1. Introduction

As the Internet of Things (IoT) and wireless communication grow, they change people’s life by progressive technologies, created new opportunities for growth, Improved efficiency and quality of life. IoT has made modern infrastructures more efficient and interconnected. Statista [

1] noted there will be 1.8 billion connected IoT devices by the end of 2023. By 2033, there will be 3.96 billion. This growth shows that more and more people are using IoT to make their lives and work easier. Some devices use Wi-Fi to connect and send data, allowing users to control IoT devices only by one smartphone. However, as IoT devices become more common, cybersecurity becomes a serious issue. Many devices send sensitive data over public networks, making them easy to steal. Insecure data transmission not only compromises personal privacy but also exposes vulnerabilities in essential systems that rely on IoT infrastructure. Strong cryptographic algorithms are needed to use when data transmissions.

Common encryption methods like Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) and RSA are good at keeping data safe. They make it hard for attackers to break encrypted data easily. The cryptographic strength of AES and RSA imposes resource-intensive demands on attackers attempting to break the encryption. However, side-channel attacks (SCA) pose a significant threat by bypassed the mathematical security of these algorithms. SCAs exploit the physical characteristics emitted by encryption devices, such as power consumption [

2], electromagnetic radiation [

3], and thermal emissions [

4]—to infer encryption keys. These physical leakages often exhibit statistical correlations with the keys, allowing attackers to deduce them through sophisticated analysis.

Current SCA defense strategies primarily focus on microcontrollers, utilizing techniques such as masking [

5] and hiding [

6] to minimize the observability of physical signals, thereby improving resistance to SCAs. Yet, as SCA techniques continue to evolve in complexity, traditional defenses have proven insufficient [

7]. Furthermore, the rapid progress in quantum computing introduces additional threats to existing security mechanisms. Consequently, the development of more robust defense strategies has become imperative.

Recently, researchers have proposed a SCA method targeting Wi-Fi environments, which enables attackers to decrypt transmitted data without the need of access to the device's password [

8]. This study highlights the significant threat that SCA poses to modern information security. To address this challenge, the present research introduces a lightweight AES-128-based encryption key protection mechanism specifically designed for securing IoT communications. This mechanism effectively defends against SCAs without compromising system performance. In IoT devices, AES-128 has become the best candidate encryption algorithm due to its low computational overhead and power consumption [

9]. Compared to other encryption methods, AES-128 not only provides sufficient encryption strength [

10], but also operates with high efficiency. However, just relied on the encryption algorithm itself is not enough to ensure robust security. Especially in public network environments, IoT devices performing encryption operations may leak physical signals, which attackers can exploit to compromise encryption keys, thus threatening the overall security of the system. If smart home devices, such as access control or surveillance systems, fall victim to SCAs, personal privacy and sensitive data could be severely compromised [

11]. Therefore, improving encryption key protection mechanisms for IoT devices is both a critical and urgent task. Furthermore, Zeng et al. [

12] have proposed an enhanced Message Authentication Encryption (MAE) scheme based on Physical Layer Key Generation (PKG), which improves encryption efficiency by 80.5% while consuming fewer computational resources. This advancement offers a more efficient security solution for resource-constrained IoT devices.

This paper proposed a dynamic AES key replacement mechanism based on the concept of Moving Target Defense (MTD), coupled with the Diffie-Hellman (D-H) key exchange protocol. This combined approach enables the dynamic replacement of AES encryption keys during transmission, significantly reducing the risk of key compromise. To evaluate the effectiveness of this approach, we constructed an IoT transmission system using an Arduino UNO and the ESP8266 Wi-Fi module [

13]. During testing, attackers used probes to capture the physical traces emitted by the encryption devices and conducted statistical analysis on GPU computing platform. Results showed that after analyzing a sufficient number of traces, the attackers were able to extract the AES encryption key. This finding highlights that static AES keys were insufficient for ensuring the security of IoT devices in public environments. Dynamic key replacement is necessary to mitigate the risk of key leakage.

To address these vulnerabilities, we referred upon a MTD-based defense mechanism by Vuppala et al. [

14] and designed a high-efficiency dynamic key replacement mechanism utilizing the D-H protocol. This mechanism dynamically replaces encryption keys after each transmission, providing enhanced resilience against SCA-based key extraction. Experimental results demonstrate that this approach substantially reduces the risk of data leakage in IoT devices operating in public environments, making it particularly well-suited for lightweight IoT microcontrollers.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

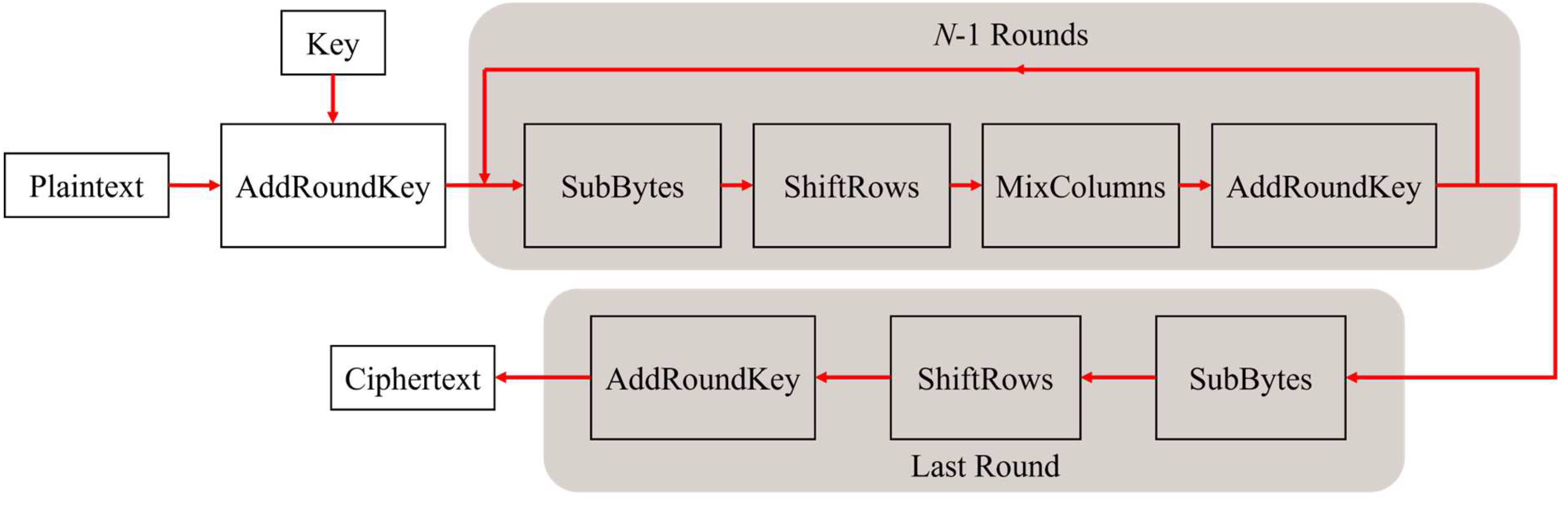

AES was first introduced in 1998[

15,

16] and officially adopted as the standard for symmetric encryption algorithms in 2001, replacing the legacy Data Encryption Standard (DES), which supported only 56-bit keys. Due to its high computational efficiency and strong security features, AES has become one of the most widely used encryption algorithms, particularly within the IoT domain. AES encryption process consists of four main stages. First, the plaintext is arranged into a 4x4 matrix, where each element represents 1 byte., Then the key matrix is XORed with the plaintext matrix during AddRoundKey(). Next, SubBytes() replace each byte using S-Box lookup table to introduce nonlinear transformation to enhance security. Next, the ShiftRows() operation shifts the rows of the state matrix to increase data diffusion. Except the last round, MixColumns() operation is performed, which combines the four bytes in each column to obscure the relationship between plaintext and ciphertext through matrix multiplication in the Galois Field (GF(2^8)).

The main difference between AES-128, AES-192, and AES-256 is the length of encryption key, which impacts the number of encryption rounds N of 10, 12 or 14, offers a flexible balance between security and performance. Given the resource limitations in IoT devices, AES-128 is widely adopted due to its low computational overhead and power consumption while still offering strong security. In AES-128, the 128-bit key is divided into 16 individual bytes, each ranging from hexadecimal 00 to FF. The encryption process as illustrated in

Figure 1, ensures that even with the shortest key length, AES provides high level of security and performance, making it particularly well-suited for lightweight IoT systems.

In 2023, NIST chose ASCON [

17] as the next-generation lightweight cryptographic standard for IoT encryption. ASCON wasn't the fastest, but it was chosen due to its secure, well operate on low-power platforms, and can't be attacked in other ways. ASCON is well-suited for resource-constrained environments. It based on AEAD and SHA-256, providing efficient protection for short-lived, time-sensitive data commonly found in IoT ecosystems by low power overhead. However, ASCON is not necessarily more secure than AES-128 in all cases. ASCON is best for short-lived data in low-power environments. AES-128 is still the best choice for securing persistent and sensitive data in many IoT applications. Most microcontrollers have already used well-known cryptographic algorithms like AES, RSA, ECDSA, and SHA-256. This makes AES-128 a better choice than ASCON. This study improves the AES-128 encryption algorithm for use in real-world IoT applications. Because it is compatible with many devices and provides security, improving AES-128 can benefit IoT devices that need to be secure and perform well. By refining the algorithm, we aimed to provide a solution that ensure robust protection without using too much resources.

2.2. Side-Channel Attacks (SCAs)

SCAs are a non-invasive technique aimed at exploiting the physical characteristics leaked by cryptographic implementations, specifically targeting the hardware behavior of microcontrollers in IoT devices. Since encryption algorithms are ultimately executed on microcontroller chips, attackers can analyze physical signals, such as power consumption or electromagnetic emissions, to infer the encryption keys. Common SCA techniques consist of Simple Power Analysis (SPA)[

18], Differential Power Analysis (DPA), and Correlation Power Analysis (CPA)[

19]. In this study, CPA is employed as the primary attack method because it effectively analyzes the correlation between the power consumption of the encryption device and the encryption key.

During the AES encryption process, attackers typically focus on the output of the S-Box in the first round as the Point of Interest (PoI), since at this stage, the signal has only passed through AddRoundKey() and SubBytes() operations. Attackers record the power consumption or electromagnetic emissions during encryption process, converting these signals into traces, which are binary representations of the recorded data. These traces are then subjected to statistical analysis.

CPA works by correlating hypothetical key guesses with the actual recorded traces, using correlation analysis to infer the correct key. Since there is a relationship between the electromagnetic emissions and power consumption, CPA groups the traces based on power consumption patterns. The power model used for grouping is the Hamming Weight (HW)[

20], which categorizes each trace based on the number of '1s' in the binary representation. For AES-128, HW values range from 0 to 8, creating a total of 9 groups, as shown in

Figure 2. By this method, the intermediate value x (the output of the first round S-Box) is obtained for a set of random plaintexts and hypothetical keys. The traces y, recorded during the encryption process, are then used in correlation coefficient calculations to predict the correct key for the Device under Test (DUT) based on the results of the correlation analysis, as shown in Equation 1.

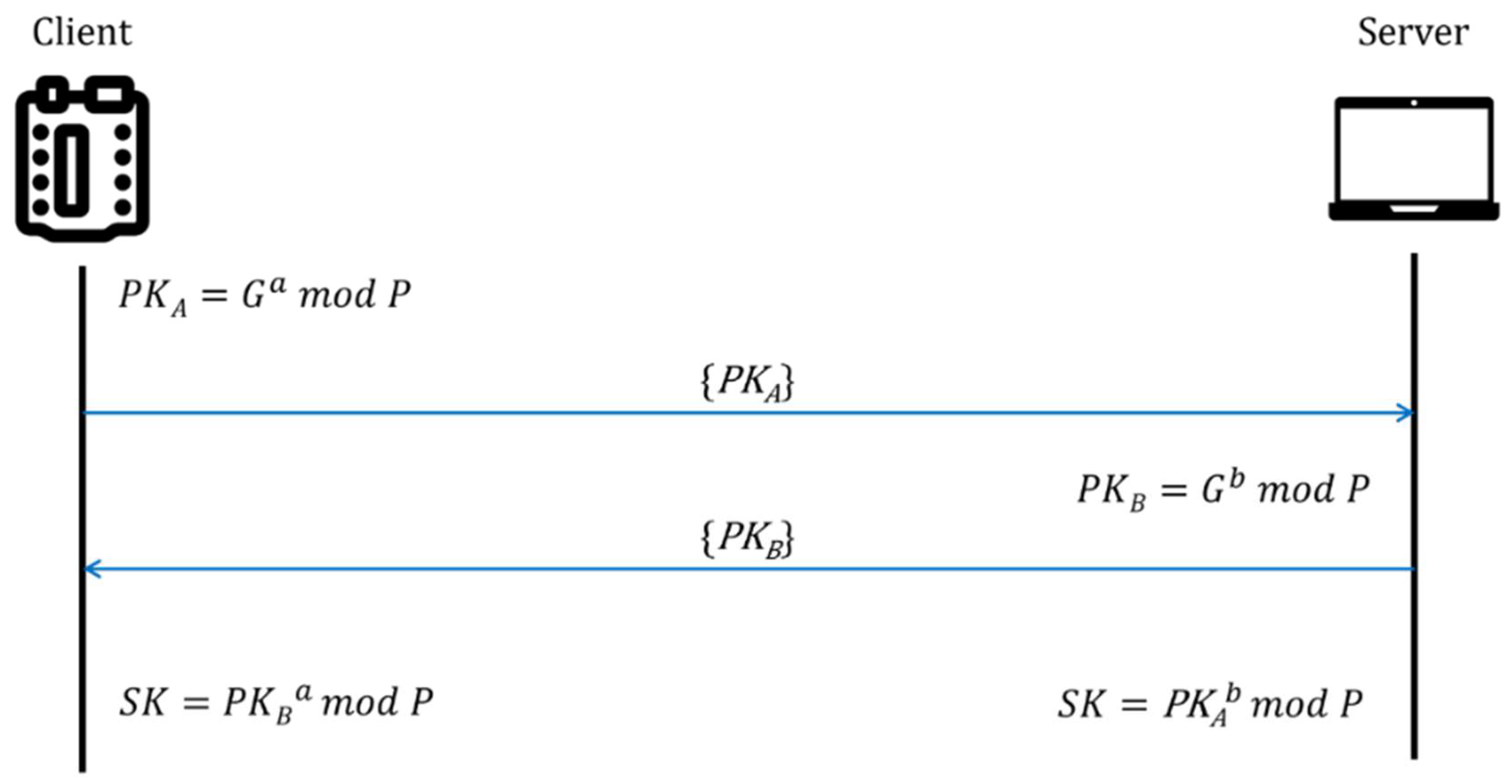

2.3. Diffie-Hellman (D-H) Key Exchange Mechanism

D-H key exchange mechanism was introduced in 1976[

22], which become a fundamental milestone in modern cryptography. D-H is one of the pioneering protocols in public key cryptography, enabling two parties securely establish a shared symmetric key without share prior key over an insecure channel. Many communication protocols utilize D-H to establish a secure channel by exchanging information over a public network. There are several variations of D-H, including the Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange (ECDH). Given the hardware limitations in IoT environments, the D-H implementation in this study was chosen for its minimal power consumption, ensuring compatibility with power-limited IoT device.

The Lightweight version of D-H employed in this study is based on the discrete logarithm problem, expressed as . The process begins by defining a base G and a prime modulus P. The IoT device and the server each select private keys, a and b, respectively. The corresponding public keys and are then generated and exchanged over the insecure channel. Upon receiving each other’s public keys, the parties compute the shared symmetric key and , resulting in a common secret key SK.

As illustrated in

Figure 3, in order to derive the final shared key

SK from the public values, an attacker would need to solve for the private keys

or

, which is computationally infeasible without access to those private keys. D-H ensures strong security by relying on the exchange of public keys and the difficulty of solving the discrete logarithm problem, even over an insecure channel. This mechanism is leveraged in our study to implement dynamic key replacement, providing protection against SCA.

Common Wireless Communication Protocols in IoT

There are many types of wireless communication protocol for IoT devices. The most common are Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, Zigbee, and LoRa[

23,

24,

25,

26]. Each has different features and benefits.

Table 1 compares each of the protocol’s property and advantages.

Wi-Fi is the most pervasive and reliable protocol mentioned above, offering high data transmission rates, which is the best candidate for smart home environments. Due to its widespread used, Wi-Fi has become the most common wireless communication protocol. Furthermore, many existing devices and infrastructure have been optimized and integrated to support it. In smart home scenarios, large amounts of real-time data transmission and multimedia applications use communication protocols with high bandwidth and reliability. Despite the vulnerability of Wi-Fi to network attacks, particularly when handling sensitive personal data in open environments, this is one of the main focuses of this research. The aim of this study is to enhance the security of data transmitted over Wi-Fi and mitigate the risks posed by SCA by improving encryption key protection mechanisms.

3. Research Methodology

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Experimental Framework

In network environments, sensitive information must be encrypted before transmission to prevent unauthorized access. In resource-constrained IoT systems, AES encryption has widely used. While AES provides robust security, the encryption operations were executed by microcontrollers within the devices, which may leak physical signals during the encryption process. These signals could be exploited by attackers to extract the encryption keys, thus compromising the encrypted messages. To counter SCA on IoT devices, we proposed a dynamic key replacement AES encryption algorithm based on MTD [

14] concept. This approach changed the initial encryption key before an SCA can succeed.

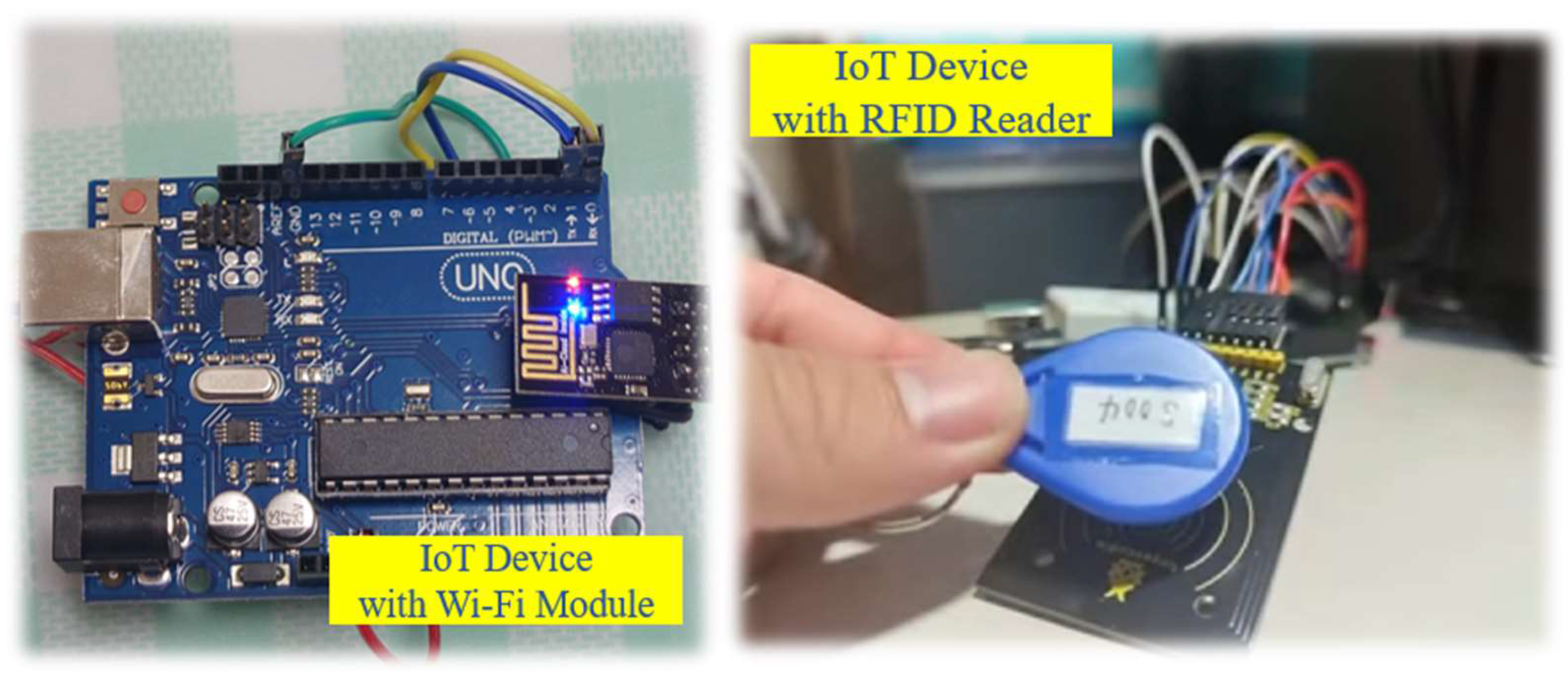

To validate the effectiveness of this defense mechanism, we implemented a wireless communication platform for a smart access control system, which included an RFID-based access control system (Arduino UNO), a Wi-Fi module (ESP8266), and access control software. A laptop executed access control software as client and server in IoT environment, handling communication between the devices. The smart application system was set up using actual RFID tags, with an RFID reader connected to Arduino UNO. When RFID tags are read, the data encrypted by AES and transmitted via Wi-Fi module to access control software for decryption.

Once the encryption and decryption process of the access control data is validated, we conduct an SCA on the system. Using an oscilloscope, we captured electromagnetic radiation emitted during the execution of encrypt operations on Arduino UNO, specifically targeting the power consumption data. The oscilloscope used an electromagnetic probe to capture the traces, which sent to the control computer. These traces were processed by a GPU computing platform using CPA to determine the success of the key extraction by analyzing the number of successfully attacked sub-keys. The experimental setup is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Once we confirmed the IoT transmission scenario and SCA setup, we modified the AES encryption algorithm to enable dynamic key replacement. To evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of key replace, we performed key replace after capturing different amounts of traces and observed the frequency limitations of the key replace. The configuration of the client, server, and the dynamic key replacement AES design will be discussed detail in the following sections.

3.2. Client-side Setup

The communication scenario is built around wireless transmission of access control card data using Wi-Fi. We developed a simple IoT access control system using the Arduino UNO NodeMCU v3, the ESP8266 Wi-Fi module, and the MFRC552 RFID sensor module. The client-side setup and operation are as follows:

First, we include the header files ESP8266WiFi.h, MFRC522.h, and config.h. The first two libraries correspond to the Wi-Fi module and the RFID sensor module, while config.h defines the Wi-Fi SSID, password, default AES-128 encryption key, server IP, port, and the base and modulus values for the D-H key exchange.

Next, the setup() function is used to initialize the MFRC522 module, connect to the specified Wi-Fi network, and establish communication with the server. The loop() function continuously monitors the MFRC522 sensor for access card UID readings, records the number of data packets transmitted, and encrypts the UID string using a custom AES-128 function aes128(). Then the encrypted data is sent to the server for processing.

To ensure transmission accuracy, the number of packets recorded by the client is compared with the number received by the server. After a certain number of transmissions, the client initiates a key negotiation with the server using the D-H protocol to generate the next AES encryption key. The actual client-side setup is illustrated in

Figure 5.

3.3. Server-Side Setup

The server-side program for the smart access control system was developed in Java, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The program utilizes the following libraries: info.picocli:picocli, javax.crypto, and java.net. After starting the server through the command line with the specified port parameter, the java.net.ServerSocket is used to listen on the designated port. Once a communication channel is established, the server connects to the client and begins exchanging data. During the connection, the D-H key exchange is used to generate the next key from the initial key. The messages received from the client (Arduino) are decrypted using Cipher.getInstance("AES/ECB/NoPadding"). If the message is in RFID format, the system searches for the corresponding UID and triggers specific actions, such as sending HTTP requests or logging the access time into a database. After receiving a certain number of messages, the server re-initiates the D-H key exchange with the client to generate the next AES-128 decryption key.

3.4. Dynamic AES Key Replacement Mechanism

Although this study utilizes the AES-128 encryption algorithm, which involves only a 128-bit key, the primary focus is on addressing the issue of power consumption or electromagnetic signal leakage caused by the repeated use of the same key during AES encryption. This is a well-known vulnerability exploited by SCAs. It is important to note that using a longer key, such as AES-256, does not significantly mitigate this risk, as the root of the problem lies in key reuse, not key length. Therefore, while AES-256 could be implemented, that would considerably increase computational overhead, especially in resource-constrained IoT devices.

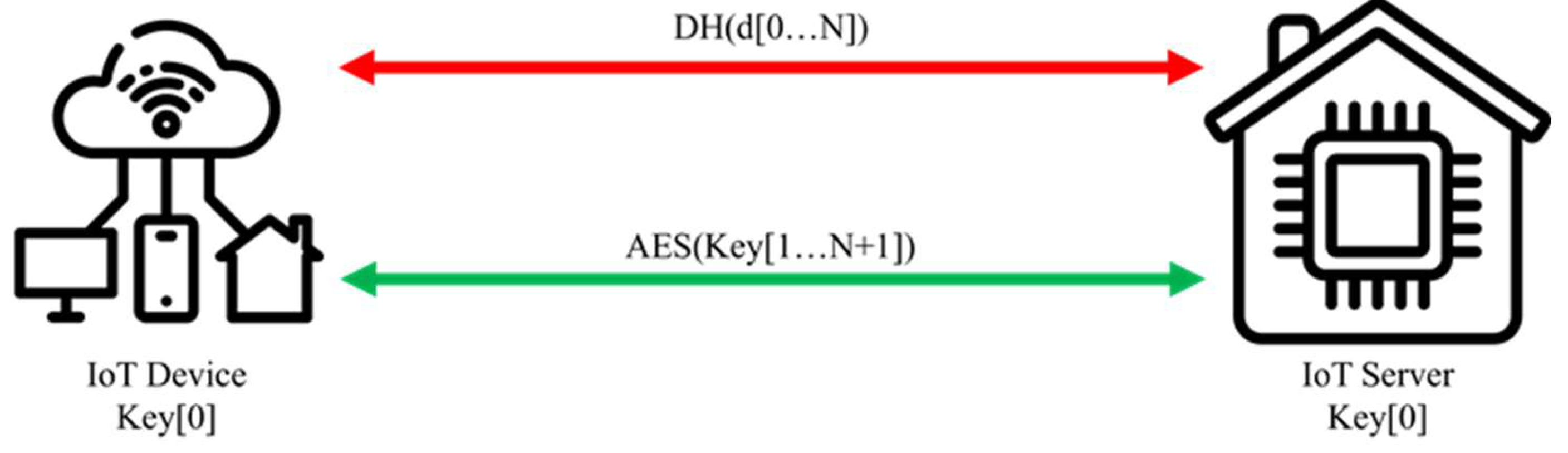

In the proposed mechanism, as illustrated in

Figure 7, Key[0] is the pre-configured initial key, which is only used during the initial connection negotiation. Once the connection is established, the system uses the D-H key exchange protocol to generate the first 32-bit hopping operator d[0]. It is critical to forbid using Key[0] to encrypt via the AES channel to avoid potential key leakage. If the system reboots multiple times and repeatedly uses Key[0] to encrypt, it could lead to the leakage of AES encryption characteristics, increasing the risk of successful SCA.

The operator d[0], obtained through negotiation, is combined with the initial key Key[0], and a hash function is applied to generate the next encryption key Key[

1] (i.e., Key[

1] = hash(Key[0], d[0])). This key replacement mechanism effectively reduces the risk of SCAs because the core of AES encryption lies in its randomness and non-repetitiveness. SCA attacks in AES-128 systems typically exploit predictable electromagnetic signals that arise from repeatedly using the same key. Thus, frequent key reuse dramatically increases the likelihood of a successful attack.

Figure 8 shows the key replace process. After every M data transmission, the system generates the next hopping operator through the D-H key exchange, producing a new encryption key, thereby preventing key reuse. To ensure the randomness of each D-H key exchange, we selected using high-quality random numbers as private keys. In case of that IoT devices cannot access the internet, the random number seed can be generated by reading multiple analog values from the device's analog PIN using the analogRead() function in the Arduino UNO. This serves as a substitute for the system's default time-based random number generation. This dynamic key replacement mechanism significantly enhances the security of IoT systems, particularly in long-term, low-power devices, as it effectively prevents SCAs arising from electromagnetic signal leakage.

Microcontrollers are used a lot in the IoT. With the advantages of cheap and low power overhead, which makes them suit for large-scale use. However, they can't do complex calculations, which makes it hard to use them for secure cryptographic protocols. In this study, we propose a way to use D-H key exchange mechanism on resource-constrained microcontrollers, like Arduino Uno.

Our approach starts with two numbers: a generator (G = 37) and a prime modulus (P = 147483647). These values are chosen to balance security with efficiency, making them well-suited for resource-constrained IoT devices. Both the IoT device and the server independently select private keys, denoted as a and b, respectively. Each side then computes its corresponding public key as Equation 2:

These public keys are exchanged over an unsecured channel. Upon receiving the public key from the other party, both the IoT device and the server compute the shared symmetric key

SK as Equation 3:

At the conclusion of this process, both parties have independently derived the same symmetric key,

SK, which can now be used for secure, encrypted communication.

Table 2 provides further details on the key exchange process, outlining the step-by-step operations carried out by both the IoT device and the server.

This lightweight implementation of the D-H key exchange offers a highly efficient solution for secure key distribution in IoT environments. By carefully optimizing the choice of parameters and reducing the computational burden on the microcontroller, this approach ensures that even devices with minimal processing power, such as the Arduino Uno, can securely exchange cryptographic keys without compromising their limited resources.

The proposed method not only meets the security demands of modern IoT applications but also demonstrates excellent adaptability to the constraints of real-world deployments, where both energy consumption and processing capabilities are limited. This lightweight D-H mechanism is ideal for scalable IoT networks that require robust security without sacrificing performance.

4. Experimental Results

This chapter presents a detailed analysis of the experimental results for the proposed "Efficient Key place Mechanism for Lightweight IoT Microcontrollers." The experiment aims to verify the correctness of the AES encryption and decryption processes, evaluate the time efficiency of the dynamic key replacement mechanism, and assess the effectiveness of different key replace frequencies in defending against SCAs. Through the analysis of experimental data, we demonstrate the mechanism's actual performance in enhancing the security and operational efficiency of IoT devices. The following sections detail the experimental design and results.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The experimental setup, as shown in

Figure 9, establishes a testing platform for lightweight IoT devices to simulate and evaluate the encryption key protection mechanism and its ability to resist SCAs. In this experiment, an Arduino UNO is used as the client device for data transmission and is set as the target for SCA. The server-side is implemented by Java, responsible for receiving and verifying data from the client to ensure the integrity and correctness of the transmission. The attack platform is configured based on the methods proposed in [

27], with both hardware and software setup accordingly. During the attack, the H-Field probe of a NEWAE is used to capture the electromagnetic radiation emitted by the client device during AES encryption. These signals are recorded as trace data for further analysis.

Figure 10 provides a physical image of the electromagnetic signals being captured via a loop antenna, which are processed in real-time using PicoScope 5244B oscilloscope. The captured traces are transmitted to the control computer for formatting and preprocessing, and subsequently sent to the computing server for further analysis. The server runs a CPA program, following the configuration by Peng et al. [

28], to conduct attack analysis and return results. This setup effectively simulates real-world SCA scenarios in an IoT environment and validates the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed experimental methodology.

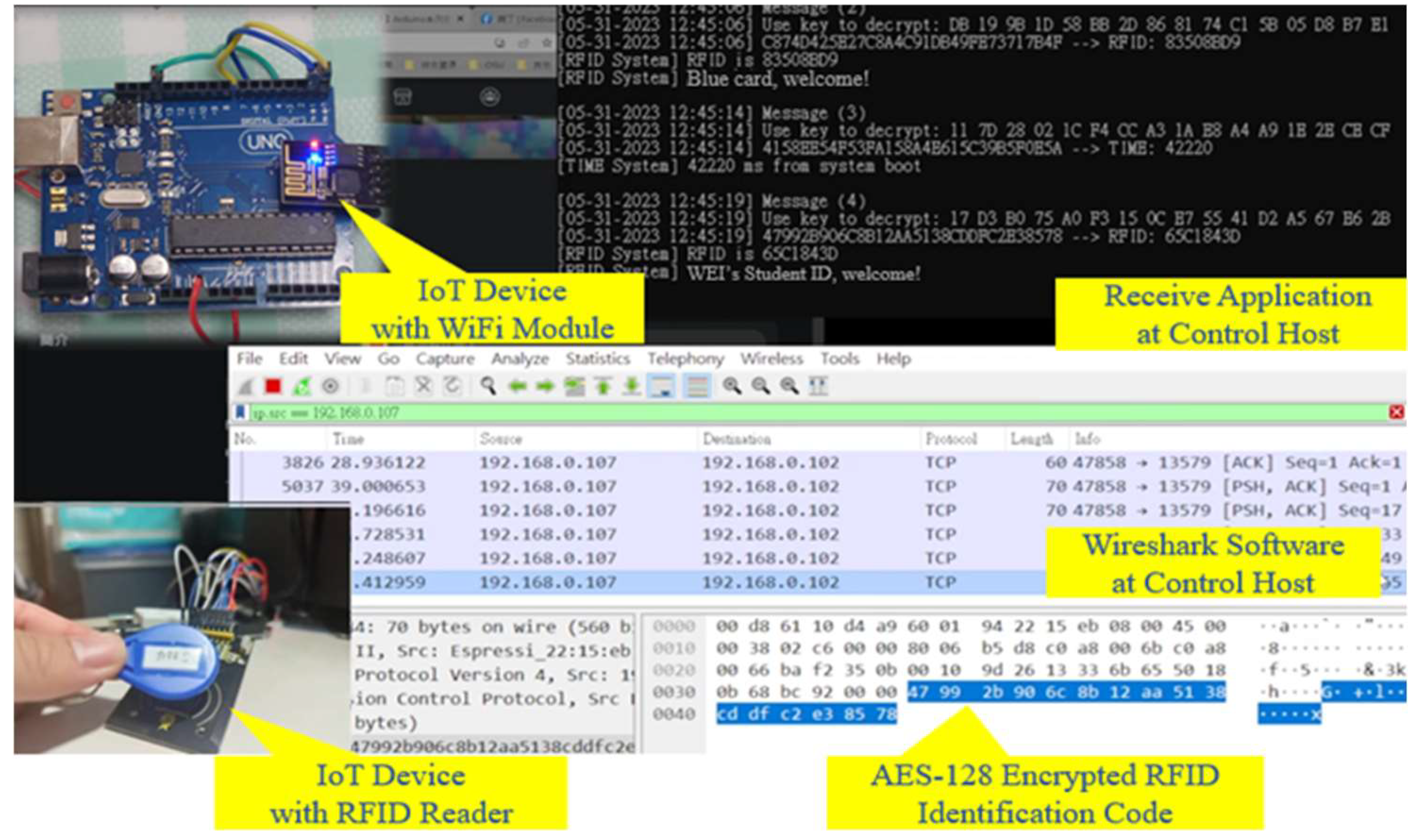

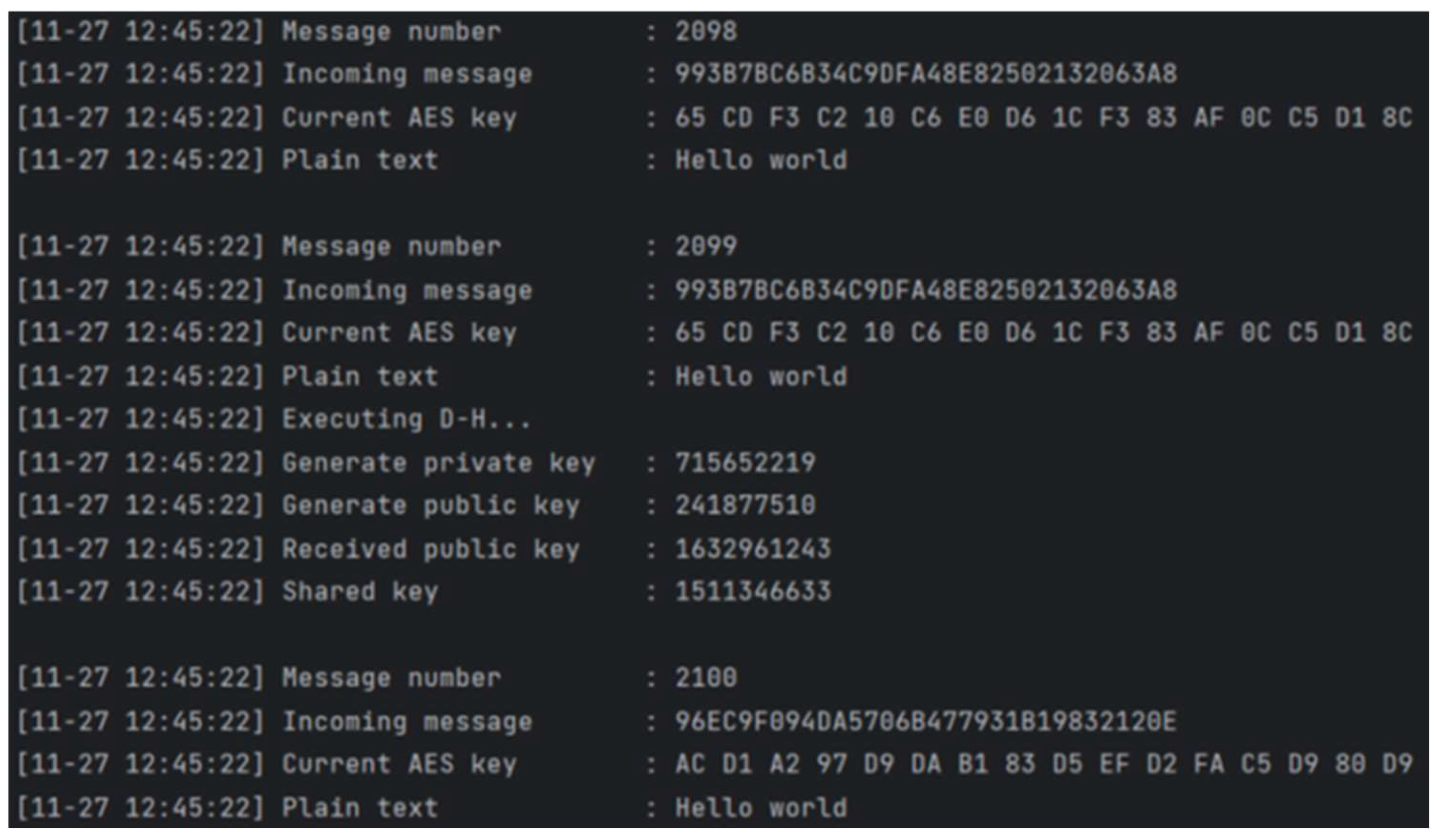

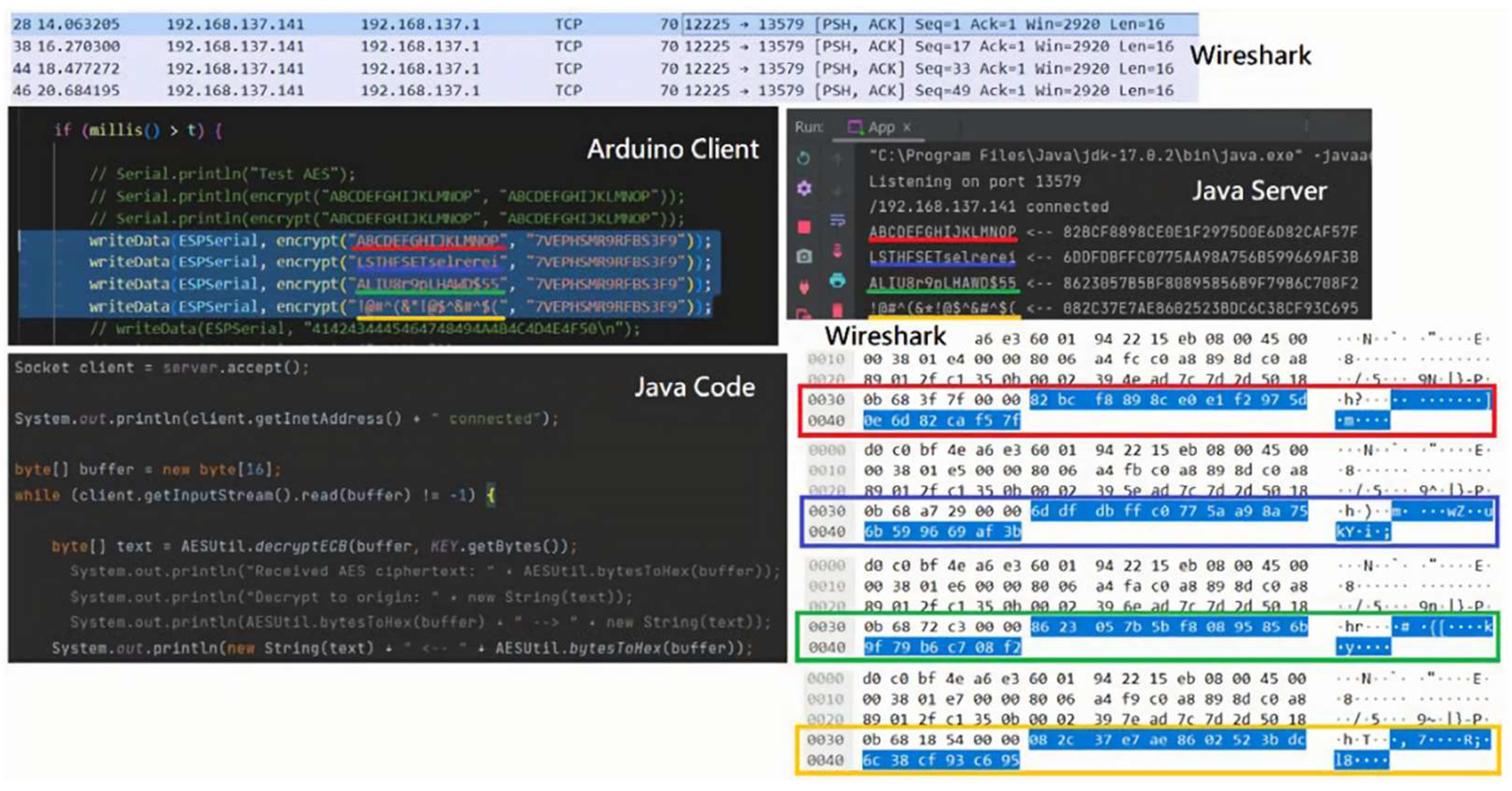

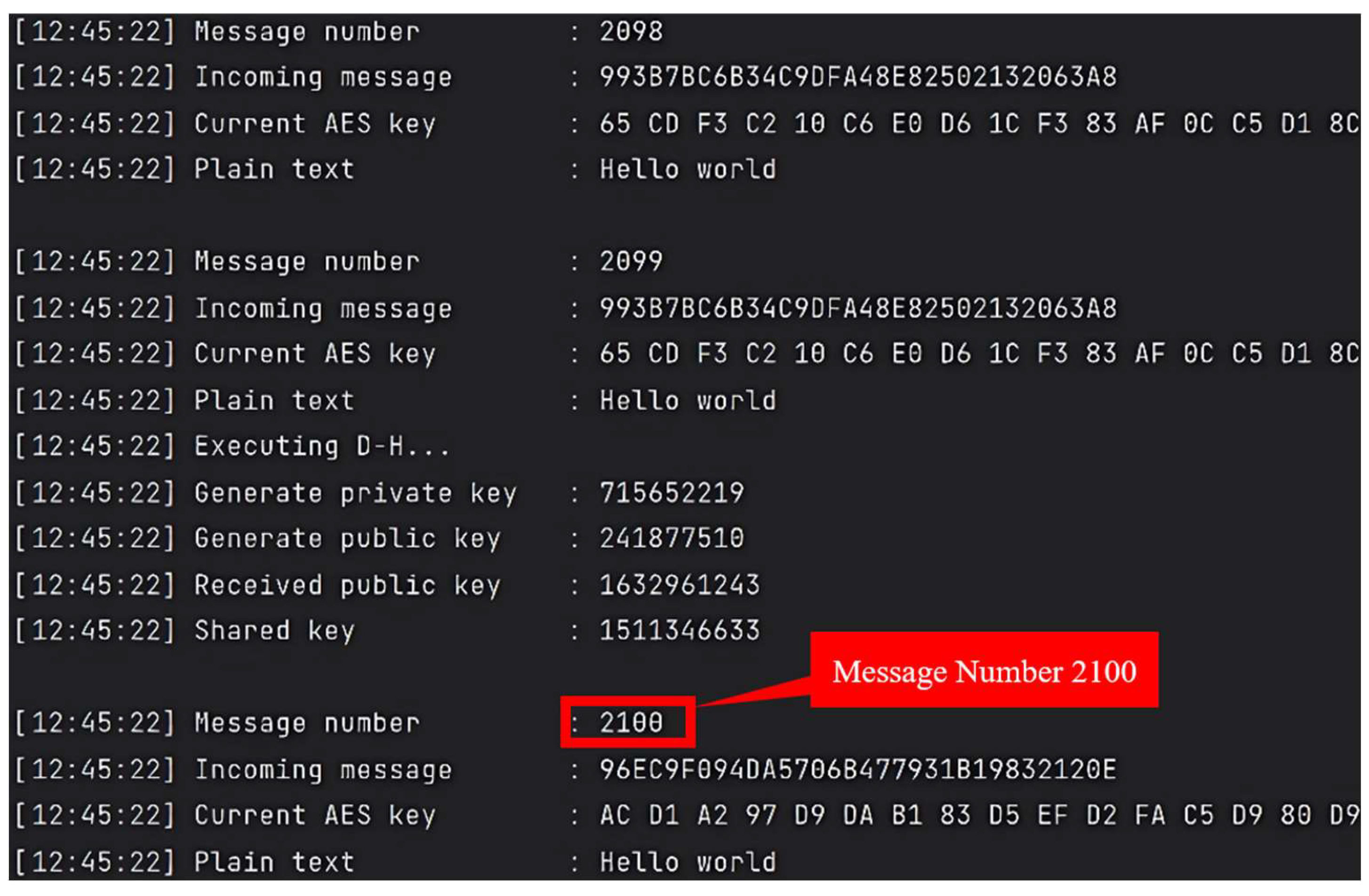

4.2. Verification of AES Encryption and Decryption

Before conducting SCA, we first verify the correctness of data encryption and decryption between the client-side and server-side. By lightweight D-H protocol, an AES-encrypted channel is established between the Arduino UNO and the control computer by key[0], this channel ensures the confidentiality and integrity of transmitted data. After successfully establishing the secure channel, encrypted test messages are transmitted to the server. During the transmission process, we monitor and analyze packet transmission by Wireshark, we observe the packet transmission of encrypted messages as shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, confirming the correctness of encrypted packets reach the server. The server then performs the decryption process to verify the integrity and correctness of the entire encrypted communication. The experimental results show that the server successfully decrypts the received encrypted packets, restoring them to their original form. Notably, in

Figure 12, Message Number 2100 shows the key replace during the encryption process, demonstrating the effectiveness of the AES encryption and decryption mechanism in both the client-side and server-side, ensuring reliable data transmission.

4.3. Time Efficiency Analysis of Dynamic Key Replace

Due to the computational limitations of microcontrollers in IoT devices, it is crucial to evaluate the time efficiency of the proposed key place mechanism to ensure it can operate effectively in resource-constrained environments. Experiments were conducted on Arduino UNO development board to test the key replacement mechanism at different frequencies. During the experiment, plaintext messages were transmitted, and the AES-128 encryption key was replaced at various frequencies. Total 3,000 encrypted packets were transmitted for each scenario. Throughout the process, we recorded the time required for each transmission, allowing us to assess the time overhead associated with different key replace frequencies.

Table 3 provides a detailed breakdown of the average transmission time per packet when the key was replaced after every 1, 10, 30, and 50 packets. To contextualize these results with real-world applications, we compared them to existing access control systems, where the typical card swipe operation takes between 0.5 and 1 second. Based on the experimental results, the key replacement mechanism designed in this study demonstrated significantly lower transmission times at all tested frequencies, indicating that the mechanism provides superior time efficiency while maintaining security. This makes the proposed mechanism highly suitable for practical implementation in smart access control systems.

4.4. SCA Results with Different Key Replace Frequencies

In this study, a wireless loop antenna was employed to receive characteristic signals, SCA was executed on Arduino UNO microcontroller, and electromagnetic signals were captured under the experimental conditions depicted in

Figure 9. Correlation analysis was utilized to assess the efficacy of the attack in compromising the cryptographic keys.

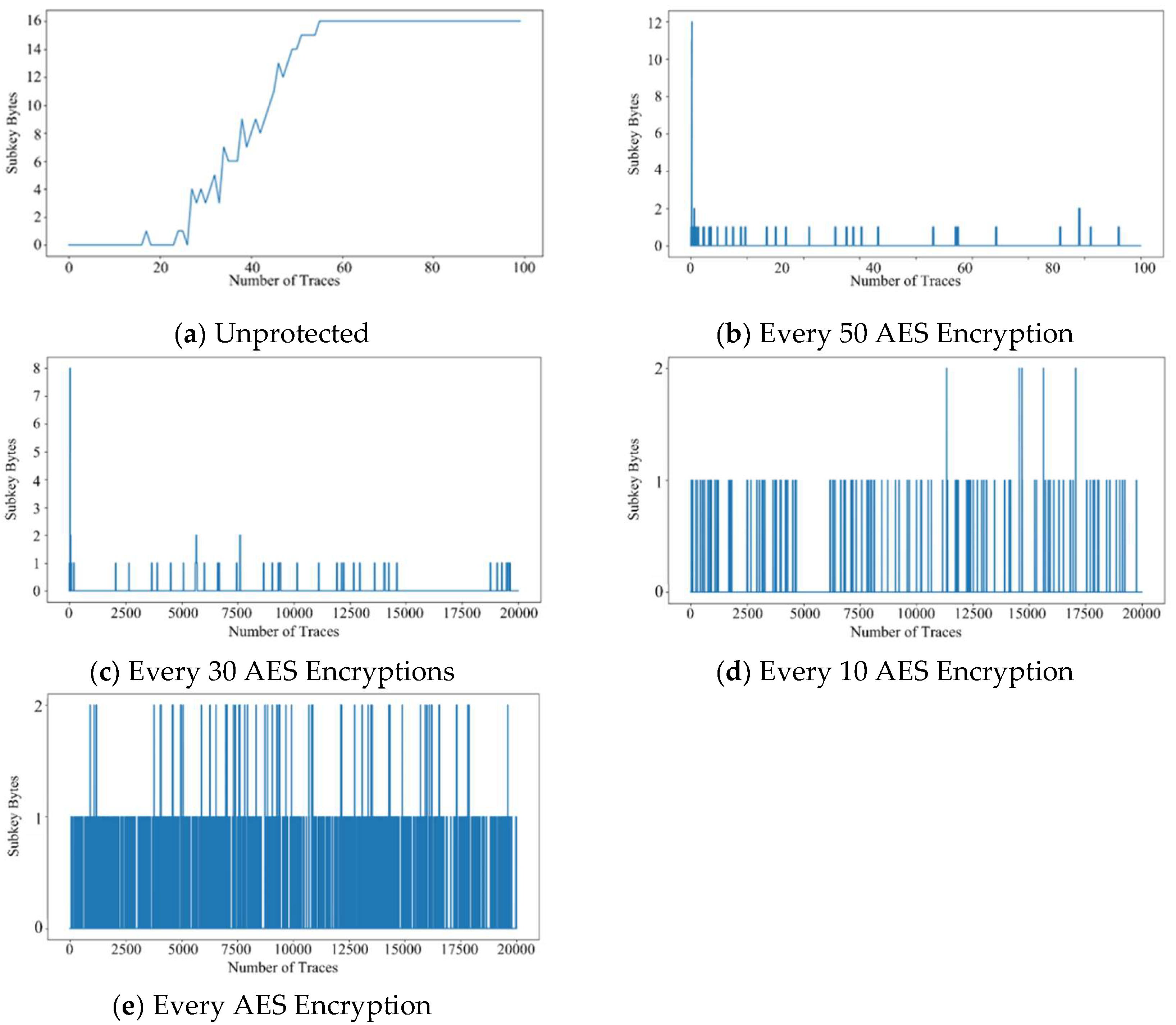

Figure 12a presents the results of an SCA executed on the microcontroller during AES encryption, without any protective countermeasures in place, the x-axis represents the number of data traces required to carry out the attack, while the y-axis indicates the number of successfully recovered key bytes. Our findings reveal that, without protected, an attacker can fully recover all 16 subkeys of the AES-128 encryption algorithm with just approximately 55 traces.

To further evaluate the efficacy of the proposed dynamic key replacement mechanism, we executed SCAs at various intervals of encryption operations, modifying the encryption key at different frequencies. The results as shown in

Figure 12b to

Figure 12e, illustrate a significant reduction in the effectiveness of the SCA as the frequency of key replace increases.

Table 4 summarizes these findings, underscoring the impact that key replace frequency has on an attacker’s ability to compromise the encryption keys.

Figure 12b: When the key was replaced every 50 encryption operations, the attacker was able to successfully retrieve 12 subkeys.

Figure 12c: At a replace interval of 30 encryption operations, only 8 subkeys were compromised.

Figure 12d: Reducing the key replace interval to 10 encryption operations resulted in only 2 compromised subkeys.

Figure 12e: Replacing the key after every single encryption cycle limited the attacker’s success to just 2 subkeys.

These results clearly demonstrate the inverse relationship between key replace frequency and the success rate of SCAs. The more frequently the encryption key is replaced, the more difficult it becomes for the attacker to successfully compromise the cryptographic keys. Notably, the strategies of replacing the key after every 1 and 10 encryption operations proved particularly effective in thwarting template attacks, which are often capable of breaching encryption with minimal traces.

As reported by Wu et al. [

29], deep learning and template attack techniques can allow attackers to recover encryption keys using only a small number of traces. However, the high-frequency key replacement mechanism proposed in this study have substantially reduced the number of subkeys that could be successfully retrieved by such attacks. The results provide compelling evidence that the dynamic key replacement mechanism significantly enhances the security of IoT devices, bolstering their resistance to SCAs and ensuring robust protection of sensitive data.

5. Conclusion

In IoT scenario, encryption is important for keeping data safe and defending against attacks. If SCAs are not stopped, encryption keys can be stolen, which means sensitive information can be accessed and the whole system could be at risk. Traditional hardware-level defense mechanisms are not suitable for IoT devices because of the unaffordable cost like power overhead or circuit area overhead. Consequently, it is imperative to implement software-based defense strategies to guarantee system security without impairing computational performance.

In this study, we proposed a dynamic key replacement mechanism for AES encryption, which effectively enhances the system's resilience against SCA by modifying the encryption keys before an attack can successfully recover them. A lightweight key replacement mechanism was designed based on Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol, which is straightforward to implement and particularly well-suited for resource-constrained microcontroller environments. This mechanism is not limited to AES encryption but can also be applied to other encryption systems requiring key negotiation.

The experimental results demonstrate that as the frequency of key replace increases, the system's ability to withstand SCAs is significantly enhanced. Specifically, when the key was replaced after every one or ten encryptions, the success rate of SCA dropped substantially. These findings confirm the effectiveness of the dynamic key replacement mechanism in enhancing the security of IoT devices against SCAs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under Grants NSTC 113-2221-E-035-075 -, and the Longmau Technology Co., Ltd., under Grant 12B1001T.

References

- Statista. Number of IoT connections worldwide 2022-2033, with forecasts from 2024 to 2033. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Moini, S.; Tian, S.; Holcomb, D.; Szefer, J.; Tessier, R. Power Side-Channel Attacks on BNN Accelerators in Remote FPGAs. IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems 2021, 11, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.B.; Prvulovic, M.; ZajićA, A. Electromagnetic Side Channel Information Leakage Created by Execution of Series of Instructions in a Computer Processor. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2019, 15, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuffri, A.; Zwalua, M.; Reinbrecht, C.R.W.; Hamdioui, S.; Taouil, M. Applying Thermal Side-Channel Attacks on Asymmetric Cryptography. IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems 2021, 29, 1930–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaumont, P.; Tiri, K. Masking and Dual-Rail Logic Don’t Add Up. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems (CHES 2007), Vienna, Austria, 10-13 September 2007; pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, K.; Paar, C. Higher Order Masking of the AES. In Proceedings of the Topics in Cryptology (CT-RSA 2006), San José, CA, USA, 13-17 February 2006; pp. 208–255. [Google Scholar]

- Baseri, Y.; Chouhan, V.; Ghorbani, A. Cybersecurity in the Quantum Era: Assessing the Impact of Quantum Computing on Infrastructure. arXiv Cryptography and Security 2024, 10659, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, S.; Lu, H.Y.; Kumar, A.; Yau, D. Hacker types, motivations and strategies: A comprehensive framework. Computers in Human Behavior Reports 5 2022, 100167, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, P.S.; Tran, N.; Craig, B.; Dezfouli, B.; Liu, Y. Analyzing the Resource Utilization of AES Encryption on IoT Devices. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC 2018), Honolulu, HI, USA, 12-15 November 2018; pp. 1200–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, S.; Rehman, T.; Fatima, M.; Khan, S.; Ali, M.A. Comparative Analysis of Aes and Rsa Algorithms for Data Security in Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the The 7th International Electrical Engineering Conference (IEEC 2022), Karachi, Pakistan, 25–26 March 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, M.; Majumder, A. Side-Channel Attack in Internet of Things: A Survey. In Applications of Internet of Things: Proceedings of ICCCIOT 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 213–222. ISBN 978-981-15-6198-6. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.; Zhao, B.; Xu, B.; Wang, L.; Ren, G.; Liu, Z. Enhanced Message Authentication Encryption Scheme Based on Physical-Layer Key Generation in Resource-Limited Internet of Things. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4639419 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Rawat, J.; Kumar, I.; Mohd, N.; Rana, K.K.S.; Pathak, N.; Gupta, R.K. IoT-Based Home Automation System Using ESP8266. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Computing and Communications (ICICC 2023), New Delhi, India, 17-18 February 2023; pp. 695–707. [Google Scholar]

- Vuppala, S.; Mady, A.E.; Kuenzi, A. Moving Target Defense Mechanism for Side-Channel Attacks. IEEE Systems Journal 2020, 14, 1810–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemen, J.; Rijmen, V. The Design of Rijndael The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES); Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-3-662-60769-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.W.; Tsai, K.Y.; Weng, W.M.; Lin, C.C.; Hong, Y.Y.; Wang, G.L. Implementation and Analysis of Side-Channel Attack Mitigation Based on Autoencoder. Communications of the CCISA 2023, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. Lightweight Cryptography Standardization Process: NIST Selects Ascon. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/News/2023/lightweight-cryptography-nist-selects-ascon (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. Differential Power Analysis. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology (CRYPTO 1999), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 15-19 August 1999; pp. 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Brier, E.; Clavier, C.; Olivier, F. Correlation Power Analysis with a Leakage Model. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems (CHES 2004), Cambridge, MA, USA, 11-13 August 2004; pp. 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Messerges, T.S. Using Second-Order Power Analysis to Attack DPA Resistant Software. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems (CHES 2000), Worcester, MA, USA, 17-18 August 2000; pp. 238–251. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, A.; Niu, Y.; Shang, N.; Xu, R.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, L. Side-Channel Attacks and Countermeasures for Identity-Based Cryptographic Algorithm SM9. Security and communication networks 2018, 2018, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffie, W.; Hellman, M.E. New Directions in Cryptography. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1976, 22, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, F.K.; Vun, N.C.H. Securing IoT for smart home system. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Consumer Electronics (ISCE 2015), Madrid, Spain, 24-26 June 2015; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Collotta, M.; Pau, G. A Novel Energy Management Approach for Smart Homes Using Bluetooth Low Energy. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2015, 33, 2988–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zualkernan, I.A.; Al-Ali, A.R.; Jabbar, M.A.; Zabalawi, I.; Wasfy, A. InfoPods: Zigbee-Based Remote Information Monitoring Devices for Smart-Homes. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2009, 55, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.L.; Leu, F.Y.; You, I.; Chang, S.W.; Hu, S.J.; Park, H. Low-Power AES Data Encryption Architecture for a LoRaWAN. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 146348–146357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.W.; Lin, C.C.; Hong, Y.Y.; Liu, J.R.; Yeh, C.H.; Tsai, K.Y. Research and Analysis of the Effects of Different Shielding Materials on Resisting Side-Channel Attacks on IoT Device Microcontroller. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Cryptography, Security and Privacy (CSP 2024), Osaka, Japan, 20-22 April 2024; pp. 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.Y.; Hong, W.C.; Li, J.T.; Huang, S.J. Framework for efficient SCA resistance verification of IoT devices. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Applied System Invention (ICASI 2018), Chiba, Japan, 13-17 April 2018; pp. 355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Perin, G.; Picek, S. The best of two worlds: Deep learning-assisted template attack. IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems 2022, 3, 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).