1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social interactions and communication and the presence of repetitive, restrictive, and stereotyped patterns of interests and behaviors. Individuals with ASD commonly struggle with social cognition, particularly Theory of Mind (ToM), also referred to as mentalizing (Baron-Cohen, 1997, 2000), known as the capacity, to infer the mental states of others (Wimmer and Perner, 1983). While earlier studies indicated that individuals with ASD often struggle with ToM tasks (Baron-Cohen, 1997), later research has challenged these claims, showing that many individuals with ASD can complete advanced ToM tasks (White et al., 2009; Spek et al., 2010; Scheeren et al., 2013). Instead, emerging evidence suggests that individuals with ASD may struggle with implicit mentalizing, as assessed through non-verbal methods (e.g., reaction time or eye-tracking) (Senju, 2013; Deschrijver et al., 2016; Nijhof et al., 2017), which could explain their social and communicative challenges in daily life.

Despite ongoing controversy, previous studies have highlighted distinctions between implicit and explicit ToM. Implicit ToM is believed to operate unconsciously and emerge early in life, while explicit mentalizing is more deliberate and flexible (Apperly and Butterfill, 2009). Alternatively, some view ToM as a unified system that functions both automatically and with executive control (Carruthers, 2017). Neuroimaging and noninvasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques can provide us with valuable information about neural correlates and causes of brain-behavior relationships respectively (Polanía et al., 2018; Salehinejad et al., 2021a) enhancing our understanding of the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying ToM. Studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have mainly revealed a network of brain regions activated during explicit ToM tasks, including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), superior temporal sulcus (STS), and temporoparietal junction (TPJ) (Sommer et al., 2007; Van Overwalle, 2009; Schurz et al., 2014). In contrast, findings on implicit ToM are sparse and mixed; some studies report no activation of the right TPJ during implicit ToM (Spiers and Maguire, 2006; Schneider et al., 2014), while others have noted increased right TPJ activation for false beliefs compared to true beliefs during the belief formation phase (Bardi et al., 2017b; Boccadoro et al., 2019). In ASD, functional underconnectivity is linked to difficulties during ToM tasks (Deschrijver and Palmer, 2020; Arioli et al., 2023) showing that the brain's social network has altered activation. Furthermore, fMRI studies have shown reduced activity in the rTPJ in both explicit (Spengler et al., 2009; Lombardo et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2022) and implicit (White et al., 2014; Nijhof et al., 2018) ToM tasks.

NIBS offers a safe (Salehinejad and Siniatchkin, 2024) method for studying and modifying human cognition and brain functions (Polanía et al., 2018), and unlike neuroimaging studies provides insights into the causal role of brain regions involved in behavior. Previous NIBS studies have shown contribution of rTPJ in ToM in healthy individuals (Ahmad et al., 2021; Nejati et al., 2024). In ASD, previous NIBS studies have mostly used transcranial magnetic and electrical stimulation with promising results on cognitive and behavioral functioning (Salehinejad et al., 2022a; Zemestani et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2023). Theta-burst stimulation (TBS) is a form of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) that uses high-frequency bursts of magnetic pulses to modulate brain activity (Huang et al., 2005a). Its shorter duration compared to rTMS is advantageous for individuals with ASD, as they may experience discomfort or sensory overload during prolonged sessions.

Most TBS studies on ASD have focused on cognitive and behavioral functioning by targeting the posterior STS and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and findings have been inconsistent (Liu et al., 2020; Ni et al., 2022). Very few NIBS studies investigated the role of rTPJ in ToM in ASD (Salehinejad et al., 2021c) and no NIBS study investigated the impact of brain modulation on implicit ToM. Accordingly, in this randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled crossover study, we investigated the effects of excitatory and inhibitory TBS on the rTPJ to determine (1) its causal role in enhancing implicit mentalizing capacity in individuals with ASD, and (2) its involvement in overlap or mismatch between own mental states (Bardi et al., 2017a) and those of others, as suggested by prior studies (Deschrijver and Palmer, 2020). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of both iTBS and cTBS on implicit mentalizing in ASD.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

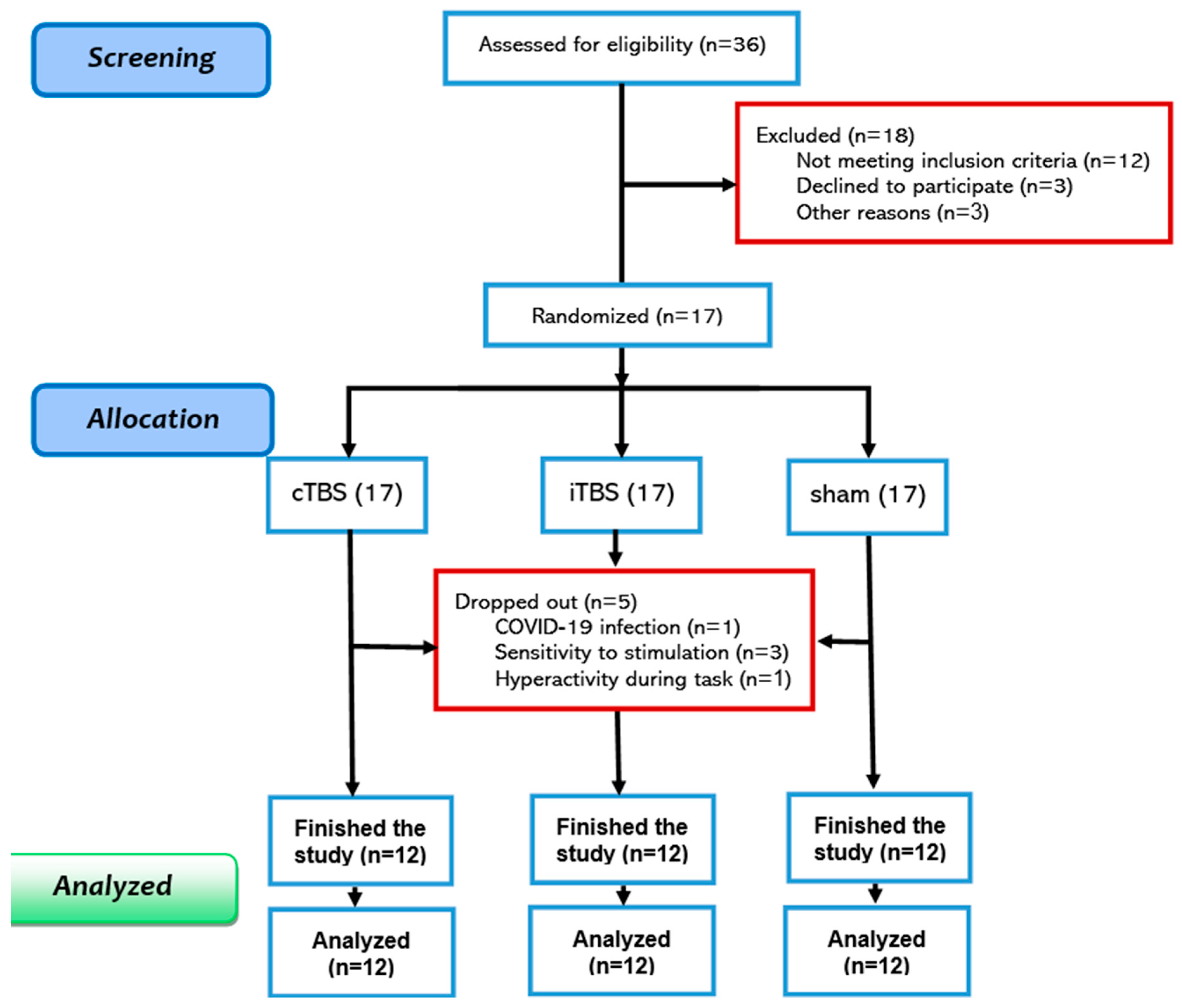

Seventeen autistic boys (mean age = 13.84±3.32) were recruited from the Atieh Clinical Neuroscience Center. The inclusion criteria were a DSM-5-based diagnosis of high-functioning autism and a 70≥ intelligent quotient, assessed by the short form of the Stanford Binet test. Exclusion criteria included an intellectual disability, prior theta-burst treatment, severe head injury, metal implants in the head, a history of epilepsy in the participant or their first-degree relatives, and any neurological or psychiatric conditions beyond common autism comorbidities such as ADHD, depression, anxiety, and obsession. One participant was excluded due to attention problems, three due to hypersensitive reactions, and one due to COVID-19 infection. Accordingly, twelve participants were included in the final analysis (

Figure 1, see

Table 1 for demographics). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran (Ethics code: IR.UT.PSYEDU.REC.1400.013). Participants’ parents provided written informed consent before participation.

2.2. Implicit ToM Task

We used the Buzz-lightyear task (Kovács et al., 2010) to assess the implicit mentalizing aspect of ToM. This task has been utilized in several studies involving autistic or healthy individuals (Silvanto and Pascual-Leone, 2008; Oberman et al., 2014; McCormick et al., 2020; Zhang and Zhang, 2022). In summary, participants watch short video clips (13,850 ms; 720x420 pixels) showing Buzz Lightyear placing a ball on a table. The ball spins and moves behind a green occluder, either staying there or rotating past it. This belief formation phase helps form beliefs about the ball's presence for both the participant (P) and the agent (A). The agent then leaves the scene and afterward the ball either stayes in its place, resulting in the subject’s belief remaining unchanged and coinciding with the agent’s belief, or changes its location, leading to a discrepancy in the subject’s and agent’s beliefs. This scenario can result in four belief combinations: (1) both participant and the agent believe the ball was present (P^+ A^+), (2) both believe it was absent (P^- A^-), (3) the participant believes it was present, but the agent thinks it was absent (P^+ A^-), and (4) the participant believes it was absent while the agent believes it was present (P^- A^+). The mentalizing index (MI) is calculated as the reaction time difference between P^- A^- and P^- A^+, with a smaller difference indicating greater implicit mentalizing. The egocentric bias (EB) reflects the difference between P^- and P^+, showing how much participants favored their perspective. Participants were not asked about these beliefs; they focused on a visual detection task regarding the ball.

In this study and in half of the trials, a ball was behind the occluder (

) and the subject had to press the correct button (B) as fast as possible. In the other half, the ball was absent (

) and the subject should not respond; therefore, there were eight possible scenarios in the movies, which resulted from the combination of the participant’s belief states about the ball’s presence (

or

), the agent’s belief states (

or

), and the true outcome states of the ball’s presence (

or

). In this study, only the

States that required the subject’s reaction were analyzed, as the dependent variables of the design (implicit mentalizing and egocentric bias) were based on the subjects’ reaction times. The mentalizing index was calculated as the average reaction time difference between the

and

conditions, which was defined mathematically as

. This index reflects implicit mentalizing by focusing on scenarios where only the agent's expectations vary while the participants remain constant (not expecting the ball). Faster RTs in this condition suggest an implicit consideration of the agent's perspective, aligning with established mentalizing theories that emphasize understanding others' mental states—an egocentric bias index was also calculated as the average reaction time difference between

and

conditions, as was defined mathematically as

. The video clips used in the task were received from task designer 15, and the experimental paradigm was implemented using the Psychophysics Toolbox extension in MATLAB 2019a (Jannati et al., 2020; Jannati et al., 2021). For details, see the

Supplementary Materials and

Figure S1.

2.3. TBS

TBS was administered using a Magventure device (Denmark) with a butterfly coil positioned at the CP6 site according to the EEG-10-10 system to target the rTPJ region, commonly studied in TMS research on autism (Kirkovski et al., 2022). The coil was placed tangentially on the skin with the handle angled downwards at 45 degrees to the brain's central sulcus midline. For sham stimulation, the coil was rotated 90 degrees from the target to minimize brain stimulation (Lisanby et al., 2001). The intensity of the iTBS was set to 80% of each subject’s active motor threshold (AMT) during active sessions, while it was reduced to 50% of the AMT during the sham stimulation. The AMT was determined for each subject during a submaximal voluntary contraction of the left thumb. The stimulation intensity gradually increased until a measurable muscle contraction was observed. This procedure was repeated several times to ensure consistency of the results for each subject. During TBS, 50-Hz TMS delivers three bursts continuously for 40 seconds (cTBS) or intermittently (iTBS) every 8 seconds, with a 2-second interval, for 180 seconds. Studies have shown that cTBS and iTBS applied to the motor cortex can suppress or facilitate cortical excitability for approximately 20-40 minutes in neurotypical individuals (Huang et al., 2005b). During sham stimulation, the coil was angled 90 degrees from the target area to deliver minimal brain stimulation (Lisanby et al., 2001), a recognized and valid condition commonly used in double-blind or single-blind, sham-controlled randomized clinical trials in major psychiatric disorders (Lefaucheur et al., 2020). We also calculated the electric field (EF) induced by our TBS protocol based on 10/20 EEG system versus employing MRI-guided navigation based on induced EF variations (see

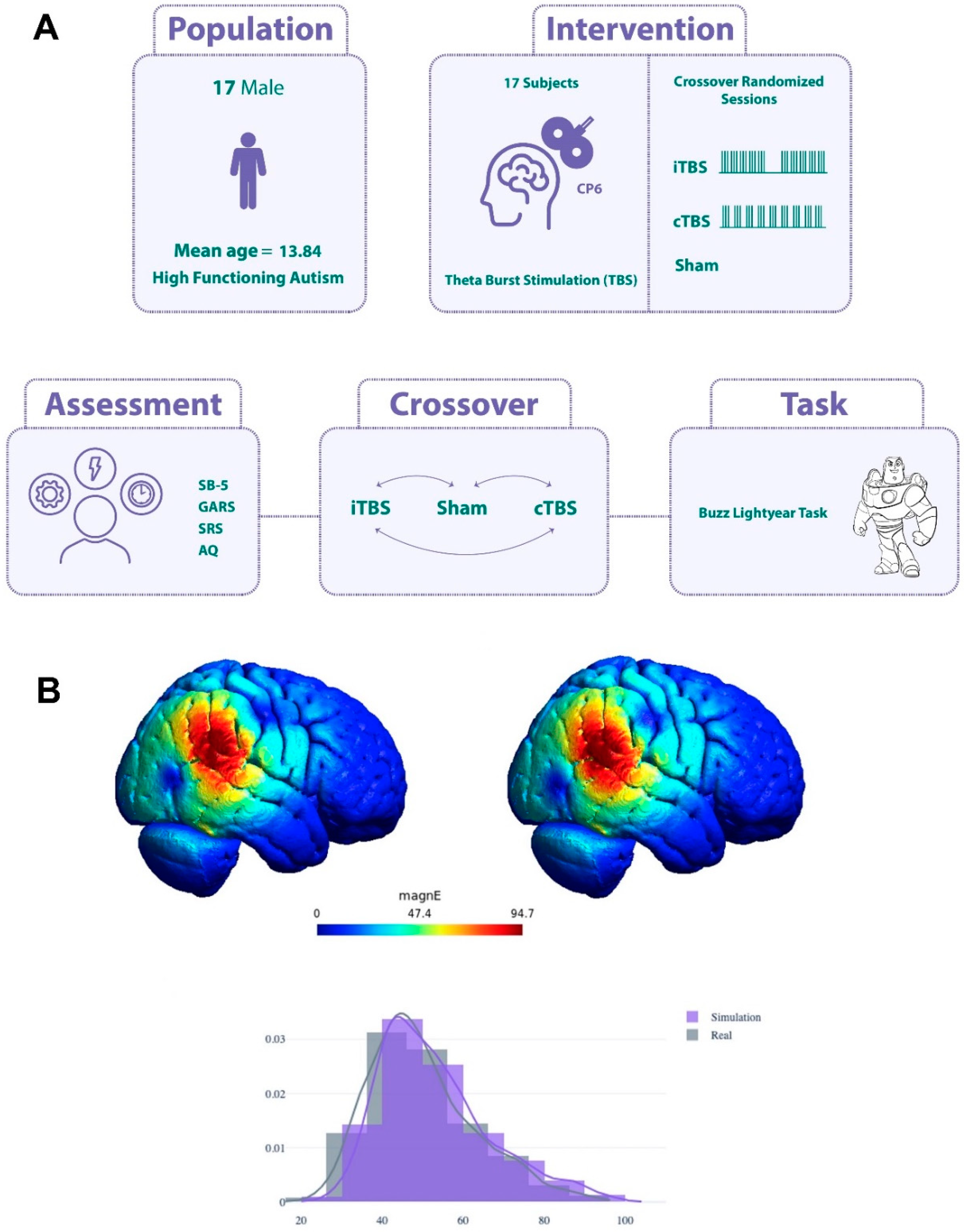

Figure 2B). To calculate the electric field (EF) induced by TBS, we used the SimNIBS 4 (Thielscher et al., 2015) package. The head model used for simulation is based on the NIHPD atlas (Fonov et al., 2011) which consists of average brain volumes in 324 children aged 4.5 to 18.5 years. We also briefly highlighted the potential differences between selecting CP6 as a stimulation site versus employing MRI-guided navigation based on induced EF variations.

2.4. Procedure

Prior to the experimental procedures, participants underwent a test session to determine their eligibility for the study. During this session, a child clinical psychologist specializing in autism re-evaluated the inclusion of participants and determined their AMT. Any indication of sensory hypersensitivity would lead to the exclusion of subjects. In addition, participants completed the short form of the Stanford Binet (SB-5) test and Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) scale while the psychologist administered the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS-2) and the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS-2) questionnaires to the parents. Following meeting the inclusion criteria, participants randomly underwent theta-burst stimulation sessions, including sham, cTBS, and iTBS, scheduled one week apart to prevent carryover effects and at specific times of day and under no sleep pressure to account for the circadian cycle's influence on brain magnetic stimulation effects (Salehinejad et al., 2021b; Salehinejad et al., 2022b) (

Figure 2A). Right after each stimulation session, a researcher supervised the Buzz Lightyear task, which took around 20 minutes to complete. Participants completed 8 training trials followed by 48 main trials, which featured 8 video clip conditions repeated 6 times. Each block included all conditions defined by the participant's belief, the other's belief, and the presence or absence of the ball. Trials were randomized into 2 blocks of 24, with a 1500 ms interval and 300 ms jitter, and a short break between blocks. Participants and their parents were unaware of the stimulation sessions. After the final session, the participant was debriefed to confirm their lack of awareness regarding the task content and the implicit measurement of the theory of mind. All participants reported not understanding the study's objectives.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (R-4.2.2). A 2×2×3 repeated measures ANOVA was used to evaluate reaction time variability across conditions, considering own belief (P^- or P^+), other’s belief (A^- or A^+), and Stimulation type (sham, iTBS, cTBS). Paired t-tests with FDR correction compared reaction times across task conditions. Additionally, a 2×3 repeated measures ANOVA assessed the impact of TBS on mentalizing ability, factoring in task conditions (P^- A^+ or P^- A^-) and stimulation (sham, iTBS, cTBS). Following significant ANOVA effects, Paired t-tests with FDR correction also compared iTBS and cTBS effects on mentalizing. Mauchly’s test of sphericity was conducted, applying Greenhouse–Geisser correction when needed.

3. Results

3.1. Data Overview and Safety

All participants tolerated TBS without reporting serious side effects, except for three who experienced discomfort and were excluded from the study. We used the Interquartile Range (IQR) method to identify and remove outliers from the behavioral data across all sessions, retaining 97.5% of the data for our final analysis. Overall, the performance speed was significantly faster (F[

2,

22]=7.91, p<0.01; η_p^2=0.42, 95% CI: [0.13, 1.00]) in the iTBS (M=756.33, SD=348.62) and cTBS sessions (M=822.44, SD=350.4) compared to the sham (M=1188, SD=422.27).

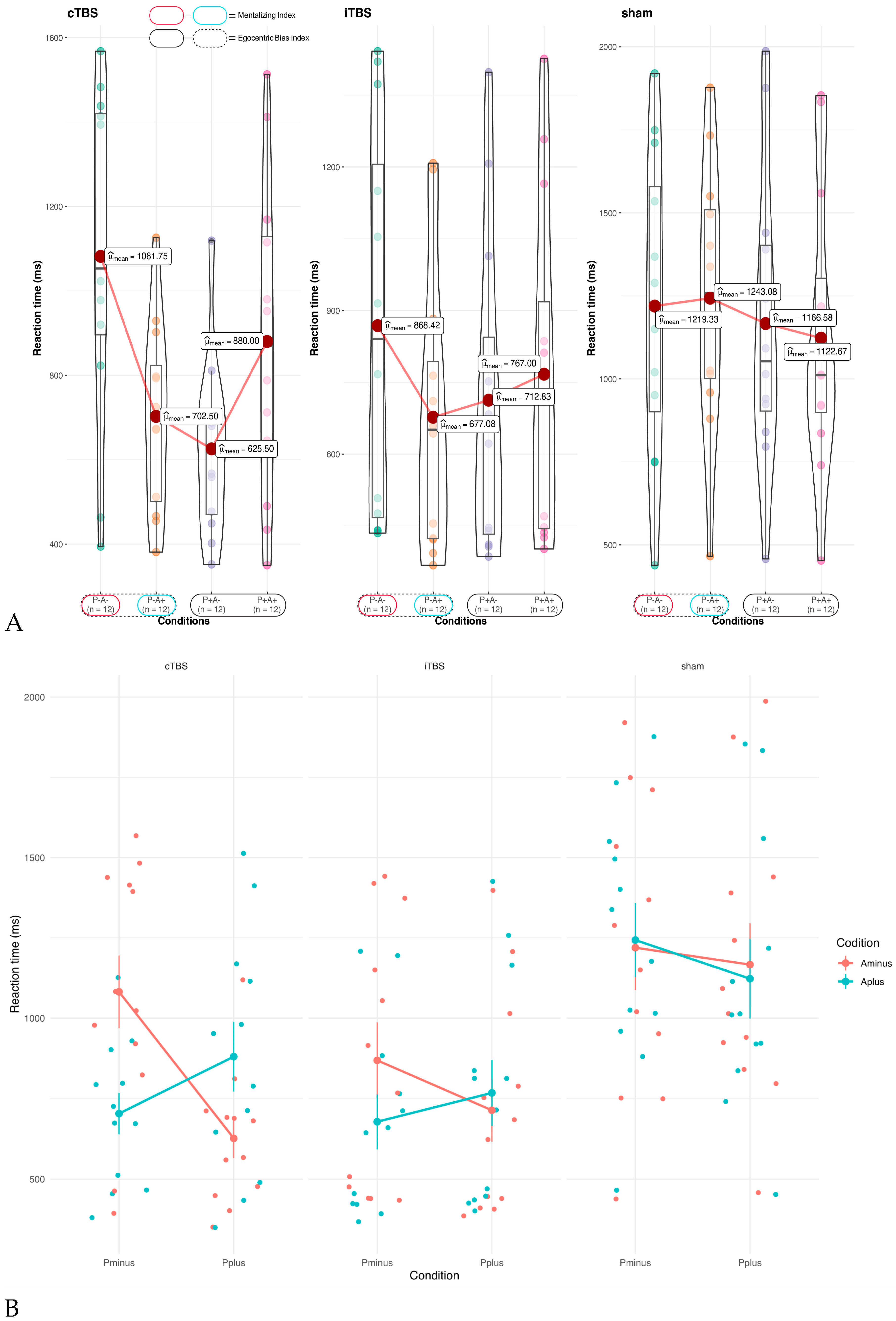

3.2. Efficacy of TBS on Implicit ToM

To assess the impact of TBS on implicit ToM, a two-way ANOVA was performed on the implicit MI, with task condition (P^- A^- and P^- A^+) and stimulation type (sham, cTBS, and iTBS) as within-subject factors. A significant task-condition×session interaction was found (F[

2,

22]=5.60, p<0.05; η_p^2=0.34, 95% CI:[0.06,1.00]) (

Table 2). FDR-corrected pairwise t-tests revealed significantly different reaction times between the P^- A^+ and P^- A^- conditions during cTBS (t[

11]=4.03, p_adj<0.01; d=1.16, 95% CI:[0.76,2.11]; MI =379.25ms) and iTBS sessions (t[

11]=2.89, p_adj<0.05; d=0.83, 95% CI:[0.58,1.39]; MI=191.33ms), but no difference was noted under sham sessions (t[

11]=-0.27, p_adj=0.79). The effect size for cTBS was greater than for iTBS (

Figure 3A).

3.3. Efficacy of TBS on Own vs Other’s Belief Interaction

The ANOVA results showed a significant interaction between own and other belief (F[

1,

11]=13.5, p<0.01; η_p^2=0.55, 95% CI: [0.17, 1.00]) and a three-way interaction involving own belief, other belief, and stimulation (F[

2,

22]=7.43, p<0.01; η_p^2=0.40, 95% CI: [0.12, 1.00]) (

Table 2,

Figure 3A). FDR-corrected pairwise t-tests revealed a significant difference in reaction times during cTBS sessions between the P^- A^- (M=1081.75, SD=392.6) and P^- A^+ (M=702.5, SD=222.95) task conditions (t[

11]=4.034, p_adj=0.01; d=1.16, 95% CI: [0.77, 2.09]). A similar significant difference was found between P^- A^- and P^+ A^- (M=625.5, SD=209.38) task conditions (t[

11]=4.30, p_adj=0.007; d=1.24, 95% CI: [0.88, 2.01]) under cTBS sessions. These results suggest that during cTBS sessions when there was a conflict between the participant's and agent's beliefs, reaction times were faster than when both held similar beliefs (

Figure 3).

3.3. Efficacy of TBS on Egocentric Bias

The ANOVA results indicated a significant main effect of Own Belief (F(1,11)=7.3, p<0.05, η_p^2=0.4; 95% CI: [0.05, 1.00], EB= 86.26 ms), linked to

egocentric bias. This bias led to faster reaction times in conditions where participants expected the ball's presence, compared to those where they did not. There was no stimulation effect on the egocentric bias, as there was no significant interaction between Own Belief and Stimulation (F(1.37, 15.06)=1.05, p=0.35, η_p^2=0.087, 95% CI: [0.00, 1.00]) (

Table 2,

Figure 3B).

4. Discussion

This randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study examined the effects of excitatory, inhibitory, and sham TBS on implicit ToM in individuals with ASD. Both iTBS and cTBS enhanced implicit ToM, with cTBS showing a more pronounced effect than iTBS. No significant effect of stimulation was observed on egocentric bias. These findings provide the first causal evidence, using NIBS, for the role of rTPJ in implicit mentalizing in ASD. Moreover, the results suggest a partial overlap between the neural correlates of implicit and explicit ToM.

Our results demonstrate that TBS targeting the rTPJ improves implicit ToM in ASD, aligning with prior research on ToM in neurotypicals showing involvement of rTPJ (Costa et al., 2008; Young et al., 2010; Krall et al., 2016). However, we found enhancement in implicit ToM in the ASD population, which, contrasts with previous studies reporting disruptive effects of NIBS on implicit ToM in neurotypicals (Bardi et al., 2017a; Filmer et al., 2019). These differences may be attributed to factors such as different baseline rTPJ activity or distinct cognitive processing patterns in ASD and different effects of stimulation protocols (Nicolo et al., 2015; Bradley et al., 2022; Vergallito et al., 2022). Individuals with ASD generally exhibit altered rTPJ connectivity and task performance compared to neurotypicals (Igelström et al., 2017; Nijhof et al., 2017; Nijhof et al., 2018; Boccadoro et al., 2019), which may be related to responsiveness to TBS. Furthermore, the prolonged and potent modulatory effects of TBS in ASD could explain the improvement in implicit ToM observed in this study, aligning with previous findings in neurotypicals (Oberman et al., 2010; Desarkar et al., 2015).

We also observed a significant effect of participants’ own beliefs on the egocentric bias, consistent with previous ToM studies in ASD (Begeer et al., 2012; Deschrijver et al., 2016; Nijhof et al., 2017), but stimulation did not affect this bias. This contrasts with a study conducted on neurotypicals, in which 10-Hz rTMS reported reduced egocentric bias (Bardi et al., 2017a). The divergence between our findings and those in neurotypicals could reflect fundamental differences in the neural mechanisms of ToM processing between ASD and non-ASD populations (Desarkar et al., 2015). Additionally, the timing of stimulation may play a role, as our task was conducted immediately following stimulation, whereas the rTMS study applied stimulation during the task highlighting the state-dependent effects of brain stimulation (Silvanto and Pascual-Leone, 2008; McCormick et al., 2020).

Lastly, we found that cTBS had a stronger effect on implicit mentalizing compared to iTBS. Here are several factors and conditions to consider. First, the excitatory and inhibitory hypothesized effects of iTBS and cTBS are based on motor cortical excitability that may act differently in nonmotor areas and in developing populations (Moliadze et al., 2018). Second, although cTBS is typically considered inhibitory, its effects on individuals with ASD may be context-dependent. For example, autistic individuals can exhibit a facilitatory response to cTBS, likely due to anomalies in GABAergic inhibitory mechanisms (Oberman et al., 2014; Jannati et al., 2020; Jannati et al., 2021). Additionally, cTBS has been found to enhance cognitive tasks, such as the Symbol Digit Coding test and self-other distinction (Salehinejad et al., 2021c; Kirkovski et al., 2022). Interestingly, the effect of cTBS on self-other distinction varies depending on individuals' levels of dispositional empathy, enhancing this ability in those with lower empathy but diminishing it in those with higher empathy (Bukowski et al., 2020). This might partially explain the superior effects of cTBS, yet the impact of iTBS on improving implicit ToM should not be understood.

Several limitations of the present study are noteworthy. The low sample size due to COVID-19 restrictions and the absence of a healthy control group are limitations that need to be addressed in future studies. Additionally, our findings should be interpreted with caution, as the participants were all male individuals with ASD who had normal or above-average intelligence, which may not reflect the broader ASD population. Future studies in a larger sample and with multiple stimulation sessions and neuroimaging measurements need to validate these findings and gain a clearer understanding of the differential effects of TBS modalities on rTPJ and neural levels.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that TBS of the rTPJ significantly improves implicit ToM in children and adolescents with ASD, providing further evidence for the casusl role of this region in social cognition. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the explicit and implicit ToM neural correlates may partially overlap. Additionally, these results suggest clinical implications for using TBS to address social deficits in individuals with ASD and contribute to the safety profile of TBS in developing populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Amir-Homayun Hallajian: Investigation, data curation, conceptualization, formal analysis, validation visualization, software, writing - original draft, writing – review, and editing. Fateme Dehghani-Arani: Conceptualization, methodology, resources, supervision, project administration. Sepehr Sima and Amirmahdi Heydari: writing - review and editing, visualization. Kiomars Sharifi: Formal analysis, visualization (Electrical Field Modeling). Yasamin Rahmati: Investigation, data curation, validation. Reza Rostami: Resources, project administration. Zahra Vaziri & Mohammad Ali Salehinejad: Methodology, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing, visualization.

Funding

The authors declare that no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors was received to support this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education at the University of Tehran, with approval number [IR.UT.PSYEDU.REC.1400.013]. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents, and assent was obtained from the child prior to the study

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical considerations, the data underlying the findings of this study are not publicly available. However, interested researchers may request access to the data by contacting the corresponding authors of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

List of Abbreviations

ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder

AQ: Autism-Spectrum Quotient

CONSORT: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

cTBS: Continuous Theta-burst Stimulation

dlPFC: Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex

GARS-2: Gilliam Autism Rating Scale

iTBS: intermittent Theta-burst Stimulation

mPFC: Medial Prefrontal Cortex

fMRI: Functional magnetic resonance imaging

rTMS: Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

SB-5: Stanford Binet IQ Test

SRS-2: Social Responsiveness Scale

STS: Superior Temporal Sulcus

TBS: Theta-burst Stimulation

ToM: Theory of Mind

rTPJ: Right temporoparietal Junction

References

- Ahmad N, Zorns S, Chavarria K, Brenya J, Janowska A, Keenan JP (2021) Are We Right about the Right TPJ? A Review of Brain Stimulation and Social Cognition in the Right Temporal Parietal Junction. Symmetry 13:2219. [CrossRef]

- Apperly IA, Butterfill SA (2009) Do humans have two systems to track beliefs and belief-like states? Psychol Rev 116:953. [CrossRef]

- Arioli M, Cattaneo Z, Parimbelli S, Canessa N (2023) Relational vs representational social cognitive processing: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging data. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 18:nsad003. [CrossRef]

- Bardi L, Six P, Brass M (2017a) Repetitive TMS of the temporo-parietal junction disrupts participant’s expectations in a spontaneous Theory of Mind task. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience 12:1775-1782. [CrossRef]

- Bardi L, Desmet C, Nijhof A, Wiersema JR, Brass M (2017b) Brain activation for spontaneous and explicit false belief tasks overlaps: new fMRI evidence on belief processing and violation of expectation. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience 12:391-400. [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen S (1997) Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind: MIT press.

- Baron-Cohen S (2000) Theory of mind and autism: A review. International review of research in mental retardation 23:169-184. [CrossRef]

- Begeer S, Bernstein DM, van Wijhe J, Scheeren AM, Koot HM (2012) A continuous false belief task reveals egocentric biases in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 16:357-366. [CrossRef]

- Boccadoro S, Cracco E, Hudson AR, Bardi L, Nijhof AD, Wiersema JR, Brass M, Mueller SC (2019) Defining the neural correlates of spontaneous theory of mind (ToM): An fMRI multi-study investigation. Neuroimage 203:116193. [CrossRef]

- Bradley C, Nydam AS, Dux PE, Mattingley JB (2022) State-dependent effects of neural stimulation on brain function and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 23:459-475. [CrossRef]

- Bukowski H, Tik M, Silani G, Ruff CC, Windischberger C, Lamm C (2020) When differences matter: rTMS/fMRI reveals how differences in dispositional empathy translate to distinct neural underpinnings of self-other distinction in empathy. Cortex 128:143-161. [CrossRef]

- Carruthers P (2017) Mindreading in adults: Evaluating two-systems views. Synthese 194:673-688. [CrossRef]

- Chen T, Gau SS-F, Wu Y-Y, Chou T-L (2022) Neural substrates of theory of mind in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An fMRI study of the social animation task. J Formos Med Assoc. [CrossRef]

- Costa A, Torriero S, Oliveri M, Caltagirone C (2008) Prefrontal and temporo-parietal involvement in taking others' perspective: TMS evidence. Behav Neurol 19:71-74. [CrossRef]

- Desarkar P, Rajji TK, Ameis SH, Daskalakis ZJ (2015) Assessing and stabilizing aberrant neuroplasticity in autism spectrum disorder: the potential role of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Frontiers in psychiatry 6:124. [CrossRef]

- Deschrijver E, Palmer C (2020) Reframing social cognition: Relational versus representational mentalizing. Psychological Bulletin 146:941. [CrossRef]

- Deschrijver E, Bardi L, Wiersema JR, Brass M (2016) Behavioral measures of implicit theory of mind in adults with high functioning autism. Cognitive Neuroscience 7:192-202. [CrossRef]

- Filmer HL, Fox A, Dux PE (2019) Causal evidence of right temporal parietal junction involvement in implicit Theory of Mind processing. Neuroimage 196:329-336. [CrossRef]

- Fonov V, Evans AC, Botteron K, Almli CR, McKinstry RC, Collins DL, Group BDC, others (2011) Unbiased average age-appropriate atlases for pediatric studies. Neuroimage 54:313-327. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y-Z, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC (2005a) Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 45:201-206. [CrossRef]

- Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC (2005b) Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 45:201-206. [CrossRef]

- Igelström KM, Webb TW, Graziano MSA (2017) Functional connectivity between the temporoparietal cortex and cerebellum in autism spectrum disorder. Cerebral Cortex 27:2617-2627. [CrossRef]

- Jannati A, Ryan MA, Block G, Kayarian FB, Oberman LM, Rotenberg A, Pascual-Leone A (2021) Modulation of motor cortical excitability by continuous theta-burst stimulation in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Neurophysiology 132:1647-1662. [CrossRef]

- Jannati A, Block G, Ryan MA, Kaye HL, Kayarian FB, Bashir S, Oberman LM, Pascual-Leone A, Rotenberg A (2020) Continuous theta-burst stimulation in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder and typically developing children. Front Integr Neurosci 14:13. [CrossRef]

- Kirkovski M, Hill AT, Rogasch NC, Saeki T, Fitzgibbon BM, Yang J, Do M, Donaldson PH, Albein-Urios N, Fitzgerald PB, others (2022) A single-and paired-pulse TMS-EEG investigation of the N100 and long interval cortical inhibition in autism spectrum disorder. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation 15:229-232. [CrossRef]

- Kovács ÁM, Téglás EH, Endress AD (2010) The social sense: Susceptibility to others’ beliefs in human infants and adults. Science 330:1830-1834. [CrossRef]

- Krall SC, Volz LJ, Oberwelland E, Grefkes C, Fink GR, Konrad K (2016) The right temporoparietal junction in attention and social interaction: A transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Hum Brain Mapp 37:796-807. [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur J-P, Aleman A, Baeken C, Benninger DH, Brunelin J, Di Lazzaro V, Filipović SR, Grefkes C, Hasan A, Hummel FC, others (2020) Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): an update (2014–2018). Clinical neurophysiology 131:474-528. [CrossRef]

- Lisanby SH, Schlaepfer TE, Fisch H-U, Sackeim HA (2001) Magnetic seizure therapy of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:303-305. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Xiao G, He K, Zhang L, Wu X, Li D, Zhu C, Tian Y, Hu P, Qiu B, others (2020) Increased accuracy of emotion recognition in individuals with autism-like traits after five days of magnetic stimulations. Neural Plast 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, Bullmore ET, Baron-Cohen S, Consortium MA, others (2011) Specialization of right temporo-parietal junction for mentalizing and its relation to social impairments in autism. Neuroimage 56:1832-1838. [CrossRef]

- McCormick DA, Nestvogel DB, He BJ (2020) Neuromodulation of brain state and behavior. Annual review of neuroscience 43:391-415. [CrossRef]

- Moliadze V, Lyzhko E, Schmanke T, Andreas S, Freitag CM, Siniatchkin M (2018) 1 mA cathodal tDCS shows excitatory effects in children and adolescents: Insights from TMS evoked N100 potential. Brain Research Bulletin 140:43-51. [CrossRef]

- Nejati V, Sharifian M, Famininejad Z, Salehinejad MA, Mahdian S (2024) The neural structures of theory of mind are valence-sensitive: evidence from three tDCS studies. J Neural Transm 131:1067-1078. [CrossRef]

- Ni H-C, Lin H-Y, Chen Y-L, Hung J, Wu C-T, Wu Y-Y, Liang H-Y, Chen R-S, Gau SS-F, Huang Y-Z (2022) 5-day multi-session intermittent theta burst stimulation over bilateral posterior superior temporal sulci in adults with autism-a pilot study. biomedical journal 45:696-707. [CrossRef]

- Nicolo P, Ptak R, Guggisberg AG (2015) Variability of behavioural responses to transcranial magnetic stimulation: Origins and predictors. Neuropsychologia 74:137-144. [CrossRef]

- Nijhof AD, Brass M, Wiersema JR (2017) Spontaneous mentalizing in neurotypicals scoring high versus low on symptomatology of autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry research 258:15-20. [CrossRef]

- Nijhof AD, Bardi L, Brass M, Wiersema JR (2018) Brain activity for spontaneous and explicit mentalizing in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An fMRI study. NeuroImage: Clinical 18:475-484. [CrossRef]

- Oberman LM, Pascual-Leone A, Rotenberg A (2014) Modulation of corticospinal excitability by transcranial magnetic stimulation in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8:627. [CrossRef]

- Oberman LM, Ifert-Miller F, Najib U, Bashir S, Woollacott I, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, Picker J, Rotenberg A, Pascual-Leone A (2010) Transcranial magnetic stimulation provides means to assess cortical plasticity and excitability in humans with fragile X syndrome and autism spectrum disorder. Front Synaptic Neurosci:26. [CrossRef]

- Polanía R, Nitsche MA, Ruff CC (2018) Studying and modifying brain function with non-invasive brain stimulation. Nat Neurosci 21:174-187. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Siniatchkin M (2024) Safety of noninvasive brain stimulation in children. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Ghanavati E, Rashid MHA, Nitsche MA (2021a) Hot and cold executive functions in the brain: A prefrontal-cingular network. Brain and Neuroscience Advances 5:23982128211007769. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Ghanavati E, Glinski B, Hallajian A-H, Azarkolah A (2022a) A systematic review of randomized controlled trials on efficacy and safety of transcranial direct current stimulation in major neurodevelopmental disorders: ADHD, autism, and dyslexia. Brain and Behavior n/a:e2724. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Wischnewski M, Ghanavati E, Mosayebi-Samani M, Kuo M-F, Nitsche MA (2021b) Cognitive functions and underlying parameters of human brain physiology are associated with chronotype. Nature Communications 12:4672. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Ghanavati E, Reinders J, Hengstler JG, Kuo M-F, Nitsche MA (2022b) Sleep-dependent upscaled excitability, saturated neuroplasticity, and modulated cognition in the human brain. eLife 11:e69308. [CrossRef]

- Salehinejad MA, Paknia N, Hosseinpour AH, Yavari F, Vicario CM, Nitsche MA, Nejati V (2021c) Contribution of the right temporoparietal junction and ventromedial prefrontal cortex to theory of mind in autism: A randomized, sham-controlled tDCS study. Autism Res 14:1572-1584. [CrossRef]

- Scheeren AM, de Rosnay M, Koot HM, Begeer S (2013) Rethinking theory of mind in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 54:628-635. [CrossRef]

- Schneider D, Slaughter VP, Becker SI, Dux PE (2014) Implicit false-belief processing in the human brain. Neuroimage 101:268-275. [CrossRef]

- Schurz M, Radua J, Aichhorn M, Richlan F, Perner J (2014) Fractionating theory of mind: a meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 42:9-34. [CrossRef]

- Senju A (2013) Atypical development of spontaneous social cognition in autism spectrum disorders. Brain and Development 35:96-101. [CrossRef]

- Silvanto J, Pascual-Leone A (2008) State-dependency of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Topogr 21:1. [CrossRef]

- Smith JR, DiSalvo M, Green A, Ceranoglu TA, Anteraper SA, Croarkin P, Joshi G (2023) Treatment Response of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Intellectually Capable Youth and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol Rev 33:834-855. [CrossRef]

- Sommer M, Döhnel K, Sodian B, Meinhardt J, Thoermer C, Hajak G (2007) Neural correlates of true and false belief reasoning. Neuroimage 35:1378-1384. [CrossRef]

- Spek AA, Scholte EM, Van Berckelaer-Onnes IA (2010) Theory of mind in adults with HFA and Asperger syndrome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 40:280-289. [CrossRef]

- Spengler S, von Cramon DY, Brass M (2009) Control of shared representations relies on key processes involved in mental state attribution. Hum Brain Mapp 30:3704-3718. [CrossRef]

- Spiers HJ, Maguire EA (2006) Spontaneous mentalizing during an interactive real world task: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 44:1674-1682. [CrossRef]

- Thielscher A, Antunes A, Saturnino GB (2015) Field modeling for transcranial magnetic stimulation: a useful tool to understand the physiological effects of TMS? In, pp 222-225: IEEE.

- Van Overwalle F (2009) Social cognition and the brain: A meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 30:829-858. [CrossRef]

- Vergallito A, Feroldi S, Pisoni A, Romero Lauro LJ (2022) Inter-individual variability in tDCS effects: A narrative review on the contribution of stable, variable, and contextual factors. Brain Sciences 12:522. [CrossRef]

- White S, Hill E, Happé F, Frith U (2009) Revisiting the strange stories: Revealing mentalizing impairments in autism. Child development 80:1097-1117. [CrossRef]

- White SJ, Frith U, Rellecke J, Al-Noor Z, Gilbert SJ (2014) Autistic adolescents show atypical activation of the brain's mentalizing system even without a prior history of mentalizing problems. Neuropsychologia 56:17-25. [CrossRef]

- Wimmer H, Perner J (1983) Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition 13:103-128. [CrossRef]

- Young L, Camprodon JA, Hauser M, Pascual-Leone A, Saxe R (2010) Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107:6753-6758. [CrossRef]

- Zemestani M, Hoseinpanahi O, Salehinejad MA, Nitsche MA (2022) The impact of prefrontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on theory of mind, emotion regulation and emotional-behavioral functions in children with autism disorder: A randomized, sham-controlled, and parallel-group study. Autism Res 15:1985–1200. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zhang H (2022) Effects of non-invasive neurostimulation on autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).