1. Introduction

Lung cancer is a significant global health challenge, ranking as the second most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [

1]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 estimates, there were approximately 2.2 million new lung cancer cases, accounting for 11.4% of all cancer cases, and about 1.8 million deaths, representing 18% of all cancer deaths [

2]. The disease's burden is exacerbated by persistent risk factors such as smoking, air pollution, and occupational exposures, which continue to drive the incidence and mortality rates of lung cancer upward [

3]. This underscores the urgent need for improved early detection and diagnostic solutions to mitigate its impact on healthcare systems and patient survival.

Chest X-rays (CXR) have long been a cornerstone of lung cancer screening due to their affordability and widespread availability, particularly in low-resource settings [

4]. However, their efficacy is limited by several intrinsic challenges. The two-dimensional nature of CXR imaging often obscures small nodules and overlapping structures, resulting in missed detections. Studies have shown that CXR fails to identify lung cancer in approximately 17.7% of patients within the year before diagnosis [

5]. Additionally, certain anatomical features, such as nodules located behind the heart or overlapping with bone structures, frequently escape detection, while benign features like nipple shadows are often misinterpreted as abnormalities

Low-Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) has emerged as a more accurate alternative, with its three-dimensional imaging capabilities enabling better identification of small and overlapping nodules [

6]. Large-scale trials, such as the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), have demonstrated a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality with LDCT [

7]. However, LDCT's high costs and radiation exposure make it an impractical solution for widespread implementation, particularly in low-income regions.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning present new opportunities to address these challenges. Computer-Aided Detection (CAD) systems, powered by Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have shown promise in enhancing the diagnostic capabilities of CXR. These systems can automate abnormality detection and reduce reliance on human expertise, all while operating at a fraction of the computational and financial cost of LDCT. However, existing CAD models often employ computationally intensive architectures, limiting their practicality in resource-constrained environments.

We aim to bridge this gap by exploring lightweight CNN architectures, specifically YOLOv2 [

8] and YOLOv8 [

9], to develop a cost-effective and efficient CAD system. The main contributions of this study are as follows: (1) proposing a cost-effective and efficient CAD system framework focused on improving the accuracy of abnormal nodule detection; (2) comparing the performance of YOLOv2 and YOLOv8 under different conditions, with particular attention to overlapping nodules; and (3) providing practical recommendations for model improvement to facilitate clinical applications in resource-constrained environments. The findings of this study are expected to enhance the efficiency of lung cancer screening and lay the groundwork for further optimization of medical imaging analysis systems.

By leveraging advancements in lightweight neural networks, this research aspires to make lung cancer screening more accurate, accessible, and applicable in diverse clinical settings, ultimately improving patient outcomes and supporting early detection effort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

We utilized a dataset comprising 112,120 chest X-ray (CXR) images collected from 30,805 patients. These images were labeled with various pathologies, including pneumonia, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, pulmonary fibrosis, aortic enlargement, and others. The data were partially sourced from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Vietnamese medical centers. To ensure compliance with data privacy regulations, all patient-identifiable information was removed during preprocessing.

While the dataset included a broad spectrum of labeled pathologies, this study focused on detecting pulmonary nodules, which are critical for early lung cancer detection. To ensure the dataset aligns with the study’s goals, certain pathologies less relevant to nodule detection were excluded from the analysis. These excluded pathologies include pneumonia, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, pulmonary fibrosis, aortic enlargement, atelectasis, calcification, cardiomegaly, consolidation, interstitial lung disease (ILD), infiltration, lung opacity, mass, pleural thickening, and other non-specific lesions. The removal of these pathologies ensures that the dataset is tailored to support accurate and efficient pulmonary nodule detection.

Preprocessing involved resizing all images to 512 × 512 pixels and converting them to grayscale for consistency. The dataset was divided into three subsets: 400 images for training, 167 for validation, and 100 for testing. Regions of interest (ROIs) containing pulmonary nodules were manually annotated with bounding boxes, and these annotations were performed by three experienced, licensed radiologists from Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital. This careful curation and validation process ensured high-quality ground truth data and provided a robust foundation for model training and evaluation.

2.2. Model Architecture

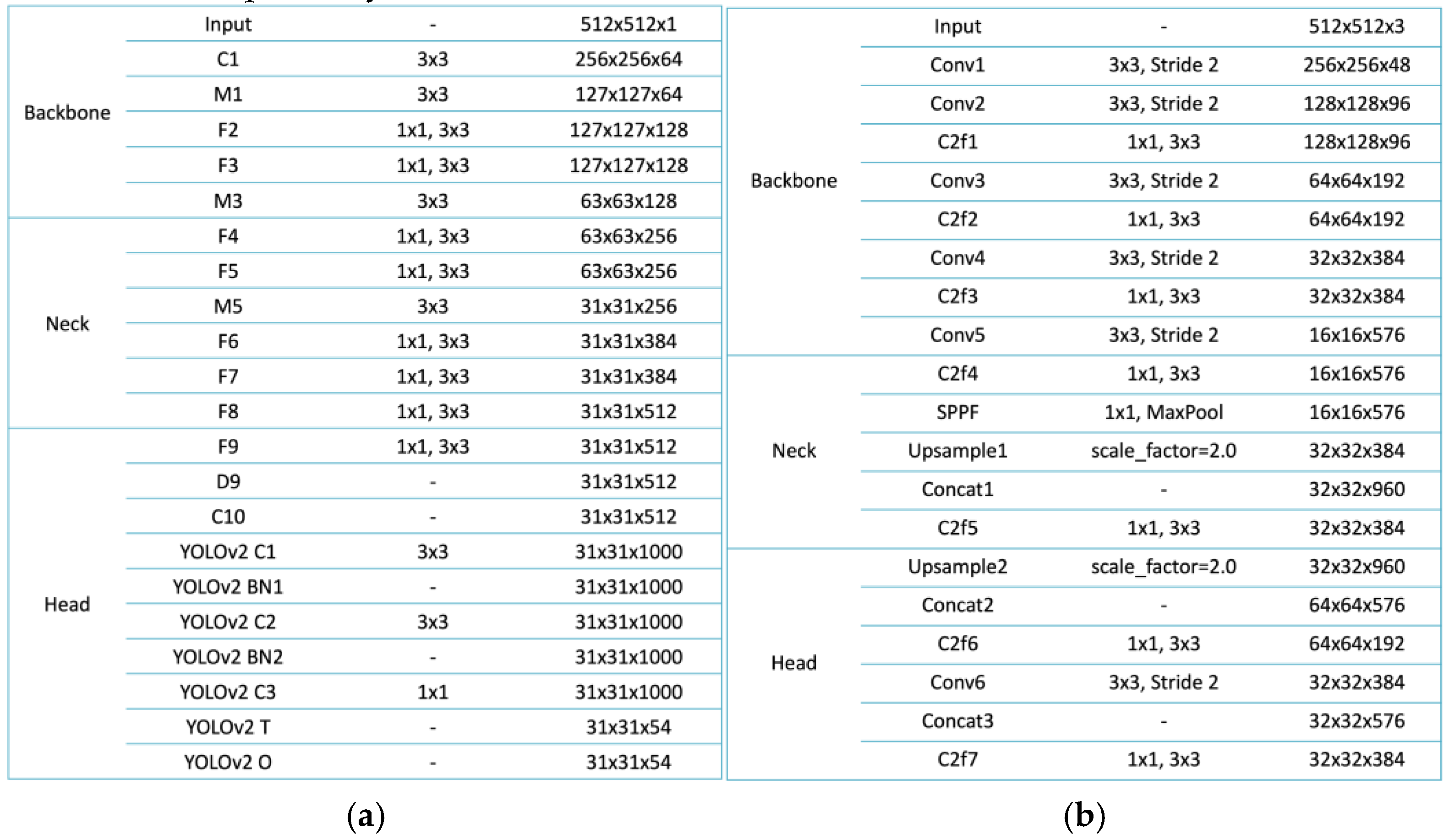

The architectures of YOLOv2 and YOLOv8 were employed in this study to detect pulmonary nodules in chest X-rays, with each model offering distinct advantages suited for medical imaging applications. YOLOv2, a lightweight model, is built upon the Darknet-19 backbone, which efficiently extracts low-level features through a series of convolutional layers [

10]. The model employs anchor boxes to enable multi-scale object detection, effectively identifying nodules of varying sizes. Its design is divided into three main sections: the Backbone, Neck, and Head. The Backbone processes the input image, progressively reducing spatial dimensions while increasing feature depth. The Neck incorporates additional transformations, enhancing the model’s capability to handle complex scenarios such as overlapping lesions. The Head integrates final layers for object classification and bounding box regression, with non-maximum suppression (NMS) applied to refine the predictions and eliminate redundancies [

11]. This streamlined architecture makes YOLOv2 an ideal choice for resource-constrained environments where computational resources are limited.

In contrast, YOLOv8 represents a more advanced architecture, designed to overcome the limitations of earlier models while achieving superior performance. The Backbone of YOLOv8 includes multiple convolutional layers with stride reductions to extract hierarchical features while maintaining spatial information [

12]. Its Neck incorporates a Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) layer, which aggregates global contextual information, and upsampling layers that enhance the resolution of feature maps, enabling the detection of fine-grained details [

13]. Concatenation layers are used to fuse features from different levels of the network, improving the model's capacity to handle challenging cases such as small or overlapping nodules. The Head of YOLOv8 employs decoupled heads for classification and regression tasks, optimizing the network for both object detection and localization. These improvements make YOLOv8 particularly well-suited for scenarios that require high accuracy and robustness, such as identifying nodules obscured by anatomical structures.

As shown in

Figure 1, YOLOv2 and YOLOv8 illustrate their structural differences and design philosophies, both of which make them highly suitable for lightweight applications in medical imaging. YOLOv2 emphasizes simplicity and computational efficiency, featuring clearly defined modules for feature extraction, transformation, and output refinement. These characteristics allow it to perform effectively in resource-constrained environments. In comparison, YOLOv8 integrates advanced components such as the SPPF layer and multi-scale feature fusion mechanisms, enabling superior detection accuracy and operational efficiency while maintaining a lightweight design. Together, these models represent a significant advancement in object detection for medical imaging, addressing the challenges of pulmonary nodule detection in chest X-rays through their efficient architectures and adaptability to diverse clinical scenarios.

2.3. Experimental Workflow

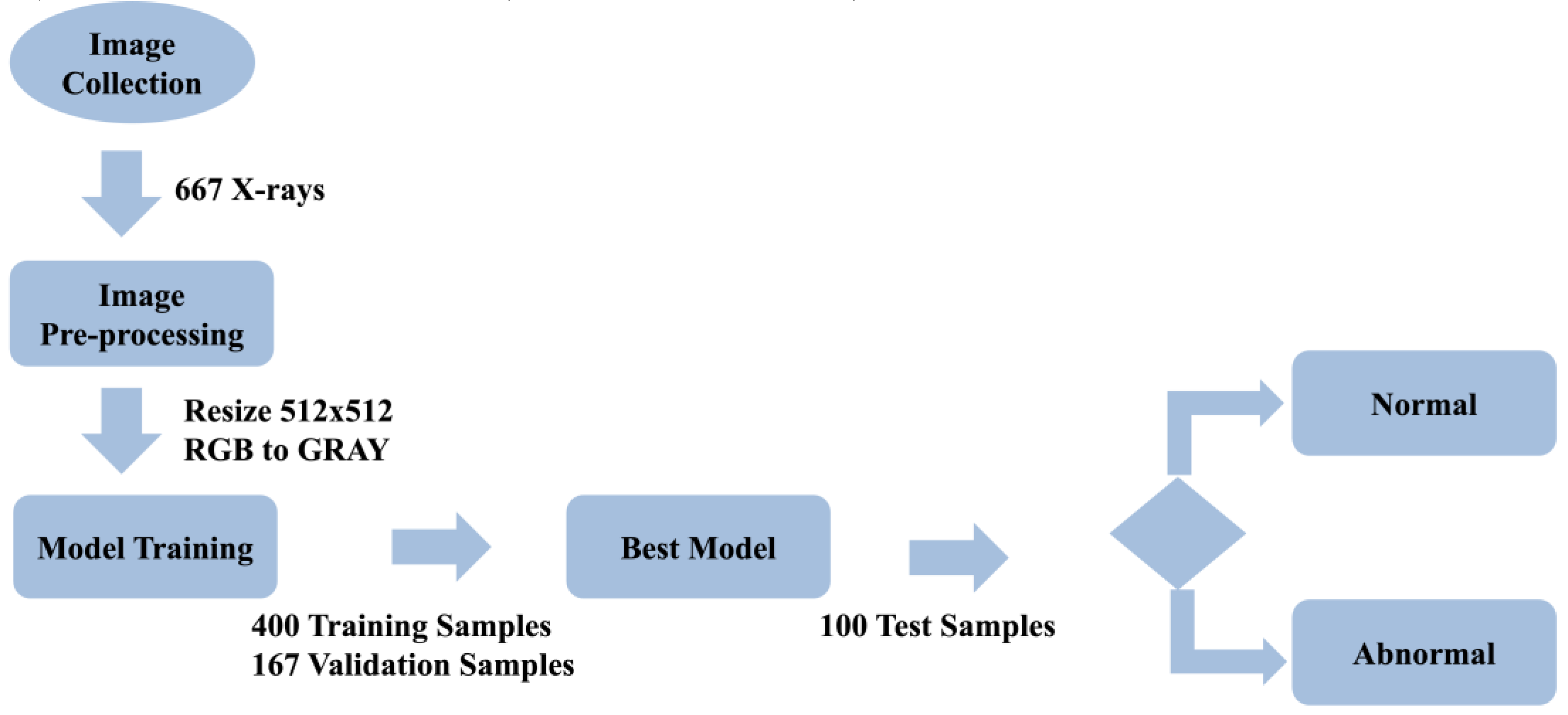

The research process began with the collection of 667 chest X-ray (CXR) images from various medical sources. These images provided a diverse dataset essential for developing and validating pulmonary nodule detection models. To ensure consistency and optimize the data for model input, all images were resized to 512 × 512 pixels and converted from RGB to grayscale during the preprocessing stage. This step not only reduced computational complexity but also retained the critical diagnostic features necessary for accurate detection.

Following preprocessing, the dataset was divided into three subsets: 400 images for training, 167 images for validation, and 100 images for testing. YOLOv2 and YOLOv8 models were initialized with pre-trained weights from the COCO dataset, leveraging transfer learning to enhance their performance on the medical imaging data. The training process employed the Adam optimizer with an initial and final learning rate of 0.01 and a batch size of 16. Loss functions combining classification and localization losses were used to optimize detection accuracy. This setup ensured efficient model training and convergence.

Once training was complete, the models were tested using the test subset of 100 images, specifically focusing on challenging cases such as overlapping nodules and lesions obscured by anatomical structures. The entire research workflow, including data collection, preprocessing, model training, and evaluation, is visually summarized in

Figure 2.

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was evaluated using three primary metrics: precision, recall, and F1-score. These metrics were selected because they provide a comprehensive assessment of detection accuracy, model robustness, and the balance between minimizing false positives and false negatives.

Precision measures the proportion of true positive cases (TP) among all predicted positive cases (TP + FP). It reflects the model’s ability to minimize false positives. A high precision value indicates that most of the predicted nodules are actual abnormalities, reducing the likelihood of false alarms, which is critical in clinical settings to avoid unnecessary follow-up examinations or interventions. Precision is calculated using the formula:

Recall, also referred to as sensitivity, evaluates the model's ability to identify all true positive cases among the actual positives (TP + FN). It measures the model’s capacity to minimize missed diagnoses by detecting as many true nodules as possible. High recall ensures that the model effectively captures all clinically significant cases, even at the expense of occasional false positives. The formula for recall is:

F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances the trade-off between these two aspects. This metric is particularly useful when both precision and recall are equally important, as it integrates the two into a unified performance measure. A high F1-score indicates that the model achieves both low false positives and low false negatives, making it well-suited for tasks where both types of errors have significant clinical implications. F1-score is calculated using the formula:

These three metrics were used to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the models in detecting pulmonary nodules. Precision ensured that detected nodules were likely to be true abnormalities, recall ensured that all potential nodules were identified, and F1-score provided a balanced evaluation when both metrics were critical. This comprehensive approach allowed for a robust assessment of the models' capabilities in maintaining high detection accuracy while minimizing errors.

2.5. Tools and Environment

The implementation and training of both YOLOv2 and YOLOv8 models were carried out in a computational environment powered by an NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU, providing the necessary processing capabilities for efficient deep learning tasks. The models were built using the PyTorch framework, which offered a flexible and robust platform for developing and fine-tuning neural networks. The ultralytics library was employed to streamline the implementation of YOLO architectures, enabling efficient integration of pre-trained weights and advanced features.

Additionally, OpenCV was used for image preprocessing, including resizing and format conversion, ensuring consistency across the dataset. Matplotlib facilitated result visualization, enabling clear representation of detection outputs and performance metrics. This combination of hardware and software tools ensured a high-performance environment for training, testing, and evaluating the models, thereby supporting the robust analysis of pulmonary nodule detection in chest X-rays.

3. Results

3.1. YOLOv2 Performance

YOLOv2 was designed with a focus on resource-constrained environments, emphasizing efficient object detection even in challenging scenarios. This aligns with its robust performance in detecting overlapping pulmonary nodules. The model's performance was evaluated during the testing phase, highlighting its ability to handle complex detection scenarios while maintaining computational efficiency, as shown in

Table 1.

Table 1 presents the model's performance metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and false positives per image. The model achieved an accuracy of 0.82, indicating its ability to classify the majority of cases correctly. Precision was measured at 0.84, demonstrating effectiveness in minimizing false positives while correctly detecting true nodules. The recall was 0.83, reflecting the model's capability to identify most true nodules and reduce missed detections. The F1-score, balancing precision and recall, was also 0.83, indicating consistent detection performance. Finally, false positives per image were 0.12, signifying a low occurrence of incorrect positive predictions, which is critical for clinical applications. These results validate the model's suitability for detecting pulmonary nodules efficiently, particularly in environments where computational resources are limited.

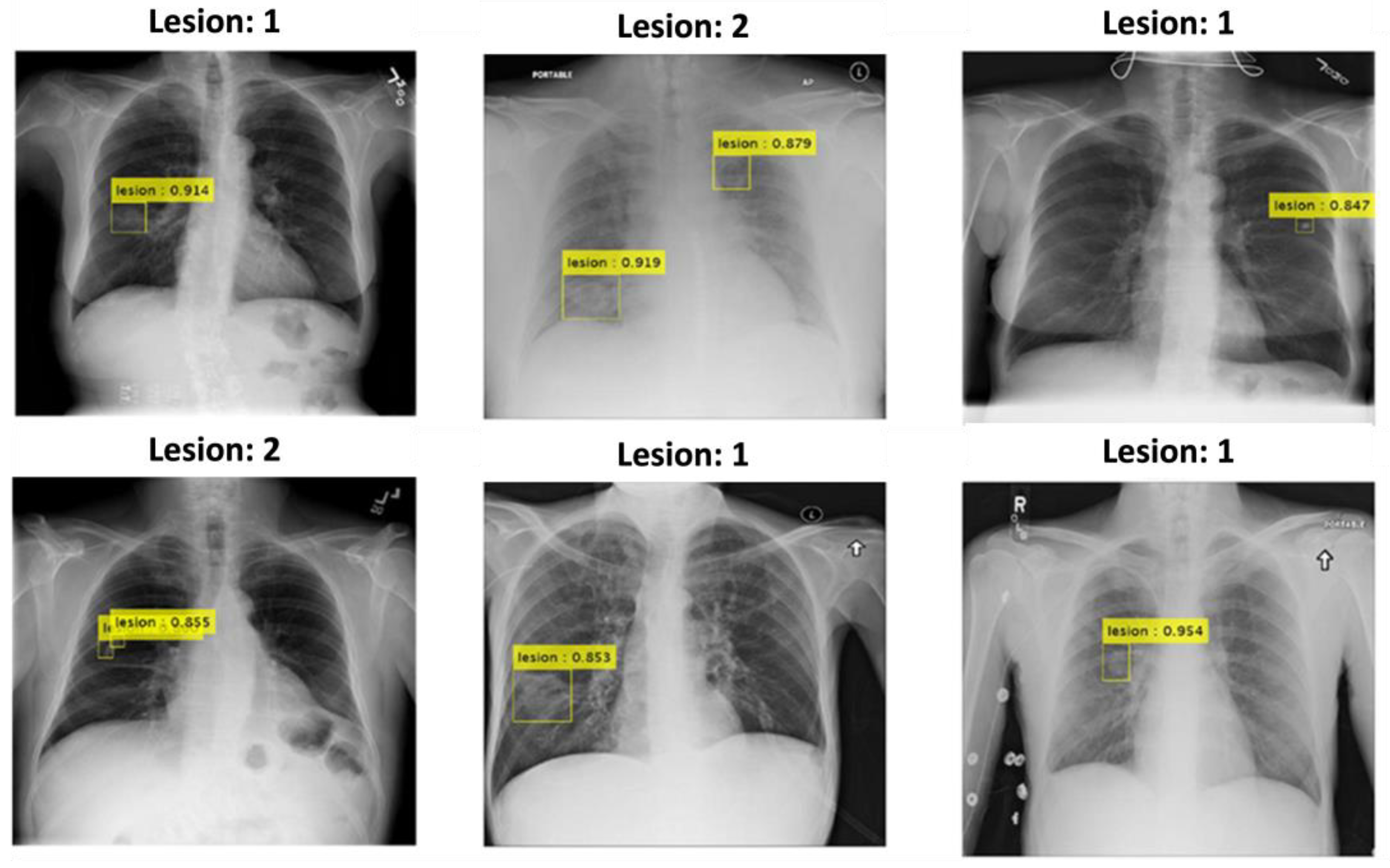

Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 3, YOLOv2 demonstrated strong performance in detecting pulmonary nodules, particularly in complex anatomical regions such as the retrocardiac and clavicular areas. The yellow bounding boxes indicate the detected nodules, with confidence scores prominently displayed, many exceeding 0.90. This highlights the model's ability to accurately identify nodules even in challenging scenarios with overlapping structures or low contrast. The results further underscore YOLOv2's suitability for clinical applications, providing reliable detection while maintaining efficiency in pulmonary nodule screening tasks. These visual examples validate the model's capability to handle spatial complexities, reinforcing its robustness in real-world clinical environments.

3.2. YOLOv8 Performance3.3. Comparison Between YOLOv2 and YOLOv8

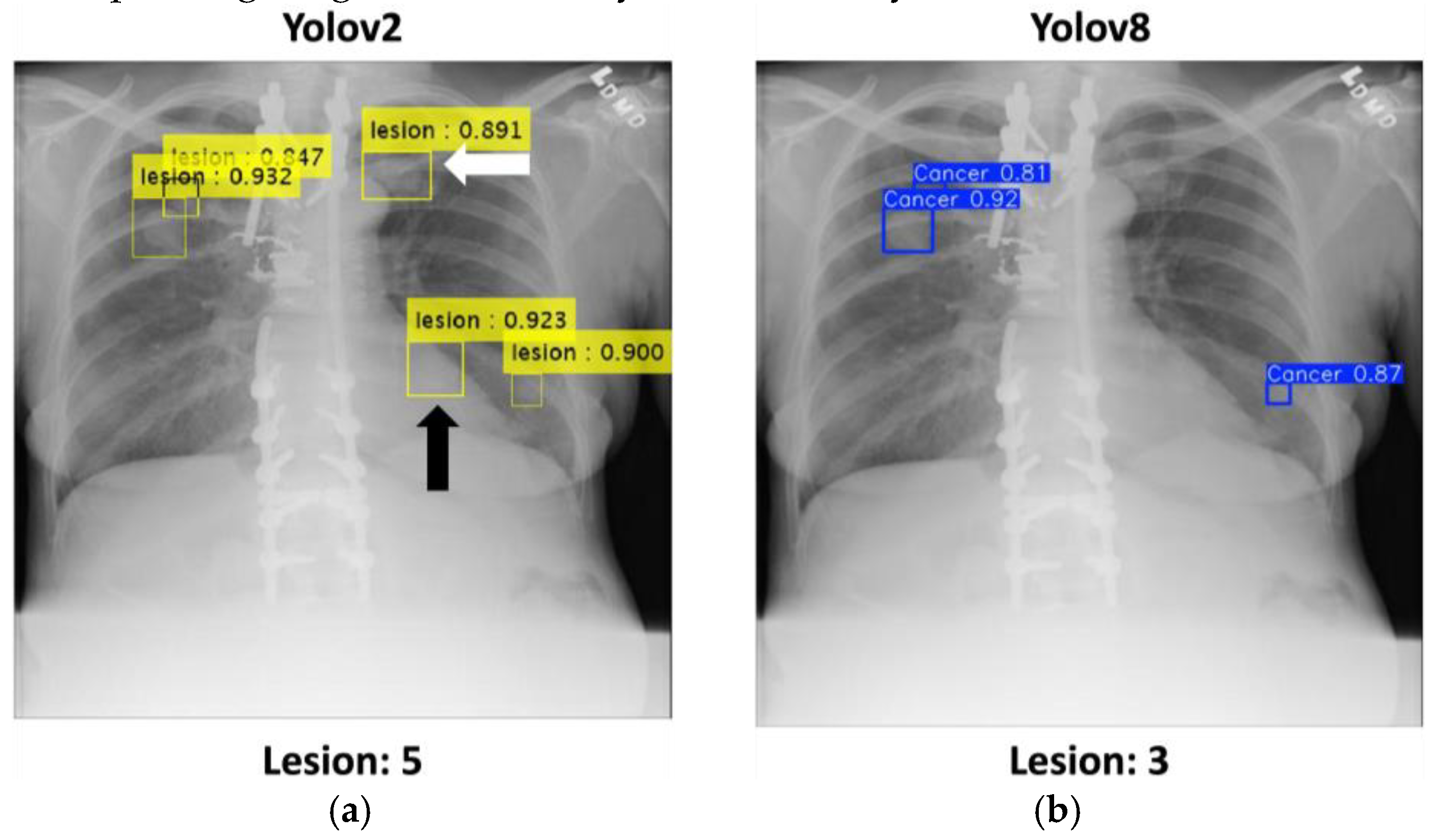

The comparison between YOLOv2 and YOLOv8 illustrates their respective abilities to detect pulmonary nodules in challenging cases. As shown in the

Figure 5, YOLOv2 demonstrates its strength in identifying overlapping nodular lesions, particularly in anatomically complex areas such as the retrocardiac region (highlighted with a black arrow) and the clavicular area (highlighted with a white arrow). The yellow bounding boxes, each accompanied by confidence scores, show multiple accurate detections, with scores exceeding 0.90, confirming its robustness in handling intricate anatomical overlaps. The total number of detected nodules by YOLOv2 is 5, showcasing its high sensitivity.

In comparison, YOLOv8 shows relatively limited effectiveness in detecting nodules in overlapping regions. As displayed in the right panel, YOLOv8 detected only three nodules, represented by blue bounding boxes with lower confidence scores, failing to detect additional nodules found in complex regions. This suggests that YOLOv5 may struggle to resolve spatial complexities and overlapping structures compared to YOLOv2.

These observations emphasize YOLOv2's reliability and accuracy in detecting nodular abnormalities in challenging cases, making it a more practical solution for resource-constrained clinical environments. The comparative results further demonstrate the potential of YOLOv2 to assist radiologists in improving diagnostic accuracy and efficiency.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

Despite the promising results achieved in this study, several limitations warrant attention. First, the dataset used, while extensive, exhibited imbalances in pathology distribution. Although pulmonary nodule detection was the primary focus, excluding pathologies such as pneumonia and pleural effusion may have limited the model's generalizability. For instance, YOLOv2 achieved an accuracy of 0.82 and recall of 0.83, but its performance might vary in datasets with more diverse pathologies. Future studies should consider more comprehensive datasets to enhance adaptability.

Moreover, YOLOv8 demonstrated lower recall (compared to YOLOv2’s 0.83) in detecting overlapping nodules. This limitation highlights the model's reduced capacity to extract contextual features in complex anatomical regions. Future research could address this issue by integrating advanced feature extraction techniques, such as attention mechanisms, to enhance performance in overlapping nodule scenarios.

4.2. Future Works

Building on the findings, several avenues for future research are proposed. First, integrating temporal imaging data, such as low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) scans or sequential X-rays, could significantly enhance model capabilities. LDCT’s three-dimensional imaging provides spatial and temporal insights critical for clinical decision-making, while follow-up X-rays could enable the detection of pulmonary nodule progression over time. Incorporating these temporal data into the training process may improve detection accuracy and adaptability to real-world clinical workflows.

Second, incorporating advanced architectures like Vision Transformers (ViT) [

15] or Swin Transformers [

16] could enhance YOLOv8’s ability to extract contextual information. These architectures have shown success in medical imaging tasks by capturing long-range dependencies and fine-grained spatial features. Applying such methods could improve the model’s robustness in detecting overlapping nodules and addressing spatial complexities.

Third, expanding the dataset to include multi-modal imaging data, such as combining X-rays with LDCT scans, could address current limitations. LDCT’s three-dimensional imaging capability complements the two-dimensional nature of X-rays, providing a more comprehensive understanding of nodule structures. Public datasets, such as LUNA16 for CT scans, could be integrated with existing CXR datasets to build a more diverse training set. This combination could also enable cross-modal learning, improving model performance across imaging modalities.

Finally, developing lightweight models optimized for real-time deployment in resource-limited settings remains a priority. Techniques like pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation could reduce computational requirements without compromising accuracy. Such models would be particularly beneficial for remote healthcare facilities or portable diagnostic tools, extending access to advanced AI technologies.

5. Conclusions

We developed a lightweight computer-aided detection (CAD) system tailored for efficient pulmonary nodule detection in chest X-rays, particularly in resource-constrained environments. By leveraging YOLOv2 and YOLOv8, the system demonstrated the ability to accurately detect abnormal nodules while maintaining computational efficiency. This achievement highlights the potential of lightweight deep learning models to address the challenges associated with medical imaging in settings with limited resources, contributing to the broader application of AI in healthcare.

The experimental results underscore the robust performance of YOLOv2, particularly in detecting overlapping nodules. The model achieved high precision, recall, and F1-scores, demonstrating its capability to balance detection accuracy and operational efficiency. This performance establishes YOLOv2 as a promising solution for scenarios where computational resources are limited. The findings further validate the potential of lightweight architectures to facilitate reliable medical image analysis while reducing the reliance on costly hardware infrastructure.

From a clinical perspective, this CAD system holds promise as an effective assistive tool for radiologists. By automating the detection of pulmonary nodules, it can alleviate the diagnostic workload, enhance screening efficiency, and improve diagnostic accuracy. The system’s ability to operate with limited resources makes it particularly relevant for deployment in low-income regions or large-scale population screenings.

However, the study has certain limitations that warrant further exploration. The dataset used, although sufficient for initial validation, exhibited imbalances in pathology distribution, which may have affected the model's generalizability. Additionally, while YOLOv2 excelled in detecting overlapping nodules, further research is recommended to test other lightweight models and integrate advanced feature extraction techniques to address more complex scenarios. Expanding the dataset to include more diverse pathologies and testing the system under varying clinical conditions will be crucial to improving its performance and robustness.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the feasibility of deploying lightweight CAD systems in medical imaging, paving the way for more accessible and scalable AI-driven diagnostic tools. Future work should focus on enhancing the system's adaptability and clinical applicability to fully realize its potential in real-world medical settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Pei-Cing Huang, Wen-Ye Chang, Chien-Ming Wu and Hao-Yun Kao; Data curation, Wen-Ye Chang; Formal analysis, Hao-Yun Kao; Investigation, Hao-Yun Kao; Methodology, Wen-Ye Chang and Guan-Yan Lin; Project administration, Chien-Ming Wu; Resources, Guan-Yan Lin and Chien-Ming Wu; Software, Pei-Cing Huang and Guan-Yan Lin; Supervision, Hao-Yun Kao; Validation, Wen-Ye Chang; Visualization, Pei-Cing Huang; Writing – original draft, Pei-Cing Huang and Chien-Ming Wu; Writing – review & editing, Hao-Yun Kao.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by Kaohsiung Medical University”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of publicly available open-source data, which did not involve the collection of new human or animal data by the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants, and the data utilized were sourced from publicly available open-source datasets without identifiable information.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study were obtained from publicly available open-source datasets, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Chest X-ray Dataset and datasets from Vietnamese medical centers. These datasets are publicly accessible and can be found at NIH Chest X-ray Dataset and VinDr-CXR Dataset. No new data were created during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Leiter, A., Veluswamy, R. R., & Wisnivesky, J. P. (2023). The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nature reviews Clinical oncology, 20(9), 624-639. [CrossRef]

- Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 71(3), 209-249.

- World Health Organization. (2023, June 26). Lung cancer. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer.

- Schemes, P. R. E. V. E. N. T. I. V. E. (2019). Pediatrics in a Resource-Constrained Setting. Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases, 141.

- Bradley, S. H., Bhartia, B. S., Callister, M. E., Hamilton, W. T., Hatton, N. L. F., Kennedy, M. P., ... & Neal, R. D. (2021). Chest X-ray sensitivity and lung cancer outcomes: a retrospective observational study. British Journal of General Practice, 71(712), e862-e868. [CrossRef]

- Henschke, C., Huber, R., Jiang, L., Yang, D., Cavic, M., Schmidt, H., ... & Lam, S. (2024). Perspective on Management of Low-Dose Computed Tomography Findings on Low-Dose Computed Tomography Examinations for Lung Cancer Screening. From the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Early Detection and Screening Committee. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 19(4), 565-580.

- National Institutes of Health. (2011, June 29). NIH-funded study shows 20 percent reduction in lung cancer mortality with low-dose CT compared to chest X-ray. Available at https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-funded-study-shows-20-percent-reduction-lung-cancer-mortality-low-dose-ct-compared-chest-x-ray.

- Redmon, J., & Farhadi, A. (2017). YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 7263-7271).

- Varghese, R., & Sambath, M. (2024, April). YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness. In 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Hu, M., Li, Z., Yu, J., Wan, X., Tan, H., & Lin, Z. (2023). Efficient-lightweight yolo: Improving small object detection in yolo for aerial images. Sensors, 23(14), 6423.

- Gallagher, J. E., & Oughton, E. J. (2024). Surveying You Only Look Once (YOLO) Multispectral Object Detection Advancements, Applications And Challenges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.12977. [CrossRef]

- Alhawsawi, A. N., Khan, S. D., & Rehman, F. U. (2024). Enhanced YOLOv8-Based Model with Context Enrichment Module for Crowd Counting in Complex Drone Imagery. Remote Sensing, 16(22), 4175.

- Zhou, S., & Zhou, H. (2024). Detection based on semantics and a detail infusion feature pyramid network and a coordinate adaptive spatial feature fusion mechanism remote sensing small object detector. Remote Sensing, 16(13), 2416. [CrossRef]

- Powers, D. M. (2020). Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.16061.

- Dosovitskiy, A. (2020). An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929.

- Liu, Z., Lin, Y., Cao, Y., Hu, H., Wei, Y., Zhang, Z., ... & Guo, B. (2021). Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (pp. 10012-10022).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).