1. Introduction

Screening programs for Cardiovascular Heart Disease (CVD) in childhood aim to detect the presence of previously undiagnosed structural (Congenital Heart Disease-CHD) or arrhythmogenic diseases potentially associated with sudden cardiac death (SCD), as well as of risk factors of late onset adult heart disease (such as coronary artery disease and hypertension), with increasing morbidity and mortality worldwide [

1], due an increasing impact of related risk factors already from a younger age [

2]. Early detection of adult CVD risk factors offers the potential of early lifestyle modifications [

3]. Most screening programs in childhood and adolescence focus on the detection of CVD associated with SCD in specific pediatric populations such as athletes, due to an increased health risk if undiagnosed [4-6]. Large scale CVD screening programs in unselected pediatric populations, although offer a potential benefit for all children [

7,

8], require further evaluation due to the rarity of inherited and arrhythmogenic HD in the pediatric population [

9], before their large scale application.

The present study reports the results of the only CVD screening program in Greece in unselected pediatric population (primary school children) evaluated by use of personal and family history questionnaire, clinical evaluation (including digital phonocardiography) and 12-lead ECG recording. Our study findings are presented within the context of detailed literature review regarding CVD screening in children.

2. Materials and Methods

Prospective study, with voluntary participation of 3rd grade primary school children (8-9 years old) in the region of Crete, Greece, over 6 years (2018-2024). The study protocol has been approved by 7th Health District Authority (Region of Crete), Hellenic Ministry of Health (532/2.8.2017 and 38890/20.9.2021) and complies with Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.Informed written consent by parents was obtained for the evaluation of participant children at regional public health facilities, after their daily school program.

2.1. Study participants

A random sample of 150 schools (48% of total) was selected, representing both rural (n=102) and urban (n=38) regional areas of the island, with a total number of 2.500 third-grade school children being eligible for participation. Parents were provided in advance informative material regarding the aims of the study with the support of local school authorities. The evaluation of children was performed following informed written consent by their parents at regional public health facilities, following completion of their daily school program.

2.2. Research group

The research group performing the primary CVD screening at the local health facilities included a pediatrician with expertise in pediatric cardiology (primary investigator A.B), assisted by medical personel or nurses having completed certified training in pediatric cardiac auscultaton and pediatric ECG interpretation [

10]. The final diagnostic evaluation, for children having referral indication following primary CVD screening, has been performed in the local tertiary referal center (Pediatric Cardiology Unit, Dpt of Pediatrics, University Hospital of Heraklion, by a single academic pediatric cardiolgist (I.G).

2.3. CVD screening implementation

2.3.1. Phase I. Primary CVD screening

A comprehensive CVD screening has been performed, including history, physical evaluation and 12-lead ECG recording as following:

A. Personal and family CVD history questionnaire

A specifically designed questionnaire sheet, based on preparticipation screening guidelines [

4,

12] was completed by parents. Personal history included presence of symptoms such as exercise intolerance, thoracic pain and perception of palpitations, history of syncope, or presence of further health issues. Family history included sudden death in family members at a young age (<50 years), congenital or inherited CVD (cardiomyopathy/channelopathy). Positive responses were further clarified through an interview of parents by the primary investigator at the time of child’s primary evaluation.

B. Physical evaluation

Body Size. Weight (kg) and Height (cm) measurements were performed, with body mass index (BMI) estimation (BMI= kg/m

2) and BMI percentile classification [

13]. Obesity was documented as BMI ≥95

th percentile.

Blood Pressure. Systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure was measured using an oscillometric sphygmomanometer (Dinamap Pro Care 400 GE Medical Systems, Germany) and appropriately-sized cuff. BP category according to the sex, age, and height was documented [

14]. Children with BP values ≥ 90th percentile were reevaluated repeatedly on the same day to verify measurements; femoral pulses have been evaluated in all children. Stage 1 hypertension was documented in cases of average SBP and/or DBP > 95th percentile [

14].

Phenotype: The presence of clinical features suggestive of genetic conditions potentially associated with increased CVD risk (Marfan / Noonan syndrome, hyperelasticity syndrome) were documented [

12].

Cardiac auscultation: Conventional cardiac auscultation including dynamic auscultation (in lying and standing position) was performed for documenting the presence of a murmur (classified as innocent or abnormal) or click, detection of heart tone abnormalities, or arrhythmia (other than respiratory) [

12].

Digital Phonocardiography. A series of 5 digital phonocardiogram recordings corresponding to the 4 standard cardiac auscultation positions and fossa jugularis was recorded in each patient, by using a sensor based electronic stethoscope with incorporated synchronous 3-channel ECG recording (TheStethoscope®; Welch Allyn-Meditron, Welch Allyn Inc., NY, USA) as previously described [

15]. A designated software (Meditron Analyzer 4®) was used for data storing on a personal PC and for their off-line evaluation [

15].

12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). A standard 12-lead ECG was recorded along with a printout of auto-measurements of intervals and individual leads’ amplitudes [

16].

2.3.2. Phase II. Data verification

Cases with a negative personal and family history having an otherwise normal physical evaluation and 12-lead ECG interpretation as evaluated by the primary investigator during Phase I evaluation, received a health clearance certificate. Phase II data validation included the confirmation of history responses, along with the expert validation of ambiguous cardiac auscultation findings and ECG recordings. Digital phonocardiogram findings were off-line evaluated and confirmed by an expert [

15] while the use of an Electronic Health Record with computerized decision support tools (EHR- CDSS), specifically designed for our research program purposes [

17] provided further assistance in the interpretation of ECG measurements along with expert final confirmation. Cases with Phase II verified referral indication were offered an appointment in the tertiary referral center according to findings (latest within a 3 month period).Main referral indications included a) Verified positive history responses b) Abnormal physical evaluation findings (including hypertension, adiposity, phenotypic features and abnormal auscultatory findings other than respiratory arrhythmia, respiratory S2 split and innocent heart murmur) c) 12-lead ECG abnormalities such as Left axis deviation, Right axis deviation, Right ventricular hypertrophy, Left ventricular hypertrophy, Right/left atrial enlargement, Ventricular ectopic beats, pathologic Q waves, ST-T changes, T waves inversion, QTc prolongation > 460 ms, Pre-excitation pattern, Atrioventricular block 1st – 3rd degree, Complete Right bundle branch block, Low atrial rhythm, in accordance with prior used criteria in pediatric ECG screening programs [

7,

11]. A dominant referral indication was documented in cases with multiple indications, corresponding to the one considered having the highest probable association with the presence of CVD, according to investigators.

2.3.3. Phase III. Tertiary center evaluation

A complete transthoracic echocardiographic study and a repeated 12-lead ECG were performed and evaluated by an expert pediatric cardiologist (I.G), along with physical evaluation and re-confirmation of history responses. Further imaging methods (CMR, chest radiography), 24 hour ECG ambulatory monitoring, standard blood chemical analysis and genetic evaluation were performed as indicated. A further referral for invasive diagnosis or electrophysiology study was considered in selected cases. Cases whose symptoms were considered being of non-cardiac origin were referred to further pediatric sub-specialties acccordingly.

2.4. Statistical methods.

Baseline characteristics were presented in absolute as count and relative frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were reported as median, mean and interquartile range. Chi-square test with continuity correction was used to examine the association between categorical variables. Differences in percentages were tested using Fisher’s exact test. Reported

p values were based on two-sided tests and

p values < 0.05 were considered

statistically significant. C.I. were calculated by a web- calculator (

https://sample-size.net/confidence-interval-proportion/)

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total number of 944 children (boys 49.6%, girls 50.4%) 8-9 years old (mean age 8.5 years) participated (37% of the eligible population), 622 (66%) of rural / suburban and 322 (34%) of urban residence.

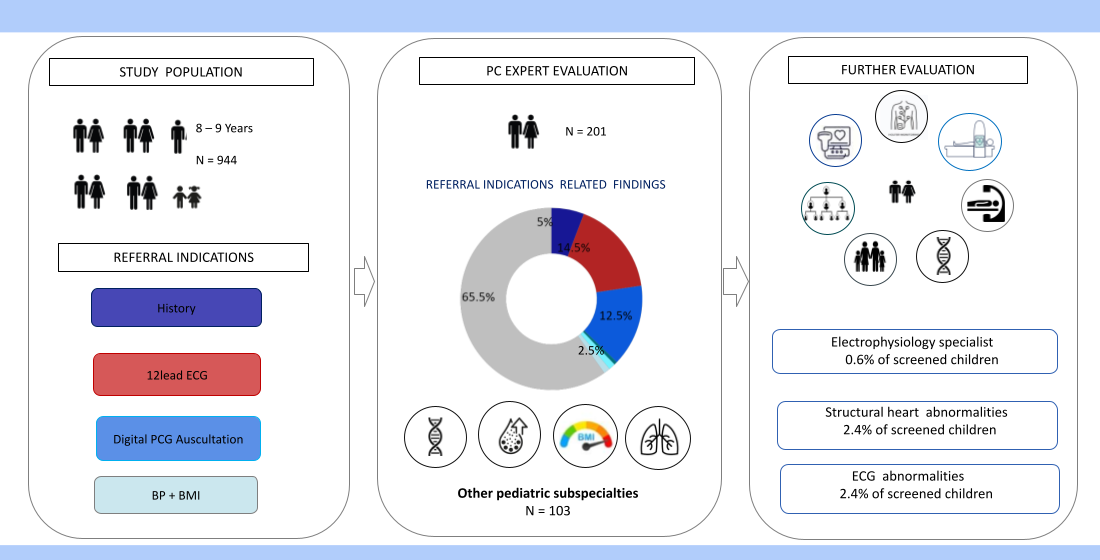

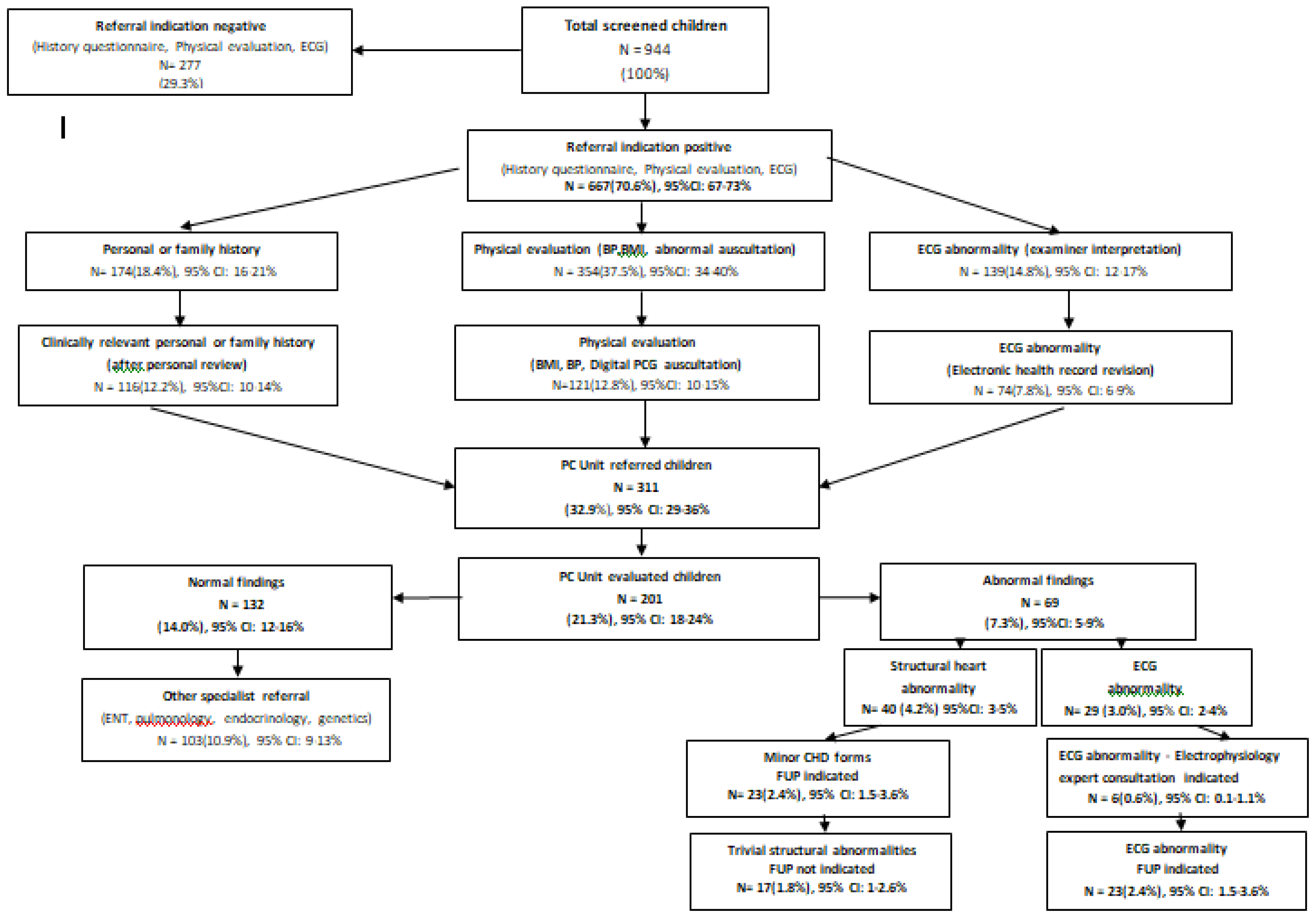

3.2. Referral indications

The results of the CVD screening program in children regarding referral indications and final diagnosis (Phase I -III) are summarized as a flow diagram on

Figure 1.

According to the initial unconfirmed documentation (phase I), 83.7% of screened children had at least one referral indication, with 10% having multiple indications. In descending order they included abnormal physical evaluation findings in 42.5%, (abnormal auscultation 28.2%, adiposity 10.8% and hypertension 3.2%), positive history responses in 26.4% (personal history 20.8%, family history 11.5%) and ECG abnormalities in 14.8%.

Following data validation (phase II) 311 children (32.9% of total) had a confirmed referral indication including, in descending order, abnormal physical findings 12.8%, (adiposity 6.3%, abnormal auscultation 3.9%, and hypertension 3.2%), positive history responses 12.2% (personal history 6%,family history 6.2%), and abnormal ECG 7.8%.

3.3. Outcomes

A final diagnostic evaluation (Phase III) was offered in 201 children (21.3% of total, 64.6 % of cases with confirmed referal indication). Of them 132 cases (14% of total) were diagnosed as normal, while in 103 (10.9%) a referral indication to other pediatric specialists was established (including ENT, pulmonology, endocrinology, genetics). A CVD diagnosis was first established in 69 children (7.3% of total, 34% of Phase II referrals), including a) structural heart abnormalities in 40 (4.2%), all of them corresponding to minor congenital heart disease forms (bicuspid aortic valve, atrial septal defect, coronary fistula, mitral valve prolapse, mild aortic arch hypoplasia/dilation, mitral valve regurgitation) with follow up indication in 23 cases (2.4%) and b) ECG abnormalities in 29 (3% of total), of them 6 cases (0.6% of total) having an indication for expert electrophysiology consultation and/or electrophysiology study (including pre-excitation (n=1), ventricular extrasystolic arrhythmia (n=4) and QTc prolongation (n=1) due to a novel KCNH2 pathogenic mutation detected in the child and family members following cascade screening.

3.4. Diagnostic yield of CVD screening components

Confirmed personal (6%) and family (6.2%) responses resulted in the diagnosis of mild, minor structural abnormalities (considered as incidental findings) in 3 (4.7%) and 7 cases (16%) of those evaluated (53-56%), respectively. While 13 (30%) of children with positive family history were considered as having some indication for long term follow up and/or cascade genetic screening, children with positive personal history (symptoms) were considered being of non-cardiac origin, with 82% requiring further non-cardiology consultation (mainly pulmonology and dietology-endocrinology). Confirmed abnormal auscultation (3.9%) resulted in positive echocardiographic findings in 70% of cases including minor CHD (32%) and incidental variants (38%) of those finaly evaluated (83%). 12-lead ECG confirmed abnormalities (7.8%), included 2 cases with potential association to SCD (0.2% of the total population) among those evaluated (93%).

3.5. Cost effectiveness

Main cost determinants include a) personnel (expertise, time) and b) material costs. For Phase I documentation, participation of nurses / paramedics can be sufficient, following structured teaching courses attendance [

18]. The average evaluation time / child was 10 min (range 8 -12 min), resulting in 1000 person-hours for the evaluation of the total reference population (n=6000). For Phase II medical personnel with expertise in pediatric cardiology is required in addition to secretarial assistance for EHR data entry. The average EHR documentation time of all CVD screening features was 6 min [

17] corresponding to 600 person-hours for the reference population. Expert off-line digital phonocardiogram interpetation/child was 2 minutes. Provided that 28% had positive auscultatory findings requiring validation, 56 expert-person-hours would be needed. Phase III evaluation was performed on average 20 minutes. As 37% of cased had a Phase II referral indication, 740 expert-person-hours would be required. By adding further transfer and subsistence costs, for performing the primary evaluation at local health stations, the total personnel cost approaches 40,000 €/year. Material costs including hardware/software and consumables is estimated at 10,000 €/year. The implementation of paperless documentation forms (such as designated apps) or computer based auto interpretation of pediatric ECGs and digital phonocardiograms [

19] could improve cost-effectiveness, however further data protection requirements and software cost should be also accounted for.

3.6. Comparison with previous studies.

Table 1 presents a summary of available studies regarding CVD screening in primary school children, including methodology, screening tools, diagnostic yield and cost-effectiveness when available.

4. Discussion

Early detection of CVD and related risk factors, already in childhood, is very important, as it allows early diagnosis, early treatment, preventive intervention and prevention of sudden cardiac death. The CVD screening program for primary school children in the Health Region of Crete, represents one of the few structured programs targeting school age children. This program is unique in terms of incorporating all available screening tools (including 12-lead ECG and digital phonocardiography) with data interpretation based on certified personel [

10] and use of designated EHR-CDDS for data entry and processing [

17].

As CVD affecting children differs from adult CVD, characterized by a predominance of congenital heart disease (CHD) and rare forms of inherited cardiomyopathies/channelopathies in children [

9] versus coronary artery disease (CAD) predominance in adults, CVD screening programs for children should be adapted accordingly, regarding both diagnostic targets and screening tools accordingly.

Undiagnosed CHD represents a rare (0.2%) cause of sudden cardiac death, with CHD affecting less than 1% of children [

20]. Structural heart disease diagnosis is mainly based on the pediatrician's clinical suspicion during routine evaluation / preparticipation screening or by the presence of symptoms (thoracic pain, easy fatigue, syncope etc.)[

21,

22]. The presence of a murmur in children represents a common referral indication for pediatric cardiology evaluation [

23]. However the majority corresponds to “innocent” murmurs [24-26] requiring no further evaluation other than expert auscultation [

27]. However, the differentiation of innocent from abnormal murmurs and the detection of additional sounds associated with CHD can be challenging for non-experts, requiring clinical expertise or structured teaching [

10]. Telemedicine applications [

15,

26,

28] or computer programs for automatic diagnosis and classification of cardiac sounds [

19] can help clinical decision making. In the present screening program digital phonocardiography (PCG) was applied based on our previous positive experience [

10,

15,

17,

18]. Following referral for abnormal auscultatory findings a diagnosis of structural heart disease in 40 children followed. Nearly half of them corresponded to minor CHD forms (such as bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) and small atrial septal defect (ASD2) not requiring any intervention. The detection rate of structural heart abnormalities in the present CVD screening program was comparable to the results of screening programs using digital PCG in China [

29], with variable detection rates depending on screening program methodology [

30].

(Table 1)

The detection of hereditary CVD including cardiomyopathies and chanellopathies in childhood presents further challenges, due to their rarity and the limited diagnostic value of physical evaluation in this setting [

31]. Accurate family history and the implementation and correct interpretation of pediatric 12-lead ECG are crucial for their early detection as they are associated with increased risk of SCD [

32,

33]. In our study personal and family history information with potential association with the above diagnoses was documented while 12-lead -ECG recording was also implemented. The detection of ECG abnormalities in 3% of screened children followed by further complex evaluation, correlates with the results of other schoolchildren screening programs in Europe [34-36] and in Asia [

8,

29]. (

Table 1) Significant ECG findings with potential association with increased SCD risk were documented in 0.2% of cases, with similar finding was reported in ECG screening program from Spain [

34].

An important goal of a CVD screening program in children is the early detection of risk factors associated adult onset CVD (such as CAD and hypertension). In the present study the prevalence of hypertension and adiposity was 3% and 10%, respectively. The global prevalence of pediatric primary hypertension is increasing, affecting up to 4 – 5 % of children [

37], and being linked to major cardiovascular events in adulthood [

38]. Over the last half century, the estimated worldwide prevalence of obesity has increased to around 6% in boys and 8% in girls [

39]. Childhood obesity (BMI>95th percentile) and overweight (BMI> 85th < 94th percentile) are known independent CVD risk factors, linked to other risk factors, such as elevated blood pressure [

40]. Early detection and intervention of identifiable CVD risk factors in childhood, represents a very important goal of any CVD screening program in childhood.

Finally, the present CVD screening program offered a unique chance of a general health evaluation of participant children as well, with the majority of referrals (13%) requiring further pediatric subspecialty care for their reported symptoms.

The cost - effectiveness of a CVD screening program in childhood should be viewed within the context of screening program goals (detection of risk factors, asymptomatic or symptomatic CVD), screening tools (history, physical evaluation, expert auscultation, 12-lead ECG) and available resources. The rarity of pediatric CVD cannot explain alone the limited available pediatric CVD screening programs (

Table 1); inborn error of metabolism and other diseases which are targets of established screening programs (in the neonatal period) are more rare than the life-threatening forms of inherited and arrhythmogenic pediatric heart disease [

9,

41]. Based on the present study findings, CVD screening programs in childhood can be highly cost effective in detecting CVD risk factors by using simple tools (weight, height, BP measurement)[

42]. The diagnosis of minor CHD-structural abnormalities (incidence 1%) was based solely on expert cardiac auscultation, requiring personnel training and /or digital phonocardiography implementation costs. The diagnosis of electrocardiographic abnormalities (incidence 3%) was based only on 12-lead- ECG implementation, requiring further training for pediatric ECG interpretation or auto-interpretation algorithms [

43]. Personal and family history responses, an integral part of preparticipation screening evaluation worldwide [

12] although easily obtained, they required expert confirmation while failed to document any diagnostic yield for CVD disease in the present study; small sample size could account for this finding. However positive history findings were very valuable for detecting children requiring further pediatric subspecialty evaluation as a cause of their symptoms, while positive responses of SCD in first degree family members represent an indication for family cascade screening, including family’s children.

Future CVD screening programs in children could greatly benefit from the advantages of artificial intelligence, ECG and phonocardiogram auto interpretation [19, 44] and the implementation of electronic health records with decision supported tools. Although we have extensively used digital phonocardiography and a designated EHR [

17,

19], the present study is still based on certified personnel participation for data sampling, confirmation and final diagnostic decision making [

18].

Study limitations

The present study findings should be viewed within the study limitations including a relative small sample size for rare form of pediatric CVD to be detected and the inclusion of a random sample of the reference population, with a subset of cases undergoing a final diagnostic evaluation. The applicability of the present study findings in other pediatric populations should also take into account geographical and ethnic differences in CVD prevalence [

9].

5. Conclusions

CVD screening programs in school children can be very helpful for the early detection of CVD risk factors and their general health assessment as well. Expert cardiac auscultation and 12-lead ECG allow for the detection of structural and arrhythmogenic heard disease, respectively. Further study is needed regarding the performance of individual components, accuracy of interpretation (including computer assisted diagnosis) and cost effectiveness, before large scale application of CVD screening in unselected pediatric populations.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and I.G.; methodology, all authors; software, I.G.; validation, F.P., G.C. and I.G.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, A.B.; resources. A.B; data curation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., I.G.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, I.G.; supervision, F.P., G.C., E.G., I.G.; project administration, all authors.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by theHellenic Ministry of Health, 7th Health District Authorities, Department of research and development approval 532/2.8.2017 and 38890/20.9.2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hellenic Ministry of Health, 7th Health District and all affiliated Hospitals and Primary Health Care authorities and personnel for their active support of the program. We would like to thank all school authorities and participant families.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Timmis A, Vardas P, Townsend N; et al. European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 716–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am CollCardiol 2020, 76, 2982–3012. [Google Scholar]

- Reis EC, Kip KE, Marroquin OC; et al. Screening children to identify families at increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1789–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams EA, Pelto HF, Toresdahl BG; et al. Performance of the American Heart Association (AHA) 14-Point Evaluation Versus Electrocardiography for the Cardiovascular Screening of High School Athletes: A Prospective Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8, e012235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarto P, Zorzi A, Merlo L; et al. Value of screening for the risk of sudden cardiac death in young competitive athletes. European Heart Journal 2023, 44, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano F, Schiavon M, Cipriani A; et al. Causes of sudden cardiac arrest and death and the diagnostic yield of sport preparticipation screening in children. Br J Sports Med, 2024; 58, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sumitomo N, Baba R, Doi S; et al. on behalf of the Japanese Circulation Society and the Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery of Joint Working Group. Guidelines for Heart Disease Screening in Schools (JCS 2016/JSPCCS 2016). Circ J, 2018; 82, 2385–2444. [Google Scholar]

- Dinarti LK, Murni IK, Anggrahini DW; et al. The screening of congenital heart disease by cardiac auscultation and 12-lead electrocardiogram among Indonesian elementary school students. Cardiology in the Young 2020, 31, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagkaki A, Parthenakis F, Chlouverakis G. Epidemiology of Pediatric Cardiomyopathy in a Mediterranean Population. Children (Basel). 2024, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germanakis I, Petridou ET, Varlamis G. Skills of primary healthcare physicians in paediatric cardiac auscultation. Acta Paediatr. 2013, 102, e74–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, VL. Best practices for ECG screening in children. Journal of Electrocardiology 2015, 48, 316–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado D, Pelliccia A, Bjørnstad HH; et al. Cardiovascular pre-participation screening of young competitive athletes for prevention of sudden death: proposal for a common European protocol: Consensus Statement of the Study Group of Sport Cardiology of the Working Group of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology and the Working Group of Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. European Heart Journal 2005, 2, 516–524. [Google Scholar]

- WHOReferences Growing Charts 2007 for children 5-19 years.

- Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years (Accessed 20/11/2024).

- Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germanakis I, Dittrich S, Perakaki R. Digital Phonocardiography as a screening tool for heart disease in childhood. Acta Paediatrica 2008, 51, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron BJ, Friedman RA, Klingfield P; et al. Assessment of the 12-Lead ECG as a Screening Test for Detection of Cardiovascular Disease in Healthy General Populations of Young People (12–25 Years of Age) A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation 2014, 130, 1303–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzakis I, Vassilakis K, LionisCh. Electronic health record with computerized decision support tools for the purposes of a pediatric cardiovascular heart disease screening program in Crete. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2018, 159, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germanakis I, Archontoulaki S, Giuzi J. Can Nurses master Pediatric Cardiac Auscultation following appropriate Teaching and Practice? Cardiology in Young 2018, S28, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt B, Germanakis I, Stylianou Y. A study of time-frequency features for CNN based automatic heart sound classification for pathology detection. ComputBiol Med 2018, 100, 132-143. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton LE, Lew EO, Matshes EW. “Grown-up" congenital heart disease and sudden death in a medical examiner's population. J Forensic Sci. 2011, 56, 1206-12.

- Adler A, Viskin S. Syncope in Hereditary Arrhythmogenic Syndromes. CardiolClin 2015, 33, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duksal F, Dogan MT. Investigation of the presence of atopy in children visiting the paediatric cardiology department due to chest pain. Cardiol Young 2024, 34, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan SJ, Thomson J, Parsons JM, Dickinson DF, Blackburn MEC, Gibbs JL. New outpatient referrals to a tertiary pediatric cardiac centre: evidence of increasing workload and evolving patterns of referral. Cardiol Young, 2005, 15, 43-46.

- Johnson R, Holzer R. Evaluation of asymptomatic heart murmurs. CurrPaediatr 2005, 15, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Felker R, Kelleman MS, Campbell RM ,Oster ME, Sachdeva R. Appropriate use and clinical impact of echocardiographic «evaluation of murmur» in pediatric patients. Congenit Heart Dis 2016, 11, 721-726.

- Burns J, Ganigara M, Dhar A. Application of intelligent phonocardiography in the detection of congenital heart disease in pediatricpatients: A narrative review.Progress in Pediatric Cardiology 2022, 64, 101455.

- Campbell RM, Douglas PS, Eidem BW, Lai WW, Lopez L, Sachdeva R et al. ACC/AAP/AHA/ASE/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/SOPE 2014 appropriate use criteria for initial transthoracic echocardiography in outpatient pediatric cardiology: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Pediatric Echocardiography. J Am CollCardiol 2014, 64, 2039-2060.

- Finley JP, Warren AE, Sharratt GP, Amit M. Assessing children’s heart sounds at a distance with digital recordings. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 2322–25.

- Lim HK, Wang JK, Tsai KS, Chien YH, Chang YC, Cheng CH et al. Cardiac screening in school children: Combining auscultation and electrocardiography with a crowdsourcing model. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 2023, 122, 1313e1320.

- Yu CH, Lue HC, Wu SJ. Heart Disease Screening of School children in Taiwan. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009, 163, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsopoulou A, Protonotarios I, Xylouri Z, Papagiannis I, Anastasakis A, Germanakis I et al. Cardiomyopathies in children: An overview. Hellenic J Cardiol 2023, 72, 43-56.

- Ackerman M, Atkins DL, Triedman JK: Sudden cardiac death in the young. Circulation 2016, 133, 1006–1026. [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis A, Papatheodorou E, Ritsatos K, Protonotarios N, Rentoumi V, Gatzoulis K. Sudden unexplained death in the young: epidemiology, aetiology and value of the clinically guided genetic screening. Europace 2018, 20, 472–480.

- Vilardell P, Brugada J, Aboal J; et al. Characterization of electrocardiographic findings in young students. Rev Esp Cardiol 2020, 73, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greciano Calero P, Escribá Bori S, Costa Orvay JA; et al. Can we screen for heart disease in children at public health centres? A multicentre observational study of screening for heart disease with a risk of sudden death in children. European Journal of Pediatrics 2024, 183, 2411–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurizi N, Fumagali C, Skalidis I, Muller O, Armentano N, Cecchi F et al. Layman electrocardiographic screening using smartphone-based multiple-lead ECG device in school children. Int J Cardiol 2023, 373, 142-144.

- Song P, Zhang Y, Yu J, Zha M, Zhu Y, Rahimi K et al. Global Prevalence of Hypertension in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2019, 173, 1154–1163.

- Jacobs DR Jr, Woo JG, Sinaiko AR; et al. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and adult cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 1877–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare M, Soric M, Bovet P, Miranda JJ, Bhutta Z, Steven GA et al. The epidemiological burden of obesity in childhood: a worldwide epidemic requiring urgent action. BMC Med 2019, 17, 212.

- De Ferranti SD, Steinberger J, Ameduri R, Baker A, Gooding H, Kelly AS et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in High-Risk Pediatric Patients: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e603–e634.

- Tisa IB, Achim AC, Cozma-Petrut A. The importance of Neonatal Screening for Galactosemia. Nutrients 2022, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen H, Moholdt T, Bahls M, Biffi A, Siegrist M, Lewandowski AJ et al. Lifestyle interventions to change trajectories of obesity-related cardiovascular risk from childhood onset to manifestation in adulthood: a joint scientific statement of the task force for childhood health of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) and the European Childhood Obesity Group (ECOG). Eur J PrevCardiol 2023, 30, 1462-1472.

- Myerburg, RJ. Electrocardiographic screening of children and adolescents: the search for hidden risk. European Heart Journal 2016, 37, 2498–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musen MA, Middleton B, Greenes RA. Clinical decision-support systems. In Biomedical informatics, Springer, London.2014, pp. 643-674.

- Tanaka Y, Yoshinaga M, Anan R, Tanaka Y, Nomura Y, Oku S et al. Usefulness and Cost Effectiveness of Cardiovascular Screening of Young Adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 2006, 38, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Μuta H, Akagi T, Egami K, Furui J, Sugahara Y, Ishii M et al. Incidence and clinical features of asymptomatic atrial septal defect in school children diagnosed by heart disease screening. Circ J 2003, 67, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa K, Warita N, Sunami Y, Shimura A, Tateno S, Sugita K. Prevalence of arrhythmias and conduction disturbances in large population-based samples of children. Cardiol Young 2004, 14, 68–74.

- Chiu SN, Wang JK, Wu MH, Chang CW, Chen CA, Lin MT et al. Cardiac Conduction Disturbance Detected in a Pediatric Population. The journal of pediatrics 2008, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga M,Kucho Y, Nishibatake M, Ogata H, Nomura Y. Probability of diagnosing long QT syndrome in children and adolescents according to the criteria of the HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement. European Heart Journal 2016, 37, 2490–2497.

- Liu HW, Huang LW, Chiu SN, Lue HC, Wu MH, Chen MR, Wang JK. Cardiac Screening for High Risk Sudden Cardiac Death in School-Aged Children. ActaCardiol Sin 2020, 36, 641-648.

- Mancone M, Maestrini V, Fusto A, Adamo F, Scarparo P, D’Ambrosi A et al. ECG evaluation in 11 949 Italian teenagers: results of screening in secondary school. J Cardiovasc Med 2022, 23, 98–105.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).