1. Introduction

As the Internet of Things (IoT) rapidly expands across all sectors, including smart homes and industrial applications, connecting billions of devices, the need for robust and secure device identification becomes increasingly important. However, this growth also increases vulnerability to security threats, making reliable identification essential for securing IoT networks [

1]. Limited security features and the wireless nature of many IoT networks make devices vulnerable to cyberattacks, including eavesdropping, spoofing, and unauthorized access, which can compromise entire networks [

2,

3]. Traditional security methods, including passwords and encryption, are becoming less effective in IoT networks due to the limited resources of IoT devices and the scalability challenges posed by the rapid growth of connected devices [

4]. Fortunately, device identification algorithms based on radio frequency fingerprinting (RFF) offer a promising solution to these challenges [

5]. However, to be effective, RF fingerprints must conform to the principle of uniqueness [

6], ensuring that each device, whether transmitting data or inactive, can be uniquely identified based on the intrinsic features of its RF signals. These features can be derived from the inherent variations introduced during the device manufacturing process. The key advantage of the RFF-based device identification algorithms is that they do not require any changes to the communication protocols on the RF devices and other IoT systems involved, nor do they require any additional hardware [

6,

7]. Thus, the RFF-based identification algorithms can provide a high level of security, making it difficult for attackers to replicate or spoof the distinctive RF fingerprint of a legitimate device. The effectiveness of these algorithms is inherently linked to the quality of the acquired RF signals [

7]. Raw RF signals are often susceptible to noise, interference, and distortion, acquisition errors, or hardware imperfections. These factors can affect the performance of the identification algorithms that rely on RF fingerprints to accurately classify devices. As a result, signal preprocessing becomes an indispensable tool for improving the quality of the RF signals used in the identification process. Signal preprocessing methods are used to standardize the input data ensuring that it meets the specific requirements of the classifier. Choosing the right preprocessing method is crucial to accurate device identification [

8].

RF fingerprinting is a useful technique for identifying IoT devices. For example, in 2019, Tu et al. [

9] studied four types of RF fingerprint feature extraction algorithms based on statistical features. They used an SVM-based classifier and applied the robust principle component analysis (RPCA) to reduce its dimensionality. Also, in 2019, Nouichi et al. [

10] proposed an approach to detect emitted wireless signals from IoT devices based on a software defined radio (SDR), considering that the cryptography-based authentication protocols are impractical for the IoT systems. On the other hand, in 2020, Aghnaiya et al. [

11] investigated the identification of WiFi devices using RF device fingerprints. They demonstrated that intrinsic features of RF devices can be effectively used to detect and classify them. Also, in 2020, Lin et al. [

12] proposed a method based on the detection of complex and nonlinear patterns arising in the interaction between different frequency components of RF signals to recognize wireless devices. Similarly, in 2020, Uzundurukan et al. [

2] developed an RF fingerprinting system to identify Bluetooth devices. They demonstrated that their strategy was effective in distinguishing between different Bluetooth devices operating in a crowded IoT system. In 2022, Morge-Tollet et al. [

13] highlighted the RF fingerprinting as a reliable option for the node authentication in IoT networks as a non-cryptographic method. They proposed an RF eigen-fingerprinting method based on singular value decomposition (SVD), which is inspired by face recognition studies based on the Ljung-Box test, a statistical authentication approach. Also, in 2022, Chen et al. [

14] proposed a method based on on convolutional neural networks (CNN), combinatorial randomness, and on-chip time-varying RF fingerprints, which have been lightweight-implemented for Bluetooth Low-Energy (BLE) systems to achieve a fast inference of unique features in the IoT environments. In 2024, Peng et al. [

15] proposed a method based on the wavelet coefficient graph and differential spectrum to identify signal inconsistencies in Long Term Evolution (LTE) systems.

In this context, it is also worth reviewing the survey prepared in 2023 by Xie et al. [

16], where they considered the following signal preprocessing stages in the identification process: i) RF fingerprint extraction, ii) further processing, and iii) RF fingerprint identification. They also summarized the carrier frequency offset estimation, denoising, and channel cancellation. Finally, they highlighted the major challenges of the RF fingerprint identification and some future research trends.

In any case, the RFF methods face significant implementation and security challenges when intended for IoT scenarios. Techniques like time synchronization and frequency correction require significant computational resources, which can slow down processing, especially for large datasets or in real-time applications [

15]. Similarly, feature extraction methods are resource-intensive, requiring significant memory and processing power, which can make them impractical for resource-constrained IoT devices [

12]. The sequential nature of preprocessing can introduce latency, affecting the system’s ability to perform real-time identification in dynamic environments [

14]. In addition, early stages of preprocessing are often sensitive to noise, leading to potential errors in pattern recognition and feature extraction [

12]. While dimensionality reduction optimizes the feature set, it may inadvertently discard important details, affecting classification accuracy [

14]. Implementing and fine-tuning these preprocessing steps also requires specialized expertise, and even small errors in configuration can affect system performance. Furthermore, the effectiveness of preprocessing is highly dependent on the quality of the signal acquisition hardware; inconsistent or low-quality hardware can degrade the entire process, reducing the reliability of RFF systems [

15].

On the other hand, the supervised learning algorithms have been widely used for RFF-based classification systems. Support vector machine (SVM), random forest, and neural network (NN) are strategies that have demonstrated significant potential for detecting the intrinsic RF signals of IoT devices. For example, in 2018, Jafari et al. [

17] proposed a wireless device identification platform based on RF device features to improve the security of IoT networks by using deep learning techniques. They used deep, convolutional, and recurrent NN to identify the wireless devices, including whether the devices are from the same manufacturer. On the other hand, in 2019, Yu et al. [

18] used the RFF approach in an SVM-based classifier to identify ZigBee devices, achieving a suitable level of classification accuracy. Also, in 2019, Ali et al. [

19] compared the performance of machine learning models and found that SVM-based identification algorithms provide an optimal balance between computational efficiency and classification performance for resource-constrained environments, such as those found in IoT systems. In 2022, Huang et al. [

20] proposed a classification RFF-based method to improve the effectiveness of a classifier based on ensemble learning and a CNN. Also, in 2022, Yang et al. [

21] proposed a CNN&RFF-based model to implement a lightweight classifier. It is also worth reviewing the survey prepared in 2022 by Jagannath et al. [

22] presented a survey of RF fingerprinting approaches considering from a traditional view to the latest deep learning-based algorithms.

To address these challenges, this paper contributes by evaluating four signal preprocessing methods based on the normalization, mean, maximum, and minimum of the raw signals to improve data consistency and enhance classification accuracy. These methods were selected because they address common issues in raw RF signals, such as variability in signal strength and noise, which can negatively affect the performance of classification algorithms. By scaling the signal peaks, these preprocessing methods aim to standardize the input data, ensuring that key signal features are more effectively captured and utilized by the classifier. An SVM classifier, known for its effectiveness in binary and multi-class tasks, is used to assess the impact of these preprocessing methods, building on the work of [

2]. The findings show that RFF requires careful extraction of a device’s unique signal characteristics to effectively distinguish between classes.

The paper is divided into five sections.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the dataset, which consists of Bluetooth signals from multiple devices. It provides the definition and characteristics of these signals, and it details the preprocessing methods. In addition, this section describes the configuration of the SVM classifier, including the selection of the kernel, and the experimental setup for training and testing.

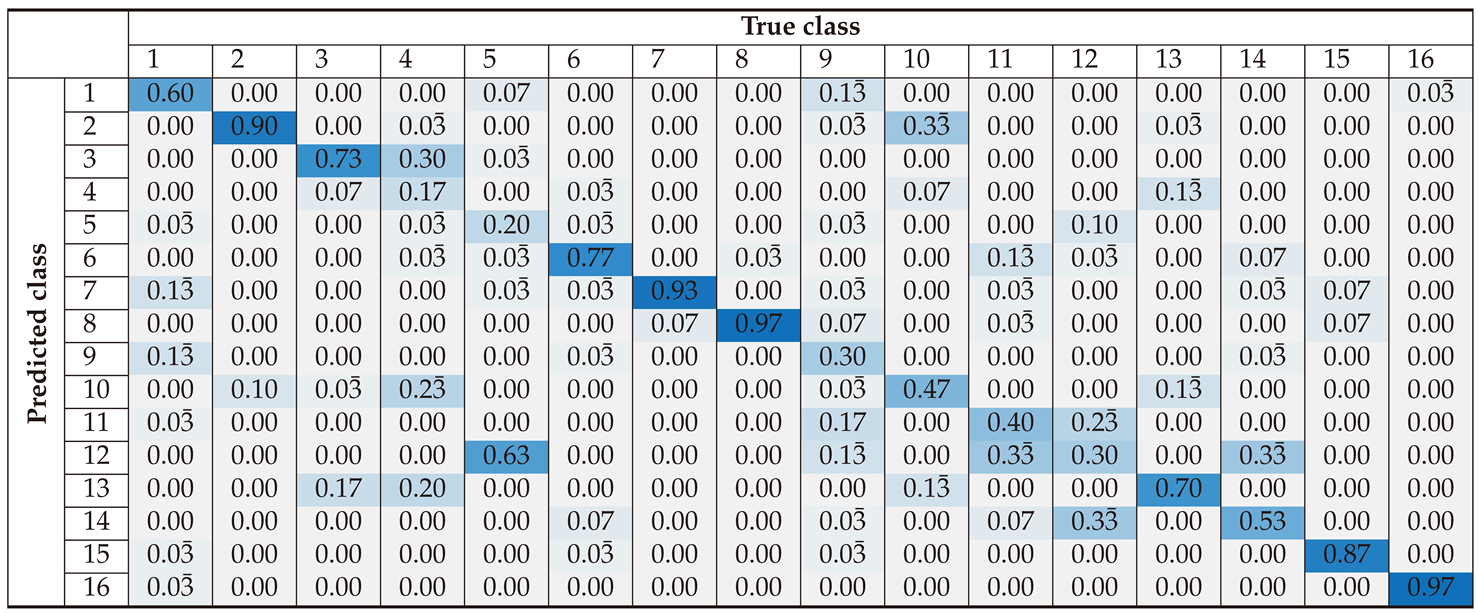

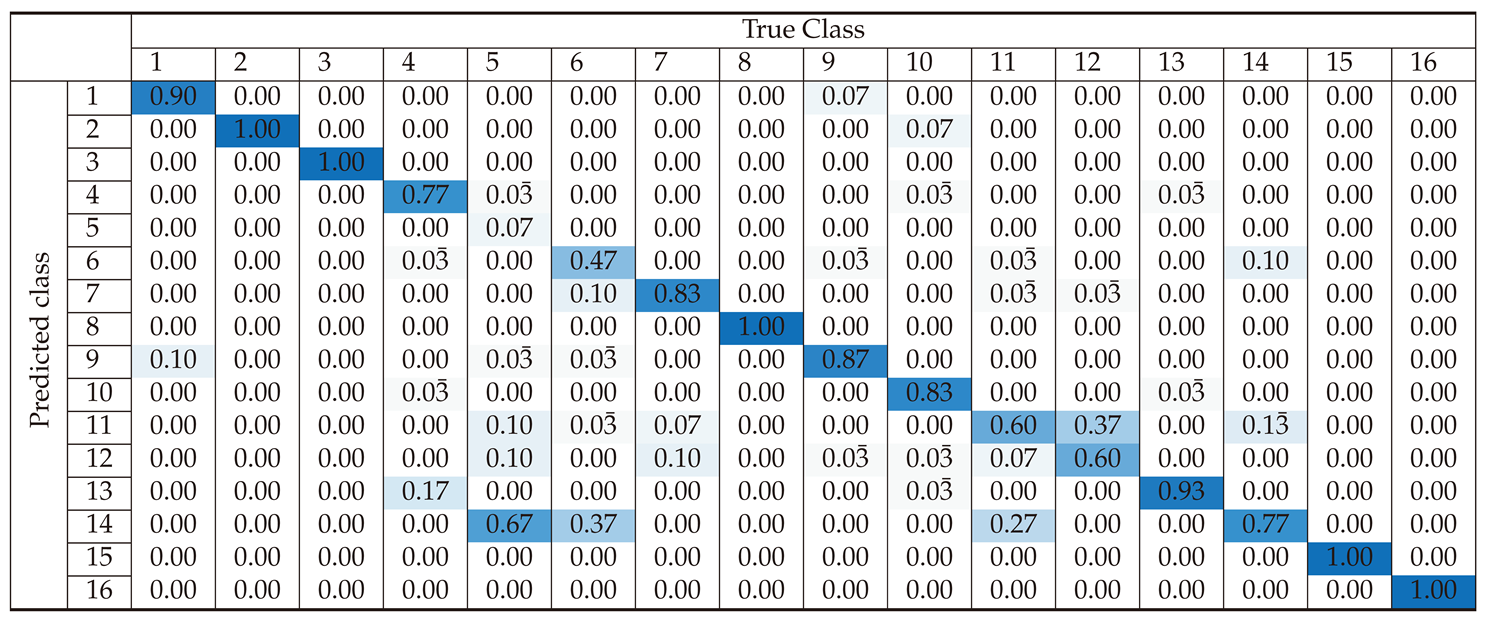

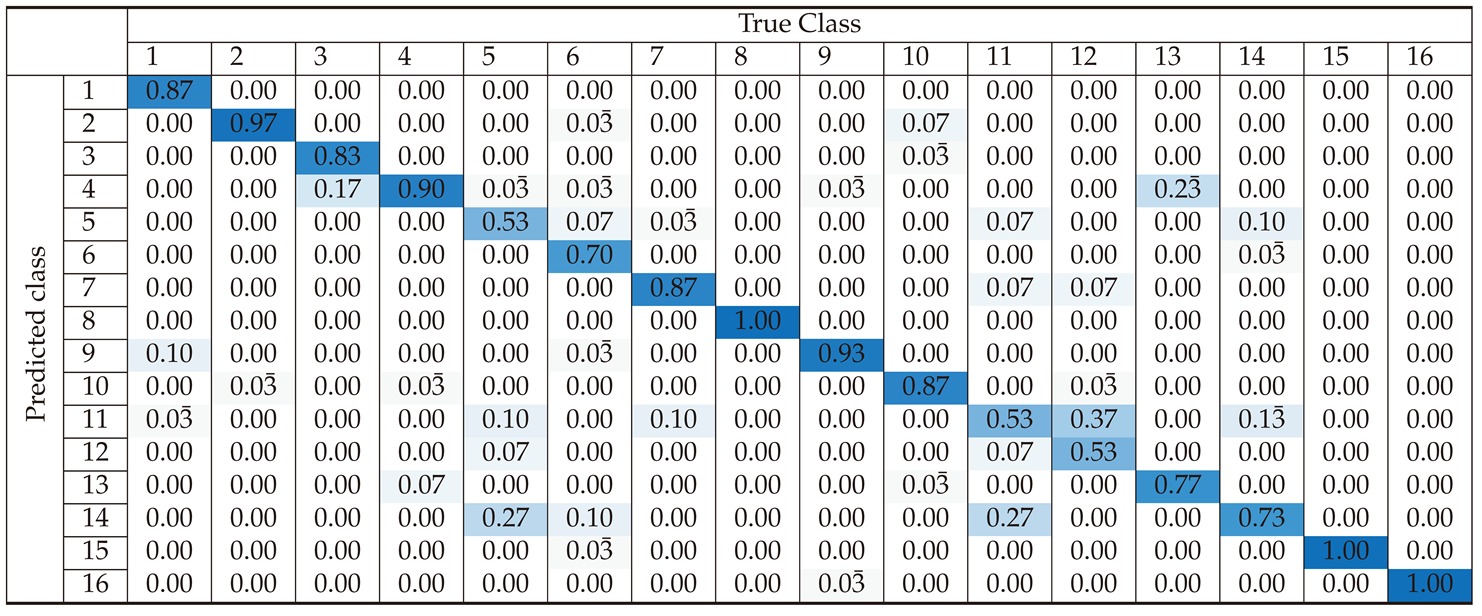

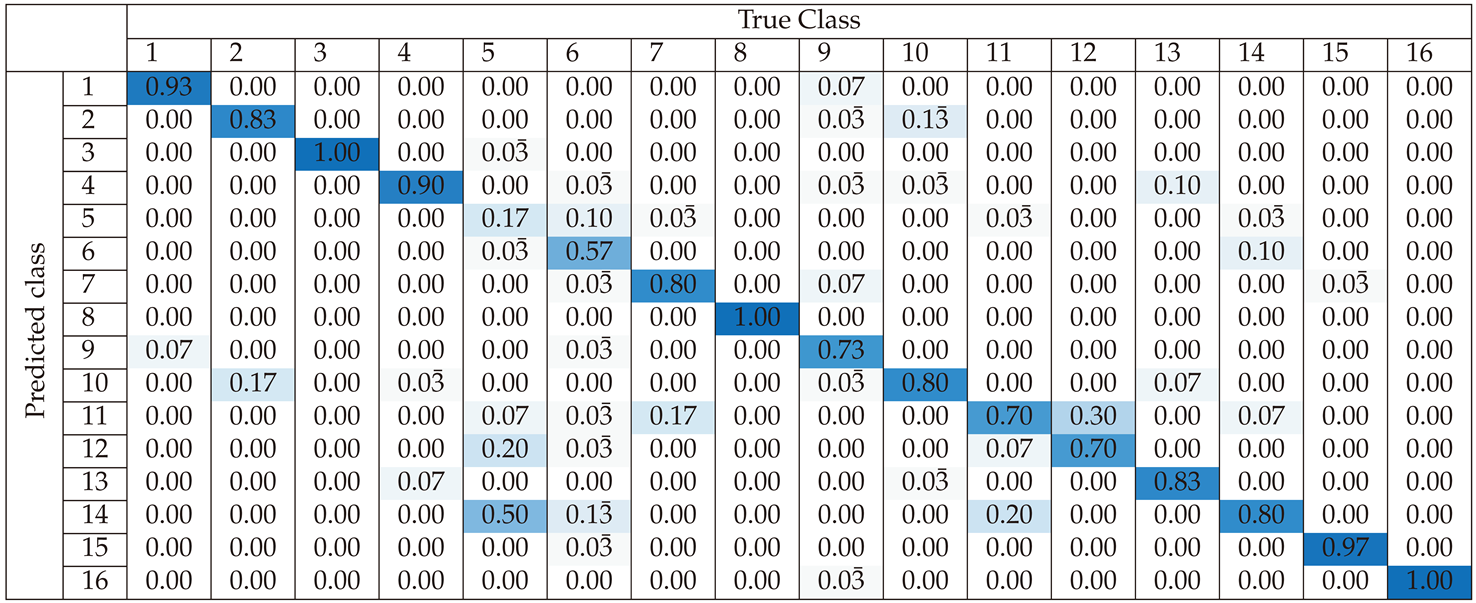

Section 3 presents the classification performance for each preprocessing approach, using confusion matrices and accuracy metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of the SVM-based classifier. This section demonstrates how different preprocessing methods influence classification accuracy across various device classes.

Section 4 offers an in-depth analysis of the results, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each preprocessing method. It examines the causes of misclassifications and discusses the balance between improving accuracy and maintaining computational efficiency. This section also identifies potential areas for optimization, such as improving the model robustness to noise and its ability to generalize across different datasets. Lastly,

Section 5 summarizes the key findings, emphasizing the importance of preprocessing in enhancing the effectiveness of RFF-based device identification. It discusses the broader implications for IoT security and proposes future research directions, including advanced feature extraction, real-world validations, and the exploration of alternative machine learning models to further enhance classification performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description

The dataset used in this work was extracted from the RF signal dataset created by Uzundurukan et al. [

3]. They captured RF signals from 27 smartphones, representing six different manufacturers, and it serves as a comprehensive resource for RFF. For each Bluetooth, they captured 150 RF signals, for a total of 12,900 signal recordings. They collected the RF signals under controlled laboratory conditions to minimize external interference and to ensure high data quality and consistency. In the Uzundurukan dataset includes RF signals recorded at 5 Gsps, 10 Gsps, and 20 Gsps using a Tektronix TDS7404 oscilloscope. In addition, lower-frequency signals were acquired at 250 Msps using a modular RF front-end system connected to the oscilloscope. For this work, 16 smartphone radios were selected and paired as twins, representing eight different brands. Each smartphone was assigned to a specific class, where devices within the same pair (or twin) belong to the same model but are treated as different classes. For instance, as shown in

Table 1, Class 1 corresponds to "iPhone 5 - 1," while Class 2 corresponds to its twin, "iPhone 5 - 2." Similarly, this pattern continues for other models, ensuring that each twin device is categorized into its unique class.

Understanding the distinctions between these classes is critical for evaluating RFF performance, as subtle variations between twin devices test the robustness of the classification algorithm. These class distinctions are further explored in the next section, where the definition and characteristics of raw Bluetooth signals are discussed in detail. This provides the foundation for analyzing how these signals can be used to uniquely identify devices within and across classes.

2.2. Definition and Characteristics of Raw Bluetooth Signals

Each Bluetooth signal carries intrinsic features that form the basis of RFF, which allows devices to be identified based on their unique characteristics. As the signals transition through three distinct states, these features become more apparent.

Figure 1a shows how the complete Bluetooth signal as detected by the receiver, while

Figure 1b highlights the envelope of the signal, making it easier to observe the transitions between these states.

The first state, known as the initial state, captures only the internal noise generated by the Bluetooth receiver. At this stage, the transmitter has not yet started sending signals, and the noise from the receiver serves as a baseline for further analysis. Once the transmitter is activated, the signal enters the transient state. During this phase, the receiver begins to detect the intrinsic noise from the transmitter in addition to its own noise. This state reflects the transition as the Bluetooth transmitter ramps up, providing valuable insight into the device’s unique signal behavior. Finally, the signal reaches the steady state, where both the intrinsic noise of the transmitter and the receiver are combined. This phase represents the full interaction between the two devices and captures the overall noise profile of the communication system.

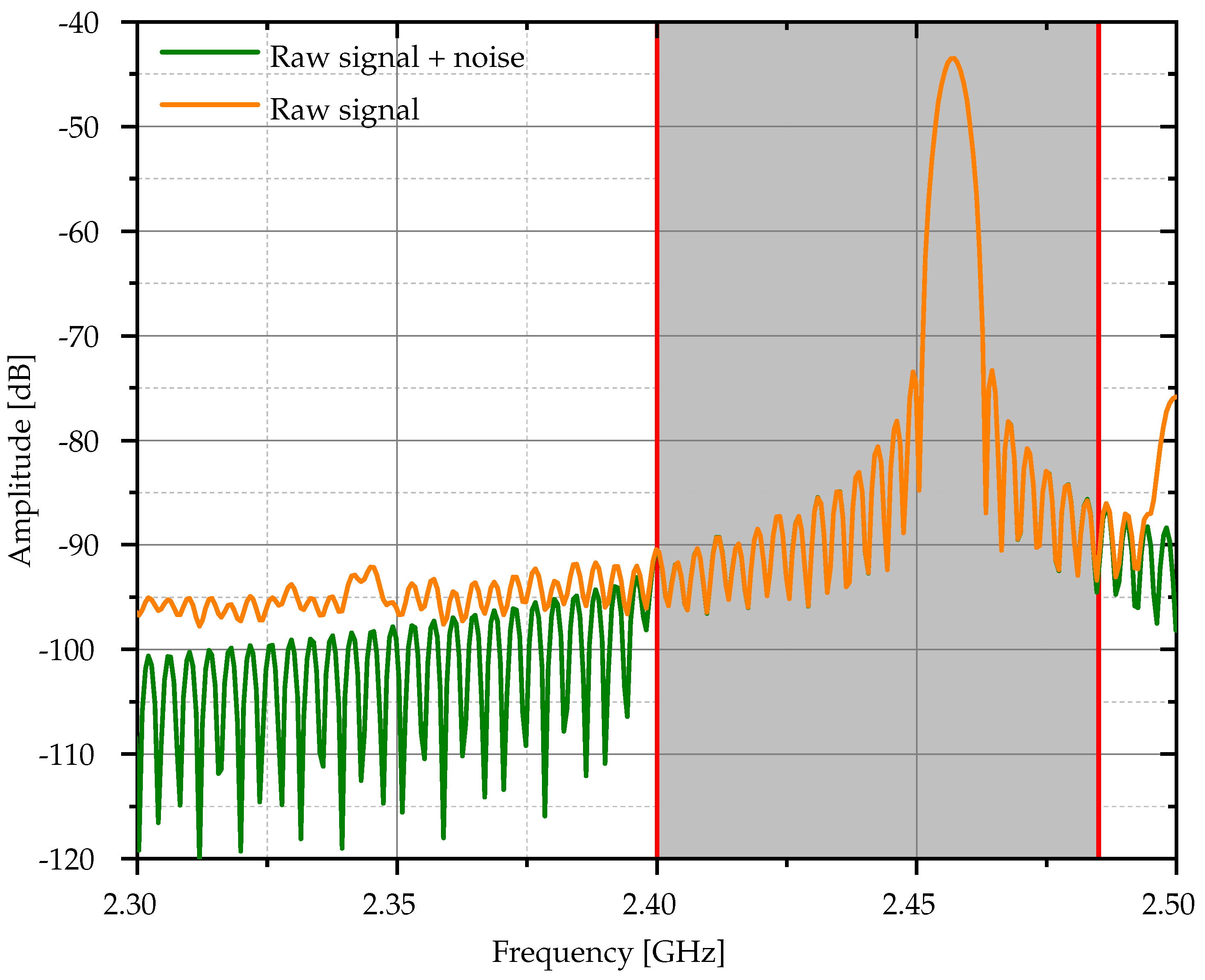

On the other hand,

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency spectrum of a Bluetooth signal, highlighting the presence of unwanted frequencies combined with noise, which includes the environmental electromagnetic interference and the system noise. This feature highlights the importance of implementing a bandpass filter to improve the signal fidelity. The bandpass filter extracts the signal in the range from 2.40 GHz to 2.48 GHz. The shaded gray area in

Figure 2 highlights the effect of the bandpass filter. This process ensures that the raw signal provided to subsequent preprocessing methods is cleaner, allowing for more accurate analysis and classification in RFF tasks. Therefore, the raw Bluetooth signal represents the unprocessed transmission captured directly from the target device. This signal contains intrinsic features derived from the device hardware, specifically from the transmitter. These features make the raw signal a rich source of information that can be used as a radio frequency fingerprint because they reflect unique device-specific attributes.

However, the raw signal also has a wide range of frequencies, often containing unwanted frequencies and noise that can obscure the critical features needed for accurate classification. Without preprocessing, such as filtering or scaling, the quality of the raw signal can be degraded, resulting in reduced performance of machine learning models. Therefore, preprocessing methods such as bandpass filtering are essential to isolate the primary signal components and ensure that the raw signal is suitable for further analysis.

2.3. Preprocessing Methods

The preprocessing methods must standardize the signals used in an analysis to ensure that the signal features can be interpreted by the classifier.

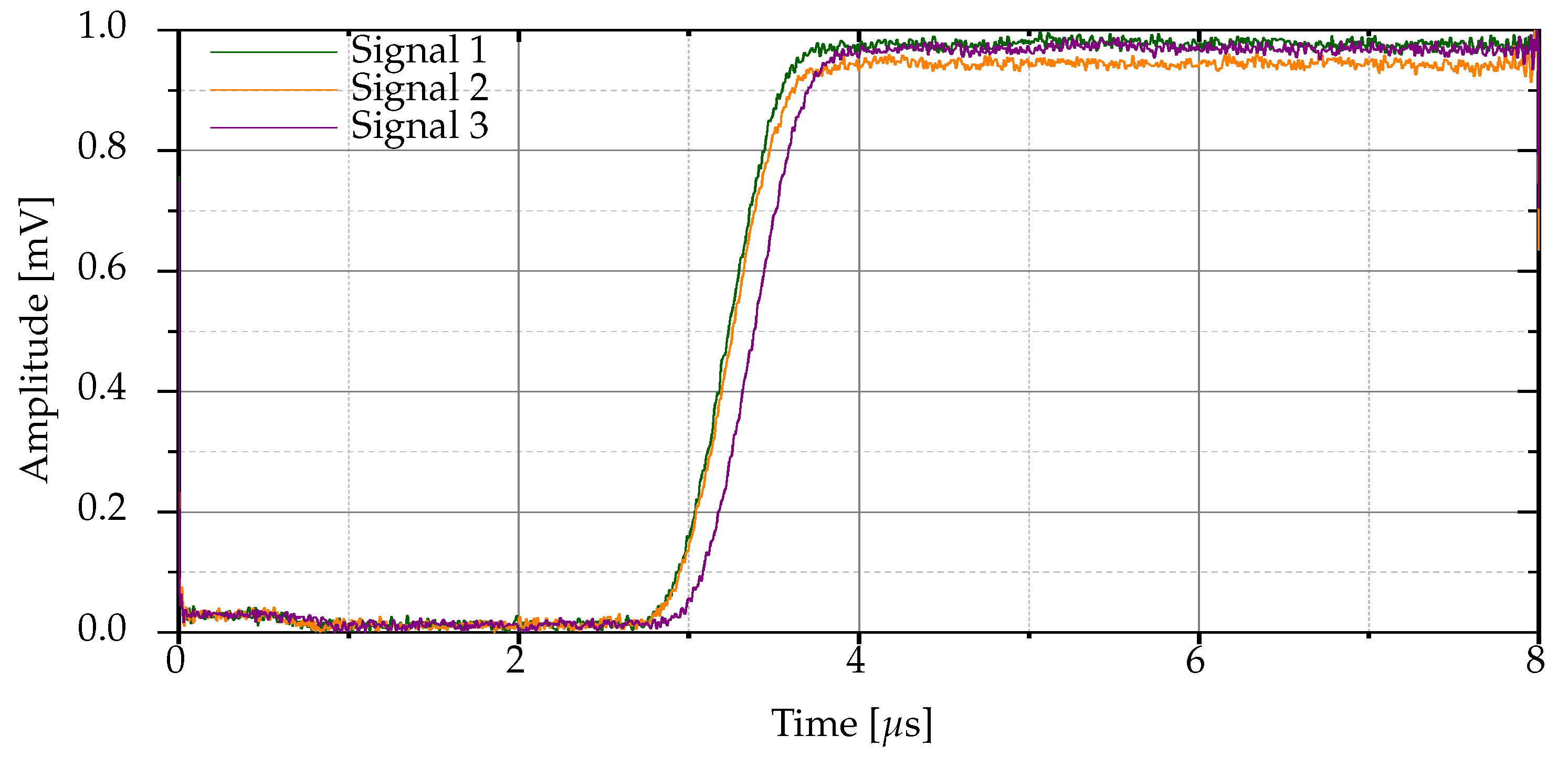

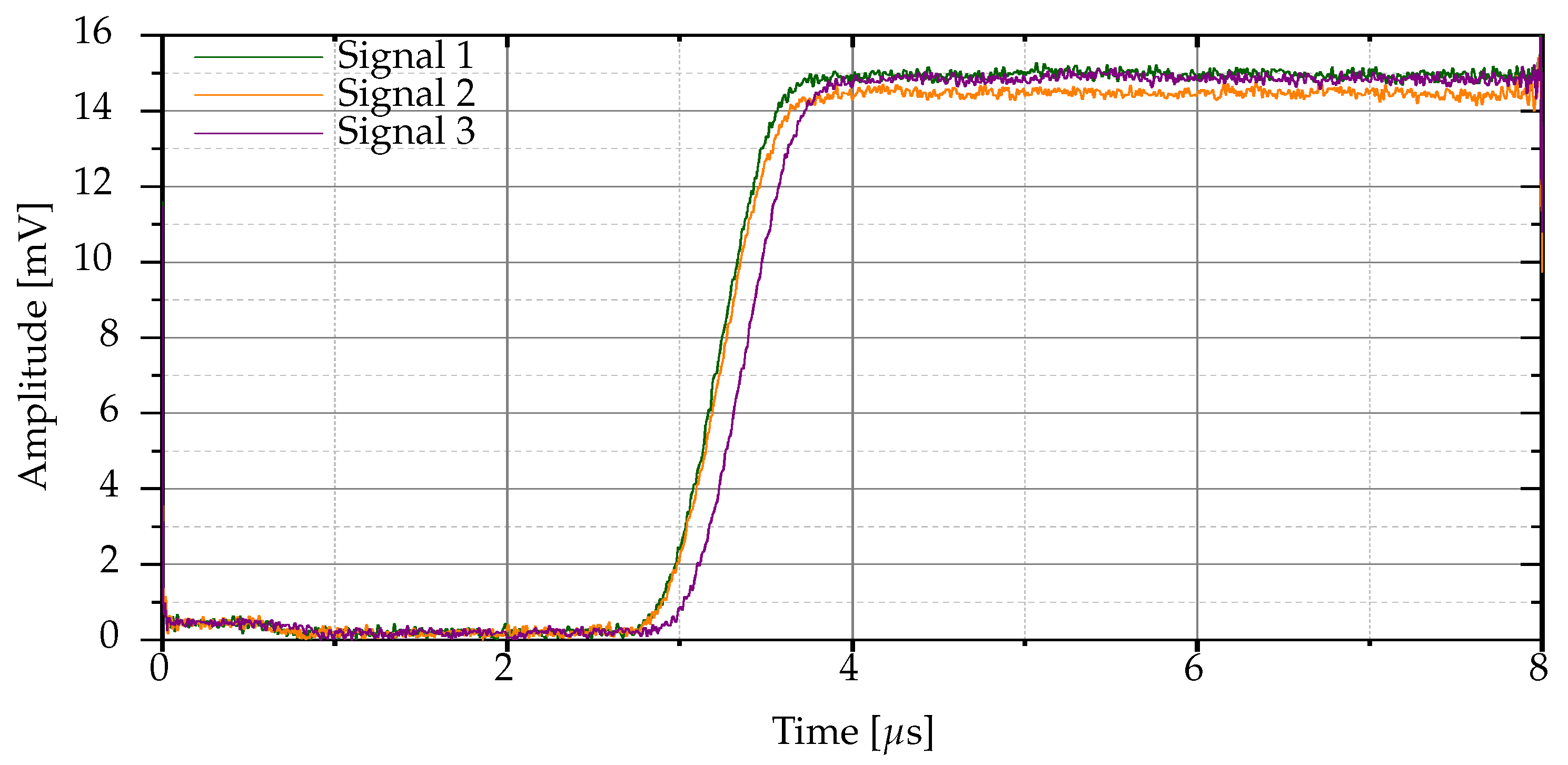

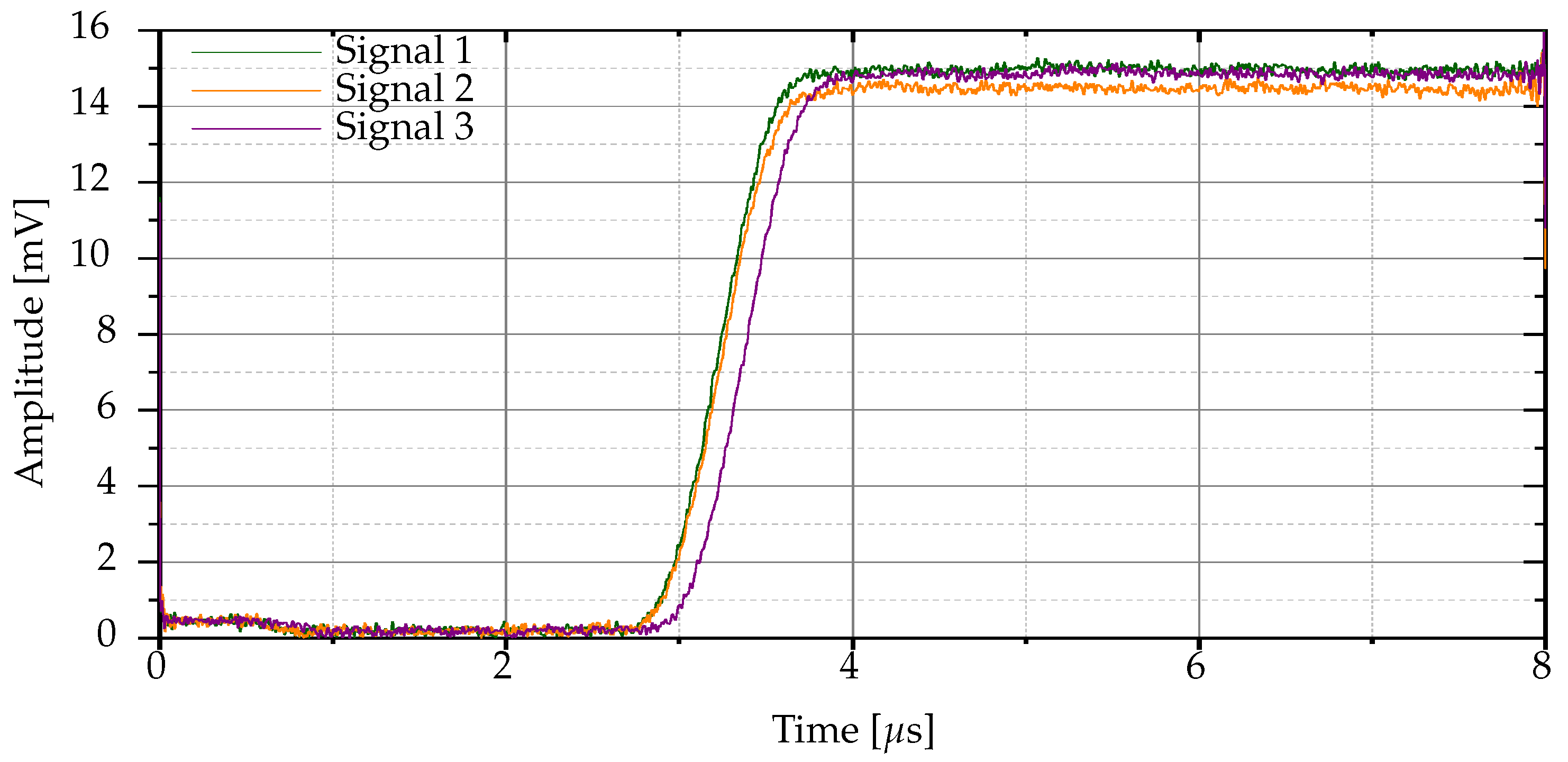

Figure 3 shows the envelopes of the three radio frequency signals acquired from the same Bluetooth device, which have some differences.

Therefore, in this study, four preprocessing methods are defined to adjust the amplitude of the raw Bluetooth signals. These methods are defined as follows and are designed to improve data consistency and improve the classification accuracy by emphasizing key features of the raw Bluetooth signals and improving the performance of a classification algorithm.

Definition 1 (Scaled signals)

. The signal , given in Eq. 1, is the scaled variant of the Bluetooth signal , assuming that is the scaling factor, represents the maximum magnitude reached by , and α is a dynamic term for adjusting the scaling factor that depends on the selected preprocessing method.

where i = 1, 2, 3, ... N.

Definition 1 ensures that the raw Bluetooth signals are dynamically adjusted based on and , preserving their time-varying features and avoiding the significant differences in amplitude of a variety of Bluetooth signals produced by the same device.

Definition 2 (Normalized raw signals). is the normalized variant of when , meaning that is scaled by its maximum value, without any other scaling adjustment.

The envelopes of the normalized variants computed for the Bluetooth signals in

Figure 3 are shown in

Figure 4.

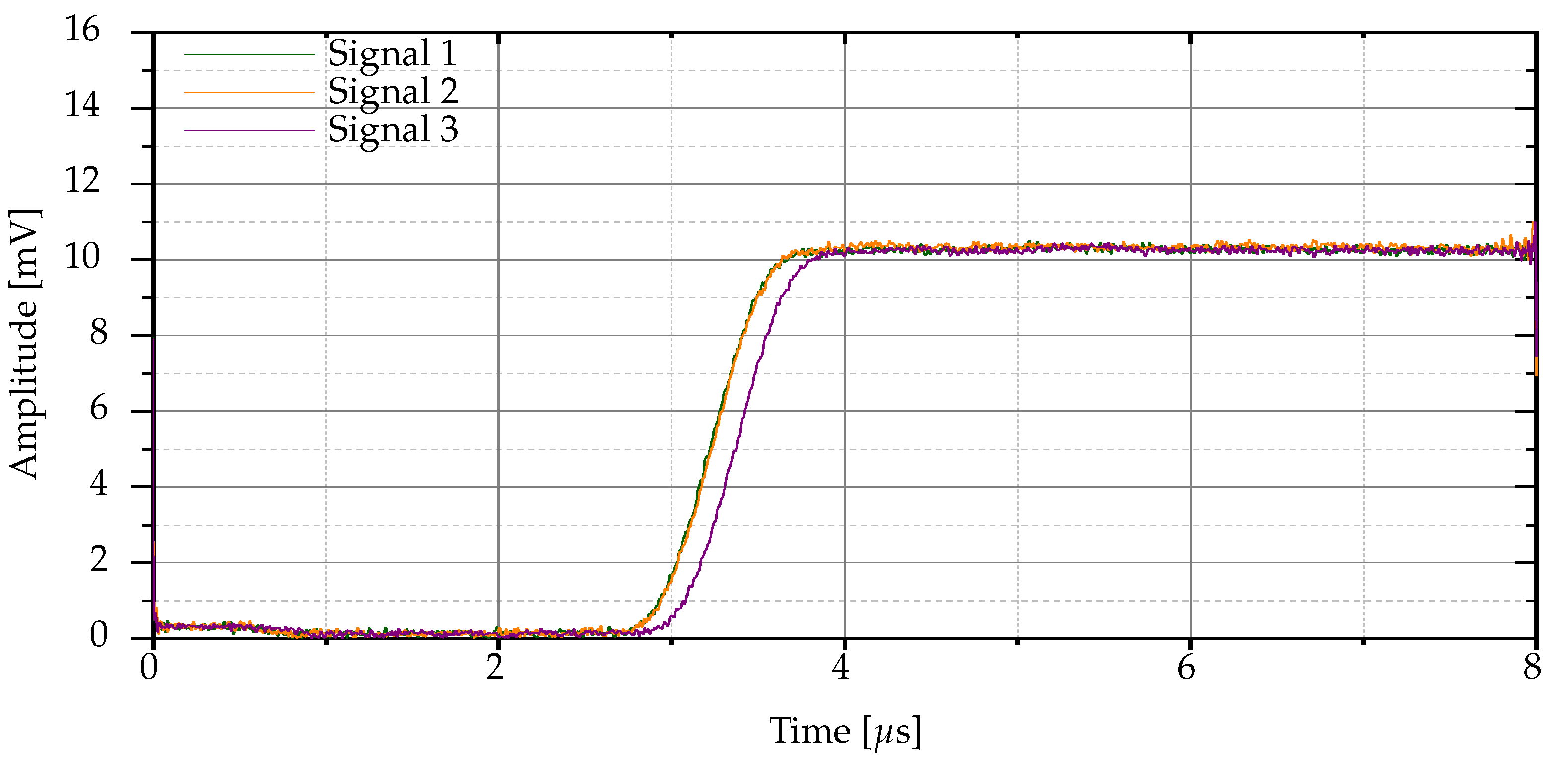

Definition 3 (Mean-normalized raw signals)

. is the mean-normalized variant of when α is computed using Eq. 2 and N Bluetooth signals from the same Bluetooth device are considered.

It should be noted that this approach reduces the signal variability by applying a global scaling factor.

Figure 5 illustrates the envelopes of the mean-normalized raw signals for the three Bluetooth signals of

Figure 2. Typically,

.

Definition 4 (Max-normalized raw signals)

. is the max-normalized variant of when α is computed using Eq. 3 and N Bluetooth signals from the same Bluetooth device are considered.

This approach uses the global maximum in the set of Bluetooth signals from same device.

Figure 6 illustrates the envelopes of the max-normalized raw signals for the three Bluetooth signals of

Figure 2.

Definition 5 (Min-normalized raw signals)

. is the min-normalized variant of when α is computed using Eq. 4 and N Bluetooth signals from the same Bluetooth device are considered.

This approach minimizes the influence of high peaks in the set of Bluetooth signals from the same device, emphasizing lower signal components.

Figure 7 illustrates the envelopes of the min-normalized raw signals for the three Bluetooth signals of

Figure 2.

2.4. Classifier Description and Experimental Setup

The SVM classifier was parameterized in accordance with the methodology outlined in [

2], utilizing a quadratic polynomial kernel to effectively handle complex, non-linear relationships in Bluetooth signal data. The data split was conducted randomly to ensure robust and unbiased evaluation, while feature extraction focused on higher-order statistics (HOS) derived from transient Bluetooth signals, providing a rich set of attributes for classification.

The implementation was performed using MATLAB, facilitating efficient data processing and experimentation. The computational setup for this study included a device with the following specifications: AMD Ryzen 5 2500U with Radeon Vega Mobile Graphics at 2.00 GHz, 32 GB of RAM (30.9 GB usable), and a 64-bit operating system. This hardware configuration ensured smooth execution of the computationally intensive tasks associated with SVM training and testing. The results highlight the classifier’s potential as a powerful tool for RFFs, particularly when optimized for transient signal characteristics.

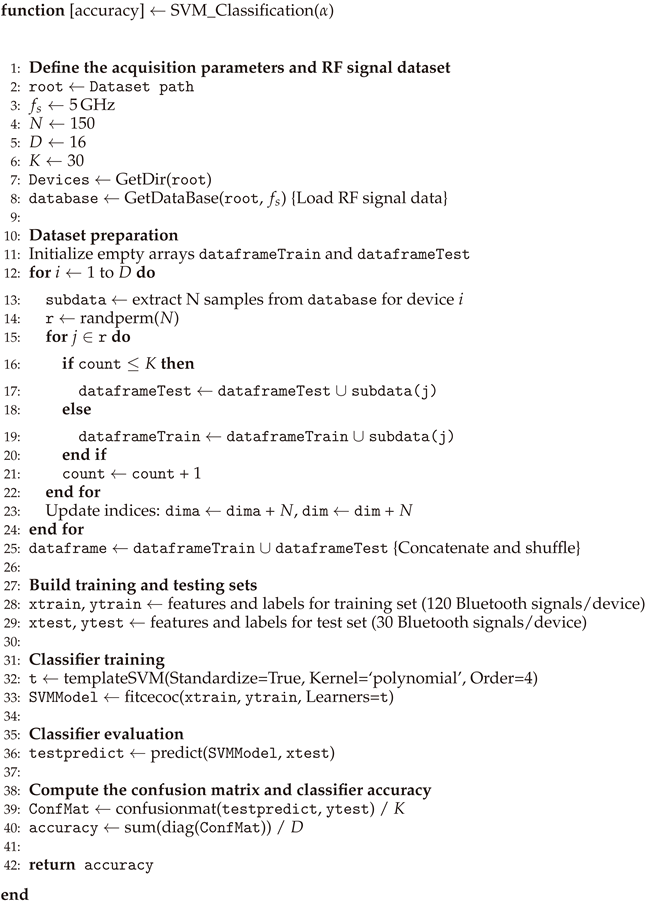

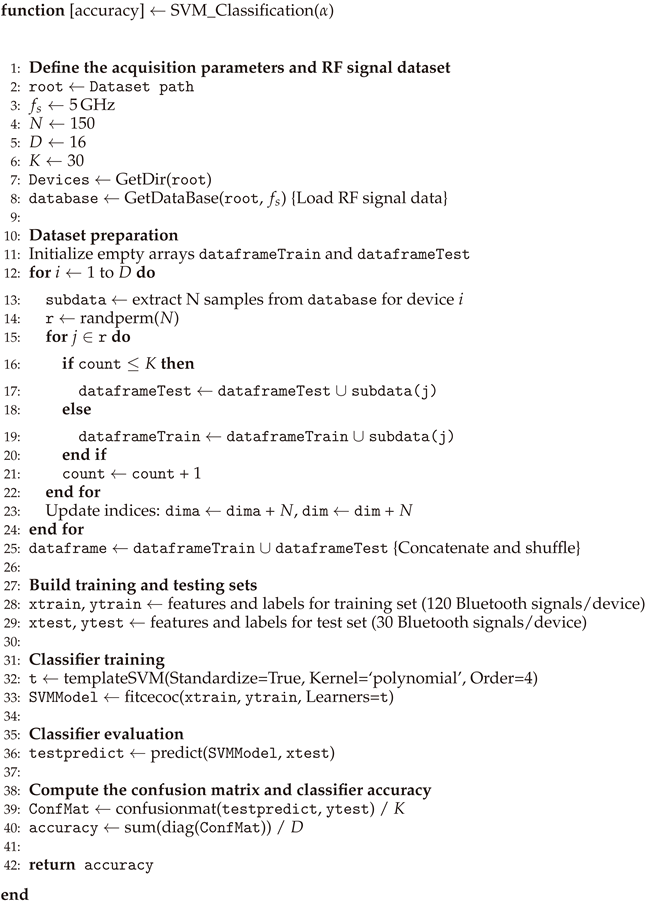

The SVM-based classifier procedure is illustrated step-by-step in the Algorithm 1. It begins with loading the parameters and the RF dataset, which includes preparing the data for analysis. The dataset preparation involves creating separate storage for training and testing data, followed by iterating through each device to extract 150 signal samples. For each device, 30 samples are reserved for testing while the remaining 120 are used for training.

Afterward, the training and test sets are concatenated and shuffled to ensure a randomized distribution of data. The data is then split into features and labels for the training and test sets, using

xtrain and

ytrain for the training data and

xtest and

ytest for testing. The algorithm proceeds by training an SVM model using a polynomial kernel with an order of 4, ensuring that the data is standardized to improve training consistency. Once the model is trained, it is evaluated on the test set, with predictions being generated for the test samples. To assess the model’s performance, a confusion matrix is computed, and the accuracy is calculated by comparing the predicted labels to the true labels. The procedure concludes by outputting the overall classification accuracy, which provides insight into the model’s effectiveness. The flowchart in

Figure 8 captures the entire process, ensuring a comprehensive overview of the algorithm’s workflow from data loading to final evaluation, this process aligns with the algorithm detailed in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1 SVM-based classifier |

|

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and R. V.-M.; Methodology, R.F. S-C., M.M., and R. V.-M.; Software, R.F. S-C.; Validation, M.M., D. A.-T., and R. V.-M.; Formal analysis, M.M. and R.V.-M.; Investigation, R.F. S-C., M. M., and R. V.-M.; Data curation, R.F. S-C., D. A.-T., and R. A. V.-D.; Writing–original draft, R.F. S-C. and R. V.-M.; Writing–review & editing, M. M., R. A. V.-D., and R. V.-M.; Visualization, M. M., R. A. V.-D., and D. A.-T.; Supervision, M. M. and R. V.-M., Project administration, R. V.-M.; Funding acquisition, R.V.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.