Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- O’Connor et al. [12] examined camera settings and their impact on image and orthomosaic quality, focusing on geosciences.

- Roth et al. [13] developed mapping software and provided a strong mathematical foundation.

- Assmann et al. [14] offered general flight guidelines, particularly for high latitudes and multispectral sensors.

- Tmusic et al. [15] presented general flight planning guidelines, including data processing and quality control, though with less focus on flight-specific details.

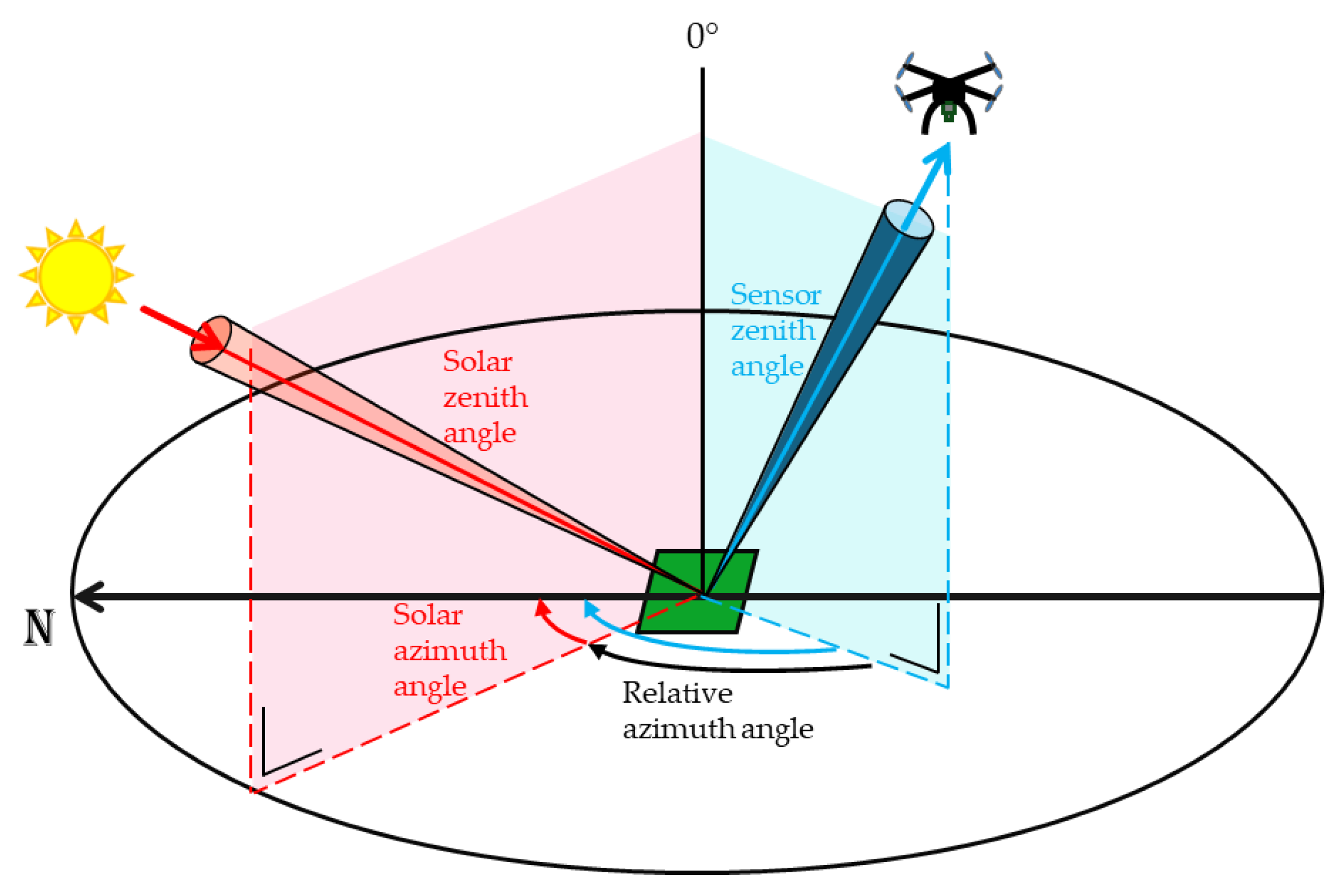

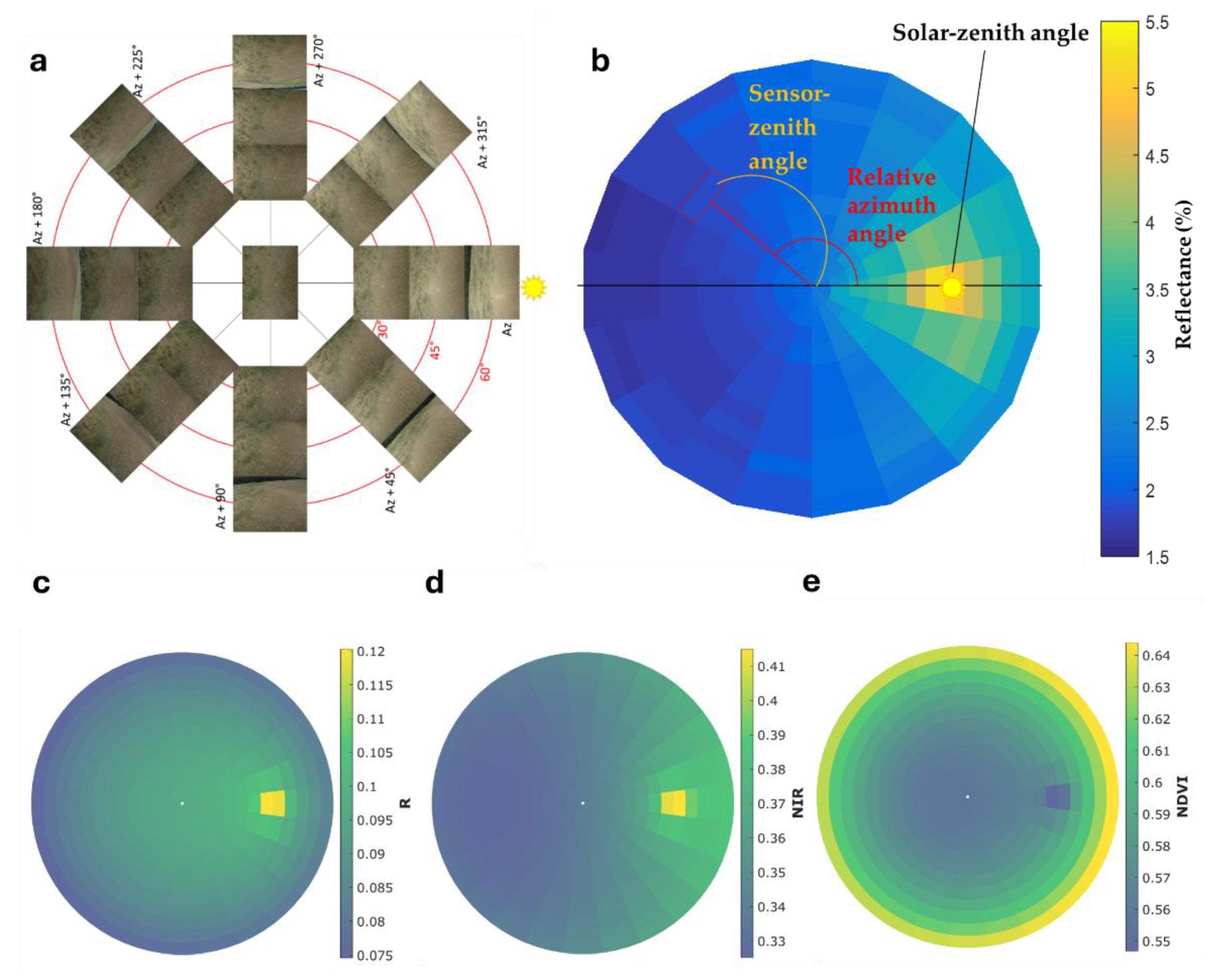

2. Sun-Sensor Geometry and BRDF

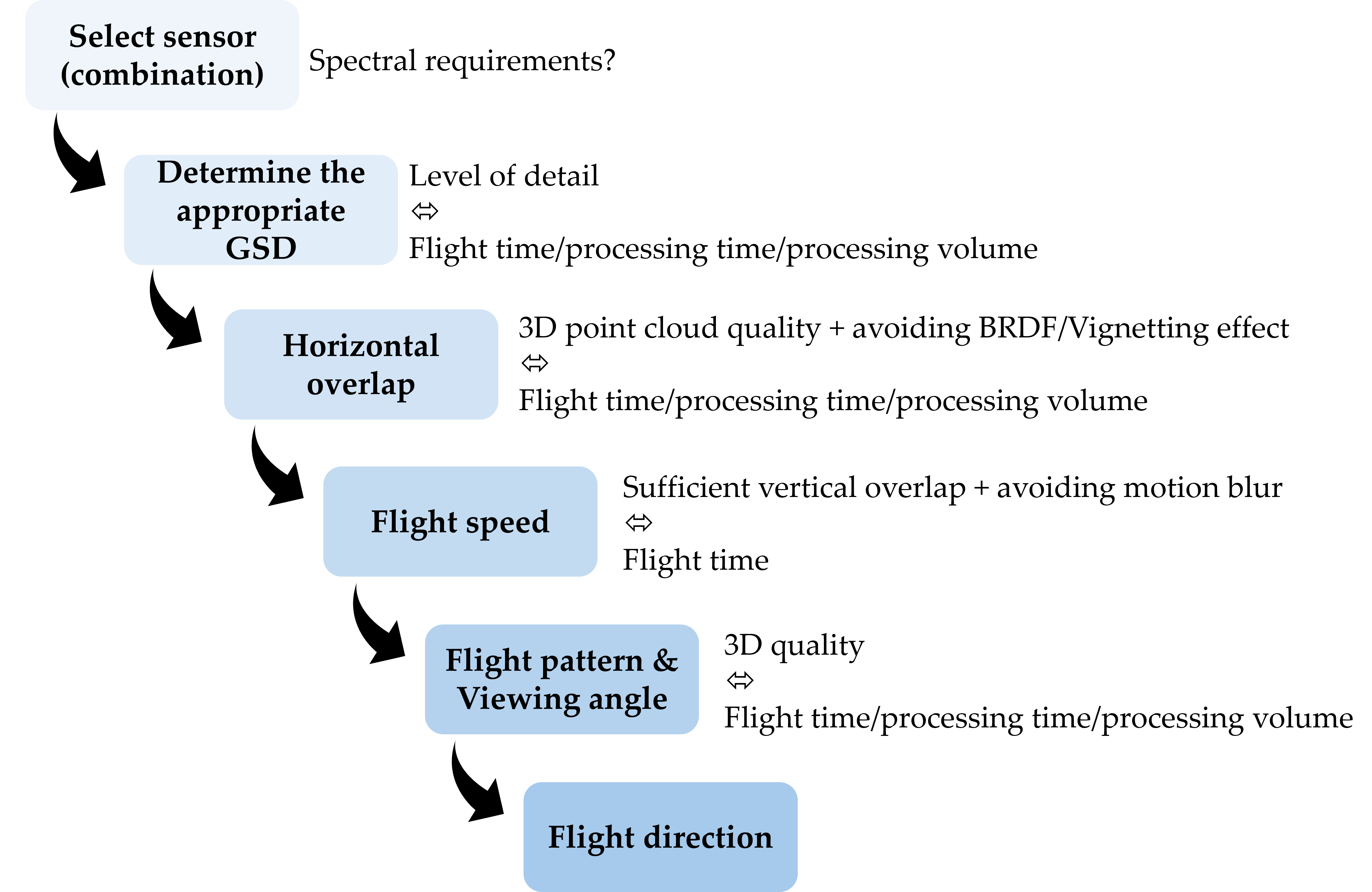

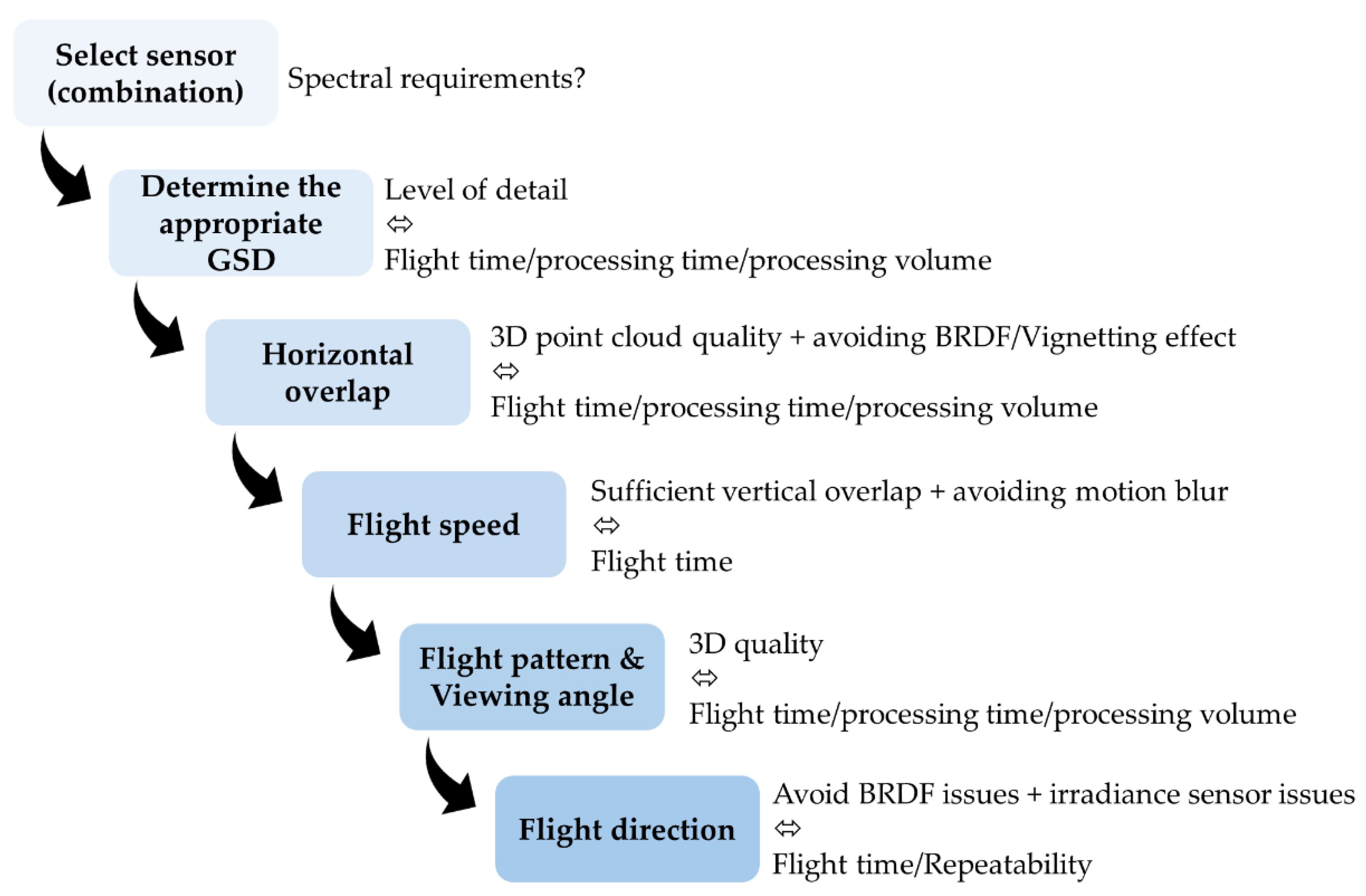

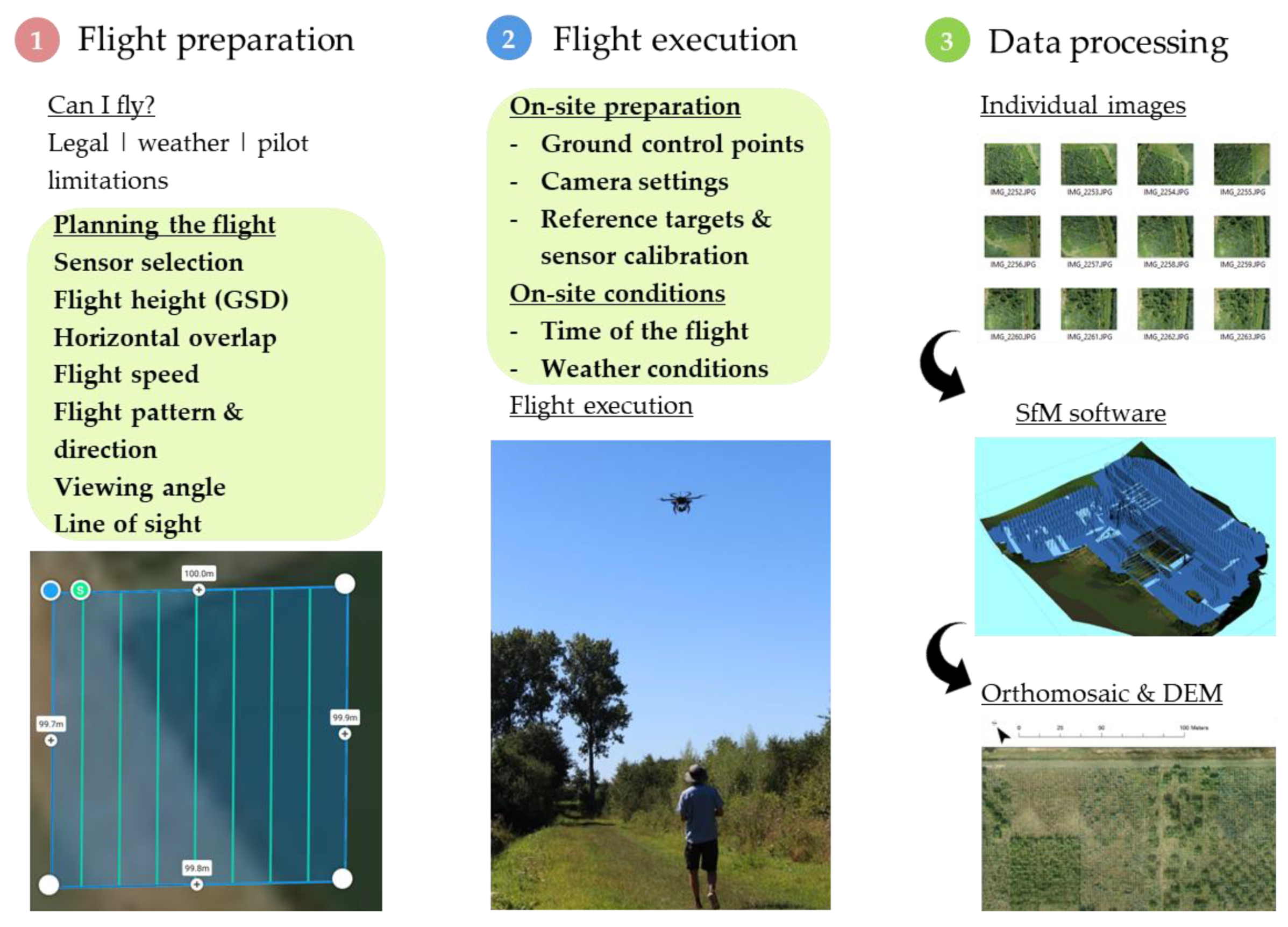

3. Flight Planning

3.1. Selection of Sensors and Lenses

- In general, ultra-wide focal length (<20mm) should be avoided due to significant distortion issues [32].

- Wide lenses (20-40mm) generally show superior photogrammetry results [32,33]. With terrestrial laser scans as reference, Denter et al. [32] compared various lenses for reconstructing a 3D forest scene and found that 21mm and 35mm lenses performed best, as they provided a better lateral view of tree crowns and trunks. Similar results were reported for thermal cameras [34]. On the other hand, the broad range of viewing angles capture within a single image can lead to bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) issues [25,26] (Section 2), requiring higher overlap (Section 3.3).

- Longer focal lengths (e.g., 50-100mm) produced poorer photogrammetry results than wide-angle cameras, but on the other hand show less distortion and enable lower ground sampling distances for resolutions in the sub-cm or sub-mm range (Section 3.2).

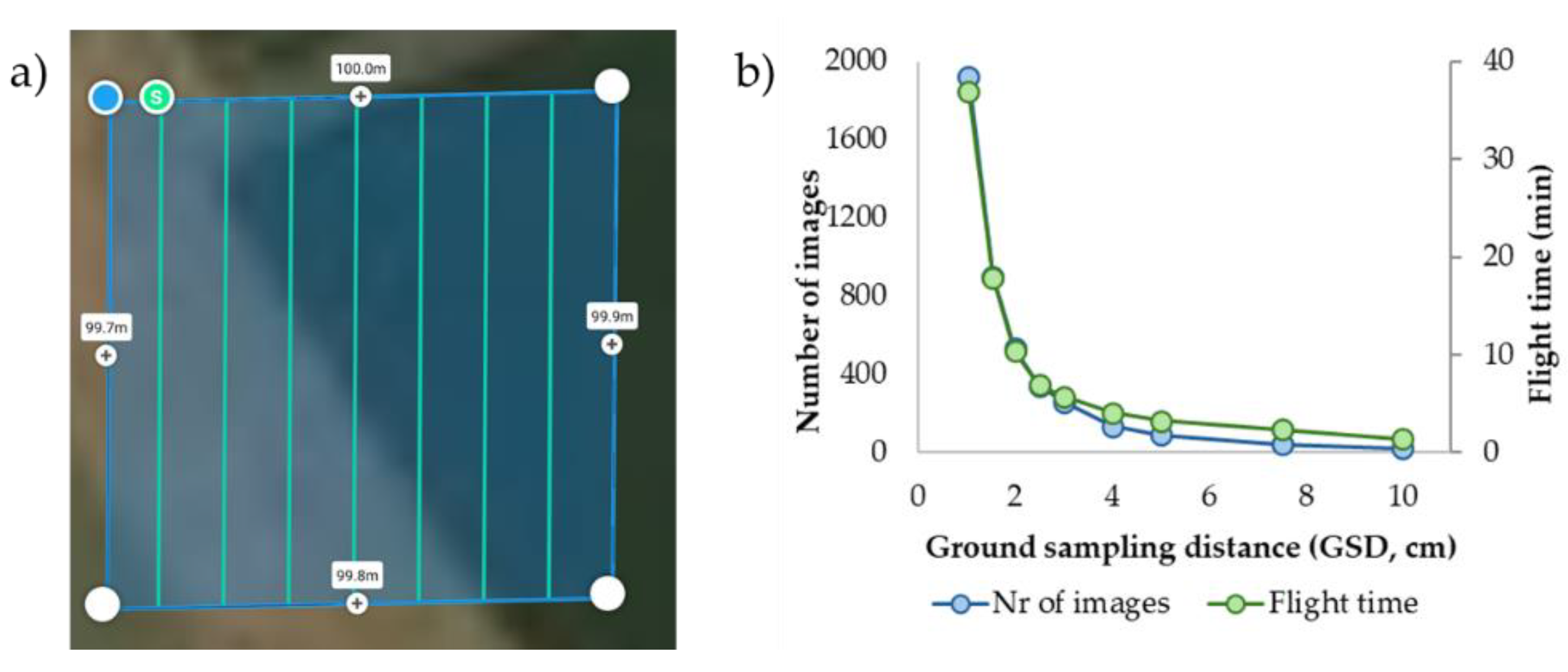

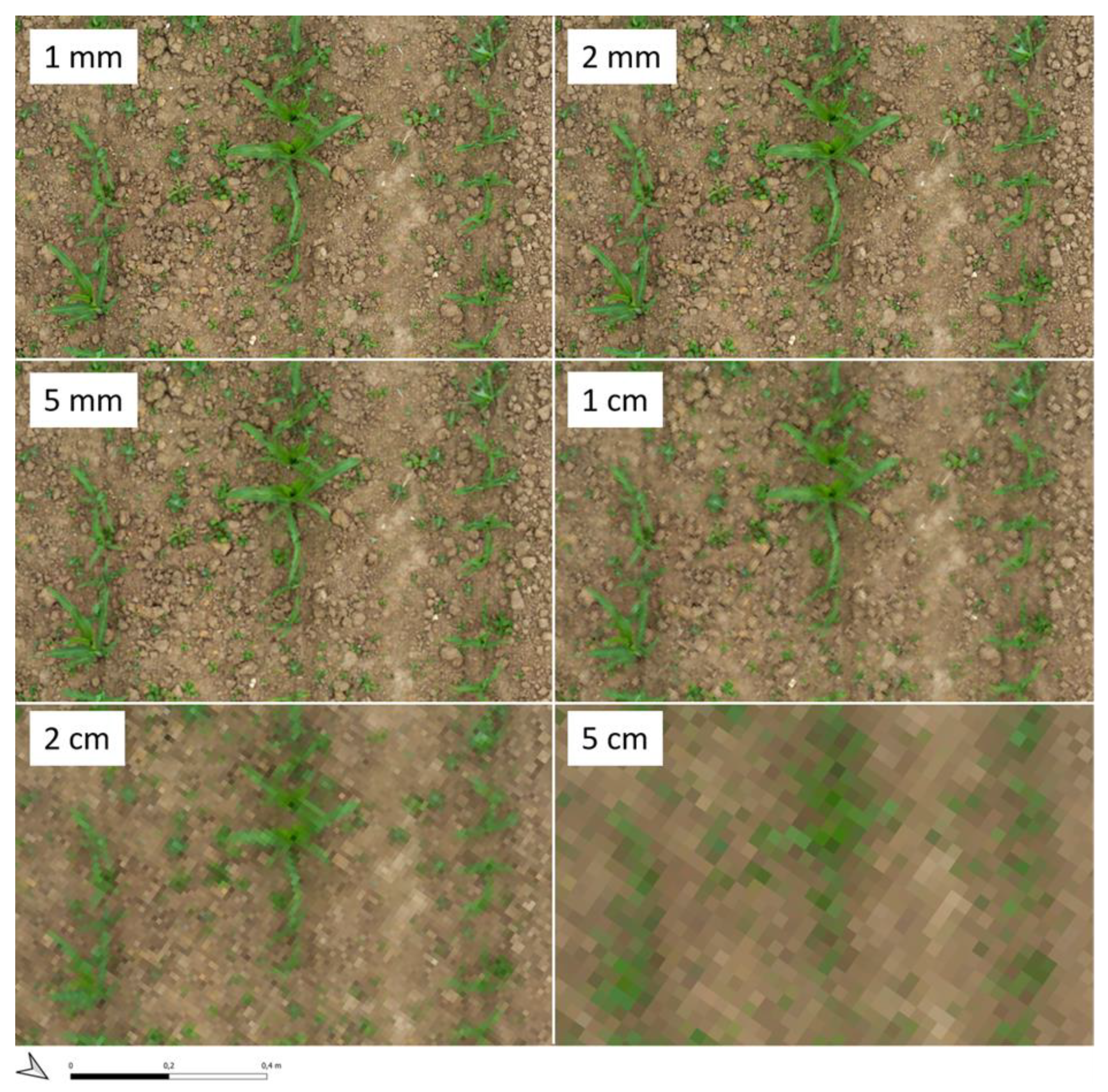

3.2. Ground Sampling Distance and Flight Height

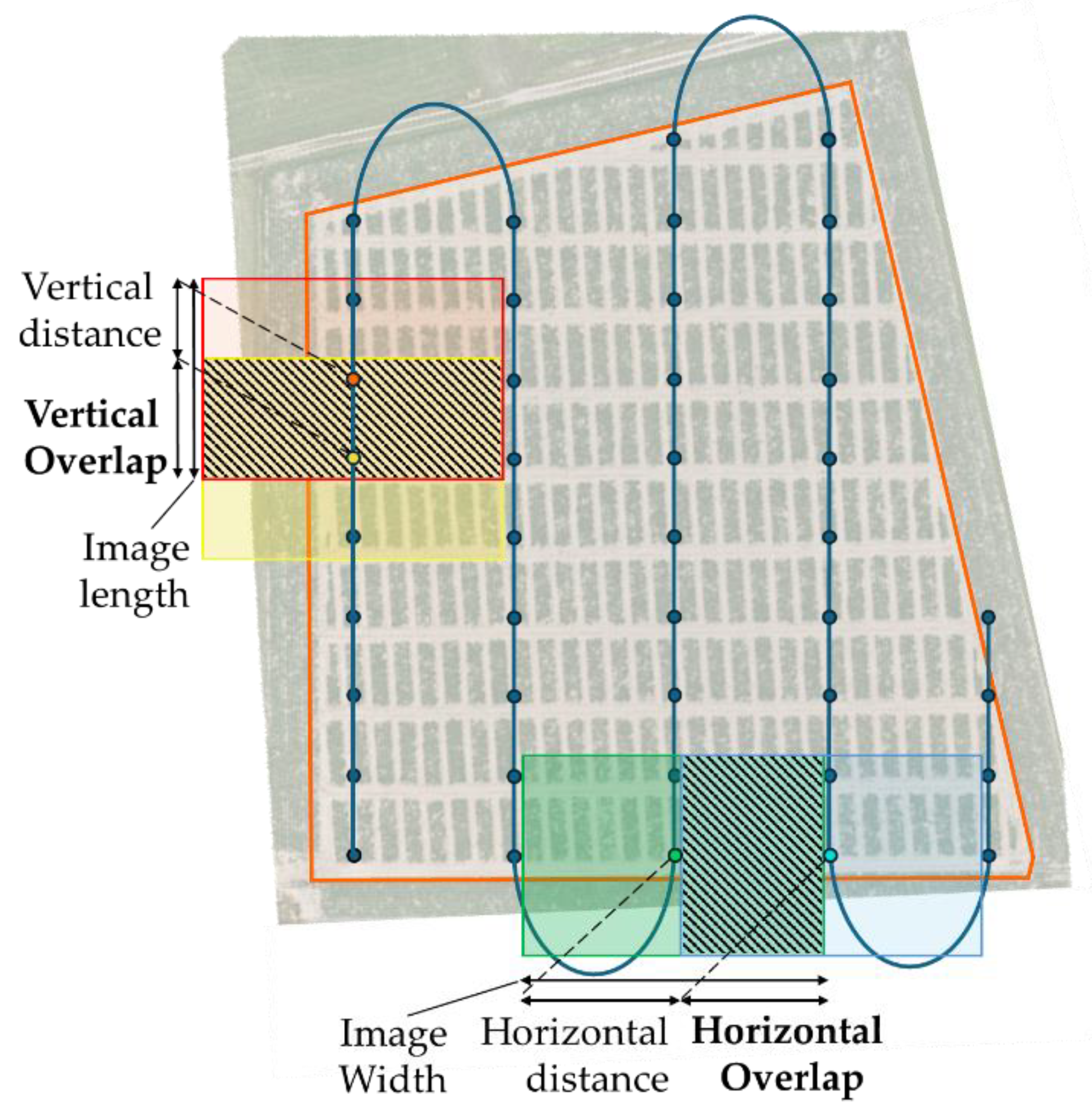

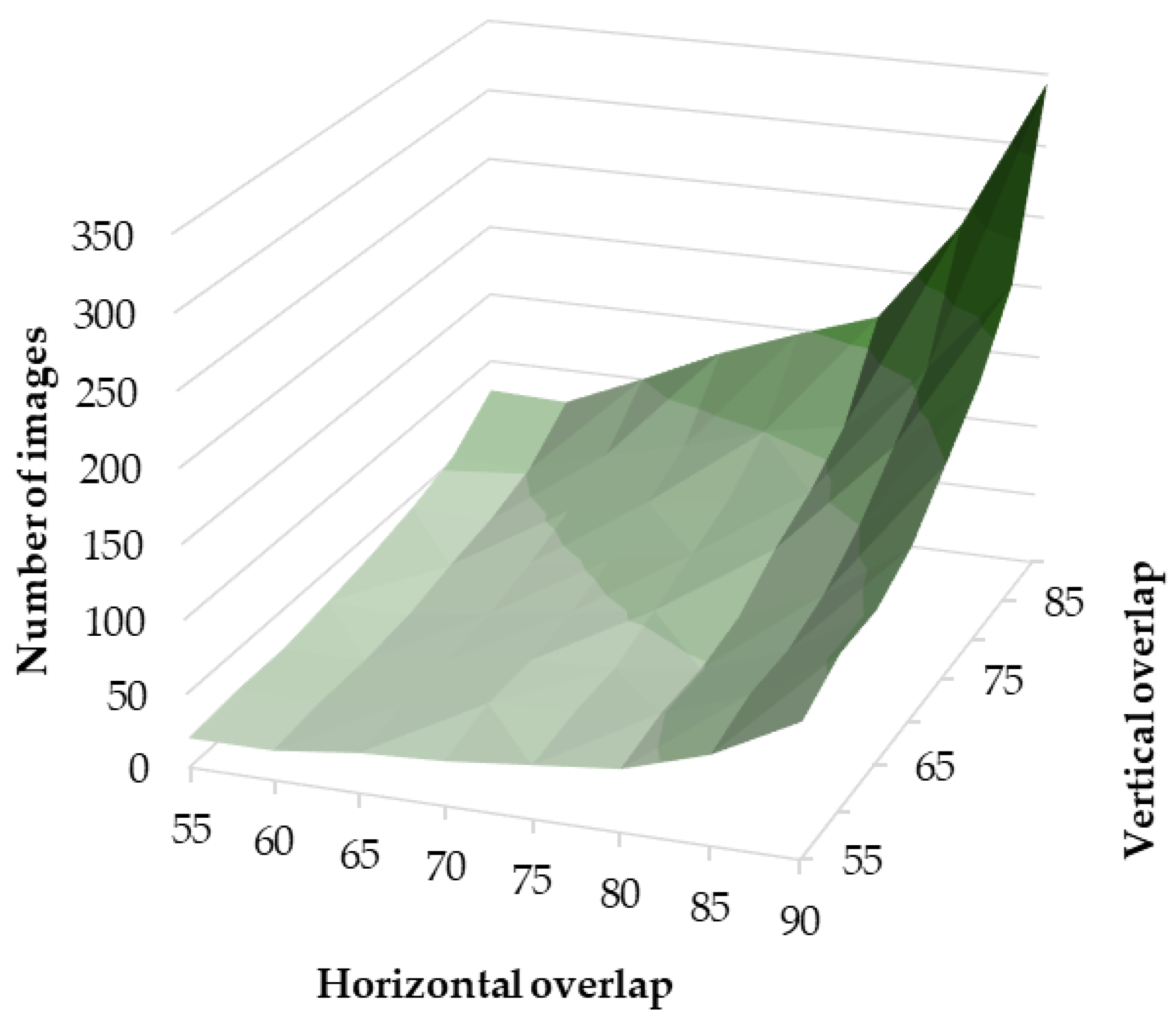

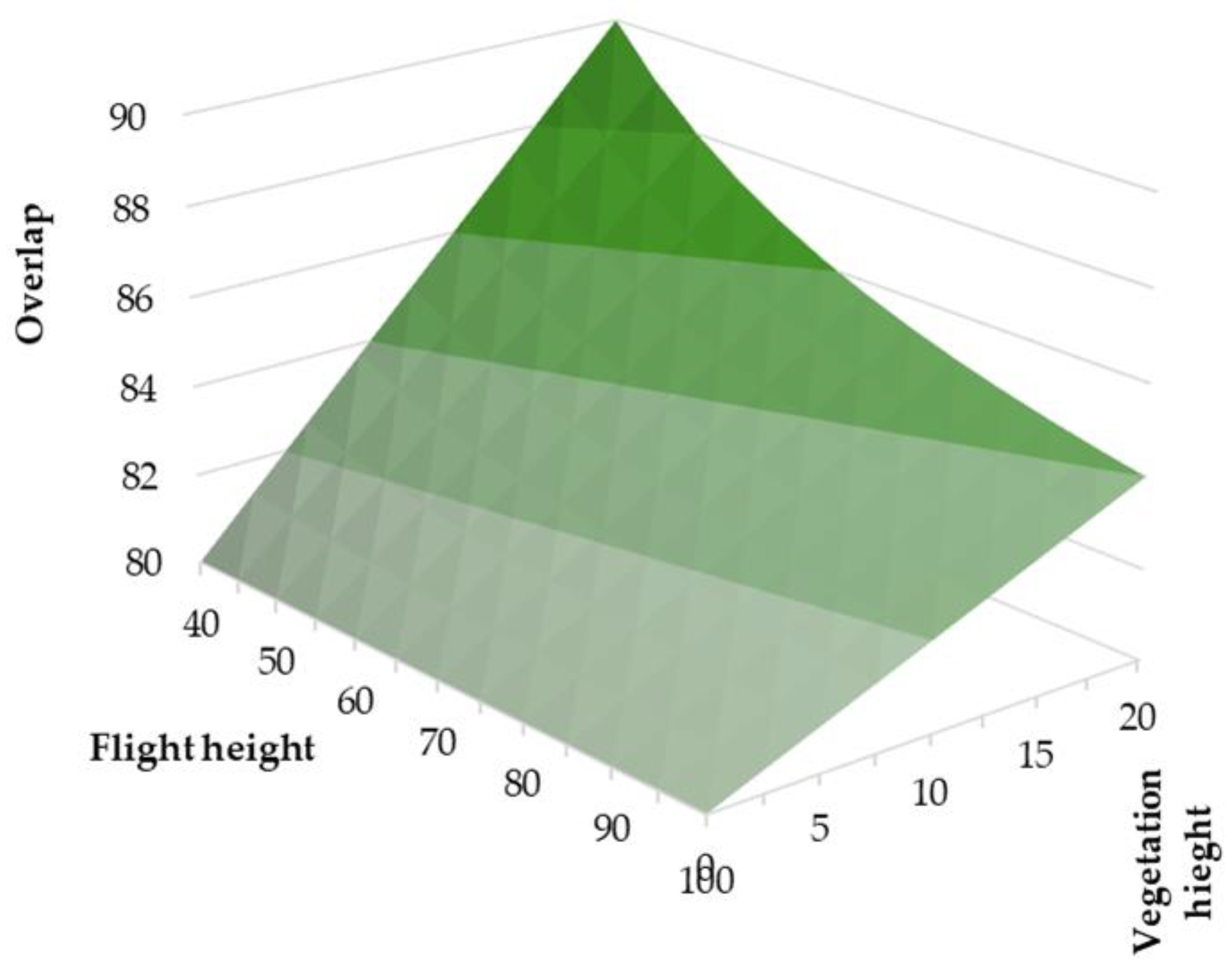

3.3. Overlap: Balancing Flight Time and Data Quality

3.4. Flight Speed

3.5. Flight Pattern and Flight Direction

3.6. Viewing Angle

3.7. Line of Sight Limitation: How Far Can You See a UAV?

4. Flight Execution: Ensuring Safe Flights at Best Quality

4.1. Weather Conditions and Their Impact on UAV Mapping Flights

4.1.1. Illumination

4.1.2. Wind Speed and Air Temperature

4.2. Time of the Flight

4.3. Ground Control Points

- Minimum requirements: A minimum of five GCPs is required for successful georeferencing [79,128]. For larger areas or areas with complex terrain, additional GCPs are needed [129], in particular to attain high vertical accuracy [130]. The optimal GCP density ultimately depends on the desired accuracy and the complexity of the relief [79].

- Optimal Distribution: The spatial arrangement of GCPs is as critical as their quantity [125,130]. They should cover the entire survey area, ideally distributed stratified or along the field edges [130]. For a minimal setup of five GCPs, a quincunx (die-like) arrangement is recommended [125]. GCPs near edges should be positioned to ensure they are captured by multiple camera views, and GCPs should not be placed too close to each other, as this can complicate manual matching in SfM software, potentially degrading referencing accuracy.

4.4. Camera Set-Up and Camera Settings

4.5. Reference Measurements and Targets

- Very dark panel, as dark as possible (ideally, about 1% reflectance): A very dark panel is important as reflectance of vegetation and water in most visible spectra is very low (2-4%), and, ideally, the reference panel should have still lower reflectance.

- Medium dark panels: Dark grey (8-10%) and medium-grey (15-20%): It is important to include panels within this range, because of its relevance in the visual regions, because some multispectral cameras tend to saturate over brighter panels when positioned in an otherwise darker surroundings (such as vegetation or soil), particularly for the visible bands. Including this range of panels still facilitates the ELM method for all channels.

- Bright grey panel: 60-75% reflectance: To include brighter areas, and particularly to correctly estimate reflectance of vegetation in the near-infrared.

- The absolute accuracy of a thermal camera is limited. Similar to the ELM of reflectance measurements, cold and warm reference panels with known temperatures can be used to linearly correct the brightness temperature of the image [24,124,138,139]. Typically, (ice-cold) water is used, or very bright (low temperature) and dark (high temperature) reference panels. Han et al. [140] constructed special temperature-controlled reference targets.

- For research on drought stress or evapotranspiration of terrestrial ecosystems, surface temperature is usually expressed as a thermal index, similar to the vegetation indices for reflectance measurements [104]. The most common index, the crop water stress index CWSI [141,142], uses the lowest and highest possible temperature that the vegetation can attain in the given conditions. These temperatures should not be confounded with the low and high temperature panels for the thermal accuracy correction, since it is crucial that these panels correspond to temperatures of the actual vegetation [143,144]. A common reference target is to use a wet cloth as cold reference temperature, as it transpires at maximal rate and essentially provides the wet bulb temperature [124,145,146]. However, it doesn’t accurately represent the canopy conditions [144,147]. Maes et al. [144] showed that artificial leaves made of cotton, remaining wet by constantly absorbing water from a reservoir, gives a more precise estimate, but the scalability of this method to field level remains to be explored.

- Vignetting in thermal cameras can create temperature differences between the edges and the centre of the image of up to several degrees [24]. The non-uniformity correction (NUC, Section 4.4) is for some models not sufficient [24], in which case the vignetting can be quantified by taking a thermal image of a uniform blackbody [24,148]. However, this is not absolutely required, provided that a sufficiently high horizontal and vertical overlap are foreseen.

5. Discussion

Towards a Universal MAPPING protocol?

Is There an Alternative for the Tedious Flight Mapping and Processing?

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | https://digitalag.ucdavis.edu/decision-support-tools/when2fly. |

| 2 | https://www.tern.org.au/data-collection-protocols/. |

References

- Statista. Drones - Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/consumer-electronics/drones/worldwide (accessed on 06/11/2024).

- Maes, W.H.; Steppe, K. Perspectives for remote sensing with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in precision agriculture. Trends in Plant Science 2019, 24, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Shao, G. Drone remote sensing for forestry research and practices. Journal of Forestry Research 2015, 26, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, L.P.; Wich, S.A. Dawn of Drone Ecology: Low-Cost Autonomous Aerial Vehicles for Conservation. Tropical Conservation Science 2012, 5, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Xie, Y.; Huang, Y. UAVs as remote sensing platforms in plant ecology: review of applications and challenges. Journal of Plant Ecology 2021, 14, 1003–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesas-Carrascosa, F.-J.; Notario García, M.D.; Meroño de Larriva, J.E.; García-Ferrer, A. An Analysis of the Influence of Flight Parameters in the Generation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Orthomosaicks to Survey Archaeological Areas. Sensors 2016, 16, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepe, M.; Alfio, V.S.; Costantino, D. UAV Platforms and the SfM-MVS Approach in the 3D Surveys and Modelling: A Review in the Cultural Heritage Field. Applied Sciences-Basel 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Sam, L.; Akanksha; Martín-Torres, F.J.; Kumar, R. UAVs as remote sensing platform in glaciology: Present applications and future prospects. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 175, 196–204. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Choi, Y. Applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Mining from Exploration to Reclamation: A Review. Minerals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, W.S. Efficient structure from motion for large-scale UAV images: A review and a comparison of SfM tools. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 167, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglhaut, J.; Cabo, C.; Puliti, S.; Piermattei, L.; O'Connor, J.; Rosette, J. Structure from Motion Photogrammetry in Forestry: a Review. Current Forestry Reports 2019, 5, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.; Smith, M.J.; James, M.R. Cameras and settings for aerial surveys in the geosciences: Optimising image data. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 2017, 41, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, L.; Hund, A.; Aasen, H. PhenoFly Planning Tool: flight planning for high-resolution optical remote sensing with unmanned areal systems. Plant Methods 2018, 14, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assmann, J.J.; Kerby, J.T.; Cunliffe, A.M.; Myers-Smith, I.H. Vegetation monitoring using multispectral sensors — best practices and lessons learned from high latitudes. Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems 2019, 7, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tmušić, G.; Manfreda, S.; Aasen, H.; James, M.R.; Gonçalves, G.; et al. Current Practices in UAS-based Environmental Monitoring. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Roy, D.P.; Zhang, H.K. The incidence and magnitude of the hot-spot bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) signature in GOES-16 Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) 10 and 15 minute reflectance over north America. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 265, 112638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarbiglu, H.; Pourreza, A. Impact of sun-view geometry on canopy spectral reflectance variability. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2023, 196, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stow, D.; Nichol, C.J.; Wade, T.; Assmann, J.J.; Simpson, G.; Helfter, C. Illumination Geometry and Flying Height Influence Surface Reflectance and NDVI Derived from Multispectral UAS Imagery. Drones 2019, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovend'aerde, L. An empirical BRDF model for the Queensland rainforests. Ghent University, 2016.

- Bian, Z.; Roujean, J.-L.; Cao, B.; Du, Y.; Li, H.; Gamet, P.; Fang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Q. Modeling the directional anisotropy of fine-scale TIR emissions over tree and crop canopies based on UAV measurements. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 252, 112150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Roujean, J.L.; Lagouarde, J.P.; Cao, B.; Li, H.; Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Q. A semi-empirical approach for modeling the vegetation thermal infrared directional anisotropy of canopies based on using vegetation indices. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 160, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouarde, J.P.; Dayau, S.; Moreau, P.; Guyon, D. Directional Anisotropy of Brightness Surface Temperature Over Vineyards: Case Study Over the Medoc Region (SW France). IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2014, 11, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhan, W.; Tu, L.; Dong, P.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, C. Diurnal variations in directional brightness temperature over urban areas through a multi-angle UAV experiment. Building and Environment 2022, 222, 109408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Kljun, N.; Olsson, P.-O.; Mihai, L.; Liljeblad, B.; Weslien, P.; Klemedtsson, L.; Eklundh, L. Challenges and Best Practices for Deriving Temperature Data from an Uncalibrated UAV Thermal Infrared Camera. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, B.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Y. An analysis of the effect of the bidirectional reflectance distribution function on remote sensing imagery accuracy from Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems. In 7-10 June 2016, 2016; pp. 1342-1350. 10 June.

- Honkavaara, E.; Khoramshahi, E. Radiometric Correction of Close-Range Spectral Image Blocks Captured Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle with a Radiometric Block Adjustment. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, R.H.J.; Okole, N.; Steppe, K.; Van Labeke, M.-C.; Geedicke, I.; Maes, W.H. An applied framework to unlocking multi-angular UAV reflectance data: a case study for classification of plant parameters in maize (Zea mays). Precision Agriculture 2024, 25, 1751–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, H.; Honkavaara, E.; Lucieer, A.; Zarco-Tejada, P. Quantitative remote sensing at ultra-high resolution with uav spectroscopy: A review of sensor technology, measurement procedures, and data correction workflows. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-H.; Phinn, S.; Johansen, K.; Robson, A. Assessing Radiometric Correction Approaches for Multi-Spectral UAS Imagery for Horticultural Applications. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.; Burningham, H. Comparison of pre- and self-calibrated camera calibration models for UAS-derived nadir imagery for a SfM application. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 2019, 43, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, W.; Huete, A.; Steppe, K. Optimizing the processing of UAV-based thermal imagery. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denter, M.; Frey, J.; Kattenborn, T.; Weinacker, H.; Seifert, T.; Koch, B. Assessment of camera focal length influence on canopy reconstruction quality. ISPRS Open Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 6, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, K. Photogrammetry: geometry from images and laser scans; Walter de Gruyter: 2011.

- Sangha, H.S.; Sharda, A.; Koch, L.; Prabhakar, P.; Wang, G. Impact of camera focal length and sUAS flying altitude on spatial crop canopy temperature evaluation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 172, 105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, X.; He, Y.; Huang, H.; Luo, S. CFD simulation and measurement of the downwash airflow of a quadrotor plant protection UAV during operation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 201, 107286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Vijver, R.; Mertens, K.; Heungens, K.; Nuyttens, D.; Wieme, J.; Maes, W.H.; Van Beek, J.; Somers, B.; Saeys, W. Ultra-High-Resolution UAV-Based Detection of Alternaria solani Infections in Potato Fields. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J.; Nielsen, J.; Streibig, J.C.; Jensen, J.E.; Pedersen, K.S.; Olsen, S.I. Pre-harvest weed mapping of Cirsium arvense in wheat and barley with off-the-shelf UAVs. Precision Agriculture 2019, 20, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liao, W.; Nuyttens, D.; Lootens, P.; Vangeyte, J.; Pižurica, A.; He, Y.; Pieters, J.G. Fusion of pixel and object-based features for weed mapping using unmanned aerial vehicle imagery. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2018, 67, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, A.; Lottes, P.; Ispizua Yamati, F.R.; Baumgarten, S.; Wolf, N.A.; Stachniss, C.; Mahlein, A.-K.; Paulus, S. Automatic UAV-based counting of seedlings in sugar-beet field and extension to maize and strawberry. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 191, 106493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, H.; Flores-Magdaleno, H.; Khalil-Gardezi, A.; Ascencio-Hernández, R.; Tijerina-Chávez, L.; Vázquez-Peña, M.A.; Mancilla-Villa, O.R. Digital Count of Corn Plants Using Images Taken by Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Cross Correlation of Templates. Agronomy 2020, 10, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, D.; Li, C.Y. Weakly-supervised learning to automatically count cotton flowers from aerial imagery. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, H.; Yin, F.; Xi, L.; Qiao, H.; Ma, Z.; Shen, S.; Jiang, B.; Ma, X. Wheat ear counting using K-means clustering segmentation and convolutional neural network. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Gallego, J.A.; Lootens, P.; Borra-Serrano, I.; Derycke, V.; Haesaert, G.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Araus, J.L.; Kefauver, S.C. Automatic wheat ear counting using machine learning based on RGB UAV imagery. The Plant Journal 2020, 103, 1603–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieme, J.; Leroux, S.; Cool, S.R.; Van Beek, J.; Pieters, J.G.; Maes, W.H. Ultra-high-resolution UAV-imaging and supervised deep learning for accurate detection of Alternaria solani in potato fields. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogiannis, S.; Konstantinidou, M.; Tsioukas, V.; Pikridas, C. A Cloud-Based Deep Learning Framework for Downy Mildew Detection in Viticulture Using Real-Time Image Acquisition from Embedded Devices and Drones. Information 2024, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, C.; Landgraf, D.; Van der Maaten-Theunissen, M.; Biber, P.; Pretzsch, H. Robinia pseudoacacia L. Flower Analyzed by Using An Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallmann, J.; Schüpbach, B.; Jacot, K.; Albrecht, M.; Winizki, J.; Kirchgessner, N.; Aasen, H. Flower Mapping in Grasslands With Drones and Deep Learning. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gröschler, K.-C.; Muhuri, A.; Roy, S.K.; Oppelt, N. Monitoring the Population Development of Indicator Plants in High Nature Value Grassland Using Machine Learning and Drone Data. Drones 2023, 7, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, R. Mapping Tree Species Using Advanced Remote Sensing Technologies: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective. Journal of Remote Sensing 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-H.; Phinn, S.; Johansen, K.; Robson, A.; Wu, D. Optimising drone flight planning for measuring horticultural tree crop structure. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 160, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, E.; Seifert, S.; Vogt, H.; Drew, D.; van Aardt, J.; Kunneke, A.; Seifert, T. Influence of Drone Altitude, Image Overlap, and Optical Sensor Resolution on Multi-View Reconstruction of Forest Images. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, S.; Baret, F.; Dutartre, D.; Malatesta, G.; Héno, S.; Comar, A.; Weiss, M.; Maupas, F. Exploiting the centimeter resolution of UAV multispectral imagery to improve remote-sensing estimates of canopy structure and biochemistry in sugar beet crops. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Rezaei, E.E.; Nouri, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Yu, D.; Siebert, S. UAV Flight Height Impacts on Wheat Biomass Estimation via Machine and Deep Learning. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 7471–7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtar, R.; Suab, S.A.; Syukur, M.S.; Korom, A.; Umarhadi, D.A.; Yunus, A.P. Assessing the Influence of UAV Altitude on Extracted Biophysical Parameters of Young Oil Palm. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.; Raharjo, T.; McCabe, M.F. Using Multi-Spectral UAV Imagery to Extract Tree Crop Structural Properties and Assess Pruning Effects. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Ahmad, I.; Zhou, G.; Huo, Z. Estimation of Winter Wheat SPAD Values Based on UAV Multispectral Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.H.; Mishra, V.; Jain, K. High-resolution mapping of forested hills using real-time UAV terrain following. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2023, X-1/W1-2023, 665-671. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yao, X.; Li, R.; Zhou, Z.; Yao, C.; Ren, K. Quick Extraction of Joint Surface Attitudes and Slope Preliminary Stability Analysis: A New Method Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle 3D Photogrammetry and GIS Development. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M.H.; Ahmad, A.; Gulzar, Q. Impact of UAV Surveying Parameters on Mixed Urban Landuse Surface Modelling. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, D.; Ørka, H.O.; Næsset, E.; Kachamba, D.; Gobakken, T. Effects of UAV Image Resolution, Camera Type, and Image Overlap on Accuracy of Biomass Predictions in a Tropical Woodland. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Bento, N.; Araújo E Silva Ferraz, G.; Alexandre Pena Barata, R.; Santos Santana, L.; Diennevan Souza Barbosa, B.; Conti, L.; Becciolini, V.; Rossi, G. Overlap influence in images obtained by an unmanned aerial vehicle on a digital terrain model of altimetric precision. European Journal of Remote Sensing 2022, 55, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-de-Santiago, F.; Valderrama-Landeros, L.; Rodríguez-Sobreyra, R.; Flores-Verdugo, F. Assessing the effect of flight altitude and overlap on orthoimage generation for UAV estimates of coastal wetlands. Journal of Coastal Conservation 2020, 24, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandois, J.P.; Olano, M.; Ellis, E.C. Optimal Altitude, Overlap, and Weather Conditions for Computer Vision UAV Estimates of Forest Structure. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 13895–13920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, J.; López-Granados, F.; Borra-Serrano, I.; Peña, J.M.J.P.A. Assessing UAV-collected image overlap influence on computation time and digital surface model accuracy in olive orchards. 2018, 19, 115-133. [CrossRef]

- Malbéteau, Y.; Johansen, K.; Aragon, B.; Al-Mashhawari, S.K.; McCabe, M.F. Overcoming the Challenges of Thermal Infrared Orthomosaics Using a Swath-Based Approach to Correct for Dynamic Temperature and Wind Effects. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbrycht, R.; Więcek, B. New approach to thermal drift correction in microbolometer thermal cameras. Quantitative InfraRed Thermography Journal 2015, 12, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesch, R. Thermal remote sensing with UAV-based workflows. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W6, 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Sieberth, T.; Wackrow, R.; Chandler, J.H. Motion blur disturbs - The influence of motion-blurred images in photogrammetry. Photogrammetric Record 2014, 29, 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ban, Y.; Kim, C. Motion Blur Kernel Rendering Using an Inertial Sensor: Interpreting the Mechanism of a Thermal Detector. Sensors 2022, 22, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; El-Shazly, A.; Abed, F.; Ahmed, W. The Influence of Flight Direction and Camera Orientation on the Quality Products of UAV-Based SfM-Photogrammetry. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigi, P.; Rajabi, M.S.; Aghakhani, S. An Overview of Drone Energy Consumption Factors and Models. In Handbook of Smart Energy Systems, Fathi, M., Zio, E., Pardalos, P.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, L.; Eeckhout, E.; Wieme, J.; Dejaegher, Y.; Audenaert, K.; Maes, W.H. Identifying the Optimal Radiometric Calibration Method for UAV-Based Multispectral Imaging. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, D.; Anderson, K. Investigating impacts of calibration methodology and irradiance variations on lightweight drone-based sensor derived surface reflectance products; SPIE: 2019; Volume 11149.

- Olsson, P.-O.; Vivekar, A.; Adler, K.; Garcia Millan, V.E.; Koc, A.; Alamrani, M.; Eklundh, L. Radiometric Correction of Multispectral UAS Images: Evaluating the Accuracy of the Parrot Sequoia Camera and Sunshine Sensor. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Huang, Y.; An, Z.; Zhang, H.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, F.; Zhang, C.; Hou, C. Assessing radiometric calibration methods for multispectral UAV imagery and the influence of illumination, flight altitude and flight time on reflectance, vegetation index and inversion of winter wheat AGB and LAI. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 219, 108821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, C.D. Estimation of the remote-sensing reflectance from above-surface measurements. Appl. Opt. 1999, 38, 7442–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Jiang, W.; Huang, W.; Yang, L. UAV-based oblique photogrammetry for outdoor data acquisition and offsite visual inspection of transmission line. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Jiang, M.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lin, J. Use of UAV oblique imaging for the detection of individual trees in residential environments. Urban forestry & urban greening 2015, 14, 404–412. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Zheng, G.; Antoniazza, G.; Zhao, F.; Chen, K.; Lu, W.; Lane, S.N. Improving UAV-SfM photogrammetry for modelling high-relief terrain: Image collection strategies and ground control quantity. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 2023, 48, 2884–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, P.R.; Hugenholtz, C.H. Enhancing UAV–SfM 3D Model Accuracy in High-Relief Landscapes by Incorporating Oblique Images. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.M.; Dietenberger, S.; Nestler, M.; Hese, S.; Ziemer, J.; Bachmann, F.; Leiber, J.; Dubois, C.; Thiel, C. Novel UAV Flight Designs for Accuracy Optimization of Structure from Motion Data Products. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.R.; Robson, S.; d'Oleire-Oltmanns, S.; Niethammer, U. Optimising UAV topographic surveys processed with structure-from-motion: Ground control quality, quantity and bundle adjustment. Geomorphology 2017, 280, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mu, X.; Qi, J.; Pisek, J.; Roosjen, P.; Yan, G.; Huang, H.; Liu, S.; Baret, F. Characterizing reflectance anisotropy of background soil in open-canopy plantations using UAV-based multiangular images. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2021, 177, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Gong, H.-L.; Guo, L.-J.; Zou, H.-Y. An approach for reflectance anisotropy retrieval from UAV-based oblique photogrammetry hyperspectral imagery. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 102, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, H.; Burkart, A.; Bolten, A.; Bareth, G. Generating 3D hyperspectral information with lightweight UAV snapshot cameras for vegetation monitoring: From camera calibration to quality assurance. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2015, 108, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, A.; Aasen, H.; Alonso, L.; Menz, G.; Bareth, G.; Rascher, U. Angular dependency of hyperspectral measurements over wheat characterized by a novel UAV based goniometer. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 725–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosjen, P.P.J.; Brede, B.; Suomalainen, J.M.; Bartholomeus, H.M.; Kooistra, L.; Clevers, J.G.P.W. Improved estimation of leaf area index and leaf chlorophyll content of a potato crop using multi-angle spectral data – potential of unmanned aerial vehicle imagery. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2018, 66, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.W.; Jia, H.; Peng, L.; Gan, L. Line-of-sight in operating a small unmanned aerial vehicle: How far can a quadcopter fly in line-of-sight? Applied Ergonomics 2019, 81, 102898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.W.; Sun, C.; Li, N. Distance and Visual Angle of Line-of-Sight of a Small Drone. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASA. Guidelines for UAS operations in the open and specific category – Ref to Regulation (EU) 2019/947. 2024.

- Slade, G.; Anderson, K.; Graham, H.A.; Cunliffe, A.M. Repeated drone photogrammetry surveys demonstrate that reconstructed canopy heights are sensitive to wind speed but relatively insensitive to illumination conditions. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetila, E.C.; Machado, B.B.; Astolfi, G.; Belete, N.A.d.S.; Amorim, W.P.; Roel, A.R.; Pistori, H. Detection and classification of soybean pests using deep learning with UAV images. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 179, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Baum, A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Dam-Hansen, C.; Thorseth, A.; Bauer-Gottwein, P.; Bandini, F.; Garcia, M. Unmanned Aerial System multispectral mapping for low and variable solar irradiance conditions: Potential of tensor decomposition. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2019, 155, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, H.; Bolten, A. Multi-temporal high-resolution imaging spectroscopy with hyperspectral 2D imagers–From theory to application. Remote Sensing of Environment 2018, 205, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, D.; Bennie, J.; Anderson, K. Monitoring spring phenology of individual tree crowns using drone-acquired NDVI data. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 2021, 7, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Danielson, B.; Clare, S.; Koenig, S.; Campos-Vargas, C.; Sanchez-Azofeifa, A. Radiometric calibration assessments for UAS-borne multispectral cameras: Laboratory and field protocols. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2019, 149, 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Honkavaara, E.; Saari, H.; Kaivosoja, J.; Pölönen, I.; Hakala, T.; Litkey, P.; Mäkynen, J.; Pesonen, L. Processing and Assessment of Spectrometric, Stereoscopic Imagery Collected Using a Lightweight UAV Spectral Camera for Precision Agriculture. Remote Sensing 2013, 5, 5006–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, G.T.; Imai, N.N.; Tommaselli, A.M.G.; Honkavaara, E.; Näsi, R.; Moriya, É.A.S. Radiometric block adjustment of hyperspectral image blocks in the Brazilian environment. International journal of remote sensing 2018, 39, 4910–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Khan, H.A.; Kootstra, G. Improving Radiometric Block Adjustment for UAV Multispectral Imagery under Variable Illumination Conditions. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Kootstra, G.; Khan, H.A. The impact of variable illumination on vegetation indices and evaluation of illumination correction methods on chlorophyll content estimation using UAV imagery. Plant Methods 2023, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Cao, Z.; Peng, X. Impacts of Variable Illumination and Image Background on Rice LAI Estimation Based on UAV RGB-Derived Color Indices. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizel, F.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Bruzzone, L.; Pedersen, G.B.M.; Vilmundardóttir, O.K.; Falco, N. Simultaneous and Constrained Calibration of Multiple Hyperspectral Images Through a New Generalized Empirical Line Model. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2018, 11, 2047–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Li, X.; Gu, Y. An Illumination Estimation and Compensation Method for Radiometric Correction of UAV Multispectral Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, W.H.; Steppe, K. Estimating evapotranspiration and drought stress with ground-based thermal remote sensing in agriculture: a review. Journal of Experimental Botany 2012, 63, 4671–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, S.; Siegmann, B.; Thonfeld, F.; Muro, J.; Jedmowski, C.; et al. Land Surface Temperature Retrieval for Agricultural Areas Using a Novel UAV Platform Equipped with a Thermal Infrared and Multispectral Sensor. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.A.; Tarkalson, D.D.; Sharma, V.; Bjorneberg, D.L. Thermal Crop Water Stress Index Base Line Temperatures for Sugarbeet in Arid Western U.S. Agricultural Water Management 2021, 243, 106459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinzog, E.K.; Schlerf, M.; Kraft, M.; Werner, F.; Riedel, A.; Rock, G.; Mallick, K. Revisiting crop water stress index based on potato field experiments in Northern Germany. Agricultural Water Management 2022, 269, 107664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, A.M.; Anderson, K.; Boschetti, F.; Brazier, R.E.; Graham, H.A.; et al. Global application of an unoccupied aerial vehicle photogrammetry protocol for predicting aboveground biomass in non-forest ecosystems. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 2022, 8, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mount, R. Acquisition of through-water aerial survey images. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing 2005, 71, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keukelaere, L.; Moelans, R.; Knaeps, E.; Sterckx, S.; Reusen, I.; et al. Airborne Drones for Water Quality Mapping in Inland, Transitional and Coastal Waters—MapEO Water Data Processing and Validation. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfarkh, J.; Johansen, K.; Angulo, V.; Camargo, O.L.; McCabe, M.F. Quantifying Within-Flight Variation in Land Surface Temperature from a UAV-Based Thermal Infrared Camera. Drones 2023, 7, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Zhao, L.; Ren, P.; Wu, H.; Zhong, X.; Gao, M.; Nie, Z. An Enhanced Model for Obtaining At-Sensor Brightness Temperature for UAVs Incorporating Meteorological Features and Its Application in Urban Thermal Environment. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 105987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. Quantitative Remote Sensing: Fundamentals and Environmental Applications; CRC Press: 2024.

- McCoy, R.M. Field Methods in Remote Sensing; Guilford Publications: 2005.

- Román, A.; Heredia, S.; Windle, A.E.; Tovar-Sánchez, A.; Navarro, G. Enhancing Georeferencing and Mosaicking Techniques over Water Surfaces with High-Resolution Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Imagery. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tejero, I.F.; Costa, J.M.; Egipto, R.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Lima, R.S.N.; Lopes, C.M.; Chaves, M.M. Thermal data to monitor crop-water status in irrigated Mediterranean viticulture. Agricultural Water Management 2016, 176, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pou, A.; Diago, M.P.; Medrano, H.; Baluja, J.; Tardaguila, J. Validation of thermal indices for water status identification in grapevine. Agricultural Water Management 2014, 134, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirka, B.; Stow, D.A.; Paulus, G.; Loerch, A.C.; Coulter, L.L.; An, L.; Lewison, R.L.; Pflüger, L.S. Evaluation of thermal infrared imaging from uninhabited aerial vehicles for arboreal wildlife surveillance. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2022, 194, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, A.; Pinto, C.; Ortiz, J.; Flatt, E.; Silman, M. Flight speed and time of day heavily influence rainforest canopy wildlife counts from drone-mounted thermal camera surveys. Biodiversity and Conservation 2022, 31, 3179–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sângeorzan, D.D.; Păcurar, F.; Reif, A.; Weinacker, H.; Rușdea, E.; Vaida, I.; Rotar, I. Detection and Quantification of Arnica montana L. Inflorescences in Grassland Ecosystems Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Drone-Based Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Wang, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, X.; Lan, Y.; Zhao, G.; Sanchez-Azofeifa, A.; Laakso, K. Assessing the Operation Parameters of a Low-altitude UAV for the Collection of NDVI Values Over a Paddy Rice Field. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dering, G.M.; Micklethwaite, S.; Thiele, S.T.; Vollgger, S.A.; Cruden, A.R. Review of drones, photogrammetry and emerging sensor technology for the study of dykes: Best practises and future potential. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2019, 373, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perich, G.; Hund, A.; Anderegg, J.; Roth, L.; Boer, M.P.; Walter, A.; Liebisch, F.; Aasen, H. Assessment of Multi-Image Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Based High-Throughput Field Phenotyping of Canopy Temperature. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, G.; Modica, G. Applications of UAV Thermal Imagery in Precision Agriculture: State of the Art and Future Research Outlook. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, B.; Karki, S.; Regmi, P.; Dhami, D.S.; Thapa, S.; Panday, U.S. Analyzing the Effect of Distribution Pattern and Number of GCPs on Overall Accuracy of UAV Photogrammetric Results. In Cham, 2020//, 2020; pp. 339-354.

- Forlani, G.; Dall’Asta, E.; Diotri, F.; Cella, U.M.d.; Roncella, R.; Santise, M. Quality Assessment of DSMs Produced from UAV Flights Georeferenced with On-Board RTK Positioning. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkas, D. Assessment of GCP Number and Separation Distance for Small UAS Surveys with and without GNSS-PPK Positioning. Journal of Surveying Engineering 2019, 145, 04019007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöcker, C.; Nex, F.; Koeva, M.; Gerke, M. High-Quality UAV-Based Orthophotos for Cadastral Mapping: Guidance for Optimal Flight Configurations. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Kim, D.W.; Lee, E.J.; Son, S.W. Determining the Optimal Number of Ground Control Points for Varying Study Sites through Accuracy Evaluation of Unmanned Aerial System-Based 3D Point Clouds and Digital Surface Models. Drones 2020, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabo, C.; Sanz-Ablanedo, E.; Roca-Pardiñas, J.; Ordóñez, C. Influence of the Number and Spatial Distribution of Ground Control Points in the Accuracy of UAV-SfM DEMs: An Approach Based on Generalized Additive Models. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 59, 10618–10627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall, G.C.; Thomasson, J.A.; Yang, C.; Wang, T.; Han, X.; Sima, C.; Chang, A. Uncrewed aerial vehicle radiometric calibration: A comparison of autoexposure and fixed-exposure images. The Plant Phenome Journal 2023, 6, e20082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, V.; Thomasson, J.A.; Hardin, R.G.; Rajan, N.; Raman, R. Selection of appropriate multispectral camera exposure settings and radiometric calibration methods for applications in phenotyping and precision agriculture. The Plant Phenome Journal 2024, 7, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Hua, W. A Case Study of Vignetting Nonuniformity in UAV-Based Uncooled Thermal Cameras. Drones 2022, 6, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, J.A.J.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Suarez, L.; Fereres, E. Thermal and narrowband multispectral remote sensing for vegetation monitoring from an unmanned aerial vehicle. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2009, 47, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Mora, J.P.; Kalacska, M.; Soffer, R.J.; Lucanus, O. Comparison of Calibration Panels from Field Spectroscopy and UAV Hyperspectral Imagery Acquired Under Diffuse Illumination. In 11-16 July 2021, 2021; pp. 60-63.

- Wang, Y.; Kootstra, G.; Yang, Z.; Khan, H.A. UAV multispectral remote sensing for agriculture: A comparative study of radiometric correction methods under varying illumination conditions. Biosystems Engineering 2024, 248, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Gu, X.; Sun, Y.; Gao, H.; Tao, Z.; Shi, S. Comparing, validating and improving the performance of reflectance obtention method for UAV-Remote sensing. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 102, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhwal, M.; Sharda, A.; Sangha, H.S.; Merwe, D.V.d. Spatial corn canopy temperature extraction: How focal length and sUAS flying altitude influence thermal infrared sensing accuracy. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 209, 107812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Candón, D.; Virlet, N.; Labbé, S.; Jolivot, A.; Regnard, J.-L.J.P.A. Field phenotyping of water stress at tree scale by UAV-sensed imagery: new insights for thermal acquisition and calibration. 2016, 17, 786-800. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Thomasson, J.A.; Swaminathan, V.; Wang, T.; Siegfried, J.; Raman, R.; Rajan, N.; Neely, H. Field-Based Calibration of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Thermal Infrared Imagery with Temperature-Controlled References. Sensors 2020, 20, 7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idso, S.B.; Jackson, R.D.; Pinter, P.J.; Reginato, R.J.; Hatfield, J.L. Normalizing the stress-degree-day parameter for environmental variability. Agricultural Meteorology 1981, 24, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.D.; Idso, S.B.; Reginato, R.J.; Pinter, P.J. Canopy temperature as a crop water-stress indicator. Water Resources Research 1981, 17, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, W.H.; Achten, W.M.J.; Reubens, B.; Muys, B. Monitoring stomatal conductance of Jatropha curcas seedlings under different levels of water shortage with infrared thermography. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2011, 151, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, W.H.; Baert, A.; Huete, A.R.; Minchin, P.E.H.; Snelgar, W.P.; Steppe, K. A new wet reference target method for continuous infrared thermography of vegetations. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2016, 226–227, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meron, M.; Tsipris, J.; Charitt, D. Remote mapping of crop water status to assess spatial variability of crop stress. In Precision Agriculture. Proceedings of the 4th European conference on precision agriculture, Berlin, Germany, Stafford, J., Werner, A., Eds.; Academic Publishers: Wageningen, 2003; pp. 405-410.

- Möller, M.; Alchanatis, V.; Cohen, Y.; Meron, M.; Tsipris, J.; Naor, A.; Ostrovsky, V.; Sprintsin, M.; Cohen, S. Use of thermal and visible imagery for estimating crop water status of irrigated grapevine. Journal of Experimental Botany 2007, 58, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashar, A.; Jones, H. Infra-Red Thermography as a High-Throughput Tool for Field Phenotyping. Agronomy 2014, 4, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, B.; Johansen, K.; Parkes, S.; Malbeteau, Y.; Al-Mashharawi, S.; et al. A Calibration Procedure for Field and UAV-Based Uncooled Thermal Infrared Instruments. Sensors 2020, 20, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Keukelaere, L.; Moelans, R.; Knaeps, E. Mapeo-Water: Drone Data Processing into Water Quality Products. In 11-16 July 2021, 2021; pp. 7008-7010.

- Maes, W.H.; Huete, A.; Avino, M.; Boer, M.; Dehaan, R.; Pendall, E.; Griebel, A.; Steppe, K. Can UAV-based infrared thermography be used to study plant-parasite interactions between mistletoe and eucalypt trees? Remote Sensing 2019, Accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, D.M.; Rebetzke, G.J.; Jimenez-Berni, J.A.; James, R.A.; Condon, A.G.; et al. Methodology for High-Throughput Field Phenotyping of Canopy Temperature Using Airborne Thermography. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Wang, M.; Schirrmann, M.; Dammer, K.-H.; Li, X.; et al. Affordable High Throughput Field Detection of Wheat Stripe Rust Using Deep Learning with Semi-Automated Image Labeling. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 207, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymaekers, D.; Delalieux, S. UAV-Based Remote Sensing: Improve efficiency through sampling missions. In Köln, Germany, 30/09/2024, 2024.

| 3D model |

RGB (high resolution) |

Reflectance (multi-/ hyperspectral) |

Thermal | ||

| Terrain | Canopy | ||||

| Overlap | >70V, >50H | >80V, >70H* | >60V, >50H | >80V, >80H | >80V, >80H |

| Flight speed | Normal | Slow | Normal | Slow | |

| Pattern: grid? | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Flight direction | Standard | Standard | Perpendicular to sun** | Standard (?) | |

| Viewing angle | Include oblique | Nadir | Nadir | Nadir | |

| Height (m) | Diagonal size (m) | Maximum distance (Eq. 5) | Maximum distance (Eq. 6) | |

| DJI Mini4 | 0.064 | 0.213 | 56 | 90 |

| DJI Mavic 3 | 0.107 | 0.381 | 94 | 145 |

| DJI Phantom | 0.28 | 0.59 | 245 | 213 |

| DJI M350 | 0.43 | 0.895 | 379 | 313 |

| DJI M600 | 0.759 | 1.669 | 669 | 566 |

| 3D model | RGB | Reflectance | Thermal | ||

| Terrain | Canopy | (high resolution) | (multi-/hyperspectral) | ||

| Sunny conditions? | Not required | Less relevant | Preferable, but not required | Required | |

| Wind speed? | Not relevant | Low | Best low, but can be higher | Best low, but can be higher | Low |

| Time of flight | Not relevant | Less relevant | Solar noon (but avoid hot spot) | Solar noon (but avoid hot spot) | |

| GCP | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Reference targets | Not relevant | Grey panels recommended | Single or (better) multiple grey panels | Aluminium foil-covered panel + temperature panels (+ extreme temperature panels) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).