1. The Complement System

The complement system, an integral component of innate immunity, comprises a cascade of proteins that orchestrate immune responses against pathogens while maintaining self-tolerance. However, dysregulation of complement activation can precipitate tissue damage and inflammation, contributing to the pathogenesis of various renal disorders [

1].

In the last decade, emerging finding have revealed the role of complement system in a wide range of kidney disorders [

2] such as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (including C3 glomerulopathy and lupus nephritis), IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy and ANCA-associated vasculitis, showing the role of complement dis-regulation in disease pathophysiology.

Recent advancements in our understanding of complement biology have unveiled intricate regulatory mechanisms and complex crosstalk with other immune and inflammatory pathways both systemic and renal. Notably, the complement cascade crosses with pathways involving immune-complexes, autoantibodies, and cytokines, amplifying renal injury and perpetuating chronic damage until end stage kidney disease (ESKD). Furthermore, genetic predispositions and environmental triggers can predispose individuals to dysregulated complement activation, exacerbating renal injury and influencing disease phenotypes. Insights gleaned from genetic studies and molecular profiling have identified key complement components and regulators as potential biomarkers for disease activity, progression, and therapeutic response in nephropathy.

2. The Complement Cascade

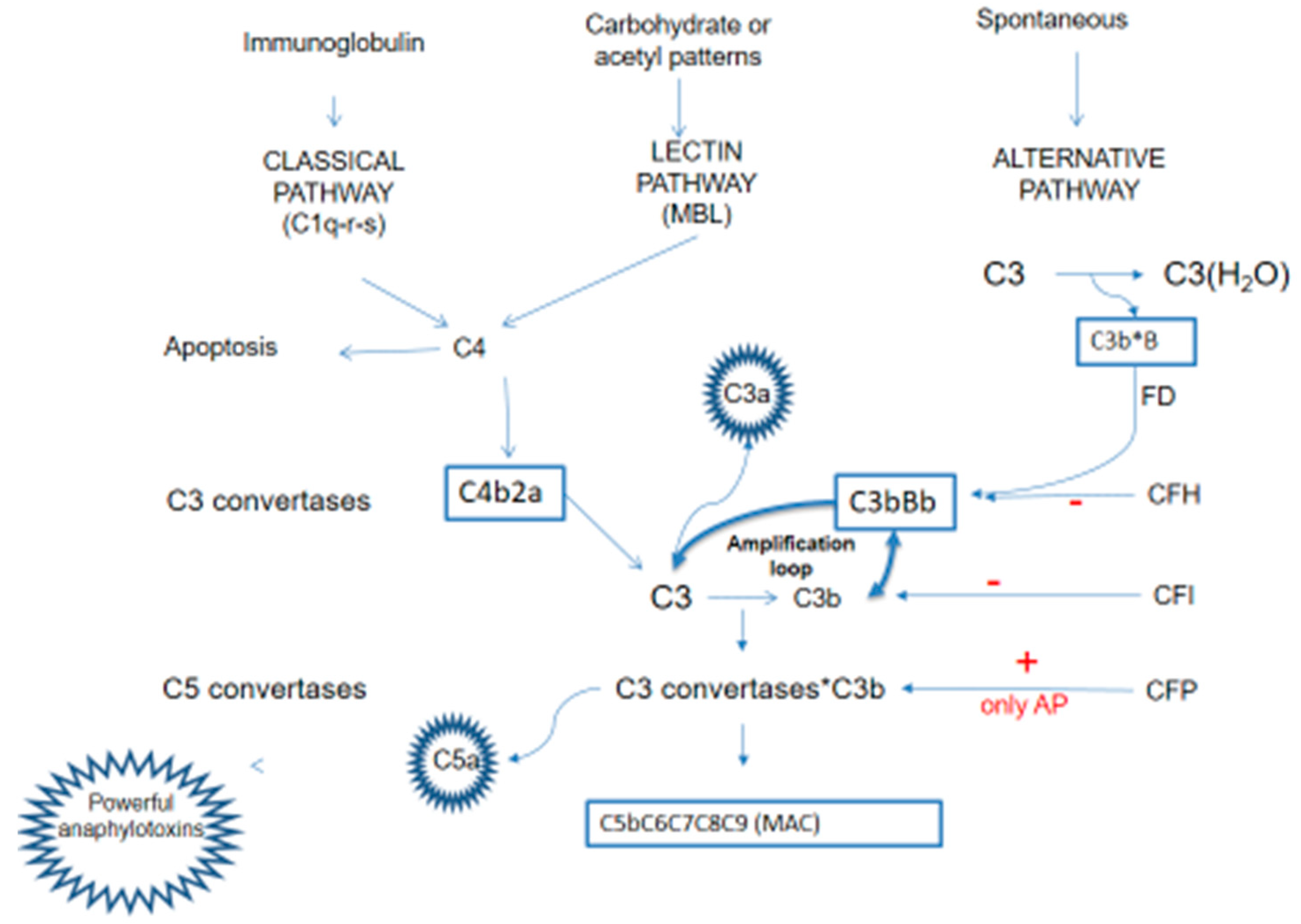

Comprising a cascade of soluble and membrane-bound proteins, the complement system operates through three distinct activation pathways—classical, lectin, and alternative—converging at the generation of effector molecules that mediate immune effector functions, inflammation and immune surveillance. Beyond its canonical role in opsonization, phagocytosis and cell lysis, the complement system interfaces with several immune and non-immune pathways, exerting pleiotropic effects on coagulation pathway, host defense, tissue development and homeostasis.

Each pathway occurs in response to unique molecular signal, but all converge to catalyze the proteolytic cleavage of C3, through the C3 convertase, into two fragments: C3a and C3b. This cleavage is critical to the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) resulting in opsonization, inflammation and cells lysis.

The classical pathway (CP) is triggered by the binding between antigen and antibody to form an immune complex: the Fc fragment of IgG or IgM binds C1q with proteinases C1r and C1s forming the complex C1q-r-s.

The lectin pathway (LP), instead, is activated by mannose-binding lectins (MBL) that recognized pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) and altered self-antigens.

The activation of these two pathways converts on the formation of classical C3 convertase (C4b2a convertase) [

3] that consists of two fragments: C4b and C2a. This complex cleaves C3 into C3a and C3b upon binding to C3. C3b plays a role in the formation of alternative C3 convertase (C3b-Bb convertase) and C5 convertase (C3 convertases-C3b).

The alternative pathway (AP), instead, is spontaneously activated: the alternative C3 convertase (C3b-Bb convertase) is generated spontaneously through low-level hydrolysis of C3 and it consists of two fragments: C3b and factor Bb. This complex is stabilized by properdin (factor P) and constantly triggered to cleaves additional C3 molecules, amplifying the complement cascade, but controlled by several factors - the most important factor B, factor I, factor H - that avoid its uncontrolled activation.

Apart its role in the initial activation steps, C3b has three additional important functions:

- -

it binds to cell surfaces in complex with factor B, triggering a positive feedback loop (called “amplification loop”) with the generation of even more C3a and C3b, leading to rapid amplification of the AP [

4];

- -

it promotes the formation of the C5Conv leading to the formation of the MAC and C5a;

- -

it operates as an opsonin, coating foreign particles and facilitating the recognition and phagocytosis of pathogens by immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils.

Thus the C3 convertases system serves as a central hub and C3b is the leading complement fragment that facilitates the complement cascade, initiating the amplification loop of complement activation.

C3a and C5a acts as a potent anaphylatoxins through the recruitment of leukocytes at the site of inflammation, also promoting the synthesis and release of granules consisting of enzymes and oxidizing agents [

5].

In summary, complement antagonizes pathogens through the formation of mediators that increase the ability of phagocytosis through C3b-mediated opsonization, promoting inflammation through C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins, and causing lysis of pathogens through the formation of the MAC complex [

5].

Exist a delicate balance between activation and inhibition of complement system, ensuring targeted immune responses but averting self-damage and excessive inflammation (

Figure 1).

3. Regulator Proteins

Such a violent inflammatory activation system requires very fine-tuned regulation, for which there are numerous, incompletely understood, regulatory proteins, many of which acting on the C3 convertases hub.

Below the most important regulator proteins that work at various stage of the cascade through several mechanisms.

Factor H (CFH): CFH is the principal negative regulator of the AP; it is a circulating plasma protein and exerts multifaceted control over complement activation by accelerating the decay of alternative pathway C3bBb convertase, promoting the dissociation of C3b from host surface, and serving as a cofactor for CFI. CFH is able to discriminate between healthy host cells and altered host cells or pathogens through binding its C-terminal domains to specific glycan [

6]. Moreover by blocking further activation and amplification of the AP, CFH also downregulates the activity of LP and CP.

Factor H related proteins (FHR): FHR exhibit structural similarity to CFH, comprising multiple complement control protein (CCP) domains and a C-terminal domain. Like CFH, FHR proteins contain binding sites for complement components (such as C3b) and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), enabling them to interact with complement proteins and regulate complement activation. They exhibit distinct functional properties and regulatory activities within the complement system. It has been shown that some FHR, such as FHR-1, FHR-2 and FHR-5 compete with CFH for binding to C3b and to other complement components. This competitive binding may influence the balance of complement activation and inhibition.

Factor I (CFI): CFI acts as a key regulator of the alternative pathway by cleaving and inactivating C3b into its inactive form (iC3b), preventing the assembly and stabilization of the alternative pathway C3 convertase, thereby inhibiting further amplification of the complement cascade.

Properdin (CFP): CFP stabilizes the alternative pathway C3bBb convertase, but not the classical/lectin pathway C4b2a convertase [

7,

8]. In contrast to its proinflammatory role as a stabilizer of C3bBb convertase, CFP also exhibits regulatory functions by facilitating the decay of C3 convertases and promoting the clearance of complement-opsonized immune complexes.

Complement Receptor 1 (CR1): expressed on erythrocytes and immune cells, CR1 regulates complement activation acting as a cofactor for CFI-mediated cleavage of C3b and accelerating the decay of C3 convertase. Moreover, CR1 helps the clearance of complement-opsonized particles and immune complexes, modulating the intensity and lifetime of complement-mediated immune responses.

Membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD46): CD46 disrupts C3 convertase assembly by facilitating CFI-mediated C3b inactivation.

Decay-accelerating factor (DAF,CD55): CD55 prevents complement activation on self-cells by promoting C3 and C5 convertase decay [

9].

Protectin (CD59): CD59 binds C9 with consequently prevention of MAC formation [

3].

Regulatory T Cells (Tregs): beyond soluble inhibitors and membrane-bound regulators, regulatory T cells exert immunomodulatory effects on complement activation and inflammation through cell-cell interaction and cytokine secretion. Tregs suppress excessive complement activation and mitigate tissue injury by promoting immune tolerance and dampening inflammatory response, thereby maintaining immune homeostasis.

Dysregulation of complement regulation can precipitate autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders and tissue damage, underscoring the importance of tight control over complement dynamics. The understanding acquired in recent years about the role of complement in several disease has led to the development of new molecules directed against different complement components (

Table 1).

4. The Role of Complement in Kidney Disease

4.1. Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome

Thrombotic microangiopathy characterizes diseases with severe vascular endothelium damage mediated by different pathogenetic pathways, following by pro-inflammatory and pro-coagulant changes in the endothelium lead to intravascular thrombi, ischemia and organ disfunction [

10]. The microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocitopenia, elevated LDH, undetectable serum haptoglobin, the presence of schistocytes in peripheral blood smears, are easily detectable in blood tests [

11]. Not all patients with TMA have hematologic abnormalities, sometimes TMA can be detected on histologic lesions, in particular in kidney biopsies where the most characteristic acute TMA’s lesions are thrombi occluding vessels with endothelial swelling [

12]. TMA can lead to death or organ disfunction. It is essential to perform a differential diagnosis to identify the type of TMA.

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) represents the systemic expression of TMA, in particular primary atypical hemolytic syndrome (aHUS) is an exclusion diagnosis after ruling out Shiga toxin-producing E. Coli-associated HUS, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and secondary etiologies [

13]. About 60% of aHUS are mediated by pathogenic variants or antibodies against complement components [

14], in particular C3, CD46, CFB, CFH, CFHR5, CFI, THBD and anti-FH antibodies [

15].

In general, it is estimated that 50 percent of cases progress to ESKD with mortality rates around 25 percent; these figures also vary depending on extra-renal involvement and the latency between the onset of symptoms and signs and the beginning of therapy. Treatment with eculizumab, compared to plasmapheresis, has radically changed the prognosis of these patients: prospective studies [

16,

17], confirmed by retrospective and clinical cases [

18], have been showed a rapid improve of hematological impairments and progressive recovery of kidney function in most patients.

Eculizumab is the first marketed drug targeting a specific complement molecule. It is a humanized IgG2-IgG4 hybrid monoclonal antibody (Soliris, Alexion Pharmaceuticals) which binds the C5 complement protein with high affinity and blocks the generation of the pro-inflammatory molecules C5a and C5-b9 [

16]. Eculizumab was first approved for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and only later for use in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). The rationale for its introduction in aHUS lies in the fact that the disease is secondary to an altered regulation of the complement pathway and is proven to occur in at least 50% of cases. The two prospective phase 2 studies that led to its approval demonstrated the efficacy and safety of eculizumab in both plasmapheresis non-responsive and plasmapheresis-dependent patients. Moreover, there was a significant recovery of renal function with suspension of dialysis in 80% of cases. Another study also showed that eculizumab was effective in preventing post renal transplantation aHUS recurrence [

19], thus making it possible to transplant aHUS patients, who otherwise were considered to be at too high risk of disease recurrence. These results determined the FDA and EMA approve of its use despite the study being a Phase II, non-randomized trial. In clinical practice, eculizumab demonstrated ability to radically change the prognosis of aHUS patients.

Eculizumab is administered via intravenous infusion. The initial dose is 900 mg every week followed by maintenance doses of 1200 mg given every 2 weeks. The interruption of the therapy must be carefully evaluated, considering genetic predisposition, severity of the disease and clinical course.

Blocking the terminal part of complement is also thought to be effective in promoting recovery of renal function in all secondary forms of TMA. Unfortunately, no studies have been designed to validate this valuation from the use of the drug in the real-life setting. In particular, evidence has accumulated in TMA secondary to lupus nephritis, renal scleroderma crisis, ANCA vasculitis, IgA nephropathy, malignant hypertension and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome [

20,

21].

Secondary forms of TMA may initially present as kidney-limited forms, making their classification as TMA more difficult and delaying the initiation of specific therapy [

22]. Consensus conferences should be undertaken to establish guidelines to provide a shared approach for these particular conditions. It should also be emphasized that in the course of TMA secondary to lupus nephritis (LN) and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome there is sufficient agreement for the use of eculizumab to rapidly extinguish the TMA and pending treatment of the cause of the secondary TMA, particularly in plasmapheresis resistant TMA [

23].

In recent years, it has been developed Ravulizumab, the first and only long-acting C5 complement inhibitor capable of providing an 8-week durazion of action, compared to every two weeks with eculizumab. Clinical trials documented ravulizumab's non-inferiority to eculizumab in treating PNH and aHUS. This drug, having a longer half-life, allows an improvement in quality of life by limiting the frequency of e.v infusions.

The phase 3 studies evaluated efficacy and safety of ravulizumab (NCT03131219, NCT02949128) in complement inhibitor-naïve adults and adolescent who fulfilled diagnostic criteria for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Ravulizumab treatment resulted in an immediate, complete, and sustained C5 inhibition in all patients. Normalization of platelet count, serum lactate dehydrogenase, and hemoglobin observed in the 26-week initial evaluation period [

24] was sustained until the last available follow-up, as were the improvements in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and patient quality of life [

25].

The anti-C5 monoclonal antibodies therapy altered the immune response encapsulated bacteria, particularly to Neisseria infections [

26]. Thus, disseminated gonococcal infection has been reported in patients treated with eculizumab, and the risk of meningococcal infection has increased up to 10,000-fold following eculizumab treatment. Consequently meningococcal vaccination and antibiotic prophylaxis are recommended for patients receiving eculizumab/ravulizumab[

26]. However susceptibility to meningococcal infection rate decreased over time [

27]; related mortality remained steady. Continued awareness and implementation of risk mitigation protocols are essential to minimize risk of meningococcal and other Neisseria infections in patients receiving anti-C5 monoclonal antibodies.

Studies to evaluate the efficacy of iptacopan (an oral complement Factor B inhibitor, NCT04889430, NCT05795140, NCT05935215), crovalimab and nomacopan (a new C5 inhibitors, NCT04861259, NCT04958265, NCT04784455) are ongoing). A phase 2 study is ongoing to evaluate Pegcetacoplan (C3 inhibitor, NCT05148299) in transplant-associated-TMA after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

4.2. Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) stands as a formidable entity among the spectrum of glomerular diseases, characterized by distinctive histopathological features and different clinical manifestations. Histologically, MPGN manifests as mesangial proliferation, capillary wall thickening and double contour formation, reflecting the underlying immune-mediated injury to the glomerular basement membrane. Clinical presentation of MPGN spans a spectrum ranging from asymptomatic proteinuria and hematuria to progressive kidney insufficiency and nephrotic syndrome, posing diagnostic challenges and required a comprehensive evaluation to elucidate underlying etiologies and guide therapeutic interventions. While kidney biopsy remains the cornerstone of diagnosis, serological and genetic studies play a complementary role in outlining the underlying pathogenic mechanisms and prognosticating disease outcomes.

MPGN has recently been reclassified on an etiopathogenetic basis, revolutionizing the previous approach that described histopathological aspects that often overlapped and did not allow for an appropriate subdivision with respect to the cause of the renal picture [

28]. This new classification stands out MPGN into two main groups: complement-mediated (named C3 glomerulopathy) and immune complex-mediated (IC-MPGN).

According to this classification, C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) is characterized by immunofluorescence recognition of isolated glomerular C3 deposits and includes C3 glomerulonephritis and dense deposit disease. Acquired factors are involved in most patients, namely autoantibodies that target the C3 or C5 convertases. These autoantibodies drive complement dysregulation by increasing the half-life of these vital but normally short-lived enzymes. Genetic variation in complement-related genes were identified in about 25% of patients, in particular of C3, CFB, but also CFH, CFI, DGKE and CFHR genes.

When immunofluorescence shows complement and immunoglobulin deposition the disease is considered to be IC-MPGN. Rarely an histological MPGN pattern is documented in the absence of deposits on immunofluorescence staining, which should lead to suspicion of a chronic TMA.

Therapeutically, the management of MPGN remains challenging, with no consensus guidelines and limited evidence-based interventions to guide clinical practice. Immunosuppressive regimens, including corticosteroids, cytotoxic agents and rituximab, have been employed empirically in selected cases, aiming to modulate immune-mediated inflammation and halt disease progression. However, the variable response to immunosuppressive therapies underscores the need for tailored approaches informed by disease phenotype, complement profile, and genetic predisposition [

29].

Regarding C3G, the efficacy of eculizumab was evaluated in a small clinical trial involving six patients: two patients showed improvement of proteinuria, one complete remission and one patient stabilized kidney function [

30]. On the basis of this results, eculizumab in C3G was no more implemented.

Recently new complement targeted treatments were attempted in C3G. The phase 3 APPEAR-G3G study (NCT04817618) evaluated the efficacy of iptacopan in patients with C3G. This study has showed a normalization of plasma C3, a reduction of proteinuria and an improvement of eGFR [

31].

The randomized study ACCOLADE (NCT03301467) evaluated the use of avacopan (C5 receptor inhibitor), showing a reduction of histologic disease chronicity compared to placebo but failed to achieve the reduction in disease activity [

32,

33]. The two phase 3 studies VALIANT (NCT05067127) and VALE (NCT05809531) are evaluating the use of pegcetacoplan. Preliminary results have showed a reduction in proteinuria and stabilization of kidney function. The phase Ib study NCT05647811 will evaluate the safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of NM8074 (Factor Bb inhibitor) administered intravenously to patients with C3 glomerulopathy, while the phase 2 study NCT06209736 will evaluate Zaltenibart (MASP3 inhibitor).

4.3. Secondary IC-MPGN (Lupus NEPHRITIS)

Regarding the immune-complex mediated glomerulonephritis, complement plays a pivotal role in lupus nephritis (LN). Indeed, complement have a biphasic nature, knows ad the “lupus paradox”: complement activation due to the deposition of immune-complexes causes tissue damage, whereas genetic deficiencies of the early components of complement activation pathway (C1q and C4) can lead to the development of the disease. All the three pathways are involved in LES, so complement serum levels (C3, C4, CH50, C1q) and complement deposition on histological tissues are used for the management of SLE [

34]. Rossi et al, showed that low C3 serum is associated with high risk of ESKD [

35].

It must be emphasized that in approximately 5-15% of cases, TMA can be present in kidney biopsies of patients with LN, with worst outcome. To date, there are no clinical trials on the use of eculizumab in LN however, it is now established practice to introduce eculizumab considering complement-mediated microangiopathic damage prevalent over proliferative inflammatory damage secondary to immune complex deposition [

36].

Randomized trials are ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of pegcetacoplan, iptacopan, ravulizumab [

37]. Moreover, a phase 1b trial to assess the safety, tolerability and pharmacodynamics of ANX009 (C1q inhibitor) is underway.

4.4. IgA Nephropathy

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide. It was first described by Jean Berger in 1969 [

38]and has an annual incidence of 2-10 cases per 100 000 people. The classical phenotype includes hematuria intercurrent with gastrointestinal or upper respiratory tract infection, in particular gross hematuria is more typical in children while asymptomatic hematuria with various degrees of proteinuria is the most common presentation in adults. The progression of the disease is usually slow, but up to 20-40% of patients develop end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) within 20 years after diagnosis [

39].

The pathogenesis is based on the “four-hit-hypothesis” characterized by the increased circulating levels of an aberrantly glycosylated galactose-deficient IgA (gd-IgA1), followed by the formation of immune complexes with an anti-gd-IgA1 antibodies with the deposition in the glomerular mesangium, leading to kidney injury. However, the presence of gd-IgA1 is by itself non-sufficient to cause IgAN [

40]. Several studies had showed the involvement of AP and LP in IgAN [

41] and the presence of complement components in kidney biopsies may distinguish between IgAN and IgA deposition that can be found in healthy subjects. C3, CFH, properdin and CFH-related proteins are found in renal biopsies [

41]. In particular, glomerular C3 deposition [

42] and reduction of serum level of C3 [

43] seems to correlate with the progression of the disease [

44].

The finding of C4d in the absence of C1q in kidney biopsies suggests that the LP is also involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. Gd-IgA1 may trigger LP activation through the interaction with ficolin [

41]: increased circulating levels of ficolin, MBL-associated protease (MASP-1) and MBL-associated protein (Map-19) were found in IgAN compared healthy control [

45].

The evidence of the involvement of complement in IgAN has resulted in the beginning of several clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of direct molecules against complement components [

46].

Recently, iptacopan showed superiority in reducing proteinuria by 38% at 9 months follow up over placebo in an interim analysis of a study involving more than 200 patients [

47]. Data about the permanence of the effect on proteinuria reduction and renal function are expected with the conclusion of the study. Lafayette et al. [

48] showed an improvement in proteinuria and stability of eGFR in high-risk patients with advanced IgAN treated with narsoplimab (OMS7, MASP2 inhibitor). However, the interim analysis of the ARTEMISAN-IGAN study failed to show any results on proteinuria reduction and the study has been recently stopped [

49] (Omeros (2023). Press release: Omeros Corporation provides update on interim analysis of ARTEMIS-IGAN Phase 3 trial of narsoplimab in IgA nephropathy).

Recently, a small phase 2 study testing cemdisiran (a new anti-C5) in nine patients over placebo in IgA nephropathy showed more than 30% reduction in proteinuria 32 weeks after treatment [

50]. A phase 2 studies for the use of pegcetacoplan (NCT03453619) and IONIS- FB- LRX (Factor B inhibitor, NCT04014335) in patients with IgAN are actually ongoing, while the NM8074-IgAN-601 (NCT06454110) will study the effect of NM8074 to reducing proteinuria in IgAN patients.

The activation of AP and LP converge to the terminal pathway. C5aR knockout mice had less proteinuria, C3 and IgA deposition in the glomeruli. In humans, MAC glomerular deposition has a positive correlation with the degree of glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy and interstitial inflammation in IgAN [

46]. However, the use of eculizumab has not shown efficacy in patients with IgAN [

51]. Differently a pilot phase II study (NCT02384317), showed the positive effect of avacopan with improvement of proteinuria after 12 weeks of treatment [

52].

4.5. ANCA-Associated Vasculitis

ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) represents a group of systemic autoimmune diseases characterized by necrotizing inflammation of small to medium-size blood vessels without immune complex deposition, and by the presence in the serum of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), especially anti-proteinase 3 (PR3) and anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO). AAV include microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) and renal-limited vasculitis [

53]. Vasculitis are characterized by a heterogeneous clinical presentation with not specific constitutional symptoms (fatigue, fevers, weight loss). Virtually all organs can be involved. The involvement of the upper respiratory tract is more common in GPA than MPA; the lung involvement is characterized by alveolar hemorrhage in MPA whereas pulmonary necrotizing granulomatous lesions are more common in GPA [

54]. The kidney involvement is common and can lead to end stage kidney disease if not early recognized. The introduction of immunosuppressive therapy has improved survival: 90% of patients achieve remission [

55], but roughly 50% of patients relapse [

56].

The absence or the paucity of immunoglobulins and complement deposition in kidney biopsies suggested, in the past years, the lack of involvement of the complement cascade in the pathogenesis of AAV [

57]. Only in 2007, Xiao et al [

58] investigated the possible role of complement in AAV and they showed the importance of complement activity, especially of the AP. Neutrophils activated by ANCAs release properdin that activates the alternative pathway with the generation of C5a. C5a binding to the specific receptor (CD88) on the neutrophils surface generates an amplification loop of the inflammatory process until the development of characteristic necrotizing lesions. C5a contributes also to the formation of MAC complex with cell lysis and further endothelial damage [

59]. It was observed an association between hypocomplementemia (serum C3) and more severe kidney involvement and worst outcome, suggesting an active role of AP in kidney damage [

60].

The association between AAV and TMA was considered rare until a few years ago [

61]. Chen et al found a prevalence of TMA of 13,6% in patients with vasculitis, with a higher risk of worse renal outcome [

62]. An abnormal activation of the AP can occur in AAV with positive inflammatory feedback loop between ANCAs, neutrophils and complement [

63]. It results in endothelia damage, especially due to C5a, and microangiopathic lesions. In addition, it has been showed a strong association between low serum C3 and histologic signs of TMA with a worse kidney prognosis [

64]. Despite eculizumab has not been tested in AAV but only used in sporadic clinical cases with good efficacy [

65,

66], the importance of the role of complement was showed in recent years by the efficacy of a new complement-targeted oral drug, a C5a receptor inhibitor, avacopan (CCX168). The therapeutic effects of avacopan are attributed to the inhibition of C5aR activity on neutrophils. The efficacy was showed not only in vitro [

67] but also in vivo: it has been demonstrated in a phase II trial an improved kidney function, decreasing the need of glucocorticoids and maintaining a sustained remission after 52-week respect steroid [

68,

69]. Moreover, the latest phase III clinical trial, ADVOCATE study, compared AAV patients treated with standard of care (rituximab or cyclophosphamide) plus avacopan (suspension of steroids immediately) versus standard of care (with a 26 weeks tapering schedule of prednisone) in patients with AAV treated with concomitant immunosuppressive regimens.

The study enrolled more than 300 patients and showed non inferiority of avacopan compared to steroid at week 26 and 52 (p value < 0.001) in obtaining vasculitis remission, whereas superiority at week 52 (p value 0.007) was documented in maintaining sustained remission. Less adverse events were observed in avacopan group compared the steroid group [

70]. This relevant study led to the approval by the US and European drug regulatory agencies of avacopan in the treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Furthermore, it was shown that patients treated with avacopan had a greater recovery of renal function than those treated with the steroid. One of the limitations of the study was that patients with end stage kidney disease (eGFR <15ml/min) were not enrolled, and this may limit its use in case of severe AAV and progressive kidney involvement. However, recently a post-hoc analysis of the ADVOCATE study showed that the benefit of avacopan in kidney functional recovery appears to be even greater in cases with more aggressive renal involvement.

A phase II trial with Vilobelimab, a monoclonal antibody targeting C5a, was reported by the manufacturer as terminated in 2021 with positive results (NCT03895801, NCT03712345). However the study wasn’t published yet and there is no information about the start of an ongoing phase III study.

4.6. Membranous Nephropathy

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults characterized by thickening of the glomerular basement membrane due to immune- complex deposition resulting in structural and functional damage of podocytes.

One third of patients go into spontaneous remission, while 40% of patients develop ESKD within 10 years after diagnosis. 80% of MN are idiopathic, characterized by the presence of autoantibodies against podocyte antigens PLA2R ( phospholipase A2 receptor 1) and THSD7A ( thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing protein 7A).

The remaining 20% recognize secondary causes, in particularly infections, tumors, and other autoimmune diseases [

71].

Experimental data from the Heymann nephritis rat model of human MN have shown that IgG antibodies in subepithelial immune deposits start complement activation and C5b-9-mediated damage of the podocyte. Although IgG can activate the classical pathway, there are also evidence that alternative pathway activation occurs in MN, which could occur because of absent, dysfunctional, or inhibited podocyte complement regulatory protein [

72].

Increased plasma level of C3a and C3aR expression and deposition of C5b-9 in glomeruli have been found in MN patients [

73].

The use of eculizumab versus placebo was attempted in a multicenter, double-blind study that found no difference in proteinuria after 16 weeks. More encouraging was the reduction in proteinuria with open-label use of eculizumab for up to 1 yr in some patients [

72].

Considering the role of complement, iptacopan versus rituximab has been evaluated. The study (NCT04154787) was early terminated because it could be predicted that the primary goal of superiority of ipatcopan vs rituximab in the reduction of proteinuria at 24 weeks was not possible to achieve. At the moment, nevertheless the evidence of complement involvement of pathogenesis of MN, more studies are necessary to understand if anti-complement therapy may play a key role in the treatment of MN in the future.

5. Conclusions

The role of drugs aimed at controlling complement activation in several parts of the complement cascade is already central in several kidney diseases. The pioneer drug was eculizumab, which made it possible to drastically change the prognosis of an otherwise fatal disease such as aHUS. To date, three drugs to treat kidney disease are already commercially available (eculizumab, ravulizumab and avacopan), but several others are on the verge of commercialization (iptacopan, cemdisaran, danicopan, pegtecatoplan). Moreover, a large number of studies aimed to improving the renal prognosis of primary or secondary glomerulonephritis, kidney transplantation and AKI are still ongoing. The nephrologist must learn to take a curious and enthusiastic look at these new therapeutic perspectives that are revolutionizing nephrology.

References

- Mathern DR, Heeger PS. Molecules Great and Small: The Complement System. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;10(9):1636-1650. [CrossRef]

- Lasorsa F, Rutigliano M, Milella M, et al. Complement System and the Kidney: Its Role in Renal Diseases, Kidney Transplantation and Renal Cell Carcinoma. IJMS. 2023;24(22):16515. [CrossRef]

- Anwar IJ, DeLaura I, Ladowski J, Gao Q, Knechtle SJ, Kwun J. Complement-targeted therapies in kidney transplantation—insights from preclinical studies. Front Immunol. 2022;13:984090. [CrossRef]

- Lachmann PJ. The Amplification Loop of the Complement Pathways. In: Advances in Immunology. Vol 104. Elsevier; 2009:115-149. [CrossRef]

- Guo RF, Ward PA. ROLE OF C5A IN INFLAMMATORY RESPONSES. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23(1):821-852. [CrossRef]

- Pangburn MK. Cutting Edge: Localization of the Host Recognition Functions of Complement Factor H at the Carboxyl-Terminal: Implications for Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. The Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(9):4702-4706. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bos RM, Pearce NM, Granneman J, Brondijk THC, Gros P. Insights Into Enhanced Complement Activation by Structures of Properdin and Its Complex With the C-Terminal Domain of C3b. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2097. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen DV, Gadeberg TAF, Thomas C, et al. Structural Basis for Properdin Oligomerization and Convertase Stimulation in the Human Complement System. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2007. [CrossRef]

- Angeletti A, Cantarelli C, Petrosyan A, et al. Loss of decay-accelerating factor triggers podocyte injury and glomerulosclerosis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2020;217(9):e20191699. [CrossRef]

- Genest DS, Patriquin CJ, Licht C, John R, Reich HN. Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy: A Review. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2023;81(5):591-605. [CrossRef]

- George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of Thrombotic Microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):654-666. [CrossRef]

- Brocklebank V, Wood KM, Kavanagh D. Thrombotic Microangiopathy and the Kidney. CJASN. 2018;13(2):300-317. [CrossRef]

- Goodship THJ, Cook HT, Fakhouri F, et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy: conclusions from a “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney International. 2017;91(3):539-551. [CrossRef]

- Noris M, Bresin E, Mele C, Remuzzi G. Genetic Atypical Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. Accessed November 18, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1367/.

- Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Fakhouri F, Roumenina L, Dragon–Durey MA, Loirat C. Syndrome hémolytique et urémique lié à des anomalies du complément. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 2011;32(4):232-240. [CrossRef]

- Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al. Terminal Complement Inhibitor Eculizumab in Atypical Hemolytic–Uremic Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2169-2181. [CrossRef]

- Licht C, Greenbaum LA, Muus P, et al. Efficacy and safety of eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome from 2-year extensions of phase 2 studies. Kidney International. 2015;87(5):1061-1073. [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri F, Delmas Y, Provot F, et al. Insights From the Use in Clinical Practice of Eculizumab in Adult Patients With Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Affecting the Native Kidneys: An Analysis of 19 Cases. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2014;63(1):40-48. [CrossRef]

- Zuber J, Le Quintrec M, Krid S, et al. Eculizumab for Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Recurrence in Renal Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2012;12(12):3337-3354. [CrossRef]

- Cordero L, Cavero T, Gutiérrez E, et al. Rational use of eculizumab in secondary atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Front Immunol. 2024;14:1310469. [CrossRef]

- Manenti L, Gnappi E, Vaglio A, et al. Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome with underlying glomerulopathies. A case series and a review of the literature. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2013;28(9):2246-2259. [CrossRef]

- Genest DS, Patriquin CJ, Licht C, John R, Reich HN. Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy: A Review. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2023;81(5):591-605. [CrossRef]

- Park MH, Caselman N, Ulmer S, Weitz IC. Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy associated with lupus nephritis. Blood Advances. 2018;2(16):2090-2094. [CrossRef]

- Rondeau E, Scully M, Ariceta G, et al. The long-acting C5 inhibitor, Ravulizumab, is effective and safe in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome naïve to complement inhibitor treatment. Kidney International. 2020;97(6):1287-1296. [CrossRef]

- Barbour T, Scully M, Ariceta G, et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of the Long-Acting Complement C5 Inhibitor Ravulizumab for the Treatment of Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome in Adults. Kidney International Reports. 2021;6(6):1603-1613. [CrossRef]

- Benamu E, Montoya JG. Infections associated with the use of eculizumab: recommendations for prevention and prophylaxis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2016;29(4):319-329. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Liu X, Zhang J, Zhang B. Real-world safety profile of eculizumab: an analysis of FDA adverse event reporting system and systematic review of case reports. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. Published online August 26, 2024:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis — A New Look at an Old Entity. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1119-1131. [CrossRef]

- Smith RJH, Appel GB, Blom AM, et al. C3 glomerulopathy — understanding a rare complement-driven renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(3):129-143. [CrossRef]

- Bomback AS, Smith RJ, Barile GR, et al. Eculizumab for Dense Deposit Disease and C3 Glomerulonephritis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012;7(5):748-756. [CrossRef]

- Bomback AS, Kavanagh D, Vivarelli M, et al. Alternative Complement Pathway Inhibition With Iptacopan for the Treatment of C3 Glomerulopathy-Study Design of the APPEAR-C3G Trial. Kidney International Reports. 2022;7(10):2150-2159. [CrossRef]

- Bomback A, Herlitz LC, Yue H, Kedia PP, Schall TJ, Bekker P. POS-112 EFFECT OF AVACOPAN, A SELECTIVE C5A RECEPTOR INHIBITOR, ON COMPLEMENT 3 GLOMERULOPATHY HISTOLOGIC INDEX OF DISEASE CHRONICITY. Kidney International Reports. 2022;7(2):S47-S48. [CrossRef]

- Bomback AS, Herlitz LC, Kedia PP, Petersen J, Yue H, Lafayette RA. Safety and Efficacy of Avacopan in Patients with C3 Glomerulopathy: Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. JASN. Published online October 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ayano M, Horiuchi T. Complement as a Biomarker for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Biomolecules. 2023;13(2):367. [CrossRef]

- Rossi GM, Maggiore U, Peyronel F, et al. Persistent Isolated C3 Hypocomplementemia as a Strong Predictor of End-Stage Kidney Disease in Lupus Nephritis. Kidney International Reports. 2022;7(12):2647-2656. [CrossRef]

- Wright RD, Bannerman F, Beresford MW, Oni L. A systematic review of the role of eculizumab in systemic lupus erythematosus-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):245. [CrossRef]

- Thakare SB, So PN, Rodriguez S, Hassanein M, Lerma E, Wiegley N. Novel Therapeutics for Management of Lupus Nephritis: What Is Next? Kidney Medicine. 2023;5(8):100688. [CrossRef]

- Berger J. IgA glomerular deposits in renal disease. Transplant Proc. 1969;1(4):939-944.

- Rajasekaran A, Julian BA, Rizk DV. IgA Nephropathy: An Interesting Autoimmune Kidney Disease. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2021;361(2):176-194. [CrossRef]

- Pattrapornpisut P, Avila-Casado C, Reich HN. IgA Nephropathy: Core Curriculum 2021. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2021;78(3):429-441. [CrossRef]

- Tortajada A, Gutierrez E, Pickering MC, Praga Terente M, Medjeral-Thomas N. The role of complement in IgA nephropathy. Molecular Immunology. 2019;114:123-132. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki K, Honda K, Tanabe K, Toma H, Nihei H, Yamaguchi Y. Incidence of latent mesangial IgA deposition in renal allograft donors in Japan. Kidney International. 2003;63(6):2286-2294. [CrossRef]

- Medjeral-Thomas NR, Cook HT, Pickering MC. Complement activation in IgA nephropathy. Semin Immunopathol. 2021;43(5):679-690. [CrossRef]

- Rossi GM, Ricco F, Pisani I, et al. C3 Hypocomplementemia Predicts the Progression of CKD towards End-Stage Kidney Disease in IgA Nephropathy, Irrespective of Histological Evidence of Thrombotic Microangiopathy. JCM. 2024;13(9):2594. [CrossRef]

- Medjeral-Thomas NR, Troldborg A, Constantinou N, et al. Progressive IgA Nephropathy Is Associated With Low Circulating Mannan-Binding Lectin–Associated Serine Protease-3 (MASP-3) and Increased Glomerular Factor H–Related Protein-5 (FHR5) Deposition. Kidney International Reports. 2018;3(2):426-438. [CrossRef]

- Gentile M, Sanchez-Russo L, Riella LV, et al. Immune abnormalities in IgA nephropathy. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2023;16(7):1059-1070. [CrossRef]

- Perkovic V, Barratt J, Rovin B, et al. Alternative Complement Pathway Inhibition with Iptacopan in IgA Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. Published online October 25, 2024:NEJMoa2410316. [CrossRef]

- Lafayette RA, Rovin BH, Reich HN, Tumlin JA, Floege J, Barratt J. Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy of Narsoplimab, a Novel MASP-2 Inhibitor for the Treatment of IgA Nephropathy. Kidney International Reports. 2020;5(11):2032-2041. [CrossRef]

- Barratt J, Lafayette RA, Floege J. Therapy of IgA nephropathy: time for a paradigm change. Front Med. 2024;11:1461879. [CrossRef]

- Barratt J, Liew A, Yeo SC, et al. Phase 2 Trial of Cemdisiran in Adult Patients with IgA Nephropathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. CJASN. 2024;19(4):452-462. [CrossRef]

- Ring T, Pedersen BB, Salkus G, Goodship THJ. Use of eculizumab in crescentic IgA nephropathy: proof of principle and conundrum? Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(5):489-491. [CrossRef]

- Bruchfeld A, Magin H, Nachman P, et al. C5a receptor inhibitor avacopan in immunoglobulin A nephropathy—an open-label pilot study. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2022;15(5):922-928. [CrossRef]

- Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2013;65(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Geetha D, Jefferson JA. ANCA-Associated Vasculitis: Core Curriculum 2020. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2020;75(1):124-137. [CrossRef]

- Flossmann O, Berden A, De Groot K, et al. Long-term patient survival in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):488-494. [CrossRef]

- Cornec D, Gall ECL, Fervenza FC, Specks U. ANCA-associated vasculitis — clinical utility of using ANCA specificity to classify patients. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(10):570-579. [CrossRef]

- Mazzariol M, Manenti L, Vaglio A. The complement system in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: pathogenic player and therapeutic target. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2023;35(1):31-36. [CrossRef]

- Xiao H, Schreiber A, Heeringa P, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Alternative Complement Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Disease Mediated by Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibodies. The American Journal of Pathology. 2007;170(1):52-64. [CrossRef]

- Noone D, Hebert D, Licht C. Pathogenesis and treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis—a role for complement. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Manenti L, Vaglio A, Gnappi E, et al. Association of Serum C3 Concentration and Histologic Signs of Thrombotic Microangiopathy with Outcomes among Patients with ANCA-Associated Renal Vasculitis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;10(12):2143-2151. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch DJ, Jindal KK, Trillo AA. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive crescentic glomerulonephritis and thrombotic microangiopathy. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1995;26(2):385-386. [CrossRef]

- Chen SF, Wang H, Huang YM, et al. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Outcomes of Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy in Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody-Associated Glomerulonephritis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;10(5):750-758. [CrossRef]

- Poppelaars F, Thurman JM. Complement-mediated kidney diseases. Molecular Immunology. 2020;128:175-187. [CrossRef]

- Manenti L, Vaglio A, Gnappi E, et al. Association of Serum C3 Concentration and Histologic Signs of Thrombotic Microangiopathy with Outcomes among Patients with ANCA-Associated Renal Vasculitis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;10(12):2143-2151. [CrossRef]

- Manenti L, Urban ML, Maritati F, Galetti M, Vaglio A. Complement blockade in ANCA-associated vasculitis: an index case, current concepts and future perspectives. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(6):727-731. [CrossRef]

- Huizenga N, Zonozi R, Rosenthal J, Laliberte K, Niles JL, Cortazar FB. Treatment of Aggressive Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody–Associated Vasculitis With Eculizumab. Kidney International Reports. 2020;5(4):542-545. [CrossRef]

- Bekker P, Dairaghi D, Seitz L, et al. Characterization of Pharmacologic and Pharmacokinetic Properties of CCX168, a Potent and Selective Orally Administered Complement 5a Receptor Inhibitor, Based on Preclinical Evaluation and Randomized Phase 1 Clinical Study. Eller K, ed. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0164646. [CrossRef]

- Jayne DRW, Bruchfeld AN, Harper L, et al. Randomized Trial of C5a Receptor Inhibitor Avacopan in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. JASN. 2017;28(9):2756-2767. [CrossRef]

- Merkel PA, Niles J, Jimenez R, et al. Adjunctive Treatment With Avacopan, an Oral C5a Receptor Inhibitor, in Patients With Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody–Associated Vasculitis. ACR Open Rheumatology. 2020;2(11):662-671. [CrossRef]

- Jayne DRW, Merkel PA, Schall TJ, Bekker P. Avacopan for the Treatment of ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):599-609. [CrossRef]

- Ronco P, Debiec H. Target antigens and nephritogenic antibodies in membranous nephropathy: of rats and men. Semin Immunopathol. 2007;29(4):445-458. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham PN, Quigg RJ. Contrasting Roles of Complement Activation and Its Regulation in Membranous Nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2005;16(5):1214-1222. [CrossRef]

- Chung EYM, Wang YM, Keung K, et al. Membranous nephropathy: Clearer pathology and mechanisms identify potential strategies for treatment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1036249. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).