1. Introduction

The renders of historical buildings in coastal areas have been subjected, all over the years, to an aggressive environment of salty mist, high relative humidity, hot sun, dry wind and sometimes, even to waves’ strength. Notwithstanding the severity of the sea environment, ancient lime mortars used for joints and renders of this kind of constructions prove to be very resistant and durable and show essentially superficial degradation, such as biological colonisation, dirty stains and heterogeneous surfaces [

1]. Although most of these defects could be easily repaired, some of these buildings have suffered over the last decades intrusive repair interventions, often with incompatible solutions, producing severe damage, such as detachments, erosion, loss of cohesion and presence of salts efflorescences and cryptoflorescences.

An accurate choice of the repair mortar is fundamental for successful restoration works: It is expected that the new repair mortar provides resistance to the existing environmental conditions and protects the original substrate, as well as being as durable as possible [

2,

3]. The new mortars need to be mechanically resistant but should not transmit high stresses to the substrate and restrain its movements; besides, they should not have high contents of soluble salts, to avoid the increase of salt contamination into the walls, as well as need to have the ability to protect the wall against rain, avoiding quick penetration in high quantity; they are also required to facilitate the evaporation of water as much as possible, in liquid and vapour form, both infiltrated and originated by capillary rising [

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, the mortars performance does not depend only on the raw materials and on application, but it is also related to the characteristics of the substrate [

6] and to the environmental exposition [

7,

8,

9], which can create some technical challenges in the mortars formulation for the conservation of these buildings.

The case study of Paimogo Fort, a military structure built in 1674 in the municipality of Lourinhã, approximately 76 km north of Lisbon, reflects some of these difficulties. Abandoned during the first half of the 19th century, suffered severe damage due to the lack of maintenance in the aggressive maritime environment to which it is exposed. The latest renovation work, carried out on the building in 2006, which involved replacement of the original rendering and plastering mortars for new ones, demonstrated the difficulty of this task since, only fifteen years later, the repair mortars showed significant signs of deterioration (e.g., loss of cohesion, cracking, erosion) [

10].

In this case study, due to the diversity of raw materials used in its construction and to the aggressive environmental conditions to which the Fort is subjected, it is required that the new mortars present good performance and durability to those conditions, besides being chemical, mineralogical and physical-mechanically compatible with the original materials. Nevertheless, previously developed studies demonstrate that performance obtained in laboratory is not always representative of in situ behaviour, particularly in the long term [

11]. In this sense, within the scope of the “Coastal Memory Fort” Project, financed by the EEA Grants - Culture Program 2014-2021, promoted by Lourinhã Municipality, the National Laboratory for Civil Engineering (LNEC) was responsible for characterizing the existing renders [

10,

14] and formulating repair mortars to be applied to this monument.

Several lime-based mortars with compositions close to the original ones were considered as possible repair mortars. Given that the hygro-mechanical properties of mortars change with type of substrate (due to different physical properties), in the present investigation, were applied on substrates with different porosity and the resulting physical-mechanical performances were characterized. Moreover, some of those compositions were exposed in the Fort area, to better understand the impact of real exposure conditions on the performance of these mortars. Their behaviour and the possible degradation mechanisms were investigated, considering the substrate characteristics. Finally, all the results were considered and discussed to choose the most compatible and durable repair mortar compositions, to be chosen for the rehabilitation of the Fort.

2. Case Study and Research Aims

Built on the cliffs of Paimogo beach (Lourinhã), in the XVII century, the Nossa Senhora dos Anjos de Paimogo Fort, better known as Paimogo

Fort, is a coastal military structure, classified of public interest since 1957, which was part of the defensive system of Lisbon region [

12].

For the original masonry walls, stones from local quarries, with low values of absorption, and air lime baked in the artisanal ovens of the region, were used [

13], as well as porous clay bricks on the interior vaults.

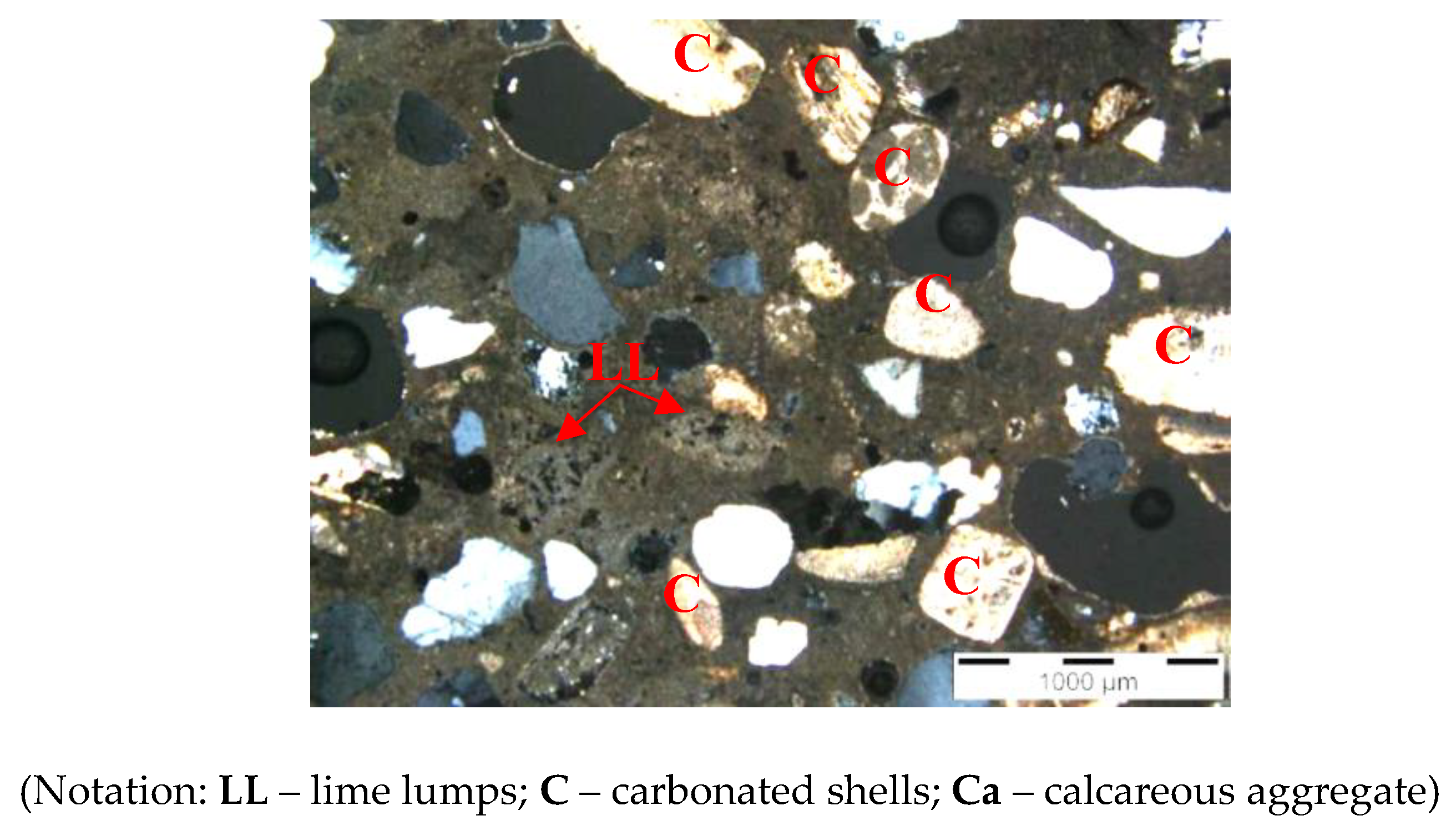

According to the LNEC Report [

10], the original mortars analysed in laboratory were composed of calcitic air lime and siliceous and limestone sand of coastal origin with crustacean shells (

Figure 1).

The investigations carried out by Veiga et al. [

10] also showed that the original mortars, rich in lime, had good mechanical properties and deformability and a moderate capacity for water absorption by capillary action (

Table 1). However, most of the original air lime renders and plasters have been removed in an intervention of 2006 and replaced by new ones, based on hydraulic lime, which showed degradation, especially erosion and loss of cohesion (

Figure 2).

Thus, after an extensive characterization of the original mortars, new mortars formulations, with compositions close to the original ones, were proposed and tested by LNEC, to select the new repair mortar composition [

14]. The investigation described in this paper, included both laboratory and in situ tests using different types of brick substrates, whose main results aimed to assess the suitability of several repair mortar formulations by characterising their physical, mechanical and hydric properties when applied on substrates with different absorption characteristics.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Mortars Materials and Mixes

Concerning the knowledge of the old materials [

10] and the previously determined chemical, physical and mechanical compatibility with the background and the pre-existent materials [

14] a set of mortars compositions with different characteristics, were selected (

Table 2). The requirements were: similar composition to the original ones and simultaneously physical-mechanical characteristics as close as possible to the old mortars.

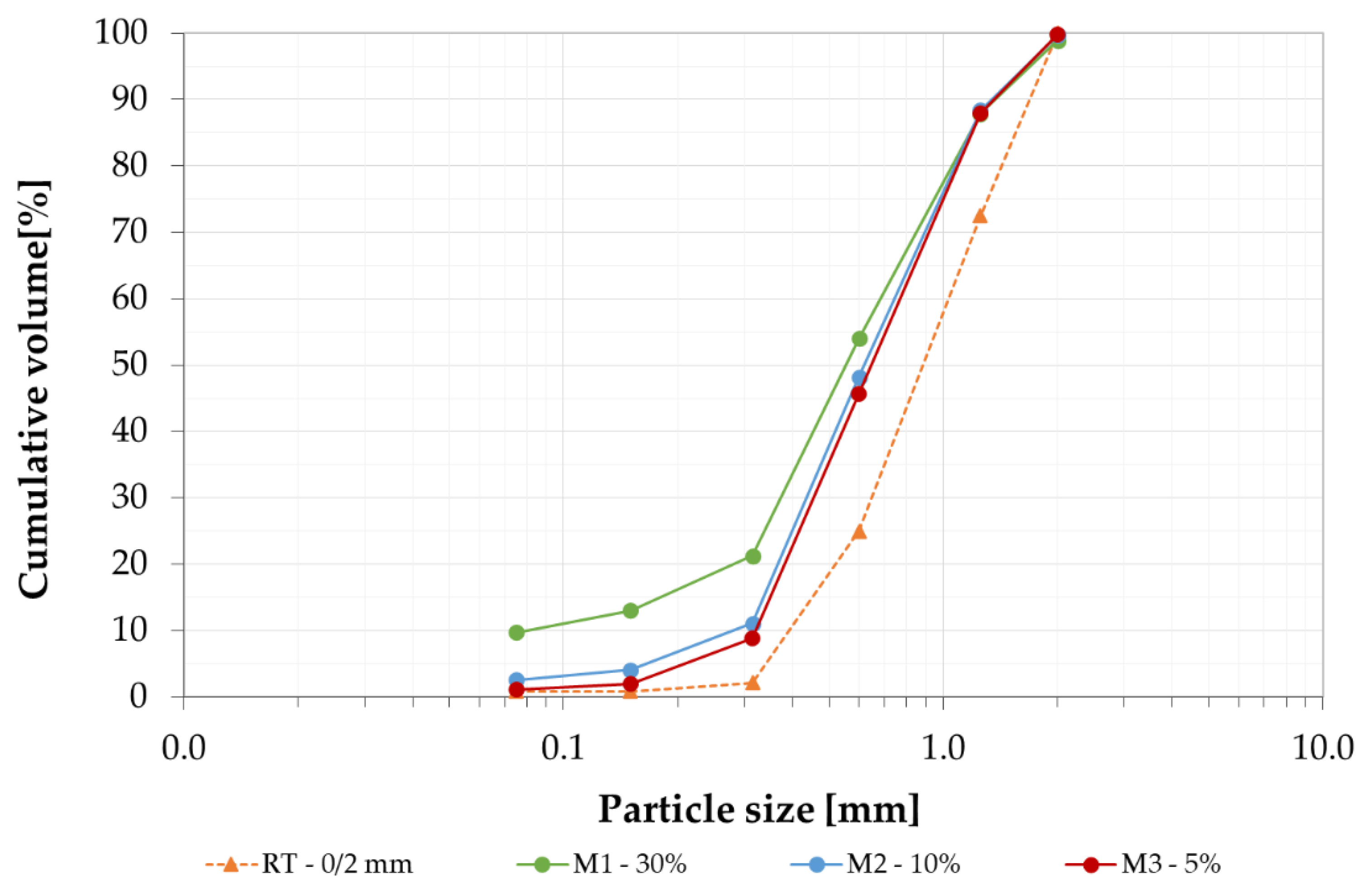

An air lime mortar (A), composed by calcitic air lime (CL90-S, according to EN 459-1 [

15]) and natural siliceous sand (d = 0/2mm) from Tagus River, was used as base mortar, , due to being the simplest mortar with similar composition to the original ones, thus with high compatibility with the ancient masonry [

16] (

Table 2 and

Figure 3).

Further, to respect the authenticity principles, trying to get closer to the composition of the old mortars, and also to their mechanical properties, which were higher than the chosen base mortar, quicklime (CL90-Q - R5, P2, according to the EN 459-1[

15]) was added to the hydrated air lime mortar (A) composition [

17,

18,

19], by substitution of 30 % of slaked air lime by volume, just before use.

Moreover, since the repair mortars will be applied in severe marine environment, where additional strength is needed and some hydraulicity may be favourable, slightly hydraulic mortars were used, obtained through: the use of mixes of air lime with 25% of white Portland-cement (CEM II/B-L 32.5R, according to EN 197-1[

20]). This relatively low content of cement was chosen in order to keep the porosity and moisture transport properties similar to the old mortar [

9]. Additionally, a natural hydraulic lime (NHL5, according to the EN 459-1[

15]) was also assessed.

Additionally, to approach to the original mortar compositions and improve the mortars’ performance [

21], a fine-tuning of the aggregates was made, substituting part of the siliceous sand by fine limestone sand (d = 0/1mm) in 30% (M

1), 10% (M

2) and 5% (M

3), by volume. All the mortars compositions are described in

Table 2 and

Figure 3.

The mortars were prepared according to the protocol defined in EN 1015-2 [

22], except for mixes incorporating quicklime, for which the method had to be adapted due to their very short hardening time, significantly reducing their workability. The main objective to add quicklime to the slaked lime, just before application, was to provide the volume stability of the lime mortars thus reducing cracking, enhance mechanical strength and, consequently, durability of the lime mortars [

18,

19,

20]; however, due to its high temperature and quick setting, it was necessary to adapt the mixing procedure to be able to apply these mortars. The stages involved in the adapted mixing process were: firstly, the dry solid constituents of the mortar (slaked air lime + quicklime + sand), were mixed. Secondly, 90% of the predetermined amount of water (

Table 2) were added to the dry solid mix into the mortar mixer and all the constituents were mixed, for a period of 5 minutes, with the mixer running at low speed; followed by a rest period of 10 minutes

1. Thirdly, the mortars were mixed for more 5 minutes at low speed, adding the remaining of the mix water (10%), to confer good plasticity and workability.

3.2. Substrates Characterization

To evaluate the performance of the mortars when applied on porous substrates, all mortars compositions (

Table 2) were prepared and applied, in a single layer with a thickness of 20 ± 2 mm, on common ceramic bricks (30 cm x 20 cm x 11 cm), with the main characteristics defined in

Table 3.

Even if the same initial composition is used, the final pore structure of the hardened mortar differs when applied on substrates with different physical properties, and consequently the mortar’s hygro-mechanical properties also vary, [

6]. Thus, in this investigation, the mortars were additionally applied on a more porous and absorbing substrate – traditional solid calcined bricks (23 cm x 11 cm x 7 cm) (

Table 3).

After the application, the mortar surface of each specimen was sprinkled with water every 24 hours, for three days. Then, the mortars were cured at 20 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5% RH, until the testing dates (28, 90 and 180 days).

3.3. Environmental Exposition

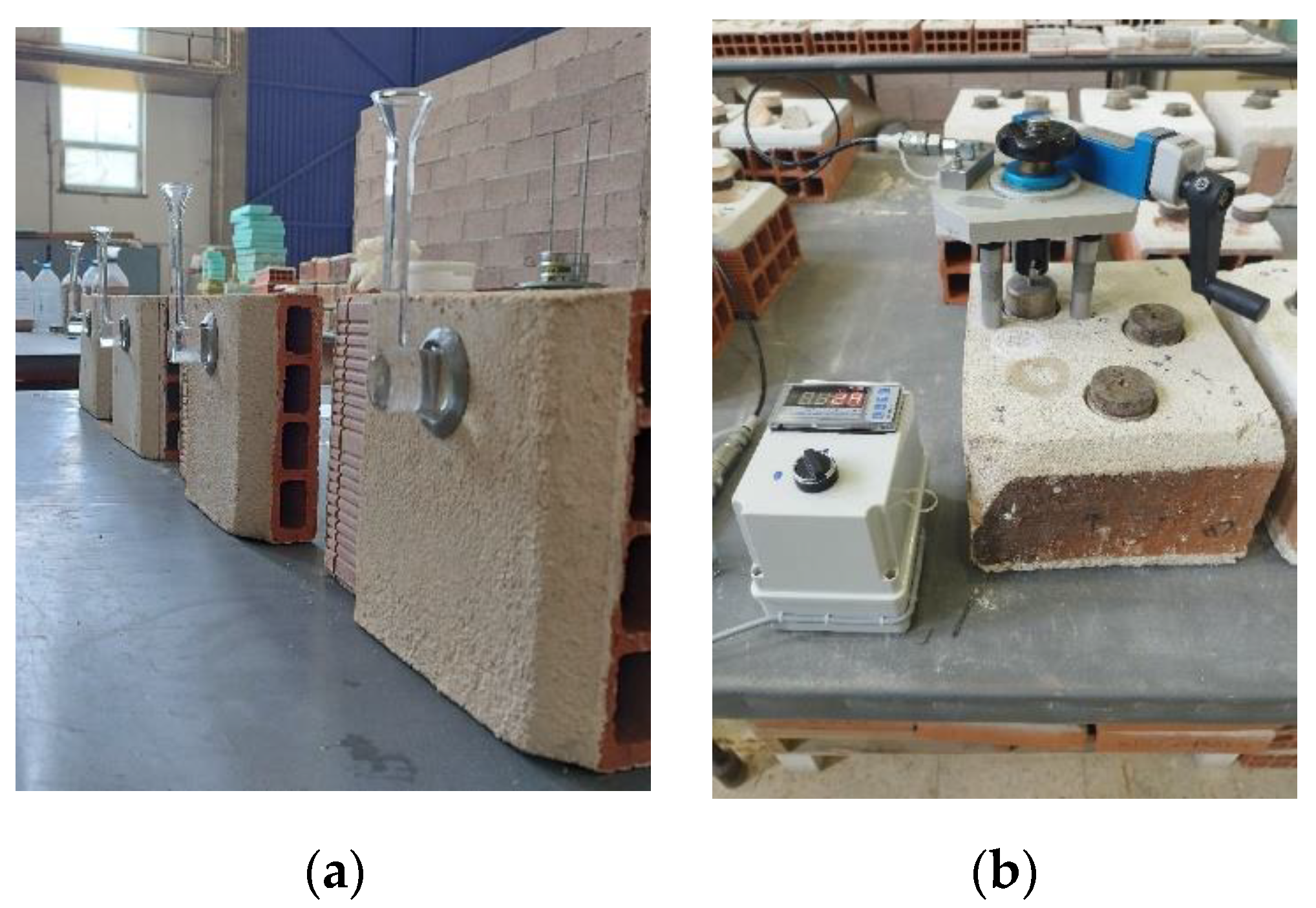

To assess the effect of the climatic and environmental conditions on mortars behaviour and durability, the reference mortars compositions were also applied on mini-wallettes, composed by three traditional porous bricks with large joints of lime-based mortars with long period of carbonation (

Figure 4) and subjected to the same laboratory cure conditions for 15 days, followed by exposure in the Fort’s maritime environment (

Figure 4) for approximately ten months (September to July).

During this exposition interval parameters like temperature, relative humidity and wind speed were registered [

26]: the average relative humidity was 75 % and was characterized by quick showers during most of the period of exposition. The average daily air temperature ranged between 12 and 20 °C, with a maximum diurnal temperature variation register of 12 °C. In general, the wind registered in the Fort was strong (average of 20 km/h), with some wind gusts of more than 50 km/h.

3.4. Methodology

In this research, the search for a suitable formulation for the restoration mortar of the Paimogo Fort was carried out by assessing the behaviour and durability of mortars applied to bricks and cured both in laboratory and in the Fort environment.

The research comprised four main tasks:

Table 4 summarizes the substrate types, and the exposition conditions used for each formulation of repair mortars.

The properties of the mortars were assessed in laboratory (Tasks 1, 2 and 4) using non-destructive tests (measurement of ultrasound propagation and surface hardness), at 28, 90 and 180 days, to monitor changes in their properties during the carbonation process. At 180 days, destructive tests (flexural and compressive strengths, porosity and adhesion to the substrate) as well as water permeability at low pressure test were also performed.

To assess the performance and durability under the fort’s environmental conditions (Task 3), the non-destructive tests mentioned above (measurement of ultrasound propagation and surface hardness) were also carried out regularly throughout the exposition period (september 2021 to july 2022). At the end of the exposure period, destructive tests (flexural and compressive strengths, porosity and adhesion to the substrate), as well as water permeability at low pressure tests, were also carried out under laboratory conditions.

Furthermore, visual observation of the specimens and presence of anomalies (cracks, discontinuities, loss of cohesion, etc) were photographically recorded during all the period of analysis.

3.5. Test Methods

The test methods used are described below:

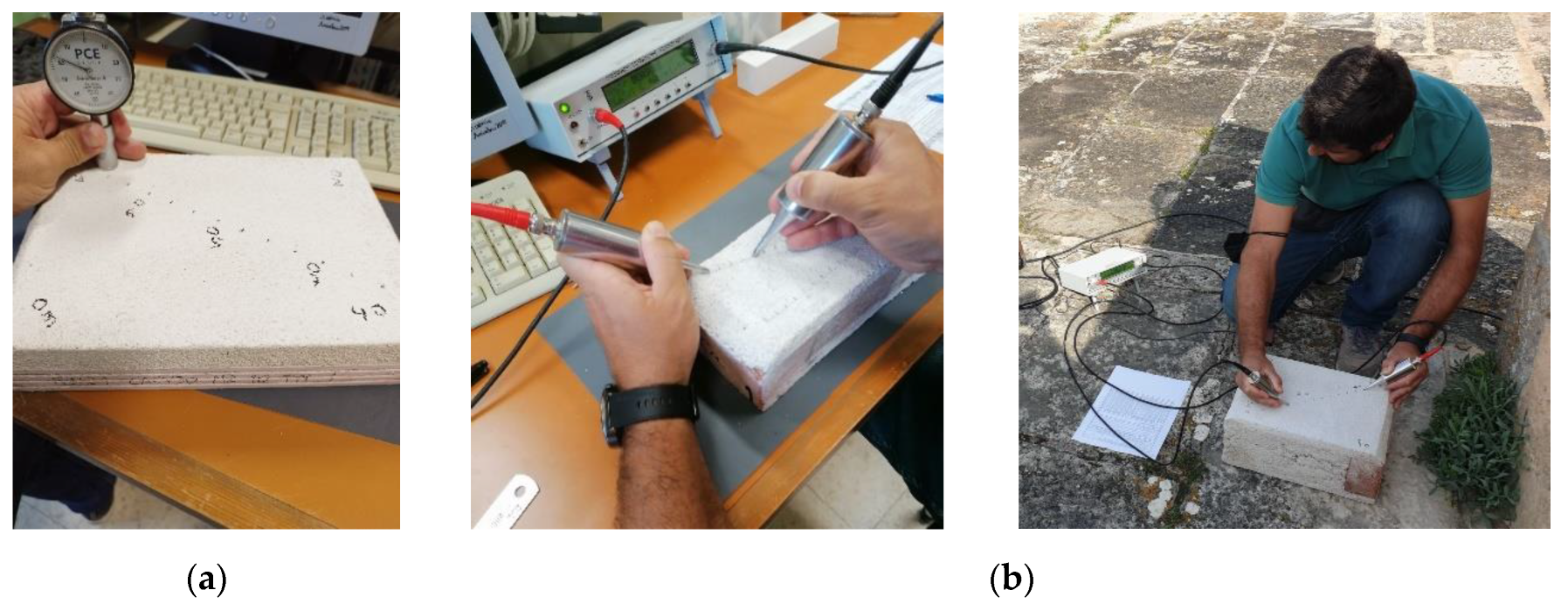

Shore Hardness (with a Shore A Durometer) is a non-destructive method to evaluate the surface hardness and indirectly the surface cohesion. In this test the Shore A durometer with a point is pressed against the mortar surface by the action of a spring with a standardized force, giving a measure of the surface hardness on a scale ranging from 0 to 100 (

Figure 5a). The greater the measure is, the greater are the surface hardness and the cohesion. The test is based on the ISO 7619 [

27] and ASTM D2240 [

28] standards. Five measurements were performed at different points of each specimen.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity test is also a non-destructive method for measuring dynamic properties of the mortars, as the elastic modulus. Ultrasonic velocity measurements are also useful for detecting levels of deterioration that could cause a decrease in the mechanical properties, even while no visible decay effects are found [

29]. This technique was carried out in accordance with standard NP EN 12504-4 [

30], which consists of measuring the speed of propagation of longitudinal ultrasonic waves (P-waves), through the mortar specimens, between a transmitter and a receiver placed at a known distance from each other. In this research, the indirect transmission method was used (transducers positioned on the same surface) with a distance of 20 mm between them and successively increasing the distance by displacing one of the transducers (

Figure 5b).

The dynamic modulus of elasticity (E) of the mortar can be estimated by Equation (1):

Where (-) is a coefficient depending of the Poisson’s coefficient material and it was taken to be equal to 0.9, assuming a Poisson coefficient of 0.2 for every mortar tested; (kg/m3) is the bulk density of the mortar previously determined in the laboratory and (m/s) is the velocity of the ultrasonic wave, determined as the slope of the linear regression of the distance as function of time obtained experimentally.

Water permeability at low pressure was tested in accordance with EN 16302 [

23], using Karsten tubes to evaluate the waterproof capacity of the mortar. The test technique consists of registering the volume of water absorbed by a surface during chosen time-spans, using pipe-shaped tubes which are fixed to the surface to study (

Figure 6a). In this work, for each tube, the water level was registered at the following time intervals: each minute until five minutes and then 10, 15, 20 25 and 30 minutes.

Pull off test to assess the adhesion between the mortar and the substrate. The test is based on EN 1015-12 [

31] standard and is performed by fixing with epoxy adhesive a metallic disc to the mortars surface in order to apply a tensile force normal to the surface to be tested. The force is then gradually applied to the disc and the failure occurs along the weakest plan within the system (

Figure 6b). The maximum stress was then calculated by dividing the tensile force value obtained by the area of the disc. Three measurements for each mortar composition were made in this investigation.

Figure 6.

Tests performed in laboratory on the mortars specimens at 180 days and at the end of the exposure period: (a) low pressure water permeability measurement; (b) Pull off test.

Figure 6.

Tests performed in laboratory on the mortars specimens at 180 days and at the end of the exposure period: (a) low pressure water permeability measurement; (b) Pull off test.

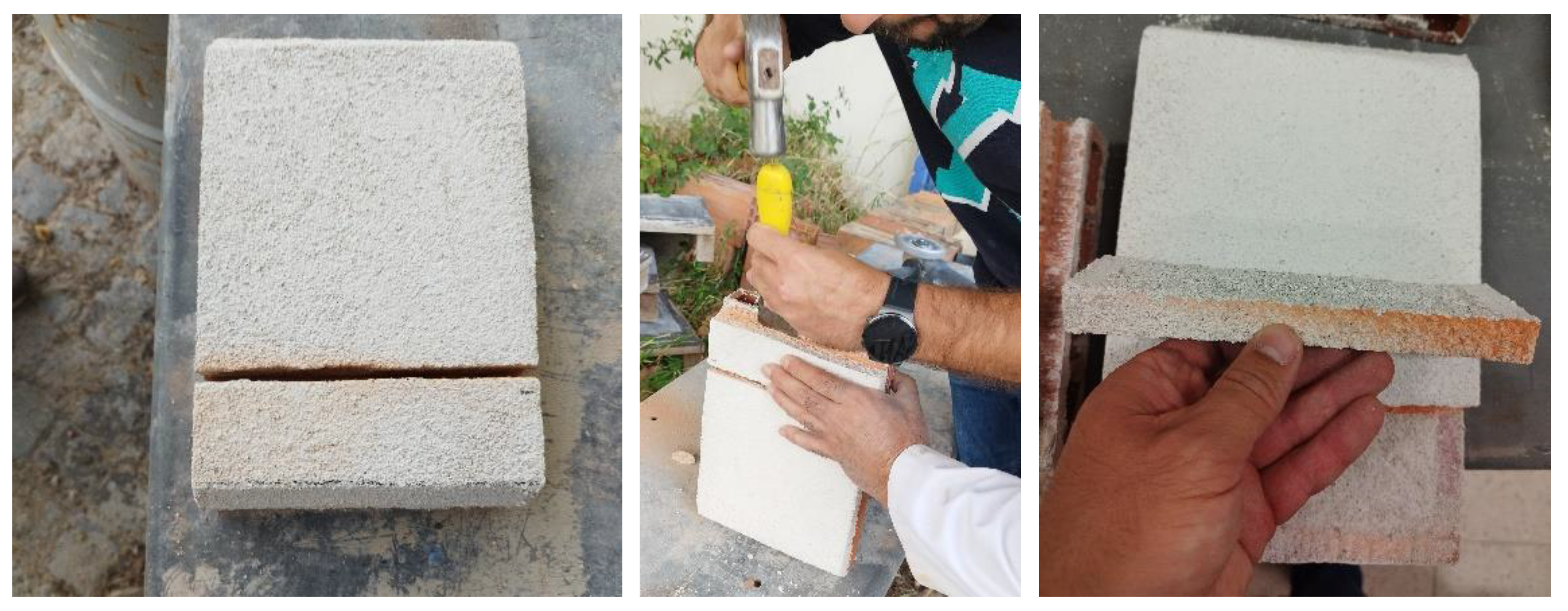

To characterize the mortars applied on the bricks (common ceramic, traditional porous bricks and mini-wallettes) in some destructive tests (flexural and compressive strengths as well as open porosity), it was necessary to adapt the specimens dimensions to the normalized tests dimensions. Thus, slices of the mortars with 50 ± 2 mm were cut and then detached from the substrate (

Figure 7).

Flexural and

compressive strength tests to quantify the mechanical properties of the mortars were adapted from the EN 1015-11 [

32] standard, using load cells of 2 kN and 200 kN, for the flexural and compressive strength respectively

. To perform these tests at least two slices per mortar composition were used (

Figure 8a), resulting two measurements for the flexural strength and, after the rupture, four specimens were obtained to use in the compressive strength test. Due to the traditional bricks smaller dimensions the flexural strength test was only possible in the common ceramic brick’s specimens

.

Open porosity and

apparent density of the mortars to assess their compacity and estimate their water absorption capacity. This assessment is of great importance for the durability of the mortars and was determined based on EN 1936 [

25], by immersion and hydrostatic weighing, using a low pressure of 40 kPa, as the pores of lime-based mortars are relatively large (

Figure 8b). The test was caried out in 3 fragments of the specimens prepared for the flexural and compressive strength tests for each mortar composition.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Influence of the Mortar Binder – Task 1

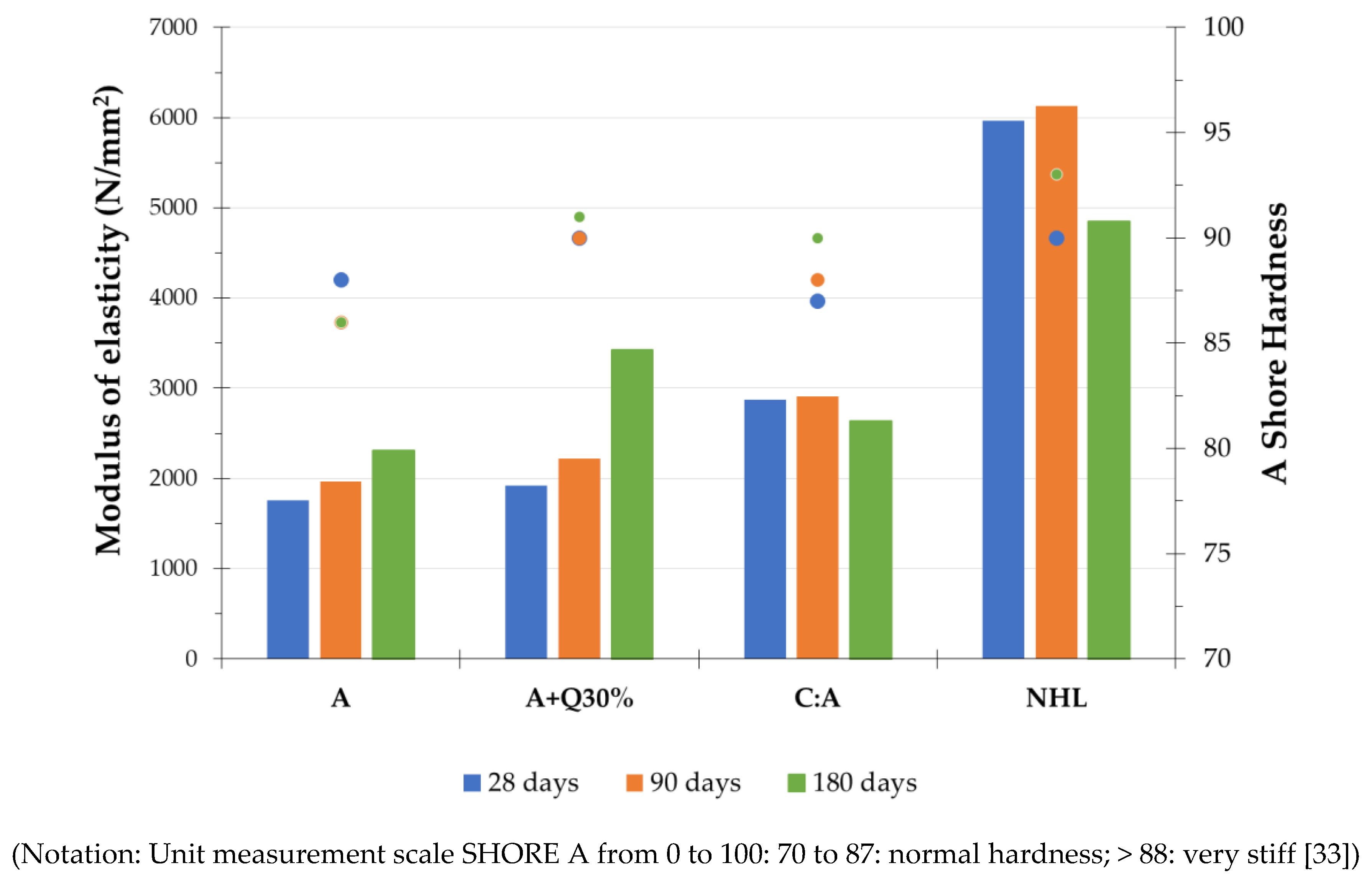

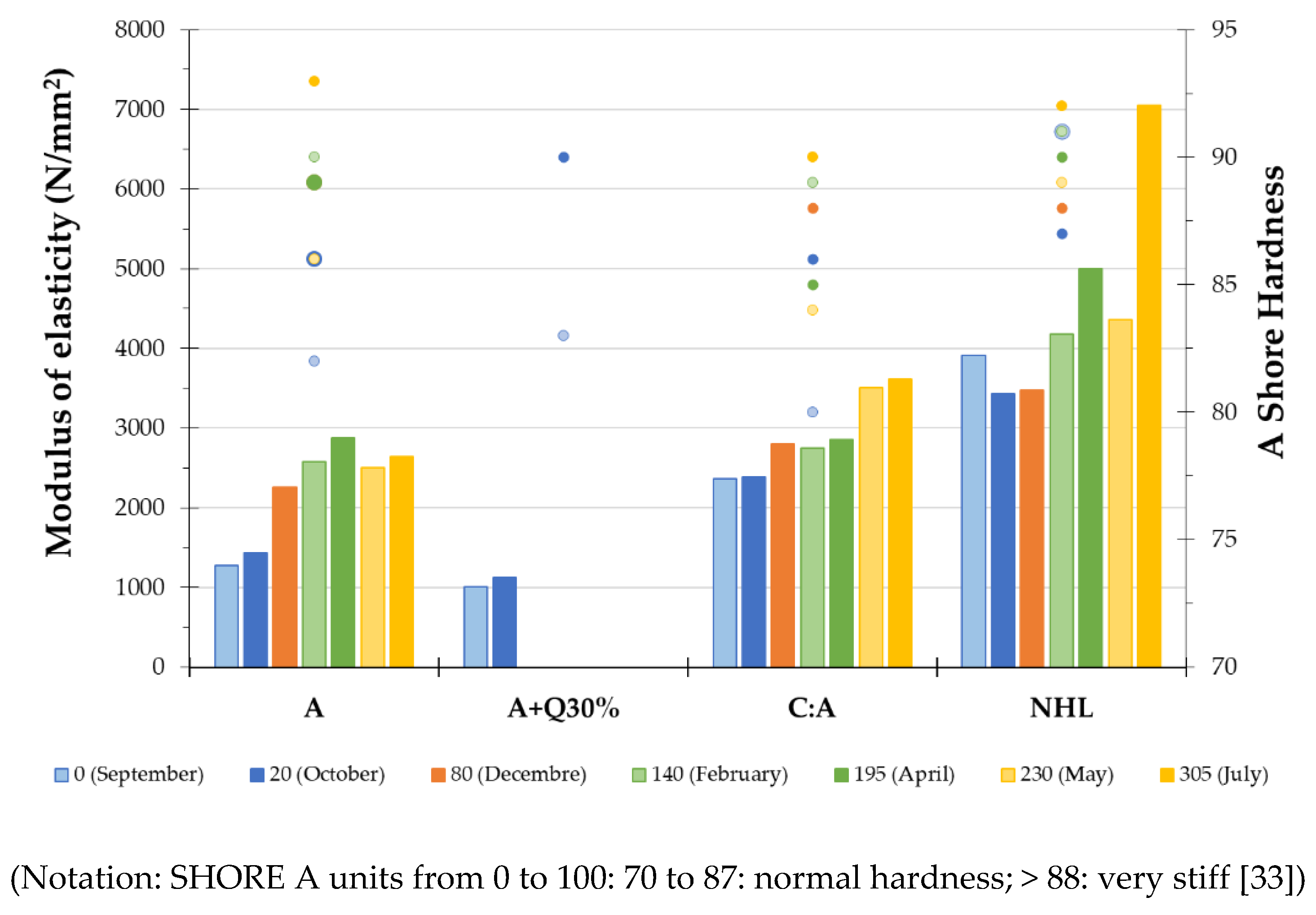

The influence of the binder on the characteristics of the mortars applied on common ceramic bricks with moderate to low water absorption (

Table 3) was analysed at the age of 28, 90 and 180 days for non-destructive tests (measurement of ultrasound propagation and surface hardness) (

Figure 9) and at 180 days for the destructive tests (flexural and compressive strengths, porosity and adhesion to the substrate), as well as for water permeability at low pressure test (

Table 5).

Regarding the global results obtained along the carbonation process (

Figure 9) it was found that air lime mortars, A and A+Q30%, present moderate deformability (modulus of elasticity between 1760 and 3430 N/mm

2) and high surface hardness (86 to 91 Shore A). Additionally, these mortars show a tendency to improve their performance with the curing time.

However, mortars with some hydraulicity (C:A and NHL), despite their good performance at early ages, show a drop on their behaviour at 180 days (

Figure 9). Natural hydraulic lime mortar (NHL) presents the highest values (modulus of elasticity between 4850 and 6130 N/mm

2 and superficial hardness between 90 and 93 Shore A scale).

The physical and mechanical tests results obtained at 180 days, for the reference mortars samples removed from the common ceramic bricks (

Table 5), show similar trends to non-destructive tests results, at the age of 28, 90 and 180 days (measurement of ultrasound propagation and surface hardness) obtained on the same applied mortars (

Figure 9).

The natural hydraulic mortar (NHL) is found to be the most compact mortar, with the highest bulk density and lowest open porosity values and as a consequence, this mortar showed the lowest water absorption and as a whole the highest mechanical strengths by comparison with the other compositions. This mortar composition also presents a relative high adhesion to the substrate, with cohesive failure in the render. However, notwithstanding its good general characteristics, the relatively high modulus of elasticity can cause internal stresses on the mortar matrix, that, considering the low flexural strength values of the mortar, may produce microcracking, causing a loss of mechanical characteristics and durability at long term.

The air lime mortars (A and A+Q) present very similar porosities, densities and water absorption, however they clearly differentiate on the mechanical strengths (

Table 5). The addition of quicklime to the slaked air lime enhances the strengths of the air lime mortar, with a significant increase in the compressive strength, although a slight decrease in adhesion to the medium porous substrate (common bricks) was detected (

Table 5). In fact, the expansion of quicklime on slaking fills voids improving microstructure and lowering shrinkage [

19], which contribute to a compact structure and, consequently, improve the mortar mechanical strength. Furthermore, high concentration of quicklime absorbs the excess water from mixing during the slaking process, which reduces the shrinkage of the lime matrix [

20]. However, the heat generated during the slaking and the free water absorption by the masonry unit used as substrate could reduce the moisture transfer from the mortar into the pore system of the substrate and, consequently, potentiate the failure on the mortar interface [

18,

34].

The addition of white cement to the slaked lime mortar (C:A), besides increasing the values of the modulus of elasticity and of the compressive strength, when compared to the pure slaked lime mortar (A), leads to a slight decrease of the adhesion to the substrate and to low values of flexural strength, since the specimens broke before the beginning of the tests (

Figure 10). This behaviour could be attributed to some microcracking of the mortars’ matrix, since this anomaly affects flexural strength to a higher degree than compressive strength [

35].

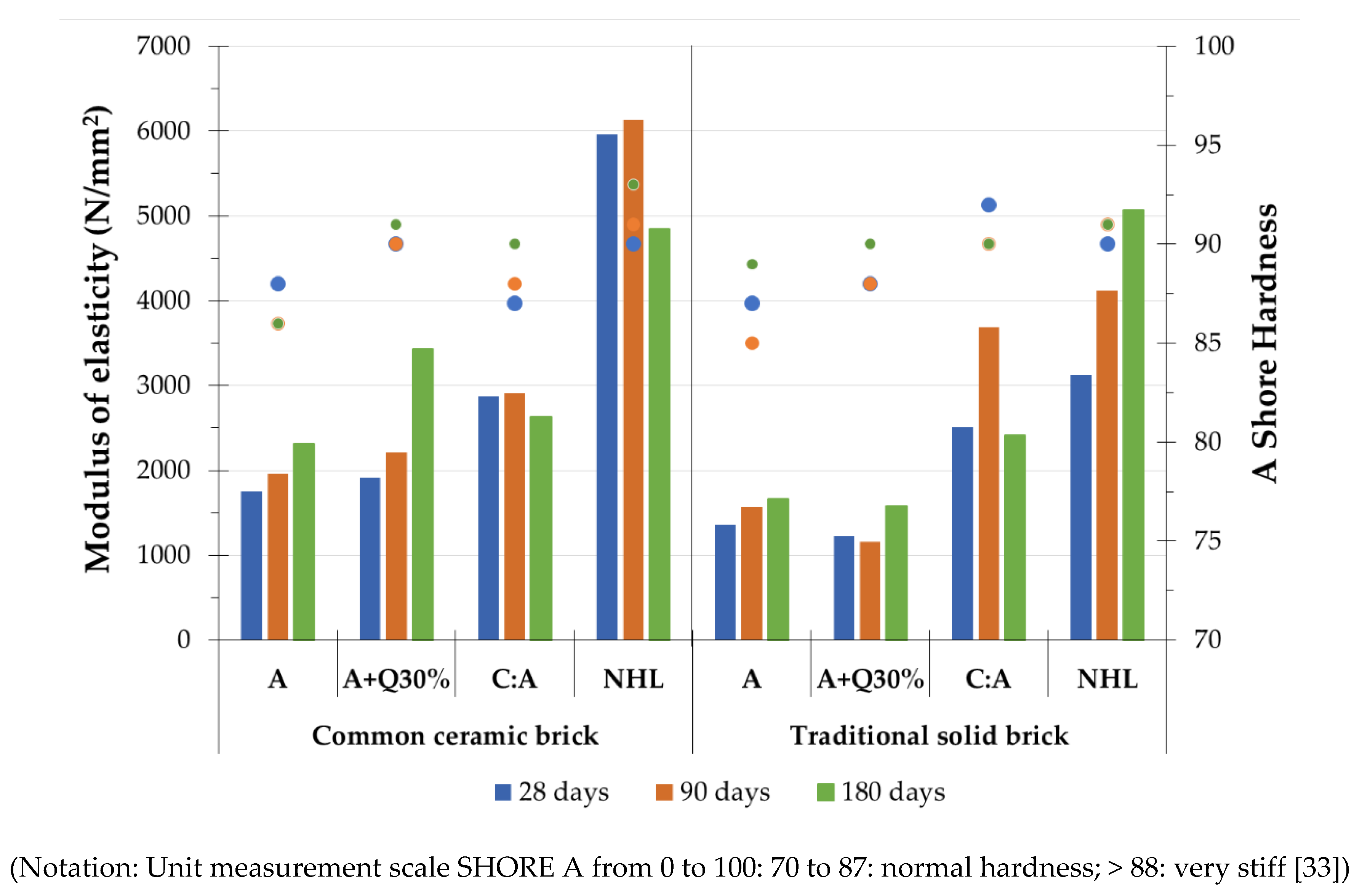

4.2. The Influence of the Substrate Characteristics – Task 2

With the aim to analyse the influence of the substrate characteristics on the mortars performance, the reference mortars compositions studied in task 1, were also applied on very porous and absorbent traditional bricks (

Table 3) and the behaviour of the new applications were compared under the same laboratory conditions.

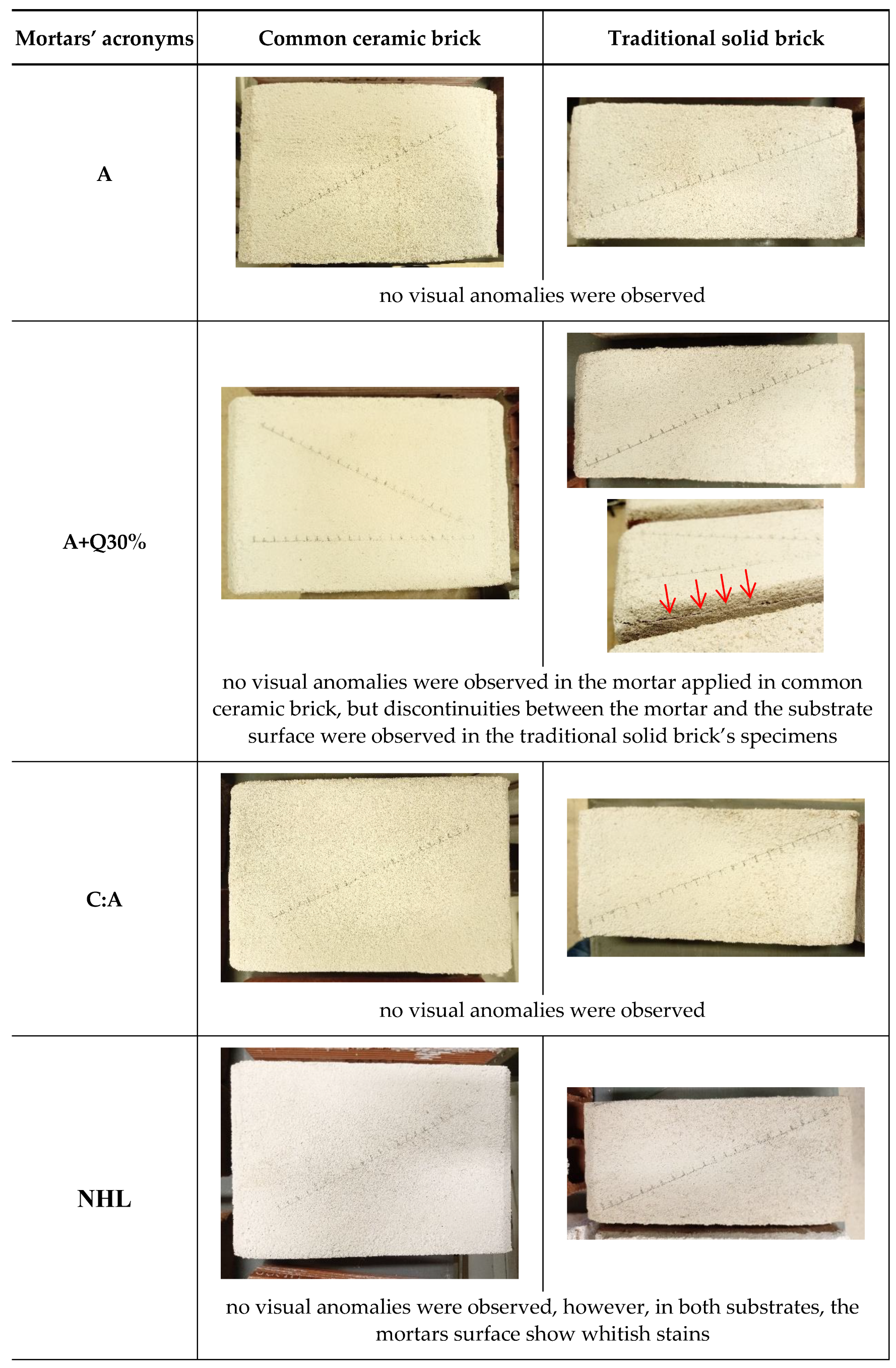

The analyses carried out at 28, 90 and 180 days using ultrasound pulse propagation and surface hardness show that, in general, for all mortars compositions, there is a drop in their modulus of elasticity when a more absorbent and porous substrate is used by comparison with the application on the medium absorbent one (

Figure 11). This drop may indicate some microcracking, if the other mechanical characteristics are not similarly affected.

The A+Q30% was the mortar composition which behaviour was the most affected by the properties of the substrate. In fact, the mix water available for the slaking and carbonation processes of the air lime could be quickly absorbed and at large scale by the porous substrate, which could accelerate the drying during the carbonation process, generating high stress at the interface and, as a consequence, microcracking could occur, affecting the mechanical behaviour of the mortar.

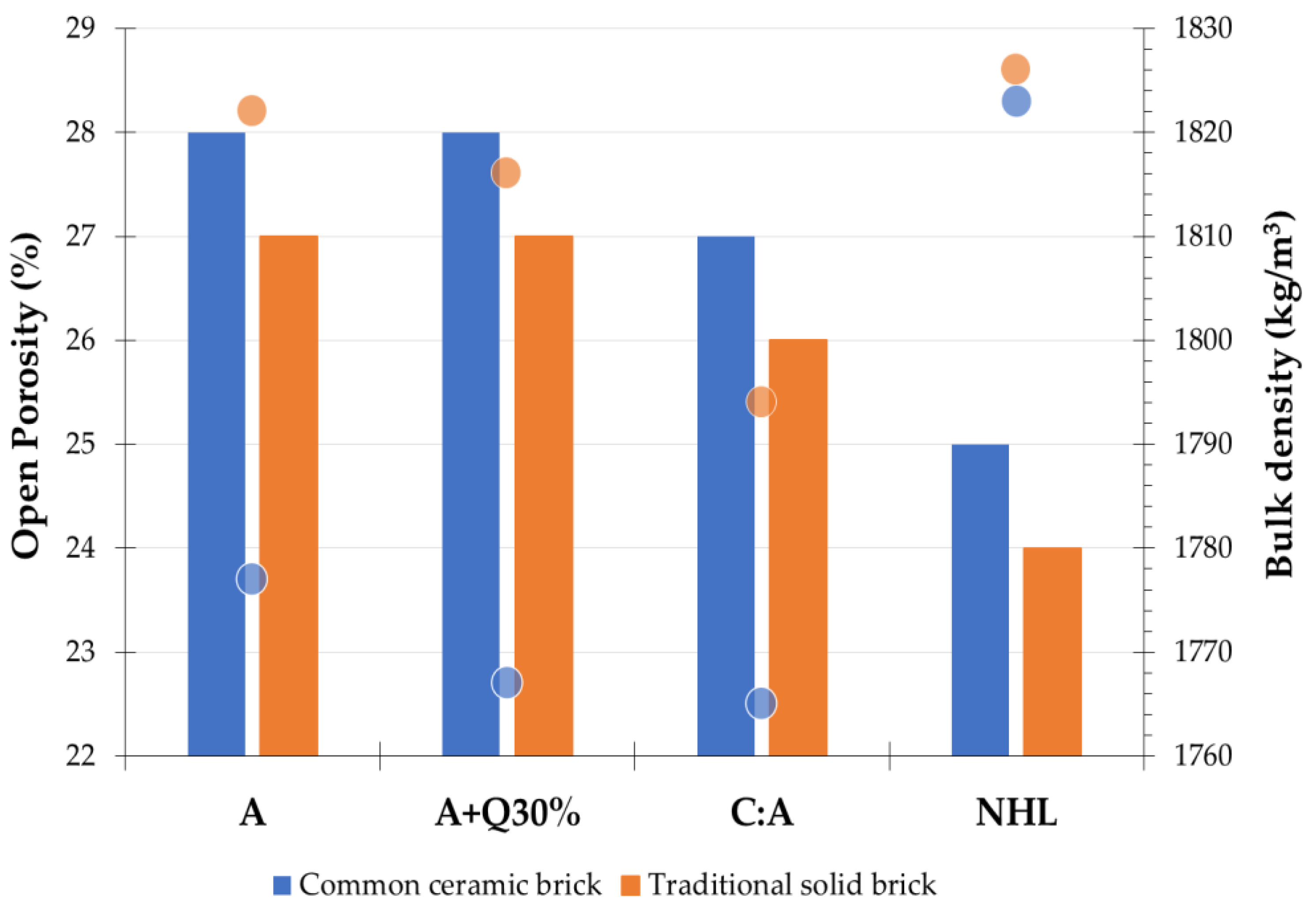

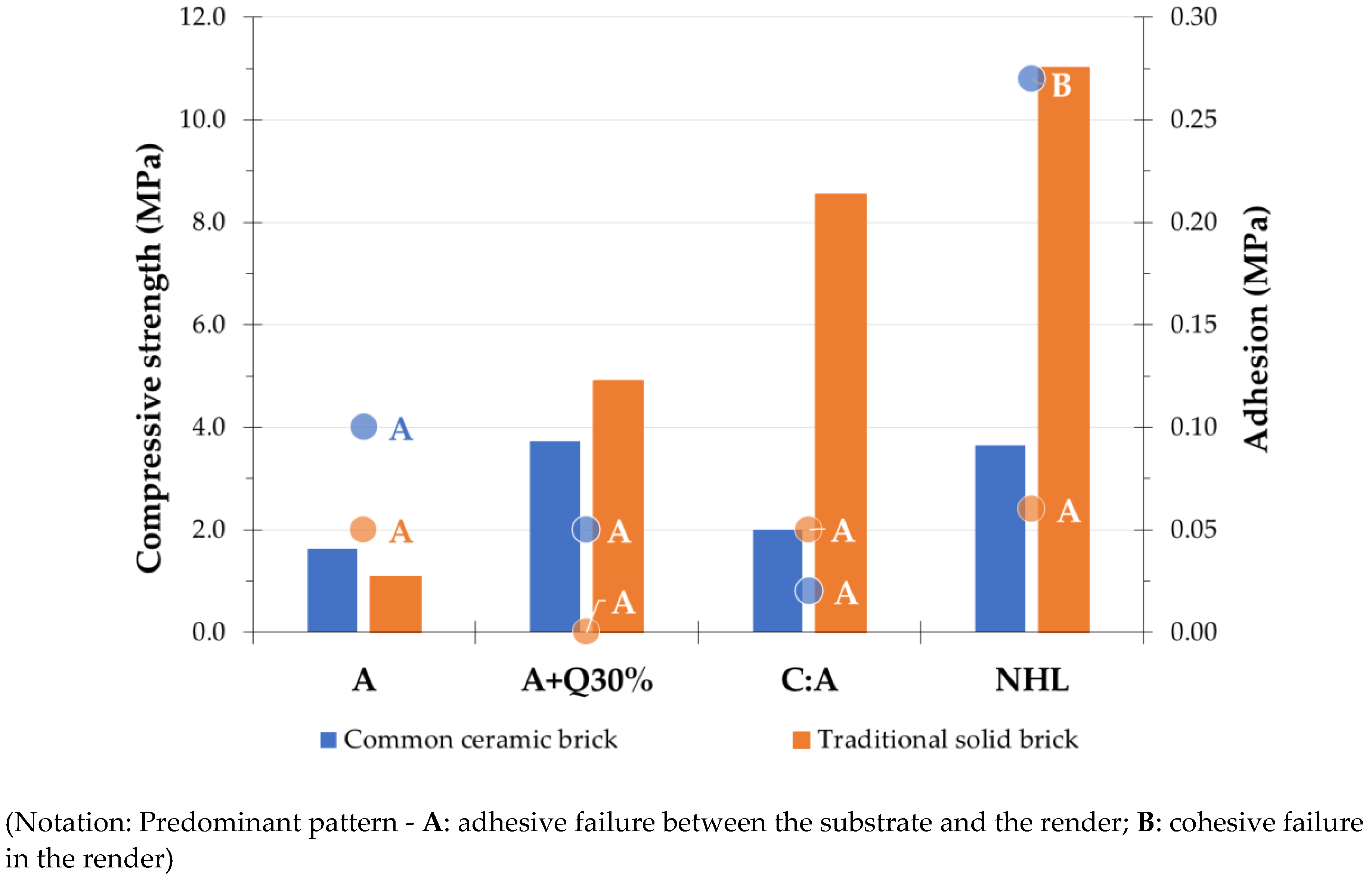

From the physical and mechanical results obtained after 180 days, it is possible to observe, as expected, that there is an increase in the bulk density and a decrease in the porosity as the water absorption of the substrate increases (

Figure 12), which means that the mortars structure become more compact, thus improving, in general, the compressive strength (

Figure 13). However, the modulus of elasticity value tends to fall down (

Figure 11) as well as the adhesion to the substrate (

Figure 13), when the mortars are applied on very porous bricks.

In fact, the quick absorption by the substrate may generate high stress at the interface and therefore microcracking could occur (

Figure 14). Moreover, it may also lead to a significant reduction of the water flow from the fresh mortars to the interface region of the substrate; thus weakening the effective bond, since the number of active pores, which allow the transport of fine particles that strengthen the effective bond, is reduced [

36].

Considering the mortars compositions, despite the lower values of compressive strength, the slaked air lime mortar (A) shows a good performance when used on a very absorbent substrate, with moderate values of modulus of elasticity and of tensile bond strength, which tend to improve with curing time.

A+Q30% reduces significantly its modulus of elasticity value and adhesion when applied on a very absorbent substrate, by comparison with a medium absorbent one. However, the compressive strength consistently increases for application on a more absorbent substrate.

Conversely, in mortars with some hydraulicity, besides the slight reduction of modulus of elasticity (

Figure 11), an increase of more than 50% of the compressive strength is observed (

Figure 13). The NHL mortar, in general, exhibits the highest values of mechanical strengths and high values of dynamic modulus of elasticity, which might produce incompatibility and thus compromise the durability of the ancient buildings, namely with this type of substrate. The C:A mortar, in addition to the slight reduction of modulus of elasticity, shows an improvement of the other physical and mechanical characteristics when applied on a very absorbent substrate.

4.3. The Influence of the Exposition Conditions – Task 3

To study the impact of the environmental conditions of the Fort on the mortars performance, A, A+Q30%, C:A and NHL mortars (reference mortars) were applied in mini-wallettes (with very porous and absorbent bricks) and subjected to the real environment conditions of the Fort (external area) for approximately ten months (September to July).

Regarding the monitoring made throughout the time of exposition, in general, all mortars compositions present an improvement of their performance, with moderate to high values of modulus of elasticity and high values of surface hardness (

Figure 15).

However, comparing to results obtained in laboratory using the same substrate (

Figure 11 – traditional solid brick), the exposition to severe marine environment, although an increment of compressive strength and a decrease of permeability (

Table 6) occurs, reduces the modulus of elasticity values, as well as the compactness, with loss of density and increment of total porosity for all mortars compositions.

The exception is in air lime mortar compositions (A) which increases the modulus of elasticity when subjected to the severe marine environment of the Fort. The enhancing on the modulus of elasticity of mortar A is probably due to the original large pores of the lime mortar matrix, which could accommodate the precipitation of salts inside and block them without producing stresses that damage the matrix [

1]. On the other hand, the fine capillary pore structure of the other mortars compositions improve the compressive strength in standard conditions, while in the Fort environment conditions, however, if salts attack occurs, damage could be observed [

37], especially in the case of sulphates (which is typically present in maritime atmosphere, as well as chlorides), with high relative humidity values, due to the compounds that can be formed (as ettringite), which their fine porosity cannot accommodate.

Nevertheless, the severe marine environment exposition of mortars applied on a porous substrate, at long term, cause a decrease of the adhesion strength for air lime mortars (A and A+Q30%) and an increase for the hydraulic ones (C:A and NHL) (

Table 6). In fact, as well as was observed in laboratory, with very porous substrate, A+Q30% mortar reveals adherence issues, and was even found detached from the substrate at early ages. The NHL mortar presents a substantial increase on the adhesion strength to a porous substrate in severe marine environment exposition, although such difference is not evidenced in the modulus of elasticity (

Figure 11 and

Figure 15), neither on the other physical tests (

Table 6). The increase in adhesion strength in maritime environment may be due to higher humidity in some periods that favoured the hydraulic reactions in the interface. However, NHL mortar presents low values of water permeability, shown by the Karsten tubes tests, which might reduce the drying capacity of the original walls.

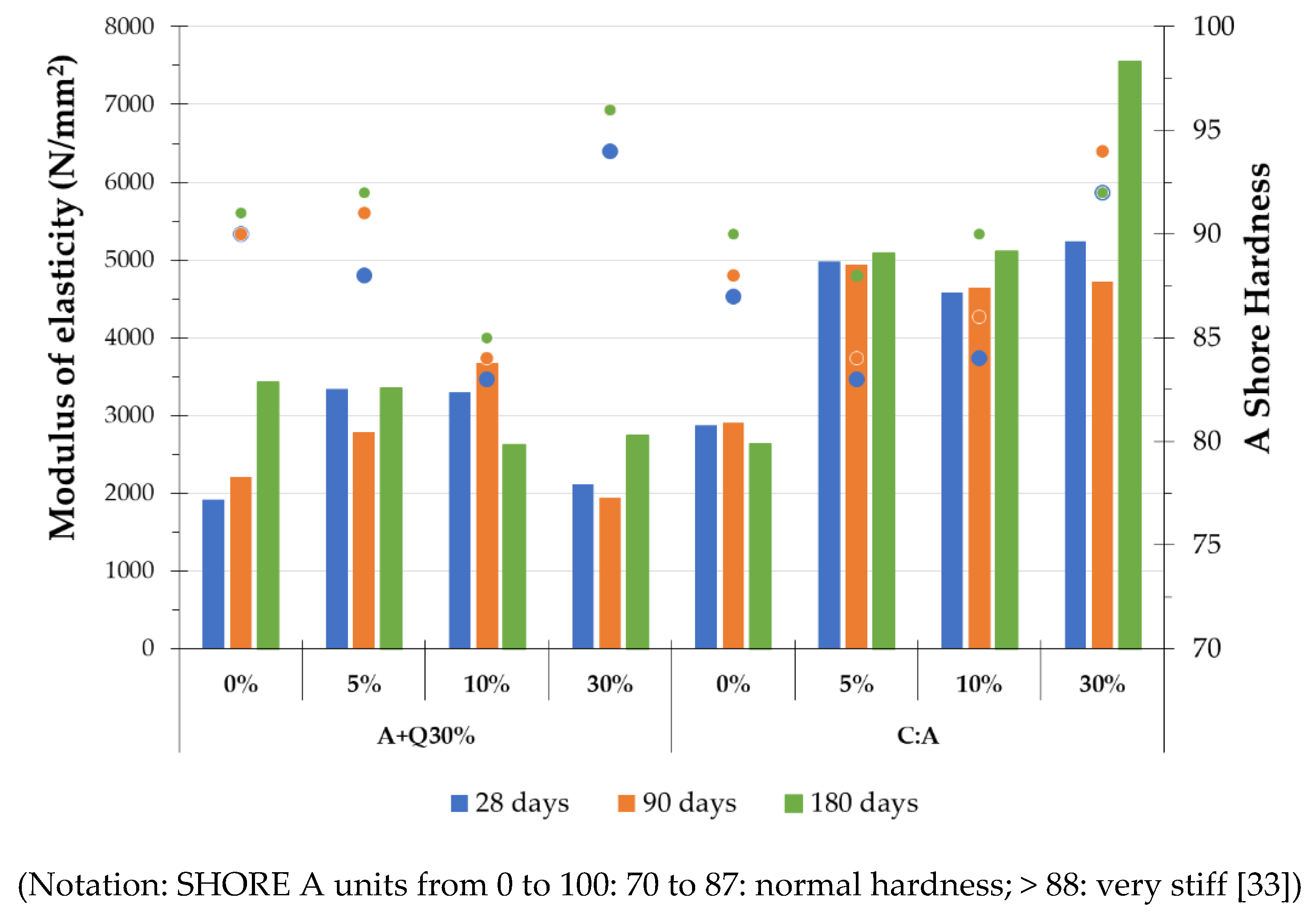

4.4. Improvement of the Mortar Aggregate – Task 4

Considering all the experimental campaigns in laboratory and the in-situ exposition behaviour of all reference mortars study, it was decided to modify the initial formulations of some mortars compositions to improve their performance. It was also decided to make the adjustments by aligning the formulations more closely with of the original mortars.

Two mortars compositions were chosen for this task:

A+Q30% mortar, is the closest to the original formulation [

10], as well as presenting generally good performance, with moderate to high strength and modulus of elasticity. However, when applied on a very porous and absorbent substrate, a decrease in the adhesion to the substrate was registered, which should be analysed in detail.

C:A mortar, has the most balanced performance, even in the aggressive environment of the fort, however an reduction of the flexural strengths and consequently in the adhesion to the substrate were observed when applied on medium absorbent substrate (common ceramic brick substrate).

In both mortars compositions, a fine-tuning of the aggregates, substituting part of the siliceous sand by limestone aggregate in 30% (M

1), 10% (M

2) and 5% (M

3), by volume (

Table 2 and

Figure 3), was made. The mortars compositions were applied on common ceramic bricks, since show water absorption comparable to the external walls of the Fort, and the main results are presented in

Figure 16 and

Table 7.

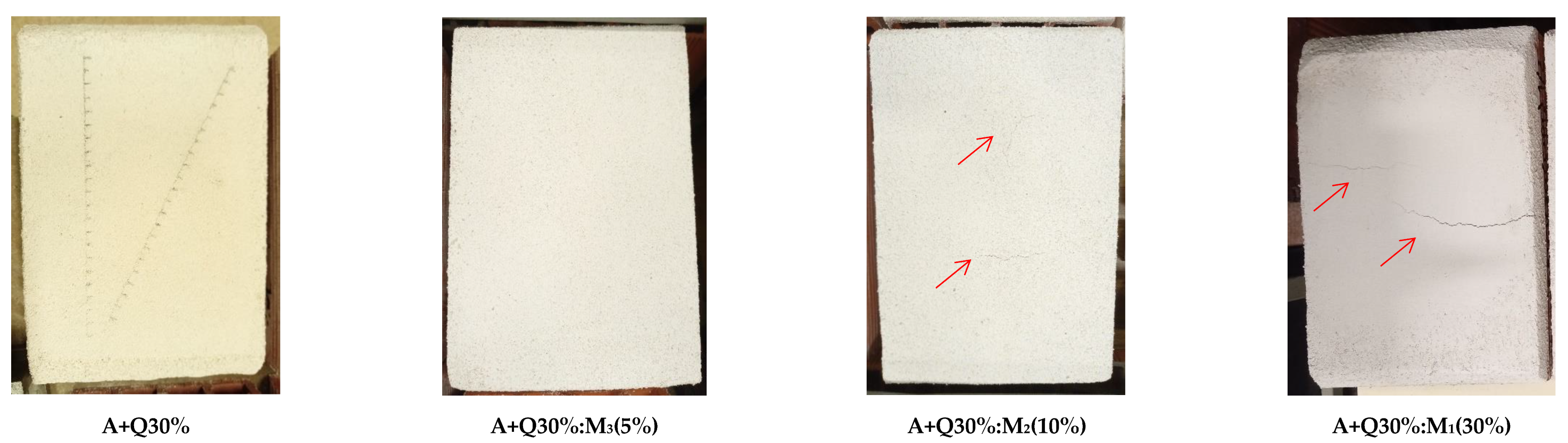

Regarding the laboratory monitorization at 28, 90 and 180 days it is observed that, in general, there was an increase of the modulus of elasticity for the compositions with 5% and 10% of limestone substitution (compared with the mortars only with siliceous sand), for all the mortars compositions, despite the slight decrease of surface hardness in most of the cases. However, with 30% of substitution, the incremental is only observed with C:A mortar.

A possible explanation is that the particles of the lime binder, which are finer than the cement particles, could fill better the very small voids between the aggregates, making the mortars more compact, as can be proved by the values of bulk density (

Table 7). However, for the lime mortars, the use of high contents of limestone can surpass the voids volume available thus not contributing to improve the compactness. Moreover, mortars with a significant amount of fines in their composition, as the A+Q30%:M

1(30%) mortar, have higher probability of microcracking [

38], particularly when they are applied on a very porous substrate (

Figure 17), probably due to the restricted shrinkage, decreasing their performance.

This assumption was confirmed by the flexural strength results (which are affected by the microcracking to a higher degree than the compressive strength ones), which also reveal a decrease of their values for the A+Q30% mortar, as the content of limestone sand increases (

Table 7). Conversely, the compressive strength tends to increase: this behaviour is attributed to the limestone aggregates’ structure, which is similar to the calcitic binder matrix, leading to a reduction of the discontinuities between the lime matrix and the aggregates [

8,

39], thus contributing to the reduction of pore volume in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ), improving the compressive strength [

21]. However, despite the slight increase of the adhesion strength values with 30% of substitution, compared to the reference mortars, the values of adhesion strength are low. Furthermore, the rupture pattern is adhesive between the substrate and the mortar -A. (

Table 7), which means that the failure is not influenced by the mortar cohesion.

Furthermore, at 180 days (

Table 7), the A+Q30% composition with 10% of limestone substitution, by comparison with 5%, in general, shows some decreases in the mechanical characteristics (modulus of elasticity, surface hardness and compressive strength) which can be attributed to microcracking, as visible in

Figure 17. However, a slight increase of the adhesion strength value is observed. Contrary, the C:A composition with 10% of limestone substitution, besides the increase of in the mechanical strengths (flexural and compressive strengths), presents a substantial decrease on the adhesion strength (

Table 7).

Moreover, all mortars with limestone sand show a tendency for a lower water absorption (

Table 7).

5. Conclusions

To choose the most feasible, compatible and durable repair mortars for the rehabilitation of a coastal Fort, several lime-based mortars compositions were applied on two porous substrates, with different water absorptions and porosity, kept in laboratory conditions, and their main physical and mechanical characteristics were analysed and compared. A medium absorbent substrate was materialised by common bricks, while a very absorbent one was simulated by traditional very porous bricks. Additionally, the reference mortars compositions studied in laboratory, were also subjected to in situ conditions, and their performance in the real environment conditions of the Fort were also analysed.

In this investigation, the following aspects were observed:

- 1)

-

Influence of the mortar binder in different exposition conditions

The mortar with slaked air lime (A) - the base mortar - presents relatively low strength and a high rate of water absorption. However, its characteristics tend to improve with the curing time, and they are, in general, higher in real environmental conditions, probably due to the large pore structure, that allows the accommodation of salts without creating high stresses. This mortar composition, under laboratory conditions, presents the highest adhesion of the lime-based mortars, to both substrates (common bricks and traditional very absorbent bricks). Nevertheless, a slight reduction of adherence to the substrate was observed in real conditions.

By adding quicklime to the slaked air lime mortars (A+Q30%), an increase in the mechanical strengths is observed, by comparison with A mortar; however a low adhesion to the substrate is observed when it is applied on a very porous substrate, both in laboratory and in situ conditions. This mortar composition is the closest to the original formulation.

The addition of a small amount of white cement to the slaked air lime mortars (C:A) increases the mechanical strengths, even if the open porosity values are similar to the A mortar. However, besides the satisfactory mechanical results on very porous substrates even in the aggressive environment of the fort, the adhesion to the common ceramic bricks substrate decreases about 80% by comparison with the A mortar.

The natural hydraulic lime mortar (NHL) shows greater mechanical strengths, even at early ages. However, the high values of dynamic modulus of elasticity can cause internal stresses on the mortar matrix, that can generate microcracking, when considered the relatively low flexural strength values obtained, namely when applied on porous and very absorbent ancient substrates. Besides, the low values of water permeability shown by the Karsten tubes tests, may also reduce the drying capacity of the walls. Thus, its durability and performance at long term could be compromised. Moreover, the presence of whitish stains at the mortar surface indicates the precipitation of salts, which, associated with their fine pore structure, suggests a possible trend to early degradation due to salts crystallization.

- 2)

-

Influence of the substrate characteristics

In general, under laboratory conditions, a more absorbent and porous support led to more compact mortar structures, thus, incrementing the compressive strength; however, the modulus of elasticity and the adhesion to the substrate tend to drop down for all mortars compositions, due to a weaker interface.

Therefore, in this particular case study, where an additional mechanical strength with moderate modulus of elasticity and some water permeability is needed, due to the severe marine environment, the A+Q30% mortar seems to conduct to a balanced solution for medium absorbent substrate. Thus, they are recommended for the restoration work of the external walls of the Fort, since the exterior stone walls were found to have moderate to low water absorption. This composition presents higher strength than the other lime-base mortars composition, with moderate deformability, to accommodate stresses that might occur within the substrate without failing. Moreover, it presents a continuous performance evolution during the carbonation process, which is indicates that no significant cracking occurs. Additionally, this is the closest to the original formulation.

However, this composition presents low values of adherence when it is used on very porous and absorbent substrates, thus, it is not recommended for the interior of the Fort that presents vaults of ceramic bricks. For this localization the solution of slaked air lime mortar (A) is recommended, also taking into account that it will not be exposed to rain and to strong wind, so a very high mechanical strength is not needed.

Furthermore, the fine-tuning of the aggregate, substituting part of the siliceous sand by limestone sand in 30% (M1), 10% (M2), and 5% (M3), by volume, on the mortars A+Q30% and C:A, reveals that the mortar with 30% of sand substitution (M1), in general, increases the compressive strength and the adhesion and decreases the porosity and the rate of water absorption for both compositions. However, those mortars suffer high shrinkage, namely A+Q30%:M1 mortar, which leads to microcracking of the matrix, reducing the performance at longer time. Thus, the mortars with 10% and 5% of aggregate substitution present the most balanced results and should be analysed in detail in further studies, as they can be adequate solutions.

Author Contributions

A.R.S, M.d.R.V, and A.S. conceived the formulations and all the parameters of the study; A.R.S. performed the experiments in the laboratories of Portuguese National Laboratory for Civil Engineering; A.R.S. and M.d.R.V. analyzed and discussed the laboratory and in situ tests results; M.d.R.V and A.S. analyzed and discussed the characterization of the original mortars; M.d.R.V. and A.S. were responsible for the supervision of the research; Writing: original draft preparation was performed by A.R.S. and the review and editing was performed by M.d.R.V., A.S. and A.R.S.; M.d.R.V. was responsible for the funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Programme Cultural Entrepreneurship, Cultural Heritage and Cultural Cooperation of European Economic Area (EEA) grants, Culture Programme 2014–2021, within the scope of the “Coastal Memory Fort” project and National Laboratory of Civil engineering within the scope of the “MICR - Integrated Methods for Conservation and Rehabilitation of Built Heritage” (grant number 0803/1102/24170).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank LNEC technicians for their collaboration in carrying out the tests (especially to Bento Sabala), the collaboration of Lhoist Portugal, Secil Argamassas and Lena Agregados in supplying the testing materials, as well as the support and collaboration of Lourinhã Municipality. This work is a contribution to the EEA Grants Culture Programme 2014–2021 “Coastal Memory Fort—Paimogo Fort”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 |

The time found for the reaction temperatures to get lower than 75 ± 5 °C allowing a safe mixing of the mortar. |

References

- Borges, C.; Santos Silva, A.; Veiga, M.R. Durability of ancient lime mortars in humid environment. Construction and Building Materials 2014, 66, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Balen, K.; Papayianni, I.; Van Hees, R.; Binda, L.; Waldum, A. RILEM TC 167-COM report - Introduction to requirements for and functions and properties of repair mortars. Materials and Structures 2005, 38, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TC 203-RHM (Main author: Caspar Groot). Repair mortars for historic masonry: Performance requirements for renders and plasters. Materials and Structures, 2012, 45, 1277–1285. [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.R.; Fragata, A.; Velosa, A.; Magalhães, A.C.; Margalha, G. Lime-based mortars: Viability for use as substitution renders in historical buildings. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 2010, 4, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, C.; Gunneweg, J. Choosing mortars compositions for repoint mortars of historic masonry under severe environmental conditions. In Proceedings of the HMC2013—3rd Historic Mortar Conference, Glasgow, Scotland, 11–14 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Travincas, R.; Torres, I.; Flores-Colen, I.; Francisco, M.; Bellei, P. The influence of the substrate type on the performance of an industrial cement mortar for general use. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 73, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubelli, B.; Van Hees, R.; Groot, C. The Effect of Environmental Conditions on Sodium Chloride Damage. Studies in Conservation 2006, 51, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizzi, A.; Cultrone, G. The difference in behavior between calcitic and dolomitic lime mortars set under dry conditions: The relationship between textural and physical-mechanical properties. Cement and Concrete Research 2012, 42, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, C.; Veiga, M.R.; Papayianni, I.; Van Hees, R.; Secco, M.; Alvarez, J.I.; Faria, P.; Stefanidou, M. RILEM TC 277-LHS report: Lime-based mortars for restoration–a review on long-term durability aspects and experience from practice. Materials and Structures 2022, 55, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.R.; Santos Silva, A.; Marques, A.I.; Sabala, B. Characterization of Existing Mortars of the Fort of Nossa Senhora dos Anjos do Paimogo (Caracterização das Argamassas Existentes no Forte de Nossa Senhora dos Anjos do Paimogo). Report LNEC 67/2022—DED/NRI, Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. (In Portuguese).

- Veiga, M. R.; Velosa, A.; Magalhães, A.C. Experimental applications of mortars with pozzolanic additions. Characterization and performance evaluation. Construction and Building Materials 2009, 23, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nossa Senhora dos Anjos de Paimogo Fort (Forte no Lugar de Paimogo/Forte de Nossa Senhora dos Anjos de Paimogo). Available online: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/SIPA.aspx?id=6327 (accessed on January 2023). (In Portuguese).

- Cruz, J.; Menezes, M.; Tomás, C.; Antunes, V. The Memories Fort (Paimogo-Lourinhã) – a case of safeguarding material and immaterial heritage (O Forte das Memórias (Paimogo-Lourinhã) – um caso de salvaguarda do património material e imaterial). In I Jornadas de Sociologia do Turismo da Associação Portuguesa de Sociologia, Faro, Portugal, 7 - 9 april 2022, 15-16. In Portuguese).

- Santos, A.R.; Veiga, M.R.; Santos Silva, A. Characterization and Assessment of Performance of Innovative Lime Mortars for Conservation of Building Heritage: Paimogo’s Fort, a Case Study. Appl. Sci 2023, 13, 4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 459-1, Building lime; Part 1: Definitions, specifications and conformity criteria. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Veiga, M.R. Air lime mortars: What else do we need to know to apply them in conservation and rehabilitation interventions? A review. Constr. Build. Mater 2017, 157, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, A. Hot-Lime Mortars: A Current Perspective. Journal of Architectural Conservation 2004, 10, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.C.; Muñoz, R.; Oliveira, M.M. The use of a mixture of quicklime and slaked lime in old mortars: The Loriot method (O uso da mistura de cal viva e cal extinta nas argamassas antigas: O método Loriot). Proceedings of HCLB—I Congresso Internacional de História da Construção Luso-Brasileiro, (In Portuguese). Vitória, Brasil, 4–6 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Loriot, A. , 1716-1782— Memoir on a Discovery in the Art of Building (Mémoire sur une Découverte dans l’art de bâtir). De L’imprimerie de Michel Lambert, rue de la Harpe, près Saine Côme, Paris, 1774. (In French). Available online: https://archive.org/details/mmoiresurunedcou00lori/mode/2up (accessed on 9th January 2023).

-

European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 197-1, Cement; Part 1: Composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Santos, A.R.; Veiga, M.R.; Silva, A.S.; de Brito, J.; Álvarez, J.I. Evolution of the microstructure of lime based mortars and influence on the mechanical behaviour: The role of the aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 1015-2, Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry; Part 2: Bulk sampling of mortars and preparation of test mortars. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 1998.

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 16302, Conservation of Cultural Heritage; Test methods: Measurement of water absorption by pipe method. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 772-11, Methods of test for masonry units; Part 11: Determination of water absorption of aggregate concrete, autoclaved aerated concrete, manufactured stone and natural stone masonry units due to capillary action and the initial rate of water absorption of clay masonry units. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). EN 1936, Natural Stone Test Methods; Determination of real density and apparent density, and of total and open porosity. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Climatic conditions recorded in Lisbon and Areia Branca beach: temperature, precipitation, wind speed. Available online: https://www.windguru.cz, (accessed on July 2023).

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), ISO 7619-1, Rubber, vulcanized or thermoplastic - Determination of indentation hardness - Part 1: Durometer method (Shore hardness). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), ASTM D2240-15, Standard Test Method for Rubber Property-Durometer Hardness. West Conshohocken, PA. ASTM International, 2021.

- Fioretti, G.; Andriani, G.F. Ultrasonic wave velocity measurements for detecting decay in carbonate rocks. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology, 2018, 51, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 12504-4, Testing concrete in structures; Part 4: Determination of ultrasonic pulse velocity. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 1015-12, Methods of test for mortar for masonry; Part 12: Determination of adhesive strength of hardened rendering and plastering mortars on substrates. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN), EN 1015-11, Methods of test for mortar for masonry; Part 11: Determination of flexural and compressive strength of hardened mortar. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 1999.

- Tavares, M. The conservation and restoration of old buildings renderings – A methodology for study and repair (A conservação e o restauro de revestimentos exteriores de edifícios antigos – uma metodologia de estudo e reparação). PHD Thesis, Technical University of Lisbon, Faculty of Architecture, Lisbon, november 2009. (In Portuguese).

- Hughes, J.; Taylor, A.K. Compressive and flexural strength testing of brick masonry panels constructed with two contrasting traditionally produced lime mortars. In Workshop Repair Mortars for Historic Masonry, 2009. Editor(s): C. Groot, Publisher: RILEM Publications SARL Pages: 162 - 177 e-ISBN: 978-2-35158-083-7 (RILEM - Publications).

- Arandigoyen, M.; Alvarez, J.I. Pore structure and mechanical properties of cement-lime mortars. Cement and Concrete Research 2007, 37, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.R.; Veiga, M.R.; Santos Silva, A.; de Brito, J. Tensile bond strength of lime-based mortars: The role of the microstructure on their performance assessed by a new non-standard test method. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 29, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanas, J.; Sirera, R.; Alvarez, J.I. Study of the mechanical behaviour of masonry repair lime-based mortars cured and exposed under different conditions. Cement and Concrete Research 2006, 36, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.R.; Santos, A.R.; Santos, D. Natural hydraulic lime mortars for rehabilitation of old buildings: Compatibility and performance. Proceedings of Conference and Gathering of the Building Limes Forum 2015, Building Limes Forum. Cambridge, England, 18-20 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lanas, J.; Alvarez, J.I. Masonry repair lime-based mortars: Factors affecting the mechanical behavior. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

photomicrograph under polarized light with x nicols of the original exterior sample [

13].

Figure 1.

photomicrograph under polarized light with x nicols of the original exterior sample [

13].

Figure 2.

Paimogo fort, in 2021.

Figure 2.

Paimogo fort, in 2021.

Figure 3.

Grain size distributions of the sand from the several sands used in new formulations.

Figure 3.

Grain size distributions of the sand from the several sands used in new formulations.

Figure 4.

Applications on mini-wallettes and exposition in the Fort environment.

Figure 4.

Applications on mini-wallettes and exposition in the Fort environment.

Figure 5.

Non-destructive tests performed at laboratory and in situ on the mortars applied on the bricks samples: (a) Surface hardness measurement; (b) ultrasound test.

Figure 5.

Non-destructive tests performed at laboratory and in situ on the mortars applied on the bricks samples: (a) Surface hardness measurement; (b) ultrasound test.

Figure 7.

Specimens’ mortar preparations for mechanical tests in laboratory.

Figure 7.

Specimens’ mortar preparations for mechanical tests in laboratory.

Figure 8.

Tests performed in laboratory on the mortars specimens at 180 days and at the end of the exposure period: (a) flexural and compressive strength test.; (b) porosity test and its sample.

Figure 8.

Tests performed in laboratory on the mortars specimens at 180 days and at the end of the exposure period: (a) flexural and compressive strength test.; (b) porosity test and its sample.

Figure 9.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results caried out in reference mortars applied on the common ceramic bricks, at 28, 90 and 180 days.

Figure 9.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results caried out in reference mortars applied on the common ceramic bricks, at 28, 90 and 180 days.

Figure 10.

Preparation of the C:A mortars specimens for the strength tests.

Figure 10.

Preparation of the C:A mortars specimens for the strength tests.

Figure 11.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results carried out in reference mortars applied on the common ceramic bricks and on the traditional solid bricks, at 28, 90 and 180 days.

Figure 11.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results carried out in reference mortars applied on the common ceramic bricks and on the traditional solid bricks, at 28, 90 and 180 days.

Figure 12.

Open porosity (bars) and bulk density (circles) from reference mortars applied in different substrates, at 180 days.

Figure 12.

Open porosity (bars) and bulk density (circles) from reference mortars applied in different substrates, at 180 days.

Figure 13.

Compressive strength (bars) and adhesion (circles) values obtained on the reference mortars applied in different substrates, at 180 days.

Figure 13.

Compressive strength (bars) and adhesion (circles) values obtained on the reference mortars applied in different substrates, at 180 days.

Figure 14.

Visual observations of the mortars applied in different substrates, after 180 days.

Figure 14.

Visual observations of the mortars applied in different substrates, after 180 days.

Figure 15.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results carried out in reference mortars subjected to the Fort environment conditions.

Figure 15.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results carried out in reference mortars subjected to the Fort environment conditions.

Figure 16.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results caried out in mortars, with substituting part of the silicious sand by limestone sand, applied on common ceramic bricks, at 28, 90 and 180 days.

Figure 16.

Modulus of elasticity (bars) and A Shore hardness (circles) results caried out in mortars, with substituting part of the silicious sand by limestone sand, applied on common ceramic bricks, at 28, 90 and 180 days.

Figure 17.

A+Q30% mortars surface, where is possible observed cracks in A+Q30%:M1(30%) mortar and with less magnitude in A+Q30%:M2(10%).

Figure 17.

A+Q30% mortars surface, where is possible observed cracks in A+Q30%:M1(30%) mortar and with less magnitude in A+Q30%:M2(10%).

Table 1.

Original mortars compositions and main characteristics [

10].

Table 1.

Original mortars compositions and main characteristics [

10].

| Mortar |

Location |

Mass ratio1

|

Open

Porosity |

Compressive

strength2

|

Modulus of elasticity3

|

Capillary water absorption coef.4

|

| (%) |

(MPa) |

(MPa) |

(kg/(m2.min1/2)) |

| render |

interior |

1:(0.4 : 1.1) |

32 |

3.8 |

2960 |

1.7 |

| exterior |

1:(1.0 : 1.7) |

32 |

5.0 |

5940 |

0.5 |

| repointing |

interior |

1:(1.2 : 2.2) |

29 |

- |

- |

- |

| exterior |

1:(1.5 : 3.0+) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Table 2.

Mortars compositions (by volume).

Table 2.

Mortars compositions (by volume).

| |

Acronyms |

Binder |

Aggregate |

water/binder

ratio*

(by weight) |

| |

Slaked air lime |

Quicklime

(vol. of lime) |

White cement |

Natural hydraulic lime |

Siliceous,

0/2 mm (RT) |

Limestone,

0/1 mm |

Reference

mortars

|

A |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

1.9 |

| A+Q30% |

0.70 |

0.30 |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

1.7 |

| C:A |

0.75 |

- |

0.25 |

- |

3 |

- |

1.8 |

| NHL |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

3 |

- |

1.1 |

Optimized

mortars

|

A+Q30%:M1(30%) |

0.70 |

0.30 |

- |

- |

1.5 |

0.5 |

1.6 |

| A+Q30%:M2(10%) |

0.70 |

0.30 |

- |

- |

1.8 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

| A+Q30%:M3(5%) |

0.70 |

0.30 |

- |

- |

1.9 |

0.1 |

1.8 |

| C:A:M1(30%) |

0.75 |

- |

0.25 |

- |

2.1 |

0.9 |

1.5 |

| C:A:M2(10%) |

0.75 |

- |

0.25 |

- |

2.7 |

0.3 |

1.8 |

| C:A:M3(5%) |

0.75 |

- |

0.25 |

- |

2.9 |

0.1 |

1.8 |

Table 3.

Main physical characteristics of the substrate used.

Table 3.

Main physical characteristics of the substrate used.

| Characteristics |

Substrate |

common

ceramic bricks

(30 x 20 x 11 cm) |

traditional solid

calcined bricks

(23 x 11 x 7 cm) |

|

Water permeability with low pressure by karsten tubes (EN 16302 [23])

|

0.2 ml/cm2, after 30 min |

0.7 ml/cm2, after 10 min |

Water absorption coefficient

(EN 772-11[24])

|

0.6 ± 0.1 kg/m2.min1/2

|

2.4 ± 0.4 kg/m2.min1/2

|

Open porosity

(EN 1936[25])

|

27 ± 0.1 % |

34 ± 0.1 % |

Table 4.

Type of substrate and exposition conditions carried out in each mortar’s compositions.

Table 4.

Type of substrate and exposition conditions carried out in each mortar’s compositions.

| |

Mortars’

acronyms |

Laboratory conditions |

Fort exposure |

| |

common ceramic brick |

traditional solid brick |

mini-wallettes with traditional solid brick |

Reference mortars

(Task 1,2,3)

|

A |

x |

x |

x |

| A+Q30% |

x |

x |

x |

| C:A |

x |

x |

x |

| NHL |

x |

x |

x |

Optimized

mortars

(Task 4)

|

A+Q30%:M1(30%) |

x |

- |

- |

| A+Q30%:M2(10%) |

x |

- |

- |

| A+Q30%:M3(5%) |

x |

- |

- |

| C:A:M1(30%) |

x |

- |

- |

| C:A:M2(10%) |

x |

- |

- |

| C:A:M3(5%) |

x |

- |

- |

Table 5.

Tests results from reference mortars applied on common ceramic bricks specimens, at 180 days (average values, with standard deviation).

Table 5.

Tests results from reference mortars applied on common ceramic bricks specimens, at 180 days (average values, with standard deviation).

Mortars´

acronyms |

Bulk density

(kg/m3) |

Open

Porosity

(%) |

Adhesion*

(MPa) |

Flexural strength (MPa) |

Compressive

strength (MPa) |

Absorbed

water with Karsten tubes (ml - time+) |

| A |

1777 ± 12 |

28 ± 1 |

0.10 ± 0.01 - A |

0.4 ± 0.00 |

1.6 ± 0.02 |

4 – 2 min |

| A+Q30% |

1767 ± 2 |

28 ± 0 |

0.05 ± 0.02 - A |

0.7 ± 0.06 |

3.7 ± 0.17 |

4 – 2 min |

| C:A |

1765 ± 1 |

27 ± 0 |

0.03 ± 0.02 - A |

0.0** |

2.0 ± 0.14 |

4 – 3 min |

| NHL |

1823 ± 1 |

25 ± 0 |

0.27 ± 0.04 - B |

1.8 ± 0.22 |

3.6 ± 0.03 |

4 – 4 min |

Table 6.

Tests results after the monitorization of the reference mortars applied on mini-wallettes, subjected to the environment conditions of the Fort (Fort) vs the performance obtained at 180 days on mortars applied in laboratory traditional solid brick (Lab).

Table 6.

Tests results after the monitorization of the reference mortars applied on mini-wallettes, subjected to the environment conditions of the Fort (Fort) vs the performance obtained at 180 days on mortars applied in laboratory traditional solid brick (Lab).

Mortars´

acronyms |

Bulk density

(kg/m3) |

Open

Porosity (%) |

Adhesion*

(MPa) |

Compressive

strength (MPa) |

Absorbed water with Karsten tubes

(ml – time+) |

| Lab. |

Fort |

Lab. |

Fort |

Lab. |

Fort |

Lab. |

Fort |

Fort |

| A |

1822 ± 0 |

1768 ± 9 |

27 ± 0 |

28 ± 1 |

0.05 ± 0.01 - A |

0.03 ± 0.02 - A |

1.1 ± 0.3 |

2.6 ± 0.0 |

4 – 15 min |

| A+Q30% |

1816 ± 18 |

1765 ± 23 |

27 ± 1 |

28 ± 1 |

0.00 ± 0.00 - A |

** |

4.9 ± 0.5 |

3.41 ± 0.6 |

** |

| C:A |

1794 ± 0 |

1742 ± 10 |

26 ± 0 |

27 ± 1 |

0.05 ± 0.02 - A |

0.24 ± 0.05 - B |

8.5 ± 0.0 |

*** |

4 – 10 min |

| NHL |

1826 ± 0 |

1824 ± 5 |

24 ± 0 |

23 ± 2 |

0.06 ± 0.00 - A |

0.20 ± 0.09 - A |

11.0 ± 1.7 |

11.0 ± 1.5 |

1.5 – 30 min |

Table 7.

Tests results, at 180 days, from the mortars with partial substitution of the siliceous sand by limestone sand, applied on the common ceramic bricks.

Table 7.

Tests results, at 180 days, from the mortars with partial substitution of the siliceous sand by limestone sand, applied on the common ceramic bricks.

Mortars´

acronyms applied on

common ceramic brick |

Bulk density

(kg/m3) |

Open

Porosity

(%) |

Adhesion*

(MPa) |

Flexural strength (MPa) |

Compressive

strength (MPa) |

Absorbed water with Karsten tubes (ml - time) |

| A+Q30% |

1767 ± 2 |

28 ± 0 |

0.05 ± 0.02 - A |

0.7 ± 0.06 |

3.7 ± 0.17 |

4 – 2 min |

| A+Q30%:M3(5%) |

1805 ± 6 |

26 ± 0 |

0.02 ± 0.02 - A |

0.5 ± 0.25 |

2.3 ± 0.20 |

4 – 10 min |

| A+Q30%:M2(10%) |

1808 ± 3 |

26 ± 0 |

0.03 ± 0.02 - A |

0.5 ± 0.13 |

2.1 ± 0.09 |

4 – 10 min |

| A+Q30%:M1(30%) |

1921 ± 12 |

24 ± 1 |

0.06 ± 0.01 - B |

0.4 ± 0.03 |

4.3 ± 0.19 |

0.5 – 30 min |

| C:A |

1765 ± 1 |

27 ± 0 |

0.03 ± 0.02 - A |

0.0** |

2.0 ± 0.14 |

4 – 3 min |

| C:A:M3(5%) |

1797 ± 2 |

28 ± 0 |

0.10 ± 0.05 - A |

0.4 ± 0.10 |

1.5 ± 0.40 |

0.7 – 30 min |

| C:A:M2(10%) |

1790 ± 8 |

28 ± 1 |

0.02 ± 0.01 - A |

0.6 ± 0.07 |

2.1 ± 0.12 |

4 – 10 min |

| C:A:M1(30%) |

1948 ± 2 |

22 ± 0 |

0.08 ± 0.03 - A |

0.6 ± 0.05 |

4.8 ± 0.13 |

4 – 5 min |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).