1. Introduction

Although Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is preventable, it still remains a challenge worldwide even in the era of antiretroviral therapy (ART), with a disease prevalence of 39.9 million affected persons [

1]. The virus attacks the immune system, probably due to the fact that chemokine receptors are also co-receptors for HIV entry into cells and can inhibit or enhance viral replication [

2]. This results in immune activation, and dysfunction or suppression of the immune system, with an increase in systemic inflammatory cytokine levels [

3],

Cytokines, which are dissolvable low molecular weight proteins produced by body cells, are mediators of the immune system, with a primary role of regulating inflammation in health and disease. Some of the cytokines that have shown direct correlation with diseases include Interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), Monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1 (MCP-1, also CCL2), and D-dimer. Diseases that have been correlated with these cytokines include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis [

4,

5,

6]. High expression of MCP-1 has also been reported in people with systemic and oral diseases including HIV and periodontal disease [

7,

8].

Though immune activation in HIV is not fully understood, one of the mechanisms by which immune activation is believed to occur, is when microbial products (in this case the HIV lentivirus) encased within macrophages/monocytes, cross the gut mucosa, enabling viral entry into systemic circulation. The microbial product is able to cross the gut mucosa because of depletion in gut CD4+ T lymphocyte cells within the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), the most abundant site of CD4+ T-cells in the body [

9,

10]. The entry of microbial products into systemic circulation, then results in release of proinflammatory cytokines and systemic immune activation, causing high systemic expression levels [

9].

ART therapy has been noted to decrease systemic cytokine levels [

11], as well as result in higher CD4+ T cell counts and low viral load [

3]. However, despite the effectiveness of ART, the virus remains persistent in the cellular environment, with continuing persistent inflammation and immune activation (PIIA). The mechanism by which this occurs though not fully understood, has been attributed to cytokine regulation [

12] and genetics [

11,

13,

14,

15].

PIIA has also been correlated with non-infectious comorbid conditions among people with HIV (PWH), with inflammatory biomarkers/cytokine levels reportedly higher among PWH when compared to people without HIV [

9,

14,

16]. However, there is limited, if any literature, comparing 2 groups of PWH, with (PWH +NCD) and without (PWH -NCD) comorbid conditions.

PIIA is assessed by measuring cytokine levels in biological fluids like plasma, sweat and serum [

17,

18]. Cytokine levels can therefore be used to monitor the immune status of patients with chronic diseases, like cardiovascular disease, HIV, depression, hyper-lipidemia, etc. [

17].

Most studies on inflammatory cytokine analysis for systemic diseases use plasma or serum, or both fluids. However, for clinical and translational studies with cost constraints and multiple sample types available for testing for the same analytes to make clinical correlates, it may become necessary to choose only one sample type/biologic fluid that gives the best results.

This pilot study was designed with an objective to compare the absolute concentration levels of cytokines in both serum and plasma of PWH on ART with and without comorbid conditions (+NCD and -NDC respectively), with a goal to determine if plasma or serum is the preferred blood sample type for determination of cytokine levels, and to compare cytokine concentration in those with and without NCD.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB). Patient informed consent was obtained, and the study was conducted according to the ethical principles and standards in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Medical history, demographic information including biological sex, age and race were obtained from the first fourteen participants enrolled in an ongoing prospective longitudinal clinical and translational study titled ‘The Impact of Oral Health on Metabolism and Persistent Inflammation in HIV Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy (OHART) [

16].

Medical history for NCDs included in this analysis were cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, psychiatric conditions, and hyperlipidemia. These NCDs were diagnosed by physicians and obtained from electronic medical records and are systemic outcomes the OHART study focuses on. Psychiatric conditions included depression and anxiety only. Participants were divided into two groups: 1) those that presented with at least one of the above NCDs (+NCD) and 2) those that did not have any NCDs (-NCD). Paired serum and plasma levels were obtained via venipuncture from each participant. Plasma and serum sample preprocessing was conducted by centrifuging samples at 1000g for 15mins at room temperature. Plasma samples were pre-processed within 30 minutes of collection while serum samples were pre-processed within 30-60 minutes. Aliquots of 100μl and 1000μl supernatants were stored at -80 ºC for batched processing [

16] and cytokine analysis.

Quantification of soluble immune mediators (IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, MCP-1, and TNFα) were measured in both serum and plasma, with Luminex kit “Milliplex Human Cytokine/Chemokine/Growth Factor Panel A” (Millipore Sigma, USA), Cat. No. HCY-TA-60K-07, QC Cat. No. HCYTA-6060-2). Luminex assay protocol for Millipore Sigma, HCYTA-60K Rev. 12/21 was performed according to manufacturer’s recommendation using “FLEXMAP 3D” instrument and “Luminex® xPONENT® 4.2; Bio-Plex Manager™ Software 6.1”. Samples were assessed in duplicate 25 µl samples including kit-specific standards S1-S7 based on five-fold dilution. Absolute cytokine concentrations were quantified including standard deviation. Averages of each duplicate samples were used in analysis. Percent Intra-assay coefficient of variation (% CV) was acceptable at less than 20%, with 24 of the 28 samples being in this range. Four samples had % CV >20% (20.47%, 27.77%, 28.69%, and 79.71%), three of which were plasma samples.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical data was compared with absolute values of immune mediators using descriptive statistics, Continuous variables were summarized by mean and standard deviation, while dichotomous variables were described using count and percentage. Pairwise Pearson correlation was assessed between each cytokine and each participant in the +/- NCD groups and two-sided t-test was used to assess significance. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All data analysis was performed with Excel v2410, (Build 18129.20158)

3. Results

3.1.1. Participant Characteristics

Study participants consisted of 14 PWH either with NCDs (+NCD = 9) or without NCD (-NCD = 5). The average age was 56.6 years (range 45-65 years) in the +NCD group compared to 51.8 years (range 32-70 years) in the -NCD group (

Table 1). Average CD4 cell count was 857.5 cells/mm3 in the +NCD group and 602.6 cells/mm3 in the -NCD group (

Table 1).

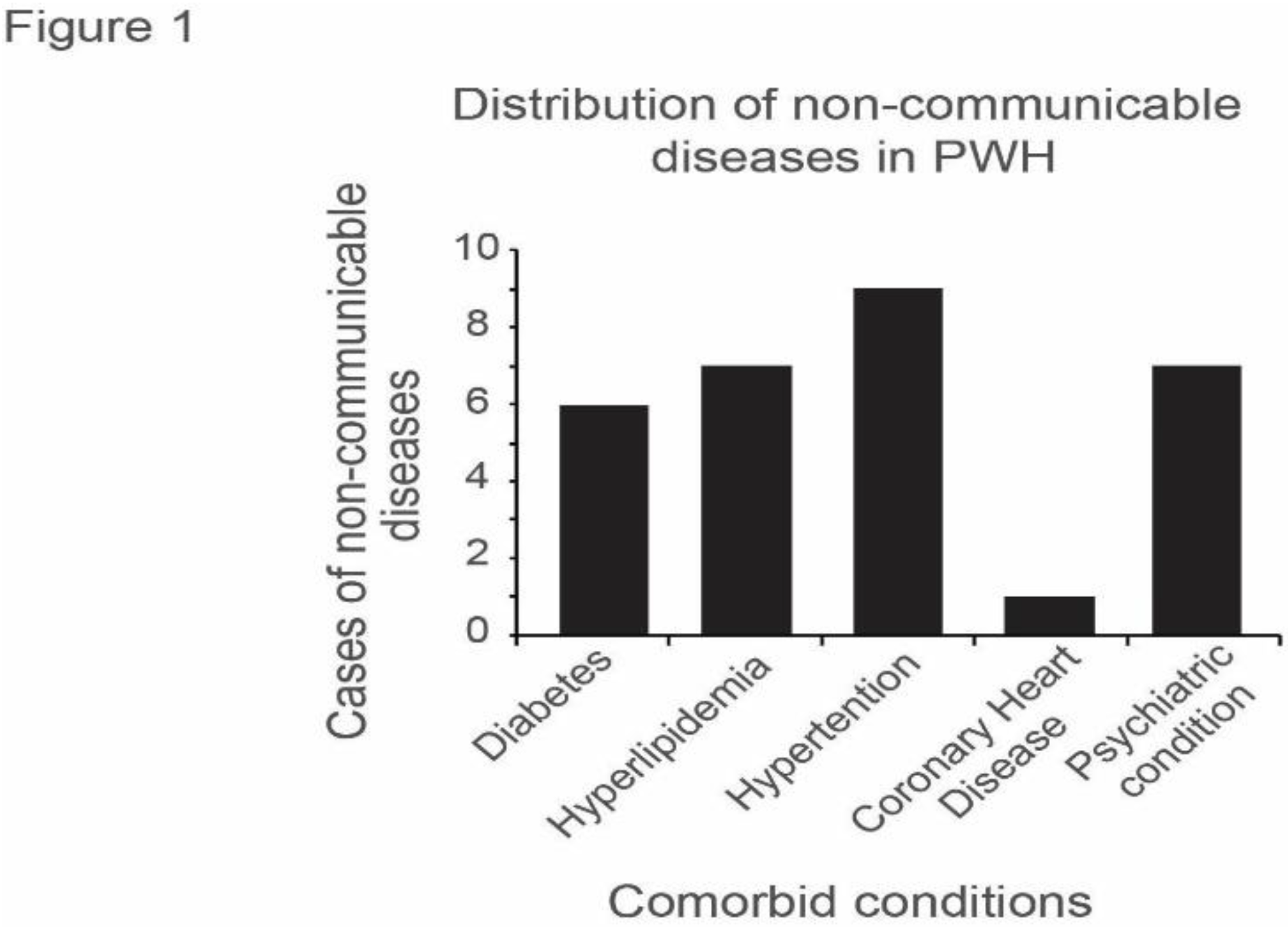

3.1.2. Distribution of Non-communicable Diseases in PWH

The distribution of NCDs showed that hypertension was the most common diagnosis among the five different comorbid conditions identified in n=9 cases with NCD (

Figure 1). However, some PWH presented with more than one comorbid condition.

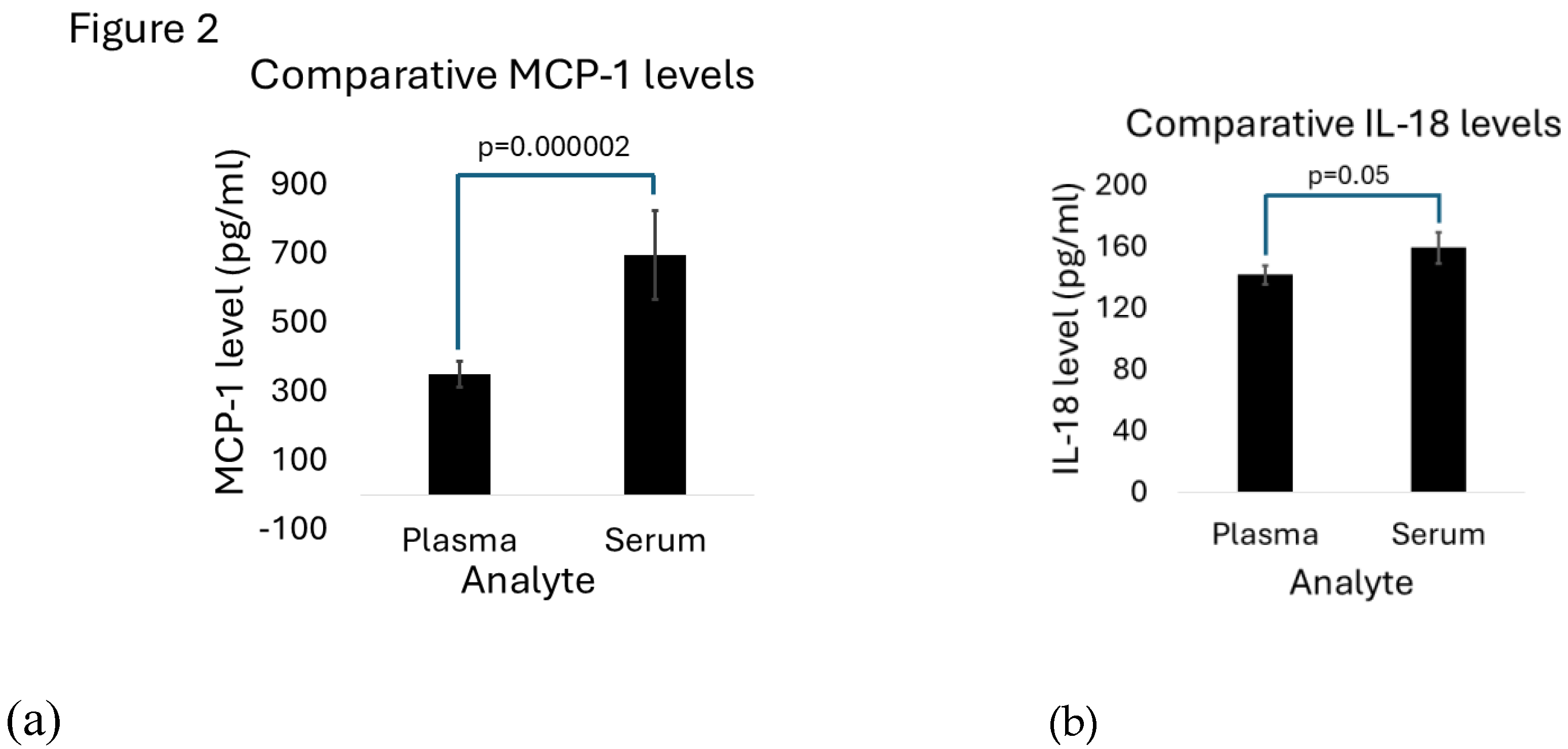

3.1.3. Elevated MCP-1 and IL-18 levels in serum and plasma of PWH

MCP-1 serum (694.60 pg/ml, SD 128.95) and plasma (349.87pg/ml (SD 37.91) expression levels were 4-188-fold and 2.5-140-fold higher, compared to other cytokines (

Table 2). MCP-1 serum levels were also significantly higher in serum (p= 0.000002) (

Figure 2A). IL-18 expression levels were also comparably high, though not as high as in MCP-1. IL-18 expression was also significantly higher in serum compared to plasma (159.33pg/ml SD 10.20 versus 141.81pg/ml SD 5.93; p=0.05) (

Figure 2B).

Serum and plasma levels of IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α were relatively lower (<40pg/ml) compared to MCP-1 and IL-8 (

Table 2), with similar patterns of higher analyte expression in serum. However, only IL-8 of the 3 analytes, showed a significantly higher serum level (7.96 pg/ml SD 0.49 versus 2.50pg/ml SD 0.11 in plasma; p=0.000005) (Table2).

3.1.4. IL-6 level in PWH with NCD is significantly higher than in those without NCD

A significant difference was noted in IL-6 expression in the group of PWH with +NCD compared to -NCD group (p=0.0489 in serum and p=0.0495 in plasma), with serum levels of 4.94pg/ml (+NCD)versus 1.58pg/ml (-NCD) and plasma levels of 4.40pg/ml (+NCD) versus 1.93pg/ml (-NCD). The pattern of higher IL-6 expression in each +NCD type considered was also noted when comparing each disease with those without the disease (e.g. PWH with hypertension versus those without hypertension (

Table 3).

Though IL-6 expression levels are very low compared to most of the other analyzed analytes except for IL-8, other analytes did not show any significant differences when comparing groups of those with and without NCDs. When each of the +NCDs was analyzed against those without the same disease.

4. Discussion

This study describes the pilot analysis of serum and plasma samples from PWH on ART with and without comorbid conditions. Th goal was to compare absolute concentration of inflammatory cytokines in serum and plasma of PWH on ART, to determine the more viable biological fluid for evaluating analytes of PIIA, as well as to compare cytokine concentration in those with and without NCD (+NCD and -NCD respectively). Our results showed that the choice of biological fluid was dependent on the analyte of interest. More remarkably, we noted elevated expression levels of MCP-1 in PWH, making MCP-1(also known as CCL2) and IL-18 possiblediagnostic and precision medicine intervention targets and IL-6 as a possible predictor of comorbidity in PWH on ART irrespective of whether serum or plasma is the analyte of choice.

The demographic profile of the participants aligned with that of Greater Philadelphia area residents, with majority of enrolled participants being males of African American decent. This is comparable to the 2021 data for PWH in Philadelphia, which shows that 63.7% of the population are of African-American origin, and 72.2% were males [

19]. The age group trend among participants included on this study was also comparable with the population of PWH in Philadelphia with an average age of 54.6 years noted in our population, and majority of the population of patients with HIV in Philadelphia in the 45-59 years age group [

19].

When we compared the 2 study groups, categorized based on presence or absence of NCDs, we noted that average age was higher in the +NCD group. This is expected, as comorbidities tend to increase with age, and as PWH are living longer, a similar trend is expected [

20]. It is important to note that comorbid conditions tend to occur at an earlier age among PWH, when compared with age- matched counterparts without HIV [

21].

Results on +NCD cases in this pilot study also showed that hypertension was the most common +NCD among our population of PWH, followed by hyperlipidemia and psychiatric conditions. This corroborates findings in literature of the prevalence of hypertension among PWH [

22]. Also important to note is that of the psychiatric conditions, depression was the most common (n=6) on our study, which is validated by findings in literature [

23,

24].

Cytokine expression levels of paired plasma and serum was compared in each individual and across the fourteen individuals. With regards to sample collection and processing, a recent study by Liu et al reports that with use of EDTA tubes for plasma sample collection, cytokine levels are very similar to those obtained with serum [

17]. This was mostly true for our study, where we noted no significant difference in analyte expression between most serum and plasma samples, except for MCP-1 and IL-8. The results obtained from our study are suggestive of the fact that the choice of plasma or serum for evaluation of PIIA among PWH, is dependent on the analyte that is being considered.

Of note is that there is an interaction between the immune and coagulation systems and plasma contains coagulation factors. It is therefore important to consider a possible interaction between coagulation proteins and plasma when considering the body fluid type for cytokine analysis.

Our findings of elevated MCP-1 levels corroborates with reports of elevated CCL2 in PWH despite ART, with this chemokine closely associated with prominent inflammation and immune activation in this population[

18]. For this reason, it has been suggested that the MCP-1 receptor is targeted for HIV- therapeutics.

Elevated IL-18 levels have also been associated with HIV-infection. However, most reports have associated elevated IL-18 with anti-retroviral treatment failure or comorbid conditions, such as lipodystrophy in PWH.[

19,

20,

21] This does not seem to be the case in this study, as most of our participants had good viremia control, and IL-18 levels were similar in those with and without NCDs.

The above study by Liu, also noted the importance of using EDTA tubes for plasma sample collection, as heparin and lithium heparin affects the concentration of the analytes. The study further emphasized the need for timely processing of plasma samples to obtain reliable results. In pre-processing samples for this pilot study, we ensured that EDTA tubes were used for all plasma sample collection, and obtained plasma samples were processed within less than 30 minutes of sample collection, while serum samples were processed after at least 30 minutes but not more than an hour after collection.

IL-6 is both a pro and anti-inflammatory cytokine, produced by CD4+ T-helper 2 cells [

25,

26], and is believed to activate immune response [

26,

27]. We noted higher expression levels of plasma and serum IL-6 in the +NCD group, with a high correlation noted between presence of NCDs (+NCD) and relatively higher expression of IL-6. This was especially significant for participants with hypertension and psychiatric conditions. Our study also noted a moderate correlation between serum IL-6 expression level and number of NCDs (ρ=0.63), alluding to the fact that IL-6 is a predictor of both presence and number of NCDs in PWH.

Based on findings on

Table 1, CD4+ T cell count was higher in patients with +NCD, and the maximum HIV RNA viral load was also lower in this group. This suggests that PWH with better control of their viral disease with higher CD4 and lower viral load are more likely to have NCDs. which is a likely pointer to the role of ART, in addition to the suspected role of PIIA in contribut

5. Conclusion

The findings on this pilot study suggest that the choice of plasma or serum for evaluation of PIIA among PWH, is dependent on the analyte being evaluated. We also observed that MCP-1 especially, and IL-18 are potential diagnostic markers for HIV even in PWH well controlled on ART. Finally, IL-6 may be used as possible predictors of comorbid conditions among PWH, but further studies using larger number of patients is needed to confirm these findings. It will be interesting to evaluate the role of cytokines in common oral diseases noted in PWH, in the ART era. In addition, compare blood and saliva cytokine levels, and correlate findings with oral disease manifestations like periodontal disease and changes in quality of saliva among PWH on ART.

The goal of future research is focused on evaluating the oral-systemic diseases link, and cytokine analysis of saliva and comparing with systemic cytokine levels, will and in the process be to discover the mechanisms underlying the development of oral and hopefully systemic diseases conditions in PWH. This will help guide with developing prevention strategies, as well as therapeutic targets that will help improve oral health and oral health quality of life, as well as systemic health, among PWH on ART.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O.; methodology, T.O and S.A.; software, D.S.; validation, T.O and S.A.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, A.K and L.V.; resources, T.O.; data curation, L.V,A. K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.O, S.A.; writing—review and editing, T.O, A.K, L.V, D.S, S.A.; visualization, T.O, S.A.; supervision, T.O.; project administration, T.O; funding acquisition, T.O, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research/National Institute of Health/DHHS, grant number R01-DE029648-01 and “The APC was funded by NIDCR”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The University of Pennsylvania (protocol code/#: 834892 and date of approval:13th of May, 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Written and signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the OHART study team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- World Health Organization, (WHO) HIV and AIDS. Newsroom factsheet detail 2023 [cited 2024 2/27/2024]; July 13 2023: [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids.

- Covino, D.A.; Sabbatucci, M.; Fantuzzi, L. The ccl2/ccr2 axis in the pathogenesis of hiv-1 infection: A new cellular target for therapy? Current Drug Targets 2016, 17, 76–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okay, G.; et al. The effect of antiretroviral therapy on IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ levels and their relationship with HIV-RNA and CD4+ T cells in HIV patients. Current HIV Research 2020, 18, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukwuanukwu, R.C.; et al. Evaluation of some immune and inflammatory responses in diabetes and HIV co-morbidity. Afr Health Sci 2023, 23, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Role of MCP-1 in cardiovascular disease: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009, 117, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connor, T.; Borsig, L.; Heikenwalder, M. CCL2-CCR2 Signaling in Disease Pathogenesis. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2015, 15, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradeep, A.R.; Daisy, H.; Hadge, P. Serum levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in periodontal health and disease. Cytokine 2009, 47, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanazawa, S.; et al. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) in adult periodontal disease: increased monocyte chemotactic activity in crevicular fluids and induction of MCP-1 expression in gingival tissues. Infect Immun 1993, 61, 5219–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashuro, A.A.; et al. The effect of protease inhibitors-based antiretroviral therapy on serum/plasma interleukin-6 levels among PLHIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2022, 94, 4669–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidya Vijayan, K.K.; et al. Pathophysiology of CD4+ T-Cell Depletion in HIV-1 and HIV-2 Infections. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.V.; et al. Systemic Inflammation, Coagulation, and Clinical Risk in the START Trial. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017, 4, ofx262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandergeeten, C.; Fromentin, R.; Chomont, N. The role of cytokines in the establishment, persistence and eradication of the HIV reservoir. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2012, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, W.; et al. Examining Chronic Inflammation, Immune Metabolism, and T Cell Dysfunction in HIV Infection. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.E.; Baker, J.V. Assessing inflammation and its role in comorbidities among persons living with HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2019, 32, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, T.R.; Landay, A.L.; Anzinger, J.J. Dysfunctional Immunometabolism in HIV Infection: Contributing Factors and Implications for Age-Related Comorbid Diseases. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2020, 17, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolehinwa, T.T.; et al. Oral health outcomes in an HIV cohort with comorbidities- implementation roadmap for a longitudinal prospective observational study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; et al. Cytokines: From Clinical Significance to Quantification. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2021, 8, e2004433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango Duque, G.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIDSVu, Local Data Philadelphia, E. University, Editor. 2024: AIDSVu is presented by Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in partnership with Gilead Sciences, Inc. and the Center for AIDS Research at Emory University (CFAR).

- Paudel, M.; et al. Comorbidity and comedication burden among people living with HIV in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin 2022, 38, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, R.A.; et al. Comorbidity is more common and occurs earlier in persons living with HIV than in HIV-uninfected matched controls, aged 50 years and older: A cross-sectional study. Int J Infect Dis 2018, 70, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todowede, O.O.; Mianda, S.Z.; Sartorius, B. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among HIV-positive and HIV-negative populations in sub-Saharan Africa-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2019, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; et al. Association between depression and HIV infection vulnerable populations in United States adults: a cross-sectional analysis of NHANES from 1999 to 2018. Front Public Health, 2023, 11, 1146318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuenmayor, A.; Cournos, F. Addressing depressive disorders among people with HIV. Top Antivir Med 2022, 30, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rose-John, S. Interleukin-6 signalling in health and disease. F1000Res 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheller, J.; et al. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1813, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliyu, M.; et al. Interleukin-6 cytokine: An overview of the immune regulation, immune dysregulation, and therapeutic approach. Int Immunopharmacol 2022, 111, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).