Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

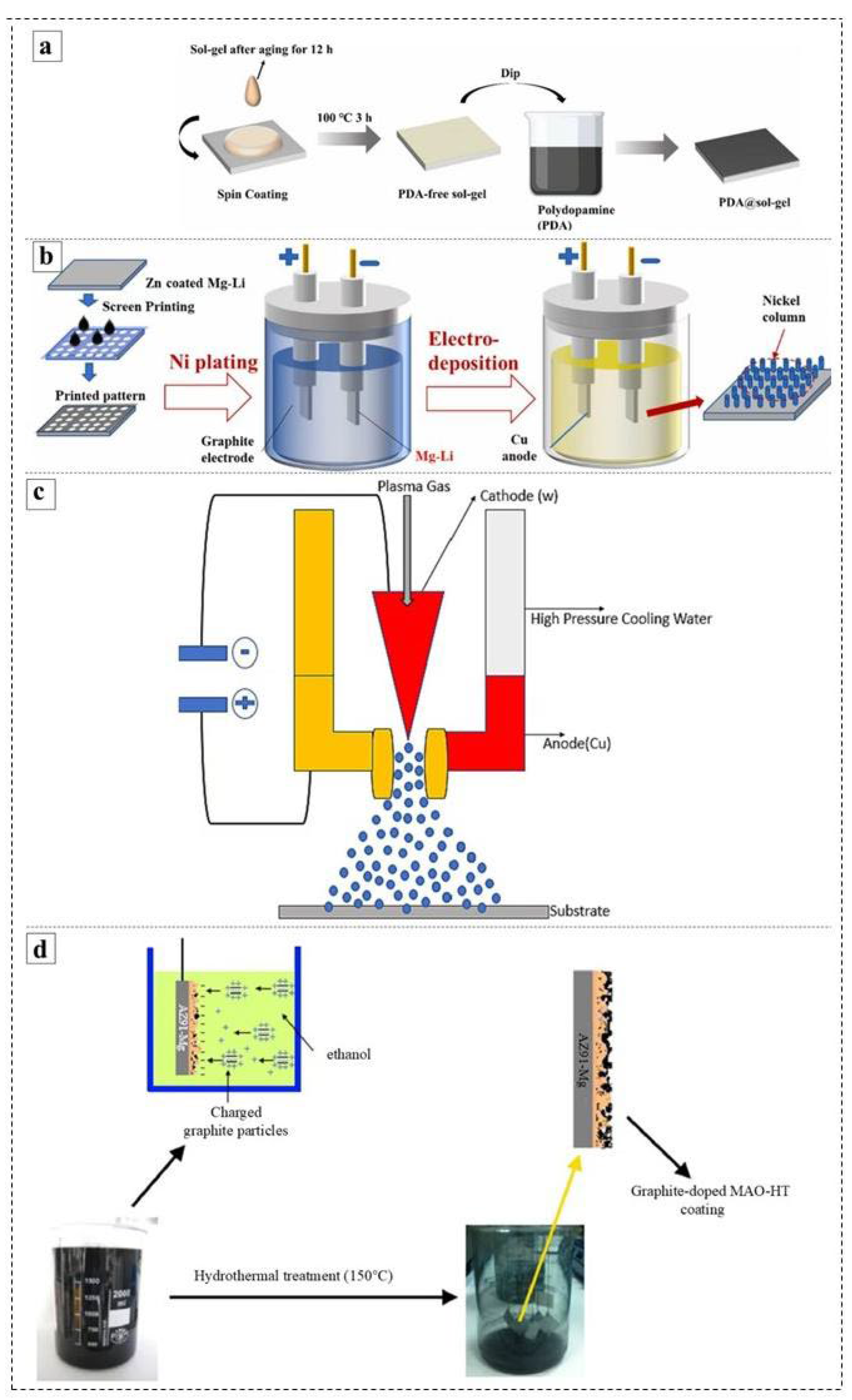

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

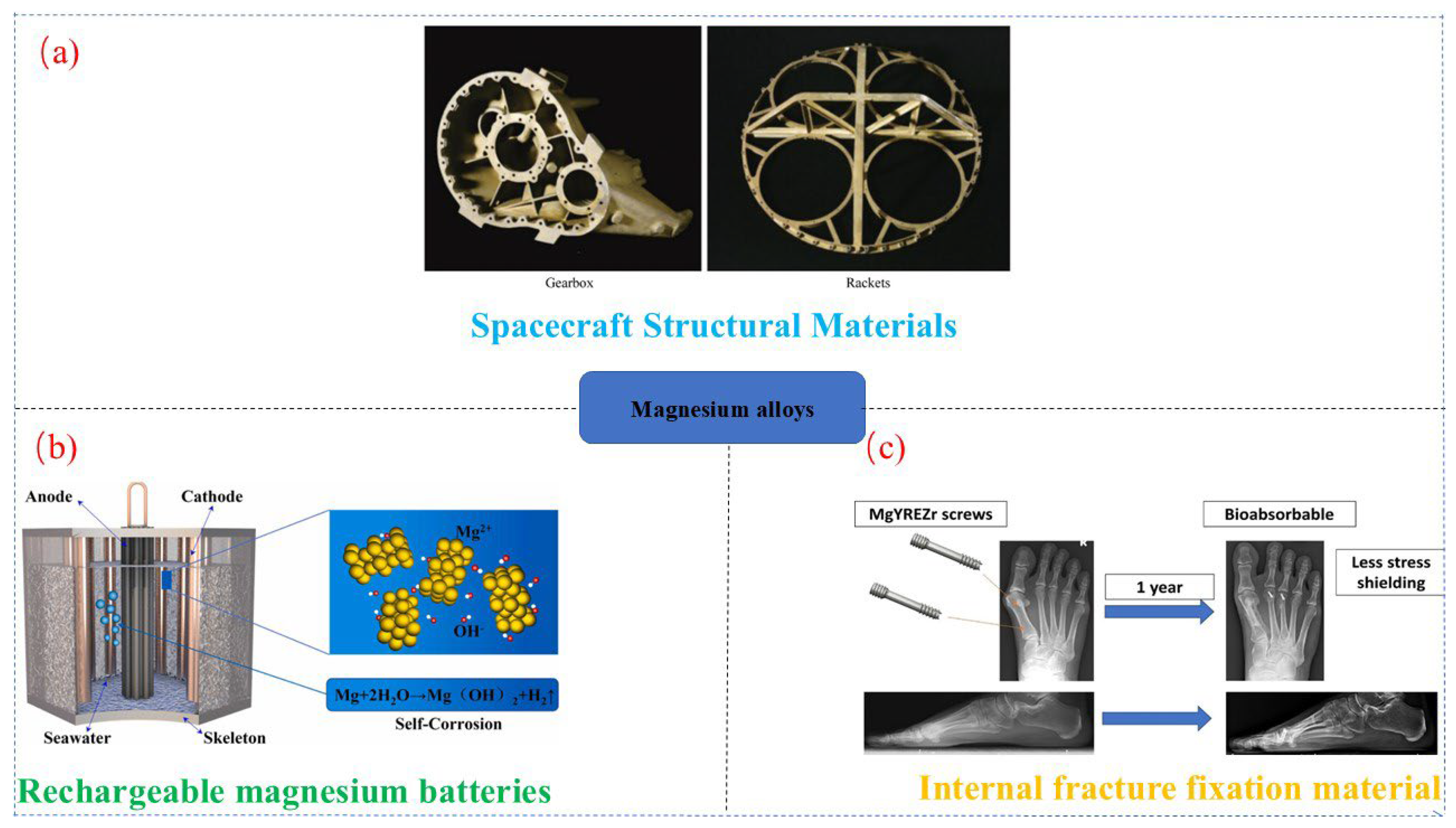

1. Introduction

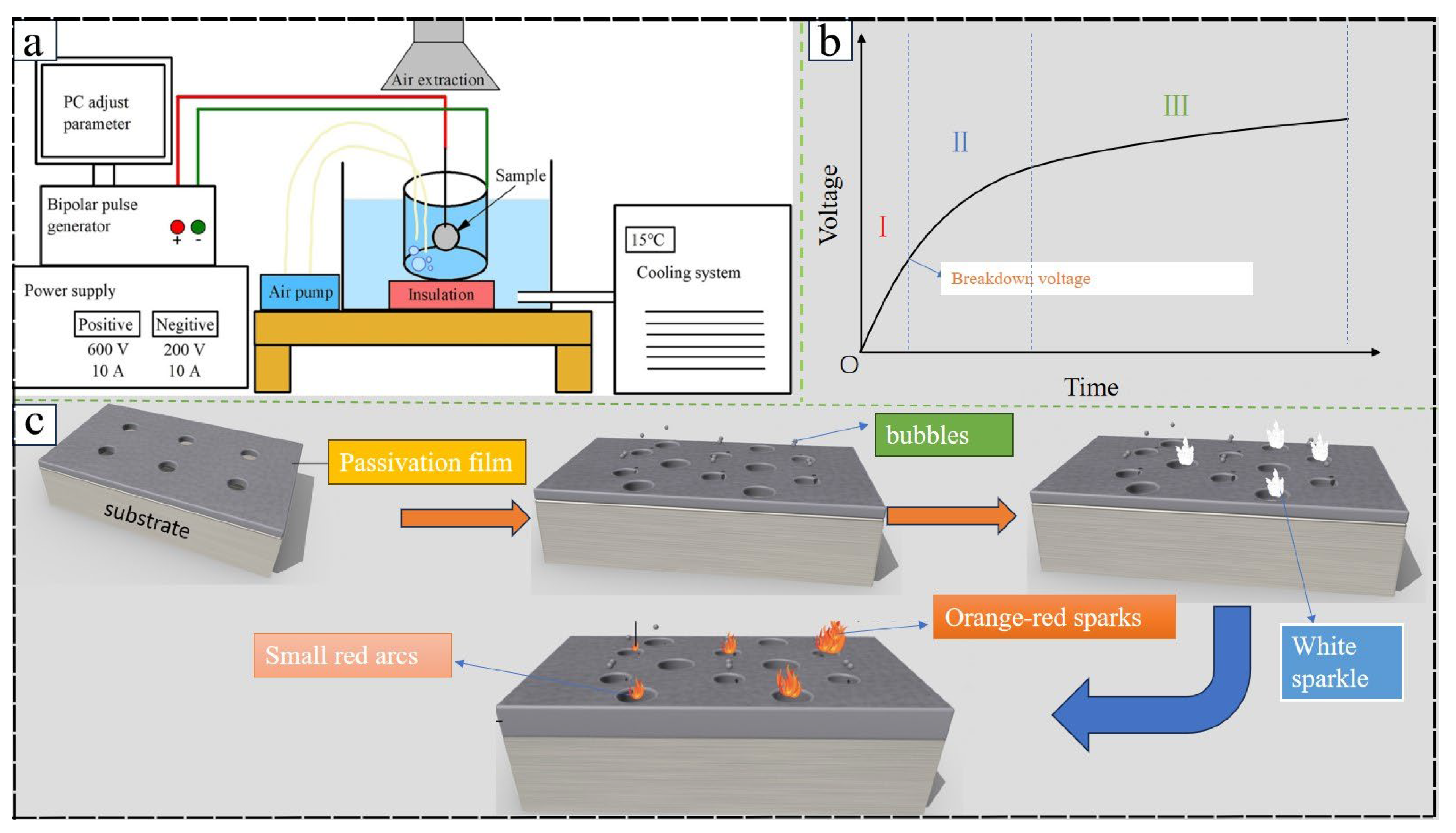

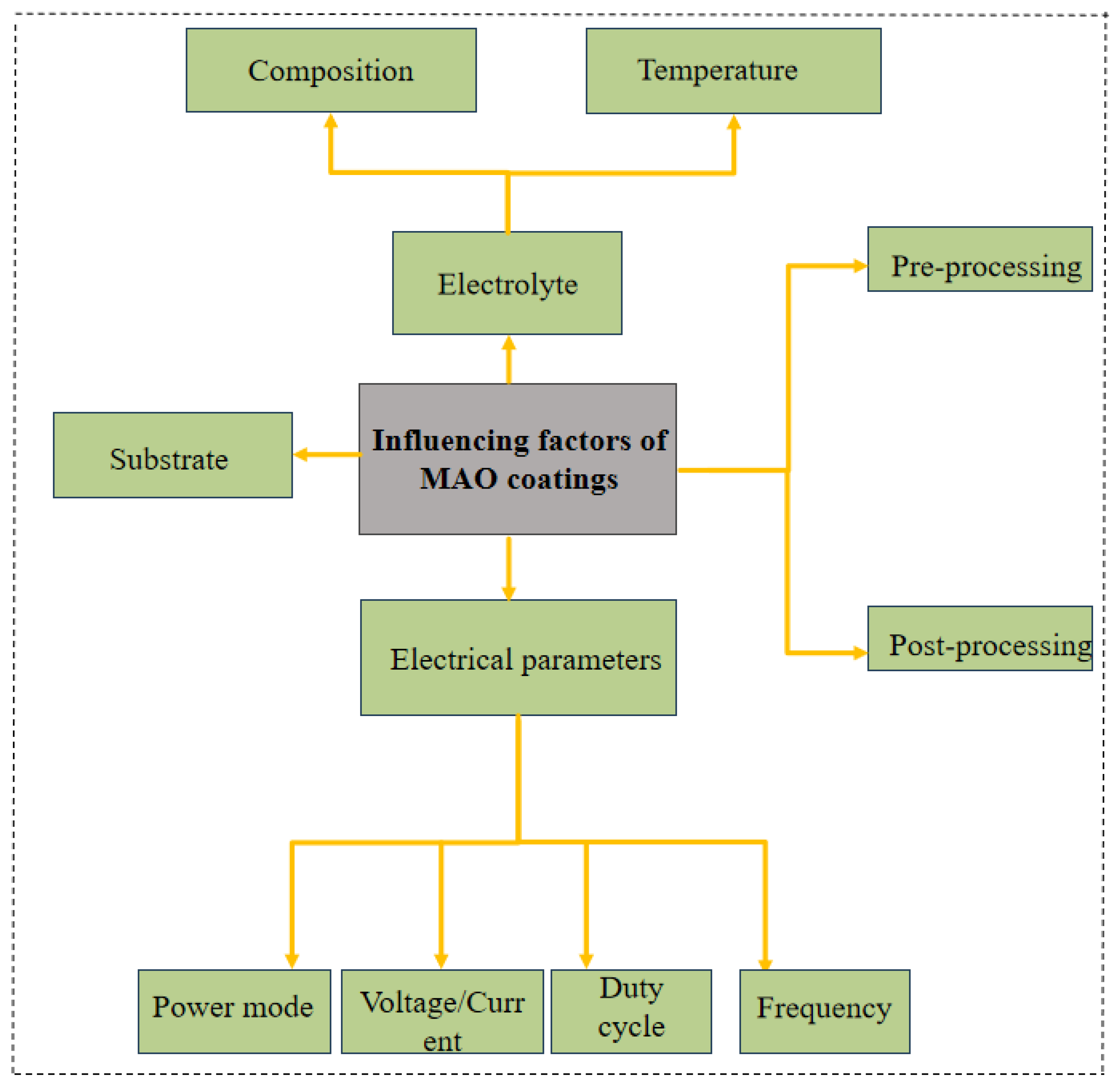

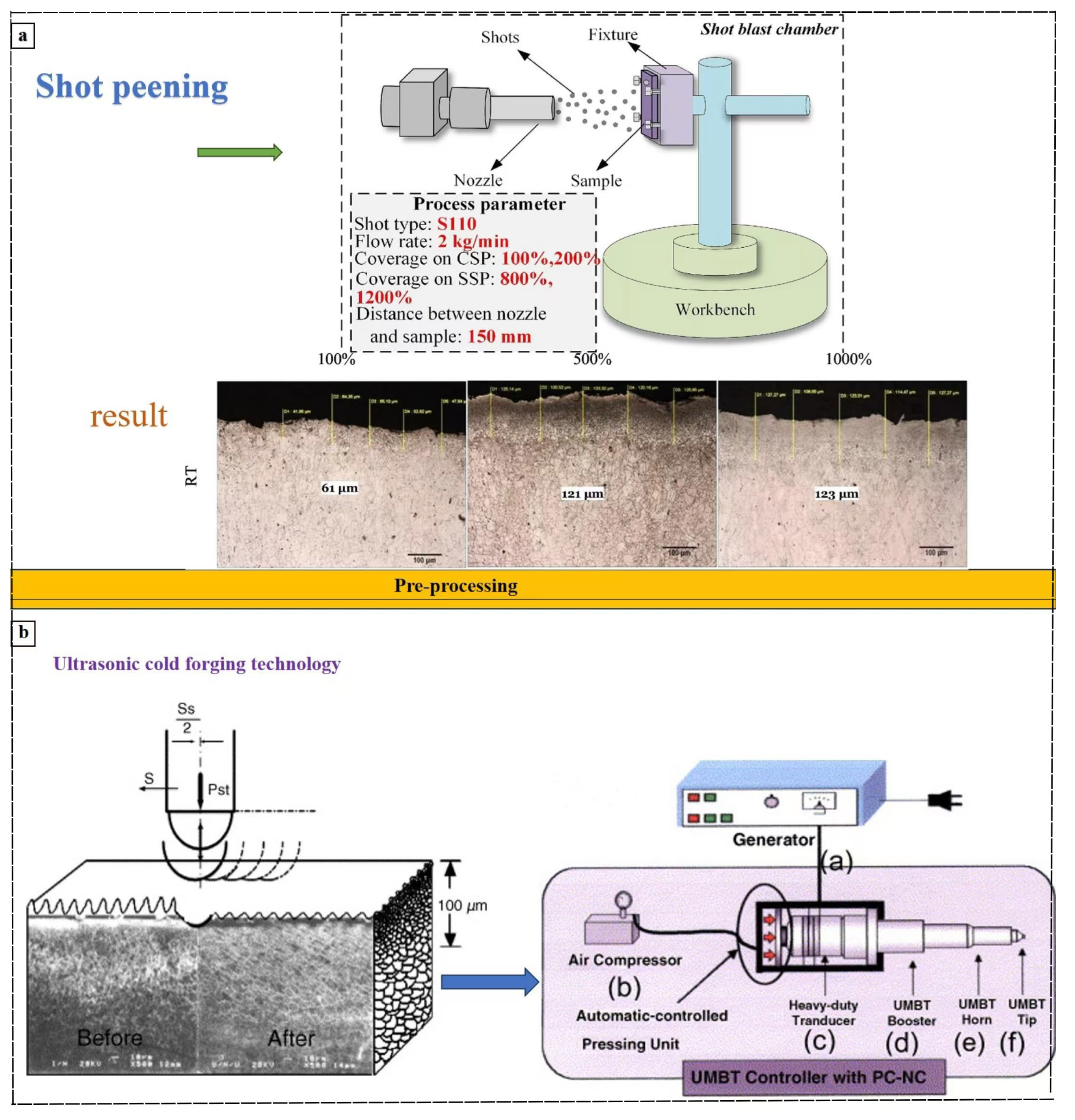

2. Effect of Pre-Processing on the Corrosion Resistance of MAO Coatings on Mg Alloys

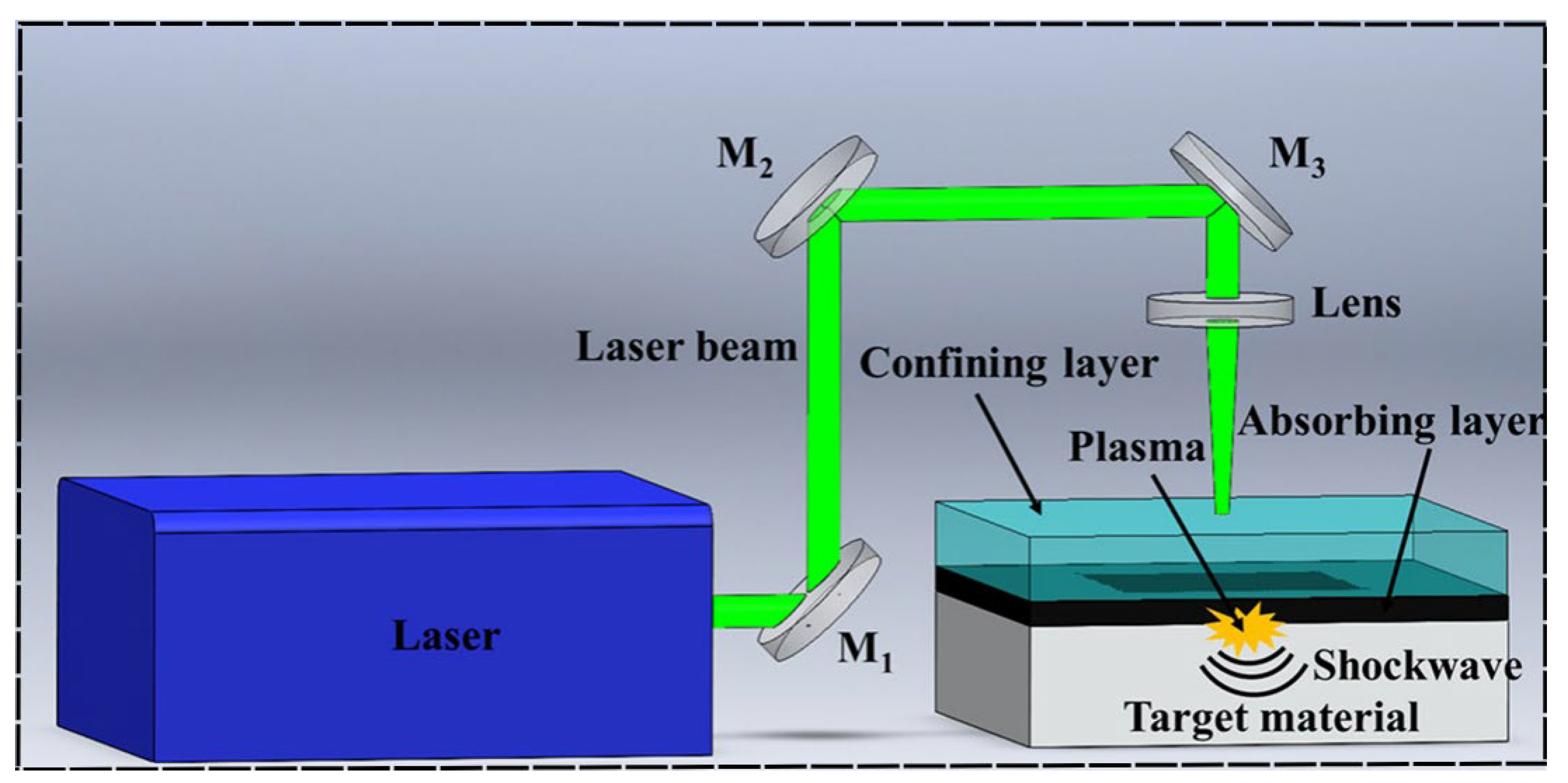

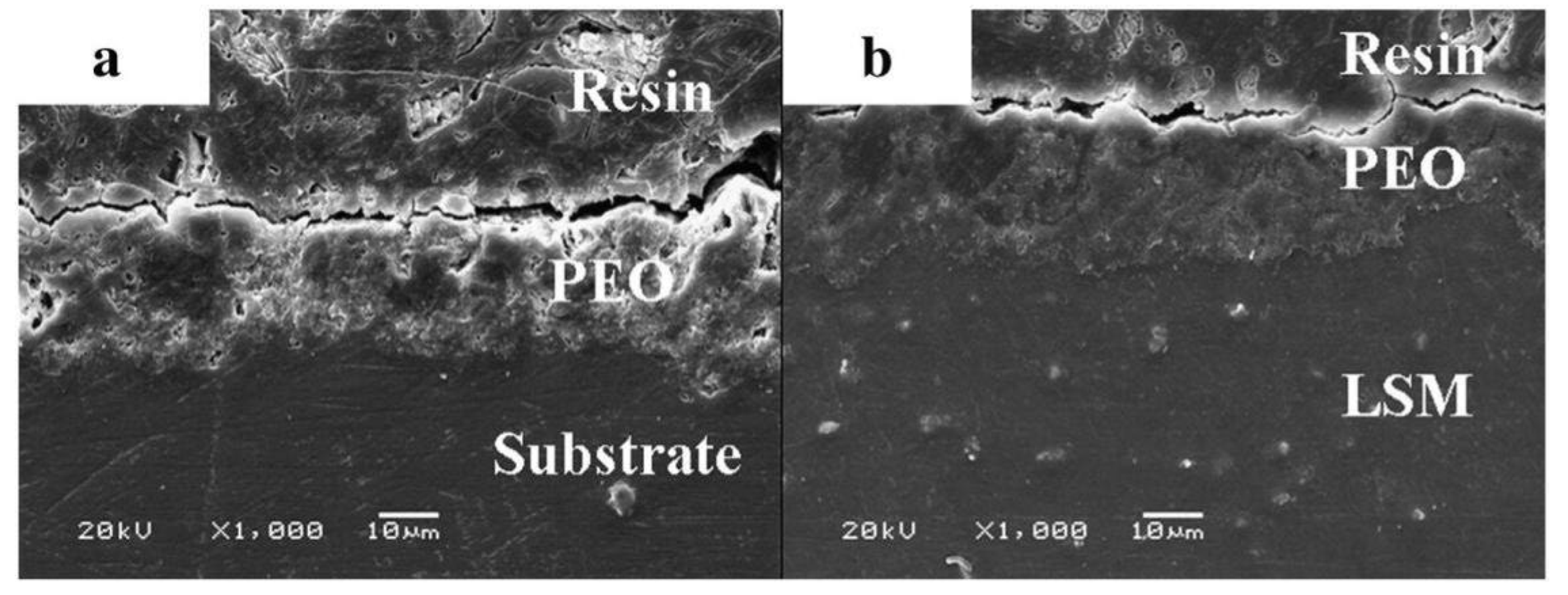

2.1. Surface Laser Process

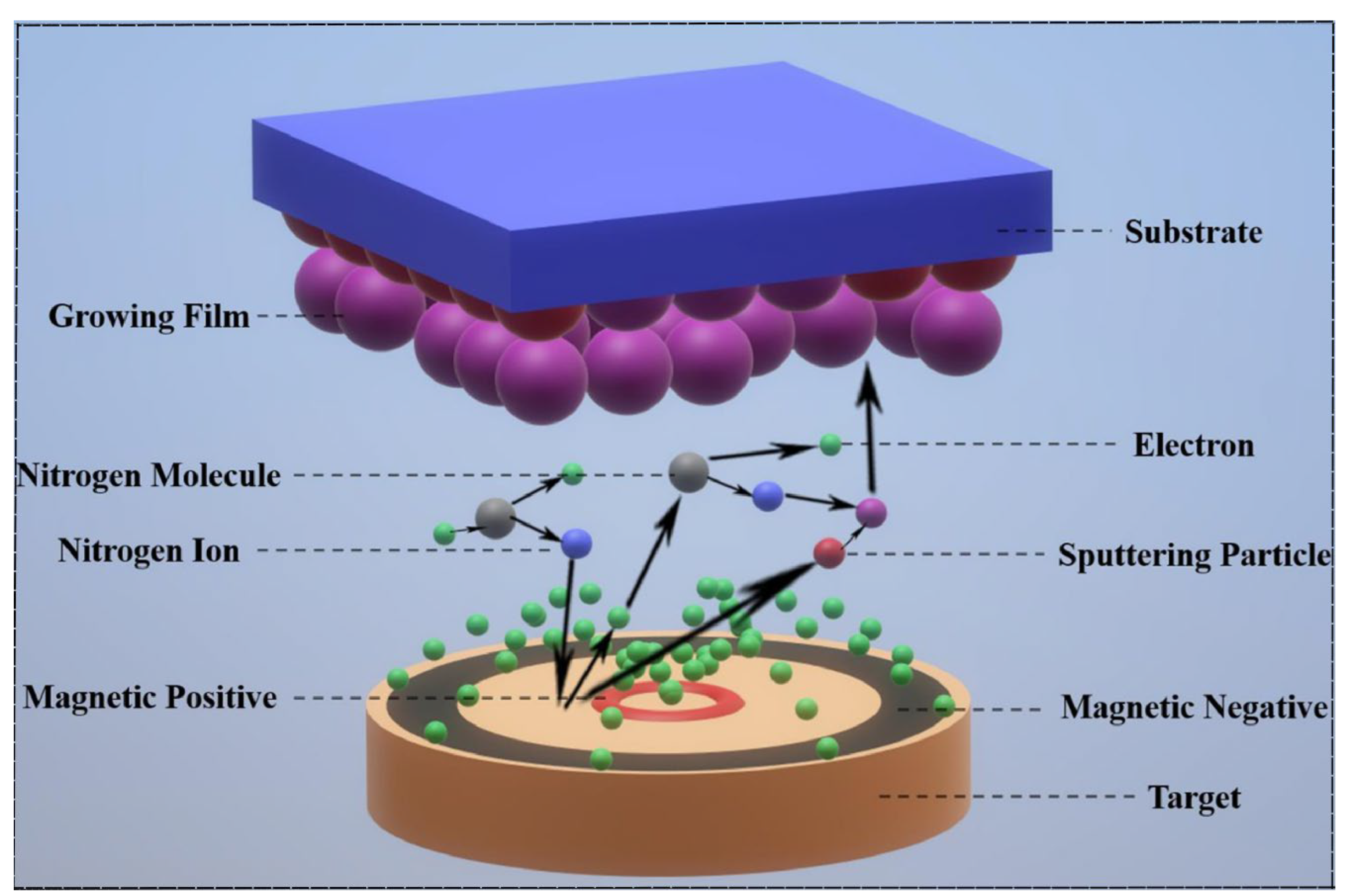

2.2. Magnetron Sputtering

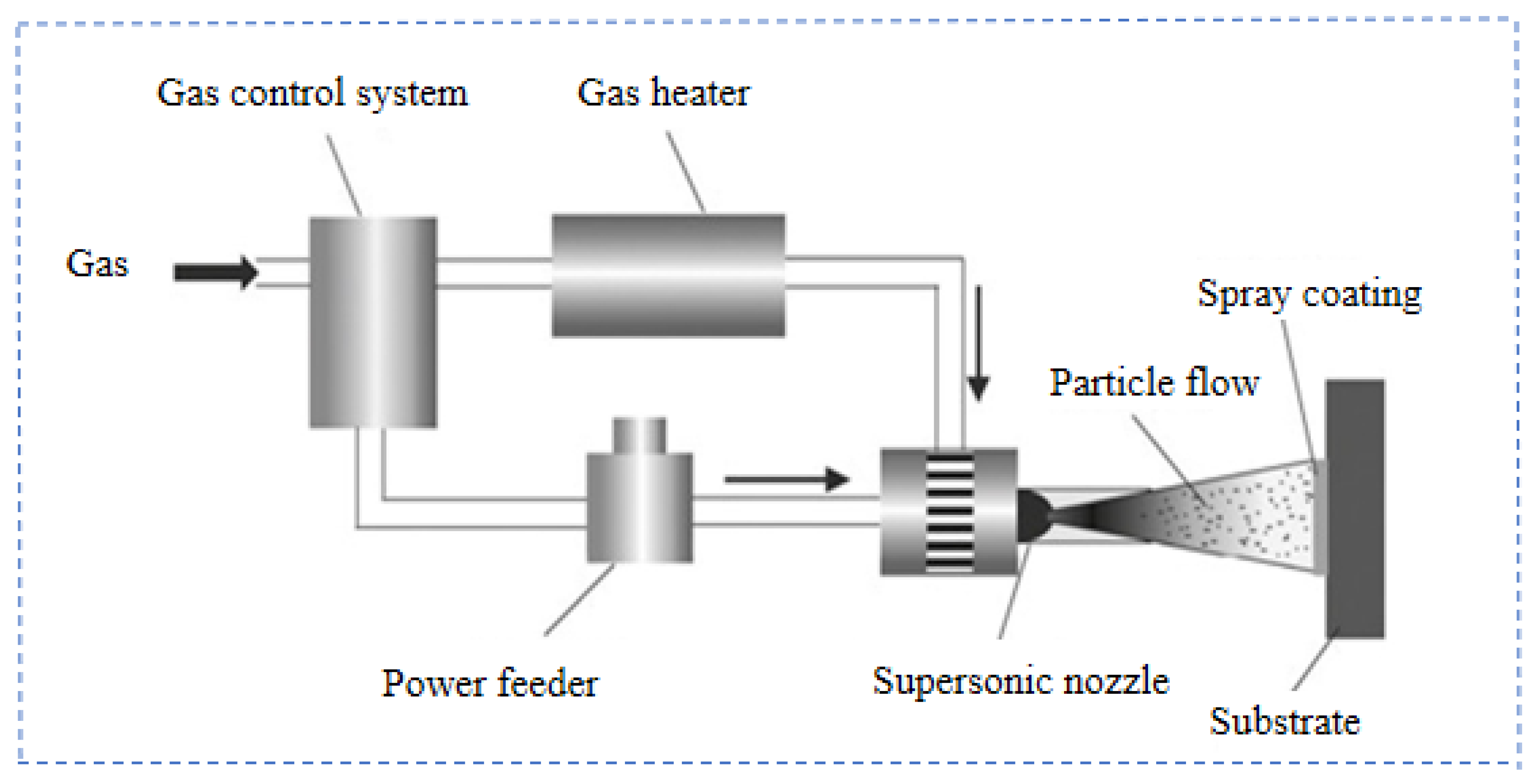

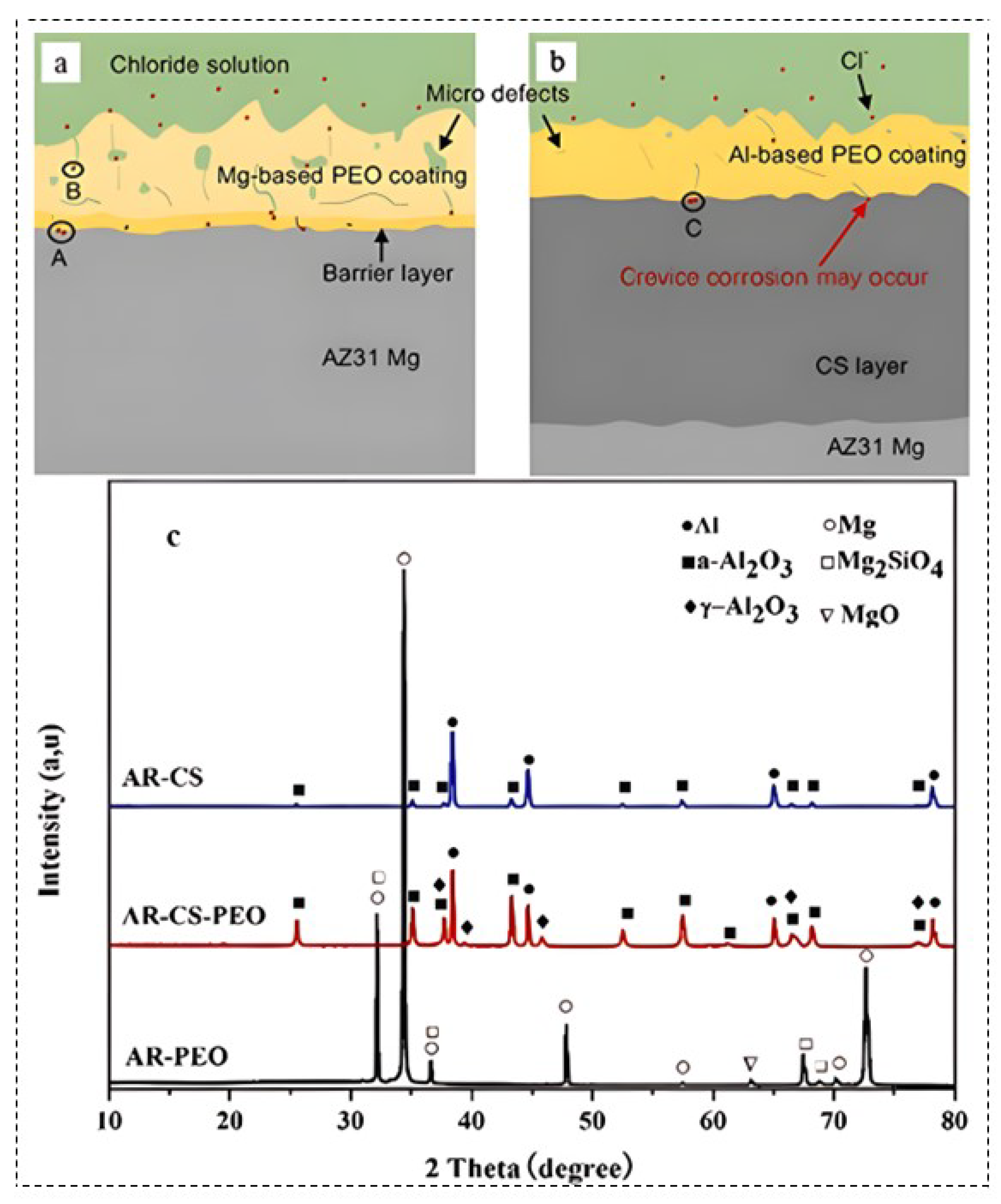

2.3. Cold Spray

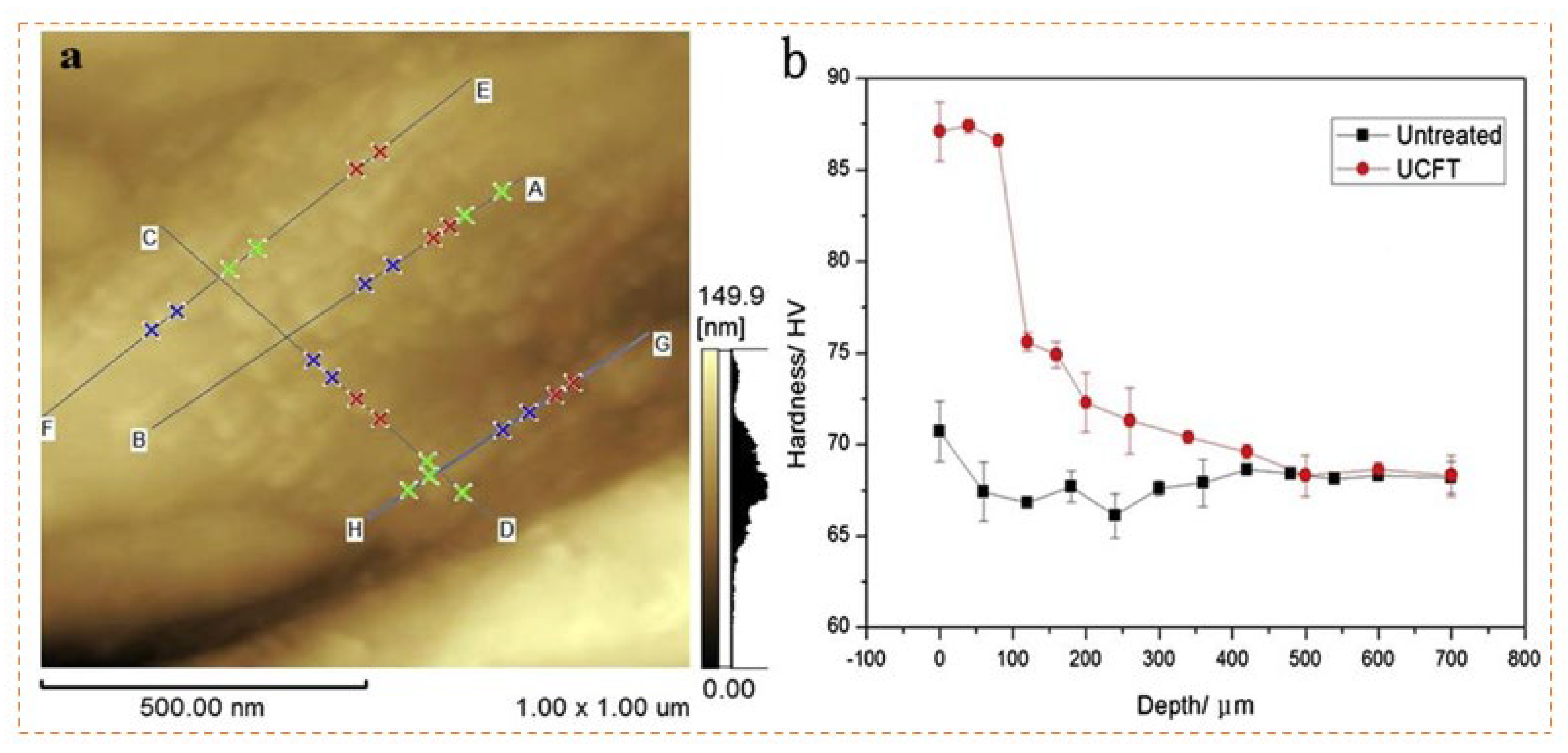

2.4. Other Treatments

2.4. Conclusions

3. Effect of Post-Processing on the Corrosion Resistance of MAO Coatings on Mg Alloys

3.1. Impregnation Treatment

3.2. Sol-Gel Treatment

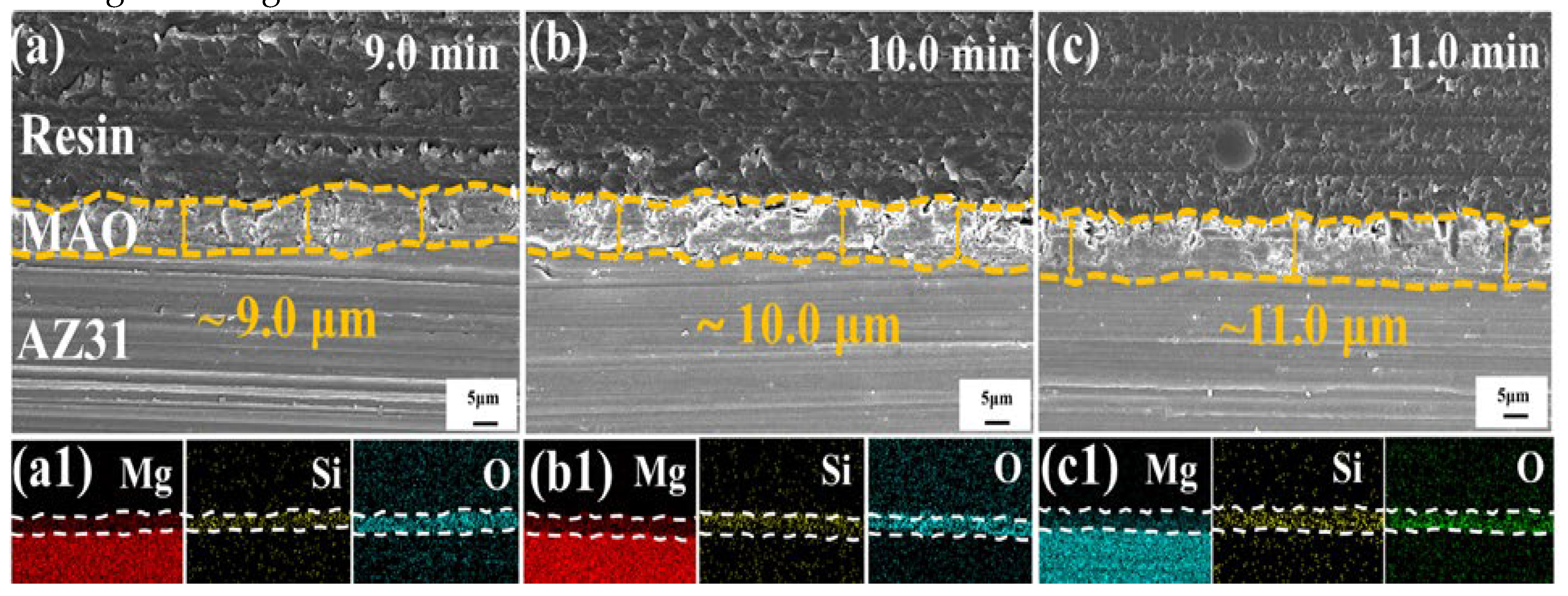

3.3. Hydrothermal Treatment

3.4. Spraying and Electrodeposition

3.5. Other Treatments

3.6. Conclusions

4. Summary and Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Chen, J.; Peng, X.; Chen, D.; Pan, F. Research advances in Mg and Mg alloys worldwide in 2020 J. Mg Alloys 2021, 9, 705–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.A.; Sachdev, A.K., 12 - Applications of Mg alloys in automotive engineering, in Advances in Wrought Mg Alloys, C. Bettles, M. Barnett Eds., Woodhead Publishing, 2012, pp. 393–426 978-1-84569-968-0. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Development and application of Mg alloy parts for automotive OEMs: A review J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, G.-d.; Liu, H.-f.; Liu, Y.-h. Effect of rare earth additions on microstructure and mechanical properties of AZ91 Mg alloys Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2010, 20, s336–s340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-Q.; Tong, P.-D.; Wang, L.; Qiu, Z.-H.; Li, J.-A.; Li, H.; Guan, S.-K.; Lin, C.-G.; Wang, H.-Y. One-step fabrication of self-healing poly(thioctic acid) coatings on ZE21B Mg alloys for enhancing corrosion resistance, anti-bacterial/oxidation, hemocompatibility and promoting re-endothelialization Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 451, 139096. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J., 1 - Metallic biomaterials: State of the art and new challenges, in Fundamental Biomaterials: Metals, P. Balakrishnan, S. M S, S. Thomas Eds., Woodhead Publishing, 2018, pp. 1–33 978-0-08-102205-4. [CrossRef]

- Sezer, N.; Evis, Z.; Kayhan, S.M.; Tahmasebifar, A.; Koç, M. Review of Mg-based biomaterials and their applications J. Mg Alloys 2018, 6, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Smith, C.; Sankar, J. Recent advances on the development of Mg alloys for biodegradable implants Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 4561–4573. [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, V.; Tardei, C.; Clicinschi, F.M. Biodegradable Mg alloys for orthopedic implants – A review J. Mg Alloys 2021, 9, 1884–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Zaky, S.; Ray, H.; Sfeir, C. Porous Mg/PLGA composite scaffolds for enhanced bone regeneration following tooth extraction Acta Biomater. 2015, 11, 543–553. [CrossRef]

- Kayhan, S.M.; Tahmasebifar, A.; Koç, M.; Usta, Y.; Tezcaner, A.; Evis, Z. Experimental and numerical investigations for mechanical and microstructural characterization of micro-manufactured AZ91D Mg alloy disks for biomedical applications Mater. Des. 2016, 93, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zheng, Y. Novel Mg Alloys Developed for Biomedical Application: A Review J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium orthophosphate coatings on Mg and its biodegradable alloys Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2919–2934. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, B.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, K.; Tan, L.; Zhang, Q. A novel design Mg alloy suture anchor promotes fibrocartilaginous enthesis regeneration in rabbit rotator cuff repair J. Mg Alloys 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Liang, H.; Liu, K.; Du, X.; Du, W. Recent progress of electrolytes for Mg-air batteries: A review J. Mg Alloys 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, D.; Lee, H.; Pyun, J.; Nimkar, A.; Shpigel, N.; Sharon, D.; Hong, S.-T.; Aurbach, D.; Chae, M.S. Mg alloys as alternative anode materials for rechargeable Mg-ion batteries: Review on the alloying phase and reaction mechanisms J. Mg Alloys 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, M. Mars transportation vehicle concept Acta Astronaut. 2014, 103, 250–256. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Pan, F. A review on electromagnetic shielding Mg alloys J. Mg Alloys 2021, 9, 1906–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ma, Y.; Fan, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Investigation of anti-corrosion property of hybrid coatings fabricated by combining PEC with MAO on pure Mg J. Mg Alloys 2022, 10, 2875–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Jin, L.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, F.; Dong, S.; Dong, J. Development of high-strength Mg alloys with excellent ignition-proof performance based on the oxidation and ignition mechanisms: A review J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xu, C.; Hu, X.; Gan, W.; Wu, K.; Wang, X. Improving the Young's modulus of Mg via alloying and compositing – A short review J. Mg Alloys 2022, 10, 2009–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.M.; Caris, J.; Luo, A.A. Towards high strength cast Mg-RE based alloys: Phase diagrams and strengthening mechanisms J. Mg Alloys 2022, 10, 1401–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, C.; Sun, M.; Ding, W. Recent developments and applications on high-performance cast Mg rare-earth alloys J. Mg Alloys 2021, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramuthuvel, P.; Shankar, K.; Sairajan, K.K. Application of particle damper on electronic packages for spacecraft Acta Astronaut. 2016, 127, 260–270. [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, Y.; Nakasuka, S.; Higashi, K.; Kobayashi, C.; Koyama, K.; Okada, T. Structure and thermal control of panel extension satellite (PETSAT) Acta Astronaut. 2009, 65, 958–966. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Ren, W.; NuLi, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, J. Recent progress on selenium-based cathode materials for rechargeable Mg batteries: A mini review J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 91, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Han, S.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H. Evolution, limitations, advantages, and future challenges of Mg alloys as materials for aerospace applications J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1008, 176707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Nishimoto, M.; Muto, I.; Sugawara, Y. Fabrication of a model specimen for understanding micro-galvanic corrosion at the boundary of α-Mg and β-Mg17Al12 J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, J.P. The role of the Mg17Al12-phase in the high-pressure die-cast Mg-aluminum alloy system J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 4235–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-q.; Tong, Z.-p.; He, Y.-b.; Huang, H.-p.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, P. Comparison on corrosion resistance and surface film of pure Mg and Mg−14Li alloy Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 2413–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaedi, Z.; Mirzadeh, H.; Aghdam, R.M.; Mahmudi, R. Thermal stability, grain growth kinetics, mechanical properties, and bio-corrosion resistance of pure Mg, ZK30, and ZEK300 alloys: A comparative study Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.-c.; Zhang, J.; Huang, W.-j.; Dietzel, W.; Kainer, K.U.; Blawert, C.; Ke, W. Review of studies on corrosion of Mg alloys Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2006, 16, s763–s771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Hou, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B.; Jia, J.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Y. Tailoring the micromorphology of the as-cast Mg–Sn–In alloys to corrosion-resistant microstructures via adjusting In concentration J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 811, 152024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, J. Effects of calcium addition on phase characteristics and corrosion behaviors of Mg-2Zn-0.2Mn-xCa in simulated body fluid J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 728, 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, H. Effects of Zn content on microstructure, mechanical and degradation behaviors of Mg-xZn-0.2Ca-0.1Mn alloys Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 241, 122441. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, L.; Hou, Y.; Duan, G.; Yu, B.; Li, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. Grain refinement promotes the formation of phosphate conversion coating on Mg alloy AZ91D with high corrosion resistance and low electrical contact resistance Corrosion Communications 2021, 1, 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Bai, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, L.; Guo, H.; Lei, B.; Meng, G.; Yang, Z.; Feng, Z. Development of an eco-friendly waterborne polyurethane/catecholamine/sol-gel composite coating for achieving long-lasting corrosion protection on Mg alloy AZ31 Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 183, 107732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yang, Y.; Wen, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, G.; Jiang, B.; Peng, X.; Pan, F. Applications of Mg alloys for aerospace: A review J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 3609–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, F.Z.; Sarraf, M.; Ghomi, E.R.; Kumar, V.V.; Salehi, M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Bae, S. A state-of-the-art review on recent advances in the fabrication and characteristics of Mg-based alloys in biomedical applications J. Mg Alloys 2024, 12, 2569–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, T.a. Development of aqueous Mg–air batteries: From structure to materials J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 988, 174262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, J.T.; Lai, S.H.S.; Tang, C.Q.Y.; Thevendran, G. Mg-based bioabsorbable screw fixation for hallux valgus surgery – A suitable alternative to metallic implants Foot and Ankle Surgery 2019, 25, 727–732. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.C.; Cui, L.Y.; Ke, W.Biomedical Mg Alloys: Composition, Microstructure and Corrosion ACTA METALLURGICA SINICA 2018, 54, 1215–1235. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Gao, H.; Hu, J.; Gao, L. Effect of pH value on the corrosion and corrosion fatigue behavior of AM60 Mg alloy J. Mater. Res. 2019, 34, 1054-1063. [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Lukas, H.L.; Effenberg, G.; Petzow, G. Thermodynamic optimization of the Mg-Y system Calphad 1988, 12, 375–381. [CrossRef]

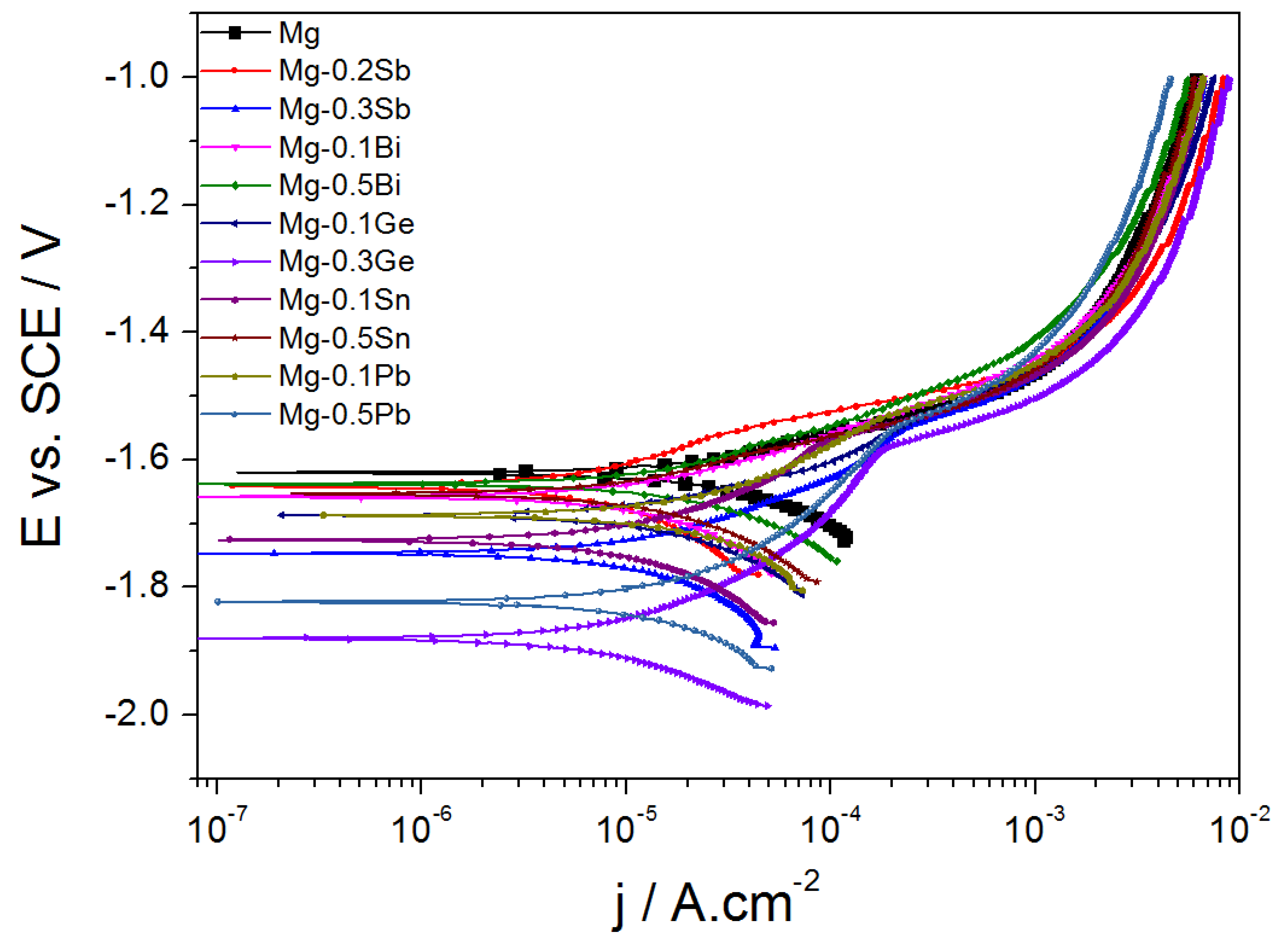

- Liu, R.L.; Scully, J.R.; Williams, G.; Birbilis, N. Reducing the corrosion rate of Mg via microalloying additions of group 14 and 15 elements Electrochim. Acta 2018, 260, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, K.; Dabalà, M.; Calliari, I.; Magrini, M. Effect of HCl pre-processing on corrosion resistance of cerium-based conversion coatings on Mg and Mg alloys Corrosion Science 2005, 47, 989–1000. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wu, S.; Luo, J.; Fukuda, Y.; Nakae, H. A chromium-free conversion coating of Mg alloy by a phosphate–permanganate solution Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 5407–5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. A facile fabrication of Ag/SiC composite coating with high mechanical properties and corrosion resistance by electroless plating Materials Today Communications 2023, 36, 106737. [CrossRef]

- Dabalà, M.; Brunelli, K.; Napolitani, E.; Magrini, M. Cerium-based chemical conversion coating on AZ63 Mg alloy Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 172, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., 17 - Sol-gel coatings to improve the corrosion resistance of Mg (Mg) alloys, in Corrosion Prevention of Mg Alloys, G.-L. Song Ed., Woodhead Publishing, 2013, pp. 469–485 978-0-85709-437-7. [CrossRef]

- Nezamdoust, S.; Seifzadeh, D.; Rajabalizadeh, Z. Application of novel sol–gel composites on Mg alloy J. Mg Alloys 2019, 7, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Y.; Durán, A.Control of degradation rate of Mg alloys using silica sol–gel coatings for biodegradable implant materials J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 198-208.

- Wang, Z.C.; Yu, L.; Qi, Z.B.; Song, G.L., 13 - Electroless nickel-boron plating to improve the corrosion resistance of Mg (Mg) alloys, in Corrosion Prevention of Mg Alloys, G.-L. Song Ed., Woodhead Publishing, 2013, pp. 370–392 978-0-85709-437-7. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.-H.; Xu, D.; Shu, Y.; Yong, Q.; Wu, L.; Yu, G. Environmentally friendly and facile Mg(OH)2 film for electroless nickel plating on Mg alloy for enhanced galvanic corrosion inhibition Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 478, 130371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Yao, G.; Hua, Z. Electroless Ni–P plating on Mg–10Li–1Zn alloy J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 474, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Easton, M.A.; Birbilis, N.; Yang, H.Y.; Abbott, T.B., 11 - Corrosion-resistant electrochemical plating of Mg (Mg) alloys, in Corrosion Prevention of Mg Alloys, G.-L. Song Ed., Woodhead Publishing, 2013, pp. 315–346 978-0-85709-437-7. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.X.; Yan, S.F.; Li, Z.L.; Wang, Z.G.; Yang, A.; Ma, W.; Chen, W.D.; Qu, Y.H.Influence of Anodic Oxidation on the Organizational Structure and Corrosion Resistance of Oxide Film on AZ31B Mg Alloy COATINGS 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Vangölü, Y.; Bozkurt, Y.B.; Kovacı, H.; Çelik, A. A comparative study of the bio-tribocorrosion behaviour of PEO coated AZ31 Mg alloy in SBF: Assessing the effect of B, Cu and Zn doping Ceramics International 2023, 49, 19513–19522. [CrossRef]

- Bordbar-Khiabani, A.; Yarmand, B.; Mozafari, M. Effect of ZnO pore-sealing layer on anti-corrosion and in-vitro bioactivity behavior of plasma electrolytic oxidized AZ91 Mg alloy Materials Letters 2020, 258, 126779. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Safira, A.R.; Aadil, M.; Kaseem, M. Development of anti-corrosive coating on AZ31 Mg alloy modified by MOF/LDH/PEO hybrids J. Mg Alloys 2024, 12, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z. Corrosion behavior and incorporation mechanism of Y2O3-TiO2 composite coatings fabricated on TC4 titanium alloy by plasma electrolytic oxidation Chem. Phys. Lett. 2024, 841, 141170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-p.; Meng, X.-z.; Li, X.-r.; Li, Z.-x.; Yan, H.-j.; Wu, L.-k.; Cao, F.-h. Effect of electrolyte composition on corrosion behavior and tribological performance of plasma electrolytic oxidized TC4 alloy Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, R.; Si, T.; Li, Y.; Qian, W.; Gao, G.; Chen, Y. Effect of Al2O3 nanoparticles additions on wear resistance of plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings on TC4 alloys Ceramics International 2024, 50, 18484–18496. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Z. Microstructure and Corrosion Resistance of Plasma Electrolytic Oxidized Recycled Mg Alloy Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2022, 35, 961-974. [CrossRef]

- Nachtsheim, J.; Ma, S.; Burja, J.; Batič, B.Š.; Markert, B. Tuning the long-term corrosion behaviour of biodegradable WE43 Mg alloy by PEO coating Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 474, 130115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, T.; Dikici, B.; Dafali, A.; Kaseem, M. Chromophores assisted phytochemicals and pheromones coatings on porous inorganic layers for enhancing anti-corrosion and photocatalytic properties Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 182, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

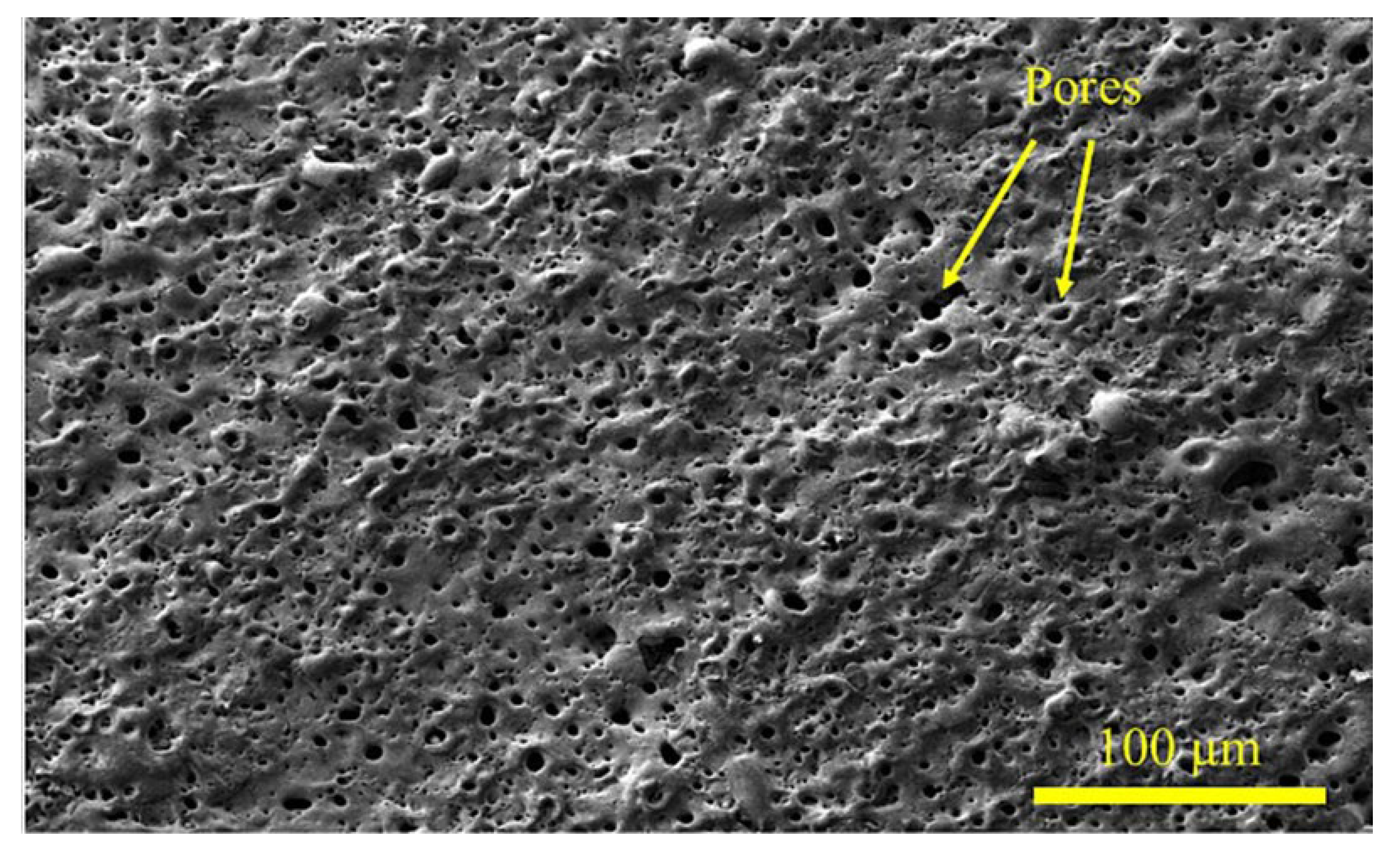

- Barati Darband, G.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Hamghalam, P.; Valizade, N. Plasma electrolytic oxidation of Mg and its alloys: Mechanism, properties and applications J. Mg Alloys 2017, 5, 74–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Rodrigues, J.; Marasca Antonini, L.; da Cunha Bastos, A.A.; Zhou, J.; de Fraga Malfatti, C. Corrosion resistance and tribological behavior of ZK30 Mg alloy coated by plasma electrolytic oxidation Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 410, 126983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrabal, R.; Matykina, E.; Viejo, F.; Skeldon, P.; Thompson, G.E. Corrosion resistance of WE43 and AZ91D Mg alloys with phosphate PEO coatings Corrosion Science 2008, 50, 1744–1752. [CrossRef]

- Anawati, A.; Hidayati, E.; Purwanto, S. Effect of Cation Incorporation in the Plasma Electrolytic Oxide Layer Formed on AZ31 Mg Alloy Applied Surface Science Advances 2023, 17, 100444. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ke, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sui, M. Self-repairing capability of Mg alloy during the plasma electrolytic oxidation process J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 766, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvani, A.; Kamkar, N.; Chaharmahali, R.; Bahamirian, M.; Kaseem, M.; Fattah-alhosseini, A. Improving anti-corrosion properties AZ31 Mg alloy corrosion behavior in a simulated body fluid using plasma electrolytic oxidation coating containing hydroxyapatite nanoparticles Inorganic Chemistry Communications 2023, 158, 111470. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-Y.; Chu, Y.-R.; Yang, S.-H.; Lee, Y.-L. Effect of pause time on microstructure and corrosion resistance in AZ31 Mg Alloy's MAO coating Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 475, 130164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, P.; Ji, W.; Chen, R. Effect of adding Sr(OH)2 on the formation process of 2024 aluminum alloy MAO coatings Materials Letters 2024, 377, 137522. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Ma, X.; Wu, R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Krit, B.; Betsofen, S.; Liu, B. Advances in MAO coatings on Mg-Li alloys Applied Surface Science Advances 2022, 8, 100219. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Dong, Z.; Hashimoto, T.; Zhou, X. Enhanced corrosion resistance of AZ31 Mg alloy by one-step formation of PEO/Mg-Al LDH composite coating Corrosion Communications 2022, 6, 67–83. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Seo, E.; Lee, M.; Kim, D. Fabrication of a CuO composite PEO and effect of post-processing on improving its thermal properties and corrosion resistance of Mg alloy AZ31 Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 447, 128828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Cai, Q.; Wei, B.; Yu, B.; Li, D.; He, J.; Liu, Z. Effect of (NaPO3)6 concentrations on corrosion resistance of plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings formed on AZ91D Mg alloy J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 464, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Liu, X.; Ding, C. In vitro degradation behavior and cytocompatibility of biodegradable AZ31 alloy with PEO/HT composite coating Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2015, 128, 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ouyang, K.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J. Influence of Y2O3/Nd2O3 Particles Additive on the Corrosion Resistance of MAO Coating on AZ91D Mg Alloy International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2017, 12, 2400–2411. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Sheng, L.; Zhao, C.; Chen, P.; Ouyang, W.; Xu, D.; Zheng, Y.; Chu, P.K. Improved lubricating and corrosion resistance of MAO coatings on ZK61 Mg alloy by co-doping with graphite and nano-zirconia J. Mater. Res. and Technology 2024, 33, 2275–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, C. Research status of Mg alloys by MAO: a review Surface Engineering 2017, 33, 731–738. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cai, Q.; Lian, Z.; Yu, Z.; Ren, W.; Yu, H. Research Progress on Corrosion Resistance of Mg Alloys with Bio-inspired Water-repellent Properties: A Review Journal of Bionic Engineering 2021, 18, 735-763. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhenxing, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Wu, Z.Structure and Corrosion Resistance of PEO Ceramic Coatings on AZ91D Mg Alloy Under Three Kinds of Power Modes International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology 2013, 10,.

- Yao, Z.; Wang, D.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, F. Effect of PEO power modes on structure and corrosion resistance of ceramic coatings on AZ91D Mg alloy Surface Engineering 2012, 28, 96-101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.F.; Shan, D.Y.; Chen, R.S.; Han, E.H. Effects of electric parameters on properties of anodic coatings formed on Mg alloys Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008, 107, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Lu, J.; Yin, X.; Jiang, J.; Wang, J. The effect of pulse frequency on the electrochemical properties of micro arc oxidation coatings formed on Mg alloy J. Mg Alloys 2013, 1, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; LÜ, G.-h.; Zhang, G.-l.; Tian, Y.-y. Effect of current frequency on properties of coating formed by microarc oxidation on AZ91D Mg alloy Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 1500–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximei, W.; Liqun, Z.; Huicong, L.; Weiping, L. Influence of surface pretreatment on the anodizing film of Mg alloy and the mechanism of the ultrasound during the pretreatment Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 4210–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama Krishna, L.; Poshal, G.; Jyothirmayi, A.; Sundararajan, G. Compositionally modulated CGDS+MAO duplex coatings for corrosion protection of AZ91 Mg alloy J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 578, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.-Y.; Gao, S.-D.; Li, P.-P.; Zeng, R.-C.; Zhang, F.; Li, S.-Q.; Han, E.-H. Corrosion resistance of a self-healing MAO/polymethyltrimethoxysilane composite coating on Mg alloy AZ31 Corrosion Science 2017, 118, 84–95. [CrossRef]

- Mohedano, M.; Blawert, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L. Cerium-based sealing of PEO coated AM50 Mg alloy Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 269, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Shin, S.H.; Hussain, I.; Koo, B.H. Structure and corrosion properties of the two-step PEO coatings formed on AZ91D Mg alloy in K2ZrF6-based electrolyte solution Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 307, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-q.; Wang, S.-r.; Yang, X.-f.; Wen, D.-s.; Guo, Y. Microstructure, mechanical properties and fretting corrosion wear behavior of biomedical ZK60 Mg alloy treated by laser shock peening Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 1715–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Hu, Q.; Song, R.; Hu, X. LSP/MAO composite bio-coating on AZ80 Mg alloy for biomedical application Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 75, 1299–1304. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Shen, Y.; He, L.; Yang, Z.; Song, R. Stress corrosion cracking behavior of LSP/MAO treated Mg alloy during SSRT in a simulated body fluid J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 822, 153707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.C.; Zhou, W.; Li, Z.L.; Zheng, H.Y. Study on the solidification microstructure in AZ91D Mg alloy after laser surface melting Applied Surface Science 2009, 255, 8235–8238. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.C.; Raman, R.K.S.; Durandet, Y.; McAdam, G. Electrochemical investigation of the influence of laser surface melting on the microstructure and corrosion behaviour of ZE41 Mg alloy – An EIS based study Corrosion Science 2011, 53, 1505–1514. [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.-j.; Cheng, Y.-l.; Liu, Y.-y.; Zhu, Z.-d.; Cheng, Y.-l. Corrosion and wear resistance of AZ31 Mg alloy treated by duplex process of magnetron sputtering and plasma electrolytic oxidation Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 2287–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.-f.; Wei, B.-j.; Cheng, Y.-l.; Cheng, Y.-l. Discharge channel structure revealed by plasma electrolytic oxidation of AZ31Mg alloy with magnetron sputtering Al layer and corrosion behaviors of treated alloy Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2024, 34, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Ramachandran, C.S. Abrasion, sliding wear, corrosion, and cavitation erosion characteristics of a duplex coating formed on AZ31 Mg alloy by sequential application of cold spray and plasma electrolytic oxidation techniques Materials Today Communications 2021, 26, 101978. [CrossRef]

- Li Zhongsheng; Wu Ranger; Ding Star; Huang An-tai; Song Kaiqiang; Zhan Qingqing; Corrosion Resistance of Aluminum/Micro Arc Oxidation Composite Coatings for Cold Spraying on the Surface of Tuandalong AZ80. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 49, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Peral, L.B.; Zafra, A.; Bagherifard, S.; Guagliano, M.; Fernández-Pariente, I. Effect of warm shot peening treatments on surface properties and corrosion behavior of AZ31 Mg alloy Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 401, 126285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Shao, W.; Tang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Z. Correlation between shot peening coverage and surface microstructural evolution in AISI 9310 steel: An EBSD and surface morphology analysis Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.-M.; Song, G.-H.; Suh, M.-S.; Pyoun, Y.-S. Fatigue and mechanical characteristics of nano-structured tool steel by ultrasonic cold forging technology Materials Science and Engineering: A 2007, 443, 101–106. [CrossRef]

- Kajánek, D.; Pastorek, F.; Hadzima, B.; Bagherifard, S.; Jambor, M.; Belány, P.; Minárik, P. Impact of shot peening on corrosion performance of AZ31 Mg alloy coated by PEO: Comparison with conventional surface pre-processings Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 446, 128773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gu, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Hou, B.; Liu, Q.; Ding, H. Effect of ultrasonic cold forging technology as the pretreatment on the corrosion resistance of MAO Ca/P coating on AZ31B Mg alloy J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 635, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, H.; S, G.; S, A.; M, A.; N, R. Fabrication of duplex coatings on biodegradable AZ31 Mg alloy by integrating cerium conversion (CC) and plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) processes J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 722, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Liang, J.; Chen, J. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of plasma electrolytic oxidation coated Mg alloy pre-treated by laser surface melting Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 206, 3109–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liang, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, L. Characterization of AZ31 Mg alloy by duplex process combining laser surface melting and plasma electrolytic oxidation Applied Surface Science 2016, 382, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ynag, S. Enhanced bond strength for MAO coating on Mg alloy via laser surface microstructuring Applied Surface Science 2019, 478, 866–871. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Wen, C.; Ang, H.Q. Influence of laser parameters on the microstructures and surface properties in laser surface modification of biomedical Mg alloys J. Mg Alloys 2024, 12, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta Majumdar, J.; Galun, R.; Mordike, B.L.; Manna, I. Effect of laser surface melting on corrosion and wear resistance of a commercial Mg alloy Materials Science and Engineering: A 2003, 361, 119–129. [CrossRef]

- Fattah-alhosseini, A.; Chaharmahali, R. Impressive strides in amelioration of corrosion behavior of Mg-based alloys through the PEO process combined with surface laser process: A review J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 4390–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Wang, Y.; Yue, J.; Cao, C.; Li, K.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, Z. Recent progress in laser shock peening: Mechanism, laser systems and development prospects Surfaces and Interfaces 2024, 44, 103757. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, W. Improving corrosion resistance of AZ91D Mg alloy by laser surface melting and MAO MATERIALS AND CORROSION-WERKSTOFFE UND KORROSION 2015, 66, 963-970. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, L.; Qian, J.; Qu, W.; Luo, R.; Wu, F.; Chen, R. Materials and structure engineering by magnetron sputtering for advanced lithium batteries Energy Storage Materials 2021, 39, 203–224. [CrossRef]

- Birks, N.; Meier, G.H.; Pettit, F.S. , Introduction to the High Temperature Oxidation of Metals, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006, ISBN 9780521480420 DOI.

- Lv, D.; Zhang, T.; Gong, F. Study on Properties of Cold-Sprayed Al-Zn Coating on S135 Drill Pipe Steel Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 2020, 9209465. [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Fan, N.; Huang, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lupoi, R.; Li, W. Towards high-strength cold spray additive manufactured metals: Methods, mechanisms, and properties J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 170, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadi, H.; Kreye, H.; Gärtner, F.; Klassen, T. Cold spraying – A materials perspective Acta Materialia 2016, 116, 382–407. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Ma, H.; Yue, W.; Tian, B.; Chen, L.; Mao, D. Microstructure and corrosion model of MAO coating on nano grained AA2024 pretreated by ultrasonic cold forging technology J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 681, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffini, A.F.; Barella, S.; Martinez, L.B.P.; Mapelli, C.; Pariente, I.F. Influence of Microstructure and Shot Peening Treatment on Corrosion Resistance of AISI F55-UNS S32760 Super Duplex Stainless Steel MATERIALS 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

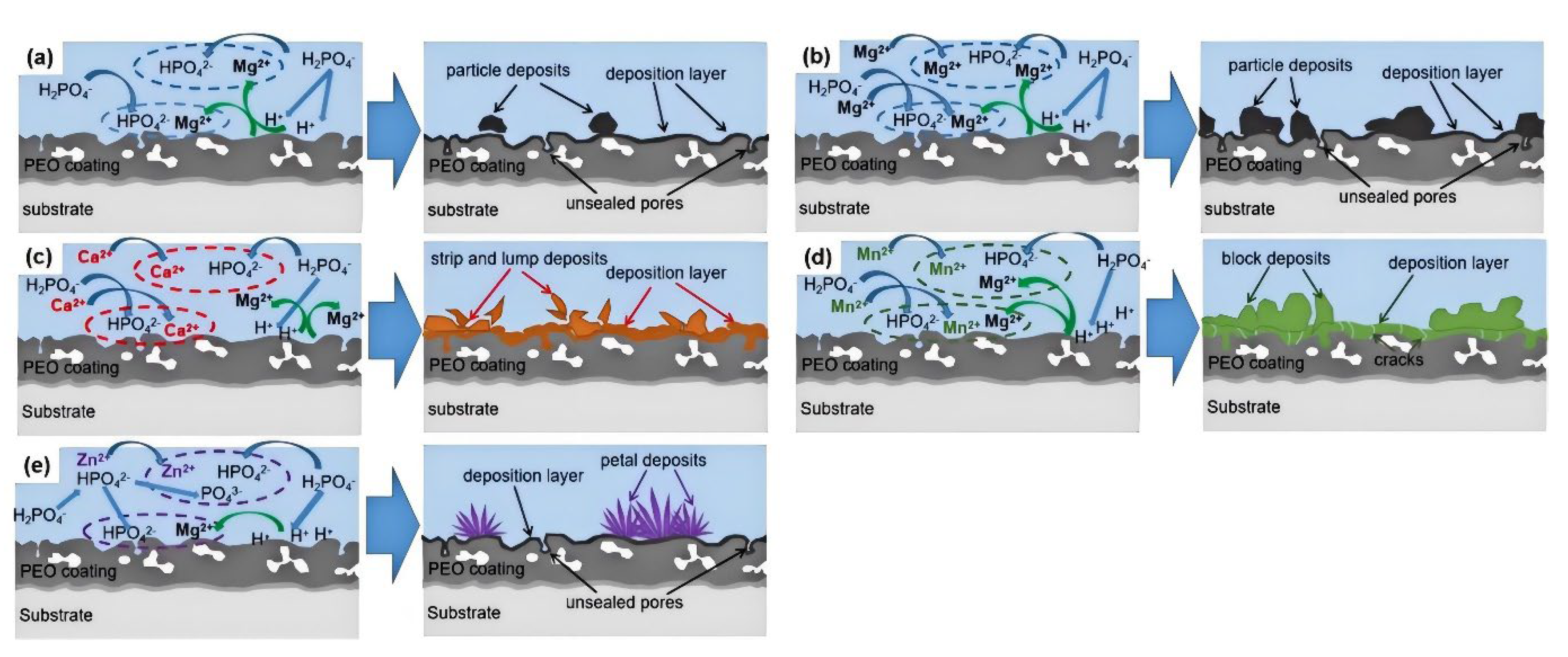

- Qian, K.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Xia, D.; Ju, J.; Xue, F.; Chu, C.; Bai, J. Corrosion prevention for PEO-coated Mg by phosphate-based sealing treatment with added cation Applied Surface Science 2023, 629, 157351. [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Q.; Shao, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Ju, J.; Xue, F.; Chu, C.; Xia, D.; Bai, J. Enhancement of corrosion resistance and antibacterial properties of PEO coated AZ91D Mg alloy by copper- and phosphate-based sealing treatment Corrosion Science 2023, 219, 111218. [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Li, W.; Lu, X.; Han, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. Effect of phosphate-based sealing treatment on the corrosion performance of a PEO coated AZ91D mg alloy J. Mg Alloys 2020, 8, 1328–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohedano, M.; Pérez, P.; Matykina, E.; Pillado, B.; Garcés, G.; Arrabal, R. PEO coating with Ce-sealing for corrosion protection of LPSO Mg–Y–Zn alloy Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 383, 125253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzato, L.; Babbolin, R.; Cerchier, P.; Marigo, M.; Dolcet, P.; Dabalà, M.; Brunelli, K. Sealing of PEO coated AZ91Mg alloy using solutions containing neodymium Corrosion Science 2020, 173, 108741. [CrossRef]

- Mingo, B.; Arrabal, R.; Mohedano, M.; Llamazares, Y.; Matykina, E.; Yerokhin, A.; Pardo, A. Influence of sealing post-processings on the corrosion resistance of PEO coated AZ91 Mg alloy Applied Surface Science 2018, 433, 653–667. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Matthews, A.; Yerokhin, A. Plasma electrolytic oxidation coatings on cp-Mg with cerium nitrate and benzotriazole immersion post-processings Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 344, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, N.V.; Fazal, B.R.; Moon, S. Cerium- and phosphate-based sealing treatments of PEO coated AZ31 Mg alloy Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 309, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yong, Q.; Wu, L.; Yu, G.; Xie, Z.-H. Cerium nitrate and stearic acid modified corrosion-resistant MAO coating on Mg alloy Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 478, 130461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, C.; Lok-Wang Ma, R.; Ming-Fai Yuen, M. Preparation and microstructure of MAO/CS composite coatings on Mg alloy Materials Letters 2020, 271, 127729. [CrossRef]

- Štrbák, M.; Pastorek, F.; Scheber, P. Corrosion behaviour of PEO coating sealed by water based preservative containing corrosion inhibitors Transportation Research Procedia 2021, 55, 752–759. [CrossRef]

- Pak, S.-N.; Jiang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Ju, J.-M.; Ju, K.-S.; Pak, U.-J. Fabrication of environmentally friendly anti-corrosive composite coatings on AZ31B Mg alloy by plasma electrolytic oxidation and phytic acid/3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane post-processing Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 325, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnedenkov, A.S.; Sinebryukhov, S.L.; Mashtalyar, D.V.; Gnedenkov, S.V. Protective properties of inhibitor-containing composite coatings on a Mg alloy Corrosion Science 2016, 102, 348–354. [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Liang, L.-X.; Cheng, S.-C.; Liu, H.-P.; Cui, L.-Y.; Zeng, R.-C.; Li, S.-Q.; Wang, Z.-L. Corrosion resistance, antibacterial activity and drug release of ciprofloxacin-loaded MAO/silane coating on Mg alloy AZ31 Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 158, 106357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toorani, M.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Mahdavian, M.; Naderi, R. Effective PEO/Silane pretreatment of epoxy coating applied on AZ31B Mg alloy for corrosion protection Corrosion Science 2020, 169, 108608. [CrossRef]

- Talha, M.; Ma, Y.C.; Xu, M.J.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Y.H.; Kong, X.W. Recent Advancements in Corrosion Protection of Mg Alloys by Silane-Based Sol-Gel Coatings INDUSTRIAL & ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY RESEARCH 2020, 59, 19840-19857. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, F.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, M. The corrosion resistance of SiO2-hexadecyltrimethoxysilane hydrophobic coating on AZ91 alloy pretreated by plasma electrolytic oxidation Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 174, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnedenkov, S.V.; Sinebryukhov, S.L.; Mashtalyar, D.V.; Imshinetskiy, I.M. Composite fluoropolymer coatings on Mg alloys formed by plasma electrolytic oxidation in combination with electrophoretic deposition Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 283, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar Khiabani, A.; Rahimi, S.; Yarmand, B.; Mozafari, M. Electrophoretic deposition of graphene oxide on plasma electrolytic oxidized-Mg implants for bone tissue engineering applications Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 15603–15612. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tan, J.; Du, H.; Qian, S.; Liu, X. Comparison study of Mg(OH)2, Mg-Fe LDH, and FeOOH coatings on PEO-treated Mg alloy in anticorrosion and biocompatibility Applied Clay Science 2022, 225, 106535. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wu, L.; Ci, W.; Yao, W.; Yuan, Y.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, B.; Wang, J.; Andrej, A.; Pan, F. Dual self-healing effects of salicylate intercalated MgAlY-LDHs film in-situ grown on the MAO coating on AZ31 alloys Corrosion Science 2023, 220, 111285. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, X.; Tong, G.; Zhang, L. Microstructure and corrosion behavior of PEO-LDHs-SDS superhydrophobic composite film on Mg alloy Corrosion Science 2022, 208, 110699. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Chen, C.; Guo, H.; Lei, B.; Zhang, P.; Meng, G.; Feng, Z. Dopamine self-polymerized sol-gel coating for corrosion protection of AZ31 Mg Alloy Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2023, 666, 131283. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Du, J.; Sang, J.; Hirahara, H.; Aisawa, S.; Chen, D. Superhydrophobic coatings by electrodeposition on Mg–Li alloys: Attempt of armor-like Ni patterns to improve the robustness Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 304, 127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Pandel, U.; Sharma, S. A study of investigating the effects of variables and assessing the efficiency of air plasma spray as a coating technique Materials Today: Proceedings 2023. [CrossRef]

- Küçükosman, R.; Emine Şüküroğlu, E.; Totik, Y.; Şüküroğlu, S. Investigation of wear behavior of graphite additive composite coatings deposited by micro arc oxidation-hydrothermal treatment on AZ91 Mg alloy Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 22, 100894. [CrossRef]

- Kaseem, M.; Zehra, T.; Hussain, T.; Ko, Y.G.; Fattah-alhosseini, A. Electrochemical response of MgO/Co3O4 oxide layers produced by plasma electrolytic oxidation and post-processing using cobalt nitrate J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Song, X.; Liu, C.-B.; Cui, L.-Y.; Li, S.-Q.; Zhang, F.; Bobby Kannan, M.; Chen, D.-C.; Zeng, R.-C. Corrosion resistance and mechanisms of Nd(NO3)3 and polyvinyl alcohol organic-inorganic hybrid material incorporated MAO coatings on AZ31 Mg alloy Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 630, 833–845. [CrossRef]

- Farshid, S.; Kharaziha, M.; Atapour, M. A self-healing and bioactive coating based on duplex plasma electrolytic oxidation/polydopamine on AZ91 alloy for bone implants J. Mg Alloys 2023, 11, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jing, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, M. Composite coatings on a Mg–Li alloy prepared by combined plasma electrolytic oxidation and sol–gel techniques Corrosion Science 2012, 63, 358–366. [CrossRef]

- Malayoglu, U.; Tekin, K.C.; Shrestha, S. Influence of post-processing on the corrosion resistance of PEO coated AM50B and AM60B Mg alloys Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 205, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekkhouyan, R.; Van Renterghem, L.; Bonnaud, L.; Paint, Y.; Gonon, M.; Cornil, D.; Cornil, J.; Raquez, J.-M.; Olivier, M.-G. Effect of surface pretreatment on the production of LDH for post-processing with benzoxazine resin Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 479, 130538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroonparvar, M.; Mat Yajid, M.A.; Kumar Gupta, R.; Mohd Yusof, N.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Ghandvar, H.; Ghasemi, E. Antibacterial activities and corrosion behavior of novel PEO/nanostructured ZrO2 coating on Mg alloy Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2018, 28, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Uchikoshi, T. Novel synthesized alumino-silicate geopolymer suitably used for electrophoretic deposition process (EPD) as an inorganic binder Advanced Powder Technology 2023, 34, 104236. [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. Ion-substituted calcium phosphate coatings by physical vapor deposition magnetron sputtering for biomedical applications: A review Acta Biomater. 2019, 89, 14–32. [CrossRef]

| Substrate | Electrolyte | Electrical parameters | Substrate | MAO | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecorr/V | Icorr(μA/cm2) | Ecorr/V | Icorr(μA/cm2) | |||||

| AZ31 | 12g/L Na3PO4∙12H2O +6g/LNaOH |

Voltage:400 V Duty cycle: 10% Frequency:100 Hz Oxidation time:600 s |

-1.57 | 151 | -1.51 | 0.017 | [76] | |

| AZ31 | 15 g/L Na2SiO3 +5 g/LKF | Voltage:430V Oxidation time:15min Temperature:20℃ |

-1.48 | 3.77 | -1.42 | 0.031 | [77] | |

| AZ31 | 10g/L Na2SiO3; 4 g/L NaOH; 5 g/L NaF 5g/L的(NaPO3)6 |

Voltage:400 V; frequency:1000 Hz; duty cycle:10%, temperature: 20 - 40 ℃, time 10 min |

-1.21 | 26.72 | -1.425 | 0.034 | [78] | |

| AZ31 | 0.04M Na2SiO3· H2O, 0.1 M KOH + 0.2 M KF·2H2O. |

Current density:50 mA/cm2 frequency:300 Hz duty cycle:10% time:15 min. |

-1.51 | 14.02 | -1.64 | 0.047 | [79] | |

| AZ31 | 3g/L Na3PO4⋅12H2O +3g/LKOH +2g/LZnO +3g/LHA | Current density:300mA/m2 Time:7 min frequency:1000 Hz duty cycle:50% |

-1.54 | 7.034 | -1.156 | 0.034 | [72] | |

| AZ91D | 25g/L Na2SiO3.9H2O + 20g/L KOH + 5g/L KF. 2H2O + 5g/L C6H5Na3O7 . 2H2O + 10mL/L+5g/L Y2O3 C3H8O3, PH=14 |

Current density:50mA/cm2, the duty cycle :10%, the frequency: 300Hz, the temperature :20 and 30℃ |

-1.55 | 37 | -1.391 | 0.053 | [80] | |

| ZK61 | 20 g·L-1 (NaPO3)6 +3 g·L-1 NaOH+5 g·L-1 EDTA-2Na, and 5 g·L-1 NaF |

current density = 5A·dm-2, frequency = 200 Hz, duty cycle = 15%, discharge time = 10 min |

-1.53 | 112.1 | -1.482 | 6.327 | [81] | |

| Substrate | MAO Film Composition |

MAO coatings | Pre-processing Method |

MAO coatings with Pre-processing | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ecorr (V) |

Icorr (A/cm2) |

Ecorr (V) |

Icorr (A/cm2) |

||||

| AZ31 | CS | -1.15 | 5.18×10-7 | [101] | |||

| AZ31 | -1.611 | 7.11×10-7 | SP | -1.62 | 2.14×10-7 | [106] | |

| AZ31 | MS | -1.46 | 1.552×10-6 | [99] | |||

| AZ31 | MS | -1.25 | 3.93×10-6 | [100] | |||

| AZ31B | Mg, Mg3(PO4) 2, TCP (tricalcium phosphate–whitlockite, Ca3(PO4)2), DCPD (calcium phosphate dehydrate–brushite, CaHPO4·2H2O), HA (hydroxyapatite, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), MgO and MgAl2O4 |

-1.415 | 18.6×10-6 | UCFT | -1.31 | 9.20×10-6 | [107] |

| AZ31 | Mg, Mg2SiO4 | -0.395 | 0.34×10-6 | CCP | -0.25 | 1.18×10-9 | [108] |

| AZ91D | MgO, Mg3(PO 4)2 MgAl2O4 | -0.148 | 6.4×10-8 | LSP | -1.47 | 5.00×10-9 | [109] |

| AZ91 |

LSP |

-1.39 | 4.22×10-7 | [110] | |||

| Mg alloy | LSM | -1.49 | 8.24×10-7 | [111] | |||

| Mg alloy | LSM | -1.51 | 8.91×10-7 | [111] | |||

| Substrate | MAO Film Composition |

MAO coatings | Pre-processing Method |

MAO coatings with Post-processing | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ecorr (V) |

Icorr (A/cm2) |

Ecorr (V) |

Icorr (A/cm2) |

||||

| Mg | Mg, MgO, Mg2SiO4 | 1.349 | 7.72 × 10− 7 | Impregnation | -1.29 | 5.87×10-8 | [124] |

| AZ31 | Mg3(PO4)2, MgO Mg | Impregnation | -0.69 | 6.72×10-6 | [150] | ||

| AZ31 | Mg, MgO | 2.47 ×10-6 | Impregnation | 9.28×10-8 | [151] | ||

| AZ91D | Mg, Mg2SiO4, MgO | -1.32 | 5.72×10-7 | Impregnation | -1.31 | 3.34×10-8 | [126] |

| LPSO Mg-Y-Zn | Mg MgO | -1.61 | 7.1×10-8 | Impregnation | -1.2 | 2×10-9 | [127] |

| cp-Mg | Mg MgO Mg2SiO4 | -1.59 | 1.4×10-5 | Impregnation | -1.61 | 3.7×10-6 | [130] |

| AZ31 | -1.38 | 1.259×10-6 | Impregnation | -1.36 | 1.34×10-7 | [131] | |

| AZ31B | -1.44 | 3.9×10-7 | Impregnation | -1.32 | 1.81×10-8 | [135] | |

| MA8 | -1.51 | 8.1×10-7 | Impregnation | -1.44 | 8.6×10-8 | [136] | |

| AZ31 | -0.66 | 2.33×10-6 | Impregnation | -0.59 | 8.95×10-10 | [136] | |

| AZ31B | MgO, Mg3(PO4)2, Mg(OH)2, Al12Mg17, Mg |

-1.60 | 3.53×10-8 | HT | -1.35 | 1.27×10-8 | [152] |

| AZ31 | Mg3(PO4)2 Mg MgO | HT | 2.98×10-10 | [144] | |||

| AZ31 | MgAl2O4 Mg | -1.29 | 7.62×10-8 | HT | -1.33 | 1.97×10-9 | [145] |

| AZ31 | Mg MgO | -1.33 | 1.54×10-6 |

Sol- gel |

-1.09 | 1.05×10-7 | [140] |

| Mg3(PO4)2 Mg MgO | -1.75 | 6.17×10-6 | EPD | -1.42 | 4×10-8 | [59] | |

| AZ91 | Mg MgO Mg3(PO4)2 | -1.54 | 9.86×10-6 | EPD | -0.87 | 1.75×10−7 | [142] |

| Mg-Li | -1.38 | 5.64×10-7 | Sol- gel | -1.38 | 5.64×10-7 | [153] | |

| AM50B | Periclase (MgO) Snipel MgAl2O4 Mg |

Sol- gel | -1.39 | 6.57×10-9 | [154] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).