Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Neovascular AMD and Fibrosis

3. Molecular Mechanisms of Submacular Fibrosis

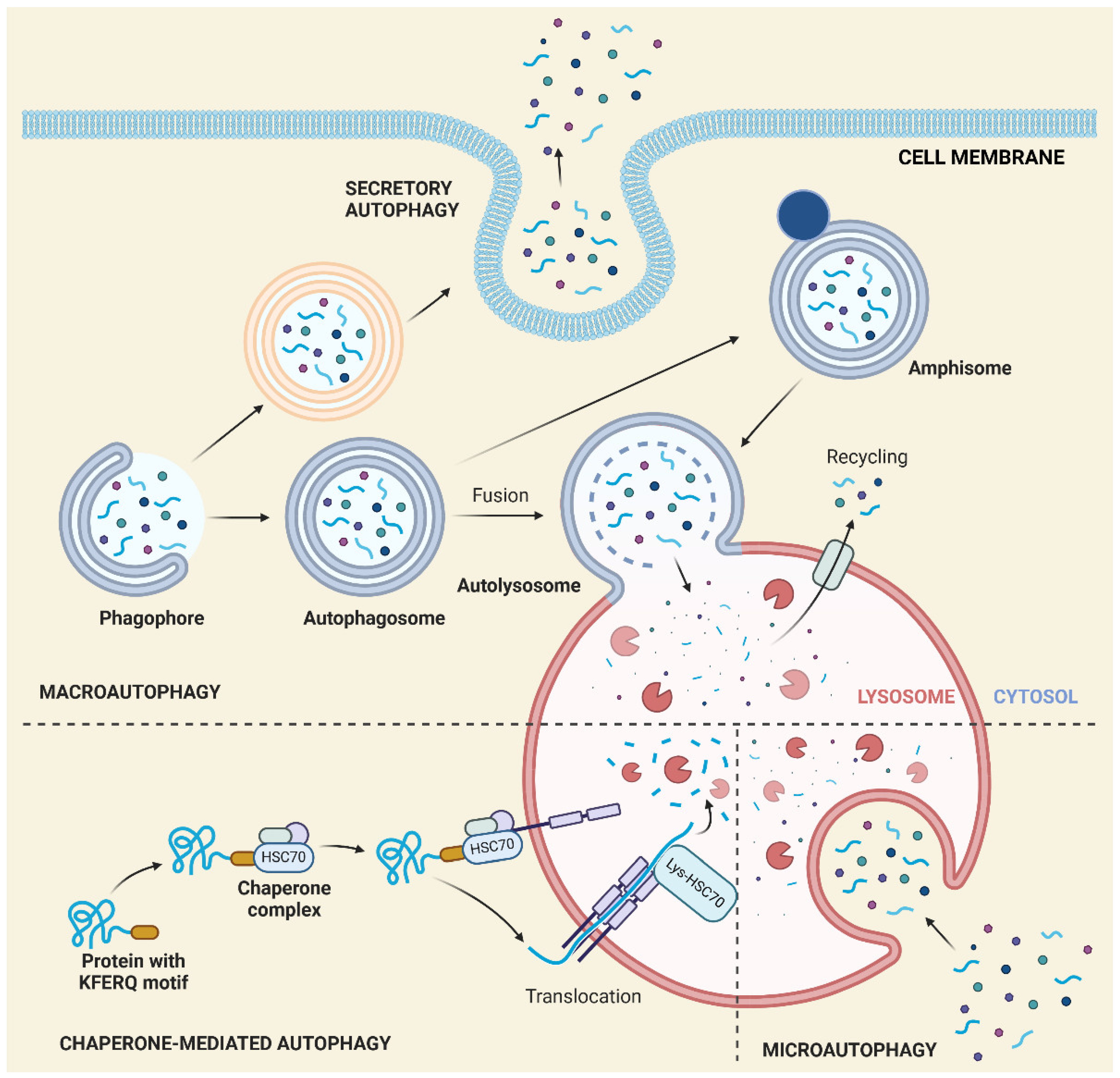

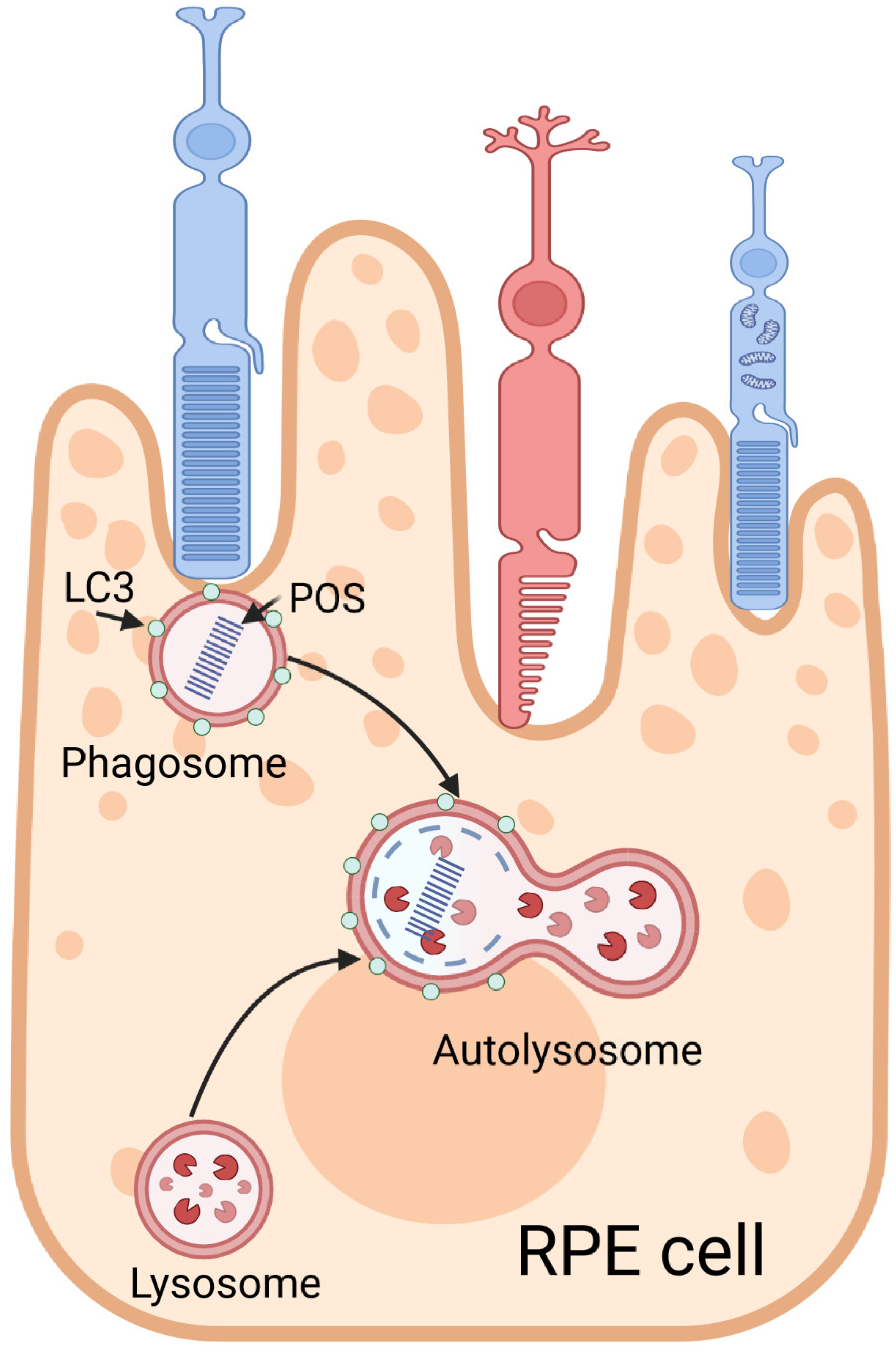

4. Autophagy in AMD

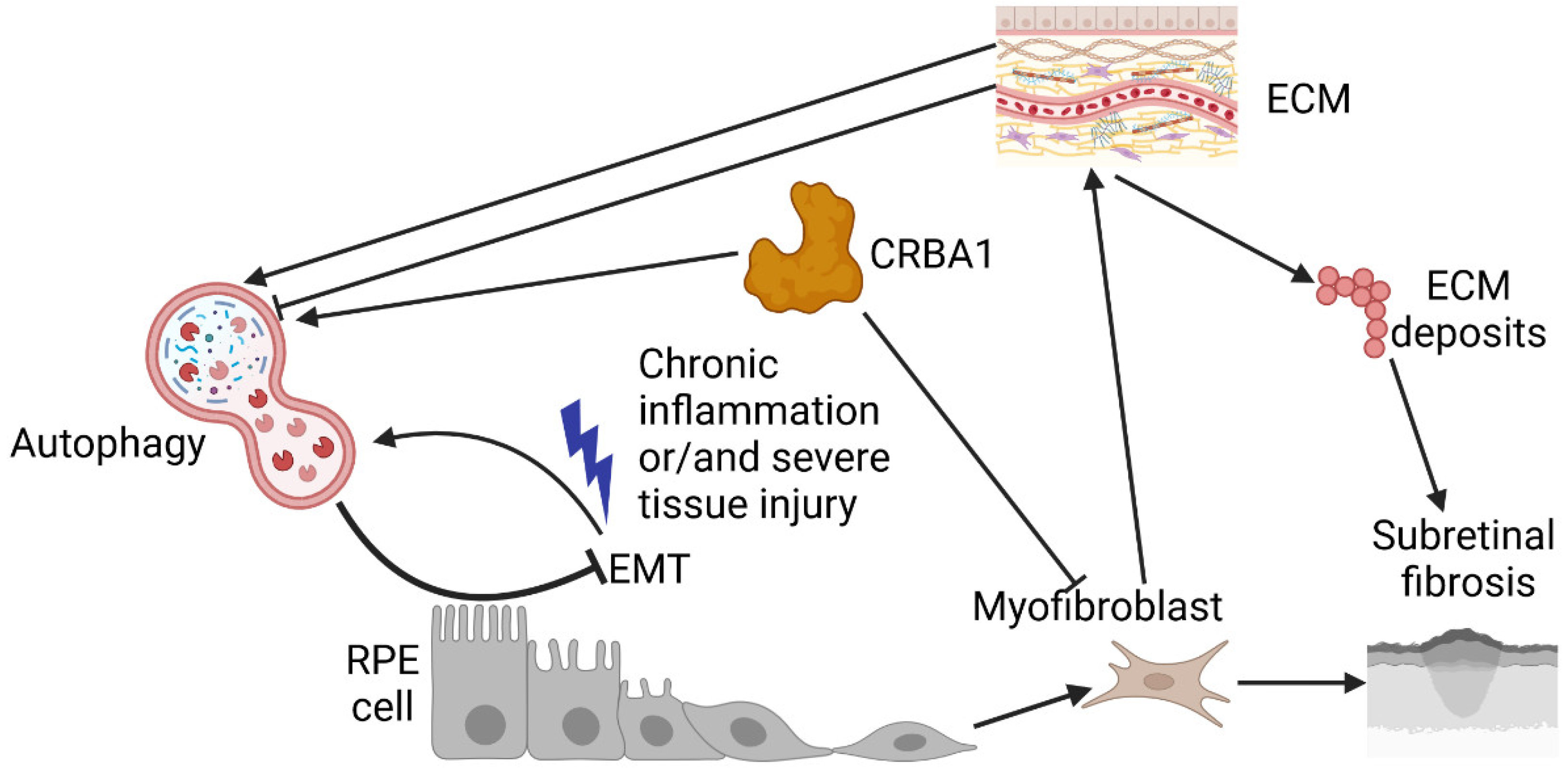

5. Impaired Autophagy Related to Submacular Fibrosis

6. Conclusions, Outstanding Questions, and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by age-related macular degeneration: a meta-analysis from 2000 to 2020. Eye (Lond) 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fine, S.L.; Berger, J.W.; Maguire, M.G.; Ho, A.C. Age-related macular degeneration. The New England journal of medicine 2000, 342, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleckenstein, M.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Guymer, R.H.; Chakravarthy, U.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, N.M.; Bhardwaj, S.; Barclay, C.; Gaspar, L.; Schwartz, J. Global Burden of Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Targeted Literature Review. Clinical therapeutics 2021, 43, 1792–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.B.; Heier, J.S.; Chaudhary, V.; Wykoff, C.C. Treatment of geographic atrophy: an update on data related to pegcetacoplan. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2024, 35, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatner, S.F.; Zhang, J.; Oydanich, M.; Berkman, T.; Naftalovich, R.; Vatner, D.E. Healthful aging mediated by inhibition of oxidative stress. Aging research reviews 2020, 64, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, R.; Paul, P.; Sophie, P.; Hollingsworth, T.J.; Ilyse, K.; Monica, M.J. An Overview of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Clinical, Pre-Clinical Animal Models and Bidirectional Translation. In Preclinical Animal Modeling in Medicine, Enkhsaikhan, P., Joseph, F.P., Lu, L., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Roodhooft, J. No efficacious treatment for age-related macular degeneration. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 2000, 276, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Zachary, I.; Jia, H. Mechanisms of Acquired Resistance to Anti-VEGF Therapy for Neovascular Eye Diseases. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2023, 64, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, I.M.; Gerometta, M.; Eichenbaum, D.; Finger, R.P.; Steinle, N.C.; Baldwin, M.E. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor C and D Signaling Pathways as Potential Targets for the Treatment of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Narrative Review. Ophthalmol Ther 2024, 13, 1857–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Webster, K.A.; Paulus, Y.M. Treatment Strategies for Anti-VEGF Resistance in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration by Targeting Arteriolar Choroidal Neovascularization. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, K.; Ma, J.H.; Yang, N.; Chen, M.; Xu, H. Myofibroblasts in macular fibrosis secondary to neovascular age-related macular degeneration - the potential sources and molecular cues for their recruitment and activation. EBioMedicine 2018, 38, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.J.; Park, K.H.; Woo, S.J. SUBRETINAL FIBROSIS AFTER ANTIVASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL GROWTH FACTOR THERAPY IN EYES WITH MYOPIC CHOROIDAL NEOVASCULARIZATION. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.) 2016, 36, 2140–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.; Sun, L.; Xin, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, J.; Ding, X. Risk factors for subretinal fibrosis after anti-VEGF treatment of myopic choroidal neovascularisation. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2021, 105, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, P.K.; Blodi, B.A.; Shapiro, H.; Acharya, N.R. Angiographic and optical coherence tomographic results of the MARINA study of ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, G.L.; Benedicto, I.; Philp, N.J.; Rodriguez-Boulan, E. Plasma membrane protein polarity and trafficking in RPE cells: past, present and future. Experimental eye research 2014, 126, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesi, S.B.; Désogère, P.; Fuchs, B.C.; Caravan, P. Molecular imaging of fibrosis: recent advances and future directions. The Journal of clinical investigation 2019, 129, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, M. Mechanisms of fibrosis. Seminars in cell & developmental biology 2020, 101, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Kwan, J.Y.Y.; Yip, K.; Liu, P.P.; Liu, F.F. Targeting metabolic dysregulation for fibrosis therapy. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2020, 19, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Haens, G.; Rieder, F.; Feagan, B.G.; Higgins, P.D.R.; Panés, J.; Maaser, C.; Rogler, G.; Löwenberg, M.; van der Voort, R.; Pinzani, M.; et al. Challenges in the Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Intestinal Fibrosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys, B.D. Mechanisms of Renal Fibrosis. Annu Rev Physiol 2018, 80, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, B.; Ravassa, S.; Moreno, M.U.; José, G.S.; Beaumont, J.; González, A.; Díez, J. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis: mechanisms, diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. Nature reviews. Cardiology 2021, 18, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B.J.; Ryter, S.W.; Rosas, I.O. Pathogenic Mechanisms Underlying Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2022, 17, 515–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.W.; Shih, Y.H.; Fuh, L.J.; Shieh, T.M. Oral Submucous Fibrosis: A Review on Biomarkers, Pathogenic Mechanisms, and Treatments. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, H.E.; Mascharak, S.; Griffin, M.; Wan, D.C.; Longaker, M.T. Wound healing, fibroblast heterogeneity, and fibrosis. Cell stem cell 2022, 29, 1161–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, N.C.; Rieder, F.; Wynn, T.A. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature 2020, 587, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasiak, J.; Kaarniranta, K. Secretory autophagy: a turn key for understanding AMD pathology and developing new therapeutic targets? Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2022, 26, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Blasiak, J.; Liton, P.; Boulton, M.; Klionsky, D.J.; Sinha, D. Autophagy in age-related macular degeneration. Autophagy 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Wu, J.; Li, X. Self-eating: friend or foe? The emerging role of autophagy in fibrotic diseases. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7993–8017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudstaal, T.; Wijsenbeek, M.S. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. La Presse Médicale 2023, 52, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin, V.; Wollin, L.; Fischer, A.; Quaresma, M.; Stowasser, S.; Harari, S. Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: knowns and unknowns. Eur Respir Rev 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.L.; Miao, H.; Wang, Y.N.; Liu, F.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.Y. TGF-β as A Master Regulator of Aging-Associated Tissue Fibrosis. Aging and disease 2023, 14, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A. Fibroageing: An aging pathological feature driven by dysregulated extracellular matrix-cell mechanobiology. Aging research reviews 2021, 70, 101393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M. Advances in the management of macular degeneration. F1000Prime Rep 2014, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, J.; Watala, C.; Tuuminen, R.; Kivinen, N.; Koskela, A.; Uusitalo-Järvinen, H.; Tuulonen, A.; Winiarczyk, M.; Mackiewicz, J.; Zmorzyński, S.; et al. Expression of VEGFA-regulating miRNAs and mortality in neovascular AMD. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2019, 23, 8464–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakaliou, A.; Georgakopoulos, C.; Tsilimbaris, M.; Farmakakis, N. Posterior Vitreous Detachment and Its Role in the Evolution of Dry to Neovascular Age Related Macular Degeneration. Clin Ophthalmol 2023, 17, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaide, R.F.; Jaffe, G.J.; Sarraf, D.; Freund, K.B.; Sadda, S.R.; Staurenghi, G.; Waheed, N.K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Rosenfeld, P.J.; Holz, F.G.; et al. Consensus Nomenclature for Reporting Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Data: Consensus on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Nomenclature Study Group. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 616–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Banait, S. Through the Smoke: An In-Depth Review on Cigarette Smoking and Its Impact on Ocular Health. Cureus 2023, 15, e47779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.L.; Quinn, J.; Xue, K. Interactions between Apolipoprotein E Metabolism and Retinal Inflammation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Life (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Fu, Y.; Baird, P.N.; Guymer, R.H.; Das, T.; Iwata, T. Exploring the contribution of ARMS2 and HTRA1 genetic risk factors in age-related macular degeneration. Progress in retinal and eye research 2023, 97, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshanshad, A.; Moosavi, S.A.; Arevalo, J.F. Association of the Complement Factor H Y402H Polymorphism and Response to Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Treatment in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmic Res 2024, 67, 358–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauppinen, A.; Paterno, J.J.; Blasiak, J.; Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. Inflammation and its role in age-related macular degeneration. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 2016, 73, 1765–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, I.; Lutty, G. Understanding age-related macular degeneration (AMD): relationships between the photoreceptor/retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch’s membrane/choriocapillaris complex. Molecular aspects of medicine 2012, 33, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrean, S.D.; Morgenthien, E.; Ghanekar, A.; Ali, F.S. Subretinal Fibrosis in HARBOR Varies by Choroidal Neovascularization Subtype. Ophthalmol Retina 2020, 4, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenbrock, L.; Wolf, J.; Boneva, S.; Schlecht, A.; Agostini, H.; Wieghofer, P.; Schlunck, G.; Lange, C. Subretinal fibrosis in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: current concepts, therapeutic avenues, and future perspectives. Cell and tissue research 2022, 387, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rofagha, S.; Bhisitkul, R.B.; Boyer, D.S.; Sadda, S.R.; Zhang, K. Seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: a multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 2292–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, P.J.; Shapiro, H.; Tuomi, L.; Webster, M.; Elledge, J.; Blodi, B. Characteristics of patients losing vision after 2 years of monthly dosing in the phase III ranibizumab clinical trials. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmeier, I.; Armendariz, B.G.; Yu, S.; Jäger, R.J.; Ebneter, A.; Glittenberg, C.; Pauleikhoff, D.; Sadda, S.R.; Chakravarthy, U.; Fauser, S. Fibrosis in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A review of definitions based on clinical imaging. Survey of ophthalmology 2023, 68, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmeier, I.; Armendariz, B.G.; Yu, S.; Jäger, R.J.; Ebneter, A.; Glittenberg, C.; Pauleikhoff, D.; Sadda, S.R.; Chakravarthy, U.; Fauser, S. Corrigendum to “Fibrosis in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a review of definitions based on clinical imaging” [Surv Ophthalmol 68 (2023) 835-848/5]. Survey of ophthalmology 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.H.; Martidis, A.; Greenberg, P.B.; Puliafito, C.A. Optical coherence tomography findings following photodynamic therapy of choroidal neovascularization. American journal of ophthalmology 2002, 134, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, F.; Cozzi, E.; Airaldi, M.; Nassisi, M.; Viola, F.; Aretti, A.; Milella, P.; Giuffrida, F.P.; Teo, K.C.Y.; Cheung, C.M.G.; et al. Ten-Year Incidence of Fibrosis and Risk Factors for Its Development in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. American journal of ophthalmology 2023, 252, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, E.; Pan, W.; Ying, G.S.; Kim, B.J.; Grunwald, J.E.; Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Jaffe, G.J.; Toth, C.A.; Martin, D.F.; Fine, S.L.; et al. Development and Course of Scars in the Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, K.Y.C.; Joe, A.W.; Nguyen, V.; Invernizzi, A.; Arnold, J.J.; Barthelmes, D.; Gillies, M. PREVALENCE AND RISK FACTORS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF PHYSICIAN-GRADED SUBRETINAL FIBROSIS IN EYES TREATED FOR NEOVASCULAR AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.) 2020, 40, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenberg, S.; Nittala, M.G.; Verma, A.; Fitzgerald, M.E.C.; Velaga, S.B.; Bhisitkul, R.B.; Sadda, S.R. Subretinal hyperreflective material in regions of atrophy and fibrosis in eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Can J Ophthalmol 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, F.; Campbell, M. The blood‒retina barrier in health and disease. Febs j 2023, 290, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, M.; Grebe, R.; Bhutto, I.A.; Edwards, M.; McLeod, D.S.; Lutty, G.A. Albumen Transport to Bruch’s Membrane and RPE by Choriocapillaris Caveolae. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2016, 57, 2213–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heloterä, H.; Kaarniranta, K. A Linkage between Angiogenesis and Inflammation in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, L.; Stalfort, J.; Barker, T.H.; Abebayehu, D. The interplay of fibroblasts, the extracellular matrix, and inflammation in scar formation. The Journal of biological chemistry 2022, 298, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.K.; Zotter, S.; Montuoro, A.; Pircher, M.; Baumann, B.; Ritter, M.; Hitzenberger, C.K.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U. Identification and Quantification of the Angiofibrotic Switch in Neovascular AMD. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2019, 60, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saika, S.; Yamanaka, O.; Sumioka, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Okada, Y.; Kitano, A.; Shirai, K.; Tanaka, S.; Ikeda, K. Fibrotic disorders in the eye: targets of gene therapy. Progress in retinal and eye research 2008, 27, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Sheng, X.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J. Subretinal fibrosis secondary to neovascular age-related macular degeneration: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Neural Regeneration Research 2025, 20, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chung, J.Y.; Rai, U.; Esumi, N. Cadherins in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) revisited: P-cadherin is the highly dominant cadherin expressed in human and mouse RPE in vivo. PloS one 2018, 13, e0191279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamiya, S.; Liu, L.; Kaplan, H.J. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Proliferation of Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Initiated upon Loss of Cell‒Cell Contact. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2010, 51, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, W.L.; Weinberg, R.A. The epigenetics of epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Nat Med 2013, 19, 1438–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamiya, S.; Liu, L.; Kaplan, H.J. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition and proliferation of retinal pigment epithelial cells initiated upon loss of cell‒cell contact. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2010, 51, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, D.Y.; Butcher, E.; Saint-Geniez, M. EMT and EndMT: Emerging Roles in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, K.; Yoo, H.-S.; Chakravarthy, H.; Granville, D.J.; Matsubara, J.A. Exploring the role of granzyme B in subretinal fibrosis of age-related macular degeneration. Front Immunol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieghofer, P.; Hagemeyer, N.; Sankowski, R.; Schlecht, A.; Staszewski, O.; Amann, L.; Gruber, M.; Koch, J.; Hausmann, A.; Zhang, P.; et al. Mapping the origin and fate of myeloid cells in distinct compartments of the eye by single-cell profiling. The EMBO journal 2021, 40, e105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Tan, M.S.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L. Role of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Transl Med 2015, 3, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, R.T.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A. Fibroblasts in fibrosis: novel roles and mediators. Frontiers in pharmacology 2014, 5, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafe, I.; Alexander, S.; Peterson, J.R.; Snider, T.N.; Levi, B.; Lee, B.; Mishina, Y. TGF-β Family Signaling in Mesenchymal Differentiation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saika, S.; Kono-Saika, S.; Tanaka, T.; Yamanaka, O.; Ohnishi, Y.; Sato, M.; Muragaki, Y.; Ooshima, A.; Yoo, J.; Flanders, K.C.; et al. Smad3 is required for dedifferentiation of retinal pigment epithelium following retinal detachment in mice. Lab Invest 2004, 84, 1245–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Chu, H.Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.-K.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, B.-T. Connective Tissue Growth Factor: From Molecular Understandings to Drug Discovery. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daftarian, N.; Rohani, S.; Kanavi, M.R.; Suri, F.; Mirrahimi, M.; Hafezi-Moghadam, A.; Soheili, Z.S.; Ahmadieh, H. Effects of intravitreal connective tissue growth factor neutralizing antibody on choroidal neovascular membrane-associated subretinal fibrosis. Experimental eye research 2019, 184, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, Y.; Nonaka, Y.; Futakawa, S.; Imai, H.; Akita, K.; Nishihata, T.; Fujiwara, M.; Ali, Y.; Bhisitkul, R.B.; Nakamura, Y. Anti-Angiogenic and Anti-Scarring Dual Action of an Anti-Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Aptamer in Animal Models of Retinal Disease. Molecular therapy. Nucleic acids 2019, 17, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Hirose, M.; Kagawa, T.; Hatsuda, K.; Inoue, Y. Platelet-derived growth factor can predict survival and acute exacerbation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Journal of Thoracic Disease 2022, 14, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Noda, K.; Murata, M.; Wu, D.; Kanda, A.; Ishida, S. Blockade of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Signaling Inhibits Choroidal Neovascularization and Subretinal Fibrosis in Mice. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendariz, B.G.; Chakravarthy, U. Fibrosis in age-related neovascular macular degeneration in the anti-VEGF era. Eye (Lond) 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.F.; Dvorak, A.M.; Dvorak, H.F. Leaky vessels, fibrin deposition, and fibrosis: a sequence of events common to solid tumors and to many other types of disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989, 140, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wight, T.N.; Potter-Perigo, S. The extracellular matrix: an active or passive player in fibrosis? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2011, 301, G950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, T.; Annamalai, B.; Obert, E.; Simpson, K.N.; Rohrer, B. Dabigatran and Neovascular AMD, Results From Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cell Monolayers, the Mouse Model of Choroidal Neovascularization, and Patients From the Medicare Data Base. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 896274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heloterä, H.; Siintamo, L.; Kivinen, N.; Abrahamsson, N.; Aaltonen, V.; Kaarniranta, K. Analysis of prognostic and predictive factors in neovascular age-related macular degeneration Kuopio cohort. Acta Ophthalmologica 2024, 102, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.S.; Probst, C.K.; Brazee, P.L.; Rotile, N.J.; Blasi, F.; Weinreb, P.H.; Black, K.E.; Sosnovik, D.E.; Van Cott, E.M.; Violette, S.M.; et al. Uncoupling of the profibrotic and hemostatic effects of thrombin in lung fibrosis. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouw, A.E.; Greiner, M.A.; Coussa, R.G.; Jiao, C.; Han, I.C.; Skeie, J.M.; Fingert, J.H.; Mullins, R.F.; Sohn, E.H. Cell-Matrix Interactions in the Eye: From Cornea to Choroid. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakama, T.; Yoshida, S.; Ishikawa, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Nakao, S.; Sassa, Y.; Oshima, Y.; Takao, K.; Shimahara, A.; et al. Inhibition of choroidal fibrovascular membrane formation by new class of RNA interference therapeutic agent targeting periostin. Gene Ther 2015, 22, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Umeno, Y.; Haruta, M. Periostin in Eye Diseases. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2019, 1132, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehner, D.; Tsarouchas, T.M.; Michael, A.; Haase, C.; Weidinger, G.; Reimer, M.M.; Becker, T.; Becker, C.G. Wnt signaling controls pro-regenerative Collagen XII in functional spinal cord regeneration in zebrafish. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, S.; Liang, X.; Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Zong, R.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z. Fenofibrate Inhibits Subretinal Fibrosis Through Suppressing TGF-β—Smad2/3 signaling and Wnt signaling in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, M.; Gagne, N.; Hafiz, G.; Mir, T.; Survi, M.; Barefoot, L.; Cardia, J.; Bulock, K.; Pavco, P.A.; Campochiaro, P.A. A Phase 1/2 multidose, dose escalation study to evaluate RXI-109 administered by intravitreal injection to reduce the progression of subretinal fibrosis in subjects with advanced neovascular AMD (NVAMD). Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2017, 58, 3210–3210. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, S.B.; Lund-Andersen, H.; Sander, B.; Larsen, M. Subfoveal fibrosis in eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal ranibizumab. American journal of ophthalmology 2013, 156, 116–124e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashijima, F.; Hasegawa, M.; Yoshimoto, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Wakuta, M.; Kimura, K. Molecular mechanisms of TGFβ-mediated EMT of retinal pigment epithelium in subretinal fibrosis of age-related macular degeneration. Frontiers in Ophthalmology 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xu, G.-T.; Zhang, J. Molecular pathogenesis of subretinal fibrosis in neovascular AMD focusing on epithelial–mesenchymal transformation of retinal pigment epithelium. Neurobiology of Disease 2023, 185, 106250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Petroni, G.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Ballabio, A.; Boya, P.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Cadwell, K.; Cecconi, F.; Choi, A.M.K.; et al. Autophagy in major human diseases. The EMBO journal 2021, 40, e108863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Klionsky, D.J.; Shen, H.-M. The emerging mechanisms and functions of microautophagy. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023, 24, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.L.; Terlecky, S.R.; Plant, C.P.; Dice, J.F. A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1989, 246, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuervo, A.M.; Dice, J.F. A receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1996, 273, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejarano, E.; Cuervo, A.M. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010, 7, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buratta, S.; Tancini, B.; Sagini, K.; Delo, F.; Chiaradia, E.; Urbanelli, L.; Emiliani, C. Lysosomal Exocytosis, Exosome Release and Secretory Autophagy: The Autophagic- and Endo-Lysosomal Systems Go Extracellular. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Sagar, S.; Ravindran, R.; Najor, R.H.; Quiles, J.M.; Chi, L.; Diao, R.Y.; Woodall, B.P.; Leon, L.J.; Zumaya, E.; et al. Mitochondria are secreted in extracellular vesicles when lysosomal function is impaired. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; He, D.; Yao, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell research 2014, 24, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, J.A. Role of the mammalian ATG8/LC3 family in autophagy: differential and compensatory roles in the spatiotemporal regulation of autophagy. BMB Rep 2016, 49, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Purtell, K.; Lachance, V.; Wold, M.S.; Chen, S.; Yue, Z. Autophagy Receptors and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Trends in cell biology 2017, 27, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, R.; Cafiso, D.C.; Tamm, L.K. Mechanisms of SNARE proteins in membrane fusion. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2024, 25, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, A.; Ernst, A.; Dikic, I. Cargo recognition and trafficking in selective autophagy. Nature cell biology 2014, 16, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuPont, N.; Jiang, S.; Pilli, M.; Ornatowski, W.; Bhattacharya, D.; Deretic, V. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. The EMBO journal 2011, 30, 4701–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claude-Taupin, A.; Bissa, B.; Jia, J.; Gu, Y.; Deretic, V. Role of autophagy in IL-1β export and release from cells. Seminars in cell & developmental biology 2018, 83, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Zhao, H.; Martinez, J.; Doggett, T.A.; Kolesnikov, A.V.; Tang, P.H.; Ablonczy, Z.; Chan, C.C.; Zhou, Z.; Green, D.R.; et al. Noncanonical autophagy promotes the visual cycle. Cell 2013, 154, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Petrovski, G.; Kauppinen, A. The Nobel Prized cellular target autophagy in eye diseases. Acta Ophthalmol 2017, 95, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Koskela, A.; Blasiak, J.; Kaarniranta, K. Autophagy in drusen biogenesis secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Golestaneh, N.; Chu, Y.; Xiao, Y.-Y.; Stoleru, G.L.; Theos, A.C. Dysfunctional autophagy in RPE, a contributing factor in age-related macular degeneration. Cell death & disease 2018, 8, e2537–e2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirichen, H.; Yaigoub, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Contribution in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression Through Oxidative Stress. Frontiers in physiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinelli, R.; Ferrucci, M.; Biagioni, F.; Berti, C.; Bumah, V.V.; Busceti, C.L.; Puglisi-Allegra, S.; Lazzeri, G.; Frati, A.; Fornai, F. Autophagy Activation Promoted by Pulses of Light and Phytochemicals Counteracting Oxidative Stress during Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, M.; Grzybowski, A. Antioxidative Role of Heterophagy, Autophagy, and Mitophagy in the Retina and Their Association with the Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Etiopathogenesis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.; Yu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, J.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, J.; Shen, H. Gastrodin ameliorates oxidative stress-induced RPE damage by facilitating autophagy and phagocytosis through PPARα-TFEB/CD36 signaling pathway. Free Radic Biol Med 2024, 224, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Sharma, R.; Bammidi, S.; Koontz, V.; Nemani, M.; Yazdankhah, M.; Kedziora, K.M.; Stolz, D.B.; Wallace, C.T.; Yu-Wei, C.; et al. The AKT2/SIRT5/TFEB pathway as a potential therapeutic target in nonneovascular AMD. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Koskela, A.; Blasiak, J.; Kaarniranta, K. Autophagy in drusen biogenesis secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol 2024, 102, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vessey, K.A.; Jobling, A.I.; Greferath, U.; Fletcher, E.L. Pharmaceutical therapies targeting autophagy for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2024, 76, 102463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachigian, L.M.; Liew, G.; Teo, K.Y.C.; Wong, T.Y.; Mitchell, P. Emerging therapeutic strategies for unmet need in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Journal of translational medicine 2023, 21, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamark, T.; Johansen, T. Mechanisms of Selective Autophagy. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2021, 37, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cross, S.D.; Stanton, J.B.; Marmorstein, A.D.; Le, Y.Z.; Marmorstein, L.Y. Early AMD-like defects in the RPE and retinal degeneration in aged mice with RPE-specific deletion of Atg5 or Atg7. Molecular vision 2017, 23, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abokyi, S.; To, C.-H.; Lam, T.T.; Tse, D.Y. Central Role of Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Evidence from a Review of the Molecular Mechanisms and Animal Models. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2020, 2020, 7901270–7901270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, S.K.; Song, C.; Qi, X.; Mao, H.; Rao, H.; Akin, D.; Lewin, A.; Grant, M.; Dunn, W., Jr.; Ding, J.; et al. Dysregulated autophagy in the RPE is associated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress and AMD. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1989–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piippo, N.; Korhonen, E.; Hytti, M.; Kinnunen, K.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Oxidative Stress is the Principal Contributor to Inflammasome Activation in Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells with Defunct Proteasomes and Autophagy. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 49, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVail, M.M. Rod outer segment disk shedding in rat retina: relationship to cyclic lighting. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1976, 194, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, J.; Sobczuk, P.; Pawlowska, E.; Kaarniranta, K. Interplay between aging and other factors of the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Aging research reviews 2022, 81, 101735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterno, J.J.; Koskela, A.; Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Vattulainen, E.; Synowiec, E.; Tuuminen, R.; Watala, C.; Blasiak, J.; Kaarniranta, K. Autophagy Genes for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Finnish Case‒Control Study. Genes 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Kouis, P.; Rasmussen, L.J.; Dai, F. Effects of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial dysfunction on reproductive aging. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemasters, J.J. Selective mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res 2005, 8, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.C.; Holzbaur, E.L. Optineurin is an autophagy receptor for damaged mitochondria in parkin-mediated mitophagy that is disrupted by an ALS-linked mutation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, E4439–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felszeghy, S.; Viiri, J.; Paterno, J.J.; Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Koskela, A.; Chen, M.; Leinonen, H.; Tanila, H.; Kivinen, N.; Koistinen, A.; et al. Loss of NRF-2 and PGC-1alpha genes leads to retinal pigment epithelium damage resembling dry age-related macular degeneration. Redox biology 2019, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridevi Gurubaran, I.; Viiri, J.; Koskela, A.; Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Paterno, J.J.; Kis, G.; Antal, M.; Urtti, A.; Kauppinen, A.; Felszeghy, S.; et al. Mitophagy in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium of Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration Investigated in the NFE2L2/PGC-1α(-/-) Mouse Model. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.W.S.; Lu, G.; Dong, H.; Cho, Y.L.; Natalia, A.; Wang, L.; Chan, C.; Kappei, D.; Taneja, R.; Ling, S.C.; et al. A degradative to secretory autophagy switch mediates mitochondria clearance in the absence of the mATG8-conjugation machinery. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konig, J.; Ott, C.; Hugo, M.; Jung, T.; Bulteau, A.L.; Grune, T.; Hohn, A. Mitochondrial contribution to lipofuscin formation. Redox biology 2017, 11, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasiak, J. Senescence in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 2020, 77, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, L.D.; Narita, M. Autophagy at the intersection of aging, senescence, and cancer. Molecular Oncology 2022, 16, 3259–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Hyttinen, J.; Ryhanen, T.; Viiri, J.; Paimela, T.; Toropainen, E.; Sorri, I.; Salminen, A. Mechanisms of protein aggregation in the retinal pigment epithelial cells. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2010, 2, 1374–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli, G.; Cenci, S. Autophagy and Protein Secretion. J Mol Biol 2020, 432, 2525–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.S.; Lin, S.; Copland, D.A.; Dick, A.D.; Liu, J. Cellular senescence in the aging retina and developments of senotherapies for age-related macular degeneration. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Kim, C. Nutlin-3a for age-related macular degeneration. Aging 2022, 14, 5614–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, P.G.; Reddy, S.T.; Hinton, D.R.; Kannan, R. Mechanisms of RPE senescence and potential role of αB crystallin peptide as a senolytic agent in experimental AMD. Experimental eye research 2022, 215, 108918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valapala, M.; Wilson, C.; Hose, S.; Bhutto, I.A.; Grebe, R.; Dong, A.; Greenbaum, S.; Gu, L.; Sengupta, S.; Cano, M.; et al. Lysosomal-mediated waste clearance in retinal pigment epithelial cells is regulated by CRYBA1/βA3/A1-crystallin via V-ATPase-MTORC1 signaling. Autophagy 2014, 10, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Malavé, V.; González-Zamora, J.; de la Puente, M.; Recalde, S.; Fernandez-Robredo, P.; Hernandez, M.; Layana, A.G.; Saenz de Viteri, M. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Age Related Macular Degeneration, Role in Pathophysiology, and Possible New Therapeutic Strategies. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kheitan, S.; Minuchehr, Z.; Soheili, Z.S. Exploring the cross talk between ER stress and inflammation in age-related macular degeneration. PloS one 2017, 12, e0181667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, K.R.; Riaz, T.A.; Kim, H.-R.; Chae, H.-J. The aftermath of the interplay between the endoplasmic reticulum stress response and redox signaling. Experimental & molecular medicine 2021, 53, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmetti, V.; De Rosa, P.; Torosantucci, L.; Marini, E.S.; Romagnoli, A.; Di Rienzo, M.; Arena, G.; Vignone, D.; Fimia, G.M.; Valente, E.M. PINK1 and BECN1 relocalize at mitochondria-associated membranes during mitophagy and promote ER-mitochondria tethering and autophagosome formation. Autophagy 2017, 13, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; DuPont, N.; Castillo, E.F.; Deretic, V. Secretory versus degradative autophagy: unconventional secretion of inflammatory mediators. J Innate Immun 2013, 5, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armento, A.; Ueffing, M.; Clark, S.J. The complement system in age-related macular degeneration. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2021, 78, 4487–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintani, T.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2004, 306, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Q.; Shen, M.; Xiao, M.; Liang, J.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, M.; Wang, F.; Luo, X.; Sun, X. 3-Methyladenine Alleviates Experimental Subretinal Fibrosis by Inhibiting Macrophages and M2 Polarization Through the PI3K/Akt Pathway. Journal of ocular pharmacology and therapeutics: the official journal of the Association for Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2020, 36, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, P.; Li, J.; Chen, P.; Zheng, J.; Qian, Z. Autophagy inhibition potentiates the anti-EMT effects of alteronol through TGF-β/Smad3 signaling in melanoma cells. Cell death & disease 2020, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-T.; Liu, H.; Mao, M.-J.; Tan, Y.; Mo, X.-Q.; Meng, X.-J.; Cao, M.-T.; Zhong, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Shan, H.; et al. Crosstalk between autophagy and epithelial–mesenchymal transition and its application in cancer therapy. Molecular cancer 2019, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundamaraju, R.; Lu, W.; Paul, M.K.; Jha, N.K.; Gupta, P.K.; Ojha, S.; Chattopadhyay, I.; Rao, P.V.; Ghavami, S. Autophagy and EMT in cancer and metastasis: Who controls whom? Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2022, 1868, 166431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. The role of epithelial–mesenchymal transition and autophagy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma invasion. Cell death & disease 2023, 14, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Wang, Y. Autophagy in pulmonary fibrosis: friend or foe? Genes & diseases 2022, 9, 1594–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.L.; Zhang, M.Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Fang, L.J.; Qu, Y.Q. The role of autophagy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapies. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2022, 16, 17534666221140972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Baek, A.R.; Lee, J.H.; Jang, A.S.; Kim, D.J.; Chin, S.S.; Park, S.W. IL-37 Attenuates Lung Fibrosis by Inducing Autophagy and Regulating TGF-β1 Production in Mice. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 2019, 203, 2265–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, T.; Liu, W.; Yao, P. Autophagy, an important therapeutic target for pulmonary fibrosis diseases. Clinica Chimica Acta 2020, 502, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J. Preparation, culture, and immortalization of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 2005, Chapter 28, Unit 28.21. [CrossRef]

- Nitta, A.; Hori, K.; Tanida, I.; Igarashi, A.; Deyama, Y.; Ueno, T.; Kominami, E.; Sugai, M.; Aoki, K. Blocking LC3 lipidation and ATG12 conjugation reactions by ATG7 mutant protein containing C572S. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2019, 508, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Q.; Feng, Y.; Ma, M.; Guo, W.; Dong, X.; Deng, C.; Li, C.; Song, X.; et al. Autophagy resists EMT process to maintain retinal pigment epithelium homeostasis. International Journal of Biological Sciences 2019, 15, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scatena, R.; Bottoni, P.; Giardina, B. Circulating tumor cells and cancer stem cells: A role for proteomics in defining the interrelationships between function, phenotype and differentiation with potential clinical applications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2013, 1835, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhang, H.; Ye, J. KRT8 phosphorylation regulates the epithelial–mesenchymal transition in retinal pigment epithelial cells through autophagy modulation. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2020, 24, 3217–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Shang, P.; Terasaki, H.; Stepicheva, N.; Hose, S.; Yazdankhah, M.; Weiss, J.; Sakamoto, T.; Bhutto, I.A.; Xia, S.; et al. A Role for βA3/A1-Crystallin in Type 2 EMT of RPE Cells Occurring in Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2018, 59, Amd104–amd113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, S.; He, C.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y. Autophagy regulates TGF-β2-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in human retinal pigment epithelium cells. Molecular medicine reports 2018, 17, 3607–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbin, M.A. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill.: 1960) 2004, 122, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booij, J.C.; Baas, D.C.; Beisekeeva, J.; Gorgels, T.G.; Bergen, A.A. The dynamic nature of Bruch’s membrane. Progress in retinal and eye research 2010, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, D.S.; Grebe, R.; Bhutto, I.; Merges, C.; Baba, T.; Lutty, G.A. Relationship between RPE and Choriocapillaris in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2009, 50, 4982–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M.; Lu, F.; Rao, M.; Leach, L.L.; Gross, J.M. The retinal pigment epithelium: Development, injury responses, and regenerative potential in mammalian and nonmammalian systems. Progress in retinal and eye research 2021, 85, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migneault, F.; Hébert, M.J. Autophagy, tissue repair, and fibrosis: a delicate balance. Matrix Biol 2021, 100-101, 182-196. [CrossRef]

- Neill, T.; Kapoor, A.; Xie, C.; Buraschi, S.; Iozzo, R.V. A functional outside-in signaling network of proteoglycans and matrix molecules regulating autophagy. Matrix Biol 2021, 100-101, 118-149. [CrossRef]

- Neill, T.; Schaefer, L.; Iozzo, R.V. Decoding the Matrix: Instructive Roles of Proteoglycan Receptors. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 4583–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, L.; Tredup, C.; Gubbiotti, M.A.; Iozzo, R.V. Proteoglycan neofunctions: regulation of inflammation and autophagy in cancer biology. Febs j 2017, 284, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, L.E.; Weinberg, S.H.; Lemmon, C.A. Mechanochemical Signaling of the Extracellular Matrix in Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2019, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Cai, Y.; Huang, J.; He, X.; Han, W.; Chen, W. Impairment of autophagy promotes human conjunctival fibrosis and pterygium occurrence by enhancing the SQSTM1-NF-κB signaling pathway. Journal of molecular cell biology 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.J.; Rong, S.S.; Xu, Y.S.; Zheng, L.B.; Qiu, W.Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.J.; Duan, R.P.; Tian, T.; Yao, Y.F. Anti-fibrosis potential of pirarubicin by inducing apoptotic and autophagic cell death in rabbit conjunctiva. Experimental eye research 2020, 200, 108215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Fan, W.; Rokohl, A.C.; Ju, S.; Ju, X.; Guo, Y.; Heindl, L.M. Recent advances in graves ophthalmopathy medical therapy: a comprehensive literature review. International Ophthalmology 2023, 43, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.E.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoon, J.S.; Ko, J. Role of Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1 and Autophagy in the Pro-Fibrotic Mechanism Underlying Graves’ Orbitopathy. Yonsei Med J 2024, 65, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.M.; Jeyabalan, N.; Tripathi, R.; Panigrahi, T.; Johnson, P.J.; Ghosh, A.; Mohan, R.R. Autophagy in corneal health and disease: A concise review. Ocul Surf 2019, 17, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.W.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.N.; Zhang, X.Y.; Song, S.Q.; Gong, S.Y.; Meng, L.Y.; Gan, C.; Liu, B.J.; Gong, Q. Effects of autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine on a diabetic mice model. International journal of ophthalmology 2023, 16, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasiak, J.; Koskela, A.; Pawlowska, E.; Liukkonen, M.; Ruuth, J.; Toropainen, E.; Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Viiri, J.; Eriksson, J.E.; Xu, H.; et al. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Senescence in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium of NFE2L2/PGC-1α Double Knock-Out Mice. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.C.; Joud, H.; Sun, M.; Avila, M.Y.; Margo, C.E.; Espana, E.M. Keratocyte-Derived Myofibroblasts: Functional Differences With Their Fibroblast Precursors. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2023, 64, 9–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, L.; Dikic, I. Autophagy: Instructions from the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biology 2021, 100-101, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- García-Onrubia, L.; Valentín-Bravo, F.J.; Coco-Martin, R.M.; González-Sarmiento, R.; Pastor, J.C.; Usategui-Martín, R.; Pastor-Idoate, S. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlander, M. Fibrosis and diseases of the eye. The Journal of clinical investigation 2007, 117, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.R.; Hanumunthadu, D. Inflammatory eye disease: An overview of clinical presentation and management. Clin Med (Lond) 2022, 22, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehender, A.; Li, Y.-N.; Lin, N.-Y.; Stefanica, A.; Nüchel, J.; Chen, C.-W.; Hsu, H.-H.; Zhu, H.; Ding, X.; Huang, J.; et al. TGFβ promotes fibrosis by MYST1-dependent epigenetic regulation of autophagy. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy participates in, well, just about everything. Cell Death & Differentiation 2020, 27, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollari, V.; Reay, M.; Leino, L.; Assmuth, T.; Wirman, L.; Toropainen, E.; Kaarniranta, K. Preclinical in vivo tolerability assessment of silica as an intravitreal drug delivery vehicle. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2024, 65, 6118–6118. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).