1. Introduction

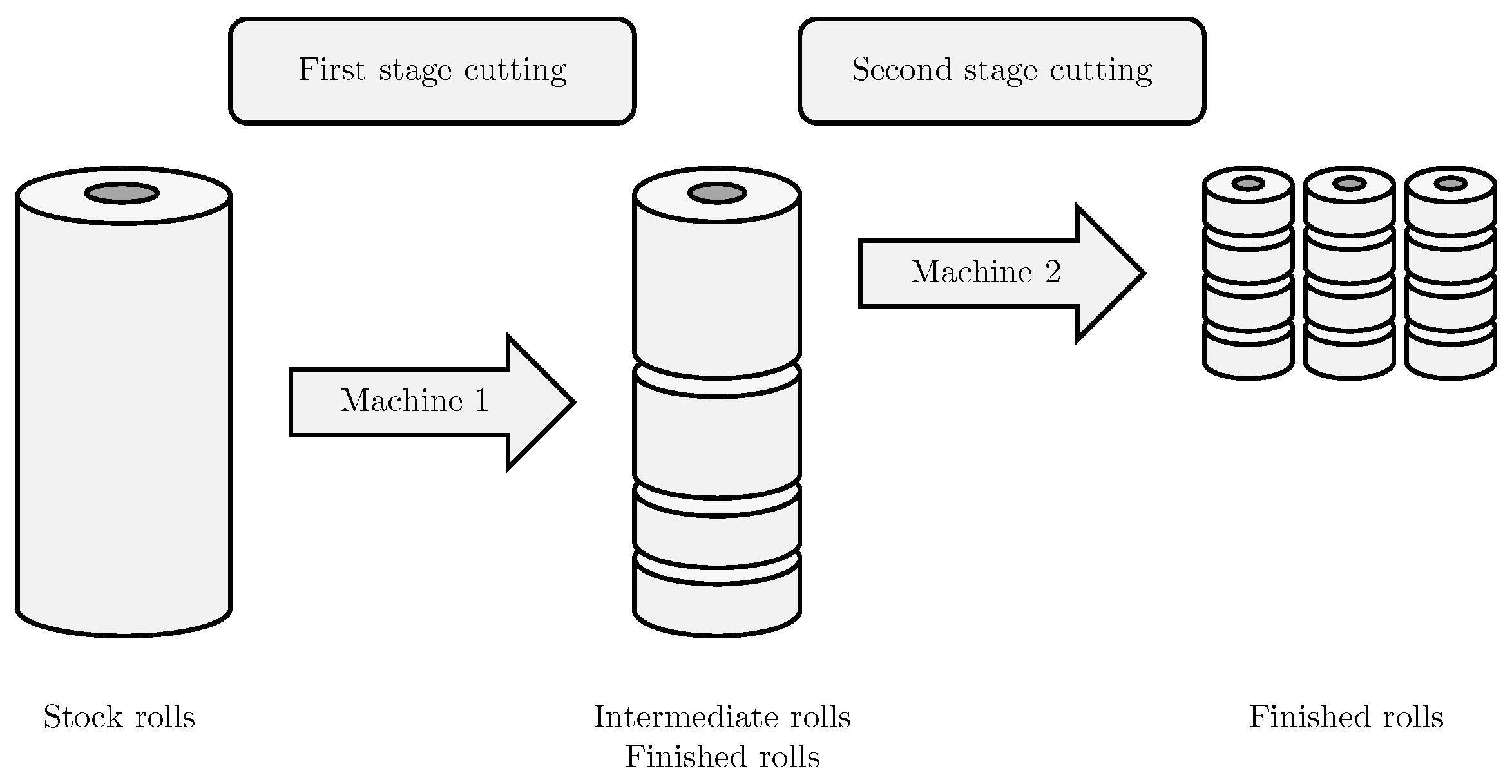

Many manufacturing processes, including paper rolls, plastic packaging, and metal rolling, involve the production of coils of various sizes and quantities, tailored to meet specific customer demands. The slitting process can be divided into distinct stages, as outlined in

Figure 1. These stages are categorized into two types:

splitting and

slitting, based on whether semi-finished or finished rolls are produced. This division is required by the intermediate conversion processes and the minimum and maximum input widths that slitters can handle, as defined by their technological specifications.

Slitting refers to the final cutting of a roll, exiting the production cycle. In contrast,

splitting involves cutting an intermediate roll that will be further processed in subsequent stages. A single cutting stage encompasses the process of slicing an input roll, known by various names such as stock object or mill roll, into smaller rolls called items. These items may be both narrower and shorter. In this production environment, there exists an additional relationship between stock objects and items: during the splitting phase, intermediate rolls are produced, which serve as finished rolls for the upstream stage and as mill rolls for the downstream stage.

According to the typology proposed in [

3] and the refined classification discussed in [

16], the development of slitting programs falls within the expansive optimization domain of Cutting and Packing problems. These problems are fundamentally characterized by two core entities: the stock objects, representing the inputs, and the items, representing the demand.

Specifically, by integrating dimensionality, assignment, and assortment, this problem can be succinctly represented by the 1.5/V/I/R tuple or as a 1.5D-rectangular-SSSCSP. Notably, the assignment of dimensionality in this context deviates from conventional interpretations. As described in [

2] and [

6], traditional two-dimensional problems account for both width and length as degrees of freedom in generating cutting patterns. In contrast, the One-and-Half-Dimensional (1.5D) problem constructs patterns by combining items (or final orders) based on their width, analogous to a one-dimensional problem. However, the number of feasible patterns is constrained by the length of the input rolls. Specifically, the length of a pattern corresponds to the length of the orders cut in that particular combination, and patterns can be generated only until the total length of the input roll is exhausted. Consequently, the second dimension functions partially as a production constraint rather than a degree of freedom in the pattern generation process.

The shapes of both items and objects are rectangular, and their orientation is fixed. As a result, the items must align adjacently, akin to the two-dimensional problem with guillotine cuts in the exact case, but only along their shorter edges. The objective, therefore, is to combine orders in both the transverse and longitudinal directions of the slitter, subject to length constraints. These constraints are intrinsically linked to the availability of stock rolls and the capability to slit rolls of varying lengths within the same setup, which are restricted to a discrete set of predefined values.

Considering these factors, this problem can be classified as a One-and-Half Two-Stage Cutting Stock Problem (1.5D-TSCSP). The relationships between orders are influenced not only by the transitions between stages but also by the varying lengths within the same stage. The following scenarios may arise:

Case 1: The first and second stages have the same length. This scenario reduces to a one-dimensional problem, which has been extensively studied in the literature.

Case 2: Only one length is present at the first stage and only one length at the second stage, but they are different. Each unit of intermediate product must always produce the same number of patterns in the second stage.

Case 3: Multiple lengths are present at both the first and second stages, which are different and cannot be mixed. In each pattern, the length must be fixed.

Case 4: Multiple lengths are present at both the first and second stages. Within a single pattern, there can be at most two different lengths, provided that one is an integer multiple of the other.

In this study, we focus on Case 3, which addresses the intricate challenges associated with managing multiple roll lengths within a two-stage cutting process, while maintaining the restriction of non-mixing lengths within individual cutting patterns. The primary objective is to develop and propose solution methodologies capable of efficiently addressing the computational complexity inherent in this problem. In the two-stage cutting process, distinct cutting patterns are generated for each stage, as well as for each intermediate order between the first and second stages. These intermediate orders impose constraints on the number of rolls that can be cut, thereby influencing the structure of the cutting patterns. As a result, the problem exhibits combinatorial growth both in the dimension of potential patterns and in the dimension of intermediate orders, the latter being indeterminate a priori. Simplified versions of the problem, represented by Cases 1 and 2, can be derived as special instances of Case 3 by imposing additional constraints or relaxing specific complexities. Conversely, Case 4 extends the framework to incorporate advanced technological constraints relevant to specialized manufacturing processes. For example, duplex rewinding, which facilitates the simultaneous processing of a single roll on both sides, introduces operational nuances. However, it does not necessitate significant alterations to the underlying mathematical modeling framework.

In

Section 2, we present a comprehensive review of the key contributions available in the literature, providing context and highlighting the state-of-the-art methodologies relevant to the problem domain.

Section 3 offers a formal definition of the problem and situates it within the established classification frameworks discussed in the literature. The proposed solution methodology is elaborated in

Section 4, which includes an extension of a foundational approach to address the specific complexities of the case under consideration.

Section 5 details the validation of the proposed methodology through an extensive experimental campaign, accompanied by a benchmark for comparative analysis. Lastly,

Section 6 consolidates the findings, outlines the objectives achieved, and provides recommendations for future research directions. The subsequent section delineates the structure of the proposed approach, following an overview of the principal insights drawn from the literature.

2. Literature review

A substantial body of literature exists on Cutting Stock Problems (CSPs), encompassing both 1D and 2D scenarios with constrained cutting patterns and diverse objective functions. The following references provide insightful perspectives on the field.

The linear programming approach proposed by [

4] and [

5] for one-object and one-stage CSPs is based on column generation, where the pricing problem is solved using dynamic programming. [

14] developed a combined column generation and branch-and-bound algorithm to obtain optimal integer solutions for binary CSPs. [

13] presents a nested decomposition approach for solving a three-stage two-dimensional (2D) CSP with orthogonal guillotine cuts. This method, aimed at minimizing waste and accommodating various industrial constraints, employs a recursive column-generation algorithm that provides lower bounds and feasible upper bounds, facilitating potential integration into branch-and-bound for optimal solutions. [

12] solves the 1.5D assortment problem with multiple objectives using a genetic algorithm, generating cutting patterns with implicit enumeration. [

1] developed an accelerated column generation method by introducing dual-optimal inequalities, reducing the number of column generation iterations and run time. The enhanced heuristic algorithm in [

17] addresses 2D-CSPs with constrained and guillotine cutting and multiple stock objects. It is based on a multi-phase genetic algorithm, where the objective function is not the residual area but a modified trim loss equation.

Despite this, the most flexible approach in the literature is that proposed by [

18] and [

19], who developed a linear programming model based on the generation of columns for the multi-stage problem. The presence of multiple stages presents the challenge of generating intermediate objects. This challenge has been addressed through a revised separation problem for generating the rows of the constraint matrix, where the rows correspond to the items. However, their focus is typically on minimizing the number of patterns used in the first stage rather than the total trim loss.

[

8] and [

9] classify the 1D-TSCSP as a Column-Dependent-Rows (CDR) problem with no interactions. This class of problems is characterized by the presence of so-called linking constraints, which, in the context of CSPs, are associated with the rows corresponding to intermediate orders. These constraints are contained within the connecting matrices of the main constraint matrix. They outlined a simultaneous column-and-row generation algorithm based on three assumptions, which correctly price columns in the absence of certain linking constraints and allow for the generation of multiple intermediate orders at a time. In [

10], they developed a hybrid algorithm based on a branch-and-price approach, applying a second-level column generation to the row-generating subproblem for the unknown intermediate orders. Importantly, their objective is also to minimize the number of first stage patterns used, rather than minimizing the total trim loss. Additionally, they made a comparison with Zak’s approach, highlighting differences in terms of computational time and solution gap.

[

15] tackles a new variant of the cutting stock problem involving two-dimensional skiving and significant setup costs. They consider scenarios where output sheets are longer but narrower than the input coils, allowing the combination of two or more coils to satisfy sheet demands. To minimize both material and setup costs, they propose an integer programming formulation characterized by an exponential number of binary variables and column-dependent constraints. Their approach utilizes a Column-and-Row generation framework to solve the linear programming relaxation, involving a knapsack subproblem and a nonlinear integer programming subproblem for which they develop a decomposition-based exact solution method with pseudo-polynomial time complexity.

In [

11], the Generate-and-Solve (G&S) framework is implemented for the 1D-CSP, employing a recursive pattern generation procedure structured as a search tree. This tree represents all feasible cutting patterns, where the root node corresponds to the length of the large object, internal nodes represent the inclusion of specific item types, and leaf nodes indicate the cut loss. By limiting the tree’s height to the number of different item types and constraining the number of items per type to their respective demands, the method efficiently generates a reduced set of promising patterns. The G&S framework then utilizes an exact solver on these reduced instances, consistently obtaining quasi-optimal solutions across various instance sizes. This approach effectively balances computational efficiency and solution quality, and when integrated with Column Generation techniques, it has the potential to enhance convergence in branch-and-price algorithms, especially when Column Generation alone does not yield high-quality integer solutions.

In summary, while many studies focus on minimizing the number of patterns used in multistage CSPs, our work aligns with the objective of minimizing total trim loss at all stages, generalizing the approaches by [

18,

19], and [

10]. This objective is particularly relevant for both paper and plastic films industreis, where reducing material waste is critical. Our study aims to build upon these approaches to address the specific challenges of the 1.5D-TSCSP introduced earlier.

3. Problem formulation

The addressed problem pertains to a cutting process involving S stages. At each stage s, a set of final orders is generated. Each order is associated with a minimum demand for rolls of width and length . The objective is to determine, for each stage s, the set of cutting patterns and their corresponding quantities , such that the trim loss in width is greater than or equal to the minimum allowable . Each pattern is a vector consisting of components, where each component i indicates the number of times order i is produced in that cutting pattern. All orders with a positive entry have the same length . Additionally, we need to determine the intermediate orders k at each stage obtained through splitting and feeding the subsequent stages , specifying their widths within an interval and their lengths selected from a set of feasible length ratios. The objective is to minimize the total trim loss , where is the trim area, i.e., the product of the trim width and the pattern length . In addition, we assumed that the first stage always uses a single mill roll of fixed width W and unlimited supply, and that for each stage s, there is no initial stock for each intermediate order k; therefore, the total length produced must be greater than or equal to the length consumed by the subsequent stages. For simplicity, we also assumed the presence of final orders only at the last stage. Next, we will formulate the problem with only two stages and impose that the total quantity produced of each intermediate order is entirely consumed.

The problem stated will be formulated as a Cutting-Stock problem, which is well-known to be NP-Hard, where a sufficiently large inventory of a single fixed width mill rolls, which serve as input for the first cutting stage, are first split into intermediate stock rolls, and each of them is then slit to produce finished rolls, meeting the minimum demand across all orders. Due to technological constraints, it is not feasible to convert the entire width of the mill roll, resulting in trim loss, which constitutes the primary source of waste in the process. Trim loss is typically divided into two types: fixed and variable. The fixed component is unavoidable and cannot be eliminated, while the variable component depends on the quality of the optimization. In practical applications, treatments are applied to the produced rolls, making the minimization of intermediate orders secondary to the need to minimize trim loss, expressed in units of surface area. This surface area is the product of the pattern length and the trim width, contrasting with the formulation by [

18] and [

10], which minimizes the number of first-stage patterns used.

An extension of the set-covering formulation applied to multi-stage CSP is presented here. A cost coefficient is associated with each cutting pattern, and an integer decision variable represents how many times that pattern is used.

3.1. Multi-Stage Master Problem

Let be the global cost vector, where S is the number of stages. Each for is the cost vector specific to the s-th stage, with components, where is the number of cutting patterns at the s-th stage.

Similarly, let be the global minimum demand vector. Each for is the minimum demand vector specific to the s-th stage, with components, where is the number of orders at the s-th stage. For the intermediate orders, the demand is set to zero, representing that no minimum quantity needs to be produced beyond consumption.

The global decision variable is the vector , where each indicates how many times each pattern at stage s is used in the solution.

The model in matrix form is shown below:

Here,

is the total number of cutting patterns across all stages. The constraint matrix

A has a special block structure, reflecting the relationships between stages and patterns. Each element

is a sub-matrix of dimensions

, with

.

The matrices represent the interactions between orders at stage and patterns at stage . Specifically:

The diagonal blocks for are the canonical cutting stock matrices for the s-th stage. Each column in corresponds to a cutting pattern at stage s, and each row corresponds to an order at that stage. The element indicates the quantity of order i produced by pattern j.

The off-diagonal blocks for represent the consumption of intermediate stock rolls between stages. These blocks are called connection matrices. For , captures the consumption of stock rolls from stage by patterns at stage .

Each column in a connection matrix represents a pattern at stage , and each element indicates the consumption of an intermediate roll from order i at stage by pattern j at stage . This consumption is quantified by , where is the fraction of the intermediate roll consumed by one use of pattern j. For example, if the intermediate roll from order i at stage 1 has a length of meters, and a pattern j at stage 2 produces rolls of length meters, then the consumption is . This means that four uses of pattern j are necessary to consume an entire intermediate roll from order i. We define the length ratio as . This ratio indicates how many times a pattern at the downstream stage can be applied to fully consume an intermediate roll from the upstream stage.

Without loss of generality, we can set when , because conversion flows from downstream to upstream are not practical and are not permitted due to possible treatments applied to the items. This block structure of the constraint matrix allows us to capture the material flow and dependencies between stages in the multi-stage CSP. The decision variables and the constraints ensure that customer demands are met, intermediate stock roll consumption is properly accounted for, and the overall trim loss is minimized through the objective function . This approach also allows us to incorporate the possibility of having items of different lengths within the same pattern, accommodating the complexities of the 1.5D-TSCSP, described in the next section.

3.2. Two-Stage Master Problem

The previous model represents the most general case, which can be easily adapted to the two-stage version. In this case, the master problem formulated using the matrix form becomes as follows:

In this formulation, note that the demand vector for the first stage, , is set to zero. This is because the intermediate orders produced at the first stage must be entirely consumed at the second stage; partial consumption would result in significant waste and logistical issues due to leftovers. Therefore, we enforce a set partitioning constraint at the first stage (7) to ensure that all intermediate stock produced is fully utilized, while at the second stage, we use a set covering constraint (8) to meet the customer demands for finished rolls. A schedule with the least number of different intermediate sizes is most desirable, as it minimizes both complexity and waste in the production process.

The difficulty in solving this model derives from the multitude of unknown cutting patterns and intermediate stock orders, corresponding to the columns and rows of A matrix respectively. Generating the entire matrix takes is impractical because the number of cutting patterns grows exponentially with the number of orders.

4. Solution approach

In CSPs, as the number of orders increases, the cutting patterns—and thus the number of variables—grow exponentially. This exponential growth poses significant computational challenges, making it impractical to generate all possible cutting patterns (columns of the coefficient matrix A) in advance, especially for large-scale problems. For this reason, we initiate the model with a short and restricted coefficient matrix A consisting of only a minimal number of columns necessary to ensure feasibility. We then iteratively generate additional columns (cutting patterns) and rows (intermediate orders) only when they have the potential to reduce the objective function value.

Initially, is constructed as an identity matric, where each column corresponds to a first-stage cutting pattern that produces exactly one unit of an intermediate order. This means that each cutting pattern at the first stage cuts exactly one intermediate roll, and is a diagonal matrix with ones on the diagonal. For , we create a pattern for each second-stage order that is compatible with the existing intermediate orders based on admissible length ratios. Specifically, for each intermediate roll and each second-stage order where the length ratio is admissible and integer, we create a second-stage cutting pattern that produces exactly one unit of order using intermediate roll .

The coefficient matrix is initialized with an intermediate order for each feasible first stage length with witdh equal to the maximum value. For this reason, the problem is referred to as short, indicating that the number of rows is less than the total possible. Just as columns (cutting patterns) are dynamically generated when needed, the rows—representing the intermediate orders—are also generated on demand. This process occurs concurrently with the creation of a first-stage cutting pattern that includes the new intermediate order with a non-zero coefficient and a second-stage cutting pattern that consumes units of this intermediate order. The objective is to reduce the value of the objective function, i.e. the total trim loss measured as surface, by introducing these new rows and associated cutting patterns when they have the potential to improve the solution.

4.1. Generate-and-Solve Algorithm

In this section, we present the implementation of the Generate-and-Solve (G&S) framework applied to the 1.5D-TSCSP. Our approach adapts the traditional G&S method, originally designed for one-dimensional CSPs [

11], to address the additional complexities introduced by the multi-dimensional and multi-stage nature of the problem, such as he rolls produced in the first stage that serve as input for the second stage.

Our algorithm operates by alternating between two primary phases:

Pattern Generation Iterations: In this phase, the algorithm focuses on generating new cutting patterns for both the first and second stages without altering the set of intermediate orders. The goal is to improve the current solution by exploring new combinations of existing orders.

Order Generation Iterations: When pattern generation no longer yields significant improvements, the algorithm transitions to this phase, where new intermediate orders are introduced. By expanding the set of intermediate orders, we enlarge the solution space, allowing for potentially better solutions that were not possible with the previous set of orders.

At each iteration, a Relaxed Short and Restricted Master Problem (RSRMP) is solved, that includes only a limited set of cutting patterns and intermediate orders, making it computationally feasible to solve repeatedly within the iterative framework. The algorithm initializes with an initial set of existing first-stage and second-stage patterns and intermediate orders. Each cutting pattern has an associated countdown integer value, which determines its lifespan in the algorithm based on recent usage. Patterns that are not utilized in recent iterations are gradually phased out through the aging mechanism to maintain computational efficiency and prevent the model from becoming too large.

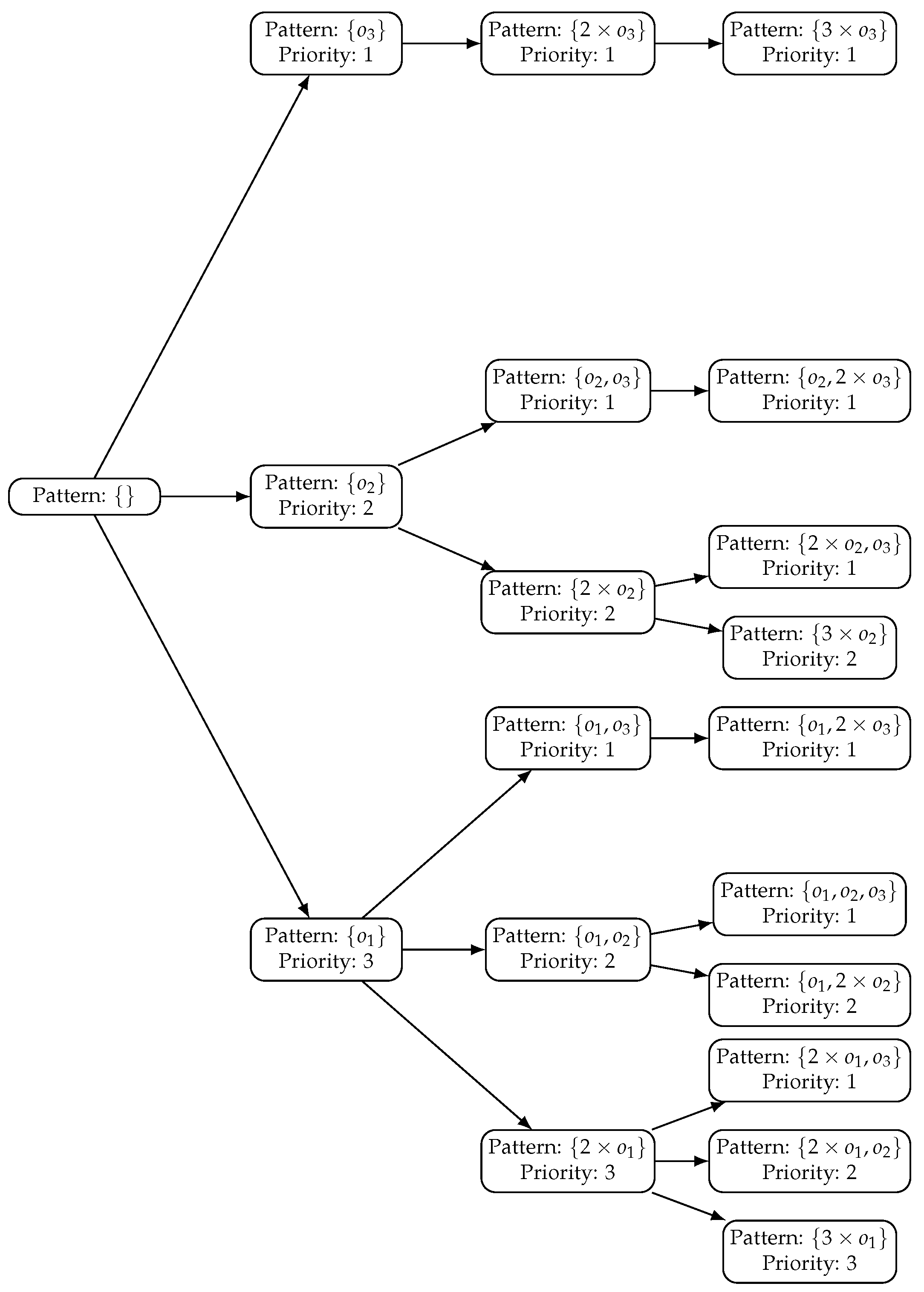

Dedicated pattern generators for the first and second stages are responsible for creating new patterns when needed. These pattern generators utilize a lexicographic search tree to systematically explore potential patterns. A priority queue manages the exploration of the pattern generation trees, prioritizing nodes based on their potential to improve the solution. Each node in the search tree represents a partial pattern, containing information about the current used width, the level in the tree, the remaining width, the set of remaining orders that can be added to the pattern, determined by lexicographic ordering and feasibility based on residual width. Nodes are prioritized based on trim loss, ensuring a depth-first exploration. When generating child nodes, feasible orders are added to the current pattern, respecting width constraints, one unit at a time. The remaining width is updated accordingly, and the set of remaining orders is adjusted to consider only orders that have not yet been included and fit within the residual width.

In the order generation iterations, the algorithm introduces new intermediate orders to expand the solution space. This is a significant difference from the standard G&S method, which typically does not alter the set of items (orders) but focuses on pattern generation. The algorithm identifies inefficient second-stage patterns that contribute most to trim loss and negatively impact the objective function. Based on these patterns, new intermediate orders are created with dimensions designed to reduce waste. The pattern generators are then updated to include these new intermediate orders, allowing the generation of new patterns that incorporate them. When a new intermediate order is introduced, it is added to the leftmost branch of the search tree with maximum priority to ensure it is explored promptly in subsequent iterations. The pseudocode for the Generate-and-Solve algorithm is presented in Algorithm 1

|

Algorithm 1 Generate-and-Solve Generation Algorithm

|

- 1:

Construct initial RSRMP - 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

while True do - 8:

Solve RSRMP - 9:

Update CurrentObj - 10:

- 11:

if PatternGenIter then - 12:

if then - 13:

- 14:

if then - 15:

- 16:

end if - 17:

else - 18:

- 19:

end if - 20:

else - 21:

if then - 22:

- 23:

if then - 24:

break - 25:

end if - 26:

else - 27:

- 28:

- 29:

- 30:

end if - 31:

end if - 32:

if PatternGenIter then - 33:

Update pattern usage counters - 34:

Remove obsolete column(s) from RSRMP - 35:

Remove rows with no linking constraints from RSRMP - 36:

Generate and Add column(s) to RSRMP - 37:

else - 38:

Select worst second-stage pattern - 39:

Generate and Add new row to RSRMP - 40:

Generate and Add column(s) to RSRMP - 41:

end if - 42:

end while |

The algorithm employs several parameters to control its execution:

PatternGenIter: A boolean flag indicating whether the current iteration is a pattern generation iteration (True) or an order generation iteration (False).

PatternGenAttempts and OrderGenAttempts: Counters for the remaining attempts in each phase before switching or terminating. These are initialized to a maximum value (MaxAttempts).

UpdateLimit: A predefined threshold for considering an iteration successful, based on the relative improvement in the objective function.

At each iteration, after solving the RSRMP, the algorithm evaluates the improvement in the objective value. If the improvement exceeds UpdateLimit, the iteration is considered successful, and the corresponding attempt counter is reset. If not, the attempt counter is decremented. When the attempt counter reaches zero, the algorithm switches phases or terminates if both counters reach zero.

To manage the size of the RSRMP and maintain computational efficiency, the countdown value for patterns used in the current solution is increased by 1, reinforcicng their relevance in future iterations, instead for the unused patterns is decremented by 1. Patterns with a countdown valueof 0 are removed from the coefficients matrix A. Orders that no longer have associated patterns are also removed.

By iteratively refining the set of patterns and intermediate orders considered in the RSRMP, the algorithm converges to high-quality solutions without the need to enumerate all possible combinations upfront. The ability to dynamically introduce new intermediate orders allows the algorithm to escape local optima and explore a broader solution space than methods that only generate patterns.

The advantages of this approach are manifold. Firstly, by restricting the number of patterns and orders in each iteration and by employing a countdown mechanism to remove unused patterns, the algorithm mitigates the combinatorial explosion typically associated with cutting stock problems. Secondly, the priority-based exploration ensures that computational resources are allocated efficiently, focusing on patterns that are most likely to yield improvements. Lastly, the flexibility to introduce new intermediate orders enables the algorithm to navigate the solution space more effectively, overcoming local optima and enhancing the overall solution quality.

Figure 2 illustrates the lexicographic search tree used for pattern generation, incorporating priorities to guide the search towards the most promising patterns.

4.2. Column-and-Row Generation Algorithm

There is a rich body of literature available on cutting-stock problems, dealing with both One-dimensional and Two-dimensional cases, where Column Generation is employed. It starts with the Relaxed and Restricted Master Problem (RRMP), where each diagonal block is initialized with a small subset of cutting patterns and the decision variables are real values. The idea is to generate the least number of patterns necessary for the optimal solution. This approach is based on the iterative resolution of the Relaxed and Restricted Master Problem (RRMP) and an auxiliary model called the Pricing Sub-Problem (PSP), which has the form of a knapsack problem. The first dynamic approach for classic CSP was proposed by [

4] and [

5] and can be extended to the case of two stages when the intermediate stock rolls are already known. In that case, a column generation algorithm that comprises two auxiliary models, each related to a specific cutting stage, is sufficient.

If intermediate rolls are unknown in advance, we face a more complicated situation. We are free to pick any suitable intermediate width z from a given range of intermediate roll widths . Since every intermediate roll and finished roll is associated with a row of the LP matrix, generating all the feasible intermediate orders whose widths fall within that interval would cause the problem to expand in both directions: columns and rows. Hence, the application of the column generation algorithm falls short since it would not take into account the dual variables of the missing intermediate rolls, and the potentially huge number of intermediate rolls precludes generating all the possible cutting patterns beforehand.

[

18,

19] and [

10] proposed a Row-and-Column Generation (R&CG) algorithm for the One-dimensional Two-Stage Cutting Stock Problem (1D-TSCSP), which starts from a Relaxed, Short and Restricted Master Problem (RSRMP)—an initial model that limits not only the number of decision variables (columns) but also the number of constraints (rows)— and is based on three types of auxiliary subproblems. Specifically, the first auxiliary subproblem generates the cutting patterns for the first stage (columns of

), the second generates the cutting patterns for the second stage (columns of

), and the third simultaneously generates new intermediate rolls and their associated cutting patterns. This third subproblem involves adding new rows (representing intermediate orders) to the matrices

and

, and new columns to

,

, and

. It requires generating at least one pattern at the first stage that includes the new intermediate orders and a pattern at the second stage that consumes them.

|

Algorithm 2 Column-and-Row-Generation Algorithm |

- 1:

FLAG ← 1 - 2:

Construct initial RSRMP - 3:

Solve RSRMP - 4:

while True do ▹ first-stage-pricing - 5:

for in First Stage Lengths do - 6:

Solve 1S-CG-PSP - 7:

end for - 8:

if A negatively priced column exists then - 9:

FLAG ← 1 - 10:

Add column(s) to RSRMP - 11:

Solve RSRMP - 12:

else - 13:

FLAG ← 0 - 14:

while True do ▹ second-stage-pricing - 15:

for intermediate order k in Intermediate Orders do - 16:

for in Second Stage Feasible Lengths do - 17:

Solve 2S-CG-PSP - 18:

end for - 19:

end for - 20:

if A negatively priced column exists then - 21:

FLAG ← 1 - 22:

Add column(s) to RSRMP - 23:

Solve RSRMP - 24:

else - 25:

break - 26:

end if - 27:

end while - 28:

if FLAG = 0 then - 29:

while True do ▹ row-generating - 30:

for in First Stage Lengths do - 31:

for in Second Stage Feasible Lengths do - 32:

for in do - 33:

Solve RCG-PSP - 34:

end for - 35:

end for - 36:

end for - 37:

if A negatively priced column exists then - 38:

FLAG ← 1 - 39:

Add column(s)/row(s) to RSRMP - 40:

Solve RSRMP - 41:

else - 42:

break - 43:

end if - 44:

end while - 45:

if FLAG = 0 then - 46:

break - 47:

end if - 48:

else - 49:

continue - 50:

end if - 51:

end if - 52:

end while |

In this section, we present an adapted version of the Column-and-Row generation algorithm proposed by [

8] tailored to the One-and-Half Dimensional problem.

At each iteration, we solve the dual of the restricted problem. The dual problem is advantageous in CSPs because it typically has fewer variables than the primal problem—the number of dual variables corresponds to the number of orders, which is a fixed quantity, where

and

are the dual variables associated with the first and second stage contraints, respectively.

Note that is unrestricted in sign due to the equality constraints in the first stage, and corresponds to the inequality constraints in the second stage. Observe that since each row of the matrix has only a single non-zero component, the constraint corresponding to each second-stage pattern j simplifies to , where k is the index of the intermediate order from which pattern j is produced and is the inverse of the length ratio.

Let for and for be the optimal dual prices for first and second stage respectively. To determine whether there exists a constraint, i.e. cutting pattern, not present in the restricted problem that is violated by the current solution, we need to solve a maximization problem known as Pricing Sub Problem (PSP) for each stage and subset of compatible orders.

The algorithm involves threes types of Pricing Sub Problems (PSPs):

Fist-Stage Pricing Sub-Problem (1S-CG-PSP): searches for a new column of that have negative reduced costs with respect to the current set of constraints in the Relaxed Restricted Master Problem (RSRMP).

Second-Stage Pricing Sub-Problem (2S-CG-PSP): searches for a new column of that have negative reduced costs with respect to the current set of constraints in the Relaxed Restricted Master Problem (RSRMP).

Row-Generating Pricing Sub-Problem (RCG-PSP): searches for new intermediate orders (rows) and their associated columns and for , and .

The algorithm begins by repeatedly solving 1S-CG-PSP. Once no additional first stage columns can be generated, 2S-CG-PSP is solved to identify new second stage columns folowing a similar iterative approach. If neither the CG-PSPs yields new columns given the current intermediate orders, RCG-PSP is employed. This subproblem potentially introduces both new rows and related ccolumns into the RSRMP. After solving a Pricing Sub Problem with at least a negatively priced column, the algorithm returns to the 1S-CG-PSP because the dual variables may have changed due to the addition of new constraints and variables. The algorithm terminates when in the same iteration all PSPs do not produce any negatively priced columns—this is indicated when the FLAG variable remains zero.

Since in this paper we have chosen to address Case 3 as presented in the introduction, it is necessary to partition the orders at each stage into multiple Pricing Sub Problems. Each PSP consists of orders that share the same length within the same stage and have the same length ratio between different stages. This partitioning ensures compatibility among the orders within each PSP and allows us to effectively apply the Column-and-Row generation algorithm.

4.2.1. First Stage Column-Generating PSP

The aim of the first-stage Column-Generation Pricing Sub Problem (1S-CG-PSP) is to find a negatively priced column

for the first stage. For each distinct first-stage length

, we execute the following optimization problem:

subject to

Here,

is the decision variable representing the quantity of the

i-th order of the first stage with length

and width

included in the cutting pattern.

is the optimal dual variable obtained from the current RSRMP.

is the width of the input roll at the firs stage,

the minimum allowable trim loss and

represents the actual trim loss in the cutting pattern. Equation (

17) tries to maximize the reduced cost of a potential new first-stage cutting pattern, where the cost associated is calculated as the product of the trim loss and the pattern length.

If the optimal value is strictly positive, a new first-stage cutting pattern is generated, defined as:

. The generated column

is then added to the coefficient matrix

A as follows. By adding the new column we expand also the cost vector

and the

with a new decision variable for the new pattern.

4.2.2. Second Stage Column-Generating PSP

The aim of the second-stage Column-Generation Pricing Sub Problem (2S-CG-PSP) is to find a negatively priced column

for the second stage. For each intermediate order

k and for each distinct second-stage length

, we execute the following optimization problem:

subject to

Here, is the decision variable representing the quantity of the i-th order of the second stage with length and width included in the cutting pattern. is the optimal dual variable obtained from the current RSRDP. is the width of the intermediate order k, the minimum allowable trim loss and represents the actual trim loss in the cutting pattern.

If the optimal value is greater than

, a new second-stage cutting pattern is generated, defined as:

. The generated column

is then added to the coefficient matrix

A as follows. By adding the new column we expand also the cost vector

and the

with a new decision variable for the new pattern.

Here, is a column vector added to , representing the linking coefficients due to the consumption of the intermediate order k.

4.2.3. Row-Generating PSP

The Row-Generating Pricing Sub-Problem (RCG-PSP) aims to identify new intermediate rolls as new rows and their associated cutting patterns as new columns that, when added to the RSRMP, expand the feasible solution space and enhance the likelihood of achieving optimality.

In the context of the 1.5D-TSCSP, the Row-Generating PSP is particularly challenging due to four main reasons:

The lengths of the intermediate rolls are unknown as their widths.

The dual variables associated with these new intermediate rolls are not known in advance, except that they are non-negative in any feasible dual solution. These dual variables must be accurately estimated to effectively incorporate them into the solution of the row-generating PSP effectively.

Multiple second-stage cutting patterns can be produced from a single intermediate roll.

Multiple intermediate rolls may need to be generated simultaneously.

To address the first challenge, we resolve it by considering only one first-stage length at a time. Since we have assumed we are tackling CSPs that fall under Case 3 (as presented in the introduction), all intermediate orders generated in the same first-stage pattern must have the same length . However, it is not necessary that patterns cut from different intermediate rolls have the same length.

Regarding the estimation of the dual variables for the intermediate orders, we can utilize the complementary slackness condition from linear programming duality theory. If we are generating second-stage patterns that reduce the total trim loss—that is, the objective function value of the RSRMP—then the corresponding dual variable for the intermediate roll will take a strictly positive value. This implies that the corresponding dual constraint is tight, i.e. satisfied with equality. Consider an intermediate roll k and a second-stage cutting pattern j. The corresponding dual constraint from the dual problem is: . If we impose that the constraint is tight and set , where represents the trim loss for pattern j, and , where is the length of the second-stage pattern j, we can rearrange the dual constraint to solve for : .

This consideration is closely related to the third challenge. Since the dual variables for are positive, as they are associated with demand constraints in the second stage, and the coefficients are non-negative, representing quantities of orders in patterns, each term is positive. Therefore, to generate a new intermediate roll with a negatively priced column, it suffices to consider the second-stage pattern that maximizes . This means that is sufficient to consider a single second-stage cutting pattern for each new intermediate order.

The Row-Generating PSP is formulated for each combination of first-stage length

and second-stage length

, such that their ratio is feasible.

subject to

where

subject to

Here, is the decision variable corresponding to the number of times the new intermediate order k is included in the first-stage cutting pattern and its width. and represent the trim losses at the first and second stages.

The new columns and rows generated are incorporated into the RSRMP’s coefficient matrix A as follows:

is the new column corresponding to the first-stage cutting pattern.

is the new column corresponding to the second-stage cutting pattern produced from intermediate order k.

is included to account for the number of times the intermediate order k is used in the newly created first-stage cutting pattern.

s the non-zero term placed at the position corresponding to the intermediate order k in the linking constraint row.

Regarding the fourth challenge, although multiple intermediate rolls may need to be generated simultaneously, we can simplify the problem by generating one intermediate roll at a time. This approach, inspired by Zak’s simplification [

18], reduces computational complexity and has been shown to be effective in practice [

10].

By focusing on generating a single intermediate roll per iteration, we can formulate a unified mathematical model. However, this model remains challenging to solve because it would take the form of a nonlinear integer knapsack problem due to the product terms involving

z and

and

and

. As suggested in the literature [

19], we can further simplify the problem by fixing the value of

. By iterating over possible integer values of

within a feasible range, we transform the nonlinear knapsack problem into several linear knapsack problems, which are easier to solve. This approach significantly reduces computational complexity and allows for an efficient exploration of potential intermediate rolls. The simplified row-generating pricing subproblem is formulated as follows:

subject to

By focusing on a single intermediate roll, the update of the coefficient matrix

A simplifies. The new intermediate roll and its associated cutting patterns are incorporated into the RSRMP’s coefficient matrix as follows:

For the new intermediate order generated, we add a value of zero to the demand vector: . This ensures that the quantity consumed by the second-stage patterns does not exceed the quantity produced by the first-stage patterns.

5. Computational results

In this section, we present the computational experiments conducted to evaluate and compare the performance of the proposed Generate-and-Solve (G&S) algorithm and the Column-and-Row Generation (R&CG) algorithm for 1.5D-TSCSP. The experiments are designed to assess the algorithms on a diverse range of randomly generated instances that reflect various practical scenarios encountered in industry.

5.1. Experiments setting

We generated test instances based on two types of randomly generated datasets: I1 and I2. Each instance type comprises ten subtypes, corresponding to varying numbers of second-stage orders (), ranging from 10 to 50. We assumed for simplicity that there are no final orders at the first stage. For each subtype, ten instances were generated, resulting in a total of 100 instances.

I1 is based on the test problems used by [

10]; these instances feature single length ratios and a single length for finished rolls. In contrast, I2 includes multiple lengths for finished rolls and multiple length ratios and is designed to mimic practical industrial cases. Since I2 instances enforce a minimum trim loss at the first stage, indirectly they reduce the number of intermediate orders produced, aligning the model with realistic operational constraints.

The parameters utilized for generating these instances are presented in

Table 1. Finished roll widths and order demands were generated using integer uniform distributions over a specified range of integer values (UR), while lengths were selected from specified discrete sets with uniform probability (US). The length ratios represent the admissible ratios between the lengths of intermediate rolls and finished rolls, ensuring compatibility during the cutting process. The minimum trims at each stage are determined by practical considerations, including machine limitations and quality requirements.

All computational experiments were conducted on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i7-6700 CPU running at 3.40 GHz and 16 GB of RAM. The algorithms were implemented in C# using the .NET 8 framework. We utilized IBM ILOG CPLEX Optimizer version 22.1.1, along with CPLEX Concert Technology, to solve the linear and integer programming models.

For both the G&S and R&CG algorithms, an execution time limit of 600 seconds was imposed on the generation of patterns and intermediate orders. A separate time limit of 600 seconds was imposed for resolving the SRMP model. The best solution discovered up to that point was recorded.

5.2. Discussion

The performance of the algorithms was evaluated based on several metrics, including the number of patterns generated at the initial and second stages (

and

), the average number of intermediate orders (

), the average percentage difference in the objective value (

% Int. Obj. Value), and the average difference in the total computation time (

Tot. time).

Table 2 presents the computational results for instances I1 and I2.

For smaller instances of I1, which feature single length ratios and single lengths for finished rolls, both algorithms performed adequately. The G&S algorithm, however, tended to generate a significantly larger number of second-stage patterns () compared to the R&CG algorithm, leading to increased computational effort. Despite this, the G&S algorithm achieved comparable integer objective values, as indicated by the small average differences in objective value (% Int. Obj. Value). The R&CG algorithm, with its fewer generated patterns, demonstrated greater computational efficiency, requiring less total computation time in most cases.

In bigger instances of I1 and in the more complex instances of I2, which incorporate multiple length ratios, multiple lengths for finished rolls, and enforce a minimum trim loss at the first stage, the performance gap between the two algorithms became more pronounced. The G&S algorithm continued to generate a substantially higher number of second-stage patterns, which significantly increased the computational time. For example, in instances I2 with , the G&S algorithm generated an average of 815,093 second-stage patterns, whereas the R&CG algorithm generated only 644 patterns. This difference resulted in the G&S algorithm having a much longer computation time, with an average decrease in total time of -595.6 seconds compared to the R&CG algorithm.

Moreover, the G&S algorithm exhibited worse performance in terms of solution quality for these complex instances. The average difference in integer objective value (% Int. Obj. Value) was negative, indicating that the R&CG algorithm found better solutions with lower trim losses.

These results suggest that while the G&S algorithm is effective for simpler instances, it struggles with the increased complexity of industrial cases represented by I2. In contrast, the R&CG algorithm demonstrates robustness and efficiency across both simple and complex instances. The ability of the R&CG algorithm to generate fewer patterns while achieving better or comparable objective values highlights its suitability for practical applications of the 1.5D-TSCSP in industrial settings where computational resources and time are critical factors.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we extended the Generate-and-Solve algorithm and the Column-and-Row Generation algorithm, both of which are available in the literature for solving one-dimensional constraint satisfaction problems, to solve the One-and-Half-Dimensional Two-Stage Cutting Stock problem. We tested these algorithms on randomly generated cases of increasing complexity. The computational results demonstrate that the R&CG algorithm generally outperforms the G&S algorithm in terms of solution quality and computational efficiency, particularly in complex instances involving multiple length ratios and practical constraints such as minimum trim requirements that are typical of plastic films and paper industries.

Future research could focus on enhancing both approaches. G&S algorithm can be improved incorporating the ratio between dual value and width for each order on priority calculation. Online machine learning techniques might be employed to make the lexicographic search tree for pattern generation more intelligent. Row-Generating PSP in R&CG algorithm can be generalized, as suggested in previous studies [

10], enabling it to generate multiple intermediate orders simultaneously. Moreover, the problem can be extended, allowing patterns to contain at most two different lengths—enabled by duplex slitter rewinders, and including final orders at the first stage with minimum demand constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.; methodology, P.C. and P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.; writing—review and editing, A.G. and P.C.; supervision, P.C.; project administration, A.G.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Regione Puglia under the project SO.VET. S.R.L. — CUP: B25H24000520009 and by Ministero delle Imprese e del Made in Italy, Accordo Innovazione DM 31/12/2021 (Primo Bando), under the project MS Packaging for Water – (MSP4Water) — CUP: B89J23001430005.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alves, C.; Valério de Carvalho, J. M. Accelerating column generation for variable sized bin-packing problems. European Journal of Operational Research 2007, 183, 1333–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyckhoff, H.; Kruse, H. J.; Abel, D.; Gal, T. Trim loss and related problems. Omega 1985, 44, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyckhoff, H. A typology of cutting and packing problems. European Journal of Operational Research 1990, 44, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, P. C.; Gomory, R. E. A Linear Programming Approach to the Cutting-Stock Problem. Operations Research 1961, 9, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, P. C.; Gomory, R. E. A Linear Programming Approach to the Cutting Stock Problem-Part II. Operations Research 1963, 11, 863–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haessler, R. W. A Procedure for Solving the 1.5-Dimensional Coil Slitting Problem. A I I E Transactions 1978, 10, 700–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallrath, J.; Rebennack, S.; Kusche, R. Solving real-world cutting stock-problems in the paper industry: Mathematical approaches, experience and challenges. European Journal of Operational Research 2014, 238, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muter, İ.; Birbil, Ş. İ.; Bülbül, K. Simultaneous column-and-row generation for large-scale linear programs with column-dependent-rows. Mathematical Programming 2013, 10, 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muter, İ.; Birbil, Ş. İ.; Bülbül, K. Benders decomposition and column-and-row generation for solving large-scale linear programs with column-dependent-rows. European Journal of Operational Research 2018, 264, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muter, İ.; Sezer, Z. Algorithms for the one-dimensional two-stage cutting stock problem. European Journal of Operational Research 2018, 271, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá Santos, J.V.; Nepomuceno, N. Computational Performance Evaluation of Column Generation and Generate-and-Solve Techniques for the One-Dimensional Cutting Stock Problem. Algorithms 2022, 15, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraç, T.; Özdemir, M. S. A Genetic Algorithm for 1,5 Dimensional Assortment Problems with Multiple Objectives. Developments in Applied Artificial Intelligence: 16th International Conference on Industrial and Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Expert Systems, IEA/AIE 2003 Loughborough, UK, June 23–26, 2003 Proceedings; Publisher: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; pp. 41–51.

- Vanderbeck, F. A Nested Decomposition Approach to a Three-Stage, Two-Dimensional Cutting-Stock Problem. Management Science 2001, 47, 735–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, P. H.; Barnhart, C.; Johnson, E. L.; Nemhauser, G. L. Solving binary cutting stock problems by column generation and branch-and-bound. Computational Optimization and Applications 1994, 3, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiao, F.; Zhou, L.; Liang, Z. Two-dimensional skiving and cutting stock problem with setup cost based on column-and-row generation. European Journal of Operational Research 2020, 286, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wäscher, G.; Haußner, H.; Schumann, H. An improved typology of cutting and packing problems. European Journal of Operational Research 2007, 183, 1109–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.Y.; Yang, J.C.; Lai, Y.L. Applying an Enhanced Heuristic Algorithm to a Constrained Two-Dimensional Cutting Stock Problem. Applied Mathematics and Information Sciences 2014, 9, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, E.J. Row and column generation technique for a multistage cuttingstock problem. Computers and Operations Research 2002, 29, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, E.J. Modeling multistage cutting stock problems. European Journal of Operational Research 2002, 141, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).