1. Introduction

It has been widely reported that, despite the decrease over the last two decades of the prevalence of tooth loss, edentulism is still a global prevalent condition with differences among countries, age groups and socioeconomic status [

1]. Consequently, to overcome this problem, during the last three decades, the use of implant-supported oral rehabilitations has become the standard of care dramatically improving individuals chewing function, esthetics and self-reported quality-of-life (PROs) [

2,

3].

From a diagnostic point of view, the implementation of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging prior to dental implant has increased significantly in recent years with documented advantages such as decrease in radiation exposure compared with conventional computed tomography [

4,

5]. However, implant placement might present some clinical challenges, such as the presence of narrow ridges, slim margins and the need of preserving critical anatomical structures (i.e., mandibular nerve) [

6]. In this respect, the use of pre-operative planning including CBCTs do represent a crucial step to minimize complications and maximize proper 3-D implant placement [

7]. From a technical aspect, recent developments have allowed the use of voxel sizes down to tenths of a millimeter and the ability to visualize and measure anatomic structures in all spatial dimensions [

5,

8]. From a descriptive point of view, computer-assisted surgical (CAS) implant placement systems were the first to be introduced. Such systems can be categorized as either static or dynamic [

5,

9]. In the first clinical scenario, CAS systems use drill within templates with embedded sleeves which could be placed on the neighboring side of the surgical site to facilitate the transferring of the position of implant planning [

10,

11]. These templates could be supported by teeth, mucosa, or bone, helping conduct implants in an optimal position [

10,

12]. The reliability of this procedure has been clinically proven [

10,

13,

14,

15]. However, several studies have already shown that different factors could influence the accuracy of static CAS, e.g., lack of direct visual contact with the surgical site, intra-oral positioning, and template fixation [

10,

16,

17]. The Static CAS systems use guides fabricated with computer-aided design (CAD/ CAM) based on 3D scans of the patient [

5,

9,

17]. In contrast, dynamic CAS systems track the patient and surgical instruments and present real-time positional and guidance feedback on a computer display [

5,

16].

To improve these two technologies, the use of dynamic navigation systems was developed based on the “motion-tracking technology” which tracks the position of the surgical site and drill real-time behavior combined to patient’s pre-surgical CBCT [

10,

18,

19,

20]. In addition, during implant placement, tracking cameras are in use to continuously monitor the attached marker on the patient’s jaw and surgical handpiece. This procedure is displayed in real-time on a screen superimposed on implant planning. Therefore, from a clinical perspective, any potential deviation of the implant and drill axis could be controlled and corrected [

10,

21]. Furthermore, the real-time monitoring of the procedure allows the surgeon to modify the virtual planning during the surgery [

10,

15].

Recently, thanks to the developments of new software and hardware for dCAS, the complexity workflow has been reduced, and this has given dental surgeon a larger selection of CAS devices [

5,

9,

16,

17]. While both static and dynamic image navigation are highly accurate, the main advantages of dynamic navigation systems are:

1. possibility to scan, plan and undergo surgery on the same day.

2. planning can be altered during surgery when clinical situations dictate a change.

3. the entire field can be visualized at all times.

4. accuracy can be verified during all surgery time [

22].

Nevertheless, it is clinical experience that dynamic CAIS requires higher training and experience than static CAIS [

23]. In this respect, considering the increasing use of dCAS among oral surgeons, and although previous investigations evaluated several factors in accuracy of implant placement, there is a lack of evidence on the role of the surgeon’s experience in the use of such technology and the surgery accuracy [

23,

24].

To the best authors knowledge, this study is the first cadaver study evaluating the influence of operator’s experience on the accuracy of implant placement using dCAS. The primary aim was to investigate differences in terms of implant placement accuracy between expert and non-expert operators by evaluating discrepancies superimposing pre-operative and post-operative CBCT, measuring linear (mm) and angular (degrees) deviations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This pilot study evaluated the accuracy of implant placement using dCAS, during a practical training on fresh defrozen cephali. The samples were donated by individuals for scientific purposes and an official laboratory permission to work on cadavers was obtained from the Italian competent authority. This study was conducted according to the revised guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and did not require any ethical approval.

For this study, surgical sessions were performed on adult fresh defrozen cephalus, fixed with 10% formalin. Three partial edentulous cadavers with terminal dentition were selected to be treated with conventional implants.

A total of 26 implants (15 NobelReplace Conical Connection 4.3x13mm & 11 NobelActive TiUltra 4.3x13mm, Nobel Biocare) were successfully placed by two surgeons in 3 partially edentulous fresh defrozen cephali.

The operators had different degrees of experience: one (NE) was a senior Oral Surgery resident at University of Turin, with implant dentistry experience more than 5 years, while the second (OE) was a non-experienced oral surgeon (less than 5 years of clinical experience in implant dentistry).

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) absence of macroscopic pathology in the bony regions of the maxilla and mandible; (2) at least 3 residual teeth, required for positioning and stabilization of thermoplastic devices (clip) with 3 radiopaque fiducials (X-Clip, X-Nav Technologies) during CBCT scan and surgical procedures.

2.3. Scanning and Planning Protocol

In this case, considering that fresh defrozen cephali had terminal dentition with >3 stable adjacent teeth and located in an area of the dental arch that did not violate the implant milling, a fiducial-based registration protocol was performed.

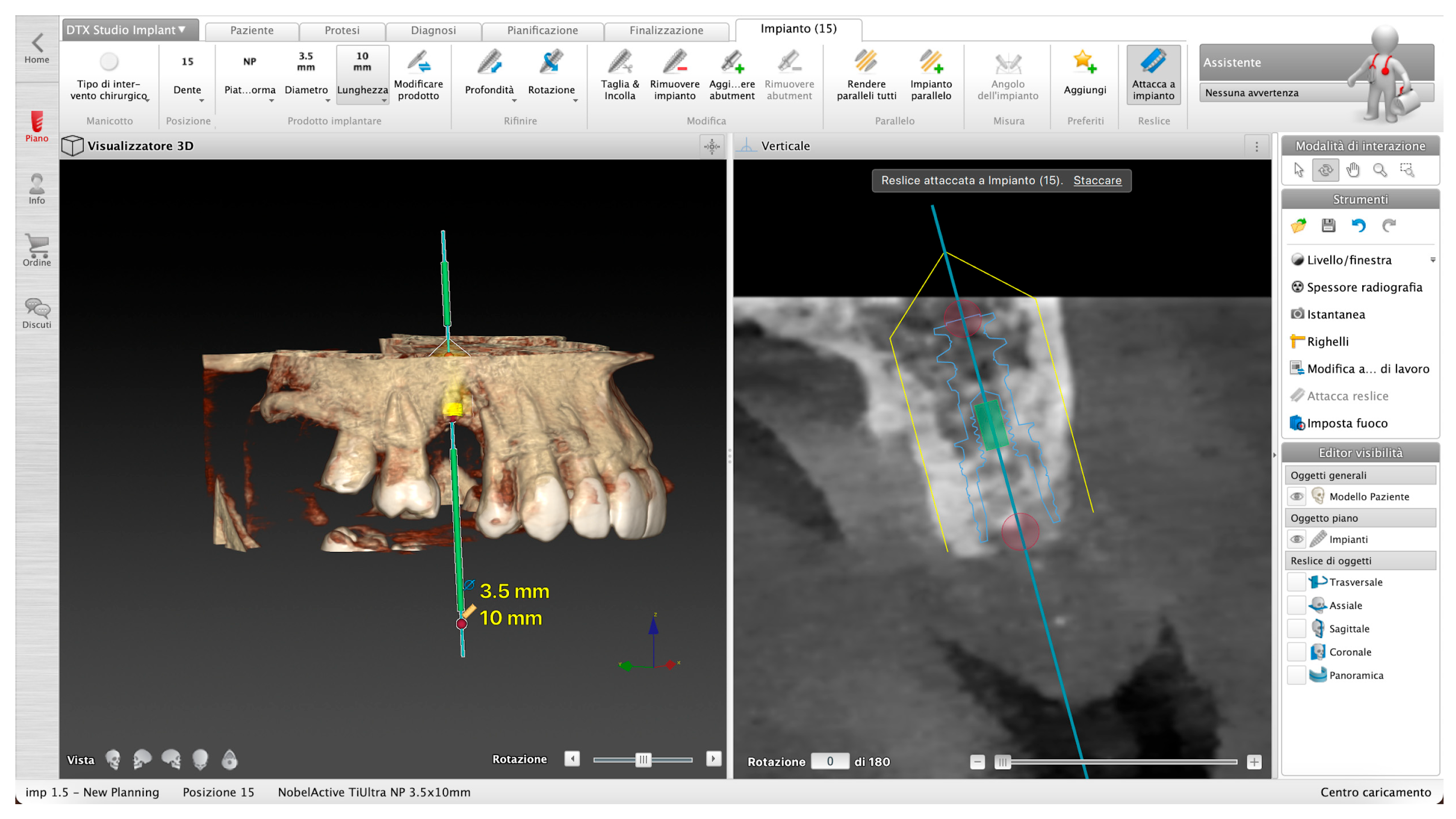

This protocol involves, before the acquisition of the pre-operative CBCT scan, placing a thermoplastic clip with three radiopaque fiducials (X-Clip, X-Nav Technologies) on the remaining teeth of the dental arch involved in the implant surgery (

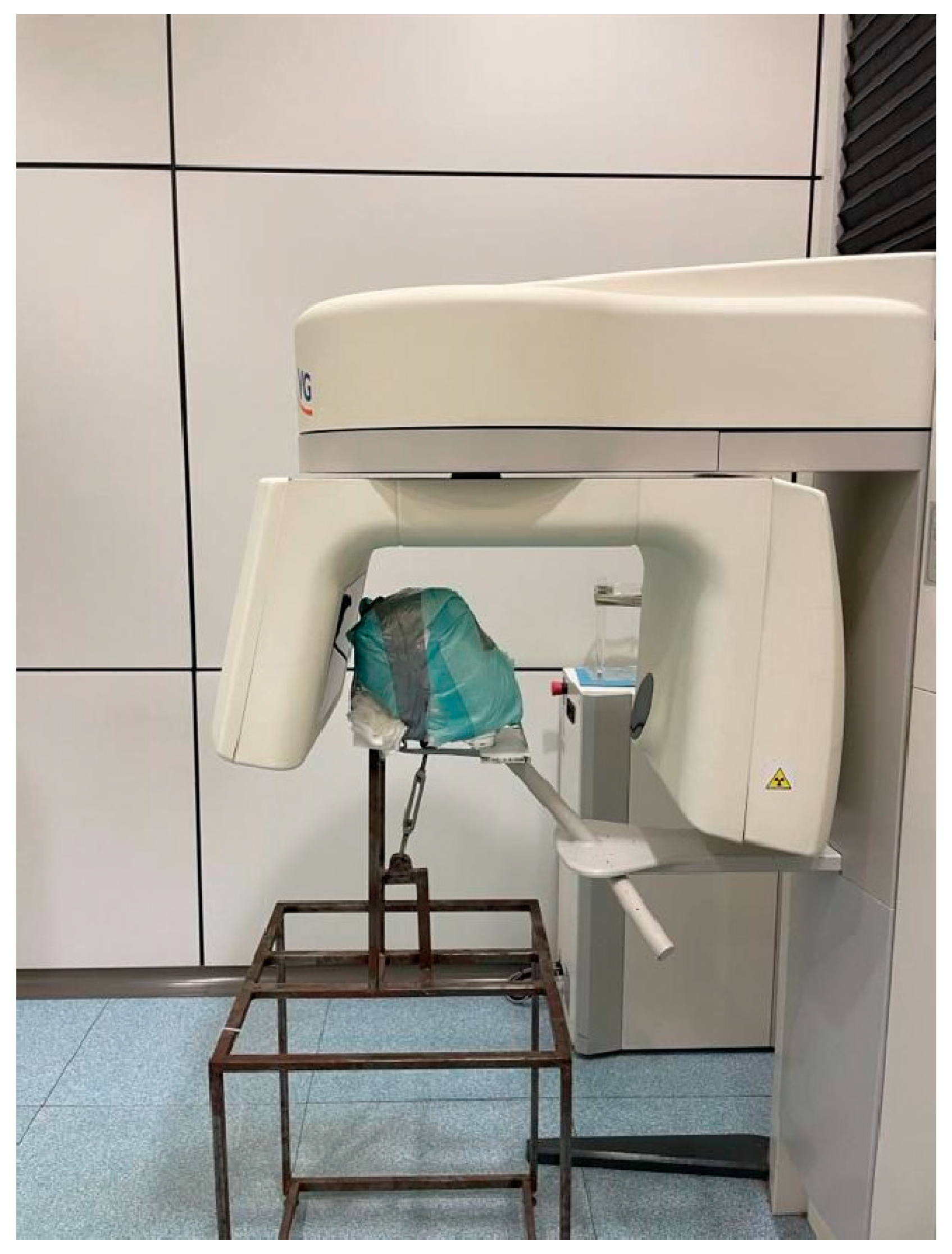

Figure 1). Then, a CBCT scans (NNT - Medical Suite®; NewTom, Imola, Italy) was performed with the following set up: 110 Kv, 1.94 mA, 3.6 seconds, 685.41 DAP (mGy*cm2), 100 x 140 FOV (mm) (

Figure 2).

The digital information (.dicom data set) was uploaded to the dynamic navigation planning system (DTX StudioTM).

This software allowed to define the arch, nerve mapping, and implant planning through MPR (multiplanar reformation), used to plan ideal implant placement which was identical to the implant placed in cadavers (diameter, apical diameter, length, shape), thanks to an implant library contained on DTX.

Figure 3.

Example of implant placement planning.

Figure 3.

Example of implant placement planning.

Files from intraoral scanners were superimposed on DICOM data set and the combined images allowed to plan, with the osseous, dental, and soft tissue structures visible along with the patient’s occlusion, in order to plan a prosthetic-guided implant placement.

When starting the planning, a panoramic curve for the arch is drawn on the axial plane of the patient’s scan, and the inferior alveolar nerve also can be identified and reference on the mandible.

Once the surgical plan was defined, the dataset was exported by DTX and imported as .stl file into the DN software.

A total of 26 implants were successfully placed by the two operators. At the end of the surgical interventions, a post-operative CBCT scan was taken to perform the accuracy evaluation.

2.4. Calibration Sessions and Surgical Procedures

Each surgeon performed surgical session after five days of training which included training on manikins, mentoring with over-the-shoulder observation and hands-on mentoring. No surgery was performed prior to assurance of high level of agreement between the two operators.

Before the initiation of this study, all practitioners received standard hands-on training for virtual planning with implant treatment planning software (DTX StudioTM Implant 3.4.3.3, Nobel Biocare AG) and surgical procedure simulation with the navigation system to achieve minimal proficiency.

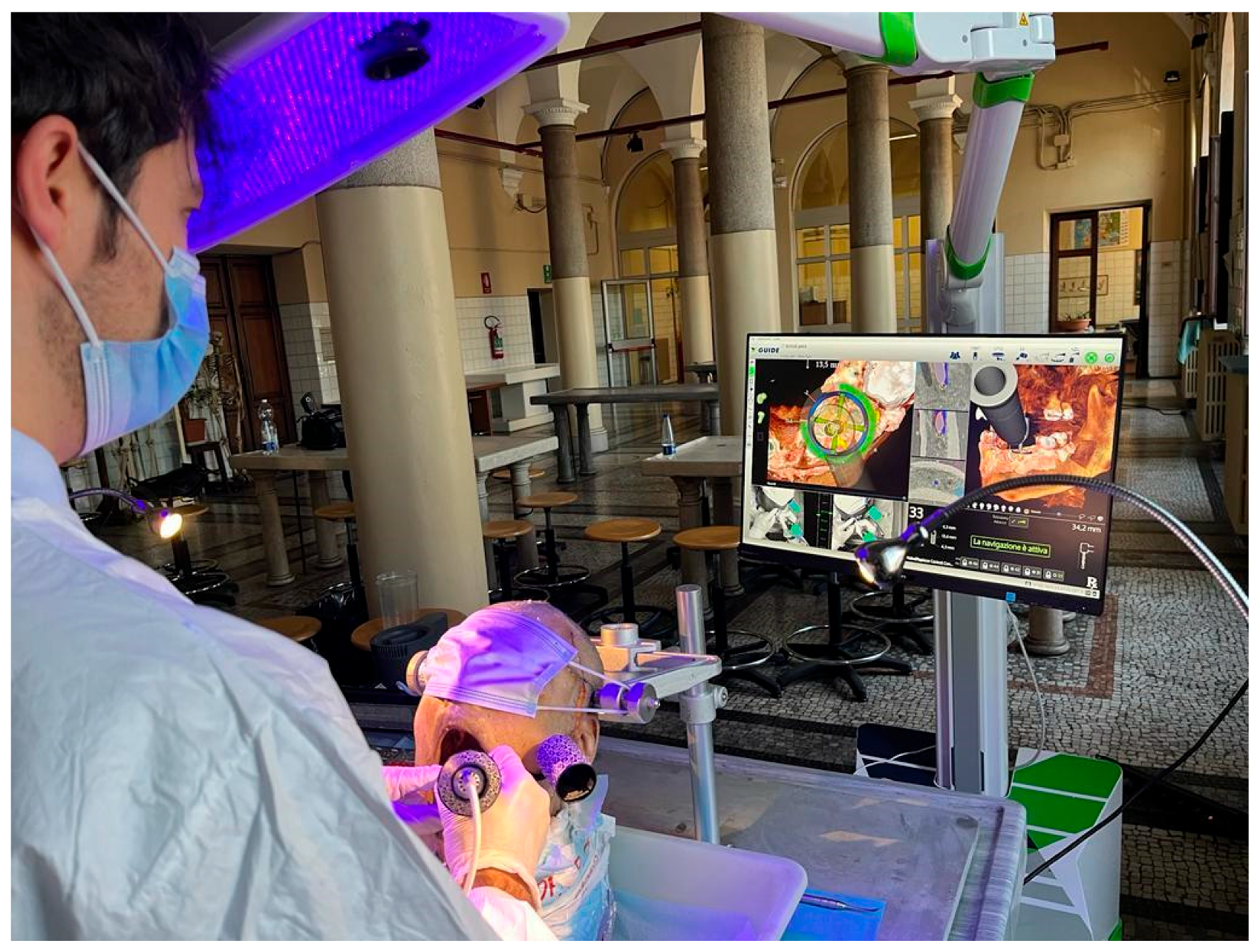

All implants were positioned using a dynamic navigation surgery system (X-Guide, X-Nav Technologies). Depending on the implant site characteristics, conventional (with flap) or flapless surgical procedure was performed. Standardized implants were placed in all cases (15 NobelReplace Conical Connection 4.3x13mm in mandible & 11 NobelActive TiUltra 4.3x13mm in maxilla, Nobel Biocare).

Prior each surgical procedure, the clip was mounted on the teeth in the same position as CBCT scanning and attached fiducial markers and the cylinder of the attached patient tracking matrix, extraorally oriented. Likewise, the handpiece, patient tracking array and drills were calibrated. All these instruments must be within the line of sight of the overhead stereo cameras to be tracked on the monitor.

Calibration of the surgical handpiece was performed before surgical acts. The handpiece calibration relates the geometry of the handpiece tracking array to drill axis and CBCT fiducials, hence providing a link between the preoperative planning coordinate system and a trackable coordinate system.

After calibration, the operators performed the surgery. Real-time checks were performed through patient's CBCT anatomy, and the implant coordinates were pre-planned to guarantee accuracy of tracking, all using the navigation screen on the monitor (

Figure 4). If necessary, then changes in the plan were made during surgical acts, including implant size, length, width, shape, and positioning to achieve an accurate implant position.

The dynamic reference frames calibration relates the geometry of the patient-tracking array to the CT fiducials, hence providing a link between the preoperative planning coordinate system and a trackable coordinate system. The stereo-tracking system simultaneously triangulated each tracking array to determine their precise position and orientation in a common coordinate frame. In combination with the calibrations, this real-time link allowed the drill’s body and tip to be related.

The patient dynamic reference frames included the clip with the connected patient-tracking cylinder. It was placed onto the teeth in the same location as for CBCT acquisition. The tracking software algorithm triangulated the 2 arrays continuously. Two live video windows allowed the surgical team to get virtual feedback from the navigation system to visualize site preparation and monitor the quality of tracking in the surgical field volume.

2.5. Accuracy Analysis

The evaluated outcomes variables have been previously described [

5]. More into details, after surgery, a post-operative CBCT was performed with the same FOV and resolution of the pre-operative CBCT (110 Kv, 1.94 mA, 3.6 seconds, 685.41 DAP (mGy*cm2), 100 x 140 FOV (mm)), to compare deviations between planned and placed implants.

Accuracy of implant placement of two operators was assessed by superimposing the preoperative virtual surgical plan and the postoperative CBCT scan and quantifying deviations of the delivered implant from the planned position and orientation. The same methodology proposed and validated by Block MS. et al and Jorba-García A. et al was implemented [

23,

25].

The DICOM images of the post-operative CT were uploaded in a dedicated software.

To obtain very precise results, implants were planned and superimposed on placed implants to perfectly replicate the morphology of implants (centroid apex and shoulder, and their spatial coordinates).

The accuracy was assessed overlapping the postoperative CT scan (with placed implants) with the pre-operative one (with planned implants). The accuracy evaluation involved angular and linear (coronal, apical and depth) deviations. The DICOM images of the post-operative CT were uploaded in a dedicated software (NobelGuide validation study tool in DTX Studio Implant 3.6). A segmentation based on tissue density was carried out to separate implants from the surrounding bone.

The STL files of the maxillary and mandible bone with the planned implants obtained from the pre-operative CBCT were uploaded into the software. The superimposition of the pre-operative and post-operative CT images was achieved by using the best-fit alignment tool. The planned and inserted implants were considered as cones with a base and a centroid apex and shoulder and their spatial coordinates (the center of the base and the apex) were registered by using DTX and were exported in an Excel sheet to calculate coronal, apical, depth and angular deviations.

A mathematical algorithm was used on the presurgical case with the plan, the postsurgical case with the virtual implant overlaid on the actual implant, and the meshed CBCT scans to calculate angular and positional deviations between the planned and actual implant positions in 3 dimensions.

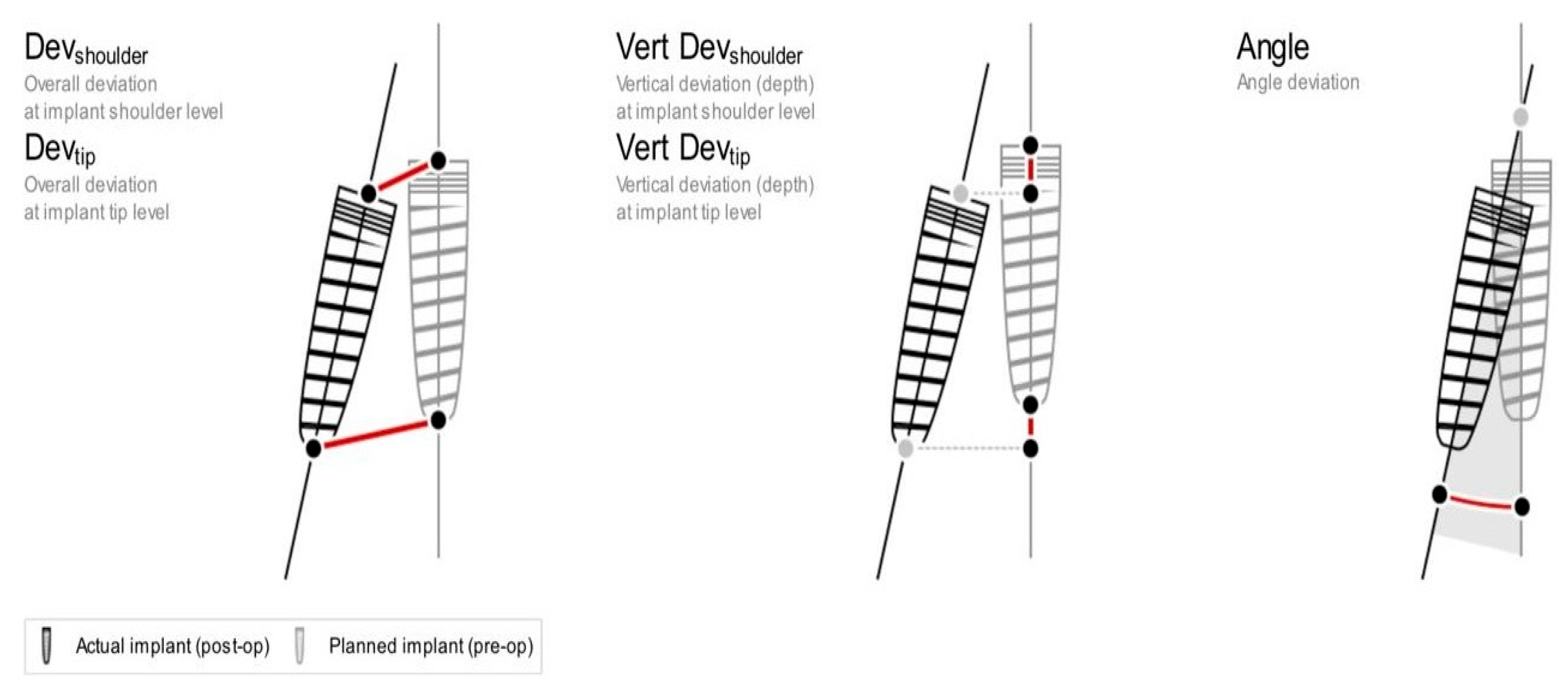

The following deviations (mean +/- standard deviation) from the virtual plan were calculated and listed in

Figure 5:

Mesio-distal (M/D) angular deviation: mesiodistal angle between vertical axes of the planned and placed implants.

Bucco-lingual (B/L) angular deviation: buccolingual angle between vertical axes of the planned and placed implants.

Deviation Shoulder Point (mm): a 2-dimensional distance between the shoulder centroids of the planned and placed implants.

Deviation Tip Point (mm): a 2-dimensional distance between the apex centroids of the planned and placed implants.

Dept deviation Shoulder Point (mm): depth distance between the shoulder centroids of the planned and placed implants on the z-axis.

Depth deviation Tip Point (mm): depth distance between the apex centroids of the planned and placed implants on the z-axis.

For each parameter, the mean of two measurements performed by two blinded and previously calibrated operators (Cohen's kappa coefficient = 0.72) was calculated and used for statistical analysis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

To guarantee unbiased statistical analysis, the operator (experienced or novice) variables were coded, and a blinded researcher (OCF) analyzed the data using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software. A database was created with the recorded measures (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and a descriptive statistics analysis was used, calculating the median and the mean and the standard deviation (SD) for each variable. For bivariable categoric variables, descriptive analysis was performed through absolute and relative frequency tables.

The sample was divided into six variables (Dept Deviation Tip Point; Dept Deviation Shoulder Point; Deviation Tip Point; Deviation Shoulder Point; B/L angular deviation; M/D angular deviation) to investigate the potential effect using independent samples t-tests on accuracy of implant placement for each outcome value. A p-value of <0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance.

The possible relationship between variables was analyzed through bivariate analysis. To examine the effect of different operators (experienced and unexperienced) and the interaction between variables studied, a two-independent factors analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) was performed in G*Power (Heinrich- Heine Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany), such as made by Jorba-Garcià et al [

23].

3. Results

A total of twenty-six implants (15 NobelReplace Conical Connection 4.3x13mm in mandible & 11 NobelActive TiUltra 4.3x13mm in maxilla, Nobel Biocare) were placed and analyzed in three fresh defrozen cephali, without deviations from the original digital surgical planning. All specimens were available for analysis since no intra-surgical complications were recorded.

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the deviation from virtual plan of main outcomes for each surgeon, in terms of mean and standard deviation (SD) of all placed implants and apex linear (shoulder, apex and depth) and angular deviations (M/D, B/L) stratified according to the analyzed variables.

Hence, analyzing the results regarding the role of the surgeon’s experience, expert and non-expert surgeons showed an analogous accuracy during implant placement for each variable studied, so deviations were negligible (p>0.05) in all outcomes. All these data can be observed in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the cadaver pilot study investigating the influence of surgeons’ experience on the accuracy of implant placement using dCAS. The goal of the present study was to assess the potential differences between operators’ experience and the definite outcomes: implant placement accuracy.

Since the introduction of three-dimensional imaging and visualization software before implant placement in the 1990s and the further introduction of dynamic navigation in the 2000s, a great deal of recent research has been conducted on computer-assisted guidance extensively in the past two decades to create the most accurate device for prosthetic-guided implant placement.

In this context, the goal of the present study was to investigate the association between surgeons’ experience and implant placement accuracy. The findings revealed encouraging results concerning the role of surgeons’ experience. Specifically, unexperienced surgeons showed higher performance than those with more experience in terms of linear and angular deviations during navigated implant placement, but no significant differences were found for any variables evaluated between the two operators (p>0.05).

These results may seem counterintuitive, as one would typically expect higher accuracy from experienced surgeons because, with this surgical system, they might further improve their implant placement accuracy. However, a possible reason could be that unexperienced surgeons adhered more strictly to the dynamic navigation system’s guidance because of their short surgical experience, and resulting in similar precision. In contrast, experienced surgeons may have relied more on their prior experience, which could have led to slight deviations from the system guidance.

In light of the obtained descriptive results of this study, the outcomes aimed to evaluate the depth accuracy require a more detailed analysis as shown by the overall mean deviation at tip depth (0.69 mm - SD 0.39) and shoulder depth (0.73 mm - SD 0.46). It’s a large discrepancy from the planning that’s unacceptable in critical anatomical areas where the inferior alveolar nerve is at risk.

Consequently, a risk of implant deviation still exists with the navigation system due to the errors that might be generated during the workflow steps of image acquisition, tracking clip stability, registration and calibration, and errors when overlaying the two CBCT scans as reported by priors’ study [

9,

22,

23,

27,

28,

30].

Thus, in the authors’ opinion, such as for other surgical approaches a 2 mm safety margin should be applied to all important anatomical structures in the presurgical planning [

23]. From a clinical perspective, it should be recall that the application of such margin might raise some questions on the overall reliability of navigation systems. In other words, the clinical question “Does this tool help implant placement in complex cases?” remains still open.

When comparing the presented results with those available in the literature, it should be underlined that an in-vitro study by Jorba-Garcià et al. revealed negligible differences between two operators (p>0.05) using dynamic navigation system. Consequently, the outcomes evaluated in the present cadaver study are in accordance with this paper [

23]. Similarly, Pellegrino et al. showed an analogous implant placement accuracy between 4 operators with different grades of implant surgery experience, resulting in not statistically significant differences in the majority of the evaluated outcomes in terms of two/three-dimensional deviations [

29].

Furthermore, Wang et al. investigated three different approaches (i.e., free hand, sCAS and dCAS) and showed that experienced vs. non-experienced had an analogous accuracy and differences between operators were not statistically significant (p> 0.05) [

30,

31].

Finally, Sun et al. and Wu et al. showed that the surgeons’ experience level did not influence implant placement accuracy with dCAS [

32,

33].

All cited studies revealed partially lower linear and angular deviations than the present study, but such results should be interpreted with more caution, because the data concerning the accuracy of dCAS are obtained during in-vitro trainings (i.e., using artificial models), which can lead to higher accuracy in comparison to real clinical scenarios, such as fresh defrozen cephalus [

9,

23,

34,

35].

In addition, the direct comparison with the pre-clinical scenario with respect to the type of implant placement (i.e., flapless vs. open surgery) might be an important confounding factor requiring further investigation.

Although the dynamic navigation system offers excellent accuracy, its application is limited in clinical practice mainly because of the required learning curve, the risk of inaccurate implant placement, as mentioned above, due to system error, and the high cost of the device. It represents a large economic investment for oral surgeons which includes the cost per single case of fiducial clips, markers, and plates [

23,

30,

36,

37].

Despite the limitations, the present results can be considered promising positive preliminary results acting as a starting point for future clinical research with a larger sample size. Moreover, an important aspect that should be investigated is a bivariate analysis considering the implant planning (i.e., the gold-standard) and each operator's effective implant placement.

5. Conclusions

The present findings suggest that dynamic computer-assisted surgical implant placement systems could be a viable and safe technique for implant surgery by any operator, independently of surgical experience.

Based on the obtained results, this system might offer additional clinical benefits to an un- experienced operator, despite the required learning curve and the cost originated by the initial investment. However, further studies with larger sample size and different settings will be needed to confirm and support these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P. and C.V.; methodology, F.P., C.V. and U.G.; formal analysis, C.V and A.R.; investigation, F.P, C.V., U.G.; resources, F.P.; data curation, C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P, C.V., U.G. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, C.V., A.C. and A.R..; visualization, F.P., A.C., U.G and B.L.; supervision, A.R.; project administration, F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the revised guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available after authors’ consultations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the company Nobel Biocare for providing the materials for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Borg-Bartolo, R et al. “Global prevalence of edentulism and dental caries in middle-aged and elderly persons: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of dentistry vol. 127 (2022): 104335. [CrossRef]

- Duong, Ho-Yan et al. “Oral health-related quality of life of patients rehabilitated with fixed and removable implant-supported dental prostheses.” Periodontology 2000 vol. 88,1 (2022): 201-237. [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, Martin et al. “Group 4 ITI Consensus Report: Patient benefits following implant treatment in partially and fully edentulous patients.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 34 Suppl 26 (2023): 257-265. [CrossRef]

- Harris, David et al. “E.A.O. guidelines for the use of diagnostic imaging in implant dentistry 2011. A consensus workshop organized by the European Association for Osseointegration at the Medical University of Warsaw.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 23,11 (2012): 1243-53. [CrossRef]

- Emery, Robert W et al. “Accuracy of Dynamic Navigation for Dental Implant Placement-Model-Based Evaluation.” The Journal of oral implantology vol. 42,5 (2016): 399-405. [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, Bjarni E et al. “Comparison of survival and complication rates of tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) and implant-supported FDPs and single crowns (SCs).” Clinical oral implants research vol. 18 Suppl 3 (2007): 97-113. [CrossRef]

- Saini, Ravinder S et al. “Impact of 3D imaging techniques and virtual patients on the accuracy of planning and surgical placement of dental implants: A systematic review.” Digital health vol. 10 20552076241253550. 7 May. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Widmann, Gerlig et al. “Comparison of the accuracy of invasive and noninvasive registration methods for image-guided oral implant surgery.” The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants vol. 25,3 (2010): 491-8.

- Jung, Ronald E et al. “Computer technology applications in surgical implant dentistry: a systematic review.” The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants vol. 24 Suppl (2009): 92-109.

- Taheri Otaghsara, Seyedeh Sahar et al. “Accuracy of dental implant placement using static versus dynamic computer-assisted implant surgery: An in vitro study.” Journal of dentistry vol. 132 (2023): 104487. [CrossRef]

- Ruppin, Jörg et al. “Evaluation of the accuracy of three different computer-aided surgery systems in dental implantology: optical tracking vs. stereolithographic splint systems.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 19,7 (2008): 709-16. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Miao et al. “Comparison of the accuracy of dental implant placement using static and dynamic computer-assisted systems: an in vitro study.” Journal of stomatology, oral and maxillofacial surgery vol. 122,4 (2021): 343-348. [CrossRef]

- Tahmaseb, Ali et al. “The accuracy of static computer-aided implant surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 29 Suppl 16 (2018): 416-435. [CrossRef]

- Al Yafi, Firas et al. “Is Digital Guided Implant Surgery Accurate and Reliable?.” Dental clinics of North America vol. 63,3 (2019): 381-397. [CrossRef]

- Gargallo-Albiol, Jordi et al. “Advantages and disadvantages of implant navigation surgery. A systematic review.” Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft vol. 225 (2019): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Brief, Jakob et al. “Accuracy of image-guided implantology.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 16,4 (2005): 495-501. [CrossRef]

- Tahmaseb, Ali et al. “Computer technology applications in surgical implant dentistry: a systematic review.” The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants vol. 29 Suppl (2014): 25-42. [CrossRef]

- Vercruyssen, Marjolein et al. “Different techniques of static/dynamic guided implant surgery: modalities and indications.” Periodontology 2000 vol. 66,1 (2014): 214-27. [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla Guzmán, Alfonso et al. “Accuracy of Computer-Aided Dynamic Navigation Compared to Computer-Aided Static Navigation for Dental Implant Placement: An In Vitro Study.” Journal of clinical medicine vol. 8,12 2123. 2 Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Du, Yu et al. “Quantification of image artifacts from navigation markers in dynamic guided implant surgery and the effect on registration performance in different clinical scenarios.” The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants vol. 34,3 (2019): 726–736. [CrossRef]

- Kaewsiri, Dechawat et al. “The accuracy of static vs. dynamic computer-assisted implant surgery in single tooth space: A randomized controlled trial.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 30,6 (2019): 505-514. [CrossRef]

- Somogyi-Ganss Eszter. Evaluation of the Accuracy of NaviDent, a Novel Dynamic Computer-Guided Navigation System for Placing Dental Implants [master’s thesis]. Toronto, Canada: Graduate Department of Prosthodontics, University of Toronto; 2013.

- Jorba-García, A et al. “Accuracy and the role of experience in dynamic computer guided dental implant surgery: An in-vitro study.” Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal vol. 24,1 e76-e83. 1 Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, Alessandro et al. “Accuracy of navigation guided implant surgery for immediate loading complete arch restorations: Prospective clinical trial.” Clinical implant dentistry and related research vol. 26,5 (2024): 954-971. [CrossRef]

- Block, Michael S, and Robert W Emery. “Static or Dynamic Navigation for Implant Placement-Choosing the Method of Guidance.” Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons vol. 74,2 (2016): 269-77. [CrossRef]

- Somogyi-Ganss, Eszter et al. “Accuracy of a novel prototype dynamic computer-assisted surgery system.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 26,8 (2015): 882-890. [CrossRef]

- Elian, Nicolas et al. “Precision of flapless implant placement using real-time surgical navigation: a case series.” The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants vol. 23,6 (2008): 1123-7.

- Gaggl, Alexander, and Günter Schultes. “Assessment of accuracy of navigated implant placement in the maxilla.” The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants vol. 17,2 (2002): 263-70.

- Pellegrino, Gerardo et al. “Dynamic Navigation in Dental Implantology: The Influence of Surgical Experience on Implant Placement Accuracy and Operating Time. An in Vitro Study.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 17,6 2153. 24 Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaotong et al. “Influence of experience on dental implant placement: an in vitro comparison of freehand, static guided and dynamic navigation approaches.” International journal of implant dentistry vol. 8,1 42. 10 Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaotong et al. “Performance of novice versus experienced surgeons for dental implant placement with freehand, static guided and dynamic navigation approaches.” Scientific reports vol. 13,1 2598. 14 Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Ting-Mao et al. “The influence of dental experience on a dental implant navigation system.” BMC oral health vol. 19,1 222. 17 Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Dong et al. “Accuracy of dynamic navigation compared to static surgical guide for dental implant placement.” International journal of implant dentistry vol. 6,1 78. 24 Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jorba-García, Adrià et al. “Accuracy assessment of dynamic computer-aided implant placement: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical oral investigations vol. 25,5 (2021): 2479-2494. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Shi-Min et al. “Accuracy of dynamic navigation in implant surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical oral implants research vol. 32,4 (2021): 383-393. [CrossRef]

- Spille, Johannes et al. “Comparison of implant placement accuracy in two different preoperative digital workflows: navigated vs. pilot-drill-guided surgery.” International journal of implant dentistry vol. 7,1 45. 30 Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Panchal, Neeraj et al. “Dynamic Navigation for Dental Implant Surgery.” Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America vol. 31,4 (2019): 539-547. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).