3.1. Yellow Rust Prediction

The performance metrics of six different ML models: ANN, LASSO, Ridge regression, ENET, GBR and RF, to evaluate the impact of meteorological variables on disease severity of yellow rust in wheat are presented in

Table 5. The metrics used for assessment include Training RMSE, Training Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Training R-squared (r

2) and Training Efficiency (EF), Testing RMSE, Testing MAE, Testing R-squared, and Testing EF.

The results showed R2 between weather parameter and disease severity are strongly correlated with values of 0.96 and 0.93 respectively obtained in calibration and for validation sets. Moreover, the lowest RMSE with 6.38 and 10.96 was obtained during calibration and validation, respectively. The MAE value of 4.77 for calibration and 6.92 for validation envisaged that ANN showed robustness in disease prediction accuracy. Similarly, the RF model also demonstrates excellent performance with R2 values of 0.96 for calibration and 0.92 for validation, and RMSE (5.91 for calibration and 10.93 for validation) and MAE (4.48 for calibration and 7.58 for validation), confirming the RF reliability in disease prediction using climatic variables. Moreover, the Elastic Net, Lasso and Ridge models exhibited moderate to lower predictive performance with lower R2 values and higher RMSE and MAE, revealing lesser accuracy among the models. The GBM model revealed high R2 of 0.94 shows overfitting potential but showed least R2 of 0.88. The EF values further validate these findings, highlighting ANN and RF are efficient models with EF values of 0.96 and 0.97 for calibration, and 0.88 and 0.88 for validation, respectively. The ANN and RF models is most effective and accurate for predicting yellow rust in wheat, while ANN is slightly outperforming than RF in overall evaluation metrics.

The feature importance for predicting yellow rust in wheat using various machine learning models presented in

Figure 4. For the Ridge model, evapotranspiration and wind velocity are identified as the most significant predictors, followed by rainfall and relative humidity. The Random Forest model highlights evapotranspiration as the dominant predictor with a substantial margin, followed by Tmax and SSH. The Lasso model also underscores the importance of evapotranspiration and wind velocity, with RHII and rainfall being moderately important. The Elastic Net model aligns closely with Lasso, showing a strong emphasis on evapotranspiration, followed by wind velocity and RHII. In the ANN model, evapotranspiration and wind velocity are most important, with minimum temperature, SSH, and rainfall contributing significantly as well. Finally, the GBM model, represented by relative influence (rel.inf), places the highest importance on evapotranspiration, followed by Tmax and Tmin, indicating a similar pattern of critical features. Across all models, evapotranspiration consistently emerges as the most critical feature, highlighting its pivotal role in predicting yellow rust in wheat. Wind velocity and temperature variables (Tmax and Tmin) also appear prominently across different models, suggesting their relevance in influencing the disease prediction. This comprehensive analysis of feature importance across diverse models underscores the critical environmental variables that need to be monitored for effective yellow rust prediction in wheat.

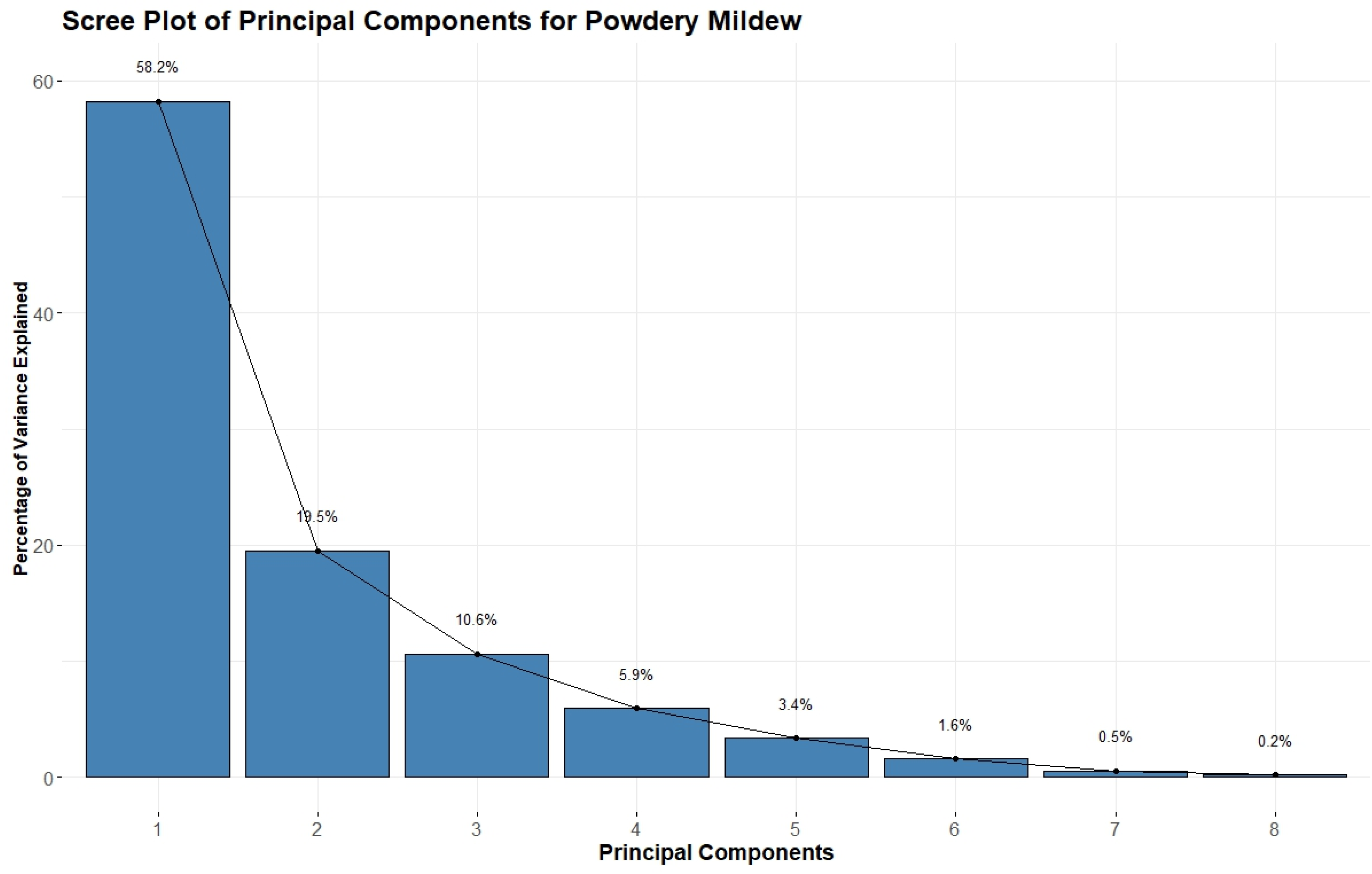

3.2. Powdery Mildew Prediction

The

Table 6 presents the performance of various machine learning models in predicting powdery mildew of wheat. The ANN model demonstrated exceptional performance, with an R-squared value of 0.98 and 0.95 for the calibration and validation sets, respectively. It exhibited relatively low RMSE values of 4.98 and 6.98, along with nRMSE values of 5.24 and 7.35, and MAE values of 3.32 and 4.98 for the calibration and validation sets, respectively. The EF values were also high at 0.98 and 0.95, indicating excellent model efficiency. The GBM model also showed promising results, with an R-squared of 0.98 and 0.90, RMSE of 0.15 and 0.30, nRMSE of 5.28 and 10.86, MAE of 0.10 and 0.22, and EF of 0.98 and 0.89 for the calibration and validation sets, respectively. The RF model performed similarly well, with an R-squared of 0.98 and 0.90, RMSE of 4.52 and 10.60, nRMSE of 4.75 and 11.16, MAE of 2.82 and 6.85, and EF of 0.98 and 0.89 for the calibration and validation sets, respectively.

On the other hand, the Elastic Net, Lasso, and Ridge Regression models exhibited relatively lower performance. The Elastic Net model had an R-squared of 0.77 and 0.95, RMSE of 16.35 and 6.98, nRMSE of 17.21 and 7.35, MAE of 13.46 and 4.98, and EF of 0.77 and 0.95 for the calibration and validation sets, respectively. The Lasso model showed consistent performance with an R-squared of 0.77 and 0.74, RMSE of 16.38 and 16.36, nRMSE of 17.24 and 17.22, MAE of 13.54 and 14.55, and EF of 0.77 and 0.73 for the calibration and validation sets, respectively. The Ridge Regression model had an R-squared of 0.74 and 0.73, RMSE of 17.41 and 16.69, nRMSE of 18.32 and 17.57, MAE of 14.66 and 14.24, and EF of 0.74 and 0.72 for the calibration and validation sets, respectively.

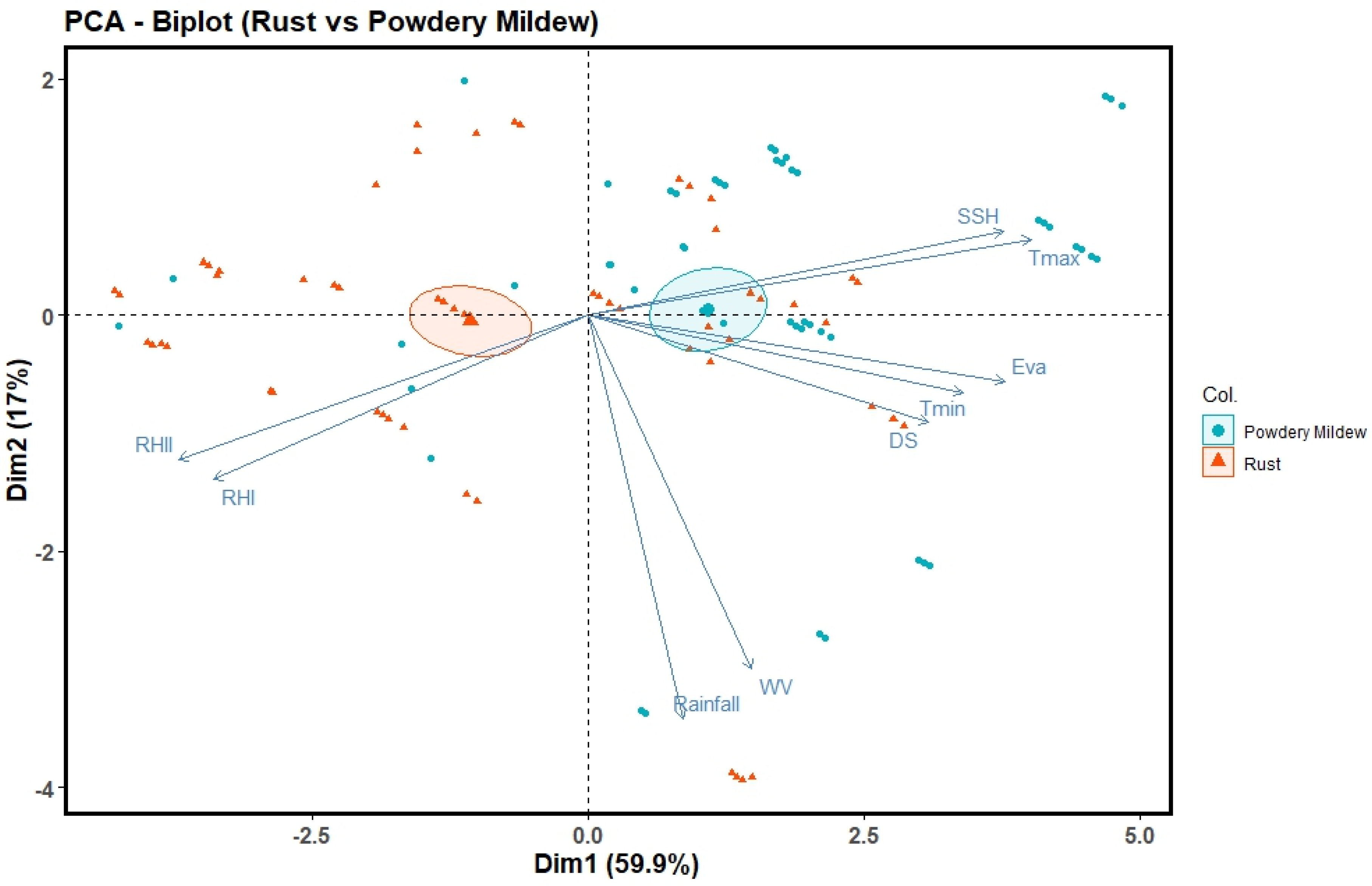

The variable importance plot (

Figure 5) provide valuable insights into the relative importance of various meteorological factors in modeling powdery mildew in wheat, allowing for better understanding and potential improvements in the prediction models. For the Ridge Regression, the most important variables are relative humidity, Tmin, rainfall, SSH, and Tmax. The Random Forest model assigns high importance to Tmin, Tmax, relative humidity, Eva, and SSH. The Lasso Regression model highlights Tmax, Tmin, relative humidity, SSH, and rainfall as the top influential variables. The Elastic Net model also identifies Tmin, relative humidity, SSH, rainfall, and Eva as the most critical factors.

The ANN model reveals that Tmin, SSH, WV, relative humidity, rainfall, Eva, and Tmax are the most significant variables for predicting powdery mildew. The variable importance plot indicates, GBM model assign importance to Tmin, relative humidity, Tmax, SSH, and Eva as crucial predictors of powdery mildew based on the collective importance assigned by multiple machine learning models, the key factors that appear to be most influential for predicting powdery mildew in wheat are Tmin, relative humidity, rainfall and sunshine hours.

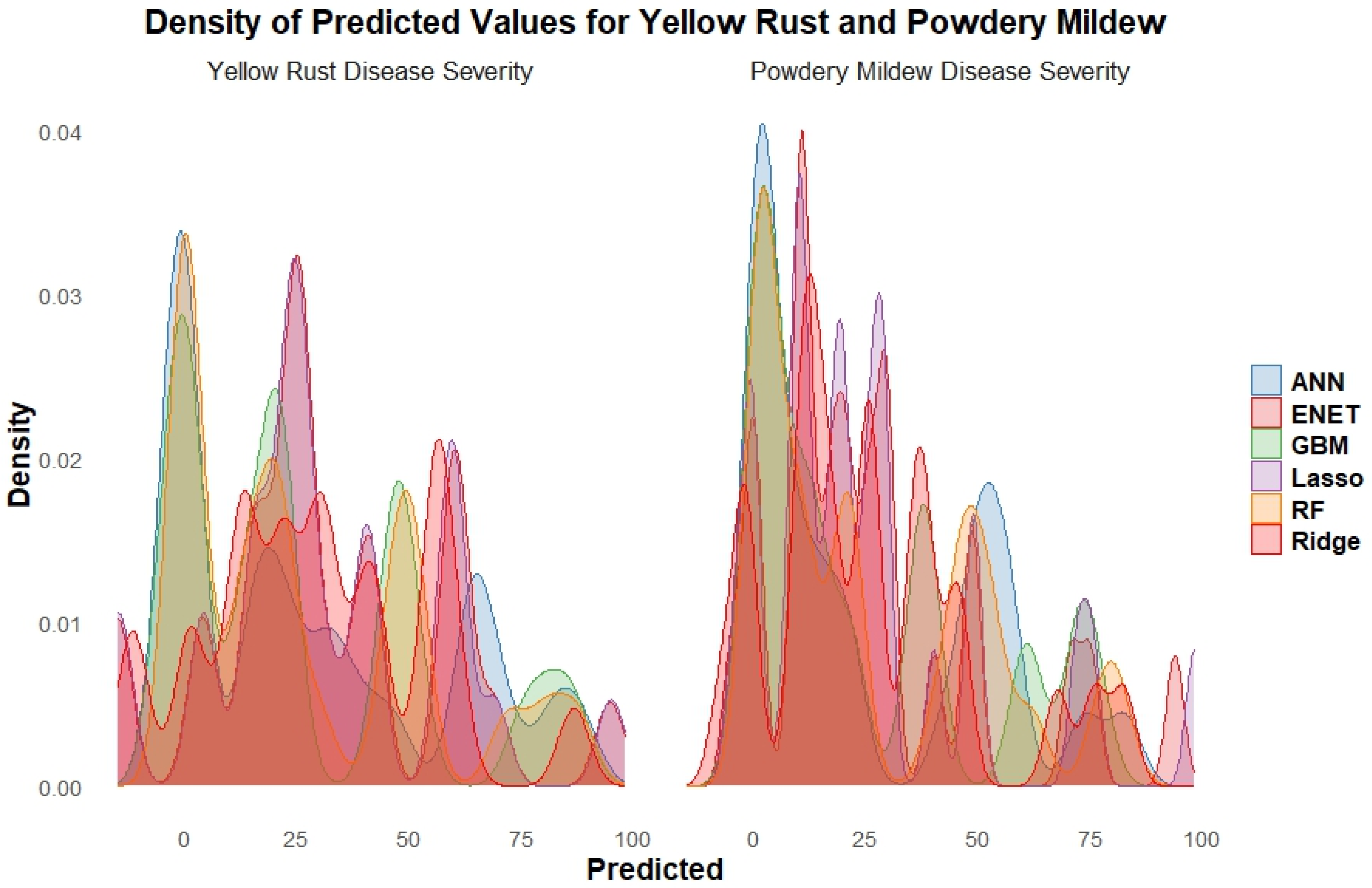

The density distributions of predicted values for yellow rust and powdery mildew disease severity in wheat, obtained from various machine learning models (

Figure 6). Density distributions plot for yellow rust showed multiple peaks signifying that the models predict varying levels of disease severity. The ANN and Ridge models exhibited distinct dense peaks at certain severity values, while other models such as Elastic Net, GBM, Lasso, and RF showed more dispersed distributions with several local peaks. For powdery mildew density distribution pattern is concentrated with higher peaks indicating that the models tend to predict specific severity levels more frequently. The ANN and Ridge models revealed sharper peaks are indicating more consistent predictions, while the other models show slightly broader distributions with multiple local maxima. The multi-modal distributions indicate that most models predict a range of severity levels, with some models exhibiting a tendency to predict specific severity levels more frequently than others.

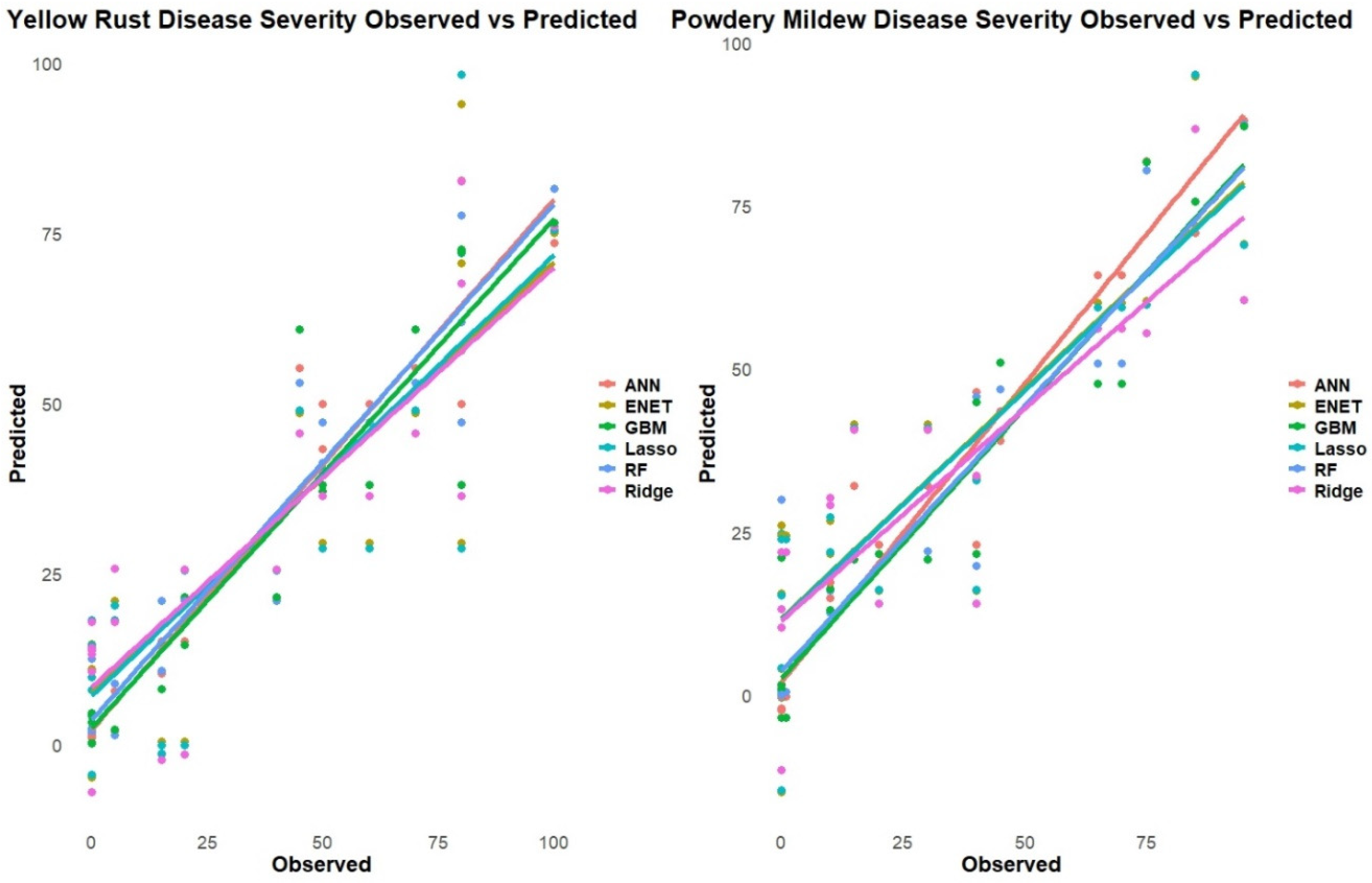

The figure (

Figure 7) presents a scatter plot comparison between the observed and predicted values of disease severity for yellow rust and powdery mildew in wheat, obtained from various machine learning models. For yellow rust disease severity, the scatter points align closely along the diagonal line, indicating a good agreement between the observed and predicted values across the different models. The points are evenly distributed, suggesting that the models can accurately predict disease severity levels across the entire range of observed values. However, there are a few outliers where the predicted values deviate from the observed ones.

In the case of powdery mildew disease severity, the scatter points also follow the diagonal line reasonably well, implying that the models can capture the observed disease severity levels to a good extent. Nevertheless, there appears to be slightly more deviation from the diagonal, particularly at higher severity levels, where some models tend to overpredict or underpredict the observed values. Additionally, there are more scattered outliers compared to the yellow rust plot, indicating instances where the models struggle to accurately predict the powdery mildew severity.

Overall, the scatter plots provide a visual assessment of the model performance, allowing for the identification of potential biases or discrepancies between the observed and predicted values. While both diseases exhibit a satisfactory agreement, the powdery mildew plot suggests slightly more challenges in predicting disease severity accurately, especially at higher severity levels, compared to yellow rust.

Regression Models

The regression equations (

Table 7) provide insights into the relationships between meteorological factors and the severity of yellow rust disease, enabling better understanding and potential improvements in disease prediction and management strategies.

Regression equation obtained from ENET suggests that the severity of yellow rust is positively influenced by Eva, WV, rainfall, and sunshine hours, while it is negatively affected by maximum relative humidity (RHII). Similar to the Elastic Net equation, the Lasso regression equation shows a positive relationship between disease severity and Eva, WV, and rainfall, while relative humidity has a negative impact. The Ridge regression equation also exhibits positive coefficients for Eva, WV, rainfall, and Tmax, suggesting that higher values of these variables are associated with increased yellow rust severity.

The regression equations obtained from different machine learning models for predicting the severity of powdery mildew disease in wheat is presented in

Table 8. Regression equation obtained for ENET suggest that the severity of powdery mildew is negatively influenced by maximum temperature and relative humidity (RHI and RHII), while it is positively related to Tmin and sunshine hours. Similar to the Elastic Net equation, the Lasso regression equation shows a negative relationship between disease severity and Tmax and relative humidity, while Tmin and sunshine hours have a positive impact. Additionally, the Lasso model includes rainfall as a significant predictor, with a positive coefficient indicating that higher rainfall is associated with increased powdery mildew severity. The Ridge regression equation also exhibits a negative coefficient for maximum relative humidity (RHI) and Tmax. On the other hand, Tmin, rainfall, and sunshine hours have positive coefficients.

Based on the regression equations and variable importance plots, there are some notable differences in the influential variables for predicting yellow rust and powdery mildew severity in wheat. Eva and WV emerge as significant positive predictors across the Elastic Net, Lasso, and Ridge regression equations, rainfall also has a positive coefficient. On the other hand, for powdery mildew prediction temperature variables (Tmax and Tmin) play a crucial role. This suggests that higher maximum temperatures may suppress powdery mildew development, while higher minimum temperatures could promote disease severity. Additionally, the variable importance plots further highlight the differences in influential factors for the two diseases. For yellow rust, variables like Eva, WV, and rainfall appear to be more important, whereas for powdery mildew, temperature variables (minimum and maximum temperatures), relative humidity, and sunshine hours are among the top influential factors. These differences in the significant predictors and their relationships with disease severity suggest that the environmental conditions favoring the development and spread of yellow rust and powdery mildew may differ. This insight can be valuable for targeted disease management strategies and for understanding the unique environmental requirements of each disease.

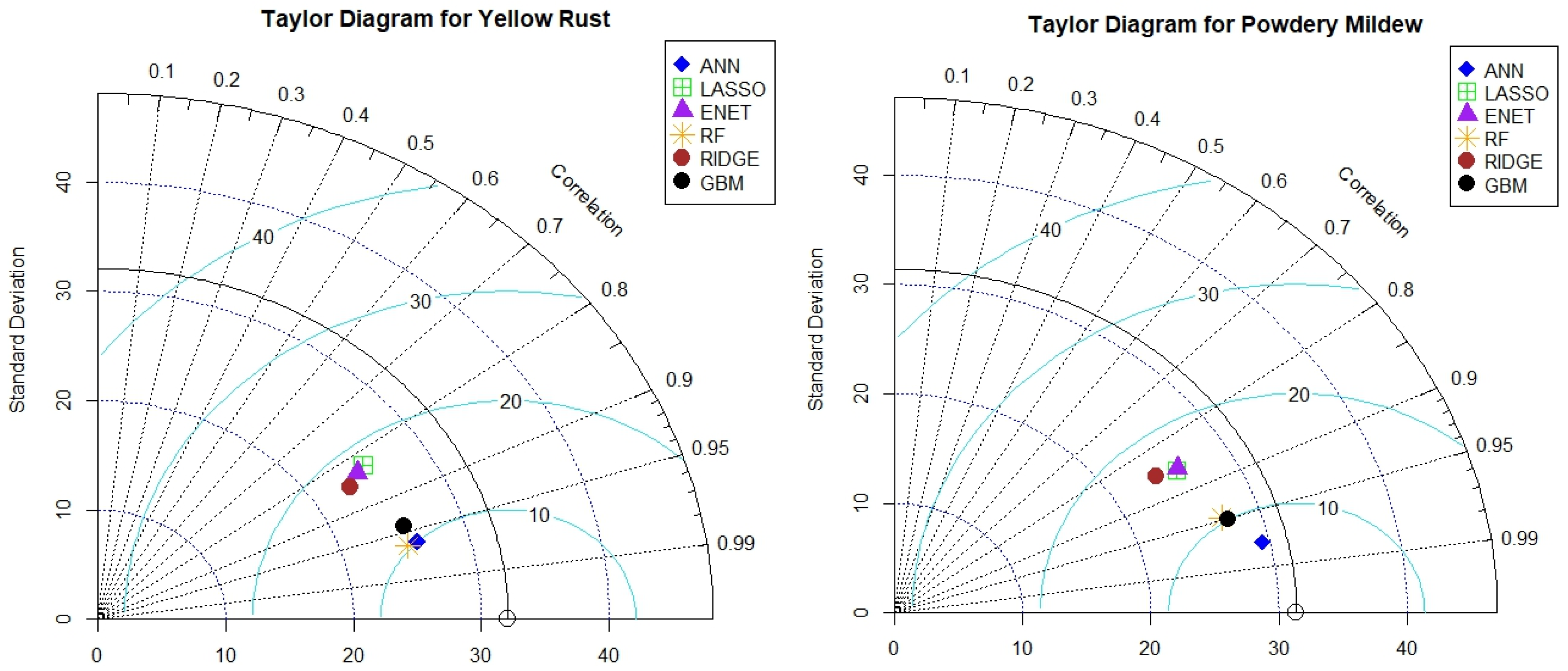

Taylor diagram obtained for yellow rust predictions, the ANN and Lasso models demonstrate the highest correlation with the observed data, followed by the ENET, RF, Ridge, and GBM models. The ANN model again exhibits the lowest centered root mean square error (CRMSE), suggesting superior performance in predicting yellow rust severity compared to the other models. In the case of powdery mildew predictions, the ANN and RF models show the highest correlation with the observed data, followed by the Lasso, ENET, Ridge, and GBM models. The ANN model exhibits the lowest CRMSE, indicating the best overall performance among the evaluated models (

Figure 8).