Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

A Schiff base ligand is synthesized from the condensation of dapsone and 4-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde using cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) anacardic acid as a green and natural effective catalyst via solvent-free simple physical grinding technique. Furthermore, metal(II) complexes Co(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) coordinated by a new Schiff base ligand (L) were prepared. The composition of Schiff base ligand and its metal(II) complexes were analyzed by various analytical techniques. The Schiff base ligand and its complexes have been tested in vitro to evaluate their antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans using well-diffusion method. It has been found that the Schiff base ligand and its complexes show significant antimicrobial activity against all tested bacterial species. Molecular docking study of Cu(II) complex with target protein HER2 has revealed good binding energy.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials Details

Extraction of CNLS and Its Catalytic Activity

Experimental Procedure

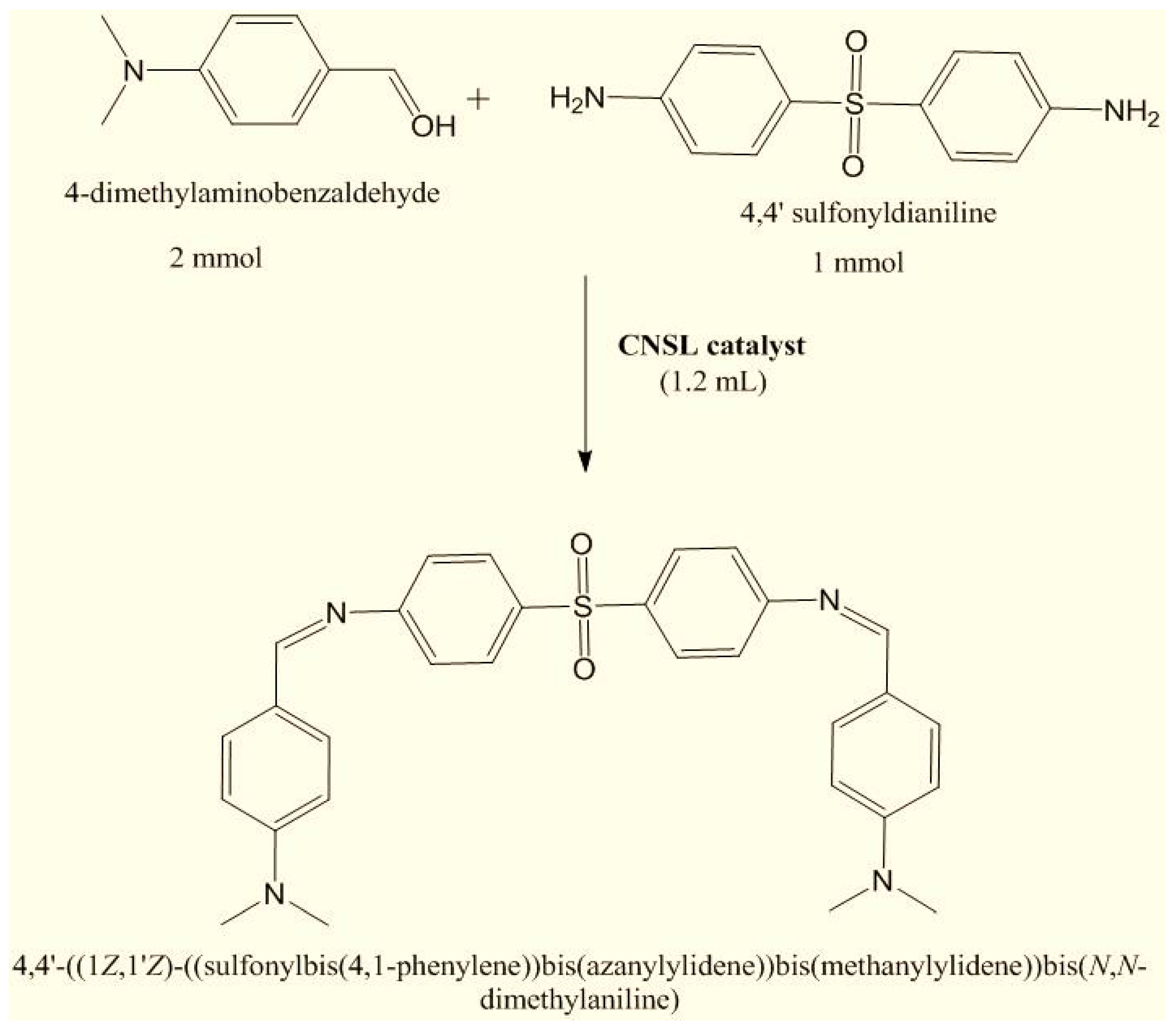

Synthesis of Schiff Base Ligand Derived from 4, 4’ sulfonyldianiline

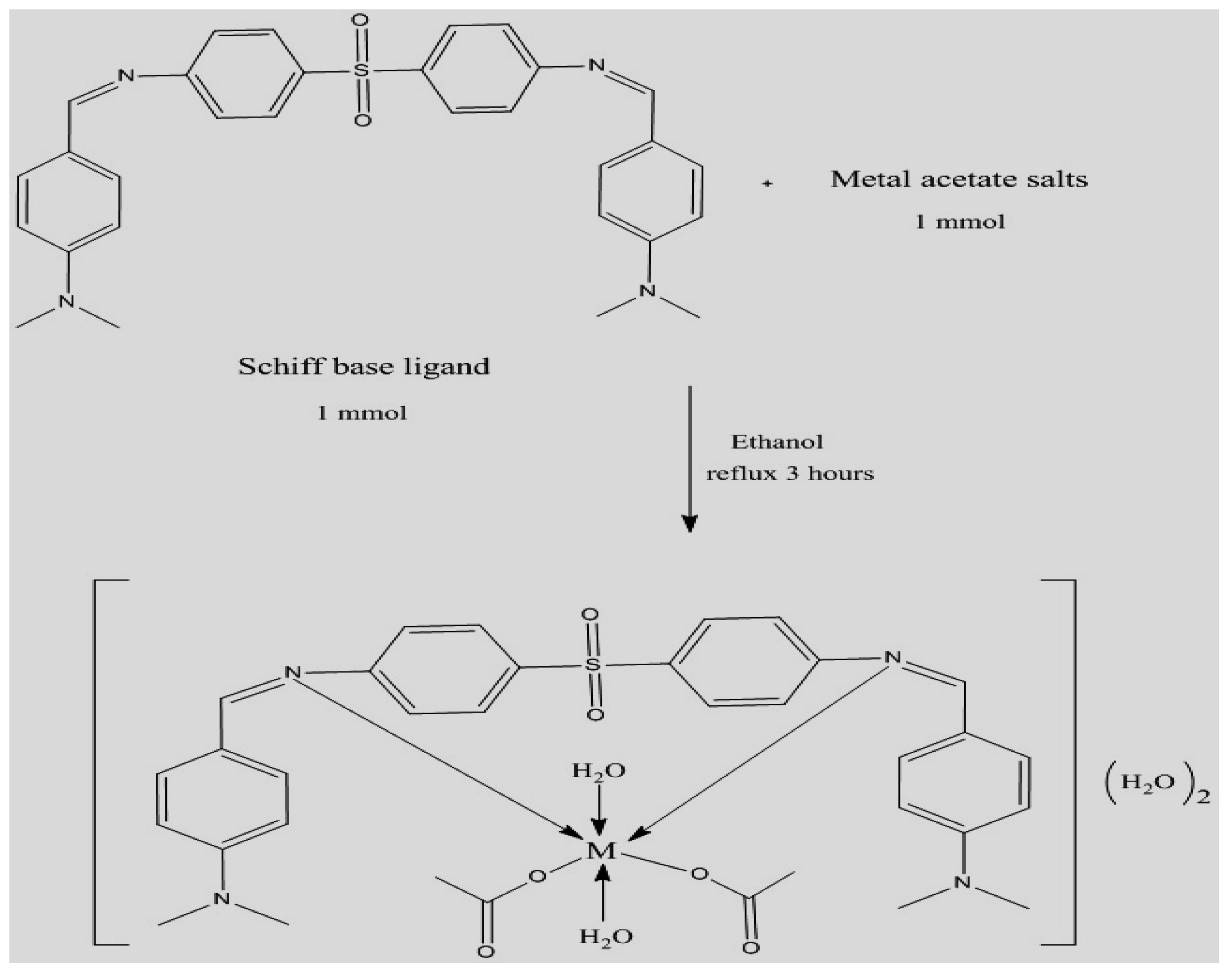

Synthesis of Schiff Base Metal(II) Complexes

M= Co(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II)

[Cu(L1) (OAc)(H2O)] (OAc) Preparation and Molecular Docking:

Results and Discussion

Elemental Analyses and Molar Conductivity Measurements

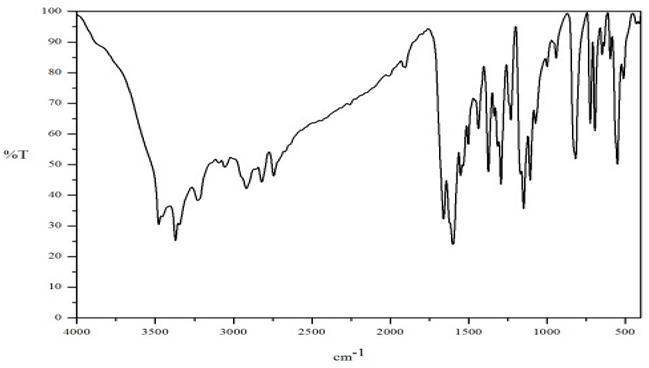

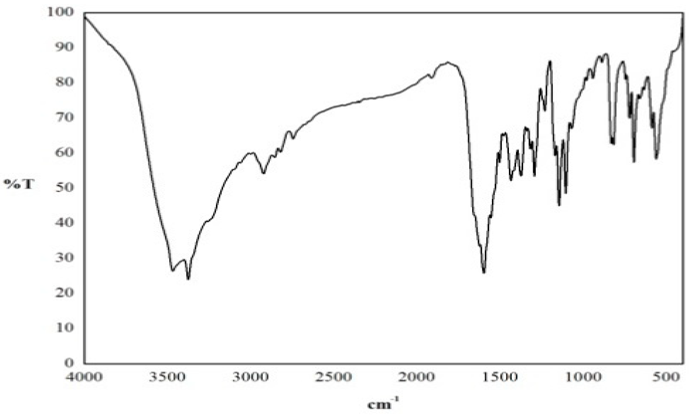

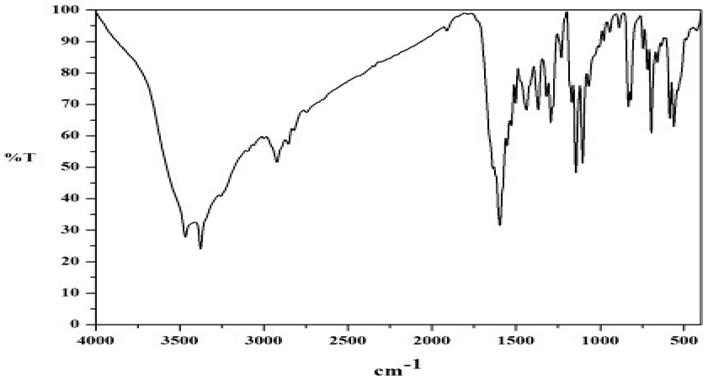

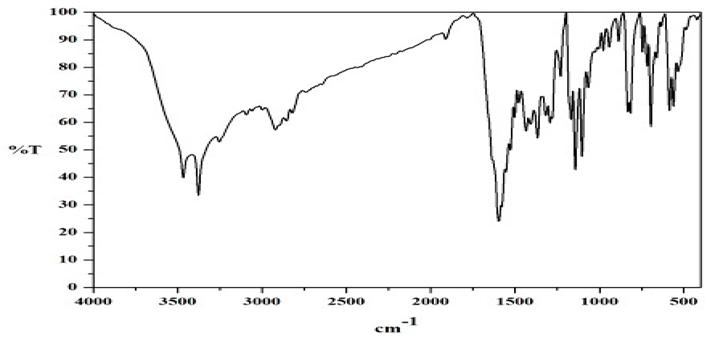

FT-IR Spectral Studies

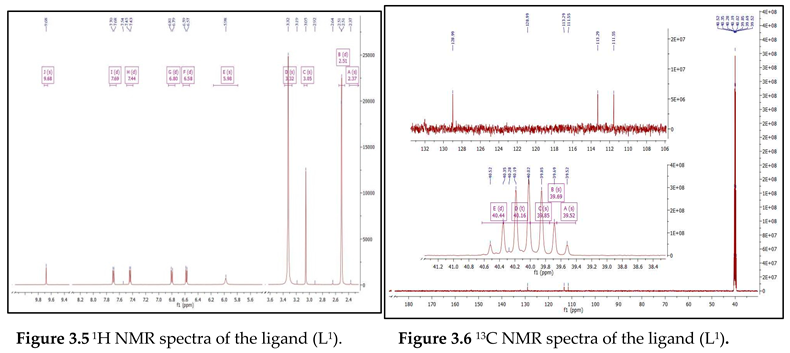

NMR Spectral Studies

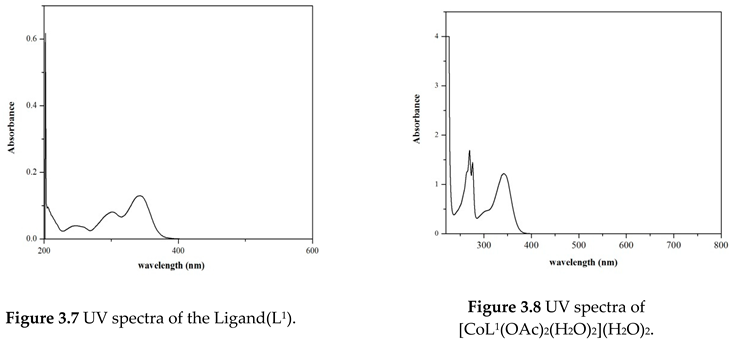

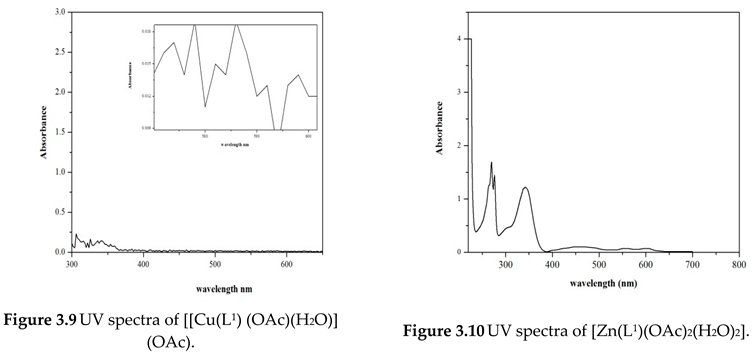

Electronic Spectral and Magnetic Moment Studies

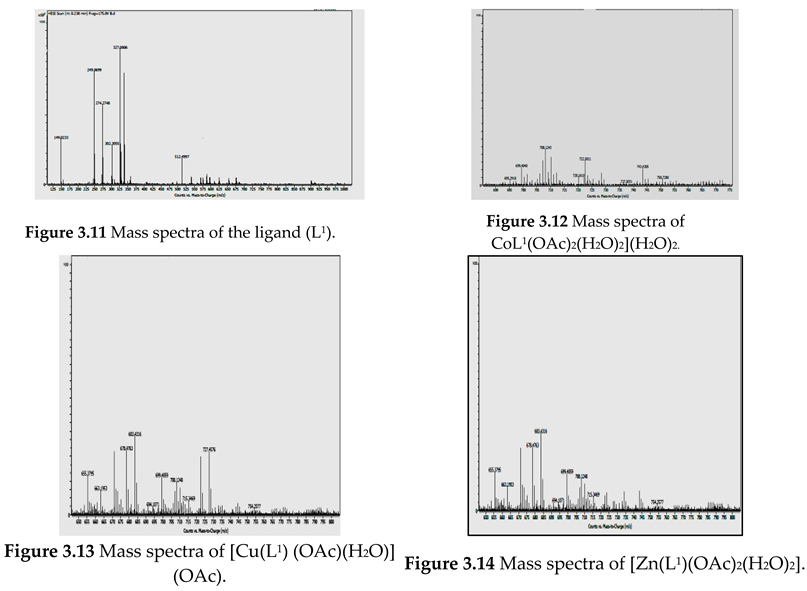

Mass Spectral Studies

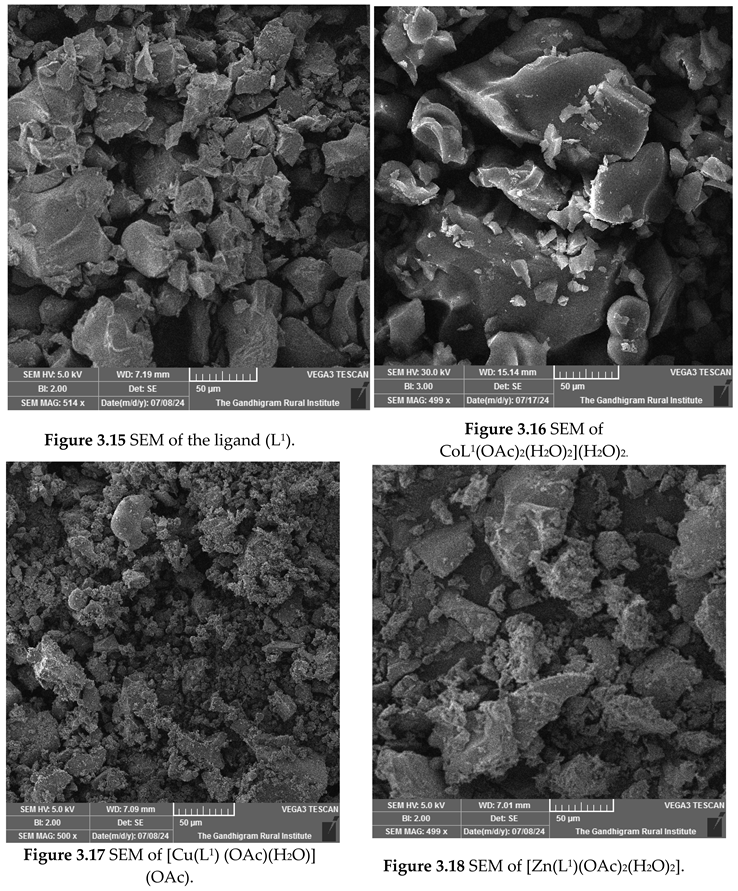

SEM Analysis

Biological Studies

Antimicrobial Activity

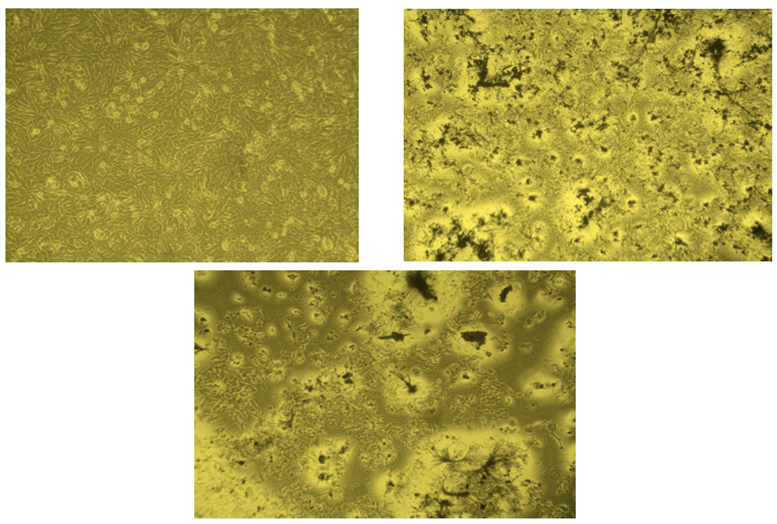

In Vitro Anticancer Activity

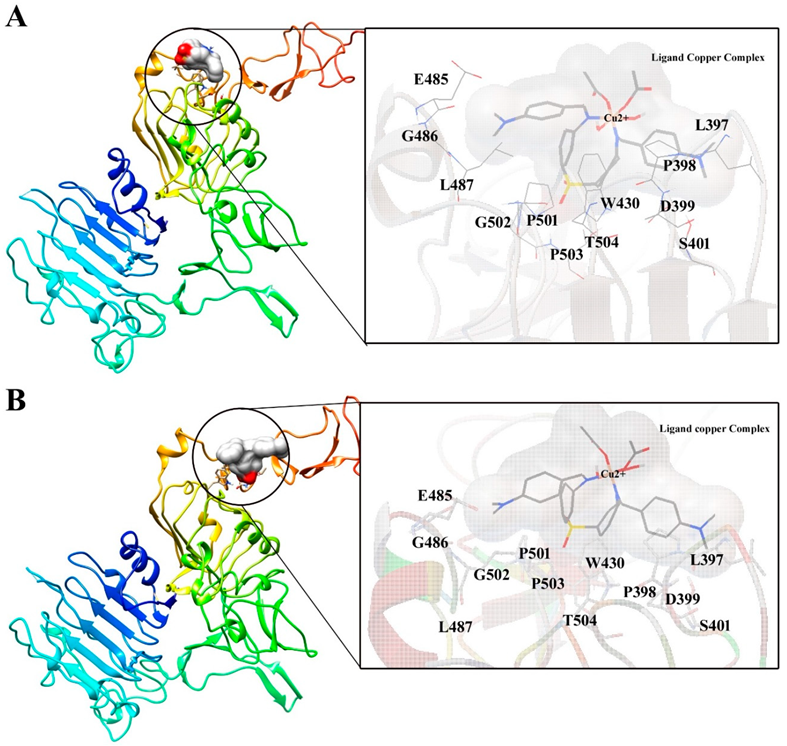

Molecular Docking and Interaction Analysis

Conclusion

References

- Nagar, S.; Raizada, S.; Tripathee, N. A review on various green methods for synthesis of Schiff base ligands and their metal complexes. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msigala, S.C.; JEG Mdoe. Synthesis of organoamine-silica hybrids using cashew nut shell liquid components as templates for the catalysis of a model henry reaction. Tanz. J. Sci. 2012, 38, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Turki, A.A.; Hanoosh, W.S. Synthesis, characterization of new di Schiff base derivatives from dapsone, their polymerization and thermal study. Bas. J. Sci. 2021, 39, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyavathi, G.T.; Kumar, B.V.; Aravinda, T.; Hani, U. Cashew nutshell liquid catalyzed green chemistry approach for synthesis of a Schiff base and its divalent metal complexes: molecular docking and dna reactivity. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids. 2021, 40, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenbrot, C.; Ultsch, M.; Dubnovitsky, A.; Abrahmsén, L.; Härd, T. Structural basis for high-affinity HER2 receptor, binding by an engineered protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 15039–15044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodsell, D.S.; Morris, G.M.; Olson, A.J. Automated Docking of Flexible Ligands: Applications of AutoDock. J. Mol. Recognit. 1996, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular Docking: A Powerful Approach for Structure-Based Drug Discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided-Drug Des. 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, A.; Anandhavelu, S.; Easwaramoorthy, D.; Karuppasamy, K.; Kim, H.-S.; Dhanasekaran, V. In vitro cytotoxicity activity of novel Schiff base ligand–lanthanide complexes. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A.T.; Al-Abdaly, B.I.; Jassim, I.K. Synthesis and Characterization new metal complexes of heterocyclic units and study antibacterial and antifungal. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 2062–2073. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, M.S.; Arish, D.; Joseyphus, R.S. Synthesis, characterization, antifungal, antibacterial and DNA cleavage studies of some heterocyclic Schiff base metal complexes. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2012, 16, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadafalea, V.A.; Thakareb, A.P.; Mandlik, P.R. Synthesis, spectral characterization and biological activity of Schiff base metal complexes derived from dapsone and salicylaldehyde. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Sci. Res. 2019, 6, 2394–0697. [Google Scholar]

- Al Zoubi, W.; Al-Hamdani, A.A.; Ahmed, S.D.; Ko, Y.G. Synthesis, characterization, and biological activity of Schiff bases metal complexes. J Phys Org Chem. 2017, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Iqbal, J.; Imran, M. Synthesis, characterization and anti-bacterial studies of some metal complexes of a Schiff base derived from benzaldehyde and sulphonamide. J. Sci. Res. 2009, XXXIX, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoopathy, P.; Jayalakshmi, R.; Rajavel, R. An Insight into Antibacterial and Anticancer Activity of Homo and Hetero Binuclear Schiff Base Complexes. Orient. J. Chem. 2017, 33, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokan, R.; Sathishkumar, S.; Akila, E.; Rajavel, R. Synthesis, characterization and biological activity of Schiff base metal complexes derived from 2, 4 dihydroxyactophenone. Chem Sci Trans. 2017, 6, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sura, H. Kathim. Synthesis and Characterization of the Inhibitory Activity of 4- (Dimethyl amino) benzaldehyde Schiff Bases. Wasit Journal for Pure Science 2023, 4, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burak, O.; Erdal, C. ; Hakan,Ş.; Mehmet, K. The synthesis, characterization of a novel Schiff base ligand and investigation of its transition metal complexes. Adıyaman university journal of science 2017, 7, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.N.; Gaur, P.R.; Jhariya, S.A.; Chaurasia, B.H.; Vaidya, P.R.; Dehariya, D.I.; Azam, M. Synthesis, Characterization, In Vitro Anti-diabetic, Antibacterial and Anticorrosive Activity of Some Cr(III) Complexes of Schiff Bases Derived from Isoniazid. Chem Sci Trans. 2018, 7, 424–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, S.A.; Ali, M.M.; El-rashedy, A.A. Synthesis, anticancer activity and molecular docking study of Schiff base complexes containing thiazole moiety. Beni - Suef university journal of basic and applied sciences. 2016, 5, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deswal, Y.; Asija, S.; Kumar, D.; Jindal, D.K.; Chandan, G.; Panwar, V.; Saroya, S.; Kumar, N. Transition metal complexes of triazole-based bioactive ligands: synthesis, spectral characterization, antimicrobial, anticancer and molecular docking studies. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2022, 48, 703–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, M.A.; Saranyaparvathi, S.; Raksha, C.; Vrinda, B. Transition Metal Complexes of 4-Aminoantipyrine Derivatives and Their Antimicrobial Applications. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2022, 48, 696–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juyal, V.K.; Thakuri, S.C.V.K.; Panwar, M. Manganese (II) and Zinc(II) metal complexes of novel bidentate formamide-based Schiff base ligand: synthesis, structural characterization, antioxidant, antibacterial, and in-silico molecular docking study. Front. Chem. 2024, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, M.; Naik, V.H.; Kulkarni, A.D. DNA cleavage, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory anthelmintic activities, and spectroscopic studies of Co(II), Ni(II), and Cu(II) complexes of biologically potential coumarin Schiff bases. J. Coord. Chem. 2011, 24, 4264–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelavathy, C.; Antony, A. Structural elucidation and thermal studies of some novel mixed ligand Schiff base metal (II) complexes. Int. J. Basic Appl. Chem. Sci. 2013, 3, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Vamsikrishna, N.; Kumar, M.P.; Ramesh, G.; Ganji, N.; Daravath, S. DNA interactions and biocidal activity of metal complexes of benzothiazole Schiff bases: synthesis, characterization and validation. J. Chem. Sci. 2017, 129, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.K.; Panda, N.; Behera, N.K. Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activities of Schiff Base Complexes Derived from Isoniazid and Diacetylmonoxime. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 3, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, B.B.; Mishra, R.R.; Sarangi, A.K. Synthesis, characterisation, XRD, molecular modelling and potential antibacterial studies of Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), Zn(II), Cd(II) and Hg(II) complexes with bidentate azodye ligand. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomathi, T.; Vedanayaki, S. Synthesis, Spectral, Electrochemical and Biological Studies on Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) Complexes Derived from 4-(2-Aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol and Terephthalaldehyde. Asian J. Chem. 2022, 6, 1373–138234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagavalli, A.; Jayachitra, R.; Thilagavathi, G.; Padmavathy, M.; Elangovan, N.; Sowrirajan, S.; Thomas, R. Synthesis, structural, spectral, computational, docking and biological activities of Schiff base (E)-4-bromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene) amino)-N-(pyrimidin-2-yl) benzenesulfonamide from 5-bromosalicylaldehyde and sulfadiazine. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2023, 100, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfandi, R.; Raya, I. Potential anticancer activity of Mn (II) complexes containing arginine dithiocarbamate ligand on MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. Ann. med. surg. 2020, 60, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, R.V.; Sankudevan, P.; Vennila, P.; Venkatesh, G.; Kaya, S. Experimental and theoretical analysis of molecular structure, vibrational spectra and biological properties of the new Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) Schiff base metal complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1233, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, U.; Webb, B.M.; Barkan, D.T.; Schneidman-Duhovny, D. ModBase, a database of annotated comparative protein structure models, and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.NO | Amount of catalyst (ml) | Time (minutes) | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2 | 30 | nil |

| 2 | 0.4 | 25 | 30 |

| 3 | 0.6 | 15 | 55 |

| 4 | 0.8 | 5 | 85 |

| 5 | 1.0 | 5 | 85 |

| Compound | M.Wt. | Color | M.Pt. °C |

Molar conductance Ω- 1 cm2 mol-1 | Elemental analysis Calculated (Found) % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | M | ||||||

| Ligand(L1) C30H30N4O2S |

510.21 | Brown | 120 | -- | 70.16 (70.56) |

5.96 (5.92) |

10.13 (10.97) |

----- | |

| [Co(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] (H2O)2 C34H42N4O9S Co |

741.20 | Reddish brown | 220 | 18.16 | 55.12 (55.06) |

5.45 (5.71) |

7.23 (7.55) |

7.81 (7.95) |

|

| [Cu(L1) (OAc) (H2O)] (OAc) C34H38N4O7SCu |

709 | brown | 245 | 20.21 | 57.42 (57.49) |

5.24 (5.39) |

7.96 (7.89) |

8.90 (8.95) |

|

| [Zn(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] C34H40N4O8SZn |

728 | brown | 232 | 32.65 | 55.48 (55.93) |

5.42 (5.52) |

7.76 (7.67) |

8.87 (8.95) |

|

| Compound | ʋ(H2O) cm-1 | υ(C=N) cm-1 | ʋ(SO2) cm-1 |

ʋ(M-N) cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand (L1) | ------ | 1659 | 1314 | --- |

| [Co(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] (H2O)2 | 3450 | 1637 | 1319 | 561 |

|

[Cu(L1) (OAc) (H2O)] (OAc) |

3467 | 1622 | 1317 | 560 |

|

[Zn(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] |

3378 | 1596 | 1317 | 534 |

| Compound | Absorption (nm) | Band assignment | Geometry | Magnetic moment (BM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand (L1) | 270 341 |

INCT INCT |

------- | ------ |

| [Co(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] (H2O)2 | 275 348 429 534 |

INCT INCT 4 T1g (F)—4 T1g (P) 4 T1g (F)—4 A2g (F) |

Octahedral | 4.12 |

|

[Cu(L1) (OAc) (H2O)] (OAc) |

272 355 512 |

INCT INCT 2B1g—2A1g |

Square- planar | 1.80 |

|

[Zn(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] |

275 345 495 |

INCT INCT LMCT |

Octahedral | Diamagnetic |

| Sample | Zone of inhibition (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram positive | Gram negative | Fungi | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Escherichia coli | Candida albicans | |

| Ligand (L1) | 31 | 9 | 13 |

| [Co(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] (H2O)2 | 35 | 10 | 21 |

|

[Cu(L1) (OAc) (H2O)] (OAc) |

36 | 11 | 18 |

|

[Zn(L1) (OAc)2 (H2O)2] |

33 | 9 | 12 |

| Standard | 30 | 20 | 17 |

| Ligand (L1) Concentration (μg/ml) |

Cell Viability % | IC50 (μM) |

[Cu(L1) (OAc)(H2O)] (OAc) Concentration (μg/ml) | Cell Viability % | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.125 | 96.79 | 35.78 | 3.125 | 94.16 | 24.62 |

| 6.25 | 91.42 | 6.25 | 90.67 | ||

| 12.5 | 83.66 | 12.5 | 72.78 | ||

| 25 | 67.78 | 25 | 55.81 | ||

| 50 | 35.54 | 50 | 30.16 |

| S. No | Ligand copper complex | Binding energy (Kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant Ki (mM) | Intermolecular Energy (Kcal/mol) | Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Top 1 pose | -2.42 | 16.77 | -5.70 | L397, P398, D399, S401, W430, E485, G486, L487, P501, G502, P503, T504, |

| 2. | Top 2 pose | -2.21 | 24.14 | -5.49 | L397, P398, D399, S401, W430, E485, G486, L487, P501, G502, P503, T504, |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).