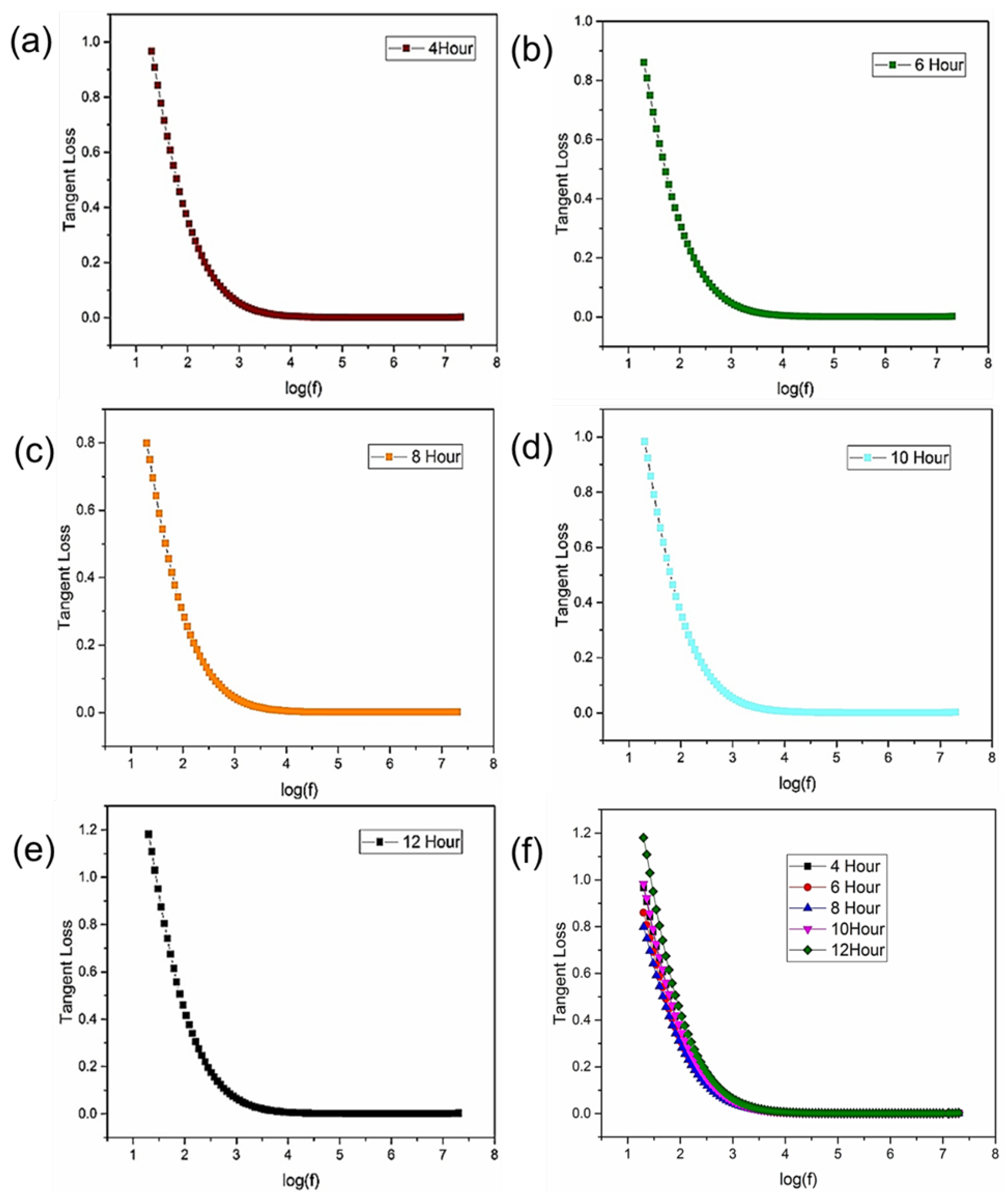

Figure 4 illustrates distinct tangent loss curves, each describing the frequency-dependent energy dissipation behavior within the dielectric material. According to Koop’s theory, which furnishes a comprehensive framework for understanding dielectric phenomena, the tangent loss dynamics with frequency explain the energy dissipation mechanisms. Notably, the tangent loss rapidly increases at lower frequencies, revealing the maximum energy dissipation during dipole vibration and material damping [

22]. A visible reduction in tangent loss is noticeable within the narrow frequency range of log 2 to log 3 Hz, and a constant trend is achieved beyond log 4 Hz, as expected. Structural defects, complex interfacial interactions, or inherent material flaws may interrupt the energy dissipation mechanism, leading to an unexpected increase in tangent loss within the specified frequency range log1.5 Hz.

3.4. Comparative Graph of Dielectric Constant and Tangent Loss

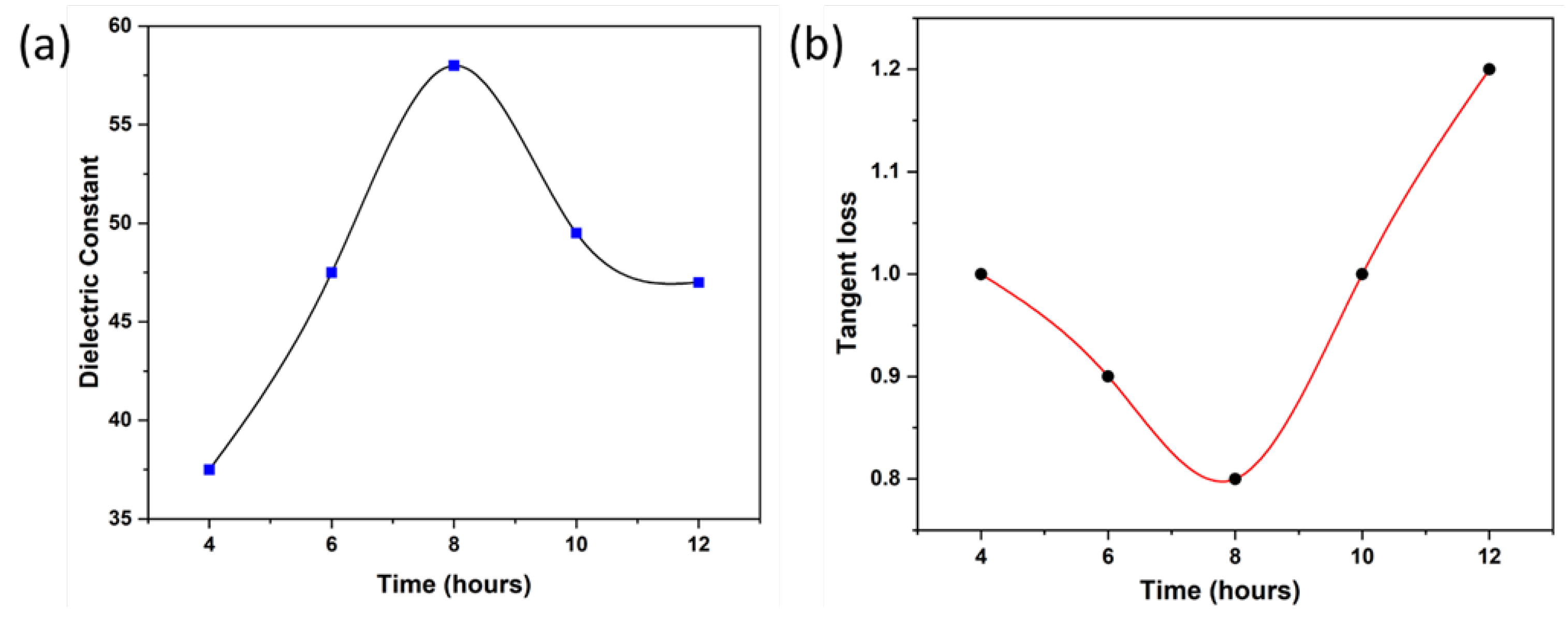

Figure 5(a) indicates the comparative results of dielectric constant graph at a fixed frequency log 1.5. In the first three samples from 4 to 8 hours there is a maximum increase in dielectric constant value that suggests that polarization is increased to approximately 58. After that dielectric constant value is decreased. So, 8 hours sample is our optimal sample.

Figure 5(b) indicates tangent loss graph at a fixed frequency. At first prepared nanoparticles do not lose much energy but for 10-hours and 12-hours samples tangent losses are very high due to complex interfacial interactions and structural defects in the crystals.

4. Conclusions

The present study investigates the magnetic, and dielectric properties of iron oxide nanoparticles co-doped with cobalt and zirconium, synthesized via the hydrothermal method at a temperature of 150°C for different synthesis times of 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours was explored. A soft ferromagnetic MH loop was also observed, with maximum magnetic saturation attained under the 8-hour synthesis condition. Furthermore, dielectric properties were investigated by using Maxwell-Wagner’s model and Koop’s theory. Dielectric and tangent loss analyses, conducted using an impedance analyzer over a wide frequency range at room temperature, revealed frequency-dependent behaviors. Notably, the dielectric constant peaked for samples synthesized over 8 hours, indicating optimal synthesis conditions. These findings suggest that the co-doping of cobalt and zirconium facilitated the accomplishment of a specific crystal phase of iron oxide and reported soft ferromagnetic characteristics. Overall, the observed properties position this material as a promising candidate for magnetic storage device applications to increase device memory.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.A.; revision and analysis, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hochella Jr, M. F. Nanoscience and technology: the next revolution in the Earth sciences. EPSL. 2002, 203(2):593-605. [CrossRef]

- Schummer, J. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and patterns of research collaboration in nanoscience and nanotechnology. Scientometrics 2004, 59, 425–465. [CrossRef]

- Mishra M, Chun, DM. α-Fe2O3 as a photocatalytic material: A review. Appl Catal. A. 2015, 498:126-141. [CrossRef]

- Gore SK, Jadhav SS, Jadhav VV, Patange SM, Naushad M, Mane RS, Kim KH. The structural and magnetic properties of dual phase cobalt ferrite. Sci Rep. 2017, 7: 2524. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav VV, Shirsat SD, Tumberphale UB, Mane RS. Properties of ferrites. In: Spinel Ferrite Nanostructures for Energy Storage Devices. Elsevier. 2020, (pp. 35-50). [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xu, R. New Materials in Hydrothermal Synthesis. Accounts Chem. Res. 2000, 34, 239–247. [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.X.; Jayatissa, A.H.; Yu, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, M. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Nanomaterials. J. Nanomater. 2020, 2020, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Ma L, Wei Z, Zhu X, Liang J, Zhang X. Synthesis and photocatalytic properties of co-doped Zn 1-x Co x Mn 2 O hollow nanospheres. J Nanomater. 2019, p.4257270. [CrossRef]

- Sorescu, M.; Diamandescu, L.; Tomescu, A.; Krupa, S. Synthesis and sensing properties of zirconium-doped hematite nanoparticles. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2009, 404, 2159–2165. [CrossRef]

- Majid F, Rauf J, Ata S, Bibi I, Yameen M, Iqbal M. Hydrothermal synthesis of zinc doped nickel ferrites evaluation of structural, magnetic and dielectric properties. ZPC. 2019,233:1411-1430. [CrossRef]

- Hossain MS et al. Synthesis, structural investigation, dielectric and magnetic properties of Zn 2+-doped cobalt ferrite by the sol–gel technique. J Adv Dielectr. 2018, 8:1850030. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L X, Li, S, Zhang, J, Chen, Z, & Xu, S C. Preparation, characterization and magnetic property of MFe2O4 (M= Mn, Zn, Ni, Co) nanoparticles. Open J Adv Mater Res. 2014, 842:35-38. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Mandal, M.; Gayathri, N.; Sardar, M. Enhancement of ferromagnetism upon thermal annealing in pure ZnO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 182501. [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D.; Atherton, D. Theory of ferromagnetic hysteresis. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1986, 61, 48–60. [CrossRef]

- Anju, V.; Narayanankutty, S.K. High dielectric constant polymer nanocomposite for embedded capacitor applications. Mater Sci Eng B. 2019, 249, 114418. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A.; Nisar, A.; Fatma, B.; Khan, W.; Chaman, M.; Azam, A.; Naqvi, A. Temperature dependence anomalous dielectric relaxation in Co doped ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 4161–4168. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Sharma, N.; Parashar, J.; Saxena, V.; Bhatnagar, D.; Sharma, K. Dielectric properties of nanocrystalline Co-Mg ferrites. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 649, 362–367. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell JC. Electricity and magnetism. New York: Dover 1954, (Vol. 2, pp. 257-257).

- Mark, P.; Kallmann, H.P. Ac impedance measurements of photo-conductors containing blocking layers analysed by the Maxwell-Wagner theory. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1962, 23, 1067–1078. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, V.; Tagantsev, A. Intrinsic dielectric loss in crystals. Adv. Phys. 1991, 40, 719–767. [CrossRef]

- Setter N, Colla EL. Ferroelectric ceramics: tutorial reviews, theory, processing, and applications. Basel: Birkhäuser. 1993, (p. 127).

- Ashiq, M.N.; Iqbal, M.J.; Najam-Ul-Haq, M.; Gomez, P.H.; Qureshi, A.M. Synthesis, magnetic and dielectric properties of Er–Ni doped Sr-hexaferrite nanomaterials for applications in High density recording media and microwave devices. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 15–19. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).