Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

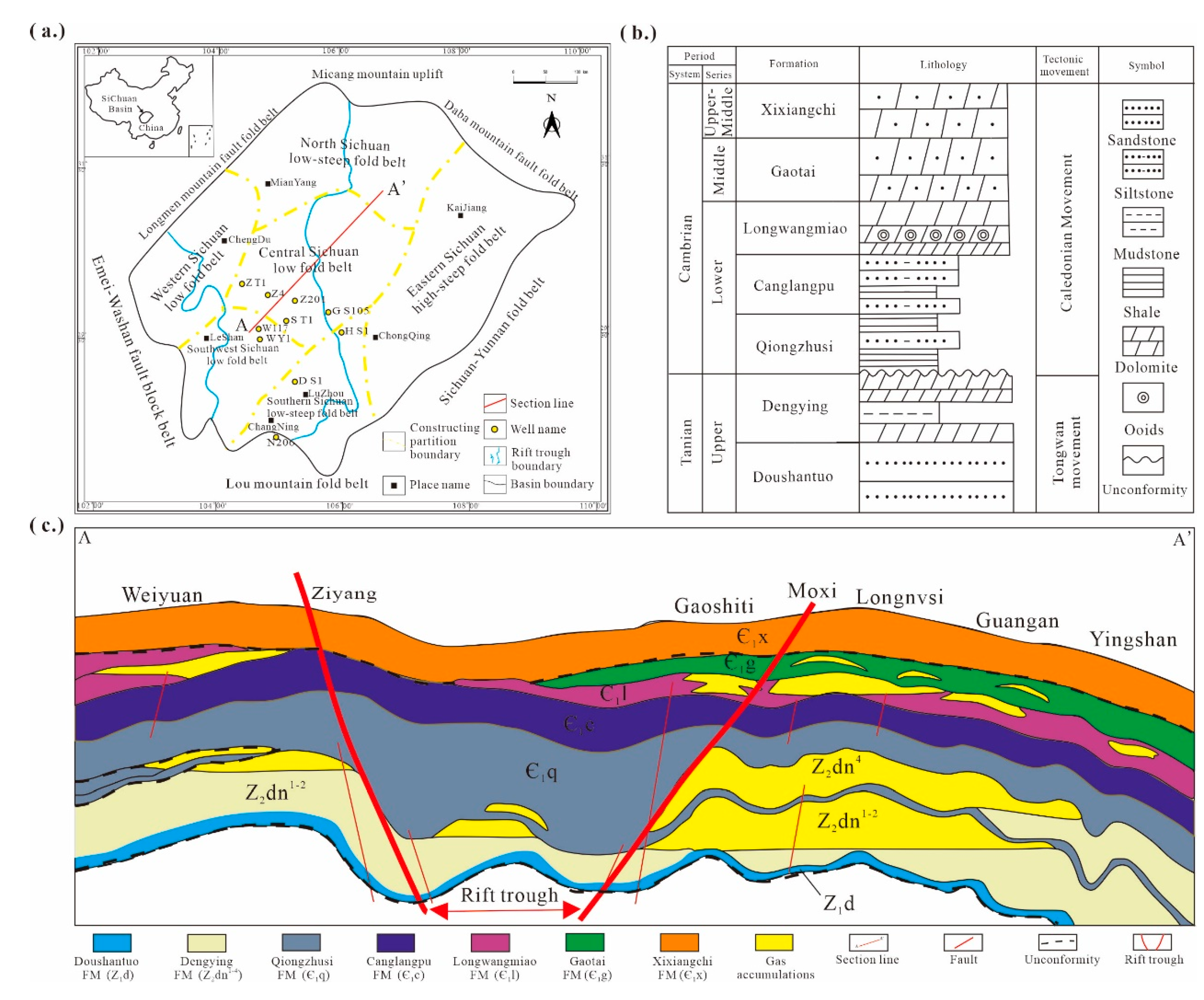

2. Geological Setting

3. Samples and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

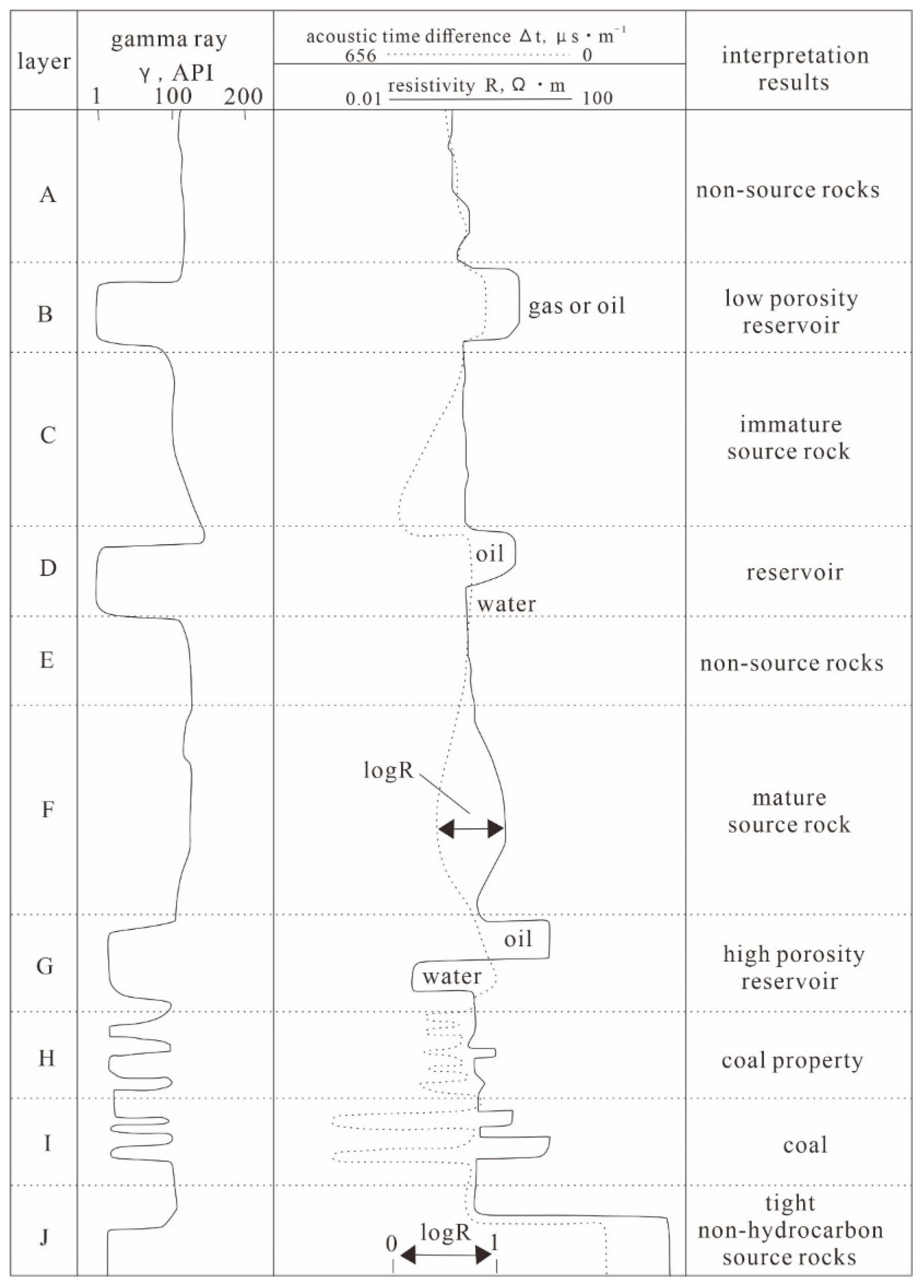

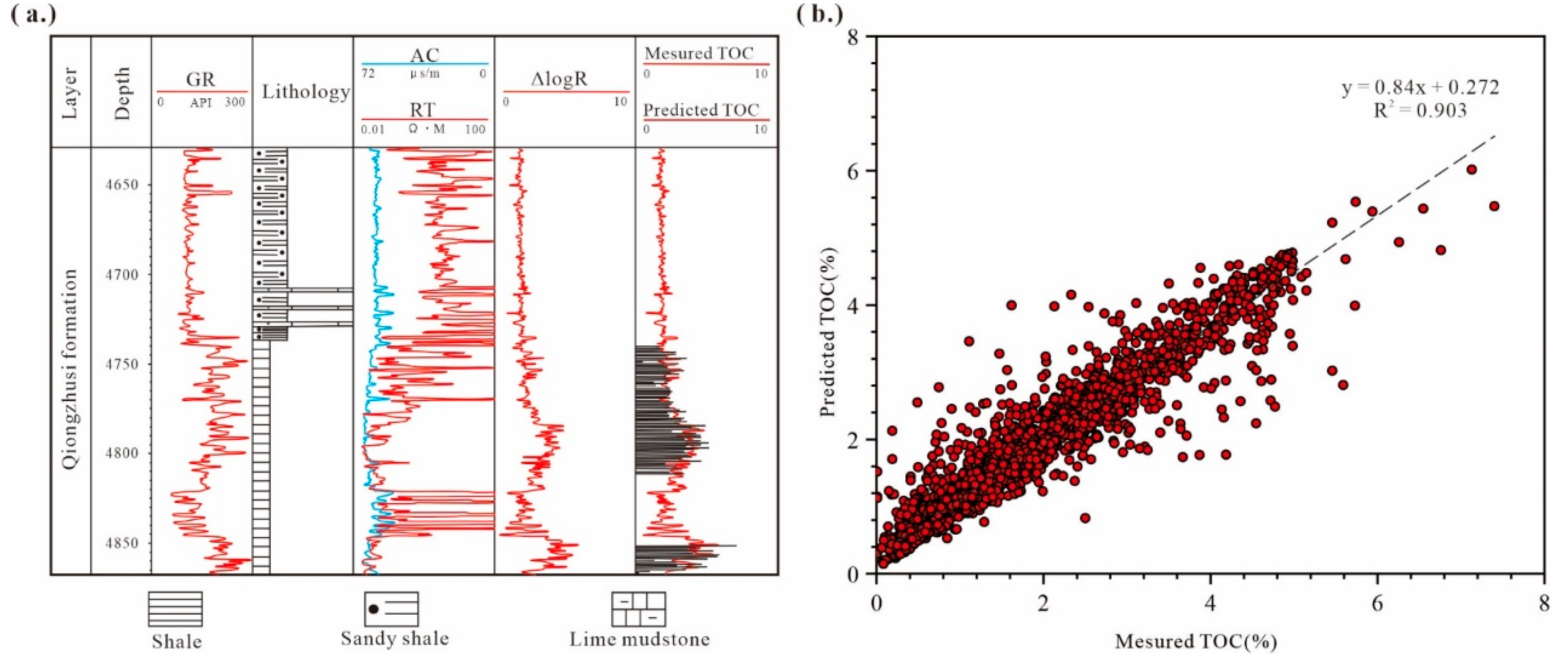

3.2. TOC Prediction and Effective Thickness Calculation Method

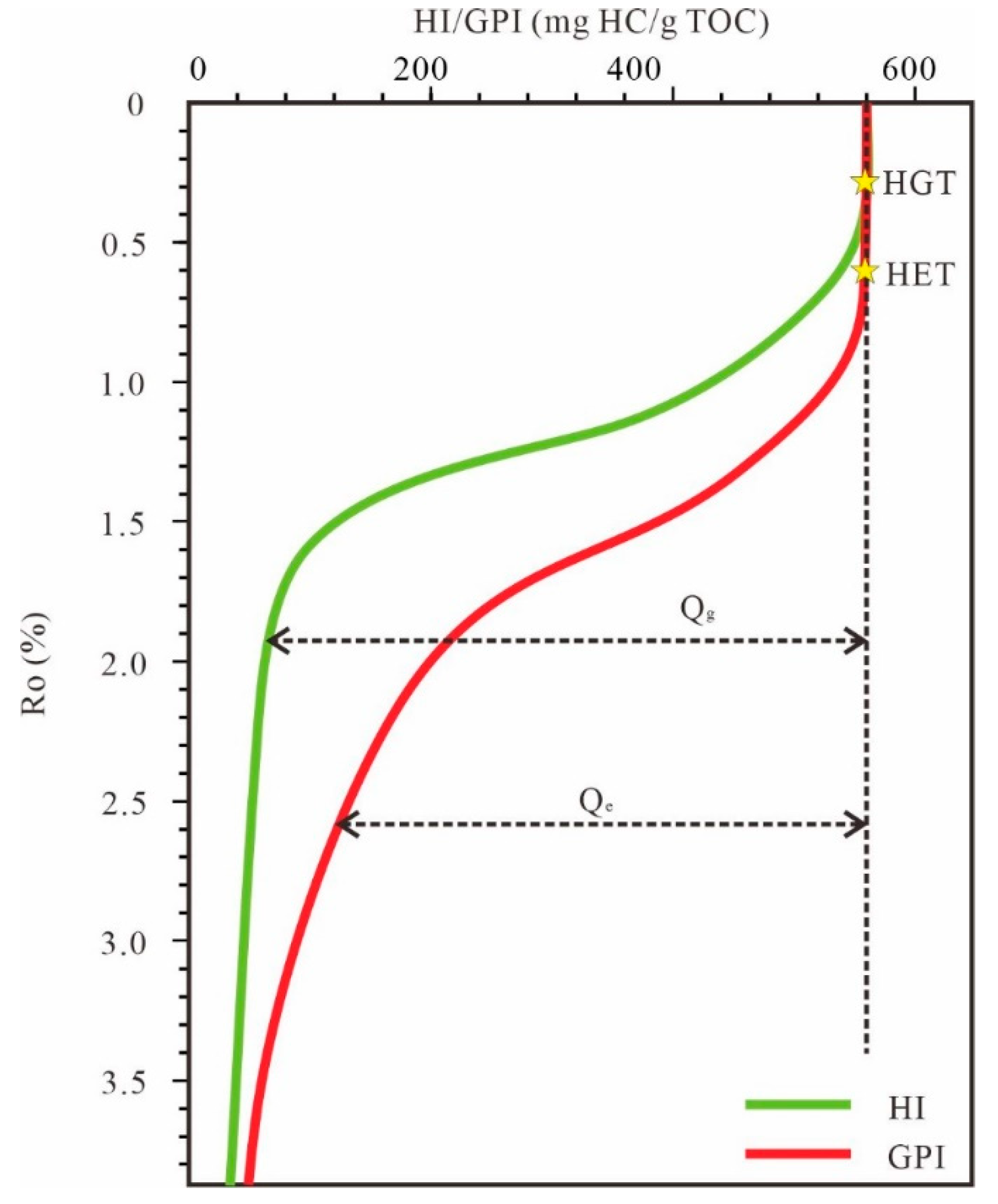

3.3. Resource Potential Assessment Method

4. Results

4.1. Single-Well Effective Thickness and TOC Prediction Results

4.2. Recovery Results of Hydrocarbon Generation and Expulsion History and Maturity Evolution Characteristics of Source Rocks

4.3. Results of Resource Potential Evaluation

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of International Resource Evaluation Methods

5.2. Beneficial Exploration Areas for the Є1q

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Jin, Q.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, F. Evaluation method of effective source rock in mature exploration area: a case study of Liaodong Bay. Acta Petrolei Sinica 2019, 40, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.; Rojas, K.; Niemann, M.; Palmowski, D.; Peters, K.; Stankiewicz, A. Basic petroleum geochemistry for source rock evaluation. Oilfield Review 2011, 23, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, L.G. Highlights on 1948 developments in foreign petroleum fields. AAPG Bulletin 1949, 33, 1029–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Pang, X.; Huo, Z.; Wang, E.; Xue, N. A revised method for reconstructing the hydrocarbon generation and expulsion history and evaluating the hydrocarbon resource potential: Example from the first member of the Qingshankou Formation in the Northern Songliao Basin, Northeast China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2020, 121, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, A.S. Estimating the petroleum expulsion behaviour of source rocks: a novel quantitative approach. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 1991, 59, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvie, D.M. Shale resource systems for oil and gas: Part 2—Shale-oil resource systems. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Egbobawaye, E.I. Petroleum source-rock evaluation and hydrocarbon potential in Montney Formation unconventional reservoir, northeastern British Columbia, Canada. Natural Resources 2017, 8, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Sarmiento, M.-F.; Ramiro-Ramirez, S.; Berthe, G.; Fleury, M.; Littke, R. Geochemical and petrophysical source rock characterization of the Vaca Muerta Formation, Argentina: Implications for unconventional petroleum resource estimations. International Journal of Coal Geology 2017, 184, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Pan, Y. Quantitative evaluation of oil and gas resources: a geological analogy model based on Delphi method. In Proceedings of the 2009 Sixth International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery; 2009; pp. 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissot, B.P.; Welte, D.H. Petroleum formation and occurrence; Springer Science & Business Media: 2013.

- Wang, E.; Feng, Y.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, C. Hydrocarbon source potential evaluation insight into source rocks—A case study of the first member of the Paleogene Shahejie Formation, Nanpu Sag, NE China. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triche, N.E.; Bahar, M. Shale gas volumetrics of unconventional resource plays in the Canning Basin, Western Australia. In Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Unconventional Resources Conference and Exhibition, 2013; pp. SPE–167078-MS. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Pang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Jiang, F.; Guo, J.; Guo, F.; Peng, W.; Xu, J. Gas generation and expulsion characteristics of Middle–Upper Triassic source rocks, eastern Kuqa Depression, Tarim Basin, China: Implications for shale gas resource potential. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 2014, 61, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Yang, W.; Xie, Z. Characteristics of source rocks, resource potential and exploration direction of Sinian-Cambrian in Sichuan Basin, China. Journal of Natural Gas Geoscience 2017, 2, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiming, A.; Ding, X.; Qian, L.; Liu, H.; Hou, M.; Jiang, Z. Gas Generation Potential of Permian Oil-Prone Source Rocks and Natural Gas Exploration Potential in the Junggar Basin, NW China. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 11327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Caineng, Z.; Jianzhong, L.; Dazhong, D.; Sheiiao, W.; Shiqian, W.; Cheng, K. Shale gas generation and potential of the lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi formation in the southern Sichuan Basin, China. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2012, 39, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Guo, T. Enrichment of shale gas in different strata in Sichuan Basin and its periphery—The examples of the Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation and the Silurian Longmaxi Formation. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 2015, 33, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Du, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wei, G.; Wang, T.; Yao, G.; Deng, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Formation, distribution, resource potential, and discovery of Sinian–Cambrian giant gas field, Sichuan Basin, SW China. Petroleum exploration and development 2014, 41, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pang, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, E.; Hu, T.; Wu, Z. Hydrocarbon generation and expulsion characteristics of the Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi shale in the Sichuan Basin, Central China: Implications for conventional and unconventional natural gas resource potential. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2021, 204, 108610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Chen, G.; Du, S.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W. Petroleum systems of the oldest gas field in China: Neoproterozoic gas pools in the Weiyuan gas field, Sichuan Basin. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2008, 25, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xie, X. The progress and prospects of shale gas exploration and development in southern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2018, 45, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Chang, J.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, H. Thermal evolution and maturation of lower Paleozoic source rocks in the Tarim Basin, northwest China. AAPG bulletin 2012, 96, 789–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Jia, C.; Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; Li, B.; Chen, J. The dead line for oil and gas and implication for fossil resource prediction. Earth System Science Data 2020, 12, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, C.; Wu, W.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Deng, B. Cenozoic exhumation and shale-gas enrichment of the Wufeng-Longmaxi formation in the southern Sichuan basin, western China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2021, 125, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Mao, W.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, S. Research on the differential tectonic-thermal evolution of Longmaxi shale in the southern Sichuan Basin. Advances in Geo-Energy Research 2023, 7, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Nie, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, T. Source and seal coupling mechanism for shale gas enrichment in upper Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation in Sichuan Basin and its periphery. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2018, 97, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Wen, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhong, J.; Wang, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, X.; Yan, W.; Ding, Y.; et al. Segmented evolution of Deyang–Anyue erosion rift trough in Sichuan Basin and its significance for oil and gas exploration, SW China. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2022, 49, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, S.; Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Xu, J. Sedimentary Environment and Enrichment of Organic Matter During the Deposition of Qiongzhusi Formation in the Upslope Areas—A Case Study of W207 Well in the Weiyuan Area, Sichuan Basin, China. Frontiers in Earth Science 2022, 10, 867616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Liang, H.; Wu, G.; Tang, Q.; Tian, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Formation and evolution of the strike-slip faults in the central Sichuan Basin, SW China. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2023, 50, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xie, W.; Li, W.; Gu, M.; Liang, Z. Geological characteristics of the southern segment of the Late Sinian—Early Cambrian Deyang—Anyue rift trough in Sichuan Basin, SW China. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2023, 50, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, Q.; Creaney, S.; Kulla, J.; Moretti, F.; Stroud, J. A practical model for organic richness from porosity and resistivity logs. AAPG bulletin 1990, 74, 1777–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, L.; Liu, G.; Sun, M.; Yang, D.; Wan, W.; Zhang, C. Improved ΔlogR technique and its application to predicting total organic carbon of source rocks with middle and deep burial depth. Petroleum Geology and Recovery Efficiency 2018, 25, 40–45, (in Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Lerche, I.; Fajin, C.; Zhangming, C. Hydrocarbon expulsion threshold: Significance and applications to oil and gas exploration. Energy exploration & exploitation 1998, 16, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Pang, X.; Meng, Q.; Zhou, X. A method of identifying effective source rocks and its application in the Bozhong Depression, Bohai Sea, China. Petroleum Science 2010, 7, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Liu, G.; Fu, J.; Yao, J. A new method for determining the lower limit of organic matter abundance in effective source rocks - taking the lacustrine mudstone source rocks of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Longdong area of the Ordos Basin as an example. Journal of Xi'an Shiyou University (Natural Science Edition) 2012, 27, 22-26+118, (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Huang, X.; Qi, Y.; Mao, Z.; Li, Y. Hydrocarbon generation and expulsion quantification and contribution of multiple source rocks to hydrocarbon accumulation in Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, China. Journal of Natural Gas Geoscience 2021, 6, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, T.; Wang, E.; Zhang, H.; Liang, Y. Hydrocarbon generation and expulsion of Middle Jurassic lacustrine source rocks in the Turpan–Hami Basin, NW China: Implications for tight oil accumulation. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 2021, 39, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Pang, X.; Shi, H.; Yu, Q.; Cao, Z.; Yu, R.; Chen, D.; Long, Z.; Jiang, F. Source rock characteristics and hydrocarbon expulsion potential of the Middle Eocene Wenchang formation in the Huizhou depression, Pearl River Mouth basin, south China sea. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2015, 67, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Fang, J. Reservoir evaluation of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation shale gas in the southern Sichuan Basin of China. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2014, 57, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Tang, X.; Cai, D.; Xue, G.; He, Z.; Long, S.; Peng, Y.; Gao, B.; Xu, Z.; Dahdah, N. Comparison of marine, transitional, and lacustrine shales: A case study from the Sichuan Basin in China. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2017, 150, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, H. Classification, structure, genesis and practical importance of natural solid oil bitumen (“migrabitumen”). International Journal of coal geology 1989, 11, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, N.; Huang, Z.; Deng, C.; Xie, L.; Han, H. Efficiency and model of hydrocarbon generation and expulsion in lacustrine source rocks under geological conditions. Acta Geologica Sinica88, 2014, 2005-2032. (Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Mi, J.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Y.Z. An improved hydrocarbon generation model of source rocks and key parameter templates. China Petroleum Exploration 2019, 24, 661.

- Hu, G.; Pang, Q.; Jiao, K.; Hu, C.; Liao, Z. Development of organic pores in the Longmaxi Formation overmature shales: Combined effects of thermal maturity and organic matter composition. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2020, 116, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Xie, Z.; Li, Z.; Ma, C. Modeling of the whole hydrocarbon-generating process of sapropelic source rock. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2018, 45, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIA, (2021). Energy Outlook 2020. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Estrada, J.M.; Bhamidimarri, R. A review of the issues and treatment options for wastewater from shale gas extraction by hydraulic fracturing. Fuel 2016, 182, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauter, M.S.; Alvarez, P.J.; Burton, A.; Cafaro, D.C.; Chen, W.; Gregory, K.B.; Jiang, G.; Li, Q.; Pittock, J.; Reible, D. Regional variation in water-related impacts of shale gas development and implications for emerging international plays. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Magoon, L.B.; Dow, W.G. The petroleum system-from source to trap. AAPG Bulletin (American Association of Petroleum Geologists);(United States) 1991, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C. Breakthrough and significance of unconventional oil and gas to classical petroleum geology theory. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2017, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Pang, X.; Song, Y. Basic principles of the whole petroleum system. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2024, 51, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, T.; Baihly, J.; Boyer, C.; Clark, B.; Waters, G.; Jochen, V.; Le Calvez, J.; Lewis, R.; Miller, C.K.; Thaeler, J. Shale gas revolution. Oilfield review 2011, 23, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, A.M.; Medlock III, K.B.; Soligo, R. The status of world oil reserves: conventional and unconventional resources in the future supply mix. Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice Univ., Houston, TX 2011.

- Meakin, P.; Huang, H.; Malthe-Sørenssen, A.; Thøgersen, K. Shale gas: Opportunities and challenges. Environmental Geosciences 2013, 20, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Li, M.; Li, S.; Jin, Z. Geochemistry of petroleum systems in the Niuzhuang South Slope of Bohai Bay Basin: Part 3. Estimating hydrocarbon expulsion from the Shahejie formation. Organic Geochemistry 2005, 36, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, L. , Luo, W., Yin, Y., Jin, X. Formation conditions of shale oil and favorable targets in the second member of Paleogene Funing Formation in Qintong Sag, Subei Basin. Petroleum Geology & Experiment. 2021, 43, 233–241, (in Chinese with English abstract. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Well | Depth | Lithology | TOC | Well | Depth | Lithology | TOC, % |

| DB1 | 5979.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.62 | GS17 | 5176.5 | Silty mudstone | 0.88 |

| DB1 | 5979.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.62 | ZS101 | 5549.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.70 |

| DB1 | 5973.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.95 | ZS101 | 5564.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.75 |

| DB1 | 5979.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.62 | ZS101 | 5579.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.60 |

| GS17 | 4604.9 | Silty mudstone | 0.60 | ZS101 | 5609.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.60 |

| GS17 | 4645.9 | Silty mudstone | 0.61 | ZS101 | 5624.0 | Silty mudstone | 0.53 |

| GS17 | 5125.3 | Silty mudstone | 1.22 | Z201 | 4621.3 | Silty mudstone | 0.78 |

| GS17 | 5138.6 | Silty mudstone | 0.76 | Z201 | 4624.2 | Silty mudstone | 0.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).