Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

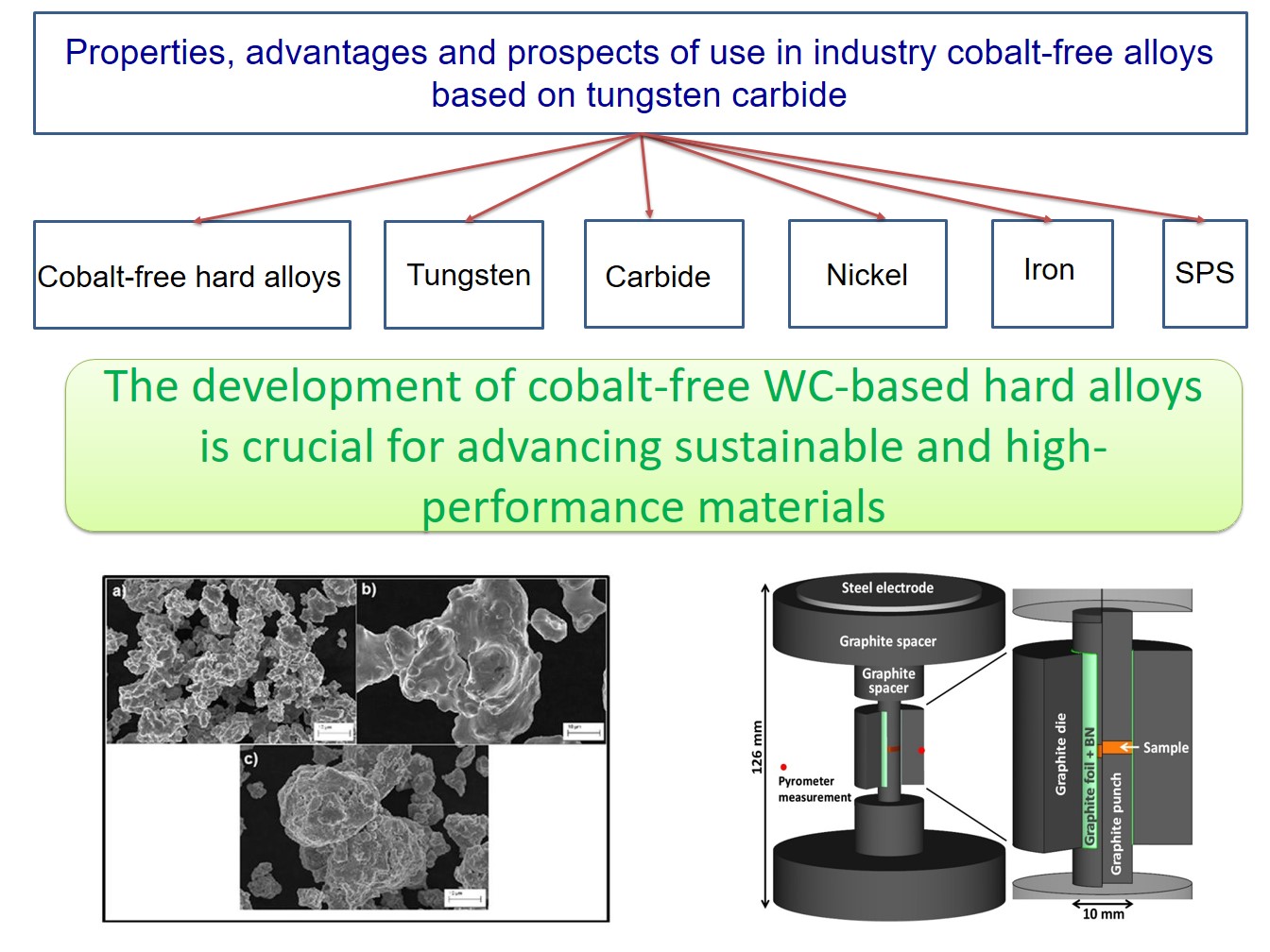

This paper reviews recent advances in the synthesis of cobalt-free high-strength tungsten carbide (WC) composites as sustainable alternatives to conventional WC-Co composites. Due to the high cost of cobalt, limited supply and environmental concerns, researchers are exploring nickel, iron, ceramic binders and nanocomposites to obtain similar or superior mechanical properties. Various synthesis methods such as powder metallurgy, encapsulation, 3D printing and spark plasma sintering (SPS) are discussed, with SPS standing out for its effectiveness in densifying and preventing WC grain growth. The results show that cobaltfree composites exhibit high strength, wear and corrosion resistance, and harsh environment stability, making them viable competitors for WC-Co materials. The use of nickel and iron with SPS is shown to enable the development of environmentally friendly, cost-effective materials. It is emphasized that microstructural control and phase management during sintering are critical to improve material properties. The application potential of these composites covers mechanic

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problems of Cobalt Utilization in Traditional Composites: Resource, Environmental and Economic Aspects

3. Alternative Bonding Materials for Tungsten Carbide-Based Composites

- -

- The binding energies at the WC/Co and WC/ CoNiFe interfaces were calculated according to the first principle, and the binding energy of Co with WC is slightly higher than that of CoNiFe with WC. This suggests that replacing Fe and Ni with part of Co weakens the bonding properties at the WC/Co interface, but the effect is negligible.

- -

- The atomic bond strength at the WC/Co and WC/CoNiFe interfaces is mainly determined by the contribution of the d-electron orbitals of the atoms. According to the difference of charge density and density of states, the atomic bond strength is W-Fe>W-Co>W-Ni. Fe atoms play a major role in the strength of WC/ CoNiFe interface.

- -

- The porosity of WC/CoNiFe carbide is 0.78%, which is much lower than that of WC/Co material. The WC/Co material has non-uniform pore distribution. The highest average hardness and lowest average hardness of WC/Co carbide are 1320 HV and 1182 HV samples with non-uniform hardness distribution. The hardness of WC/ CoNiFe carbide is relatively more uniform, with the highest value of 1192 HV.

4. Technologies for Synthesis of WC Composites

| AM Process | Abbreviation | Other names | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Laser Melting | SLM | Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) |

High dimensional accuracy High geometric freedom Less steps High hardness |

High residual stress Uneven microstructure Carbon loss and evaporation of Co |

| Selective Electron Beam Melting | SEBM | Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion (E-PBF) |

High dimensional accuracy High geometric freedom Less steps High hardness High scan speed |

High residual stress Uneven microstructure Expensive equipment Needs vacuum |

| Binder Jet Additive Manufacturing | BJAM | Binder Jet 3D Printing (BJ3DP) | Uniform microstructure High toughness Low cost Low residual stress |

Complicated processes Large shrinkage Low hardness, moderate strength |

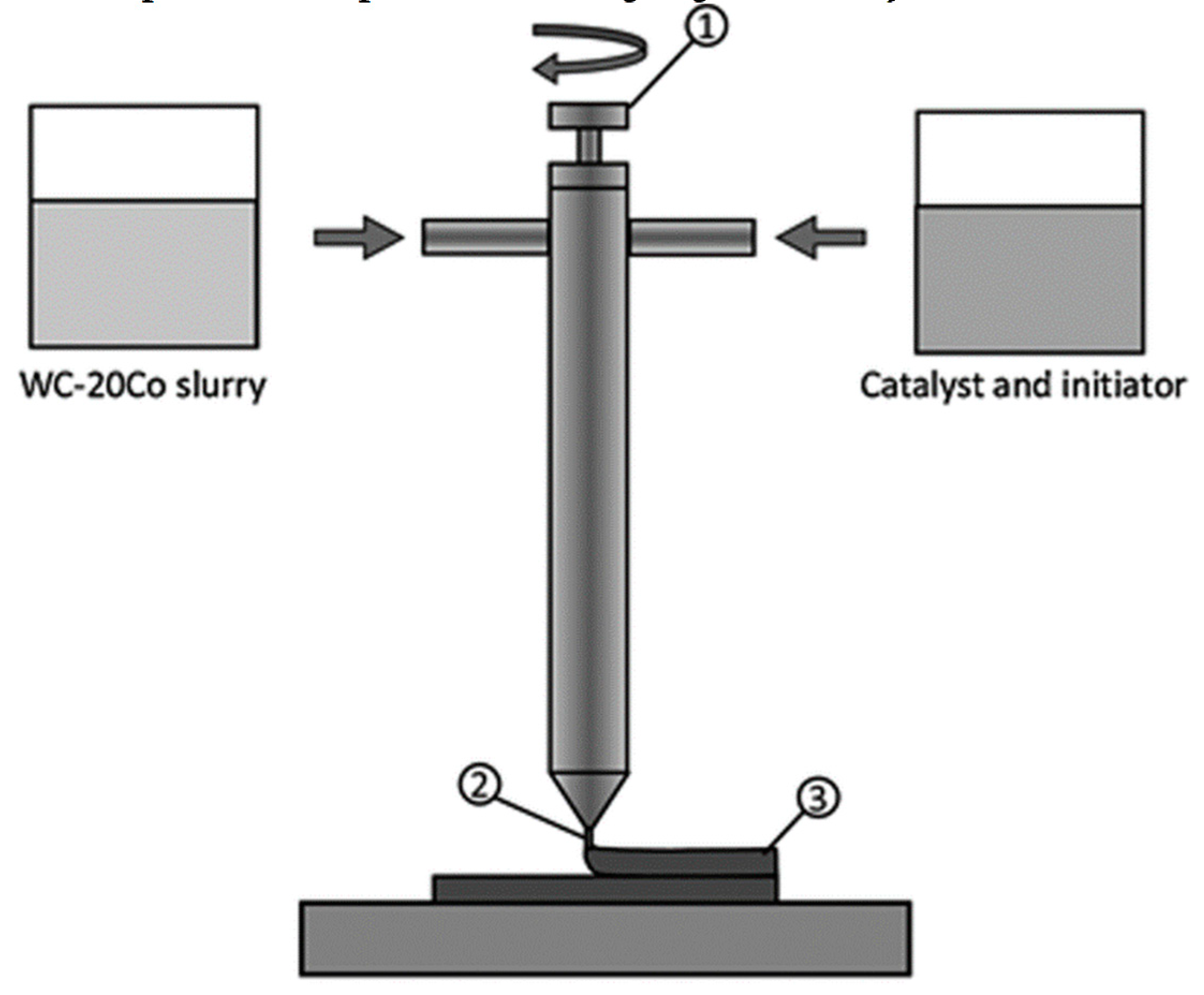

| 3D gel-printing | 3DGP | N/A | Low residual stress Uniform microstructure Low powder requirements No raw material loss |

Complicated processes Large shrinkage |

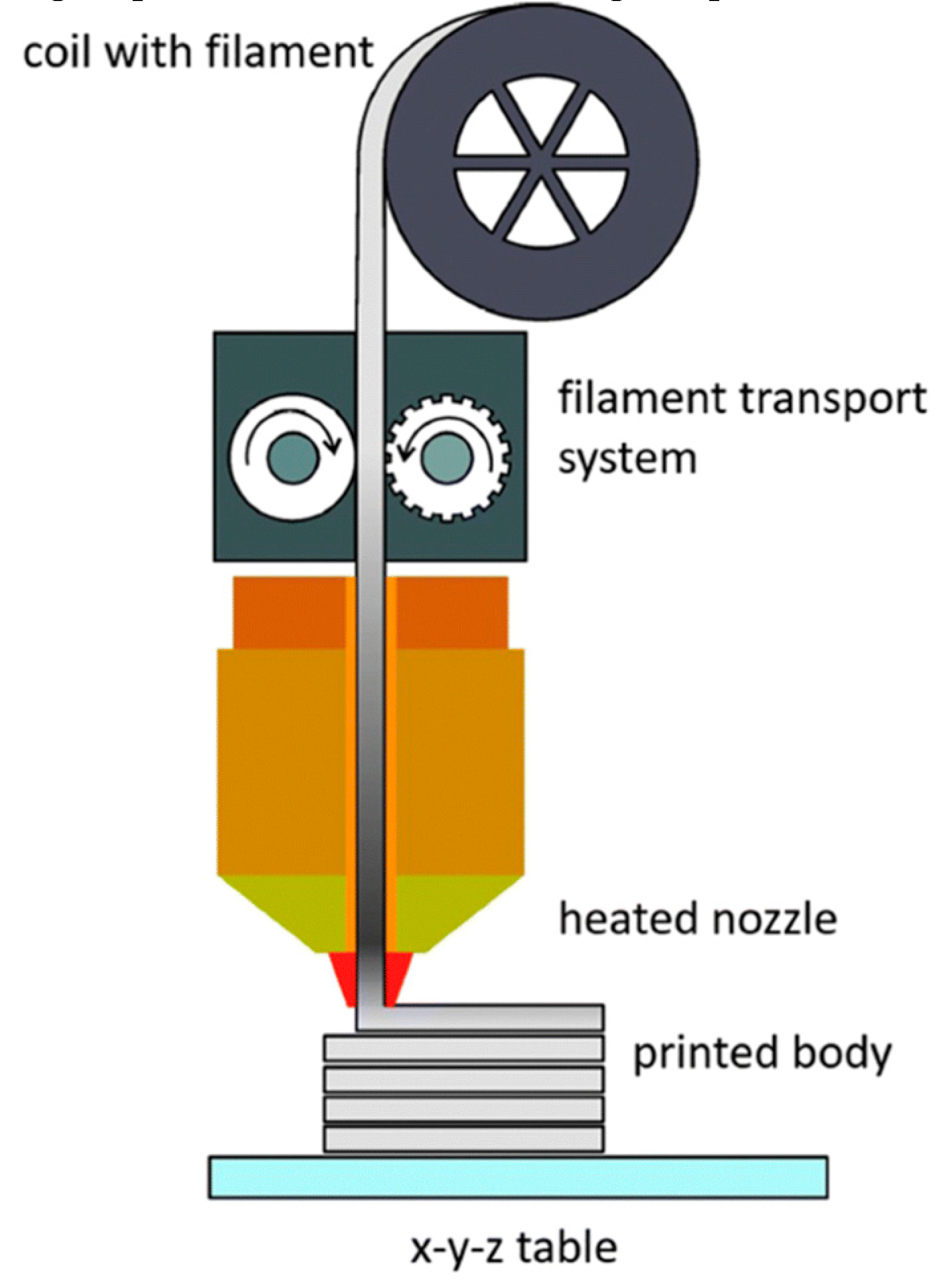

| Fused Filament Fabrication | FFF | N/A | Low residual stress Uniform microstructure Low powder requirements No raw material loss |

Complicated processes Large shrinkage Needs filament fabrication equipment Rough surface |

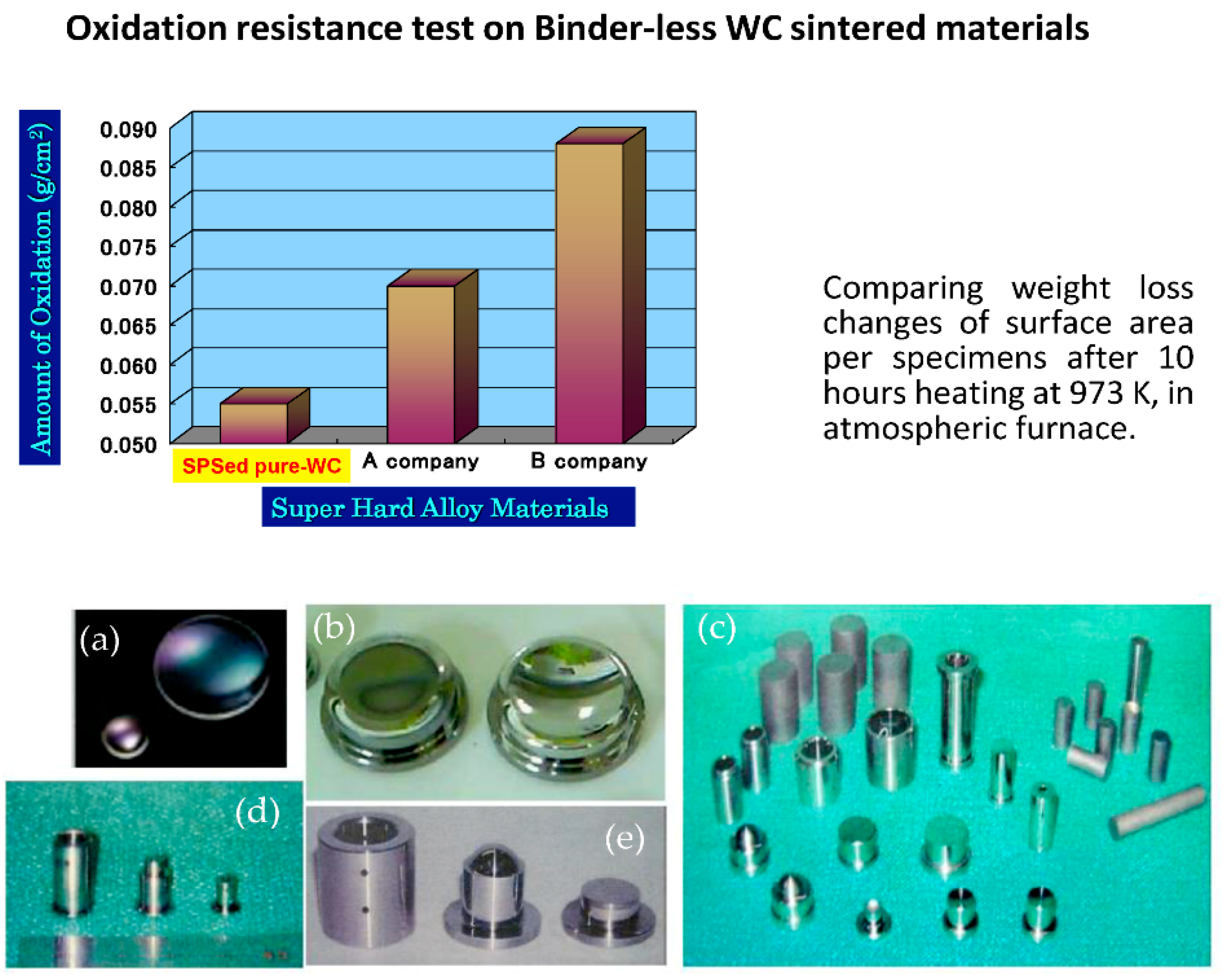

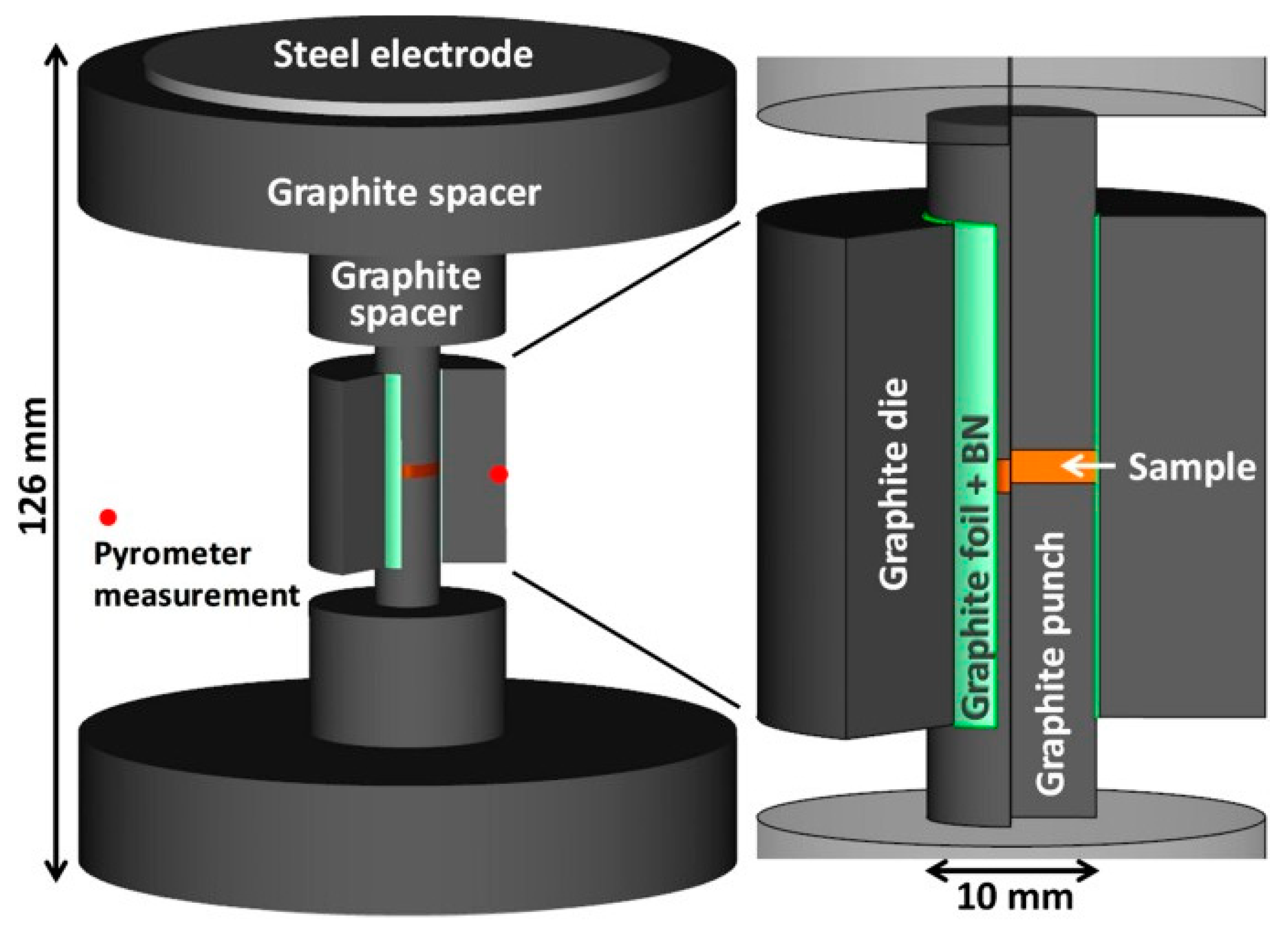

5. SPS Synthesis for WC Sintering

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viswanadham, R. Science of Hard Materials; Springer: Berlin, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shatov, A. V.; Ponomarev, S. S.; Firstov, S. A. Hardness and deformation of hardmetals at room temperature. In Comprehensive Hard Materials; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 647–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatov, A. V.; Ponomarev, S. S.; Firstov, S. A. Fracture and strength of hardmetals at room temperature. Comprehensive Hard Materials; Elsevier: Oxford, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multanov, A. S. Especially coarse-grained WC-Co composites for the equipment of rock-crushing tools for mining machines. Phys. Mesomech. 2002, 5, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, J.; Gong, F.; Ni, X.; Li, Z. Development and Application of WC based Composites Bonded with Alternative Binder Phase. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2018, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Basu, B. Recent developments on WC based bulk composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z. Z.; Koopman, M. C.; Wang, H. Cemented Tungsten Carbide Hardmetal-An Introduction. In Comprehensive Hard Materials; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimenko, N. N.; Efimochkin, I. Y.; Dvoretskov, R. M.; Batienkov, R. V. Production of Fine-Grained Hard Alloys in the WC-Co System (Review). Trudy VIAM 2020, 1(85), 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Z.; et al. A Review on Binderless Tungsten Carbide: Development and Application. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskolkova, T. N. Wear-Resistant Coating on Hard Composite. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 788, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskolkova, T. N. Tungsten carbide is a hard composite with a wear-resistant coating. Proc. Samara Sci. Cent. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2013, 15, (4–2). [Google Scholar]

- Oskolkova, T. N. Improving the wear resistance of tungsten-carbide hard composites. Steel Transl. 2015, 45, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerra, B. L.; Rodriguez, N.; Sánchez, J. M. Comparison of the damage induced by thermal shock in hardmetals and cermets. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2016, 61, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerra, B. L.; Lozada, L.; van den Berg, H.; Wolf, M.; Sánchez, J. M. Comparison of the thermal shock resistance of WC based cemented carbides with Co and Co-Ni-Cr based binders. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2017, 72, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlov, A. S.; Gusev, A. I. Vacuum annealing of nanocrystalline WC powders. Inorg. Mater. 2012, 48, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlov, A.; Gusev, A. I. Peculiarities of vacuum annealing of nanocrystalline WC powders. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2012, 32, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

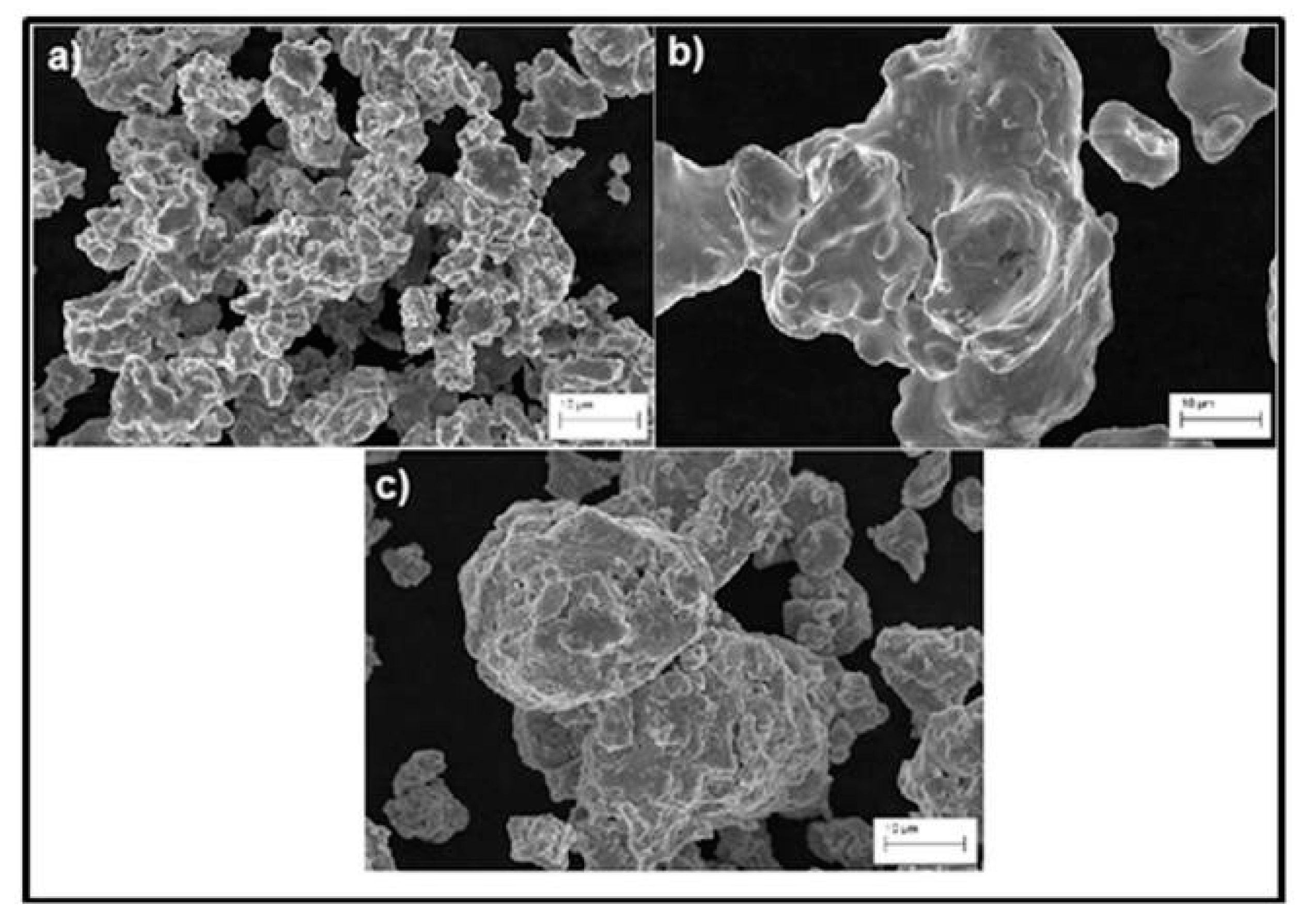

- Kurlov, A. S.; Rempel, A. A. Effect of cobalt powder morphology on the properties of WC-Co hard composites. Inorg. Mater. 2013, 49, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Chen, C.; Yang, W. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2017, 70, 215. [CrossRef]

- Ku, N.; Pittari, J. J.; Kilczewski, S.; et al. Additive Manufacturing of Cemented Tungsten Carbide with a Cobalt-Free Composite Binder by Selective Laser Melting for High-Hardness Applications. JOM 2019, 71, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, R. K.; Dash, T.; Rout, T. K. Preparation of Iron Bonded Tungsten Carbide-Titanium Carbide Composites with Improved Microstructure for Designing Various Harder Components. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 5479–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. T.; Kim, J. S.; Kwon, Y. S. Mechanical Properties of Binderless Tungsten Carbide by Spark Plasma Sintering. In Proceedings of the 9th Russian-Korean International Symposium on Science and Technology (KORUS 2005); IEEE, 2005; pp. 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhai, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Z. Tribological Performance of Binderless Tungsten Carbide Reinforced by Multilayer Graphene and SiC Whisker. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 4817–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards Greater Security and Sustainability. COM/2020/474 final, Brussels. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0474 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Alves Dias, P.; Blagoeva, D.; Pavel, C.; Arvanitidis, N. Cobalt: demand-supply balances in the transition to electric mobility; EUR 29381 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency. Cobalt Substance Infocard by ECHA. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/substance-information/-/substanceinfo/100.028.325 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Lison, D. Human toxicity of cobalt-containing dust and experimental studies on the mechanism of interstitial lung disease (hard metal disease). Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1996, 26, 585–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstead, A. L.; Li, B. Nanotoxicity: emerging concerns regarding nanomaterial safety and occupational hard metal (WC-Co) nanoparticle exposure. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 6421–6433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. C.; Shon, I. J.; Yoon, J.; Doh, J. Consolidation of ultrafine WC and WC-Co hard materials by pulsed current activated sintering and its mechanical properties. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2007, 25, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. C.; Shon, I. J.; Ko, I.; Yoon, J.; Doh, J.; Lee, G. Fabrication of ultrafine binderless WC and WC-Ni hard materials by a pulsed current activated sintering process. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2006, 24, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, B.; Barsoum, M. W. MXenes: Transition Metal Carbides and Nitrides; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H.; Basu, B. WC-MXene Composites: Role of MXene on Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Binderless WC Composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Z. SPS processing of cobalt-free cemented carbide with high-density and fine microstructure. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 296, 117212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Zhou, J. Innovative cobalt-free cemented carbides: Properties and applications. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engqvist, H.; Axén, N.; Hogmark, S. Tribological properties of a binderless carbide. Wear 1999, 232, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engqvist, H.; Beste, U.; Axén, N. The influence of pH on sliding wear of WC based materials. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2000, 18, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human, A. M.; Exner, H. E. Electrochemical behaviour of tungsten-carbide hardmetals. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1996, 209, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human, A. M.; Exner, H. E. The relationship between electrochemical behaviour and in-service corrosion of WC based cemented carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 1997, 15(1-3), 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo-Kupoluyi, O. J.; Tahir, S. M.; Baharudin, B. T. H. T.; Azmah Hanim, M. A.; Anuar, M. S. Mechanical Properties of WC based Hardmetals Bonded with Iron Alloys - A Review. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33(5), 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toller, L. Alternative binder hardmetals for steel turning. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2017, 61, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, L. J. Fundamentals and General Applications of Hardmetals. In Comprehensive Hard Materials; Elsevier, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonny, K.; de Baets, P.; Vleugels, J.; Huang, S.; Lauwers, B. Tribological characteristics of WC-Ni and WC-Co cemented carbide in dry reciprocating sliding contact. Tribol. Trans. 2009, 52, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Sun, L.; Tang, H.; Qu, X. Hot pressing of nanometer WC-Co powder. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2007, 25, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, H. Ultrafine WC-Ni cemented carbides fabricated by spark plasma sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 543-547, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C. B.; Shi, Z.; Su, J. Microstructure and properties of ultrafine cemented carbides: Differences in spark plasma sintering and sinter-HIP. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 427-433, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, T. Effects of partial substitution of copper for cobalt on the microstructure and properties of ultrafine-grained WC-Co cemented carbides. J. Composites Compd. 2018, 43-50, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasali, E.; Sadeghi, A.; Shokouhimehr, M.; Lee, S. Mechanical and microstructural properties of WC based cermets: A comparative study on the effect of Ni and Mo binder phases. Ceram. Int. 2018, 2283-2291, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, I.; Rosso, M. Manufacturing, composition, properties and application of sintered hard metals. In Powder Metallurgy: Fundamentals and Case Studies; Springer, 2017; pp. 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Martínez, E.; Llanes, L. Cemented carbide microstructures: A review. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 40-68, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Moriguchi, H. Development of cemented carbide tools of reduced rare metal usage. Wear 2011, 270, 1431–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z. Investigation of the effect of partial Co substitution by Ni and Fe on the interface bond strength of WC cemented carbide based on first-principles calculations. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 109470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumal, B. B.; Konyashin, I. Faceting/roughening of WC/binder interfaces in cemented carbides: A review. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. P.; Graeve, O. A. Spark plasma sintering as an approach to manufacture bulk materials: Feasibility and cost savings. JOM 2015, 67, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, O.; Gonzalez-Julian, J.; Dargatz, B.; Kessel, T.; Schierning, G.; Räthel, J.; Herrmann, M. Field-assisted sintering technology/spark plasma sintering: Mechanisms, materials, and technology developments. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2014, 16, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lu, J.; Shen, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. The sintering mechanism in spark plasma sintering: Proof of the occurrence of spark discharge. Scr. Mater. 2014, 81, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buravlev, I. Y.; Solokhin, V. A.; Ryabchikov, M. A.; Tikhonovsky, M. A. WC-5TiC-10Co hard metal composite fabrication via mechanochemical and SPS techniques. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2021, 94, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z. Investigation of the effect of partial Co substitution by Ni and Fe on the interface bond strength of WC cemented carbide based on first-principles calculations. SSRN 2024, 4724880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, U. C.; Sunday, A. V.; Christain, E. I.; Elizabeth, M. M. Spark Plasma Sintering of Aluminium Composites—A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 1819–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S. Enhanced uniformity in cobalt-free tungsten carbide composites through encapsulation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 747, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Milman, Y. V. The effect of structural state and temperature on mechanical properties and deformation mechanisms of WC-Co hard composite. J. Superhard Mater. 2014, 36, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H.; Lee, D. K. Effect of encapsulation on the sintering behavior and mechanical properties of cobalt-free WC hardmetals. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2018, 73, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J. H.; Lee, S. Y. Effect of grain size on the properties of cobalt-free WC based hardmetals. J. Composites Compd. 2018, 767, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, T. Development and Application of Binderless Tungsten Carbide Hardmetals. Mater. Des. 2021, 203, 109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; et al. Additive Manufacturing Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, W. E. Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 1917–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, A.; Huang, L.; Du, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J. Effects of metal binder content and carbide grain size on the microstructure and properties of SPS-manufactured WC-Fe composites. J. Composites Compd. 2019, 767, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Ka, G.; Lei, F.; Yang, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, R.; An, L. Oscillatory Pressure Sintering of WC-Fe-Ni Cemented Carbides. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 12727–12731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantseva, N. V.; Mushnikov, N. V.; Popov, A. A.; Sazonova, V. A.; Terent'ev, P. B. Nanoscale Hydrides of Titanium Aluminides. Phys. Eng. High Pressures 2008, 17, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zoli, L.; Vinci, A.; Silvestroni, L.; et al. Rapid Spark Plasma Sintering to Produce Dense UHTCs Reinforced with Undamaged Carbon Fibres. Mater. Des. 2017, 130, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H.; et al. Ultra-Low Temperature Synthesis of Al4SiC4 Powder Using Spark Plasma Sintering. Scr. Mater. 2013, 69, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaali, V.; Ebadzadeh, T.; Zahraee, S. M.; et al. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of WC-TiC-Co Cemented Carbides Produced by Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) Method. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S. I.; Hong, S. H. Microstructures of Binderless Tungsten Carbides Sintered by Spark Plasma Sintering Process. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2003, 356, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantsev, E. A. BBK K390.4ya73-5 L22; BBK Publishing: Moscow, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Taimatsu, H.; Sugiyama, S.; Kodaira, Y. Synthesis of W2C by Reactive Hot Pressing and Its Mechanical Properties. Mater. Trans. 2008, 49, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvil'deev, V. N.; Blagoveshchenskiy, Y. V.; Nokhrin, A. V.; et al. Spark Plasma Sintering of Tungsten Carbide Nanopowders. Nanotechnol. Russ. 2015, 10, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genga, R. M.; Cornish, L. A.; Akdogan, G. Effect of Mo2C Additions on the Properties of Manufactured WC-TiC-Ni Cemented Carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2013, 41, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Songhe, L.; Pan, G.; Wang, D.; Dong, Y.-Y.; Cheng, J.; Ren, G.; Yan, Q. Printability and Properties of Tungsten Cemented Carbide Produced Using Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing with Ti as a Binder. Int. J. Refract. Metals Hard Mater. 2023, 111, 106106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. W.; Kim, Y. W.; Jang, K. M.; et al. Phase Control of WC-Co Hardmetal Using Additive Manufacturing Technologies. Powder Metall. 2022, 65(1), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.-I.; Kim, Y. D.; Jeong, H.; Ryu, S.-S. Material Extrusion-Based Three-Dimensional Printing of WC-Co Alloy with a Paste Prepared by Powder Coating. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 52, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Kenel, C.; Dunand, D. C. Microstructure and Properties of Additively-Manufactured WC-Co Microlattices and WC-Cu Composites. Acta Mater. 2021, 221, 117420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Chen, C.; Yang, W. Additive Manufacturing of WC-20Co Components by 3D Gel-Printing. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2018, 70, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Shao, H.; Lin, T.; Zheng, H. 3D Gel-Printing—An Additive Manufacturing Method for Producing Complex Shape Parts. Mater. Des. 2016, 101, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierings, A. B.; Voegtlin, M.; Bauer, T.; Wegener, K. Powder Flowability Characterisation Methodology for Powder-Bed-Based Metal Additive Manufacturing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramian, A.; Razavi, S. M. J.; Sadeghian, Z.; Berto, F. A Review of Additive Manufacturing of Cermets. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enneti, R. K.; Prough, K. C.; Wolfe, T. A.; Klein, A.; Studley, N.; Trasorras, J. L. Sintering of WC-12%Co Processed by Binder Jet 3D Printing (BJ3DP) Technology. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2018, 71, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enneti, R. K.; Prough, K. C. Wear Properties of Sintered WC-12%Co Processed via Binder Jet 3D Printing (BJ3DP). Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 78, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.; Kwon, P.; Shin, C. S. Process Development Toward Full-Density Stainless Steel Parts with Binder Jetting Printing. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2017, 121, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. C.; Shon, I.-J.; Yoon, J.-K.; Doh, J.-M.; Munir, Z.A. Rapid sintering of ultrafine WC-Ni cermets. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2006, 24, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, C.; Gonzalez-Gutierrez, J.; Burkhardt, C.; Weber, O.; Holzer, C. The Production of Magnets by FFF-Fused Filament Fabrication. In Proceedings of the Euro PM2017 Congress & Exhibition, Milan, Italy, 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gutierrez, J.; Cano, S.; Schuschnigg, S.; Kukla, C.; Sapkota, J.; Holzer, C. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic and Ceramic Components by the Material Extrusion of Highly-Filled Polymers: A Review and Future Perspectives. Materials 2018, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.; et al. Additive Manufacturing of WC-Co Hardmetals: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 1653–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Lu, J. L.; Li, Q. G.; Cao, Y. N.; Lin, X.; Wang, L. L.; Huang, W. D.; El Mansori, M. A New Way to Net-Shaped Synthesis Tungsten Steel by Selective Laser Melting and Hot Isostatic Pressing. Vacuum 2020, 179, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudger, S. J.; Luckenbaugh, T. L.; Hornbuckle, B. C.; Darling, K. A. Mechanical Properties of Cemented Tungsten Carbide with Nanocrystalline FeNiZr Binder. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2024, 118, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, Z.; Umer, M. A.; Nisar, F.; Hafeez, M. A.; Yaqoob, K.; Luo, X.; Ahmad, I. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Hot Isostatic Pressed Tungsten Heavy Alloy with FeNiCoCrMn High Entropy Alloy Binder. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 2897–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B. T.; Zuhailawati, H.; Ahmad, Z. A.; Ishihara, K. N. Grain Growth, Phase Evolution and Properties of NbC Carbide-Doped WC-10AISI304 Hardmetals Produced by Pseudo Hot Isostatic Pressing. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 552, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, L. C.; Preston, A. D.; Ma, K.; Nandwana, P. In-Situ Metal Binder-Phase Formation to Make WC-FeNi Cermets with Spark Plasma Sintering from WC, Fe, Ni, and Carbon Powders. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2020, 88, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, Z. A.; Anselmi-Tamburini, U.; Ohyanagi, M. The Effect of Electric Field and Pressure on the Synthesis and Consolidation of Materials: A Review of the Spark Plasma Sintering Method. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokita, M. Progress of Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) Method, Systems, Ceramics Applications and Industrialization. Ceramics 2021, 4, 160–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantsev, E. A.; Malekhonova, N. V.; Chuvildeev, V. N.; et al. Investigation of High-Speed Sintering of Fine-Grained Hard Composites Based on Tungsten Carbide with an Ultra-Low Cobalt Content: II. Hard Composites WC-(0.3-1) wt.% Co. Inorg. Mater.: Appl. Res. 2023, 14, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C., Song, X., Fu, J. Y., Liu, X., Gao, Y., Wang, H., & Zhao, S. Microstructure and properties of ultrafine cemented carbides—Differences in spark plasma sintering and sinter-HIP. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2012, 552, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J. M. B.; et al. Study of Characteristics and Properties of Spark Plasma Sintered WC with the Use of Alternative Fe-Ni-Nb Binder as Co Replacement. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2020, 92, 105316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, E.; Correa, J. N.; Santos, A. N.; Klein, N. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of WC Ni-Si Based Cemented Carbides Developed by Powder Metallurgy. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2010, 28, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhakhmetov, Y.; Skakov, M.; Wieleba, W.; Sherzod, K.; Mukhamedova, N. Evolution of Intermetallic Compounds in Ti-Al-Nb System by the Action of Mechanoactivation and Spark Plasma Sintering. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2020, 7(2), 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhakhmetov, Y.; Skakov, M.; Mukhamedova, N.; Kurbanbekov, S.; Ramankulov, S.; Wieleba, W. Changes in the Microstructural State of Ti-Al-Nb-Based Alloys Depending on the Temperature Cycle During Spark Plasma Sintering. Mater. Test. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ren, X.; Liu, M. D.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Guo, S.; Chen, H. Effect of Cu on the Microstructures and Properties of WC-6Co Cemented Carbides Fabricated by SPS. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2017, 62, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilemany, J. M.; Sanchiz, I.; Mellor, B. G.; Llorca, N.; Miguel, J. R. Mechanical-Property Relationships of Co/WC and Co-Ni-Fe/WC Hard Metal Composites. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 1993, 12, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. H.; Chang, M. H.; Huang, K. T. Study on the Sintered Characteristics and Properties of Nanostructured WC-15 wt% (Fe-Ni-Co) and WC-15 wt% Co Hard Metal Composites. J. Composites Compd. 2015, 649, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powder Metallurgy World Congress, Kyoto, Japan, 12-16 November 2001; Part-I, pp 252-255.

- Matsugi, K.; Hatayama, T.; Yanagisawa, O. Effect of Direct Current Pulse Discharge on Specific Resistivity of Copper and Iron Powder Compacts. J. Jpn. Inst. Met. 1995, 59, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manière, C.; Lee, G.; Olevsky, E. A. All-Materials-Inclusive Flash Spark Plasma Sintering. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhadilov, B.; Kantay, N.; Sagdoldina, Z.; Paszkowski, M.; et al. Experimental Investigations of Al₂O₃- and ZrO₂-Based Coatings Deposited by Detonation Spraying. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8(5), 056402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Johnsson, M.; Zhao, Z.; Nygren, M. Spark Plasma Sintering of Alumina. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002, 85, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Holland, T.; Unuvar, C.; Munir, Z. A. Spark Plasma Sintering of Nanometric Tungsten Carbide. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2009, 27, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Niewa, R.; Schmidt, M.; Grin, Y. Spark Plasma Sintering Effect on the Decomposition of MgH2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2005, 88, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Nishio, T.; Matsumoto, A.; Sugiyama, A. Sintering Phenomena on Initial Stage in Pulsed Current Sintering. J. Jpn. Soc. Powder Powder Metall. 2000, 47, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; et al. Study on Preparation of WC-6Co-1.5Al Cemented Carbide by SPS Sintering. Powder Metall. Technol. 2006, 24, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, M. Sintering, Consolidation, Reaction and Crystal Growth by the Spark Plasma System (SPS). Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2000, 287, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alymov, M. I.; Borovinskaya, I. P. Prospects for the Creation of Hard Composites Based on Submicron and Nanoscale Powders W and WC, Obtained by the Chemical-Metallurgical Method and Using SHS. Inorg. Mater. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. Neck Formation and Self-Adjusting Mechanism of Neck Growth of Conducting Powders in Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Sakka, Y.; Maizza, G. Effects of Initial Punch-Die Clearance in Spark Plasma Sintering Process. Mater. Trans. 2008, 49(12), 2899–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaim, R. Corrigendum to "Densification Mechanisms in Spark Plasma Sintering of Nanocrystalline Ceramics" [Mater. Sci. Eng., A 443 (2007) 25-32]. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2008, 486, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, T.; Shikatani, N.; Kawakami, Y.; Enjoji, T.; Ohtsu, Y. Influence of Internal Pulsed Current on the Sintering Behavior of Pulsed Current Sintering Process. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 638, 2109–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.; Nie, L.; Wellmann, D.; Tian, Y. Additive manufacturing of WC-Co hardmetals: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 1653–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. C. Study of Sintering Kinetics in Solid State of WC-Co and WC-Fe-Ni-Co Carbide Composites Via Pulsed Plasma. DSc Thesis, Darcy Ribeiro State University of Northern Rio de Janeiro, UENF, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. H.; Liu, Z. F.; Lu, J. F.; et al. The Sintering Mechanism in Spark Plasma Sintering—Proof of the Occurrence of Spark Discharge. Scr. Mater. 2014, 81, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E. N.; et al. Investigation of Characteristics and Properties of Spark Plasma Sintered Ultrafine WC-6.4Fe3.6Ni Composite as Potential Alternative WC-Co Hard Metals. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2021, 101, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shichalin, O. O.; Buravlev, I. Y.; Portnyagin, A.; et al. SPS Hard Metal Composite WC-8Ni-8Fe Fabrication Based on Mechanochemical Synthetic Tungsten Carbide Powder. J. Composites Compd. 2020, 816, 152547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, D. M.; Anders, A.; Dudina, D. V.; et al. The Absence of Plasma in "Spark Plasma Sintering". J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 033305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. C.; Skury, A. L. D.; Silva, A. G. P. Spark Plasma Sintering of a Hard Metal Powder Obtained from Hard Metal Scrap. Mater. Res. 2017, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product Code Name | Co Content wt% |

WC pdr. Grain Size μm |

Density g/cm3 |

Hardness mHv |

Transverse Rupture Strength MPa |

Fracture Toughness K1C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC-05 | <2 | <0.5 | 15.2 | 2350 | 2300 | 6.2 |

| TC-10 | <4 | <0.5 | 15.0 | 2150 | 2640 | 6.5 |

| TC-20 | <6 | <0.5 | 14.8 | 2050 | 2940 | 7.3 |

| M78 | 0 | <0.2 | 15.4 | 2600 | 1500 | 5.1 |

| WC100 | 0 | <0.08 | 15.6 | 2700 | 1470 | 5.6 |

| NC100 | 0 | <0.5 | 15.4 | 2570 | 1180 | 5.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).