Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

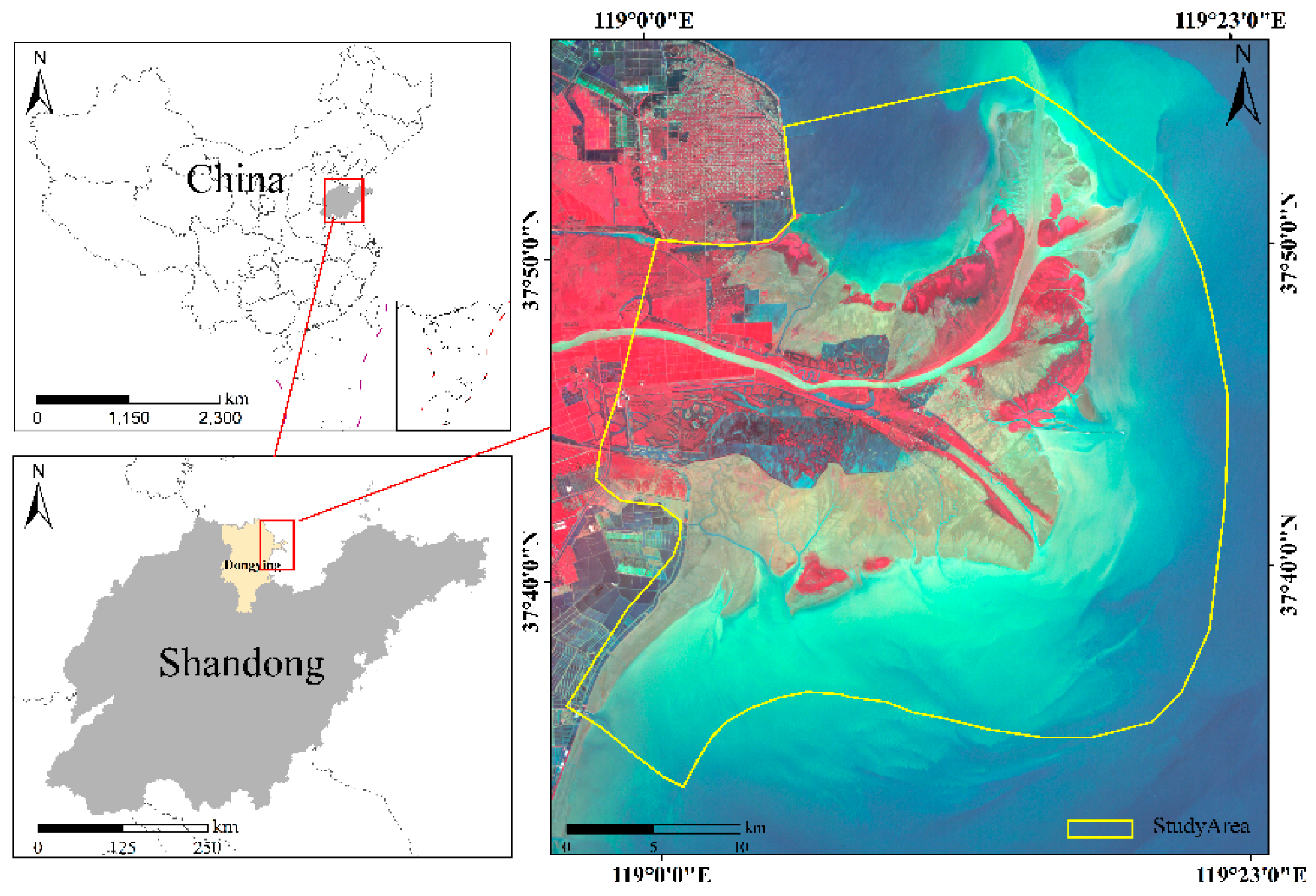

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Processing

| Satellite Name | Imaging Sensor | Spatial Resolution | Date/Time | Cloud( %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCM2 | CCD1 | 10m | 20190819 | 3% |

| HDM1 | COMS1 | 10m | 20200930 | 1% |

| HEM1 | CMOS2 | 10m | 20210908 | 8% |

| HFM1 | COMS2 | 10m | 20220724 | 4% |

| HAM2 | CMOS3 | 10m | 20230930 | 1% |

2.3. Methodology

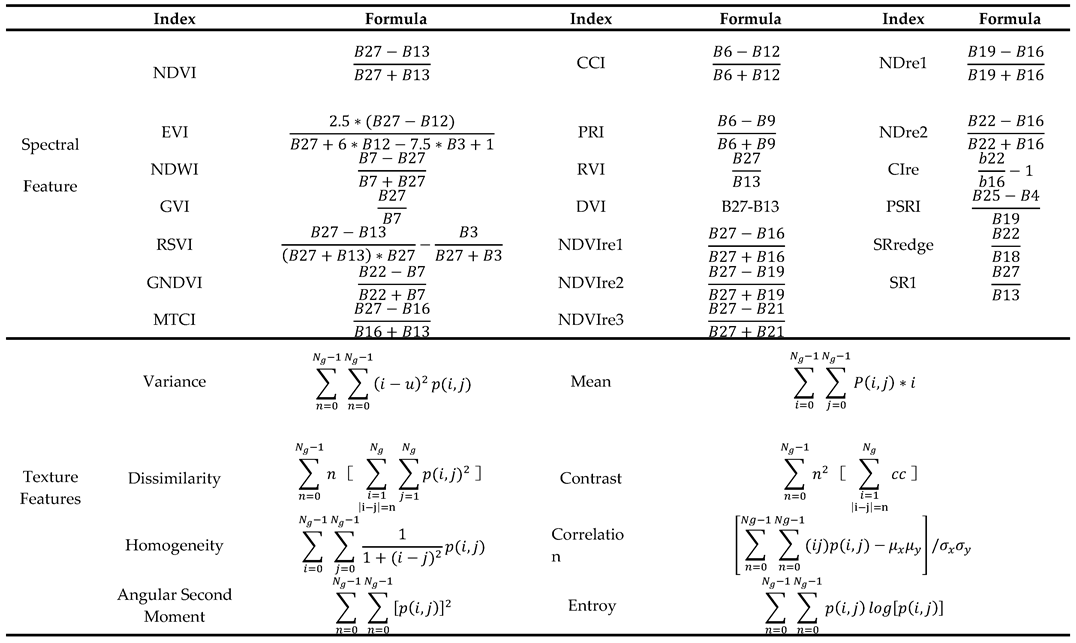

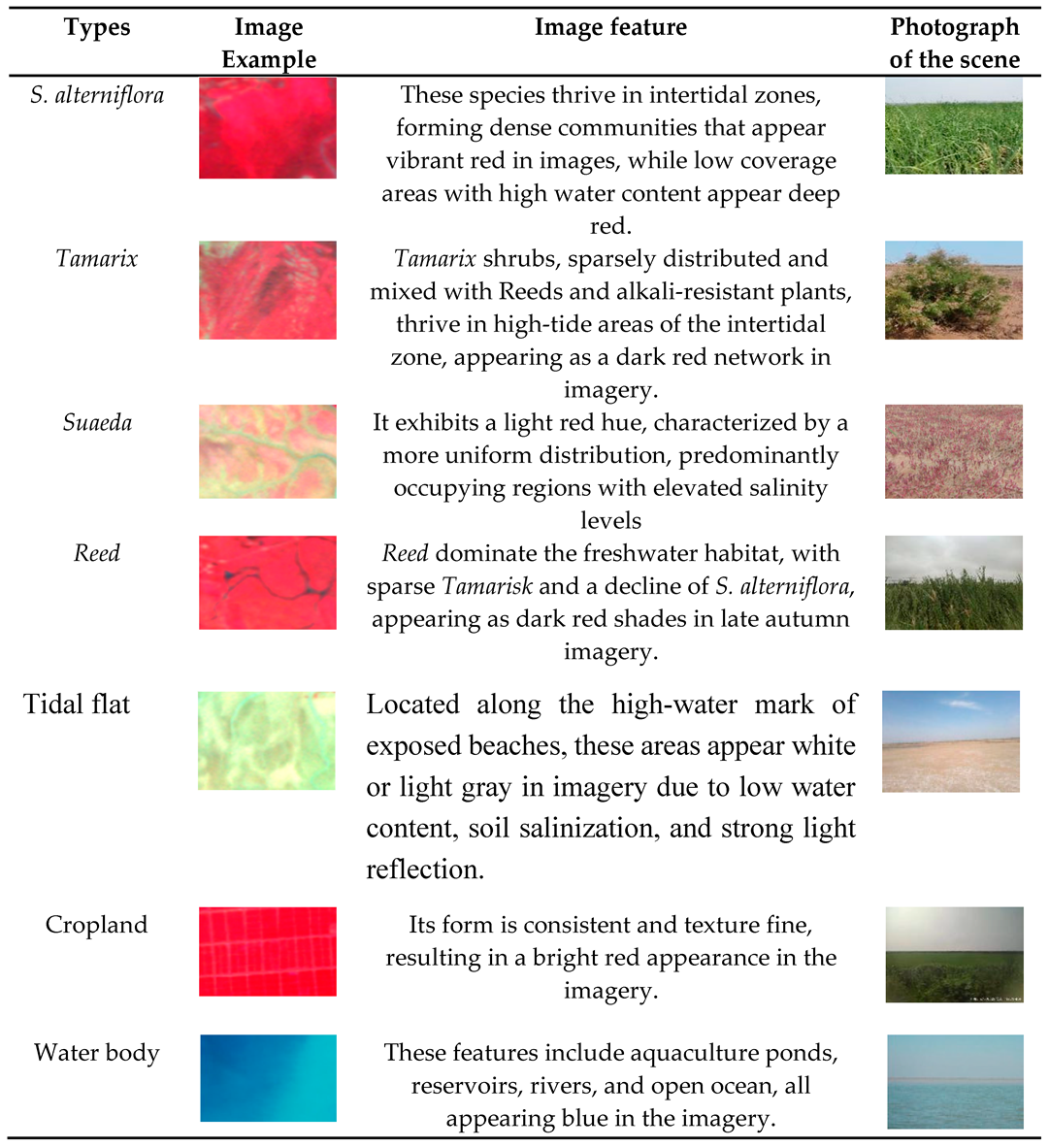

2.3.1. Feature Analysis

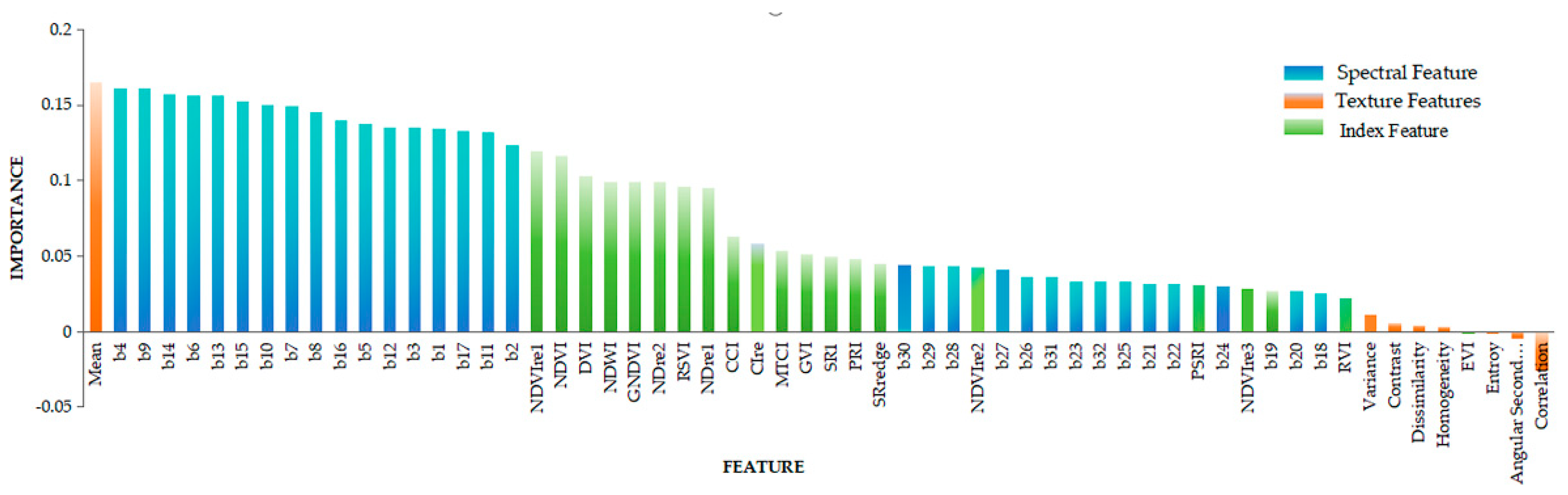

2.3.2. Feature Selection

2.3.3. Generate the Training Data

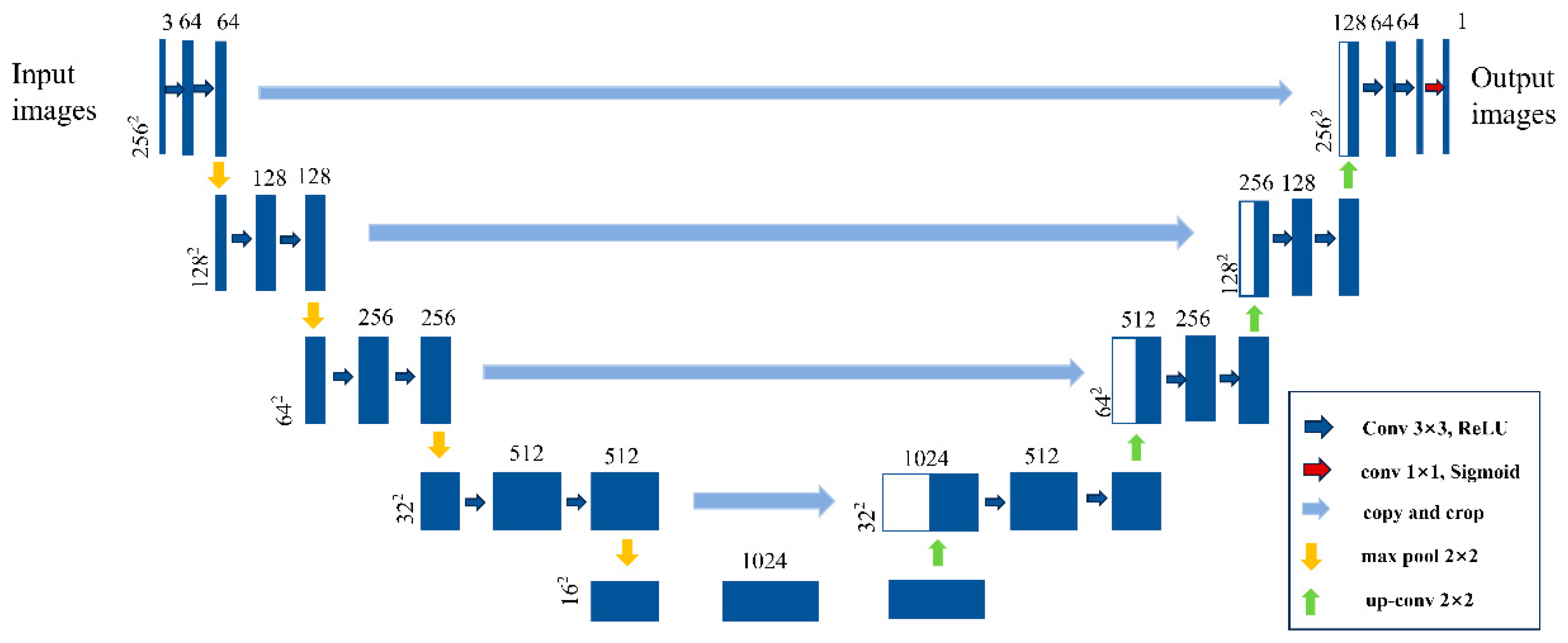

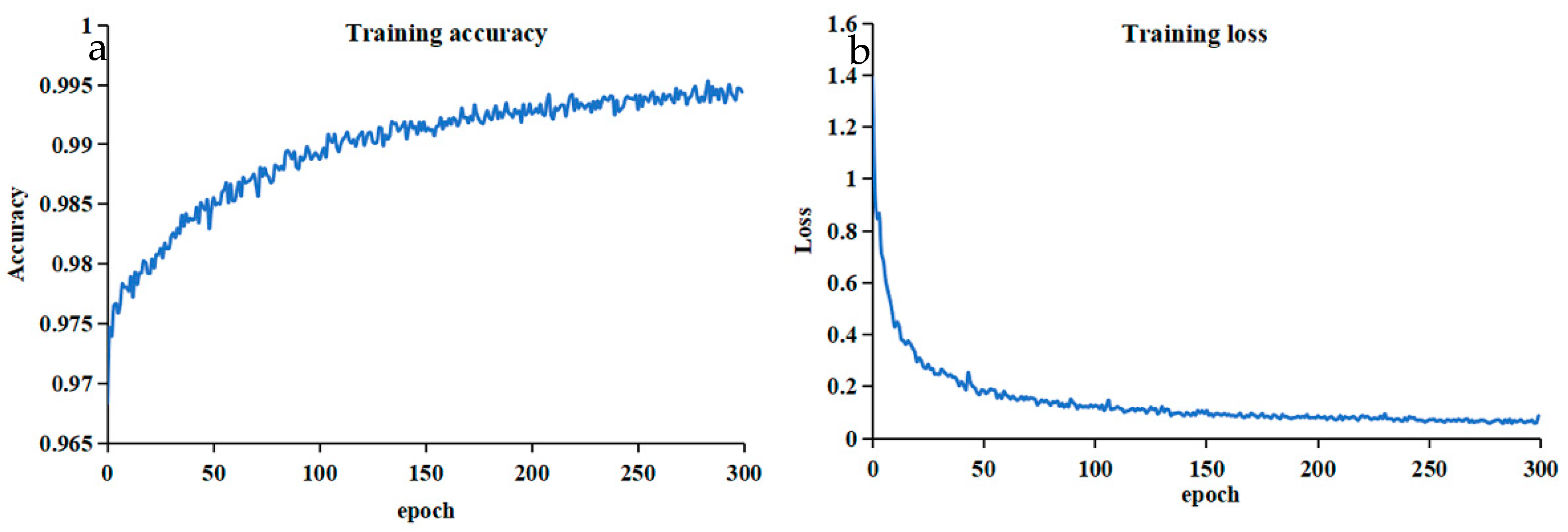

2.3.4. U-Net Training and Prediction

2.3.5 Accuracy Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Feature Selection and Accuracy Assessment

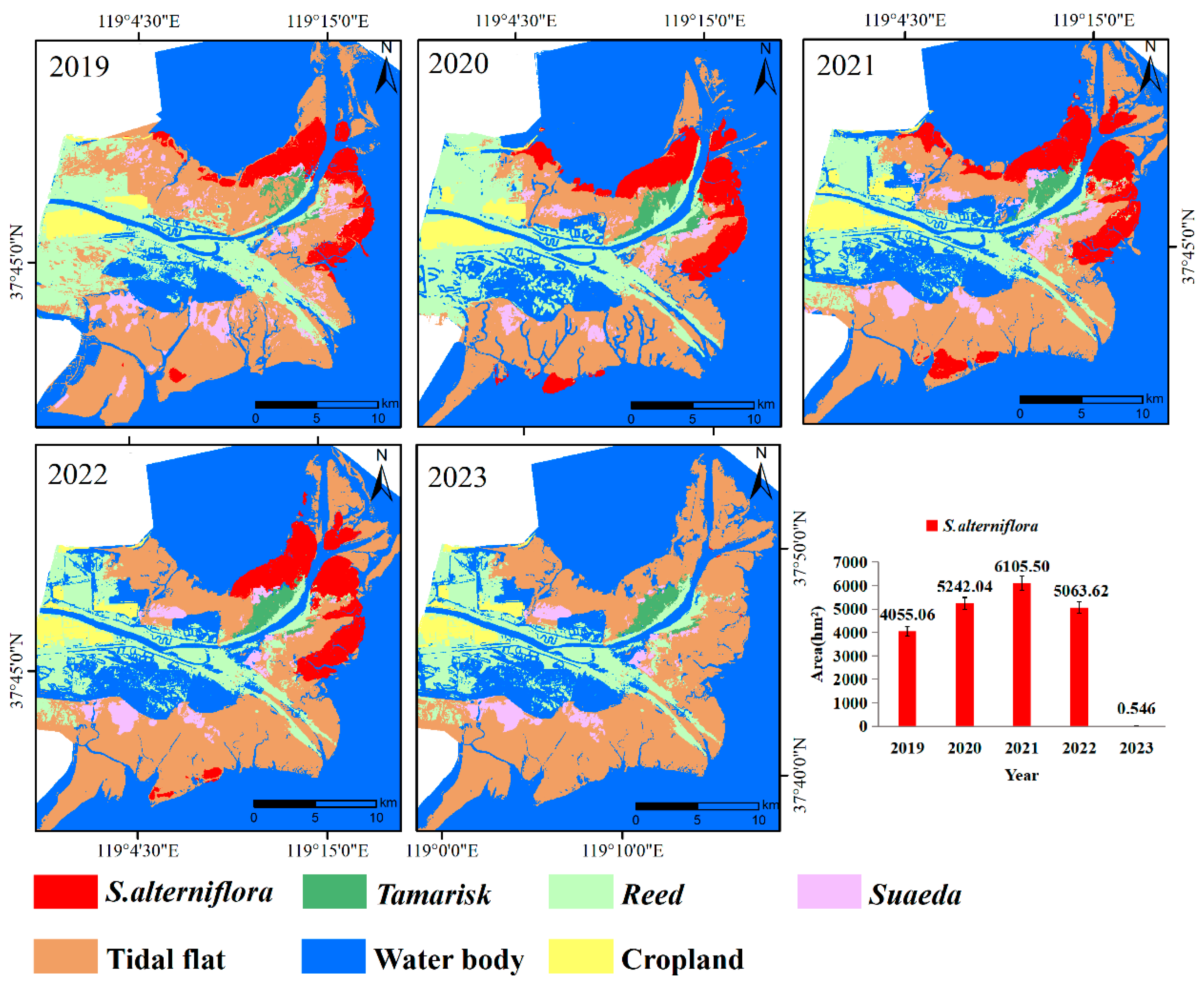

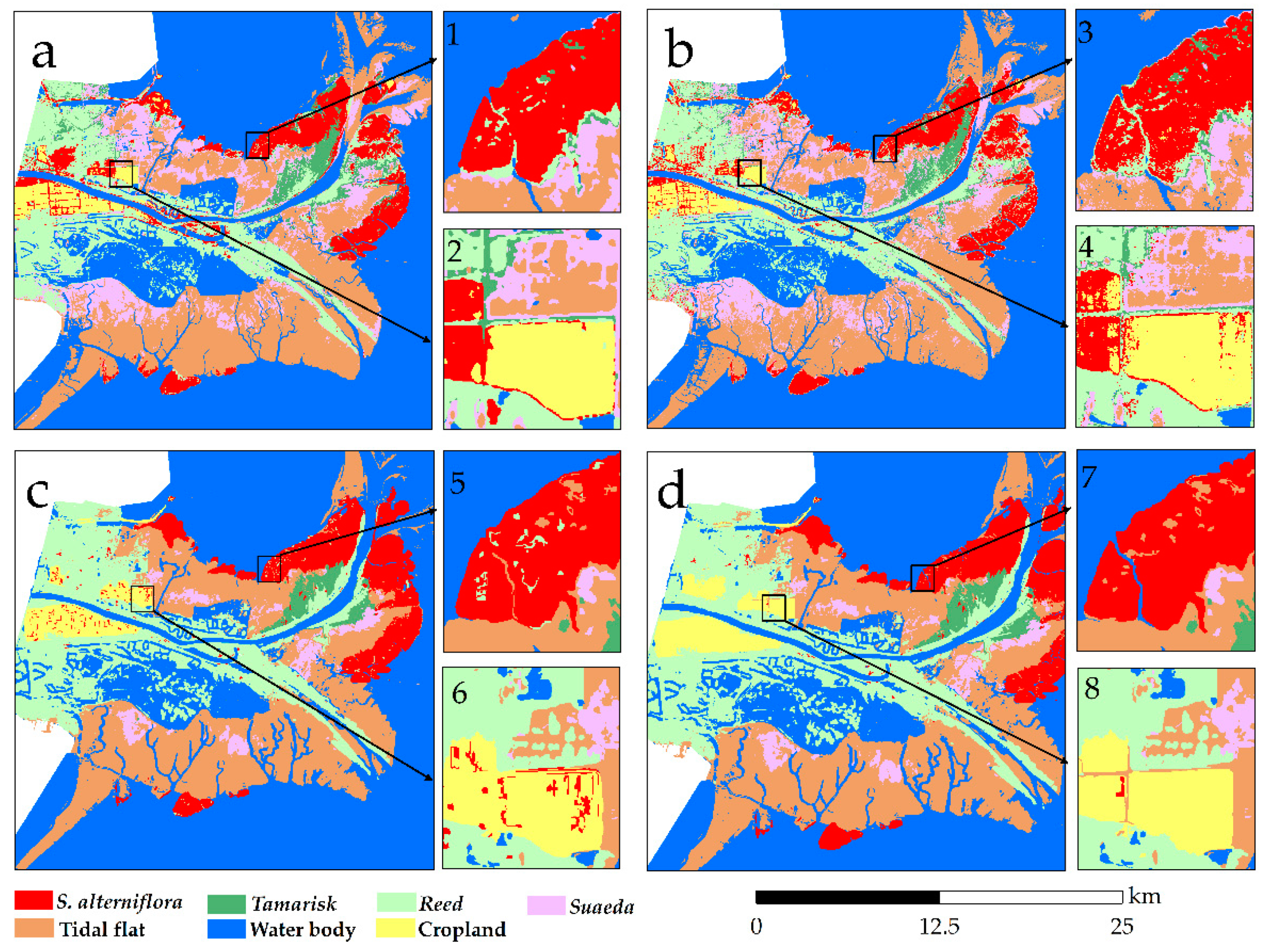

3.2. Temporal and Spatial Changes of S. alterniflora in YRD

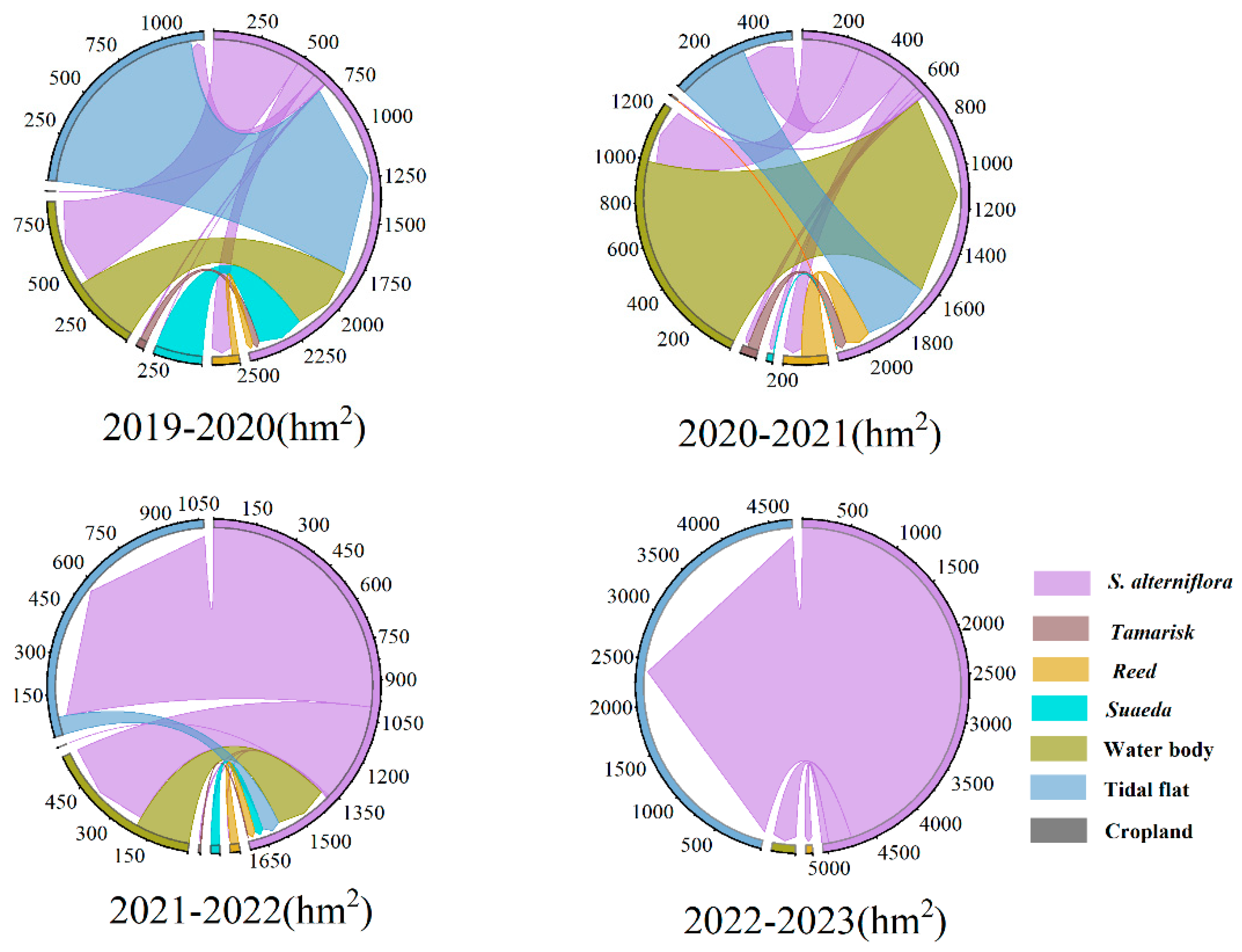

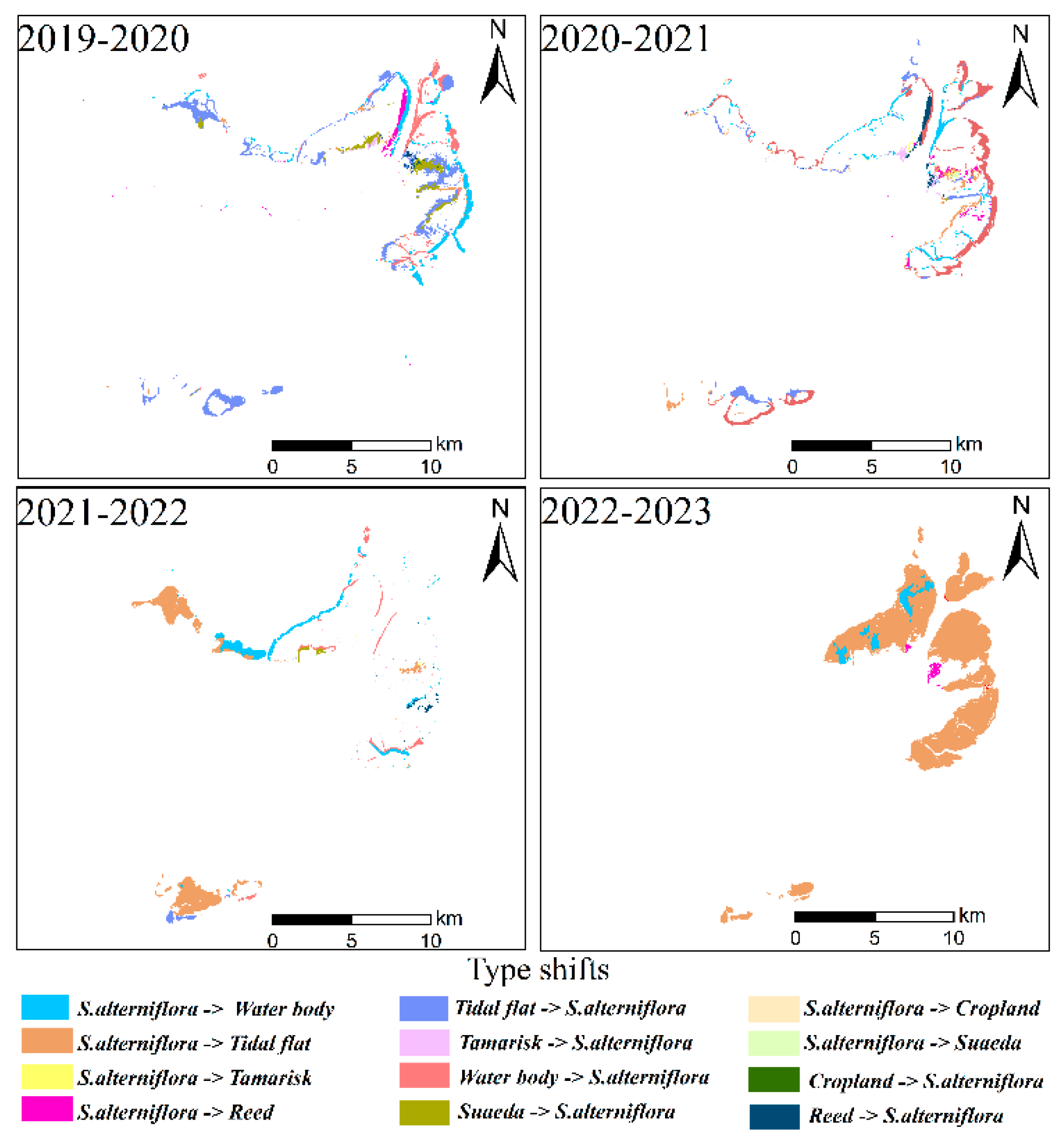

3.3. Conversions Between S. alterniflora and Other Land Cover Types

4. Discussion

4.1. Uncertainties

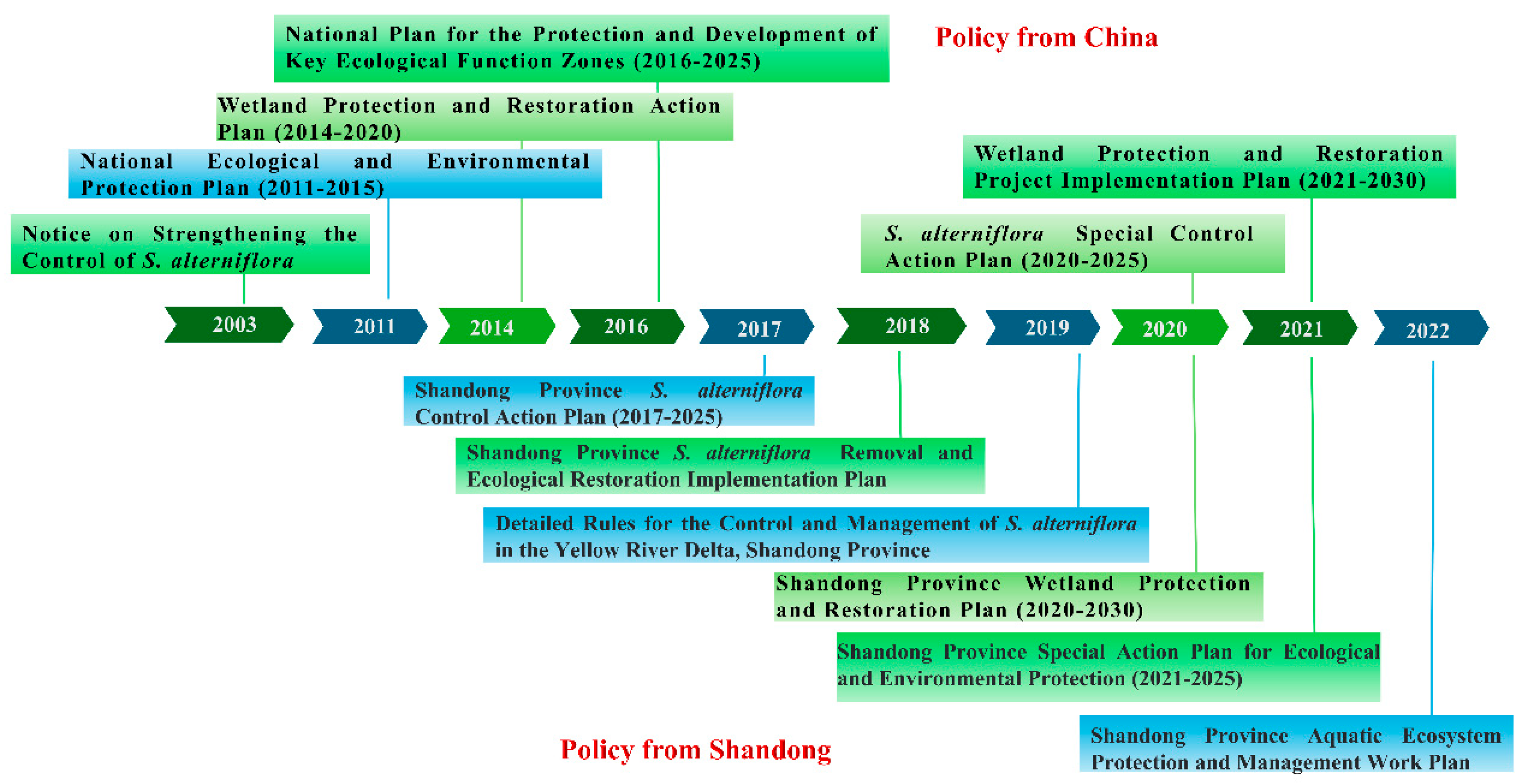

4.2. Policies and Measures to Control S. alterniflora Invasion in YRD

4.3. Future Managements of S. alterniflora

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MEa, M.E.A. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: wetlands and water synthesis. 2005.

- Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Madden, M.; Mao, D. China’s wetlands: conservation plans and policy impacts. Ambio 2012, 41, 782-786.

- Yan, D.; Li, J.; Yao, X.; Luan, Z. Quantifying the long-term expansion and dieback of Spartina alterniflora using google earth engine and object-based hierarchical random forest classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 9781-9793.

- Hou, X.; Wu, T.; Hou, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L. Characteristics of coastline changes in mainland China since the early 1940s. Science China Earth Sciences 2016, 59, 1791-1802.

- Civille, J.C.; Sayce, K.; Smith, S.D.; Strong, D.R. Reconstructing a century of Spartina alterniflora invasion with historical records and contemporary remote sensing. Ecoscience 2005, 12, 330-338.

- Zhu, W.; Ren, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, N. Monitoring the Invasive Plant Spartina alterniflora in Jiangsu Coastal Wetland Using MRCNN and Long-Time Series Landsat Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Li, J.; Xie, S.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Luan, Z. Examining the expansion of Spartina alterniflora in coastal wetlands using an MCE-CA-Markov model. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.-B.; Wang, J.-J.; Wang, A.-D.; Wang, J.-B.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Wu, P.-Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J. Monitoring the invasion of smooth cordgrass Spartina alterniflora within the modern Yellow River Delta using remote sensing. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 90, 135-145.

- Zhou, H.-X.; Liu, J.-e.; Qin, P. Impacts of an alien species (Spartina alterniflora) on the macrobenthos community of Jiangsu coastal inter-tidal ecosystem. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 521-528.

- Müllerová, J.; Pergl, J.; Pyšek, P. Remote sensing as a tool for monitoring plant invasions: Testing the effects of data resolution and image classification approach on the detection of a model plant species Heracleum mantegazzianum (giant hogweed). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2013, 25, 55-65.

- Lü, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z. Wetland landscape pattern change and its driving forces in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in recent 30 years. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2018, 38, 4492-4503.

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Gong, H.; Lin, Z.; Lv, S. Appling the one-class classification method of maxent to detect an invasive plant Spartina alterniflora with time-series analysis. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1120.

- Gong, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Bai, J.; Zhou, D. Assessing spatiotemporal characteristics of native and invasive species with multi-temporal remote sensing images in the Yellow River Delta, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 1338-1352.

- Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Yin, D.; Li, X.; Diao, C.; Gong, H.; Shi, C.; Menenti, M.; Ge, Y.; Nie, S. Development of spectral-phenological features for deep learning to understand Spartina alterniflora invasion. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 242, 111745.

- Xie, T.; Li, S.; Cui, B.; Bai, J.; Wang, Q.; Shi, W. Rainfall variation shifts habitat suitability for seedling establishment associated with tidal inundation in salt marshes. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 694-703.

- Xie, T.; Cui, B.; Li, S.; Zhang, S. Management of soil thresholds for seedling emergence to re-establish plant species on bare flats in coastal salt marshes. Hydrobiologia 2019, 827, 51-63.

- Ozesmi, S.L.; Bauer, M.E. Satellite remote sensing of wetlands. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 10, 381-402.

- Qiu, Z.; Mao, D.; Feng, K.; Wang, M.; Xiang, H.; Wang, Z. High-resolution mapping changes in the invasion of Spartina Alterniflora in the Yellow River Delta. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 6445-6455.

- Chen, M.; Ke, Y.; Bai, J.; Li, P.; Lyu, M.; Gong, Z.; Zhou, D. Monitoring early stage invasion of exotic Spartina alterniflora using deep-learning super-resolution techniques based on multisource high-resolution satellite imagery: A case study in the Yellow River Delta, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 92, 102180. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, P.; Zhao, S.; Liu, C.a.; Wang, C.; Liang, Y. Distribution of Spartina spp. along China’s coast. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 40, 160-166.

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, B. Rapid and large changes in coastal wetland structure in China’s four major river deltas. Global Change Biology 2023, 29, 2286-2300.

- Liu, M.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Man, W.; Jia, M.; Wang, Z.; Lu, C. Monitoring the invasion of Spartina alterniflora using multi-source high-resolution imagery in the Zhangjiang Estuary, China. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 539.

- Kuenzer, C.; Bluemel, A.; Gebhardt, S.; Quoc, T.V.; Dech, S. Remote Sensing of Mangrove Ecosystems: A Review. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 878-928. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, A.; Madden, M.; Welch, R.J.W. Hyperspectral image data for mapping wetland vegetation. 2003, 23, 436-448.

- Yan, D.; Li, J.; Yao, X.; Luan, Z.J.S.o.T.T.E. Integrating UAV data for assessing the ecological response of Spartina alterniflora towards inundation and salinity gradients in coastal wetland. 2022, 814, 152631.

- Stuart, M.B.; McGonigle, A.J.; Willmott, J.R. Hyperspectral imaging in environmental monitoring: A review of recent developments and technological advances in compact field deployable systems. Sensors 2019, 19, 3071.

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Tian, J.; Shi, C. Object-based spectral-phenological features for mapping invasive Spartina alterniflora. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 101, 102349.

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Datta, P.; Frey, J.; Koch, B. Mapping an invasive plant Spartina alterniflora by combining an ensemble one-class classification algorithm with a phenological NDVI time-series analysis approach in middle coast of Jiangsu, China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4010.

- Li, H.; Mao, D.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, L.; Jia, M. Invasion of Spartina alterniflora in the coastal zone of mainland China: Control achievements from 2015 to 2020 towards the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116242. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jia, M.; Wang, Z.; Mao, D.; Du, B.; Wang, C. Monitoring invasion process of Spartina alterniflora by seasonal Sentinel-2 imagery and an object-based random forest classification. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1383.

- Van Beijma, S.; Comber, A.; Lamb, A. Random forest classification of salt marsh vegetation habitats using quad-polarimetric airborne SAR, elevation and optical RS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 149, 118-129.

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.-W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 1527-1554.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xue, X.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, Q. Deep learning for remote sensing image classification: A survey. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2018, 8, e1264.

- Kaili, C.; Xiaoli, Z. An improved res-unet model for tree species classification using airborne high-resolution images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1128.

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015; pp. 3431-3440.

- Maggiori, E.; Tarabalka, Y.; Charpiat, G.; Alliez, P. Convolutional neural networks for large-scale remote-sensing image classification. IEEE Transactions on geoscience and remote sensing 2016, 55, 645-657.

- Sharma, A.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Shi, D. A patch-based convolutional neural network for remote sensing image classification. Neural Netw. 2017, 95, 19-28.

- Stoian, A.; Poulain, V.; Inglada, J.; Poughon, V.; Derksen, D. Land cover maps production with high resolution satellite image time series and convolutional neural networks: Adaptations and limits for operational systems. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1986.

- Li, H.; Wang, C.; Cui, Y.; Hodgson, M. Mapping salt marsh along coastal South Carolina using U-Net. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 179, 121-132. [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Cai, Y.; Wang, X. Small Waterbody Extraction With Improved U-Net Using Zhuhai-1 Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, C. Identification of Spartina alterniflora habitat expansion in a Suaeda salsa dominated coastal wetlands. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145. [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Tian, J.; Chen, Y.J.J.o.B.U. Biological and ecological characteristics of an invasive alien species Spartina in Yellow River Delta. 2009, 25, 27-32.

- Zhang, C.; Gong, Z.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, D. Mapping typical salt-marsh species in the Yellow River Delta wetland supported by temporal-spatial-spectral multidimensional features. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 147061. [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Xie, T.; Ning, Z.; Cui, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, F.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Y. Invasion patterns of Spartina alterniflora: Response of clones and seedlings to flooding and salinity—A case study in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162803.

- Ren, J.S.; Wang, R.X.; Liu, G.; Feng, R.Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Wu, W. Partitioned Relief-F Method for Dimensionality Reduction of Hyperspectral Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.-T.; Gao, Y.; Xie, X.; Guo, H.-Q.; Zhang, T.-T.; Zhao, B. Spectral discrimination of the invasive plant Spartina alterniflora at multiple phenological stages in a saltmarsh wetland. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67315.

- Su, Z.; Li, W.; Ma, Z.; Gao, R. An improved U-Net method for the semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. Applied Intelligence 2022, 52, 3276-3288.

- Maebara, Y.; Tamaoki, M.; Iguchi, Y.; Nakahama, N.; Hanai, T.; Nishino, A.; Hayasaka, D. Genetic diversity of invasive Spartina alterniflora Loisel.(Poaceae) introduced unintentionally into Japan and its invasion pathway. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 556039.

- Roberts, A.; Pullin, A.S. The effectiveness of management interventions for the control of Spartina species: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2008, 18, 592-618.

- Nehring, S.; Hesse, K.-J. Invasive alien plants in marine protected areas: the Spartina anglica affair in the European Wadden Sea. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 937-950. [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; van Wyk, E.; Riddin, T. First record of Spartina alterniflora in southern Africa indicates adaptive potential of this saline grass. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 2153-2158. [CrossRef]

- An, S.Q.; Gu, B.H.; Zhou, C.F.; Wang, Z.S.; Deng, Z.F.; Zhi, Y.B.; Li, H.L.; Chen, L.; Yu, D.H.; Liu, Y.H. Spartina invasion in China: implications for invasive species management and future research. Weed Research 2007, 47, 183-191. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Maung-Douglass, K.; Strong, D.R.; Pennings, S.C.; Zhang, Y. Geographical variation in vegetative growth and sexual reproduction of the invasive Spartina alterniflora in China. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 173-181. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L. An experimental study on physical controls of an exotic plant Spartina alterniflora in Shanghai, China. Ecol. Eng. 2008, 32, 11-21. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, M. Monitoring of the invasion of Spartina alterniflora from 1985 to 2015 in Zhejiang Province, China. BMC Ecol. 2020, 20, 7. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P. Study on Mechanical and Chemical Control of Invasive Plant Spartina alterniflora in Yellow River Delta. Hohhot: Inner Mongolia University, 2019 2019.

- Xie, B.; Han, G.; Qiao, P.; Mei, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, A.; Song, W.; Guan, B. Effects of mechanical and chemical control on invasive Spartina alterniflora in the Yellow River Delta, China. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7655. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-y.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.-j.; Zhang, L.-q. Emergency control of Spartina alterniflora re-invasion with a chemical method in Chongming Dongtan, China. Water Science and Engineering 2020, 13, 24-33. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Yan, Z.; Li, X. Influence of the herbicide haloxyfop-R-methyl on bacterial diversity in rhizosphere soil of Spartina alterniflora. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 194, 110366. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Hacker, S.; Ayres, D.; Strong, D.R. Potential of Prokelisia spp. as Biological Control Agents of English Cordgrass, Spartina anglica. Biol. Control 1999, 16, 267-273. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.J.; DiTomaso, J.M.; Gordon, T.R. Intraspecific groups of Claviceps purpurea associated with grass species in Willapa Bay, Washington, and the prospects for biological control of invasive Spartina alterniflora. Biol. Control 2005, 34, 170-179. [CrossRef]

- Silliman, B.R.; Zieman, J.C. Top-down control of Spartina alterniflora production by periwinkle grazing in a Virginia salt marsh. ECOLOGY 2001, 82, 2830-2845. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Martin, P.A.; Hao, Y.; Sutherland, W.J.; Shackelford, G.E.; Wu, J.H.; Ju, R.T.; Zhou, W.N.; Li, B. A global synthesis of the effectiveness and ecological impacts of management interventions for Spartina species. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

| Group | Number of Features | Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 0.877 |

| 2 | 20 | 0.891 |

| 3 | 30 | 0.905 |

| 4 | 40 | 0.930 |

| 5 | 50 | 0.905 |

| 6 | 60 | 0.898 |

| SVM | RF | U-Net | U-Net + Relief-F | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | UA | PA | UA | PA | UA | PA | UA | |

| Water body | 0.860 | 0.895 | 0.870 | 0.936 | 0.903 | 0.880 | 0.931 | 0.984 |

| S. alterniflora | 0.904 | 0.876 | 0.909 | 0.923 | 0.910 | 0.852 | 0.921 | 0.957 |

| Tidal flat | 0.734 | 0.772 | 0.801 | 0.799 | 0.832 | 0.821 | 0.886 | 0.839 |

| Reed | 0.836 | 0.868 | 0.874 | 0.870 | 0.883 | 0.842 | 0.896 | 0.960 |

| Cropland | 0.946 | 0.835 | 0.946 | 0.815 | 0.940 | 0.930 | 0.934 | 0.919 |

| Suaeda | 0.959 | 0.859 | 0.961 | 0.874 | 0.930 | 0.879 | 0.935 | 0.891 |

| Tamarisk | 0.492 | 0.944 | 0.492 | 0.896 | 0.789 | 0.732 | 0.917 | 0.925 |

| OA | 0.859 | 0.878 | 0.913 | 0.930 | ||||

| Kappa | 0.863 | 0.849 | 0.902 | 0.912 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).