1. Introduction

ECG is a widely used non-invasive method to estimate cardiac electrical integrity. It not only provides useful information on or defines different cardiac diseases (e.g., long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome) but is also helpful in the management of systemic disturbances.

Values measured with a resting ECG are influenced by several factors. First, metabolic syndrome (MS) or its components alone have branching effect on the ECG's parameters as early as childhood [

1,

2]. Second, physical activity (PA) has beneficial effects on cardiovascular system in children, which are also reflected in some resting ECG parameters. [

3,

4,

5]. Third, those who experienced worse socioeconomic status (SES) in their childhood, independently of their circumstances during adult life, generally were at greater risk for developing of cardiovascular diseases [

6], although its direct relation to childhood ECG is not clear. It should also be considered that age alone influences several ECG parameters in children, as in adults [

7].

These data emphasize the importance of investigating the different effects of diverse factors (including MS, PA, and SES) on resting ECG. Although the individual impact of these factors has already been investigated by numerous studies, the measurement of these factors and their possible interactions together on the resting ECG has not yet been investigated. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the sum impact of MS, PA, and SES on different resting ECG parameters in children, considering age as a physiological variable influencing ECG parameters.

2. Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted on children at Heim Pál Hospital, Budapest, Hungary, between January 2023 - January 2025. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics Research Council of Hungary with the number of OGYÉI/56533-3/2023. All patients’ legal representatives (in all cases, one of the parents) signed an informed consent form and agreed to the scientific usage of the collected data.

2.1. Study Participants

The present study includes randomly selected paediatric patients from the HOGYI questionnaire (Protocol number: HOGYI/TKP 2023; Project No. at AdWare Research: 1095CCL/2022.). The HOGYI questionnaire is part of a nationwide survey aimed to assess children’s mental and physical health. From the questionnaire, only those questions were used which are referred to in section 3.3 of the public education questionnaire taken during the survey.

The records of 22,808 children were available in the questionnaire. A random number generator selected 1,000 patients, who were invited to participate. Out of these 1,000 patients, 177 responded and agreed to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were the following: if the patient was deemed unfit to cooperate by the examining physician (e.g. due to mental condition); fever in the 10 days prior to the examination; any surgical intervention in the 3 months prior to the examination; body weight of the patient changing by more than 15% in any direction in the 1 month prior to the examination; known cardiac malformation (except for persistent patent foramen ovale deemed hemodynamically insignificant during previous cardiological examination, surgically resolved persistent ductus arteriosus Botalli or coartation of the aorta); or hemodynamically significant acquired heart disease or structural heart disease, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia or atrial fibrillation/flutter in the medical history. Uncontrolled thyroid disease, known malnutrition and anaemia (haemoglobin: 110 g/L for girls; 120 g/L for boys) or unconsciousness with unknown origin in the medical history also served as exclusion criteria. None of the study participants used concomitant cardiovascular medication. During a personal meeting with the included patient and their parents, informed consent was obtained and signed by a representative. Demographic data (age and sex), physical activity level, socioeconomic status, and current and previous chronic illness data were collected from the questionnaire to a standardized data entry form.

2.2. Baseline Assessment

A detailed physical examination and a laboratory test were completed by accredited laboratory and a medical professional after a minimum 12 hours fasting. The following parameters were measured: fasting blood glucose (mmol/l), HbA1c (% and mmol/mol), total cholesterol (mmol/l), HDL cholesterol (mmol/l), triglyceride (mmol/l). LDL cholesterol was calculated by Friedewald formula (LDL Cholesterol = Total Cholesterol - HDL Cholesterol - (Triglycerides / 5)). Height (cm to the nearest 0.1 cm) and weight (kg to the nearest 0.1 kg) were measured by standard methods but were not used (available upon request). Based on the recommendation of the World Health Organization [

8], waist circumference (WC) was measured midway between the lowest rib and the superior border of the iliac crest at the end of a normal expiration with a flexible nonelastic anthropometric tape, to the nearest 0.1 cm. Blood pressure was measured with Omron M2 blood pressure monitor in sitting position after at least 5 minutes resting, on the right and left arms, than the measurement was repeated on the arm where the higher value was measured; the published numbers are the average of these two measurements. If this value was higher than blood pressure above the 95th percentile according to age and gender, the patient was excluded from the study and referred to a specialist.

Parameters related to metabolic syndrome (MS) were compounded to form a variable which was used for grouping participants. Although the diagnosis of MS in children is not recommended until the age of 10, risk factors are present in many children and should be addressed prior to a formal diagnosis [

9]. In contrast to the definition used in adulthood, just 2 of the following parameters are enough to give the diagnosis of MS in children [

9]: WC ≥ 90th percentile for age and gender, Triglycerides ≥ 1.69 mmol/l (150 mg/dL), HDL: < 1.03 mmol/l (40 mg/dL), fasting blood glucose >5.6 mmol/l (100 mg/dL) or known type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Physical activity level (PA) was estimated using the following question: “Apart from school physical education, how much does your child exercise every day”. If the answer is “not at all” or “less than 30 minutes” the score is 0 points (does not exercise); in case of “30-60 minutes” or “60-90 minutes,” 1 point (does exercise occasionally), “more than 90 minutes,” 2 points (does exercise regularly).

Socioeconomic status (SES) was evaluated by weighted questions. The following questions and scores were used. Question 1: “What is the highest education of the parents”; if both parents have primary education, or one parent has primary education and the other has secondary education: 0 points; if both parents have higher education (BSc, MSc, PhD or other academic rank): 2 points, in all other cases: 1 point. Question 2: “How many cars does the family have”; in case of 0 cars 0 points, 1 point in 1 car, 2 points above 1. Question 3: “How many times can the family go on vacation per year”; 0 points in 0 cases, 1 point in 1 case, 2 points above 1. Question 4: “What is the parents’ impression about the family’s social situation”; if the answer is “below average” 0 points, “average” 1 point, “above average” 2 points.

2.3. ECG Measurements

ECGs were performed by trained technicians following a standard ECG acquisition protocol for 12-lead ECGs. Study subjects were resting in a supine position at least for 5 minutes before the 1 minute recording has started. ECGs were obtained using CPNSS/DB Integrated cardiovascular cardiac and sensory nerve neuropathy measurement system (MSB-MET Ltd, Balatonfüred, Hungary) at 500 Hz sampling frequency. The ECG variable values were exported electronically, unfiltered, at 500 Hz. ECGs were obtained with usual standardization for voltage (10 mm=1 mV) and speed (25 mm/s). All ECGs were evaluated based on electronic data acquisition by medical professional. The following parameters were checked: RR, PR, QRS, QTc (Bazett), Tpeak-to-Tend (TTe) and Tend-to-P (TP) intervals (all in msec). If values of a single ECG cycle were significantly different from the average (>2SD + average), the cardiac cycle was checked manually on the original recording. ECGs with technical problems such as poor baseline, or missing lead information were excluded from the analysis. If a patient’s resting ECG shown abnormality (>150/min tachycardia, <40/min bradycardia, any extrasystole during the ECG recording or conduction abnormality), the patient was excluded from the further investigation and was sent to a cardiologist to perform further investigations.

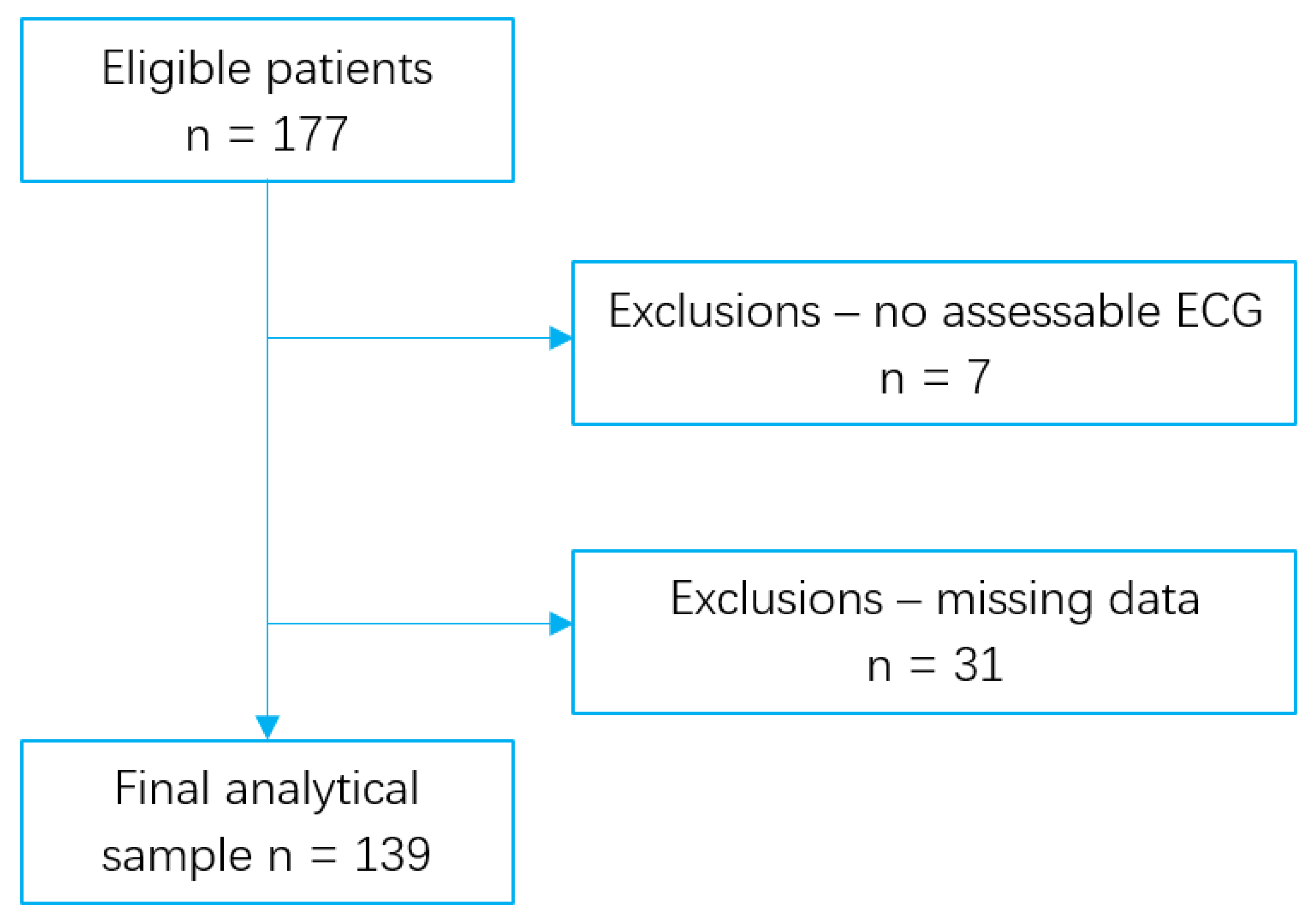

Figure 1 shows that a total of 177 patients were eligible for inclusion in the study. Out of them, 7 have no assessable ECG because of technical problems. An additional 31 individuals were excluded from the study due to missing data. Data of the remaining 139 patients were included in the final analysis.

2.4. Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 29.0 (IBM Corp., NY, USA). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was calculated with RR interval, PR interval, QRS duration, QTc interval, total TTe, and TP as outcomes. Sex, MS, and SES were used as fixed factors, while age was included as a covariate. The model was used to assess the main effects of each factor and their interactions in pairs. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

Out of the 139 investigated patients, 60 were male. Participants’ age, diastolic blood pressure, serum triglyceride, HDL cholesterol and fasting glucose levels did not differ significantly between the two genders. However, male patients had higher waist circumference and somewhat higher systolic blood pressure although both values remained in normal range and their clinical significance is limited. On the other hand, there was no differences among male and female patients in their measured PA and SES. Results are listed in

Table 1.

ANCOVA statistical approach was used to evaluate the effect of different parameters on resting ECG. This showed that heart rate-associated parameters – RR and TP intervals – are strongly influenced by all examined factors except SES (

Table 2). The strongest link was found between RR or TP interval and age. Patient’s sex and MS alone had similar effects on RR and TP intervals. Estimated PA had the weakest but still significant effect on these heart rate-related markers ANCOVA was also calculated for conduction, depolarisation, and repolarisation-related ECG parameters (PR, QRS, QTc, and TTe). These were associated only with age, except for QTc, where patient sex had a weak but significant effect. However, neither MS nor PA showed any association with these parameters of resting ECG. Like the heart rate associated parameters, SES was also not a significant explanatory factor here. Also, no two-way interactions between the factors were statistically significant. Data are presented in

Table 2.

Next, the weighted impact of the variance of the investigated effects was calculated, which gives an estimation of what percentages of the variance can be explained by a certain parameter. By applying this approach to RR interval, it was determined that age, gender, MS, PA, and SES altogether explain about R2=0.337 (34%) of the experienced variance. The same analysis for TP value is R2=0.307 (31%). However, for the conduction, depolarisation and repolarisation parameters, the weight of the investigated factors in the experienced variance are low or negligible (R2 values: PR: 0.091 (9%), QRS: 0.042 (4%), QTc: 0.114 (11%), TTe: 0.090 (9%)).

After the main effects of the different conditions on resting ECG parameters were evaluated, we wanted to determine the numeric impact of these significant factors on the investigated parameters. Since age was a used as covariant, we filtered out its effect on ECG parameters by fixing it at its mean value (mean age: 12.98 years). After this, the average RR interval was 853 msec in male and 788 msec in female participants. This shows that an average of 65 msec difference can be explained by the gender itself and female patients have somewhat higher resting heart rate. The presence of MS explains a similar effect with 74 msec difference (average RR 858 msec in healthy participants, 784 msec in patients with MS). It is important to emphasize that independently of the duration of regular PA, its effect on heart rate associated parameters are significant, although the duration of PA performed clearly affect the values. Numerically, in case of a regular 30-90 minutes’ daily PA, the difference compared to those who do not make regular PA was 49 msec (<30 min PA 770 msec vs. 30-90 min/day physical activity 819 msec average RR intervals); comparing those with physical activity >90 min/day to those without regular PA, the difference is 104 msec (average RR 770 msec vs. 874 msec). Data are summarised in

Table 3.

TP values were significantly affected by these same parameters. The numerical values are as follows: average TP in male: 336 msec vs. female: 272 msec (diff.: 64 msec); presence of MS 275 msec vs. lack of MS: 333 msec (diff.: 58 msec); and with PA level less than 30 min/day 267 msec, 30-90 min /day: 306 msec, >90 min/day 340 msec (diff.: 39 msec and 73 msec). These data are also summarised in

Table 3.

Among the other parameters, PR, QRS, QTc and TTe values were all affected significantly by age. QTc was also affected by sex. After fixing the age on its mean value, sex itself explained a clinically non-relevant, approximately 10 msec difference in females with a higher value (average QTc in male 413 msec vs. in female 423 msec). Data is summarised in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

Resting ECG is a widely used non-invasive method to evaluate basic cardiac electric function in both adults and children. The impact of different, clinically important parameters like PA, parameters related to MS, and an evaluation of SES taken together on resting ECG values has not yet been evaluated on children. Modern medicine has undergone a major shift in focus from identification and treatment of clinically apparent illnesses to a preventive method which makes it crucial to know which long-term conditions have any effect on markers that can be easily followed. Based on our results, RR, PR, QRS, QTc (Bazett), TTe and TP period are strongly influenced by age. Sex has significant, but different effect on RR, QTc and TP intervals. MS associated factors and sport activity have pronounced impact only on resting heart rate related markers (RR and TP). SES has no significant impact on resting ECG parameters. Our data indicates that QTc and TTe intervals, which are widely considered to be a predictors or risk factors of sudden cardiac death [

10,

11] or even atrial fibrillation in adults [

12], are relatively protected from these different conditions in childhood. Also, no interaction was found among the effect of these conditions in the different ECG markers.

Resting ECG has been proposed for screening purposes in asymptomatic populations as it is a reproducible, accessible, and non-invasive cardiovascular examination. However, ECG may not be cost-effective and may potentially increase unnecessary testing and care cascade [

13]. Because of insufficient evidence on whether screening ECG can improve health outcomes, the US Preventive Services Task Force [

14] and the European Society of Cardiology [

15] do not recommend performing screening ECG for adult individuals at low risk of CVD.

It is known that childhood chronic diseases, like obesity, adversely affect the structure and function of the cardiovascular system. Furthermore, paediatric obesity is linked to long term consequences and an increased risk of developing major cardiovascular risk factors later in life [

16]. According to the literature, MS has a wide range of effects on ECG parameters, including PR interval prolongation [

1], QT/QTc alteration [

17,

18,

19], TTe prolongation [

20] in adults, and has a known effect on heart rate [

2] in children

. Also, exercise induces typical alterations in children’s ECG [

21]

and there is a difference in ECG parameters even in cases when athletes in different childhood ages are compared [

22]

. Therefore, performing resting ECG for screening purposes and for further follow up seems to be reasonable.

One of the most investigated parameters that potentially alters ECG and strongly determines metabolic status is obesity [

2,

4]. It is easy to investigate in the clinical practice and has a clear effect on ECG, especially in adults. The slight ECG changes reported in childhood obesity may manifest later and develop into pathological phenomena in obese adults [

3]. Two meta-analyses both demonstrated an association of higher BMI in childhood with an increased risks of coronary heart disease (CHD), including stable angina and myocardial infarction, in adults [

23,

24]. Prolonged QT intervals, increased QT dispersion, and longer JT intervals have been observed in children with metabolic syndrome, particularly those who are obese [

25]. Another systemic review concluded that in obese children, only a marginal QTc prolongation is present compared to non-obese ones, and even this prolongation falls within the normal range [

26]. Reviewing the literature demonstrates that the effects of paediatric obesity on ECG parameters are manifold.

It is important to note that the definition of obesity in childhood is varied. It is very difficult to isolate a single element of the metabolic syndrome and analyse its impact on ECG, especially among children. These facts emphasize the importance of evaluating the effect of main metabolic parameters on heart at a young age, as it seems reasonable that ECG alterations observed in childhood could be early markers of future cardiovascular disease in adulthood [

16,

23,

24,

27]. Although this question is beyond the scope of the present cross-sectional study, it has a rationale that if related conditions - like regular PA, MS and sedentary lifestyle - have typical clues on childhood ECG and probably predict the risk of future cardiovascular events. Continuing this line of thought, evaluating the effect of physical activity on ECG parameters could also have importance, as regular or sustained physical activity is clearly associated with several beneficial electrophysiological, structural, and functional cardiac adaptations in children [

28]. Studies have yet to be published explaining which specific factors (e.g.: physical growth, race, and sex) have the potential to generate ECG changes in athletes and to which degree. However, it has been demonstrated that paediatric athletes have a significantly longer PR interval and a significantly greater frequency of sinus bradycardia, first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, and incomplete right bundle branch block (IRBBB); furthermore, the voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy and T-wave inversion – especially in inferolateral region – was more common when compared with paediatric non-athletes [

29]. These effects are also influenced by age, race, and sex-mediating factors. However, our results cannot be directly compared with these conclusions as the definition of physical activity we used is different to the one used by others. The biggest advantage of our own method is that it classifies our patients’ physical activity in a simple, easy-to-understand and answerable way, making it easily reproducible in clinical practice.

Another frequently investigated topic is the association between cardiometabolic risk, physical activity, and heart rate variability (HRV) [

30,

31]. A variety of different methods have been used in these studies, but a review focusing on paediatric populations affirms the connection between decreased HRV and a dysregulated autonomic response that leads to increased cardiometabolic risk and mortality [

31]. Another meta-analysis showed that increased PA in children and adolescents also increased HRV [

32]. At this point, direct comparison of these HRV results with ours is not possible, as the 1-minute resting ECG used in our study is not long enough for approximating heart rate variability and only a standard deviation of heart rate could be calculated. As our results highlight, even a shorter duration of PA had significant effect on heart rate, and this can be assessed with simple questions. This finding corroborates the importance of even a short duration of regular PA in children.

Turning to the final factor, our results indicated no association between SES and resting ECG parameters. Recently, the importance of early-life developmental factors and their impact on cardiovascular diseases in adulthood is being increasingly recognised, especially in ethnic minorities [

33,

34,

35]. The key biological factor behind low childhood SES and adverse adult health is the continuous stress-related activation of the autonomic nervous system [

36]. Accordingly, higher resting heart rate would be a clue of lower SES, but we did not find any difference in heart rate among different SES groups. SES were defined with simple questions which might not be sensitive enough to differentiate among children’s subgroups. More specific questions, such as ones related to optimism, purpose in life or self-esteem, are associated with lower rates of disease and increased longevity [

36]. However, in the routine clinical practice, there is simply not enough time, and we did not ask such detailed questions. Nevertheless, low SES may have an indirect effect on ECG (due to worsening physical activity, increasing weight, and eating non-healthy food) and therefore the duration or severity of the patients’ socio-economic condition is not enough to induce any detectable changes in ECG in early childhood.

Our study has certain limitations which should be addressed. It must be emphasized that although the principle of correction of QT value for heart rate is recommended, there is debate about how this should be achieved [

37]. Our study, like much of the previously cited literature, did not focus on this question; instead, the most widely used Bazett form for QT correction was applied. As a cross-sectional study, the predictive value of these parameters cannot be estimated, making the real value of these data is not known yet. Since the taken resting ECG is relatively short (only 1 minute), heart rate variability cannot be calculated. Also, the potential effect of the age periods on the ECG parameters cannot be excluded. Finally, it is unlikely, but a selection bias is possible in the sense that patients who choose to participate in the study generally have a better physical or mental condition and therefore willingly participated.

However, our study has certain strengths. The 1-minute resting ECG investigation is clinically useful, and easy to implement and reproduce in the everyday practice, giving us abundant data to work with. The ECG machine is user friendly and allows exact measurements, since it saves all ECG beats separately and, if necessary, the beats can be adjusted manually. During the ECG examinations, no extrasystole, obvious conduction or repolarisation abnormalities were diagnosed, which makes the studied patient population relatively homogeneous. Finally, since detailed anamnesis and complete parameters are available for most participants, few had to be excluded, thereby decreasing the chance of a possible selection bias, and making our results more robust.

In summary, our results provide additional information about the value of resting ECG parameters in children of different ages and highlights that QTc and PR intervals are relatively stable independently of the presence of MS. SES, as approximated approached by our question, has no effect on resting ECG parameters in children. Further studies required to define whether heart rate variability is more sensitive for validating manifest complications on cardiovascular system in these groups and to decide whether different QT correction approaches lead to the same results. Also, by continuing to follow this cohort we can determine whether repolarisation parameters alter with time, or they can be considered stable throughout childhood.