Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Main Features of IL-2 and Tumor Specific Targeting of IL-2

3. IL-2 Immunotoxins as Antibody-Drug Conjugates to Target and Fight Cancer Cells

4. Immunotherapy Using Combined Tumor Microenvironment-Targeted IL-2 Cytokine

5. Therapeutic Relevance of Enhancing Effector Cytolytic CD8+ T Cell Responses Induced by the Combination of Immunocytokine IL-2 with PD-1 Cis-Targeting

6. Role of Radiotherapy in the Triggering Anti-Tumor Therapeutic Responses in Combined Tumor-Targeted IL-2 Treatments

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sinicrope, FA. : Turk MJ. Immune checkpoint blockade: timing is everything. J Immunother Cancer. 2024 Aug 28;12(8):e009722. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutros C, Herrscher H, Robert C. Progress in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor for Melanoma Therapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2024 Oct;38(5):997-1010. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain SM, Carpenter C, Eccles MR. Genomic and Epigenomic Biomarkers of Immune Checkpoint Immunotherapy Response in Melanoma: Current and Future Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 30;25(13):7252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhima N, Belbaraka R, Langouo Fontsa MD. Single agent vs combination immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: a review of the evidence. Curr Opin Oncol. 2024 Mar 1;36(2):69-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi S, Kumar A. Safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors: An updated comprehensive disproportionality analysis and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024 Aug;200:104398. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada K, Takeuchi M, Fukumoto T, Suzuki M, Kato A, Mizuki Y, Yamada N, Kaneko T, Mizuki N, Horita N. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic uveal melanoma: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 3;14(1):7887. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian J, Quek C. Understanding the Tumor Microenvironment in Melanoma Patients with In-Transit Metastases and Its Impacts on Immune Checkpoint Immunotherapy Responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Apr 11;25(8):4243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoreifi A, Vaishampayan U, Yin M, Psutka SP, Djaladat H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy Before Nephrectomy for Locally Advanced and Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2024 Feb 1;10(2):240-248. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa T, Mori K, Matsukawa A, Kawada T, Katayama S, Bekku K, Laukhtina E, Rajwa P, Quhal F, Pradere B, Fukuokaya W, Iwatani K, Murakami M, Bensalah K, Grünwald V, Schmidinger M, Shariat SF, Kimura T. Updated systematic review and network meta-analysis of first-line treatments for metastatic renal cell carcinoma with extended follow-up data. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024 Jan 30;73(2):38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blas L, Monji K, Mutaguchi J, Kobayashi S, Goto S, Matsumoto T, Shiota M, Inokuchi J, Eto M. Current status and future perspective of immunotherapy for renal cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2024 Aug;29(8):1105-1114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langouo Fontsa M, Padonou F, Willard-Gallo K. Biomarkers and immunotherapy: where are we? Curr Opin Oncol. 2022 Sep 1;34(5):579-586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca AJ, Lyons AB, Flies AS. Cytokines: Signalling Improved Immunotherapy? Curr Oncol Rep. 2021 Jul 16;23(9):103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokaz MC, Baik CS, Houghton AM, Tseng D. New Immuno-oncology Targets and Resistance Mechanisms. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2022 Sep;23(9):1201-1218. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Amico S, Tempora P, Melaiu O, Lucarini V, Cifaldi L, Locatelli F, Fruci D. Targeting the antigen processing and presentation pathway to overcome resistance to immune checkpoint therapy. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 22;13:948297. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi GR, Mostafavi S, Bastan S, Ebrahimi N, Gharibvand RS, Eskandari N. Immunologic tumor microenvironment modulators for turning cold tumors hot. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2024 May;44(5):521-553. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin Y, Huang Y, Ren H, Huang H, Lai C, Wang W, Tong Z, Zhang H, Wu W, Liu C, Bao X, Fang W, Li H, Zhao P, Dai X. Nano-enhanced immunotherapy: Targeting the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Biomaterials. 2024 Mar;305:122463. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggi A, Varesano S, Zocchi MR. How to Hit Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Make the Tumor Microenvironment Immunostimulant Rather Than Immunosuppressive. Front Immunol. 2018 Feb 19;9:262. Erratum in: Front Immunol. 2018 Jun 11;9:1342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggi A, Musso A, Dapino I, Zocchi MR. Mechanisms of tumor escape from immune system: role of mesenchymal stromal cells. Immunol Lett. 2014 May-Jun;159(1-2):55-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra Y, Weeraratna AT. Fibroblasts in cancer: Unity in heterogeneity. Cell. 2023 Apr 13;186(8):1580-1609. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang F, Ma Y, Li D, Wei J, Chen K, Zhang E, Liu G, Chu X, Liu X, Liu W, Tian X, Yang Y. Cancer associated fibroblasts and metabolic reprogramming: unraveling the intricate crosstalk in tumor evolution. J Hematol Oncol. 2024 Sep 2;17(1):80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011 Mar 4;144(5):646-74.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000 Jan 7;100(1):57-70.

- Molgora, M.; Bonavita, E.; Ponzetta, A.; Riva, F.; Barbagallo, M.; Jaillon, S.; Popović, B.; Bernardini, G.; Magrini, E.; Gianni, F.; Zelenay, S.; Jonjić, S.; Santoni, A.; Garlanda, C.; Mantovani, A. IL-1R8 is a checkpoint in NK cells regulating anti-tumour and anti-viral activity. Nature. 2017 Nov 2;551(7678):110-114. [CrossRef]

- Mattiola, I.; Tomay, F.; De Pizzol, M.; Gomes, R.S.; Savino, B.; Gulic, T.; Doni, A.; Lonardi, S.; Boutet, M.A.; Nerviani, A.; Carriero, R.; Molgora, M.; Stravalaci, M.; Morone, D.; Shalova, I.N.; Lee, Y.; Biswas, S.K.; Mantovani, G.; Sironi, M.; Pitzalis, C.; Vermi, W.; Bottazzi, B.; Mantovani, A.; Locati, M. The interplay of the macrophage tetraspan MS4A4A with Dectin-1 and its role in NK cell-mediated resistance to metastasis. Nat Immunol. 2019 Aug;20(8):1012-1022. [CrossRef]

- Locati, M.; Curtale, G.; Mantovani, A. Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. nnu Rev Pathol. 2020 Jan 24:15:123-147. [CrossRef]

- Albini, A.; Bruno, A.; Noonan, D.N.; Mortara, L. Contribution to Tumor Angiogenesis From Innate Immune Cells Within the Tumor Microenvironment: Implications for Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018 Apr 5:9:527. [CrossRef]

- Bassani, B.; Baci, D.; Gallazzi, M.; Poggi, A.; Bruno, A.; Mortara, L. Natural Killer Cells as Key Players of Tumor Progression and Angiogenesis: Old and Novel Tools to Divert Their Pro-Tumor Activities into Potent Anti-Tumor Effects. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Apr 1;11(4):461. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.; Mortara, L.; Baci, B.; Noonan, D.M.; Albini, A. Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells Interactions With Natural Killer Cells and Pro-angiogenic Activities: Roles in Tumor Progression. Front Immunol. 2019 Apr 18;10:771. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022 Jan;12(1):31-46. [CrossRef]

- Song, K. Current Development Status of Cytokines for Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2024 Jan 1; 32(1): 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Tang, R. , Zhao X. Engineering cytokines for cancer immunotherapy: a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2023 Jul 6:14:1218082. [CrossRef]

- Malek, T.R. The biology of interleukin-2. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:453-79. [CrossRef]

- Radi, H.; Ferdosi-Shahandashti, E.; Kardar, G.A.; Hafezi, N. An Updated Review of Interleukin-2 Therapy in Cancer and Autoimmune Diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2024 Apr;44(4):143-157. [CrossRef]

- Shouse, A.N.; LaPorte, K.M.; Malek, T.R. Interleukin-2 signaling in the regulation of T cell biology in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2024 Mar 12;57(3):414-428. [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, T.; Tagaya, Y.; Bamford, R. Interleukin-2, interleukin-15, and their receptors. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;16(3-4):205-26. [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, T.A. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006 Aug;6(8):595-601. [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, T.A. The interleukin-2 receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991 Feb 15;266(5):2681-4.

- Lokau, J.; Petasch, L.M.; Garbers, C. The soluble IL-2 receptor α/CD25 as a modulator of IL-2 function. Immunology. 2024 Mar;171(3):377-387. [CrossRef]

- Malek, T.R.; Castro, I. Interleukin-2 receptor signaling: at the interface between tolerance and immunity. Immunity. 2010 Aug 27;33(2):153-65. [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Lin, J.X.; Leonard, W.J. Interleukin-2 at the crossroads of effector responses, tolerance, and immunotherapy. Immunity. 2013 Jan 24;38(1):13-25. [CrossRef]

- Raeber, M.E.; Sahin, D.; Boyman, O. Interleukin-2-based therapies in cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Nov 9;14(670):eabo5409. [CrossRef]

- Rokade, S.; Damani, A.M.; Oft, M.; Emmerich, J. IL-2 based cancer immunotherapies: an evolving paradigm. Front Immunol. 2024 Jul 24;15:1433989. [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, M.H.; Lotze, M.T. Interleukin-2: solid-tumor therapy. Oncology. 1994 Mar-Apr;51(2):154-69. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Ahmed, R. Harnessing CD8 T cell responses using PD-1-IL-2 combination therapy. Trends Cancer. 2024 Apr;10(4):332-346. [CrossRef]

- Krieg, C.; Létourneau, S.; Pantaleo, G.; Boyman, O. Improved IL-2 immunotherapy by selective stimulation of IL-2 receptors on lymphocytes and endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jun 29;107(26):11906-11. Epub 2010 Jun 14. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Jan 3;109(1):345. [CrossRef]

- Puri, R.K.; Rosenberg, S.A. Combined effects of interferon alpha and interleukin 2 on the induction of a vascular leak syndrome in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1989;28(4):267-74. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.J.; Miller, F.N.; Sims, D.E.; Abney, D.L.; Schuschke, D.A.; Corey, T.S. Interleukin 2 acutely induces platelet and neutrophil-endothelial adherence and macromolecular leakage. Cancer Res. 1992 Jun 15;52(12):3425-31.

- Siddall, E.; Khatri, M.; Radhakrishnan, J. Capillary leak syndrome: etiologies, pathophysiology, and management. Kidney Int. 2017 Jul;92(1):37-46. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kishimoto, T. Interplay between interleukin-6 signaling and the vascular endothelium in cytokine storms. Exp Mol Med. 2021 Jul;53(7):1116-1123. [CrossRef]

- van Hinsbergh, V.W.; van Nieuw Amerongen, G.P. Endothelial hyperpermeability in vascular leakage. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002 Nov;39(4-5):171-2. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.; Kwon, Y.G. CU06-1004 as a promising strategy to improve anti-cancer drug efficacy by preventing vascular leaky syndrome. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Aug 30;14:1242970. [CrossRef]

- Den Otter, W.; Jacobs, J.J.; Battermann, J.J.; Hordijk, G.J.; Krastev, Z.; Moiseeva, E.V.; Stewart, R.J.; Ziekman, P.G.; Koten, J.W. Local therapy of cancer with free IL-2. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008 Jul;57(7):931-50. [CrossRef]

- Jackaman, C.; Bundell, C.S.; Kinnear, B.F.; Smith, A.M.; Filion, P.; van Hagen, D.; Robinson, B.W.; Nelson, D.J. IL-2 intratumoral immunotherapy enhances CD8+ T cells that mediate destruction of tumor cells and tumor-associated vasculature: a novel mechanism for IL-2. J Immunol. 2003 Nov 15;171(10):5051-63. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.J.; Sparendam, D.; Den Otter, W. Local interleukin 2 therapy is most effective against cancer when injected intratumourally. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005 Jul;54(7):647-54. [CrossRef]

- Spolski, R.; Li, P.; Leonard, W.J. Biology and regulation of IL-2: from molecular mechanisms to human therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018 Oct;18(10):648-659. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, S.; He, B.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Peng, P.; Zhao, J.; Zang, Y. Immunotherapeutic strategy based on anti-OX40L and low dose of IL-2 to prolong graft survival in sensitized mice by inducing the generation of CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021 Aug;97:107663. [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, G.; Meroni, L.; Molteni, C.; Bandera, A.; Franzetti, F.; Galli, M.; Moroni, M.; Clerici, M.; Gori, A. Interleukin-2 immunotherapy exerts a differential effect on CD4 and CD8 T cell dynamics. AIDS. 2004 Jan 23;18(2):211-6. [CrossRef]

- Sockolosky, J.T.; Trotta, E.; Parisi, G.; Picton, L.; Su, L.L.; Le, A.C.; Chhabra, A.; Silveria, S.L.; George, B.M.; King, I.C.; Tiffany, M.R. , Jude K.; Sibener L.V.; Baker D.; Shizuru J.A.; Ribas A.; Bluestone J.A.; Garcia K.C. Selective targeting of engineered T cells using orthogonal IL-2 cytokine-receptor complexes. Science. 2018 Mar 2;359(6379):1037-1042. [CrossRef]

- Horton, B.L.; D'Souza, A.D.; Zagorulya, M.; McCreery, C.V.; Abhiraman, G.C.; Picton, L.; Sheen, A.; Agarwal, Y.; Momin, N.; Wittrup, K.D.; White, F.M.; Garcia, K.C.; Spranger, S. Overcoming lung cancer immunotherapy resistance by combining nontoxic variants of IL-12 and IL-2. JCI Insight. 2023 Oct 9;8(19):e172728. [CrossRef]

- Bentebibel, S.E.; Diab, A. Cytokines in the Treatment of Melanoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021 ;23(7):83. 18 May. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, G.; Relova-Hernández, E.; Pérez-Riverón, A.; Castro-Martínez, C.; Diaz-Bravo, O.; Infante, Y.C.; Gómez, T.; Solozábal, J.; DíazBravo, A.B.; Schubert, M.; Becker, M.; Pérez-Massón, B.; Pérez-Martínez, D.; Alvarez-Arzola, R.; Guirola, O.; Chinea, G.; Graca, L.; Dübel, S.; León, K.; Carmenate, T. Molecular reshaping of phage-displayed Interleukin-2 at beta chain receptor interface to obtain potent super-agonists with improved developability profiles. Commun Biol. 2023 Aug 9;6(1):828. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Y.X. Facts and Hopes on Chimeric Cytokine Agents for Cancer Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2024 May 15;30(10):2025-2038) Indeed, the generation of several.

- Baars, J.W.; de Boer, J.P.; Wagstaff, J.; Roem, D.; Eerenberg-Belmer, A.J.; Nauta, J.; Pinedo, H.M.; Hack, C.E. Interleukin-2 induces activation of coagulation and fibrinolysis: resemblance to the changes seen during experimental endotoxaemia. Br J Haematol. 1992 Oct;82(2):295-301. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D.; Clabaugh, S.E.; Smith, D.R.; Stevens, R.B.; Wrenshall, L.E. Interleukin-2 is present in human blood vessels and released in biologically active form by heparanase. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012 Feb;90(2):159-67. [CrossRef]

- Locker, G.J.; Kapiotis, S.; Veitl, M.; Mader, R.M.; Stoiser, B.; Kofler, J.; Sieder, A.E.; Rainer, H.; Steger, G.G.; Mannhalter, C.; Wagner, O.F. Activation of endothelium by immunotherapy with interleukin-2 in patients with malignant disorders. Br J Haematol. 1999 Jun;105(4):912-9. [CrossRef]

- Baars, J.W.; Hack, C.E.; Wagstaff, J.; Eerenberg-Belmer, A.J.; Wolbink, G.J.; Thijs, L.G.; Strack van Schijndel, R.J.; van der Vall, H.L.; Pinedo, H.M. The activation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and the complement system during immunotherapy with recombinant interleukin-2. Br J Cancer. 1992 Jan;65(1):96-101. [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.B.; Gillies, S.D. Immunocytokines: amplification of anti-cancer immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003 May;52(5):297-308. [CrossRef]

- Sondel, P.M.; Hank, J.A.; Gan, J.; Neal, Z.; Albertini, M.R. Preclinical and clinical development of immunocytokines. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003 Jun;4(6):696-700.

- Beig Parikhani, A.; Dehghan, R.; Talebkhan, Y.; Bayat, E.; Biglari, A.; Shokrgozar, M.A.; Ahangari Cohan, R.; Mirabzadeh, E.; Ajdary, S.; Behdani, M. A novel nanobody-based immunocytokine of a mutant interleukin-2 as a potential cancer therapeutic. AMB Express. 2024 Feb 9;14(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.; Ren, J.; Liu, Q.; Glassman, C.R.; Sheahan, T.P.; Picton, L.K.; Moreira, F.R.; Rustagi, A.; Jude, K.M.; Zhao, X.; Blish, C.A.; Baric, R.S.; Su, L.L.; Garcia, K.C. Facile discovery of surrogate cytokine agonists. Cell. 2022 Apr 14;185(8):1414-1430.e19. [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; McKinstry, W.J.; Pham, T.; Newman, J.; Layton, D.S.; Bean, A.G.; Chen, Z.; Laurie, K.L.; Borg, K.; Barr, I.G.; Adams, T.E. Structural and functional characterisation of ferret interleukin-2. Dev Comp Immunol. 2016 Feb;55:32-8. [CrossRef]

- Boersma, B.; Poinot, H.; Pommier, A. Stimulating the Antitumor Immune Response Using Immunocytokines: A Preclinical and Clinical Overview. Pharmaceutics. 2024 Jul 24;16(8):974. [CrossRef]

- Prodi, E.; Neri, D.; De Luca, R. Tumor-Homing Antibody-Cytokine Fusions for Cancer Therapy. Onco Targets Ther. 2024 Aug 29;17:697-715. [CrossRef]

- Fabilane, C.S.; Stephenson, A.C.; Leonard, E.K.; VanDyke, D.; Spangler, J.B. Cytokine/Antibody Fusion Protein Design and Evaluation. Curr Protoc. 2024 May;4(5):e1061. [CrossRef]

- Santollani, L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Maiorino, L.; Palmeri, J.R.; Stinson, J.A.; Duhamel, L.R.; Qureshi, K.; Suggs, J.R.; Porth, O.T.; Pinney, W. 3rd.; Sari R.A.; Wittrup K.D.; Irvine D.J. Local delivery of cell surface-targeted immunocytokines programs systemic anti-tumor immunity. Nat Immunol. 2024 Oct;25(10):1820-1829. [CrossRef]

- Drago, J.Z.; Modi, S.; Chandarlapaty, S. Unlocking the potential of antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021 Jun;18(6):327-344. [CrossRef]

- Dumontet, C.; Reichert, J.M.; Senter, P.D.; Lambert, J.M.; Beck, A. Antibody-drug conjugates come of age in oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023 Aug;22(8):641-661. [CrossRef]

- Phuna, Z.X.; Kumar, P.A.; Haroun, E.; Dutta, D.; Lim, S.H. Antibody-drug conjugates: Principles and opportunities. Life Sci. 2024 Jun 15;347:122676. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchikama, K.; Anami, Y.; Ha, S.Y.Y.; Yamazaki, C.M. Exploring the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024 Mar;21(3):203-223. [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, P.; Carmagnani Pestana, R.; Corti, C.; Modi, S.; Bardia, A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Cortes, J.; Soria, J.C.; Curigliano, G. Antibody-drug conjugates: Smart chemotherapy delivery across tumor histologies. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022 Mar;72(2):165-182. [CrossRef]

- Merle, G.; Friedlaender, A.; Desai, A.; Addeo, A. Antibody Drug Conjugates in Lung Cancer. Cancer J. 2022 Nov-Dec 01;28(6):429-435. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Ali, S.; Mata, D.G.M.M.; Lohmann, A.E.; Blanchette, P.S. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Breast Cancer: Ascent to Destiny and Beyond-A 2023 Review. Curr Oncol. 2023 Jul 6;30(7):6447-6461. [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, N.L.; Brown, M.P.; Liapis, V.; Staudacher, A.H. Antibody drug conjugates: hitting the mark in pancreatic cancer? J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023 Oct 25;42(1):280. [CrossRef]

- Baah, S.; Laws, M.; Rahman, K.M. Antibody-Drug Conjugates-A Tutorial Review. Molecules. 2021 ;26(10):2943. 15 May. [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.Y.; Wu, H.X.; Meng, Q.; Xu, R.H. Development of antibody-drug conjugates in cancer: Overview and prospects. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2024 Jan;44(1):3-22. [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, P.; Ricciuti, B.; Pradhan, S.M.; Tolaney, S.M. Optimizing the safety of antibody-drug conjugates for patients with solid tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023 Aug;20(8):558-576. [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, E.; Repetto, M.; Boscolo Bielo, L.; Tarantino, P.; Curigliano, G. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Breast Cancer: What Is Beyond HER2? Cancer J. 2022 Nov-Dec 01;28(6):436-445. [CrossRef]

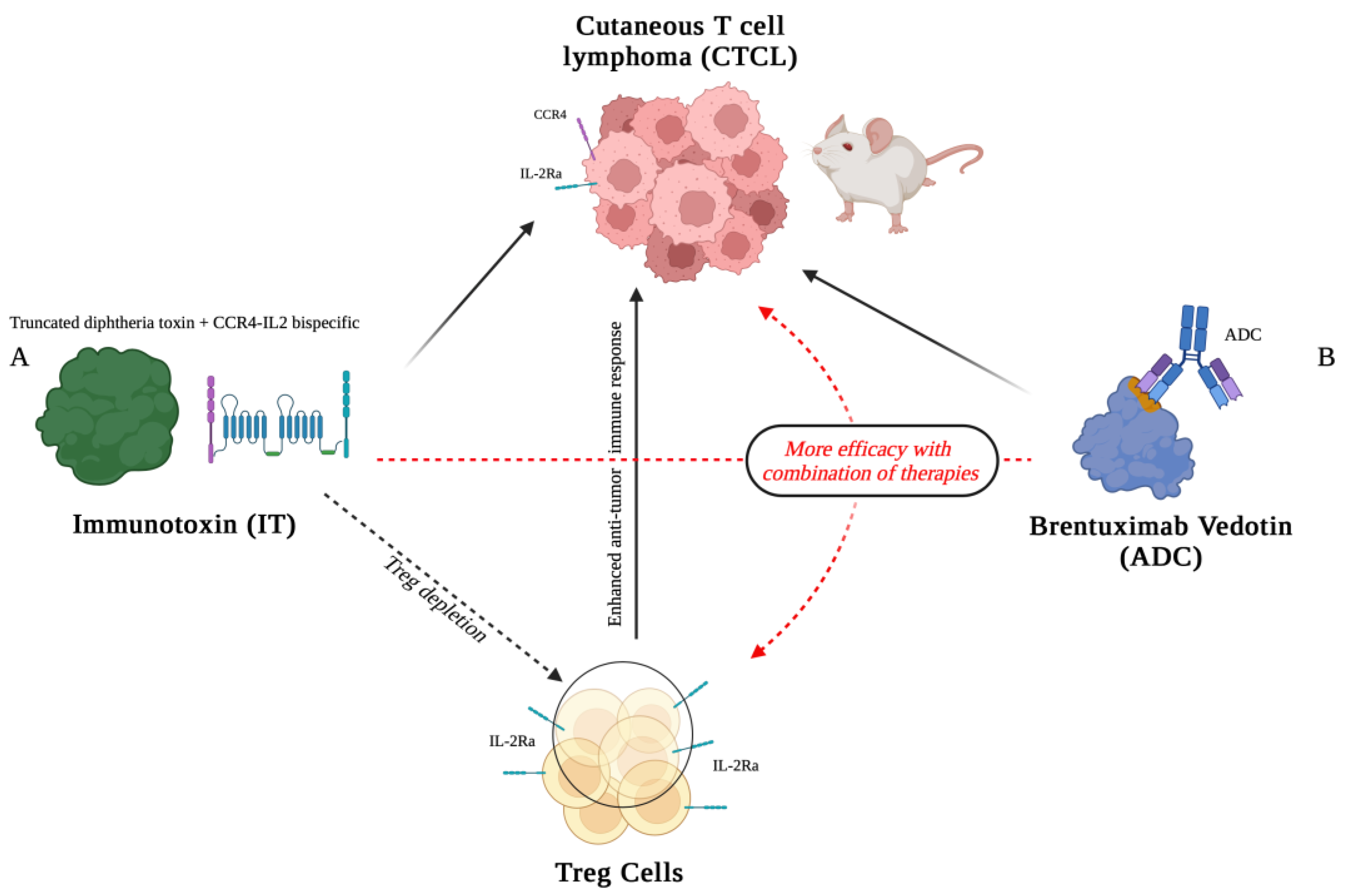

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Qi, Z.; Johnson, A.C.; Mathes, D. ; Pomfret.;.A, Rubin E.; Huang C.A.; Wang Z. Bispecific human IL2-CCR4 immunotoxin targets human cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Mol Oncol. 2020 May;14(5):991-1000. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Ramakrishna, R.; Mintzlaff, D.; Mathes, D.W.; Pomfret, E.A.; Lucia, M.S.; Gao, D.; Haverkos, B.M.; Wang, Z. CCR4-IL2 bispecific immunotoxin is more effective than brentuximab for targeted therapy of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in a mouse CTCL model. FEBS Open Bio. 2023 Jul;13(7):1309-1319. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Ramakrishna R, Wang Y, Qiu Y, Ma J, Mintzlaff D, Zhang H, Li B, Hammell B, Lucia MS, Pomfret E, Su AA, Washington KM, Mathes DW, Wang Z. Toxicology, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity studies of CCR4-IL2 bispecific immunotoxin in rats and minipigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024 Apr 5;968:176408. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, M.A.; Hobeika, A.C.; Osada, T.; Serra, D.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Lyerly, H.K.; Clay, T.M. Depletion of human regulatory T cells specifically enhances antigen-specific immune responses to cancer vaccines. Blood. 2008; 112:610–618.

- Litzinger, M.T.; Fernando, R.; Curiel, T.J.; Grosenbach, D.W.; Schlom, J.; Palena, C. IL-2 immunotoxin denileukin diftitox reduces regulatory T cells and enhances vaccine-mediated T-cell immunity. Blood. 2007; 110:3192–3201.

- Yamada, Y.; Aoyama, A.; Tocco, G.; Boskovic, S.; Nadazdin, O.; Alessandrini, A.; Madsen, J.C.; Cosimi, A.B.; Benichou, G.; Kawai, T. Differential effects of denileukin diftitox IL-2 immunotoxin on NK and regulatory T cells in nonhuman primates. J Immunol. 2012 Jun 15;188(12):6063-70.

- Carnemolla, B.; Borsi, L.; Balza, E.; Castellani, P.; Meazza, R. ; Berndt A, Ferrini S.; KosmehL H.; Neri, D.; Zardi L. Enhancement of the antitumor properties of interleukin-2 by its targeted delivery to the tumor blood vessel extracellular matrix. Blood (2002) 99:1659-65. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.; Schulz, P.; Scholz, A.; Wiedenmann, B.; Menrad, A. The targeted immunocytokine L19-IL2 efficiently inhibits the growth of orthotopic pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2008) 14:4951–60. [CrossRef]

- Schliemann, C.; Palumbo, A.; Zuberbuhler, K.; Villa, A.; Kaspar, M.; Trachsel, E.; Klapper, W.; Menssen, H.D.; Neri, N. Complete eradication of human B-cell lymphoma xenografts using rituximab in combination with the immunocytokine L19-IL2. Blood (2009) 113:2275–83. [CrossRef]

- Balza, E.; Carnemolla, B.; Mortara, L.; Castellani, P.; Soncini, D.; Accolla, R.S.; Borsi, L. Therapy-induced antitumor vaccination in neuroblastomas by the combined targeting of IL-2 and TNFalpha. Int J Cancer (2010) 127:101–10. [CrossRef]

- Schwager, K.; Hemmerle, T.; Aebischer, D.; Neri, D. The immunocytokine L19-IL2 eradicates cancer when used in combination with CTLA-4 blockade or with L19-TNF. J Invest Dermatol. (2013) 133:751–8. [CrossRef]

- Pretto, F.; Elia, G.; Castioni, N.; Neri, D. Preclinical evaluation of IL2-based immunocytokines supports their use in combination with dacarbazine, paclitaxel and TNF-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2014) 63:901–10. [CrossRef]

- Orecchia, P.; Conte, R.; Balza, E.; Pietra, G.; Mingari, M.C.; Carnemolla, B. Targeting Syndecan-1, a molecule implicated in the process of vasculogenic mimicry, enhances the therapeutic efficacy of the L19-IL2 immunocytokine in human melanoma xenografts. Oncotarget (2015) 6:37426–42. [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Waldhauer, I.; Nicolini, V.G.; Freimoser-Grundschober, A.; Nayak, T.; Vugts, D.J.; Dunn, C.; Bolijn, M.; Benz, J.; Stihle, M.; Lang, S.; Roemmele, M.; Hofer, T.; van Puijenbroek, E.; Wittig, D.; Moser, S.; Ast, O.; Brünker, P.; Gorr, I.H.; Neumann, S.; de Vera Mudry, M.C. , Hinton H.; Crameri F.; Saro J.; Evers S.; Gerdes C.; Bacac M.; van Dongen G.; Moessner E.; Umaña P. Cergutuzumab amunaleukin (CEA-IL2v), a CEAtargeted IL-2 variant-based immunocytokine for combination cancer immunotherapy: Overcoming limitations of aldesleukin and conventional IL-2-based immunocytokines. Oncoimmunology (2017) 6:e1277306. [CrossRef]

- Menssen, H.D.; Harnack, U.; Erben, U.; Neri, D.; Hirsch, B.; Durkop, H. Antibodybased delivery of tumor necrosis factor (L19-TNFalpha) and interleukin-2 (L19-IL2) to tumor-associated blood vessels has potent immunological and anticancer activity in the syngeneic J558L BALB/c myeloma model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2018) 144:499–507. [CrossRef]

- Mortara, L.; Balza, E.; Bruno, A.; Poggi, A.; Orecchia, P.; Carnemolla, B. Anti-cancer Therapies Employing IL-2 Cytokine Tumor Targeting: Contribution of Innate, Adaptive and Immunosuppressive Cells in the Anti-tumor Efficacy. Front Immunol 18 Dec 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, J.W.; Morillon, Y.M. 2nd, Schlom J. NHS-IL12, a Tumor-Targeting Immunocytokine. Immunotargets Ther. 2021 ;10:155-169. 27 May. [CrossRef]

- Toney, N.J.; Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Tschernia, N.P.; Strauss, J.; Gulley, J.L.; Schlom, J.; Donahue, R.N. Immune correlates with response in patients with metastatic solid tumors treated with a tumor targeting immunocytokine NHS-IL12. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023 Mar;116:109736. [CrossRef]

- Fallon, J.; Tighe, R.; Kradjian, G.; Guzman, W.; Bernhardt, A.; Neuteboom, B.; Lan, Y.; Sabzevari, H.; Schlom, J.; Greiner, J.W. The immunocytokine NHS-IL12 as a potential cancer therapeutic. Oncotarget. 2014 Apr 15;5(7):1869-84. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, K.; Yue, L.; Zuo, D.; Sheng, J.; Lan, S.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, S.; Hu, S.; Chen, X.; Feng, M. Mesothelin CAR-T cells expressing tumor-targeted immunocytokine IL-12 yield durable efficacy and fewer side effects. Pharmacol Res. 2024 May;203:107186. [CrossRef]

- Corbellari, R.; Nadal, L.; Villa, A.; Neri, D.; De Luca, R. The immunocytokine L19-TNF eradicates sarcomas in combination with chemotherapy agents or with immune check-point inhibitors. Anticancer Drugs. 2020 Sep;31(8):799-805. [CrossRef]

- Corbellari, R.; Stringhini, M.; Mock, J.; Ongaro, T.; Villa, A.; Neri, D.; De Luca, R. A Novel Antibody-IL15 Fusion Protein Selectively Localizes to Tumors, Synergizes with TNF-based Immunocytokine, and Inhibits Metastasis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021 May;20(5):859-871. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Tsuji, Y.; Kashiwada, A.; Yokoyama, A.; Iwata, A.; Abe, Y.; Kamada, H.; Tsunoda, S.I. An immunocytokine consisting of a TNFR2 agonist and TNFR2 scFv enhances the expansion of regulatory T cells through TNFR2 clustering. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024 Feb 19;697:149498. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wu, Y. ; Bi J, Huang Y.; Cheng Y.; Li Y.; Wu Y.; Cao G.; Tian Z. The use of supercytokines, immunocytokines, engager cytokines, and other synthetic cytokines in immunotherapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022 Feb;19(2):192-209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raeber, M.E.; Sahin, D.; Karakus, U.; Boyman, O. A systematic review of interleukin-2-based immunotherapies in clinical trials for cancer and autoimmune diseases. EBioMedicine. 2023 Apr;90:104539.

- Lutz, E.A.; Jailkhani, N.; Momin, N.; Huang, Y.; Sheen, A.; Kang, B.H. , Wittrup K.D.; Hynes R.O. Intratumoral nanobody-IL-2 fusions that bind the tumor extracellular matrix suppress solid tumor growth in mice. PNAS Nexus. 2022 Nov 3;1(5):pgac244. [CrossRef]

- Gébleux, R.; Stringhini, M.; Casanova, R.; Soltermann, A.; Neri, D. Non-internalizing antibody-drug conjugates display potent anti-cancer activity upon proteolytic release of monomethyl auristatin E in the subendothelial extracellular matrix. Int J Cancer. 2017 Apr 1;140(7):1670-1679. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, R.; Lazear, E.; Wang, X.; Arefanian, S.; Zheleznyak, A.; Carreno, B.M.; Higashikubo, R.; Gelman, A.E.; Kreisel, D.; Fremont, D.H.; Krupnick, A.S. Selective targeting of IL-2 to NKG2D bearing cells for improved immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2016 Sep 21;7:12878. [CrossRef]

- Cazzamalli, S.; Ziffels, B.; Widmayer, F.; Murer, P.; Pellegrini, G.; Pretto, F.; Wulhfard, S.; Neri, D. Enhanced therapeutic activity of non-internalizing small molecule drug conjugates targeting carbonic Anhydrase IX in combination with targeted interleukin-2. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Aug 1;24(15):3656-3667. [CrossRef]

- Weide, B.; Neri, D.; Elia, G. Intralesional treatment of metastatic melanoma: a review of therapeutic options. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2017) 66:647–56. [CrossRef]

- Orecchia, P.; Conte, R.; Balza, E.; Petretto, A.; Mauri, P.; Mingari, M.C.; Carnemolla, B. A novel human anti-syndecan-1 antibody inhibits vascular maturation and tumour growth in melanoma. Eur J Cancer (2013) 49:2022–33. [CrossRef]

- Orecchia, P.; Balza, E.; Pietra, G.; Conte, R.; Bizzarri, N.; Ferrero, S.; Mingari, M.C.; Carnemolla, B. L19-IL2 Immunocytokine in Combination with the Anti-Syndecan-1 46F2SIP Antibody Format: A New Targeted Treatment Approach in an Ovarian Carcinoma Model. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Aug 23;11(9):1232.

- Levin AM, L Bates D.L.; Ring A.M.; Krieg C.; Lin J.T.; Su L.; Moraga I.; Raeber M.E., Bowman G.R., Novick P.; Pande V.S.; Fathman C.G.; Boyman O.; K Garcia K.C. Exploiting a natural conformational switch to engineer an interleukin-2 ‘superkine’. Nature. 2012;484(7395):529–533. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ren, Z.; Yang, K.; Liu, Z.; Cao, S.; Deng, S.; Xu, L.; Liang, Y.; Guo, J.; Bian, Y.; Xu, H.; Shi, J.; Wang, F.; Fu, Y.-. X-; Peng H. A next-generation tumor-targeting IL-2 preferentially promotes tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) T-cell response and effective tumor control. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3874.

- Charych, D.H.; Hoch, H.; Langowski, J.L.; Lee, S.R.; Addepalli, M.K.; Kirk, P.B. , Sheng D.; Liu X.; Sims P.W.; VanderVeen L.A.; Ali C.F.; Chang T.K.; Konakova M.; Pena R.L.; Kanhere R.S.; Kirksey Y.M.; Ji C.; Wang Y.; Huang J.; Sweeney T.D.; Kantak S.S. Doberstein S.K. NKTR-214, an Engineered Cytokine with Biased IL2 Receptor Binding, Increased Tumor Exposure, and Marked Efficacy in Mouse Tumor Models. Clin Cancer Res. 2016 Feb 1;22(3):680-90. [CrossRef]

- Waldhauer, I.; Gonzalez-Nicolini, V.; Freimoser-Grundschober, A.; Nayak, T.K.; Fahrni, L.; Hosse, R.J.; Gerrits, D.; Geven, E.J.W.; Sam, J.; Lang, S.; Bommer, E.; Steinhart, V.; Husar, E.; Colombetti, S.; Van Puijenbroek, E.; Neubauer, M.; Cline, J.M.; Garg, P.K.; Dugan, G.; Cavallo, F.; Acuna, G.; Charo, J.; Teichgräber, V.; Evers, S.; Boerman, O.C.; Bacac, M.; Moessner, E.; Umaña, P.; Klein, C. Simlukafusp alfa (FAP-IL2v) immunocytokine is a versatile combination partner for cancer immunotherapy. MAbs. 2021 Jan-Dec;13(1):1913791. [CrossRef]

- Ziogas DC, Theocharopoulos C, Lialios PP, Foteinou D, Koumprentziotis IA, Xynos G, Gogas H. Beyond CTLA-4 and PD-1 Inhibition: Novel Immune Checkpoint Molecules for Melanoma Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2023 ;15(10):2718. 11 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cillo AR, Cardello C, Shan F, Karapetyan L, Kunning S, Sander C, Rush E, Karunamurthy A, Massa RC, Rohatgi A, Workman CJ, Kirkwood JM, Bruno TC, Vignali DAA. Blockade of LAG-3 and PD-1 leads to co-expression of cytotoxic and exhaustion gene modules in CD8+ T cells to promote antitumor immunity. Cell. 2024 Aug 8;187(16):4373-4388.e15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu C, Tan Y. Promising immunotherapy targets: TIM3, LAG3, and TIGIT joined the party. Mol Ther Oncol. 2024 Feb 12;32(1):200773. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggi A, Zocchi MR. Natural killer cells and immune-checkpoint inhibitor therapy: Current knowledge and new challenges. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2021 Nov 29;24:26-42. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tichet, M.; Wullschleger, S.; Chryplewicz, A.; Fournier, N.; Marcone, R.; Kauzlaric, A.; Homicsko, K.; Deak, L.C.; Umaña, P.; Klein, C.; Hanahan, D. Bispecific PD1-IL2v and anti-PD-L1 break tumor immunity resistance by enhancing stem-like tumor reactive CD8+ T cells and reprogramming macrophages. Immunity. 2023 Jan 10;56(1):162-179.e6. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Liu CH, Roberts AI, Das J, Xu G, Ren G, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Yuan ZR, Tan HS, Das G, Devadas S. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and T-cell responses: what we do and don't know. Cell Res. 2006 Feb;16(2):126-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codarri Deak L, Nicolini V, Hashimoto M, Karagianni M, Schwalie PC, Lauener L, Varypataki EM, Richard M, Bommer E, Sam J, Joller S, Perro M, Cremasco F, Kunz L, Yanguez E, Hüsser T, Schlenker R, Mariani M, Tosevski V, Herter S, Bacac M, Waldhauer I, Colombetti S, Gueripel X, Wullschleger S, Tichet M, Hanahan D, Kissick HT, Leclair S, Freimoser-Grundschober A, Seeber S, Teichgräber V, Ahmed R, Klein C, Umaña P. PD-1-cis IL-2R agonism yields better effectors from stem-like CD8+ T cells. Nature. 2022 Oct;610(7930):161-172. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodig, N.; Ryan, T.; Allen, J.A.; Pang, H.; Grabie, N.; Chernova, T.; Greenfield, E.A.; Liang, S.C.; Sharpe, A.H.; Lichtman, A.H.; Freeman, G.J. Endothelial expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 down-regulates CD8+ T cell activation and cytolysis. Eur J Immunol. 2003 Nov;33(11):3117-26. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Onoe, T.; Yoshida, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohdan, H. Tumor endothelial cell–mediated antigen-specific T-cell suppression via the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2020 Sep;18(9):1427-1440. [CrossRef]

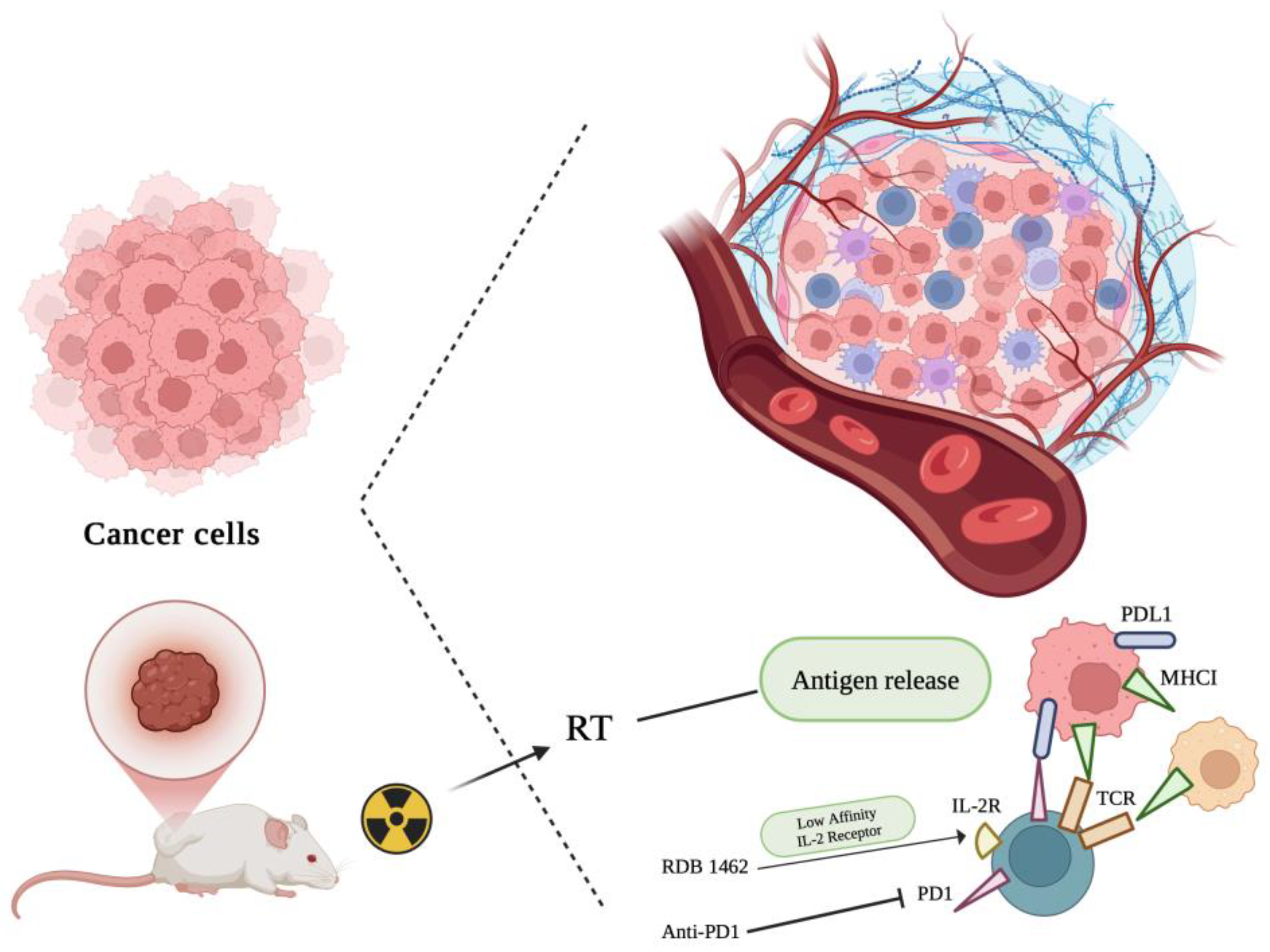

- Weichselbaum, R.R.; Liang, H.; Deng, L.; Fu, Y.X. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: a beneficial liaison? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017 Jun 17;14(6):365–79.

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wu, Y.; Yu, H. Global research landscape and trends of cancer radiotherapy plus immunotherapy: A bibliometric analysis. Heliyon. 2024 Mar;10(5):e27103.

- Wang, J.-S.; Hai-Juan Wang, H.-J.; Qian, H.-L. Biological effects of radiation on cancer cells. Mil Med Res. 2018 Jun 30;5(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Monjazeb, A.M.; Schalper, K.A.; Villarroel-Espindola, F.; Nguyen, A.; Shiao, S.L.; Young, K. Effects of Radiation on the Tumor Microenvironment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr;30(2):145–57.

- Herrera, F.G.; Bourhis, J.; Coukos, G. Radiotherapy combination opportunities leveraging immunity for the next oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 Jan 29;67(1):65–85.

- Charpentier, M.; Spada, S.; Van Nest, J.V.; Demaria, S. Radiation therapy-induced remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Seminars in Cancer Biology 86 (2022) 737–747.

- Marincola, F.M.; Jaffee, E.M.; Hicklin, D.J.; Ferrone, S. Escape of Human Solid Tumors from T–Cell Recognition: Molecular Mechanisms and Functional Significance. Adv Immunol. 2000:74:181-273. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; See, A.P.; Phallen, J.; Jackson, C.M.; Belcaid, Z.; Ruzevick, J. ; DurhamN.; Meyer C.; Harris T.J.; Albesiano E.; Pradilla G.; Ford E.; Wong J.; Hammers H.-J.; Mathios D.; Tyler B.; Brem H.; Tran P.T.; Pardoll D.; Drake C.G.; Lim M. Anti-PD-1 Blockade and Stereotactic Radiation Produce Long-Term Survival in Mice With Intracranial Gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013 Jun 1;86(2):343-9. [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S.; Coleman, C.N.; Formenti, S.C. Radiotherapy: Changing the Game in Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 2016 Jun;2(6):286-294. [CrossRef]

- Zegers, C.M.; Rekers, N.H.; Quaden, D.H.; Lieuwes, N.G.; Yaromina, A.; Germeraad, W.T.V; Wieten, L.; Biessen, E.A.L.; Boon, L.; Neri, D.; Troost, E.G.C.; Dubois, L.J.; Philippe Lambin, P. Radiotherapy combined with the immunocytokine L19-IL2 provides long-lasting antitumor effects. Clin Cancer Res. (2015) 21:1151–60. [CrossRef]

- Rekers, N.H.; Zegers, C.M.; Germeraad, W.T.; Dubois, L.; Lambin, P. Long lasting antitumor effects provided by radiotherapy combined with the immunocytokine L19-IL2. Oncoimmunology. 2015 Apr 2;4(8):e1021541. [CrossRef]

- Rekers, N.H.; Zegers, C.M.; Yaromina, A.; Lieuwes, N.G.; Biemans, R.; Senden-Gijsbers, B.L.; Losen, M.; Van Limbergen, E.J.; Germeraad, W.T.V.; Neri, D.; Dubois, L.; Lambin, P. Combination of radiotherapy with the immunocytokine L19-IL2: Additive effect in a NK cell dependent tumour model. Radiother Oncol. 2015 Sep;116(3):438-42. [CrossRef]

- Rekers, N.H.; Olivo Pimentel, V.; Yaromina, A.; Lieuwes, N.G.; Biemans, R.; Zegers, C.M.L.; Germeraad, W.T.V.; Van Limbergen, E.J.; Neri, D.; Dubois, L.J.; Lambin, P. The immunocytokine L19-IL2: An interplay between radiotherapy and long-lasting systemic anti-tumour immune responses. Oncoimmunology. 2018 Jan 16;7(4):e1414119. [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Verma, R.; Sznol, M.; Boddupalli, C.S.; Gettinger, S.N.; Kluger, H.; Callahan, M.; Wolchok, J.D.; Halaban, R.; Dhodapkar, M.V.; Dhodapkar, K.M. Combination Therapy with Anti–CTLA-4 and Anti–PD-1 Leads to Distinct Immunologic Changes In Vivo. The Journal of Immunology. 2015 Feb 1;194(3):950–9.

- Ng, J.; Dai, T. Radiation therapy and the abscopal effect: a concept comes of age. Ann Transl Med. 2016 Mar;4(6):118–118.

- Zhao, X.; Shao, C. Radiotherapy-Mediated Immunomodulation and Anti-Tumor Abscopal Effect Combining Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancers (Basel). 2020 Sep 25;12(10):2762.

- Chen, D.; Song, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, Z.; Meng, W.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y.; Youda Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Yu, J.; Yue, J. Previous Radiotherapy Increases the Efficacy of IL-2 in Malignant Pleural Effusion: Potential Evidence of a Radio-Memory Effect? Front Immunol. 2018 Dec 11:9:2916. [CrossRef]

- Gadwa, J. ; Maria Amann, Thomas E Bickett, Michael W Knitz, Laurel B Darragh, Miles Piper, Benjamin Van Court, Sanjana Bukkapatnam, Tiffany T Pham, Xiao-Jing Wang, Anthony J Saviola, Laura Codarri Deak, Pablo Umaña, Christian Klein, Angelo D'Alessandro, Sana D Karam. Selective targeting of IL2Rβγ combined with radiotherapy triggers CD8- and NK-mediated immunity, abrogating metastasis in HNSCC. Cell Rep Med. 2023 Aug 15;4(8):101150. [CrossRef]

- He, K. ; Nahum Puebla-Osorio, Hampartsoum B Barsoumian, Duygu Sezen, Zahid Rafiq, Thomas S Riad, Yun Hu, Ailing Huang, Tiffany A Voss, Claudia S Kettlun Leyton, Lily Jae Schuda, Ethan Hsu, Joshua Heiber, Maria-Angelica Cortez, James W Welsh. Novel engineered IL-2 Nemvaleukin alfa combined with PD1 checkpoint blockade enhances the systemic anti-tumor responses of radiation therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024 Sep 2;43(1):251. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).