1. Introduction

Lyme disease (LD), also known as Lyme borreliosis, is a zoonotic disease caused by the

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species complex, which includes at least 20 genospecies. The bacteria are transmitted to humans through the bite of infected

Ixodes ticks. Four

Borrelia genospecies are responsible for most infections globally. In the U.S.,

Borrelia burgdorferi is the primary causative agent, while

Borrelia afzelii,

Borrelia garinii, and

Borrelia bavariensis are more common in Europe, Asia, and other regions [

1]. If untreated, the bacteria can spread from the skin to the heart, joints, and nervous system. A recent case in Korea involved a 72-year-old man who died from

B. afzelii infection, transmitted by a tick bite. The bacteria were identified using Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) of the 5S-23S intergenic spacer region (IGS) [

2]. Other studies also identified

B. afzelii and

B. garinii in various sampling areas in Korea and from hard ticks [

3,

4,

5,

6] and patients with Lyme disease in Japan [

7,

8]. In Malaysia,

B. yangtzensis was isolated from

I. granulatus ticks discovered on rodents in Selangor’s recreational forests and Sarawak’s oil palm plantations [

9,

10].

B. yangtzensis had been identified in rodents and ticks in China and Japan [

11] while The first case of

B. yangtzensis infection in humans was reported in Korea [

12]. Seroprevalence studies in Malaysia reveal 16.3% of IgM and 3.3% of IgG in 153 patients with infectious disease symptoms, while 8.1% of Peninsular Malaysian aborigines were reactive to

B. burgdorferi s.l. [

13].

Outer surface protein A (OspA), a 31 kDa lipoprotein, is expressed on the outer membrane of

Borrelia when the bacteria reside in the tick gut. OspA plays an essential role in tick colonization, serving as a tick midgut adhesin by binding to the tick receptor TROSPA, whose expression is upregulated during tick feeding and downregulated during tick engorgement [

14,

15]. Upregulating OspA expression facilitates the establishment of

B. burgdorferi in the gut for transmission to a new vertebrate host during a subsequent blood meal. The OspA protein has a significant role in the early stage of LD pathogenesis and their sequence conservation across Borrelia species especially in the C-terminal domain [

16,

17,

18]. The C-terminal domain is highly conserved across Borrelia pathogenic species and plays an important role in induced immune tolerance, induction of the inflammatory response through TLR2, and host immunologic recognition [

16,

19]. Thus, this OspA protein is a potential candidate for direct detection of

Borrelia in patients with LD, and for the surveillance study of

Borrelia transmission in wild ticks and their animal hosts. Here, we present methods for producing soluble OspA at high yields using a bacterial expression system and evaluate its reactivity against a commercial monoclonal OspA antibody.

2. Materials and Methods

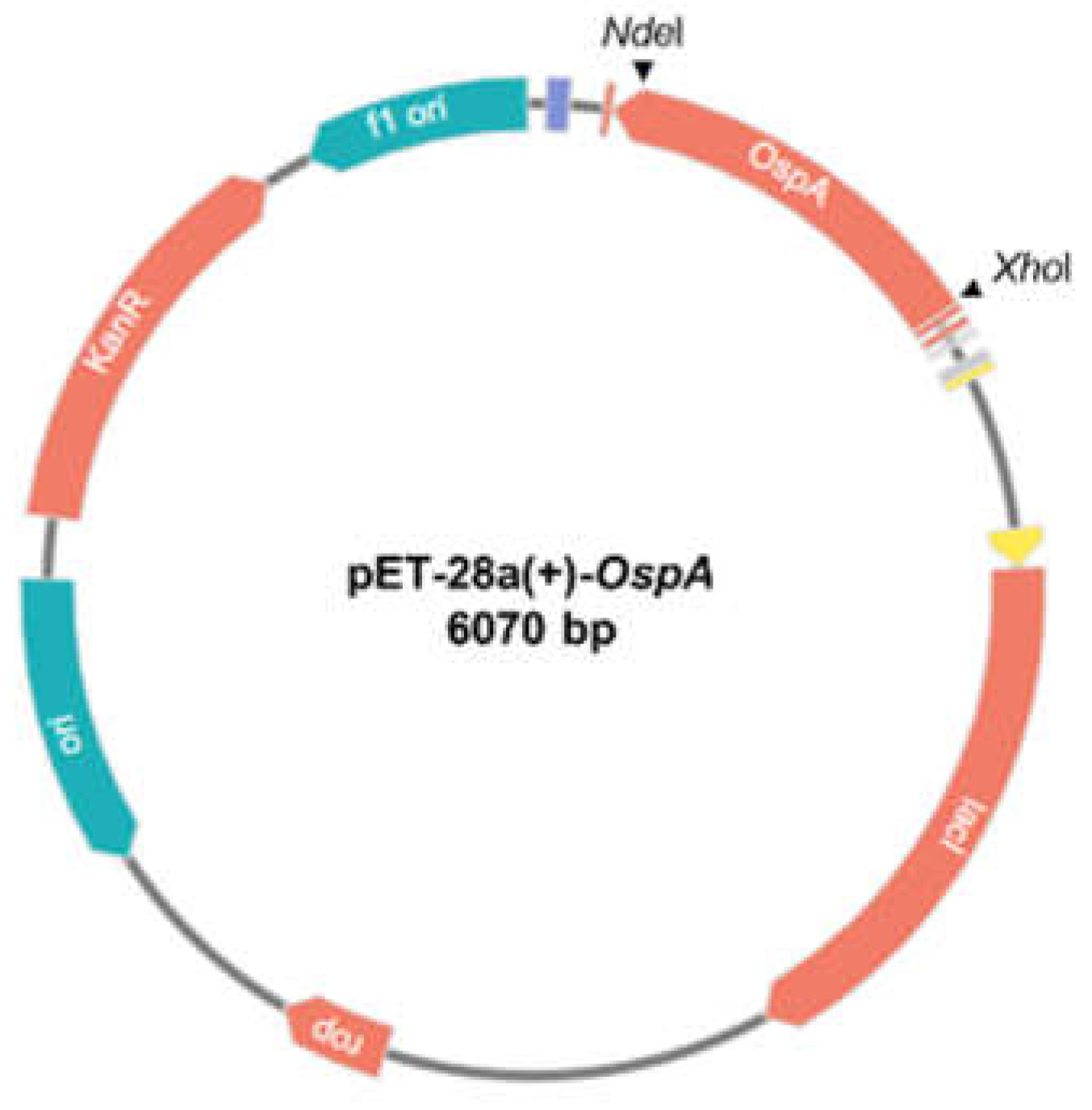

2.1. Preparation of OspA Expression Plasmid

The pUC-IDT plasmid (IDT, USA) with full-length of Borrelia afzelii OspA strain BO23 gene (accession number: CP018263.1) was chemically synthesized with NdeI (NEB, USA) restriction site at the 5’-end and an XhoI (NEB, USA) restriction site at the 3’-end. The plasmid was maintained in One Shot™ TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The pUC-IDT-OspA and pET-28a(+) plasmid (Novagen Millipore, United States) were first digested with NdeI and XhoI restriction enzymes, then separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, prior to their extraction from agarose gel. The purified OspA gene and pET-28a(+) were then mixed (3:1) and allowed to ligate at 25 °C for 1 h. The ligated mixture was further mixed with competent E. coli TOP10 and equilibrated on ice. Subsequently, heat shock was applied at 42 °C for 30 seconds, followed by equilibration on ice. After adding 250 μL of S.O.C medium, they were incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 1 h. The transformant was spread on LB agar plate containing 100 μg/mL of ampicillin prior to incubation at 37 °C for 16 h. A single cell line was obtained from a single colony. To confirm successful gene cloning, the recombinant plasmid was verified by sequencing with specific primers for the T7 promoter and T7 terminator. The pET-28a(+)-OspA plasmid used for protein expression in the subsequent experiments.

2.2. Optimization of OspA Expression

The transformed One Shot BL21 Star (DE3) strain was then cultured at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm in 10 mL of LB broth containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) until the optical density (OD) 600 reached 0.7. The OD600 values were measured using a UV-Vis Eppendorf Biospectrometer. An experiment was performed to determine the optimal conditions for OspA expression at eight different induction times (0 hr, 1 hr, 2 hrs, 3 hrs, 4 hrs, 5hrs, 6 hrs, and 16 h), two types of growth media (Luria broth and 2X YT) and three concentration of glucose (0.2% (w/v), 0.4% (w/v) and 1.0% (w/v)). Protein expression was induced using 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 x g for 20 min at 4°C. The obtained pellet was resuspended with 30 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 20 mM Imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) triton X-100, pH 8.0; protease inhibitor cocktail; 20 µg/mL lysozyme) for 1 L culture. The lysed pellet was incubated on ice for 1 h and then sonicated (10’ burst and 10’ rest) using a Q125 Sonicator (Qsonica, Newtown, CT) with a 3.175 mm diameter probe at a frequency of 20 kHz and 50% amplitude. Alternatively, the pellet was lysed using B-PER Complete Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent following the manufacture’s protocol. Briefly, the pellet was mixed with B-PER reagent (5 mL/g pellet) and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. The cell lysates were collected at 16,000 x g for 20 minutes at 4°C to separate soluble proteins (supernatant) from insoluble proteins (pellet). The supernatants were analysed using SDS-PAGE. To induce over-expression of OspA, a transformed One Shot BL21 Star (DE3) strain was cultured in 200 mL of LB broth containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and 0.2% glucose until OD600 reached 0.7. The bacterial culture was then incubated at 37 °C for 5 hrs under 0.5 mM IPTG.

2.3. Purification of Recombinant OspA

The supernatant was pooled and filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter to prepare for gravity flow affinity chromatography. The HisTrap HP column (Cytiva, Sweden) was equilibrated with 5CV binding buffer (20 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0). The prepared sample was loaded onto a column to bind the OspA protein to the resin. After washing with 5CV binding buffer, the protein was eluted with 5CV elution buffer (20 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0). The eluted protein was concentrated and buffer exchanged into 1X PBS (pH 7.4) using an Amicon 10K cutoff filter (Merk Millipore, USA). Protein was quantified using Quick Start™ Bradford Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad, USA). The purified protein was stored at -20°C until use.

2.4. Protein Reactivity Using Monoclonal Antibody

The reactivity of OspA to a commercial Borrelia burgdorferi OspA monoclonal antibody (clone 5015) was used to check the protein epitope functionality. The purified OspA protein (50 µg) and its crude extract (dilute 1:5 in PBS) were loaded into 12% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue stain (Bio-Rad, USA) and InVision His-tag In-Gel Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). For the western blot, the transferred protein onto the nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with 1% (v/v) BSA in 0.2% (v/v) PBST-20. The OspA antibody was diluted 1:1000 in PBST, and the secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse was diluted 1:5000 in PBST. The signal was developed using the Peroxidase Stain DAB Kit (Nacalai, Japan). The protein band from polyacrylamide gel was out-sourced to a local company (Apical Scientific Sdn Bhd) for MALDI-TOF/TOF analysis to check for the protein sequence and molecular weight determination.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of Recombinant OspA Plasmid

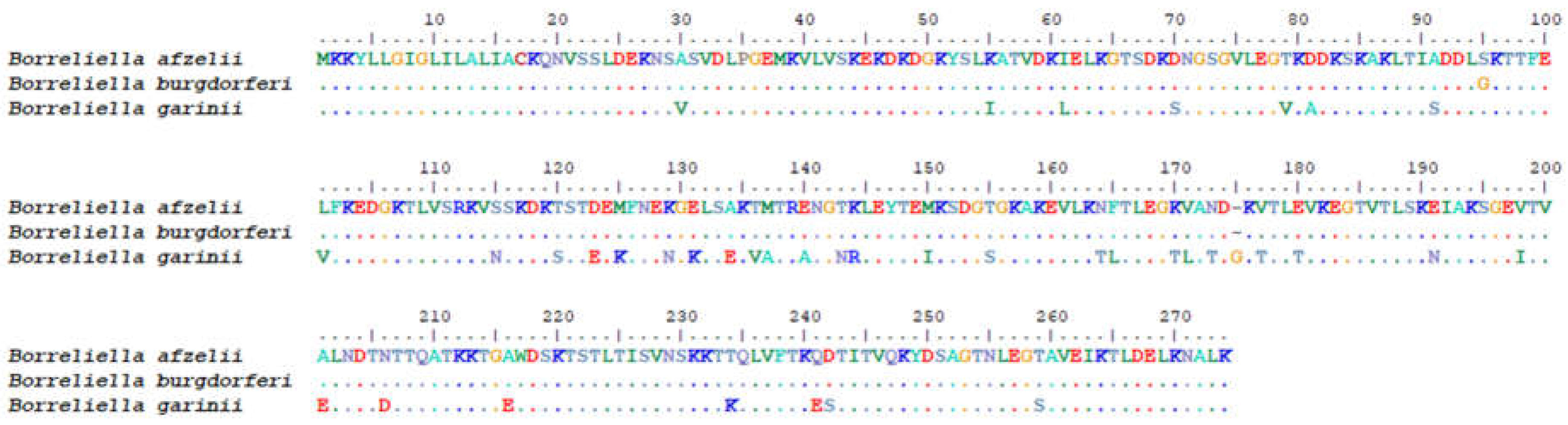

Sequencing of the OspA plasmid (

Figure 1) using the T7 promoter revealed a 100% match with B. afzelii strain BO23 (CP018263.1) and B. afzelii strain PKo (CP000396.1) when aligned using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Comparison with other Borrelia strains in the database showed 99.48% identity with B. burgdorferi (X70365.1), 87.53% identity with B. garinii strain Khab 722 (AY502603.1), and 87.24% identity with B. bavariensis strain A104S (CP058814.1). Analysis of the amino acid sequence using BLASTx confirmed that the cloned plasmid had 100% identity with B. afzelii, 99.61% identity with B. burgdorferi, and 84.88% identity with B. garinii, as showed by ClustalW alignment (

Figure 2). Thus, we confirmed the successful construction of the pET-21a(+)-OspA plasmid for the production of recombinant OspA protein. The isoelectric point (pI) of the OspA protein was estimated to be 8.60, with a molecular weight of 30,211.95 g/mol.

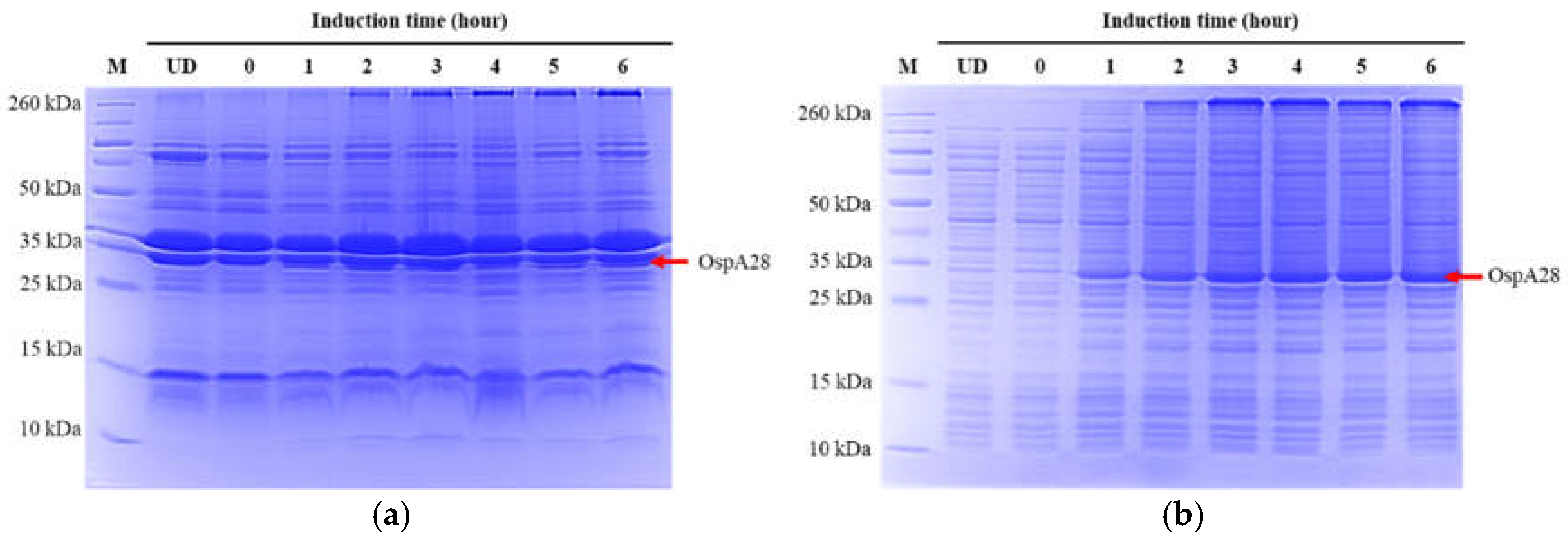

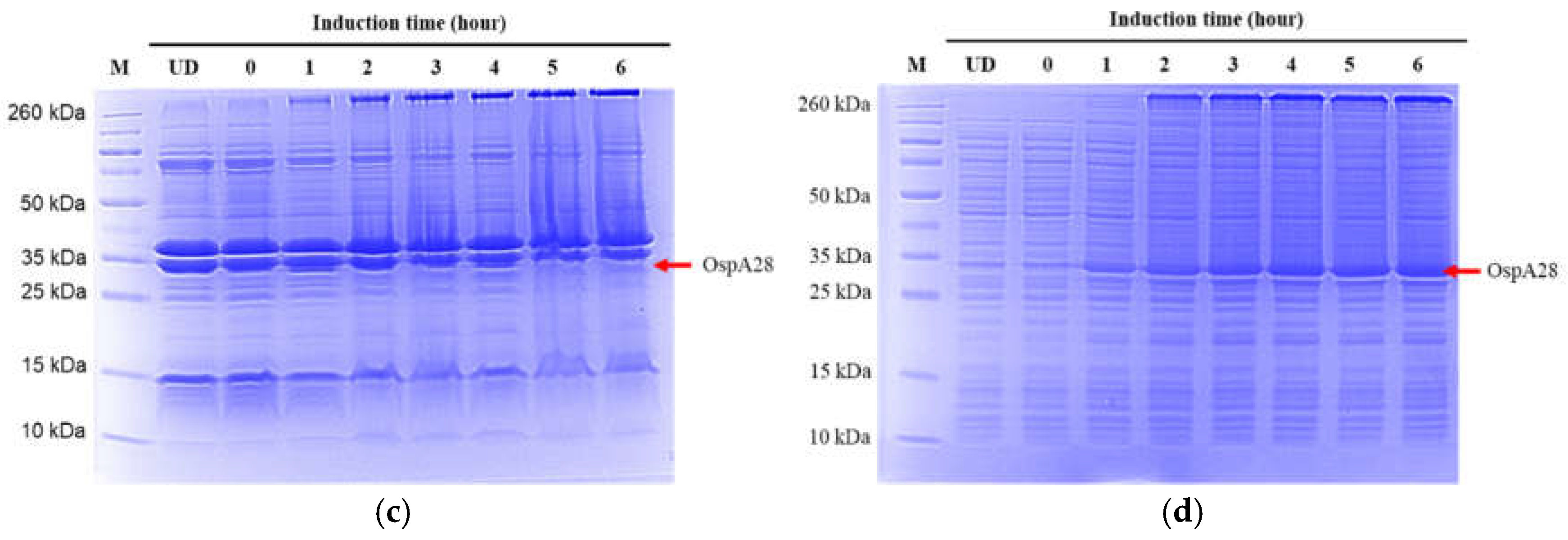

3.2. Optimization of Recombinant OspA Protein Expression

The subcloned pET-28a(+)-OspA plasmid, which was initially present in

E. coli TOP10, was introduced into the

E. coli Star (DE3) strain. Several expression conditions were explored to determine the optimal production of OspA. Initially, expression in normal LB broth were tested at various induction times (0 hr, 1 hr, 2 hrs, 3 hrs, 4 hrs, 5 hrs, and 6 hrs) following an induction with 0.5 mM IPTG, at 200 rpm and 37 °C. Our results showed that OspA protein was highly expressed in the soluble form in the supernatant, with levels increasing progressively with longer induction times compared to the pellet (

Figure 3a,b). OspA expression in LB broth supplemented with 0.2% glucose were also assessed at different induction times. The gel images revealed that protein expression did not differ from that in normal LB broth (

Figure 3c,

d).

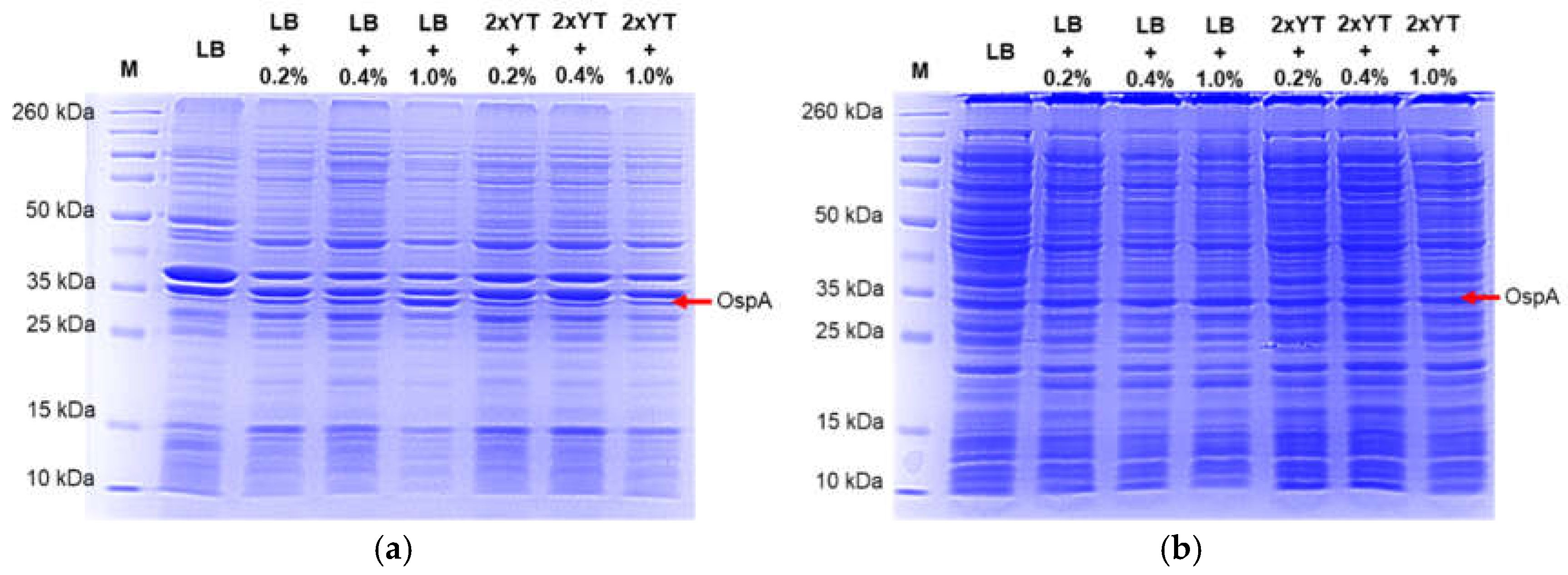

Additionally, we conducted protein expression experiments using both LB and 2xYT broths with varying glucose concentrations (0.2%, 0.4%, and 1%) and induced for 16 hours at 37 °C with low agitation (120 rpm). We observed that extending the induction time to 16 hours resulted in increased production of non-specific proteins and a decreased yield of OspA (see

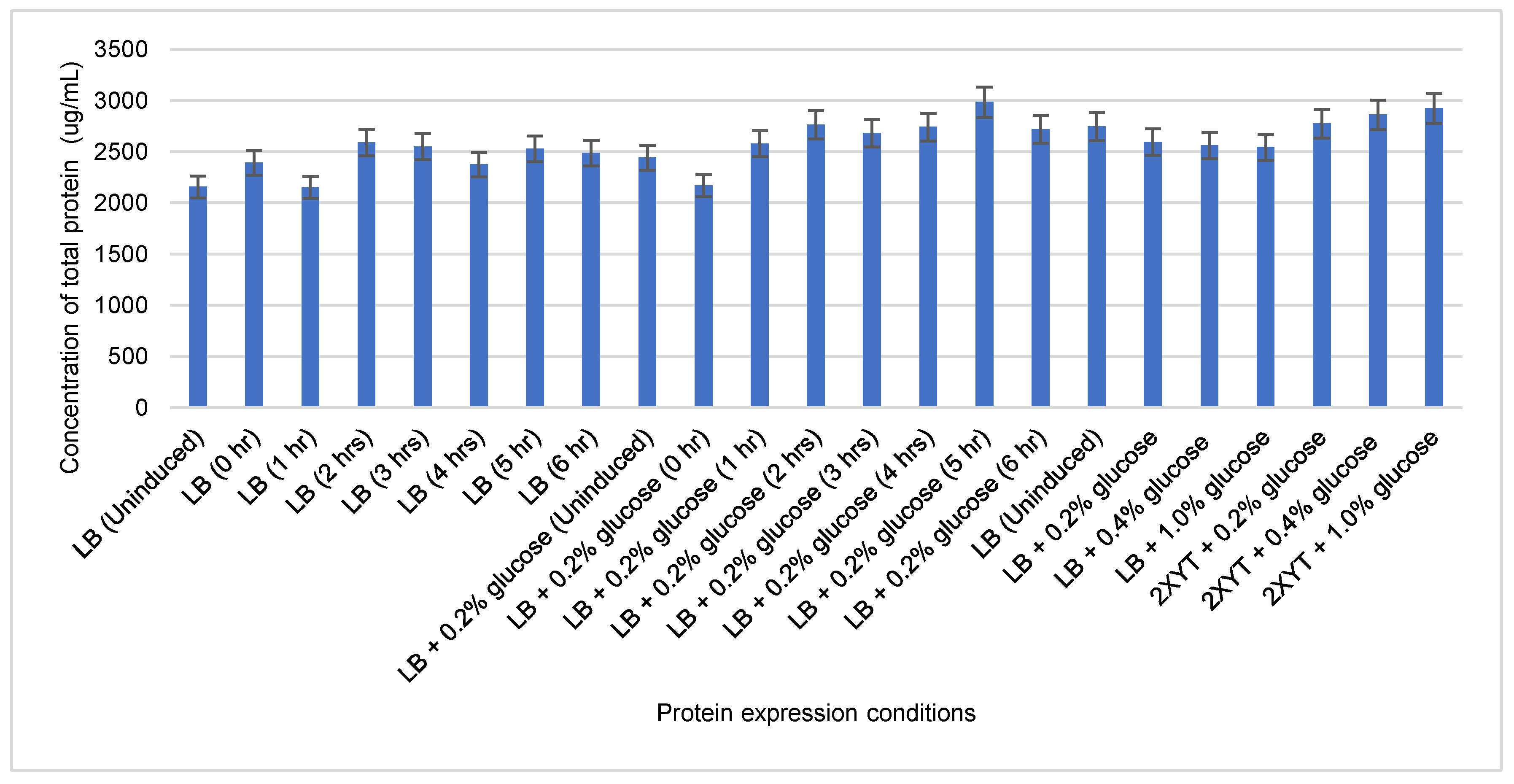

Figure 4a,b). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in OspA expression between LB and 2xYT broths or among the different glucose concentrations compared to uninduced LB broth. This suggests that longer incubation times can lead to a basal level of protein expression, even in the absence of IPTG induction. Quantification of the total protein lysate using the Bradford assay indicated that the highest yield of OspA protein was achieved in LB broth with 0.2% glucose, incubated at 37 °C and induced for 5 hours (

Figure 5).

3.3. Purification of Recombinant OspA

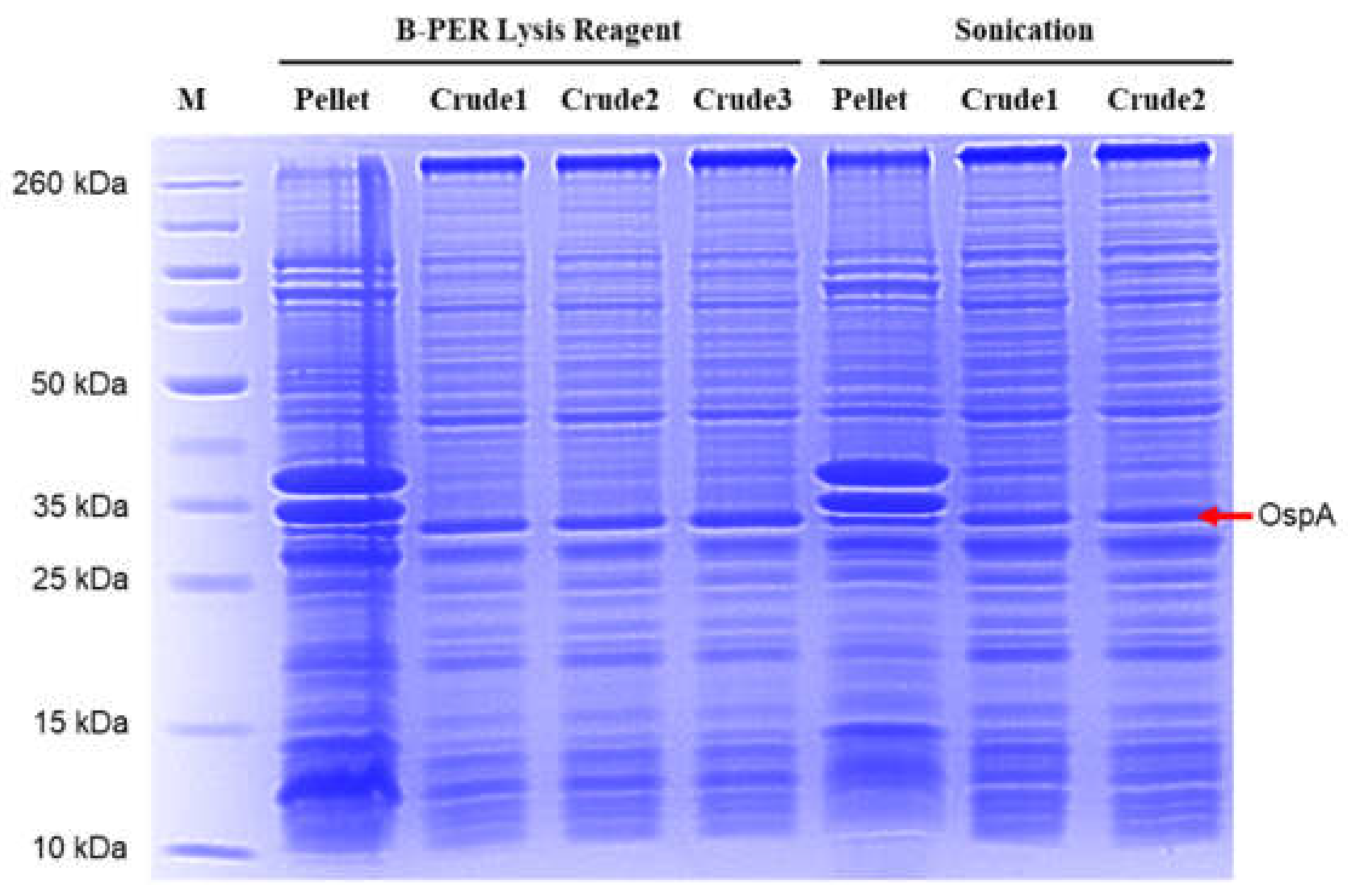

The OspA protein was expressed using an optimized condition: 0.5 mM of IPTG for 5 hours at 37 °C. Bacteria were grown in 100 mL cultures, and the pellets were subjected to lysis. In this study, two methods for bacterial cell lysis were compared: a physical method using a sonicator and a reagent-based method using B-PER Complete Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent. Gel analysis of the crude extracts demonstrated that both methods effectively lysed the bacterial cells (

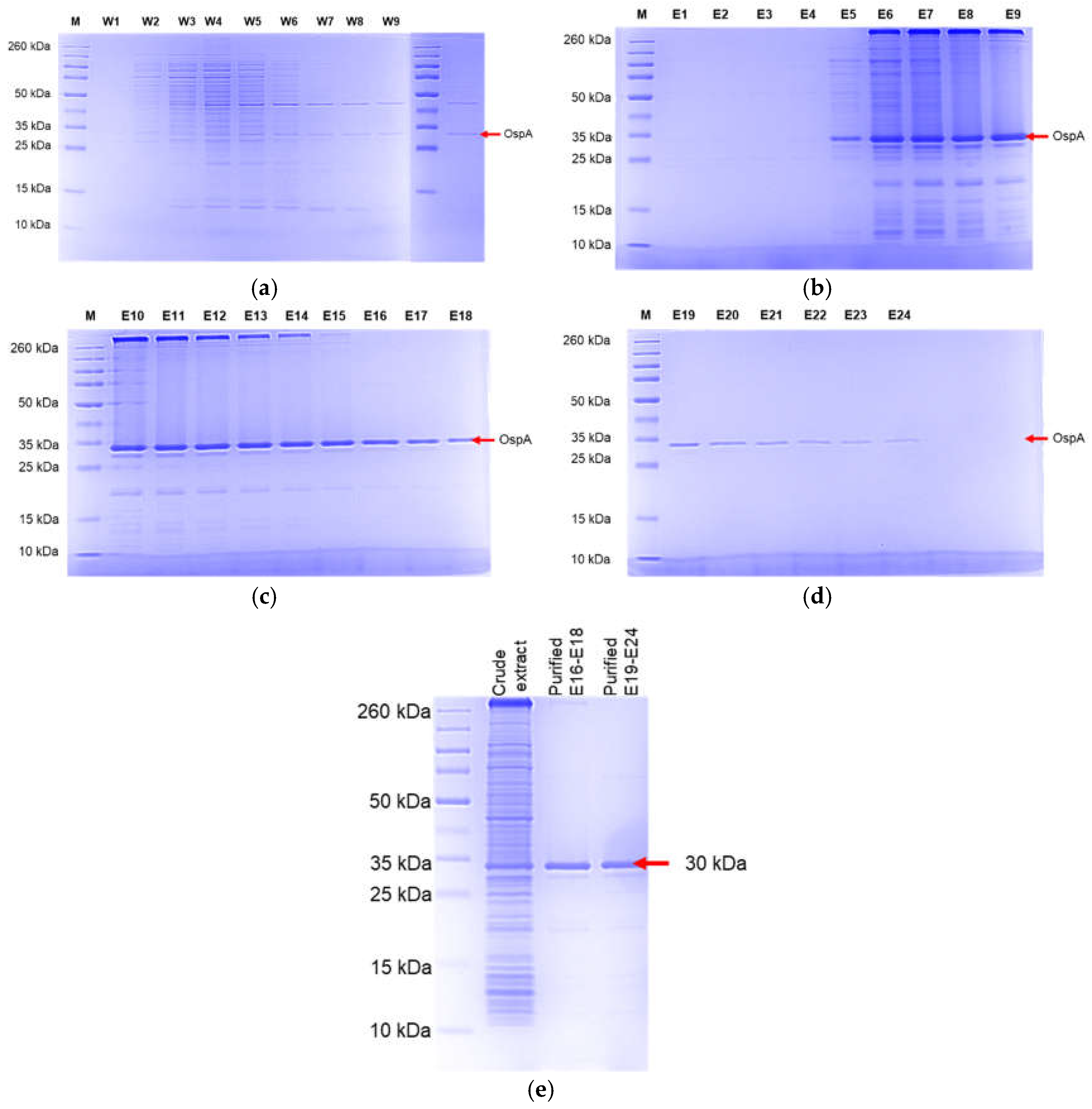

Figure 6). However, the B-PER lysis buffer slightly reduced the occurrence of non-specific bands compared to the sonication method. Recombinant OspA protein was purified using a pre-pack HisTrap Ni-NTA column. After washing, the protein was eluted by adding an elution buffer. The eluted fractions of E16 and above showed increasing purity (

Figure 7a–d). The fractions of E16-E18 and E19-E24 were pooled as two proteins fractionates. These fractionates were concentrated and buffer exchanged using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). From the gel image, we judged that the purity of purified OspA is over 90% compared to crude extract (

Figure 7e). The yield of purified OspA protein was obtained at approximately 12 mg/mL from a 200 mL culture.

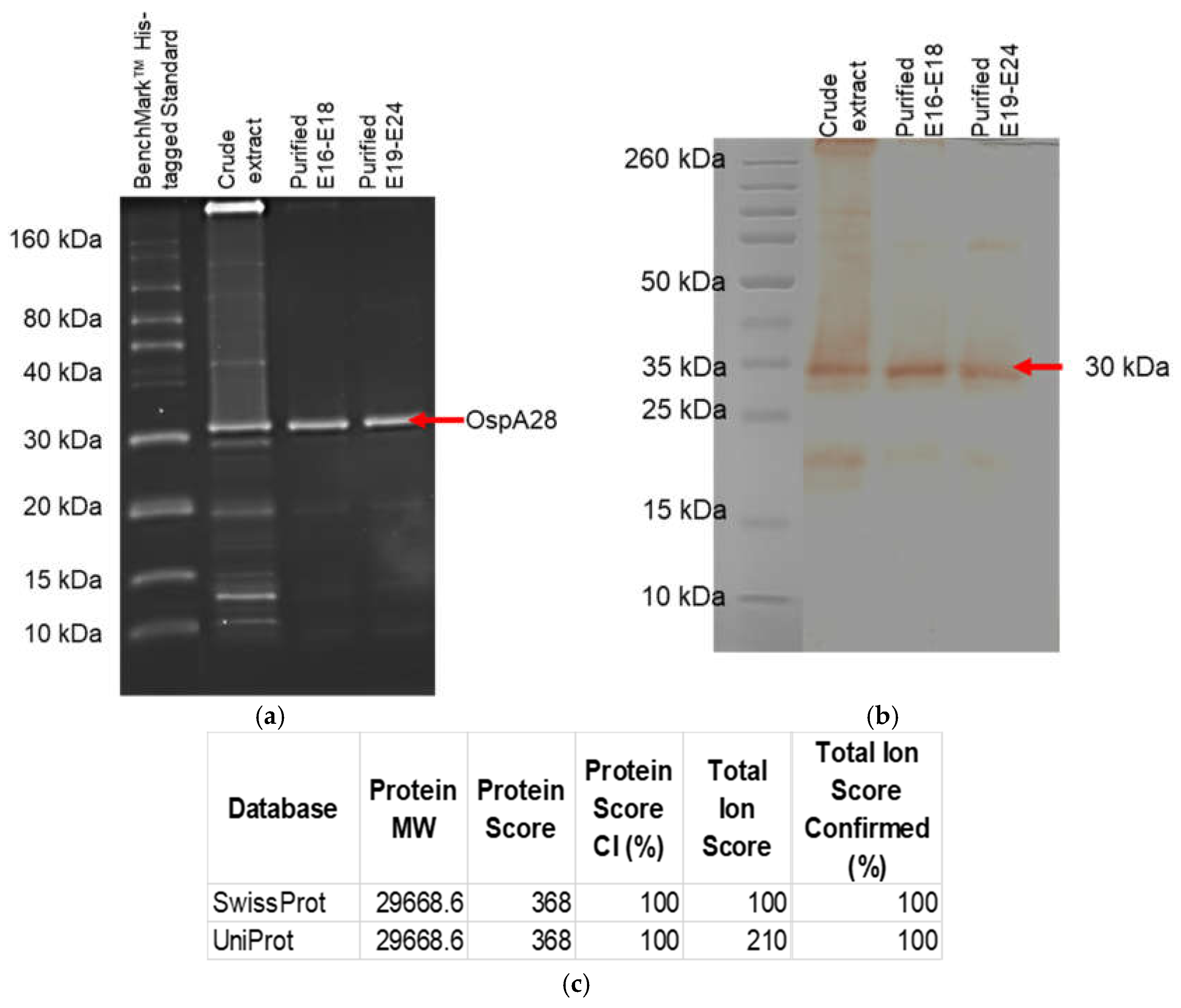

3.4. Reactivity Analysis of Expressed Recombinant OspA

The expressed protein reactivity and functionality were evaluated using commercialized

Borrelia burgdorferi OspA monoclonal antibody (clone 5015) and InVision His-tag In-Gel Stain. The direct stain gel with InVision His-tag In-Gel Stain showed an intact histidine tag incorporated into the translated protein (

Figure 8a). While western blot analysis showed that the protein was reactive to the OspA monoclonal antibody (

Figure 8b). The gel stain with InVision His-tag In-Gel Stain also showed the protein is highly purified (over 90% judged by the naked eye) compared to the crude extract. The band size of the protein was approximately ~30 kDa in the presence of the histidine tag with 100% similarity with

B. afzelii OspA in the database (

Figure 8c).

4. Discussion

Borrelia OspA plays a crucial role in the early stages of LD pathogenesis by facilitating bacterial colonization in the tick midgut. Its sequence conservation across

Borrelia species especially in the C-terminal domain makes it a prime candidate for diagnostic and vaccine research. In this study, we optimized the production of full-length recombinant OspA using an

E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) bacterial expression system, which offers several advantages over eukaryotic systems, including cost-effectiveness, shorter production time, and higher protein yields as been previously proposed to optimise protein expression [

20]. Previous studies reported that the full length of OspA was failed to be expressed in bacterial expression systems as it produced low yield and was associated with the insoluble form [

1,

21]. In some studies, a truncated form of OspA was constructed by eliminating the lipidation signal sequence and the adjacent cysteine residue that encompasses the first 17 amino acids residue to increase protein solubility and yield [

22].

In the current study, we successfully cloned the full-length OspA gene into the pET-28a(+) expression vector under the control of a strong T7 promoter, leading to efficient expression of OspA. Similar to other studies that have utilized the pET system for protein expression, our study demonstrated the high utility of this system for producing soluble, functional proteins in bacterial hosts. Compared to earlier expression systems, the choice of BL21 Star (DE3) provided additional benefits, particularly in handling codon usage biases that can impact the expression of non-bacterial proteins [

23]. Our optimization experiments revealed that the highest yield of soluble OspA was achieved when induced with 0.5 mM IPTG in LB broth containing 0.2% glucose at 37°C for 5 hours. The addition of glucose can significantly reduce the inducibility of

E. coli which can lead to an increase in the yield of expressed protein [

24]. Interestingly, the addition of glucose to the media did not significantly alter OspA yield. In terms of lysis methods, we compared sonication with B-PER lysis buffer and found that B-PER resulted in fewer non-specific bands, indicating improved purity. The yield of purified OspA protein was obtained at approximately 12 mg/mL from a 200 mL culture. The protein purity was estimated to be above 90% compared to the crude extract when obtained in a single step through affinity chromatography.

One of the key outcomes of this study was the high reactivity of the purified OspA protein with monoclonal antibodies, demonstrating its retention of functional epitopes even after being linearized. This is crucial for its use in developing diagnostic tools for LD and potentially as a vaccine antigen. In this study, we utilised the commercial

B. burgdorferi OspA monoclonal antibody, clone 5015 that used whole bacterial lysate of

B. burgdorferi. The reactivity of this antibody to

B. afzelii OspA protein might probably bind to a conserved region of the OspA protein. Other monoclonal antibody clone 0551 has been reported to be able to bind highly conserved epitope (VFTK amino acid) of OspA protein across the

Borrelia species [

25]. In conclusion, this study successfully cloned, purified, and evaluated the functionality of the expressed

B. afzelii OspA protein. This study can provide a platform for the development of diagnostic assay and vaccine in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.A.N.K; Formal analysis, N.A.A.N.K; Funding acquisition, N.A.A.N.K; Investigation, N.A.A.N.K; Methodology, N.A.A.N.K; Project administration, N.A.A.N.K; Resources, N.A.A.N.K; Writing – original draft, N.A.A.N.K; Writing – review & editing, N.A.A.N.K, C.I.W, J.M.Z, K.M.F.M and M.A.

Funding

This work is funded by the Ministry of Health, Malaysia, Grant No. (NMRR ID: NMRR-21-02063-AVY; 21-087).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health, Malaysia, for his permission to publish this article. We would also like to thank Mr. Affendi Omar from the Inborn Errors of Metabolism & Genetics Unit, Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Research Centre, IMR, for allowing us to use the Q125 Sonicator.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kamp, H.D.; Swanson, K.A.; Wei, R.R.; Dhal, P.K.; Dharanipragada, R.; Kern, A.; Sharma, B.; Sima, R.; Hajdusek, O.; Hu, L.T.; et al. Design of a broadly reactive Lyme disease vaccine. npj Vaccines 2020, 5, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.-J.; Kang, T.; Park, H.-J.; Jang, W.-J. Molecular Typing on Human Blood Reveals the Borrelia afzelii Infection in Korea. Infect. Chemother. 2023, 55, 500–504. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.G.; Hwang, D.J.; Park, J.W.; Ryu, M.G.; Kim, Y.; Yang, S.-J.; Lee, J.-E.; Lee, G.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, J.S.; et al. Distribution and pathogen prevalence of field-collected ticks from south-western Korea: a study from 2019 to 2022. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, T.-K.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, H.I. Geographical Distribution of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ticks Collected from Wild Rodents in the Republic of Korea. Pathogens 2020, 9, 866. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.M.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, D.-M.; Park, J.W.; Chung, J.K. First report of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto detection in a commune genospecies in Apodemus agrarius in Gwangju, South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, S.-H.; Shin, S.; Kwak, D. Molecular Identification of Borrelia spp. from Ticks in Pastures Nearby Livestock Farms in Korea. Insects 2021, 12, 1011. [CrossRef]

- Okado, K.; Moumouni, P.F.A.; Lee, S.-H.; Sivakumar, T.; Yokoyama, N.; Fujisaki, K.; Suzuki, H.; Xuan, X.; Umemiya-Shirafuji, R. Molecular detection of Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) and Rickettsia spp. in hard ticks distributed in Tokachi District, eastern Hokkaido, Japan. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2021, 1, 100059. [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M., et al., Comparative Studies on Borrelia afzelii Isolated from a Patient of Lyme Disease, Ixodes persulcatus Ticks, and Apodemus speciosus Rodents in Japan. 1994. 38(6): p. 413-420.

- Khoo, J.J.; Ishak, S.N.; Lim, F.S.; Mohd-Taib, F.S.; Khor, C.S.; Loong, S.K.; AbuBakar, S. Detection of a Borrelia sp. From Ixodes granulatus Ticks Collected From Rodents in Malaysia. J. Med Èntomol. 2018, 55, 1642–1647. [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.C.C., et al., Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi Sensu Lato and Relapsing Fever Borrelia in Feeding Ixodes Ticks and Rodents in Sarawak, Malaysia: New Geographical Records of Borrelia yangtzensis and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2020. 9(10): p. 846.

- Margos, G.; Chu, C.-Y.; Takano, A.; Jiang, B.-G.; Liu, W.; Kurtenbach, K.; Masuzawa, T.; Fingerle, V.; Cao, W.-C.; Kawabata, H. Borrelia yangtzensis sp. nov., a rodent-associated species in Asia, is related to Borrelia valaisiana. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 3836–3840. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.M.; Yun, N.R.; Kim, D.-M. Case Report: The First Borrelia yangtzensis Infection in a Human in Korea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 106, 45–46. [CrossRef]

- Chee-Sieng, K., et al., Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi among the indigenous people (Orang Asli) of Peninsular Malaysia. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 2019. 13(05).

- Pal, U.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Montgomery, R.R.; Ramamoorthi, N.; Desilva, A.M.; Bao, F.; Yang, X.; Pypaert, M.; Pradhan, D.; et al. TROSPA, an Ixodes scapularis Receptor for Borrelia burgdorferi. Cell 2004, 119, 457–468. [CrossRef]

- Tilly, K.; Bestor, A.; Rosa, P.A. Functional Equivalence of OspA and OspB, but Not OspC, in Tick Colonization by Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 1565–1573. [CrossRef]

- E Schutzer, S.; Coyle, P.K.; Dunn, J.J.; Luft, B.J.; Brunner, M. Early and specific antibody response to OspA in Lyme Disease.. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 454–457. [CrossRef]

- Zumstein, G.; Fuchs, R.; Hofmann, A.; Preac-Mursic, V.; Soutschek, E.; Wilske, B. Genetic polymorphism of the gene encoding the outer surface protein A (OspA) of Borrelia burgdorferi. Med Microbiol. Immunol. 1992, 181, 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Luft, B.J.; Dunn, J.J.; Lawson, C.L. Approaches toward the Directed Design of a Vaccine againstBorrelia burgdorferi. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 185, S46–S51. [CrossRef]

- Battisti, J.M.; Bono, J.L.; Rosa, P.A.; Schrumpf, M.E.; Schwan, T.G.; Policastro, P.F. Outer Surface Protein A Protects Lyme Disease Spirochetes from Acquired Host Immunity in the Tick Vector. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 5228–5237. [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.M. and R. Page, Strategies to optimize protein expression in E. coli. Curr Protoc Protein Sci, 2010. Chapter 5(1): p. 5.24.1-5.24.29.

- Dunn, J.J.; Lade, B.N.; Barbour, A.G. Outer surface protein a (OspA) from the lyme disease spirochete, borrelia burgdorferi: High level expression and purification of a soluble recombinant form of OspA. Protein Expr. Purif. 1990, 1, 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Federizon, J.; Frye, A.; Huang, W.-C.; Hart, T.M.; He, X.; Beltran, C.; Marcinkiewicz, A.L.; Mainprize, I.L.; Wills, M.K.; Lin, Y.-P.; et al. Immunogenicity of the Lyme disease antigen OspA, particleized by cobalt porphyrin-phospholipid liposomes. Vaccine 2020, 38, 942–950. [CrossRef]

- Rosano, G.L.; Ceccarelli, E.A. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: advances and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 172. [CrossRef]

- Atroshenko, D.L.; Sergeev, E.P.; Golovina, D.I.; Pometun, A.A. Additivities for Soluble Recombinant Protein Expression in Cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. Fermentation 2024, 10, 120. [CrossRef]

- Magni, R.; Espina, B.H.; Shah, K.; Lepene, B.; Mayuga, C.; Douglas, T.A.; Espina, V.; Rucker, S.; Dunlap, R.; Petricoin, E.F.I.; et al. Application of Nanotrap technology for high sensitivity measurement of urinary outer surface protein A carboxyl-terminus domain in early stage Lyme borreliosis. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 1–22. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).